Abstract

Objective To examine whether deviation from one’s ethnic group norm on body mass index (BMI) was related to psychosocial maladjustment among early adolescent girls, and whether specific ethnic groups were more vulnerable to maladjustment. Methods Hierarchical regression analyses were conducted on self- and peer-report measures from an ethnically diverse sample of sixth-grade girls (N = 2,636). Results African Americans and Latinas had a higher mean BMI than Asians and Whites. As deviation from their ethnic group BMI norm increased, girls reported greater social anxiety, depression, peer victimization, and lower self-worth, and had lower peer-reported social status. Associations were specific to girls deviating toward obesity status. Ethnic differences revealed that Asian girls deviating toward obesity status were particularly vulnerable to internalizing symptoms. Conclusions Emotional maladjustment may be more severe among overweight/obese girls whose ethnic group BMI norm is furthest away from overweight/obesity status. Implications for obesity work with ethnically diverse adolescents were discussed.

Keywords: early adolescence, ethnic differences, group norm, obesity, psychosocial adjustment, social status

In recent decades, the prevalence of child obesity has substantially increased (Hedley et al., 2004), with recent estimates showing rates have leveled off but remain high among children aged 6–19 years (18.2% meet obesity status; 33.2% overweight status; Ogden, Carroll, Kit, & Flegal, 2012). In addition to negative physical health correlates, such as Type II diabetes (Rosenbloom et al., 2000), a growing literature has linked childhood obesity to poorer emotional adjustment, including anxiety, depression, and low self-worth compared with non-overweight/obese children and adolescents (Falkner et al., 2001). Overweight/obese youth are also at high risk for lower social status, experiencing more peer rejection (Strauss & Pollack, 2003), peer victimization (Pearce, Boergers, & Prinstein, 2002), and social isolation compared with normal-weight adolescents (Falkner et al., 2001; Strauss & Pollack, 2003). Ethnic differences in obesity prevalence have also been reported, with higher obesity/overweight prevalence among African American (20.0%, 35.9%) and Latino (20.9%, 38.2%) children compared with White (15.3%, 29.3%) children (Ogden et al., 2010). However, relatively less work has examined ethnic differences in child obesity and associated psychosocial outcomes, despite the fact that ethnic disparities in obesity may contribute to different socio-emotional experiences across groups (BeLue, Francis, & Colaco, 2009). In early adolescence—when fitting in is critical to positive adjustment—considering individual body size compared with ethnic group norms may provide a better understanding of the influence of ethnicity on the relationship between child obesity and psychosocial well-being.

One explanation for the association between obesity and poor psychosocial outcomes posits that as children develop and construct their social identity, they become increasingly sensitive to the normative characteristics of their peer group (LaFontana & Cillessen, 2010). Consequently, children who are different from peers in terms of body size may elicit social rebuff, leading to feelings of alienation and low self-worth (Sentse, Scholte, Salmivalli, & Voeten, 2007). Because the transition from childhood to adolescence is marked by heightened social awareness corresponding to increased time spent with peers, early adolescence is an especially critical period for considering how deviating from group norms for body size may be related to psychosocial well-being. Furthermore, using a continuous indicator like deviation from the group body mass index (BMI) norm makes it possible to detect differences in adjustment for adolescents who appear different from the group norm even if the differences are not extreme enough to classify them into an at-risk weight category (e.g., obese).

Another critical issue that has yet to be addressed is whether membership in different ethnic groups should be considered when examining body size deviations from the group norm. According to social identity theory (Tajfel & Turner, 1986), individuals derive their self-concept from the social group(s) to which they belong, and groups derive their identity from the characteristics shared by the group members. Because ethnicity represents a salient marker of adolescent identity (Phinney & Ong, 2006), it is likely that deviations from the norm are largely based on the ethnic group one belongs to; therefore, deviation from one’s ethnic group norm may be a more valid indicator of assessment between body size and psychosocial adjustment than deviation from the overall peer group norm. A number of studies have documented significant ethnic differences in obesity prevalence, with African American and Latino youth at greater risk of obesity than White adolescents (Freedman, Khan, Serdula, Ogden, & Dietz, 2006; Ogden et al., 2010). Thus, for example, a White and an African American adolescent with the same BMI may vary widely in their deviation from their group norm. These differences in deviation may inform a growing literature indicating obese Latino and White adolescents, but not obese African Americans, are at higher risk for psychosocial maladjustment compared with non-obese adolescents (BeLue et al., 2009). Taken together, these findings suggest that the experience of obesity may be relative to the ethnic group to which children belong. The limited work examining ethnic differences, including the dearth of studies including other major ethnic groups, particularly Asian adolescents, warrants additional research in this area.

Compared with ethnic differences, gender differences in psychosocial adjustment among overweight/obese youth have been examined more frequently. Generally, there is consensus that overweight/obese females are more likely to experience social anxiety, depression, and low self-worth compared with overweight/obese males (Needham & Crosnoe, 2005). Females are also more likely than males to report higher levels of weight-related distress and dissatisfaction (Young-Hyman et al., 2006) and may be more likely to experience negative social consequences associated with overweight/obese status (cf. Tang-Péronard & Heitmann, 2008). These relationships may be explained in part by the literature demonstrating that adolescent girls are more susceptible than boys to idealized thin body images in the media, which contribute to decreases in body dissatisfaction and increases in appearance comparison (Knauss, Paxton, & Alsaker, 2007). Considering these gender differences, research on psychosocial adjustment among overweight/obese females is particularly warranted. In addition, without the use of an adiposity measure, it is difficult to determine whether boys with high BMI are characterized more by greater muscle mass rather than body fat as a result of pubertal changes in early adolescence (Rogol, Roemmich, & Clark, 2002); consequently, they may not be representative of what peers would perceive as overweight/obese. For these reasons, early adolescent girls were studied exclusively in the current study.

Given the increasing importance of adhering to the group norm, we hypothesized that as early adolescent girls’ BMI deviates from their corresponding ethnic groups’ mean BMI, they will report higher levels of emotional maladjustment and will have lower peer-reported social status. Given the social stigma associated with obesity, we expected that these associations would be significant only among those deviating toward higher BMI, or obesity status, rather than lower BMI, or underweight status. Furthermore, as a result of ethnic differences in obesity prevalence, we expected associations between BMI deviation and psychosocial indicators to vary depending on adolescents’ ethnic group. We hypothesized that as deviation from the BMI group norm increases toward obesity status, girls would experience greater emotional maladjustment and lower social status if they belonged to an ethnic group with a lower average BMI (e.g., Asian and White) compared with an ethnic group with a higher average BMI (e.g., African American and Latina). Thus, we expected Asian and White females moving toward obesity status to experience greater emotional maladjustment and lower social status compared with those in their respective ethnic groups closer to the group norm, but we did not expect this relationship to be as strong among African American and Latina girls.

Method

Participants

The current study included data from the UCLA Middle School Diversity Project, an ongoing longitudinal study of ethnic diversity and socio-emotional adjustment in urban middle schools from northern and southern California. Schools in this study were carefully selected to represent a variety of ethnic compositions, as described below. Upon Institutional Review Board approval, six middle schools in the Los Angeles area were recruited to participate as Cohort 1 in the fall of 2009, and 14 additional schools in the Los Angeles and San Francisco Bay areas were recruited to participate as Cohort 2 in the fall of 2010. Cohort 1 and Cohort 2 schools vary in sociodemographic differences by design. Schools recruited for the Cohort 1 sample were selected based on the ethnically diverse nature of their student populations (i.e., no single ethnic group comprised a majority of the population). Schools recruited for the Cohort 2 sample were selected based on the ethnic group in the majority of the student population (e.g., two majority African American schools were recruited, two majority Latino schools were recruited, etc.). Given the high degree of correlation between ethnicity and socioeconomic status (SES), the range of free/reduced price lunch eligibility (our school-level proxy for SES) across schools within each cohort differed slightly (Cohort 1: M = 43.36%, Range = 25.47–66.67%; Cohort 2: M = 54.53%, Range = 20.69–80.13%; t(18) = −1.25, p > .05). In both cohorts, schools with the lowest eligibility had a greater proportion of White/Caucasian students. In addition, Cohort 1 had a mean BMI percentile of 56.35 (SD = 30.66) and Cohort 2 had a mean BMI percentile of 60.01 (SD = 30.05; t(3567) = −3.48, p < .01). Across the 20 schools, 7,458 consent forms were distributed to sixth grade students in their homeroom classes. Of these, 6,058, or 81%, were returned, with 84% of parents granting permission for their child to participate (n = 5,075).

Participants comprised 5,075 students (52% female; M = 11.62 years, SD = 1.24). Based on student self-report, the sample was 30.9% Latino; 15.4% White/Caucasian; 12.6% East/Southeast Asian; 11.8% African American/Black. Twenty-nine percent of participants self-reported as belonging to other ethnic groups, including American Indian, Middle Eastern, Pacific Islander, South Asian, and multiethnic/biracial. Of the 5,075 participants, 1,409 (27.8%) did not report height and/or weight data and 97 (1.9%) reported inaccurate height and/or weight. For these 97 participants (53 girls), BMI was considered invalid if BMI% was identified at 0.0% (45 girls) using the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) 2000 growth charts. Also, among girls, eight BMI percentiles above 99.0% were considered invalid because their reported height was unlikely given their age, sex, and corresponding weight (heights reported under 4’0 with corresponding weights in the 80 lb. range). Multiple imputation was conducted to estimate BMI for those with missing or invalid BMI data (described in the data analysis section). The final analytic sample included 2,636 adolescent females (M = 11.59 years, SD = .48); 33.5% Latino, 15.4% White/Caucasian, 13.6% East/Southeast Asian, 13.5% Multiethnic, 11.6% African American/Black, 2.8% Pacific Islander, 2.0% South Asian, 1.9% Middle Eastern, and 1.5% other. In terms of girls’ immigration status, 34.0% of East/Southeast Asians, 14.8% of Latinos, 4.1% Whites, and 2.4% African Americans reported being first generation. The majority of African American and White females in the sample were third generation (at least 1 parent and child born in the U.S.) or beyond (76.3% and 72.9%, respectively), whereas the majority of East/Southeast Asian and Latina females in the sample were second generation (child born in the U.S. but parents born outside U.S.; 58.7% and 71.3%, respectively). All participants were proficient in English.

Procedure

In the fall of 2009 (Cohort 1) and 2010 (Cohort 2), students with signed parental consent completed a questionnaire during a single period in one of their sixth grade classes. Students recorded their answers independently as they followed instructions being read aloud by a graduate research assistant who reminded them of the confidentiality of their responses. A second researcher circulated around the classroom to help students as needed. Students were given an honorarium of $5 for completing the questionnaire.

Measures

Deviation From Group BMI Norm

Self-reported height and weight was used to measure BMI. This is an acceptable method for calculating BMI, as scores derived are generally consistent with those based on direct measurement (Brener, Mcmanus, Galuska, Lowry, & Wechsler, 2003; Field, Aneja, & Rosner, 2007; Goodman, Hinden, & Khandelwal, 2000), although underreporting of weight is a trend among obese and female adolescents (Brener et al., 2003; Field et al., 2007; Sherry, Jeffers, & Grummer-Strawn, 2007). Based on responses to questions about height (“How tall are you?” __ feet __ inches) and weight (“How much do you weigh?” __ lbs), a BMI (kg/m2), percentile was calculated for each participant using age- and gender-specific BMI percentile distributions from the CDC 2000 growth charts (Kuczmarski et al., 2000). To determine the degree to which each adolescent female deviated from her ethnic group’s BMI norm, a difference score was calculated by subtracting a participant’s ethnic and gender group mean BMI percentile (calculated separately for each school) from her own BMI percentile. Positive scores indicated greater deviation from the group norm toward obesity status (BMI ≥ 95%) and negative scores indicated greater deviation from the group norm toward underweight status (BMI < 5%).

Emotional Adjustment

Social Anxiety

Social anxiety was measured by aggregating two subscales from the Social Anxiety Scale for Children-Revised (La Greca & Lopez, 1998). The 12 items assessed fear of negative evaluation (e.g., “I worry about what others say about me”) and social avoidance (e.g., “It’s hard for me to ask others to do things with me”). Responses were rated on a 5-point scale (1 = not at all to 5 = all the time). Item scores were summed and averaged (α = .81).

Depressive Symptoms

A 10-item, adapted version of the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D; Radloff, 1977) was used to assess depressive symptoms (e.g., “I felt depressed,” “I felt sad,” “My sleep was restless”). Adolescents were asked how often they had experienced each item in the past week. A 4-point scale was used (1 = rarely or none of the time to 4 = almost all the time), and item scores were summed and averaged (α = .71).

Self-Worth

Self-worth was assessed with six items of the global self-worth subscale from the Self-Perception Profile for Children (SPPC; Harter, 1982). Each item is presented in a structured alternative format (e.g., “Some kids are happy with themselves as a person BUT Other kids are often not happy with themselves”). Participants first chose whether they were more like the kids described in the statement on the left or right side and then marked whether the chosen statement was “really true for me” or “sort of true for me.” Responses were scored on a 4-point scale, and then summed and averaged (α = .79).

Frequency of Peer Victimization

A new measure of self-reported experiences with victimization was created for this study. Participants reported on the frequency of how often they were the targets of seven types of peer victimization (e.g., “made fun of you in front of others,” “hit, kicked, or pushed you”) since the beginning of the school year. Items included incidents of verbal, relational, and physical aggression. Responses were scored on a 5-point frequency scale (1 = never and 5 = almost every day), and then summed and averaged (α = .85).

Social Status

Indicators of social status were measured by peer nomination. Students were presented with a roster containing the names of all study participants in their grade at their school, arranged by name (alphabetically by first name) and gender. Using the roster, students were instructed to select their classmates who fit the following descriptions: “Who would you like to hang out with at school?”, “Who do you not like to hang out with?”, and “Who are the coolest kids?” Students were allowed to select an unlimited number of classmates to record on their response sheets. Social reputations as liked, disliked, and cool were created based on the number of nominations received for each of the above questions. Nominations were standardized by school, ethnicity, and gender, such that participants’ scores reflect the relative number of “like,” “not like,” and “cool” nominations received by participants in the same school in same gender and ethnic groups. Standardization by ethnicity and gender controlled for potential significant associations between ethnicity/gender and peer status, irrespective of body size. A social preference score (see Coie, Dodge, & Coppotelli, 1982) was calculated by subtracting the standardized score for “not like to hang out with” nominations from the standardized score for “like to hang out with” nominations and standardizing the difference by school, ethnicity, and gender.

Statistical Analyses

Multiple Imputation

Multiple imputation (MI) procedures were conducted to estimate BMI data for girls missing height and/or weight information (n = 819; 31.2%). In this sample, Latinas (35.1%) were more likely to have missing BMI data, and Whites (16.5%) were less likely to have missing BMI data compared with all other groups (African American/Black 23.0%; East/Southeast Asian 27.0%). Based on previous recommendations (Little & Rubin, 2002), we included auxiliary variables in the MI that were consistent with our conceptual model, including age, gender, ethnicity, and psychosocial (emotional adjustment, social status) indicators, as well as BMI percentile at Wave 2 (6 months after the initial time point). Given the sample size and percent of missing data, we imputed 10 data sets based on the recommendation by Bodner (2008) using Mplus 6.1 (Muthén & Muthén, 1998–2010). Following MI, the main analysis was conducted in Mplus 6.1, which averaged results across the 10 imputed data sets.

Main Analysis

To evaluate deviation from group BMI norm, as well as ethnic differences in emotional adjustment and social status, hierarchical linear regression analysis was conducted. Each psychosocial indicator was considered a separate outcome. In the first step, a difference score representing deviation from one’s ethnic group BMI norm was included, along with four binary ethnic group variables (African American/Black vs. non-African American/Black, East/Southeast Asian vs. non-East/Southeast Asian, Latino vs. non-Latino, Caucasian/White vs. non-Caucasian/White). In the second step, the cross-product interaction term for deviation from group BMI norm and each ethnic group was entered. To minimize multicollinearity, the continuous independent variable (deviation from group BMI norm) was centered. The created interaction terms involving ethnicity and the deviation and group BMI norm were centered as well (Aiken & West, 1991). For significant interaction terms, we followed procedures outlined by Holmbeck (2002) for post-hoc probing of significant moderational effects.

Results

Descriptive Statistics

The mean BMI percentile among adolescent females was 55.85 (SD = 30.03). BMI percentiles among African Americans (M = 62.81, SD = 29.10) and Latinas (M = 62.11, SD = 29.40) were each significantly higher (p < .001) than those of Whites (M = 49.16, SD = 29.50) and East/Southeast Asians (M = 46.22, SD = 29.99). Mean BMI percentile did not significantly differ between African Americans and Latinas, and between Whites and East/Southeast Asians. Weight status classification across the sample and for each ethnic group is presented in Table I.

Table I.

Weight Status Classification of Girls by Ethnic Group

| Weight status | All girls (%) | African American/Black (%) | East/Southeast Asian (%) | Latina (%) | White/Caucasian (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Underweight (BMI < 5%) | 6.4 | 4.7 | 10.7 | 4.6 | 7.4 |

| Normal (BMI 5–84.9%) | 72.0 | 65.7 | 75.3 | 66.0 | 78.8 |

| Overweight (BMI ≥ 85%) | 21.6 | 29.7 | 14.0 | 29.4 | 13.8 |

| Obese (BMI ≥ 95%) | 8.8 | 13.6 | 4.5 | 12.6 | 4.3 |

Note. Overweight status inclusive of obese status.

Multivariate Analyses

Hierarchical linear regression analyses were conducted to assess associations between deviation from one’s ethnic group BMI norm and psychosocial outcomes, and to determine whether ethnicity moderated these associations. The four emotional adjustment outcomes (social anxiety, depression, self-worth, and self-perceived frequency of victimization) and the two social status outcomes (social preference and cool nominations) were examined in separate analyses. These findings are summarized in Table II.

Table II.

Summary of Hierarchical Regression Analyses for Psychosocial Outcomes

| Variable | Social anxiety | Depression | Self-worth | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B(SE) | β | R2(ΔR2) | B(SE) | β | R2(ΔR2) | B(SE) | β | R2(ΔR2) | |

| CI (95%) | CI (95%) | CI (95%) | |||||||

| Step 1 | .02(.01**) | .01(.00)* | .04(.01)*** | ||||||

| Deviation in BMI % | .03(.02) | .04† | .03(.02) | .03 | −.06(.02) | −.08*** | |||

| (−.01 to .07) | (−.01 to .07) | (−.10 to −.02) | |||||||

| African American/Black | −.10(.05) | −.05* | −.04(.04) | −.03 | −.01(.05) | −.00 | |||

| (−.19 to −.002) | (−.12 to .04) | (−.11 to .09) | |||||||

| East/Southeast Asian | .19(.04) | .10*** | −.01(.04) | −.16(.05) | −.08*** | ||||

| (.11 to .27) | (−.09 to .07) | −.00 | (−.26 to −.06) | ||||||

| Latino | .06(.04) | .04 | .03(.03) | .03 | −.14(.04) | −.09*** | |||

| (−.02 to .14) | (−.03 to .09) | (−.22 to −.06) | |||||||

| White/Caucasian | −.04(.04) | −.02 | −.11(.03) | .08** | .19(.04) | .10*** | |||

| (−.12 to .04) | (−.17 to −.05) | (.11 to .27) | |||||||

| Step 2 | .02(.00)** | .01(.00)** | .04(.00)*** | ||||||

| Deviation in BMI % × African American/Black | .02(.02) | .02 | −.01(.01) | −.03 | .01(.02) | .01 | |||

| (−.02 to .05) | (−.03 to .01) | −.03 to .05) | |||||||

| Deviation in BMI % × East/Southeast Asian | −.02(.02) | −.03 | −.03(.01) | −.06* | .03(.02) | .05* | |||

| (−.05 to .01) | (−.05 to −.003) | (.0006 to .06) | |||||||

| Deviation in BMI % × Latino | −.00(.02) | −.00 | .01(.02) | .01 | .00(.02) | .00 | |||

| (−.04 to .04) | (−.03 to .05) | (−.04 to .04) | |||||||

| Deviation in BMI % × White/Caucasian | .00(.02) | −.00 | −.00(.01) | −.01 | −.01(.02) | −.02 | |||

| (−.04 to .04) | (−.02 to .02) | (−.05 to .03) | |||||||

| Variable | Victimization | Cool | Social preference | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B(SE) | β | R2(ΔR2) | B(SE) | β | R2(ΔR2) | B(SE) | β | R2(ΔR2) | |

| CI (95%) | CI (95%) | CI (95%) | |||||||

| Step 1 | .00(.00) | .01(.00)* | .01(.00)† | ||||||

| Deviation in BMI % | .03(.01) | .04* | −.09(.02) | −.08*** | −.08(.02) | −.07** | |||

| (.01 to .05) | (−.13 to −.05) | (−.12 to −.04) | |||||||

| African American/Black | .04(.04) | .02 | −.01(.07) | −.00 | .01(.07) | .00 | |||

| (−.04 to .12) | (−.15 to .13) | (−.13 to .15) | |||||||

| East/Southeast Asian | −.02(.04) | −.01 | −.01(.07) | −.00 | −.01(.07) | −.00 | |||

| (−.10 to .06) | (−.15 to .13) | (−.15 to .13) | |||||||

| Latino | −.04(.03) | −.03 | .00(.05) | .00 | .01(.05) | .00 | |||

| (−.10 to .02) | (−.10 to .10) | (−.09 to .11) | |||||||

| White/Caucasian | −.03(.04) | −.02 | .02(.06) | .01 | −.01(.06) | −.00 | |||

| (−.11 to .05) | (−.10 to .12) | (−.13 to .12) | |||||||

| Step 2 | .01(.01)* | .01(.00)* | .01(.00)* | ||||||

| Deviation in BMI % × African American/Black | .03(.02) | .02 | −.02(.03) | −.02 | −.04(.02) | −.04† | |||

| (−.01 to .07) | (−.06 to .02) | (−.08 to −.001) | |||||||

| Deviation in BMI % × East/Southeast Asian | −.02(.02) | .03 | −.01(.02) | −.01 | .00(.02) | .00 | |||

| (−.06 to .02) | (−.05 to −.00) | (−.04 to .04) | |||||||

| Deviation in BMI % × Latino | −.01(.02) | .03 | .01(.03) | .01 | −.04(.03) | −.04 | |||

| (−.05 to −.00) | (−.05 to .07) | (−.10 to .02) | |||||||

| Deviation in BMI % × White/Caucasian | −.01(.02) | .03 | −.02(.03) | −.02 | .04(.03) | .03 | |||

| (−.05 to −.00) | (−.08 to .04) | (−.02 to .10) | |||||||

†p < .10; *p < .05; **p < .01; ***p < .001.

For each regression analysis, deviation from one’s ethnic group BMI percentile norm and ethnicity (African American, East/Southeast Asian, Latino, White) were entered in Step 1. The results for emotional adjustment indicated that as deviation from one’s ethnic group BMI norm increased, girls reported lower self-worth (β = −.08, p < .001) and increased frequency of victimization (β = .04, p < .05). Deviation from the norm was not significantly related to social anxiety (β = .04, p > .05) and depression (β = .03, p > .05). In terms of social status indicators, greater deviation from the group BMI norm was significantly associated with lower social preference (β = −.07, p < .01) and fewer nominations as cool (β = −.08, p < .001).

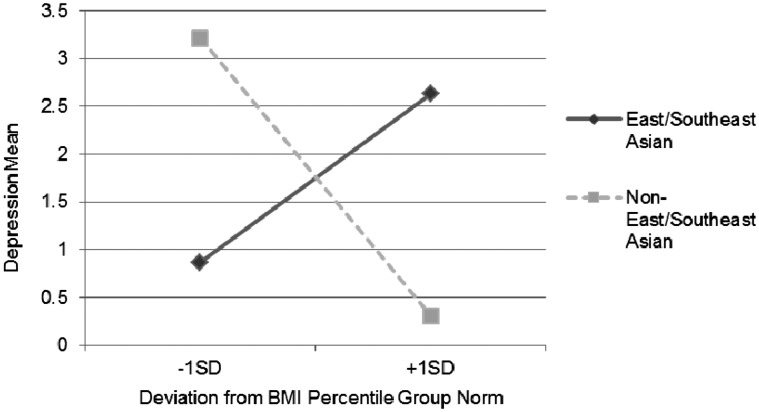

Step 2 considered interactions between deviation from the group BMI norm and ethnic group. A significant interaction between deviation from group BMI norm and East/Southeast Asian adolescents was found for two of the four emotional adjustment outcomes: self-worth (β = .05, p < .05) and depression (β = −.06, p < .05). Following procedures described by Aiken and West (1991) and Holmbeck (2002) for probing significant interactions, East/Southeast Asian and Non-East/Southeast Asian were treated as conditional moderator variables, and new interactions that incorporated these conditional variables were created. We then ran two post-hoc regressions, each of which involved simultaneous entry of deviation from group BMI norm, one of the conditional moderators (e.g., East/Southeast Asian), and the consequential interaction variable (e.g., deviation from BMI norm × East/Southeast Asian; Holmbeck, 2002). From these analyses, we derived unstandardized betas (slopes) and regression equations for East/Southeast Asian and Non-East/Southeast Asian adolescents1.

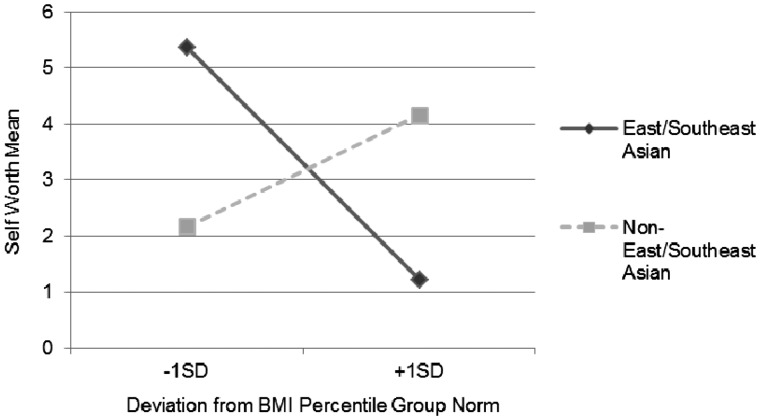

In terms of self-worth, the slope for East/Southeast Asian girls was significantly different from zero (b = −.07, t(2549) = −4.30, p < .001). As shown in Figure 1, East/Southeast Asian early adolescent girls with greater positive deviation from the group BMI norm (toward obesity status) reported lower levels of self-worth than those closer to the group BMI norm or deviating negatively away from the group norm (toward underweight status). The slope for non-East/Southeast Asian girls was not significant (b = .04, t(2549) = .82, p > .05). For depression, the slope for East/Southeast Asian girls was significantly different (b = .03, t(2550) = 2.44, p < .05), indicating greater positive deviation from the group BMI norm was associated with higher levels of depression compared with East/Southeast Asian girls closer to their group BMI norm or deviating negatively from the group norm (see Figure 2). The slope for Non-East/Southeast Asian girls was not significant (b = −.05, t(2550) = −1.60, p > .05).

Figure 1.

The association between deviation in BMI percentile from the group norm and self-worth among East/Southeast Asian and Non-East/Southeast Asian girls.

Figure 2.

The association between deviation in BMI percentile from the group norm and depression among East/Southeast Asian and Non-East/Southeast Asian girls.

Because interactions identified positive deviation from the group BMI norm (toward obesity status) as problematic, an ancillary analysis was conducted to assess whether associations between deviation from the group BMI norm and psychosocial maladjustment was specific to those moving toward obesity status (positively deviating from the group mean) rather than moving toward underweight status (negatively deviating from the group mean). Hierarchical regression analyses were repeated separately for girls above and below the group BMI norm. Deviating positively from the group BMI norm (toward obesity status) was significantly associated with all six indicators of psychosocial maladjustment; deviating negatively from the group BMI norm (toward underweight status) was not associated with any psychosocial outcome.2 No ethnic differences were found except for social preference among girls deviating positively from the group BMI norm. White females moving toward obesity status experienced lower levels of social preference from peers compared with those closer to the group BMI norm (b = −.21, t(1406) = −3.20, p < .01). The slope for non-White females was not significant (b = .04, t(1406) = .34, p > .05).

Discussion

As children transition to adolescence, they are faced with the challenge of fitting in with their peers. For early adolescent girls, in particular, poor psychosocial adjustment may be related to not fitting BMI norms during this vulnerable developmental period. Previous research examining BMI and psychosocial adjustment has not considered the influence of ethnicity on deviation from BMI norms, and whether membership in certain ethnic groups may increase or decrease vulnerability to poor psychosocial adjustment. The current study sought to increase understanding of associations between BMI and psychosocial adjustment among early adolescent girls by considering the influence of ethnic group BMI norms and evaluating associations across ethnicity. The findings demonstrated that across all emotional adjustment and social status indicators, greater deviation from one’s ethnic group BMI norm, specifically toward obesity status, was associated with higher levels of emotional maladjustment and lower social status. In addition, East/Southeast Asian adolescent females deviating from their group norm toward obesity appear to be more vulnerable than other ethnic groups in terms of emotional maladjustment, and White adolescent females deviating from their group norm toward obesity appear more vulnerable toward in terms of social status.

The association between BMI deviation and psychosocial maladjustment was specific to those deviating positively toward obesity status. The finding that White girls moving away from their group BMI norm toward obesity status were less likely to receive favorable peer nominations compared with those closer to the group BMI norm is in line with past literature showing White girls may be more susceptible to social stigmatization than girls from other ethnic groups (Strauss & Pollack, 2003). In addition, East/Southeast Asian girls who deviated positively toward obesity status from their group BMI norm reported lower levels of self-worth and higher levels of depression compared with East/Southeast Asian girls closer to their group BMI norm or those deviating negatively toward underweight status. These results lend support to our hypothesis that overweight/obese status among girls from ethnic groups with lower BMI norms may be associated with poorer psychosocial adjustment.

Because of the limited availability of research on obesity among Asian children and adolescents, our findings indicating poor emotional adjustment among East/Southeast girls deviating toward obesity status warrant consideration of the contextual influences they are likely to experience. East/Southeast Asian girls in our sample had the lowest group BMI percentile, significantly lower than African American girls and Latinas. Consequently, a BMI percentile that would be the norm or below the norm for African American, Latina, or even White adolescent females (e.g., 50th percentile) would be considered a positive deviation from the East/Southeast Asian group norm; thus, the threshold for not fitting in with one’s BMI group norm is lower among East/Southeast Asians than other major ethnic groups. Also, because of their lower BMI norm, East/Southeast Asian girls meeting overweight or obesity status experience the largest deviation from the norm compared with other ethnic groups. The combination of lowest threshold and greatest magnitude of deviating from the group BMI norm may explain why East/Southeast Asian girls deviating toward obesity status report higher levels of emotional maladjustment. Previous studies on Asian adolescents and young adults show that Asian females have higher body image dissatisfaction, a greater fear of fat, and they choose an ideal BMI lower than their actual and perceived BMI at rates higher or on par with White females (Haudek, Rorty, & Henker, 1999; Sanders & Heiss, 1998). It is unclear whether these preferences are a result of following Asian values of modesty, making it less likely to have positive body image (Lau, Lum, Chronister, & Forrest, 2006), or of internalizing Westernized ideal images emphasizing thinness (Evans & McConnell, 2003). More research on ethnic identity and acculturation processes is needed to shed light on why East/Southeast girls deviating toward obesity status are vulnerable to emotional maladjustment.

Several limitations of the present study need be considered. First, self-reported height and weight resulted in missing data. Although multiple imputation allowed us to estimate BMI data for those with missing or errors in data, and previous studies have reported minor differences in reliability between self-reported and measured BMI among children and adolescents (Brener et al., 2003; Field et al., 2007; Goodman et al., 2000), prior studies have shown that obese adolescents and females are more likely to underreport weight (Brener et al., 2003; Field et al., 2007; Sherry et al., 2007). This may explain why our self-reported obesity prevalence was lower than national norms, as early adolescent girls are likely to experience heightened self-consciousness about reporting weight when surrounded by peers. Given the finding that White girls deviating toward obesity status receive less social preference from peers, we suspect that White overweight/obese girls were especially self-conscious about reporting weight. Another limitation is that the cross-sectional nature of the study limits conclusions about the effect of deviation from group BMI norm on psychosocial outcomes; longitudinal studies are needed to better test hypotheses about cause–effect relations. Also, we did not study ethnic identity and acculturation status of participants, which may provide insight into the constructs examined here. Finally, although our new measure assessing common forms of peer victimization is promising, further psychometric testing on reliability, validity, and generalizability across multi-ethnic samples is warranted.

Despite these limitations, this study has important implications for future research on overweight/obese youth. Compared with perceived social status based on self-report, peer nominations may more accurately reflect social status consequences of BMI. Future research should include peer-reported social status indicators in order to more fully understand the social consequences of obesity throughout adolescence. In addition, future research would benefit from using a continuous indicator of BMI deviation to examine the relationship between overweight/obese status and psychosocial adjustment for all youth, not just those whose BMI falls into an extreme weight category. Based on the findings reported here, an important next step is to investigate the psychological processes, such as mediating or moderating mechanisms, that might explain the relationship between deviation from group BMI norm and psychosocial difficulties. For example, are overweight/obese youth who belong to an ethnic group with a lower average BMI more likely to engage in self-blame when they deviate from the BMI norm for their group (see Graham, Bellmore, Nishina, & Juvonen, 2009)? Or, how do acculturation processes interact with overweight/obesity to influence psychosocial adjustment among first- and second-generation immigrants?.

Of particular importance in future research is the inclusion of Asian females when identifying youth at risk for maladjustment due to obesity. Epidemiological studies should increase efforts to include East/Southeast Asian children and adolescents in obesity research, as little work has included this population. For instance, it is difficult to compare the weight status classification of the current study with the well-established National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) prevalence rates because the NHANES includes only a small percentage of Asians categorized in an “other” group not suitable for any ethnic subgroup analysis (Ogden et al., 2010). As noted in our sample weight status classification, East/Southeast Asian girls’ lower rates of obesity and higher rates of underweight status may have influenced our overall weight status rates, as obesity and overweight status were somewhat lower than previously reported (Ogden et al., 2010, 2012). Incorporating East/Southeast Asians in epidemiological work will allow for necessary comparison across studies. Furthermore, as Asian Americans have recently become the fastest growing ethnic group in the U.S. and the majority immigrant population, it will be increasingly necessary for health educators and mental health professionals to be aware of the cultural context, such as acculturation processes, that may potentially explain why Asian Americans moving toward obesity status are more vulnerable to emotional maladjustment.

The findings of this study also have important implications for intervention efforts with youth who suffer the stigma of obesity or are at risk for such stigma, particularly among East/Southeast Asian and White females. Health professionals and school personnel involved in adolescents’ well-being need to recognize that even East/Southeast Asians and White females who do not meet overweight or obesity status may still be at risk for poor emotional and social adjustment if they physically appear to be above their ethnic group BMI norm. Irrespective of ethnicity, practitioners and clinicians might also do well to move away from intervention approaches that assign full responsibility to individuals and instead help them recognize factors in the environment (both within and outside their control) contributing to their overweight/obese status (see Budd & Hayman, 2008). Such an approach may be critical in reducing the negative emotional outcomes associated with obesity, especially for youth who are prone to self-blaming tendencies.

Funding

Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (1RO1HD059882); the National Science Foundation (0921306); the National Institute on Drug Abuse (5T32DA007272).

Conflicts of interest: None declared.

Footnotes

The study name of “UCLA Middle School Diversity Project” was omitted from the original article. The author regrets the error.

1Prior to multiple imputation of the BMI data, analyses using only participants with available BMI data were conducted, indicating similar results.

2A table displaying the results of the ancillary analysis is available from the first author upon request.

References

- Aiken L S, West S G. Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions. Newbury Park, CA: Sage; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- BeLue R, Francis L A, Colaco B. Mental health problems and overweight in a nationally representative sample of adolescents: Effects of race and ethnicity. Pediatrics. 2009;123:697–702. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-0687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bodner T E. What improves with increased missing data imputations? Structural Equation Modeling. 2008;15:651–675. [Google Scholar]

- Brener N D, Mcmanus T, Galuska D A, Lowry R, Wechsler H. Reliability and validity of self-reported height and weight among high school students. Journal of Adolescence Health. 2003;32:281–287. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(02)00708-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Budd G M, Hayman L L. Addressing the childhood obesity crisis: A call to action. MCN, The American Journal of Maternal/Child Nursing. 2008;33:111–118. doi: 10.1097/01.NMC.0000313419.51495.ce. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coie J D, Dodge K A, Coppotelli H. Dimensions and types of social status: A cross-age perspective. Developmental Psychology. 1982;18:557–570. [Google Scholar]

- Evans P C, McConnell A R. Do racial minorities respond in the same way to mainstream beauty standards? Social comparison processes in Asian, Black, and White women. Self and Identity. 2003;2:153–167. [Google Scholar]

- Falkner N H, Neumark-Sztainer D, Story M, Jeffrey R W, Beuhring T, Resnick M D. Social, educational, and psychological correlates of weight status in adolescents. Obesity Research. 2001;9:32–42. doi: 10.1038/oby.2001.5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Field A E, Aneja P, Rosner B. The validity of self-reported weight change among adolescents and young adults. Obesity. 2007;15:2357–2364. doi: 10.1038/oby.2007.279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freedman D S, Khan L K, Serdula M K, Ogden C L, Dietz W H. Racial and ethnic differences in secular trends for childhood BMI, weight, and height. Obesity. 2006;14:301–308. doi: 10.1038/oby.2006.39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodman E, Hinden B R, Khandewal S. Accuracy of teen and parental reports of obesity and body mass index. Pediatrics. 2000;106:52–58. doi: 10.1542/peds.106.1.52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham S, Bellmore A, Nishina A, Juvonen J. “It must be me”: Ethnic diversity and attributions for peer victimization in middle school. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2009;38:487–499. doi: 10.1007/s10964-008-9386-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harter S. The perceived competence scale for children. Child Development. 1982;53:87–97. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haudek C, Rorty M, Henker B. The role of ethnicity and parental bonding in the eating and weight concerns of Asian-American and Caucasian college women. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 1999;25:425–433. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1098-108x(199905)25:4<425::aid-eat7>3.0.co;2-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hedley A A, Ogden C L, Johnson C L, Carroll M D, Curtin L R, Flegal K M. Prevalence of overweight and obesity among US children, adolescents, and adults, 1999-2002. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2004;291:2847–2850. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.23.2847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmbeck G N. Post-hoc probing of significant moderational and mediational effects in studies of pediatric populations. Journal of Pediatric Psychology. 2002;27:87–96. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/27.1.87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knauss C, Paxton S J, Alsaker F D. Relationships among body dissatisfaction, internalization of the media body ideal and perceived pressure from media in adolescent girls and boys. Body Image. 2007;4:353–360. doi: 10.1016/j.bodyim.2007.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuczmarski R J, Ogden C L, Grummer-Strawn L M, Flegal K M, Guo S S, Wei R, Mei Z, Curtin L R, Roche A F, Johnson C L. 2000. CDC Growth Charts: United States advance data from vital and health statistics. No. 314. National Center for Health Statistics. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LaFontana K M, Cillessen A H N. Developmental changes in the priority of perceived status in childhood and adolescence. Social Development. 2010;19:130–147. [Google Scholar]

- La Greca A M, Lopez N. Social anxiety among adolescents: Linkages with peer relations and friendships. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1998;26:83–94. doi: 10.1023/a:1022684520514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lau A S M, Lum S K, Chronister K M, Forrest L. Asian American college women's body image: A pilot study. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology. 2006;12:259–274. doi: 10.1037/1099-9809.12.2.259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Little R J A, Rubin D B. Statistical analyses with missing data. 2nd ed. New York: Wiley; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Muthén L K, Muthén B O. Mplus user’s guide. 6th ed. Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén; 1998-2010. [Google Scholar]

- Needham B L, Crosnoe R. Overweight status and depressive symptoms during adolescence. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2005;36:48–55. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2003.12.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogden C L, Carroll M D, Curtin L R, Lamb M M, Flegal K M. Prevalence of high body mass index in US children and adolescents, 2007-2008. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2010;303:242–249. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogden C L, Carroll M D, Kit B K, Flegal K M. Prevalence of obesity in the United States, 2009-2010) National Center for Health Statistics Data Brief. 2012;82:1–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearce M J, Boergers J, Prinstein M J. Adolescent obesity, overt and relational peer victimization, and romantic relationships. Obesity Research. 2002;10:386–393. doi: 10.1038/oby.2002.53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phinney J S, Ong A D. Conceptualization and measurement of ethnic identity: Current status and future directions. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 2006;54:271–281. [Google Scholar]

- Radloff L S. The CES-D Scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement. 1977;1:385–401. [Google Scholar]

- Rogol A D, Roemmich J N, Clark P A. Growth at puberty. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2002;31:192–200. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(02)00485-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenbloom A, Arslanian S, Brink S, Conschafter K, Jones K L, Klingensmith G, Neufeld N, White N. Type 2 diabetes in children and adolescents. Pediatrics. 2000;105:671–680. [Google Scholar]

- Sanders N M, Heiss C J. Eating attitudes and body image of Asian and Caucasian college women. Eating Disorders: The Journal of Treatment & Prevention. 1998;6:15–27. [Google Scholar]

- Sentse M, Scholte R, Salmivalli C, Voeten M. Person-group dissimilarity in involvement in bullying and its relation with social status. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2007;35:1009–1019. doi: 10.1007/s10802-007-9150-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherry B, Jefferds M E, Grummer-Strawn L M. Accuracy of adolescent self-report of height and weight in assessing overweight status: A literature review. Archives of Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicine. 2007;161:1154–1161. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.161.12.1154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strauss R S, Pollack H A. Social marginalization of overweight children. Archives of Pediatric Adolescent Medicine. 2003;157:746–752. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.157.8.746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tajfel H, Turner J C. The social identity theory of inter-group behavior. In: Worchel S, Austin L W, editors. Psychology of intergroup relations. Chicago: Nelson-Hall; 1986. pp. 33–48. [Google Scholar]

- Tang-Péronard J L, Heitmann B L. Stigmatization of obese children and adolescents, the importance of gender. Obesity Reviews. 2008;9:522–534. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2008.00509.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young-Hyman D, Tanofsky-Kraff M, Yanovski S Z, Keil M, Cohen M L, Peyrot M, Yanovski J A. Psychological status and weight-related distress in overweight or at-risk-for-overweight children. Obesity. 2006;14:2249–2258. doi: 10.1038/oby.2006.264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]