Abstract

Halitosis is formed by volatile molecules which are caused because of pathological or nonpathological reasons and it originates from an oral or a non-oral source. It is very common in general population and nearly more than 50% of the general population have halitosis. Although halitosis has multifactorial origins, the source of 90% cases is oral cavity such as poor oral hygiene, periodontal disease, tongue coat, food impaction, unclean dentures, faulty restorations, oral carcinomas, and throat infections. Halitosis affects a person's daily life negatively, most of people who complain about halitosis refer to the clinic for treatment but in some of the people who can suffer from halitosis, there is no measurable halitosis. There are several methods to determine halitosis. Halitosis can be treated if its etiology can be detected rightly. The most important issue for treatment of halitosis is detection etiology or determination its source by detailed clinical examination. Management may include simple measures such as scaling and root planning, instructions for oral hygiene, tongue cleaning, and mouth rinsing. The aim of this review was to describe the etiological factors, prevalence data, diagnosis, and the therapeutic mechanical and chemical approaches related to halitosis.

Keywords: Diagnosis, etiology, halitosis, humans, prevention and control

INTRODUCTION

Human breath is composed of highly complex substances with numerous variable odors which can generate unpleasant situations like halitosis. Halitosis is a latin word which derived from halitus (breathed air) and the osis (pathologic alteration),[1] and it is used to describe any disagreeable bad or unpleasant odor emanating from the mouth air and breath. Foetor oris, oral malodor, mouth odor, bad breath, and bad mouth odor are the other terms which are used to describe and characterize the halitosis.[2–4] This undesirable condition is a common complaint for both genders and for all age groups. It creates social and psychological disadvantages for individuals, and these situations affect individual's relation with other people.[5] In present review we describe the etiological factors, prevalence data,etiology, diagnosis, and the therapeutic mechanical and chemical approaches related to halitosis.

PREVELENCE

Halitosis is very common in general population and nearly more than 50% of the general population have halitosis.[6] In a Swedish study of 840 men, halitosis assessment was only present in around 2% of the population.[7] However, halitosis prevalence in a China study which involved more than 2500 participants was assessed above 27.5%.[8] Also in the literature, the prevalence of halitosis reported as ranging from 5% to 75% of tested children.[9,10] Origin of halitosis in 90% of the patient is oral cavity; 9% of patient source of halitosis is non-oral reasons such as respiratory system, gastrointestinal system, or urinary system. In 1% of patients, the cause of the halitosis is diets or drugs.[11,12]

ETIOLOGY OF HALITOSIS

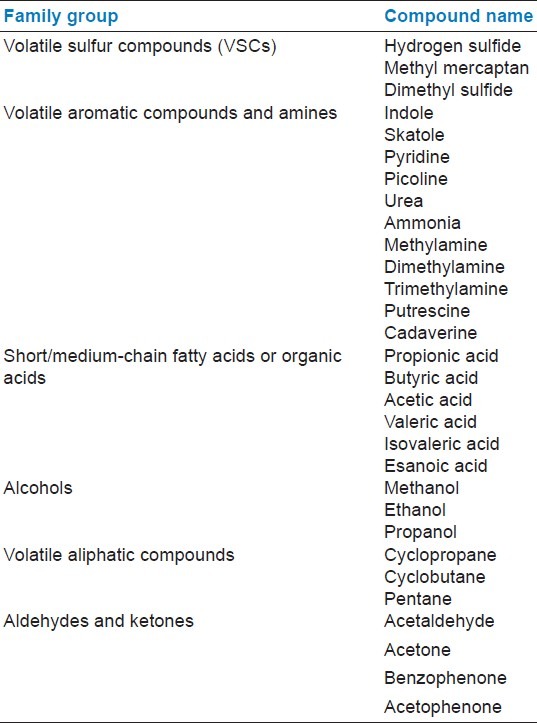

Halitosis is formed by volatile molecules which are caused because of pathological or nonpathological reasons, and it originates from an oral or a non-oral source. These volatile compounds are sulfur compounds, aromatic compounds, nitrogen-containing compounds, amines, short-chain fatty acids, alcohols or phenyl compounds, aliphatic compounds, and ketones [Table 1].[13–17]

Table 1.

Odoriferous components cause halitosis[17]

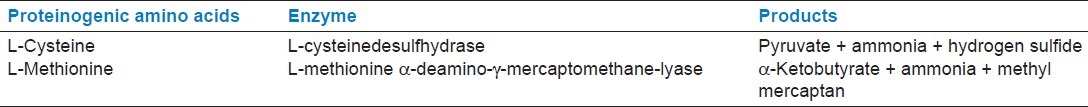

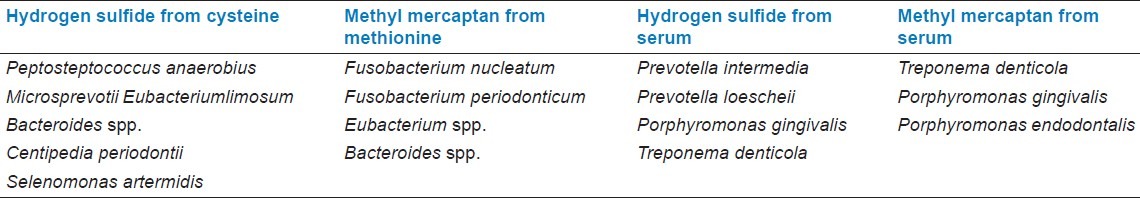

Volatile sulfur compounds (VSCs) are mainly responsible for intra-oral halitosis. These compounds are mainly hydrogen sulfide and methyl mercaptan. They produce bacteria by enzymatic reactions of sulfur-containing amino acids which are L-cysteine and L-methionine [Table 2].[18] In addition, some of the bacteria produce hydrogen sulfide and methyl mercaptan from serum. The bacteria which are the most active VSC producers are shown [Table 3].[19]

Table 2.

Enzymatic way of the hydrogen sulfide and methyl mercaptan

Table 3.

Bacteria which is active producers of volatile sulfur compounds in vitro (adapted from Persson et al.[19])

The other VSC is dimethyl sulfide which mainly responsible for extra-oral or blood-borne halitosis,[20] but it can be a contributor to oral malodor. Ketones such as acetone, benzophenone, and acetophenone are present in both alveolar (lung) and mouth air; indole and dimethyl selenide are present in alveolar air.[16,21] These compounds are also factors for Halitosis occurrence and it may be simply classified their origins into three categories; oral causes, non-oral causes, and the other causes.

Halitosis originates from oral cavity

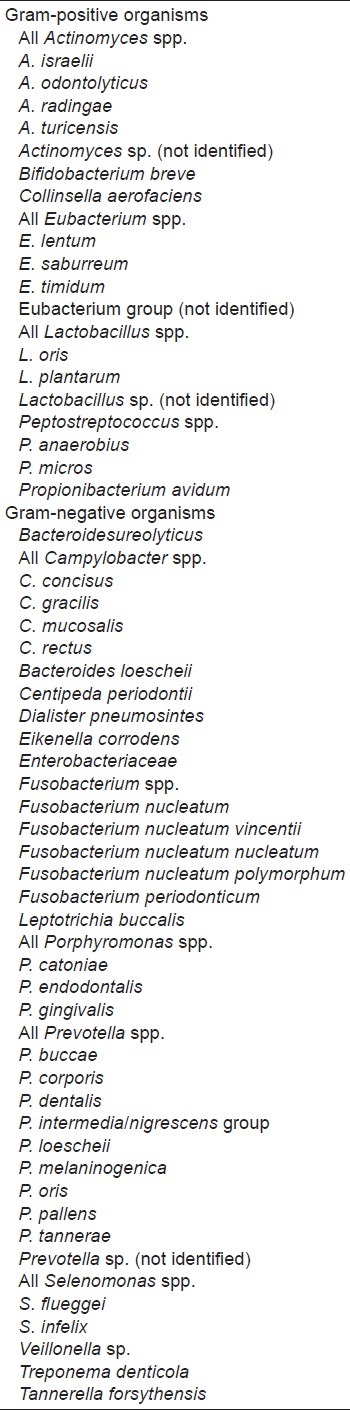

Although halitosis has multifactorial origins, the source of 90% cases is oral cavity. In oral cavity, temperatures may be reached up to 37°C (and changed between 34 and 37°C). During exhaling[22] also humidity may be reached up to 96% (and changed between 91% and 96%) in oral exhalations.[23] These conditions may provide a suitable environment for bacterial growth. The number of bacterial species, which are found in oral cavity, are over 500,[8] and most of them are capable to produce odorous compounds which can cause halitosis. In these conditions, poor oral hygiene plays a key factor for multiplication of halitosis causative bacteria and causes an increase in halitosis. These bacteria include especially Gr-negative species and proteolytic obligate anaerobes [Table 4],[24–27] and they mainly retained in tongue coating and periodontal pockets.[5,28] Among healthy individuals, with no history of halitosis and no periodontal diseases, some show halitosis because of retention of bacteria on the tongue surface.[29] These bacteria degrade organic substrates (such as glucose, mucins, peptides, and proteins present in saliva, crevicular fluid, oral soft tissues, and retained debris) and produce odorous compounds.[5,30,31]

Table 4.

Bacteria which contribute halitosis

By the poor oral hygiene, food debris and dental bacterial plaque accumulate on the teeth and tongue, and cause caries and periodontal diseases like gingivitis and periodontitis. The inflammation of gingival and periodontal tissues creates typical sources for oral malodors[32,33] and plaque-related periodontal disease can increase the severity of halitosis. However, the other forms of periodontal disease, especially acute and aggressive forms such as acute necrotizing ulcerative gingivitis, pericoronitis, Vincent's disease or aggressive forms of periodontitis, can increase unpleasant breath odor.[32] The type of gingival enlargement which is dependent on inflammation or drugs (such as phenytoin, cyclosporine or calcium channel blockers) may increase the risk of bad odor.[34] The severity of halitosis is affected from periodontal conditions, also periodontal conditions are affected by halitosis. The previous studies showed a relationship between oral halitosis and periodontal disease. Periodontal diseases may be developed by the volatile sulfur-containing compound transition to periodontal tissues.[35–37] However, it is still not well understood what is the relationship between periodontal health and oral malodors.[38–40]

Besides periodontal conditions, untreated deep carious lesions also create the retention area for food debris and dental bacterial plaque and may cause halitosis. Another important factor in halitosis is the flow of saliva. The intensity of sulfur compounds is increased because of salivary flow reduction or xerostomia.[41] Saliva functions as a buffering or a cleaning agent and keeps bacteria at a manageable level in the mouth.[42] Reduction of the salivary flow has negative effects on self-cleaning of the mouth and inadequate cleaning of the mouth causes halitosis.[43–47] Reduction of Salivary flow may be affected from many reasons such as medications (e.g., antidepressants, antipsychotics, diuretic, and antihypertensive), salivary gland diseases (e.g., diabetes, Sjorgen's syndrome), chemotherapy, or radiotherapy.[48–51]

Other factors that contribute to halitosis are endodontic, surgical, and pathologic factors such as exposed tooth pulps and non-vital tooth with fistula draining into the mouth, oral cavity pathologies, oral cancer and ulcerations, extractions/healing wounds or prosthetics or dentition factors such as orthodontic fixed appliances, keeping at night or not regularly cleaning dentures, restorative crowns which are not well adapted, noncleaning the bridge body, and interdental food impaction. All these factors [Table 5] cause food or plaque retention area, raising bacterial amount, tissue breakdown, putrefaction of amino acids, and decreasing of saliva flow. All these conditions result in the release of volatile compounds and cause halitosis.[52–56]

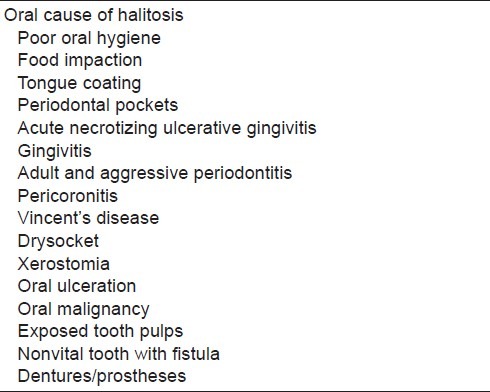

Table 5.

Reasons of halitosis which is originated from oral cavity

Halitosis originates from non-oral sources

Nearly 8% of the halitosis cases caused from an extraoral source. This type halitosis has many sources, but it is rarely seen. Respiratory system problems, gastrointestinal disease, hepatic disease, hematological or endocrine system disorders and metabolic conditions can all be the causes of halitosis.

Respiratory system problems can be divided into upper and lower respiratory tract problems. They are sinusitis, antral malignancy, cleft palate, foreign bodies in the nose or lung, nasal malignancy, subphrenic abscess, nasal sepsis, tonsilloliths, tonsillitis, pharyngeal malignancy, lung infections, bronchitis, and bronchiectasis lung malignancy.[45,57–59] Bacterial activity in this pathology causes halitosis which leads to putrefaction of the tissues or causes tissue necrosis and ulcerations and production of malodorous gases, which are expired causing halitosis.[53,55]

Gastrointestinal diseases cause halitosis. Pyloric stenosis, duodenal obstruction, aorto-enteric anastomosis, pharyngeal pouches, zenker's diverticulum, hiatal hernia cause food retention. Reflux esophagitis, achalasia, steatorrhea, or other malabsorption syndromes may cause excessive flatulence or Helicobacter pylori infection causes gastric ulcers[53,60] and VSC levels increase in oral breath. Levels of VCS's in oral breath may be higher in patients with erosive than nonerosive oesophagogastro-duodenal mucosal disease although VSC levels are not influenced by the degree of mucosal damage.[27,61]

Also, hepatic or hematological diseases which are hepatic failure (foetorhepaticus) and leukemia's, renal failure (usually end-stage renal failure), endocrine system disorders which are diabetic ketoacidosis or menstruation (menstrual breath), metabolic disorder which are trimethylaminuria and hypermethioninemia may cause halitosis [Table 6].

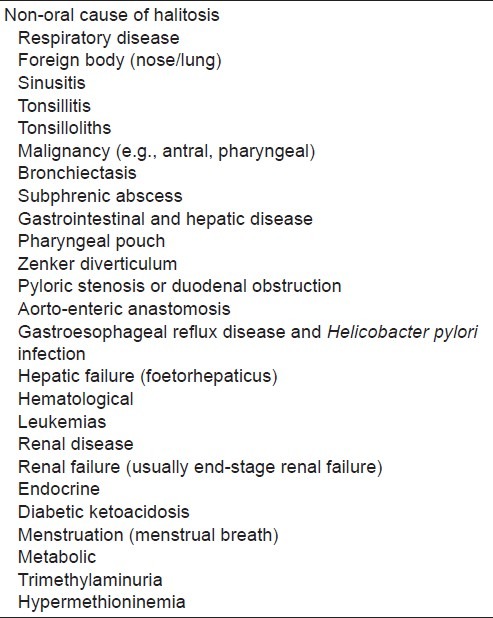

Table 6.

Non-oral cause of halitosis

Other causes of halitosis

Dietary products such as garlic, onions, spiced foods cause transient unpleasant odor or halitosis. Therewithal drugs such as alcohol, tobacco, betel, solvent abuse, chloral hydrate, nitrites and nitrates, dimethyl sulfoxide, disulphiram, somecytotoxics, phenothiazines, amphetamines, suplatast tosilate, and paraldehyde may create the same effect[62,63] [Table 7].

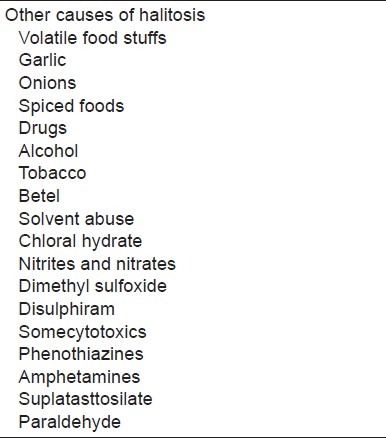

Table 7.

Other causes of halitosis

ASSESSMENT OF HALITOSIS

Halitosis affects a person's daily life negatively, most of people who complain about halitosis refer to the clinic for treatment but in some of the people who can suffer from halitosis, there is no measurable halitosis. Assessment methods of halitosis ensure discrimination of pseudo-halitosis and halitophobia. For these reasons, diagnosis of the halitosis, and assessment of its severity (conditions that patients have, is it genuine halitosis or pseudo-halitosis or halitophobia) are very important. Therefore, the diagnostic way and tools were developed. Organoleptic measurement, gas chromatography, sulfide monitoring, the BANA test, and chemical sensors have most commonly used than the other methods such as quantifying β-galactosidase activity, salivary incubation test, ammonia monitoring, or ninhydrin method.

Organoleptic measurement

The oldest way for unpleasant odor detection is by smelling with the nose. Measurement of unpleasant odors by smelling the exhaled air of the mouth and nose is called organoleptic measurement. It is the simple way for the detection of halitosis.

The measurement method is the organoleptic test; the patient takes breathe deeply by inspiring the air by nostrils and holding awhile, then expiring by the mouth directly or via a pipette, while the examiner sniffs the odor at a distance of 20 cm (the purpose of using a pipette is to lessen the intensity of expiring air) and the severity of odor is classified into various scales, such as a 0- to 5-point scale (0: no odor, 1: barely noticeable, 2: slight but clearly noticeable, 3: moderate, 4: strong, and 5: extremely strong)[45,64,65] or more widely point scale from 0 to10 point.[66]

This measurement is considered to be the gold standard for measuring and assessing bad breath[67] because of no-cost, and being practical and simple. However, it has some difficulties. It may be difficult to calibrate the practitioner and to gain the correct result; in clinical practice, the patient should avoid from eating odiferous foods for 48 h before the assessment and that both the patient and the examiner should refrain from drinking coffee, tea or juice, smoking and using scented cosmetics before the assessment.[45] Also the other problem is the way of measurement, it is unlikeable situations for the examiner because of smelling unpleasant odor and inconvenient conditions for the patient.[14] To lessen unpleasant situations instead of expiring air to examiners, the patient can breathe the air inside the bag a while, then the examiner sniff this odor from the bag and classify its severity. By this way the unpleasant side of organoleptic measurement becomes a more acceptable one.

Gas chromatography

Measurement with the gas chromatography method is considered to be highly objective, reproducible, and reliable.[68] Using gas chromatography we can measure VSCs. It separates and analyzes compounds that can be vaporized without decomposition; samples are collected from saliva, tongue coating, or expired breath. In this method, measurements are performed and equipped with a flame photometric detector or by producing mass spectra. The concentration of each VSC (ng/10 mL mouth air) was determined based on a standard of hydrogen sulfide and methyl mercaptan gas prepared with a permeater.[69]

In the gas chromatography method, the patient close the mouth and hold air 30 s, then mouth air (10 mL) is aspirated using a gas-tight syringe. After collections of samples, it is injected into the gas chromatograph column at 70°C. The results are precise and reliable, but this method takes a long time to run. Moreover, it is expensive and not used commonly in chairside, and requires a skilled operator.[6,69,70] Mostly, the results of the gas chromatography method show high correlation to organoleptic measurements but gas chromatography has high sensitivity and it can detect low concentration molecules. Therefore, sometimes we may see low correlation between gas chromatography and organoleptic measurements.[71,72]

Sulfide monitoring

Gas chromatography has high accuracy and sensitivity, but the application method in chairside is difficult and expensive. In order to avoid these disadvantages, a new portable device which is a sulfide monitor was developed to measure VSCs.

In this method before taking measurement, patients should close the mouth and refrain from talking food for 5 min prior to measurement, then a disposable tube of the sulfide monitor is inserted into patient's mouth to collect mouth air. Meanwhile, the patient is breathing through the nose and the disposable tube is connected to the monitor. Sulfur-containing compounds in the breath can generate an electro-chemical reaction. This reaction related directly with levels of volatile sulfur-containing compounds.[73–75]

The sensitivity and specificity of the sulfide monitor is less than the gas chromatography but correlations of measurements are highly significant. On the other hand, the sulfide monitor and organoleptic measurements show low correlation because of volatile compounds such as alcohols, phenyl compounds, alkenes, ketones, polyamines. Short-chain fatty acids can be detected by organoleptic measurements, but cannot be detected by the sulfide monitor so the correlations between measurements may be inconsistent.[13,74,76–79]

Chemical sensors

Because of difficulties of gas chromatography and less sensitivity of sulfide monitors, a more sensitive and easy device was made. Chemical sensors have an integrated probe to measure sulfur compounds from periodontal pockets and on the tongue surface. The working principle of chemical sensors is similar to sulfide monitors. Through the sulfide-sensing probe, sulfide compounds generate an electrochemical voltage and this voltage is measured by an electronic unit. The measurement is shown on device's screen as a digital score.[35,80,81]

Using the new chemical sensors, ammonia and methyl mercaptan compounds can be measured from breath air and some new types of sensors measure each volatile sulfur-containing compounds separately. The sensitivity is similar to gas chromatography and results of the measures are highly close to organoleptic scores so chemical sensors are called the electronic nose.[74,82–85]

BANA test

The BANA test is practical for chair-side usage. It is a test strip which composed of benzoyl-DL-arginine-a-naphthylamide and detects short-chain fatty acids and proteolytic obligate gram-negative anaerobes, which hydrolyze the synthetic trypsin substrate and cause halitosis. It detects especially Treponema denticola, P. gingivalis, and T. forsythensis that associated with periodontal disease. By using the BANA test, we can detect not only halitosis, but also periodontal risk assessment.[13,64,86–88]

To detect halitosis, the tongue is wiped with a cotton swab. For periodontal risk assessment, the subgingival plaque is obtained with a curette. To evaluate, the samples are placed on the BANA test strip, which is then inserted into a slot on a small toaster-sized incubator. The incubator automatically heats the sample to 55° for 5 min. If T. denticola, P. gingivalis, or B. forsythus are present, the test strip turns blue or the bluer. Deepening of the blue color shows existence of the higher the concentration and the greater the number of organisms.

The close relationships are found between the BANA test and organoleptic measurements, but the relationship between the BANA test and sulfur monitor measurements are poor. Performing multiple-regression analysis with organoleptic measurements and the BANA score as the dependent variable, both peak VSC levels and BANA scores factored into the regression, yielding highly significant associations.[88,89] This result may be caused by BANA-positive microorganisms which contribute halitosis via non-sulfur odorants, such as cadaverine.[13]

The BANA test results demonstrate a significant positive correlation with the increasing pocket depth.[90–92] Periodontal conditions can be assessed by this way, but periodontal conditions can be changed by BANA-negative microorganisms or the percentage of BANA-positive microorganisms may be below the detection limit of the BANA test. Comparing the sensitivity of the BANA test and of ELISA the 9% rate of false-positive results was found.[93,94] The BANA test results reflect periodontal disease activity which may cause halitosis by bleeding gums.

Quantifying β-galactosidase activity

Deglycosylation is the removed link of glycosyl groups from glycoproteins. Deglycosylation of glycoproteins are initial step in oral malodor production.[95] By deglycosylation of glycoproteins, proteolytic bacteria degrade proteins which are especially salivary glycoproteins and cause halitosis. Proteolysis of glycoprotein depends on the initial removal of the carbohydrate side-chains which are O- and N-linked carbohydrates. β-Galactosidase is one of the important enzymes which are responsible for the removal of both O- and N-linked carbohydrate side-chains.[96,97]

β-Galactosidase activity can be easily determined by the use of chromogenic substrates absorbed onto a chromatography paper disc.[74,95,98] In order to measure β-galactosidase activity, saliva was taken in a paper disc and discoloring of the paper disc changes based on β-galactosidase activity and these changes are recorded; no color: 0, faint blue color: 1, moderate to dark blue color: 2.[95] Sterer et al. found a positive correlation between organoleptic scores and β-galactosidase.[99]

Salivary incubation test

The salivary incubation is one of the assessment methods to measure halitosis indirectly. First time, Marc Quirynen et al. carried out a study to evaluate salivary incubation and halitosis. To measure halitosis with the salivary incubation test, saliva was collected in a glass tube and then incubating the tube at 37°C in an anaerobic chamber under an atmosphere of 80% nitrogen, 10% carbon dioxide, and 10% hydrogen for 3-6 h. After incubation, an examiner evaluates the odor. Although this method has some similarities with the organoleptic measurements, it has some advantages over them. The most important advantage is that the salivary incubation test has much less influenced by external parameters such as smoking, drinking coffee, eating garlic, onion, spicy food, and scented cosmetics. However in organoleptic measurements, external parameters have negative effects on the result so the patient and examiner should avoid some odiferous food and drink before 48 h. The other advantages are unpleasant conditions of these measurements compared to organoleptic methods. The results of the salivary incubation test are shown a strong correlation with the organoleptic measurement.[79] If the hardness of the incubation process does not be counted, the salivary incubation test could be one of the valuable tests for halitosis measurements.

Ammonia monitoring

Besides VSCs, ammonia is another important factor in halitosis. Sulfur compounds can be detected by a portable sulfide monitor, but unfortunately ammonia cannot be measured using this method. Ammonia is the major basic gas in a variety of important sample matrixes, for example, the ambient atmosphere, indoor air, and human breath. Comparatively, breath contains high levels of ammonia; it is 1 ppmv in the breath of a healthy individual or may be higher in individuals with renal failure.[100]

To perform measuring halitosis, a newly portable monitor has been developed. This monitor detects ammonia quantity which is producing by oral bacteria. At least 2 h before measurements, the patients should refrain from eating and drinking activity. Then patients use special mouth rinse for 30 s and close the mouth for 5 min. This rinse include urea solution and the bacteria produce ammonia from urea. To measure the concentration of ammonia a disposable mouth piece which is part of the device is placed inside a patient's mouth. This disposable part connected to an ammonia gas detector which contained a pump that drew 50 mL of air through an tube and the concentration of ammonia is noted directly from the scale on the detector tube.[15]

There is no correlation between the organoleptic score and the ammonia level measured with ammonia monitoring, but measurements of the ammonia level with ammonia monitoring show significant correlation with the total level of VSCs measured with gas chromatography.[15]

Ninhydrin method

Gases which are components of halitosis were produced from the breakdown of peptides and glycopeptides by bacterial putrefaction in the oral cavity. During this process, peptides are hydrolyzed to amino acids which further are metabolized to amines or polyamines. These molecules cannot measured by sulfide monitoring. Hence, the ninhydrin method was used for examination of amino acids and low-molecular-weight amines.

Levels of low-molecular-weight amines may give information for halitosis caused from bacterial putrefaction of low-molecular-weight amines. The ninhydrin method is simple, rapid, and inexpensive. This method is a kind of colorimetric reaction. The collected saliva is mixed with isopropanol and centrifuged. The supernatant was diluted with isopropanol, buffer solution (pH 5), and ninhydrin reagent. The mixture was refluxed in a water bath for 30 min, cooled to 21 8°C, and diluted with isopropanol. Light absorbance readings were determined using a spectrometer. The results of ninhydrin methods show a significant correlation with organoleptic scores and sulfide monitor measurements.[101]

Impact of daily life

People interact with each other every day, and halitosis has a negative effect on a person's social life. The person who has halitosis may not be aware of this situation[102] because this person may have developed tolerance or olfactory disturbance. Due to this cause, the patient generally cannot identify his/her halitosis and it is identified by his/her partner, family member, or friends. This condition causes a distressing effect on persons who have halitosis and so the affected person may avoid socializing.

Self-care products

Halitosis interferes with normal social interactions. For these reasons, self-care products are used by halitosis patients for preventing unpleasant odor. However, by these products direct treatment of halitosis is not possible; these products such as chewing gum and mints, toothpastes, mouth rinses, and sprays decrease the odor and attempt to mask halitosis with pleasant fragrances. The use of chewing gum may decrease halitosis, especially through increasing the salivary secretion.[103] Mouth rinses containing chlorine dioxide and zinc salts have a substantial effect on masking halitosis, not allowing the volatilization of the unpleasant odor.[103,104] Especially dietary caused halitosis such as onion, garlic, or cigarette can be masked by these approaches. These approaches should be only used as a temporarily solution to relieve and improve the satisfaction of the patient. Professional treatment of real halitosis has crucial severity.

Professional treatment

Halitosis can be treated if its etiology can be detected properly. Therefore, the most important issue for treatment of halitosis is detecting of etiology or determining of its source by detailed clinical examination. Although most of the cases are caused from oral cavity, sometimes other etiologies can contribute oral halitosis. If it is not detected of the etiology accurately, the treatment can be unsuccessful therefore investigation and adequate diagnosis are crucial.

In the event of oral cavity caused by halitosis, reduction of the bacterial load is essential. Appropriate periodontal management is the first step.[105] Necrotizing ulcerative gingivitis, gingivitis, adult and aggressive periodontitis or periodontal pockets can increase the bacterial load so periodontal health has significant importance in controlling the amount of halitosis caused by bacteria. Initial periodontal treatment includes scaling and root planning which may alleviate the depth of the periodontal pockets and severity of gingival inflammation and it eliminates halitosis causing bacteria.[106] During periodontal therapy, usage of antiseptic mouth wash relieves reduction of the bacterial load. Chlorhexidine can be used as a valuable antiseptic agent, but long-term uses of chlorhexidine can cause staining of teeth and mucosal surfaces.[107,108]

Good oral hygiene instruction is another important issue for oral caused halitosis. Proper brush, dental floss, and inter-dental brush usage are very important. However, sometimes even if the periodontal health is perfect, tongue coating can be an important source of halitosis. The tongue dorsum can be a shelter for these bacteria. If a patient has geographic or fissure tongue, the coating will be more. Due to these reasons, cleaning of tongue dorsum by brushing, tongue scraper or tongue cleaner is important. One of the studies showed the importance of tongue cleaning; reduction of VSC levels was found with the toothbrush 33%, with the tongue scraper 40%, and with the tongue cleaner 42%.[109]

Existing and necessary restorative conditions of a patient must be reviewed. Unsuitable prosthetics and conservative restorations, such as causing food impactions, uncleaning area or food retention, create a reservoir area for bacteria. Replacement or renewing of old restorations with proper restoration provides prevention of these reservoir areas. Also existing of the nontreated cavity of decayed teeth, nonvital tooth with fistula or exposed tooth pulps may create a reservoir area for bacteria, so treatments of these teeth with proper restoration are important.

The other conditions cause halitosis such as xerostomia, pericoronitis, oral ulceration, or malignancy which must be diagnosed and treated well. Mostly, xerostomia may be an oversight because of superficial clinical examination. This condition leads to patients deprived from protective and mechanical washing effects of saliva. The reasons of xerostomia must be examined in detail. If xerostomia caused by head and neck radio therapy or salivary glands pathology, the artificial saliva products must be suggest to the patients.

Medical conditions or history can be illuminating information about the cause of halitosis. If halitosis originate from nonoral causes such as respiratory, gastrointestinal and hepatic, renal, endocrine or hematological disease, consultation should be done with the specialist. If the actual disease is not properly diagnosed and treated, the effect of halitosis will affect a person's social life and becomes bothersome. Accordingly duties of a dentist in extra-oral cause halitosis are aware of patient about source of halitosis and sending him/her to the specialist.

As mentioned above, detailed clinical examination on halitosis is crucial. Sometimes people can think have halitosis in spite of they have no measurable halitosis. This condition is called a halitophobia and this condition can be mono symptomatic delusion (“delusional halitosis”) or manifestation of olfactory reference syndrome.[110] Management of halitophobia may be more complex than management of real halitosis. Halitophobia persons avoid socializing and even avoiding talking with people; therefore, treatment of halitophobia is very important. Prior to treating people who have halitophobia, it must be proven that he/she has no measurable halitosis by measuring devices. If persons are obsessed with the idea of having bad breath, consultation with a hyua psychologist is required.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared

REFERENCES

- 1.Hine KH. Halitosis. JADA. 1957;55:37–46. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.1957.0147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sanz M, Roldan S, Herrera D. Fundamentals of breath malodour. The journal of contemporary dental practice. 2001;2:1–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cortelli JR, Barbosa MD, Westphal MA. Halitosis: A review of associated factors and therapeutic approach. Brazilian oral research. 2008;22:44–54. doi: 10.1590/s1806-83242008000500007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bogdasarian RS. Halitosis. Otolaryngologic clinics of North America. 1986;19:111–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tonzetich J. Production and origin of oral malodor: A review of mechanisms and methods of analysis. Journal of periodontology. 1977;48:13–20. doi: 10.1902/jop.1977.48.1.13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nachnani S. Oral malodor: Causes, assessment, and treatment. (26-28, 30-21;).Compend Contin Educ Dent. 2011;32:22–24. quiz 32, 34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Soder B, Johansson B, Soder PO. The relation between foetor ex ore, oral hygiene and periodontal disease. Swedish dental journal. 2000;24:73–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Miyazaki H, Sakao S, Katoh Y, Takehara T. Correlation between volatile sulphur compounds and certain oral health measurements in the general population. Journal of periodontology. 1995;66:679–84. doi: 10.1902/jop.1995.66.8.679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kharbanda OP, Sidhu SS, Sundaram K, Shukla DK. Oral habits in school going children of Delhi: A prevalence study. Journal of the Indian Society of Pedodontics and Preventive Dentistry. 2003;21:120–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Polanco C, Saldña A, Yañez E, Araújo R. Respiración bucal. Ortodoncia. (9 ed) :especial 5–11. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Scully C, Porter S, Greenman J. What to do about halitosis. BMJ. 1994;308:217–18. doi: 10.1136/bmj.308.6923.217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kasap E, Zeybel M, Yüceyar H. Halitosis. Güncel Gastroenteroloji 2009. 2009;13:72–6. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Goldberg S, Kozlovsky A, Gordon D, Gelernter I, Sintov A, Rosenberg M. Cadaverine as a putative component of oral malodor. Journal of dental research. 1994;73:1168–72. doi: 10.1177/00220345940730060701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Loesche WJ, Kazor C. Microbiology and treatment of halitosis. Periodontology 2000. 2002;28:256–79. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0757.2002.280111.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Amano A, Yoshida Y, Oho T, Koga T. Monitoring ammonia to assess halitosis. Oral surgery, oral medicine, oral pathology, oral radiology, and endodontics. 2002 Dec;94:692–6. doi: 10.1067/moe.2002.126911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.van den Velde S, Quirynen M, van Hee P, van Steenberghe D. Halitosis associated volatiles in breath of healthy subjects. Journal of chromatography. B, Analytical technologies in the biomedical and life sciences. 2007;853:54–61. doi: 10.1016/j.jchromb.2007.02.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Campisi G, Musciotto A, Di Fede O, Di Marco V, Craxi A. Halitosis: Could it be more than mere bad breath? Internal and emergency medicine. 2011;6:315–9. doi: 10.1007/s11739-010-0492-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nakano Y, Yoshimura M, Koga T. Correlation between oral malodor and periodontal bacteria. Microbes and infection / Institut Pasteur. 2002;4:679–83. doi: 10.1016/s1286-4579(02)01586-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Persson S, Edlund MB, Claesson R, Carlsson J. The formation of hydrogen sulfide and methyl mercaptan by oral bacteria. Oral microbiology and immunology. 1990;5:195–201. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-302x.1990.tb00645.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tangerman A, Winkel EG. Intra- and extra-oral halitosis: Finding of a new form of extra-oral blood-borne halitosis caused by dimethyl sulphide. Journal of clinical periodontology. 2007;34:748–55. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051X.2007.01116.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Whittle CL, Fakharzadeh S, Eades J, Preti G. Human Breath Odors and Their Use in Diagnosis. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 2007;1098:252–66. doi: 10.1196/annals.1384.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nodelman V, Ben-Jebria A, Ultman JS. Fast-responding thermionic chlorine analyzer for respiratory applications. Review of Scientific Instruments. 1998;69:3978–83. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zehentbauer G, Krick T, Reineccius GA. Use of humidified air in optimizing APCI-MS response in breath analysis. Journal of agricultural and food chemistry. 2000;48:5389–95. doi: 10.1021/jf000464g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tyrrell KL, Citron DM, Warren YA, Nachnani S, Goldstein EJ. Anaerobic bacteria cultured from the tongue dorsum of subjects with oral malodor. Anaerobe. 2003;9:243–46. doi: 10.1016/S1075-9964(03)00109-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Morita M, Wang H-L. Association between oral malodor and adult periodontitis: A review. Journal of Clinical Periodontology. 2001;28:813–19. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-051x.2001.028009813.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Awano S, Gohara K, Kurihara E, Ansai T, Takehara T. The relationship between the presence of periodontopathogenic bacteria in saliva and halitosis. International dental journal. 2002;52:212–6. doi: 10.1002/j.1875-595x.2002.tb00927.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Porter SR. Diet and halitosis. Current opinion in clinical nutrition and metabolic care. 2011;14:463–68. doi: 10.1097/MCO.0b013e328348c054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yaegaki K, Sanada K. Biochemical and clinical factors influencing oral malodor in periodontal patients. Journal of periodontology. 1992;63:783–9. doi: 10.1902/jop.1992.63.9.783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Waler SM. On the transformation of sulfur-containing amino acids and peptides to volatile sulfur compounds (VSC) in the human mouth. European journal of oral sciences. 1997;105:534–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0722.1997.tb00241.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.McNamara TF, Alexander JF, Lee M. The role of microorganisms in the production of oral malodor. Oral surgery, oral medicine, and oral pathology. 1972;34:41–8. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(72)90271-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Persson S, Claesson R, Carlsson J. The capacity of subgingival microbiotas to produce volatile sulfur compounds in human serum. Oral microbiology and immunology. 1989;4:169–72. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-302x.1989.tb00246.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Davies A, Epstein JD. Oral complications of cancer and its management. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2010. pp. 230–240. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Takeuchi H, Machigashira M, Yamashita D, et al. The association of periodontal disease with oral malodour in a Japanese population. Oral diseases. 2010;16:702–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-0825.2010.01685.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gurbuz T, Tan H. Oral health status in epileptic children. Pediatrics international: Official journal of the Japan Pediatric Society. 2010;52:279–83. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-200X.2009.02965.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Morita M, Wang HL. Relationship of sulcular sulfide level to severity of periodontal disease and BANA test. Journal of periodontology. 2001;72:74–8. doi: 10.1902/jop.2001.72.1.74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Morita M, Wang HL. Relationship between sulcular sulfide level and oral malodor in subjects with periodontal disease. Journal of periodontology. 2001;72:79–84. doi: 10.1902/jop.2001.72.1.79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ratcliff PA, Johnson PW. The relationship between oral malodor, gingivitis, and periodontitis. A review. Journal of periodontology. 1999;70:485–9. doi: 10.1902/jop.1999.70.5.485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bosy A, Kulkarni GV, Rosenberg M, McCulloch CA. Relationship of oral malodor to periodontitis: Evidence of independence in discrete subpopulations. Journal of periodontology. 1994;65:37–46. doi: 10.1902/jop.1994.65.1.37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Stamou E, Kozlovsky A, Rosenberg M. Association between oral malodour and periodontal disease-related parameters in a population of 71 Israelis. Oral diseases. 2005;11:72–74. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-0825.2005.01097.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rosenberg M. Bad breath and periodontal disease: How related are they? Journal of clinical periodontology. 2006;33:29–30. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051X.2005.00874.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Koshimune S, Awano S, Gohara K, Kurihara E, Ansai T, Takehara T. Low salivary flow and volatile sulfur compounds in mouth air. Oral Surgery, Oral Medicine, Oral Pathology, Oral Radiology, and Endodontology. 2003;96:38–41. doi: 10.1016/s1079-2104(03)00162-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Nachnani S. The effects of oral rinses on halitosis. Journal of the California Dental Association. 1997;25:145–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Debaty B, Rompen E. [Origin and treatment of bad breath] Revue medicale de Liege. 2002;57:324–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Eli I, Koriat H, Baht R, Rosenberg M. Self-perception of breath odor: Role of body image and psychopathologic traits. Perceptual and motor skills. 2000;91:1193–201. doi: 10.2466/pms.2000.91.3f.1193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yaegaki K, Coil JM. Examination, classification, and treatment of halitosis; clinical perspectives. J Can Dent Assoc. 2000 May;66:257–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Motta LJ, Bachiega JC, Guedes CC, Laranja LT, Bussadori SK. Association between halitosis and mouth breathing in children. Clinics. 2011;66:939–42. doi: 10.1590/S1807-59322011000600003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Alamoudi N, Farsi N, Faris J, Masoud I, Merdad K, Meisha D. Salivary characteristics of children and its relation to oral microorganism and lip mucosa dryness.The Journal of clinical pediatric dentistry. Spring. 2004;28:239–48. doi: 10.17796/jcpd.28.3.h24774507006l550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kleinberg I, Wolff MS, Codipilly DM. Role of saliva in oral dryness, oral feel and oral malodour. International dental journal. 2002;52:236–40. doi: 10.1002/j.1875-595x.2002.tb00932.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Koshimune S, Awano S, Gohara K, Kurihara E, Ansai T, Takehara T. Low salivary flow and volatile sulfur compounds in mouth air. Oral surgery, oral medicine, oral pathology, oral radiology, and endodontics. 2003;96:38–41. doi: 10.1016/s1079-2104(03)00162-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Fox PC. Differentiation of dry mouth etiology. Advances in dental research. 1996;10:13–16. doi: 10.1177/08959374960100010101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wiener RC, Wu B, Crout R, et al. Hyposalivation and xerostomia in dentate older adults. J Am Dent Assoc. 2010;141:279–84. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.2010.0161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Babacan H, Sokucu O, Marakoglu I, Ozdemir H, Nalcaci R. Effect of fixed appliances on oral malodor. American journal of orthodontics and dentofacial orthopedics: Official publication of the American Association of Orthodontists, its constituent societies, and the American Board of Orthodontics. 2011;139:351–5. doi: 10.1016/j.ajodo.2009.03.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Steenberghe Dv. Breath malodor: A step by step approach. Copenhagen; London: Quintessence; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Delanghe G, Ghyselen J, Bollen C, van Steenberghe D, Vandekerckhove BN, Feenstra L. An inventory of patients’ response to treatment at a multidisciplinary breath odor clinic. Quintessence Int. 1999;30:307–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Dal Rio AC, Nicola EM, Teixeira AR. Halitosis--an assessment protocol proposal. Brazilian journal of otorhinolaryngology. 2007;73:835–42. doi: 10.1016/S1808-8694(15)31180-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Bornstein MM, Stocker BL, Seemann R, Burgin WB, Lussi A. Prevalence of halitosis in young male adults: A study in swiss army recruits comparing self-reported and clinical data. Journal of periodontology. 2009;80:24–31. doi: 10.1902/jop.2009.080310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Outhouse TL, Al-Alawi R, Fedorowicz Z, Keenan JV. Tongue scraping for treating halitosis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006:CD005519. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD005519.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Porter SR, Scully C. Oral malodour (halitosis) BMJ. 2006;333:632–5. doi: 10.1136/bmj.38954.631968.AE. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Rio AC, Franchi-Teixeira AR, Nicola EM. Relationship between the presence of tonsilloliths and halitosis in patients with chronic caseous tonsillitis. British dental journal. 2008;204:E4. doi: 10.1038/bdj.2007.1106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Gorkem SB, Yikilmaz A, Coskun A, Kucukaydin M. A pediatric case of Zenker diverticulum: Imaging findings. Diagn Interv Radiol. 2009;15:207–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Moshkowitz M, Horowitz N, Leshno M, Halpern Z. Halitosis and gastroesophageal reflux disease: A possible association. Oral diseases. 2007;13:581–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-0825.2006.01341.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Cicek Y, Orbak R, Tezel A, Orbak Z, Erciyas K. Effect of tongue brushing on oral malodor in adolescents. Pediatrics international: Official journal of the Japan Pediatric Society. 2003;45:719–23. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-200x.2003.01804.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Lu DP. Halitosis: An etiologic classification, a treatment approach, and prevention. Oral surgery, oral medicine, and oral pathology. 1982;54:521–6. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(82)90190-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.De Boever EH, De Uzeda M, Loesche WJ. Relationship between volatile sulfur compounds, BANA-hydrolyzing bacteria and gingival health in patients with and without complaints of oral malodor. The Journal of clinical dentistry. 1994;4:114–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Rosenberg M, Gelernter I, Barki M, Bar-Ness R. Day-long reduction of oral malodor by a two-phase oil:water mouthrinse as compared to chlorhexidine and placebo rinses. Journal of periodontology. 1992;63:39–43. doi: 10.1902/jop.1992.63.1.39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Pitts G, Pianotti R, Feary TW, McGuiness J, Masurat T. The in vivo effects of an antiseptic mouthwash on odor-producing microorganisms. Journal of dental research. 1981;60:1891–6. doi: 10.1177/00220345810600111101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Nalcaci R, Sonmez IS. Evaluation of oral malodor in children. Oral surgery, oral medicine, oral pathology, oral radiology, and endodontics. 2008;106:384–8. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2008.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Murata T, Yamaga T, Iida T, Miyazaki H, Yaegaki K. Classification and examination of halitosis. International dental journal. 2002;52:181–6. doi: 10.1002/j.1875-595x.2002.tb00921.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Suzuki N, Yoneda M, Naito T, Iwamoto T, Hirofuji T. Relationship between halitosis and psychologic status. Oral surgery, oral medicine, oral pathology, oral radiology, and endodontics. 2008;106:542–7. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2008.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Oral malodor. J Am Dent Assoc. 2003;134:209–14. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.2003.0135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Scully C, Greenman J. Halitosis (breath odor) Periodontology 2000. 2008;48:66–75. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0757.2008.00266.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Sopapornamorn P, Ueno M, Vachirarojpisan T, Shinada K, Kawaguchi Y. Association between oral malodor and measurements obtained using a new sulfide monitor. Journal of dentistry. 2006;34:770–4. doi: 10.1016/j.jdent.2006.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Rosenberg M, Kulkarni GV, Bosy A, McCulloch CA. Reproducibility and sensitivity of oral malodor measurements with a portable sulphide monitor. Journal of dental research. 1991;70:1436–40. doi: 10.1177/00220345910700110801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.van den Broek AM, Feenstra L, de Baat C. A review of the current literature on aetiology and measurement methods of halitosis. Journal of dentistry. 2007;35:627–35. doi: 10.1016/j.jdent.2007.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Kozlovsky A, Goldberg S, Natour I, Rogatky-Gat A, Gelernter I, Rosenberg M. Efficacy of a 2-phase oil: Water mouthrinse in controlling oral malodor, gingivitis, and plaque. Journal of periodontology. 1996;67:577–82. doi: 10.1902/jop.1996.67.6.577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Greenstein RB, Goldberg S, Marku-Cohen S, Sterer N, Rosenberg M. Reduction of oral malodor by oxidizing lozenges. Journal of periodontology. 1997;68:1176–81. doi: 10.1902/jop.1997.68.12.1176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Furne J, Majerus G, Lenton P, Springfield J, Levitt DG, Levitt MD. Comparison of volatile sulfur compound concentrations measured with a sulfide detector vs.gas chromatography. Journal of dental research. 2002;81:140–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Phillips M, Cataneo RN, Greenberg J, Munawar M, Nachnani S, Samtani S. Pilot study of a breath test for volatile organic compounds associated with oral malodor: Evidence for the role of oxidative stress. Oral diseases. 2005;11:32–34. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-0825.2005.01085.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Quirynen M, Zhao H, Avontroodt P, et al. A salivary incubation test for evaluation of oral malodor: A pilot study. Journal of periodontology. 2003;74:937–44. doi: 10.1902/jop.2003.74.7.937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Morita M, Musinski DL, Wang HL. Assessment of newly developed tongue sulfide probe for detecting oral malodor. Journal of clinical periodontology. 2001;28:494–6. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-051x.2001.028005494.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Loesche WJ, Lopatin DE, Giordano J, Alcoforado G, Hujoel P. Comparison of the benzoyl-DL-arginine-naphthylamide (BANA) test, DNA probes, and immunological reagents for ability to detect anaerobic periodontal infections due to Porphyromonas gingivalis, Treponema denticola, and Bacteroides forsythus. Journal of clinical microbiology. 1992;30:427–33. doi: 10.1128/jcm.30.2.427-433.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Tanaka M, Anguri H, Nonaka A, et al. Clinical assessment of oral malodor by the electronic nose system. Journal of dental research. 2004;83:317–21. doi: 10.1177/154405910408300409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Nonaka A, Tanaka M, Anguri H, Nagata H, Kita J, Shizukuishi S. Clinical assessment of oral malodor intensity expressed as absolute value using an electronic nose. Oral diseases. 2005;11:35–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-0825.2005.01086.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Minamide T, Mitsubayashi K, Jaffrezic-Renault N, Hibi K, Endo H, Saito H. Bioelectronic detector with monoamine oxidase for halitosis monitoring. The Analyst. 2005;130:1490–4. doi: 10.1039/b506748k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Toda K, Li J, Dasgupta PK. Measurement of ammonia in human breath with a liquid-film conductivity sensor. Analytical chemistry. 2006;78:7284–91. doi: 10.1021/ac060965m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Loesche WJ, Giordano J, Hujoel PP. The utility of the BANA test for monitoring anaerobic infections due to spirochetes (Treponema denticola) in periodontal disease. Journal of dental research. 1990;69:1696–702. doi: 10.1177/00220345900690101301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Laughon BE, Syed SA, Loesche WJ. API ZYM system for identification of Bacteroides spp., Capnocytophaga spp., and spirochetes of oral origin. Journal of clinical microbiology. 1982;15:97–102. doi: 10.1128/jcm.15.1.97-102.1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Tanner AC, Strzempko MN, Belsky CA, McKinley GA. API ZYM and API An-Ident reactions of fastidious oral gram-negative species. Journal of clinical microbiology. 1985;22:333–5. doi: 10.1128/jcm.22.3.333-335.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Kozlovsky A, Gordon D, Gelernter I, Loesche WJ, Rosenberg M. Correlation between the BANA test and oral malodor parameters. Journal of dental research. 1994;73:1036–42. doi: 10.1177/00220345940730050401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Schmidt EF, Bretz WA, Hutchinson RA, Loesche WJ. Correlation of the hydrolysis of benzoyl-arginine naphthylamide (BANA) by plaque with clinical parameters and subgingival levels of spirochetes in periodontal patients. Journal of dental research. 1988;67:1505–9. doi: 10.1177/00220345880670121201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Syed SA, Gusberti FA, Loesche WJ, Lang NP. Diagnostic potential of chromogenic substrates for rapid detection of bacterial enzymatic activity in health and disease associated periodontal plaques. Journal of periodontal research. 1984;19:618–21. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0765.1984.tb01327.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Loesche WJ, Syed SA, Stoll J. Trypsin-like activity in subgingival plaque. A diagnostic marker for spirochetes and periodontal disease? Journal of periodontology. 1987;58:266–73. doi: 10.1902/jop.1987.58.4.266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Grisi MF, Novaes AB, Ito IY, Salvador SL. Relationship between clinical probing depth and reactivity to the BANA test of samples of subgingival microbiota from patients with periodontitis. Brazilian dental journal. 1998;9:77–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Loesche W, Bretz W, Killoy W, Rau C, Weber H, Lopatin D. Detection of T. denticola and B. gingivalis in plaque with Perioscreen. Apud Journal of Dental Research. 1989;68(special issue):241. (abstract 482) [Google Scholar]

- 95.Yoneda M, Masuo Y, Suzuki N, Iwamoto T, Hirofuji T. Relationship between the beta-galactosidase activity in saliva and parameters associated with oral malodor. Journal of breath research. 2010;4:017108. doi: 10.1088/1752-7155/4/1/017108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.De Jong MH, Van der Hoeven JS. The growth of oral bacteria on saliva. Journal of dental research. 1987;66:498–505. doi: 10.1177/00220345870660021901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Van der Hoeven JS, Camp PJ. Synergistic degradation of mucin by Streptococcus oralis and Streptococcus sanguis in mixed chemostat cultures. Journal of dental research. 1991;70:1041–4. doi: 10.1177/00220345910700070401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Gossrau R. [Azoindoxyl methods for the investigation of hydrolases. II. Biochemical and histochemical studies of acid beta-galactosidase (author's transl)] Histochemistry. 1977;51:219–37. doi: 10.1007/BF00567226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Sterer N, Greenstein RB, Rosenberg M. Beta-galactosidase activity in saliva is associated with oral malodor. Journal of dental research. 2002;81:182–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Toda K, Li J, Dasgupta PK. Measurement of Ammonia in Human Breath with a Liquid-Film Conductivity Sensor. Analytical chemistry. 2006;78:7284–91. doi: 10.1021/ac060965m. 2006/10/01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Iwanicka-Grzegorek K, Lipkowska E, Kepa J, Michalik J, Wierzbicka M. Comparison of ninhydrin method of detecting amine compounds with other methods of halitosis detection. Oral diseases. 2005;11(Suppl 1):37–39. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-0825.2005.01087.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Iwakura M, Yasuno Y, Shimura M, Sakamoto S. Clinical characteristics of halitosis: Differences in two patient groups with primary and secondary complaints of halitosis. Journal of dental research. 1994;73:1568–74. doi: 10.1177/00220345940730091301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Rosing CK, Gomes SC, Bassani DG, Oppermann RV. Effect of chewing gums on the production of volatile sulfur compounds (VSC) in vivo. Acta odontologica latinoamericana: AOL. 2009;22:11–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Fedorowicz Z, Aljufairi H, Nasser M, Outhouse TL, Pedrazzi V. Mouthrinses for the treatment of halitosis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008:CD006701. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD006701.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Kara C, Tezel A, Orbak R. Effect of oral hygiene instruction and scaling on oral malodour in a population of Turkish children with gingival inflammation. International journal of paediatric dentistry / the British Paedodontic Society [and] the International Association of Dentistry for Children. 2006;16:399–404. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-263X.2006.00769.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Klokkevold PR. Oral malodor: A periodontal perspective. Journal of the California Dental Association. 1997;25:153–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Roldan S, Herrera D, Santa-Cruz I, O’Connor A, Gonzalez I, Sanz M. Comparative effects of different chlorhexidine mouth-rinse formulations on volatile sulphur compounds and salivary bacterial counts. Journal of clinical periodontology. 2004;31:1128–34. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051X.2004.00621.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Winkel EG, Roldan S, Van Winkelhoff AJ, Herrera D, Sanz M. Clinical effects of a new mouthrinse containing chlorhexidine, cetylpyridinium chloride and zinc-lactate on oral halitosis. A dual-center, double-blind placebo-controlled study. Journal of clinical periodontology. 2003;30:300–6. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-051x.2003.00342.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Seemann R, Kison A, Bizhang M, Zimmer S. Effectiveness of mechanical tongue cleaning on oral levels of volatile sulfur compounds. J Am Dent Assoc. 2001;132:1263–7. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.2001.0369. quiz 1318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Pryse-Phillips W. An olfactory reference syndrome. Acta psychiatrica Scandinavica. 1971;47:484–509. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1971.tb03705.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]