Abstract

Background:

Increasingly, women in rural areas in Sudan reported to hospital with puerperal infections.

Aims:

This study was design to identify the common pathogens causing puerperal infections and their susceptibility to current antibiotics.

Subjects and methods:

We prospectively studied 170 women from January, 2011 through January 2012 attended Hussein Mustafa Hospital for Obstetrics and Gynecology at Gadarif State, Sudan. We included patients if they met the criteria proposed by the WHO for definition of maternal sepsis. Blood was collected on existing infection guidelines for clean practice and equipments.

Results:

Out of the 170 samples, 124 (72.9%) were pathogen-positive samples. Out the 124 positive cases, aerobes were the predominant isolates 77 (62.1 %%) which included Staph.aureus 49 (39.5%), Staph. epidemics 7 (5.6%) and Listeria monocytogenes 21 (16.9%). The anaerobes isolates were Clostridium perfringens 34 (27.4 %) and Entrobactor cloacae 13 (10.5%). Standard biochemical test were for bacterial isolation. Higher rate of infections followed vaginal delivery compared to Cesarean section 121 (97.6%), 3 (2.5%) respectively. All strains of Staph were sensitive to Vancomycin, Gentamicin and Ceftriaxone. C. perfringens were sensitive to Ceftriaxone, Penicillins, Vancomycin and Metronidazole, while E. cloacae were sensitive to Gentamicin and Ceftriaxone.

Conclusion:

Despite the limited resources in the developing countries, treatment based on cultures remains the only solution to reduce maternal morbidity and mortality rates following puerperal infections.

Key words: maternal sepsis, puerperal sepsis, morbidity, mortality, Sudan.

1. INTRODUCTION

Puerperal infection is still a significant cause of morbidity and mortality among women in the developing countries. The Millennium Development Goal 5 (MDG5) of reducing the maternal mortality ratio by 75% between 1990 and 2015 (1) is unlikely to be achieved in Africa, because there was no progress that has been made to achieve such goals. Most of the current strategies in the developing world are focusing on emergency obstetric care. In Sudan, the mortality rate was 1,363 per 100,000 during 1995-1999 and sepsis was found to be the main cause of death in one third of cases. Furthermore, it was the leading cause of maternal mortality during 1985 to 2000 (2). Those who survive may develop serious complications’ as a result of puerperal sepsis such as infertility and chronic pelvic pain (3, 4). It is a common practice in the developing world to give antibiotics empirically. However, treatment based only on symptoms and clinical diagnosis can be misleading, and it can results in serious complications (5, 6). The present study, was conducted to determine the exact pathogenic infections in women with puerperal sepsis, and their susceptibility test to the currently use antimicrobial therapy in a rural hospital, in Sudan.

2. SUBJECTS AND METHODS

This prospective cross-sectional study was conducted at Hussein Mustafa Hospital, department of Obstetrics and Gynecology in Gadarif State, Eastern Sudan, during the period from June 2011 to June 2012. The study was approved by the hospital Ethical committee. Hundred and seventy patients who had puerperal sepsis (WHO definition) were included in this study. Maternal sepsis was defined as infection of the genital tract occurring at any time between the rupture of membranes or labor, and 42 days postpartum in which 2 or more of the following are present: a) Pelvic pain; b) Fever i.e. oral temperature 38°C or higher on any occasion; c) Abnormal vaginal discharge, e.g. presence of pus; d)Abnormal smell/foul odor of discharge and Delay in the rate of reduction of the size of uterus (<2cm/day during the first 8 days) (7). To ensure avoiding concomitant infections, the blood samples were collected by trained laboratory technicians.

2.1. Specimens Collection

Hundred and seventy blood samples were collected from the patients suffering from puerperal sepsis. Twenty ml of venipuncture blood were drawn into two bottles of blood culture under aseptic condition, and it was immediately transferred to the laboratory for bacteriological examination.

2.2. Cultural technique

Two bottles of blood culture (Plasmatic Ltd., UK) were incubated one aerobically and the other anaerobically at 37°C for 24-48 hours. Presumptive turbidity growth in the blood culture bottles were sub cultured in aerobic and an anaerobic condition into blood agar and nutrient agar plates(Plasmatic Ltd., UK), at 37°C for 24-48 hours before discarded the pates after 3 day (8).

Examination of presumptive colony:

The presumptive culture of the plate cultures were examined morphologically with the naked eye (size, pigment, edge, etc) and Grams stain. Organisms that had pure growth were subjected to subsequent different biochemical tests for species identification, according to methods described previously by many workers (8, 9, 10).

2.3. Susceptibility to Antibiotics

The isolated bacteria were subjected to Antibiotics susceptibility test for numbers of antibiotics routinely uses in hospital which including; Penicillin (10 μg), Ampicillin (10 μg). Vancomycin (30 μg) Metronidazole (5 μg), Gentamicin (10 μg), Methicillin (10 μg), Ceftriaxone (30 μg) by disc diffusion technique (Kirby-Bauer method). These antibiotics discs were commercially prepared (Plasmatic Ltd., UK). The result was reported by measured zone of the inhibition growth by mm around antibiotic discs according to the NCCLS for different zone diameter standards to determine sensitive, intermediate or resistant strains (8).

2.4. β-Lactamase Test

Strips were used to detect the presence of beta-lactamase enzyme rapidly. Two to three colonies of the tested organism taken from the plate performed for antibiotic susceptibility test containing Penicillin G and Cephalosporin (11) (Dominique, 2004). Change in color of the test strip from purple to yellow in the area of inoculation within 5-10 minutes considered a positive beta-lactamase test according to the manufacturer procedure (AbtekBiologicals Ltd., Liverpool).

Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus Strips Test: Strips were used to confirm rapidly Methicillin-resistant S.aureus (11). According to the manufacturer procedure (AbtekBiologicals Ltd., Liverpool).

The Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS 15 for Windows) was used for data recording and statistical analyses. The descriptive analyses used included the mean, standard deviation, and frequency distribution.

3. RESULTS

The total study population comprised 170 women with severe puerperal sepsis, diagnosed by the clinician according to the history, symptoms; signs. Patients were admitted to Hussein Mustafa Hospital, Sudan within the first two weeks after delivery.

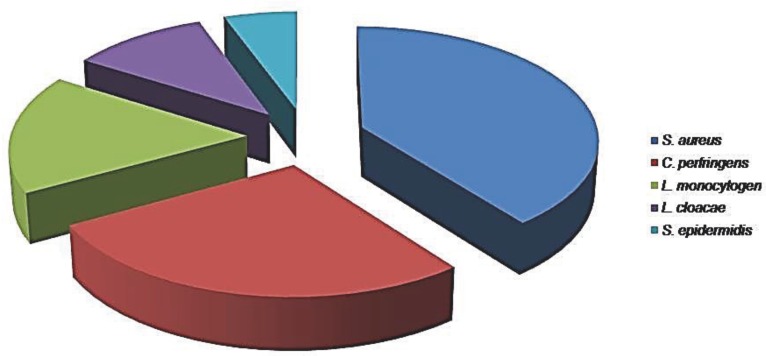

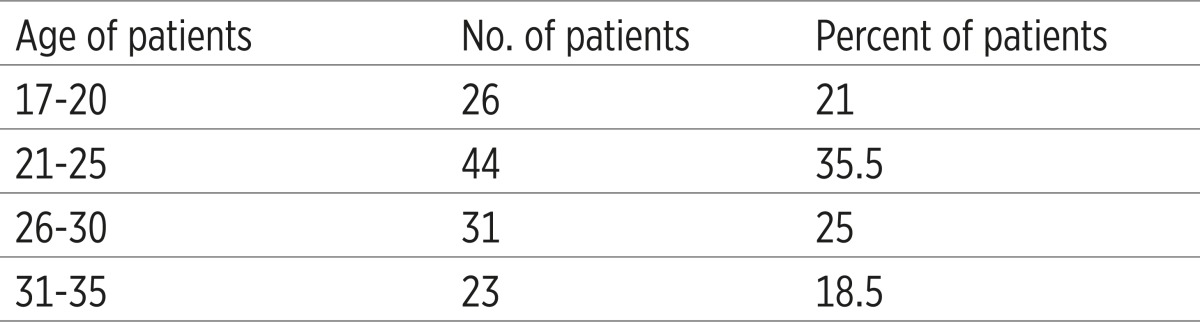

The mean maternal ages of patients were 25.48 years (ranged 17 to 35). Out of 170 admitted cases, 124(72.9%) patients had positive bacterial blood culture whereas; in the remaining patients, 46 (27.1%) no potential pathogens were isolated. The majority of these isolates were aerobic bacteria 77 (62.1%), and the anaerobic bacteria were isolated from34 (27.4 %) patients. The age groups between 21 to 25 years had the highest rate of infection were 44(35.5 %) ; followed by the age groups of 26 to 30 years were 31(25 %); while those at the extreme of age in less than 20 years were 26(21%) and 31 years and more23 (18.5%) had the lowest rate of infection, (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Types of bacterial isolates from 124 women with puerperal sepsis.

Out of 124 of the isolates, Staphylococcus aureus was the most prevalent organism 49 (39.5%) of which Methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA) was 41% (n=41/49); followed by C. perfringens, which constituted 34(27.4%), L monocytogenes showed prevalence of 21(16.9%); E. cloacae 13(10.5%); and staphylococcus epidermis was identified in 5.6% (n=7) of cases.

The results showed that the highest rate of infection was among women who delivered vaginally 121 (97.6%) compared to those who delivered by caesarean section 3 (2.5%). Out of the 116 women who delivered vaginally and had a sepsis; 112 (96.6%) of them were home deliveries, whereas only 4 (3.4%) delivered vaginally at the hospital. (Table 1,2).

Table 1.

Distribution of women with puerperal sepsis at different age groups (N=124)

|

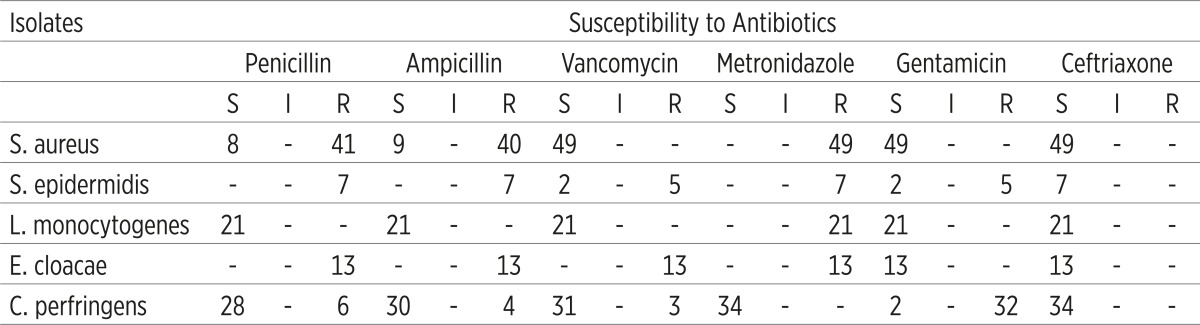

Table 2.

Antibiotics susceptibility tests for 124 bacterial isolates from women with maternal sepsis. Key S = Sensitive, I = Intermediate, R = Resistant

|

It is also shown that the percentage sensitivity of the different isolates to various antimicrobial agents used in 124 women with puerperal sepsis. The isolated bacteria were subjected to in vitro antimicrobial susceptibility test using the disc diffusion technique (Kirby-Bauer method). The degree of sensitivity, described as sensitive, intermediate, and resistance of the isolated bacteria to antibiotics were recorded.

4. DISCUSSION

In the past decade, maternal sepsis has been a common pregnancy-related event, which could eventually lead to fatal obstetric complications. This study was conducted in response to hospital records what showed an increasing rate of puerperal sepsis. In 2010, the reported hospital rate was as high as 12%.

Our findings do not represent maternal morbidity in Gadarif district because it was a hospital-based study, only patients with severe disease reported to the hospital and most of the deliveries occurred at home due to unavailability of medical care, financial constrains, lack of transportation and cultural believes.

In this study, the highest incidence of maternal sepsis was observed among young females, aged 21-25 years (35.5 %.), followed by 26-30 years (25%). Previous studies have demonstrated similar findings (12, 13). It reasonable to expect such finding occurred in old women due to increase in several pregnancy complications including maternal sepsis (14, 15). We speculate that women at this age were likely to be primigravida with untested pelvises they resort to hospitals when labor became obstructed and infected.

Strikingly, 72.9 %(n=124) of our patients had positive bacterial blood culture and the majority 72.6% (n=90) of these isolates were aerobic bacteria, which were mainly S. aureus39.5%, of which Methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA) was the predominant isolates 41% (n=41/49). Traditionally, in the western countries, Streptococcus pyrogen have been a major cause of maternal puerperal sepsis (16, 17). Recently, community associated MRSA (CA-MRSA) have become the predominant isolates, it has been described in patients with skin, soft tissue infections and pneumonia. Carrier may transmit the organism to another person via direct contact with infected hands (18). However, this high rate of MRSA, which may indicate community-acquired infection because the majority 96.6% of our patients delivered at home under unhygienic condition and most of these deliveries were conducted by traditional birth attendant. Such results necessitate urgent tracing of the risks factors by conducting further researches.

In the present study, Staphylococcus epidermidis was isolated in 5.6% of cases; earlier reports documented that S. epidermidis were the most common bacterial isolates in puerperal sepsis Gerstner et al (19). Septicemia caused by S. epidermidis is rarely reported. Although, S. Epidermidis is not usually pathogenic, but patients may acquire the infection when they have compromised immunity as in pregnancy. These findings may indicate regional variation in isolates as a cause of puerperal sepsis due to differences in geographical locations and immunity. In addition, since the majority of the studied population were home deliveries the source of infection might be exogenous where pathogens from nearby skin flora or contact with contaminated nonsterilized instruments, frequent vaginal examination with unwashed hands. In addition, the use of local herbal products for proper wound healing and treatment of established wound infections may contribute to increase of infection rate.

In this study, 16.9 % of the study population was found to have positive blood culture for L monocytogenes. José A. et (20) reported that pregnant women and immune-compromised patients are predominantly affected with L. monocytogenes. In the past, several outbreaks of food borne diseases were reported, Farber and Peterkin (21) reported in 1991 outbreaks with mortality of 24%. Our high reported cases of such infection are possible due outbreaks rather than sporadic cases, as there was 12% increase in the rate of sepsis which initiated the idea of this study.

From the total isolates, 27.4 % of the recovered species were C. perfringens. Patients who are infected with C. perfringens are not essentially developing gas gangrene; the disease can display a wide spectrum of clinical presentations (22, 23). Recently, it has become apparent that the presence of clostridium perfringens is unusual, but not rare, causes of tissue and bloodstream infections. Studies in which blood samples were obtained from patients in tertiary-care facilities have shown that C. perfringens were the most frequently identified pathogens accounted for 20% to 50% of isolates (24). In La Crosse, Wisconsin, a retrospective study carried from 1990 through 1997 to determine the incidence and clostridium species among the inpatients, the main clostridium species were Perfringens with an incidence rate of 21.7%. The main source of the infection was the gastrointestinal tract (25). The high rate in our study may be due to the fact that women in rural areas experiences unattended labor, during bearing down they soiled the perineum with fecal matter. These organisms may get access to the blood through fecally infected episiotomy and decircumcision; wounds leading to C. perfringens bacteremia.

The present study showed differences in antibiotic susceptibility pattern of the isolates to antibiotics used for the treatment of puerperal sepsis. The isolates of S. aureus were in considerable variation in term of antibiotic susceptibility, in which 83.7% of the isolated strains were identified as MRSA. Similar study as reported by Stone (26) which showed that 85.5% (55/47) of the isolates were MRSA.

The present study yielded that Ceftriaxone was 100% effective over all isolates. Similar observations had been reported by Pokharel et al (27). Less susceptibility was reported by Kankuriesko (28). This variation could be ascribed to geographical variation and the difference in the immune response. Metronidazole was shown to have great affectivity against anaerobic bacteria, and it was ineffective to all aerobic bacteria. Metronidazole is regarded as the drug of choice for the treatment of anaerobic bacteria sepsis Boyanova (29).S. aureus; L. monocytogenes were 100% sensitive to vancomycin, while C. perfringens sensitivity to vancomycin was 94.1%. Ampicillin was 100% effective against L. monocytogenes, while it was 88.2% effective against C. perfringens. Penicillin was remarkably effective against L. monocytogenes (100%), but it was ineffective against S. epidermidis and E. cloacae. On the other hand, Gentamicin was more effective against E. cloacae, L. monoctogenes (100%), while 94.1 % of C. perfringens were resistant to Gentamicin. A previous study demonstrated a similar finding (30) which showed that Gentamicin is ineffective against anaerobic bacteria, primarily useful in aerobic gram negative bacterial infection such as Enterobacter.

The shortcomings of this report, it was a hospital based study which did not reflect puerperal infection in the whole community, and we did evaluated maternal fetal comes in the study population.

5. CONCLUSION

In this study, the infection rate in this study was high, and the isolates were totally different from previous reports. These changes in microbial profile require a revision of the antimicrobial sensitivity pattern in patients with puerperal sepsis. Community-based studies will be more valuable and informative due variations in habits and cultures. To ensure achievement towards MDG5, active intervention by medical staff and government is required to achieve a 5.5% annual reduction rate as proposed by MDG5. In this study, the rate of sepsis increased with home deliveries, in addition to younger age group. Improving accessibility to in-hospital care and midwife services will reduce morbidity associated with maternal sepsis in rural areas. Each hospital should implement its standardized guidance for sepsis care. Further community-based research is recommended.

Conflict of interest

None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.United Nations. Road map towards the implementation of the United Nations Millennium Declaration: report of the Secretary General. 2001.

- 2.Dafallah SE, El-Agib FH, Bushra GO. Maternal mortality in a teaching hospital in Sudan. Saudi Med J. 2003 Apr;24(4):369–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Araoye MO. Epidemiology of infertility: social problems of the infertile couples. West Afr J Med. 2003 Jun;22(2):190–196. doi: 10.4314/wajm.v22i2.27946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Umeora OU, Mbazor JO, Okpere EE. Tubal factor infertility in Benin City, Nigeria–sociodemographics of patients and aetiopathogenic factors. Trop Doct. 2007 Apr;37(2):92–94. doi: 10.1177/004947550703700211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schaaf VM, Perez-Stable EJ, Borchardt K. The limited value of symptoms and signs in the diagnosis of vaginal infections. Arch Intern Med. 1990 Sep;150(9):1929–1933. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bornstein J, Lakovsky Y, Lavi I, Bar-Am A, Abramovici H. The classic approach to diagnosis of vulvovaginitis: a critical analysis. Infect Dis Obstet Gynecol. 2001;9(2):105–111. doi: 10.1155/S1064744901000187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Report of a technical working group. Geneva: 1992. The prevention and management of puerperal infections. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Barrow GI, Feltham RK. Cowan and Steel’s Manual for the identification of medical bacteria, character of Gram-positive bacteria. 3rd ed. Vol. 188. Cambridge university press; 1993. pp. 59–67. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ochei J, Kolhatkar A. Medical Laboratory Science, theory and practice. New 7Delhi: Tata McGraw-Hill publishing company limited; 2000. p. 525.p. 856.p. 758.p. 759.p. 623. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cheesbrough M. District Laboratory Practice in Tropical Countries, part 2, Cambridge low-priced edition. Cambridge university press; 2000. pp. 157–166.pp. 201–04.pp. 32–407. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dominique L. Antimicrobial drug use and Methicillin resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Emerging Infectious Disease. 2004;10(8) doi: 10.3201/eid1008.020694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mumtaz S, Ahmad M, Aftab I, Akhtar N, ul Hassan M, Hamid A. Aerobic vaginal pathogens and their sensitivity pattern. J Ayub Med Coll Abbottabad. 2008 Jan-Mar;20(1):113–117. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Khan I, Khan UA. A hospital based study of frequency of aerobic pathogens in vaginal infections. J Rawal Med Coll. 2004;29(1):22–25. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kramer HM, Schutte JM, Zwart JJ, Schuitemaker NW, Steegers EA, van Roosmalen J. Maternal mortality and severe morbidity from sepsis in the Netherlands. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2009;88(6):647–653. doi: 10.1080/00016340902926734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Usha Kiran TS, Hemmadi S, Bethel J, Evans J. Outcome of pregnancy in a woman with an increased body mass index. BJOG. 2005 Jun;112(6):768–772. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2004.00546.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sriskandan S. Severe peripartum sepsis. J R Coll Physicians Edinb. 2011 Dec;41(4):339–346. doi: 10.4997/JRCPE.2011.411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cantwell R, Clutton-Brock T, Cooper G, Dawson A, Drife J, Garrod D, et al. Saving Mothers’ Lives: reviewing maternal deaths to make motherhood safer: 2006–2008. The Eighth Report of the Confidential Enquiries into Maternal Deaths in the United Kingdom. BJOG. 2011;118(Suppl 1):1–203. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2010.02847.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Maree CL, Daum RS, Boyle-Vavra S, Matayoshi K, Miller LG. Community-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus isolates causing healthcare-associated infections. Emerg Infect Dis. 2007 Feb;13(2):236–242. doi: 10.3201/eid1302.060781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gerstner G, Leodolter S, Rotter M. Endometrial bacteriology in puerperal infections (author’s transl) Z Geburtshilfe Perinatol. 1981 Oct;185(5):276–279. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vázquez-Boland JA, Kuhn M, Berche P, Chakraborty T, Domínguez-Bernal G, Goebel W, et al. Listeria pathogenesis and molecular virulence determinants. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2001 Jul;14(3):584–640. doi: 10.1128/CMR.14.3.584-640.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Larraín de la CD, Abarzúa CF, Jourdan HF, Merino OP, Belmar JC, García CP. Listeria monocytogenes infection in pregnancy: experience of Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile University Hospital. Rev Chilena Infectol. 2008 Oct;25(5):336–341. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jemni L, Chatti N, Chakroun M, Allegue M, Chaieb L, Djaidane A. [Clostridium perfringens septicemia] Rev Fr Gynecol Obstet. 1988 Jun 15;83(6):407–409. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Finegold SM, George WL. Anaerobic infections in humans. San Diego: Academic Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Onderdonk AB, Allen SD. Clostridium. In: Murray PR, Baron EJ, Pfaller MA, Tenover FC, Yolken RH, editors. Manual of clinical microbiology. 6th ed. Washington, DC: ASM Press; 1995. p. 580. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rechner PM, Agger WA, Mruz K, Cogbill TH. Clinical features of clostridial bacteremia: a review from a rural area. Clin Infect Dis. 2001 Aug 1;33(3):349–353. doi: 10.1086/321883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Stone ND, Lewis DR, Johnson TM, 2nd, Hartney T, Chandler D, Byrd-Sellers J, McGowan JE, Jr, Tenover FC, Jernigan JA, Gaynes RP. Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) Nasal Carriage in Residents of Veterans Affairs Long-Term Care Facilities: Role of Antimicrobial Exposure and MRSA Acquisition. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2012 Jun;33(6):551–557. doi: 10.1086/665711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pokharel MS. Study on antibiotics sensitivity pattern of bacterial flora in cases of pre-labour rupture of membrane. [Dissertation] Kathmandu, Nepal: Tribhuvan University; 2004. p. 108. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kankuriesko E, Kurkitatio T, Carison T, Esmaa HM. Incidence, treatment and outcome of peripartum sepsis. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scan. 2003;82(8):730–735. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0412.2003.00265.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Boyanova L, Kolarov R, Mitov I. Antimicrobial resistance and management of anaerobic infections. Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther. 2007 Aug;5(4):685–701. doi: 10.1586/14787210.5.4.685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.James B. Evans, Lizzie J. Harrell. Agar Shake Tube Technique for Simultaneous Determination of Aerobic and Anaer]obic Susceptibility to Antibiotics. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1977 Oct;12(4):534–536. doi: 10.1128/aac.12.4.534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]