Abstract

Goal:

Polypharmacy and drug-related problems (DRPs) have been shown to prevail in hospitalized patients. We evaluated the prevalence of polypharmacy; and investigated relationship between polypharmacy and: symptoms of DRPs, number of drugs and OTC, index of cumulative morbidity, length of exposure to polypharmacy and the number of days of hospital stay among hospitalized patients.

Methodology:

A study was performed in Pharmacies „Eufarm Edal“ Tuzla from 2010 to 2011. Polypharmacy was defined as using ≥ 3 drugs. The total study sample of 226 examiners were interviewed with special constructed questionnaires about DRPs. Experimental study group consisted of hospital patients with polypharmacy (n=166) and control group hospital patients without polypharmacy (n=60). Mann-Whitney test was used to test for significant self-reported symptom differences between groups and cross sectional subgroups, t- test and χ2- test for age, gender and treatment data in hospital.

Results:

The prevalence of polypharmacy was 74% among 226 hospitalized patients. The vulnerable age subgroup of hospitalized patients was men and hospitalized patients aged from 46 to 50 years (not geriatric patients). The prevalence of index of cumulative morbidity was 65%. The most common exposures varied by patient age and by hospital type, with various antibiotics, antidepressants, analgesics, sedatives, antihypertensives, flixotide, ranitidine and others. The prevalence of exposure to OTC and self- treatment was 80%. The prevalence of symptoms of drug-related problems were significantly differed among patients of experimental in relationship of control study group patients (P<0.001).

Conclusion:

In addition to helping to resolve the above mentioned issues, the results from this study could provide baseline information quantifying the problem of drug- related problems among hospitalized patients receiving polypharmacy and contribute to the formulation and implementation of risk management strategies for pharmacists and physicians in primary care health.

Key words: polypharmacy, hospitalized patients, index of cumulative, primary pharmaceutical care.

1. INTRODUCTION

The use of multiple medications increases the possibility of adverse reactions to drugs, increases the risk of hospitalization and medical errors caused by drugs (1). Today there is also a growing trend of symptomatic patients self-healing with non-prescription OTC drugs that are regularly available in pharmacies and complicate the problem (2). A large number of studies on this topic were conducted for more than 10 or 20 years and it remains unclear whether the results and insights learned from these studies had any effect on changes in clinical practice (3, 4, 5, 6). Often, the use of a large number of drugs is associated with their unknown interactions and adverse reactions that are prevalent in hospitalized patients (7, 8, 9, 10). Treating patients in a hospital setting with more than four drugs can cause major irreversible damage and lead to reducing functional and working ability (8, 9). The most common adverse outcomes of polypharmacy use are increased incidence of side effects and drug-drug interactions, and an increase in total medical costs (10). Side effects of medications, according to some epidemiological indicators represent the third most common disease after cardiovascular diseases and cancer (11). The solution to this problem is of great importance in the practice of doctors and pharmacists in primary care (5, 6). Symptoms and signs of side effects of polypharmacy may be hidden symptoms of other diseases, and sometimes it means completely new and distinctive.

Some signs and symptoms of polypharmacy use include: fatigue, drowsiness and decreased alertness, constipation, diarrhea or incontinence of urine, loss of appetite, impaired concentration (intermittent or constant), falls, depression or lack of interest in usual activities, fatigue, tremor, anxiety and irritability, dizziness, decreased libido, decreased cognitive ability, skin rash or even hallucinations (9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16).

In addition to adverse clinical consequences for patients, polypharmacy and the development of adverse effects represent a significant financial burden on the health system. In a study conducted in France from 1996 to 1997 the analysis showed an annual increase in consumer cost of procurement of drugs at the University Hospital in the amount of 3.85 million euros per year (17). Thus, reducing the use of unnecessary medications and avoid polypharmacy would be significant economic savings in healthcare costs.

The survey aims to determine the frequency of polypharmacy by number of prescribed medications, OTC prevalence, morbidity, and the index of cumulative comorbidity of subjects, number of days of hospitalization and therapy duration. Comparison of the existence of symptoms are related to adverse drug interactions in conditions of polypharmacy in the experimental group compared to controls to identify signs of side effects.

2. METHODS

The study was conducted during 2010–2011 in pharmacies “Eufarm Edal” Tuzla (to gather the desired sample). Materials for research at the initial stage were the data from hospital discharge lists (individual and demographic data, treatment data, the number of pharmacological effects of drugs and hospitalization duration). To support reaching the objectives of the research a self-completing questionnaire about symptoms, potential side effects of medication,was used and it was created specifically for this study (9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16).

At this stage of research in surveyed respondents were analyzed the therapeutic effect of the interaction of combining drugs (polytherapy) or a negative therapeutic effect manifested symptoms and signs of adverse effects of polytherapy. Attention that was paid to symptoms and signs of ill condition of the patient (morbidity) would not be attributed to adverse drug reactions.

In the study we followed the principles of toxicology, taking into account the length of the polytherapy exposure: Acute exposure entailed the use of the drug last month, and more chronic after 6 months.

2.1. Respondents

The study included a voluntary agreement of 304 adults, of both sexes, aged 14-60 years. Including factors for the selection of respondents was that their illness required hospital drug treatment according to clinical procedures and that they were not chronic alcoholics. The total sample included 78 subjects who did not meet inclusive factors. For the patients in this group, hospital treatment involved emergency diagnostic procedures, emergency surgical procedures, the transfer from one hospital department to another with unresolved medical status and choice of drugs for treatment. None of the patients in this group had proposed drug treatment (number of medications = 0), but came to the pharmacy to seek advice or buy OTC drugs. Therefore, the total sample of respondents was 226. From the total sample was formed experimental (studied) group, which consisted of 166 patients who were treated with 3 or more medications daily, while the control group consisted of patients who were in treatment using the 0-2 drugs daily. Subjects in the control group (60 of them) were hospitalized for treatment of acute exacerbations of chronic diseases, acute infections, or surgical and physical treatment. Control and research groups did not diff er signifi cantly by gender (χ2=0.001, P=0.980) and age (t-test=1.581, P = 0.119, 95% CI: 0.756-6.456), and body mass index category (BMI, non-parametric Mann Whitney test, z =–0.60, P = 0.548).

2.2. Definitions

Polytherapy is defi ned as daily consumption of 3 or more drugs. Polypharmacy (Lat. polypragmasia) is irrational and inappropriate provision of more therapeutic preparations for which there is no evidence of usefulness in the treatment (2-6). The index of cumulative morbidity represents the value that determines the size of the chronic morbidity of patients with the ≥ 4 diseases diagnosed (2). Th e non-prescription pharmacy products or OTC (over the counter) medicines are of natural origin, medical devices and drugs that are assumed to have a low degree of toxicity and high therapeutic range (3-5). So it can be used for the well-known indications and to serve for self-treatment. OTC products include antirheumatics drugs, vitamins and minerals, analgesics, antihistaminic, laxatives, and some beauty products that are being sold only in pharmacies (most commonly used are analgesics).

2.3. Statistical analysis

Standard tests of descriptive statistics were used with measuring the central tendency and dispersion. Quantitative variables were tested by Student’s t-test if they were normally distributed or Mann-Whitney-test in case they were distributed asymmetrically. Qualitative variables were tested by chi-square test with continuity correction. All tests were leveled with the level of statistical significance of 95% (p <0.05).

3. RESULTS

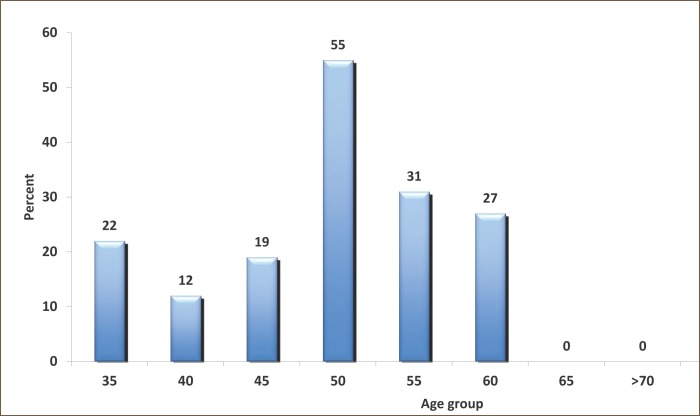

The hospital conditions polypharmacy prevalence was 74% (n=166 respondents out of 226). The subjects of the experimental group (n = 166) had an average age of 46.36 ± 9:53 (SD) years. Most of them belong to the subgroup aged 50-55 years (n=81, 49%, Figure 1). Most patients were treated at the Clinic of Pulmonary Diseases and Tuberculosis (40%) and Psychiatric Clinic (28%). In the experimental group polypharmacy was more frequent in men (91 out of 166) than in women, and there was no statistically significant difference. The subjects of the experimental group were hospitalized for total of 3367 days and treated with a total of 1018 drugs. They were statistically more significant: diagnosed chronic diseases, the number of days of hospitalization, duration of exposure (drug use) and were more using OTC (P=0.001).

Figure 1.

Distribution of the experimental group respondents according to age subgroups (n=166).

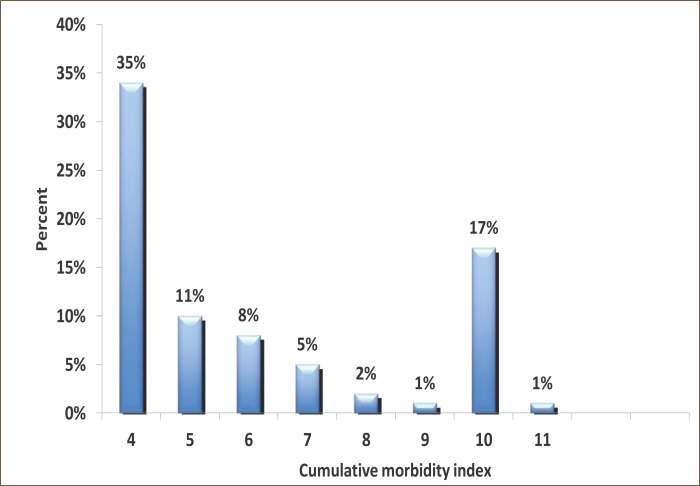

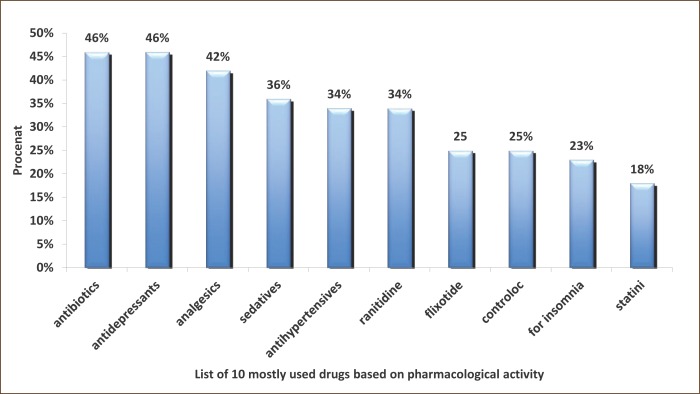

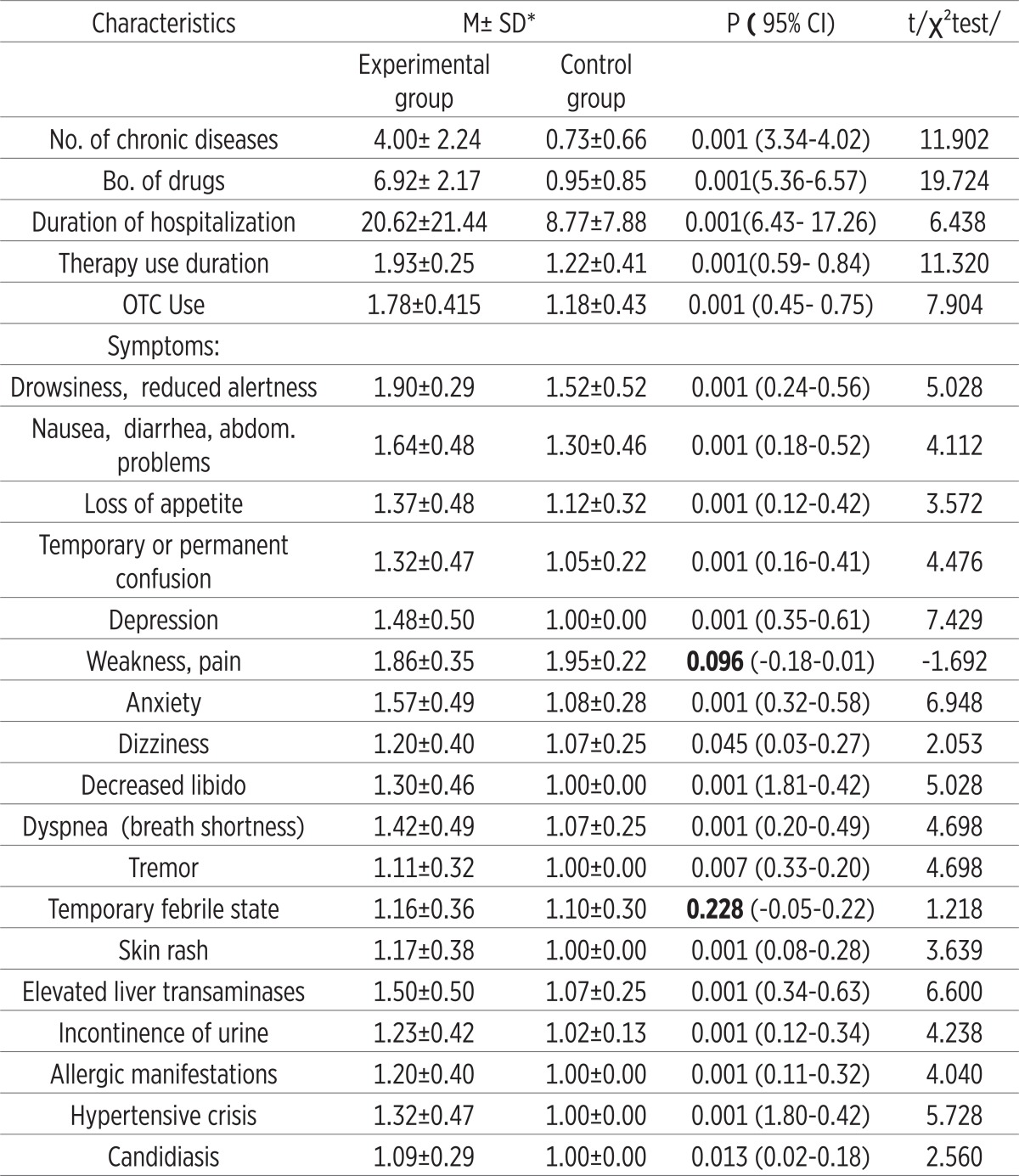

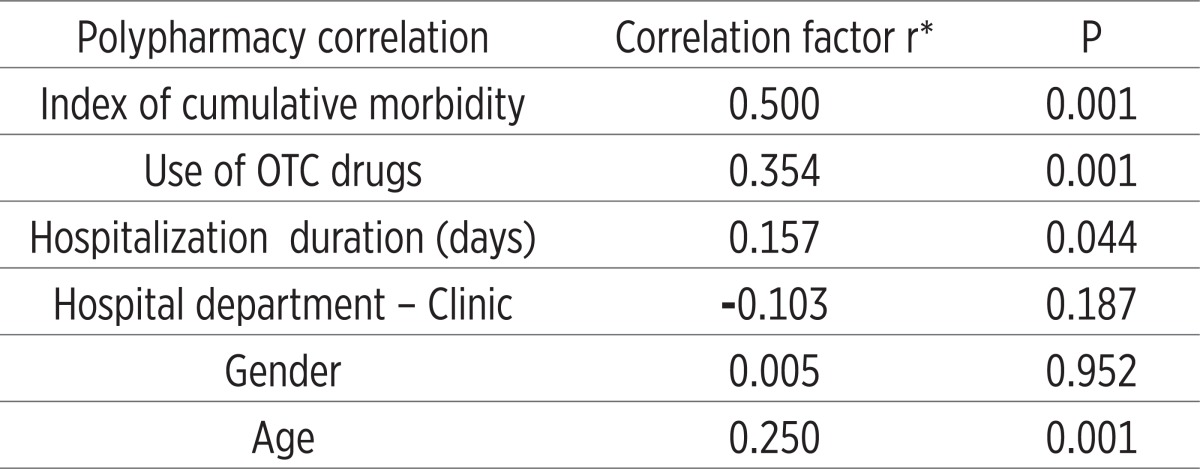

Almost all analyzed symptoms that may be associated with adverse reactions to polypharmacy because they are signifi cantly more represented in patients with polypharmacy (the experimental group, P<0.05-P <0.001). An exception are the symptoms of weakness and pain perception (P=0.096) and a temporary febrile conditions (P=0.228). Th ese two symptoms can be attributed to primary diseases/morbidity of patients (Table 1). Nearly all, 92% (n=152 out of 166) in the experimental group were exposed to long-term polypharmacy (> 6 months). Most common symptoms are insomnia, depression and anxiety (47%), dyspnea and fatigue (36%), allergy (20%), gastric discomfort 7%, 7% of vertigo and feeling of fatigue 3.6%. Inadequate treatment was presented by the following new syndromes: emergence of transient ischemic attacks or TIA’s (8%), resistance or tolerance to drugs (13%) and erosive gastritis (4%), impaired liver enzyme levels (2%) and incontinence of urine (1%) (Results not shown). Number of chronic diseases, an increased number of medications used, number of days of hospital treatment, length of use and application of OTC drugs were statistically significantly more represented in the experimental group (P = 0.001), in some patients who are treated with 1-2 drugs (Table 1). The index reveals the cumulative morbidity highest prevalence of 35% in the experimental group who have up to four chronic diseases in the experimental group. Twenty-four percent have 5-7 diseases and 10 diseases have 28 (17%) patients (Figure 2). There is a presumption that in the subgroup with 10 and 11 (1%), symptoms of disease are hidden objective undiagnosed illness or disease that might result in DRP conditions of polypharmacy. The most common morbidity is respiratory diseases, psychiatric (predominance of depression) and cardiovascular disease (results not shown). The most common application of the pharmacological actions of drugs as antibiotics, antidepressants and analgesics (almost half of all respondents use these drugs) (Figure 3). Most commonly used drugs are antibiotics as Impinem, Vankomycin, Ceftriaxon, Klaritromycin, Gentomycin, Vibramycin or Doxicilin and Citeral. Yet the most common application of the non-prescription drugs (OTC) with a prevalence of 80% which represents a high trend of self-healing among patients. There is a significant prevalence of respondents who frequently use analgesics in the treatment (69%). These medicines are available in pharmacies as OTC preparations, according to current knowledge can cause side effects. The most common application is of the analgesic as Tramadol, Voltaren, Indocid, Difen, Ibuprofen, Paracetamol and Bosalgin. Polypharmacy was significantly associated (statistically significant correlation) with a cumulative index of morbidity, use of OTC, the number of days of hospitalization and with age (Table 2). The most frequent combinations in order to reinforce the effect of pharmacological therapy are 3-4 psychotropic medication with antidepressants, 2-4 antihypertensive drugs, two for the prophylaxis and treatment of 4 for antitubercular drug, and occasionally 2-5 antibiotics in hospital conditions (data not shown).

Table 1.

Distribution of morbidity characteristics and hospitalization: the number of chronic diseases, number of medications, hospitalization duration, and use of OTC and symptoms that may be related to side effects in the polypharmacy groups. *M±SD- mean± standard deviation

|

Figure 2.

Distribution of respondents according to the index of cumulative mortality in the experimental group.

Figure 3.

The list of 10 commonly used drugs on pharmacological activity in the total sample (N=226).

Table 2.

Correlation between polypharmacy with other important characteristics of treatment and individual characteristics of subjects in experimental group (n=166)

|

4. DISCUSSION

Although within the therapeutic process undoubted primary role should have a doctor and a pharmacist advice, today patients are looking for something that works quickly and efficiently (18). It is not easy to resist the “therapeutic Evangelism,” which often comes from non-critical circles of experts. There is no justification to treat every symptom of a sick situation, as there is no justification to choose drugs with similar mechanism of action (4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11).

Polypharmacy is most common in people with multiple chronic health disorders and in the elderly. Thus an important risk factor for polypharmacy is old age (3, 4, 5, 6, 7). Our findings are consistent with the results of other authors. The most vulnerable group of patients is younger than 55 years, which makes the problem more complex and DRP in our country compared to other countries (4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11). The prevalence of polypharmacy in our study of 74%, which again makes the problem bigger to us in relation to the United States or other Western countries where the prevalence for hospital treatment ranges from 47%–52% (19, 20, 21).

The most commonly prescribed medications are for gastrointestinal diseases, cardiovascular diseases, analgesics, antirheumatics drugs and antidepressants. The use of these drugs increases with age (22, 23, 24). Approximately 10-14% hospitalized geriatric patients have side effects (7). Sometimes occurs an oversight that the classic side effects are attributed to unidentified disease and a new drug is prescribed (25). Because of unnecessary new therapy (introducing the new drug treatment), the patient is at risk of new adverse reactions (26, 27, 28). This is particularly common in our country due to the constant changes in the essential drugs list. Sometimes it is unfortunate that the patient suffers from side effects for months, which gradually leads to a decrease in their functional abilities (29). Similar situation is with interactions of drugs. There was a statistically significant relationship between the number of drugs used by the women and increased risk of side effects (7, 19, 20, 21). Number of interactions increases with the number of drugs (30, 31), which is consistent with the results of our study. The growing trend of self-healing in the world in recent years is going on in our country as well (18). Selling non-prescription drugs (OTC) should be under continuous expert supervision.

5. CONCLUSION

Polypharmacy has a very high prevalence among hospitalized patients in our country and represents an urgent public health issue that should be addressed. It is not only necessary to preserve the health and safety of the patients, but also provide a rationalization of the economic costs of treatment. Polypharmacy and OTC drugs should be under continuous expert surveillance. The task of pharmacists is not only the issue of drugs, but also advice and consideration of other medications that patients use. Special attention should be given to elderly patients (30, 31) and patients treated in hospitals, as shown by the results of our study. For pharmacists, it is important to continually educate, but also to have access to complete patient records, so we could look at all of the medications that may be given to the patient. The solution to this problem is of great importance in practice of primary pharmaceutical care.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

none declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Pranjić N. Medical error- professional liability for malpractice in Bosnia and Herzegovina. Liječ Vjesn. 2009;131(7-8):229–232. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alić A, Pranjić N, Ramić E. Polypharmacy and decreased cognitive abilities in elderly patients. Med Arh. 2011;65(2):102–105. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hoigné R, Lawson DH, Weber E. Risk factors for adverse drug reactions - epidemiological approaches. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 1990;39:321–325. doi: 10.1007/BF00315403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hurwitz N. Predisposing factors in adverse reactions to drugs. BMJ. 1969;1:536–539. doi: 10.1136/bmj.1.5643.536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bergman U, Wiholm BE. Drug-related problems causing admission to a medical clinic. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 1981a;20:193–200. doi: 10.1007/BF00544597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bergman U, Wiholm BE. Patient medication on admission to a medical clinic. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 1981b;20:185–191. doi: 10.1007/BF00544596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Koh Y, Moldeen Kutty FB, Chuen L S. Drug-related problems in hospitalized patients on polypharmacy: the influence of age and gender. Ther Clin Risk Manag. 2005;1(1):39–48. doi: 10.2147/tcrm.1.1.39.53597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Beijer HJM, De Blaey CJ. Hospitalisations caused by adverse drug reactions (ADR): a meta-analysis of observational studies. Pharm World Sci. 2002;24:46–54. doi: 10.1023/a:1015570104121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brennan TA, Leape LL, Laird NM, et al. Incidence of adverse drug events and negligence in hospitalized patients: results of Harvard Medical Practice Study I. N Engl J Med. 1991;324:370–376. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199102073240604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Classen DC, Pestotnik SL, Evans RS, et al. Adverse drug events in hospitalized patients. Excess length of stay, extra costs, and attributable mortality. JAMA. 1997;277:301–306. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Colt HG, Shapiro AP. Drug induced illness as a cause for admission to a community hospital. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1989;37:323–326. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1989.tb05498.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fattinger K, Roos M, Vergères P, et al. Epidemiology of drug exposure and adverse drug reactions in two Swiss departments of internal medicine. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2000;49:158–167. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2125.2000.00132.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Green CF, Mottram DR, Rowe PH, et al. Adverse drug reactions as a cause of admission to an acute medical assessment unit: a pilot study. J Clin Pharm Therap. 2000;25:355–361. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2710.2000.00298.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nobili A, Licata G, Salerno F, et al. Polypharmacy, length of hospital stay, and in-hospital mortality among elderly patients in internal medicine wards. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2011;67(5):507–519. doi: 10.1007/s00228-010-0977-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Feudtner C, Dai D, Hexem KR, et al. Prevalence of Polypharmacy Exposure Among Hospitalized Children in the United States. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2012;166(1):9–16. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2011.161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chrischilles EA, Segar ET, Wallace RB. Self-reported adverse drug reactions and related resource use. Ann Intern Med. 1992;117:634–640. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-117-8-634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lagnaoui R, Moore N, Fach J, et al. Adverse drug reactions in a department of systemic diseases-oriented internal medicine: prevalence, incidence, direct costs and avoidability. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2000;56:181–186. doi: 10.1007/s002280050738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hepler CD, Strand LM. Opportunities and responsibilities in pharmaceutical care. Am J Hosp Pharm. 1990;47:533–543. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nobili A, Licata G, Salerno F, Pasina L, et al. Polypharmacy, length of hospital stay, and in-hospital mortality among elderly patients in internal medicine wards. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2011;67(5):507–519. doi: 10.1007/s00228-010-0977-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Viktil KK, Blix HS, Morger TA, et al. Polypharmacy as commonly defined is an indicator of limited value in the assessment of drug related problems. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2007;63(2):187–195. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.2006.02744.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Feudtner C, Dai D, Hexem KR, Luan X, Metjian TA. Prevalence of Polypharmacy Exposure Among Hospitalized Children in the United States. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2012;166(1):9–16. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2011.161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gurwitz JH, Avorn J. The ambiguous relation between aging and adverse drug reactions. A Intern Med. 1991;114:956–966. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-114-11-956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hanlon JT, Schmader KE, Koronkowski MJ, et al. Adverse drug events in high risk older outpatients. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1997;45:945–948. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1997.tb02964.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lindquist M, Vigibase M. The WHO Global ICSR Database System: Basic facts. Drug Inform J. 2008;42:409–419. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Moynihan R, Heath I, Henry D. Selling sickness: the pharmaceutical industry and disease mongering. BMJ. 2002;324:886–891. doi: 10.1136/bmj.324.7342.886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pranjić N. Social Pharmacy. Tuzla: Medical faculty University of Tuzla, PrintCOM; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rahman SZ, Khan RA. Environmental pharmacology: A new discipline. Indian J Pharmacol. 2006;38(4):229–230. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Van Mil. Pharmacy care, the future of pharmacy-theory, research and practice. Univeristy of Groningen; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Walsh JME, Pignone M. Drug treatment of hyperlipidemia in women. JAMA. 2004;291:2243–2252. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.18.2243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Westin S, Heath I. Tresholds od normal blood pressure and serum cholesterol. BMJ. 2005;330:1461–1462. doi: 10.1136/bmj.330.7506.1461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zarowitz BJ, Stebelsky LA, Muma BK, et al. Reduction of high risk of polypharmacy drug combinations in patients in a managed care setting. Pharmacotherapy. 2005;25:1636–1645. doi: 10.1592/phco.2005.25.11.1636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]