SUMMARY

The Hippo pathway regulates growth through the transcriptional co-activator Yorkie, but how Yorkie promotes transcription remains poorly understood. We address this by characterizing Yorkie’s association with chromatin, and by identifying nuclear partners that effect transcriptional activation. Co-immunoprecipitation and mass spectrometry identify GAGA Factor (GAF), Brahma complex, and Mediator complex as Yorkie-associated nuclear protein complexes. All three are required for Yorkie’s transcriptional activation of downstream genes, and GAF and the Brahma complex subunit Moira interact directly with Yorkie. Genome-wide chromatin binding experiments identify thousands of Yorkie sites, most of which are associated with elevated transcription, based on genome-wide analysis of mRNA and histone H3K4Me3 modification. Chromatin binding also supports extensive functional overlap between Yorkie and GAF. Our studies suggest a widespread role for Yorkie as a regulator of transcription, and identify recruitment of the chromatin modifying GAF protein and BRM complex as a molecular mechanism for transcriptional activation by Yorkie.

INTRODUCTION

The Hippo pathway is essential for normal development, and dysregulated in many cancers, reflecting its important role in growth control (Zhao et al., 2011). Hippo signaling is regulated by diverse upstream inputs, which converge on the protein kinases Hippo and Warts (Wts). Downstream outputs of Hippo signaling in Drosophila are all mediated through the oncogenic transcriptional co-activator Yorkie (Yki), which is negatively regulated by Wts (Oh and Irvine, 2010). As a transcriptional co-activator, Yki does not bind DNA directly, but instead interacts with DNA-binding proteins, utilizing multiple DNA-binding partners (Oh and Irvine, 2010). Once recruited to DNA, Yki’s role is to elevate the transcription of target genes, but the mechanism(s) by which it does so is not understood.

Two key aspects of transcriptional activation in eukaryotes are modulation of chromatin structure and recruitment of the core transcriptional machinery. Chromatin modifiers include ATP-dependent chromatin remodeling complexes, such as NURF or SWI/SNF, and histone modifying enzymes, which modulate the properties of nucleosomes through post-translational modifications (Li et al., 2007). Recruitment of the core transcriptional machinery can involve direct interactions with core components, or interactions with components of a large complex called Mediator, which links transcriptional activators to core subunits of RNA polymerase (Malik and Roeder, 2010). Chromatin modification and recruitment of core transcriptional machinery are often thought of as distinct processes, but they can be mechanistically linked. One transcription factor associated with both processes is GAGA factor (GAF, encoded by the Trithorax-like locus, Trl). GAF has been reported to associate with components of the core transcriptional machinery (Chopra et al., 2008), but was also identified as a gene required for the normal expression of homeotic genes, and in this role it is thought to act by influencing chromatin structure (Farkas et al., 1994). Here, we identify a direct physical link between Yki and proteins involved in chromatin remodeling, providing new insights into how Yki activates transcription.

RESULTS

Widespread localization of Yki on chromatin

Although several genes directly regulated by Yki have been identified, the full constellation of Yki targets is unknown. We identified Yki target genes by chromatin immunoprecipitation, using anti-Yki antisera and DNA-sequencing (ChIP-seq). This identifies candidate direct targets of Yki, whereas most genes whose transcription is altered by changes in Yki activity might be indirectly affected. Yki-associated chromatin was isolated and analyzed both from 8–16 hour embryos, and third instar wing discs. This identified a large number of loci with significant Yki association: 6491 Yki-bound regions in wing disc chromatin, and 3749 in embryonic chromatin (corresponding to an estimated 3899 and 2416 genes, respectively, when peaks within 500 bp of the transcription start site or within the transcription unit are assigned to that gene). Gene ontology analysis suggests that these genes are linked to a broad range of functions (Supplementary Table S1).

Genome annotation revealed that Yki-bound regions are enriched near promoters as compared to intronic, exonic, and intergenic regions (Figs. 1A, S1A), consistent with Yki’s role as a transcriptional activator. Comparison of transcript levels identified a correlation between transcription and Yki binding, as genes with Yki binding sites were expressed on average at over ten-fold fold higher levels than genes without Yki binding sites in wing discs, and at roughly seven-fold higher levels in embryos (Figs. 1B, S1B). Genomic analysis also revealed a correlation between Yki-bound chromatin and peaks of H3K4me3 modification. Across the genome, the average H3K4me3 ChIP signal near promoters, which is associated with actively transcribed genes (Eissenberg and Shilatifard, 2010), was several fold higher for genes with Yki sites than for genes without Yki sites (Figs. 1B, S1B). These observations indicate that Yki binding to chromatin is correlated with increased transcription, and thus imply that Yki acts as a broad regulator of transcriptional activity at thousands of loci throughout the genome.

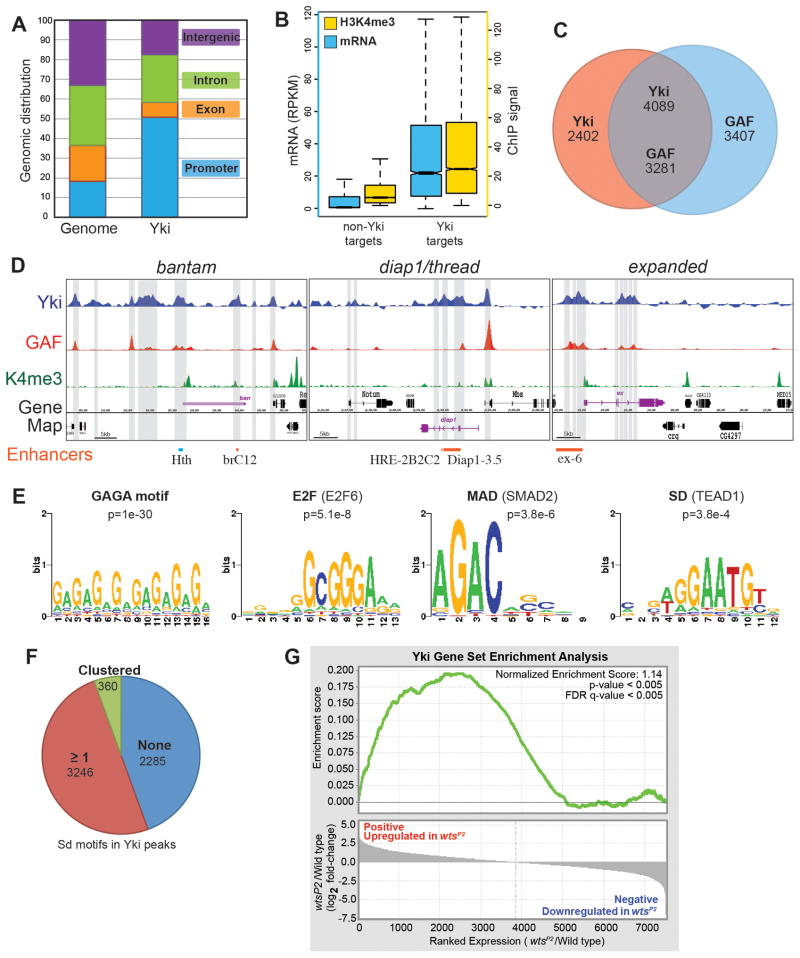

Fig. 1. Localization of Yki and GAF on chromosomes in wing discs.

A) Comparison of the percentage DNA near promoters (within 3 kb upstream of a transcription start site), intron, exon, and intergenic regions within the whole genome, and within the Yki-bound fraction. B) Comparison of the distribution of mRNA levels (blue) and proximal promoter (within 100 bp of transcription start) H3K4me3 modification (yellow) amongst between Yki target genes as and non-Yki targets. Units of expression for RNA-seq are Fragments per Kilobase of transcript per Million mapped reads (FPKM). H3K4me3 wing ChIP-seq data are from (Pérez-Lluch et al., 2011). C) Overlap between Yki and GAF binding sites, numbers indicate the numbers of peaks. Numbers in the overlap differ because one peak for one protein can overlap two peaks of the other. D) Plot of ChIP peaks at three loci regulated by Yki. Transcription units of targets are in purple, transcription units of neighboring genes are in black. Regions called as Yki peaks are identified by gray bars. Yki-responsive enhancers that have been identified at these loci (Oh and Irvine, 2011; Wu et al., 2008; Zhang et al., 2008) are indicated in orange at bottom, a previously identified Hth and Yki-binding region (Peng et al., 2009) is indicated in light blue. E) Motifs and significance scores for DNA-binding proteins at Yki-bound chromatin. De novo motif analysis identified variants on the GAF binding motif (GAGA) as the highest scoring. SMAD2 (Mad) and E2F binding motifs are enriched within all Yki binding regions, whereas TEAD1 (Sd) motifs are most enriched within Yki binding regions without a GAF binding site. F) Analysis of DNA within Yki-bound wing peaks using a degenerate Sd-binding motif consistent with the published literature (Halder and Carroll, 2001): [AT][AG][AG]AAT[GT][CT]. 2285 regions do not contain a Sd motif, and the remainder do. 360 regions contain clustered Sd motifs (2 motifs separated by 20 or fewer base pairs) and 3246 regions contain one or more isolated motifs. G) GSEA analysis of the correlation between relative expression changes and Yki binding. Genes are ordered according to their relative fold change between wild-type and wtsP2. Log2-transformed fold change values for expressed genes are plotted in the bottom graph (see Methods). The GSEA running enrichment score is represented in the top graph (green line). Genes that increase in wtsP2 are significantly enriched for Yki target genes (p <0.005; FDR q-value <0.005); genes that decrease in wtsP2 are not enriched for Yki targets. See also Fig. S1.

As a further test of this, we conducted expression analysis by RNA-seq on wing discs isolated from wild type and from wtsP2 mutant larvae (Justice et al., 1995). Comparison of the relative expression levels of genes associated with Yki peaks to those not associated with Yki peaks revealed that at the median expression level, they differed by over 30%. Amongst non-Yki-bound genes, the average expression was scored as having decreased, which we think reflects normalization to total genome-wide expression, which should be increased if most of the 3899 Yki-bound genes are affected by wtsP2. To provide a statistical test of the relation between Yki binding and transcriptional changes in wtsP2, we used Gene Set Enrichment Analysis (GSEA) (Subramanian et al., 2005). Indeed, genes with increased expression in wtsP2 were highly enriched for Yki target genes as determined by ChIP-seq (p<0.005) (Fig. 1G, Table S4).

We also examined Yki-binding at previously characterized targets of Yki. At three genes for which Yki-responsive enhancers have been characterized, ban (Oh and Irvine, 2011), Diap1 (Wu et al., 2008; Zhang et al., 2008), and ex (see below), Yki-binding peaks in wing discs overlap functionally defined Yki-response elements (Fig. 1D). These genes were all identified as Yki targets in imaginal discs, and Yki binding at these loci was more extensive in wing discs than in embryos (Figs. 1D, S1D).

Correlation between Yki and GAF binding

We used de novo motif discovery to find DNA sequence motifs that are enriched within Yki-bound chromatin. The most enriched motifs comprise GAGA-rich sequences (Figs. 1E, S1E, Table S2), which corresponds to the DNA recognition motif of GAF, which plays crucial roles at multiple steps of transcription (Adkins et al., 2006). Earlier studies have implicated Sd, Hth, and Mad in the recruitment of Yki to DNA (Oh and Irvine, 2010), and another DNA-binding transcription factor, E2F1, synergizes with Yki to regulate cell cycle genes (Nicolay et al., 2011). Binding sites for these proteins did not emerge from de novo motif analysis, but scanning against a database of known DNA motifs identified SMAD2 (Mad homologue)-binding and TEAD1 (Sd homologue)-binding motifs, and multiple E2F motifs, as enriched near the centers of Yki binding regions (Figure 1E, Table S2). E2F-related motifs were also overrepresented near the centers of Yki embryo peaks (Fig. S1E, Table S2), and a subset of Yki embryo peaks were enriched for TALE (Hth) motifs (Fig. S1E, Table S2). Moreover, when we analyzed Yki-bound regions with a more degenerate Sd-binding motif, then 50–60 percent of Yki peaks contain one or more potential Sd-binding sites (Figs. 1F, S1F). These results support a model in which Yki is recruited to DNA by multiple factors.

To address the significance of GAGA-rich sequences, we used a GAF antisera to perform ChIP-seq experiments, and identified GAF-bound chromatin in both 8–16 hr embryos and wing discs. A highly significant overlap between Yki and GAF sites was identified, as over 60% of Yki sites overlap GAF sites (Figs. 1C, S1C), including peaks at known target genes (Figs. 1D, S1D). This suggests that GAF is a frequent partner of Yki throughout the genome for transcriptional regulation of downstream genes.

Identification of GAF as a nuclear Yki-associated protein

To define mechanisms by which Yki activates transcription, we sought to identify nuclear Yki-associated proteins. Yki is normally predominantly cytoplasmic, reflecting endogenous Hippo pathway activity (Dong et al., 2007; Oh and Irvine, 2008). To avoid cytoplasmic Yki-associated proteins, we isolated nuclear extracts from Drosophila S2 cells, and then purified endogenous Yki complexes using anti-Yki serum or, as a control, pre-immune serum, attached to beads. Co-immunoprecipitated proteins, visualized by silver staining on SDS-PAGE gels, that were precipitated using anti-Yki and not pre-immune sera (Fig. 2A), were then identified by mass spectrometry. This identified several nuclear proteins with known roles in transcription, including GAF. Indeed, GAF was identified as the protein with the lowest log(e) score (an indication of high confidence in the assignment), and was identified from one of the most prominent bands in nuclear extracts (Fig. 2A, Table S3), implying that the correlation between Yki and GAF binding to chromatin reflects their physical association.

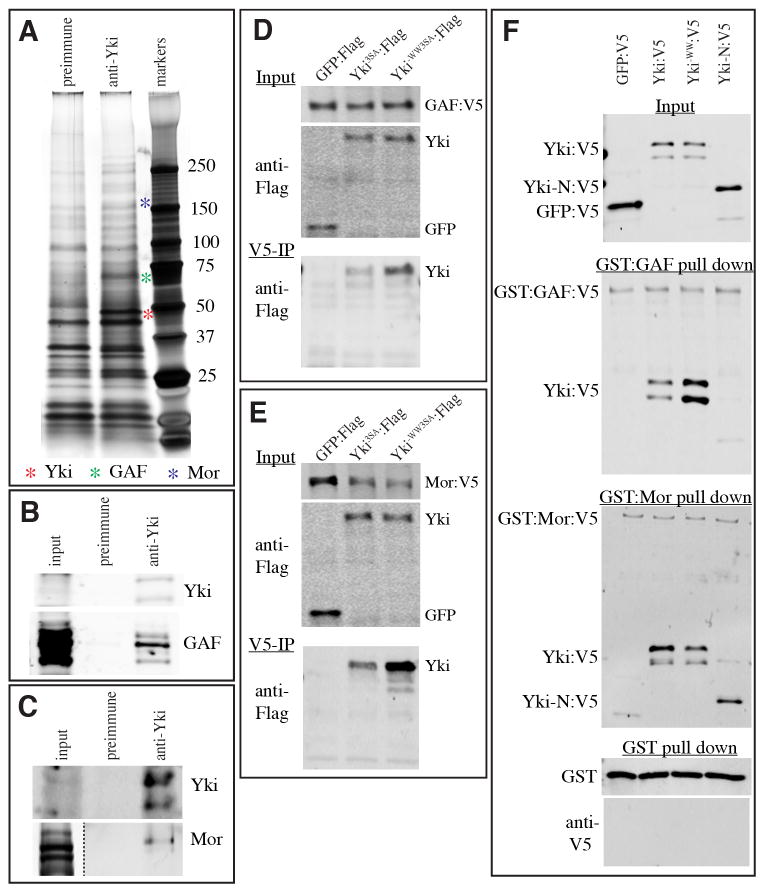

Fig. 2. Yki associates with GAF and Mor.

A) Silver-stained gel displaying proteins precipitated from S2 cell nuclear extracts by anti-Yki antibodies or preimmune-serum, as indicated. Red, green and blue asterisks indicate positions of Yki, GAF and Mor bands, as determined by immunoblotting or mass-spectrometry. B,C) Western blots on S2 cell nuclear extract (input), or proteins immunoprecipitated from S2 cell nuclear extract by anti-Yki antibodies or preimmune-serum, and detected by anti-Yki (top panels), anti-GAF (B, bottom panel), or anti-Mor (C, bottom panel). Nuclear Yki was barely detectible in the input lanes, but enriched by immunopurification, and is normally detected as a doublet. Three bands of GAF were detected by anti-GAF antibody. D,E) Western blots showing co-immunoprecipitation of Yki3SA:Flag or Yki-WW3SA:Flag with GAF:V5 (D) or Mor:V5 (E) from S2 cell nuclear extracts, GFP:Flag is a negative control. Upper panels (Input) show blots on nuclear lysates, lower panels (V5-IP) show blots (anti-Flag) on material precipitated by anti-V5 beads. F) Western blot showing results of GST pull-down assays. GST:GAF:V5, GST:Mor:V5, or GST were immobilized on glutathione-agarose beads and incubated with bacterially-expressed GFP:V5, Yki:V5, Yki-WW:V5, or Yki-N:V5. Protein complexes were washed, resolved by SDS-PAGE, and bound proteins - detected by anti-V5 or anti-GST antibodies, as indicated.

The identification of GAF as a Yki-interacting protein was confirmed by co-immunoprecipitation; western blotting revealed that GAF was specifically co-precipitated by anti-Yki, and not by pre-immune serum (Fig. 2B). To determine whether this interaction is direct, we performed co-precipitation assays on proteins expressed in bacteria. GAF was expressed as a GST fusion protein. Yki was pulled down by GST:GAF, but not by GST (Fig. 2F). Earlier studies identified an essential role for the WW domains of Yki in transcriptional activation (Oh and Irvine, 2010). An isoform of Yki in which all 3 Wts phosphorylation sites were mutated (Yki:V53SA), or an isoform that also contained inactivating mutations in the WW domains (Yki:V53SA-WW) (Oh and Irvine, 2009) were co-transfected in S2 cells with tagged GAF (GAF:FLAG). However, both Yki isoforms were co-immunoprecipitated with GAF (Fig. 2D), suggesting that the WW domains are not required for GAF binding. The WW domains were also not required for the interaction between GST-GAF and Yki in bacterial lysates (Fig. 2F).

Association of BRM and Mediator complexes with Yki

Two additional proteins, Moira (Mor), and Mediator complex subunit 23 (MED23), were also identified by low log(e) scores and represented by multiple peptides (Supplementary Table S3). Mor is a component of the Brahma (BRM) complex, the Drosophila cognate of the conserved SWI/SNF chromatin remodeling complex. Two additional components of the BRM complex, Brahma (Brm) and Dalao, were also identified as nuclear Yki-associated proteins by Mass spectrometry (Table S3). MED23 is a component of Mediator (reviewed in Malik and Roeder, 2010). Four additional Mediator subunits, MED15, MED31, MED19, and MED1, were also identified as nuclear Yki-associated proteins by mass spectrometry (Table S3). Previously characterized DNA-binding partners of Yki were either not identified (Hth, Mad), or identified but only with low log(e) scores (Sd, Table S3); their expression in S2 cells might be too low for robust identification by this approach.

We confirmed the identification of Mor as a Yki-associated protein through multiple approaches. Endogenous Mor was specifically co-immunoprecipitated from cultured Drosphila cells by anti-Yki antibodies (Fig. 2C), and V5-tagged Mor could precipitate FLAG-tagged Yki (Fig. 2E). Moreover, bacterially expressed Yki was specifically precipitated by GST:Mor (Fig. 2F). Thus, Yki and Mor can directly bind to each other, establishing a direct link from Yki to a chromatin remodeling complex. Both wild type Yki and Yki-WW also interacted with Mor (Fig. 2E,F), demonstrating that they bind to each other in a WW-domain independent manner. Although the C-terminal half of Yki (from aa 241) was not expressed well enough in bacteria to be assayed, the N-terminal half (Yki-N, up to aa 240) was expressed well. Yki-N did not interact well with GST-GAF, but did interact with GST:Mor, suggesting that Mor, but not GAF, interacts with the Yki N-terminus (Fig. 2F). Attempts to confirm a physical interaction between individual Mediator subunits and Yki were unsuccessful (not shown), but homologues of Yki (TAZ) and MED15 (ARC105) have been reported to co-associate within a complex in mammalian cells (Varelas et al., 2008).

GAF, BRM, and Mediator are required for Yki activity

A major biological function of Yki is promoting growth and inhibiting apoptosis. Mutation or downregulation of Trl, BRM components, or Mediator subunits can result in growth defects and reduced cell viability (Elfring et al., 1998; Farkas et al., 1994; Terriente-Félix et al., 2010) (Fig. S2). To determine whether this reflects roles in Yki-mediated transcription, three well-established in vivo targets of Yki: expanded (ex), thread, (th, commonly referred to as Diap1), and bantam (ban, a microRNA gene), were assayed in wing discs in which GAF, BRM subunits (Mor, Brm, or Dalao), or Mediator subunits (Kto, MED23 or MED15) were downregulated by RNAi. Expression of ex, monitored using an ex-lacZ reporter, could be reduced by knockdown of GAF (Fig. 3A), BRM subunits (Fig. 3B), or Mediator subunits (Fig. S3A,B). Expression of th, monitored using anti-Diap1 antibodies, was also reduced by knockdown of GAF (Fig. 3C), BRM subunits (Figs. 3D, S2M,N, S3C,D), or Mediator subunits (Figs. 3E, S3E,F). ban expression was monitored using a sensor, bs-GFP, in which ban target sites are present in the 3′UTR of a GFP transgene (Brennecke et al., 2003). bs-GFP expression was upregulated by knock-down of GAF or Mediator (Figs. 3C,E, S3E,F), which indicates that ban expression was reduced, and this effect was comparable to that induced by knockdown of Yki (Fig. S3G). For Brm complex subunits, only subtle effects on bs-GFP expression were observed when RNAi lines were expressed under en-Gal4 control (Figs. 3D, S3C,D), but increased bs-GFP expression was obvious when RNAi lines were expressed in clones under AyGal4 control (Fig. S2M,N). In sum, three well established direct targets of Yki are all dependent upon GAF, BRM, and Mediator for their normal expression.

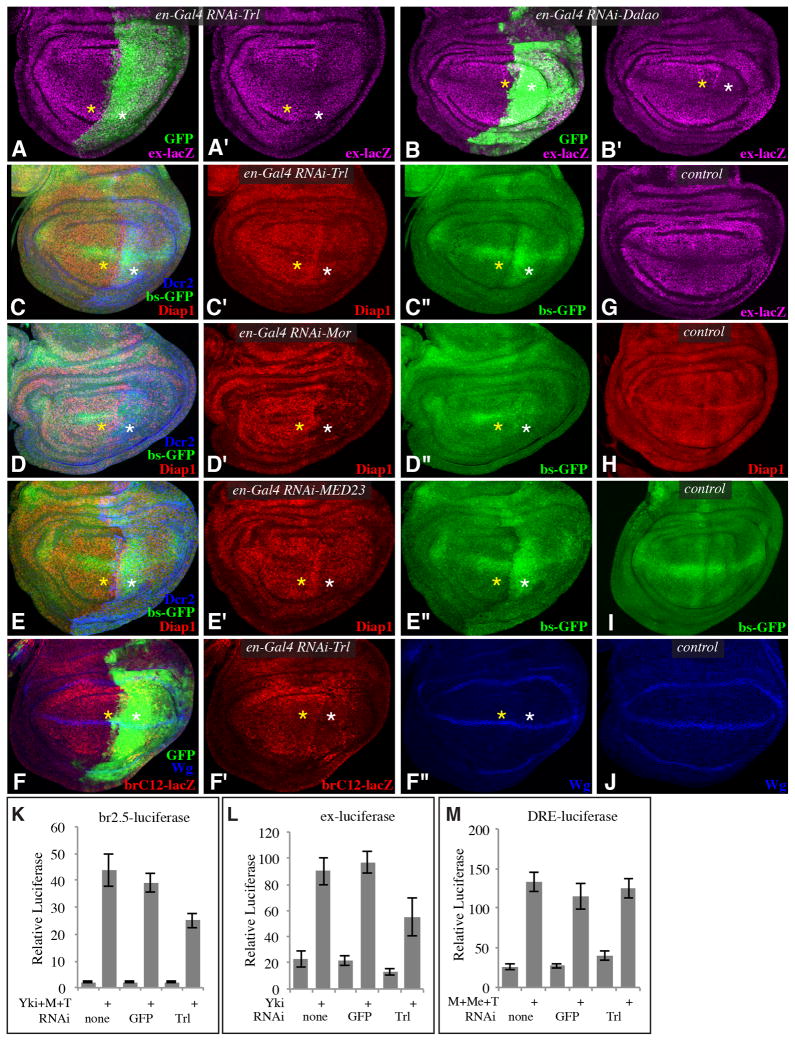

Fig. 3. Influence of GAF, BRM, and Mediator on Yki target genes.

A–J) Projections through 3–5 confocal sections of wing discs; panels marked by prime symbols show separated channels. Yellow asterisks identify regions with normal gene expression, white asterisks identify regions with expression of RNAi lines and altered target gene expression. A–B) en-Gal4 UAS-GFP ex-lacZ UAS-Dcr2, with (A) UAS-RNAi-Trl[vdrc106433] (B) UAS-RNAi-Dalao[TRiP.JF02116] showing expression of ex-lacZ (magenta), and with posterior cells marked by GFP (green). C–E) en-Gal4 bs-GFP; UAS-Dcr2 and with (C) UAS-RNAi-Trl[vdrc106433], (D) UAS-RNAi-Mor[vdrc110712], (E) UAS-RNAi-MED23[vdrc105247], showing expression of Diap1 (red) and bs-GFP (green), and with posterior cells marked by Dcr2 (blue). F) en-Gal4 UAS-GFP; UAS-RNAi-Trl[vdrc106433] UAS-Dcr2 brC12-lacZ, showing expression of brC12-lacZ (red) and Wg (blue), and with posterior cells marked by GFP (green). G) Wild type control showing expression of ex-lacZ (magenta). (H) Wild type control showing expression of Diap1(red). (I) Wild type control showing expression of bs-GFP (green). J) Wild type control showing expression of Wg (blue). K–M) Histograms showing results of luciferase assays (depicted as average firefly/renilla ratio from triplicate experiments, error bars indicate standard deviation) K) using br2.5-luciferase, L) ex-luciferase, M) DRE-luciferase, reporters in S2 cells transfected to express Yki, TkvQ235D (T), Mad (M) or Medea (Me) as indicated. dsRNAs for RNAi against the specific genes were also added as indicated. See also Figs S2,S3.

The requirement for GAF in the expression of ex, th, and ban confirms that the overlap of Yki and GAF binding regions on chromatin, and their physical interaction, are reflective of a functional requirement for GAF in the expression of these key Yki targets. Moreover, other genes that are not direct targets of Yki, such as dorsal-ventral boundary Wingless (Wg), were not significantly reduced by Trl RNAi (Fig. 3F). We also extended our analysis of GAF by showing that a minimal ban reporter, brC12-lacZ, that responds directly to Yki and Mad (Oh and Irvine, 2011), was also downregulated by Trl RNAi (Fig. 3F) and that Trl clones also exhibit decreased Diap1 levels (Fig. S2K,L).

These in vivo studies were complemented by transcriptional assays in S2 cells. We used two previously characterized reporters: a ban reporter that is activated by Yki through Mad (br2.5-luciferase)(Oh and Irvine, 2011), and a reporter that is regulated by a Yki:Gal4 DNA binding domain fusion protein (Yki:Gal4DBD, UAS-luciferase)(Oh and Irvine, 2009). In addition, we identified a Yki-responsive enhancer upstream of ex, and used this to create an ex-luciferase reporter. For a non-Yki-responsive reporter, we used a Dpp-pathway responsive enhancer from Ubx (DRE-luciferase) (Oh and Irvine, 2011). Reduction of GAF levels by Trl RNAi reduced Yki-mediated activation of both the ban and ex reporters (Fig. 3K,L). UAS-luciferase was not significantly affected by Trl RNAi (Fig. S3H), but the ChIP analysis implies that GAF does not act at all Yki target genes. The non-Yki-responsive reporter (DRE-luciferase) was also not affected by Trl RNAi (Fig. 3M). To assess requirements for BRM, we assayed the effects of RNAi-mediated knockdown of the same three subunits examined in vivo: Dalao, Mor, and Brm. Significant reductions were observed for both the ban reporter and UAS-luciferase (Fig. S3I,J). These reporter assays further support the conclusion that GAF and BRM contribute to Yki-mediated transcriptional activation.

Activated-Yki requires GAF, BRM, and Mediator

To further investigate the requirement for GAF, BRM, and Mediator in Yki-mediated transcription, we examined Yki target genes under conditions where Yki activity was elevated, either through reduction of Wts levels, or through expression of an activated form of Yki (YkiS250A) (Oh and Irvine, 2009). The increased expression of Diap1 or ban normally observed in the presence of activated Yki (Fig. 4A,D) was either partially or completely suppressed when GAF, BRM, or Mediator subunits were downregulated by RNAi (Figs. 4, S4). Thus, GAF, BRM, and Mediator all contribute to Yki-mediated transcriptional activation in vivo. Moreover, these experiments provide genetic evidence that these genes act at or below the level of Yki, rather than on upstream components of the Hippo pathway, consistent with their identification as nuclear co-factors of Yki.

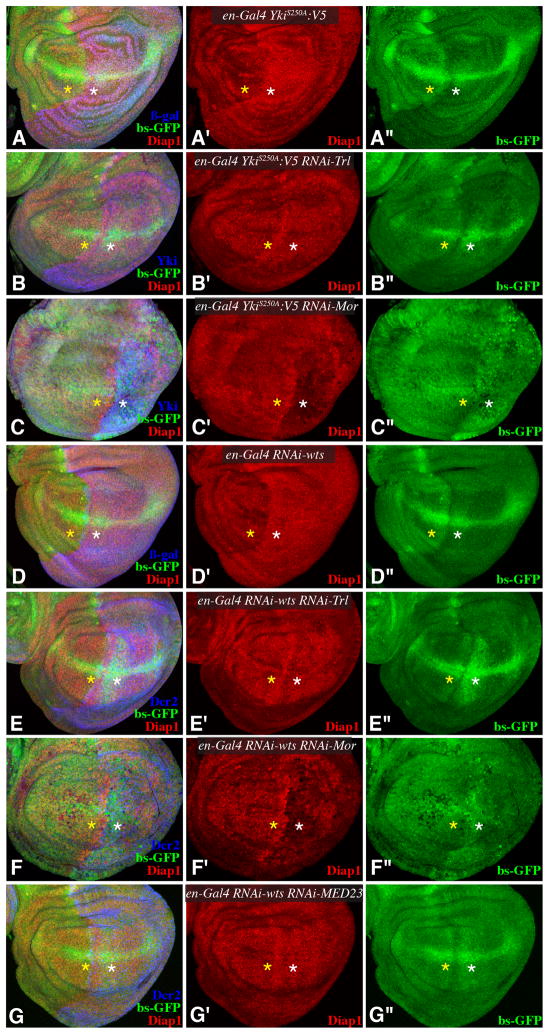

Fig. 4. GAF, BRM, and Mediator are required for Yki activity.

Projections through 3–5 confocal sections of wing discs; panels marked by prime symbols show separated channels. Yellow asterisks identify regions with normal gene expression, white asterisks identify regions with expression of RNAi lines and altered target gene expression. A–C) en-Gal4 bs-GFP; UAS-Yki:V5S250A UAS-Dcr2 and with (A) UAS-lacZ (control) (B) UAS-RNAi-Trl[vdrc106433], (C) UAS-RNAi-Mor[vdrc110712], showing expression of Diap1 (red) and bs-GFP (green), and with posterior cells marked by Yki (blue). D–G) en-Gal4 bs-GFP; UAS-RNAi- wts[vdrc9928] UAS-Dcr2 and with (D) UAS-lacZ (E) UAS-RNAi-Trl[vdrc106433], (F) UAS-RNAi-Mor[vdrc110712] or (G) UAS-RNAi-MED23[vdrc105247], showing expression of Diap1 (red) and bs-GFP (green), and with posterior cells marked by Dcr2 (blue). See also Fig. S4.

DISCUSSION

Molecular mechanisms underlying the transcriptional activation of target genes by Yki have remained ill-defined. We have remedied this by identifying multiple nuclear co-factors of Yki’s transcriptional activity: GAF, BRM, and Mediator. Our discovery of the association of Yki with GAF and BRM establishes a direct connection between Yki and chromatin remodeling complexes, thus identifying direct linkage to chromatin remodeling complexes as a mechanism by which Yki promotes transcription. The linkage of Yki to chromatin remodeling is further supported by the observation that wts mutations can influence position effect variegation (Fig. S1).

The interaction between Yki and BRM is mediated by the BRM subunit Mor, which binds directly to Yki. BRM is broadly required for gene activation in Drosophila (Armstrong et al., 2002), and homologous SWI/SNF complexes are broadly required for transcriptional activation in other eukaryotes (Martens and Winston, 2003). These complexes promote transcription by remodeling nucleosomes. Our biochemical and genetic studies identify the recruitment of BRM as a crucial aspect as Yki’s transcriptional activity, and this link between them is intriguing in light of the biological processes to which both chromatin regulators and Yki/Yap activity have been linked, including the growth of diverse tumors, stem cell maintenance and pluripotency, and regeneration.

The requirement for GAF further stresses the importance of chromatin remodeling to Yki activity, as well as suggesting additional mechanisms by which Yki promotes transcription. GAF is a multifunctional co-factor: it has been linked to chromatin remodeling through interactions with NURF (Tsukiyama and Wu, 1995) and FACT (Shimojima et al., 2003), and it has also been linked to the general transcriptional machinery (Chopra et al., 2008), and looping (Agelopoulos et al., 2012). GAF may combine multiple functions in a single regulatory structure. Indeed, a model was proposed in which nucleosome displacement by GAF would make DNA recognition sites of activators or repressors accessible, and then these proteins would act in conjunction with GAF to recruit transcriptional machinery (Lehmann, 2004). Although GAF has only been intensively studied in Drosophila, the vertebrate c-Krox/Th-POK has been proposed as functional homologue (Matharu et al., 2010) and it will be interesting to see if it has a role in vertebrate Hippo pathways.

Considering that Yki interacts with protein complexes involved at different steps of activation, Yki may play multiple roles to coordinate and integrate these steps. We propose that Yki is recruited to specific loci through sequence-specific DNA-binding partners. Yki and GAGA may reinforce each others localization to chromosomal sites through their binding to each other, and also their recruitment of chromatin remodeling complexes, which could make DNA binding sites more accessible. Yki and GAF could then each contribute to recruitment of additional transcriptional co-activators, Mediator, and the general transcriptional machinery, with this recruitment further facilitated by the nucleosome remodeling activities of BRM and NURF.

Studies of how Yki promotes growth have focused on specific target genes with known roles in promoting growth and cell cycle progression, and inhibiting apoptosis (Oh and Irvine, 2010). However, characterization of Yki’s localization to chromatin suggests that Yki may have thousands of direct targets. Yki is directly associated with thousands of chromosomal loci, and both global transcriptional analysis, and H3K4me3 modification patterns, indicate that the bulk of this Yki localization is correlated with increased transcription. Thus, we infer that Yki is involved in transcriptional activation on a genome-wide scale. This suggests a distinct perspective on how Yki effects its core biological function of promoting growth. We speculate that in addition to activating select growth loci, Yki’s role as a growth promoter might stem also from an ability to induce a broad increase in cellular transcription. Increased growth requires an increase in cellular mass, which implies an increased need for thousands of cellular constituents. Indeed, the crucial role of Myc in promoting growth is thought to stem in part from its role in promoting the expression of ribosomal proteins (van Riggelen et al., 2010), and thereby increasing cellular mass through a global increase in cellular translation. Moreover, recent studies of Myc have also indicated that it induces a global increase in transcriptional activation (Lin et al., 2012; Nie et al., 2012). A widespread increase in cellular transcription, induced by Yki, might similarly promote growth by contributing to the increased cellular mass necessary to sustain increased growth rates.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Drosophila crosses

Flies were cultured at 25°C or 29°C. Ectopic expression was induced in eyes using GMR-Gal4 and posterior cells using en-Gal4 UAS-GFP or en-Gal4 bs-GFP with or without UAS-dcr2 and with or without UAS-lacZ. For flip-out ectopic expression clones, UAS-transgenes with y w hs-FLP[122] were crossed to w; Act> y+>Gal4 bs-GFP (AyGal4-bs-GFP) or AyGal4,UAS-GFP. For MARCM experiments, y w hs-FLP[122] tub-Gal4 UAS-GFP;tub-Gal80 FRT80B was crossed to hs-FLP[122]; UAS-P35; P[lacW]Trls2325 FRT80B/TM6B.

Histology and imaging

Imaginal discs were fixed and stained as described previously (Cho and Irvine, 2004), using as primary antibodies rabbit anti-Yki (1:400) (Oh and Irvine, 2008), mouse anti-Wg (1: 800, DSHB), rabbit anti-Dcr2 (1:1600, Abcam), goat anti-β-gal (1:400, Biogenesis), active caspase3 (1: 400, Cell Signaling), and mouse anti-Diap1 (1:400, gift of Bruce Hay). Fluorescent stains were captured on a Leica TCS SP5 confocal.

ChIP-seq and RNA-seq data is available under GEO accession number GSE38594

Additional experimental details are in the Supplemental Material.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

We identify nuclear partners of Yki for transcriptional activation

Yki directly associates with chromatin remodeling complexes

We identify Yki associated chromatin in vivo

Yki directly associates with and appears to regulate thousands of genes

Acknowledgments

We thank B. Hay, C.P. Verrijzer, T. Xu, the DSHB and the Bloomington Stock Center for antibodies and Drosophila stocks, Flybase, Dibyendu Kumar, and the Waksman Genomics Core for bioinformatics and sequencing support. This research was supported by HHMI, and NIH grants GM078620 (KDI), 5R01GM054510 (RSM), 5P50GM081892 and 3U01HG004264 (KPW).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Adkins NL, Hagerman TA, Georgel P. GAGA protein: a multi-faceted transcription factor. Biochem Cell Biol. 2006;84:559–567. doi: 10.1139/o06-062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agelopoulos M, McKay DJ, Mann RS. Developmental regulation of chromatin conformation by Hox proteins in Drosophila. Cell reports. 2012;1:350–359. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2012.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armstrong JA, Papoulas O, Daubresse G, Sperling AS, Lis JT, Scott MP, Tamkun JW. The Drosophila BRM complex facilitates global transcription by RNA polymerase II. EMBO J. 2002;21:5245–5254. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdf517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brennecke J, Hipfner D, Stark A, Russell R, Cohen SM. bantam encodes a developmentally regulated microRNA that controls cell proliferation and regulates the proapoptotic gene hid in Drosophila. Cell. 2003;113:25–36. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00231-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho E, Irvine KD. Action of fat, four-jointed, dachsous and dachs in distal-to-proximal wing signaling. Development. 2004;131:4489–4500. doi: 10.1242/dev.01315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chopra VS, Srinivasan A, Kumar RP, Mishra K, Basquin D, Docquier M, Seum C, Pauli D, Mishra RK. Transcriptional activation by GAGA factor is through its direct interaction with dmTAF3. Dev Biol. 2008;317:660–670. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2008.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong J, Feldmann G, Huang J, Wu S, Zhang N, Comerford SA, Gayyed MF, Anders RA, Maitra A, Pan D. Elucidation of a universal size-control mechanism in Drosophila and mammals. Cell. 2007;130:1120–1133. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.07.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eissenberg JC, Shilatifard A. Histone H3 lysine 4 (H3K4) methylation in development and differentiation. Dev Biol. 2010;339:240–249. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2009.08.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elfring LK, Daniel C, Papoulas O, Deuring R, Sarte M, Moseley S, Beek SJ, Waldrip WR, Daubresse G, DePace A, et al. Genetic analysis of brahma: the Drosophila homolog of the yeast chromatin remodeling factor SWI2/SNF2. Genetics. 1998;148:251–265. doi: 10.1093/genetics/148.1.251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farkas G, Gausz J, Galloni M, Reuter G, Gyurkovics H, Karch F. The Trithorax-like gene encodes the Drosophila GAGA factor. Nature. 1994;371:806–808. doi: 10.1038/371806a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halder G, Carroll SB. Binding of the Vestigial co-factor switches the DNA-target selectivity of the Scalloped selector protein. Development (Cambridge, England) 2001;128:3295–3305. doi: 10.1242/dev.128.17.3295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Justice RW, Zilian O, Woods DF, Noll M, Bryant PJ. The Drosophila tumor suppressor gene warts encodes a homolog of human myotonic dystrophy kinase and is required for the control of cell shape and proliferation. Genes Dev. 1995;9:534–546. doi: 10.1101/gad.9.5.534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehmann M. Anything else but GAGA: a nonhistone protein complex reshapes chromatin structure. Trends Genet. 2004;20:15–22. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2003.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li B, Carey M, Workman JL. The role of chromatin during transcription. Cell. 2007;128:707–719. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin CY, Lovén J, Rahl PB, Paranal RM, Burge CB, Bradner JE, Lee TI, Young RA. Transcriptional Amplification in Tumor Cells with Elevated c-Myc. Cell. 2012;151:56–67. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.08.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malik S, Roeder RG. The metazoan Mediator co-activator complex as an integrative hub for transcriptional regulation. Nat Rev Genet. 2010;11:761–772. doi: 10.1038/nrg2901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martens JA, Winston F. Recent advances in understanding chromatin remodeling by Swi/Snf complexes. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2003;13:136–142. doi: 10.1016/s0959-437x(03)00022-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matharu NK, Hussain T, Sankaranarayanan R, Mishra RK. Vertebrate homologue of Drosophila GAGA factor. Journal of Molecular Biology. 2010;400:434–447. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2010.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicolay BN, Bayarmagnai B, Islam ABMMK, Lopez-Bigas N, Frolov MV. Cooperation between dE2E1 and Yki/Sd defines a distinct transcriptional program necessary to bypass cell cycle exit. Genes and Development. 2011;25:323–335. doi: 10.1101/gad.1999211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nie Z, Hu G, Wei G, Cui K, Yamane A, Resch W, Wang R, Green DR, Tessarollo L, Casellas R, et al. c-Myc Is a Universal Amplifier of Expressed Genes in Lymphocytes and Embryonic Stem Cells. Cell. 2012;151:68–79. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.08.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oh H, Irvine KD. In vivo regulation of Yorkie phosphorylation and localization. Development. 2008;135:1081–1088. doi: 10.1242/dev.015255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oh H, Irvine KD. In vivo analysis of Yorkie phosphorylation sites. Oncogene. 2009;28:1916–1927. doi: 10.1038/onc.2009.43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oh H, Irvine KD. Yorkie: the final destination of Hippo signaling. Trends in Cell Biol. 2010;20:410–417. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2010.04.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oh H, Irvine KD. Cooperative regulation of growth by Yorkie and Mad thgrough bantam. Developmental Cell. 2011;20:109–122. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2010.12.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng HW, Slattery M, Mann RS. Transcription factor choice in the Hippo signaling pathway: homothorax and yorkie regulation of the microRNA bantam in the progenitor domain of the Drosophila eye imaginal disc. Genes Dev. 2009;23:2307–2319. doi: 10.1101/gad.1820009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pérez-Lluch S, Blanco E, Carbonell A, Raha D, Snyder M, Serras F, Corominas M. Genome-wide chromatin occupancy analysis reveals a role for ASH2 in transcriptional pausing. Nucleic Acids Research. 2011;39:4628–4639. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq1322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimojima T, Okada M, Nakayama T, Ueda H, Okawa K, Iwamatsu A, Handa H, Hirose S. Drosophila FACT contributes to Hox gene expression through physical and functional interactions with GAGA factor. Genes Dev. 2003;17:1605–1616. doi: 10.1101/gad.1086803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Subramanian A, Tamayo P, Mootha VK, Mukherjee S, Ebert BL, Gillette MA, Paulovich A, Pomeroy SL, Golub TR, Lander ES, et al. Gene set enrichment analysis: a knowledge-based approach for interpreting genome-wide expression profiles. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:15545–15550. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0506580102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terriente-Félix A, López-Varea A, de Celis JF. Identification of genes affecting wing patterning through a loss-of-function mutagenesis screen and characterization of med15 function during wing development. Genetics. 2010;185:671–684. doi: 10.1534/genetics.109.113670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsukiyama T, Wu C. Purification and properties of an ATP-dependent nucleosome remodeling factor. Cell. 1995;83:1011–1020. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90216-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Riggelen J, Yetil A, Felsher DW. MYC as a regulator of ribosome biogenesis and protein synthesis. Nature Reviews Cancer. 2010;10:301–309. doi: 10.1038/nrc2819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varelas X, Sakuma R, Samavarchi-Tehrani P, Peerani R, Rao BM, Dembowy J, Yaffe MB, Zandstra PW, Wrana JL. TAZ controls Smad nucleocytoplasmic shuttling and regulates human embryonic stem-cell self-renewal. Nat Cell Biol. 2008;10:837–848. doi: 10.1038/ncb1748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu S, Liu Y, Zheng Y, Dong J, Pan D. The TEAD/TEF family protein Scalloped mediates transcriptional output of the Hippo growth-regulatory pathway. Dev Cell. 2008;14:388–398. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2008.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang L, Ren F, Zhang Q, Chen Y, Wang B, Jiang J. The TEAD/TEF family of transcription factor Scalloped mediates Hippo signaling in organ size control. Dev Cell. 2008;14:377–387. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2008.01.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao B, Tumaneng K, Guan KL. The Hippo pathway in organ size control, tissue regeneration and stem cell self-renewal. Nat Cell Bio. 2011;13:877–883. doi: 10.1038/ncb2303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.