Abstract

Schizophrenia and related psychotic disorders are associated with significant neuropsychological (NP) impairments. Yet the onset and developmental evolution of these impairments remains incompletely characterized. This study examined NP functioning over one year in a sample of youth at clinical high risk (CHR) for psychosis participating in a treatment study. We assessed functioning across six cognitive domains at two time points in a sample of 53 CHR and 32 healthy comparison (HC) subjects. Linear regression of HC one-year scores was used to predict one-year performance for CHR from baseline scores and relevant demographic variables. We used raw scores and MANOVAs of the standardized residuals to test for progressive impairment over time. NP functioning of CHR at one year fell significantly below predicted levels. Effects were largest and most consistent for a failure of normative improvement on tests of executive function. CHR who reached the highest positive symptom rating (6, severe and psychotic) on the Structured Interview of Prodromal Syndromes after the baseline assessment (n = 10/53) demonstrated a particularly large (d= −1.89), although non-significant, discrepancy between observed and predicted one-year verbal memory test performance. Findings suggest that, although much of the cognitive impairment associated with psychosis is present prior to the full expression of the psychotic syndrome, some progressive NP impairments may accompany risk for psychosis and be greatest for those who develop psychotic level symptoms.

Keywords: prodrome, cognition, longitudinal, schizophrenia, decline, PIER

I. Introduction

Clinicians have long observed a period of apparent decline in functioning prior to psychosis onset (Sullivan, 1927), a period retrospectively recognized as the prodrome to psychosis. Prospective study of this period is possible through recruitment of “clinical high risk” (CHR) samples (McGlashan & Johannessen, 1996; Yung and McGorry, 1996). Identified primarily by the presence of attenuated positive symptoms derived from structured interviews, CHR individuals are at heightened risk for transition to psychosis (mean rates of conversion: 18–36%) within six months to three years (Cannon et al., 2008; Fusar-Poli et al., 2012; Miller et al., 2002; Yung et al., 2003). An important question in prospective research of CHR samples is whether clinical decline is associated with changes in brain and neuropsychological (NP) function.

Longitudinal neuroimaging studies have identified both gray and white matter volume reductions over time in CHR subjects who transitioned to acute psychosis relative to those who did not (Sun et al., 2009; Takahashi et al., 2009; Walterfang et al., 2008). Taken together with observations that post-onset levels of cognitive functioning in schizophrenia are significantly worse than those observed in the premorbid period (Mesholam-Gately et al., 2009; Woodberry et al., 2008) these findings suggest an active process of altered brain function that underlies NP decline and/or failure of normative NP development during the transition to psychosis. The transition to psychosis typically occurs during adolescence and early adulthood, a period important for complete maturation of cortical gray matter, particularly in frontal networks. Pathology during this period might be expected to interrupt NP development, especially of functions dependent on prefrontal cortical (PFC) functioning, such as executive functions (EF, Paus et al., 2008) and episodic memory, which is dependent on spontaneous organization of features for memory encoding (Cirillo and Seidman, 2003).

Although the evidence is not definitive, both cross-sectional and longitudinal studies suggest that progressive NP impairment may accompany the onset of psychosis. Three longitudinal studies that varied in length of follow-up found a decline in intellectual functioning over time in individuals who developed psychosis relative to those who did not (Caspi et al., 2003; Lubin et al., 1962; Seidman et al., 2006). Progressive decline prior to acute psychosis, however, has been less consistently observed (Ang and Tan, 2004; Bilder et al., 2006; Cosway et al., 2000; Fuller et al., 2002; Rabinowitz et al., 2000; Reichenberg et al., 2010; Woodberry et al., 2008). When NP development is found to differ in youth who later develop a psychotic disorder relative to healthy controls, it is often due to a lower rate of growth rather than a decline per se (e.g., Reichenberg et al., 2010).

Six published studies have reported on NP functioning over time in putatively prodromal samples, five of which evaluated longitudinal change in relation to psychosis outcome (Barbato et al., 2012; Becker et al., 2010; Hawkins et al., 2008; Jahshan et. al, 2010; Keefe et al., 2006, Wood et al., 2007). Studies examining composite scores found no significant group-by-time effects for CHR who converted to psychosis versus CHR who did not (Hawkins et al., 2008; Keefe et al., 2006,13 and 11 converters, respectively). Three studies identified similar overall results but noted altered performance trajectories for some individual tests. Significantly lower scores over time were reported for CHR who transitioned to psychosis relative to those who did not on tests of visual memory and visual-spatial processing speed (Wood et al., 2007), working memory (Jahshan et. al, 2010), and verbal memory (Becker et al., 2010). In the first two of these, converters demonstrated a decline in performance over time. However, sample sizes in these studies were small, particularly for converters (7, 6, and 17, respectively). Replication and larger samples are needed to determine the reliability of these findings.

For developmental reasons noted, our interest has been on cortically based NP functions, especially those associated with the PFC, such as EF. Importantly, olfactory identification, another function associated with PFC, although more with ventral (e.g., orbitofrontal cortex, Seidman et al. 1992), than dorsal sections, is reliably impaired in schizophrenia (SCZ). Deficits have been found in two CHR samples (Brewer et al., 2003; Woodberry et al., 2010), with a failure of expected olfactory development being possibly specific to CHR who developed SCZ (Brewer et al., 2003). Yet the developmental course of these deficits remains largely unknown.

The purpose of this study was to examine neuropsychological development over one year in a CHR sample relative to healthy comparisons (HC). Given some preservation of NP function in CHR relative to first episode samples, even in those who later developed psychosis (Giuliano et al., 2012; Keefe et al., 2006; Seidman et al., 2010), we predicted increased NP impairment over time, particularly in those who transitioned to a psychotic level of symptoms. Specifically, we expected a degradation of normal development to be evident in performance on tests reliant on memory, EFs, and olfactory identification.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

The CHR sample consisted of participants, ages 12–25, in a randomized controlled trial of family-aided assertive community treatment (FACT, McFarlane, 1997; McFarlane et al., 2000) through the Portland Identification and Early Referral (PIER) program in Portland, ME. All participants were offered family education, crisis intervention, assertive follow-up, and medication according to indication and protocol. Those randomized to FACT were also offered multifamily psychoeducation, assertive community treatment, and supported employment. Baseline demographics, clinical characteristics, and neuropsychological performance have been reported previously (Woodberry et al., 2010). At baseline, participants had to meet criteria for one of two prodromal syndromes according to the Structured Interview for Prodromal Syndromes (SIPS, Miller et al., 1999). These syndromes included new or worsening Attenuated Positive Symptoms (APS) and Genetic Risk and Deterioration (GRD). We excluded from these longitudinal analyses subjects meeting criteria for a third syndrome, Brief Intermittent Psychotic Symptoms (BIPS), as our aim was to examine cognitive change in the context of progression to psychosis rather than progression to a psychotic disorder. Subjects with BIPS, by definition, are already experiencing psychotic level symptoms, even if only briefly.

The decision to exclude BIPS corresponded with our defining the critical threshold of progression to psychosis as the shift from attenuated level symptoms (i.e., scores of 3 to 5) at baseline to a post-baseline onset of “severe and psychotic” level symptoms on the SIPS (i.e., a positive symptom rating of 6). This rating indicates “conviction (with no doubt) at least intermittently”, and influence on or interference with thinking, feelings, social relations, or behavior. We held that conviction about an altered reality was at the core of what it means to be psychotic, and thus a reasonable outcome criterion measure. Given our expectation that available psychosocial and medication treatments provided by study design might moderate full symptom expression, reducing positive symptom severity, frequency, and/or duration, we did not require a specific frequency or duration of psychotic level symptoms or a specific diagnosis. We identified the group rated at a psychotic level after baseline as “later psychotic”.

Of the 73 CHR participants included in the baseline analysis, five missed their one-year NP assessment, 4 moved away, 3 dropped out of the study, 2 died, and 1 refused testing. The remaining 58 (79%) had NP data appropriate for one-year analyses. As noted above, 5 (10%) with BIPS were excluded. Of the 53 remaining, 50 (94%) met criteria for APS and 9 (17%) for GRD (6 meeting for both APS and GRD). Forty-two (79%) had measures of olfactory identification (Brief Smell Identification Test, BSIT, Doty et al., 1996) and 36 (68%) had a Wechsler Abbreviated Scale for Intelligence (WASI, Two-Subtest, Wechsler, 1999) IQ estimate at both time points. Demographics for these samples are available in Table 1. HC subjects were recruited to be similar to the CHR sample on demographic variables to control for non-illness related factors that might influence the rate and direction of NP change over time. Of the 34 HC included in the baseline analyses, 32 (94%) maintained HC status and had one-year NP data. The clinical trial was formally approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) at Maine Medical Center (MMC). The study assessing CHR and HC NP functioning was formally approved by the IRB at MMC and the Committee on the Use of Human Subjects in Research at Harvard University.

Table 1.

Demographics by Group and Subgroup with Baseline and One-Year NP Data

| HC | CHR with 5 NP Domains at 2 time points | CHR Data Subgroups |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Olfaction at 2 time points | IQ estimate at 2 time points | Never Psychotic | Later Psychotic | |||

| N | 32 | 53 | 42 | 36 | 43 | 10 |

| Age (SD) | 16.3 (2.6) | 16.0 (2.4) | 16.2 (2.5) | 16.2 (2.5) | 16.0 (2.4) | 16.1 (2.1) |

| Male (N/%) | 16 (50) | 26 (49) | 18 (43) | 16 (44) | 21 (49) | 5 (50) |

| Right Handed (N/%) | 28 (88) | 48 (91) | 37 (88) | 31 (86) | 39 (91) | 9 (90) |

| Highest Grade (SD) | 9.3 (2.4) | 9.0 (2.2) | 9.2 (2.3) | 9.2 (2.4) | 9.1 (2.4) | 8.9 (1.7) |

| Parent Highest Grade | 14.8 (1.9) | 14.4 (1.8) | 14.5 (1.6) | 14.4 (1.7) | 14.5 (1.8) | 13.9 (2.0) |

| Median Family Income | $50 – 60K | $50 – 60K | $50 – 60K | $50 – 60K | $50 – 60K | $40 – 50K |

| Caucasian (N/%) | 29 (91) | 47 (89) | 38 (91) | 33 (92) | 37 (86) | 10 (100) |

HC: Healthy Comparison; CHR: Clinical High Risk; CHR Data Subgroups: (overlapping) subsets of CHR sample with longitudinal data on indicated measures; Never Psychotic were never rated at a psychotic level (6 rating on the Structured Interview of Prodromal Syndromes (SIPS) Positive (P) Symptom scale) during the period of follow-up; Later Psychotic met criteria for a 6 rating on a SIPS P-scale after baseline, within the duration of follow-up. There were no significant group differences on any basic demographics.

2.2 Measures

2.2.1. Clinical assessments

All participants were assessed with the SIPS and the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM IV-TR (First et al., 1997) at baseline and one year. The positive (P) symptom subscale of the SIPS was repeated at monthly assessments and upon admission to the hospital or suspicion of psychotic level symptoms. The mean clinical follow-up for the longitudinal CHR sample was 23 months (SD = 2.8).

2.2.2. Neuropsychological assessment battery

NP test scores were assigned to clinically meaningful a priori cognitive domains (see Table 2) based on convention and the literature on cognition in SCZ (e.g., Gur et al., 2007; Nuechterlein et al., 2004). For tests with adult and child versions (California Verbal Learning Test [CVLT], story memory, Letter Number Sequencing), child versions were given to participants under 16 years old, adult versions to those 16 years and older. Follow-up NP assessments were conducted one year after baseline (CHR mean/SD = 12.2/1.0 months; HC mean/SD = 12.5/0.6; t = −1.78, p = 0.079) for all participants. Thus, the proximity of this assessment to psychosis onset varied for those who converted.

Table 2.

Test Variables by Domain

| Domain | Tests and Subtests | Description of Task/Measure |

|---|---|---|

| Premorbid IQ, Estimated | Wide Range Achievement Test (WRAT-3) Reading (Blue) | Accurately read and pronounce single words. |

| Measure: Standard score | ||

| Current IQ, Estimated | Wechsler Abbreviated Scale for Intelligence (WASI): | Measure: Standard scores based on sum of subtest T-scores for two verbal and two nonverbal IQ subtests. |

| Verbal IQ (VIQ) | WASI Vocabulary* | Accurately verbalize the meaning of words. |

| WASI Similarities | Describe how two words/items are alike. | |

| Nonverbal IQ (PIQ) | WASI Block Design | Rapidly assemble blocks into 2-dimensional patterns. |

| WASI Matrix Reasoning* | Identify the correct multiple-choice option to complete a matrix design. | |

| 2 test IQ estimate | Tests denoted with * above | |

| Sustained Attention/ Working Memory: | Continuous Performance Test-Identical Pairs (CPT-IP-II): | Lift finger whenever two stimuli in a row (flashed on a computer screen) are exactly alike. |

| Practice: Numbers (3-digits) | Measure: Mean d' of fast and slow subtests for each domain; d' is a measure of response sensitivity accounting for correct responses and false alarms. | |

| Verbal Attention | Four digits | |

| Nonverbal Attention | Shapes | |

| Verbal Memory | California Verbal Learning Test (CVLT, Version II, ≥ age 16, or Child Version, < age 16) | Recall words from a list of 16 (CVLT-II) or 15 (CVLT-C) words read aloud five times. |

| Measure: Total of trials 1–5, percent of total, T score | ||

| Wechsler Memory Scale-Ill (WMS-III) Logical Memory (≥ age 16) or Children's Memory Scale Stories (CMS, < age 16) | Immediate recall of two short stories read aloud. | |

| Measure: Percent of raw score total, Scaled Score of total units recalled. | ||

| Executive Function | Delis-Kaplan Executive | Measure: Raw or Scaled Scores |

| Function System (D-KEFS) | ||

| Verbal Fluency Condition 3 | Generate as many words as possible in 60-seconds switching back and forth between 2 categories. | |

| Trail Making Condition 4 | Quickly sequence numbers and letters in a two-page array, alternating between numbers and letters. | |

| Wisconsin Card Sorting Test (WCST-128): Computer Version | Match cards on a number of characteristics based on verbal feedback. | |

| Measure: Perseverative errors Raw | ||

| WMS-III (≥ 16) or Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children-IV (WISC-IV, <16) | Repeat a sequence of numbers and letters read aloud after mental resequencing. | |

| Letter-Number Sequencing | Measure: Percent of total, Scaled Score | |

| Motor | Finger Tapping Test | Tap a lever as fast as possible with the index finger of each hand over 10 second trials. |

| Measure: Mean # of taps across trials | ||

| Olfaction | Brief Smell Identification Test (B-SIT) | Choose one of four choices identifying each of 12 odors in a scratch and sniff booklet |

| Measure: # correct |

Domains are in bold. IQ and Sustained Attention/Working Memory are listed in conjunction with broad category tests from which verbal and nonverbal domains were obtained. Standard and Scaled Scores are based on age-based normative data provided for selected tests. Raw or “percent of total” scores were entered into regression analyses for all tests except IQ. Citations for tests are: WRAT-3 (Wilkinson, 1993); WASI (Wechsler, 1999); CPT-IP-II (Cornblatt and Keilp, 1994); WCST (Heaton, 1981); D-KEFS (Delis et al, 2001); WMS-III (Wechsler, 1997); WISC-IV (Wechsler, 2003); CMS (Cohen 1997); CVLT-II (Delis et al., 2000); CVLT-C (Delis et al., 1994); Finger Tapping Test (Reitan and Wolfson, 1993); B-SIT, a brief version of the University of Pennsylvania Smell Identification Test (UPSIT, Doty et al., 1984, 1996).

2.3. Data Analysis

Data distributions for all analyses were assessed for normality and outliers by group and subgroup. WCST perseverative errors and D-KEFS Trail Making Test time were log transformed. Adjustments to the baseline data (Woodberry et al., 2010) were maintained. Univariate outliers in the one-year sample at either time point were adjusted to one unit beyond the next closest value in the group distribution (Tabachnick and Fidell, 2001). In two cases, corresponding scores at either baseline or one-year were also adjusted to maintain the nature of change for the case (stability, gain, loss).

Independent t tests and Chi-square tests were used to compare demographic and baseline neurocognitive data. To identify abnormalities in NP development over time, we used linear regression, consistent with recommendations and similar analyses (Heaton et al., 2001; Jahshan et. al, 2010; Temkin et al., 1999). This method allowed us to take into account factors expected to influence NP performance over time. We entered baseline raw scores, age, sex, mean parental education, and months between baseline and one-year testing into SPSS v.16 linear regression to select predictors of HC one-year NP test scores. A subgroup (N = 18) was assessed with child measures at baseline and adult measures at one year. A binary variable indicating whether the same or different measure was used at both time points was entered into regression equations for tests with child and adult versions.

Regression parameters for each test were used to calculate predicted scores. Residual (predicted minus observed) scores were standardized such that the HC mean was zero and SD was one. The sign of WCST perseverative errors and Trail Making time was reversed so higher scores reflected better performance on all tests. Neurocognitive domain scores for memory and EF domains were calculated as the mean standardized residual scores of tests within each domain and then re-standardized on the HC sample. An overall mean standardized residual (MSR) score was calculated across the five domains of verbal and nonverbal attention, memory, EF, and motor function. We used MANOVA to examine group differences in standardized residual scores across domains. As the pattern of results for six domains using the smaller sample with two IQ estimates was similar to that of five domains in the larger sample, statistics from the larger sample are reported. MANOVA was repeated for comparison of groups that did and did not develop psychotic symptoms over the course of clinical follow-up. To examine the possible role of treatment on our findings we 1) conducted bivariate correlations of medication status with NP performance, 2) repeated primary outcome analyses controlling for estimated days on antipsychotic and mood stabilizer medications between baseline and one year, and 3) examined NP outcomes by treatment condition.

We used Mann-Whitney U tests for any domain or subtest for which there were significant group differences in covariance matrices or error variances. Greenhouse-Geisser values were reported when assumptions of sphericity were violated. Due to the restricted range of HC scores, nonparametric tests and descriptive statistics were employed to examine olfactory identification change. For a more complete description of results, two-tailed independent t tests are reported in Table 3. Bonferroni adjustments were not made for these tests given their descriptive purpose.

Table 3.

Neuropsychological Data by Group

| HC(N = 32) | CHR Never Psychotic (N = 43) | CHR Later Psychotic (N = 10) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | One Year | Baseline | One Year | Baseline | One Year | |

| WRAT-3 Reading SS | 105.2 (12.0) | 104.0 (11.0) | 105.6 (11.0) | |||

| WASI 4 test FSIQ | 110.0 (10.8) | 103.8 (12.8) | 97.9 (11.7) | |||

| WASI 2 test FSIQ | 108.9 (11.3) | 111.5 (11.5) | 104.6 (12.7) | 108.1 (13.2) | 90.4 (9.2)* | 97.4 (7.9) |

| WASI VIQ | 111.5 (13.1) | 105.2 (12.6) | 95.7 (14.7) | |||

| WASI PIQ | 106.0 (9.7) | 101.7 (14.8) | 100.0 (11.0) | |||

| CPT-IP Verbal d' | 1.38 (0.57) | 1.57 (0.69) | 1.33 (0.69) | 1.62 (0.80) | 1.44 (0.53) | 1.70 (0.90) |

| CPT-IP Nonverbal d' | 2.09 (0.82) | 2.27 (0.75) | 1.91 (0.77) | 2.22 (0.92) | 1.72 (0.61) | 2.04 (0.74) |

| Mean % Memory | 0.68 (0.08) | 0.69 (0.08) | 0.64 (0.14) | 0.62 (0.16)* | 0.57 (0.12) | 0.54 (0.12)*** |

| Mean Exe Function ScS | 11.2 (1.3) | 11.7 (1.5) | 10.2 (1.8) | 10.1 (2.1)*** | 9.7 (1.6) | 9.9 (1.8)** |

| D-KEFS Trails 4 Raw | 69.4 (19.5) | 60.3 (18.6) | 78.1 (38.4) | 77.5 (40.0)* | 79.3 (21.1) | 78.3 (21.6)* |

| D-KEFS Trails 4 ScS | 9.9 (1.8) | 10.7 (1.9) | 9.4 (2.9) | 9.2 (3.3)* | 8.9 (2.1) | 8.7 (2.4)* |

| D-KEFS Verb Flu Raw | 14.0 (2.6) | 13.7 (2.6) | 13.0 (2.2) | 12.6 (2.9) | 12.3 (2.4) | 11.4 (3.0)* |

| D-KEFS Verb Flu ScS | 11.8 (3.1) | 11.0 (3.0) | 10.7 (2.5) | 9.9 (3.4) | 9.7 (3.2) | 8.3 (3.4)* |

| WCST Pers Err Raw | 8.9 (6.8) | 5.7 (2.0) | 13.5 (10.5)* | 10.2 (7.6)*** | 13.8 (9.5) | 9.5 (9.3) |

| WCST Pers Err SS | 114.4 (15.9) | 122.7 (11.5) | 104.5 (18.4)* | 111.2 (18.5)** | 102.9 (17.2) | 113.4 (17.6) |

| Mean Finger Tapping | 46.1 (5.6) | 48.2 (6.1) | 43.8 (7.4) | 46.3 (6.9) | 43.9 (7.0) | 46.3 (6.0) |

| Mean Dominant | 48.1 (6.2) | 50.6 (6.3) | 45.9 (8.4) | 48.5 (7.3) | 47.5 (7.0) | 49.2 (6.6) |

| Mean Nondominant | 44.1 (5.7) | 45.9 (6.8) | 41.4 (8.1) | 44.1 (7.3) | 40.3 (7.6) | 43.4 (5.9) |

| BSIT Olfaction Raw † | 11.0 (0.7) | 10.9 (0.8) | 10.0 (1.5) | 10.3 (1.4)* | 9.33 (2.2) | 9.7 (1.3)** |

| Child Tests Only | ||||||

| N, Age (SD) | 9, 13.6 (1.0) | 14.6 (1.0) | 18, 13.9 (1.0) | 14.9 (1.0) | 3, 13.6 (1.2) | 14.6 (1.2) |

| CVLT-C Trial 1–5 R CVLT-C Trial 1–5 T |

55.2 (3.1) 55.2 (4.4) |

54.9 (7.5) 53.3 (9.9) |

49.0 (10.4) 46.7 (13.4) |

47.4 (12.3) 43.5 (15.5) |

50.0 (7.2) 48.3 (9.9) |

44.3 (8.1) 39.3 (11.6) |

| CMS Stories R CMS Stories ScS |

50.8 (16.0) 11.9 (3.0) |

54.3 (15.0) 12.9 (3.6) |

47.6 (18.2) 11.3 (4.2) |

42.6 (16.6) 10.5 (3.9) |

46.3 (21.6) 10.3 (5.8) |

36.3 (22.7) 9.0 (4.4) |

| WISC-IV LNS R WISC-IV LNS ScS |

19.0 (1.6) 10.7 (1.2) |

20.2 (1.8) 11.1 (1.9) |

18.4 (1.6) 10.0 (1.3) |

17.6 (2.3) 8.6 (2.1) |

17.0 (3.0) 9.0 (2.0) |

19.3 (3.2) 10.7 (3.1) |

| Adult Tests Only | ||||||

| N, Age (SD) | 16, 18.2 (2.1) | 19.3 (2.1) | 16, 18.6 (1.8) | 19.6 (1.8) | 5, 17.6 (1.2) 4, 18.0 (1.0) |

18.6 (1.4) 19.1 (1.1) |

| CVLT-II Trial 1-5 R | 58.0 (5.6) | 58.6 (6.4) | 53.9 (13.6) | 53.0 (15.0) | 48.4 (8.9) | 48.0 (4.8) |

| CVLT-II Trial 1-5 T | 55.1 (6.4) | 55.7 (7.3) | 51.1 (15.5) | 50.0 (16.6) | 44.4 (11.3) | 44.4 (4.3) |

| WMS Log Mem R WMS Log Mem ScS |

47.3 (6.8) 11.0 (2.0) |

48.4 (8.9) 11.2 (2.3) |

46.9 (10.1) 10.8 (3.2) |

46.2 (15.8) 11.1 (4.2) |

40.0 (17.7)

8.5 (5.0) |

38.8 (17.7)

9.0 (5.0) |

| WMS-III LNS R WMS-III LNS ScS |

10.9 (2.5) 9.8 (2.6) |

11.3 (2.9) 10.2 (3.0) |

11.0 (3.1) 9.8 (3.4) |

10.8 (3.0) 9.8 (3.2) |

10.8 (1.9)

9.8 (1.9) |

11.0 (2.2)

10.0 (2.2) |

| Child/Adult Transition | ||||||

| N, Age (SD) | 7, 15.3 (0.3) | 16.3 (0.3) | 9, 15.6 (0.3) | 16.7 (0.3) | 2, 15.9 (0.1) 3, 15.9 (0.1)a |

16.9 (0.1) 16.9 (0.1) |

| CVLT-C/II Trial 1–5 R | 55.6 (4.6) | 59.6 (8.2) | 59.6 (6.3) | 57.4 (7.6) | 46.0 (11.3)a | 47.5 (14.8) |

| CVLT-C/II Trial 1–5 T | 53.4 (5.9) | 58.4 (9.8) | 58.3 (7.7) | 54.3 (7.9) | 41.0 (15.6)a | 43.5 (14.8) |

| CMS/WMS Stories R | 57.7 (14.6) | 48.6 (4.0) | 56.0 (9.9) | 50.4 (9.5) | 39.7 (19.1) | 37.0 (15.7) |

| CMS/WMS Stories ScS | 14.0 (3.4) | 11.0 (1.2) | 13.2 (2.3) | 11.8 (2.9) | 9.7 (4.0) | 7.3 (4.9) |

| WISC/WMS LNS R | 19.6 (3.7) | 12.3 (3.0) | 19.9 (3.1) | 10.9 (2.0) | 20.3 (0.6) | 10.7 (0.6) |

| WISC/WMS LNS ScS | 10.1 (3.7) | 10.9 (3.5) | 10.2 (3.5) | 9.3 (2.5) | 10.3 (0.6) | 9.3 (1.2) |

HC: Healthy Comparison; CHR: Clinical High Risk; Never Psychotic: never rated as Psychotic on Structured Interview of Prodromal Syndromes (SIPS) positive (P) scale within duration of follow-up; Later Psychotic: rated Psychotic on SIPS P-scale after baseline testing. Standardized scores are provided when adequate normative data are available to facilitate comparison of scores on child and adult measures of a test; T: T score; SS: Standard Score; ScS: Scaled Score; 4 test FSIQ: estimated full scale IQ based on 4 Subtests of the WASI; 2 test FSIQ: WASI Two-Subtest estimate of full scale IQ; CMS/WMS Stories: Child Memory Scale Stories/ Wechsler Memory Scale Logical Memory I. One later psychotic participant who had just turned 16 years old at baseline, was accidentally given the CMS and WISC Letter Number Sequencing rather than the WMS Logical Memory and Letter Number Sequencing; thus the N's for these tests differ from those for CVLT in the adult-adult and child-adult subgroups. Italicized N's and ages are associated with the italicized mean scores below, within that column.

N = 42 for the CHR sample

p < 0.05

p < 0.01

p < 0.001 relative to HC on independent t tests without Bonferroni correction.

p < 0.05 relative to CHR Never Psychotic on independent t tests without Bonferroni correction.

3. Results

3.1. Longitudinal CHR Sample Characterization

HC and CHR participants did not differ significantly on age, gender distribution, handedness, highest grade completed, parent education, family income, or racial distribution (see Table 1). This remained true for the smaller subgroups as well. CHR with longitudinal data (CHR-L) had statistically similar parental education, gender, handedness, and racial distributions, and median family income as CHR with only baseline data (CHR-B, N = 15). However, CHR-B were significantly older (mean age = 17.9, SD = 3.1, p = 0.016) and had higher education (10.9, SD = 3.1, p = 0.01). Baseline WRAT-3 Reading, WASI IQ estimates, and NP domain scores were statistically similar across groups.

3.2. Neuropsychological Performance at One Year in the Overall CHR Sample

We hypothesized progressive NP impairment in CHR relative to HC, particularly on tests tapping executive, memory, and olfactory functions, and in those who developed psychotic symptoms after baseline assessment. We found no evidence for progressive impairment in IQ over one year in the CHR sample. IQ estimates were significantly larger at one year relative to baseline for both groups (p = 0.001, see Table 3). Contrary to predictions, olfactory identification in CHR actually improved at one year relative to baseline performance and relative to overall stable performance in HC (Mann-Whitney U test of change scores by group: p = 0.039).

Consistent with our hypothesis, CHR had significantly lower overall NP functioning than predicted at year one (ηp2= 0.257, p < 0.001, MSR group t = −2.71, p = 0.008). Furthermore, CHR EF and memory domain scores at one year were significantly below predicted levels (Mann-Whitney U, p = 0.001 and p = 0.002, respectively). Performance on sustained attention and motor functioning was not significantly different between groups (ps ≥ 0.88).

Analyses of specific tests within the EF domain revealed significantly lower than predicted gains on Trail Making (Mann-Whitney U, p = 0.016) and WCST perseverative errors (Mann-Whitney U, p = 0.007) for CHR. On memory subtests, the CHR sample not only failed to show predicted improvement over time, age, and practice, but demonstrated a slight decline from baseline. Their percent recall at year one was significantly below predicted values on the CVLT (Mann-Whitney U, p = 0.011) and nearly significantly below predicted values on immediate story memory (Mann-Whitney U, p = 0.051).

3.3. NP Performance at One Year for Group Developing Psychotic Symptoms

Ten CHR developed severe and psychotic level symptoms after baseline assessment. All but one had psychotic symptoms by month nine (M = 6.3 months, SD = 6.8), and thus prior to one-year neuropsychological assessment. Final diagnoses were: schizophrenia (1), schizoaffective disorder (3), brief psychotic disorder (1), psychosis not otherwise specified (3), major depression with psychotic features (1), and bipolar II (1). Contrary to expectations, we did not find a significantly greater overall NP impairment at one year for CHR who developed psychosis relative to those who did not.

Given the small sample and low power for these analyses, we conducted an exploratory comparison of effect sizes (ES) of the standardized residuals of the two primary domains of interest for the later versus never psychotic subgroups. The overall EF ESs were large but did not differ for those with and without psychotic level symptoms: Cohen's d = −0.83 (95% CI: −1.30 to −0.35) and Cohen's d = −0.91 (95% CI: −1.65 to −0.17) respectively. On the memory domain, however, the one-year discrepancy from predicted scores for those who developed psychotic symptoms (Cohen's d = −1.89, CI = −2.71 to −1.08) was significantly larger than for those who did not (−0.61, CI = −1.08 to −0.14).

3.4. The Role of Baseline IQ in NP Trajectory over Time for the Overall CHR Sample

The general pattern of results remained the same when we covaried baseline WRAT-3 Reading and FSIQ. Finally, we repeated analyses of one-year scores for subgroups relatively well matched on baseline IQ (baseline FSIQ > 100, CHR N = 28, HC N = 29). The overall group difference in standardized residuals at one year remained (ηp2= 0.305, p < 0.002). However, only the EF domain score showed a significant group difference (Mann-Whitney U, p = 0.005).

3.5. The Role of Psychopharmacological and Psychosocial Treatment in NP Performance

As noted earlier, all CHR were participants in a clinical trial and offered psychosocial (low vs. high intensity version of a comprehensive clinical/rehabilitative intervention) and psychopharmacological care. At one year, 87% of the longitudinal sample was taking a psychopharmacological agent: 31 (59%) an antipsychotic medication, 21 (40%) a mood stabilizer or benzodiazapine, and 30 (57%) more than one medication. Being on any psychiatric medication at baseline was significantly associated with lower overall mean NP performance (r = − 0.288, p = 0.037), lower than predicted baseline memory test (r = −0.334, p = 0.015) and lower than predicted vocabulary scores at one year (r = −0.368, p = 0.03). Being on two or more psychiatric medications at baseline was associated with higher than predicted mean standardized residual (r = 0.342, p = 0.012). Of note, being on an antipsychotic medication at baseline was significantly correlated with lower than expected baseline memory test performance and later development of psychotic symptoms (r = 0.280, p = 0.042). Being on a psychiatric medication at one year was associated with lower than predicted one-year EF (r = −0.319, p = 0.020) and being on two or more psychiatric medications at one year was associated with lower than predicted finger tapping speed at one year (r = −0.397, p = 0.003). Overall group and domain findings previously described in 3.2 and 3.3 remained the same when we covaried for number of days on a mood stabilizer and days on antipsychotics. Finally, analyses of NP performance over time did not differ significantly by experimental condition suggesting minimal impact of psychosocial treatment on NP trajectories.

4. Discussion

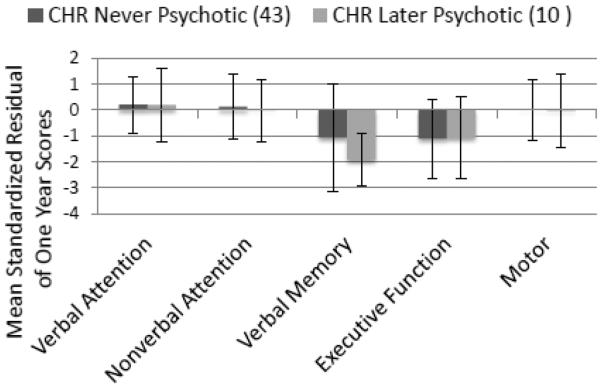

The purpose of this study was to examine the trajectory of neuropsychological development over one year in a CHR sample relative to HC. We predicted progressive relative impairment, particularly on tests of executive, memory and olfactory functions, and most marked in those who developed psychosis. Results revealed an overall failure of the CHR sample as a whole to perform at predicted levels at one year. Based on this battery, progressive NP impairment appeared to be specific to tests most reliant on verbal memory and executive functioning (see Figure 1). While there was a moderate and significant discrepancy in observed and predicted EF domain scores for the whole CHR group (failure of normative performance gains on tests tapping abstract problem-solving, visual-spatial sequencing and set-shifting speed), progressive impairment in verbal memory test performance appeared to be associated with the development of severe and psychotic level symptoms.

Figure 1.

Mean Standardized Residuals of One-Year Scores by CHR Symptom Group. CHR: Clinical High Risk; See Tables 2 or 3 for group descriptions. Residuals of one-year scores were calculated as observed minus predicted scores based on HC distribution; Residuals were standardized so that the M = 0, and SD = 1 for HC. Error bars represent SD. MANOVA overall effect of group: p < 0.001, significant for Verbal Memory and Executive Function domains. Significant (p < 0.01) pairwise comparisons were found between HC and CHR groups for these domains. All CHR performed significantly below predicted levels relative to HC on the executive function domain (p < 0.05). There were no significant differences between CHR groups.

In fact, the one-year (single time point) mean ES for verbal memory test raw scores for the group with psychotic level symptoms relative to HC was large (d = −1.24, see Figure 2 and Online Supplement Table 1), and comparable to the mean ES found in first episode schizophrenia (d = −1.20, Mesholam-Gately, et al., 2009). In contrast, the ES for those who did not develop psychotic level symptoms was moderate (d = −0.42). Interestingly, the later psychotic group demonstrated baseline (again, single time point) impairments in estimated IQ (d = −1.03) comparable to those found in first episode samples (d = −1.01 for WAIS FSIQ, Mesholam-Gately et al., 2009). If reliable, this finding would suggest that much of the IQ impairment identified in schizophrenia samples may already be present prior to the onset of psychotic level symptoms. The lack of progressive impairment in IQ is consistent with prior reports of stable or improved global cognition in the population. Progressive impairment of verbal memory test performance over time, however, may have incremental value in predicting impending psychosis.

Figure 2.

CHR relative to HC Effect Sizes for Raw Test Scores at each Time Point. Effect sizes (ES) were calculated from CHR relative to HC raw test scores at each time point. The mean for tests with child-adult versions was obtained by weighting the separate ES for each child or adult test by the CHR N for that ES. ES were calculated from scaled scores for individuals who transferred from child to adult tests over time. Trail-Making time and WCST Perseverative Errors were log-transformed and made negative to maintain the same direction of effect across tests. See Tables 2 or 3 for group descriptions. See Supplement Tables 1–3 for raw score ES by test, domain, and time point.

To our knowledge, this is the first longitudinal study of olfactory identification during the putative prodrome to psychosis. Whereas olfactory identification is reliably impaired in CHR and may be an important indicator of risk for psychosis, we found no evidence for progressive impairment over time for CHR participants, including those with observed illness progression.

This is one of only a few reports of NP functioning in CHR over time with clinical follow-up of over one year. Given that a modest proportion of individuals with schizophrenia have overall NP functioning considered within the normal range, especially during the prodromal stage (Kremen et al., 2001, 2004; Woodberry et al., 2010), a failure of normative NP development, particularly in immediate verbal memory test performance, may add incremental value for identifying those at highest risk or closest proximity to a psychotic disorder. A failure of normal development within verbal memory and EF domains has implications for abnormal neuromaturation of ventral and dorsolateral prefrontal regions and frontotemporal networks (Stuss, 1992), including medial temporal lobe structures associated with this kind of memory dysfunction (Cirillo and Seidman, 2003). A key question is whether early intervention (e.g., cognitive remediation, neuroprotective agents) might facilitate normal neurodevelopment and associated improvements in NP functioning.

Although the sample was relatively large in the context of published longitudinal analyses of CHR, the primary limitation is one of statistical power. Regression based methods may have benefits over alternative longitudinal analyses in evaluating trajectories influenced by baseline performance and demographics. However, regression based on a HC sample of this size may produce spurious results. Raw score differences at each time point suggest that this is not the case (Figure 2). However, interpretation of performance patterns across tests and test domains is limited by differences in the psychometric properties of the tests, and most particularly each test's sensitivity to change over time. This is especially true for the group that took child tests at baseline and adult tests at one year. Administration of the same or equivalent tests at each time point is recommended for longitudinal analyses.

Another limitation is that the CHR were all participants in a clinical trial with no untreated control group. However, given that we found only a few relatively small significant correlations (rs = 0.28 to 0.37) in the context of close to 150 bivariate comparisons, and no meaningful differences in our primary outcomes when controlling for medication exposure, it is unlikely that medication effects explain the findings. This is consistent with known effects of many of these medications (Goldberg et al., 2007), yet interpretation of these data is complicated by the fact that medications were offered based on the severity of symptoms. Associations may reflect potential medication effects or higher medication rates in those with more severe symptoms. Given the high rate and intensity of treatment exposure in the absence of an untreated control group, we cannot rule out the possibility that differences in symptoms, especially, or NP performance over time may be partially accounted for by treatment effects. Future studies would do well to collect detailed data on medication dosage and compliance to examine estimated exposure and, if possible, to compare trajectories across treated and untreated samples well-matched on demographics, baseline symptoms and neuropsychological functioning.

The use of a psychotic level of symptom rather than a psychotic diagnosis as a measure of outcome, although marking the loss of insight, may not be sufficiently selective. The model we present is offered in the absence of established markers of early illness. Those who progressed to psychosis may indeed have been at higher risk or closer proximity to a psychotic illness; they may also have been less engaged in or receiving less effective treatment, and/or experiencing symptoms related to any number of disorders in which brief or intermittent psychotic symptoms occur.

Ideally, progression of NP impairments would be analyzed by eventual diagnostic outcome in an untreated sample or in a sample in which treatment effects are measured and controlled (McGorry et al., 2008). Given the increasing availability of treatments for CHR, a typically help-seeking population, and the promise that these treatments may at least delay illness progression or moderate negative outcomes (e.g., Morrison et al., 2007), this will be increasingly challenging to achieve. Finally, it is likely that at least part of the observed effects is due to between group differences other than clinical state. Given that special education identification was an exclusion criterion for HC and not CHR, many of the CHR had prior NP testing. As practice effects may diminish over repeat administrations, gains at one year in the HC might be expected to be larger.

In conclusion, this CHR sample demonstrated moderately impaired NP performance and a failure to make normative score gains over time on tasks presumed to measure cognitive flexibility and speeded visuospatial processing. Although not significantly so, progressive impairment in verbal memory test performance appeared to be greatest in those at highest risk or closest proximity to psychosis. As larger CHR samples are available with longitudinal NP data and extended clinical follow-up, it will be important for analyses to consider the potential influence of age (at symptom/illness onset and assessment), premorbid functioning, duration of symptoms, and biological and psychosocial factors on NP development measured more frequently. Sufficiently large numbers of HC individuals with lower cognitive ability may be critical to understanding the relationship of early NP deficits to later developmental abnormalities. Of course, the value of understanding and predicting the development of schizophrenia and related disorders will ultimately be determined by the degree to which this knowledge improves our capacity to alter the course of illness in those at risk.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

This article is based in part on the published dissertation of the first author. Portions of results have been presented at the Schizophrenia International Research Society Conference (2010, April), the Harvard Medical School Department of Psychiatry Research Day (2010, 2011, 2012 March), the International Congress on Schizophrenia Research (2011, April), and the Society for Research in Psychopathology Conference (2011, September). The authors would like to acknowledge staff of the PIER program, in particular Donna Downing, Susan Winslow, Deanna Williams, Dakotah Woitko, and Matthew Bastide, for recruiting and interviewing CHR participants, and preparing the CHR data for analysis. We also thank Betsy Thompson, Joe Canary, Andrew Loignon, Jeremy Cuniff, Coral Sandler, Katie Powers, Jessica Agnew-Blais, Anna Podolsky, and Daniela Joffe for their help with neuropsychological test scoring and data entry, and Matthew Nock, Jill Hooley, and William Milberg for their advising and editing of the dissertation from which this work is drawn. Finally, we thank the participants without whom this research would not have been possible.

Role of funding source Kristen Woodberry was supported by the Sackler Scholar Programme in Psychobiology and a Harvard Graduate Society Dissertation Completion Fellowship. Kristen Woodberry, Anthony Giuliano, and Larry Seidman were also supported by the Commonwealth Research Center of the Massachusetts Department of Mental Health (SCDMH82101008006), NIMH funding to Larry Seidman, PI: (clinical core of NIMH P50 MH080272-02 [McCarley overall PI], NIMH 1 U01 MH081928-01A1), and the Sidney R. Baer Jr. Foundation. Mary Verdi, William Cook, and William McFarlane were supported by funding to the PIER program, William McFarlane, PI: (NIMH RO1MH065367) and the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributors Kristen A. Woodberry contributed to the conceptualization of the study, secured part of its funding, conducted statistical analyses, and wrote the first draft of the manuscript. William R. McFarlane and William L. Cook contributed to the conceptualization and implementation of the study, secured funding for the larger clinical trial from which this study was derived, and contributed to editing of the manuscript, Anthony J. Giuliano and Larry J. Seidman contributed to the conceptualization and implementation of the study, secured funding to support their advisory roles, and provided major editing of the manuscript, Mary B. Verdi contributed to the conceptualization and implementation of the study and the editing of the manuscript, Stephen V. Faraone contributed statistical advice and editing of the manuscript. All authors contributed to and have approved the final manuscript.

Conflict of Interest Dr. McFarlane provides consultation on request to non-profit organizations establishing clinical services similar to the PIER program. The authors report no other potential conflicts of interest.

References

- Ang Y-G, Tan H-Y. Academic deterioration prior to first episode of schizophrenia in young Singaporean males. Psychiatry Res. 2004;121:303–307. doi: 10.1016/s0165-1781(03)00257-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barbato M, Colijn MA, Keefe RSE, Perkins DO, Woods SW, Hawkins KA, et al. The course of cognitive functioning over six months in individuals at clinical high risk for psychosis. Psychiatry Res. 2012 doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2012.10.013. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2012.10.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Becker HE, Nieman DH, Wiltink S, Dingemans PM, van de Fliert JR, Velthorst E, et al. Neurocognitive functioning before and after the first psychotic episode: does psychosis result in cognitive deterioration? Psychol. Med. 2010;40:1599–1606. doi: 10.1017/S0033291710000048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bilder RM, Reiter G, Bates J, Lencz T, Szeszko P, Goldman RS, et al. Cognitive development in schizophrenia: follow-back from the first episode. J. Clin. Exp. Neuropsychol. 2006;28:270–282. doi: 10.1080/13803390500360554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brewer WJ, Wood SJ, McGorry PD, Francey SM, Phillips LJ, Yung AR, et al. Impairment of olfactory identification ability in individuals at ultra-high risk for psychosis who later develop schizophrenia. Am. J. Psychiatry. 2003;160:1790–1794. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.160.10.1790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cannon TD, Cadenhead K, Cornblatt BA, Woods SW, Addington J, Walker E, et al. Prediction of psychosis in youth at high clinical risk. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry. 2008;65:28–37. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2007.3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caspi A, Reichenberg A, Weiser M, Rabinowitz J, Kaplan Z, Knobler H, et al. Cognitive performance in schizophrenia patients assessed before and following the first psychotic episode. Schizophr. Res. 2003;65:87–94. doi: 10.1016/s0920-9964(03)00056-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cirillo M, Seidman LJ. A review of verbal declarative memory function in schizophrenia: From clinical assessment to genetics and brain mechanisms. Neuropsychol. Rev. 2003;13:43–77. doi: 10.1023/a:1023870821631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen M. Children's Memory Scale. Psychological Corporation; San Antonio, TX: 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Cornblatt BA, Keilp JG. Impaired attention, genetics, and pathophysiology of schizophrenia. Schizophr. Bull. 1994;20:31–46. doi: 10.1093/schbul/20.1.31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cosway R, Byrne M, Clafferty R, Hodges A, Grant E, Abukmeil SS, et al. Neuropsychological change in young people at high risk for schizophrenia: results from the first two neuropsychological assessments of the Edinburgh High Risk Study. Psychol. Med. 2000;30:1111–1121. doi: 10.1017/s0033291799002585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delis DC, Kaplan E, Kramer JH. Delis-Kaplan Executive Function System Examiner's System. Psychological Corporation; San Antonio, TX: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Delis DC, Kramer JH, Kaplan E, Ober BA. California Verbal Learning Test - Children's Version. Psychological Corporation; San Antonio, TX: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Delis DC, Kramer JH, Kaplan E, Ober BA. California Verbal Learning Test - Second Edition. Psychological Corporation; San Antonio, TX: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Doty RL, Marcus A, Lee WW. Development of the 12-item cross-cultural smell identification test (CC-SIT) Laryngoscope. 1996;106:353–356. doi: 10.1097/00005537-199603000-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doty RL, Shaman P, Dann M. Development of the UPSIT: a microencapsulated test of olfactory function. Physiological Behavior. 1984;32:489–502. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(84)90269-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, Williams JBW. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders, Clinician Version: Administration booklet. American Psychiatric Publishing, Inc.; Washington, DC: 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Fuller R, Nopoulos P, Arndt S, O'Leary D, Ho BC, Andreasen NC. Longitudinal assessment of premorbid cognitive functioning in patients with schizophrenia through examination of standardized scholastic test performance. Am. J. Psychiatry. 2002;159:1183–1189. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.159.7.1183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fusar-Poli P, Bonoldi I, Yung AR, Borgwardt S, Kempton M, Barale F, Caverzasi E, McGuire P. Predicting psychosis: meta-analysis of transition outcomes in individuals at high clinical risk. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry. 2012;69:220–229. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2011.1472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giuliano AJ, Li H, Mesholam-Gately RI, Sorenson SM, Woodberry KA, Seidman LJ. Neurocognition in the psychosis risk syndrome: A quantitative and qualitative review. Curr. Pharm. Design. 2012;18:399–415. doi: 10.2174/138161212799316019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldberg TE, Goldman RS, Burdick KE, Malhotra AK, Lencz T, Patel RC, et al. Cognitive improvement after treatment with second-generation antipsychotic medications in first-episode schizophrenia: is it a practice effect? Arch. Gen. Psychiatry. 2007;64:1115–1122. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.64.10.1115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gur RE, Calkins ME, Gur RC, Horan WP, Nuechterlein KH, Seidman LJ, et al. The consortium on the genetics of schizophrenia: neurocognitive endophenotypes. Schizophr. Bull. 2007;33:49–68. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbl055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawkins KA, Keefe RC, Christensen BK, Addington J, Woods SW, Callahan J, et al. Neuropsychological course in the prodrome and first episode of psychosis: findings from the PRIME North America Double Blind Treatment Study. Schizophr. Res. 2008;105:1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2008.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heaton RK. Wisconsin Card Sorting Test Manual. Psychological Assessment Resources; Odessa, FL: 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Heaton RK, Temkin N, Dikmen S, Avitable N, Taylor MJ, Marcotte TD, et al. Detecting change: A comparison of three neuropsychological methods, using normal and clinical samples. Arch. Clin. Neuropsychology. 2001;16:75–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jahshan C, Heaton RK, Golshan S, Cadenhead KS. Course of neurocognitive deficits in the prodrome and first episode of schizophrenia. Neuropsychology. 2010;24:109–120. doi: 10.1037/a0016791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keefe RSE, Perkins DO, Gu H, Zipursky RB, Christensen BK, Lieberman JA. A longitudinal study of neurocognitive function in individuals at-risk for psychosis. Schizophr Res. 2006:26–35. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2006.06.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kremen WS, Seidman LJ, Faraone SV, Toomey R, Tsuang MT. Heterogeneity of schizophrenia: a study of individual neuropsychological profiles. Schizophr. Res. 2004;71:307–321. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2004.02.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kremen WS, Seidman LJ, Faraone SV, Tsuang MT. Intelligence quotient and neuropsychological profiles in patients with schizophrenia and in normal volunteers. Biol Psychiatry. 2001;50:453–462. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(01)01099-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lubin A, Gieseking CF, Williams HL. Direct measurement of cognitive deficit in schizophrenia. J. Consult. Psychol. 1962;26:139–143. doi: 10.1037/h0039818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McFarlane WR. Fact: integrating family psychoeducation and assertive community treatment. Admin. Policy in Mental Health. 1997;25:191–198. doi: 10.1023/a:1022291022270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McFarlane WR, Dushay RA, Deakins SM, Stastny P, Lukens EP, Toran J, et al. Employment outcomes in Family-aided Assertive Community Treatment. Am. J. Orthopsychiatry. 2000;70:203–214. doi: 10.1037/h0087819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGlashan TH, Johannessen JO. Early detection and intervention with schizophrenia: rationale. Schizophr. Bull. 1996;22:201–222. doi: 10.1093/schbul/22.2.201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGorry P, Yung AR, Bechdorf A, Amminger P. Back to the future: Predicting and reshaping the course of psychotic disorder. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry. 2008;65:25–27. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2007.9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mesholam-Gately RI, Giuliano AJ, Goff KP, Faraone SV, Seidman LJ. Neurocognition in first-episode schizophrenia: A meta-analytic review. Neuropsychology. 2009;23:315–336. doi: 10.1037/a0014708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller TJ, McGlashan TH, Rosen JL, Somjee L, Markovich PJ, Stein K, et al. Prospective diagnosis of the initial prodrome for schizophrenia based on the Structured Interview for Prodromal Syndromes: preliminary evidence of interrater reliability and predictive validity. Am. J. Psychiatry. 2002;159:863–865. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.159.5.863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller TJ, McGlashan TH, Woods SW, Stein K, Driesen N, Corcoran CM, et al. Symptom assessment in schizophrenic prodromal states. Psychiatry Q. 1999;70:273–287. doi: 10.1023/a:1022034115078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morrison AP, French P, Parker S, Roberts M, Stevens H, Bentall RP, et al. Three-year follow-up of a randomized controlled trial of cognitive therapy for the prevention of psychosis in people at ultra high risk. Schizophr. Bull. 2007;33:682–687. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbl042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nuechterlein KH, Barch DM, Gold JM, Goldberg TE, Green MF, Heaton RK. Identification of separable cognitive factors in schizophrenia. Schizophr. Res. 2004;72:29–39. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2004.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paus T, Keshavan M, Giedd JN. Why do many psychiatric disorders emerge during adolescence? Nat. Rev. Neuroscience. 2008;9:947–957. doi: 10.1038/nrn2513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rabinowitz J, Reichenberg A, Weiser M, Mordechai M, Kaplan Z, Davidson M. Cognitive and behavioral functioning in men with schizophrenia both before and shortly after first admission to hospital: Cross-sectional analysis. Brit. J. Psychiatry. 2000;177:26–32. doi: 10.1192/bjp.177.1.26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reichenberg A, Caspi A, Harrington H, Houts R, Keefe RS, Murray RM, et al. Static and dynamic cognitive deficits in childhood preceding adult schizophrenia: a 30-year study. Am. J. Psychiatry. 2010;167:160–169. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2009.09040574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reitan RM, Wolfson D. The Halstead-Reitan Neuropsychological Test Battery: Theory and clinical applications - Second Edition. Neuropsychology Press; Tucson, AZ: 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Seidman LJ, Buka SL, Goldstein JM, Tsuang MT. Intellectual decline in schizophrenia: Evidence from a prospective birth cohort 28 year follow-up study. J. Clin. Exp. Neuropsychology. 2006;28:225–242. doi: 10.1080/13803390500360471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seidman LJ, Giuliano AJ, Meyer EC, Addington J, Cadenhead KS, Cannon TD, McGlashan TH, Perkins DO, Tsuang MT, Walker EF, Woods SW, Bearden CE, Christensen BK, Hawkins K, Heaton R, Keefe RSE, Heinssen R, Cornblatt B. Neuropsychology of the prodrome to psychosis in the NAPLS consortium: Relationship to family history and conversion to psychosis. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry. 2010;67:578–588. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2010.66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun D, Phillips L, Velakoulis D, Yung A, McGorry PD, Wood SJ, et al. Progressive brain structural changes mapped as psychosis develops in `at risk' individuals. Schiz. Res. 2009;108:85–92. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2008.11.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stuss DT. Biological and psychological development of executive functions. Brain Cogn. 1992;20:8–23. doi: 10.1016/0278-2626(92)90059-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan HS. The onset of schizophrenia. Am. J. Psychiatry. 1927;6:105–134. doi: 10.1176/ajp.151.6.134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tabachnick BG, Fidell LS. Using multivariate statistics. fourth ed Allyn & Bacon; Boston: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi T, Wood SJ, Yung AR, Soulsby B, McGorry PD, Suzuki M, et al. Progressive gray matter reduction of the superior temporal gyrus during transition to psychosis. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry. 2009;66:366–376. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2009.12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Temkin NR, Heaton RK, Grant I, Dikmen SS. Detecting significant change in neuropsychological test performance: A comparison of four models. J. Int. Neuropsychol. Soc. 1999;5:357–369. doi: 10.1017/s1355617799544068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walterfang M, McGuire PK, Yung AR, Phillips LJ, Velakoulis D, Wood SJ, et al. White matter volume changes in people who develop psychosis. Brit. J. Psychiatry. 2008;193:210–215. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.107.043463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wechsler D. Wechsler Memory Scale - Third edition (WMS-III) Harcourt Assessment; San Antonio, TX: 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Wechsler D. Wechsler Abbreviated Scale of Intelligence (WASI) Harcourt Assessment; San Antonio, TX: 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Wechsler D. Administration and scoring manual. Harcourt Assessment; San Antonio, TX: 2003. Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children - Fourth Edition. [Google Scholar]

- Wilkinson GS. WRAT-3: Wide Range Achievement Test Administration Manual. Wide Range; Wilmington, DE: 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Wood SJ, Brewer WJ, Koutsouradis P, Phillips LJ, Francey SM, Proffit TM, et al. Cognitive decline following psychosis onset: Data from the PACE clinic. Brit. J. Psychiatry. 2007;191:s52–s57. doi: 10.1192/bjp.191.51.s52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woodberry KA, Giuliano AJ, Seidman LJ. Premorbid IQ in schizophrenia: A meta-analytic review. Am. J. Psychiatry. 2008;165:579–587. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2008.07081242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woodberry KA, Seidman LJ, Giuliano AJ, Verdi MB, Cook WL, McFarlane WR. Neuropsychological profiles in individuals at clinical high risk for psychosis: relationship to psychosis and intelligence. Schizophr. Res. 2010;123:188–198. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2010.06.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yung AR, McGorry PD. The prodromal phase of first-episode psychosis: Past and current conceptualizations. Schizophr. Bull. 1996;22:353–370. doi: 10.1093/schbul/22.2.353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yung AR, Phillips LJ, Yuen HP, Francey SM, McFarlane CA, Hallgren M, et al. Psychosis prediction: 12-month follow up of a high-risk (“prodromal”) group. Schizophr. Res. 2003;60:21–32. doi: 10.1016/s0920-9964(02)00167-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.