Abstract

How hematopoietic stem cells coordinate the regulation of opposing cellular mechanisms like self-renewal and differentiation commitment remains unclear. Here, we identified the transcription factor and chromatin remodeler Satb1 as a critical regulator of the hematopoietic stem cell (HSC) fate. HSCs lacking Satb1 displayed defective self-renewal, less quiescence and accelerated lineage commitment, resulting in progressive depletion of functional HSCs. Increased commitment was caused by reduced symmetric self-renewal and increased symmetric differentiation divisions of Satb1-deficient HSCs. Satb1 simultaneously repressed gene sets involved in HSC activation and cellular polarity, including Numb and Myc, two key factors for stem cell fate specification. Thus, Satb1 is a regulator that promotes HSC quiescence and represses lineage commitment.

In metazoans, adult tissue-specific stem cells (SCs) constitute a rare population of long-lived cells possessing the ability to give rise to multiple differentiated cell types. Hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) ensure the life-long generation of all cells of the innate and adaptive immune system, as well as red blood cells and platelets1. Like many other tissue-specific SCs in multicellular organisms, HSCs exhibit key features separating them functionally from differentiated cell types: relative cellular quiescence, self-maintenance and multilineage differentiation capacity2, 3. Balancing HSC self-renewal and differentiation is crucial for the long-term maintenance of the pool of functional HSCs and thus for their ability to sustain blood cell production and regeneration4. Alterations in the balance between quiescence and activation, self-renewal and differentiation are known to exhaust HSCs5 or lead to their malignant transformation6.

Transcriptional regulation by specific factors is critical to ensure the appropriate function of both embryonic and adult tissue-specific stem cells, in part by governing their ability to self-renew and differentiate7. The interplay of transcriptional programs, rather than individual transcription factors, determines the entire set of SC functions including fate decisions8, 9. However, how individual functions such as SC quiescence, division, and lineage commitment are coordinately regulated only begins to be understood. Global epigenetic regulation was shown to have an important role in the function and lineage differentiation of SCs including HSCs8, 10, 11. However, it is still largely unknown how specific epigenetic factors impact and integrate gene activation and repression of multiple transcriptional programs in SCs.

Satb1 (special AT-rich sequence-binding protein 1) was identified as a chromatin organizer that forms “cage-like” chromatin networks in the nucleus of T cell precursors, tethering together specific DNA sequences and regulating the expression of several genes relevant for T cell maturation12-14. Satb1 is also involved in the differentiation of other hematopoietic lineages15 and embryonic stem cells by controlling expression of transcriptional master regulators, such as Sfpi115 or Nanog16. Several studies have also linked Satb1 with cancer. Enhanced activity of this epigenetic factor is capable of reprogramming transcriptional networks and promoting aberrant growth and metastasis in different types of epithelial tumors17-19. Additionally, impairment of Satb1 is associated with a subtype of acute myelogenous leukemia15. The role of Satb1 in tissue-specific SCs including HSCs has not been examined thus far.

Here, we investigated the role of Satb1 in HSCs and found that Satb1 critically mediates multiple, functionally linked HSC properties. Satb1 is crucial for the maintenance of HSC self-renewal and exerts its function through simultaneously regulating transcriptional programs associated with the cell polarity factor Numb, Myc and several cell cycle regulators, thereby promoting quiescence and repressing lineage commitment in HSCs.

Results

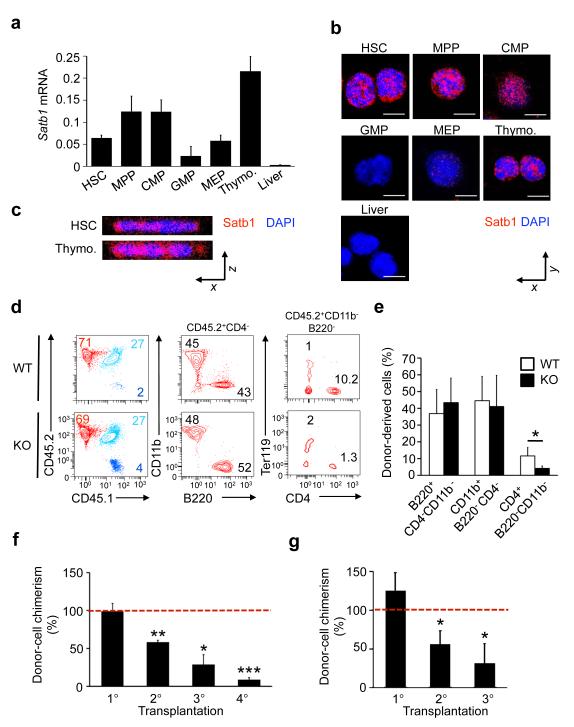

Satb1 deficiency impairs long-term repopulation capacity of HSCs

To characterize Satb1 mRNA and protein expression in immature hematopoietic cells we performed qRT-PCR and immunohistochemistry on purified murine HSCs (CD150+ Lin− cKit+ Sca-1+ (LSK)), multipotent progenitor cells (MPPs; CD150− LSK), common myeloid progenitor cells (CMPs; CD34+ FcγRII/III− cKit+ Sca-1− Lin−), granulocytic-monocytic progenitor cells (GMPs; CD34+ FcγRII/III+ cKit+ Sca-1− Lin−), and megakaryocytic-erythroid progenitor cells (MEPs; CD34− FcγRII/III− cKit+ Sca-1− Lin−) (for sorting strategy see Supplementary Fig. 1a). We found Satb1 mRNA and protein to be highly expressed in thymocytes and well detectable in all bone marrow-derived stem and progenitor cells (Fig. 1a,b). Among the immature hematopoietic cell populations, Satb1 expression was highest in the HSC, MPP and CMP compartments, and decreased in lineage-restricted GMPs and MEPs. Satb1 was localized in the nucleus in HSCs as assessed by confocal microscopy (Fig. 1c). In thymocytes, Satb1 was reported in the nucleus and shown to act as a transcriptional regulator20, 21.

Figure 1. Satb1 is expressed in HSCs and is critical for HSC long-term repopulation capacity.

(a) Quantitative RT-PCR analysis of Satb1 mRNA in sorted HSCs, MPPs, CMPs, GMPs, MEPs and thymocytes (Thymo.). Liver cells were used as negative control. Shown are averages and standard deviations of Gapdh-normalized expression levels (n=3/population). (b) Detection of Satb1 protein by immunohistochemistry and confocal microscopy in HSCs, MPPs, CMPs, GMPs, and MEPs from 6-8 week old Bl6/C57 mice. The nucleus was counterstained with DAPI. Scale bars indicate 5μm. (c) Z-stacks of representative images showing nuclear localization of Satb1 in HSCs and thymocytes. (d) FACS analysis of multilineage engraftment 16-20 weeks after transplantation of wild-type and Satb1−/− HSCs (CD45.2) into recipient mice (CD45.1). Total nucleated cells, donor-derived myeloid cells (CD11b+ CD4− B220−), B cells (B220+ CD4− CD11b−) and T cells (CD4+ B220− CD11b−) are shown. (e) Quantification of multilineage engraftment of wild-type and Satb1−/− myeloid and lymphoid lineages transferred and analyzed as in d (two independent experiments, n=10/genotype, *p<0.05). (f) Engraftment of Satb1−/− total fetal liver cells in the peripheral blood of serial competitive transplantation recipients (1°, 2°, 3°, 4°) 16-20 weeks after transplantation and expressed as % of the wild-type donor cell engraftment (dashed line) (*p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.005). (g) Engraftment of sorted Satb1−/− CD150+ CD11b+ Sca-1+ Lin− fetal liver cells in lethally irradiated primary recipients (1°), and of sorted CD150+ LSK HSC in secondary (2°) and tertiary (3°) recipients 20 weeks after transplantation expressed as % of the wild-type donor HSC engraftment (dashed line) (n=12/genotype, *p<0.01).

To assess the role of Satb1 in HSC function, we examined multilineage reconstitution and long-term self-maintenance capacities of HSCs utilizing a Satb1−/− mouse model in which the first five of eleven exons, encoding 213 amino acids including the translation start codon, were eliminated and result in a complete lack of Satb1 protein12. We first characterized fetal hematopoiesis, as homozygous Satb1−/− animals die around the time of birth. Flow cytometry analysis showed normal frequencies of HSCs, MPPs, CMPs, GMPs, and MEPs in the fetal liver at E17-18.5 days (Supplementary Fig. 1b). Colony assays revealed that compared to wild-type cells, Satb1−/− fetal livers contain a significantly increased number of functional colony-initiating progenitors of the granulocytic-monocytic (2.2 ± 0.6-fold), erythroid (4.3 ± 1.9-fold) and monocytic lineages (15.5 ± 7.1-fold) (Supplementary Fig. 1c). Non-competitive transplantation of Satb1−/− and wild-type fetal liver cells resulted in comparable hematopoietic reconstitution 24 weeks after transplantation (Supplementary Fig. 1d) with no significant effect on the reconstitution of mature myeloid, erythroid, or B cells (Fig. 1d,e); only the CD4+ T cells were moderately reduced which is consistent with previous observations12. The frequency of functional HSCs in E17-18.5 fetal livers was also not found significantly changed by the absence of Satb1, as determined by competitive limiting dilution transplantation assays (Supplementary Fig. 1e). These findings show that during embryogenesis, Satb1 is neither essential for the generation of HSCs, nor for their short-term multi-lineage repopulation capacity.

In order to evaluate the long-term self-renewal ability of HSCs in the absence of Satb1, we conducted competitive serial transplantation experiments22. Unfractionated Satb1−/− cells from the fetal liver showed a progressive repopulation defect in serial competitive transplantations, with a 42 ± 2.4% reduction in the second reconstitution, 71.3 ± 12.9% reduction in third, and 91.3 ± 2.7% reduction in the fourth serial transfer in comparison to wild-type cells (Fig. 1f and Supplementary Fig. 2a). Serial transplantation of purified Satb1−/− HSCs also showed a progressive loss of repopulation capacity compared to wild-type HSCs, with a 44 ± 15% reduction in second and 69 ± 25% reduction in third serial transfer (Fig. 1g and Supplementary Fig. 2b). Characterization of the repopulation of different cell lineages showed a reconstitution impairment in all compartments (Supplementary Fig. 2c), indicative of a defect at the stem cell level. Taken together, these data show that Satb1 is indispensable for long-term self-renewal of HSCs, and that the absence of Satb1 leads to a progressive decrease of functional HSCs.

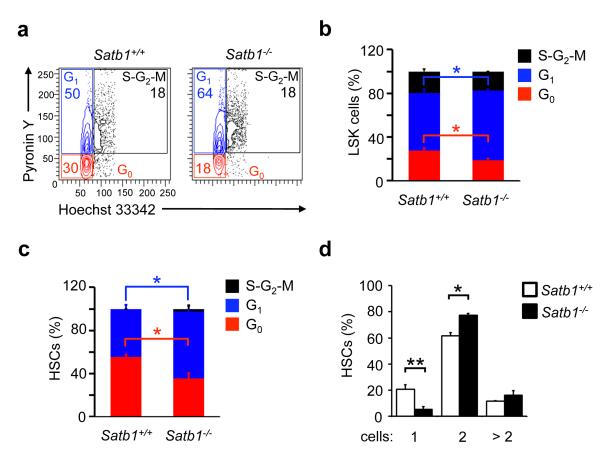

Satb1-deficient hematopoietic stem cells are less quiescent

The maintenance of a quiescent state is an important feature of HSCs and loss of quiescence has been shown to lead to the loss of functional HSCs23. To determine whether Satb1 regulates HSC quiescence we compared the number of quiescent and actively cycling HSCs in wild-type or Satb1−/− mice in vivo using Pyronin Y and Hoechst 33343 intercalation assays24 on immature LSK (Lin− Sca-1+ cKit+) cells (Fig. 2a,b) as well as on purified HSCs (Fig. 2c). In both stem cell-containing populations the number of quiescent cells in the G0 phase of the cell cycle was significantly reduced in the absence of Satb1 (Fig. 2b,c). However, most apparent differences in the cell cycle distribution were observed within the purified HSC population, in which 36 ± 4.5% of Satb1−/− cells compared to 53.5 ± 2.1% wild-type HSC were found in G0 , while the number of Satb1−/− HSC in G1 (63 ± 5.7%) was significantly increased compared to wild-type (42.5 ± 3.5%; Fig. 2c). Consistently, the alteration in cell cycle activity was accompanied by a change in cell division kinetics. When using individually sorted, highly enriched HSCs (CD150+ CD48− LSK), significantly less Satb1−/− HSCs (5 ± 2.4%) remained in an undivided state compared to wild-type HSCs (20.7 ± 3.4%), while significantly more Satb1−/− HSCs divided once compared to wild-type (77.5 ± 1.2% versus 61.5 ± 1.2%) after 48hrs in an ex vivo culture assay (Fig. 2d). Consistently, we found that Satb1 expression in wild-type HSCs is cell cycle phase-dependent, with highest Satb1 expression in G0 (Supplementary Fig. 2d). Satb1 expression in HSCs decreased significantly upon HSC activation under stress conditions in vivo (5-fluorouracil treatment) (Supplementary Figure 2e). Together, these results indicate that Satb1 promotes quiescence of HSCs under steady state as well as stress conditions.

Figure 2. Satb1 deficiency leads to reduced HSC quiescence.

(a) Flow cytometric analysis of cell cycle distribution of wild-type and Satb1−/− HSCs 20-24 weeks after transplantation using Pyronin Y and Hoechst 33342 intercalation. Representative FACS plots and gating strategy are shown for LSK cells. (b) Quantification of LSK cells in G0, G1 and S-G2-M phases (n=2/genotype, two independent experiments, * p<0.05). (c) Quantification of CD150+ LSK HSC in G0, G1 and S-G2-M phases (n=2/genotype, two independent experiments, * p<0.05). (d) Division assay of sorted, and individually deposited CD150+ CD48− LSK HSCs. Shown are averages and standard deviations of the relative number (%) of wells containing the indicated number of cells after culture of single HSCs (two independent experiments, nTotal=120 cells/genotype; * p<0.05, ** p<0.01).

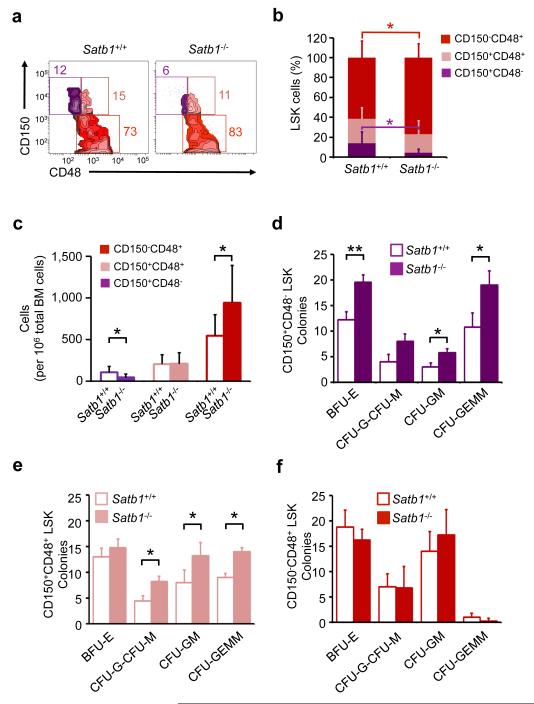

Satb1-deficient HSC show increased differentiation commitment

To further elucidate functional alterations of adult Satb1−/− HSCs we characterized the composition of hematopoietic stem and multipotent progenitor cell compartments following competitive congenic transplantation of wild-type and Satb1−/− cells. Recipients of unfractionated Satb1−/− fetal liver cells showed a significant reduction of HSCs (CD150+ CD48− LSK) (4.2 ± 3.6%) compared to recipients of wild-type cells (13.9 ± 11.6%), and an increase of CD150− CD48+ LSK multipotent progenitor cells (77.5 ± 12.9% compared to 61.4 ± 16.9% in recipients of wild-type cells; Fig. 3a,b). Quantification of the number of HSCs (CD150+ CD48− LSK) and MPPs (CD150− CD48+ LSK) also showed a significant decrease of HSCs (46 ± 40 cells/106 compared to 107 ± 71 cells/106 total nucleated bone marrow cells) and a significant increase of MPPs (944 ± 446 cells/106 compared to 549 ± 254 cells/106 total nucleated bone marrow cells) in recipients of Satb1−/− compared to recipients of wild-type cells (Fig. 3c).

Figure 3. Satb1 deficiency increases the number of multipotent progenitors and colony-initiating cells originating from the HSC compartment.

(a) Analysis of phenotypic HSCs and MPPs 20 weeks after transplantation of wild-type or Satb1−/− fetal liver cells by FACS. Representative FACS plots analyzing CD45.2+ LSK cells gated on CD150+ CD48− LSK, CD150+ CD48+ LSK, and CD150− CD48+ LSK cells. (b) Quantification of the relative distribution and (c) absolute numbers of CD150+ CD48− LSK, CD150+ CD48+ LSK, and CD150− CD48+ LSK cells. Shown are averages and standard deviations (n=8/genotype, two independent experiments, * p<0.05). (d) Colony formation assay of wild-type (open bars) and Satb1−/− (solid bars) CD150+CD48− LSK cells. Shown are averages and standard deviations of colony-forming units of the erythroid (BFU-E), granulocytic or monocytic (CFU-G/M), granulocytic-monocytic (CFU-GM), and granulocytic-erythroid-monocytic-megakaryocytic (CFU-GEMM) lineages. (e) Colony formation assay of wild-type (open bars) and Satb1−/− (solid bars) CD150+ CD48+ LSK cells. (f) Colony formation assay of wild-type (open bars) and Satb1−/− (solid bars) CD150− CD48+ LSK cells. All assays were plated in M3434 GF+ semisolid medium (n=2/genotype; * p<0.05, ** p<0.01).

To test if Satb1−/− HSCs are more prone to commit to differentiation, we evaluated colony-formation capacities of fractionated CD150+ CD48− LSK and CD150+ CD48+ LSK cells, and MPPs (CD150−CD48+ LSK ; Fig. 3d-f). Satb1−/− CD150+ CD48− LSK cells formed 1.6-fold more erythroid burst colony forming units (BFU-E), 1.9-fold more granulocyte-monocyte colony forming units (CFU-GM), and 1.8-fold more granulocyte-erythrocyte-monocyte-megakaryocyte colony forming units (CFU-GEMM) compared to wild-type (Fig. 3d). Similarly, CD150+ CD48+ LSK cells also showed a 1.7-fold increase in the generation of CFU-GM, 1.8-fold increase in CFU-G or M, and a 1.6-fold increase in CFU-GEMM (Fig. 3e). This increased myeloid colony formation in Satb1−/− cells was restricted to the HSC compartments, as we did not observe a significant change in the colony formation of MPPs (Fig. 3f). These findings suggest that Satb1 suppresses differentiation commitment specifically in HSCs.

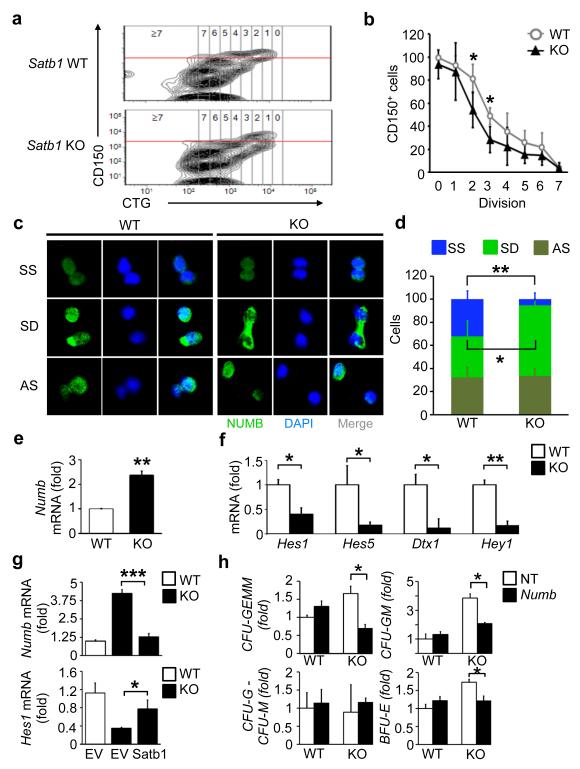

To further assess the role of Satb1 in HSC commitment, we modified a recently described method for tracing cell divisions in stem and progenitor cells in vivo25. Here, we purified donor-derived CD150+ LSK cells from long-term reconstituted recipients and labeled them with 5-chloromethylfluorescein diacetate, a cell division tracer. These cells were then transplanted into a second cohort of sublethally irradiated recipients and assessed by monitoring cell division and CD150 expression of the individual donor-derived HSCs (Fig. 4a). We used CD150 as a marker as it has been demonstrated that HSCs downregulate CD150 upon commitment to differentiation26, 27. Applying this novel strategy we found that Satb1-deficient CD150+ LSK HSCs downregulate CD150 after fewer cell divisions post transplantation in comparison to wild-type HSCs (Fig. 4a,b). After two divisions, 54.3 ± 15.5% of Satb1−/− HSCs versus 81.2 ± 12.5% of wild-type HSCs still expressed CD150. After three divisions, 28.6 ± 11.4% of the Satb1−/− HSCs vs. 48.8 ± 7.4% of the wild-type HSCs expressed CD150 (Fig. 4b). These observations indicate that HSC commitment is quantitatively increased in the absence of Satb1.

Figure 4. Satb1−/− HSCs show increased differentiation commitment, a loss of symmetric self-renewal and an increase in symmetric differentiation divisions.

(a) In vivo commitment tracing of CD150+ LSK HSCs using CellTracker Green (CTG). Representative FACS plots showing CTG content and CD150 expression of viable wild-type (WT) and Satb1−/− (KO) CD45.2+ LSK cells. Horizontal red line indicates analysis cut-off for CD150 expression. Vertical lines separate cells according to their division number. (b) Averages and standard deviations of the relative number of CD150+ wild-type or Satb1−/− CD45.2+ LSK cells, expressed as percent of total CD45.2+ LSK cells, after 0-7 divisions (n=4/genotype in two independent experiments; * p<0.05). (c) Numb staining in individually sorted wild-type and Satb1−/− CD150+ LSK cells after one division. DNA was counterstained with DAPI. Shown are representative images of symmetric self-renewal (SS), symmetric differentiation (SD), and asymmetric (AS) division. (d) Averages and standard deviations of symmetric and asymmetric divisions in wild-type and Satb1−/− CD45.2+ CD150+ LSK cells 24 weeks after transplantation (three independent experiments; wild-type: n=75 cell doublets, Satb1−/−: n=85 cell doublets, * p<0.05). (e) Quantification of Numb mRNA expression in wild-type and Satb1−/− CD150+ CD48− LSK cells by qRT-PCR. Shown are expression averages and standard deviations normalized to Gapdh compared to wild-type HSCs (n=2/genotype, ** p<0.01). (f) Quantification of mRNA expression of Notch target genes Hes1, Hes5, Dtx1, and Hey1 in wild-type (open bars) and Satb1−/− (solid bars) CD150+ LSK cells by qRT-PCR. Shown are averages and standard deviations of the fold change of mRNA expression normalized to Gapdh compared to wild-type cells (n=3/genotype, * p<0.05, ** p<0.01). (g) Quantification of Numb and Hes1 mRNA expression by qRT-PCR after lentiviral transduction of wild-type and Satb1−/− CD150+ CD48− LSK cells with either empty vector (EV) or a Satb1-expressing vector (Satb1). Shown are averages and standard deviations normalized to Gapdh (* p<0.05, *** p<0.005). (h) Colony assay of wild-type and Satb1−/− CD150+ CD48− LSK cells transduced with lentiviral constructs expressing shRNA against Numb (Numb) or non-targeting shRNA (NT). Shown are averages and standard deviations of the fold change in the number of colony-forming units of the erythroid (BFU-E), granulocytic or monocytic (CFU-G/M), granulocytic-monocytic (CFU-GM), and granulocytic-erythroid-monocytic-megakaryocytic (CFU-GEMM) lineages normalized to the number of lineage-specific colonies generated by NT-treated wild-type HSCs in two independent experiments (n=2/genotype, * p<0.05).

Satb1 regulates the fate of HSC by modulating the division mode

The impairment of long-term repopulation capacity and the increased commitment of Satb1−/− HSCs, led us to hypothesize that Satb1 regulates the division mode of HSCs by promoting symmetric self-renewal divisions and repressing differentiation divisions. To test this, we quantified symmetric and asymmetric divisions in individual Satb1−/− and wild-type HSCs, utilizing staining for the cell fate determinant and polarity factor Numb as previously described28, 29. Increased Numb protein expression in one of two daughter cells indicates an asymmetric division, detection of high Numb expression in both daughter cells shows symmetric differentiation divisions, while sustained low levels of Numb in both daughter cells marks symmetric self-renewal divisions (Fig. 4c). We quantified division types of individual HSCs and found a significant, 6.2-fold decrease of symmetric self-renewal divisions in Satb1−/− HSCs in comparison to wild-type HSCs (5.2 ± 5.4% versus 32.4 ± 7.2%), while symmetric differentiation divisions were significantly increased in Satb1−/− HSCs compared to wild-type HSCs (61.4 ± 5.5% vs. 35.2 ± 13.5%; Fig. 4d). These observations show that Satb1 promotes self-renewal and suppresses differentiation commitment of HSCs by regulating the type of stem cell division.

Satb1 regulates Notch targets through repression of Numb in HSCs

Regulation of Numb has mainly been reported at the protein level30, 31, and Numb was recently also found to be transcriptionally regulated in Drosophila sensory bristle cells32. Transcriptional or epigenetic regulation of Numb in mammalian stem cells is unknown. We quantified Numb mRNA expression in Satb1−/− and wild-type CD150+ CD48− LSK HSCs and found a two-fold increase of Numb mRNA expression in Satb1−/− HSCs compared to wild-type HSCs (Fig. 4e). Numb is a negative regulator of Notch signaling, which has been reported to modulate cell-fate decisions of HSC30, 31. We therefore assessed whether elevated Numb expression in the absence of Satb1 has an effect on the transcription of Notch target genes. We found that Satb1−/− CD150+ LSK HSCs, as well as highly purified CD150+ CD48− LSK HSCs, showed significantly reduced levels of Notch targets, including Hes1 (by 60 ± 13%), Hes5 (by 82.5 ± 6.6%), Dtx1 (by 88.5 ± 19.4%) and Hey1 (by 83.4 ± 9.2%) in comparison to wild-type HSCs (Fig. 4f, Supplementary Fig. 3a,b). To further test whether Numb is downstream of Satb1 and whether elevated Numb expression was functionally critical for the altered cell fate of Satb1−/− HSCs we carried out rescue experiments (Fig. 4g,h). Ectopic re-expression of Satb1 in Satb1-deficient HSCs to a level similar to wild-type HSCs led to restoration of Numb expression, as well as Hes1 expression (Fig. 4g, Supplementary Fig. 3c). Moreover, shRNA-mediated knock down of elevated Numb in Satb1−/− CD150+ CD48− LSK HSCs by 60 ± 3.1% lead to a significant reduction of the increased number of colony-initiating cells by reducing CFU-GEMMs (reduced by 58.2 ± 6.7%), CFU-GMs (reduced by 45.8 ± 2%) and BFU-Es (reduced by 30 ± 8%) compared to non-targeting control-transduced cells (Fig. 4h, Supplementary Fig. 3d). Consistent with this observation, the expression of Hes1, Hes5 and Dtx1 was de-repressed in comparison to non-targeting control-transduced Satb1−/− CD150+ CD48− LSKs (by 2.9 ± 0.2-fold, 2.8 ± 0.4-fold, and 4.3 ± 0.8-fold respectively; Supplementary Fig. 3e). Interestingly, shRNA-mediated knock-down of Numb in wild-type HSCs did not cause a significant change in the number of colony-initiating cells (Fig. 4h). These results demonstrate that Satb1 modulates cell fate determination of HSCs, at least in part, through regulation of Numb expression and Notch signaling. The fact that downregulation of Numb was sufficient to rescue the increased differentiation commitment of Sabt1−/− HSCs but did not have an effect in wild-type HSCs, suggested that additional mechanisms contribute to the changes in cell fate in Satb1-deficient HSCs.

Satb1 deficiency alters transcriptional networks in HSCs

To obtain insight into potential cooperating factors contributing to the increase of differentiation commitment in Satb1-deficient HSCs, we measured gene expression changes in Satb1−/− HSCs. Microarray analysis of adult wild-type and Satb1−/− HSCs identified 631 differentially expressed genes (Supplementary Table 1) of which 73.3% showed increased and 26.3% showed decreased expression, supporting a role of Satb1 as an overall transcriptional repressor in HSCs. Ingenuity Pathway Analysis (IPA) revealed that Satb1-dependent genes in HSCs were highly enriched for gene networks regulating cellular assembly and organization, and cell cycle (Supplementary Fig. 4a). We validated the altered expression of a subset of genes from both categories by real time PCR in an independent set of samples. We confirmed that genes involved in cell cycle activation (Rbbp9: 3.5 ± 1-fold, Kdm3a: 2.2 ± 0.3-fold, Chaf1a: 4.2 ± 1.9-fold and Bgn: 36 ± 21.3-fold) and genes regulating cellular organization and contributing to cellular polarity (Iptr1: 2.1 ± 0.46-fold, Tnik: 2.3 ± 1.7-fold) were significantly overexpressed in Satb1−/− HSCs (Supplementary Fig. 4b). These data show that Satb1 regulates different functional gene networks in HSCs, which are supportive of the observed phenotype of enhanced cell cycle activity and differentiation commitment of Satb1−/− HSCs.

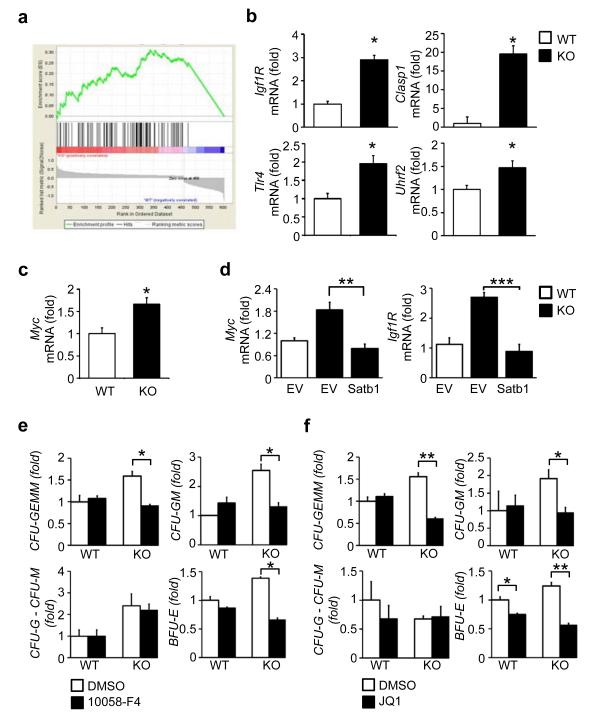

Gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA)33 of differentially expressed genes in absence of Satb1 identified a core set of direct Myc target genes34 positively enriched in the Satb1−/− HSCs (normalized enrichment score: 1.90, nominal p-value < 0.001) (Fig. 5a, Supplementary Fig. 4c). Validation by quantitative real-time PCR demonstrated that several Myc targets including Igf1R (2.9 ± 0.2-fold), Clasp1 (19.6 ± 13.3-fold), Tlr4 (1.9 ± 0.2-fold), and Uhrf2 (1.47 ± 0.2-fold) (Fig. 5b), as well as Myc itself (1.66 ± 0.2-fold) were overexpressed in Satb1−/− CD150+ CD48− LSK HSCs compared to wild-type HSCs (Fig. 5c). To assess whether Myc is downstream of Satb1, as it was previously shown in T cells21, we measured Myc expression in Satb1−/− HSCs upon lentiviral re-expression of Satb1. Restoration of Satb1 expression in Satb1-deficient CD150+ CD48− LSK HSCs led to a normalization of expression of Myc, and its target Igfr1 (Fig. 5d). These data show that Satb1 regulates transcriptional networks involved in cell cycle regulation and cellular organization in HSCs.

Figure 5. Inhibition of enhanced Myc activity restores the increased differentiation commitment of Satb1−/− HSCs to wild-type levels.

(a) Gene set enrichment analysis of the differentially expressed genes in Satb1−/− compared to wild-type HSCs showing an enrichment of Myc target genes (normalized enrichment score = −1.93, nominal p-value < 0.001). (b) Quantification of mRNA expression of Myc targets Igf1R, Clasp1, Uhrf2 and Tlr4 in wild-type and Satb1−/− CD150+ CD48− LSK cells by qRT-PCR. Shown are expression averages and standard deviations normalized to Gapdh compared to wild-type cells (n=3/genotype, * p<0.05). (c) Quantification of Myc mRNA expression in wild-type and Satb1−/− CD150+ CD48− LSK cells by qRT-PCR. Shown are expression averages and standard deviations normalized to Gapdh compared to wild-type cells (n=3-4/genotype, * p<0.05). (d) Quantification of Myc and Igf1R mRNA expression in wild-type and Satb1−/− CD150+ CD48− LSK cells after lentiviral transduction with either empty vector (EV) or a Satb1-expressing vector (Satb1) by qRT-PCR. Shown are averages and standard deviations of mRNA expression normalized to Gapdh (n=3, ** p<0.01, *** p<0.005). (e) Colony assay of wild-type and Satb1−/− CD150+ CD48− LSK HSCs after 48 hour treatment with 10058-F4, or DMSO. Shown are averages and standard deviations of the number of colony-forming units of the erythroid (BFU-E), granulocytic or monocytic (CFU-G/M), granulocytic-monocytic (CFU-GM), and granulocytic-erythroid-monocytic-megakaryocytic (CFU-GEMM) lineages normalized to the number of lineage-specific colonies generated by DMSO-treated wild-type HSCs. (f) Colony assay of wild-type and Satb1−/− CD150+ CD48− LSK HSCs after 48 hour treatment with JQ1, or DMSO. Shown are averages and standard deviations of the number of BFU-Es, CFU-G and CFU-Ms, CFU-GMs, CFU-GEMMs normalized to the number of colonies generated by DMSO-treated wild-type HSCs. Data from two independent experiments in technical duplicates are shown (n=2/genotype, * p<0.05, ** p<0.01).

Increased Myc activity is functionally relevant for enhanced differentiation commitment of Satb1-deficient HSCs

To test whether the Satb1-dependent increase of Myc activity is functionally relevant in Satb1−/− HSCs, we treated Satb1-deficient CD150+ CD48− LSK HSCs with two different small molecule Myc inhibitors (10058-F4 and JQ1) and assessed colony-initiating capacity. Both 10058-F4, which has been shown to specifically interfere with Myc transactivation35, as well as JQ1, a bromodomain/BRD4 inhibitor causing direct repression of Myc transcription36, were found to impair Myc target gene expression (Supplementary Fig. 5a,b) and colony formation of Satb1-deficient HSCs (Supplementary Fig. 5c,d) in a dose-dependent manner. We then tested a low effective inhibitor concentration (15μM of 10058-F4 and 250nM of JQ1) on both Satb1−/− and wild-type HSCs, and found a reduction of CFU-GEMMs by 39 ± 1.9%; CFU-GMs by 48.9± 8%; and BFU-Es by 45 ± 2.8% for 10058-F4 in comparison to DMSO-treated controls, and a reduction of CFU-GEMMs by 56.8± 1.9%,CFU-GMs by 51± 5.6% and BFU-Es by 47.2± 2.7% by JQ1 in Satb1-deficient HSCs, demonstrating a rescue of the increased number of colony forming units (Fig. 5e,f). We did not observe an effect of inhibitors on wild-type CD150+CD48−LSK HSCs (Fig. 5e,f). These results show that elevated Myc activity is functionally important in Satb1−/− HSCs. Of note, Numb expression was not significantly changed upon Myc inhibitor treatment of Satb1−/− HSC (Supplementary Fig. 5e).

Satb1-deficient HSCs display widespread epigenetic changes

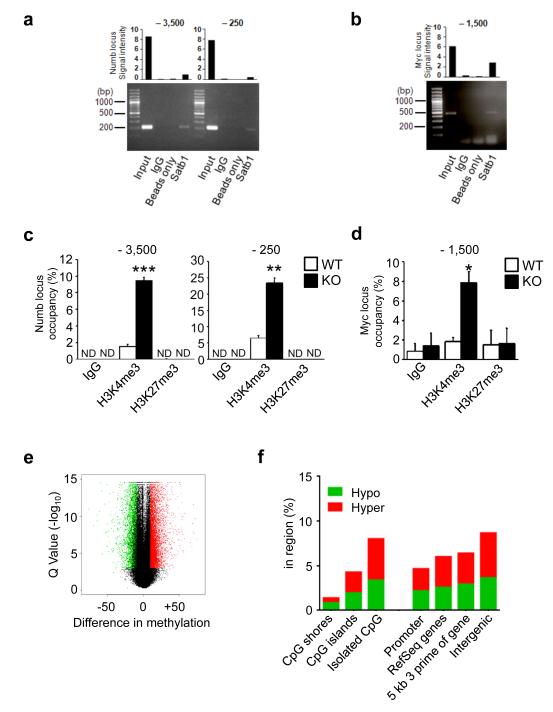

We assessed whether Satb1 binds to the Numb and Myc promoter regions in HSCs by performing chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) using a hematopoietic stem cell line (HPC7)37. We found that Satb1 binds to chromatin upstream of the transcriptional start sites of Numb and Myc (Fig. 6a,b, Supplementary Fig. 6a,b). As Satb1-dependent gene regulation has been linked with epigenetic modifications, such as histone modifications and DNA cytosine methylation16, 21, we analyzed permissive (H3K4me3) and repressive (H3K27me3) histone marks at the Numb and Myc promoters. ChIP of primary Satb1−/− and wild-type HSCs revealed that absence of Satb1 significantly increased the H3K4me3 mark at both the Numb and Myc promoter regions (Fig. 6c,d), which is in line with the elevated expression of Numb and Myc in Sabt1−/− HSCs.

Figure 6. Epigenetic alterations in Satb1−/− HSCs.

(a) Measurement of Satb1 binding to the Numb and (b) the Myc locus by chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) in HPC7 cells. Shown are PCR amplification products of sites at the indicated positions relative to the transcriptional start sites. Bar graphs show the quantification of signal intensities of the PCR products. Normal rabbit IgG antibody and uncoated beads were used as controls. (c) Analysis of H3K4me3 and H3K27me3 presence by qChIP in wild-type and Satb1−/− CD150+ LSK HSCs at the Numb locus. ND: not detectable. (d) Analysis of H3K4me3 and H3K27me3 binding by qChIP in wild-type and Satb1−/− CD150+ LSK HSCs at the Myc locus. Normal rabbit IgG antibody was used as a control. Shown are occupancies of H3K4me3 and H3K27me3 measured in triplicate (pool of n=6/genotype, * p<0.05, ** p<0.01, *** p<0.005). (e) Analysis of DNA cytosine methylation in wild-type and Satb1−/− CD150+ LSK HSCs by enhanced reduced representation bisulfite sequencing (ERRBS) of (n=2/genotype; two independent experiments). Shown is a volcano plot of a total of 11,924 differentially methylated regions (DMRs) comprising 5,089 hypomethylated and 6,835 hypermethylated DMRs in Satb1−/− HSCs compared to wild-type HSCs. (f) Relative frequency of hypomethylated (hypo) and hypermethylated (hyper) DMRs with at least 10× coverage as determined by ERRBS within CpG shores, CpG islands, or isolated CpGs, as well as within different genomic features (promoter, RefSeq gene regions, 5kb downstream of RefSeq genes, and in intergenic regions). Shown are the percentages of DMRs within each region for Satb1−/− HSCs compared to wild-type HSCs.

We further evaluated genome-wide DNA cytosine methylation by enhanced reduced representation bisulfite sequencing (ERRBS) of DNA extracted from sorted HSCs and MPPs. Comparison of Satb1−/− HSCs to wild-type HSCs revealed significant differences in DNA cytosine methylation, with a total of 11,924 differentially methylated regions (DMRs; 1kb genomic tiles, no overlap) comprising 5,089 hypomethylated and 6,835 hypermethylated DMRs (Fig. 6e, Supplementary Table 4). Satb1−/− associated DMRs were predominantly located in CpG islands and isolated CpGs, without a strong preference for location within different genomic regions, but with a slight increase in the occurrence of DMRs in intergenic regions (Fig. 6f). Next, we compared wild-type HSCs and wild-type MPPs to define methylation changes associated with normal HSC commitment. We identified a total of 14,778 HSC commitment-associated DMRs (Supplementary Fig. 6c), which were primarily located in CpG islands and isolated CpGs, and without a strong preference for inter- or intragenic regions (Supplementary Fig. 6d). When we compared these normal HSC commitment-associated DMRs with the DMRs identified in Satb1-deficient HSCs, we found a highly significant overlap (p=1.2×10−37; hypergeometrical testing), with 37% shared hypermethylated DMRs and 15% shared hypomethylated DMRs (overall 22% shared DMRs) (Supplementary Fig. 6e).

We further evaluated whether methylation changes were accompanied by gene expression changes in Satb1−/− HSCs and found a set of 67 genes showing both significant alterations in gene expression and methylation in the vicinity of the gene (Supplementary Table 5). IPA analysis revealed enrichment of several functionally relevant networks (Supplementary Fig. 6f, Supplementary Table 6). Notably, amongst those was a subset of genes whose differential expression we had previously validated by qRT-PCR (Itpr1, Tnik) in Satb1−/− HSCs, and which have known roles in cell cycle and cellular assembly and organization (Supplementary Fig. 4b)38, 39. Taken together, these data show that Satb1 acts as an epigenetic regulator in HSCs by modulating histone marks and DNA cytosine methylation, and indicate that Satb1 deficiency leads to a commitment-primed epigenetic state in HSCs.

Discussion

The interaction between transcription factor networks is a key mechanism of cell fate decisions in pluripotent hematopoietic cells, including HSCs40-42. The biological outcome of simultaneous activity of multiple transcriptional networks depends on the exact cellular and temporal context as HSCs commit and differentiate70. However, how transcriptional networks themselves are established and coordinately regulated in stem cells is still largely unknown. Our study identifies the chromatin-remodeling factor Satb1 as a regulator of transcriptional programs instructing quiescence, self-renewal and commitment in HSCs.

Quiescent HSCs exhibit superior long-term engraftment potential over HSCs in the G1/S/G2/M phase24,43. The restriction of cell cycling of HSCs prevents their premature depletion and hematopoietic failure under stress conditions44. Our study revealed that genes important for cell cycle activation including factors important in the transition from a quiescent (G0) to an active stage (G1) were derepressed in Satb1−/− HSCs. Consistent with these findings, Satb1−/− HSCs were in a more activated state with significantly less HSCs in the G0 and more in the G1 phase of the cell cycle in comparison to Satb1-expressing HSCs. In contrast to the G0 phase, G1 is the cell cycle phase in which intrinsic signals can influence cell fate. Integration and interpretation of transcriptional programs determine whether a cell enters S phase or pauses during G1, until the cell makes the decision whether to self-renew, differentiate or undergo apoptosis45. Enhanced progression of Satb1−/− HSCs into G1 may alter their proneness to cell fate specification by making them more susceptible to commitment-inducing factors. Interestingly, Satb1−/− HSCs displayed a quantitatively increased generation of committed progenitor cells, indicating that Satb1 is critical for suppressing HSC commitment and links HSC quiescence with differentiation.

Chromatin-remodeling factors have been found to regulate cell fate in embryonic stem cells39 and invertebrate stem cells46. We found that Satb1−/− HSCs undergo significantly more symmetric commitment divisions at the expense of symmetric self-renewal divisions, while the rate of asymmetric divisions remained unchanged. Two Satb1-dependent gene networks were directly involved in the regulation of cellular polarity, differentiation, and proliferation. In Satb1−/− HSCs, expression of Myc and several of its transcriptional targets, and expression of the negative Notch regulator, Numb, was increased. Enforced expression or activation of Myc can lead to an increase in differentiation at the expense of self-renewal in HSCs47. Similarly, relatively modest elevation of Numb expression can also induce differentiation of HSCs29, suggesting that Satb1 inhibits differentiation commitment, at least in part, via the repression of Myc and Numb. Indeed, independent Numb and Myc rescue experiments showed that the combination of both increased Myc and increased Numb is functionally critical for the increased commitment of Satb1−/− HSC.

Numb is a segregating cell fate determinant and tissue-specific repressor of the Notch pathway30, 31. Numb-mediated suppression of Notch in HSCs can induce differentiation29. We found that Satb1 negatively regulates Numb expression in HSCs and that Satb1 deficiency leads to Numb-mediated inhibition of Notch target gene expression. Impairment of the Notch target genes Hes1 and Hes5 in HSCs was demonstrated to cause a loss of HSC and overproduction of myeloid progenitor cells48, which is consistent with the observed phenotype and the functional rescue experiments in Satb1−/− HSCs. Restoration of Satb1 expression in Satb1−/− HSCs led to a normalization of elevated Numb levels and a significant increase of Hes1. Furthermore, restoration of Numb expression normalized Hes1, Hes5, and Dtx1 expression, and rescued the increased colony-initiating capacity of Satb1−/− HSCs. These data show that in the absence of Satb1, elevated Numb mediates the reduction of symmetrical self-renewal divisions and the concomitant increased production of multipotent progenitor cells, which ultimately depletes the pool of Satb1−/− HSCs.

In T cells, Satb1 binds the Myc promoter and instructs histone modifications21. We found that Satb1 binds both the Numb and Myc promoters in HPC7 cells, and restoration of Satb1 expression in Satb1−/− HSCs rescued elevated Numb and Myc expression. These observations, together with the finding of increased Numb and Myc expression in Satb1−/− HSCs, show that both Numb and Myc are downstream of Satb1. It is possible that this regulatory function of Satb1 is indirect and that cofactors are required.

Satb1 acts as an epigenetic regulator and chromatin organizer in T cells and erythroid cells20 and is accompanied by alterations in histone modifications16. Our data show that absence of Satb1 increases the permissive H3K4me3 mark at both the Numb and the Myc promoters in Satb1−/− HSCs. In addition, we detected significant differences in DNA cytosine methylation in Satb1−/− HSCs, which resembles wild-type MPPs and indicates a “commitment-primed” epigenetic state of Satb1−/− HSCs. These findings further support our observation of increased differentiation commitment and reduced self-renewal of Satb1−/− HSCs, and show that Satb1 acts as an epigenetic regulator in HSCs by modulating histone marks and DNA cytosine methylation.

Impairment of Satb1 activity is associated with a subset of patients with AML15. Moreover, myeloid biased hematopoiesis was recently found in murine loss-of-function models of positive Notch regulators, and loss-of-function mutations of the Notch pathway were identified in patients with chronic myelomonocytic leukemia, consistent with the possibility that myeloid differentiation commitment of HSCs is enhanced by reduced Notch activity49. This suggests a possible role of Satb1 inactivation in stem and progenitor cells in leukemia pathogenesis. As Satb1 is important for epithelial-mesenchymal transition and elevated Satb1 levels were found in epithelial tumors17, 50, it will be of interest to determine whether Satb1, similar to its function in hematopoietic stem cells, modulates cell polarity and self-renewal in tumor stem cells, and may thereby offer novel opportunities for tumor stem cell-directed therapy.

In summary, our study demonstrates that Satb1 critically modulates HSC fate decisions by acting as a regulator of multiple, functionally linked HSC properties. Our data show that Satb1 is crucial for sustained HSC self-renewal, through simultaneously governing gene networks controlling cell fate, promoting quiescence and repressing lineage commitment in HSCs.

ONLINE METHODS

Mice

Satb1−/− mice12 were kindly provided by Dr. T Kohwi-Shigematsu. C57Bl/6 SJL CD45.1+ mice were purchased from Jackson Labs (Bar Harbor, ME). All experimental procedures were approved by the Einstein Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (protocol #2011-0102).

Purification of hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells

Bone marrow cells were isolated from tibiae, femurs and pelvic bones. Fetal liver cells were isolated from E17-18.5 embryos. Red blood cell lysis was followed by negative enrichment using Dynabeads (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) with the following primary antibodies (all PE-Cy5/Tricolor): CD4, CD8a, CD19 (1:100 in PBS/FBS) (eBioscience, San Diego, CA) and B220, Gr-1 (1:50, Invitrogen). Washed, unbound cells were stained with the following antibodies (all 1:30): APC Alexa 750 CD117 (eBioscience), Pacific Blue Sca-1 (Biolegend, San Diego, CA), FITC CD34 (eBioscience), PE-Cy5 CD16/32, PE CD150 (Biolegend), APC CD48 (Biolegend). Cells were sorted using a 5-laser Aria II Special Order System flow cytometer (Becton Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, NJ). Purity of sorted HSCs and MPPs was >98% for all experiments. Analysis of FACS data was performed using BD FACSDiva (Becton Dickinson) and FlowJo (Tree Star, Ashland, OR) software.

Colony formation and serial replating assays

Fetal liver cells or donor-derived adult stem and progenitor cells were plated in MethoCult M3434 GF+ according to the manufacturer’s recommendation (Stem Cell Technologies, Vancouver, BC). Colonies were scored after 7-10 days using an AXIOVERT 200M microscope (Zeiss, Maple Grove, MN).

RNA purification, Real-time PCR, and microarray experiments

RNA was extracted using the RNeasy Micro kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA), and quantity and quality was assessed using an Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA). For real-time RT-PCR, RNA was reverse-transcribed using Superscript II reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen), and amplified using specific primers (Supplementary Table 2) and the universal PCR Power SYBR Green mix (Applied Biosystems, Carlsbad, CA) on an iQ5 real-time PCR detection system (BIO-RAD, Hercules, CA) according to the manufacturer’s recommendation. For microarray studies, RNA was amplified using the WT Ovation Pico RNA amplification system (Nugen, San Carlos, CA). After labeling with the GeneChip WT terminal labeling kit (Affymetrix, Santa Clara, CA), labeled cRNA was hybridized to Mouse Gene ST 1.0 microarrays (Affymetrix), stained, and scanned by GeneChip Scanner 3000 7G system (Affymetrix) according to standard protocols.

HSC activation using 5-fluorouracil

4-8 week old Bl/6C57 wild-type mice were injected intra peritoneal (i.p.) with 150 mg/kg 5-fluorouracil (Sigma-Aldrich). After 0-12 days, CD150+ CD48− LSK and CD150+ CD48− LSKs were isolated from the pooled bone marrow samples of three injected mice by FACS sorting.

Analysis of microarray data

Raw data was normalized by the RMA algorithm of Affymetrix Power Tools v. 1.178. Significance Analysis for Microarrays within Multiple Experiment Viewer v. 4.851, (row average imputation, s0 percentile 5%, delta 0.38742) was combined with raw selection of differentially expressed genes (median expression differences of >1.1-fold). Following removal of unannotated and sex-specific genes varying among the control samples, genes were clustered by hierarchical clustering, with optimization of sample and gene leaf order, using Euclidean distance, complete linkage clustering. Gene Set Enrichment Analysis was performed using all gene sets from mSigDB v3.0 and from the signature database of the Staudt laboratory (http://lymphochip.nih.gov/signaturedb).

Immunohistochemistry

Sorted cells were cytospun on poly-lysine-coated glass slides, dried and fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde, stained, and imaged on a Leica SP5 confocal microscope (Leica, Buffalo Groove, IL). Satb1 and Numb was detected using antibodies against Satb1 (1:250) (Epitomics, Burlingame, CA) or Numb (1:100) (Abcam, Cambridge, MA) according to the manufacturers’ recommendation.

Reconstitution experiments, and competitive serial, and limiting dilution transplantations

1×106 nucleated cells from CD45.2+ fetal livers were transplanted into lethally irradiated 6-8 week old C57Bl/6 SJL recipient animals via retro-orbital injection following total body irradiation (950 cGy) using a Shepherd 6810 137Cs irradiator.

For serial transplantation assays 5×105 nucleated CD45.2+ donor cells, 50 CD150+CD11b+Sca-1+Lin− fetal liver, or adult CD45.2+CD150+ LSK were transplanted along with 5×105 CD45.1+ or CD45.1/CD45.2+ total bone marrow competitor cells into lethally irradiated C57Bl/6 SJL mice. After 16-24 weeks, donor cell chimerism and multilineage reconstitution were determined, and CD45.2+ donor cells were isolated from the bone marrow of recipient animals by FACS. 5×105 sorted CD45.2+ donor cells were transplanted along with 5×105 fresh CD45.1+ or CD45.1/CD45.2+ total bone marrow competitor cells into the next cohort of lethally irradiated C57Bl/6 SJL mice.

Limiting dilution transplantation assays were performed as previously described.52 Reconstitution was monitored after 8-12 weeks and 16-24 weeks after transplantation. HSCs were quantified as competitive repopulating units using the L-Calc algorithm as previously described.53

Analysis of cell cycle activity in HSCs

Cell cycle activity in HSCs was measured using Hoechst 33342 and Pyronin Y incorporation as previously described.24 Division kinetics of HSCs was determined by culture of sorted, individual, donor-derived wild-type or Satb1−/− HSCs in CellGro media (CellGenix, Freiburg, Germany) with 50ng/ml mrSCF and 50ng/ml mrTPO. Deposition of individual cells in Terasaki plates was confirmed by microscopy 4hrs after the sort. 48hrs after deposition, the number of wells containing 1, 2 and >2 cells was determined using light microscopy.

HSC division mode assay

To determine symmetric/asymmetric divisions we monitored Numb distribution in HSCs undergoing division by immunohistochemistry as previously described.29

Lineage tracing using CMFDA

To monitor HSC commitment kinetics in vivo, we modified a previously described protocol for lineage tracing utilizing viability dyes.25 CD45.2+CD150+ LSK bone marrow cells from > 20 weeks transplanted CD45.1+ mice were labeled with 2μM CellTracker Green CMFDA (Invitrogen). 5000 labeled cells were injected along with 5×105 CD45.1+ total bone marrow cells into 6-8 week old 450rad irradiated CD45.1+ mice. 500 labeled HSCs were immediately analyzed for incorporated CMFDA by FACS. Four days after transplantation, recipients were sacrificed, and nucleated bone marrow cells were stained with antibodies against CD45.2, CD150, cKit, Sca-1, and lineage markers. Cells were analyzed using the same flow cytometer set up and experimental protocol as for the initial CMFDA incorporation analysis. Gates for tracing of up to seven divisions were set as previously described.54

Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP)

ChIP experiments were performed as previously described.28 Chromatin was isolated from murine HPC7 cells and sonicated using a Bioruptor (Diagenode, Denville, NJ). Immunoprecipitation was performed with 5μg Satb1 antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology Inc.) or 5μg normal rabbit IgG (Santa Cruz Biotechnology Inc.). Satb1 binding site SBS336 served as a positive control, an intronic IL2 site was used as a negative control.13 Satb1 binding to the Myc promoter was tested using previously published primers.21

ChIP on primary cells was performed using the Low Cell# ChIP kit (Diagenode, Denville NJ). CD45+CD150+ LSKs were sorted from the bone marrow of a pool of recipients of Satb1−/− or wild-type cells >20 weeks after transplantation. Chromatin was isolated and sonicated using a Bioruptor sonicator. Immunoprecipitation was performed with chromatin from 50,000 sorted cells and 2μg of H3K4me3, H3K27me3 antibodies, or normal rabbit IgG (all from Qiagen). For primers see Supplementary Table S3.

Lentivirus-mediated Satb1 restoration

CD150+CD48− LSKs were isolated from wild-type and Satb1−/− embryos at E17-18.5 and infected with lentiviral particles expressing Satb1 or empty vector alone (pCAD-IRES-GFP) in Cellgro medium containing 50ng/ml mrSCF, 50ng/ml mrTPO, and 8μg/ml polybrene (Sigma) as previously described15. Viable, GFP+ cells were sorted by FACS (Cell purity >98%, viability >85%).

Numb knock-down

Wild-type or Satb1−/− CD45.2+CD150+CD48− LSKs were isolated from recipient mice 16 and 20 weeks after transplantation and transduced with lentiviral shRNAs targeting murine Numb or a non-targeting control (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) by spin infection. Supernatant was replaced with growth medium (Cellgro containing 50ng/ml mrSCF, 50ng/ml mrTPO) after 4hrs and HSCs were cultured for 32hrs. Cells were plated in MethoCult M3434 GF+ containing 1μg/ml puromycin (Sigma). Colonies were scored and mRNA expression was measured 7-10 days after plating.

Myc inhibition

Wild-type and Satb1−/− CD45.2+CD150+CD48− LSKs were isolated from recipient mice 16 and 20 weeks after transplantation. Cells were treated with 10058-F4 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA), or JQ1 (kindly provided by Dr. J. Bradner) in Cellgro medium containing 50ng/ml mrSCF and 50ng/ml mrTPO for 48hrs. 100× pre-dilutions of each inhibitor were prepared in DMSO and added 1:100 to the culture medium of HSCs. 1% DMSO was added to the mock-treated control cells. After 48hr treatment, cells were plated in MethoCult M3434 GF+. Colonies were scored after 7-10 days.

Enhanced Reduced Representation Bisulfite Sequencing (ERRBS)

ERRBS55 was performed on sorted, Satb1−/− and wild-type CD45.2+CD150+ LSKs, and wild-type CD45.2+CD150− LSKs >20 weeks after transplantation. 10ng of DNA was digested with MspI. End repair and ligation of paired end Illumina sequencing adaptors was performed, followed by size selection (150-400bp) using gel extraction (Qiagen), and bisulfite treatment using the EZ DNA Methylation Kit (Zymo Research). PCR amplification using Illumina PCR PE1.0 and 2.0 primers was followed by library product isolation using AMPure XP beads (Agencort). Quality control was performed using quantitation on a Qubit 2.0 fluorometer (Invitrogen) and library visualization using Quant-iT dsDNA HS Assay Kit (Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer). The amplified libraries were sequenced using a 50bp single end read run on a HiSeq2000 (Illumina). Image capture, analysis, and base calling were performed using CASAVA 1.8 (Illumina). Read alignment at CpGs was performed using FAR software (http://sourceforge.net/projects/theflexibleadap/) for adaptor filtering, bismark56 for whole genome alignment against the mm9 genome, and methylation level calls were performed on reads with a phred quality score >20 and 10 or 5-fold coverage.

Analysis of ERRBS data

Methylation call files were analyzed using methylKit (v.0.5.3)57 in R/Bioconductor (v. 2.15.2) using non-overlapping 1kb-sized differentially methylated regions (DMRs) (10× coverage, >10% differential methylation, q<0.001). Differential methylation was assessed between wild-type and Satb1−/− CD150+ LSKs, and between wild-type CD150+ LSKs and wild-type CD150− LSKs. DMRs were annotated using UCSC for CpG islands, CpG shores (2kb up- and downstream from CpG islands), and isolated CpG, as well as RefSeq genes from mm9. Promoters were considered as 5kb upstream of transcription start sites; regions farther than 5kb up- or downstream of RefSeq genes were considered intergenic. Region overlaps were determined using bedtools.58 Overlap of “commitment DMRs” (between wild-type HSCs and MPPs) and “Satb1−/− HSC DMRs” (between Satb1−/− and wild-type HSCs), was determined using bismark methylation calls with a minimum coverage of 5 reads per DMC (q<0.001, >25% differential methylation).

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis of group comparisons was performed using Student’s t-test in Excel, Graph Pad Prism. Statistical enrichment analysis was performed using hypergeometrical testing in R.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank T. Kohwi-Shigematsu, E. Passegué, M. Alberich-Jordá and the members of the Steidl laboratory for helpful discussions and suggestions. We are grateful to G. Simkin, and S. Narayanagari of the Einstein Human Stem Cell FACS and Xenotransplantation Facility, P. Schultes, C. Sheridan and the Epigenomics Core Facility of Weill Cornell Medical College for expert technical assistance. We thank J. Bradner for providing JQ1. B.W. is the recipient of an American Cancer Society – J.T. Tai and Company, Inc. Postdoctoral Fellowship (121366-PF-12-89-01-TBG). F.G.B. is the recipient of a Sass Foundation Judah Folkman Fellowship and is supported by the National Cancer Institute (1K08CA169055-01). This work was further supported by individual fellowships of the National Institutes of Health to U.C.O. (F31CA162770) and A.P. (F30HL117545), a Howard Temin Award of the National Cancer Institute (R00CA131503, to U.S.), and NYSTEM research grants (C024306, C026416, N11G-041, to U.S.). U.S. is the Diane and Arthur B. Belfer Faculty Scholar in Cancer Research of the Albert Einstein College of Medicine.

Footnotes

Author Contributions B.W. and U.S. designed the study and experiments. B.W., T.O.V., F.G.B., T.D.B., J.M., and T.T. conducted experiments. B.W., T.O.V., J.M., B.B., F.G.B., A.P., L.B., U.C.O., R.S., T.T., M.R., A.V., M.E.F., A.M. and U.S. interpreted experiments. B.B. and L.B. performed statistical analysis of microarray data. B.B. and F.G.B. performed statistical analysis of ERRBS data. B.W. and U.S. wrote the manuscript.

Access codes for microarray and ERRBS data Microarray and ERRBS data sets are available online at http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/. Access code for data obtained by microarray is GSE44107. ERRBS data access code is GSE44304.

REFERENCES

- 1.Till JE, McCulloch EA. A direct measurement of the radiation sensitivity of normal mouse bone marrow cells. Radiat. Res. 1961;175:145–149. doi: 10.1667/rrxx28.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.BeckerR AJ, McCulloch EA, Till JE. Cytological demonstration of the clonal nature of spleen colonies derived from transplanted mouse marrow cells. Nature. 1963;197:452–454. doi: 10.1038/197452a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Spangrude GJ, Heimfeld S, Weissman IL. Purification and characterization of mouse hematopoietic stem cells. Science. 1988;241:58–62. doi: 10.1126/science.2898810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Seita J, Weissman IL. Hematopoietic stem cell: self-renewal versus differentiation. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Syst. Biol. Med. 2010;2:640–653. doi: 10.1002/wsbm.86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zeng H, Yucel R, Kosan C, Klein-Hitpass L, Moroy T. Transcription factor Gfi1 regulates self-renewal and engraftment of hematopoietic stem cells. EMBO J. 2004;23:4116–4125. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Perry JM, Li L. Self-renewal versus transformation: Fbxw7 deletion leads to stem cell activation and leukemogenesis. Genes Dev. 2008;22:1107–1109. doi: 10.1101/gad.1670708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Antonchuk J, Sauvageau G, Humphries RK. HOXB4-induced expansion of adult hematopoietic stem cells ex vivo. Cell. 2002;109:39–45. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00697-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chang KC, et al. Interplay between the transcription factor Zif and aPKC regulates neuroblast polarity and self-renewal. Dev. Cell. 2010;19:778–785. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2010.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Scheel C, et al. Paracrine and autocrine signals induce and maintain mesenchymal and stem cell states in the breast. Cell. 2011;145:926–940. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.04.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Broske AM, et al. DNA methylation protects hematopoietic stem cell multipotency from myeloerythroid restriction. Nat. Genet. 2009;41:1207–1215. doi: 10.1038/ng.463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sun Y, Hu J, Zhou L, Pollard SM, Smith A. Interplay between FGF2 and BMP controls the self-renewal, dormancy and differentiation of rat neural stem cells. J. Cell. Sci. 2011;124:1867–1877. doi: 10.1242/jcs.085506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Alvarez JD, et al. The MAR-binding protein SATB1 orchestrates temporal and spatial expression of multiple genes during T-cell development. Genes Dev. 2000;14:521–535. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yasui D, Miyano M, Cai S, Varga-Weisz P, Kohwi-Shigematsu T. SATB1 targets chromatin remodelling to regulate genes over long distances. Nature. 2002;419:641–645. doi: 10.1038/nature01084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Beyer M, et al. Repression of the genome organizer SATB1 in regulatory T cells is required for suppressive function and inhibition of effector differentiation. Nat. Immunol. 2011;12:898–907. doi: 10.1038/ni.2084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Steidl U, et al. A distal single nucleotide polymorphism alters long-range regulation of the PU.1 gene in acute myeloid leukemia. J. Clin. Invest. 2007;117:2611–2620. doi: 10.1172/JCI30525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Savarese F, et al. Satb1 and Satb2 regulate embryonic stem cell differentiation and Nanog expression. Genes Dev. 2009;23:2625–2638. doi: 10.1101/gad.1815709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Han HJ, Russo J, Kohwi Y, Kohwi-Shigematsu T. SATB1 reprogrammes gene expression to promote breast tumour growth and metastasis. Nature. 2008;452:187–193. doi: 10.1038/nature06781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lakshminarayana Reddy CN, Vyjayanti VN, Notani D, Galande S, Kotamraju S. Down-regulation of the global regulator SATB1 by statins in COLO205 colon cancer cells. Mol. Med. Report. 2010;3:857–861. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2010.338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Selinger CI, et al. Loss of special AT-rich binding protein 1 expression is a marker of poor survival in lung cancer. J. Thorac. Oncol. 2011;6:1179–1189. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e31821b4ce0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cai S, Han HJ, Kohwi-Shigematsu T. Tissue-specific nuclear architecture and gene expression regulated by SATB1. Nat. Genet. 2003;34:42–51. doi: 10.1038/ng1146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cai S, Lee CC, Kohwi-Shigematsu T. SATB1 packages densely looped, transcriptionally active chromatin for coordinated expression of cytokine genes. Nat. Genet. 2006;38:1278–1288. doi: 10.1038/ng1913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Challen GA, Boles N, Lin KK, Goodell MA. Mouse hematopoietic stem cell identification and analysis. Cytometry A. 2009;75:14–24. doi: 10.1002/cyto.a.20674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Matsumoto A, et al. P57 is Required for Quiescence and Maintenance of Adult Hematopoietic Stem Cells. Cell. Stem Cell. 2011;9:262–271. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2011.06.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Passegue E, Wagers AJ, Giuriato S, Anderson WC, Weissman IL. Global analysis of proliferation and cell cycle gene expression in the regulation of hematopoietic stem and progenitor cell fates. J. Exp. Med. 2005;202:1599–1611. doi: 10.1084/jem.20050967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Takizawa H, Regoes RR, Boddupalli CS, Bonhoeffer S, Manz MG. Dynamic variation in cycling of hematopoietic stem cells in steady state and inflammation. J. Exp. Med. 2011;208:273–284. doi: 10.1084/jem.20101643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wilson A, et al. Hematopoietic stem cells reversibly switch from dormancy to self-renewal during homeostasis and repair. Cell. 2008;135:1118–1129. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.10.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Morita Y, Ema H, Nakauchi H. Heterogeneity and hierarchy within the most primitive hematopoietic stem cell compartment. J. Exp. Med. 2010;207:1173–1182. doi: 10.1084/jem.20091318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kharas MG, et al. Musashi-2 regulates normal hematopoiesis and promotes aggressive myeloid leukemia. Nat. Med. 2010;16:903–908. doi: 10.1038/nm.2187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wu M, et al. Imaging hematopoietic precursor division in real time. Cell. Stem Cell. 2007;1:541–554. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2007.08.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rhyu MS, Jan LY, Jan YN. Asymmetric distribution of numb protein during division of the sensory organ precursor cell confers distinct fates to daughter cells. Cell. 1994;76:477–491. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90112-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Spana EP, Doe CQ. Numb antagonizes Notch signaling to specify sibling neuron cell fates. Neuron. 1996;17:21–26. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80277-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rebeiz M, Miller SW, Posakony JW. Notch regulates numb: integration of conditional and autonomous cell fate specification. Development. 2011;138:215–225. doi: 10.1242/dev.050161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Subramanian A, et al. Gene set enrichment analysis: a knowledge-based approach for interpreting genome-wide expression profiles. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2005;102:15545–15550. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0506580102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zeller KI, et al. Global mapping of c-Myc binding sites and target gene networks in human B cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2006;103:17834–17839. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0604129103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Huang MJ, Cheng YC, Liu CR, Lin S, Liu HE. A small-molecule c-Myc inhibitor, 10058-F4, induces cell-cycle arrest, apoptosis, and myeloid differentiation of human acute myeloid leukemia. Exp. Hematol. 2006;34:1480–1489. doi: 10.1016/j.exphem.2006.06.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Delmore JE, et al. BET bromodomain inhibition as a therapeutic strategy to target c-Myc. Cell. 2011;146:904–917. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.08.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pinto do OP, Kolterud A, Carlsson L. Expression of the LIM-homeobox gene LH2 generates immortalized steel factor-dependent multipotent hematopoietic precursors. EMBO J. 1998;17:5744–5756. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.19.5744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mahmoudi T, et al. The kinase TNIK is an essential activator of Wnt target genes. EMBO J. 2009;28:3329–3340. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2009.285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fazzio TG, Huff JT, Panning B. An RNAi screen of chromatin proteins identifies Tip60-p400 as a regulator of embryonic stem cell identity. Cell. 2008;134:162–174. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.05.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Miyazaki M, et al. The opposing roles of the transcription factor E2A and its antagonist Id3 that orchestrate and enforce the naive fate of T cells. Nat. Immunol. 2011;12:992–1001. doi: 10.1038/ni.2086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wontakal SN, et al. A large gene network in immature erythroid cells is controlled by the myeloid and B cell transcriptional regulator PU.1. PLoS Genet. 2011 doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1001392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Nerlov C, Graf T. PU.1 induces myeloid lineage commitment in multipotent hematopoietic progenitors. Genes Dev. 1998;12:2403–2412. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.15.2403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Orford KW, Scadden DT. Deconstructing stem cell self-renewal: genetic insights into cell-cycle regulation. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2008;9:115–128. doi: 10.1038/nrg2269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cheng T, et al. Hematopoietic stem cell quiescence maintained by p21cip1/waf1. Science. 2000;287:1804–1808. doi: 10.1126/science.287.5459.1804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Massague J. G1 cell-cycle control and cancer. Nature. 2004;432:298–306. doi: 10.1038/nature03094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Xi R, Xie T. Stem cell self-renewal controlled by chromatin remodeling factors. Science. 2005;310:1487–1489. doi: 10.1126/science.1120140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Reavie L, et al. Regulation of hematopoietic stem cell differentiation by a single ubiquitin ligase-substrate complex. Nat. Immunol. 2010;11:207–215. doi: 10.1038/ni.1839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Santaguida M, et al. JunB protects against myeloid malignancies by limiting hematopoietic stem cell proliferation and differentiation without affecting self-renewal. Cancer. Cell. 2009;15:341–352. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2009.02.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Klinakis A, et al. A novel tumour-suppressor function for the Notch pathway in myeloid leukaemia. Nature. 2011;473:230–233. doi: 10.1038/nature09999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Li QQ, et al. Overexpression and involvement of special AT-rich sequence binding protein 1 in multidrug resistance in human breast carcinoma cells. Cancer. Sci. 2010;101:80–86. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2009.01372.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kossenkov AV, Ochs MF. Matrix factorization for recovery of biological processes from microarray data. Methods Enzymol. 2009;467:59–77. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(09)67003-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Maggio-Price L, Wolf NS, Priestley GV, Pietrzyk ME, Bernstein SE. Evaluation of stem cell reserve using serial bone marrow transplantation and competitive repopulation in a murine model of chronic hemolytic anemia. Exp. Hematol. 1988;16:653–659. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Szilvassy SJ, Nicolini FE, Eaves CJ, Miller CL. Quantitation of murine and human hematopoietic stem cells by limiting-dilution analysis in competitively repopulated hosts. Methods Mol. Med. 2002;63:167–187. doi: 10.1385/1-59259-140-X:167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lyons AB. Analysing cell division in vivo and in vitro using flow cytometric measurement of CFSE dye dilution. J. Immunol. Methods. 2000;243:147–154. doi: 10.1016/s0022-1759(00)00231-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Akalin A, et al. Base-pair resolution DNA methylation sequencing reveals profoundly divergent epigenetic landscapes in acute myeloid leukemia. PLoS Genet. 2012;8:e1002781. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Krueger F, Andrews SR. Bismark: a flexible aligner and methylation caller for Bisulfite-Seq applications. Bioinformatics. 2011;27:1571–1572. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btr167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Akalin A, et al. methylKit: a comprehensive R package for the analysis of genome-wide DNA methylation profiles. Genome Biol. 2012;13:R87. doi: 10.1186/gb-2012-13-10-r87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Quinlan AR, Hall IM. BEDTools: a flexible suite of utilities for comparing genomic features. Bioinformatics. 2010;26:841–842. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btq033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.