Abstract

Background: living alone in later life has been linked to psychological distress but less is known about the role of the transition into living alone and the role of social and material resources.

Methods: a total of 21,535 person-years of data from 4,587 participants of the British Household Panel Survey aged 65+ are analysed. Participants provide a maximum 6 years' data (t0−t5), with trajectories of living arrangements classified as: consistently partnered/ with children/alone; transition from partnered to alone/with children to alone. General Health Questionnaire (GHQ)-12 caseness (score >3) is investigated using multi-level logistic regression, controlling for sex, age, activities of daily living, social and material resources.

Results: after a transition from partnered at t0 to alone at t1, the odds for GHQ-12 caseness increased substantially, but by t3 returned to baseline levels. The odds for caseness at t0 were highest for those changing from living with a child at t0 to living alone at t1 but declined following the transition to living alone. None of the covariates explained these associations. Living consistently alone did confer increased odds for caseness.

Conclusions: living alone in later life is not in itself a strong risk factor for psychological distress. The effects of transitions to living alone are dependent on the preceding living arrangement and are independent of social and material resources. This advocates a longitudinal approach, allowing identification of respondents' location along trajectories of living arrangements.

Keywords: psychological stress, life change events, widowhood, residence characteristics, social support, older people

Introduction

Despite recent declines in the proportion of people aged 65 and older living alone in the UK and across Europe [1], older people (particularly women) are still the most likely group to live alone in the UK, usually because they have outlived a partner [2]. There is an established literature showing that living alone in later life is a risk factor for loneliness in a range of international settings [3–6]. More broadly, living alone in later life has been linked to poor mental health, including depression [7]. This association is important not only in its own right, but also because poor mental health has been associated with an increased mortality risk in a variety of contexts [8–11]. Depression appears to be a particularly strong predictor of mortality in relation to vascular disease [12], supporting the argument that inflammatory mechanisms are a mediating factor.

Despite a wealth of cross-sectional research focusing on the state of living alone, the transition to living alone has received less attention as a determinant of mental health in later life. Existing research investigating transitions in living arrangements in later life has tended to focus on their relationship with mortality and institutionalisations [13] or is largely descriptive and does not explicitly consider health outcomes [14]. This focus is partly due to the need for longitudinal data in order to investigate the role of transitions, and also because it is often difficult to disentangle the effects of partnership status and living arrangements. As such, most previous studies have tended to compare co-resident partnership with living alone, without considering other potential living arrangements such as being unpartnered but living with children. Furthermore, studies will often include a wide age-range where divorce or separation is an important route out of marriage [15, 16]. In contrast, the transition to living alone in later life is most commonly preceded by widowhood, which may have different health consequences to divorce. Previous research suggests that widows and widowers tend to have worse mental health than married men and women, but it appears that this effect may not persist in the long term and tends to be concentrated in the period immediately surrounding the bereavement [15, 17]. This supports a ‘stress’ or ‘crisis’ model of bereavement suggesting that it is the process rather than the state of widowhood that negatively affects health and that these effects are transient [16].

This paper aims to contribute to this literature by using a long-running UK-based panel study to investigate how the transition into living alone in later life affects subsequent mental health and whether this transition has effects that are distinct from the consistent state of living alone. The analysis further explores whether associations between psychological distress and living alone can be explained by confounding factors such as social support [18] or socio-economic circumstances [19].

Methods

Study population

The British Household Panel Survey (BHPS) is a nationally representative panel study of individuals from 5,500 households first interviewed in 1991. Members of the original sample are followed up annually at each survey wave, even when they leave the original residence to form new households. The present analysis pools data from 18 annual waves of the survey (up to 2008), and includes respondents aged 65 years or older who completed a full interview at a minimum of two consecutive waves. At each survey wave, a new cohort of respondents becomes eligible for inclusion in our sample as they enter the required age range. Those who make a transition to living alone between two consecutive waves (t0 and t1) are initially identified. These respondents are then followed up for a maximum of 5 years (up to t5), provided they remain living alone during this follow-up period. Comparison groups are then selected, consisting of all those in the remaining sample who remain in a consistent living arrangement for up to 6 years (t0–t5), starting from the wave in which they first provided a full interview and were in the target age range. Trajectories were censored if respondents did not provide a full interview at a particular wave during the follow-up period, but 78% of respondents provided at least 4-year follow-up. The final sample includes a total of 1,991 and 2,596 women, contributing 9,404 and 12,131 person-years of data, respectively.

Living arrangements

Respondents are classified into five categories based on their living arrangements:

consistently partnered;

consistently with children;

consistently alone;

partnered to alone at t1; and

with children to alone at t1.

Those classified as living with a partner could also be living with children, but those classified as living with children could not be co-resident with a partner. A small proportion (∼2%) of observations show a respondent living with non-relatives or relatives other than a partner or child. As this is a relatively rare but highly heterogeneous living arrangement, it is difficult to classify and interpret and these observations are excluded from the analyses.

Outcome measure

The 12-item version of the GHQ-12, which is collected annually in BHPS, is used as a measure of psychological distress [20]. It has been successfully applied to older populations [21] and has been shown to be robust to retest effects in the BHPS [22]. Using the 12-point scoring system, a standard cut-off of a score >3 is used to define ‘caseness’, a threshold that has been shown to be appropriate in UK populations [23].

Covariates

Control variables are sex, age group, marital status, social support, health-related limitations to daily activities, self-assessed financial circumstances, change in financial circumstances, housing tenure and pension income availability. All covariates are time-varying and all except social support were measured at every wave. Five questions on social support (e.g. whether the respondent had someone to provide comfort or help in a crisis) were asked at odd-numbered waves and these responses were summed to produce a 10-point scale. Following Netuveli et al. the mean of scores the previous and subsequent waves were applied to the even-numbered waves. The scale was then dichotomised at the median (a score of 6) to provide a binary measure of high or low social support.

Statistical analysis

Multilevel binary logistic regression analysis is applied to predict the probability of being a GHQ-12 case. The repeated measures design means that each individual contributes a number of person-years to the data set. A random intercept is included to account for this clustering within individuals. To examine how the relationship between transition to living alone and psychological distress develops over time, an interaction between time (t0–t5) and living arrangements is added to the model. Using a nested approach, the covariates are added in two stages to examine their impact on the relationship between living arrangements and psychological distress. The first model includes only the key demographic variables (age and sex), the main effects for living arrangements and time plus the interaction between these two variables. Model 2 adds the social support and health variables and Model 3 adds the socio-economic covariates.

Results

Descriptive findings

Table 1 shows that a transition to living alone is observed in 12% and 16% of men and women, respectively [gender difference significant at 1% level (Pearson Chi-squared)]. Men and women who are consistently partnered are, on average, younger than those in other living arrangements [difference in means significant at 0.01% level (independent-samples t-test)]. The most common route into living alone is from partnership rather than from living with children. Among those moving from living with a partner at t0 to living alone at t1, the vast majority make this transition due to bereavement (85% of men and 92% of women) rather than through divorce or separation (3% for both men and women). A small proportion report still being married at t1 despite making the transition to living alone; from the present data, it is not possible to determine whether this indicates a separation prior to divorce or whether their spouse has moved into residential care, for example. There is a high level of collinearity between marital status and living arrangement trajectory. Moreover, preliminary analyses indicated that the marital status does not significantly add to the explanatory value of the final model (likelihood ratio test: P = 0.14). Therefore, this covariate is excluded from subsequent analyses. The very small number of respondents who divorced between t0 and t1 limits the scope of the analysis relating to pathways into living alone; however, it is still possible to distinguish those who moved from living with a partner to living alone from those who moved from living with children to living alone.

Table 1.

Distribution, mean age and marital status at t1 according to living arrangements among men and women aged 65 or older at t0

| Living arrangements | n | % | Mean age at t0 | % Widowed at t1 | % Divorced/separated at t1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Men | |||||

| Consistently with partner | 1,393 | 70.3 | 67.9 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Consistently with children | 36 | 1.4 | 71.1 | 87.5 | 12.5 |

| Consistently alone | 390 | 16.4 | 72.1 | 50.5 | 21.3 |

| With partner to alone | 160 | 11.2 | 76.8 | 84.8 | 2.9 |

| With children to alone | 12 | 0.7 | 79.3 | 65.6 | 34.4 |

| Total | 1,991 | 100.0 | 69.7 | 18.0 | 4.0 |

| Women | |||||

| Consistently with partner | 1,010 | 37.8 | 66.9 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Consistently with children | 164 | 6.1 | 72.7 | 88.2 | 10.7 |

| Consistently alone | 1,119 | 40.2 | 73.3 | 73.0 | 11.4 |

| With partner to alone | 264 | 14.1 | 74.8 | 91.5 | 2.7 |

| With children to alone | 39 | 1.8 | 74.0 | 86.2 | 9.4 |

| Total | 2,596 | 100.0 | 71.0 | 47.6 | 5.7 |

Statistical model

The results from the nested logistic regression models (Table 2) show that women are significantly more likely to be classified as a case than men and that the risk of psychological distress increases with age. A likelihood ratio test confirms that the key interaction between time and living arrangements adds significant explanatory value to the model (P < 0.001). In the final model (Model 3), those who are living consistently alone or consistently with children do not have significantly higher odds for being classified as a GHQ-12 case than those who are consistently partnered. A large, positive and highly significant interaction is observed between the partnered to living alone trajectory and time-point t1 (odds ratio = 6.2). Additional analysis confirmed that this is also statistically significant when consistently alone is used as the reference group. However, by t3 this interaction has become negative, and by t4 the risk of psychological distress is now significantly lower than at baseline (t0). Those who change from living with a child at t0 to living alone at t1 have the highest probability of being a GHQ-12 case at t0 (with an odds ratio of 3.7 compared with those who are consistently partnered). However, at t1, this probability has fallen to a level similar to those who are consistently partnered. As expected, psychological distress shows a strong, positive association with poor financial circumstances (including pension availability), the presence of health-related limitations to daily activities and low levels of social support. However, the addition of these covariates does not significantly alter the relationship between living arrangement trajectory and time-dependent GHQ-12 caseness.

Table 2.

Odds ratios (95% CIs) for GHQ-12 caseness

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | |||

| Male | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Female | 2.16 (1.77–2.62)*** | 2.05 (1.72–2.45)*** | 1.96 (1.64–2.35)*** |

| Age group | |||

| 65–69 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| 70–74 | 1.13 (0.96–1.33) | 1.05 (0.89–1.24) | 1.01 (0.86–1.19) |

| 71–75 | 1.83 (1.48–2.27)*** | 1.53 (1.25–1.88)*** | 1.52 (1.24–1.86)*** |

| 80+ | 2.22 (1.74–2.84)*** | 1.65 (1.31–2.08)*** | 1.70 (1.35–2.13)*** |

| Living arrangements | |||

| Consistently partnered | 1.00 | ||

| Consistently with children | 1.50 (0.83–2.73) | 1.18 (0.66–2.09) | 1.15 (0.65–2.03) |

| Consistently alone | 1.20 (0.90–1.61) | 1.14 (0.87–1.51) | 1.08 (0.81–1.43) |

| Partnered to alone | 2.86 (1.88–4.37)*** | 2.84 (1.91–4.23)*** | 2.97 (2.00–4.41)*** |

| With children to alone | 7.26 (2.5–21.06)*** | 3.77 (1.37–10.38)* | 3.7 (1.35–10.13)* |

| Time | |||

| t0 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| t1 | 0.90 (0.73–1.11) | 0.92 (0.74–1.13) | 0.95 (0.77–1.18) |

| t2 | 1.08 (0.87–1.34) | 1.03 (0.83–1.29) | 1.06 (0.85–1.32) |

| t3 | 1.11 (0.88–1.39) | 1.08 (0.86–1.37) | 1.12 (0.89–1.41) |

| t4 | 1.15 (0.90–1.46) | 1.13 (0.88–1.43) | 1.18 (0.93–1.51) |

| t5 | 1.17 (0.89–1.55) | 1.09 (0.82–1.44) | 1.17 (0.89–1.55) |

| Living arr*Time | |||

| Children*t1 | 1.40 (0.72–2.72) | 1.36 (0.70–2.65) | 1.33 (0.68–2.59) |

| Children*t2 | 0.82 (0.41–1.65) | 0.79 (0.39–1.61) | 0.79 (0.39–1.60) |

| Children*t3 | 0.92 (0.44–1.93) | 0.81 (0.38–1.73) | 0.83 (0.39–1.77) |

| Children*t4 | 1.42 (0.67–3.03) | 1.57 (0.73–3.36) | 1.61 (0.75–3.46) |

| Children*t5 | 1.49 (0.67–3.32) | 1.54 (0.69–3.48) | 1.59 (0.71–3.57) |

| Alone*t1 | 1.19 (0.87–1.64) | 1.20 (0.88–1.66) | 1.18 (0.86–1.62) |

| Alone*t2 | 0.85 (0.61–1.19) | 0.83 (0.59–1.16) | 0.84 (0.60–1.17) |

| Alone*t3 | 0.84 (0.59–1.18) | 0.77 (0.55–1.10) | 0.79 (0.56–1.12) |

| Alone*t4 | 0.96 (0.67–1.37) | 0.90 (0.63–1.29) | 0.95 (0.66–1.36) |

| Alone*t5 | 0.69 (0.46–1.03) | 0.66 (0.44–0.98)* | 0.70 (0.47–1.04) |

| Partnered-alone*t1 | 6.76 (4.27–10.7)*** | 6.96 (4.41–10.97)*** | 6.18 (3.91–9.76)*** |

| Partnered-alone*t2 | 0.87 (0.54–1.39) | 1.00 (0.63–1.61) | 1.01 (0.63–1.62) |

| Partnered-alone*t3 | 0.60 (0.36–1.00) | 0.62 (0.37–1.03) | 0.64 (0.38–1.07) |

| Partnered-alone*t4 | 0.45 (0.26–0.77)** | 0.42 (0.25–0.73)** | 0.44 (0.25–0.75)** |

| Partnered-alone*t5 | 0.43 (0.24–0.77)** | 0.42 (0.23–0.77)** | 0.44 (0.24–0.80)** |

| Children-alone*t1 | 0.20 (0.05–0.74)* | 0.29 (0.08–1.07) | 0.27 (0.07–1.00) |

| Children-alone*t2 | 0.34 (0.09–1.20) | 0.41 (0.11–1.46) | 0.43 (0.12–1.52) |

| Children-alone*t3 | 0.24 (0.06–1.01) | 0.36 (0.09–1.53) | 0.34 (0.08–1.43) |

| Children-alone*t4 | 0.15 (0.03–0.68)* | 0.22 (0.05–1.04) | 0.21 (0.05–0.98)* |

| Children-alone*t5 | 0.08 (0.01–0.53)** | 0.12 (0.02–0.82)* | 0.11 (0.02–0.76)* |

| Social support | |||

| Low | 1.00 | 1.00 | |

| High | 0.81 (0.72–0.91)*** | 0.81 (0.72–0.91)*** | |

| Health limits daily activities | |||

| No | 1.00 | 1.00 | |

| Yes | 5.04 (4.45–5.71)*** | 4.88 (4.32–5.52)*** | |

| Financial circumstances | |||

| Doing OK | 1.00 | ||

| Struggling | 1.65 (1.45–1.88)*** | ||

| Change in financial circumstances | |||

| Same/better | 1.00 | ||

| Worse | 1.53 (1.33–1.74)*** | ||

| Housing tenure | |||

| Owner-occupier | 1.00 | ||

| Social housing | 1.13 (0.94–1.35) | ||

| Private renting | 1.05 (0.77–1.42) | ||

| Pension income | |||

| No additional pension | 1.00 | ||

| Private or occupational pension | 0.84 (0.72–0.98)* | ||

*P < 0.05.

**P < 0.01.

***P < 0.001.

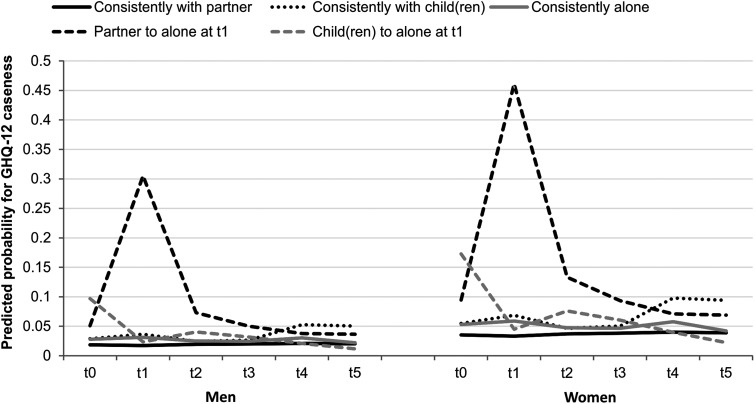

Figure 1 shows the predicted probabilities for GHQ-12 caseness at each time-point according to living arrangement trajectory, based on the coefficients from Model 3, with all other covariates held at baseline. The chart shows that for those moving from living with a partner to living alone, the probability of GHQ-12 caseness is already slightly elevated at t0, but increases substantially at t1. A year later at t2, the probability has fallen substantially, by t3 has returned to the level observed at t0 and by t4 has fallen below the value at t0. The trajectories of GHQ-12 in all the stable comparison groups all remain relatively flat, with no significant changes over time.

Figure 1.

Predicted probabilities for GHQ-12 caseness by living arrangements and time.

Discussion

These analyses suggest that living alone in later life is not, in itself, associated with a significantly increased risk of psychological distress. However, the transition to living alone can have a significant impact on the odds that an individual will be classified as a case based on the GHQ-12. When GHQ-12 was measured within a year of making the transition from living with a partner to living alone—primarily via widowhood—the odds for being classified as a case increased substantially. However, just 1 year later, this risk had declined, and by the third year of follow-up, was no longer statistically significant. The risk of caseness was also slightly increased in the year prior to this transition to living alone, suggesting stress associated with caring for a sick and/or dependent spouse prior to bereavement or a move to institutional care.

The findings reinforce previous research demonstrating the role of socio-economic circumstances in determining mental health [19, 24, 25], and also confirm the role of social support in promoting or maintaining good mental health [26]. However, none of the covariates entered into our models showed any substantial impact on the relationship between psychological distress and the transition to living alone from partnership. Supporting previous research from the UK and the USA, this provides further evidence for the ‘crisis’ model, suggesting that it is primarily the emotional stress of bereavement that leads to an increase in psychological distress and not any associated changes in material resource, for example, and that widowhood has only a short-term negative effect on mental health [15, 17, 27].

Unexpectedly, the results indicated that making the transition to living alone after living with at least one child (and without a partner) had a positive impact on mental health, with a significant decrease in the odds for psychological distress following this transition. However, such respondents also had a high risk of psychological distress in the year immediately prior to the transition (t0), and at t1 this simply fell to a level similar to the groups in stable living arrangements. Those living consistently with children were no more likely to be a GHQ-12 case than those who were consistently partnered or those living consistently alone. We can only speculate as to the explanation for this finding, but it is possible that those who make the transition to living alone after living with children do so because the living arrangement becomes stressful for some reason, which would account for the elevated probability of GHQ-12 caseness at t0. This association is also likely to be sensitive to context—for example, in cultures where family interdependence is valued, such as in Spain, co-residence with children in older age has been positively associated with good mental health [28].

The present analysis draws strength from its longitudinal design and from the relatively large sample size achieved by pooling the 18 waves of the BHPS. However, this approach meant that the selection of comparison groups was not straightforward and, for example, produced a bias towards the younger age group as respondents were selected as they entered our target age range of 65 years or older. Nevertheless, it can be argued that this limitation is outweighed by the advantages of being able to analyse this large, longitudinal data set.

In conclusion, the findings presented in this paper demonstrate that living alone is not necessarily associated with an increased risk of psychological distress in later life. Future research and policy decisions should take into account that the relationship between living alone and mental health in later life is dependent on whether and how recently an individual has made the transition to living alone and with whom they were living prior to this transition. It should also seek to identify additional social and material factors that might mediate such relationships. The findings emphasise the need for a longitudinal approach when studying associations between living arrangements and health, given the importance of respondents' location along these trajectories of living arrangements.

Key points.

In this British sample, living consistently alone in later life does not appear to impair mental health.

The transition to living alone has a strong but transient impact on mental health in later life.

This association is highly dependent on the preceding living arrangement.

This association is independent of availability of social support and socio-economic resources.

Given the importance of respondents' location along trajectories of living arrangements, a longitudinal approach is advised.

Conflicts of interest

None declared.

Funding

This research is funded by ESRC Grant number RES-625-28-0001. The Centre for Population Change is a joint initiative between the University of Southampton and a consortium of Scottish Universities in partnership with the Office for National Statistics (ONS) and National Records of Scotland (NRS). The findings, interpretations and conclusions expressed in this paper are entirely those of the authors and should not be attributed in any manner to ONS or NRS.

Acknowledgements

The BHPS is carried out by the Institute for Social and Economic Research at the University of Essex. Access to the data is provided by the UK Data Archive. Neither the original data creators, depositors or funders bear responsibility for the further analysis or interpretation of the data presented in this study. The authors thank Prof. Peter W. Smith and Ann Berrington for their statistical advice. The paper also benefited from constructive comments and advice from two anonymous reviewers. Their input is gratefully acknowledged.

References

- 1.Gaymu J, Ekamper P, Beets G. Future trends in health and marital status: effects on the structure of living arrangements of older Europeans in 2030. Eur J Ageing. 2008;5:5–17. doi: 10.1007/s10433-008-0072-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Evandrou M, Falkingham J, Rake K, Scott A. The dynamics of living arrangements in later life: evidence from the British household panel survey. Popul Trends. 2001;105:37–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Savikko N, Routasalo P, Tilvis RS, Strandberg TE, Pitkala KH. Predictors and subjective causes of loneliness in an aged population. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2005;41:223–33. doi: 10.1016/j.archger.2005.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Victor CR, Scambler SJ, Bowling ANN, Bond J. The prevalence of, and risk factors for, loneliness in later life: a survey of older people in Great Britain. Ageing Soc. 2005;25:357–75. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sundstrom G, Fransson E, Malmberg B, Davey A. Loneliness among older Europeans. Eur J Ageing. 2009;6:267–75. doi: 10.1007/s10433-009-0134-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.De Jong Gierveld J, van Tilburg T, Dykstra PA. Loneliness and social isolation. In: Vangelisti A, Perlman D, editors. Cambridge Handbook of Personal Relationships. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2006. pp. 485–500. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Russell D, Taylor J. Living alone and depressive symptoms: the influence of gender, physical disability, and social support among hispanic and non-hispanic older adults. J Gerontol B. 2009;64B:95–104. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbn002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Harris EC, Barraclough B. Excess mortality of mental disorder. Br J Psychiatry. 1998;173:11–53. doi: 10.1192/bjp.173.1.11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schulz R, Drayer RA, Rollman BL. Depression as a risk factor for non-suicide mortality in the elderly. Biol Psychiatry. 2002;52:205–25. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(02)01423-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Huppert FA, Whittington JE. Symptoms of psychological distress predict 7-year mortality. Psychol Med. 1995;25:1073–86. doi: 10.1017/s0033291700037569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Joukamaa M, Heliûvaara M, Knekt P, Aromaa A, Raitasalo R, Lehtinen V. Mental disorders and cause-specific mortality. Br J Psychiatry. 2001;179:498–502. doi: 10.1192/bjp.179.6.498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.House A, Knapp P, Bamford J, Vail A. Mortality at 12 and 24 months after stroke may be associated with depressive symptoms at 1 month. Stroke. 2001;32:696–701. doi: 10.1161/01.str.32.3.696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Martikainen P, Nihtila E, Moustgaard H. The effects of socioeconomic status and health on transitions in living arrangements and mortality: a longitudinal analysis of elderly Finnish men and women from 1997 to 2002. J Gerontol B. 2008;63:S99–S109. doi: 10.1093/geronb/63.2.s99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wilmoth JM. Living arrangement transitions among america's older adults. Gerontologist. 1998;38:434–44. doi: 10.1093/geront/38.4.434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wade TJ, Pevalin DJ. Marital transitions and mental health. J Health Social Behav. 2004;45:155–70. doi: 10.1177/002214650404500203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Williams K, Umberson D. Marital status, marital transitions, and health: a gendered life course perspective. J Health Soc Behav. 2004;45:81–98. doi: 10.1177/002214650404500106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wilcox S, Evenson KR, Aragaki A, Wassertheil-Smoller S, Mouton CP, Loevinger BL. The effects of widowhood on physical and mental health, health behaviors, and health outcomes: The Women's Health Initiative. Health Psychol. 2003;22:513. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.22.5.513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kawachi I, Berkman L. Social ties and mental health. J Urban Health. 2001;78:458–67. doi: 10.1093/jurban/78.3.458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wiggins RD, Schofield P, Sacker A, Head J, Bartley M. Social position and minor psychiatric morbidity over time in the British Household Panel Survey 1991–1998. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2004;58:779–87. doi: 10.1136/jech.2003.015958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Goldberg DP, Williams P. A User's Guide to the General Health Questionnaire. Windsor: NFER-Nelson; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bowling A, Gabriel Z. An integrational model of quality of life in older age. Results from the ESRC/MRC HSRC quality of life survey in Britain. Soc Ind Res. 2004;69:1–36. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pevalin DJ. Multiple applications of the GHQ-12 in a general population sample: an investigation of long-term retest effects. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatric Epidemiol. 2000;35:508–12. doi: 10.1007/s001270050272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Goldberg DP, Oldehinkel T, Ormel J. Why GHQ threshold varies from one place to another. Psychol Med. 1998;28:915–21. doi: 10.1017/s0033291798006874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Taylor MP, Jenkins SP, Sacker A. Financial capability and psychological health. J Econ Psychol. 2011;32:710–23. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sareen J, Afifi TO, McMillan KA, Asmundson GJG. Relationship between household income and mental disorders: findings from a population-based longitudinal study. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2011;68:419. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2011.15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Netuveli G, Wiggins RD, Montgomery SM, Hildon Z, Blane D. Mental health and resilience at older ages: bouncing back after adversity in the British Household Panel Survey. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2008;62:987–91. doi: 10.1136/jech.2007.069138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mastekaasa A. The subjective well-being of the previously married: the importance of unmarried cohabitation and time since widowhood or divorce. Soc Force. 1994;73:665–92. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zunzunegui MV, Beland F, Otero A. Support from children, living arrangements, self-rated health and depressive symptoms of older people in Spain. Int J Epidemiol. 2001;30:1090–9. doi: 10.1093/ije/30.5.1090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]