Abstract

In Bosnia and Herzegovina citizens receive health care from both public and private providers. The current situation calls for a clear government policy and strategy to ensure better position and services from both parts. This article examines how health care services are delivered, particularly with respect to relationship between public and private providers. The paper notes that the public sector is plagued by a number of weaknesses in terms of inefficiency of services provision, poorly motivated staff, prevalent dual practice of public employees, poor working conditions and geographical imbalances. Private sector is not developing in ways that address the weaknesses of the public sector. Poorly regulated, it operates as an isolated entity, strongly profit-driven. The increasing burdens on public health care system calls for government to abandon its passive role and take action to direct growth and use potential of private sector. The paper proposes a number of mechanisms that can be used to influence private as well as public sector, since actions directed toward one part of the system will inevitable influence the other.

Key words: Health care system, public and private sector, policy and strategy.

1. INTRODUCTION

This report examines current challenges to the provision of health care services in FBiH, with respect to the impact of public and private providers and makes recommendations for the government of possible courses of action through possible utilization of private sector. It also examines the current features of both public and private providers and the interface between the two.

General remarks on the provision of health care services are: fiscal constraints, inefficient provision of services in public sector, geographical imbalance in citizen’s access to health care, poorly regulated private health care providers.

The paper presents alternative approaches the government can take towards private sector and reasons supporting recommended solution including the specific measures to be taken both on a public and private side of health services provision to best utilize potentials of both sectors.

The authors outline steps that have to be taken in order to implement a recommended solution and chapter four will present conclusions and recommendations. Main focus of the paper is on the side of health service delivery.

2. METHODOLOGY

Main method used by authors was the review and analysis of the main legal, policy and strategy documents on health system, relevant for determining public and private sector in the health care system of the Federation BiH.

Authors also analyzed technical documents, project reports and publications, produced by agencies which are, have been or were running the projects in BiH relevant also for public and private health care capacities and structures development and identification of those issues which might require changes.

Little or no integrated data on the composition and activities of the private health sector in FBIH makes analyses and comparison difficult. The information was largely collected through “informal talks” with the officials from the Federal MOH, Federal PHI, Federal HIF and private providers. However, ample information exists on the types of public/private partnerships in broader environment and this report draws on this experiences.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Situation analysis

The health care system is highly decentralized, with 10 cantons (regional)-level organization and financing of health care. The system mainly relies on public providers. The post-war reforms of health care system in FBIH have been focused on the organizational and financial aspects of the public sector aimed at providing health care for all its citizens on the principles of solidarity and equity which is hampered by fiscal constraints.

The following institions are registered in FBIH public health sector: 2 clinical centres, 1 clinical hospital, 11 Public Health Institutes , 7 cantonal hospitals, 8 general hospitals, 2 special hospitals, 3 spas, 11 institutes for specific health services,out of which 6 are occupational medicine institutes, 79 health centres, and 64 pharmacies (Federal HIF, 2010, p.14). In 2010, there were 26,908 employees in health institutions in public sector and 2.614 employees in private sector. Total number of employees in direct health services providers was 21,138, (73.3%) with 7.685 nomedical employing persons. (Federal HFI 2010, p.18).

Public health care facilities are unevenly distributed in favor of urban facilities and prevalence of narrow specialists (Cain et al., 2002, p.32). The network is highly fragmented, characterized by inadequate resource allocation and inappropriate balance of primary, secondary and tertiary level (the latter two estimated for 60% of total health care provision). Work conditions in public sector are poor, with outdated equipment. The highest proportion of budget is spent on salaries and other personal income of employees (41.02 % in 2010), drugs and medical consumables (22.83% and 7.30% respectively), other material costs 6.91%, etc. with no sufficient funds for investments in new equipment (Federal HIF, 2010, p.26). There are long waiting lists for certain services, e.g. sophisticated diagnostic services. Quality of care in public sector is often perceived as poor, with staff being considered as highly unresponsive. Under the table payments are also present.

Large number of public employees simultaneously work in private practices, combined with the use of public resources for private purposes and doctors frequently referring patients to their own private practices. Public employees are paid on the basis of fixed salaries, wit quality and quantity having no impact on staff’s earnings, which results in reduced motivation.

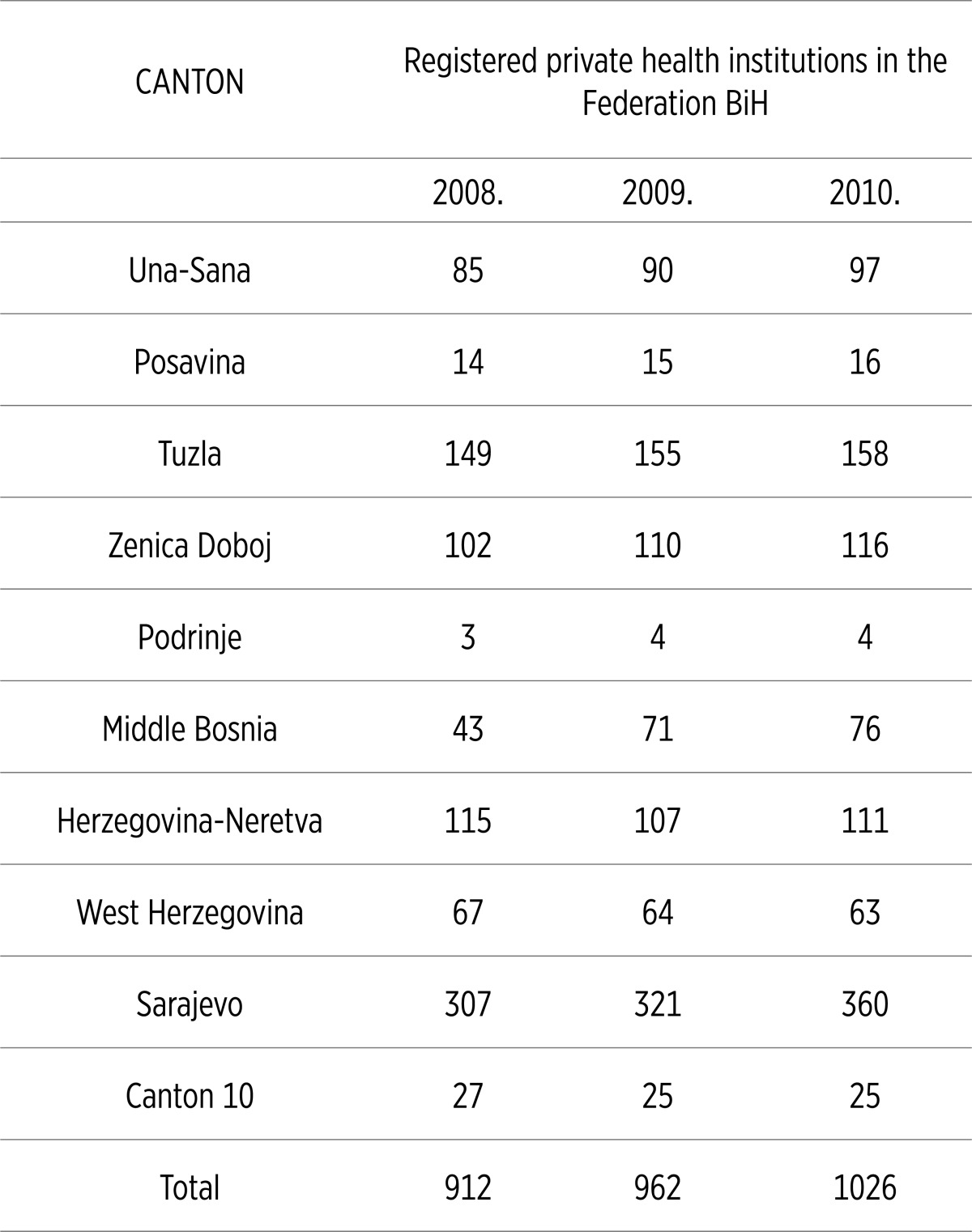

Private providers tend to concentrate in urban areas and wealthier cantons as reflected in Table 1 (wealthiest cantons are Tuzla and Sarajevo canton).

Table 1.

Distribution of registered private health institutions across cantons in FBiH (Source: Federal HiF, 2010)

|

Private sector consists mainly of dentist offices, ambulants and policlinics providing specialist and primary level services, and private pharmacies. In 2010, there were 1026 private health institutions in the FBiH, out of which 257 were private pharmacies, with 2.614 employees (Federal HIF, 2010, p. 15).

Numbers are considered inacurrate since not all the private institutions submit data. Furthermore, a high number of public medical cadre also works in registered private institutions without being officialy reported as private employees along with publicly-employed doctors often working at homes in unnregistered private practices. Official data show that in 2010, in the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina, total expenditure on health as percentage of GDP was 10.4. Private expenditure on health as percentage of total expenditure on health accounting for 50.6% (WHO, 2007). Local experts tend to disagree, estimating private spending not higher than 30% of total health expenditure. Official data show higher discrepancies, with public health expenditure accounting for 90.2% of total health expenditure in 2010 but this is explained by incomplete data from private sector (Federal HIF, 2010, p. 24).

Basic regulation for private sector is mainly focused on registration of private providers. Establishment of private hospitals is not authorized by law. However, in larger urban centers physicians often merge into policlinics with a scope of different services provided to clients (PHC, diagnostic services, specialist-consultative services).

Private practitioners can earn their income through contracts with the respective HIF if they are integrated in the network of public providers, through voluntary health insurance and direct payments from patients (MoH, 2009). Voluntary health insurance schemes started developing recently, with a small niche of wealthy beneficiaries. Contracts with HIFs are not present as private providers do not participate in the network of public providers. The main source of their income are direct payments from patients (fee-for-service).

Quality of care in private sector is perceived by patients as very high, but client’s opinion is frequently based on private providers´ responsiveness and sophisticated equipment. On the other hand, public sector often expresses concern about quality of care in private practices.

There is a high mistrust between public and private far ends of the system, i.e. between health workers who work in one sector exclusively. Registered private practitioners express dissatisfaction with public employees´ parallel work in private sector as they do not pay taxes on additional income.

3.2. Trends and advisable options

There are different approaches available for health authorities towards private sector. It can decide to allow for further development without much intervention hoping it would attract affluent niches of population who can pay private services. Such approach would allow for focus on public health functions and care for less affluent groups under fiscal constraints.

The second option would be to try to utilize potential of private sector as alternative source of health care provision and to address problems associated with private provision of services. Governments in developing and developed countries concentrate their efforts on exploring different forms of partnerships with private sector.

One strategy would be to utilize the potential of private sector offering services to publicly-funded patients, for services for which demand cannot be met adequately by public providers. e.g. laboratory services, imaging, radiology. It would be less expensive to enter into partnership with an existing private provider who will provide workforce and equipment than to enter into such investment on public sector side.

Also private sector could be supplement for public provision of services. Unequal distribution of public providers’ network results in limited access in some remote areas. Private providers can be offered to fill in in such areas. There are areas of health care where public provision is particularly inadequate, for example mental health and care for elderly.

Transfer provision of services from public to private providers should be based on careful analysis of cost effectiveness, i.e. whether it is more cost-effective to offer public services or to do so through a private provider.

Extra space in public facilities can be rented under favorable conditions. Rent payments represent a significant cost for the private practices in urban centers, and on the other hand, it would represent an additional source of income for public facility.

In the midd-term strategic plan privatization in health care is envisaged as a final form of decentralization and was to be restricted to family medicine ambulants, with the equal status of public and privatized units (Federal MOH, 1998, p.29). Such approach has never been implemented and talks about private sector were suspended.

One option that should certainly be avoided is preserving status quo and continuing with the approach of unregulated functioning of private sector. Private sector serves a substantial proportion of patients and the issue of quality of the services, medical malpractice and behavior consistent with the proclaimed goals of national health system is important.

Lack of control and knowledge about activities in the private sector has implications on patients and public service. For example, there is a lack of a comprehensive view on health status which can result in a wrong treatment and shifting costs to public sector, since when things go wrong, patients turn to public facilities as these are legally obliged to provide care. Once again it must be emphasized that the choice of strategy for the involvement of private sector heavily depends on comprehensive analysis.

3.3. Ministry of health’s policies

The most effective instrument to control the behavior of private providers who enter into arrangements to provide their services to publicly-funded patients are contracts that would define volume and scope of services to be provided, price, payment model and time period during which the services will be provided. Existing contracts with public health care providers are input based. A shift should be made to output and outcomes based contracts, including performance and quality elements, for both sectors.

To address concerns about quality of care provided in private sector and to ensure that private providers remain abreast with modern medicine developments, re-licensing can be enforced. Pursuing continuing education should be prerequisite for obtaining new license. This rule should apply to public employees too.

As another non-financial measure to ensure quality, accreditation of health care providers can be introduced. Accreditation of the provider who complies with the standards for the quality of care would send a positive signal to the clients and increase its competitive advantage.

Currently, private practitioners have to pay for specialization or sub-specialization from their own resources. For those willing to offer their services to publicly-funded patients, government could offer to subsidy costs of education. Tax relief for starting up a new business, for example in remote areas, could be offered, as loans for purchasing capital equipment are difficult to obtain. There are also means of indirect influence of private practitioners, for example MOH can distribute information on quality and prices of services of different providers to the public.

Evidence based medical protocols should be devised, introduced and distributed to the providers and included into contracts. As said before, private sector expansion is closely related to the deterioration of standards of care offered in public sector. Bennett (1992, p. 108) argues that if public sector offers quality care at reasonable price, this will discipline private sector and lead to better care at lower prices.

Actions directed toward a greater participation of private sector will necessarily have an impact on public sector. Attempts to increase contribution of private sector may be met with strong opposition of the public sector. It may also lead to a shift of doctors from public to private sector. Main objection of the public employees are low salaries. Having in mind budgetary constraints, it is difficult to expect their significant raise. It would be possible to compensate it with financial incentives for rewarding good performance and sanctions for a poor one. Performance management system should be introduced. Martinez and Martineau (1998) emphasize the role of manager, i.e. power to take action and need for possession of appropriate HR skills.

One important issue that should be addressed is dual practice. Ferrinho et al. (2004) argue that the least effective approach is the prohibition and attempts to compensate doctors financially for the loss of private practice are not very feasible. MoH could address dual practice by introducing long-term part-time contracts for public employees engaged in private practice or offer better conditions for staff solely employed in public sector, for example advantage in promotion over the second group.

4. DISCUSSION

In order to allow greater involvement of private sector some pre-requisites must be fulfilled. Firstly, health authorities must have reliable data on the size and activities of private sector and further practice of avoidance of data submission is absolutely unacceptable. Flow of data from cantonal to central level should be improved. Working group consisting of members from the Federal PHI, Federal MOH and Federal HIF should be formed to supervise and coordinate efforts of different levels.

Secondly, there should be a greater involvement of private sector in the policy formulation and creation of legislative framework. By doing so, it would be possible to come up with solutions that are more likely to be implemented. Dialogue between professional associations of public and private sector and government should be encouraged.

Health authority’s capacity to devise policies, monitor and update them is weak. It must be improved with HR units having a stronger position in the Ministry. HR departments should be established in respective cantonal ministries. Staff should receive training to improve their capacity. To make a shift to new contracts, contracting skills of the staff in HIFs should be improved.

5. CONCLUSIONS

Against the background of increasing burdens on health care services, it seems clear that the public sector is not in a position to address its weaknesses by itself.

In oder to fill existing gaps, government may opt to allow private providers to continue development without government direction or intervention but that is not recommended course of action. Government must try to strengthen health care services by utilizing private sector potential based on clear health policy and strategy. To do so meaningfully, it must first fill the information gap on which clear policies must be based.

This will require close cooperation of all institutions involved in the process at the same level and better coordination between different levels of the system. Based on it, new policies would be devised to diminish existing systemic imbalances, and potentially to reduce the cost to citizens and the government.

Policies would be directed towards private and public part of system. Collaboration between both sectors and health authorities in the process is crucial. This will give a sense of ownership of policies to all the parties involved in process and ensure their successful implementation.

The success of any adopted measures will rely on the ability of government to gather reliable data, as well as to regularly monitor and update these strategies, which requires personnel with appropriate knowledge and skills.

The process will require time and additional finances to perform the above tasks but it is surely wiser to take active approach now as it would be difficult to do so when private sector becomes too powerful.

Conflict of interest

None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Afford CW. Privatization of health care in Central and Eastern Europe. Retrieved November 26, 2007 from http://www.epsu.org/IMG/pdf/Final_Edited_Report.pdf . 2001.

- 2.Bennett S. Promoting the private sector: a review of developing country trends [Electronic version]. Health Policy and Planning. 1992;7(2):97–110. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cain J, Duran A, Fortis A, Jakubowski E. Health care systems in transition: Bosnia and Herzegovina. Retrieved November 15, 2007, from http://www.euro.who.int/document/E78673.pdf . 2002.

- 4.Federal Health Insurance Fund. Sarajevo: Federal Health Insurance Fund, Sarajevo; 2010. National health resources account for FBiH. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Federal Ministry of Health. Sarajevo: Federal Ministry of Health, Sarajevo; 2009. The Law on health care. Federation BiH Official Gazzete no.29/09. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Federal Ministry of Health. Sarajevo: Federal Ministry of Health, Sarajevo; 1998. Strategic plan for the reform and reconstruction of health care system in the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina for the middle-term period. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Federal Public Health Institute. “Health status of the population and health care in the Federation BiH”. Forthcoming.

- 8.Federal Office of Statistics. Sarajevo: Federal Office of Statistics, Sarajevo; 2010. Statistical yearbook. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ferrinho P, Van Lerberghe W, Fronteira I, Hipolito F, Biscaia A. Dual practice in the Health Sector: review of the experience. Human Resources for health, 2 Retrieved November 25, 2007, from http://www.human-resources-health.com/content/2/1/14 . October 27, 2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 10.Frenk J. The public-private mix and human resources for health. Health Policy and Planning. 1993;8(4):315–326. doi: 10.1093/heapol/8.4.315. [Electronic version] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gotsadze G, Jugeli L. Private-public partnership in Georgia: A case study of contracting an NGO to provide specialist service. Retrieved December 01, 2007, from HRH Global Resource Centre Web site: http://www.dfidhealthrc.org/publications/health_service_delivery/Gotsadze_Jugeli.pdf . 2004.

- 12.Harding A. Keystone Module Background Paper 1. Private Participation in health services handbook. Retrieved November 10, 2007, from Health, Nutrition and Population Department, The World Bank Web site: http://siteresources.worldbank.org/INTINDONESIA/Resources/Human/PHS-Harding-01.pdf . 2001.

- 13.Hebrang A, Henigsberg N, Erdeljic V, Foro S, Vidjak V, Grga A, Maček T. Privatization in the health care system of Croatia: effects on general practice accessibility. Health Policy and Planning. 2003;18:421–428. doi: 10.1093/heapol/czg050. [Electronic version] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hicks V. Public Policy and Private Providers in Health Care. 2003. Unpublished.

- 15.Hornby P, Ray DK, Shipp PJ, Hall TL. Geneva: World Health Organization, Geneva; 1980. Guidelines for health manpower planning. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Martinez J, Martineau T. Rethinking human resources: an agenda for the millennium. Health Policy and Planning. 1998;13(4):345–358. doi: 10.1093/heapol/13.4.345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McPake B, Ngalanda BE. Contracting out of health services in developing countries. Health Policy and Planning. 1994;9(1):25–30. doi: 10.1093/heapol/9.1.25. [Electronic version] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mills A. Improving the efficiency of public sector health services in developing countries: bureaucratic versus market approaches. PHP Departmental Publication no.17. London School of Tropical Medicine, London. 1995.

- 19.Nikolic AI, Maikisch H. Public-private partnerships and collaboration in the health sector. Retrieved November 10, 2007, from Health, Nutrition and Population Department, The World Bank Web site. 2006.

- 20.http://siteresources.worldbank.org/INTECAREGTOPHEANUT/Resources/HNPDiscussionSeriesPPPPaper.pdf .

- 21.Propper C, Green K. A larger role for the private sector in health care? A review of the arguments. Retrieved November 15, 2007, from University of Bristol, CMPO Web site: http://www.bris.ac.uk/cmpo/workingpapers/wp9.pdf . 1999.

- 22.Švab I, Vatovec Progar I, Vegnuti M. Private practice in Slovenia after the health care reform. European Journal of Public Health. 2001;11:407–412. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/11.4.407. [Electronic version] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.http://www.who.int/whosis/database/core/core_select_process.cfm?country=bih&indicators=nha .