Abstract

C. elegans provides a simplified, in vivo model system in which to study adherens junctions and their role in morphogenesis. The core adherens junction components – HMR-1/E-cadherin, HMP-2/β-catenin and HMP-1/α-catenin – were initially identified through genetic screens for mutants with body axis elongation defects. In early embryos, adherens junction proteins are found at sites of contact between blastomeres, and in epithelial cells adherens junction proteins localize to the multifaceted apical junction (CeAJ) – a single structure that combines the adhesive and barrier functions of vertebrate adherens and tight junctions. The apically localized polarity proteins PAR-3 and PAR-6 mediate formation and maturation of junctions, while the basolaterally localized regulator LET-413/Scribble ensures that junctions remain apically positioned. Adherens junctions promote robust adhesion between epithelial cells and provide mechanical resistance for the physical strains of morphogenesis. However, in contrast to vertebrates, C. elegans adherens junction proteins are not essential for general cell adhesion or for epithelial cell polarization. A combination of conserved and novel proteins localizes to the CeAJ and works together with adherens junctions proteins to mediate adhesion.

Introduction

The relative simplicity of C. elegans, combined with a deep understanding of its development and numerous tools for genetic and cell biological analysis, has made it a rich model system for the study of morphogenesis. Homologues of many vertebrate junction proteins and their regulators are found in C. elegans and are encoded by single genes rather than gene families. Combining genetic tools such as feeding RNAi and chemically induced mutations with live imaging and immunohistochemistry, researchers are uncovering the roles of both conserved and novel morphogenesis genes.

Genes encoding the core adherens junction components – hmr-1/E-cadherin, hmp-2/β-catenin and hmp-1/α-catenin – were identified in genetic screens for embryos with morphological defects (Costa et al., 1998). It was shown that these genes are important for proper morphogenesis of the epidermis (Costa et al., 1998; Raich et al., 1999), whose movements and shape changes are responsible for converting the elliptical embryo into its final worm-like shape (Priess and Hirsh, 1986; Sulston et al., 1983). This chapter focuses on how adherens junction proteins, as well as their regulators and downstream effectors, contribute to cell adhesion and morphogenesis in the C. elegans embryo. We begin the chapter with a description of the core C. elegans adherens junction proteins, highlighting similarities and differences with their mammalian homologues. We next provide an overview of the major morphogenetic events that shape the C. elegans embryo, and describe the contribution of adherens junction proteins to these events. Finally, we describe how junctions assemble and mature, and introduce the regulatory proteins that influence adherens junction placement, stability and activity.

Core components of C. elegans adherens junctions: the cadherin-catenin complex

C. elegans contains single genes encoding the major adherens junctions proteins E-cadherin (hmr-1), β-catenin (hmp-2), and α-catenin (hmp-1). All three genes were originally identified in a mutant screen for embryos with defects in epidermal morphogenesis, and their names reflect the abnormal shapes that mutant embryos form (hmr = Hammerhead, hmp = Humpback) (Costa et al., 1998). One of the more remarkable features of these genes is that putative null mutations have a relatively mild effect on general cell adhesion and apicobasal polarity but severe effects on morphogenesis. Along these lines, while many of the molecular properties of HMR-1/E-cadherin, HMP-2/β-catenin, and HMP-1/α-catenin appear to be similar to those of their vertebrate homologues, the worm proteins have a few distinct features that we highlight below.

HMR-1/E-cadherin

hmr-1 is the sole gene in C. elegans encoding a classic cadherin (Costa et al., 1998), although there are approximately a dozen additional genes that can encode proteins with cadherin repeats and a transmembrane domain (Hill et al., 2001). Through the use of alternative promoters, hmr-1 produces two distinct isoforms that differ in the length and composition of the extracellular domain (Broadbent and Pettitt, 2002). The shorter HMR-1a isoform is more homologous in organization to E-cadherin, while the longer HMR-1b isoform contains additional cadherin repeats and is more similar to N-cadherin. HMR-1a is found in adherens junctions (HMR-1b expression has only been detected in the nervous system), and for simplicity, hereafter we refer to HMR-1a as HMR-1 (Broadbent and Pettitt, 2002; Costa et al., 1998).

The extracellular domain of HMR-1 contains three cadherin repeats, as well as EGF and Laminin G domains that are found in other invertebrate classic cadherins (Costa et al., 1998; Hill et al., 2001). Although it is widely assumed that cadherins participate in homotypic binding, differences with vertebrate classic cadherins in the composition and organization of the extracellular domain make it unclear how, or even whether, HMR-1 extracellular domains interact with one another (Shapiro and Weis, 2009). The cytoplasmic tail has been shown to interact with HMP-2/β-catenin as well as JAC-1, the sole p120-catenin homologue found in worms (Kwiatkowski et al., 2010; Pettitt et al., 2003). HMR-1 expression begins prior to the formation of adherens junctions. In early embryos, maternally supplied HMR-1 localizes uniformly at contacts between each blastomere, which lack cell-cell junctions (Figure 1A) (Costa et al., 1998; Nance and Priess, 2002). During later embryogenesis, when epithelial tissues and organs begin to develop, zygotically expressed HMR-1 is found in epithelial cells and is enriched at adherens junctions (Figure 1B,C) (Costa et al., 1998; Sulston et al., 1983). As described below, HMR-1 contributes to cell adhesion and morphogenesis during both of these stages of development.

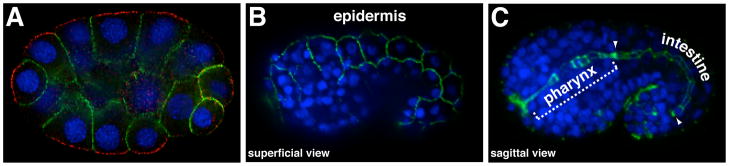

Figure 1. HMR-1/E-cadherin localization in blastomeres and epithelial cells.

All panels show immunostained embryos; DNA is stained blue. (A) HMR-1 (green) in early embryos localizes to sites of contact between blastomeres (a 26-cell stage embryo is shown). Contact-free surfaces are marked with PAR-3 (red). (B–C) After epithelial cells begin to form during mid-embryogenesis, HMR-1 localizes to adherens junctions. (B) Superficial view showing HMR-1 at junctions between epidermal cells. (C) Sagittal view of central region of embryo showing HMR-1 at junctions in pharyngeal and intestinal epithelial cells, which form a tube comprising the digestive tract; region of intestinal cells is bounded by arrowheads.

HMP-2/ β-catenin

Rather uniquely, worms have parceled the functions of their β-catenins into separate signaling and junctional proteins (Korswagen et al., 2000). HMP-2 is the only β-catenin that localizes to blastomere contacts and adherens junctions, and similar to its vertebrate counterpart binds directly to the cytoplasmic tail of HMR-1/E-cadherin as well as to HMP-1/α-catenin (Costa et al., 1998; Kwiatkowski et al., 2010; Pettitt et al., 2003). HMP-2 colocalizes with HMR-1/E-cadherin both at contacts between blastomeres and at adherens junctions in epithelial cells (Costa et al., 1998). Loss of HMR-1/E-cadherin causes HMP-2 to redistribute to the cytoplasm (Costa et al., 1998). Although the function of HMP-2 in epithelial cell adhesion is well established (described below), recent evidence has shown that HMP-2 can contribute to Wnt/Wingless signaling in early embryonic cell fate specification (Putzke and Rothman, 2010; Sumiyoshi et al., 2011).

HMP-1/α-catenin

HMP-1/α-catenin contains a β-catenin-binding domain and an F-actin-binding domain that have been shown to be operative in vitro (Costa et al., 1998; Kwiatkowski et al., 2010). However, unlike vertebrate αE-catenin, recombinant HMP-1 dimers cannot be detected in vitro, and the ability of HMP-1 to bind actin appears to require additional proteins (Kwiatkowski et al., 2010). Nonetheless, both the β-catenin-binding domain and F-actin-binding domain are required for HMP-1 to function in vivo, suggesting that HMP-1 does indeed provide a bridge between HMR-1/E-cadherin and F-actin (Kwiatkowski et al., 2010). HMP-1 colocalizes with HMP-2/β-catenin and HMR-1/E-cadherin, and depends on both proteins for its recruitment to blastomere cell contacts and to epithelial cell adherens junctions (Costa et al., 1998).

Embryonic morphogenesis

The C. elegans embryo undergoes two major morphogenetic rearrangements prior to hatching, and adherens junction proteins contribute to both events. The first morphogenetic event is gastrulation, when cells fated to become endoderm, mesoderm, and germ cells ingress from the surface of the embryo into the interior. The second event is epidermal morphogenesis, when the epidermis wraps around the embryo’s surface then squeezes the embryo to elongate it into a worm-like shape. Forces driving gastrulation and epidermal morphogenesis arise from cell shape changes, and both events require cells to generate nascent cell contacts.

Gastrulation

Gastrulation begins 90 minutes after the first cleavage (26-cell stage) when the daughters of the E endoderm precursor (Ea and Ep) ingress from the surface of the embryo into the interior (Figure 3A) (Sulston et al., 1983). Gastrulation continues over the next few hours with the ingression of mesodermal precursors and primordial germ cells (Nance and Priess, 2002). In order for ingression to commence, Ea and Ep accumulate non-muscle myosin (NMY-2) on their apical, contact-free surfaces, causing this surface to constrict and helping to move these cells into the interior of the embryo (Lee and Goldstein, 2003; Nance and Priess, 2002). At this stage of development, embryonic cells do not show characteristics of epithelial cells such as electron-dense intercellular junctions or asymmetrically positioned organelles, and HMR-1/E-cadherin, HMP-2/β-catenin, and HMP-1/α-catenin localize uniformly to all sites of cell contact (Costa et al., 1998; Grana et al., 2010; Nance and Priess, 2002; Priess and Hirsh, 1986). Removing HMR-1/E-cadherin from early embryos does not globally disrupt cell adhesion or gastrulation – a somewhat surprising finding given that there are no other classic cadherins that could contribute redundantly (Costa et al., 1998; Grana et al., 2010). This paradox was partially resolved when it was shown that SAX-7/L1CAM functions redundantly with HMR-1/E-cadherin in early embryonic cell adhesion and gastrulation (Grana et al., 2010); in embryos lacking both HMR-1/E-cadherin and SAX-7/L1CAM, cell adhesion is compromised and the E daughters fail to ingress (Grana et al., 2010). The adhesive role of HMR-1 appears to be at least partially independent of HMP-2/β-catenin and HMP-1/α-catenin, as sax-7 mutant embryos lacking HMR-1/E-cadherin show more severe cell adhesion defects than do sax-7 mutants lacking either HMP-1/α-catenin or HMP-2/β-catenin. It is not known whether HMR-1/E-cadherin has a specific role in promoting gastrulation (for example, creating tissue-specific differences in adhesion), or whether gastrulation movements themselves simply require robust cell adhesion. Interestingly, although clear adhesion defects arise upon simultaneous loss of HMR-1/E-cadherin and SAX-7/L1CAM, embryonic cells still maintain a basal level of adhesion. Therefore, additional proteins that promote the adhesion of early embryonic cells remain to be identified.

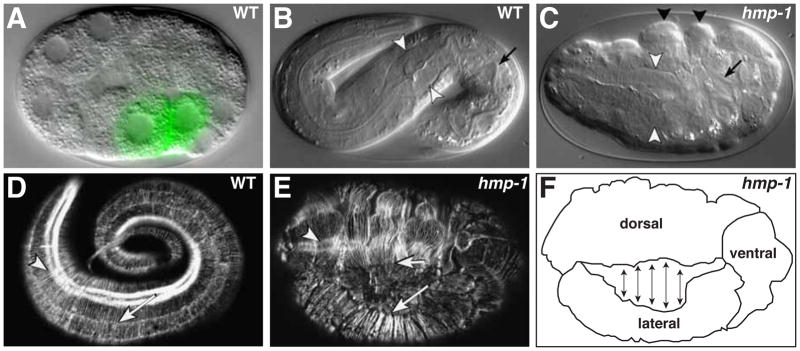

Figure 3. Gastrulation and epidermal morphogenesis.

(A) Early embryo at the onset of gastrulation. The E daughters (labeled green by end-1::GFP transgene) have flattened their apical surfaces and are beginning to ingress into the embryo. (B) Fully elongated wildtype embryo. In B and C, white arrowheads indicate pharyngeal bulb and arrow marks the intestinal lumen. (C) hmp-1 mutant embryo displaying the Humpback (Hmp) phenotype, with characteristic dorsal epidermal bulges (black arrowheads). Note shortened pharynx and intestine (arrow) due to elongation failure. (D) Fully elongated wildtype embryo stained with phalloidin to visualize F-actin. Arrow indicates parallel bundles of circumferential actin filaments, arrowhead indicates actin filaments in underlying muscle tissue. (E) Phalloidin-stained hmp-1 mutant embryo. Circumferential actin bundles between dorsal (short arrow) and lateral (long arrow) epidermal cells have detached. Arrowhead indicates intact underlying muscle actin filaments. (F) Schematic diagram of embryo in E showing points of separation between dorsal and lateral epidermal cells. Images in panels B-E are reprinted from Costa et al., 1998; Panel F was redrawn from a similar panel in Costa et al., 1998.

Epidermal morphogenesis

Adherens junctions do not begin to form until the middle stages of embryogenesis, when most cell divisions have ceased and epithelial tissues begin to form (~300 min after the first cell division) (Leung et al., 1999; Podbilewicz and White, 1994; Priess and Hirsh, 1986; Sulston et al., 1983). Epithelial tissues fall into two major classes: the internal epithelia that comprise the digestive tract (pharynx and intestine) and an external epithelium that surrounds the embryo (epidermis). Cells in both epithelial classes undergo dramatic shape changes as the embryo elongates, and junctions must be created and remodeled to ensure appropriate cell adhesion. Below, we describe the important role of adherens junctions in morphogenesis of the epidermis, whose directed movements and cell shape changes drastically alter the shape of the embryo.

Ventral enclosure

Epidermal cells are born in a monolayer on the dorsal surface during mid-embryogenesis. In order to encase the embryo, epidermal cells undergo a rapid and dramatic migration called ventral enclosure (Figure 2) (Sulston et al., 1983). Ventral enclosure begins soon after epidermal cells differentiate to form an epithelial sheet (Podbilewicz and White, 1994; Sulston et al., 1983; Williams-Masson et al., 1997). Adherens junctions develop at the apicolateral interface of each epidermal cell and connect neighboring epidermal cells together (Costa et al., 1998; Priess and Hirsh, 1986). Just before ventral enclosure, epidermal cells are arranged in bilaterally symmetric rows that are aligned with the anterior-posterior axis: two dorsal rows (which intercalate to form a single row), two lateral rows, and two ventral rows that are born with a free edge that does not contact other epidermal cells and lacks junctions (Priess and Hirsh, 1986; Sulston et al., 1983; Williams-Masson et al., 1997). The two anterior-most pairs of ventral epidermal cells, called leading cells, extend actin-rich filopodia and begin to migrate, pulling the entire epidermal sheet ventrally (Raich et al., 1999; Williams-Masson et al., 1997). Once arriving at the ventral surface, filopodia from contralateral pairs of leading cells meet, and the cells seal together at the ventral midline and form new junctions (Raich et al., 1999; Williams-Masson et al., 1997). Subsequently, many of the remaining ventral epidermal cells (called pocket cells) seal the ventral cleft in a process that has been described as a ‘purse-string’ mechanism, culminating with the formation of new junctions between contralateral cell pairs (Raich et al., 1999; Williams-Masson et al., 1997). In comparison to cultured mammalian cells (Adams et al., 1998), C. elegans epidermal cells form new junctions very rapidly upon contact, suggesting that there is a highly mobile pool of adherens junction proteins that are primed to be delivered to cell contacts (Raich et al., 1999). As in mammalian cells, oriented actin filaments present within filopodia at sites of nascent contact could facilitate the linkage of F-actin to new junctions (Raich et al., 1999; Vasioukhin et al., 2000; Williams-Masson et al., 1997).

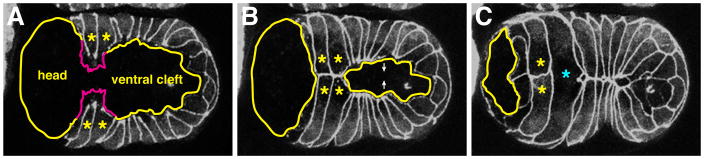

Figure 2. Ventral Enclosure.

(A) Embryo near the start of ventral enclosure expressing DLG-1-GFP to mark junctions, ventral view. Leading cells are marked by asterisks and filopodia are depicted by magenta tracings. The ventral cleft and future head region are indicated. (B) Middle of ventral enclosure. Leading cells have generated nascent contacts with contralateral cells. The ventral cleft is closing as pocket cells begin to come together. (C) End of ventral enclosure. The ventral cleft has closed and the posterior pair of leading cells has fused (cyan asterisk), abolishing the initial contact. Images reprinted from Chisholm and Hardin, 2005.

Upon the completion of ventral enclosure, an epithelial monolayer surrounds the embryo, and junctions join each cell in the monolayer to its neighbors. Many of the epidermal cells ultimately fuse together, abolish cell junctions and form large, multinucleate syncytia (see Figure 2C) (Podbilewicz and White, 1994). Fusion is triggered when adjacent epidermal cells express the fusogenic protein EFF-1 at their surfaces (the related protein AFF-1 mediates fusion of other cell types) (Mohler et al., 2002; Sapir et al., 2007; Shemer et al., 2004). A fusion pore appears in an apical zone at or near the adherens junction, and expands laterally and basally (Mohler et al., 1998). Membrane vesiculation and junction dissolution occurs as the fusion pore expands to encompass the length of the contact between EFF-1-expressing cells. eff-1 mutant worms, which cannot fuse their epidermal cells, are viable but have severe defects in body morphogenesis (Mohler et al., 2002).

Elongation

The second phase of epidermal morphogenesis is elongation. During elongation, the epidermis squeezes the internal cells of the embryo, causing the entire embryo to elongate four-fold and adopt a worm-like shape (Figure 3B). Elongation requires asymmetric changes in epidermal cell shape, which occur in the absence of cell division (Sulston et al., 1983). Each epidermal cell shortens along its circumferential (radial) axis and lengthens along its anterior-posterior (AP) axis (Priess and Hirsh, 1986). These shape changes are promoted by the contraction of parallel bundles of circumferentially oriented apical microfilaments that anchor to adherens junctions at the border of the cell (Figure 3D) (Priess and Hirsh, 1986). The regulation of circumferential microfilament contractions during elongation, which is beyond the focus of this chapter, has been the topic of several recent reviews (Chisholm and Hardin, 2005; Zhang et al., 2010).

In hmr-1, hmp-2, and hmp-1 mutant embryos, circumferential actin bundles detach from adherens junctions, particularly between dorsal and lateral epidermal cells, causing epidermal bulges to form on the dorsal surface (Figure 3C,E,F) (Costa et al., 1998). Mutant embryos also show defects in forming stable junctions between contralateral pairs of epidermal cells that join and seal at the ventral surface during ventral enclosure (Raich et al., 1999), preventing proper cell adhesion and causing the epidermis to contract dorsally. Although adherens junction proteins are not essential for basal levels of cell adhesion, their requirement in promoting robust adhesion becomes apparent when tension within the embryo increases as a result of epidermal morphogenesis (Priess and Hirsh, 1986).

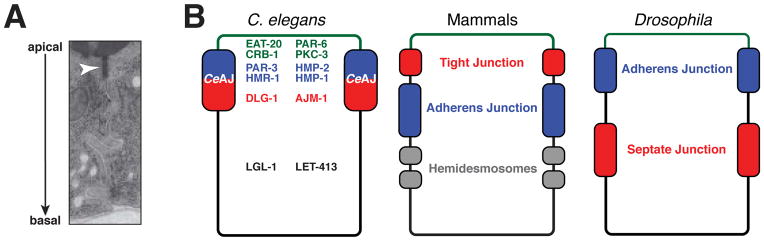

Molecular organization of C. elegans junctions

In contrast to vertebrates and Drosophila, which have functionally and physically distinct adherens and tight/septate junctions, C. elegans epithelial cells contain a single junction that executes both adhesive and barrier functions (Figure 4). The C. elegans apical junction (or CeAJ) is positioned near the apicolateral interface. Despite its organization in electron micrographs as a single, electron-dense structure (Leung et al., 1999; Priess and Hirsh, 1986), the CeAJ contains subdomains that are enriched with different subsets of junction proteins. Adherens junction proteins (HMR-1/E-cadherin, HMP-2/β-catenin, and HMP-1/α-catenin) are found in the apical-most region of the CeAJ (McMahon et al., 2001; Segbert et al., 2004), as are the ZO-1 homologue ZOO-1 and the BCMP1/claudin protein VAB-9 (Lockwood et al., 2008a; Simske et al., 2003). By contrast, the Discs large homolog DLG-1 and its novel binding partner AJM-1 are found in more basal regions of the CeAJ (Bossinger et al., 2001; Firestein and Rongo, 2001; Koppen et al., 2001; McMahon et al., 2001). As we discuss below, junctions assemble in a step-wise fashion that begins with the formation of junction protein puncta, and follows with their apical accumulation and maturation into belt-like junctions that surround each cell. In addition to CeAJs, epidermal cells contain unique junctions called hemidesmosomes, which form a bridge that connects each epidermal cell to overlying cuticle and underlying muscle (Ding et al., 2004; Labouesse, 2006; Zhang and Labouesse, 2010).

Figure 4. The C. elegans apical junction and analogous junctions in mammals and Drosophila.

(A) Transmission electron micrograph of intestinal epithelial cells showing the C. elegans apical junction (CeAJ, arrowhead) as a single electron-dense region. (B) Schematic diagram of epithelial domains and junction structures in C. elegans, mammals and Drosophila. Major polarity and junction proteins and their localization pattern in mature C. elegans epithelia are depicted. Functionally analogous regions in mammals and Drosophila are shown in common colors. Panel A reprinted from Muller and Bossinger, 2003.

PAR proteins and junction assembly

Formation of the CeAJ requires the function of several conserved polarity determinants, including the PAR polarity proteins. PAR proteins were originally identified for their role in polarizing the one-celled C. elegans embryo (zygote) along its anterior-posterior axis (Etemad-Moghadam et al., 1995; Hung and Kemphues, 1999; Kemphues et al., 1988; Tabuse et al., 1998; Watts et al., 1996). PAR-3 (a multi-PDZ domain scaffolding protein), PAR-6 (a PDZ and CRIB-domain protein), and PKC-3 (atypical protein kinase C, aPKC) can physically interact and localize to the anterior of the one-celled embryo, establishing a spatially localized signaling center that polarizes the cell (Nance and Zallen, 2011; St Johnston and Ahringer, 2010). The PAR proteins function together with the Rho GTPase CDC-42 to polarize the one-celled embryo (Chen et al., 1993; Gotta et al., 2001; Kay and Hunter, 2001). Subsequent studies in many species have revealed that homologues of PAR-3, PAR-6, PKC-3/aPKC and CDC-42 are essential for numerous cell polarization events, including polarization of epithelial cells (Goldstein and Macara, 2007; St Johnston and Ahringer, 2010). PAR-3, PAR-6, and PKC-3/aPKC are also found in C. elegans epithelial cells and develop asymmetric localizations during polarization (CDC-42 distribution has not been determined at this stage) (Bossinger et al., 2001; Leung et al., 1999; McMahon et al., 2001). The functions of PAR-3 and PAR-6 in epithelia were determined relatively recently, when genetic tools became available to circumvent their earlier requirement in polarization of the one-cell embryo (Achilleos et al., 2010; Aono et al., 2004; Totong et al., 2007). These studies have revealed that PAR-3 and PAR-6 function sequentially to regulate epithelial polarization and junction maturation, respectively.

PAR-3

The cellular role of PAR-3 in epithelial cells has been examined most extensively in the embryonic intestine. The intestine is a 20-cell tube consisting of nine rings of cells along its length; most rings contain a pair of cells that connect to each other, and to cells in neighboring rings, through apical junctions (Leung et al., 1999). Intestinal cells form during embryogenesis when mesenchymal-like intestinal precursors polarize along their apicobasal axis and assemble junctions. During the very initial stages of polarization, scattered puncta of PAR-3 appear at sites of contact between intestinal precursor cells (Achilleos et al., 2010). PAR-3 puncta also contain adherens junction proteins (HMR-1/E-cadherin, HMP-2/β-catenin, HMP-1/α-catenin) and other PAR proteins (PAR-6 and PKC-3/aPKC) (Figure 5A) (Achilleos et al., 2010). Soon after forming, PAR-3 puncta move asymmetrically along the cell cortex to the future apical surface (Figure 5A,B). In embryos lacking PAR-3, puncta are not detected and junction and polarity proteins mislocalize (Figure 5C) (Achilleos et al., 2010). These findings suggest that PAR-3 polarizes intestinal cells by concentrating junction and polarity proteins into puncta, which then move apically and are enriched at the site of future junction formation. This scaffolding function of PAR-3 appears to be conserved, as the Drosophila PAR-3 homologue Bazooka has been shown to concentrate and trap clusters of E-cadherin at adherens junctions (Mcgill et al., 2009).

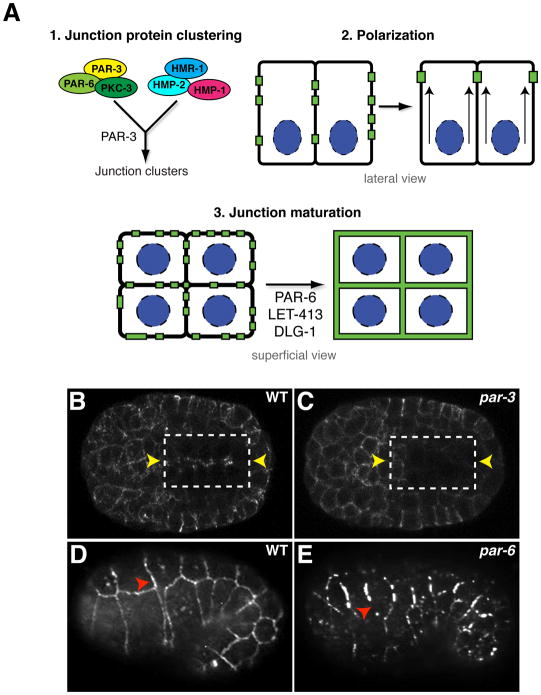

Figure 5. Adherens junction formation.

(A) Junction formation involves distinct steps: (1) PAR-3 is required for clustering adherens junction proteins early during polarization. PAR proteins and adherens junctions proteins are all present in puncta. (2) Epithelial cells polarize and junction clusters are recruited apically to the site of future junction formation. (3) Apically localized puncta mature into belt-like junctions through the function of PAR-6, LET-413, and DLG-1. (B, C) Polarization of junction clusters in WT (B) and embryos lacking both maternal and zygotic PAR-3 (C). HMR-1-GFP is shown. In each panel, the box represents the polarizing intestine. Left and right rows of intestinal cells show mirror symmetry, and the future apical surface between them is indicated by yellow arrowheads. (D,E) Junction maturation in wildtype (D) and embryos lacking both maternal and zygotic PAR-6 (E). Red arrowheads indicate continuous junctions in wildtype (D) and fragmented junctions in par-6 mutants. Junctions are stained with DLG-1, and the epidermis is shown. Panels B-E are reprinted from Achilleos et al., 2010.

It is largely unknown what functions upstream of PAR-3 to ensure its apical localization during polarization. Mutations in the kinesin-like protein ZEN-4 prevent polarization and apical PAR-3 recruitment in one lineage of epithelial cells – the arcade cells (which connect the pharynx to the mouth) (Portereiko et al., 2004). The asymmetric localization of PAR-3 by motor proteins has been documented in several other types of polarized cells, including dynein in Drosophila epithelial cells (Harris and Peifer, 2005) and kinesin in cilia (Fan et al., 2004), raising the possibility that ZEN-4 shuttles PAR-3 to the apical surface. However, zen-4 mutants do not affect polarity in other epithelial lineages, suggesting that such a mechanism of PAR-3 localization would be specialized.

RNAi experiments have shown that PAR-3 is also required for the apical localization of junction proteins and F-actin in spermathecal epithelial cells, which form during late larval stages (Aono et al., 2004). By contrast, embryonic epidermal cells do not require PAR-3 to polarize and assemble apical junctions, even though PAR-3 is expressed in these cells (Achilleos et al., 2010). An important difference between epidermal cells and tube-forming internal epithelia such as the intestine and the spermatheca, where PAR-3 is required for polarity, is the presence of a contact-free surface prior to polarization. An attractive idea is that signals from this contact-free surface provide an alternative, PAR-3-independent pathway for achieving apicobasal polarization.

PAR-6 and PKC-3/aPKC

In contrast to PAR-3, PAR-6 is not required to polarize C. elegans epithelial cells. Rather, PAR-6 promotes the condensation of nascent apical junction protein puncta into mature, belt-like junctions (Figure 5A) (Totong et al., 2007). Initially, PAR-6 colocalizes with PAR-3 and PKC-3/aPKC within the puncta that form as intestinal epithelial cells polarize (Achilleos et al., 2010; Totong et al., 2007). However, in fully differentiated epithelial cells, PAR-6 and PKC-3 remain at the apical surface while PAR-3 segregates to junctions, where it colocalizes with HMR-1/E-cadherin, HMP-2/β-catenin, and HMP-1/α-catenin (Totong et al., 2007). In Drosophila epithelial cells, an analogous relocation of Bazooka/PAR-3 was shown to involve Par-6, aPKC/PKC-3, and the apical transmembrane polarity protein Crumbs (CRB-1 in C. elegans) (Morais-De-Sa et al., 2010). However, while Crumbs proteins are important for both mammalian and Drosophila epithelial polarization (Bulgakova and Knust, 2009), RNAi co-depletion of CRB-1 and EAT-20 (which has homology to Crumbs in the cytoplasmic tail) does not affect epithelial polarization in C. elegans (Bossinger et al., 2001; Shibata et al., 2000).

In embryos lacking PAR-6, junction proteins still localize apicolaterally, but fail to coalesce into mature, belt-like junctions (Figure 5E,F). Consequently, par-6 mutant embryos arrest at the beginning of elongation and develop ruptures within the epidermis (Totong et al., 2007). It is not yet known how PAR-6 controls junction maturation, although studies in other systems suggest that it is likely to do so through PKC-3/aPKC (St Johnston and Ahringer, 2010), with which it interacts physically (Aceto et al., 2006). However, the role of PKC-3 in C. elegans epithelial cells has not yet been determined.

Basolateral polarity regulators and junction maturation and maintenance

Studies of epithelial polarization and cell proliferation in Drosophila have identified a group of basolaterally localized polarity regulators defined by the genes scribble, discs large, and lethal (2) giant larvae (Bilder et al., 2000; Bilder and Perrimon, 2000; Woods et al., 1996). C. elegans contains a single homologue of each of these genes, and let-413/scribble and dlg-1/discs large have been shown to be important for maintaining polarity and forming junctions (Figure 5A) (Bossinger et al., 2001; Firestein and Rongo, 2001; Koppen et al., 2001; Legouis et al., 2000; McMahon et al., 2001). However, neither gene appears to affect cell proliferation in C. elegans, which develops with a largely invariant cell lineage. A C. elegans homolog of lethal (2) giant larvae (lgl-1) has been identified and is expressed in embryonic epithelia, although lgl-1 mutants have no defects in junction formation or epithelial polarity (Beatty et al., 2010; Fichelson et al., 2010).

let-413, which was identified in a chromosomal deficiency screen for genes important for junction morphology (Legouis et al., 2000), encodes a leucine-rich repeat (LRR) and PDZ domain protein (LAP protein) homologous to Drosophila Scribble (Bilder and Perrimon, 2000). Like Scribble (Bilder and Perrimon, 2000) and the human orthologue, SCRIB (Navarro et al., 2005), LET-413 is restricted to basolateral surfaces of epithelial cells (Bilder and Perrimon, 2000; Navarro et al., 2005). During epithelial polarization, loss of LET-413 results in a delayed initial apical compaction of junction proteins, (Koppen et al., 2001; McMahon et al., 2001). After compaction, apical proteins expand basolaterally in let-413 mutant embryos and junctions fail to mature into belt-like junctions (Legouis et al., 2000; McMahon et al., 2001). These defects cause let-413 mutant embryos to arrest during the beginning stages of elongation (Legouis et al., 2000).

dlg-1, a homologue of Drosophila discs large, encodes a MAGUK family scaffolding protein that contains three PDZ domains, one L27 domain, an SH3 domain and a (GuK) guanylate kinase domain (Bossinger et al., 2001; Firestein and Rongo, 2001; Koppen et al., 2001; McMahon et al., 2001). DLG-1 is expressed just after epithelial cells begin to differentiate and localizes to the basal region of the CeAJ. Junctions fail to mature in dlg-1 mutant embryos, though not as severely as in let-413 embryos, and embryos arrest during elongation. Through its L27 domain, DLG-1 is able to multimerize and bind to AJM-1, a coiled-coil domain protein that has no clear orthologues in Drosophila or vertebrates (Koppen et al., 2001; Lockwood et al., 2008b). dlg-1 and ajm-1 mutants have similar phenotypes, although dlg-1 embryos arrest at an earlier stage. The colocalization of DLG-1 and AJM-1, ability of the two proteins to interact, and similarity of phenotypes, all suggest that DLG-1 and AJM-1 function in a common pathway to regulate junction maturation.

dlg-1 and ajm-1 mutants have only minor defects in apicobasal polarity maintenance compared to let-413 mutant embryos, and apical proteins show only a modest expansion into the basolateral domain (Koppen et al., 2001; McMahon et al., 2001). In contrast to Drosophila Discs large, which colocalizes with Scribble and Lethal (2) giant larvae (Bilder et al., 2000; Bilder and Perrimon, 2000), DLG-1/Discs large localizes to a distinct domain immediately basal to adherens junctions, while LET-413/Scribble extends basolaterally. In dlg-1 and ajm-1 mutants, large vacuoles appear in the posterior of the embryo, suggesting these genes may have a role in maintaining a permeability barrier (Firestein and Rongo, 2001; Koppen et al., 2001; McMahon et al., 2001). Consistent with this idea, both dlg-1 and ajm-1 mutants have defects in formation of the apical, electron-dense structure that corresponds to the CeAJ. Since Drosophila Discs large is required for septate junction formation (Bilder et al., 2003), these findings suggest a functional conservation between Discs large orthologues in both species.

The molecular roles of LET-413, DLG-1, and AJM-1 in junction maturation and positioning have not yet been elucidated. However, the fragmented junctions of let-413(RNAi) or dlg-1(RNAi) embryos can be partially rescued by depletion of the inositol 5-phosphatase homolog IPP-5 (Pilipiuk et al., 2009). This family of enzymes regulates levels of inositol triphosphate [IP(3)] (Bui and Sternberg, 2002), which can trigger calcium efflux and signaling within the cell. ipp-5 mutants also rescue sterile phenotypes caused by RNAi depletion of PAR-3 in larval stages (which disrupts junction formation in reproductive tract epithelial cells), suggesting that calcium signaling may be a more general regulator of junction formation (Aono et al., 2004).

Modifiers of adherens junctions

JAC-1/p120ctn

p120-catenins bind to the cytoplasmic tail of classic cadherins and can regulate cadherin clustering and downstream signaling events (Ireton et al., 2002; Thoreson et al., 2000; Yap et al., 1998). C. elegans contains a single gene, jac-1, that encodes a p120-catenin (Pettitt et al., 2003). JAC-1/p120-catenin includes 10 armadillo-like repeats, which in other p120 catenins have been shown to bind to the cadherin juxtamembrane cytoplasmic tail (Yap et al., 1998). JAC-1/p120-catenin also contains four N-terminal fibronectin-like repeats and a PDZ domain, whose functional role is currently unknown (Pettitt et al., 2003).

JAC-1/p120-catenin co-localizes with the cadherin-catenin complex during elongation, depends on the presence of HMR-1/E-cadherin for localization, and binds to the HMR-1/E-cadherin cytoplasmic tail (Pettitt et al., 2003). In contrast to mammalian systems, where p120 catenins are required to stabilize and inhibit endocytosis of classic cadherins (Davis et al., 2003; Ireton et al., 2002), loss of JAC-1/p120-catenin causes only mild defects in HMR-1/E-cadherin localization and does not disrupt epidermal morphogenesis. However, JAC-1/p120-catenin depletion greatly enhances the epidermal morphogenesis defects caused by a weak mutation in hmp-1, suggesting that JAC-1/p120-catenin has a regulatory role in promoting adherens junction function (Pettitt et al., 2003). This enhancement is at least partially caused by defects in the organization of circumferential actin filament bundles, which become irregularly dense and separate from adherens junctions during elongation, similar to null mutants in hmr-1, hmp-1 and hmp-2 mutants (Costa et al., 1998; Pettitt et al., 2003). Although mammalian p120-catenins function by modulating Rho GTPase signaling at junctions (Anastasiadis, 2007), the molecular mechanism of JAC-1/p120-catenin junction regulation has not yet been determined.

F-BAR proteins SRGP-1 and TOCA-1/2

SRGP-1 is the lone C. elegans ortholog of Slit-Robo GTPase activating protein (srGAP). SRGP-1 contains both an F-BAR domain responsible for inducing membrane curvature and a Rho GTPase activation (GAP) domain that can inhibit Rho GTPase signaling (Frost et al., 2009; Guerrier et al., 2009; Zaidel-Bar et al., 2010). Originally, srGAP proteins were found to be downstream effectors of Slit-Robo in axon guidance (Wong et al., 2001). In C. elegans epithelia, SRGP-1 localizes to CeAJs, although it can do so independently of HMR-1 (Zaidel-Bar et al., 2010). Loss of SRGP-1 results in slowed ventral enclosure and enhances the embryonic lethality of a weak hmp-1 mutant. Overexpression of SRGP-1 induces membrane undulation at junctions, suggesting that local regulation of membrane dynamics likely contributes to adherens junction function.

F-BAR proteins of the TOCA family are conserved regulators of CDC-42 and N-WASP-dependent actin polymerization (Ho et al., 2004; Takano et al., 2008). The C. elegans TOCA proteins, TOCA-1 and 2, have been shown to regulate endocytosis in oocytes and localize to junctions in epidermal cells (Giuliani et al., 2009). In Drosophila, TOCA homologue Cip4 is required for proper endocytosis of E-cadherin at junctions (Leibfried et al., 2008). Similarly, toca-1; toca-2 mutants show a significant increase in AJM-1 at junctions in epidermal cells (Giuliani et al., 2009). Loss of TOCA-1 and TOCA-2 causes internal tissues to extrude prior to ventral enclosure (gut on the exterior, or Gex phenotype), suggesting that in mutant embryos, a decrease in junction protein recycling significantly alters adhesiveness between epithelial cells (Giuliani et al., 2009). The Gex phenotype is also seen in C. elegans mutants for branched actin regulators (Bernadskaya et al., 2011; Patel et al., 2008; Soto et al., 2002; Withee et al., 2004), suggesting that a link between actin organization and trafficking of junction proteins is critical for morphogenesis.

Relatives of vertebrate tight junction proteins

VAB-9/BCMP1

Homologues or structural relatives of several vertebrate tight junction proteins localize to CeAJs and help to ensure proper cell adhesion. VAB-9 is a four-pass transmembrane protein, structurally related to the claudin family of tight junction molecules and most similar to human brain cell membrane protein 1 (BCMP1) (Christophe-Hobertus et al., 2001; Simske et al., 2003). VAB-9 colocalizes with adherens junction proteins in the CeAJ, and depends on HMR-1 (but not HMP-2 or HMP-1) for its initial recruitment to junctions (Simske et al., 2003). vab-9 mutant embryos have defects in the organization of circumferential actin filaments within the epidermis and develop dorsal bulges during elongation (Simske et al., 2003), although most mutant embryos complete elongation and hatch into misshapen larvae. However, vab-9 mutations enhance the elongation and adhesion defects of embryos lacking AJM-1 or DLG-1, as well as embryos with reduced levels of adherens junction proteins (Simske et al., 2003). Based on these interactions, it is likely that vab-9 functions downstream of hmr-1 to help mediate proper adhesion between epithelial cells.

ZOO-1/ZO-1

A likely downstream effector of VAB-9 is ZOO-1, the sole C. elegans homologue of vertebrate tight junction proteins in the zonula occludens (ZO) family (Lockwood et al., 2008a). ZOO-1 contains 3 PDZ domains, a Src homology 3 (SH3) domain and a guanylate kinase (GuK) domain, and colocalizes with adherens junction proteins and VAB-9. ZOO-1 depends on both HMR-1 and VAB-9 for its junctional localization, but does not require HMP-2 or HMP-1. Like vab-9 mutants, zoo-1(RNAi) embryos have reduced levels of actin at junctions, elongate slowly, develop bulges within the epidermis, and a small percentage of embryos rupture. Loss of zoo-1 function significantly enhances the lethality of weak mutations in hmp-1 and hmp-2, but does not enhance vab-9 null mutants (Lockwood et al., 2008a), suggesting that it functions downstream of vab-9 to mediate junctional actin organization and adhesion.

MAGI-1

Membrane-associated guanylate kinases (MAGUKs) proteins were originally described in vertebrate tight junctions and function to scaffold protein complexes at the cytoplasmic side of intercellular junctions (Funke et al., 2005). These proteins contain a PDZ domain, SH3 domain and guanylate kinase (GuK) domain. Classical MAGUK family proteins found in C. elegans epithelial cells include DLG-1/Discs large and ZOO-1/ZO-1. MAGI-1, a homologue of the mammalian MAGUK MAGI-1, had previously been shown to function in the C. elegans nervous system. (Stetak et al., 2009). In embryonic epithelia, MAGI-1 localizes apically and, unlike other modifiers of C. elegans adherens junctions, MAGI-1 localization is largely independent of both the adherens junction complex and DLG-1 and AJM-1 (Stetak and Hajnal, 2011). Although localization does not depend on other CeAJ components, magi-1 enhances both dlg-1/ajm-1 and hmr-1/hmp-1/hmp-2 mutants. Additionally, loss of MAGI-1 results in an increased overlap between adherens junction proteins and the DLG-1/AJM-1 domain within the CeAJ (Stetak and Hajnal, 2011). These data indicate that MAGI-1 may have an important regulatory role in segregating functional domains within the CeAJ, and it will be important to learn how MAGI-1 functions.

Future perspectives

The ease of genetic screening in C. elegans has allowed for the identification of many proteins that contribute to the formation, function, and regulation of adherens junctions, providing an outstanding opportunity to learn how adherens junctions function in vivo. However, many important questions remain. For example, a key difference between C. elegans and other systems is that the cadherin-catenin complex plays a rather minor role in cell adhesion. A remaining challenge will be to identify the proteins that function redundantly with adherens junction proteins to promote adhesion between epithelial cells and blastomeres, such as SAX-7 in early embryos, and to learn whether they work together with cadherins and catenins. It will also be important to determine whether genes that affect a similar process, such as let-413 and par-6 in junction maturation, function in a common pathway or have distinct molecular targets. Answering these and related questions will require a detailed understanding of the molecular function of junction and polarity proteins, and learning how they interface with the cadherin-catenin complex.

Table 1.

C. elegans junction proteins

| C. elegans | Type of protein | References |

|---|---|---|

| PAR-6 | PAR-6 protein: PDZ and CRIB domain | (Hung and Kemphues, 1999; Watts et al., 1996) |

| PKC-3 | atypical protein kinase C | (Tabuse et al., 1998) |

| CRB-1 | Crumbs: transmembrane protein | (Bossinger et al., 2001) |

| EAT-20 | Crumbs-like protein: transmembrane protein | (Shibata et al., 2000) |

| PAR-3 | PAR-3 protein: Multi-PDZ domain | (Cheng et al., 1995; Etemad-Moghadam et al., 1995; Kemphues et al., 1988) |

| HMR-1 | E-cadherin | (Costa et al., 1998) |

| HMP-2 | β-catenin | (Costa et al., 1998) |

| HMP-1 | α-catenin | (Costa et al., 1998) |

| DLG-1 | Discs large: MAGUK protein | (Bossinger et al., 2001; Firestein and Rongo, 2001; Koppen et al., 2001; McMahon et al., 2001) |

| AJM-1 | Novel coiled-coil protein | (Koppen et al., 2001) |

| LET-413 | Scribble (LAP protein) | (Legouis et al., 2000) |

| LGL-1 | Lethal (2) giant larvae: WD-40 repeat protein | (Beatty et al., 2010; Fichelson et al., 2010) |

Glossary terms

- Cell fusion

abolishment of cell junctions to create multinucleate syncytia; this process occurs throughout the epidermis and involves the fusogenic proteins EFF-1 and AFF-1

- Invariant lineage

a stereotypical pattern of cell division and differentiation, where cells give rise to a defined set of descendants and cell types

- Gastrulation

morphogenetic process where cells fated to become mesoderm, endoderm or germ cells enter the interior of the embryo

- Ventral enclosure

morphogenetic process where dorsally born epidermal cells migrate ventrolaterally to enclose the C. elegans embryo

- Elongation

morphogenetic process where the coordinated contraction of circumferential actin bundles within the epidermis squeezes the elliptical embryo into a worm-like shape; elongation requires strong cell-cell junctions and communication between the epidermis, overlying cuticle and underlying muscle tissue

- C. elegans apical junction (CeAJ)

a multifaceted structure located apicolaterally in C. elegans epithelia. The CeAJ functions both as an adherens and tight/septate junction

References

- Aceto D, Beers M, Kemphues KJ. Interaction of PAR-6 with CDC-42 is required for maintenance but not establishment of PAR asymmetry in C. elegans. Dev Biol. 2006;299:386–397. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2006.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Achilleos A, Wehman AM, Nance J. PAR-3 mediates the initial clustering and apical localization of junction and polarity proteins during C. elegans intestinal epithelial cell polarization. Development. 2010;137:1833–1842. doi: 10.1242/dev.047647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adams CL, Chen YT, Smith SJ, Nelson WJ. Mechanisms of epithelial cell-cell adhesion and cell compaction revealed by high-resolution tracking of E-cadherin-green fluorescent protein. J Cell Biol. 1998;142:1105–1119. doi: 10.1083/jcb.142.4.1105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anastasiadis PZ. p120-ctn: A nexus for contextual signaling via Rho GTPases. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2007;1773:34–46. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2006.08.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aono S, Legouis R, Hoose WA, Kemphues KJ. PAR-3 is required for epithelial cell polarity in the distal spermatheca of C. elegans. Development. 2004;131:2865–2874. doi: 10.1242/dev.01146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beatty A, Morton D, Kemphues K. The C. elegans homolog of Drosophila Lethal giant larvae functions redundantly with PAR-2 to maintain polarity in the early embryo. Development. 2010;137:3995–4004. doi: 10.1242/dev.056028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernadskaya YY, Patel FB, Hsu HT, Soto MC. Arp2/3 promotes junction formation and maintenance in the Caenorhabditis elegans intestine by regulating membrane association of apical proteins. Mol Biol Cell. 2011;22:2886–2899. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E10-10-0862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bilder D, Li M, Perrimon N. Cooperative regulation of cell polarity and growth by Drosophila tumor suppressors. Science. 2000;289:113–116. doi: 10.1126/science.289.5476.113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bilder D, Perrimon N. Localization of apical epithelial determinants by the basolateral PDZ protein Scribble. Nature. 2000;403:676–680. doi: 10.1038/35001108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bilder D, Schober M, Perrimon N. Integrated activity of PDZ protein complexes regulates epithelial polarity. Nat Cell Biol. 2003;5:53–58. doi: 10.1038/ncb897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bossinger O, Klebes A, Segbert C, Theres C, Knust E. Zonula adherens formation in Caenorhabditis elegans requires dlg-1, the homologue of the Drosophila gene discs large. Dev Biol. 2001;230:29–42. doi: 10.1006/dbio.2000.0113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broadbent ID, Pettitt J. The C. elegans hmr-1 gene can encode a neuronal classic cadherin involved in the regulation of axon fasciculation. Curr Biol. 2002;12:59–63. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(01)00624-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bui YK, Sternberg PW. Caenorhabditis elegans inositol 5-phosphatase homolog negatively regulates inositol 1,4,5-triphosphate signaling in ovulation. Mol Biol Cell. 2002;13:1641–1651. doi: 10.1091/mbc.02-01-0008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bulgakova NA, Knust E. The Crumbs complex: from epithelial-cell polarity to retinal degeneration. J Cell Sci. 2009;122:2587–2596. doi: 10.1242/jcs.023648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen W, Lim HH, Lim L. The CDC42 homologue from Caenorhabditis elegans. Complementation of yeast mutation. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:13280–13285. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng NN, Kirby CM, Kemphues KJ. Control of cleavage spindle orientation in Caenorhabditis elegans: the role of the genes par-2 and par-3. Genetics. 1995;139:549–559. doi: 10.1093/genetics/139.2.549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chisholm AD, Hardin J. WormBook, editor. The C elegans Research Community. Wormbook; 2005. Epidermal morphogenesis. http://www.wormbook.org. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christophe-Hobertus C, Szpirer C, Guyon R, Christophe D. Identification of the gene encoding Brain Cell Membrane Protein 1 (BCMP1), a putative four-transmembrane protein distantly related to the Peripheral Myelin Protein 22 / Epithelial Membrane Proteins and the Claudins. BMC Genomics. 2001;2:3. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-2-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costa M, Raich W, Agbunag C, Leung B, Hardin J, Priess JR. A putative catenin-cadherin system mediates morphogenesis of the Caenorhabditis elegans embryo. J Cell Biol. 1998;141:297–308. doi: 10.1083/jcb.141.1.297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis MA, Ireton RC, Reynolds AB. A core function for p120-catenin in cadherin turnover. J Cell Biol. 2003;163:525–534. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200307111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding M, Woo WM, Chisholm AD. The cytoskeleton and epidermal morphogenesis in C. elegans. Exp Cell Res. 2004;301:84–90. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2004.08.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Etemad-Moghadam B, Guo S, Kemphues KJ. Asymmetrically distributed PAR-3 protein contributes to cell polarity and spindle alignment in early C. elegans embryos. Cell. 1995;83:743–752. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90187-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan S, Hurd TW, Liu CJ, Straight SW, Weimbs T, Hurd EA, Domino SE, Margolis B. Polarity proteins control ciliogenesis via kinesin motor interactions. Curr Biol. 2004;14:1451–1461. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2004.08.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fichelson P, Jagut M, Lepanse S, Lepesant JA, Huynh JR. lethal giant larvae is required with the par genes for the early polarization of the Drosophila oocyte. Development. 2010;137:815–824. doi: 10.1242/dev.045013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Firestein BL, Rongo C. DLG-1 is a MAGUK similar to SAP97 and is required for adherens junction formation. Mol Biol Cell. 2001;12:3465–3475. doi: 10.1091/mbc.12.11.3465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frost A, V, Unger M, De Camilli P. The BAR domain superfamily: membrane-molding macromolecules. Cell. 2009;137:191–196. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.04.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Funke L, Dakoji S, Bredt DS. Membrane-associated guanylate kinases regulate adhesion and plasticity at cell junctions. Annu Rev Biochem. 2005;74:219–245. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.74.082803.133339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giuliani C, Troglio F, Bai Z, Patel FB, Zucconi A, Malabarba MG, Disanza A, Stradal TB, Cassata G, Confalonieri S, Hardin JD, Soto MC, Grant BD, Scita G. Requirements for F-BAR Proteins TOCA-1 and TOCA-2 in Actin Dynamics and Membrane Trafficking during Caenorhabditis elegans Oocyte Growth and Embryonic Epidermal Morphogenesis. PLos Genetics. 2009;5:e1000675. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein B, Macara IG. The PAR proteins: fundamental players in animal cell polarization. Dev Cell. 2007;13:609–622. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2007.10.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gotta M, Abraham MC, Ahringer J. CDC-42 controls early cell polarity and spindle orientation in C. elegans. Curr Biol. 2001;11:482–488. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(01)00142-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grana TM, Cox EA, Lynch AM, Hardin J. SAX-7/L1CAM and HMR-1/cadherin function redundantly in blastomere compaction and non-muscle myosin accumulation during Caenorhabditis elegans gastrulation. Dev Biol. 2010;344:731–744. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2010.05.507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guerrier S, Coutinho-Budd J, Sassa T, Gresset A, Jordan NV, Chen K, Jin W-L, Frost A, Polleux F. The F-BAR Domain of srGAP2 Induces Membrane Protrusions Required for Neuronal Migration and Morphogenesis. Cell. 2009;138:990–1004. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.06.047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris TJ, Peifer M. The positioning and segregation of apical cues during epithelial polarity establishment in Drosophila. J Cell Biol. 2005;170:813–823. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200505127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill E, I, Broadbent D, Chothia C, Pettitt J. Cadherin superfamily proteins in Caenorhabditis elegans and Drosophila melanogaster. J Mol Biol. 2001;305:1011–1024. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2000.4361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ho HY, Rohatgi R, Lebensohn AM, Le M, Li J, Gygi SP, Kirschner MW. Toca-1 mediates Cdc42-dependent actin nucleation by activating the N-WASP-WIP complex. Cell. 2004;118:203–216. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.06.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hung TJ, Kemphues KJ. PAR-6 is a conserved PDZ domain-containing protein that colocalizes with PAR-3 in Caenorhabditis elegans embryos. Development. 1999;126:127–135. doi: 10.1242/dev.126.1.127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ireton RC, Davis MA, van Hengel J, Mariner DJ, Barnes K, Thoreson MA, Anastasiadis PZ, Matrisian L, Bundy LM, Sealy L, Gilbert B, van Roy F, Reynolds AB. A novel role for p120 catenin in E-cadherin function. J Cell Biol. 2002;159:465–476. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200205115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kay AJ, Hunter CP. CDC-42 regulates PAR protein localization and function to control cellular and embryonic polarity in C. elegans. Curr Biol. 2001;11:474–481. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(01)00141-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kemphues KJ, Priess JR, Morton DG, Cheng NS. Identification of genes required for cytoplasmic localization in early C. elegans embryos. Cell. 1988;52:311–320. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(88)80024-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koppen M, Simske JS, Sims PA, Firestein BL, Hall DH, Radice AD, Rongo C, Hardin JD. Cooperative regulation of AJM-1 controls junctional integrity in Caenorhabditis elegans epithelia. Nat Cell Biol. 2001;3:983–991. doi: 10.1038/ncb1101-983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korswagen HC, Herman MA, Clevers HC. Distinct β-catenins mediate adhesion and signalling functions in C. elegans. Nature. 2000;406:527–532. doi: 10.1038/35020099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwiatkowski AV, Maiden SL, Pokutta S, Choi HJ, Benjamin JM, Lynch AM, Nelson WJ, Weis WI, Hardin J. In vitro and in vivo reconstitution of the cadherin-catenin-actin complex from Caenorhabditis elegans. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:14591–14596. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1007349107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Labouesse M. WormBook, editor. The C elegans Research Community. Wormbook; 2006. Epithelial junctions and attachments. www.wormbook.org. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee JY, Goldstein B. Mechanisms of cell positioning during C. elegans gastrulation. Development. 2003;130:307–320. doi: 10.1242/dev.00211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Legouis R, Gansmuller A, Sookhareea S, Bosher JM, Baillie DL, Labouesse M. LET-413 is a basolateral protein required for the assembly of adherens junctions in Caenorhabditis elegans. Nat Cell Biol. 2000;2:415–422. doi: 10.1038/35017046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leibfried A, Fricke R, Morgan MJ, Bogdan S, Bellaiche Y. Drosophila Cip4 and WASp Define a Branch of the Cdc42-Par6-aPKC Pathway Regulating E-Cadherin Endocytosis. Curr Biol. 2008;18:1639–1648. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2008.09.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leung B, Hermann GJ, Priess JR. Organogenesis of the Caenorhabditis elegans intestine. Dev Biol. 1999;216:114–134. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1999.9471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lockwood C, Zaidel-Bar R, Hardin J. The C. elegans zonula occludens ortholog cooperates with the cadherin complex to recruit actin during morphogenesis. Curr Biol. 2008a;18:1333–1337. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2008.07.086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lockwood CA, Lynch AM, Hardin J. Dynamic analysis identifies novel roles for DLG-1 subdomains in AJM-1 recruitment and LET-413-dependent apical focusing. J Cell Sci. 2008b;121:1477–1487. doi: 10.1242/jcs.017137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mcgill MA, Mckinley RFA, Harris TJC. Independent cadherin-catenin and Bazooka clusters interact to assemble adherens junctions. J Cell Biol. 2009;185:787–796. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200812146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McMahon L, Legouis R, Vonesch JL, Labouesse M. Assembly of C. elegans apical junctions involves positioning and compaction by LET-413 and protein aggregation by the MAGUK protein DLG-1. J Cell Sci. 2001;114:2265–2277. doi: 10.1242/jcs.114.12.2265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohler WA, Shemer G, del Campo JJ, Valansi C, Opoku-Serebuoh E, Scranton V, Assaf N, White JG, Podbilewicz B. The type I membrane protein EFF-1 is essential for developmental cell fusion. Dev Cell. 2002;2:355–362. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(02)00129-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohler WA, Simske JS, Williams-Masson EM, Hardin JD, White JG. Dynamics and ultrastructure of developmental cell fusions in the Caenorhabditis elegans hypodermis. Curr Biol. 1998;8:1087–1090. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(98)70447-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morais-De-Sa E, Mirouse V, Johnston DS. aPKC Phosphorylation of Bazooka Defines the Apical/Lateral Border in Drosophila Epithelial Cells. Cell. 2010;141:509–523. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.02.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Müller HA, Bossinger O. Molecular networks controlling epithelial cell polarity in development. Mech Dev. 2003;120:1231–1256. doi: 10.1016/j.mod.2003.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nance J, Priess JR. Cell polarity and gastrulation in C. elegans. Development. 2002;129:387–397. doi: 10.1242/dev.129.2.387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nance J, Zallen JA. Elaborating polarity: PAR proteins and the cytoskeleton. Development. 2011;138:799–809. doi: 10.1242/dev.053538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Navarro C, Nola S, Audebert S, Santoni MJ, Arsanto JP, Ginestier C, Marchetto S, Jacquemier J, Isnardon D, Le Bivic A, Birnbaum D, Borg JP. Junctional recruitment of mammalian Scribble relies on E-cadherin engagement. Oncogene. 2005;24:4330–4339. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1208632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel FB, Bernadskaya YY, Chen E, Jobanputra A, Pooladi Z, Freeman KL, Gally C, Mohler WA, Soto MC. The WAVE/SCAR complex promotes polarized cell movements and actin enrichment in epithelia during C. elegans embryogenesis. Dev Biol. 2008;324:297–309. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2008.09.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pettitt J, Cox EA, Broadbent ID, Flett A, Hardin J. The Caenorhabditis elegans p120 catenin homologue, JAC-1, modulates cadherin-catenin function during epidermal morphogenesis. J Cell Biol. 2003;162:15–22. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200212136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pilipiuk J, Lefebvre C, Wiesenfahrt T, Legouis R, Bossinger O. Increased IP3/Ca2+ signaling compensates depletion of LET-413/DLG-1 in C. elegans epithelial junction assembly. Dev Biol. 2009;327:34–47. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2008.11.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Podbilewicz B, White JG. Cell fusions in the developing epithelia of C. elegans. Dev Biol. 1994;161:408–424. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1994.1041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Portereiko MF, Saam J, Mango SE. ZEN-4/MKLP1 is required to polarize the foregut epithelium. Curr Biol. 2004;14:932–941. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2004.05.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Priess JR, Hirsh DI. Caenorhabditis elegans morphogenesis: the role of the cytoskeleton in elongation of the embryo. Dev Biol. 1986;117:156–173. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(86)90358-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Putzke AP, Rothman JH. Repression of Wnt signaling by a Fer-type nonreceptor tyrosine kinase. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:16154–16159. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1006600107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raich WB, Agbunag C, Hardin J. Rapid epithelial-sheet sealing in the Caenorhabditis elegans embryo requires cadherin-dependent filopodial priming. Curr Biol. 1999;9:1139–1146. doi: 10.1016/S0960-9822(00)80015-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sapir A, Choi J, Leikina E, Avinoam O, Valansi C, Chernomordik LV, Newman AP, Podbilewicz B. AFF-1, a FOS-1-regulated fusogen, mediates fusion of the anchor cell in C. elegans. Dev Cell. 2007;12:683–698. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2007.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Segbert C, Johnson K, Theres C, van Fürden D, Bossinger O. Molecular and functional analysis of apical junction formation in the gut epithelium of Caenorhabditis elegans. Dev Biol. 2004;266:17–26. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2003.10.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shapiro L, Weis WI. Structure and biochemistry of cadherins and catenins. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2009;1:a003053. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a003053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shemer G, Suissa M, Kolotuev I, Nguyen KC, Hall DH, Podbilewicz B. EFF-1 is sufficient to initiate and execute tissue-specific cell fusion in C. elegans. Curr Biol. 2004;14:1587–1591. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2004.07.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shibata Y, Fujii T, Dent JA, Fujisawa H, Takagi S. EAT-20, a novel transmembrane protein with EGF motifs, is required for efficient feeding in Caenorhabditis elegans. Genetics. 2000;154:635–646. doi: 10.1093/genetics/154.2.635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simske JS, Köppen M, Sims P, Hodgkin J, Yonkof A, Hardin J. The cell junction protein VAB-9 regulates adhesion and epidermal morphology in C. elegans. Nat Cell Biol. 2003;5:619–625. doi: 10.1038/ncb1002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soto MC, Qadota H, Kasuya K, Inoue M, Tsuboi D, Mello CC, Kaibuchi K. The GEX-2 and GEX-3 proteins are required for tissue morphogenesis and cell migrations in C. elegans. Genes Dev. 2002;16:620–632. doi: 10.1101/gad.955702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- St Johnston D, Ahringer J. Cell polarity in eggs and epithelia: parallels and diversity. Cell. 2010;141:757–774. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stetak A, Hajnal A. The C. elegans MAGI-1 protein is a novel component of cell junctions that is required for junctional compartmentalization. Dev Biol. 2011;350:24–31. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2010.10.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stetak A, Horndli F, Maricq AV, van den Heuvel S, Hajnal A. Neuron-specific regulation of associative learning and memory by MAGI-1 in C. elegans. PLoS One. 2009;4:e6019. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0006019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sulston JE, Schierenberg E, White JG, Thomson JN. The embryonic cell lineage of the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans. Dev Biol. 1983;100:64–119. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(83)90201-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sumiyoshi E, Takahashi S, Obata H, Sugimoto A, Kohara Y. The β-catenin HMP-2 functions downstream of Src in parallel with the Wnt pathway in early embryogenesis of C. elegans. Dev Biol. 2011;355:302–312. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2011.04.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tabuse Y, Izumi Y, Piano F, Kemphues KJ, Miwa J, Ohno S. Atypical protein kinase C cooperates with PAR-3 to establish embryonic polarity in Caenorhabditis elegans. Development. 1998;125:3607–3614. doi: 10.1242/dev.125.18.3607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takano K, Toyooka K, Suetsugu S. EFC/F-BAR proteins and the N-WASP-WIP complex induce membrane curvature-dependent actin polymerization. Embo J. 2008;27:2817–2828. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2008.216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thoreson MA, Anastasiadis PZ, Daniel JM, Ireton RC, Wheelock MJ, Johnson KR, Hummingbird DK, Reynolds AB. Selective uncoupling of p120(ctn) from E-cadherin disrupts strong adhesion. J Cell Biol. 2000;148:189–202. doi: 10.1083/jcb.148.1.189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Totong R, Achilleos A, Nance J. PAR-6 is required for junction formation but not apicobasal polarization in C. elegans embryonic epithelial cells. Development. 2007;134:1259–1268. doi: 10.1242/dev.02833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vasioukhin V, Bauer C, Yin M, Fuchs E. Directed actin polymerization is the driving force for epithelial cell-cell adhesion. Cell. 2000;100:209–219. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81559-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watts JL, Etemad-Moghadam B, Guo S, Boyd L, Draper BW, Mello CC, Priess JR, Kemphues KJ. par-6, a gene involved in the establishment of asymmetry in early C. elegans embryos, mediates the asymmetric localization of PAR-3. Development. 1996;122:3133–3140. doi: 10.1242/dev.122.10.3133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams-Masson EM, Malik AN, Hardin J. An actin-mediated two-step mechanism is required for ventral enclosure of the C. elegans hypodermis. Development. 1997;124:2889–2901. doi: 10.1242/dev.124.15.2889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Withee J, Galligan B, Hawkins N, Garriga G. Caenorhabditis elegans WASP and Ena/VASP proteins play compensatory roles in morphogenesis and neuronal cell migration. Genetics. 2004;167:1165–1176. doi: 10.1534/genetics.103.025676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong K, Ren XR, Huang YZ, Xie Y, Liu G, Saito H, Tang H, Wen L, Brady-Kalnay SM, Mei L, Wu JY, Xiong WC, Rao Y. Signal transduction in neuronal migration: roles of GTPase activating proteins and the small GTPase Cdc42 in the Slit-Robo pathway. Cell. 2001;107:209–221. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00530-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woods DF, Hough C, Peel D, Callaini G, Bryant PJ. Dlg protein is required for junction structure, cell polarity, and proliferation control in Drosophila epithelia. J Cell Biol. 1996;134:1469–1482. doi: 10.1083/jcb.134.6.1469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yap AS, Niessen CM, Gumbiner BM. The juxtamembrane region of the cadherin cytoplasmic tail supports lateral clustering, adhesive strengthening, and interaction with p120ctn. J Cell Biol. 1998;141:779–789. doi: 10.1083/jcb.141.3.779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zaidel-Bar R, Joyce MJ, Lynch AM, Witte K, Audhya A, Hardin J. The F-BAR domain of SRGP-1 facilitates cell-cell adhesion during C. elegans morphogenesis. J Cell Biol. 2010;191:761–769. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201005082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang H, Gally C, Labouesse M. Tissue morphogenesis: how multiple cells cooperate to generate a tissue. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2010;22:575–582. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2010.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang H, Labouesse M. The making of hemidesmosome structures in vivo. Dev Dyn. 2010;239:1465–1476. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.22255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]