Abstract

Although systemic inflammation occurs in most pathological conditions that challenge the neural control of breathing, little is known concerning the impact of inflammation on respiratory motor plasticity. Here, we tested the hypothesis that low-grade systemic inflammation induced by lipopolysaccharide (LPS, 100 μg/kg ip; 3 and 24 h postinjection) elicits spinal inflammatory gene expression and attenuates a form of spinal, respiratory motor plasticity: phrenic long-term facilitation (pLTF) induced by acute intermittent hypoxia (AIH; 3, 5 min hypoxic episodes, 5 min intervals). pLTF was abolished 3 h (vehicle control: 67.1 ± 27.9% baseline; LPS: 3.7 ± 4.2%) and 24 h post-LPS injection (vehicle: 58.3 ± 17.1% baseline; LPS: 3.5 ± 4.3%). Pretreatment with the nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug ketoprofen (12.5 mg/kg ip) restored pLTF 24 h post-LPS (55.1 ± 12.3%). LPS increased inflammatory gene expression in the spleen and cervical spinal cord (homogenates and isolated microglia) 3 h postinjection; however, all molecules assessed had returned to baseline by 24 h postinjection. At 3 h post-LPS, cervical spinal iNOS and COX-2 mRNA were differentially increased in microglia and homogenates, suggesting differential contributions from spinal cells. Thus LPS-induced systemic inflammation impairs AIH-induced pLTF, even after measured inflammatory genes returned to normal. Since ketoprofen restores pLTF even without detectable inflammatory gene expression, “downstream” inflammatory molecules most likely impair pLTF. These findings have important implications for many disease states where acute systemic inflammation may undermine the capacity for compensatory respiratory plasticity.

Keywords: spinal cord, inflammation, plasticity, respiratory motor neuron, microglia, inflammatory genes

systemic inflammation occurs in most clinical disorders that challenge the neural control of breathing, including chronic obstructive lung disease (6, 60, 70); traumatic, ischemic, and degenerative neural disorders (e.g., spinal injury, motor neuron disease) (1, 46, 63); and sleep-disordered breathing (7, 24, 33). Although inflammation affects many neural functions (18), the impact of inflammation on the neural system controlling breathing has seldom been studied. Because of the importance of ventilatory control in many clinical disorders, it is essential to understand connections between inflammation and essential processes of ventilatory control, including rhythm generation, chemoreception, and plasticity (19, 41). In this study we focus on the impact of inflammation on an important model of respiratory plasticity, phrenic long-term facilitation following acute intermittent hypoxia (AIH).

Neuroinflammation involves complex spatial and temporal patterns of inflammatory gene expression (reviewed in 40). In the central nervous system (CNS), resident microglia are major contributors to the inflammatory response and are activated by many pathological stimuli. Upon activation, microglia change shape from stellate, ramified cells to an amoeboid shape (35) and begin to release proinflammatory and anti-inflammatory molecules (e.g., cytokines, nitric oxide, prostaglandins, and growth/trophic factors) (25). The influence of microglial inflammation on respiratory plasticity is the focus of the present study.

Systemic administration of the bacterial endotoxin lipopolysaccharide (LPS) decreases baseline ventilation and ventilatory responses to chemoreceptor stimulation in unanesthetized rats (29). These effects are reversed by pretreatment with the nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug ketoprofen, (29). LPS is a toll-like receptor ligand frequently used to study systemic inflammation (48). Although LPS does not cross the blood-brain barrier (49, 58), it elicits CNS inflammation via systemic release of cytokines (which do cross the blood-brain barrier) or vagal transmission (9, 23, 36, 39, 52, 55). Systemic LPS administration impairs hippocampal synaptic plasticity, as well as learning and memory (18). Similarly, systemic LPS impairs an important model of spinal respiratory plasticity: AIH-induced phrenic long-term facilitation (pLTF) (29, 67). In the earlier study of Vinit et al. (67), 1) spinal inflammation was not confirmed, 2) only high LPS doses (3 mg/kg) and a short time interval (3 h) were studied, and 3) causality between LPS-induced inflammation and pLTF impairment was not investigated. Here, we extend the results of Vinit et al. (67) by testing the hypotheses that 1) low LPS doses impair pLTF at longer intervals postadministration (24 h), 2) systemic LPS increases inflammatory gene expression in isolated microglia and homogenates from the cervical spinal cord (a critical region for pLTF), and 3) the nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug ketoprofen restores pLTF following LPS administration. Our results support the hypothesis that systemic inflammation impairs spinal respiratory plasticity and demonstrate that systemic inflammation associated with many clinical disorders is of considerable relevance to the central neural control of breathing.

METHODS

All experiments were approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee in the School of Veterinary Medicine, University of Wisconsin, and conformed to policies laid out by the National Institutes of Health in the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. Experiments were performed on 3- to 4-mo-old Harlan male Sprague-Dawley rats (colony 218a). Rats were housed under standard conditions, with a 12:12-h light/dark cycle with food and water ad libitum.

Drugs and Materials

LPS (E. coli 0111:B4), (S)-(+)-ketoprofen, and Tri Reagent were purchased from Sigma Chemical (St. Louis, MO). M-MLV Reverse Transcriptase was purchased from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA). Oligo(dT), Random hexamer, and RNAsin were purchased from Promega (Madison, WI). SYBR Green PCR Master Mix was purchased from Applied Biosystems (Carlsbad, CA).

Experimental Groups

To investigate the effects of systemic inflammation, rats received an intraperitoneal (ip) injection of LPS (100 μg/kg) or vehicle (saline) 3 or 24 h prior to beginning an experiment. Rats were either used for electrophysiological experiments to study AIH-induced pLTF or for measurements of inflammatory gene expression. In the latter groups, intra-aortic saline perfusions were used to remove circulating myeloid cells before cervical spinal tissues were harvested. Prior to perfusions, the spleen was harvested for analysis.

In 24 h LPS or 24 h vehicle rats, the nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug ketoprofen (12.5 mg/kg ip) or vehicle (50% ethanol in saline) was injected 3 h prior to a pLTF experiment. Ketoprofen is a potent inhibitor of inflammatory activities since it directly inhibits cyclooxygenase (31, 65, 68) and the transcription factor nuclear factor kappa B (NF-κB) (65), a key regulator of multiple inflammatory genes (42, 51).

In specific, rats used for electrophysiology experiments after 3 h of LPS fell into one of three groups: 1) time control (includes both vehicle and LPS injected), 2) vehicle + AIH, or 3) LPS (3 h) + AIH. A separate set of rats was used to examine the effects of 24 h of LPS and fell into one of five groups: 1) time control (includes vehicle, LPS, ketoprofen, or LPS + ketoprofen injected); 2) LPS (24 h), ketoprofen + AIH; 3) LPS (24 h), vehicle + AIH; 4) vehicle (24 h), ketoprofen + AIH; and 5) vehicle + AIH.

For gene expression, rats were in comparable groups as those above for the electrophysiology. Rats were in either LPS (3 h), vehicle (3 h), LPS (24 h) + ketoprofen, LPS (24 h) + vehicle, vehicle (24 h) + ketoprofen, or vehicle groups. The rats used for gene expression analysis were not given AIH, neglecting the need for a time control group.

Electrophysiological Experiments

The protocol used in electrophysiological experiments has been described in detail previously (2, 5). In brief, rats were anesthetized with isoflurane, tracheotomized, and pump ventilated (Small Animal Ventilator 683, Harvard Apparatus, Holliston, MA). Rats were maintained with isoflurane for the remainder of the surgical preparation; after surgical preparations were complete, the rats were slowly converted to urethane anesthesia (1.8 g/kg iv, Sigma-Aldrich). During the 1-h stabilization period after conversion to urethane, pancuronium bromide (1 mg iv), was given to paralyze the rats. The rats were tracheotomized and ventilated. Anesthetic level was assessed throughout experiments by monitoring blood pressure and phrenic nerve responses to toe pinch. Approximately 1 h after beginning surgical procedures, an intravenous infusion of 1.5–2 ml/h began with a solution consisting of Hetastarch (0.3%) and sodium bicarbonate (0.84%) in lactated Ringer's. The infusion rate was adjusted to maintain blood volume, pressure, and acid-base balance.

Surgical preparation.

Both vagi were isolated and cut, and a catheter was inserted into the right femoral artery to enable blood pressure measurements and arterial blood samples. Blood samples were analyzed for Po2, Pco2, pH, and base excess using a blood gas analyzer (ABL 800, Radiometer, Copenhagen, Denmark). Blood samples (62.5 μl in heparinized plastic catheter) were drawn before (baseline), during the first hypoxic episode, and 15, 30 and 60 min post-AIH. A rectal temperature probe was used to monitor and regulate body temperature throughout an experiment.

The left phrenic nerve was isolated with a dorsal approach, cut caudally, desheathed, and placed on a bipolar silver recording electrode submerged in mineral oil. Nerve activity was amplified (gain X10K), bandpass filtered (300 Hz to 20 kHz) (A-M Systems, Carlsberg, WA), and integrated (absolute value, Powerlabs 830, AD Instruments, Colorado Springs, CO, time constant 100 ms). The signal was digitized, recorded, and analyzed using Powerlabs 830 (version 7.2.2, AD Instruments).

Protocol.

Baseline nerve activity was established with FIO2 ∼0.56 (PaO2 > 300 mmHg) and CO2 added to the inspired gas (balance nitrogen). The CO2 apneic threshold was determined by progressively lowering inspired CO2 until phrenic nerve activity ceased. Inspired CO2 was slowly increased until phrenic nerve activity resumed (recruitment threshold). End-tidal CO2 was then set 3 mmHg above the recruitment threshold to establish baseline nerve activity. End-tidal CO2 was monitored and maintained throughout an experiment using a flow-through capnograph (Respironics, Andover, MA).

Once phrenic nerve activity was stable, an arterial blood sample was taken to establish baseline conditions; these conditions were maintained throughout the experiment. After baseline conditions, an AIH protocol began consisting of three hypoxic episodes (5 min duration, 10.5% O2), separated by 5 min of normoxia. Blood samples were taken during the first hypoxic episode and 15, 30, and 60 min post-AIH. Data were included in analysis only if they complied with the following criteria: 1) PaO2 during baseline and post-AIH was >180 mmHg; 2) PaO2 during hypoxic episodes was between 35 and 45 mmHg; 3) PaCO2 remained within 1.5 mmHg of baseline throughout the post-AIH period. Phrenic nerve amplitude and frequency were evaluated for 1 min before each blood sample. Upon completion of the experiment, rats were euthanized with an overdose of urethane.

Inflammatory Gene Expression

Sample preparation.

Tissue from cervical spinal cords was homogenized and used for quantitative PCR analysis (hereafter referred to as “homogenates”). Cervical spinal tissue was also used to isolate microglia by using antibodies for the microglial marker CD11b+ conjugated to magnetic beads, as previously reported (15). To isolate microglia, these labeled cells were passed through MS columns according to a modified Miltenyi MACS protocol (43). The average purity of cells with microglia-like characteristics was >95% as determined by flow cytometry FSC/SSC scatter analysis and CD11b+/CD45low staining (43). These results are consistent with previous findings (15, 56). From here on, CD11b+ cells isolated with this method are referred to as “microglia.”

Reverse transcription.

Total RNA was isolated from cervical spinal cord microglia or homogenates using the TRI-reagent according to the manufacturer's instructions. First-strand cDNA was synthesized from 1 μg of total RNA using M-MLV Reverse Transcriptase and an oligo(dT)/random hexamer cocktail. The cDNA was then used for quantitative RT-PCR using SYBR Green PCR Master Mix.

Quantitative PCR.

Amplified cDNA was measured by fluorescence in real time using the StepOnePlus Real-Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems). The following primer sequences were used for quantitative PCR: iNOS, 5′-AGG GAG TGT TGT TCC AGG TG and 5′-TCT GCA GGA TGT CTT GAA CG; COX-2, 5′-TGT TCC AAC CCA TGT CAA AA and 5′-CGT AGA ATC CAG TCC GGG TA; IL-1β, 5′-CTG CAG ATG CAA TGG AAA GA and 5′-TTG CTT CCA AGG CAG ACT TT; TNF-α, 5′-TCC ATG GCC CAG ACC CTC ACA C and 5′-TCC GCT TGG TGG TTT GCT ACG; IL-6, 5′-GTG GCT AAG GAC CAA GAC CA and 5′-GGT TTG CCG AGT AGA CCT CA; and 18s, 5′-CGG GTG CTC TTA GCT GAG TGT CCC G and 5′-CTC GGG CCT GCT TTG AAC AC.

All primers were designed to span introns whenever possible. Primer specificity was assessed through NCBI BLAST analysis prior to use, and all dissociation curves had a single peak with an observed melting temperature consistent with the intended amplicon sequences. Primer efficiency was calculated through the use of serial dilutions and construction of a standard curve.

Data Analysis

Electrophysiology.

Peak amplitude and frequency (bursts/min) of integrated phrenic nerve activity were averaged for 30 bursts at each recorded point. Changes in phrenic nerve burst amplitude were normalized to baseline values (i.e., percent change from baseline), and burst frequency was reported as a change from baseline frequency (bursts/min). In this study, physiological variables and phrenic amplitude are reported for baseline, during the short-term hypoxic response, and the 60 min time point only.

Statistical comparisons for the hypoxic responses were made from data at minute 2 of the 5 min during the first hypoxic episode using a t-test (3 h LPS data) or one-way ANOVAs on ranks (24 h LPS data). Owing to the addition of two ketoprofen groups, an ANOVA on ranks was used for the 24 LPS hypoxic data to permit appropriate statistical comparisons. Nonparametric analyses were used when data failed normality or equal variance.

Statistical comparisons for changes in phrenic burst amplitude after AIH were made using a repeated-measures two-way ANOVA with Tukey post hoc test to identify individual differences (Sigma Stat version 11, Systat Software, San Jose, CA). Differences were considered significant if P < 0.05. All values are expressed as means ± SE.

Gene expression.

Gene expression data were analyzed based on a relative standard curve method, as specified by Applied Biosystems. In brief, all samples were run in duplicate, averaged, and interpolated onto previously run standard curves for each primer set to account for differences in primer efficiency. Values were then normalized to 18S for each sample and expressed relative to vehicle controls for each gene, reflecting the fold change for each gene. If the normalized gene expression data for an individual sample is greater than 2 standard deviations from the mean, the sample was excluded as an outlier. Statistical analysis for TNFα and IL-1β were run on the fold change data. Statistical analysis on iNOS, COX-2, and IL-6 failed equal variance and/or normality tests; therefore data were transformed logarithmically before statistical analysis, but data are still reported as fold changes (see Fig. 4). Statistical significance was determined for each inflammatory gene examined in the spleen by a one-way ANOVA with Tukey post hoc test for individual comparisons. For cervical spinal data, statistical significance was determined using a two-way ANOVA with Tukey post hoc test (Sigma Stat version 11, Systat Software, San Jose, CA). Differences were considered significant if P < 0.05. All values are expressed as means ± SE.

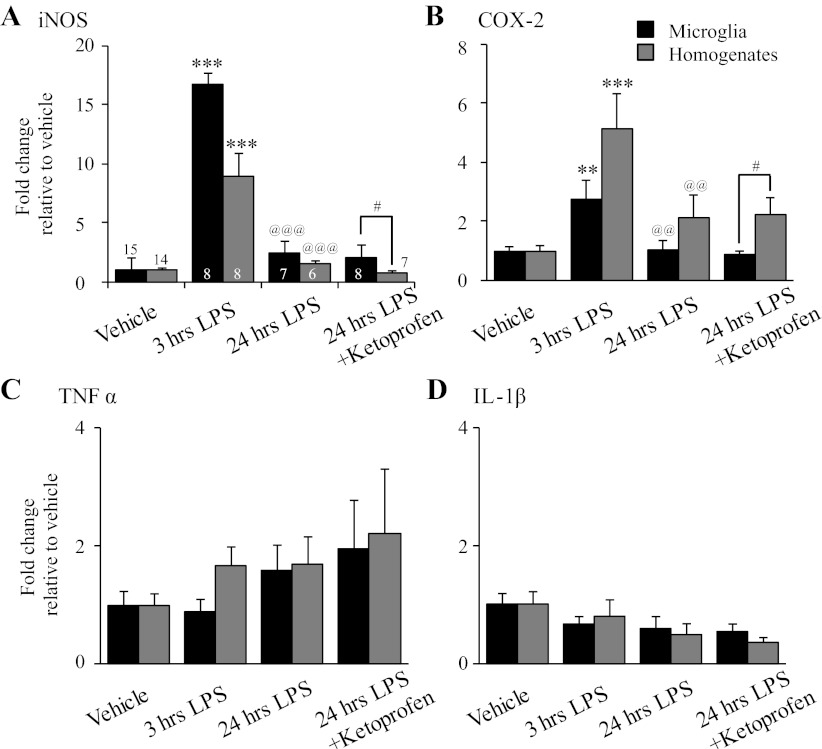

Fig. 4.

Systemic inflammation evoked by LPS (100 μg/kg ip) caused transient and differential changes in inflammatory gene expression in isolated microglia (black bars) and homogenates (gray bars) from the cervical spinal cord. A: treatment with LPS (3 h) increased mRNA for iNOS compared with vehicle (microglia n = 15, homogenates n = 14) in both microglia (n = 8) and homogenate (n = 8) samples. Expression of iNOS was reduced 24 h post-LPS (microglia n = 7, homogenates n = 6) compared with 3 h post-LPS in both sample types but was not changed relative to vehicle. After ketoprofen (12.5 mg/kg ip, 3 h), microglia had greater iNOS gene expression (n = 8) compared with homogenates (n = 7). B: treatment with LPS (3 h) increased COX-2 mRNA in both microglia (n = 7) and homogenate (n = 8) compared with vehicle (microglia n = 15, homogenates n = 15), but was reduced 24 h post-LPS. LPS (24 h) alone (microglia n = 7, homogenates n = 6) or with ketoprofen (microglia n = 8, homogenates n = 7) did not alter COX-2 mRNA in either microglia or homogenates compared with vehicle. After ketoprofen treatment, microglia had less COX-2 mRNA compared with homogenates. LPS treatment (3 or 24 h) had no effect on gene expression for TNFα (C) or IL-1β (D). **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, significant difference from vehicle; @@P < 0.01, @@@P < 0.001, significant difference from 3 h LPS; #P < 0.05, significant difference between microglia and homogenate samples.

RESULTS

Impaired pLTF 3 h post-LPS.

Acute LPS (3 h; 100 μg/kg ip) had only minor effects on physiological variables measured (Table 1). Rats treated with LPS had no significant differences in temperature, PaCO2, or pH within or between groups. However, LPS rats had significantly lower PaO2 and mean arterial pressure (MAP) after AIH vs. time controls but were not different from their respective baseline values. LPS-treated rats were not significantly different from vehicle-treated rats in any variable examined. In LPS- and vehicle-treated rats subjected to AIH, PaO2 significantly decreased during hypoxic episodes, with a concurrent decrease in MAP; no similar changes were noted in time control rats without AIH.

Table 1.

Physiological parameters for Sprague-Dawley rats during electrophysiological experiments after 3 h of LPS

| Temperature |

PaO2 |

PaCO2 |

pH |

MAP |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Time | Treatment Group | Mean | SE | Mean | SE | Mean | SE | Mean | SE | Mean | SE |

| Baseline | 3 h Time control | 37.5 | 0.1 | 351.8 | 6.7 | 45.8 | 1.3 | 7.362 | 0.008 | 132.5 | 3.9 |

| 3 h Vehicle | 37.7 | 0.1 | 331.25 | 14.1 | 47.6 | 1.4 | 7.356 | 0.006 | 128.2 | 2.8 | |

| 3 h LPS | 37.5 | 0.3 | 351.2 | 3.7 | 47.0 | 0.7 | 7.353 | 0.013 | 125.4 | 3.9 | |

| Hx | 3 h Time control | 37.5 | 0.1 | 349.4 | 7.4a | 45.8 | 1.8 | 7.360 | 0.008 | 137.6 | 3.8d |

| 3 h Vehicle | 37.4 | 0.1 | 38.5 | 2.7c | 48.5 | 1.0 | 7.338 | 0.008 | 87.3 | 5.1c | |

| 3 h LPS | 37.3 | 0.2 | 41.5 | 2.6c | 48.9 | 1.0 | 7.336 | 0.010 | 75.6 | 9.1c | |

| 60 min | 3 h Time control | 37.7 | 0.02 | 347.4 | 3.7 | 45.4 | 1.7 | 7.375 | 0.008 | 130.1 | 2.8e |

| 3 h Vehicle | 37.8 | 0.1 | 312.8 | 20.4bb | 48.4 | 1.3 | 7.365 | 0.015 | 117.6 | 6.2 | |

| 3 h LPS | 37.8 | 0.1 | 317.6 | 6.9b | 47.1 | 0.9 | 7.364 | 0.022 | 111.9 | 3.7 | |

Temperatures are in °C; PaO2, PaCO2, and MAP are in mmHg. There were no significant differences within or between groups in temperature, PaCO2, or pH.

P < 0.001, significant difference from all other hypoxia (Hx) groups.

P < 0.05, significant difference from time control within 60 min.

P < 0.01, significant difference from time control within 60 min.

P < 0.001, significant difference from all other within group.

P < 0.001, significant difference from all other groups in Hx.

P < 0.05, significant difference from LPS.

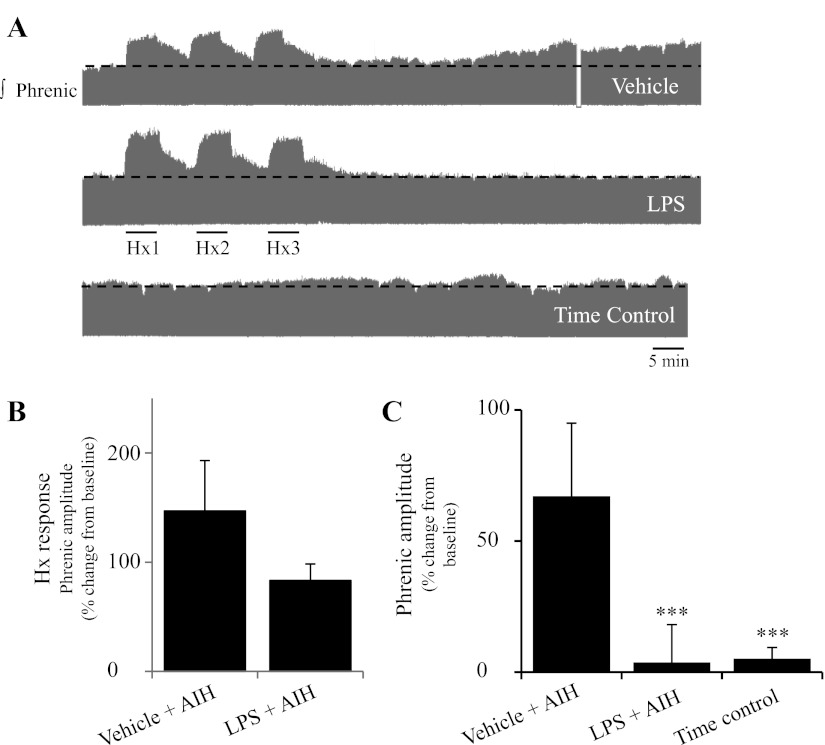

LPS did not reduce phrenic nerve burst amplitude during hypoxia, nor did it change frequency at any time during experiments. The short-term hypoxic phrenic response (the immediate increase in phrenic nerve amplitude in response to decreased oxygen) was not significantly affected by LPS (vehicle: 147 ± 46% baseline; LPS-treated: 83 ± 15%; P = 0.261; t-test, Fig. 1B). Baseline phrenic burst frequency was 39 ± 2 bursts/min in the vehicle group, 43 ± 3 bursts/min in the LPS group, and 43 ± 2 bursts/min in the time control group. Similarly, there were no significant changes in frequency responses during hypoxia (vehicle: 10.0 ± 2.0 burst/min; LPS: 12.8 ± 2.8 bursts/min; P = 0.453; t-test) or following AIH (vehicle: 1.0 ± 2.0 bursts/min at 60 min post-AIH, LPS: 5.5 ± 2.4 bursts/min; time control: -1.9 ± 1.6 bursts/min; data not shown).

Fig. 1.

Systemic inflammation (3 h) induced by LPS (100 μg/kg ip) significantly reduced acute intermittent hypoxia (AIH)-induced phrenic long-term facilitation (pLTF). A: representative integrated phrenic neurograms from anesthetized rats during the AIH (3 × 5 min hypoxia: Hx1, Hx2, Hx3) protocol for a vehicle-injected (saline, top trace), or LPS-injected (middle trace), or time control (no AIH, bottom trace) rats. Black dashed line indicates baseline phrenic amplitude in each trace. Development of pLTF is evident as a progressive increase in phrenic nerve amplitude over 60 min in the vehicle-injected animal. B: no change in the short-term hypoxia response was evident. C: group data for vehicle-injected AIH (n = 5), LPS-injected AIH (n = 5), and time control (n = 5) demonstrating a significant reduction in the magnitude of pLTF 60 min post-AIH in LPS treated and time control rats (***P < 0.001 repeated-measures two-way ANOVA, Tukey post hoc test).

Acute LPS significantly diminished pLTF magnitude vs. vehicle controls (vehicle: 67.1 ± 27.9% baseline, n = 5; LPS: 3.7 ± 4.2% baseline, n = 5; Fig. 1C; P < 0.001; repeated-measures two-way ANOVA, Tukey post hoc test). There was no significant difference between LPS-treated and time control rats (5.1 ± 4.3%, n = 5). Thus this low LPS dose (100 μg/kg) abolishes pLTF shortly after administration (3 h), similar to previous findings with a higher LPS dose (3 mg/kg) (67). Neither this dose (3 mg/kg) nor that of Vinit et al. (67) caused overt sickness behaviors in rats (increased temperature, lethargy). Higher LPS doses are used to simulate sepsis, and overt sickness behaviors can be observed (37, 45).

pLTF remains impaired 24 h post-LPS.

Because inflammation initiates complex signaling cascades that can persist well beyond 3 h, we examined pLTF 24 h post-LPS injection. Since no significant differences were found in pLTF among the various time control groups (vehicle, LPS, ketoprofen, or LPS + ketoprofen), we combined these groups for further analysis. Further, rats treated with LPS + ketoprofen vehicle were combined with the LPS alone group since ketoprofen vehicle had no significant effects and are referred to as 24 h LPS.

Similar to 3 h post-LPS, only minor differences were observed in physiological variables 24 h post-LPS (Table 2). There were no significant differences within or between groups for temperature, PaCO2, or pH. LPS-injected rats had higher MAP levels vs. vehicle-injected rats at baseline, during hypoxia, and after AIH, although neither group differed significantly from time control rats at baseline or post-AIH. LPS-treated rats also had higher MAP compared with rats treated with ketoprofen (without LPS) post-AIH. All treatment groups showed a significant drop in PaO2 and MAP during hypoxia, as expected.

Table 2.

Physiological parameters for Sprague-Dawley rats during electrophysiological experiments 24 h after LPS

| Temperature |

PaO2 |

PaCO2 |

pH |

MAP |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Time | Treatment Group | Mean | SE | Mean | SE | Mean | SE | Mean | SE | Mean | SE |

| Baseline | 24 h Time control | 37.5 | 0.2 | 335.7 | 7.4 | 45.0 | 0.9 | 7.334 | 0.011 | 130.6 | 6.0 |

| 24 h Vehicle | 37.4 | 0.3 | 327.4 | 12.2 | 47.4 | 1.6 | 7.351 | 0.014 | 115.5 | 8.5d | |

| Ketoprofen | 37.7 | 0.1 | 328.4 | 11.4 | 44.0 | 1.1 | 7.365 | 0.015 | 130.6 | 4.0 | |

| 24 h LPS | 37.6 | 0.2 | 325 | 11.3 | 45.9 | 0.4 | 7.334 | 0.007 | 149.8 | 9.8 | |

| 24 h LPS + ketoprofen | 37.4 | 0.2 | 326 | 8.5 | 46.4 | 1.3 | 7.3165 | 0.012 | 143.4 | 8.9 | |

| 24 h LPS + ketoprofen vehicle | 37.6 | 0.2 | 342.5 | 7.6 | 46.3 | 2.0 | 7.324 | 0.022 | 140.9 | 10.9 | |

| Hx | 24 h Time control | 37.5 | 0.2 | 336.7 | 6.8a | 45.7 | 1.0 | 7.334 | 0.012 | 129.6 | 6.2a |

| 24 h Vehicle | 37.4 | 0.3 | 37.9 | 2.9b | 47.8 | 1.3 | 7.351 | 0.014 | 75.3 | 20.6c,d | |

| Ketoprofen | 37.6 | 0.1 | 39.6 | 1.7b | 45.8 | 2.0 | 7.365 | 0.015 | 57.7 | 8.2b,d | |

| 24 h LPS | 37.6 | 0.2 | 39.7 | 2.1b | 47.8 | 0.3 | 7.334 | 0.008 | 111.0 | 18.0b | |

| 24 h LPS + ketoprofen | 37.4 | 0.2 | 39.3 | 1.7b | 47.9 | 1.6 | 7.317 | 0.012 | 88.1 | 10.6b | |

| 24 h LPS + ketoprofen vehicle | 37.4 | 0.1 | 42.8 | 0.7b | 44.8 | 2.0 | 7.324 | 0.022 | 82.8 | 21.7b | |

| 60 min | 24 h Time control | 37.4 | 0.2 | 334.3 | 6.3 | 45.8 | 0.8 | 7.372 | 0.011 | 126.5 | 6.2 |

| 24 h Vehicle | 37.2 | 0.3 | 326.0 | 9.0 | 48.8 | 1.0 | 7.351 | 0.017 | 105.6 | 7.7d | |

| Ketoprofen | 37.7 | 0.1 | 322.2 | 6.1 | 44.3 | 1.4 | 7.380 | 0.022 | 112.9 | 8.3d | |

| 24 h LPS | 37.6 | 0.2 | 319.6 | 8.0 | 45.8 | 0.6 | 7.361 | 0.012 | 145.2 | 9.7 | |

| 24 h LPS + ketoprofen | 37.4 | 0.1 | 319.2 | 11.1 | 46.5 | 1.4 | 7.360 | 0.011 | 134.2 | 10.2 | |

| 24 h LPS + ketoprofen vehicle | 37.6 | 0.1 | 310.5 | 8.9 | 46.1 | 1.8 | 7.375 | 0.017 | 133.8 | 10.1 | |

Temperatures are in °C; PaO2, PaCO2, and MAP are in mmHg. There were no significant differences in temperature, PaCO2, or pH.

P < 0.001, significant difference from all other Hx groups.

P < 0.001, significant difference from other time points within group.

P < 0.05, significant difference from baseline within group.

P < 0.05, significant difference from 24 h LPS.

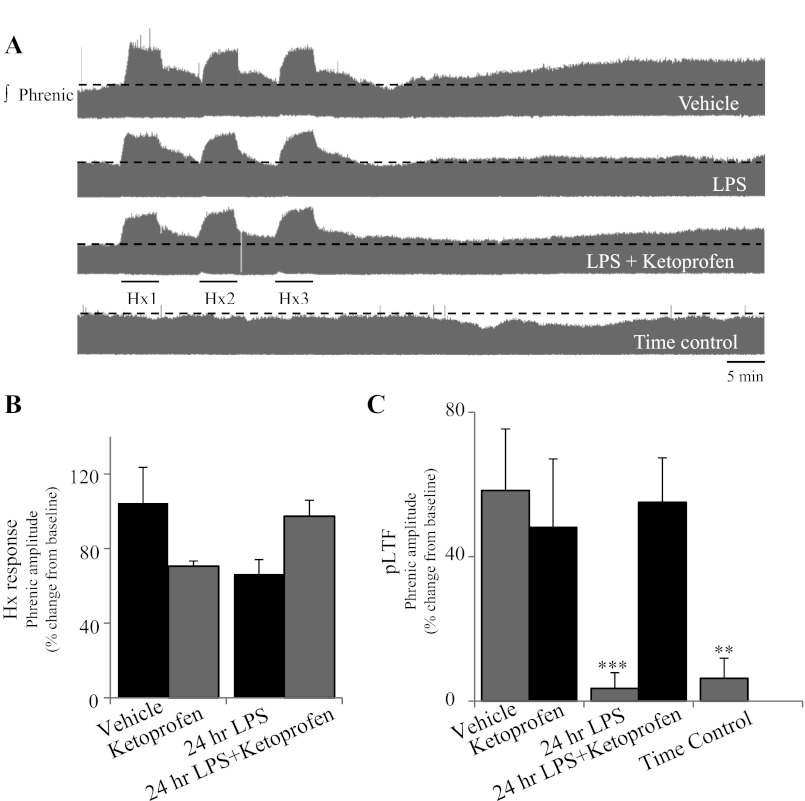

The short-term hypoxic phrenic response was not significantly altered 24 h post-LPS (Fig. 2, A and B). There were no significant differences in phrenic nerve burst amplitude during hypoxia in the vehicle group (104 ± 19%;), ketoprofen (71 ± 3%), 24 h LPS (66 ± 8%), or 24 h LPS + ketoprofen (97 ± 9%) (P > 0.05, one-way ANOVA on ranks). Baseline phrenic burst frequency was 44 ± 2 bursts/min for time controls, 42 ± 1 bursts/min for 24 h vehicle, 43 ± 2 bursts/min for ketoprofen, 47 ± 2 bursts/min for 24 h LPS, 46 ± 2 bursts/min for 24 h LPS + ketoprofen, and 46 ± 1 bursts/min for 24 h LPS + ketoprofen vehicle. There was a modest effect on phrenic burst frequency at 60 min post-AIH 24 h post-LPS (data not shown). The change in phrenic burst frequency post-AIH in vehicle-treated rats was 5.9 ± 2.3 bursts/min (n = 5), whereas the 24 h LPS group was −1.8 ± 1.6 bursts/min (n = 9) and time controls were −0.9 ± 1.2 bursts/min (n = 15). The change in the vehicle group was significantly different vs. LPS (P = 0.005) and time control (P = 0.010) groups but not vs. ketoprofen (2.6 ± 2.1 bursts/min, n = 5, P = 0.687) or 24 h LPS + ketoprofen (0.4 ± 1.4 bursts/min, n = 6, P = 0.149) groups (repeated-measures two-way ANOVA, Tukey post hoc test).

Fig. 2.

Systemic inflammation (24 h) induced by LPS (100 μg/kg ip) did not alter the short-term hypoxia response, significantly reduced AIH-induced pLTF, but pLTF was restored with the anti-inflammatory drug ketoprofen (12.5 mg/kg ip, 3 h). A: representative integrated phrenic neurograms from anesthetized rats during the AIH (3 × 5 min hypoxia) protocol for vehicle-injected (saline, top trace), LPS-injected (second trace), LPS + ketoprofen-injected (third trace), and time control (no AIH, bottom trace) rats. Black dashed line indicates baseline phrenic amplitude in each trace. Development of pLTF was evident as a progressive increase in phrenic nerve amplitude over 60 min. B: no change in the short-term hypoxia response was evident. C: group data showing pLTF for vehicle-injected (n = 5) and ketoprofen-injected (n = 6) rats with AIH, and a reduction in pLTF in rats injected with LPS (n = 9). The appearance of pLTF was restored in rats injected with LPS and after treatment with ketoprofen (n = 6). There was no increase in phrenic nerve amplitude in time control rats (n = 15). (***P < 0.001, **P < 0.01 indicates significant difference from vehicle, ketoprofen, and 24 h LPS + ketoprofen).

Impaired pLTF persisted 24 h post-LPS, and this effect was reversed by pretreatment with ketoprofen (Fig. 2C). In vehicle-injected rats (58.3 ± 17.1%; n = 5) and in rats treated with ketoprofen (48.1 ± 19.0%, n = 5), AIH elicited similar pLTF (P = 0.948, repeated-measures two-way ANOVA, Tukey post hoc test). pLTF was significantly reduced 24 h post-LPS (3.5 ± 4.3%, n = 9, P < 0.001 vs. vehicle, P = 0.004 vs. ketoprofen) and this effect was reversed by ketoprofen (55.1 ± 12.3%, n = 6; P = 0.999 vs. vehicle; P = 0.985 vs. ketoprofen; P < 0.001 vs. LPS) (repeated-measures two-way ANOVA, Tukey post hoc test).

Peripheral inflammatory gene expression.

Since LPS does not cross the blood-brain barrier, peripheral LPS-induced inflammation indirectly triggers CNS inflammatory responses (9, 23, 36, 39, 53, 55). Thus we assessed splenic inflammatory gene expression as a marker for systemic inflammation; the same genes were assessed in the cervical spinal cord 3 and 24 h post-LPS. Ketoprofen effects on LPS-induced changes were evaluated only at 24 h post-LPS.

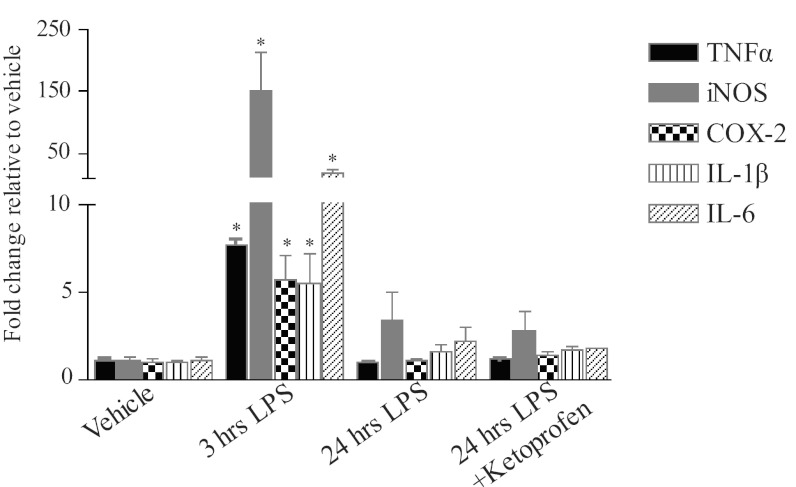

A transient increase in all inflammatory genes examined was evident in the spleen (Fig. 3). Three hours post-LPS (n = 3), TNFα (7.5 ± 0.2 fold, P < 0.001), iNOS (72.6 ± 12.3 fold, P < 0.001), COX-2 (4.4 ± 0.2 fold, P = 0.013), IL-1β (4.6 ± 0.1 fold, P < 0.001), and IL-6 (19.2 ± 3.5 fold, P < 0.001) expressions all significantly increased vs. respective vehicle controls. However, by 24 h post-LPS, mRNA levels for all splenic genes had returned toward baseline values (TNFα: 1.0 ± 0.1 fold, P = 0.995; iNOS: 3.4 ± 1.6 fold, P = 0.083; COX-2: 1.1 ± 0.1 fold, P = 0.844; IL-1β: 1.6 ± 0.4 fold, P = 0.943; IL-6: 2.2 ± 0.8 fold, P = 0.640). Gene expression 24 h post-LPS was not significantly altered by ketoprofen (TNFα 1.2 ± 0.01 fold, P = 0.829; iNOS 1.8 ± 0.6 fold, P = 0.233; COX-2 0.8 ± 0.1 fold, P = 0.981; IL-1β 1.1 ± 0.1 fold, P = 0.939; IL-6 1.1 ± 0.02 fold, P = 0.956), despite the ability of ketoprofen to restore pLTF.

Fig. 3.

Systemic inflammation induced by LPS (100 μg/kg ip) caused a transient increase in inflammatory gene expression in the spleen. LPS (3 h) caused a significant increase in all inflammatory genes (n = 3) examined compared with the respective vehicle control (n = 4) but returned to baseline levels by 24 h (n = 3) and was not altered with ketoprofen (n = 2) (*P ≤ 0.001 different from all other treatment groups).

Cervical spinal gene expression (3 h).

Inflammatory genes were examined in cervical spinal microglia and homogenates post-LPS (Fig. 4). Only two inflammatory genes exhibited significant increases within microglia or homogenates after LPS: iNOS (microglia 16.7 ± 4.4, P < 0.001, n = 8; homogenate 8.9 ± 1.9, P < 0.001, n = 8) and COX-2 (microglia 2.8 ± 0.6, P = 0.019, n = 7; homogenate 5.1 ± 1.2, P < 0.001, n = 8) vs. vehicle controls (iNOS: microglia n = 15, homogenate n = 14; COX-2: microglia n = 15, homogenate n = 15). There were no significant differences in gene expression between sample type (microglia vs. homogenate) for iNOS or COX-2 (iNOS P = 0.172, COX-2 P = 0.087). There were no differences in either sample type vs. vehicle controls after LPS (n = 14) for IL-1β (microglia 0.7 ± 0.1 fold, P = 0.562, n = 8; homogenate 0.8 ± 0.3 fold, P = 0.884, n = 7) or TNFα (microglia 0.9 ± 0.2, P > 0.05, n = 7; homogenates 1.7 ± 0.3, P > 0.05, n = 7).

Cervical spinal gene expression (24 h).

LPS (24 h) had no significant effects on iNOS (microglia: 2.4 ± 0.8 P = 0.368, n = 7; homogenates 1.5 ± 0.3 P = 0.557, n = 6), COX-2 (microglia: 1.0 ± 0.3, P = 0.978, n = 7; homogenates: 2.1 ± 0.8, P = 0.473, n = 6), IL-1β (microglia: 0.6 ± 0.2, P = 0.464, n = 7; homogenates: 0.5 ± 0.2, P = 0.390, n = 5), or TNFα (microglia: 1.6 ± 0.4, P > 0.05, n = 7; homogenates 1.7 ± 0.5, P > 0.05, n = 6) in either sample type vs. vehicle controls (Fig. 4). However, mRNA for iNOS (microglia P < 0.001, homogenates P < 0.001; Fig. 4A) and COX-2 (microglia P = 0.024, homogenates P = 0.013; Fig. 4B) was significantly reduced vs. 3 h LPS within each sample type, suggesting that inflammatory gene expression was returning to baseline values.

Ketoprofen did not significantly alter gene expression in 24 h post-LPS rats (P > 0.05) in either sample type for any gene examined (Fig. 4). Nor did ketoprofen alter gene expression vs. vehicle controls for iNOS (microglia: 2.1 ± 0.6, P = 0.257, n = 8; homogenates: 0.8 ± 0.1, P = 0.964, n = 7), COX-2 (microglia: 0.9 ± 0.1, P = 0.892, n = 8; homogenates: 2.2 ± 0.5, P = 0.066, n = 7), IL-1β (microglia: 0.5 ± 0.1, P = 0.302, n = 8; homogenates: 0.4 ± 0.1, P = 0.172, n = 5), or TNFα (microglia: 1.9 ± 0.8, P > 0.05, n = 8; homogenates: 2.2 ± 1.1, P > 0.05, n = 7).

Ketoprofen pretreatment did, however, highlight differences between sample types (microglia vs. homogenate) (Fig. 4). Microglia had greater iNOS gene expression vs. homogenates (P = 0.037), whereas microglia had less COX-2 mRNA vs. homogenates (P = 0.011). Thus microglia may not be the sole contributors to inflammatory molecules in some conditions.

DISCUSSION

Here, we demonstrate that systemic administration of a low dose of LPS impairs AIH-induced pLTF as early as 3 h post LPS injection, an effect that lasts for at least 24 h. However, pLTF impairment is accompanied by only transient (3 h) increases in inflammatory gene expression in the cervical spinal cord. Despite a lack of detectable inflammatory gene expression 24 h post-LPS, systemic administration of the nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug ketoprofen (at 21 h) reverses pLTF impairment. We do not yet know the basis for persistent impairment of pLTF without increases in measured inflammatory molecules. Several possibilities are discussed below.

LPS as a model of inflammation.

At low doses, LPS activates TLR4/2 receptors, triggering levels of inflammation frequently experienced by humans (62). Since many clinical disorders are associated with low-grade systemic inflammation, low LPS doses may better represent low-grade infections or inflammation and their impact on respiratory plasticity.

In the literature, LPS has been used at a variety of dosages and time points to stimulate systemic inflammation. LPS doses vary from nanograms to milligrams per kilogram (26, 28). LPS effects include behaviors indicative of illness (10, 14, 22), microglial activation, impaired memory, and motor function (32, 57, 61, 64, 66), and changes in neurotrophic factor expression (55). The concentration used here is in the low range reported for rats (16) and elicits reliable systemic and CNS inflammation in mice (62, 72). Higher LPS doses (500 μg/kg or more) typically cause severe systemic inflammation, septic shock, and fever (34, 59, 71), none of which were observed in this study.

Although LPS is often administered systemically to induce CNS inflammation, it does not cross the blood-brain barrier (49, 58). CNS inflammation arises from indirect effects, such as circulating or vascular endothelial cytokines (or other inflammatory molecules) that do cross the blood-brain barrier (49, 58) or neural transmission to the CNS via the vagus nerves (8, 21, 54, 69). Potential molecules crossing the blood-brain barrier to trigger CNS inflammatory activities include the cytokines we assessed in the spleen (e.g., IL-1β and TNF-α) or prostaglandins produced by perivascular macrophages and/or endothelial cells that line the blood-brain barrier (9, 23, 36, 39, 53, 55). However, the precise mechanism(s) of CNS inflammation following LPS injection was not a focus of this study.

We confirmed both systemic and CNS inflammation by examining mRNA levels of selected proinflammatory molecules (iNOS, COX-2, TNFα, and IL-1β). In general, mRNA changes were similar in the spleen and cervical spinal cord. Spleen inflammatory gene expression was greatest 3 h post-LPS (up to 150-fold increase) but had largely returned to baseline expression levels by 24 h post-LPS. We assessed CNS inflammation in cervical spinal segments associated with the phrenic motor nucleus, since cellular mechanisms of pLTF are localized in this region (3, 5, 27, 38). Cervical spinal inflammation was evident in both isolated microglia and homogenates.

Although microglia comprise only a small component of the CNS by volume, they are the predominant immune cells in the CNS (25). To assess microglial LPS responses in the cervical spinal cord, we compared mRNA in spinal homogenates and isolated microglia. Overall, similar trends to the spleen were observed, where iNOS and COX-2 mRNA increased 3- to 15-fold in microglia and homogenates 3 h post-LPS. Although mRNA levels returned nearly to baseline by 24 h post-LPS, we do not have information concerning protein levels for any of the molecules assessed. Collectively, our data suggest that microglia are major contributors to overall changes in inflammatory gene expression in the cervical spinal cord after LPS; however, we cannot rule out important contributions from other cells types, such as astrocytes or neurons.

The time course for increased inflammatory gene expression was shorter than pLTF impairment. Potential explanations include long-lasting changes in the expression of unmeasured molecules that undermine pLTF. Candidate molecules include unmeasured cytokines, interleukins, interferons, chemokines, or other enzymes that initiate distinct signaling cascades. Another possibility is that protein levels of a key molecule outlast mRNA changes (e.g., iNOS or COX-2). A third possibility is that small, persistent elevations in measured molecules were critical in the mechanism undermining pLTF, although not statistically detectable. For example, a critical molecule may need to change very little to undermine pLTF or, more likely, multiple small but undetectable increases (1–2 fold) may act in a cumulative manner, activating a common downstream target molecule that more directly impairs pLTF. All of these possibilities are consistent with ketoprofen restoration of pLTF.

Unlike our previous study using a high LPS dose (67), we observed no change in short-term hypoxic ventilatory response after the low LPS dose used here (either 3 or 24 h post-LPS). Since the magnitude of pLTF correlates with the magnitude of the hypoxic phrenic response in rats (4, 20), there was some concern that the depressed hypoxic phrenic response indirectly impaired pLTF in Vinit et al. (67). Since the hypoxic phrenic response was not affected here, yet pLTF was nevertheless abolished, potential indirect effects are ruled out. Collectively, the data presented here are consistent with the conclusion that a low-grade systemic inflammation suppresses pLTF in rats.

Ketoprofen is a general anti-inflammatory drug used here to confirm that LPS undermines pLTF by inducing inflammation. S-enantiomers of ketoprofen inhibit COX-1 and COX-2 at low doses and NFκB at higher doses (13, 73). Ketoprofen inhibits both cyclooxygenase and lipoxygenase pathways for arachidonic acid metabolism, thereby inhibiting synthesis of prostaglandins and leukotrienes (11). Ketoprofen has been given at doses ranging from 100 μg/kg to 50 mg/kg via multiple routes of administration (11, 12, 44, 47). The ketoprofen dose used here was moderately high, making it unclear if its effects were on COX-2 or NFκB. Ketoprofen did not reduce expression of any inflammatory molecules examined; however, we cannot rule out effects of ketoprofen on proteins or other inflammatory molecules not examined. Regardless, our results suggest that a long-lasting, ketoprofen-sensitive molecule significantly impacts AIH-induced pLTF.

The rapid effects of ketoprofen (3 h) in restoring pLTF may implicate COX-2 and prostaglandin synthesis in the impairment of pLTF. These rapid effects are more easily explained by inhibition of COX-2 enzymatic activity (vs. inhibition of NF-κB regulated gene expression). Other studies demonstrate that CNS effects of low-grade systemic inflammation can be dependent on prostaglandins and COX activity (62). Additional studies are necessary to test this idea.

In conclusion, we are only beginning to understand the profound impact of inflammation on respiratory plasticity. The present study highlights the impact of even low-grade systemic inflammation on an important model of respiratory plasticity, AIH-induced pLTF. Further, we provide evidence that microglia, and perhaps other CNS cells, may generate the (as yet unknown) inflammatory molecules that undermine pLTF.

GRANTS

This study was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants HL-80209, HL-69064, HL-111598, T32-HL-007654 (S. M. Smith), and NS-049033 (J. J. Watters), and the Craig H. Neilsen foundation (S. Vinit).

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the author(s).

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Author contributions: A.G.H., S.M.S., J.J.W., and G.S.M. conception and design of research; A.G.H., S.M.S., and S.V. performed experiments; A.G.H., S.M.S., and S.V. analyzed data; A.G.H., S.M.S., J.J.W., and G.S.M. interpreted results of experiments; A.G.H. and S.M.S. prepared figures; A.G.H. drafted manuscript; A.G.H., S.M.S., S.V., J.J.W., and G.S.M. edited and revised manuscript; A.G.H., S.M.S., J.J.W., and G.S.M. approved final version of manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1. Amor S, Puentes F, Baker D, van der Valk P. Inflammation in neurodegenerative diseases. Immunology 129: 154–169, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Bach KB, Mitchell GS. Hypoxia-induced long-term facilitation of respiratory activity is serotonin dependent. Respir Physiol 104: 251–260, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Baker-Herman TL, Fuller DD, Bavis RW, Zabka AG, Golder FJ, Doperalski NJ, Johnson RA, Watters JJ, Mitchell GS. BDNF is necessary and sufficient for spinal respiratory plasticity following intermittent hypoxia. Nat Neurosci 7: 48–55, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Baker-Herman TL, Mitchell GS. Determinants of frequency long-term facilitation following acute intermittent hypoxia in vagotomized rats. Respir Physiol Neurobiol 162: 8–17, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Baker-Herman TL, Mitchell GS. Phrenic long-term facilitation requires spinal serotonin receptor activation and protein synthesis. J Neurosci 22: 6239–6246, 2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Balan KV, Kc P, Hoxha Z, Mayer CA, Wilson CG, Martin RJ. Vagal afferents modulate cytokine-mediated respiratory control at the neonatal medulla oblongata. Respir Physiol Neurobiol 178: 458–464, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Bhattacharjee R, Kim J, Kheirandish-Gozal L, Gozal D. Obesity and obstructive sleep apnea syndrome in children: A tale of inflammatory cascades. Pediatr Pulmonol 46: 313–323, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Blatteis CM. The onset of fever: new insights into its mechanism. Prog Brain Res 162: 3–14, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Blatteis CM, Li S. Pyrogenic signaling via vagal afferents: what stimulates their receptors? Auton Neurosci 85: 66–71, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Broad A, Jones DE, Kirby JA. Toll-like receptor (TLR) response tolerance: a key physiological “damage limitation” effect and an important potential opportunity for therapy. Curr Med Chem 13: 2487–2502, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Buritova J, Honore P, Besson JM. Ketoprofen produces profound inhibition of spinal c-Fos protein expression resulting from an inflammatory stimulus but not from noxious heat. Pain 67: 379–389, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Cabre F, Fernandez MF, Calvo L, Ferrer X, Garcia ML, Mauleon D. Analgesic, antiinflammatory, and antipyretic effects of S(+)-ketoprofen in vivo. J Clin Pharmacol 38: 3S–10S, 1998 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Cashman JN. The mechanisms of action of NSAIDs in analgesia. Drugs 5: 13–23, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Conrad A, Bull DF, King MG, Husband AJ. The effects of lipopolysaccharide (LPS) on the fever response in rats at different ambient temperatures. Physiol Behav 62: 1197–1201, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Crain JM, Nikodemova M, Watters JJ. Expression of P2 nucleotide receptors varies with age and sex in murine brain microglia. J Neuroinflammation 6: 24, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Cunningham C, Campion S, Lunnon K, Murray CL, Woods JF, Deacon RM, Rawlins JN, Perry VH. Systemic inflammation induces acute behavioral and cognitive changes and accelerates neurodegenerative disease. Biol Psychiatry 65: 304–312, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Deakin AM, Payne AN, Whittle BJ, Moncada S. The modulation of IL-6 and TNF-alpha release by nitric oxide following stimulation of J774 cells with LPS and IFN-gamma. Cytokine 7: 408–416, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Di Filippo M, Sarchielli P, Picconi B, Calabresi P. Neuroinflammation and synaptic plasticity: theoretical basis for a novel, immune-centred, therapeutic approach to neurological disorders. Trends Pharmacol Sci 29: 402–412, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Feldman JL, Mitchell GS, Nattie EE. Breathing: rhythmicity, plasticity, chemosensitivity. Annu Rev Neurosci 26: 239–266, 2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Fuller DD, Bach KB, Baker TL, Kinkead R, Mitchell GS. Long term facilitation of phrenic motor output. Respir Physiol 121: 135–146, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Ge X, Yang Z, Duan L, Rao Z. Evidence for involvement of the neural pathway containing the peripheral vagus nerve, medullary visceral zone and central amygdaloid nucleus in neuroimmunomodulation. Brain Res 914: 149–158, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Godbout JP, Berg BM, Kelley KW, Johnson RW. alpha-Tocopherol reduces lipopolysaccharide-induced peroxide radical formation and interleukin-6 secretion in primary murine microglia and in brain. J Neuroimmunol 149: 101–109, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Goehler LE, Gaykema RPA, Nguyen KT, Lee JE, Tilders FJH, Maier SF, Watkins LR. Interleukin-1beta in immune cells of the abdominal vagus nerve: a link between the immune and nervous systems? J Neurosci 19: 2799–2806, 1999 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Gozal D. Sleep, sleep disorders and inflammation in children. Sleep Med 1: S12–S16, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Graeber MB. Changing face of microglia. Science 330: 783–788, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Hashimoto M, Nitta A, Fukumitsu H, Nomoto H, Shen L, Furukawa S. Inflammation-induced GDNF improves locomotor function after spinal cord injury. Neuroreport 16: 99–102, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Hoffman MS, Nichols NL, Macfarlane PM, Mitchell GS. Phrenic long-term facilitation after acute intermittent hypoxia requires spinal ERK activation but not TrkB synthesis. J Appl Physiol 113: 1184–1193, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Holden JM, Meyers-Manor JE, Overmier JB, Gahtan E, Sweeney W, Miller H. Lipopolysaccharide-induced immune activation impairs attention but has little effect on short-term working memory. Behav Brain Res 194: 138–145, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Huxtable AG, Vinit S, Windelborn JA, Crader SM, Guenther CH, Watters JJ, Mitchell GS. Systemic inflammation impairs respiratory chemoreflexes and plasticity. Respir Physiol Neurobiol 178: 482–489, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Kaminska B, Gozdz A, Zawadzka M, Ellert-Miklaszewska A, Lipko M. MAPK signal transduction underlying brain inflammation and gliosis as therapeutic target. Anat Rec (Hoboken) 292: 1902–1913, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Kaufmann WE, Andreasson KI, Isakson PC, Worley PF. Cyclooxygenases and the central nervous system. Prostaglandins 54: 601–624, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Kelly A, Laroche S, Davis S. Activation of mitogen-activated protein kinase/extracellular signal-regulated kinase in hippocampal circuitry is required for consolidation and reconsolidation of recognition memory. J Neurosci 23: 5354–5360, 2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Kimoff RJ, Hamid Q, Divangahi M, Hussain S, Bao W, Naor N, Payne RJ, Ariyarajah A, Mulrain K, Petrof BJ. Increased upper airway cytokines and oxidative stress in severe obstructive sleep apnoea. Eur Respir J 38: 89–97,2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Kozak W, Soszynski D, Rudolph K, Conn CA, Kluger MJ. Dietary n-3 fatty acids differentially affect sickness behavior in mice during local and systemic inflammation. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 272: R1298–R1307, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Kreutzberg GW. Microglia: a sensor for pathological events in the CNS. Trends Neurosci 19: 312–318, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Laflamme N, Lacroix S, Rivest S. An essential role of interleukin-1beta in mediating NF-kappa B activity and COX-2 transcription in cells of the blood-brain barrier in response to a systemic and localized inflammation but not during endotoxemia. J Neurosci 19: 10923–10930, 1999 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Leon CG, Tory R, Jia J, Sivak O, Wasan KM. Discovery and development of toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4) antagonists: a new paradigm for treating sepsis and other diseases. Pharm Res 25: 1751–1761, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. MacFarlane PM, Mitchell GS. Episodic spinal serotonin receptor activation elicits long-lasting phrenic motor facilitation by an NADPH oxidase-dependent mechanism. J Physiol 587: 5469–5481, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Maier SF, Goehler LE, Fleshner M, Watkins LR. The role of the vagus nerve in cytokine-to-brain communication. Ann NY Acad Sci 840: 289–300, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. McColl BW, Allan SM, Rothwell NJ. Systemic infection, inflammation and acute ischemic stroke. Neuroscience 158: 1049–1061, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Mitchell GS, Johnson SM. Neuroplasticity in respiratory motor control. J Appl Physiol 94: 358–374, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Nam NH. Naturally occurring NF-kappaB inhibitors. Mini Rev Med Chem 6: 945–951, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Nikodemova M, Watters JJ. Efficient isolation of live microglia with preserved phenotypes from adult mouse brain. J Neuroinflammation 9: 147, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Ossipov MH, Jerussi TP, Ren K, Sun H, Porreca F. Differential effects of spinal (R)-ketoprofen and (S)-ketoprofen against signs of neuropathic pain and tonic nociception: evidence for a novel mechanism of action of (R)-ketoprofen against tactile allodynia. Pain 87: 193–199, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Parrillo JE, Parker MM, Natanson C, Suffredini AF, Danner RL, Cunnion RE, Ognibene FP. Septic shock in humans: Advances in the understanding of pathogenesis, cardiovascular dysfunction, and therapy. Ann Intern Med 113: 227–242, 1990 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Perry VH. Contribution of systemic inflammation to chronic neurodegeneration. Acta Neuropathol (Berl) 120: 277–286, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Pinardi G, Sierralta F, Miranda HF. Atropine reverses the antinociception of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs in the tail-flick test of mice. Pharmacol Biochem Behav 74: 603–608, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Poltorak A, He X, Smirnova I, Liu MY, Huffel CV, Du X, Birdwell D, Alejos E, Silva M, Galanos C, Freudenberg M, Ricciardi-Castagnoli P, Layton B, Beutler B. Defective LPS signaling in C3H/HeJ and C57BL/10ScCr mice: Mutations in Tlr4 gene. Science 282: 2085–2088, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Qin L, Wu X, Block ML, Liu Y, Breese GR, Hong JS, Knapp DJ, Crews FT. Systemic LPS causes chronic neuroinflammation and progressive neurodegeneration. Glia 55: 453–462, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Renz H, Gong JH, Schmidt A, Nain M, Gemsa D. Release of tumor necrosis factor-alpha from macrophages: Enhancement and suppression are dose-dependently regulated by prostaglandin E2 and cyclic nucleotides. J Immunol 141: 2388–2393, 1988 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Ricciardolo FL, Sterk PJ, Gaston B, Folkerts G. Nitric oxide in health and disease of the respiratory system. Physiol Rev 84: 731–765, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Rivest S. How circulating cytokines trigger the neural circuits that control the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis. Psychoneuroendocrinology 26: 761–788, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Rivest S. Regulation of innate immune responses in the brain. Nat Rev Immunol 9: 429–439, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Roth J, De Souza GE. Fever induction pathways: evidence from responses to systemic or local cytokine formation. Braz J Med Biol Res 34: 301–314, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Schnydrig S, Korner L, Landweer S, Ernst B, Walker G, Otten U, Kunz D. Peripheral lipopolysaccharide administration transiently affects expression of brain-derived neurotrophic factor, corticotropin and proopiomelanocortin in mouse brain. Neurosci Lett 429: 69–73, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Sedgwick JD, Schwender S, Imrich H, Dorries R, Butcher GW, ter Meulen V. Isolation and direct characterization of resident microglial cells from the normal and inflamed central nervous system. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 88: 7438–7442, 1991 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Shaw KN, Commins S, O'Mara SM. Lipopolysaccharide causes deficits in spatial learning in the watermaze but not in BDNF expression in the rat dentate gyrus. Behav Brain Res 124: 47–54, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Singh AK, Jiang Y. How does peripheral lipopolysaccharide induce gene expression in the brain of rats? Toxicology 201: 197–207, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Sparkman NL, Buchanan JB, Heyen JR, Chen J, Beverly JL, Johnson RW. Interleukin-6 facilitates lipopolysaccharide-induced disruption in working memory and expression of other proinflammatory cytokines in hippocampal neuronal cell layers. J Neurosci 26: 10709–10716, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Stockley RA. Progression of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: impact of inflammation, comorbidities and therapeutic intervention. Curr Med Res Opin 25: 1235–1245, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Swiergiel AH, Dunn AJ. Effects of interleukin-1beta and lipopolysaccharide on behavior of mice in the elevated plus-maze and open field tests. Pharmacol Biochem Behav 86: 651–659, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Teeling JL, Felton LM, Deacon RM, Cunningham C, Rawlins JN, Perry VH. Sub-pyrogenic systemic inflammation impacts on brain and behavior, independent of cytokines. Brain Behav Immun 21: 836–850, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Teeling JL, Perry VH. Systemic infection and inflammation in acute CNS injury and chronic neurodegeneration: underlying mechanisms. Neuroscience 158: 1062–1073, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Thomson LM, Sutherland RJ. Systemic administration of lipopolysaccharide and interleukin-1beta have different effects on memory consolidation. Brain Res Bull 67: 24–29, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Vane JR. Inhibition of prostaglandin synthesis as a mechanism of action for aspirin-like drugs. Nat New Biol 231: 232–235, 1971 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Vereker E, Campbell V, Roche E, McEntee E, Lynch MA. Lipopolysaccharide inhibits long term potentiation in the rat dentate gyrus by activating caspase-1. J Biol Chem 275: 26,252–26,258, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Vinit S, Windelborn JA, Mitchell GS. Lipopolysaccharide attenuates phrenic long-term facilitation following acute intermittent hypoxia. Respir Physiol Neurobiol 176: 130–135, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Walker JS. NSAID: an update on their analgesic effects. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol 22: 855–860, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Wieczorek M, Swiergiel AH, Pournajafi-Nazarloo H, Dunn AJ. Physiological and behavioral responses to interleukin-1beta and LPS in vagotomized mice. Physiol Behav 85: 500–511, 2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Wills-Karp M. Immunologic basis of antigen-induced airway hyperresponsiveness. Annu Rev Immunol 17: 255–281, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Wong ML, Bongiorno PB, Rettori V, McCann SM, Licinio J. Interleukin (IL) 1beta, IL-1 receptor antagonist, IL-10, and IL-13 gene expression in the central nervous system and anterior pituitary during systemic inflammation: pathophysiological implications. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 94: 227–232, 1997 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Yamawaki Y, Kimura H, Hosoi T, Ozawa K. MyD88 plays a key role in LPS-induced Stat3 activation in the hypothalamus. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 298: R403–R410, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Yin MJ, Yamamoto Y, Gaynor RB. The anti-inflammatory agents aspirin and salicylate inhibit the activity of I(kappa)B kinase-beta. Nature 396: 77–80, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]