Abstract

Background

Temper modulation problems are both a hallmark of early childhood and a common mental health concern. Thus, characterizing specific behavioral manifestations of temper loss along a dimension from normative misbehaviors to clinically significant problems is an important step toward identifying clinical thresholds.

Methods

Parent-reported patterns of temper loss were delineated in a diverse community sample of preschoolers (n = 1,490). A developmentally sensitive questionnaire, the Multidimensional Assessment of Preschool Disruptive Behavior (MAP-DB), was used to assess temper loss in terms of tantrum features and anger regulation. Specific aims were: (a) document the normative distribution of temper loss in preschoolers from normative misbehaviors to clinically concerning temper loss behaviors, and test for sociodemographic differences; (b) use Item Response Theory (IRT) to model a Temper Loss dimension; and (c) examine associations of temper loss and concurrent emotional and behavioral problems.

Results

Across sociodemographic subgroups, a unidimensional Temper Loss model fit the data well. Nearly all (83.7%) preschoolers had tantrums sometimes but only 8.6% had daily tantrums. Normative misbehaviors occurred more frequently than clinically concerning temper loss behaviors. Milder behaviors tended to reflect frustration in expectable contexts, whereas clinically concerning problem indicators were unpredictable, prolonged, and/or destructive. In multivariate models, Temper Loss was associated with emotional and behavioral problems.

Conclusions

Parent reports on a developmentally informed questionnaire, administered to a large and diverse sample, distinguished normative and problematic manifestations of preschool temper loss. A developmental, dimensional approach shows promise for elucidating the boundaries between normative early childhood temper loss and emergent psychopathology.

Keywords: Developmental psychopathology, temper tantrums, disruptive behavior, preschool psychopathology, dimensional

Introduction

Temper dysregulation is a component of many developmental psychopathologies, with increasing evidence for prediction of both disruptive and mood syndromes (Burke, Hipwell, & Loeber, 2010; Stringaris, Cohen, Pine, & Leibenluft, 2009; Stringaris & Goodman, 2009). However, four key gaps impede its systematic study in developmental psychopathology research (Stringaris, 2011). First, the salient behaviors must be operationalized within a theoretically informed developmental framework. Second, empirically derived parameters are needed to differentiate when temper loss is ‘outside of normal limits’ (American Psychiatric Association, 1994), particularly in early childhood. Third, robust measurement tools are essential to generate an evidence base defining ‘when to worry.’ Finally, it is important to move beyond theory to empirically demonstrate a temper loss dimensional continuum.

Here we tested a developmentally specified dimensional model of preschool temper loss. Temper loss is defined as the pattern and modulation of expressions of overt anger, including both temper tantrums and regulation of angry mood. Early childhood is an important period for testing the dimensionality of temper loss because of the high degree of overlap between normative misbehaviors and clinical symptoms (Cole, Michel, & Teti, 1994). We emphasize tantrums due to their centrality as early childhood normative misbehaviors because they are common mental health concerns at preschool age and because they are discrete, simple, but potent markers of early clinical concern.

The limited existing research indicates that normative temper outbursts differ from clinically concerning ones in frequency, duration, quality, context, and triggering events (Belden, Thompson, & Luby, 2008; Bhatia et al., 1990; Osterman & Bjorkqvist, 2010; Wakschlag et al., 2007). However, these studies utilized narrative or observational methods (Einon & Potegal, 1994), and/or relied on small, nonrepresentative samples (Belden et al., 2008; Goodenough, 1931; Green, Whitney, & Potegal, 2011). Furthermore, because subjective frequency ratings were used, the actual frequency of normative misbehaviors is unknown. In clinically enriched samples, data from the Preschool Age Psychiatric Assessment (PAPA) interview and observations from the Disruptive Behavior Diagnostic Observation Schedule (DB-DOS) indicate that higher tantrum frequency, greater duration, tantrums outside the home, and ‘dysregulated’ tantrums distinguish preschoolers with behavioral and mood disorders (Belden et al., 2008; Egger, 2003; Wakschlag et al., 2008). On the basis of these data, we theorized a dimensional continuum of temper loss, ranging from mild forms of normative misbehaviors (e.g., losing temper or having a tantrum when frustrated, angry, or upset) to ‘problem indicators’ suggesting clinically significant temper loss (e.g., breaking or destroying things during a temper tantrum). The placement of behaviors along this dimension was based on both quality and frequency. Thus, even a normative misbehavior might be clinically significant when exhibited frequently.

We tested this theoretical continuum by applying Item Response Theory (IRT) to Temper Loss items generated within a theoretically derived, developmentally sensitive questionnaire about preschool disruptive behavior, the Multidimensional Assessment of Preschool Disruptive Behavior (MAP-DB). IRT describes item response patterns on the basis of a latent continuum and has been used to refine psychological symptom measures (Reise & Waller, 2009). IRT’s advantages include the ability to scale items and people on the same underlying dimensional continuum. That is, individual items are assigned a severity score and an individual child’s score on the dimension is an estimate of his/her overall severity of temper loss. IRT also provides detailed information on the performance of individual items (i.e., slope and threshold parameters) and the capacity to model measurement error more accurately. Item response functions (IRF) were used to evaluate the probability of a particular frequency (e.g., ‘Every day of the week’) being endorsed at various levels of underlying severity. For example, we hypothesized that problem indicators occurring at a lower frequency would be indicative of more severe temper loss, whereas theorized normative misbehaviors would have to occur much more frequently to be severe.

Aims were to: (a) document the frequency of Temper Loss behaviors in preschoolers and test for differences by child age, gender, race/ethnicity, and poverty status; (b) use IRT to test the fit of the data to a unidimensional model of Temper Loss, ranging from normative misbehaviors to atypical/unusual behaviors, and to identify the ordering of Temper Loss behaviors along this continuum; and (c) examine associations between severity on the Temper Loss dimension and concurrent emotional and behavioral problems.

Methods

Sample & procedures

The Multidimensional Assessment of Preschoolers Study (‘MAPS’) is comprised of a large sample of children recruited from the waiting rooms of five pediatric clinics in the greater Chicago area. Parents and legal guardians of 3- to 5-year-old children were eligible to participate and asked to complete a questionnaire (available in English or Spanish) about their child’s behavior and development. Recruitment continued consecutively until sample stratification (by child age, gender, race/ethnicity, and poverty status [using federal poverty guidelines based on annual household income and household size]) was complete (Barajas, Philipsen, & Brooks-Gunn, 2008). Parents could complete the questionnaire at the clinic, by mail or phone (most participated in the clinic). All procedures were approved by an institutional review board and legal guardians provided informed consent. A $20 incentive was provided for participation (plus $10 in-clinic completion bonus).

Of the 4,137 individuals approached for screening, 176 (4.3%) declined. Of the 3,961 screened, 1,815 (46%) were eligible. 1,606 (88.5%) eligible parents consented, and 1,516 (83.5%) completed surveys. The most common reasons for ineligibility were: child age (n = 1,076), filled sociodemographic strata (n = 432), prior participation (n = 406), and not legal guardian (n = 134). Twenty-six children reported to be diagnosed with or receiving services for autism or pervasive developmental delay were excluded from data analysis. The final sample was 1,490.

Respondents were biological mothers (91%), biological fathers (7%), and relatives or adoptive parents (2%). Sixty-nine percent of parents were high school educated, 23% college educated, and 50% were married. The sample was distributed fairly evenly by child gender (51% boys, 49% girls), age (35% 3-year olds, 36% 4-year olds, and 29% 5-year olds), race/ethnicity (36% African American, 36% Hispanic, 27% non-Hispanic White, and 1% other), and poverty status (42% poor, 58% nonpoor).

Measures

Temper Loss and Aggression scales from the MAP-DB (MAP-DB; Wakschlag et al., 2010) were used. This measure was developed by a team of experts in early childhood clinical assessment and treatment, developmental epidemiology, and disruptive behavior across the life span. Items are rated in terms of frequency over the past month: 0 = Never in the past month; 1 = Rarely (less than weekly); 2 = Some days (1–3 days per week); 3 = Most days (4–6 days); 4 = Daily; and 5 = Multiple times per day. Focus groups, led by a clinical psychologist with expertise in preschool disruptive behavior, with diverse groups of parents and teachers, yielded consensus that the terms ‘fall-out’ and ‘melt-down’ are commonly used to refer to temper tantrums.

MAP-DB Temper Loss items were generated across two broad content areas: temper tantrums and anger regulation (Table 1). Each content area included items theorized as normative misbehaviors and problem indicators. Tantrums were assessed with 14 items capturing behavioral expression (e.g., ‘has a tantrum,’ ‘fall-out’ or melt-down,’ ‘has a tantrum until exhausted’), interactional context (e.g., with parents vs. other adults), and triggering events (e.g., during routines vs. ‘out of the blue’). There were eight anger regulation items (e.g., ‘becomes frustrated easily,’ ‘has a hot/explosive temper’). Cronbach’s alpha was excellent (α = .97).

Table 1.

Distribution of MAP-DB Temper Loss items (N = 1,490)

| Percent (Frequency) |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Itema | Never in past month |

Rarely (Less than once per week) |

Some (1–3) days of the week |

Most (4–6) days of the week |

Every day of the week |

Many times each day |

| Tantrums | ||||||

| Behavioral expression | ||||||

| 1. Have a temper tantrum, fall-out, or melt-down | 44.5 (662) | 34.0 (506) | 13.3 (198) | 3.8 (56) | 2.0 (30) | 2.4 (35) |

| 2. Stamp feet or hold breath during a temper tantrum, fall-out, or melt-down | 54.5 (809) | 26.3 (390) | 12.1 (180) | 3.8 (57) | 1.3 (19) | 2.0 (30) |

| 3. Have a temper tantrum, fall-out, or meltdown that lasted more than 5 minutes | 58.8 (874) | 27.2 (404) | 10.0 (148) | 1.7 (26) | 0.8 (12) | 1.5 (22) |

| 4. Keep on having a temper tantrum, fall-out, or melt-down, even when you tried to help him/her calm down | 66.3 (985) | 23.2 (345) | 6.4 (95) | 1.6 (24) | 0.8 (12) | 1.6 (24) |

| 5. Break or destroy things during a temper tantrum, fall-out, or melt-down | 71.7 (1067) | 19.0 (283) | 5.4 (80) | 1.5 (22) | 0.9 (14) | 1.5 (22) |

| 6. Have a temper tantrum, fall-out, or melt-down until exhausted | 74.2 (1104) | 16.7 (249) | 5.4 (80) | 1.5 (23) | 0.7 (11) | 1.3 (20) |

| 7. Hit, bite, or kick during a temper tantrum, fall-out, or melt-down | 76.5 (1138) | 15.3 (227) | 4.3 (64) | 2.1 (31) | 0.7 (10) | 1.1 (17) |

| Interactional context | ||||||

| 8. Lose temper or have a tantrum with you or other parent | 44.5 (662) | 34.9 (518) | 13.4 (199) | 3.6 (54) | 1.7 (26) | 1.8 (27) |

| 9. Lose temper or have a tantrum with other adults (e.g., teacher, babysitter, family member) | 63.8 (946) | 26.2 (388) | 6.7 (100) | 1.3 (20) | 0.6 (9) | 1.3 (19) |

| Triggers | ||||||

| 10. Lose temper or have a tantrum when frustrated, angry, or upset | 39.2 (582) | 38.2 (567) | 14.4 (214) | 4.4 (65) | 1.6 (24) | 2.3 (34) |

| 11. Lose temper or have a tantrum when tired, hungry, or sick | 40.1 (595) | 34.8 (516) | 16.9 (251) | 4.6 (68) | 1.4 (21) | 2.2 (32) |

| 12. Lose temper or have a tantrum to get something he or she wanted | 41.1 (611) | 35.8 (532) | 14.5 (215) | 4.5 (67) | 1.7 (25) | 2.4 (35) |

| 13. Lose temper or have a tantrum during daily routines, such as bedtime, mealtime, or getting dressed | 41.6 (619) | 33.9 (504) | 16.9 (251) | 3.2 (48) | 2.2 (33) | 2.2 (33) |

| 14. Lose temper or have a tantrum ‘out of the blue’ or for no reason | 73.7 (1094) | 18.0 (268) | 5.2 (77) | 1.2 (18) | 0.7 (11) | 1.1 (17) |

| Anger regulation | ||||||

| 15. Become frustrated easily | 34.8 (517) | 36.2 (538) | 18.8 (279) | 5.2 (78) | 2.2 (33) | 2.8 (41) |

| 16. Yell angrily at someone | 37.3 (555) | 38.6 (575) | 15.9 (237) | 4.3 (64) | 1.8 (27) | 2.0 (30) |

| 17. Act irritable | 42.5 (632) | 36.3 (539) | 14.9 (221) | 3.6 (53) | 1.3 (19) | 1.5 (22) |

| 18. Have difficulty calming down when angry | 47.3 (704) | 33.1 (492) | 12.8 (190) | 3.6 (53) | 1.3 (20) | 1.9 (29) |

| 19. Have a short fuse (become angry quickly) | 48.2 (718) | 31.3 (466) | 12.7 (189) | 3.9 (58) | 1.8 (27) | 2.1 (31) |

| 20. Get extremely angry | 62.5 (930) | 24.5 (365) | 8.0 (119) | 2.0 (29) | 1.2 (18) | 1.7 (26) |

| 21. Have a hot or explosive temper | 67.0 (995) | 21.4 (318) | 6.3 (93) | 2.3 (34) | 1.3 (19) | 1.7 (25) |

| 22. Stay angry for a long time | 69.2 (1029) | 24.3 (361) | 4.0 (60) | 1.1 (16) | 0.4 (6) | 1.0 (15) |

| Tantrum compositeb | 16.3 (241) | 38.5 (570) | 27.8 (412) | 8.9 (132) | 3.8 (56) | 4.8 (71) |

Italics denote items theorized to be normative misbehaviors. Others items are theorized as problem indicators.

Tantrum composite based on maximum (highest frequency) across the 14 tantrum items.

The 19-item MAP-DB Aggression scale score was examined as a behavioral correlate of Temper Loss. This scale reflects aggressive behaviors (e.g., ‘hit, pinch, kick’) occurring in different contexts (e.g., with peers, parents, or other adults) and triggers (e.g., ‘to get back at some-one’). Items did not overlap with Temper Loss items. Good fit was established with ordinal confirmatory factor analysis (CFA), (CFI = 0.967, TLI = 0.963, and RMSEA = 0.065). Cronbach’s alpha was excellent (α = .95). Aggression severity was generated with IRT.

Behavioral and emotional correlates of Temper Loss were also measured with the preschool version of the Infant-Toddler Social and Emotional Assessment (ITSEA; Carter & Briggs-Gowan, 2006), which has acceptable internal consistency, test-retest reliability and validity, and has been used with preschoolers (Briggs-Gowan & Carter, 2007; Carter & Briggs-Gowan, 2006). Items are rated from 0 = Not true/Rarely to 2 = Very True/Often. A 15-item Anxiety scale including general anxiety and separation distress items, an 8-item Depression/Withdrawal scale, and a 10-item Activity/Impulsivity scale were used. Internal consistency was acceptable (α = .69–.79).

IRT and psychometric analyses

IRT analyses using Graded Response Model (GRM; Samejima, 1969) were conducted to calibrate Temper Loss items and generate severity scores. Calibration fits an IRT model to the data and estimates the item parameters and person scores specified by the model. Severity scores, or Theta (θ), reflect the underlying Temper Loss construct. Severity score estimates were obtained via the maximum a posteriori (MAP) estimator with a standard normal prior. Thetas are centered on 0 with a standard deviation of 1.0 (analogous to standard z-scores). The marginal maximum likelihood estimator implemented in MULTILOG 7.02 (Thissen, Chen, & Bock, 2003) was used for estimating the GRM item parameters reflecting the slope (a) and category thresholds (b1, b2,…, b5) for each item. The slope indicates how well the item discriminates/differentiates severity levels, or the rate at which the probability of endorsing a given frequency or higher changes as underlying severity level changes. For example, a high-positive slope value indicates that the item is effective in discriminating persons at different severity levels. Category thresholds indicate the severity level at which there is a 50% probability of endorsing a given category or higher. The mean of the thresholds for each item was computed as the item location on the severity continuum that included all items.

A CFA was conducted using the robust weighted least squares (WLSMV) estimator in Mplus (Muthén & Muthén, 2007) to test whether the data fit a unidimensional model. Goodness of fit was assessed using three indices: the Comparative Fit Index (CFI), the Tucker Lewis Index (TLI), and the Root Mean Squared Error of Approximation (RMSEA). CFI and TLI values of 0.95 or greater indicate a good fit. RMSEA values in the range 0.06–0.08 or below indicate acceptable fit, and values ≥.1 should be rejected (Browne & Cudeck, 1993; Hu & Bentler, 1999).

Results

Aim I: Document the normative distribution of Temper Loss behaviors and test for sociodemographic differences

Simple item-level analyses were conducted to examine Temper Loss patterns across the full sample and sociodemographic subgroups. Given the large sample size, a significance threshold of p < .01 was used for all analyses.

Normative patterns of temper loss

As predicted, behaviors conceptualized as normative misbehaviors were more common than problem indicators (Table 1). All nine normative misbehavior items were exhibited by most children at least once during the past month. For example, 55.5% of children had a tantrum with their parents and 60.8% had a tantrum when ‘frustrated, angry or upset.’ In contrast, most problem indicators were not exhibited by most children. For example, in the past month, 23.5% had displayed aggression (‘hit, bite or kick’) during a tantrum and 36.2% had a tantrum with a nonparental adult. However, three hypothesized problem indicators were displayed by more than 50% of children over the past month (‘acted irritable,’ had ‘difficulty calming down when angry,’ and/or had a ‘short fuse’).

Strikingly, a consistent pattern was observed across all 22 Temper Loss behaviors (including normative misbehaviors): fewer than 10% of children exhibited any given behavior most days of the week. An overall tantrum composite, summarizing across all tantrum items, revealed that most preschoolers (83.7%) exhibited some form of tantrum in the past month, but daily tantrums of any form were not normative (8.6%).

Sociodemographic subgroup patterns

Distributions were similar across child gender, age, ethnicity, and poverty status (Table S1). Slightly more than one third of behaviors showed age trends (with highest frequency in 3-year olds). Only two items exhibited gender differences (more frequent in boys). A number of small, but significant differences also were observed by race/ethnicity and poverty status (Table S1). However, across all subgroups, it was uncommon for Temper Loss behaviors to occur daily.

Aim II: Test the hypothesis that Temper Loss falls along a theorized severity dimension using IRT methods

IRT analyses were conducted to assess dimensionality and to construct a scale measuring the underlying Temper Loss trait. Although we organized Temper Loss items around temper tantrum and anger regulation content areas, IRT indicated that Temper Loss was a unidimensional scale. CFA produced a satisfactory model fit (CFI = 0.965, TLI = 0.961, and RMSEA = 0.088). All factor loadings were in the very high range (0.721–0.897) and there was no evidence of spurious correlations between any pairs of items (all residual correlations substantially below 0.15).

The scale was calibrated with the GRM. Applying parameter estimates to item responses, individual Temper Loss trait scores (Theta) were obtained. The standard error estimates associated with these scores were generally small (mean = 0.21), except for children at the mildest end of the continuum who did not exhibit any Temper Loss over the past month. About 85% of individual trait scores were associated with standard error estimates less than 0.32 (analogous to reliability of 0.90 in classical test theory). Item slopes (Table 2) ranged from 1.94 to 3.71. ‘Lose temper or have a tantrum when frustrated, angry, or upset’ had the highest slope, indicating that this normative misbehavior item provides relatively good differentiation of underlying severity. The category thresholds (b1–b5) indicate roughly the severity level at which the transition from one response category to the next is likely to take place (e.g., from Never to Rarely). Higher thresholds indicate that, to be severe, a given item must be endorsed at a given response category or higher. In this sample, severity scores of 1.63 or higher are at or above the 95th percentile. This clinical level occurs at a higher frequency for normative misbehaviors (between most days and every day) than for problem indicators (between rarely and most days). Taking the example of ‘Lose temper or have a tantrum when frustrated, angry or upset,’ b2 = .75, indicating only modest severity needed to endorse some days (2–3 days a week) or higher, whereas b4 = 2.0, indicating that clinically significant severity is needed to endorse this item as occurring daily or higher. Comparing across items, b2 = 0.75 for this normative misbehavior in comparison with b2 = 1.97 for ‘Stay angry for a long time’ indicates that a lower level of severity is needed to endorse the normative misbehavior (former) as occurring some days or higher than is needed to endorse the problem indicator (latter) some days or higher.

Table 2.

Graded response model (GRM) item parameter estimates for Temper Loss items

| Category thresholds |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Slope |

Rarely or higher |

Some days of week or higher |

Most days or higher |

Every day or higher |

Many times a day |

Item Location |

||

| a | b1 | b2 | b3 | b4 | b5 | mean(b) | ||

| Tantrums | ||||||||

| Behavioral expression | ||||||||

| Have a temper tantrum, ‘fall-out’, or melt-down | 3.38 | −0.15 | 0.80 | 1.53 | 1.98 | 2.43 | 1.32 | |

| Stamp feet or hold breath during a temper tantrum, ‘fall-out’, or melt-down | 1.90 | 0.11 | 1.07 | 1.94 | 2.58 | 3.00 | 1.74 | |

| Have a temper tantrum, ‘fall-out’, or meltdown that lasted more than 5 min | 2.77 | 0.23 | 1.19 | 2.13 | 2.59 | 2.93 | 1.81 | |

| Keep on having a temper tantrum, ‘fall-out’, or melt-down, even when you tried to help him/her calm down. | 3.26 | 0.43 | 1.33 | 2.02 | 2.41 | 2.73 | 1.78 | |

| Break or destroy things during a temper tantrum, ‘fall-out’, or melt-down | 2.47 | 0.63 | 1.53 | 2.18 | 2.54 | 2.93 | 1.96 | |

| Have a temper tantrum, ‘fall-out’, or melt-down until exhausted | 2.77 | 0.70 | 1.51 | 2.16 | 2.57 | 2.95 | 1.98 | |

| Hit, bite, or kicks during a temper tantrum, ‘fall-out’, or melt-down | 2.44 | 0.81 | 1.62 | 2.16 | 2.74 | 3.11 | 2.09 | |

| Interactional context | ||||||||

| Lose temper or have a tantrum with you or other parent | 3.34 | −0.15 | 0.83 | 1.59 | 2.09 | 2.59 | 1.39 | |

| Lose temper or have a tantrum with other adults (e.g., teacher, babysitter, family member) | 2.51 | 0.38 | 1.47 | 2.28 | 2.68 | 2.99 | 1.96 | |

| Triggers | ||||||||

| Lose temper or have a tantrum when frustrated, angry, or upset | 3.71 | −0.28 | 0.75 | 1.45 | 2.00 | 2.42 | 1.27 | |

| Lose temper or have a tantrum when tired, hungry, or sick | 2.76 | −0.29 | 0.71 | 1.56 | 2.16 | 2.57 | 1.34 | |

| Lose temper or have a tantrum to get something he or she wanted | 3.12 | −0.24 | 0.77 | 1.53 | 2.09 | 2.50 | 1.33 | |

| Lose temper or have a tantrum during daily routines such as bedtime, mealtime, or getting dressed | 2.78 | −0.24 | 0.75 | 1.66 | 2.09 | 2.61 | 1.37 | |

| Lose temper or have a tantrum ‘out of the blue’ or for no reason | 2.91 | 0.67 | 1.53 | 2.21 | 2.60 | 3.02 | 2.01 | |

| Anger regulation | ||||||||

| Become frustrated easily | 1.94 | −0.51 | 0.68 | 1.66 | 2.27 | 2.76 | 1.37 | |

| Yell angrily at someone | 2.08 | −0.41 | 0.85 | 1.79 | 2.38 | 2.88 | 1.50 | |

| Act irritable | 1.99 | −0.25 | 0.97 | 1.99 | 2.66 | 3.18 | 1.71 | |

| Have difficulty calming down when angry | 2.23 | −0.09 | 1.00 | 1.86 | 2.45 | 2.88 | 1.62 | |

| Have a ‘short fuse’ (become angry quickly) | 2.51 | −0.07 | 0.93 | 1.69 | 2.22 | 2.71 | 1.50 | |

| Get extremely angry | 3.10 | 0.33 | 1.21 | 1.92 | 2.31 | 2.71 | 1.70 | |

| Have a hot or explosive temper | 3.18 | 0.45 | 1.27 | 1.84 | 2.26 | 2.69 | 1.70 | |

| Stay angry for a long time | 2.00 | 0.61 | 1.97 | 2.69 | 3.13 | 3.42 | 2.36 | |

Thresholds ≥1.63 indicate severity above the 95th percentile

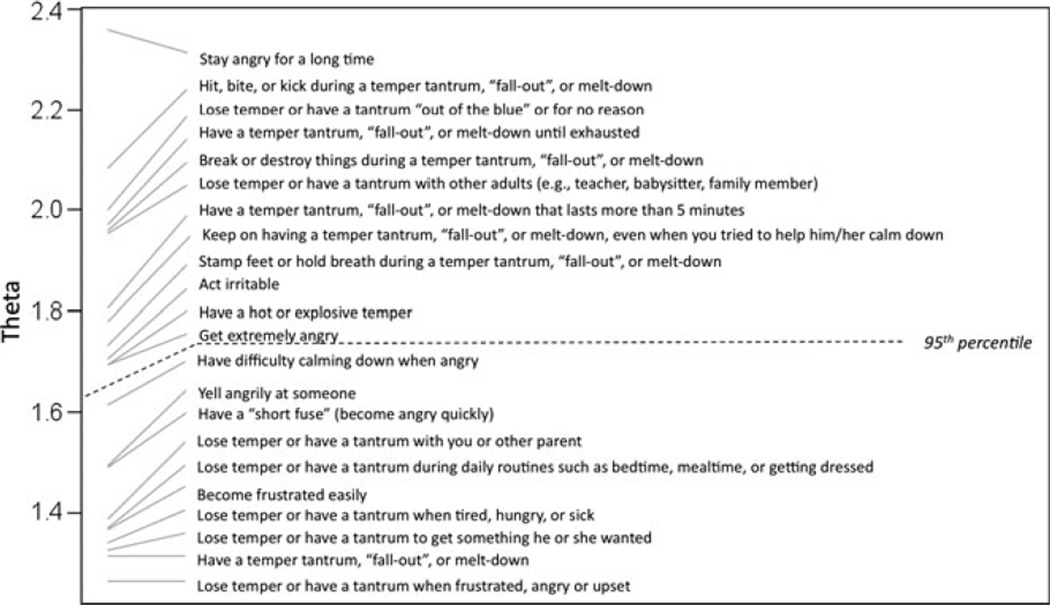

The GRM results also provide information about each item’s location on the severity continuum. Figure 1 illustrates the Temper Loss severity dimension, with item locations indicated along the continuum (the vertical axis). The item demarcating most severe temper loss was ‘Stay angry for a long time’ (location = 2.36), whereas the item representing the lowest level was ‘Lose temper or have a tantrum when frustrated, angry or upset’ (location = 1.26). The 12 items above the 95th percentile clinical threshold were all theorized problem indicators (Figure 1). These included manifestations of temper tantrums (e.g., ‘hit, bite or kick during tantrum,’ ‘have a tantrum that lasts more than 5 minutes’) and anger regulation (e.g., ‘stay angry for a long time,’ ‘have a hot or explosive temper’).

Figure 1.

Severity Values for Items Along the Temper Loss Dimension

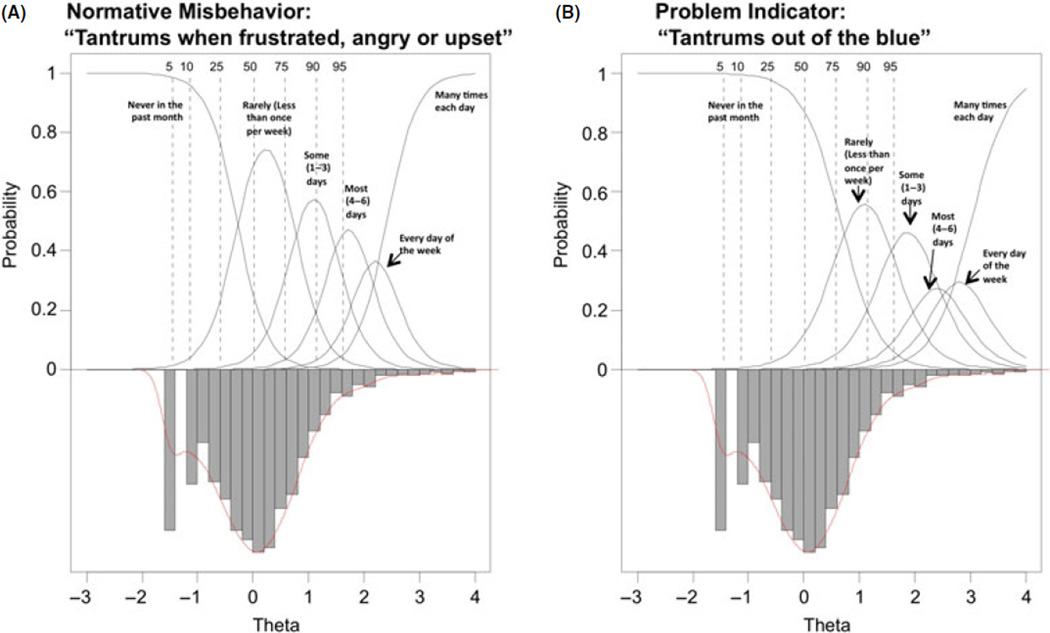

Figure 2 depicts IRFs for one item at the mild end of the continuum (normative misbehavior, 2A) and one item from the severe end (problem indicator, 2B), highlighting how frequency cutpoints for clinically significant problems are likely to vary depending on the nature of the Temper Loss behavior. The inverted bar graphs represent the distribution of Temper Loss scores across the underlying severity scale (Theta). The dotted vertical lines indicate the locations of selected percentiles along Theta. Finally, the thick solid lines signify the theorized IRFs as a function of Theta. Moving from left to right on the severity continuum, the probability of endorsing a higher frequency response increases steadily as underlying severity increases. As shown in Figure 2, the normative misbehavior must occur more frequently to fall within the severe range compared with the problem indicator.

Figure 2.

Illustrative Item Response Functions. (A) Normative Misbehavior. (B) Problem Indicator

Aim III: Examine associations between the Temper Loss dimension and other emotional and behavioral problems

To test for associations of Temper Loss with emotional and behavioral problems, we examined bivariate correlations followed by a series of ordinary least squares (OLS) regressions with emotional and behavioral problems as predictors, Temper Loss as outcome, and age, gender, ethnicity, and poverty status as covariates (Table 3). All emotional and behavioral problem indicators were positively associated with Temper Loss in bivariate correlations. Aggression was most strongly correlated with Temper Loss (r = .79), followed by Activity/Impulsivity (r = .54), Anxiety (r = .31) and Depression/Withdrawal (r = .31). Regression analyses revealed that, within the externalizing domain, Temper Loss was uniquely associated with both Aggression and Activity/Impulsivity. Within the internalizing domain, Temper Loss was uniquely associated with both Anxiety and Depression/Withdrawal. However, when all problems were evaluated together in the same model, Temper Loss was uniquely associated only with Aggression and Activity/Impulsivity.

Table 3.

Association of Temper Loss dimension with clinical correlates

| Multiple regression coefficient |

SE | t | β | η2 Partial | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Externalizing domain | |||||

| Intercept | −.30 | .05 | −5.8*** | ||

| Aggression | .74 | .02 | 38.0*** | .68 | .50 |

| Activity/impulsivity | .49 | .04 | 11.6*** | .21 | .09 |

| F(8, 1435, N = 1444) = 359, p < .001, R2 = .67 | |||||

| Internalizing domain | |||||

| Intercept | −.32 | .08 | −4.2*** | ||

| Anxiety | .60 | .08 | 7.6*** | .21 | .04 |

| Depression | 1.00 | .11 | 8.9*** | .25 | .05 |

| F(8, 1439, N = 1448) = 42, p < .001, R2 = .19 | |||||

| Both domains together | |||||

| Intercept | −.33 | .05 | −6.2*** | ||

| Aggression | .73 | .02 | 36.4*** | .67 | .48 |

| Activity/impulsivity | .47 | .04 | 10.5*** | .20 | .07 |

| Anxiety | .09 | .05 | 1.7 | .03 | .00 |

| Depression | .04 | .08 | .5 | .01 | .00 |

| F(10, 1433, N = 1444) = 288, p < .001, R2 = .67 | |||||

Models control for age, gender, ethnicity/race, and poverty.

p < .05;

p < .01;

p < .001.

Discussion

Developmental psychopathology adherents have long theorized that clinical patterns can be conceptualized as deviations from normative patterns (Cicchetti & Richters, 1997). Furthermore, clinical syndromes are increasingly viewed through a dimensional lens (Hudziak, Achenbach, Althoff, & Pine, 2007). These perspectives are well-developed theoretically, but their empirical evidence base is less well developed. We tested a dimensional model of Temper Loss in preschoolers utilizing rigorous psychometric methods applied to a novel, developmentally sensitive, parent-completed questionnaire. Findings hold promise for generating empirically derived parameters for ‘when to worry,’ even during a developmental period which has long challenged nosologic systems. First, we found that temper tantrums occur occasionally in most preschoolers, but only approximately 10% of children exhibit them daily. Second, we psychometrically validated our theory that Temper Loss falls along a dimensional continuum ranging from normative misbehaviors to problem indicators. Third, we demonstrated associations between Temper Loss and other clinical problems. These correlational data are but a first glimpse, however, as they are based solely on parent report in the absence of validated indicators of clinical significance and/or impairment. One of the most common conundrums of preschool psychopathology is the murky boundary between normative misbehavior and disruptive behavior. The recent validation of developmentally sensitive diagnostic methods, which rely on observation in standardized contexts and/or parent report, provides techniques for clinical assessment within research contexts (Egger et al., 2006; Wakschlag et al., 2008). However, the absence of a standard metric for referral contributes to a double-edged sword of minimizing parental concern and underidentification versus potential overidentification and psychotropic overtreatment (Wakschlag & Danis, 2009; Zito et al., 2007). If clinically validated, our findings suggest that two key features of tantrums may be useful for screening in primary care settings.

First, consistent with previous studies, nearly all preschoolers (83.7%) tantrum sometimes, but having daily tantrums is not typical (Bhatia et al., 1990; Osterman & Bjorkqvist, 2010). Our findings suggest that this is true for younger preschoolers, for girls and boys, and for children across varying levels of contextual risk. This provides empirical evidence that inquiring about the frequency of tantrums may yield important information that can help guide clinical concern. Second, quality, as well as frequency, contributes to the severity continuum. Both normative misbehaviors and facets of anger regulation have mild, commonly occurring, as well as severe and more rarely occurring, manifestations. Severe temper loss may manifest as daily tantrums of any form or qualitatively more severe behaviors exhibited less than daily, including tantrums lasting more than 5 minutes, being aggressive during a tantrum, having a tantrum with nonparental adults, and having a tantrum ‘out of the blue.’ Prior work in both clinical (Belden et al., 2008) and community (Green et al., 2011; Osterman & Bjorkqvist, 2010) samples also suggests these features are developmentally meaningful indicators of concern.

The importance of an evidence base for determining the feasibility and clinical utility of taking developmental and sociocultural differences into account has been noted (Frick & Nigg, 2011; Moffitt et al., 2008). In the MAPS Study, we present preliminary support for consistent patterns of atypicality across sociodemographic categories. For example, although older preschoolers are less likely to tantrum than younger preschoolers, daily temper loss is not normative at any age. The same is true for girls and boys, poor and nonpoor children, and across racial/ethnic groups. Future research should include fine-grained analyses within subgroups to elucidate variations in thresholds and optimize item parameters.

Temper Loss was associated with parent-reported problems of aggression, hyperactivity, anxiety, and depression. While it is essential to extend these findings with assessments beyond parent-report, this suggests that temper regulation problems may serve as a common psychopathological substrate, as previously demonstrated with older youth (Stringaris & Goodman, 2009). The strong association between Aggression and Temper Loss may be at least partially explained by shared method variance, as both were assessed with the MAP-DB. The MAP-DB Temper Loss construct also centers solely on angry affect and behavior. Incorporation of developmentally specified expressions of a broader range of negative affect may enhance the MAP-DB Temper Loss scale’s clinical salience for mood problems. For example, Potegal and colleagues have proposed an ‘anger-distress’ model, which incorporates sadness as a tantrum feature (Green et al., 2011).

The dimensionality of temper loss processes may have important implications for clinical conceptualizations and elucidation of mechanisms (Helzer et al., 2008). Moving beyond a dichotomous characterization to a more nuanced spectrum of temper loss provides a framework for identifying emergent problems and targeting young children at-risk due to family history of psychopathology and/or environmental adversity. It also delineates a range of behaviors that might ultimately serve as intervention targets. Consistent with the NIMH Research Domain Criteria initiative (Insel et al., 2010), viewing temper dysregulation as a spectrum also holds promise for linkage to neural circuitry and genetic mechanisms in a more fine-grained manner than current categorical classifications allow.

The limitations of this work must be noted. First, these developmentally defined patterns of atypicality are merely suggestive when obtained from a single parental report. To establish clinical validity, MAP-DB Temper Loss must be linked to established measures of disruptive, mood and anxiety disorders and impairment, cross-sectionally, and longitudinally. We are currently collecting data to validate the MAP-DB against multimethod, multiinformant measures, including the PAPA, DB-DOS, teacher questionnaires, and neurocognitive measures. Second, some children with undiagnosed autism spectrum disorders may have been included in analyses, potentially inflating temper tantrum rates. Third, our findings are limited to early childhood. A basic tenet of this study is that developmental specification will enhance characterization of phenotypic heterogeneity and accuracy of identification. Testing life span continuities and incremental utility of developmentally specified dimensional models of temper loss is critical. Fourth, the recall window for Temper Loss frequency in the MAP-DB is limited to the past month to ensure that behaviors were not fleeting. Whereas DSM-IV requires 6-month duration for ODD symptoms, duration thresholds for preschoolers have not been established empirically.

Conclusion

The dimensional model of Temper Loss empirically supported here has important implications for a cross-syndromal framework of psychopathological symptoms, such as the NIMH Research Domain Criteria (RDoC; Insel et al., 2010). In particular, our dimensional model provides a well-specified description of normative and problematic forms of a clinically salient affective domain, that is, the regulation of anger. It also provides firm grounding for translation of clinical phenomena into developmentally specified terms. Although efforts are underway to delineate the boundaries of clinically significant temper dysregulation for DSM-V, these require validated methods for distinguishing psychopathology from normative variation, a challenge amplified for preschoolers (Leibenluft, 2011). The present findings provide a model of a dimensional continuum that may inform this process.

Supplementary Material

Key points.

Problems in temper modulation are core to developmental psychopathology. However, normative, atypical boundaries have not been empirically established.

We tested a developmentally specified dimensional model of Temper Loss using the Multidimensional Assessment of Preschool Disruptive Behavior (MAP-DB) in a large, diverse sample of preschoolers (n = 1,490).

Temper Loss demonstrated compelling regularity across behaviors reflecting temper tantrum features and anger regulation. Whereas 83.7% of preschoolers had tantrums over the past month, only 8.6% had daily tantrums.

A unidimensional Temper Loss scale characterized severity along a continuum from normative misbehavior to problem indicator.

Emotional and behavioral problems were associated with Temper Loss.

A developmentally specified dimensional characterization of temper loss provides a critical framework for elucidating cross-syndromal substrates of psychopathology and early identification.

Acknowledgements

Lauren Wakschlag, Margaret Briggs-Gowan, Alice Carter, and Seung Choi are supported by NIMH grants R01MH082830 and R01MH090301. Lauren Wakschlag was also supported by the Walden & Jean Young Shaw Foundation. The contributions of Patrick Tolan, Ph.D., Robert Gibbons, Ph.D., Barbara Danis, Ph.D., and Carri Hill, Ph.D. to the development of the MAPDB are gratefully acknowledged. We express heartfelt thanks to participating pediatric clinics and families from Rush University, the University of Illinois at Chicago, and the following Northwestern University Pediatric Practice Research Group practices for their participation: Healthlinc in Valparaiso, IN, Healthlinc in Michigan City, IN, and Associated Pediatricians in Valparaiso, IN. We also thank David Cella, Ph.D. for his inspiring leadership and scientific support.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement: Lauren Wakschlag, Seung Choi, Heide Hullsiek, James Burns, Kimberly McCarthy, and Ellen Leibenluft report no biomedical financial interests or potential conflicts of interest. Margaret Briggs-Gowan and Alice Carter receive royalties from the ITSEA (Infant-Toddler Social Emotional Assessment), which is a published measure.

Supporting information

Additional Supporting Information may be found in the online version of this article:

Table S1. Distribution (%) of individual MAP-DB Temper Loss items across sociodemographic subgroups a

Please note: Wiley-Blackwell are not responsible for the content or functionality of any supporting materials supplied by the authors. Any queries (other than missing material) should be directed to the corresponding author for the article.

References

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders-IV. 4th edn. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Barajas RG, Philipsen N, Brooks-Gunn J. Cognitive and emotional outcomes for children in poverty. In: Crane DR, Heaton T, editors. Handbook of families and poverty. Newbury Park, CA: Sage; 2008. pp. 311–333. [Google Scholar]

- Belden A, Thompson N, Luby J. Temper tantrums in healthy versus depressed and disruptive preschoolers: Defining tantrum behaviors associated with clinical problems. Journal of Pediatrics. 2008;152:117–122. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2007.06.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhatia MS, Dhar NK, Singhal PK, Nigam VR, Malik SC, Mullick DN. Temper tantrums. Prevalence and etiology in a non-referral outpatient setting. Clinical Pediatrics. 1990;29:311–315. doi: 10.1177/000992289002900603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Briggs-Gowan MJ, Carter AS. Applying the Infant-Toddler Social Emotional Assessment (ITSEA) and brief-ITSEA in early intervention. Infant Mental Health Journal. 2007;28:564–583. doi: 10.1002/imhj.20154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Browne MW, Cudeck R. Alternative ways of assessing model fit. In: Bollen KA, Long JS, editors. Testing structural equation models. Newbury Park, CA: Sage; 1993. pp. 136–162. [Google Scholar]

- Burke JD, Hipwell AE, Loeber R. Dimensions of oppositional defiant disorder as predictors of depression and conduct disorder in preadolescent girls. Journal of the Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2010;49:484–492. doi: 10.1097/00004583-201005000-00009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carter AS, Briggs-Gowan MJ. ITSEA: Infant-Toddler Social Emotional Assessment examiner’s manual. San Antonio, TX: Harcourt Assessment; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Cicchetti D, Richters J. Examining the conceptual and scientific underpinnings of research in developmental psychopathology. Developmental Psychopathology. 1997;9:189–191. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cole P, Michel M, Teti L. The development of emotion regulation and dysregulation: A clinical perspective. In: Fox N, editor. The development of emotion regulation: Biological and behavioral considerations. vol. 240. Chicago: University of Chicago Press; 1994. pp. 73–102. 59. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egger HL. Paper presented at the Meetings of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. Miami, Florida: 2003. Temper tantrums and preschool mental health. [Google Scholar]

- Egger HL, Erkanli A, Keeler G, Potts E, Walter B, Angold A. The test-retest reliability of the Preschool Age Psychiatric Assessment (PAPA) Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2006;45:538–549. doi: 10.1097/01.chi.0000205705.71194.b8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Einon D, Potegal M. Temper tantrums in young children. In: Potegal M, Knutson J, editors. The dynamics of aggression: Biological and social processes in dyads and groups. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum; 1994. pp. 157–194. [Google Scholar]

- Frick PJ, Nigg JT. Current issues in the diagnosis of Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder, Oppositional Defiant Disorder, and Conduct Disorder. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology. 2011;8:77–107. doi: 10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-032511-143150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodenough F. Anger in young children. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minessota Press; 1931. [Google Scholar]

- Green JA, Whitney PG, Potegal M. Screaming, yelling, whining, and crying: Categorical and intensity differences in vocal expressions of anger and sadness in children’s tantrums. Emotion. 2011;11:1124–1133. doi: 10.1037/a0024173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helzer J, Kraemer HC, Krueger RF, Wittchen HU, Sirovatka PJ, Regier DA. Dimensional approaches in diagnostic classification: Refining the research agenda for DSM-V. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Association; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Hu L, Bentler PM. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling. 1999;6:1–55. [Google Scholar]

- Hudziak JJ, Achenbach TM, Althoff RR, Pine DS. A dimensional approach to developmental psychopathology. International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research. 2007;16(Suppl 1):S16–S23. doi: 10.1002/mpr.217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Insel T, Cuthbert B, Garvey M, Heinssen R, Pine DS, Quinn K, Wang P. Research domain criteria (RDoC): Toward a new classification framework for research on mental disorders. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2010;167:748–751. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2010.09091379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leibenluft E. Severe mood dysregulation, irritability, and the diagnostic boundaries of bipolar disorder in youths. The American Journal of Psychiatry. 2011;168:129–142. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2010.10050766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moffitt TE, Arseneault L, Jaffee SR, Kim-Cohen J, Koenen KC, Odgers CL, Viding E. Research Review: DSM-V conduct disorder: research needs for an evidence base. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2008;49(1):3–33. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2007.01823.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, Muthén BO. Mplus user’s guide. 5th edn. Los Angeles: Muthén & Muthén; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Osterman K, Bjorkqvist K. A cross-sectional study of onset, cessation, frequency, and duration of children’s temper tantrums in a nonclinical sample. Psychological Reports. 2010;106:448–454. doi: 10.2466/pr0.106.2.448-454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reise SP, Waller NG. Item response theory and clinical measurement. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology. 2009;5:25–46. [Google Scholar]

- Samejima F. Estimation of latent ability using a response pattern of graded scores. Psychometrika Monograph. 1970;35:139–139. [Google Scholar]

- Stringaris A. Irritability in children and adolescents: a challenge for DSM-5. European Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2011;20:61–66. doi: 10.1007/s00787-010-0150-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stringaris A, Cohen P, Pine D, Leibenluft E. Adult outcomes of youth irritability: A 20-year prospective community-based study. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2009;166:1048–1054. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2009.08121849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stringaris A, Goodman R. Longitudinal outcome of youth oppositionality: Irritable, headstrong, and hurtful behaviors have distinctive predictions. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2009;48:404–412. doi: 10.1097/CHI.0b013e3181984f30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thissen D, Chen W-H, Bock RD. MULTILOG (version 7) [Computer software] Lincolnwood, IL: Scientific Software International; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Wakschlag L, Briggs-Gowan M, Carter A, Hill C, Danis B, Keenan K, Leventhal B. A developmental framework for distinguishing disruptive behavior from normative misbehavior in preschool children. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2007;48:976–987. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2007.01786.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wakschlag L, Briggs-Gowan M, Hill C, Danis B, Leventhal B, Cicchetti D, Carter A. Observational assessment of preschool disruptive behavior: Part II: Validity of the Disruptive Behavior Diagnostic Observation Schedule (DB-DOS) Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2008;47:632–641. doi: 10.1097/CHI.0b013e31816c5c10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wakschlag L, Danis B. Characterizing early childhood disruptive behavior: Enhancing developmental sensitivity. In: Zeanah C, editor. Handbook of infant mental health. 3rd edn. New York: Guilford; 2009. pp. 392–408. [Google Scholar]

- Wakschlag L, Briggs-Gowan M, Tolan P, Hill C, Danis B, Carter A. The Multidimensional Assessment of Preschool Disruptive Behavior (MAP-DB) Questionnaire. Unpublished measure. 2010 [Google Scholar]

- Zito JM, Safer DJ, Valluri S, Gardner JF, Korelitz JJ, Mattison DR. Psychotherapeutic medication prevalence in Medicaid-insured preschoolers. Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychopharmacology. 2007;17:195–203. doi: 10.1089/cap.2007.0006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.