Abstract

Dental caries (decay) is an international public health challenge, especially amongst young children. Early childhood caries (ECC) is a serious public health problem in both developing and industrialized countries. ECC can begin early in life, progresses rapidly in those who are at high risk, and often goes untreated. Its consequences can affect the immediate and long-term quality of life of the child's family and can have significant social and economic consequences beyond the immediate family as well. ECC can be a particularly virulent form of caries, beginning soon after dental eruption, developing on smooth surfaces, progressing rapidly, and having a lasting detrimental impact on the dentition. Children experiencing caries as infants or toddlers have a much greater probability of subsequent caries in both the primary and permanent dentitions. The relationship between breastfeeding and ECC is likely to be complex and confounded by many biological variables, such as mutans streptococci, enamel hypoplasia, intake of sugars, as well as social variables, such as parental education and socioeconomic status, which may affect oral health. Unlike other infectious diseases, tooth decay is not self-limiting. Decayed teeth require professional treatment to remove infection and restore tooth function. In this review, we give detailed information about ECC, from its diagnosis to management.

Keywords: Early childhood caries, etiology, feeding, fluoride

INTRODUCTION

Dental caries is the most common chronic infectious disease of childhood, caused by the interaction of bacteria, mainly Streptococcus mutans, and sugary foods on tooth enamel. S. mutans can spread from mother to baby during infancy and can inoculate even pre-dentate infants. These bacteria break down sugars for energy, causing an acidic environment in the mouth and result in demineralization of the enamel of the teeth and dental caries.[1] Early childhood caries (ECC) is a serious public health problem in both developing and industrialized countries.[2] ECC can begin early in life, progresses rapidly in those who are at high risk, and often goes untreated.[3,4] Its consequences can affect the immediate and long-term quality of life of the child and family, and can have significant social and economic consequences beyond the immediate family as well.[5]

DESCRIPTION

Dental caries in toddlers and infants has a distinctive pattern. Different names and terminology have been used to refer to the presence of dental caries among very young children.[6] The definitions first used to describe this condition were related to etiology, with the focus on inappropriate use of nursing practices. The following terms are used interchangeably: Early childhood tooth decay, early childhood caries, baby bottle-fed tooth decay, early childhood dental decay, comforter caries, nursing caries, maxillary anterior caries, rampant caries, and many more.[7,8] Some of these terms indicate the causes of dental caries in pre-school children.[8] Baby bottle-fed tooth decay refers to decay in an infant's teeth, associated with what the baby drinks.[9] However, some authors use the term “nursing caries” because it designates inappropriate bottle use and nursing practices as the causal factors.[7,10] However, the term “early childhood caries” is becoming increasingly popular with dentists and dental researchers alike.[8,11]

The term “early childhood caries” was suggested at a 1994 workshop sponsored by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in an attempt to focus attention on the multiple factors (i.e. socioeconomic, behavioral, and psycho-social) that contribute to caries at such early ages, rather than ascribing sole causation to inappropriate feeding methods.[12] ECC is defined as “the presence of one or more decayed (non-cavitated or cavitated lesions), missing teeth (due to caries), or filled tooth surfaces in any primary tooth in a child 72 of months age or younger. In children younger than 3 years of age, any sign of smooth-surface caries is indicative of severe early childhood caries (S-ECC). From ages 3 through 5, one or more cavitated, missing teeth (due to caries), or filled smooth surfaces in primary maxillary anterior teeth, or decayed, missing, or filled score of ≥4 (age 3), ≥5 (age 4), or ≥6 (age 5) surfaces constitutes S-ECC.[13]

In the initial phase, ECC is recognized as a dull, white demineralized enamel that quickly advances to obvious decay along the gingival margin.[14] Primary maxillary incisors are generally affected earlier than the four maxillary anterior teeth which are often involved concurrently.[15] Carious lesions may be found on either the labial or lingual surfaces of the teeth and, in some cases, on both.[16] The decayed hard tissue is clinically evident as a yellow or brown cavitated area. In older children, whose entire primary dentition is fully erupted, it is not unusual to see considerable advancement of the dental damage.

EPIDEMIOLOGY

Despite the decline in the prevalence of dental caries in children in the western countries, caries in pre-school children remains a problem in both developed and developing countries. ECC has been considered to be at epidemic proportions in the developing countries.[4,17]

A comprehensive review of the occurrence of the caries on maxillary anterior teeth in children, including numerous studies from Europe, Africa, Asia, the Middle East, and North America, found the highest caries prevalence in Africa and South-East Asia.[18] The prevalence of ECC is estimated to range from 1 to 12% in infants from developed countries.[19]

Prevalence of ECC is a not a common finding relative to some European countries (England, Sweden, and Finland), with the available prevalence data ranging from below 1% to 32%.[20,21] However, this figure is rising by as much as 56% in some eastern European countries.[22] In US, pre-school children data from a more recent study indicate that the prevalence of dental caries of children 2–5 years of age had increased from 24% in 1988–1994 to 28% in 1999–2004. Overall, considering all 2–5-year olds, the 1999-2004 survey indicates that 72% of decayed or filled tooth surfaces remain untreated.[14,23,24] The prevalence of ECC children in the general population of Canada is less than 5%; but in high-risk population, 50–80% are affected.[25,26,27] Studies reveal that the prevalence percentage of ECC in 25- to 36-month olds[28] is 46% and the reported prevalence in Native Canadian 3-year-olds[29] has been as high as 65%.

Published studies show higher prevalence figures for 3-year-olds, which ranges from 36 to 85%[30–32] in Far East Asia region, whereas this figure is 44% for 8- to 48-month olds[33] reported in Indian studies. ECC has been considered at epidemic proportions in the developing countries.[34] Studies conducted in the Middle East have shown that the prevalence of dental caries in 3-year-olds is between 22% and 61%[35–37] and in Africa it is between 38% and 45%.[38,39]

ETIOLOGY

The etiology of ECC is multifactorial and has been well established. ECC is frequently associated with a poor diet[40] and bad oral health[14] habits.

Microbiological risk factors

S. mutans and Streptococcus sobrinus are the main cariogenic micro-organisms.[41,42] These acid-producing pathogens inhabiting the mouth cause damage by dissolving tooth structures in the presence of fermentable carbohydrates such as sucrose, fructose, and glucose.[43,44] Most of the investigations[15,45,46] have shown that in children with ECC, S. mutans has regularly exceeded 30% of the cultivable plaque flora. These bacterial masses are often associated with carious lesions, white spot lesions, and sound tooth surfaces near the lesions. Conversely, S. mutans typically constitutes less than 0.1% of the plaque flora in children with negligible to no caries activity.[47] It is well known that initial acquisition of mutans streptococci (MS) by infants occurs during a well-delineated age range that is being designated as the window of infectivity.[48] Most of the long-term studies also demonstrated that the individuals with low infection levels in this period are less likely to be infected with MS, and subsequently have the lowest level of risk of developing caries.[49,50] This may be explained by the competition between the oral bacteria, resulting in the invasion of the niches, where MS can easily colonize, by less pathogenic species.[51]

Vertical transmission, also known as mother-to-child transmission, is the transmission of an infection or other disease from caregiver to child. The major reservoir from which infants acquire MS is their mothers. The early evidence for this concept comes from bacteriocin typing studies[52–54] where MS isolated from mothers and their infants demonstrated identical bacteriocin typing patterns. More advanced technology that utilized chromosomal DNA patterns or identical plasmids provided more compelling evidence to substantiate the concept of vertical transmission.[55–58]

Feeding practices

Inappropriate use of baby bottle has a central role in the etiology and severity of ECC. The rationale is the prolonged bedtime use of bottles with sweet content, especially lactose. Most of the studies have shown significant correlation between ECC and bottle-feeding and sleeping with a bottle.[59–61] Breastfeeding provides the perfect nutrition for infant, and there are a number of health benefits to the breastfed child, including a reduced risk of gastrointestinal and respiratory infections.[62] However, frequent and prolonged contact of enamel with human milk has been shown to result in acidiogenic conditions and softening of enamel. Increasing the time per day that fermentable carbohydrates are available is the most significant factor in shifting the re-mineralization equilibrium toward de-mineralization.[63] There appears to be a clinical consensus amongst dental practitioners that prolonged and nocturnal breastfeeding is associated with an increased risk of ECC, especially after the age of 12 months. These conditions explained by less saliva production at night result in higher levels of lactose in the resting saliva and dental plaque for longer than would be expected during the day. Thereby, balance is shifted toward de-mineralization rather than re-mineralization during the night because of the insufficient protection caused by reduced nocturnal salivary flow.[64,65]

Sugars

In general, perspective dental caries is accepted as primarily a microbial disease, but few would disagree that dietary features play a crucial and a secondary role. Numerous worldwide epidemiologic studies, laboratory and animal experiments, as well as human investigations after the World War II have contributed to much of the knowledge on the etiology and natural history of caries.[66]

Fermentable carbohydrates are a factor in the development of caries. The small size of sugar molecules allows salivary amylase to split the molecules into components that can be easily metabolized by plaque bacteria.[67] This process leads to bacteria producing acidic end products with subsequent de-mineralization of teeth[68,69] and increased risk for caries on susceptible teeth. Some authors[70,71] found a positive relationship between sugar intake and the incidence of dental caries where fluoridation was minimal and dental hygiene was poor. The length of time of exposure of the teeth to sugar is the principal factor in the etiology of dental caries; it is known that acids produced by bacteria after sugar intake persist for 20–40 min. Some authors[72] studied the clearance of glucose, fructose, sucrose, maltose, and sorbitol rinses, as well as chocolate bars, white bread, and bananas, from the oral cavity. Sucrose is removed the quickest, while sorbitol and food residues stay in the mouth longer. Retentiveness of the food and the presence of protective factors in foods (calcium, phosphates, fluoride) are considered as other factors that contribute to de-mineralization.

The best available evidence indicates that the level of dental caries is low in countries where the consumption of free sugars is below 40–55 g per person per day.[73] Caries risk is greatest if sugars are consumed at high frequency and are in a form that is retained in the mouth for long periods.[74] Non-milk extrinsic sugars (NMES) have also been widely implicated as the cause of caries, while milk sugars are not.[75] However, consumption of milk-based formulas for infant feeding, even without sucrose in their formulation, proved to be cariogenic.[76] The relationship between diet and dental caries has become weaker in contemporary society and this has been attributed to the widespread use of fluoride.[77] There is evidence to show that many groups of people with habitually high consumption of sugars also have levels of caries higher than the population averages.

Socioeconomic factors

Association between ECC and the socioeconomic status (SES) has been well documented. Studies suggested that ECC is more commonly found in children who live in poverty or in poor economic conditions,[35,40,44,78,79] who belong to ethnic and racial minorities,[80] who are born to single mothers,[81] whose parents have low educational level, especially those of illiterate mothers.[35,82,83] In these populations, due to the prenatal and perinatal malnutrition or undernourishment, these children have an increased risk for enamel hypoplasia and exposure to fluorine is probably insufficient,[80] and there is a greater preference for sugary foods.[84]

The possible influence of SES on dental health may also be a consequence of differences in dietary habits and the role of sugar in the diet.[85] In their review on inequalities in oral health, Sheiham and Watt indicated that the main causes of inequalities in oral health are differences in patterns of consumption of non-milk sugars and fluoride toothpaste.[86] Weinstein[4] emphasizes the discrepancy in ECC prevalence rate: 1–12% in developed countries, whereas it as high as 70% in developing countries or within select immigrant or ethnic minority populations. Authors in Ref.[23] confirm that children with parents in the lowest income group had mean Decayed, Missing, and Filled Teeth (dmft) scores four times as high as children with parents in the highest income group.

DIAGNOSIS

ECC is initially recognized as a dull, white hand of de-mineralized enamel that quickly advances to obvious decay along the gingival margin.[31] The decay is generally first seen on the primary maxillary incisors, and the four maxillary anterior teeth are often involved concurrently.[87] Carious lesions may be found on either the labial or lingual surfaces of the teeth and, in some cases, on both.[40] The decayed hard tissue is clinically evident as a yellow or brown cavitated area. In the older child whose entire primary dentition is fully erupted, it is not unusual to see considerable advancement of the dental damage.

Furthermore, the expression S-ECC was adopted in lieu of rampant caries in the presence of at least one of the following criteria:

Any sign of caries on a smooth surface in children younger than 3 years.

Any smooth surface of an antero-posterior deciduous tooth that is decayed, missing (due to caries), or filled in children between 3 and 5 years old.

The dmft index equal to or greater than 4 at the age of 3 years, 5 at the age of 4 years, and 6 at the age of 5 years.[88]

CONSEQUENCES OF UNTREATED DENTAL CARIES IN CHILDREN

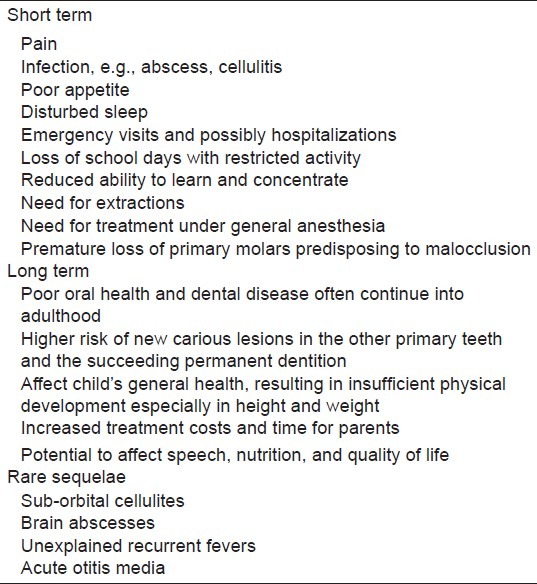

Although largely preventable by early examination, identification of individual risk factors, parental counseling and education, and initiation of preventive care procedures such as topical fluoride application, the progressive nature of dental disease can quickly diminish the general health and quality of life for the affected infants, toddlers, and children.[89] Failure to identify and prevent dental disease has consequential and costly long-term adverse effects [Table 1]. As treatment for ECC is delayed, the child's condition worsens and becomes more difficult to treat, the cost of treatment increases, and the number of clinicians who can perform the more complicated procedures diminishes.

Table 1.

A summary of the consequences of leaving untreated carious primary teeth

Oral health means more than just healthy teeth. Oral health affects people physically and psychologically, and influences how they grow, look, speak, chew, taste food, and socialize, as well as their feelings of social well-being.[90] Children's quality of life can be seriously affected by severe caries because of pain and discomfort which could lead to disfigurement, acute and chronic infections, and altered eating and sleeping habits, as well as risk of hospitalization, high treatment costs, and loss of school days with the consequent diminished ability to learn.[91] In most small children, ECC is associated with reduced growth and reduced weight gain due to insufficient food consumption to meet the metabolic and growth needs of children less than 2 years old.[91] Children of 3 years of age with nursing caries weighed about 1 kg less than control children[92] because toothache and infection alter eating and sleeping habits, dietary intake, and metabolic processes. Disturbed sleep affects glucosteroid production. In addition, there is suppression of hemoglobin from depressed erythrocyte production. Early tooth loss caused by dental decay has been associated with the failure to thrive, impaired speech development, absence from and inability to concentrate in school, and reduced self-esteem.[92–94]

At the level of family consequences, there is a troubling association between ECC and child maltreatment. Sheller and colleagues[95,96] concluded that a dysfunctional family or social situation can lead to a recurrence of ECC, often with emotional outbursts and the threat of or actual violence. The relationship between ECC and neglect is well established, but only recently have child maltreatment experts included dental caries in their list of health conditions that predispose children to maltreatment.[97,98]

Untreated oral disease can exacerbate the already fragile conditions of many children with special health care needs[99] because of the prevalence of chronic medical conditions such as seizure disorders or severe emotional disturbances. For example, it can complicate the treatment of organ and bone marrow transplants (sometimes resulting in death); it can result in severe complications (e.g., pneumonia, urinary tract infections, fever, and generalized infections of the entire body); and it can cause infection of a defective heart valve (resulting in death 50% of the time).[99]

A third possible mechanism of how untreated severe caries with pulpitis affects growth is that pulpitis and chronic dental abscesses affect growth by causing chronic inflammation that affects metabolic pathways where cytokines affect erythropoiesis.[100] For example, interleukin-1 (IL-1), which has a wide variety of actions in inflammation, can induce inhibition of erythropoiesis. This suppression of hemoglobin can lead to anemia of chronic disease, as a result of depressed erythrocyte production in the bone marrow.[101,102] One of the best predictors of future caries is previous caries experience.[103,104] Children under the age of 5 with a history of dental caries should automatically be classified as being at high risk for future decay. However, the absence of caries is not a useful caries risk predictor for infants and toddlers because even if these children are at high risk, there may not have been enough time for carious lesion development.[105] Since white spot lesions are the precursors to cavitated lesions, they will be apparent before cavitations. These white spot lesions are most often found on enamel smooth surfaces close to the gingiva. Although only a few studies have examined staining of pits and fissures[106] or white spot lesions[107] as a caries risk variable, such lesions should be considered equivalent to caries when determining caries risk in young children.

Tooth extraction is a common and necessary treatment for advanced caries. Premature loss of molars is likely to result in future orthodontic problems.[96] Therefore, children affected by ECC are likely to continue having oral health problems for which treatment is often financially out of reach for their parents. Furthermore, caries in the early years has been associated with caries in late childhood.[108,109]

PREVENTION OF EARLY CHILDHOOD CARIES

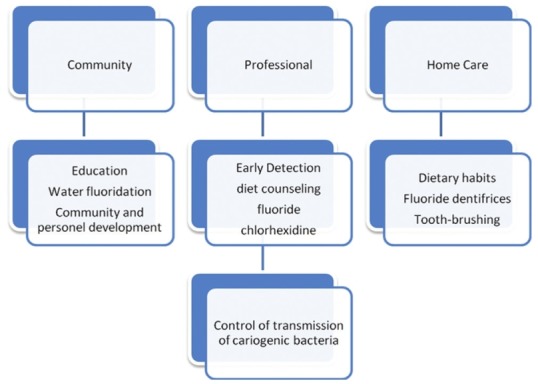

There are three general approaches that have been used to prevent ECC [Figure 1]. All three approaches include training of mothers or caregivers to follow healthy dietary and feeding habits in order to prevent the development of ECC.

Figure 1.

Strategies for the prevention of ECC[113]

Prevention of maternal bacterial transmission to the child

The strategy to combat the early transmission of cariogenic bacteria from parents to their offsprings is often named primary-primary prevention. The preventive intervention is most often directed to pregnant women and/or mothers of newborn babies. This includes the following.

A. Reduce the bacteria in the mouth of the mother or primary caregiver. Earlier studies suggest that infants acquire MS from their mothers and only after the eruption of primary teeth.[49,50] Preventive interventions for the purpose of reducing the transmission of bacteria from mothers to children improve the likelihood of better oral health for the child.[110] Effective approach in the prevention of dental caries is the suppression of S. mutans in the mouth of the child's primary caregiver (usually the mother). Chemical suppression by use of chlorhexidine gluconate in the form of mouth rinses, gels, and dentifrices has been shown to reduce oral microorganisms.[111,112]

B. Minimize the transmission of bacteria that cause tooth decay. Minimizing saliva-sharing activities between children and parents/caregivers limits bacterial transmission. Examples include avoiding the sharing of utensils, food, and drinks, discouraging a child from putting his/her hand in the caregiver's mouth, not licking a pacifier before giving it to the child, and not sharing toothbrushes. The goal is to prevent or delay children as long as possible from acquiring the bacteria that cause tooth decay.

Oral health education

Dental caries cannot occur without the substrate component of sugar. Therefore, much of the professional advice and practical research has focused on modification of the infant diet and feeding habits through education of the parents.[113,114] Child health professionals, including but not limited to physicians, physician assistants, nurse practitioners, and nurses, can play a significant role in reducing the burden of this disease. While most children do not visit a dentist until the age of 3 years, children have visited a child health professional up to 11 times for well-child visits by this age.[113] Oral health education is a designed package of information, learning activities, or experiences that are intended to produce improved oral health.[115] With the primary goal of disease prevention, its purpose is to facilitate decision-making for oral health practices and to encourage appropriate choices for these behaviors.

Effective health education may thus[116]

produce changes in knowledge;

induce or clarify values;

bring about some shift in belief or attitudes;

facilitate the achievement of skills; and

bring about change in behaviors or lifestyles.

Health promotion programs to stimulate tooth brushing have been among the most successful educational programs.[117,118] Cross-sectional surveys, clinical trials, and experiments for tooth brushing research studies involving populations of 1450–1545 children have found that tooth brushing with flossing twice a day resulted in increased tooth retention.[117]

The American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry (AAPD) has given recommendations on anticipatory guidance, bottle-feeding habits to prevent ECC, and infant/toddler oral hygiene care.[88]

Avoiding caries-promoting feeding behaviors

Infants should not be put to sleep with a bottle containing fermentable carbohydrates.

Ad libitum breastfeeding should be avoided after the first primary tooth begins to erupt and other dietary carbohydrates are introduced.

Parents should be encouraged to have infants drink from a cup as they approach their first birthday. Infants should be weaned from the bottle at 12-14 months of age.

Repetitive consumption of any liquid containing fermentable carbohydrates from a bottle or no-spill training cup should be avoided.

Between-meal snacks and prolonged exposures to foods and juice or other beverages containing fermentable carbohydrates should be avoided.

Fluoride

The use of fluorides for dental purposes began in the 19th century. Fluorides are found naturally throughout the world.[119] They are present to some extent in all foods and water, so that all humans ingest some fluoride on a daily basis. In addition, fluorides are used by communities as a public health measure to adjust the concentration of fluoride in drinking water to an optimum level (water fluoridation); by individuals in the form of toothpastes, rinses, lozenges, chewable tablets, drops; and by the dental professionals in the professional application of gels, foams, and varnishes.

Fluoride varnish is a concentrated topical fluoride with a resin or synthetic base. At least 19 fluoride varnish reviews,[120] including a systematic review[121] and three meta-analyses,[122–124] have been published in English. In the last three decade, a great deal of research published that evaluated fluoride varnish efficacy in the permanent teeth of school-aged children,[125] regarding fluoride varnish differed for permanent and primary teeth. All of these studies stated, “The evidence for the benefit of applying fluoride varnish to permanent teeth is generally positive.” Fluoride varnish works by increasing the concentration of fluoride in the outer surface of teeth, thereby enhancing fluoride uptake during early stages of de-mineralization. The varnish hardens on the tooth as soon as it contacts saliva, allowing the high concentration of fluoride to be in contact with tooth enamel for an extended period of time (about 1–7 days). This is a much longer exposure compared to that of other high-dose topical fluorides such as gels or foams, which is typically 10–15 minutes. The amount of fluoride deposited in the tooth surface is considerably greater in de-mineralized versus sound tooth surfaces.[126,127] Thus, the benefits of fluoride varnish are greatest for individuals at moderate risk or high risk for de-mineralization or tooth decay.[128]

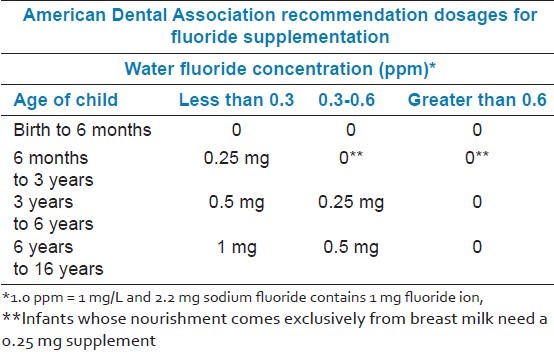

There is a global consensus that regular use of fluoride (F) toothpaste constitutes a cornerstone in child dental health. In fact, a global survey revealed that most experts addressed F toothpaste as the main reason for the dramatic decline in caries during the last decade of the 20th century.[129] Moreover, toothpaste is probably the most readily available form of F and tooth brushing is a convenient and approved habit in most cultures.[130] Working groups within national Health Technology Agencies have independently and in parallel presented strong scientific evidence that daily tooth brushing with F toothpaste is the most cost-effective, self-applied method to prevent caries at practically all ages.[131–134] Because small children usually swallow 30% of the paste, it is important to limit the amount of toothpaste to a pea size or less.[135] According to Douglass et al.[1] the amount of toothpaste should not exceed the size of a rice grain or the tip of a pencil eraser for children as young as 6–12 months of age. Fluoride products such as toothpaste, mouth rinse, and dental office topicals have been shown to reduce caries between 30% and 70% compared with no fluoride therapy.[136,137] Because young children tend to swallow toothpaste when they are brushing, which may increase their exposure to fluoride, guidelines [Table 2] have been established to moderate their risk of developing dental fluorosis while optimizing the benefits of fluoride, by the American Dental Association (ADA) (2008)[138]

Table 2.

Recommended dosages for fluoride supplementation chart

The most common method for systematically applied fluoride is fluoridated drinking water shown to be effective in reducing the severity of dental decay in entire populations. Fluoridation of community drinking water is the precise adjustment of the existing natural fluoride concentration in drinking water to a safe level that is recommended for caries prevention. The United States Public Health Service has established the optimum concentration for fluoride in the water in the range of 0.7–1.2 mg/L.[139] Reductions in childhood dental caries attributable to fluoridation were approximately from 40 to 60% from 1949 to 1979, but in the next decade, the estimates were lower: from 18% to 40%.[113,134,139] This is likely caused by the increasing use of fluoride from other sources, with the widespread use of fluoride toothpaste probably being the most important factor.[113,133]

TREATMENT

Treatment of ECC can be accomplished through different types of intervention, depending on the progression of the disease, the child's age, as well as the social, behavioral, and medical history of the child. Examining a child by his or her first birthday is ideal in the prevention and intervention of ECC.[88] During this initial visit, conducting a risk assessment can provide baseline data necessary to counsel the parent on the prevention of dental decay. Children at low risk may not need any restorative therapy. Children at moderate risk may require restoration of progressing and cavitated lesions, while white spot and enamel proximal lesions should be treated by preventive techniques and monitored for progression. Children at high risk, however, may require earlier restorative intervention of enamel proximal lesions, as well as intervention of progressing and cavitated lesions to minimize continual caries development.[140]

The current standard of care for treatment of S-ECC usually necessitates general anesthesia with all of its potential complications because the level of co-operative behavior of babies and pre-school children is less than ideal.

Stainless steel (preformed) crowns are pre-fabricated crown forms which can be adapted to individual primary molars and cemented in place to provide a definitive restoration.[141] They have been indicated for the restoration of primary and permanent teeth with caries, cervical decalcification, and/or developmental defects (e.g., hypoplasia, hypocalcification), when failure of other available restorative materials is likely (e.g., interproxima caries extending beyond line angles, patients with bruxism), following pulpotomy or pulpectomy, for restoring a primary tooth that is to be used as an abutment for a space maintainer, or for the intermediate restoration of fractured teeth.

Another approach of treating dental caries in young children is Atraumatic Restorative Treatment (ART). The ART is a procedure based on removing carious tooth tissues using hand instruments alone and restoring the cavity with an adhesive restorative material.[142–144] At present, the restorative material is glass ionomer. ART is a simple technique with many advantages, such as it reduces pain and fear during dental treatment,[145] it does not require electricity;[146] and it is more cost-effective than the traditional approach using amalgam.[147] It is an alternative treatment available to a large part of the world's population.[148] In addition, it is mostly indicated for use in children, as it is reportedly atraumatic because no rotary instruments are used and in most cases no local anesthesia is needed.[149]

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared

REFERENCES

- 1.Douglass JM, Douglass AB, Silk HJ. A practical guide to infant oral health. Am Fam Physician. 2004;70:2113–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Livny A, Assali R, Sgan-Cohen H. Early Childhood Caries among a Bedouin community residing in the eastern outskirts of Jerusalem. BMC Public Health. 2007;7:167. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-7-167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Grindefjord M, Dahllof G, Modeer T. Caries development in children from 2.5 to 3.5 years of age: A longitudinal study. Caries Res. 1995;29:449–54. doi: 10.1159/000262113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Weinstein P, Domoto P, Koday M, Leroux B. Results of a promising open trial to prevent baby bottle tooth decay: A fluoride varnish study. ASDC J Dent Child. 1994;61:338–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Inglehart MR, Filstrup SL, Wandera A. Oral health and quality of life in children. In: Inglehart M, Bagramian R, editors. Oral health-related quality of life. Chicago: Quintessence Publishing Co; 2002. pp. 79–88. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tinanoff N. Introduction to the Early Childhood Caries Conference: Initial description and current understanding. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 1998;26:5–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0528.1998.tb02089.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dilley GJ, Dilley DH, Machen JB. Prolonged nursing habit: A profile of patients and their families. ASDC J Dent Child. 1980;47:102–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ismail AI, Sohn W. A systematic review of clinical diagnostic criteria of early childhood caries. J Public Health Dent. 1999;59:171–91. doi: 10.1111/j.1752-7325.1999.tb03267.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lacroix I, Buithieu H, Kandelman D. La carie du biberon. J dentaire du Québec. 1997;34:360–74. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ripa LW. Nursing caries: A comprehensive review. Pediatr Dent. 1988;10:268–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Drury TF, Horowitz AM, Ismail AI, Maertens MP, Rozier RG, Selwitz RH. Diagnosing and reporting early childhood caries for research purposes.A report of a workshop sponsored by the National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research, the Health Resources and Services Administration, and the Health Care Financing Administration. J Public Health Dent. 1999;59:192–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1752-7325.1999.tb03268.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schroth RJ, Brothwell DJ, Moffatt ME. Caregiver knowledge and attitudes of preschool oral health and early childhood caries (ECC) Int J Circumpolar Health. 2007;66:153–67. doi: 10.3402/ijch.v66i2.18247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Suzuki N, Yoneda M, Naito T, Iwamoto T, Hirofuji T. Relationship between halitosis and psychologic status. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2008;106:542–7. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2008.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Berkowitz RJ. Causes, treatment and prevention of early childhood caries: A microbiologic perspective. J Can Dent Assoc. 2003;69:304–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.van Houte J, Gibbs G, Butera C. Oral flora of children with “nursing bottle caries”. J Dent Res. 1982;61:382–5. doi: 10.1177/00220345820610020201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kelly M, Bruerd B. The prevalence of baby bottle tooth decay among two native American populations. J Public Health Dent. 1987;47:94–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1752-7325.1987.tb01983.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vadiakas G. Case definition, aetiology and risk assessment of early childhood caries (ECC): A revisited review. Eur Arch Paediatr Dent. 2008;9:114–25. doi: 10.1007/BF03262622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Milnes AR. Description and epidemiology of nursing caries. J Public Health Dent. 1996;56:38–50. doi: 10.1111/j.1752-7325.1996.tb02394.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Burt BA, Eklund SA. Dentistry, dental practice, and the community. 5th ed. Philadelphia: Saunders; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Douglass JM, Tinanoff N, Tang JM, Altman DS. Dental caries patterns and oral health behaviors in Arizona infants and toddlers. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2001;29:14–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Davies GM, Blinkhorn FA, Duxbury JT. Caries among 3-year-olds in greater Manchester. Br Dent J. 2001;190:381–4. doi: 10.1038/sj.bdj.4800979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Szatko F, Wierzbicka M, Dybizbanska E, Struzycka I, Iwanicka-Frankowska E. Oral health of Polish three-year-olds and mothers’ oral health-related knowledge. Community Dent Health. 2004;21:175–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tang JM, Altman DS, Robertson DC, O’Sullivan DM, Douglass JM, Tinanoff N. Dental caries prevalence and treatment levels in Arizona preschool children. (30-1).Public Health Rep. 1997;112:319–29. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Reisine S, Douglass JM. Psychosocial and behavioral issues in early childhood caries. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 1998;26:32–44. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0528.1998.tb02092.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Harrison R, Wong T, Ewan C, Contreras B, Phung Y. Feeding practices and dental caries in an urban Canadian population of Vietnamese preschool children. ASDC J Dent Child. 1997;64:112–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Albert RJ, Cantin RY, Cross HG, Castaldi CR. Nursing caries in the Inuit children of the Keewatin. J Can Dent Assoc. 1988;54:751–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Harrison R, White L. A community-based approach to infant and child oral health promotion in a British Columbia First Nations community. Can J Community Dent. 1997;12:7–14. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rosenblatt A, Zarzar P. The prevalence of early childhood caries in 12- to 36-month-old children in Recife, Brazil. ASDC J Dent Child. 2002;69:319–24. 236. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Peressini S, Leake JL, Mayhall JT, Maar M, Trudeau R. Prevalence of early childhood caries among First Nations children, District of Manitoulin, Ontario. Int J Paediatr Dent. 2004;14:101–10. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-263x.2004.00532.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tsai AI, Chen CY, Li LA, Hsiang CL, Hsu KH. Risk indicators for early childhood caries in Taiwan. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2006;34:437–45. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0528.2006.00293.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Carino KM, Shinada K, Kawaguchi Y. Early childhood caries in northern Philippines. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2003;31:81–9. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0528.2003.00010.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jin BH, Ma DS, Moon HS, Paik DI, Hahn SH, Horowitz AM. Early childhood caries: Prevalence and risk factors in Seoul, Korea. J Public Health Dent. 2003;63:183–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1752-7325.2003.tb03497.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jose B, King NM. Early childhood caries lesions in preschool children in Kerala, India. Pediatr Dent. 2003;25:594–600. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Weinstein P, Harrison R, Benton T. Motivating parents to prevent caries in their young children: One-year findings. J Am Dent Assoc. 2004;135:731–8. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.2004.0299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rajab LD, Hamdan MA. Early childhood caries and risk factors in Jordan. Community Dent Health. 2002;19:224–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Al-Malik MI, Holt RD, Bedi R. The relationship between erosion, caries and rampant caries and dietary habits in preschool children in Saudi Arabia. Int J Paediatr Dent. 2001;11:430–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Al-Hosani E, Rugg-Gunn A. Combination of low parental educational attainment and high parental income related to high caries experience in pre-school children in Abu Dhabi. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 1998;26:31–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0528.1998.tb01921.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kiwanuka SN, Astrom AN, Trovik TA. Dental caries experience and its relationship to social and behavioural factors among 3-5-year-old children in Uganda. Int J Paediatr Dent. 2004;14:336–46. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-263X.2004.00570.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Masiga MA, Holt RD. The prevalence of dental caries and gingivitis and their relationship to social class amongst nursery-school children in Nairobi, Kenya. Int J Paediatr Dent. 1993;3:135–40. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-263x.1993.tb00069.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Davies GN. Early childhood caries--a synopsis. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 1998;26:106–16. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0528.1998.tb02102.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tanzer JM, Livingston J, Thompson AM. The microbiology of primary dental caries in humans. J Dent Educ. 2001;65:1028–37. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Nurelhuda NM, Al-Haroni M, Trovik TA, Bakken V. Caries experience and quantification of Streptococcus mutans and Streptococcus sobrinus in saliva of Sudanese schoolchildren. Caries Res. 2010;44:402–7. doi: 10.1159/000316664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Schafer TE, Adair SM. Prevention of dental disease.The role of the pediatrician. (v-vi).Pediatr Clin North Am. 2000;47:1021–42. doi: 10.1016/s0031-3955(05)70256-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Caufield PW, Griffen AL. Dental caries. An infectious and transmissible disease. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2000;47:1001–19. doi: 10.1016/s0031-3955(05)70255-8. v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Berkowitz RJ, Turner J, Hughes C. Microbial characteristics of the human dental caries associated with prolonged bottle-feeding. Arch Oral Biol. 1984;29:949–51. doi: 10.1016/0003-9969(84)90097-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Milnes AR, Bowden GH. The microflora associated with developing lesions of nursing caries. Caries Res. 1985;19:289–97. doi: 10.1159/000260858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Loesche WJ. Nutrition and dental decay in infants. Am J Clin Nutr. 1985;41:423–35. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/41.2.423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Caufield PW, Cutter GR, Dasanayake AP. Initial Acquisition of Mutans Streptococci by Infants: Evidence for a Discrete Window of Infectivity. J Dent Res. 1993;72:37–45. doi: 10.1177/00220345930720010501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ercan E, Dulgergil CT, Yildirim I, Dalli M. Prevention of maternal bacterial transmission on children's dental-caries-development: 4-year results of a pilot study in a rural-child population. Arch Oral Biol. 2007;52:748–52. doi: 10.1016/j.archoralbio.2007.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Turksel Dulgergil C, Satici O, Yildirim I, Yavuz I. Prevention of caries in children by preventive and operative dental care for mothers in rural Anatolia, Turkey. Acta Odontol Scand. 2004;62:251–7. doi: 10.1080/00016350410001685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Köhler B, Andréen I, Jonsson B. The earlier the colonization by mutans streptococci, the higher the caries prevalence at 4 years of age. Oral Microbiol Immunol. 1988;3:14–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-302x.1988.tb00598.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Davey AL, Rogers AH. Multiple types of the bacterium Streptococcus mutans in the human mouth and their intra-family transmission. Arch Oral Biol. 1984;29:453–60. doi: 10.1016/0003-9969(84)90026-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Berkowitz RJ, Jordan HV. Similarity of bacteriocins of Streptococcus mutans from mother and infant. Arch Oral Biol. 1975;20:725–30. doi: 10.1016/0003-9969(75)90042-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Berkowitz RJ, Jones P. Mouth-to-mouth transmission of the bacterium Streptococcus mutans between mother and child. Arch Oral Biol. 1985;30:377–9. doi: 10.1016/0003-9969(85)90014-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Caufield PW, Childers NK, Allen DN, Hansen JB. Distinct bacteriocin groups correlate with different groups of Streptococcus mutans plasmids. Infect Immun. 1985;48:51–6. doi: 10.1128/iai.48.1.51-56.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Caufield PW, Ratanapridakul K, Allen DN, Cutter GR. Plasmid-containing strains of Streptococcus mutans cluster within family and racial cohorts: Implications for natural transmission. Infect Immun. 1988;56:3216–20. doi: 10.1128/iai.56.12.3216-3220.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kulkarni GV, Chan KH, Sandham HJ. An investigation into the use of restriction endonuclease analysis for the study of transmission of mutans streptococci. J Dent Res. 1989;68:1155–61. doi: 10.1177/00220345890680070401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Caufield PW, Childers NK. Plasmids in Streptococcus mutans: Usefulness as epidemiological markers and association with mutacins. In: Hamada S, Michaelek S, editors. Proceedings of an International Conference on Cellular, Molecular, and Clinical Aspects of Streptococcus Mutans. Birmingham Ala: Elsevier Science Publishers; 1985. pp. 217–23. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Azevedo TD, Bezerra AC, de Toledo OA. Feeding habits and severe early childhood caries in Brazilian preschool children. Pediatr Dent. 2005;27:28–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Hallett KB, O’Rourke PK. Early childhood caries and infant feeding practice. Community Dent Health. 2002;19:237–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Oulis CJ, Berdouses ED, Vadiakas G, Lygidakis NA. Feeding practices of Greek children with and without nursing caries. Pediatr Dent. 1999;21:409–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kramer MS, Kakuma R. Optimal duration of exclusive breastfeeding. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2002;1:CD003517. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Ramos-Gomez F, Crystal YO, Ng MW, Tinanoff N, Featherstone JD. Caries risk assessment, prevention, and management in pediatric dental care. Gen Dent. 2010;58:505–17. quiz 18-9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Van Loveren C. Sugar alcohols: What is the evidence for caries-preventive and caries-therapeutic effects? Caries Res. 2004;38:286–93. doi: 10.1159/000077768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.van Palenstein Helderman WH, Soe W, van ‘t Hof MA. Risk factors of early childhood caries in a Southeast Asian population. J Dent Res. 2006;85:85–8. doi: 10.1177/154405910608500115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Naylor MN. Diet and the prevention of dental caries. J R Soc Med. 1986;79(Suppl 14):11–4. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Jensen ME. Diet and dental caries. Dent Clin North Am. 1999;43:615–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Birkhed D. Sugar substitutes--one consequence of the Vipeholm Study? Scand J Dent Res. 1989;97:126–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0722.1989.tb01441.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Harel-Raviv M, Laskaris M, Chu KS. Dental caries and sugar consumption into the 21st century. Am J Dent. 1996;9:184–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Marrs JA, Trumbley S, Malik G. Early childhood caries: Determining the risk factors and assessing the prevention strategies for nursing intervention. Pediatr Nurs. 2011;37:9–15. quiz 6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Sanders TA. Diet and general health: Dietary counselling. Caries Res. 2004;38(Suppl 1):3–8. doi: 10.1159/000074356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Luke GA, Gough H, Beeley JA, Geddes DA. Human salivary sugar clearance after sugar rinses and intake of foodstuffs. Caries Res. 1999;33:123–9. doi: 10.1159/000016505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Diet, nutrition and the prevention of chronic diseases. (1-149).World Health Organ Tech Rep Ser. 2003;916:i–vii. backcover. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Misra S, Tahmassebi JF, Brosnan M. Early childhood caries: A review. (61-2).Dent Update. 2007;34:556–8. doi: 10.12968/denu.2007.34.9.556. 64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Moynihan PJ. Update on the nomenclature of carbohydrates and their dental effects. J Dent. 1998;26:209–18. doi: 10.1016/s0300-5712(97)00010-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Erickson PR, McClintock KL, Green N, LaFleur J. Estimation of the caries-related risk associated with infant formulas. Pediatr Dent. 1998;20:395–403. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Zero DT. Sugars - the arch criminal? Caries Res. 2004;38:277–85. doi: 10.1159/000077767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Slavkin HC. Streptococcus mutans, early childhood caries and new opportunities. J Am Dent Assoc. 1999;130:1787–92. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.1999.0138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Weerheijm KL, Uyttendaele-Speybrouck BF, Euwe HC, Groen HJ. Prolonged demand breast-feeding and nursing caries. Caries Res. 1998;32:46–50. doi: 10.1159/000016429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Ramos-Gomez FJ, Tomar SL, Ellison J, Artiga N, Sintes J, Vicuna G. Assessment of early childhood caries and dietary habits in a population of migrant Hispanic children in Stockton, California. ASDC J Dent Child. 1999;66:395–403. 366. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Quinonez RB, Keels MA, Vann WF, Jr, McIver FT, Heller K, Whitt JK. Early childhood caries: Analysis of psychosocial and biological factors in a high-risk population. Caries Res. 2001;35:376–83. doi: 10.1159/000047477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Dini EL, Holt RD, Bedi R. Caries and its association with infant feeding and oral health-related behaviours in 3-4-year-old Brazilian children. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2000;28:241–8. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0528.2000.280401.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Wendt LK, Hallonsten AL, Koch G, Birkhed D. Analysis of caries-related factors in infants and toddlers living in Sweden. Acta Odontol Scand. 1996;54:131–7. doi: 10.3109/00016359609006019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Ruottinen S, Karjalainen S, Pienihakkinen K, Lagstrom H, Niinikoski H, Salminen M, et al. Sucrose intake since infancy and dental health in 10-year-old children. Caries Res. 2004;38:142–8. doi: 10.1159/000075938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Ismail AI, Tanzer JM, Dingle JL. Current trends of sugar consumption in developing societies. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 1997;25:438–43. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0528.1997.tb01735.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Sheiham A, Watt RG. The common risk factor approach: A rational basis for promoting oral health. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2000;28:399–406. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0528.2000.028006399.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Petti S, Cairella G, Tarsitani G. Rampant early childhood dental decay: An example from Italy. J Public Health Dent. 2000;60:159–66. doi: 10.1111/j.1752-7325.2000.tb03322.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Policy on early childhood caries (ECC): Classifications, consequences, and preventive strategies. Pediatr Dent. 2008;30:40–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Colak H, Dülgergil ÇT, Serdaroğlu İ. Ağız ve Diş Hastalıklarının Medikal, Psikososyal ve Ekonomik Etkilerinin Değerlendirilmesi. Sağlıkta Performans ve Kalite Dergisi. 2010;1:63–89. [Google Scholar]

- 90.Locker D. Concepts of oral health, disease and the quality of life. In: Slade GD, editor. Measuring oral health and quality of life. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina, Dental Ecology; 1977. pp. 11–23. [Google Scholar]

- 91.Petersen PE, Estupinan-Day S, Ndiaye C. WHO's action for continuous improvement in oral health. Bull World Health Organ. 2005;83:642. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Acs G, Lodolini G, Kaminsky S, Cisneros GJ. Effect of nursing caries on body weight in a pediatric population. Pediatr Dent. 1992;14:302–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Acs G, Shulman R, Ng MW, Chussid S. The effect of dental rehabilitation on the body weight of children with early childhood caries. Pediatr Dent. 1999;21:109–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Acs G, Lodolini G, Shulman R, Chussid S. The effect of dental rehabilitation on the body weight of children with failure to thrive: Case reports. Compend Contin Educ Dent. 1998;19:164–8. 70-1. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Sheller B, Williams BJ, Hays K, Mancl L. Reasons for repeat dental treatment under general anesthesia for the healthy child. Pediatr Dent. 2003;25:546–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Casamassimo PS, Thikkurissy S, Edelstein BL, Maiorini E. Beyond the dmft: The human and economic cost of early childhood caries. J Am Dent Assoc. 2009;140:650–7. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.2009.0250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Friedlaender EY, Rubin DM, Alpern ER, Mandell DS, Christian CW, Alessandrini EA. Patterns of health care use that may identify young children who are at risk for maltreatment. Pediatrics. 2005;116:1303–8. doi: 10.1542/peds.2004-1988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Valencia-Rojas N, Lawrence HP, Goodman D. Prevalence of early childhood caries in a population of children with history of maltreatment. J Public Health Dent. 2008;68:94–101. doi: 10.1111/j.1752-7325.2007.00077.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Foundation TDH. California children and families first initiative (Proposition 10). Why should there be a dental component? White Paper available from the Dental Health Foundation, 520 Third Street, Suite 205, Oakland, CA 94607, 1999 [Google Scholar]

- 100.Sheiham A. Dental caries affects body weight, growth and quality of life in pre-school children. Br Dent J. 2006;201:625–6. doi: 10.1038/sj.bdj.4814259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Means RT., Jr Recent developments in the anemia of chronic disease. Curr Hematol Rep. 2003;2:116–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Means RT, Jr, Krantz SB. Progress in understanding the pathogenesis of the anemia of chronic disease. Blood. 1992;80:1639–47. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Reisine S, Litt M, Tinanoff N. A biopsychosocial model to predict caries in preschool children. Pediatr Dent. 1994;16:413–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Birkeland JM, Broch L, Jorkjend L. Caries experience as predictor for caries incidence. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 1976;4:66–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0528.1976.tb01605.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Tinanoff N, Reisine S. Update on early childhood caries since the Surgeon General's Report. Acad Pediatr. 2009;9:396–403. doi: 10.1016/j.acap.2009.08.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Steiner M, Helfenstein U, Marthaler TM. Dental predictors of high caries increment in children. J Dent Res. 1992;71:1926–33. doi: 10.1177/00220345920710121401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.van Palenstein Helderman WH, van’t Hof MA, van Loveren C. Prognosis of caries increment with past caries experience variables. Caries Res. 2001;35:186–92. doi: 10.1159/000047454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.O’Sullivan DM, Tinanoff N. The association of early dental caries patterns with caries incidence in preschool children. J Public Health Dent. 1996;56:81–3. doi: 10.1111/j.1752-7325.1996.tb02401.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Johnsen DC, Gerstenmaier JH, DiSantis TA, Berkowitz RJ. Susceptibility of nursing-caries children to future approximal molar decay. Pediatr Dent. 1986;8:168–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Kishi M, Abe A, Kishi K, Ohara-Nemoto Y, Kimura S, Yonemitsu M. Relationship of quantitative salivary levels of Streptococcus mutans and S. sobrinus in mothers to caries status and colonization of mutans streptococci in plaque in their 2.5-year-old children. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2009;37:241–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0528.2009.00472.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.King N, Anthonappa R, Itthagarun A. The importance of the primary dentition to children - Part 1: Consequences of not treating carious teeth. Hong Kong Pract. 2007;29:52–61. [Google Scholar]

- 112.Kohler B, Andreen I. Mutans streptococci and caries prevalence in children after early maternal caries prevention: A follow-up at eleven and fifteen years of age. Caries Res. 2010;44:453–8. doi: 10.1159/000320168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Ismail AI. Prevention of early childhood caries. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 1998;26:49–61. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0528.1998.tb02094.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Dülgergil ÇT, Colak H. Rural Dentistry: Is it an imagination or obligation in Community Dental Health Education. Niger Med J. 2012;53:1–8. doi: 10.4103/0300-1652.99820. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Overton DA. Community oral health education. In: Mason J, editor. Concepts in Dental Public Health. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams and Wilkin; 2005. pp. 139–57. [Google Scholar]

- 116.Adair P, Ashcroft A. Theory-based approaches to the planning and evaluation of oral health education programmes. In: Pine CM, Harris R, editors. Community Oral Health. Berlin: Quintessence; 2007. pp. 307–31. [Google Scholar]

- 117.Curnow MM, Pine CM, Burnside G, Nicholson JA, Chesters RK, Huntington E. A randomised controlled trial of the efficacy of supervised toothbrushing in high-caries-risk children. Caries Res. 2002;36:294–300. doi: 10.1159/000063925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.de Almeida CM, Petersen PE, Andre SJ, Toscano A. Changing oral health status of 6- and 12-year-old schoolchildren in Portugal. Community Dent Health. 2003;20:211–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Ercan E, Bağlar S, Colak H. Topical Fluoride Application Methods in Dentistry. Cumhuriyet Dent J. 2010;13:27–33. [Google Scholar]

- 120.Weintraub JA. Fluoride varnish for caries prevention: Comparisons with other preventive agents and recommendations for a community-based protocol. Spec Care Dentist. 2003;23:180–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1754-4505.2003.tb00309.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Bader JD, Shugars DA, Bonito AJ. Systematic reviews of selected dental caries diagnostic and management methods. J Dent Educ. 2001;65:960–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Helfenstein U, Steiner M. Fluoride varnishes (Duraphat): A meta-analysis. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 1994;22:1–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0528.1994.tb01559.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Strohmenger L, Brambilla E. The use of fluoride varnishes in the prevention of dental caries: A short review. Oral Dis. 2001;7:71–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Marinho VC, Higgins JP, Logan S, Sheiham A. Fluoride varnishes for preventing dental caries in children and adolescents. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2002;3:CD002279. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD002279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Diagnosis and management of dental caries throughout life. National Institutes of Health Consensus Development Conference statement, March 26-28, 2001. J Dent Educ. 2001;65:1162–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Skold-Larsson K, Modeer T, Twetman S. Fluoride concentration in plaque in adolescents after topical application of different fluoride varnishes. Clin Oral Investig. 2000;4:31–4. doi: 10.1007/s007840050110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.ten Cate JM, Featherstone JD. Mechanistic aspects of the interactions between fluoride and dental enamel. Crit Rev Oral Biol Med. 1991;2:283–96. doi: 10.1177/10454411910020030101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Marinho VC, Higgins JP, Sheiham A, Logan S. Combinations of topical fluoride (toothpastes, mouthrinses, gels, varnishes) versus single topical fluoride for preventing dental caries in children and adolescents. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2004;1:CD002781. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD002781.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Bratthall D, Hansel-Petersson G, Sundberg H. Reasons for the caries decline: What do the experts believe? Eur J Oral Sci. 1996;104:416–22. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0722.1996.tb00104.x. discussion 23-5,30-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Marinho VC. Evidence-based effectiveness of topical fluorides. Adv Dent Res. 2008;20:3–7. doi: 10.1177/154407370802000102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Twetman S, Axelsson S, Dahlgren H, Holm AK, Kallestal C, Lagerlof F, et al. Caries-preventive effect of fluoride toothpaste: A systematic review. Acta Odontol Scand. 2003;61:347–55. doi: 10.1080/00016350310007590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Jones S, Burt BA, Petersen PE, Lennon MA. The effective use of fluorides in public health. Bull World Health Organ. 2005;83:670–6. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Seppa L. The future of preventive programs in countries with different systems for dental care. Caries Res. 2001;35(Suppl 1):26–9. doi: 10.1159/000049106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Twetman S, Garcia-Godoy F, Goepferd SJ. Infant oral health. Dent Clin North Am. 2000;44:487–505. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Gussy MG, Waters EG, Walsh O, Kilpatrick NM. Early childhood caries: Current evidence for aetiology and prevention. J Paediatr Child Health. 2006;42:37–43. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1754.2006.00777.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Featherstone JDB. The Continuum of Dental Caries–Evidence for a Dynamic Disease Process. J Dent Res. 2004;83:C39–42. doi: 10.1177/154405910408301s08. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Jenkins GN. Recent changes in dental caries. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed) 1985;291:1297–8. doi: 10.1136/bmj.291.6505.1297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.American Dental Association (ADA) Fluoridation facts. 2008. [Retrieved September 1]. from: http://www.ada.org/sections/newsAndEvents/pdfs/fluoridation_facts.pdf .

- 139.Populations receiving optimally fluoridated public drinking water: United States, 1992-2006. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2008;57:737–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.Tinanoff N, Douglass JM. Clinical decision-making for caries management in primary teeth. J Dent Educ. 2001;65:1133–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141.Kindelan SA, Day P, Nichol R, Willmott N, Fayle SA. UK National Clinical Guidelines in Paediatric Dentistry: Stainless steel preformed crowns for primary molars. Int J Paediatr Dent. 2008;18(Suppl 1):20–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-263X.2008.00935.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142.Dulgergil CT, Soyman M, Civelek A. Atraumatic restorative treatment with resin-modified glass ionomer material: Short-term results of a pilot study. Med Princ Pract. 2005;14:277–80. doi: 10.1159/000085750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143.Ercan E, Dülgergil ÇT, Dalli M, Yildirim I, Ince B, Çolak H. Anticaries effect of atraumatic restorative treatment with fissure sealants in suburban districts of Turkey. J Dent Sci. 2009;4:55–60. [Google Scholar]

- 144.Dallı M, Çolak H, Mustafa Hamidi M. Minimal intervention concept: A new paradigm for operative dentistry. J Investig Clin Dent. 2012 Feb 8; doi: 10.1111/j.2041-1626.2012.00117.x. doi:10.1111/j.2041-1626.2012.00117.x. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 145.Ercan E, Dulgergil CT, Soyman M, Dalli M, Yildirim I. A field-trial of two restorative materials used with atraumatic restorative treatment in rural Turkey: 24-month results. J Appl Oral Sci. 2009;17:307–14. doi: 10.1590/S1678-77572009000400008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 146.Frencken JE, Pilot T, Songpaisan Y, Phantumvanit P. Atraumatic restorative treatment (ART): Rationale, technique, and development. J Public Health Dent. 1996;56:135–40. doi: 10.1111/j.1752-7325.1996.tb02423.x. discussion 61-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 147.Seale NS, Casamassimo PS. Access to dental care for children in the United States: A survey of general practitioners. J Am Dent Assoc. 2003;134:1630–40. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.2003.0110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 148.Da Franca C, Colares V, Van Amerongen E. Two-year evaluation of the atraumatic restorative treatment approach in primary molars class I and II restorations. Int J Paediatr Dent. 2011;21:249–53. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-263X.2011.01125.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 149.Schriks MC, van Amerongen WE. Atraumatic perspectives of ART: Psychological and physiological aspects of treatment with and without rotary instruments. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2003;31:15–20. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0528.2003.00021.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]