Abstract

Following right pneumonectomy (PNX), the remaining lung expands and its perfusion more than doubles. Tissue and microvascular mechanical stresses are putative stimuli for compensatory lung growth and remodeling, but their relative contribution remains uncertain. To temporally separate expansion- and perfusion-related stimuli, we replaced the right lung of adult dogs with a customized inflated prosthesis. Four months later, the prosthesis was either acutely deflated (DEF) or kept inflated (INF). Thoracic high-resolution computed tomography (HRCT) was performed pre- and post-PNX before and after prosthesis deflation. Lungs were fixed for morphometric analysis ∼12 mo post-PNX. The INF prosthesis prevented mediastinal shift and lateral lung expansion while allowing the remaining lung to expand 27–38% via caudal elongation, associated with reversible capillary congestion in dependent regions at low inflation and 40–60% increases in the volumes of alveolar sepal cells, matrix, and fibers. Delayed prosthesis deflation led to further significant increases in lung volume, alveolar tissue volumes, and alveolar-capillary surface areas. At postmortem, alveolar tissue volumes were 33% higher in the DEF than the INF group. Lateral expansion explains ∼65% of the total post-PNX increase in left lung volume assessed in vivo or ex vivo, ∼36% of the increase in HRCT-derived (tissue + microvascular blood) volume, ∼45% of the increase in ex vivo septal extravascular tissue volume, and 60% of the increase in gas exchange surface areas. This partition agrees with independent physiological measurements obtained in these animals. We conclude that in vivo signals related to lung expansion and perfusion contribute separately and nearly equally to post-PNX growth and remodeling.

Keywords: mechanical deformation, lung resection, compensatory lung growth, high-resolution computed tomography, morphometry

the lung is a tensegrity structure (24) where constant and dynamic physical tensions among its constituent parts are generated by the actions of two pumps (ventilatory and cardiac) propelling two media (air and blood) over a large interface geometrically folded within a finite thoracic container.1 Mechanical interactions among the constituents of the lung and between the lung and the thorax transduce biochemical signals that coordinate cellular processes and maintain the architectural, and consequently functional, integrity of the organ (1, 8). Lung growth during development and growth reinitiation during adulthood cannot occur normally in the absence of appropriate mechanical signals. In adult canine lung following right pneumonectomy (PNX; resection of 55–58% of lung units), the remaining lung expands asymmetrically across the midline and nearly doubles its volume. Simultaneously, perfusion to the remaining lung increases by a factor of 1/(fraction of lung removed), or ∼2.2-fold, at a given cardiac output. These mechanical factors recruit the remaining alveolar-capillary surface areas and erythrocyte volume as well as redistribute ventilation and pulmonary blood flow, ultimately improving the matching of air, tissue, and microvascular interfaces for gas exchange (9). In addition to physiological recruitment, mechanical stresses cause nonuniform deformation of the remaining tissue and capillaries (28, 29). Mechanosensitive signals stimulate multiple major homeostatic pathways to regulate cellular adaptive responses such as cell growth, proliferation, matrix deposition, and architectural remodeling (8), eventually leading to partial restoration of alveolar-capillary tissue volumes and surface areas, conductance of the diffusion barrier, and exercise capacity (13, 14).

Our goal is to understand the sources and limits of the putative in vivo stimuli for post-PNX compensation as an essential step towards designing therapeutic approaches for the induction and/or amplification of the innate regenerative potential. In earlier studies, we implanted at the time of PNX a space filling inflated silicone prosthesis in the size and shape of the removed right lung (26). The prosthesis was either kept inflated to prevent mediastinal shift and lateral lung expansion or deflated to allow mediastinal shift and lateral expansion. Long-term compensatory responses were 45–80% lower in the presence of inflated prosthesis (12, 15, 26), supporting the interpretation that lung expansion was a major stimulus triggering post-PNX compensation. However, the inflated prosthesis did not completely eliminate compensation (26), suggesting that additional stimuli, e.g., increased perfusion, may also have contributed to the adaptation in the remaining lung. Because the inflated prosthesis did not prevent a 2.2-fold post-PNX increase in perfusion to the remaining lung and the expansion- and perfusion-related signals were not temporally separated, we could not ascertain the contribution from perfusion-related stimuli to overall compensation observed in the animals with deflated prosthesis. In one animal, a delayed leak developed in the inflated prosthesis, causing subsequent mediastinal shift and lung expansion, associated with an increasing lung diffusing capacity (DlCO) over several months (26), indicating the feasibility of temporally separating the induction of lung expansion from the immediate post-PNX increase in perfusion. In a later study, delayed prosthesis deflation rapid upregulated major signaling molecules that are involved in tissue-capillary growth and remodeling, including hypoxia-inducible factor-1α, erythropoietin, and VEGF (30). However, the long-term structural effects of delayed lung expansion have not been examined.

The objective of this study was to quantitatively separate the contributions from lung expansion and the sustained increase in perfusion to post-PNX compensatory alveolar growth and remodeling of the remaining lung. Using a robust adult canine PNX model, we replaced the right lung with a space-filling inflatable silicone prosthesis constructed in the size and shape of the removed lung (11, 12, 26). The prosthesis was kept inflated to prevent mediastinal shift and lateral expansion of the remaining left lung. Following recovery (∼4 mo) to allow wound healing and stabilization of pulmonary blood flow, the prosthesis was acutely deflated in some animals to induce lung expansion and mediastinal shift. In other animals, the prosthesis remained inflated as controls. Cardiopulmonary function was measured from rest to exercise pre- and post-PNX as well as before and after deflation and reported separately (5). Noninvasive chest imaging using high-resolution computed tomography (HRCT) was performed pre-PNX and post-PNX (with inflated prosthesis or after prosthesis deflation in separate animals). At post mortem, the lungs were fixed by tracheal instillation of fixatives at a constant airway pressure for detailed quantification of ultrastructural components. Here we report the results of longitudinal imaging studies and morphometric analysis on the remaining left lung of post-PNX animals with inflated or deflated prosthesis. Morphometric data were also compared with published results from the left lung of normal adult canines (17).

METHODS

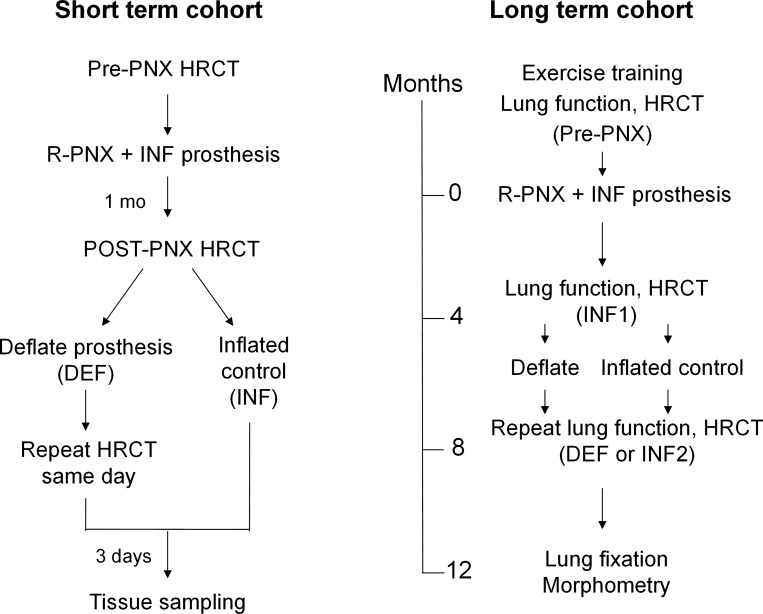

The Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center approved all protocols. Adult male mixed breed foxhounds (9–12 mo of age; Marshall BioResources, North Rose, NY) were studied in two cohorts to examine the long-term and short-term effects of delayed lung expansion. In the Long-Term Cohort (n = 9), animals were trained to exercise on a treadmill; cardiopulmonary function was measured pre-PNX and ∼4 mo following right PNX with the right lung replaced by an inflated silicone prosthesis. Then, the prosthesis was deflated in five animals (DEF group) while remaining inflated in four (INF group). The timeline is shown in Fig. 1. One animal developed a leak in the INF prosthesis 8-mo post-PNX; therefore, gas was removed from the prosthesis and the animal followed for another 6 mo before terminal lung fixation. The remaining left lung from this animal was analyzed as part of the DEF group, resulting in a total of six animals in the DEF and three animals in the INF groups.

Fig. 1.

Timeline of longitudinal studies pre- and post-right pneumonectomy (R-PNX) with the right lung replaced by an inflated (INF) prosthesis before and after delayed prosthesis deflation (DEF). Post-PNX studies were performed at one time point in the Short-Term Cohort (left) and at 2 time points (INF1 and INF2) in the Long-Term Cohort (right).

In the later Short-Term Cohort, six animals underwent right PNX and prosthesis implantation. HRCT was performed at two inflation levels pre-PNX and again ∼4 wk post-PNX; in three animals, the post-PNX scan was repeated within 30 min following acute prosthesis deflation to assess the immediate changes in lung volume and compliance.

PNX and Prosthesis Implantation

These procedures have been described in detail previously (26). Briefly, the inflatable silicone prosthesis was fabricated in the size and shape of a normal resting adult canine right lung, attached on the dorsal surface to a silicone filling tube and a subcutaneous injection port. While the animals were under general anesthesia and after a lateral thoracotomy in the fifth intercostal space, the right lung was removed and the prosthesis was placed in the empty hemithorax with the filling tube tunneled through the fourth intercostal space to the subcutaneous injection port at the neck. The prosthesis was inflated with a 50/50% mixture of sulfur-hexafluoride (SF6) and air to ∼20% above supine end-expiratory lung volume. Following surgery, gas volume in the prosthesis was measured by helium dilution weekly for the first month and then monthly. The desired volume was refilled with SF6/air. Mediastinal position was verified by chest X-ray. The deflated prosthesis contained <50 ml of gas to prevent pleating.

HRCT

Following anesthesia, intubation, and insertion of a balloon-tipped esophageal catheter, scanning was performed supine using established techniques (28, 29). Static pressure-volume curves of the lung were measured before scanning. The earlier Long-Term Cohort was studied using a General Electric high-speed CTi scanner (3 × 3 mm collimation, 120 kVp, 250 mA, pitch 1.0, and rotation time 0.8 s) at a transpulmonary pressure (Ptp) of 20 cmH2O pre-PNX and ∼8 mo post-PNX (either with INF prosthesis or ∼4 mo after prosthesis deflation in the DEF group).

The later Short-Term Cohort was studied using a GE LightSpeed 16 scanner (1.25 × 1.25 mm collimation, 120 kVp, 190 mA, pitch 1.0, and rotation time 0.8 s) at two Ptp levels (15 and 30 cmH2O), pre-PNX, and 4 wk post-PNX with inflated prosthesis (INF, n = 6). Then, the prosthesis was acutely deflated in three animals and scanning repeated within 30 min (DEF, n = 3). The images were reconstructed at consecutive 1.0-mm (Long-Term Cohort) or 1.25-mm (Short-Term Cohort) intervals from apex to base (512 × 512 “standard” reconstruction algorithm, ∼300 to 400 images per animal).

Image analysis has been described in detail previously (28, 29). Briefly, the lobes, major airways, and blood vessels were segmented using customized, semiautomatic software developed by us (Microsoft Visual C++ 6.0; Refs. 19, 20, 28). The lung area was outlined by attenuation thresholding, excluding trachea and the next three generations of conducting structures. Interlobar fissures were identified and fitted with cubic splines. CT attenuation of extrathoracic air was set at −1,000 Hounsfield units (HU) and water at 0 HU. In each animal, intrathoracic tracheal air (CTair) sampled from three locations above the carina and air-free tissue (CTtissue) sampled from infraspinatus, supraspinatus, and pectoralis muscles at the level of the carina were used to partition the total volume of each lobe (Vlobe) into air and tissue volumes (Vair and Vtissue) (19, 20):

| (1) |

| (2) |

| (3) |

where CTlobe = average CT value (in HU) of a lobe and FTV = fractional tissue volume. Overall, CTair averaged −980 ± 8 HU and CTtissue averaged +68 ± 5 HU (mean ± SD). Specific lobar compliance (Cs) was calculated from the change in lobar volume (ΔVlobe) between two levels of Ptp (ΔPtp) normalized by Vlobe:

| (4) |

Lung Fixation

Following established methods for animals under deep anesthesia (10, 18), a tracheostomy was performed. A cuffed cannula was inserted and tied securely. Following a left thoracotomy to collapse the lung, an overdose of pentobarbital and phenytoin was given intravenously. The lung was reinflated in situ by tracheal instillation of buffered 2.5% glutaraldehyde at 25 cmH2O of hydrostatic pressure above the sternum. While maintaining airway pressure, the lung was removed, immersed in buffered 2.5% glutaraldehyde, and stored at 4°C for at least 2 wk before processing. Volume of each lobe was measured by saline immersion. Each lobe was serially sectioned (1 cm), and the cut surfaces were photographed. The volume of the sectioned lobe was estimated by the Cavalieri principle (27); this tension-free volume was used in subsequent morphometric calculations.

Sampling and Morphometric Analysis

Each lobe was analyzed using a stratified scheme (10, 12, 17, 23). Level 1 (gross): serial lung sections (∼2×) were photographed for point counting to exclude structures >1 mm in diameter, yielding an estimate of the volume density of coarse parenchyma per unit of lung volume [Vv(cp,L)]. Level 2 (low power): four blocks per lobe were sampled systematically with a random start, embedded (glycol methacrylate), sectioned (5 μm,) and stained (toluidine blue). One section per block was analyzed. At least 10 nonoverlapping microscopic fields were sampled systematically for point counting (×275) to estimate the volume density of fine parenchyma in coarse parenchyma [Vv(fp,cp)] by excluding structures 20 μm to 1 mm in diameter. Levels 3 (high power) and 4 [electron microscopy (EM)]: four blocks per lobe were systematically sampled, postfixed (1% osmium tetroxide in 0.1 M cacodylate buffer), treated with 2% uranyl acetate, dehydrated through graded alcohol, and embedded (Spurr; Electron Microscopy Sciences, Hatfield, PA). For level 3, each block was sectioned (1 μm) and stained (toluidine blue). One section per block was systematically sampled (×550, 20 nonoverlapping microscopic fields per block, 80 images per lobe) to estimate the volume density of alveolar septa in fine parenchyma by excluding all structures >20 μm in diameter. For level 4, two blocks per lobe were sectioned (80 nm) and mounted on copper grids. Each grid was systematically sampled under transmission EM (JEOL EXII; approximately ×19,000, 30 nonoverlapping fields per grid, 60 images per lobe) to estimate the volume densities of septal compartments by point counting. Alveolar epithelial and capillary surface densities were estimated by intersection counting. The lengths of test lines transecting the barrier from epithelial surface to the nearest erythrocyte membrane were measured to estimate the harmonic mean thickness of the tissue-blood barrier (τhb), an index of resistance to diffusion. About 200–300 points or intersections were counted per grid (coefficient of variation <10%). Two EM grids per lobe were overlaid with a test grid (×1,000). The number of intercepts with single and double capillary profiles was systematically and completely counted.

The absolute volume and surface areas were obtained by relating the volume and surface densities through the levels to the volume of the lobe (10). The arithmetic mean septal thickness (τt), a measure of the mass of the tissue-blood barrier, is estimated from the volume (Vs) and surface area (Sa) of the alveolar septum:

| (5) |

Morphometric estimates of lung diffusing capacity for O2 (DlO2) were calculated using an established model (10, 25) that describes the diffusion path as serial conductance across the tissue-plasma barrier (DbO2) and capillary erythrocytes (DeO2):

| (6) |

Data Analysis

Measurements were normalized by body weight and expressed as means ± SD. The results from INF and DEF groups were compared by one-way ANOVA. Longitudinal HRCT data were compared by repeated-measures ANOVA. Whole lung morphometric results were derived from volume-weighted averages of individual lobes. Morphometric data from INF and DEF groups were also compared with published results (17) from the left lung of normal adult canines raised at sea level (n = 6). A post hoc test was performed using Fisher's protected least significant difference test. A P value of ≤0.05 was considered significant.

The overall increases in volumes and surface areas of major alveolar tissue components that could be attributable to lung expansion were estimated as:

| (7) |

RESULTS

HRCT

Acute effects of prosthesis deflation: Short-Term cohort.

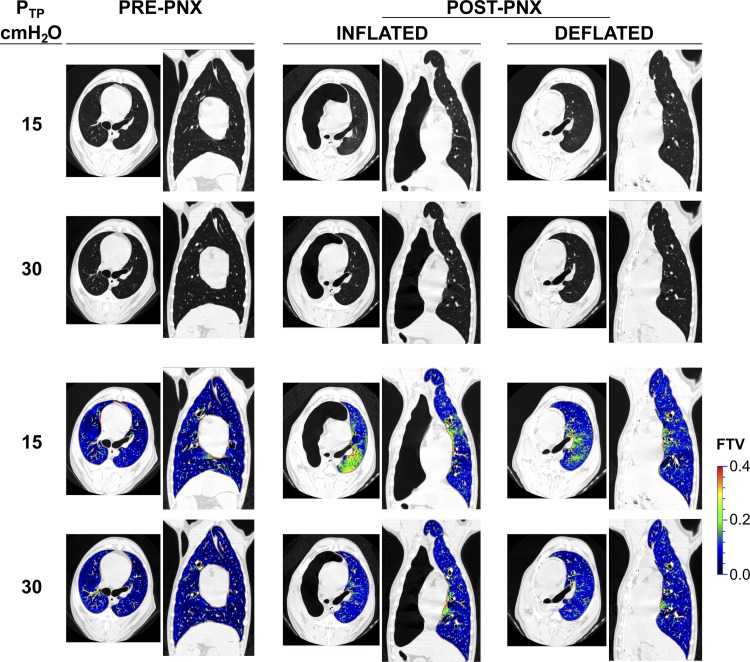

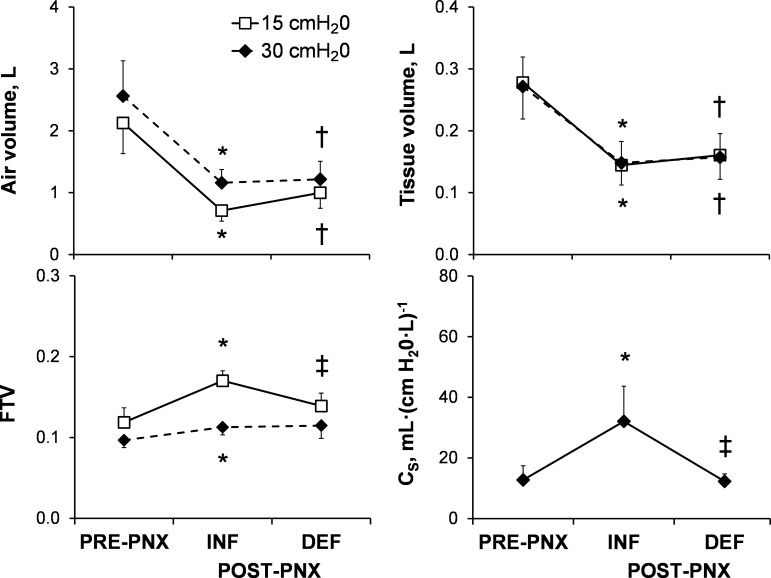

Representative axial and coronal images obtained at Ptp of 15 and 30 cmH2O from one animal are shown (Fig. 2). The inflated prosthesis prevented mediastinal shift and lateral expansion of the remaining lung. The remaining left lung became elongated in the cranio-caudal direction, a finding we quantified in an earlier study (26). As expected, post-PNX whole lung air and tissue volumes were 67 and 48% lower, respectively, than pre-PNX at Ptp = 15 cmH2O and 55 and 45% lower, respectively, at Ptp = 30 cmH2O (Fig. 3, top left and right). Immediately following acute deflation, air volume increased 40% at Ptp of 15 cmH2O and only 5% at 30 cmH2O, and tissue (+microvascular blood) volume did not change (at either inflation level). FTV decreased with lung inflation (from 15 to 30 cmH2O). Compared with pre-PNX, post-PNX FTV (INF group) was heterogeneously elevated particularly in the dependent lung zones at a lower lung volume (Ptp = 15 cmH2O); the elevation was less pronounced at total lung capacity (Ptp = 30 cmH2O; Fig. 2 and Fig. 3, bottom left). Thus the INF prosthesis relieved post-PNX lung distension at a given Ptp but caused redistribution of microvascular volume resulting in regional congestion at a low lung volume. Following acute deflation (DEF), gross mediastinal shift occurred immediately, associated with lateral enlargement of the remaining lung (Fig. 2) and partial normalization of FTV (Fig. 3, bottom left), indicating reversal of microvascular congestion. Specific compliance of the left lung increased post-PNX (INF) then normalized following prosthesis deflation (DEF; Fig. 3, bottom right).

Fig. 2.

Top 2 rows: representative axial and coronal high-resolution computed tomography (HRCT) images obtained at 2 transpulmonary pressures (15 and 30 cmH2O) from 1 animal are shown pre-PNX, post-PNX with INF prosthesis, and following DEF prosthesis. Bottom 2 rows: corresponding voxel-wise map of fractional tissue volume (FTV).

Fig. 3.

Acute changes in whole lung air volume, tissue volume, FTV, and specific compliance (Cs) were measured by HRCT at 2 transpulmonary pressures (15 and 30 cmH2O) pre-PNX and post-PNX with INF prosthesis (n = 6) and then on the same day after DEF prosthesis (n = 3) in the Short-Term Cohort. Data are means ± SD. *P ≤ 0.05 vs. pre-PNX by paired t-test; †P ≤ 0.05 vs. pre-PNX, and ‡P ≤ 0.05 vs. INF by unpaired t-test.

Chronic effects of prosthesis deflation: Long-Term Cohort.

Image analysis of HRCT-derived air and tissue volumes and FTV of each remaining lobe are shown in absolute values (Table 1) and as the volume ratio of each lobe with respect to its pre-PNX baseline (INF2/pre-PNX or DEF/pre-PNX; Table 2). From pre-PNX to ∼8 mo post-PNX (INF2), air and tissue volumes of the left lung increased 27 and 63%, respectively; the increase in tissue volume included a 47% increase in capillary blood volume that was separately measured by physiological methods (5). Approximately 4 mo following delayed deflation (∼8 mo post-PNX), air and tissue volumes increased a further 37 and 21%, respectively, resulting in total increases of 74 and 98%, respectively, with respect to the Pre-PNX left lung. These results are consistent with our previous findings based on indirect comparisons that preventing mediastinal shift does not completely abolish post-PNX lung expansion (26). Delayed lobar expansion was less pronounced and more uniform than immediate post-PNX lobar expansion in the absence of prosthesis (19). Overall, delayed lung expansion contributed ∼64 and 36% to the total in vivo post-PNX increases in HRCT-derived air and tissue-blood volumes, respectively.

Table 1.

HRCT data: Long-Term Cohort

| Post-PNX |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-PNX | INF2 | DEF | |

| Tissue volume, ml/kg | |||

| L cranial lobe | 1.34 ± 0.47 | 1.89 ± 0.39* | 2.23 ± 0.49* |

| L middle lobe | 0.72 ± 0.16 | 1.35 ± 0.24* | 1.62 ± 0.28* |

| L caudal lobe | 2.68 ± 0.31 | 4.46 ± 0.79* | 5.52 ± 1.12*† |

| L Lung | 4.73 ± 0.52 | 7.70 ± 1.15* | 9.37 ± 1.63*† |

| Air volume, ml/kg | |||

| L cranial lobe | 11.89 ± 2.61 | 12.62 ± 2.34 | 16.07 ± 2.21*† |

| L middle lobe | 7.79 ± 1.35 | 10.34 ± 1.82* | 14.20 ± 2.24*† |

| L caudal lobe | 20.76 ± 3.53 | 28.40 ± 3.53* | 40.14 ± 4.09*† |

| L lung | 40.44 ± 5.03 | 51.36 ± 4.14* | 70.41 ± 4.24*† |

| FTV | |||

| L cranial lobe | 0.100 ± 0.015 | 0.132 ± 0.025* | 0.122 ± 0.021 |

| L middle lobe | 0.085 ± 0.009 | 0.116 ± 0.014* | 0.103 ± 0.013* |

| L caudal lobe | 0.116 ± 0.014 | 0.136 ± 0.020* | 0.121 ± 0.019 |

| L lung | 0.105 ± 0.012 | 0.131 ± 0.019* | 0.117 ± 0.018 |

Values are means ± SD. HRCT, high-resolution computed tomography; PNX, pneumonectomy; INF, inflated; DEF, deflated; L, left; R, right; FTV, fractional tissue volume.

P ≤ 0.05 vs. pre-PNX;

P ≤ 0.05 vs. INF2 (∼8 mo post-PNX).

Table 2.

Contribution from deflation of prosthesis to total postPNX compensation estimated by HRCT (Long-Term Cohort)

| Ratio of Post-PNX to Pre-PNX |

Fraction of Total Change Post-PNX |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| INF2/PRE | DEF/PRE | Before deflation | After deflation | |

| Tissue and blood volume | ||||

| L cranial lobe | 1.42* | 1.67* | 0.63 | 0.37 |

| L middle lobe | 1.86* | 2.24*† | 0.69 | 0.31 |

| L caudal lobe | 1.67* | 2.06*† | 0.63 | 0.37 |

| L lung | 1.63* | 1.98*† | 0.64 | 0.36 |

| Air volume | ||||

| L cranial lobe | 1.06 | 1.35*† | 0.37 | 0.63 |

| L middle lobe | 1.33* | 1.82*† | 0.40 | 0.60 |

| L caudal lobe | 1.37* | 1.93*† | 0.39 | 0.61 |

| L lung | 1.27* | 1.74*† | 0.36 | 0.64 |

Values are means ± SD.

P ≤ 0.05 vs. pre-PNX;

P ≤ 0.05 vs. INF2 (∼8-mo post-PNX). Contribution to total post-PNX compensation before deflation = (INF2/PRE − 1)/(DEF/PRE − 1); after deflation = 1 − (contribution before deflation).

Morphometry

Terminal body weight was slightly (8–13%) lower in the DEF group than the INF2 and normal control groups (Table 3). Volumes of the fixed lung measured intact or postsectioning were 113 and 98% higher, respectively, in the DEF group compared with the normal lung, and 55 and 31% higher, respectively, compared with the INF2 group (Table 3). Following sectioning, lung volume declined 18% in the DEF group compared with 12% in normal and 3% in INF2 groups; the differences reflect residual elasticity of inflation-fixed lungs (27) and the relief of distending tissue stress at a given in vivo inflation pressure in the presence of the inflated prosthesis. Compared with normal left lung, acinar morphology shows septal crowding and smaller air space profiles in the INF group and enlarged profiles in the DEF group (Fig. 4). Morphometric hematocrit was similar among groups. The arithmetic septal thickness was higher post-PNX, reaching statistical significance in the DEF but not the INF group, while the harmonic mean thickness of the diffusion barrier was significantly elevated in both post-PNX groups. The prevalence of double capillary profile was 112% higher in both INF and DEF groups compared with control lungs, reflecting attempted post-PNX neocapillary formation (Table 3).

Table 3.

Morphometric data

| Normal | INF2 | DEF | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of animals | 6 | 3 | 6 |

| Terminal body weight, kg | 25.2 ± 2.8 | 23.9 ± 1.8 | 21.9 ± 3.0 |

| Total left lung volume, ml/kg | |||

| Intact (immersion method) | 26.8 ± 5.0 | 37.0 ± 4.8* | 57.2 ± 7.8*† |

| Sectioned (Cavalieri method) | 23.8 ± 2.7 | 35.9 ± 6.1* | 47.1 ± 8.1*† |

| Morphometric capillary hematocrit, % | 50.7 ± 1.5 | 49.7 ± 0.1 | 49.0 ± 1.7 |

| Arithmetic mean thickness of septum (τt), μm | 6.03 ± 0.36 | 6.51 ± 0.34 | 6.68 ± 0.30* |

| Harmonic mean thickness of blood-gas barrier (τhb), μm | 0.94 ± 0.05 | 1.06 ± 0.03* | 1.15 ± 0.09* |

| Double capillary profiles, %total profiles | 2.33 ± 0.26 | 4.95 ± 0.51* | 4.97 ± 0.51* |

Values are means ± SD.

P ≤ 0.05 vs. normal left lung;

P ≤ 0.05 vs. INF2 (∼12 mo post-PNX).

Fig. 4.

Representative micrographs show canine distal lung morphology in the Long-Term Cohort: normal, post-PNX with INF prosthesis, and post-PNX following DEF prosthesis. Bar = 200 μm.

The volume ratios of alveolar components with respect to lung volume were not different among groups, except that the volume-to-volume ratio of respiratory bronchioles in the INF group was significantly (21%) below normal (Table 4). Post-PNX surface-to-volume ratios of alveoli and capillaries were lower than normal, reaching statistical significance only for capillary surface-to-lung volume ratio but not alveolar surface-to-volume ratio (Table 4).

Table 4.

Volume-to-volume and surface-to-volume ratios of alveolar structures

| Normal | INF2 | DEF | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Volume per unit lung volume | |||

| Coarse parenchyma to lung | 0.8854 ± 0.0146 | 0.8874 ± 0.0154 | 0.8876 ± 0.0154 |

| Fine parenchyma to lung | 0.8708 ± 0.0136 | 0.8692 ± 0.0123 | 0.8687 ± 0.0180 |

| Alveolar sac | 0.6707 ± 0.0125 | 0.6504 ± 0.0200 | 0.6577 ± 0.0355 |

| Alveolar duct | 0.0723 ± 0.0122 | 0.0952 ± 0.0089 | 0.0896 ± 0.0219 |

| Respiratory bronchioles | 0.0330 ± 0.0041 | 0.0259 ± 0.0006 * | 0.0294 ± 0.0055 |

| Septum (tissue + blood) | 0.0948 ± 0.0087 | 0.0977 ± 0.0167 | 0.0920 ± 0.0044 |

| Total epithelium | 0.0166 ± 0.0023 | 0.0167 ± 0.0029 | 0.0159 ± 0.0005 |

| Type 1 epithelium | 0.0093 ± 0.0015 | 0.0089 ± 0.0017 | 0.0080 ± 0.0003 |

| Type 2 epithelium | 0.0074 ± 0.0009 | 0.0078 ± 0.0012 | 0.0080 ± 0.0005 |

| Interstitium | 0.0136 ± 0.0017 | 0.0146 ± 0.0035 | 0.0156 ± 0.0014 |

| Collagen fibers | 0.0106 ± 0.0015 | 0.0115 ± 0.0031 | 0.0127 ± 0.0009 |

| Cells and matrix | 0.0030 ± 0.0003 | 0.0031 ± 0.0006 | 0.0029 ± 0.0006 |

| Endothelium | 0.0097 ± 0.0008 | 0.0088 ± 0.0013 | 0.0095 ± 0.0007 |

| Septal extravascular tissue | 0.0399 ± 0.0044 | 0.0402 ± 0.0074 | 0.0411 ± 0.0018 |

| Capillary blood | 0.0549 ± 0.0045 | 0.0575 ± 0.0093 | 0.0510 ± 0.0028 |

| Surface area per unit lung volume, cm−1 | |||

| Alveolar surface | 317 ± 44 | 276 ± 26 | 275 ± 20 |

| Capillary surface | 334 ± 43 | 275 ± 8* | 272 ± 13* |

Values are means ± SD.

P ≤ 0.05 vs. normal left lung;

P ≤ 0.05 vs. INF2 (∼12 mo post-PNX).

Adjusting for the change in reference lung volume, the absolute volumes of coarse and fine parenchyma, respiratory bronchioles, alveolar ducts, and alveolar sacs were significantly higher in both post-PNX groups than in normal left lung and 27–52% higher in the DEF than the INF group (Table 5). Thus lung expansion and air space enlargement were seen in both post-PNX groups but more pronounced in the DEF group. Compared with INF group, total extravascular septal tissue volume was 33% higher in the DEF group due to higher volumes of type-2 epithelium (36%), interstitium (38%, primarily of collagen fibers), and endothelium (41%). Total alveolar-capillary surface areas were significantly elevated by ∼25 and 52–59% in the INF and DEF groups, respectively, compared with the normal left lung; the differences reached statistical significance only in the DEF group.

Table 5.

Absolute volumes, surface areas, and conductance for oxygen

| Normal | INF2 | DEF | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Absolute volume, ml/kg | |||

| Coarse parenchyma | 21.06 ± 2.21 | 31.78 ± 5.08* | 41.78 ± 7.15*† |

| Fine parenchyma | 20.71 ± 2.21 | 31.14 ± 5.04* | 40.87 ± 6.80*† |

| Alveolar sacs | 15.96 ± 1.75 | 23.28 ± 3.64* | 30.79 ± 3.97*† |

| Alveolar ducts | 1.72 ± 0.33 | 3.42 ± 0.70 | 4.34 ± 1.95* |

| Respiratory bronchioles | 0.78 ± 0.09 | 0.93 ± 0.15 | 1.42 ± 0.54* |

| Septum | 2.26 ± 0.34 | 3.52 ± 0.93* | 4.32 ± 0.65* |

| Total epithelium | 0.40 ± 0.07 | 0.60 ± 0.15* | 0.75 ± 0.13* |

| Type 1 epithelium | 0.22 ± 0.04 | 0.32 ± 0.08* | 0.38 ± 0.07* |

| Type 2 epithelium | 0.18 ± 0.03 | 0.28 ± 0.07* | 0.38 ± 0.07*† |

| Interstitium | 0.32 ± 0.06 | 0.53 ± 0.17* | 0.73 ± 0.08*† |

| Collagen fibers | 0.25 ± 0.05 | 0.42 ± 0.15* | 0.59 ± 0.07*† |

| Cells and matrix | 0.07 ± 0.01 | 0.11 ± 0.02* | 0.14 ± 0.02* |

| Endothelium | 0.23 ± 0.03 | 0.32 ± 0.09 | 0.45 ± 0.08*† |

| Septal extravascular tissue | 0.95 ± 0.16 | 1.45 ± 0.40* | 1.93 ± 0.28*† |

| Capillary blood | 1.31 ± 0.19 | 2.07 ± 0.53* | 2.39 ± 0.37* |

| Absolute surface area, m2/kg | |||

| Alveolar surface | 0.76 ± 0.15 | 0.95 ± 0.13 | 1.21 ± 0.13*† |

| Capillary surface | 0.79 ± 0.14 | 0.95 ± 0.20 | 1.20 ± 0.13* |

| Diffusing capacity for oxygen, ml· [min·mmHg·kg]−1 | |||

| Capillary blood (DeO2) | 4.94 ± 0.72 | 8.03 ± 2.04* | 9.28 ± 1.44* |

| Tissue-plasma barrier (DbO2) | 2.74 ± 0.57 | 2.94 ± 0.59 | 3.45 ± 0.50* |

| Lung (DlO2) | 1.76 ± 0.33 | 2.07 ± 0.42 | 2.47 ± 0.30* |

Values are means ± SD.

P ≤ 0.05, vs. normal left lung;

P ≤ 0.05 vs. INF2 (∼12 mo post-PNX).

Owing to the increase in left lung perfusion post-PNX, the estimated O2 conductance of capillary blood (DeO2) increased 62–88% above that in a normal left lung. Post-PNX conductance of the diffusion barrier (DbO2) was unchanged in the INF group but increased 26% in the DEF group. Overall O2 conductance of the lung (DlO2) increased 18 and 40% above normal in INF and DEF groups, respectively. These increases reached statistical significance only in the DEF group; differences between INF and DEF groups were not statistically significant (Table 5).

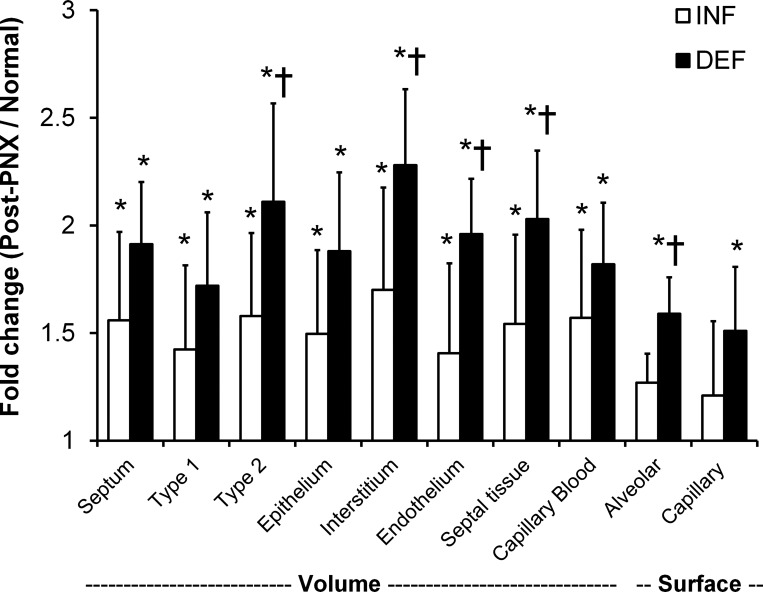

Changes in post-PNX volumes and surface areas were expressed as ratios to the respective mean values in the normal left lung (Fig. 5). These ratios were uniformly higher in the DEF than the INF group. Overall, delayed lung expansion explains up to 66% of the total post-PNX increase in lung volume, 35–77% of the increase in acinar air space volumes, 42–51% of the increase in the volumes of septal tissue components, ∼60% of the increases in alveolar-capillary surface areas, and 73 and 55% of the increases in diffusing capacities of the lung and the tissue-plasma barrier, respectively (Table 6).

Fig. 5.

In the Long-Term Cohort, the fold increases in the volume and surface area of alveolar septal components post-PNX with INF prosthesis or following DEF prosthesis are expressed as ratios to that in the normal left lung (post-PNX/normal). Volumes of type 1 and type 2 epithelium are shown separately and combined (labeled epithelium). Data are means ± SD. *P ≤ 0.05 vs. normal (1.0); †P ≤ 0.05 vs. INF by ANOVA.

Table 6.

Contribution from prosthesis deflation to total post-PNX compensation estimated by morphometry (Long-Term Cohort)

| Ratio |

Fraction of Total Change Post-PNX |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ratio | INF2/normal | DEF/normal | Before deflation | After deflation |

| Volumes | ||||

| Lung-intact | 1.38* | 2.13*† | 0.33 | 0.66 |

| Lung-sectioned | 1.51* | 1.98*† | 0.52 | 0.48 |

| Alveolar sacs | 1.46* | 1.93*† | 0.49 | 0.51 |

| Alveolar ducts | 1.99* | 2.52*† | 0.65 | 0.35 |

| Respiratory bronchioles | 1.19 | 1.82* | 0.23 | 0.77 |

| Septum | 1.56* | 1.91* | 0.61 | 0.39 |

| Total epithelium | 1.50* | 1.88* | 0.58 | 0.42 |

| Type 1 | 1.45* | 1.72* | 0.64 | 0.36 |

| Type 2 | 1.56* | 2.11*† | 0.53 | 0.47 |

| Interstitium | 1.66* | 2.28*† | 0.56 | 0.44 |

| Endothelium | 1.39* | 1.96*† | 0.49 | 0.51 |

| Extravascular tissue | 1.53* | 2.03*† | 0.55 | 0.45 |

| Capillary blood | 1.58* | 1.82* | 0.66 | 0.34 |

| Surface areas | ||||

| Alveolar surface | 1.25 | 1.59*† | 0.42 | 0.58 |

| Capillary surface | 1.20 | 1.52* | 0.38 | 0.62 |

| Diffusing capacity for oxygen | ||||

| Capillary blood (DeO2) | 1.63* | 1.88* | 0.72 | 0.28 |

| Tissue-plasma barrier (DbO2) | 1.07 | 1.26* | 0.27 | 0.73 |

| Lung (DlO2) | 1.18 | 1.40* | 0.45 | 0.55 |

Values are means ± SD.

P ≤ 0.05 vs. normal left lung;

P ≤ 0.05 vs. INF2 (∼12 mo post-PNX). Fractional contribution to total post-PNX compensation before deflation = (INF2/Normal − 1)/(DEF/Normal − 1); after deflation = 1 − (contribution before deflation).

DISCUSSION

Summary of the Results

We temporally separated the post-PNX effects related to an immediate and sustained increase in perfusion from those related to lung expansion, characterized their anatomical consequences, and estimated their relative contributions to structural adaptation in the remaining lung assessed in vivo by HRCT and ex vivo by morphometry. The customized INF prosthesis effectively prevented mediastinal shift and lateral expansion of the remaining lung while allowing modest lung expansion by elongation in the caudal direction. The INF prosthesis caused large (146%) immediate and reversible increases in specific lung compliance, with a 58% increase in capillary blood volume of the remaining lung, gross microvascular congestion on HRCT especially in dependent regions at low inflation, and significant long-term increases in the volumes of alveolar septal cells, matrix and collagen fibers. Of note, the INF group did not exhibit significant increases in the volume of respiratory bronchioles, gas exchange surface areas, or morphometric diffusing capacities of the tissue-plasma barrier and the lung. In contrast, delayed post-PNX prosthesis deflation was associated with further significant increases in lung volume as well as the volume and surface area of all major acinar structural parameters over the ensuing months. Overall, lateral lung expansion explains 60 and 48% of the post-PNX increase in total left lung volume assessed in vivo or ex vivo, respectively, ∼36% of the increase in in vivo tissue-blood volume, ∼45% of the increase in ex vivo septal extravascular tissue volume, ∼60% of the increases in alveolar-capillary surface areas, and 55–73% of the increases in the estimated morphometric diffusing capacities.

Critique of Methodology

Our findings in the INF2 group concur with that in an earlier series of studies (12, 15, 26): in the presence of post-PNX INF prosthesis, residual caudal expansion of the remaining lung occurred via displacement of the hemidiaphragm and, to a minor degree, expansion of the ipsilateral rib cage, supporting the existence of nonexpansion-related stimuli that compelled the lung to enlarge, grow, and remodel even in the absence of readily available space. In those earlier studies, the perfusion and expansion signals were not temporally separated (12, 15, 26), which precluded rigorous quantification of their respective contributions. The novel feature of the present study, delayed prosthesis deflation, addressed this deficiency and allowed partitioning of the separate signals. The number of animals was small, but the robustness of the data is evidenced by the agreement in the direction as well as magnitude of changes among corresponding estimates obtained by independent methods, physiology (5), imaging (Fig. 3 and Tables 1–2), and morphometry (Tables 3–6) and by the agreement in morphometric data between the INF groups in the present and the previous (12) cohorts, thereby demonstrating the consistency and reproducibility of the response.

Comparison of HRCT with Morphometry

Delayed lung expansion explains ∼60% of the post-PNX increase in total lung volume assessed antemortem by HRCT (Ptp = 30 cmH2O) and 66% of the increase in volume of the postmortem intact fixed lung (airway pressure = 25 cmH2O). Delayed lung expansion explains ∼36% of the increase in tissue (and microvascular blood) volume estimated by HRCT and 39% of the increase in volume of the alveolar septum (tissue + capillary blood) estimated by morphometry. These results demonstrate strong concordance between two independent techniques of estimation and further validate the use of HRCT in the noninvasive evaluation of functional lung growth.

Comparison with Physiological Compensation

The present results from structural analysis are in good agreement with those obtained by physiological assessment in the same animals (Long-Term Cohort) at rest and exercise (5). In this longitudinal physiologic study, resting end-expiratory lung volume was reduced by 55% post-PNX (INF prosthesis) compared with pre-PNX (both lungs) and then normalized following prosthesis deflation. Diffusing capacities of the lung and the membrane, pulmonary capillary blood volume, and gas exchange septal tissue volume were also reduced by ∼50% post-PNX (INF prosthesis group) then normalized completely or partially following prosthesis deflation. Similarly, exercise ventilation, O2 uptake, and CO2 output were 20–25% lower post-PNX with INF prosthesis compared with pre-PNX but normalized following prosthesis deflation. Exercise lung volumes were reduced by 25–37% post-PNX (INF prosthesis) and then increased ∼30% following deflation to near pre-PNX baseline. Exercise lung function parameters were consistently higher following prosthesis deflation than in simultaneous post-PNX animals with INF prosthesis. When expressed at a constant exercise pulmonary blood flow, DlCO increased in all post-PNX animals following prosthesis deflation but not in simultaneous control animals with INF prosthesis. Overall, delayed lung expansion explains ∼45% of the physiological compensation observed in the remaining lung. Thus there is good agreement between physiological and anatomical estimates of expansion- and perfusion-related responses, which affirms the respective estimated contributions of the in vivo signals as well as the robust structure-function correspondence in compensatory lung growth.

Lung Expansion and Tissue Mechanical Stress/Strain

Mechanical lung stress provides the signals for mechanotransduction. However, mechanical stress cannot be directly estimated without comprehensive knowledge of the constitutive properties of the lung. Instead, markers of tissue deformation (compliance, strain, and shear) serve as surrogates for lung stress. In previous studies of adult canine undergoing HRCT at two transpulmonary pressures, we segmented the lobes to calculate in vivo lobar compliance and applied nonrigid registration of corresponding anatomical features to quantify the magnitude and distribution of regional parenchyma strain as well as lobar shear distortion in orthogonal planes (29). Following extensive resection that removed ∼70% of total lung units, the remaining lobes expanded asymmetrically up to ∼3.5-fold of their original volumes, associated with heterogeneous increases in parenchyma strain and shear. After a 15-mo follow-up, there was a significant inverse relationship between the gain in tissue (including microvascular blood) volume and lobar strain measured during passive inflation, i.e., the lobes that gained more tissue volume postresection showed smaller increases in strain during inflation (28, 29). These findings are consistent with the conceptual model where suprathreshold expansion-related mechanical signals transduce tissue growth and remodeling, which in turn relieve mechanicals stress/strain in a feedback loop that continues until the regional mechanical signals decline below a critical threshold for transduction. Heterogeneity in the post-PNX increase and resolution of regional stress/strain could be advantageous in translational applications, because heterogeneity prolongs the time window during which mechanotransduction remains active at least in some lung regions, thereby rendering the innate signals for compensation susceptible to therapeutic intervention.

Perfusion and Mechanical Capillary Endothelial Stress

Post-PNX microvascular mechanical stress was evident from the more than twofold increase in perfusion to the left lung (5), and the 60–80% increase in resident pulmonary capillary blood volume at postmortem irrespective of whether the prosthesis was inflated or deflated. Both lung stretch and microvascular distention and/or shear stress induce the expression of angiogenic proteins and stimulate alveolar capillary growth (3). With increasing perfusion pressure, vascular wall strain is related to the ratio of the change in unit length or area to the original length (ΔL/L0) or area (ΔA/A0). The shear stress due to blood flow is the frictional force per unit of luminal endothelial surface area = 4 μQ̇/πr3, where μ is the dynamic viscosity, Q̇ is the volumetric flow rate, and r is the vessel radius. For a given radius, the change in shear magnitude is directly proportional to the change in blood flow. Regional microvascular stress/strain may be further modulated by regional ventilation. The endothelium of conducting vessels experiences greater shear stress from turbulent flow than the endothelium of alveolar capillaries where laminar flow predominates. Therefore, chronic capillary distension may be more relevant than fluid shear for stimulating alveolar microvascular adaptation, although these signals are difficult to isolate in vivo.

Increasing pulmonary blood pressure or flow recruits alveolar capillaries in complex, nonuniform patterns (2, 22). Increasing pulmonary perfusion by ligation of one pulmonary artery augments alveolar growth in newborn pig (7). In vitro stretch or fluid shear stress on human vascular endothelial cells induces a distinct set of genes including those associated with angiogenesis (6). In ovine congenital heart disease, increasing pulmonary blood flow enhances a proangiogenic gene expression profile that precedes the onset of pulmonary vascular remodeling (21). The endothelial cell mechanical signal is further amplified by reactive oxygen species generated via activation of NADPH oxidase to regulate numerous proteins that participate in cell proliferation, differentiation, apoptosis, and vascular remodeling (3). In addition, pulsatile perfusion upregulates endothelial nitric oxide (NO) production especially under hypoxic conditions (31), and endothelial NO synthase is a requisite signaling molecule for robust compensatory lung growth (16). Thus it is likely that the sustained post-PNX capillary distention and flow-related endothelial cell stress impose mechanotransduction signals above and beyond those imposed by expansion-related parenchymal deformation.

Summary and Implications

We conclude that separate signals related to lung expansion and microvascular perfusion contribute nearly equally to post-PNX structural compensation in the remaining lung. This conclusion based on imaging and morphometric assessment agrees with that obtained by independent physiological assessment in the same animals (5). A thorough understanding of the different in vivo stimuli is critical to any intervention aimed at initiating or amplifying the endogenous signaling cascade for lung regrowth. The need for a “signal-based” therapeutic approach is exemplified by pulmonary emphysema, a disease characterized by obliteration of distal lung units accompanied by a loss of mechanical stresses among the remaining units. The lack of relevant mechanical signals has thwarted many attempts to pharmacologically stimulate repair or growth in this disease. The effectiveness of procedures such as bullectomy, lung volume reduction surgery, endobronchial one-way valves or the instillation of sclerosing agents depends to a large extent upon ameliorating hyperinflation and improving mechanical interrelationships within and among the remaining lung units (4). Similar considerations extend to the emerging applications of cell-based therapy. Finding novel ways to appropriately restore, maintain, or augment parenchymal and microvascular mechanical signals will be a principal challenge in the quest for structural and functional restoration.

GRANTS

This work was supported by National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Grants RO1-HL-40070 and UO1-HL-111146. The contents of this article are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute or of the National Institutes of Health.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the author(s).

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Author contributions: P.R., C.Y., D.J.B., D.M.D., A.S.E., and C.C.H. performed experiments; P.R., C.Y., D.M.D., and C.C.H. analyzed data; P.R., C.Y., D.M.D., and C.C.H. interpreted results of experiments; P.R., C.Y., D.M.D., and C.C.H. prepared figures; P.R., C.Y., D.J.B., D.M.D., A.S.E., and C.C.H. approved final version of manuscript; C.C.H. conception and design of research; C.C.H. drafted manuscript; C.C.H. edited and revised manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We express our gratitude to our mentor, the late Dr. Robert L. Johnson, Jr. We appreciate the technical assistance of Jennifer Fehmel, Myresa Hurst, Corie Thorson, the veterinary assistance by the staff of the Animal Resources Center, and the imaging support by Greg Horton and the Dept. of Radiology.

Footnotes

This article is the topic of an Invited Editorial by Matthias Ochs (16a).

REFERENCES

- 1. American Thoracic Society Workshop Document Mechanisms and limits of induced postnatal lung growth. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 170: 319–343, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Baumgartner WA, Jr, Jaryszak EM, Peterson AJ, Presson RG, Jr, Wagner WW., Jr Heterogeneous capillary recruitment among adjoining alveoli. J Appl Physiol 95: 469–476, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Browning EA, Chatterjee S, Fisher AB. Stop the flow: a paradigm for cell signaling mediated by reactive oxygen species in the pulmonary endothelium. Annu Rev Physiol 74: 403–424, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Criner GJ, Mamary AJ. Lung volume reduction surgery and lung volume reduction in advanced emphysema: who and why? Semin Respir Crit Care Med 31: 348–364, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Dane DM, Yilmaz C, Estrera AS, Hsia CC. Separating in vivo mechanical stimuli for postpneumonectomy compensation: physiological assessment. J Appl Physiol 114: 99–106, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Dekker RJ, van Soest S, Fontijn RD, Salamanca S, de Groot PG, VanBavel E, Pannekoek H, Horrevoets AJ. Prolonged fluid shear stress induces a distinct set of endothelial cell genes, most specifically lung Kruppel-like factor (KLF2). Blood 100: 1689–1698, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Haworth SG, McKenzie SA, Fitzpatrick ML. Alveolar development after ligation of left pulmonary artery in newborn pig: clinical relevance to unilateral pulmonary artery. Thorax 36: 938–943, 1981 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Hsia CC. Signals and mechanisms of compensatory lung growth. J Appl Physiol 97: 1992–1998, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Hsia CC, Herazo LF, Ramanathan M, Johnson RL, Jr, Wagner PD. Cardiopulmonary adaptations to pneumonectomy in dogs. II. VA/Q relationships and microvascular recruitment. J Appl Physiol 74: 1299–1309, 1993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Hsia CC, Hyde DM, Ochs M, Weibel ER. An official research policy statement of the american thoracic society/european respiratory society: standards for quantitative assessment of lung structure. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 181: 394–418, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Hsia CC, Johnson RL, Jr, Wu EY, Estrera AS, Wagner H, Wagner PD. Reducing lung strain after pneumonectomy impairs oxygen diffusing capacity but not ventilation-perfusion matching. J Appl Physiol 95: 1370–1378, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Hsia CC, Wu EY, Wagner E, Weibel ER. Preventing mediastinal shift after pneumonectomy impairs regenerative alveolar tissue growth. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 281: L1279–L1287, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Hsia CCW, Herazo LF, Fryder-Doffey F, Weibel ER. Compensatory lung growth occurs in adult dogs after right pneumonectomy. J Clin Invest 94: 405–412, 1994 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Hsia CCW, Herazo LF, Johnson RL., Jr Cardiopulmonary adaptations to pneumonectomy in dogs. I. Maximal exercise performance. J Appl Physiol 73: 362–367, 1992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Hsia CCW, Johnson RL, Jr, Wu EY, Estrera AS, Wagner H, Wagner PD. Reducing lung strain after pneumonectomy impairs diffusing capacity but not ventilation-perfusion matching. J Appl Physiol 95: 1370–1378, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Leuwerke SM, Kaza AK, Tribble CG, Kron IL, Laubach VE. Inhibition of compensatory lung growth in endothelial nitric oxide synthase-deficient mice. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 282: L1272–L1278, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16a. Ochs M. Rebuilding the lung: signals for a complex architectural task. J Appl Physiol; doi:10.1152/japplphysiol.00215.2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Ravikumar P, Bellotto DJ, Johnson RL, Jr, Hsia CC. Permanent alveolar remodeling in canine lung induced by high-altitude residence during maturation. J Appl Physiol 107: 1911–1917, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Ravikumar P, Dane DM, McDonough P, Yilmaz C, Estrera AS, Hsia CC. Long-term post-pneumonectomy pulmonary adaptation following all-trans-retinoic acid supplementation. J Appl Physiol 110: 764–773, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Ravikumar P, Yilmaz C, Dane DM, Johnson RL, Jr, Estrera AS, Hsia CC. Regional lung growth following pneumonectomy assessed by computed tomography. J Appl Physiol 97: 1567–1574; discussion 1549, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Ravikumar P, Yilmaz C, Dane DM, Johnson RL, Jr, Estrera AS, Hsia CC. Developmental signals do not further accentuate nonuniform postpneumonectomy compensatory lung growth. J Appl Physiol 102: 1170–1177, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Tian J, Fratz S, Hou Y, Lu Q, Gorlach A, Hess J, Schreiber C, Datar SA, Oishi P, Nechtman J, Podolsky R, She JX, Fineman JR, Black SM. Delineating the angiogenic gene expression profile before pulmonary vascular remodeling in a lamb model of congenital heart disease. Physiol Genomics 43: 87–98, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Wagner WW, Jr, Todoran TM, Tanabe N, Wagner TM, Tanner JA, Glenny RW, Presson RG., Jr Pulmonary capillary perfusion: intra-alveolar fractal patterns and interalveolar independence. J Appl Physiol 86: 825–831, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Weibel ER. Morphometric and stereological methods in respiratory physiology, including fixation techniques. In: Techniques in the Life Sciences, Respiratory Physiology, edited by Otis AB. Kusterdingen, Ireland: Elsevier, 1984, p. 1–35 [Google Scholar]

- 24. Weibel ER. What makes a good lung? Swiss Med Wkly 139: 375–386, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Weibel ER, Federspiel WJ, Fryder-Doffey F, Hsia CCW, König M, Stalder-Navarro V, Vock R. Morphometric model for pulmonary diffusing capacity. I. Membrane diffusing capacity. Respir Physiol 93: 125–149, 1993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Wu EY, Hsia CC, Estrera AS, Epstein RH, Ramanathan M, Johnson RL., Jr Preventing mediastinal shift after pneumonectomy does not abolish physiologic compensation. J Appl Physiol 89: 182–191, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Yan X, Polo Carbayo JJ, Weibel ER, Hsia CC. Variation of lung volume after fixation when measured by immersion or Cavalieri method. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 284: L242–L245, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Yilmaz C, Ravikumar P, Dane DM, Bellotto DJ, Johnson RL, Jr, Hsia CC. Noninvasive quantification of heterogeneous lung growth following extensive lung resection by high-resolution computed tomography. J Appl Physiol 107: 1569–1578, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Yilmaz C, Tustison NJ, Dane DM, Ravikumar P, Takahashi M, Gee JC, Hsia CC. Progressive adaptation in regional parenchyma mechanics following extensive lung resection assessed by functional computed tomography. J Appl Physiol 111: 1150–1158, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Zhang Q, Bellotto DJ, Ravikumar P, Moe OW, Hogg RT, Hogg DC, Estrera AS, Johnson RL, Jr, Hsia CC. Postpneumonectomy lung expansion elicits hypoxia-inducible factor-1alpha signaling. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 293: L497–L504, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Zhao F, Sellgren K, Ma T. Low-oxygen pretreatment enhances endothelial cell growth and retention under shear stress. Tissue Eng Part C Methods 15: 135–146, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]