Abstract

Malaria is a potentially fatal disease caused by Plasmodium parasites and poses a major medical risk in large parts of the world. The development of new, affordable antimalarial drugs is of vital importance as there are increasing reports of resistance to the currently available therapeutics. In addition, most of the current drugs used for chemoprophylaxis merely act on parasites already replicating in the blood. At this point, a patient might already be suffering from the symptoms associated with the disease and could additionally be infectious to an Anopheles mosquito. These insects act as a vector, subsequently spreading the disease to other humans. In order to cure not only malaria but prevent transmission as well, a drug must target both the blood- and pre-erythrocytic liver stages of the parasite. P. falciparum (Pf) enoyl acyl carrier protein (ACP) reductase (ENR) is a key enzyme of plasmodial type II fatty acid biosynthesis (FAS II). It has been shown to be essential for liver-stage development of Plasmodium berghei and is therefore qualified as a target for true causal chemoprophylaxis. Using virtual screening based on two crystal structures of PfENR, we identified a structurally novel class of FAS inhibitors. Subsequent chemical optimization yielded two compounds that are effective against multiple stages of the malaria parasite. These two most promising derivatives were found to inhibit blood-stage parasite growth with IC50 values of 1.7 and 3.0 µm and lead to a more prominent developmental attenuation of liver-stage parasites than the gold-standard drug, primaquine.

Keywords: antimalarial agents, fatty acid biosynthesis, molecular modeling, multistage inhibitors, Plasmodium falciparum, virtual screening

Introduction

Over two billion people in approximately 100 countries are at risk of contracting malaria, a disease that often turns out to be fatal for young children.[1] Their chances to survive depend not least on the development of new, affordable drugs, as increasing resistance against the currently used therapeutic agents is observed. Malaria is caused by the protozoan Plasmodium and is transmitted by the Anopheles mosquito. When this insect feeds on an infected individual, it can ingest Plasmodium gametocytes along with the blood meal. These represent the only stages in the life cycle of Plasmodium that are infectious to the mosquito. Inside the mosquito host, Plasmodium sporozoites are subsequently formed. These motile stages travel to the salivary gland of the mosquito and can be injected along with its saliva while feeding on another human host. There, Plasmodium sporozoites migrate actively into the circulation and finally end up in the liver, where they infect hepatocytes. It takes around seven to ten days for P. falciparum sporozoites to subsequently develop into several thousand first-generation merozoites.[2] As a consequence, the liver stage is characterized by huge metabolic demands. Merozoites are then released into the blood to begin their pathological blood-stage development by infecting erythrocytes. Subsequently, the patient begins to suffer from symptoms like fever, pain and nausea.[3] Given the life cycle, antimalarial drug development should be directed towards compounds that are able to kill the silent liver stages. In addition, these desired compounds must also be able to kill blood stage parasites.

Replicating in the liver as well as in erythrocytes, Plasmodium parasites require vast amounts of fatty acids (FA). Metabolism in these two stages of the life cycle, however, is fundamentally different.[4, 5] In the blood stage, the vast majority of the FAs are acquired from the host.[6] In earlier studies, it was assumed that Plasmodium acquires FAs merely by scavenging, however, Plasmodium was recently found to be capable of type II fatty acid biosynthesis (FAS II). FAS enzymes are targeted to the apicoplast, a relict, non-photosynthetic plastid of algal origin. In most plants as well as in bacteria, discrete enzymes catalyze the distinct steps in plasmodial FAS II (Scheme 1). In contrast to this, in mammals, FAS is performed by a multi-enzyme complex, handling all four of the enzymatic steps of the elongation of fatty acids (FAS I). Although there is no difference in mechanism in the elongation of fatty acid chains, this fundamentally distinct setup of enzymes makes FAS I insensitive to a number of FAS II inhibitors and qualifies fatty acid biosynthesis in Plasmodium as a potential drug target.

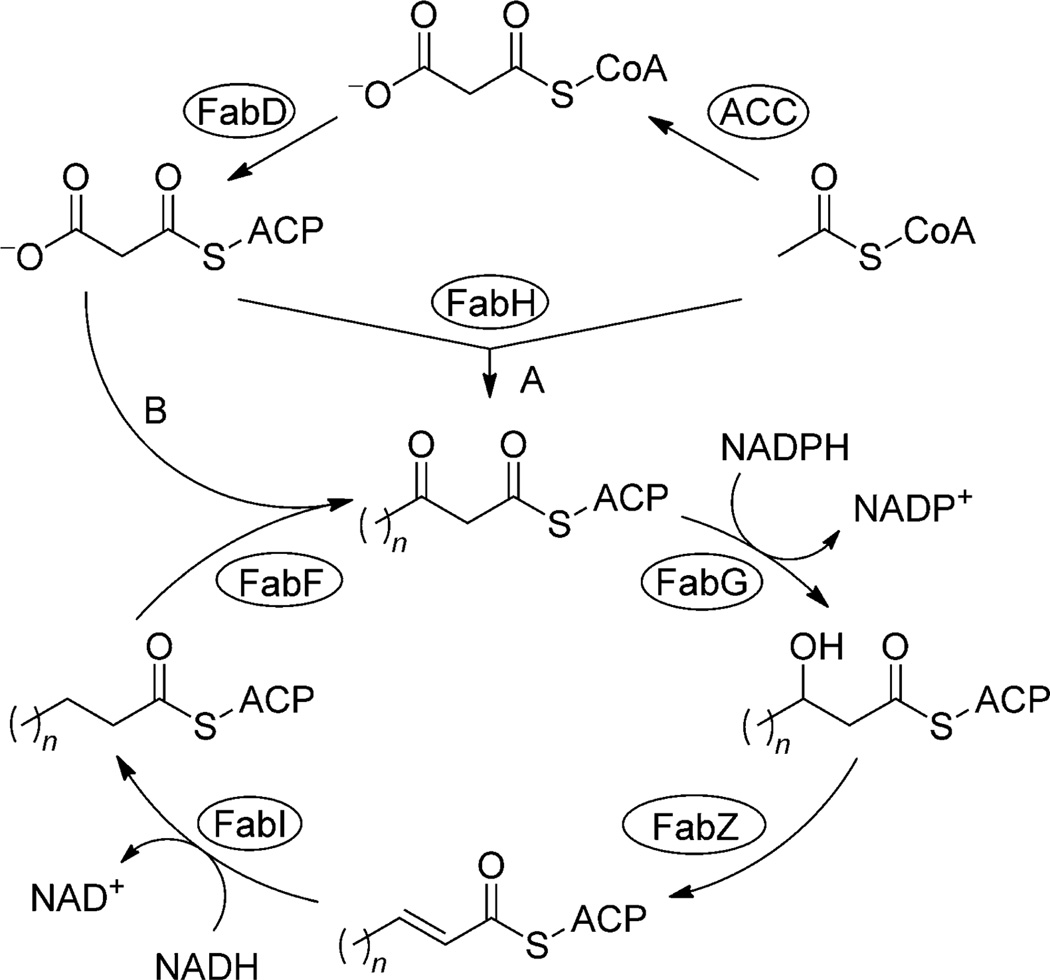

Scheme 1.

Type II fatty acid biosynthesis. The most vital precursor to fatty acids in Plasmodium is acetyl-CoA, which is provided by acetyl-CoA synthase or pyruvate dehydrogenase. Fatty acid biosynthesis begins with the carboxylation of acetyl-CoA by acetyl-CoA carboxylase (ACC). The resulting product, malonyl-CoA, is then converted to malonyl-acyl carrier protein (ACP) by malonyl-CoA–ACP transacylase (FabD). ACP is a small, acidic protein that binds acyl intermediates as thioesters during fatty acid synthesis and carries them between enzymes. The first reaction is a condensation catalyzed by β-ketoacyl-ACP synthase III (FabH), which uses acetyl-CoA and malonyl-ACP as substrates. Next is a NADPH-dependent reduction of β-ketoacyl-ACP to β-hydroxyacyl-ACP catalyzed by β-ketoacyl-ACP reductase (FabG). β-Hydroxyacyl-ACP dehydratase (FabZ) then forms trans-2-enoyl-ACP by removing a water molecule from the acyl chain. trans-Enoyl-ACP is finally NADH-dependently reduced by enoyl-ACP reductase (FabI), which presents the rate-limiting step in fatty acid chain elongation. Another molecule of malonyl-ACP can subsequently be used to add two more carbon atoms to the nascent acyl chain by β-ketoacyl-ACP synthase II. This cycle continues with the length of the acyl chain increasing by two carbons until the desired fatty acid is produced.

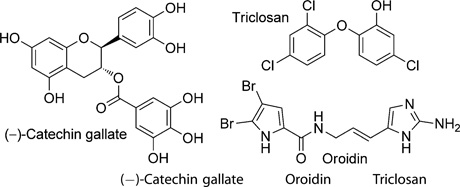

Triclosan is an antibacterial and antifungal agent commonly used in a large variety of consumer products such as toothpastes and pillowcases. In 1998, it was shown to be an Escherichia coli FAS inhibitor and to specifically inhibit E. coli enoyl acyl carrier protein (ACP) reductase (ENR).[7] The contemporary discovery of the plastidial origin of the apicoplast and its suggestion as a drug target[8] prompted efforts to assay triclosan as an antiplasmodial agent. Triclosan proved to inhibit P. falciparum (Pf) ENR with a Ki value of 0.4 nm[9] and, in addition, to prevent the growth of blood-stage P. falciparum at a low micromolar concentration.[10,11] Subsequent work by Yu et al.[4] showed that FAS II is essential in liver-stage parasites but not in blood-stage parasites. Nevertheless, triclosan and other inhibitors of plasmodial FAS, and PfENR inhibitors in particular, frequently do show an inhibitory effect on blood-stage cultured parasites as well (see Table 1). Hence, it is tempting to speculate on a common off-target.[12, 13] The genome of Plasmodium appears to encode for three different fatty acid elongases (ELOs). In contrast to FAS type I and II, ELO pathways use CoA rather than ACP as an acyl carrier. Importantly, ELO pathways contain an enoyl-CoA reductase (EnCR) that catalyzes a similar reaction to that of PfENR. Although ELO pathways typically elongate long-chain FAs such as palmitate,[14] trypanosomes were recently shown to synthesize most of their FAs from butyryl-CoA precursors.[15] So, we speculated that enzymes able to catalyze similar reactions to ENR and EnCR might also have active sites of similar topology, and therefore, ENR could serve as a model for the as yet uncharacterized EnCR—in other words, compounds that inhibit ENR should also, due to the presumed similarity of these two enzymes, inhibit EnCR and should therefore display the mandatory activity against blood-stage parasites, which was verified by an assay against these stages.

Table 1.

Inhibitory effects (IC50 values) of existing PfENR inhibitors on isolated enzyme and blood-stage cultured parasites [a]

| |||

|---|---|---|---|

| PfENR (FabI) | 0.3 µm | 0.8 µm | 48 µm |

| P. falciparum | 3.2 µm (NF54) | 10 µm | 3.3 µm |

| 0.4 µm (K1) | |||

FAS II, and ENR in particular, has been shown to play a key role in the development of liver-stage malaria parasites.[4, 12] ENR-deficient Plasmodium berghei sporozoites are markedly less infective to mice and typically fail to complete liver-stage development in vitro. This defect is characterized by an inability to form intrahepatic merosomes, which normally initiate blood-stage infections.[12] Even though it is not clear how triclosan and other FAS II inhibitors act upon blood-stage parasites, present data suggest that FAS II inhibitors might provide true causal chemoprophylaxis and could simultaneously cure blood-stage Malaria.[4, 12]

Results and Discussion

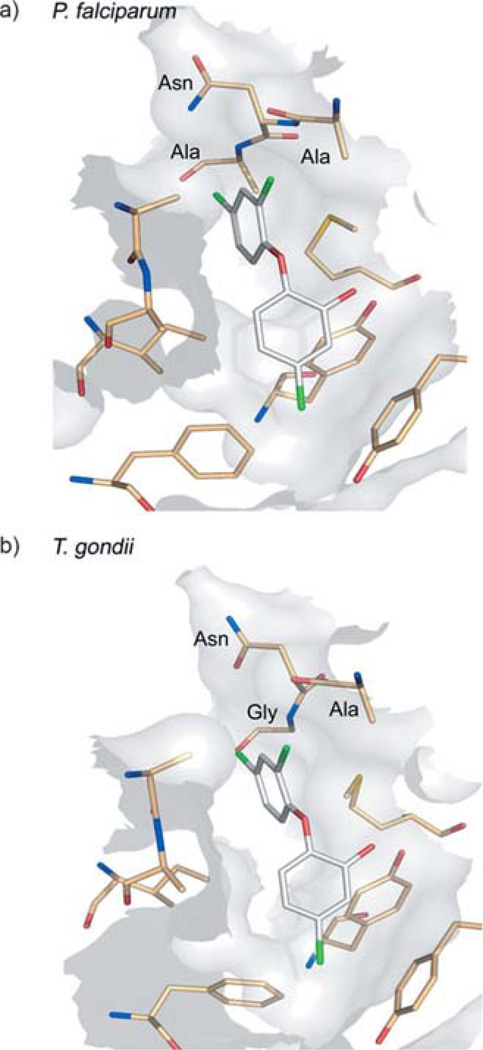

In an effort to find structurally novel, potent FAS inhibitors, we performed a virtual screen based on the two crystal structures of PfENR currently available. The inhibitor binding pocket of both PfENR and Toxoplasma gondii ENR (TgENR) are highly conserved with only one amino acid difference (Figure 1).[16] Therefore, we used a Toxoplasma homologue that was available to us for the enzyme inhibition assay. Of compounds derived from virtual screening, eight molecules were selected with respect to sufficient drug-likeness, chemical diversity, synthetic accessibility and easy scope of variation. In a first step, minor modifications were performed to the chemical structure of these eight promising screening hits in order to overcome obvious metabolic instability or to facilitate convenient synthesis (shown in bold in Table 2). The intended modifications were validated by subsequent docking to ensure predicted binding to the target protein and consistency with the derived pharmacophore were still fulfilled.

Figure 1.

The inhibitor binding sites of a) PfENR and b) TgENR shown here in complex with triclosan (PDB: 1NHG[22] and 2O2S[16]).

Table 2.

Suggested and actual structures of amide-containing salicylic acid derivatives 1 a-h, their antimalarial activity against P. falciparum (IC50) and their cytotoxicity (CC50) in HeLa cells.

| Compd | IC50[a][µm] | CC50[b][µm] | |

|---|---|---|---|

| suggested | synthesized | ||

|

|

7.9±0.3 | 59.3 |

|

as suggested | >50 | <189.2 |

|

as suggested | >50 | <185.7 |

|

as suggested | >50 | <185.6 |

|

|

>50 | 136.4 |

|

|

>50 | <185.7 |

|

as suggested | >50 | 159.2 |

|

|

>50 | 26.11 |

Data represent the mean of n=3 independent experiments performed in triplicate.

Data are the result of four experiments.

Virtual screening

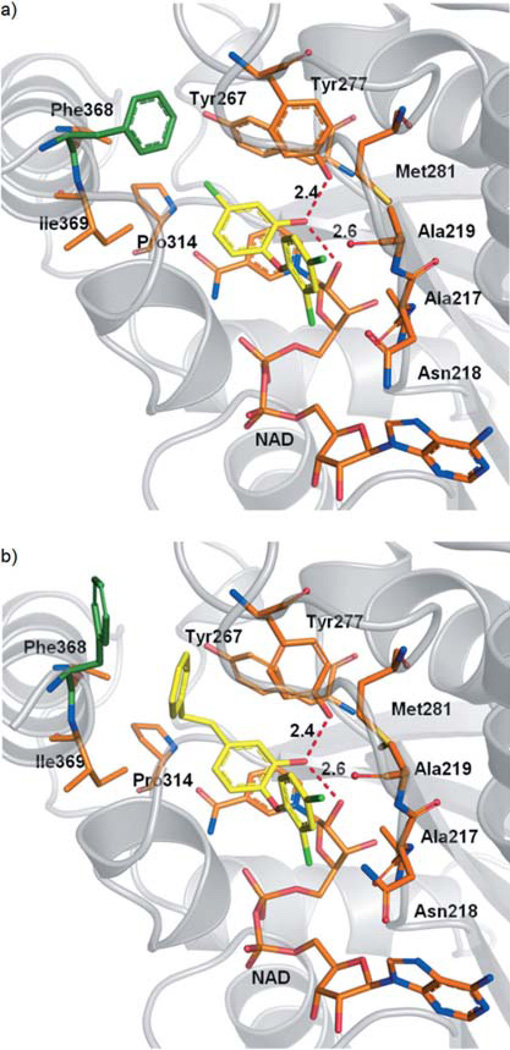

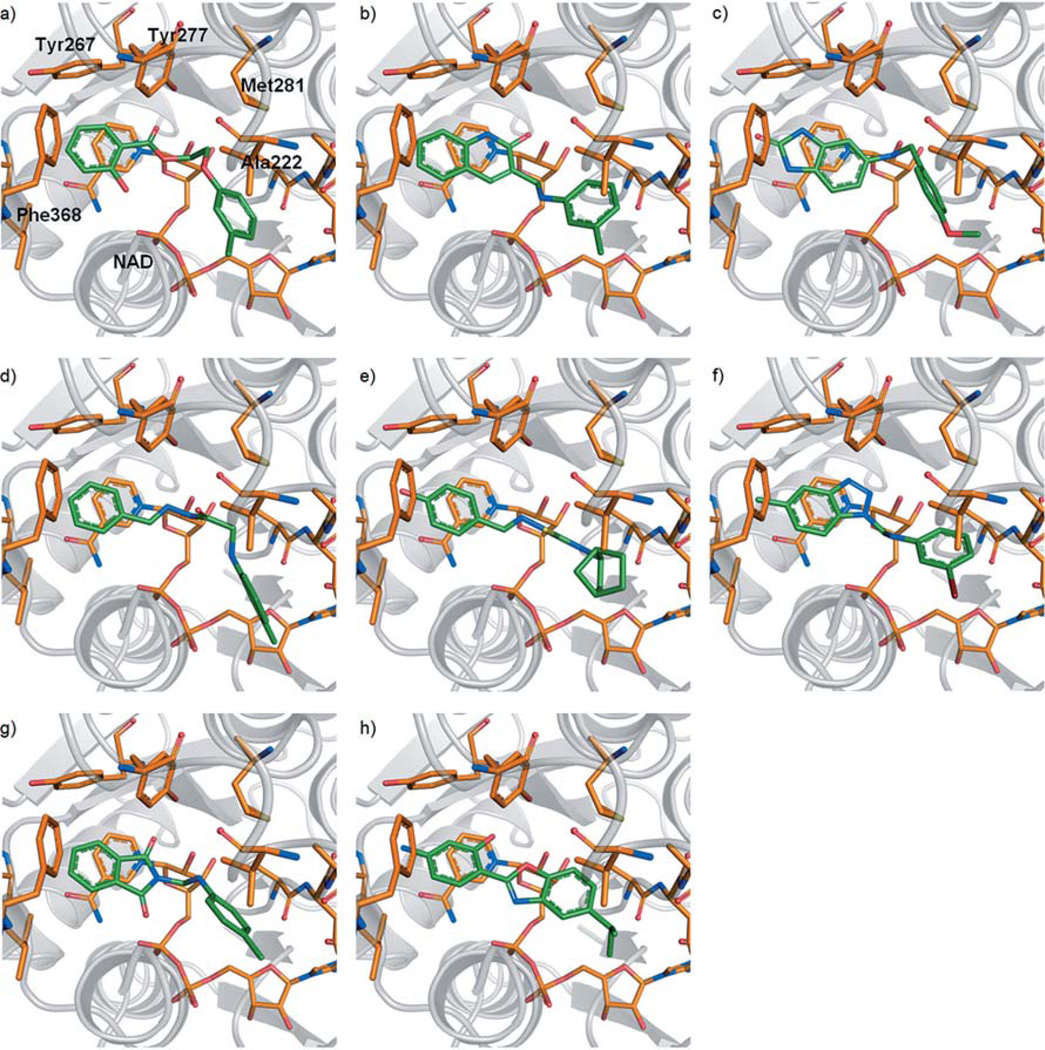

Docking experiments were performed using two different PfENR crystal structures (PDB codes: 2O2Y[16] and 2OOS[19]), as the structures indicate that the active site residue Phe368 can adopt two alternative conformations (Figure 2). The PfENR binding site hosts an NAD+ molecule, which was retained during docking as an integral part of the pocket, since it is tightly bound. Deleting NAD+ would have led to undesirably large hits. A total of 13200 compounds retrieved from an in-house fragment-like library (Table 3) were docked into the respective pocket using GOLD.[20] Results were reranked applying the DSX scoring function.[21] Eight chemically diverse hits were selected (Table 2), which satisfied the pattern of interactions supposed to be essential for inhibitor binding as indicated by the reference crystal structures.[22] Docked compounds were requested to exhibit stacking interactions with the nicotinamide moiety of NAD+ and to form hydrogen bonds with Tyr277 and the 2’-hydroxy group of the nicotinamide ribose. The docking poses obtained are depicted in Figure 3 a–h.

Figure 2.

Co-crystal structures of PfENR and NAD+ with bound inhibitor: a) triclosan (PDB: 2O2Y[16]) and b) 5-substituted triclosan derivative (PDB: 2OOS[19]). Introduction of a large hydrophobic substituent at the 5-position of triclosan induces a conformational transition of Phe368. Hydrogen-bond interactions of the inhibitor phenolic hydroxy group with Tyr277 and the 2’-hydroxy group of the nicotinamide ribose are depicted as red dashed lines. For clarity, Ile323 and Val 222 are not shown.

Table 3.

Physicochemical properties of the fragment-like library used for screening.

| Property | Min | Max |

|---|---|---|

| no. of heavy atoms | 8 | 20 |

| MW[a][g mol−1] | 122 | 360 |

| Lipinski donor | 0 | 4 |

| Lipinski acceptor | 1 | 8 |

| ClogP[b] | −1.2 | 7.6 |

| free rotatable bonds | 0 | 7 |

| TPSA[c][Å2] | 12 | 126 |

Molecular weight (MW);

calculated (C) log P (octanol/water);

total polar surface area (TPSA).

Figure 3.

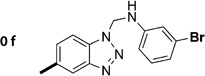

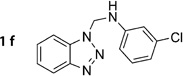

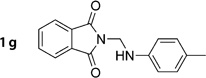

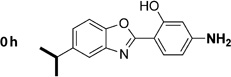

Top-ranked docking poses of the eight most promising hits (0a, e, f, h and 1b–d, g) from virtual screening (a–h). All compounds comprise an aromatic moiety, which is able to establish stacking interactions with the nicotinamide portion of NAD+. Hydrogen bonding with Tyr277 and/or the 2’-hydroxy group of the ribose can be formed by a carbonyl oxygen (a, b, g, h) or by nitrogen atoms (c–f).

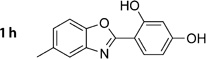

Chemical synthesis

The eight most promising hits were synthesized in one to four steps. Full details are given in the Experimental Section and compound structures are given in Table 2. Compound 1a was accessed via compound 5c, prepared as depicted in Scheme 2. Acidic hydrolysis of the acetyl ester group of 5c yielded salicylic acid amide derivative 1a. Compounds 1b–e were obtained by the formation of their corresponding imines 2b–e using aromatic aldehydes and the respective amino or hydrazine derivatives. All imines were isolated as aromatic Schiff bases prior to their reduction to the corresponding amines using sodium cyanoborohydride. Compounds 1f and 1g were conveniently prepared in a single step via a Mannich condensation using benzotriazole and phthalimide, respectively, formaldehyde and the appropriate aniline derivative. Benzoxazole 1h was synthesized by first condensing the appropriate aldehyde and amino derivative to form imine 2g. From there, we attempted a number of literature methods to access the desired benzoxazole by oxidative cyclization of the 2-(benzylideneamino)phenol using one of the following agents or procedures: 2,3-dichloro-5,6-dicyano-1,4-benzoquinone (DDQ), UV irradiation, active charcoal/O2, lead(IV) acetate. The only procedure that was successful used lead(IV) acetate as the oxidizing agent.

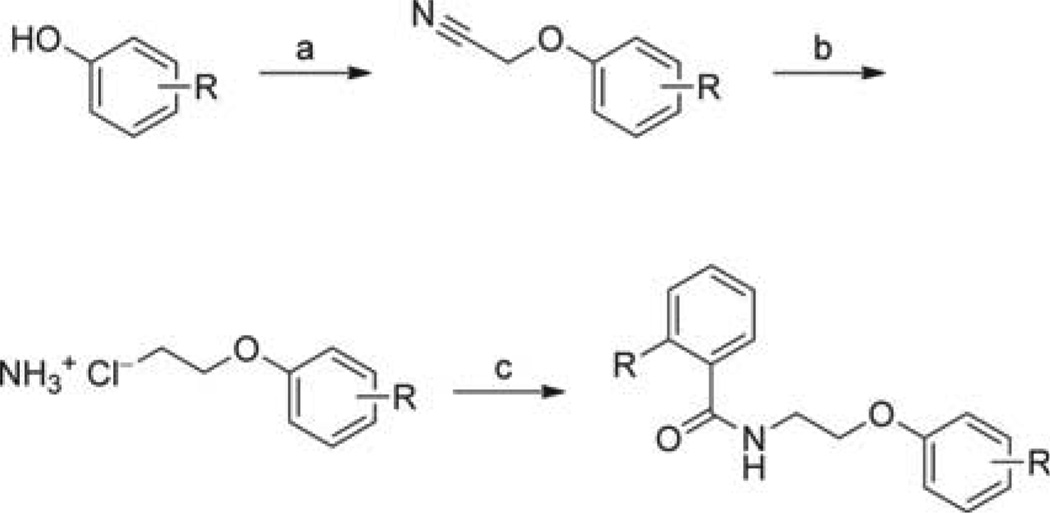

Scheme 2.

Synthesis of aryloxyalkylbenzamide derivatives. Full structures of all compounds tested can be found in Tables 4–6. Reagents and conditions : a) 2-Chloroacetonitrile, K2CO3, KI, 2-butanone, reflux, 6 h; b) LiAlH4, Et2O, RT, 2 h; then HCl/Et2O (2 m), 0 °C, to precipitation; c) Substituted acyl chloride, Et3N, THF, 0 °C →RT, 2 h.

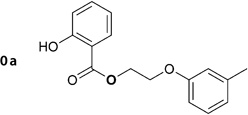

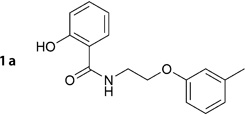

For compound 1a, the virtual screening hit (0a; Table 2) suggested an ester function to link the benzoic acid and the aryloxyalkyl moiety. However, since ester groups are prone to intracellular cleavage by nonspecific esterases, we decided to replace this group with a more stable amide function. In a subsequent docking experiment, no considerable disadvantage in binding compared with the ester analogue was suggested. Scheme 2 illustrates the synthetic route for the preparation of the aryloxyalkylbenzamide derivatives (1a, 5c–g, 5j–k, 6a–g, 6i–x). The reaction of bromoethylbenzamide derivatives with appropriate phenolates under various conditions did not result in the formation of the expected ether; instead, we could only isolate the elimination product. The same was observed using bromoalkylphthalimide derivatives. The reaction of 2-substituted acetonitrile derivatives (2-chloro and 2-bromoacetonitril), however, led to the formation of the desired ether derivatives in good yields. No difference in yield was observed when either 2-bromoacetonitrile or 2-chloroacetonitrile was used. Although the reaction proceeded markedly faster when using the bromo derivative, we decided to use the more readily available chloro derivative. Compared with acetone, 2-butanone as a solvent generally gave rise to a 10% higher yield. The obtained nitrile derivatives were reduced by lithium aluminum hydride to form the corresponding amino derivatives. These were isolated as their hydrochloride salts by the addition of a solution of HCl in ether and were subsequently acylated. For acylation, freshly prepared or commercially available acyl chlorides were used in tetrahydrofuran. In case of salicylic acid derivatives, acetylsalicylic acid chloride was used for acylation. Cleavage of the acetyl ester under acidic conditions furnished the appropriate derivative of salicylic acid (1a, 5d, 5j). This synthetic route allowed us to use virtually any of the easily available phenol and benzoic acid derivatives to produce a series of inhibitors ready for testing.

Biological evaluation and structure–activity relationships

Activity against the asexual blood-stage parasite is considered to be a mandatory property of the intended compounds. Therefore, all synthesized compounds were first tested for their inhibitory activity against cultured blood-stage P. falciparum (multidrug-resistant Dd2 isolate). This way, the compounds could also prove themselves to be sufficiently cell-permeable, which poses a critical hurdle to overcome by appropriate drug design of compounds targeting living parasites intracellularly.

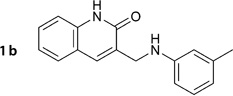

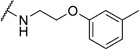

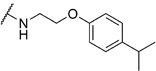

Out of our eight promising hits from virtual screening, the aryloxyalkylbenzamide derivative (1a) inhibited the growth of blood stage Dd2 malaria parasites in the cell-based assay with an IC50 value of 7.9 µm (Table 4). When evaluated against isolated enzyme at a concentration of 1 µm, inhibition of TgENR by 1a was rather poor (10 %). Nevertheless, in the following experiments, we tried to evaluate whether this scaffold could be chemically optimized to obtain a dual inhibitor of both blood-stage Plasmodium and TgENR.

Table 4.

Structures of amide-containing salicylic acid derivatives 1a, 5c-g, and 5j-k, their antimalarial activity against P. falciparum (IC50) and their cytotoxicity (CC50) in HeLa cells.

| |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Compd | R1 | R2 | IC50[a] [µm] | CC50[b][µm] | SI[c] |

| 1a |  |

7.9 ±0.3 | 59.3 | 12.1 | |

| 5c |  |

7.7 ±0.4 | 66.7 | 14.2 | |

| 5d |  |

13.4 ±0.6 | 137.2 | 10.2 | |

| 5e |  |

24.3 ±2.2 | >195.8 | 8.0 | |

| 5f |  |

8.4 ±0.4 | 133.5 | 15.9 | |

| 5g |  |

>50 | 73.1 | ND | |

| 5j |  |

3.0 ±0.2 | > 162.7 | >54 | |

| 5k |  |

|

25.0 ±1.8 | 19.5 | 0.8 |

Data represent the mean of n = 3 independent experiments performed in triplicate.

Data are the result of four experiments.

Selectivity index (SI): CC50 (HeLa)/IC50 (P. falciparum). ND = not determined.

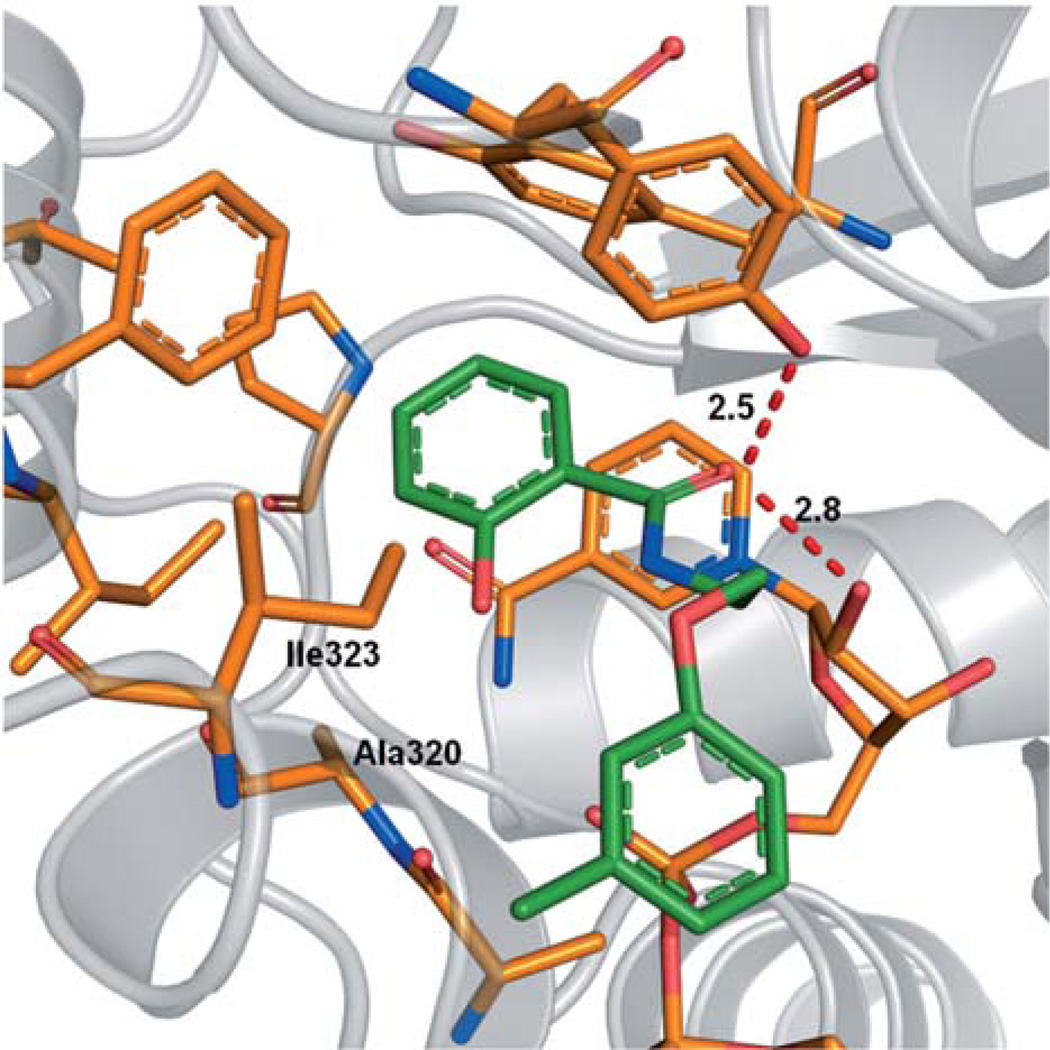

The docking pose of 1a suggests that its polar 2-hydroxy substituent does not specifically interact with the inhibitor binding site of ENR (Figure 4). At this position, nonpolar substituents might lead to an enhanced affinity toward the enzyme as they could potentially interact with the hydrophobic amino acids Ile323 and Ala320. Therefore, we synthesized derivatives 6a and 5e, which either bear such a nonpolar 2-substituent (6a) or lack this group entirely (5e). Interestingly, both derivatives inhibit the TgENR enzyme (Figure 5).

Figure 4.

Docking pose for 1a.

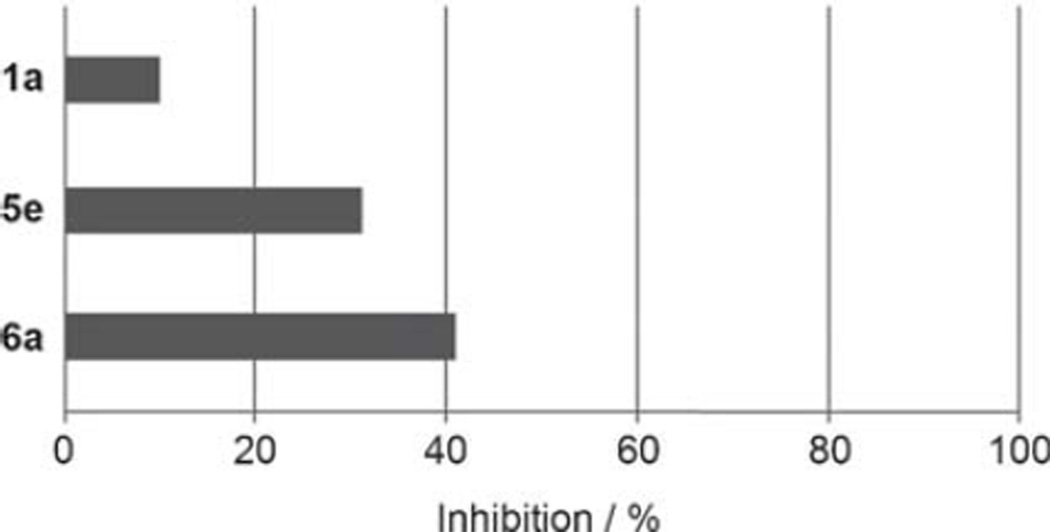

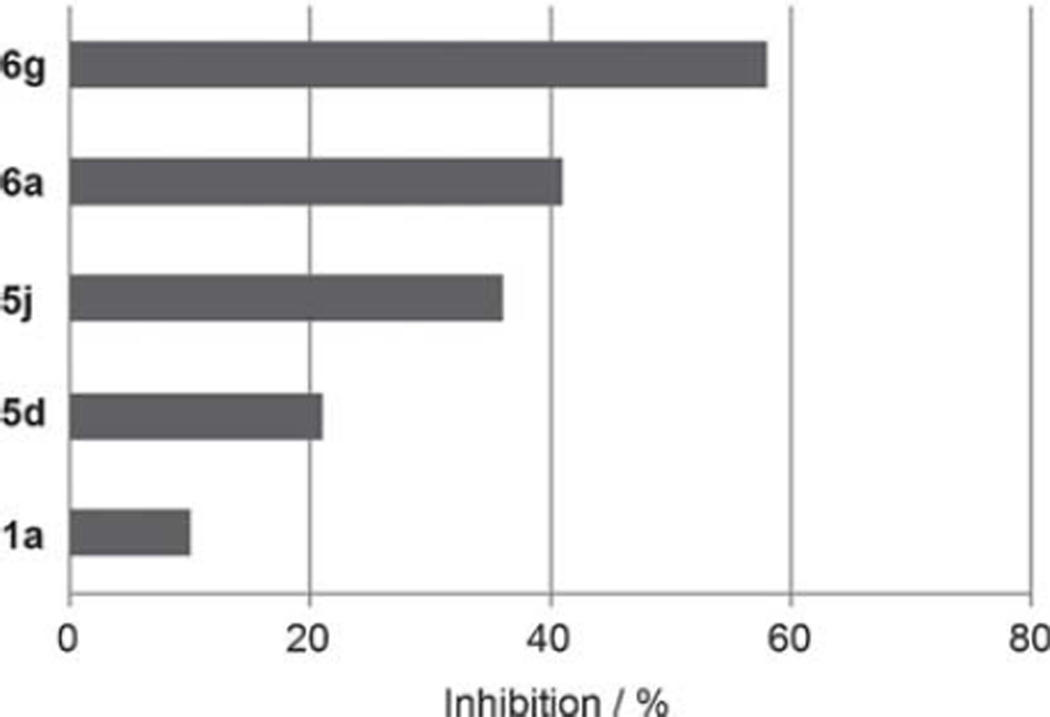

Figure 5.

Inhibition of TgENR by 1a and its derivatives at a concentration of 1 µm.

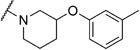

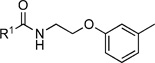

In the cell-based assay, removal of the 2-substituent results in a compound (5e) that exhibits a threefold decrease in activity (IC50=24.3 µm) compared with 1a. However, 2-chloro derivative 6a shows no decrease in activity against blood-stage parasites (IC50=7.5 µm) and displays an even lower cytotoxicity (CC50>172.6 µm, Table 5; c.f. CC50=59.3 µm for 1a, Table 4). As the 2-chlorobenzoic acid derivative (6a) inhibits both bloodstage parasites and TgENR, it qualifies as a lead structure for subsequent optimization.

Table 5.

Structures of amide derivatives of 2-chloro-benzoic acid 6a-g, their antimalarial activity against P. falciparum (IC50) and their cytotoxicity (CC50) in HeLa cells.

| ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Compd | R1 | IC50[a][µm] | CC50[b][µm] | SI[c] |

| 6a |  |

7.5 ± 0.5 | > 172.6 | ND |

| 6b |  |

>50 | 113.7 | ND |

| 6c | 32.6 ± 1.7 | 127.9 | 3.9 | |

| 6d |  |

32.0 ± 1.9 | 60.8 | 1.9 |

| 6e |  |

22.0 ± 0.5 | 105.4 | 4.8 |

| 6f | 2.5 ± 0.1 | 60.1 | 24.4 | |

| 6g |  |

1.7 ± 0.1 | 89.6 | 52.7 |

Data represent the mean of n = 3 independent experiments performed in triplicate.

Data are the result of four experiments.

Selectivity index (SI): CC50 (HeLa)/IC50 (P. falciparum). ND = not determined.

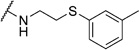

Initially, we evaluated whether selected heteroatoms are mandatory in this compound. We subsequently varied the apparently important 2-substituent introducing a fluoro- and trifluoromethyl group. For the 2-fluoro (IC50=6i, 10.5 µm) and 2-trifluoromethyl (6j, IC50=43.1 µm) derivatives, there was no considerable improvement in the cell-based assay (Table 6). We also prepared a derivative with a 3-chloro-substituted benzoic acid moiety (6l) instead of attachment at the 2-position. Compared with the 2-chloro-substituted derivative (6a), this change led more than a threefold decrease in activity (IC50=26.6 µm) in the cell-based assay. These data led us to conclude that the 2-position of the benzoic acid moiety is optimal for substitution. Apparently, the substituent does not necessarily act as a hydrogen-bond donor or acceptor, as either the hydroxy- or chloro-substituted derivatives show equipotent inhibition. We prepared the sulfur homologue (6d) by using thiocresolate as a nucleophile in the ether synthesis. As there was about a fourfold decrease in activity (IC50=32.0 µm; Table 5) in the cell-based assay, we kept the original composition.

Table 6.

Structures of various aryl amide derivatives, their antimalarial activity against P. falciparum (IC50) and their cytotoxicity (CC50) in HeLa cells.

| ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Compd | R1 | IC50[a]] [µm] | CC50[b] [µm] | SI[c] |

| 6i |  |

10.5 ±0.9 | 170.0 | 16.2 |

| 6j |  |

43.1 ±1.3 | >154.7 | ND |

| 6l |  |

26.6 ±0.8 | 132.9 | 5.0 |

| 6m |  |

>50 | >156.5 | ND |

| 6n |  |

>50 | >142.9 | ND |

| 6o |  |

>50 | 124.6 | ND |

| 6p |  |

50.0 ±0.8 | > 149.4 | ND |

| 6q |  |

10.5 ±0.8 | > 164.1 | ND |

| 6r |  |

>50 | 117.5 | ND |

| 6s |  |

>50 | 154.1 | ND |

| 6t |  |

17.8 ± 1.0 | 119.4 | 6.7 |

| 6u |  |

>50 | > 172.0 | ND |

| 6v |  |

>50 | > 172.0 | ND |

| 6w |  |

>50 | > 133.3 | ND |

| 6x |  |

>50 | > 140.9 | ND |

Data represent the mean of n = 3 independent experiments performed in triplicate.

Data are the result of four experiments.

Selectivity index (SI): CC50 (HeLa)/IC50 (P. falciparum). ND = not determined.

Based on the 2-chloro benzoic acid moiety (6a), a series of derivatives were prepared to optimize the lead structure. Docking of 6a suggested a hydrogen-bonding interaction with the hydroxy group of Tyr267 within the binding site. Therefore, a series incorporating hydrogen-bond acceptor and/or donor functionalities in the 3- and 4-positions of the benzoic moiety were synthesized and tested (6m–n, 6p–r, 6t). None of these compounds showed improved activity in the cell-based assay compared with lead compound 6a. Strikingly, introduction of a polar group in almost all cases led to a complete loss of activity in the cell-based assay. The only derivatives that at least partially maintained activity were the 4-amino (6q, IC50=10.5 µm) and the 4-hydroxy (6t, IC50=17.8 µm). We therefore abandoned the idea of introducing polar groups at the 4-position.

In an attempt to increase the activity through an entropic gain in binding energy, we conformationally rigidified the molecule by incorporating a fixed linker between the aromatic rings by using as a 3-substituted azetidine (6c, IC50=32.6 µm) and a 3-subsitituted piperidine (6b, IC50>50 µm) heterocycles. As these modifications were clearly detrimental to the activity in the cell-based assay, it seems that the most favorable conformations required for binding of the inhibitors are not easily accessible by incorporation of the two tested rigid linkers. This prompted us to retain the original oxyethylamide moiety as a linker.

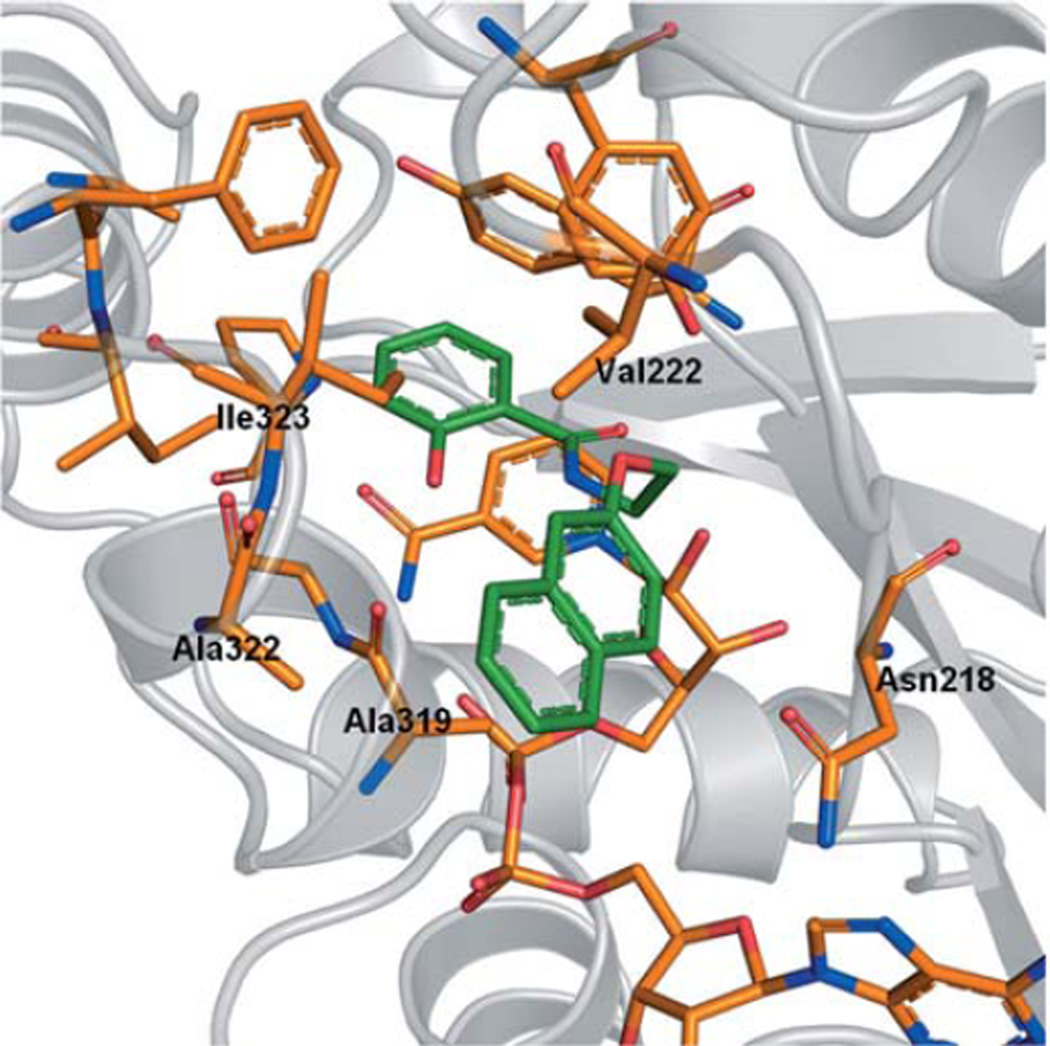

Combinatorial library

To elaborate the chemical space and the potential of aryloxyalkylbenzamide derivatives 1a, 5c–g, 5j–k, 6a–g, 6i–x, a combinatorial virtual library was generated considering commercially available agents. This library contained about 430 000 molecules with a molecular weight (MW) of less than 600 Da. A subgroup of 10000 compounds was preselected from the computed library using a coarse-grained docking procedure, followed by a second, more extensive docking run. The results were reranked by DSX and visually inspected. The most promising derivatives were selected for synthesis and subsequent biological testing. The top-ranked compound comprised a naphthaleneoxy (6g) instead of the m-tolyloxy moiety found in 6a. In our model, this derivative is predicted to exhibit the same interaction patterns as the initial compound (1a) but the increased molecular surface of the naphthyl moiety likely provides more van der Waals interactions with hydrophobic residues Val222, Ala319, Ala322, Ile323, and additionally Asn218 (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Docking pose for 5j.

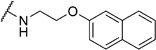

Docking into the crystal structure suggested that the oxyaryl moiety of 4-isopropylbenzoxy 6e, 5,6,7,8-tetrahydronaphthaleneoxy 6f, and naphthaleneoxy 6g interacts with lipophilic amino acid residues. We synthesized these compounds and observed a decline in activity in the cell-based assay for the isopropylbenzeneoxy derivative (6e; IC50=22.0 µm). In contrast, for tetrahydronaphthyloxy derivative 6f (IC50=2.5 µm) and naphthyloxy derivative 6g (IC50=1.7 µm), we observed a three- to fourfold improvement in activity as determined in a cell-based assay. At a concentration of 1 µm, 6g showed slightly higher inhibition (58%) in the TgENR enzyme assay when compared with lead compound m-tolyloxy 6a (41%) (Figure 7). In addition, 6g displayed a selectivity index (SI) of more than 50 (Table 5).

Figure 7.

Inhibition of TgENR by structurally optimized derivatives of 1a at a concentration of 1 µm.

Encouraged by this observation, we also prepared derivative 5j, which includes both a naphthoxy- and a salicylic acid moiety connected by an ethylamine linker. Compound 5j is the most active derivative in our series of salicylic acid amides in the cell-based assay (IC50=3.0 µm; Table 4). Compound 5j also inhibits TgENR activity by 58% at 1 µm and displays an SI value of more than 50.

In order to confirm that this improvement in activity can be attributed to a directional interaction rather than to increased lipophilicity, we also prepared 1-naphthoxy derivative 5k. This compound showed an eightfold decrease in activity (IC50= 25.0 µm) compared with 2-naphthoxy derivative 5j. Therefore, compounds 6g and 5j represent the most promising derivatives in this series so far and were tested for plasmodial sporozoite- and liver-stage inhibition.

Evaluation of the effect on pre-erythrocytic parasites

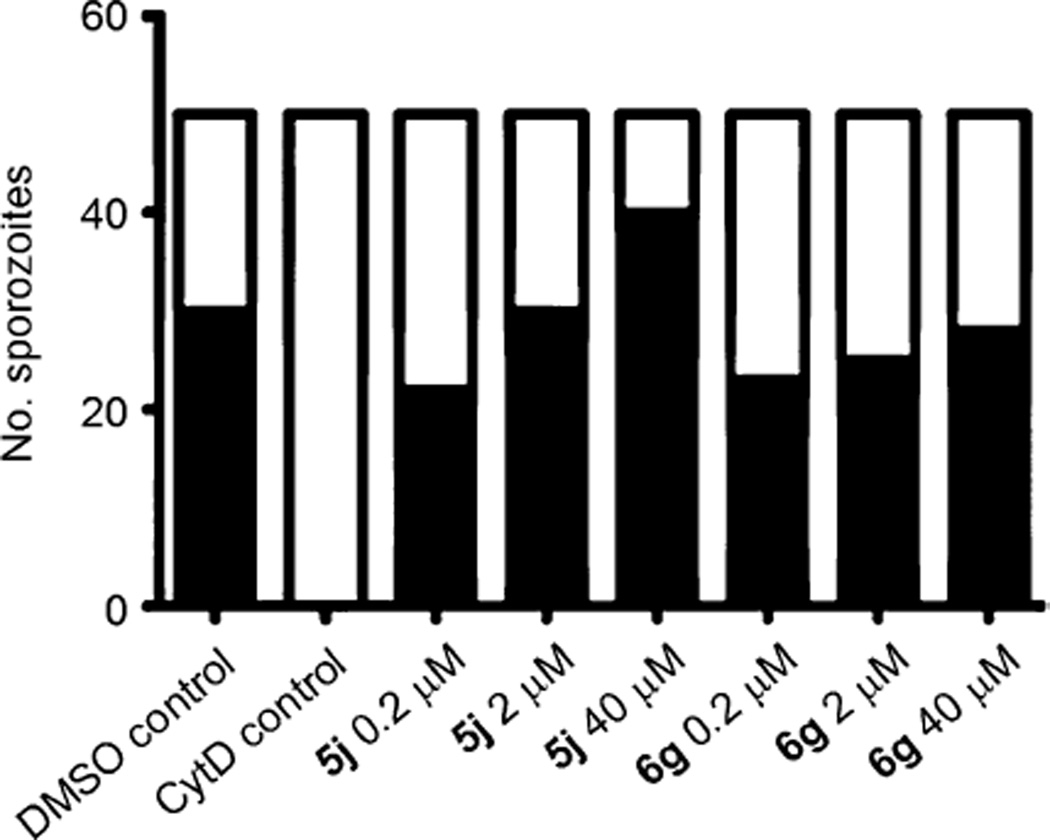

In order to address the question of whether compounds 6g and 5j have an effect on the motor machinery of the parasite, crucial for the invasion of liver cells (that is to say the infective sporozoites), we first performed two-color host-cell invasion assays. Salivary gland sporozoites of P. berghei were applied to immortalized human hepatoma cell lines (HuH7) and allowed to invade for 90 min in the presence of different concentrations of either compound 6g or 5j. Quantification of the numbers of extracellular versus intracellular parasites revealed that we could not observe any effect on the invasion of liver cells compared with the DMSO-treated control (Figure 8).[23, 24]

Figure 8.

Compounds 6g and 5j have no effect on the invasion of HuH7 cells in vitro. Infectious P. berghei sporozoites were pre-incubated with either 0.5% DMSO, 10 µm cytochalasin D (CytD), or test compound at different concentrations (0.2 µm, 2 µm or 40 µm) and allowed to invade for 90 min under drug cover. After sporozoite double-staining, 50 sporozoites were counted and classified as invaded (inside: ■) or non-invaded (outside: □).

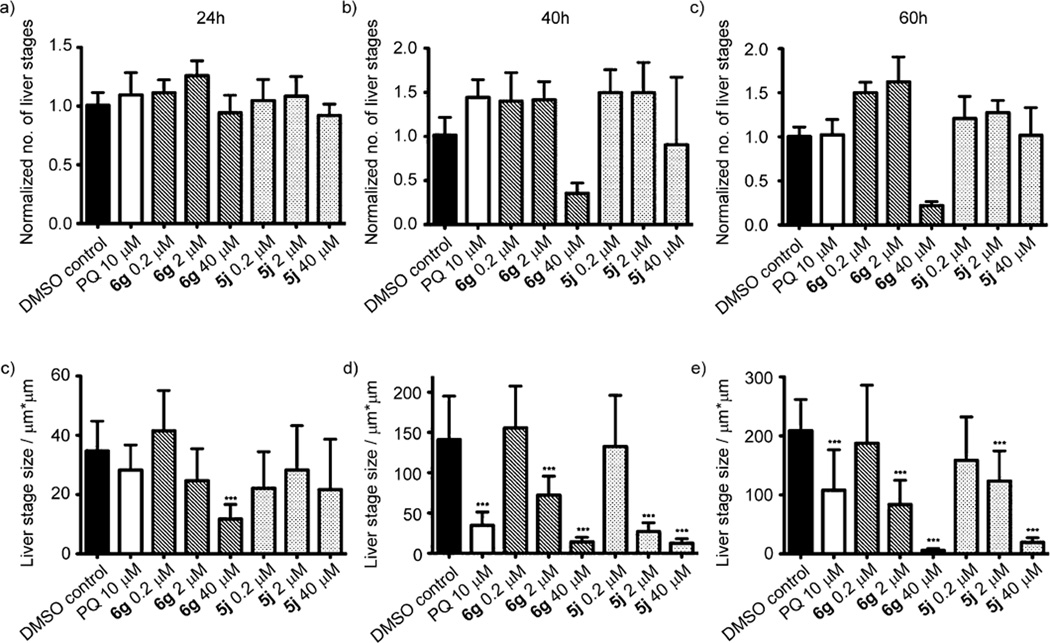

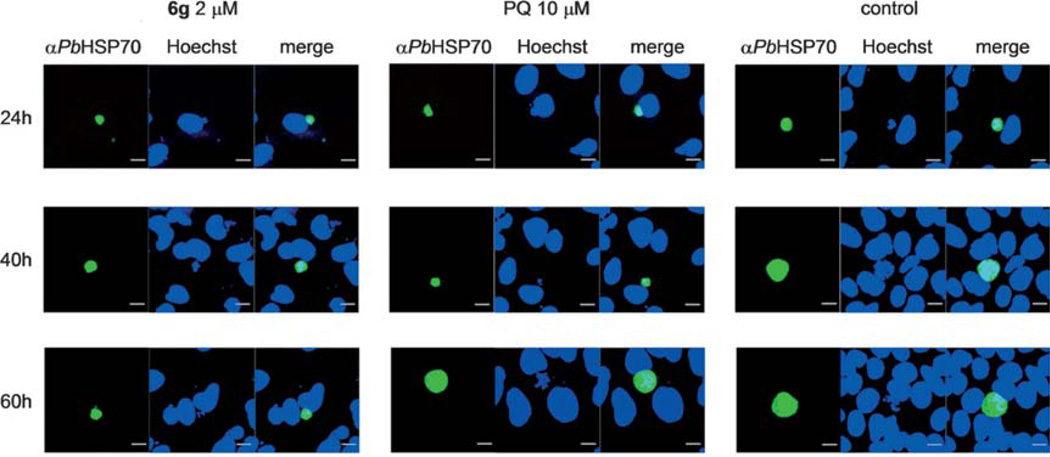

Next we tested the inhibitory effect of compounds 6g and 5j on the development of the exoerythrocytic form of the parasite (the clinically silent liver stage) by applying 6g or 5j to the culture medium after invasion of infectious P. berghei sporozoites into HuH7 cells. After early- (24 h), mid- (40 h) and late-(60 h) intrahepatic development, cells were fixed and liver stage parasites were visualized by immunostaining of intracellular malarial HSP70.[24, 25] Interestingly, the number of liver stage parasites determined by immunofluorescence microscopy was not significantly different under the various conditions tested (Figure 9a–c), except for a decrease in liver-stage parasite numbers when compound 6g was applied at a concentration of 40 µm (Figure 9a). However, growth inhibition is caused by compound incubation, resulting in fairly small-sized liver-stage parasites, and as such, we most likely failed to incorporate every single fluorescent liver-stage parasite. Using confocal microscopy with subsequent image processing, we measured the diameter of the maturing intrahepatic liver-stage parasites as an indication of the developmental status. Strikingly, we found that at reasonably early time points (24 h) after sporozoite inoculation, treatment with 6g at 40 µm caused a significant developmental delay compared with the infection control (Figure 9d; p<0.0001); representative confocal images are shown in Figure 10. More importantly, at later time points (40 h and 60 h) during liver-stage development, we observed a significant attenuation of liver-stage growth even at lower concentrations (2 µm) for both compounds 6g and 5j (Figure 9 e,f; p <0.0001).

Figure 9.

Establishment of exoerythrocytic stages is not impaired but the development is significantly compromised in vitro. 24 h, 40 h or 60 h after infection of human hepatoma HuH7 cells with infectious P. berghei sporozoites, cells were fixed, stained with anti-Pb HSP70 and analyzed by immunofluorescence microscopy. We could not observe any difference in numbers of exoerythrocytic forms (a–c); only compound 6g applied at a concentration of 40 µm caused a prominent decrease in the number of liver stage parasites at 40 h and 60 h after infection (b and c). Measurements of liver-stage growth over time revealed that already at 24 h, compound 6g at 40 µm caused significant developmental delay compared with the DMSO control (d). At later time points, even 2 µm of either compound 6g or 5j could arrest the growth of exoerythrocytic stages significantly (e and f). Primaquine (PQ) at 10 µm was used as a positive control (p <0.0001).

Figure 10.

Representative confocal pictures of malarial exoerythrocytic stages at 24 h, 40 h and 60 h after infection with infectious PbANKA sporozoites (scale bar=10 µm). Primaquine (PQ) at 10 µm was used as a positive control.

Interestingly, when compared with primaquine, a member of the 8-aminoquinoline group of antimalarial agents exclusively active against the intrahepatic stages, at a standard concentration of 10 µm, compounds 6g and 5j exert more potent inhibition of malarial liver-stage growth with determined IC90 values at 60 h of 2.79 µm and 3.14 µm, respectively. The activity of primaquine in liver cells relies on metabolism of the parent compound to an active metabolite, while our compounds presumably act in the nonmetabolized state. One could argue that the low in vitro activity of primaquine could be due to poor metabolism to the active agent in this cell system. However, it has been shown that, in HuH7 cells, DMSO significantly increases the mRNA levels of most drug-metabolizing enzymes and liver-specific proteins.[26] As described above, compounds 6g and 5j inhibit blood-stage parasites with IC50 values of 1.7 µm and 3.0 µm, respectively, making them more active against these parasites than primaquine, for which the IC50 is reported to be in the range of 10–20 µm.[27]

Conclusions

We have presented novel type II fatty acid biosynthesis (FAS II) inhibitors that inhibit the growth of both blood-stage and preerythrocytic (liver-stage) malarial parasites. The lead compounds identified are structurally different from other inhibitors of FAS in malaria parasites (for a recent Review, see Ref. [28]). Compared with primaquine, the gold-standard, compounds 6g and 5j show at least a fivefold enhanced inhibitory effect on both the development of clinically silent liver-stage as well as disease-inducing erythrocytic blood-stage P. falciparum parasites. Due to their low cytotoxicity in human (HeLa) cells and their overall drug-like chemical properties (Table 7), these compounds can be considered as promising candidates for further development and evaluation in animal models of malaria infection. Altogether, this work provides evidence for novel concepts in chemical treatment of pre-erythrocytic malarial parasites and the pharmacological management of Plasmodium infections.

Table 7.

Physicochemical properties of compound 6g.

| Property | |

|---|---|

| no. of heavy atoms | 23 |

| MW[a] [g mor−1] | 325.8 |

| Lipinski donor | 1 |

| Lipinski acceptor | 3 |

| ClogP | 4.6260 |

| free rotatable bonds | 6 |

| TPSA[b] [Å2] | 38.33 |

Molecular weight (MW);

calculated (C) logP (octanol/water);

total polar surface area (TPSA).

Experimental Section

1H NMR and 13C NMR spectra were recorded on a Jeol ECA-500 and a Jeol EX-400 spectrometer. Mass spectra (MS) were recorded on a Varian MAT CH7a and a S.I.S VG 7070. Infrared (IR) spectra were recorded on an Bruker Alpha-P attenuated total reflectance fourier transform (ATR FT) spectrometer. Melting points (mp) were measured on a Barnstead Thermolyne MEL-TEMP-II microscope and are uncorrected. Reagents and solvents were purchased from ABCR, Alfa Aesar, Fluorochem, Matrix Scientific, Merck, Sigma–Aldrich and Thermo Fisher Scientific, and were purified by distillation or recrystallization, if necessary. Chromatography refers to column flash chromatography using the indicated eluent and Macherey–Nagel silica gel (0.040–0.063 µm).

General procedure 1: Preparation of imine derivatives

The respective amino or hydrazino derivative and the appropriate aldehyde were dissolved in MeOH (20 mL). The mixture was heated at reflux for 3 h and then poured into H2O (250 mL). A solid was separated and recrystallized.

General procedure 2: Reduction of imine derivatives

The respective imino derivative, NaBH3CN (2 equiv) and glacial AcOH (3 equiv) where suspended in 1,2-dichloroethane (15 mL). The reaction mixture was stirred for 2 h at RT. The reaction was quenched with saturated aq Na2CO3 and extracted with CH2Cl2 (3×30 mL). The organic layer was separated and dried over MgSO4, the solvent was removed in vacuo, and the crude product was purified by chromatography.

General procedure 3: Preparation of aryl ether derivatives

The respective phenol derivative and K2CO3 (2 equiv) were suspended in 2-butanone (20 mL). 2-Chloroacetonitrile (1 equiv) and KI (20 mg) were added, and the reaction mixture was heated at reflux for 6 h. The same volume of a 1m aq NaOH solution was added, and the mixture was extracted with twice the volume of Et2O (3×40 mL). The organic layers were separated and dried over MgSO4. The solvent was evaporated in vacuo, and the product was used without further purification.

General procedure 4: Reduction of nitrile groups

The respective nitrile derivative was dissolved in Et2O and cooled to 0 °C. A 4 m solution of LiAlH4 (0.5 equiv) in Et2O was added, and the reaction mixture was stirred for 2 h. The reaction mixture was cooled to 0 °C, and water was added dropwise. The organic layer was separated, dried over MgSO4 and evaporated to a volume of 20 mL. The mixture was cooled to 0°C, and a 2 m HCl solution in Et2O was added dropwise until further formation of a solid ceased. The solid was collected and washed with Et2O.

General procedure 5: Acylation of amino derivatives

a) The respective amino derivative and Et3N (1 equiv; or 2 equiv when a hydrochloride is used in the reaction) was dissolved in THF (20 mL) and the respective acyl chloride (1 equiv) was added. The reaction mixture was stirred for 2 h at RT and then poured into H2O (250 mL). A solid was separated and recrystallized.

b) The respective amino derivative and Et3N (1 equiv; or 2 equiv when a hydrochloride is used in the reaction) were dissolved in CH2Cl2 (20–50 mL). The respective acyl chloride (1 equiv) was added, and the reaction mixture was stirred for 2 h at RT. After the solvent was removed in vacuo, the crude product was purified by chromatography.

General procedure 6: Hydrolysis of ester groups

The respective ester derivative was dissolved in glacial AcOH (25 mL) and 32% aq HCl (1 mL) was added. The reaction mixture was heated at reflux for 30 min and then poured into H2O (250 mL). A solid was separated and recrystallized.

General procedure 7: Preparation of acyl chlorides

The respective carboxylic acid was dissolved in CH2Cl2 (sufficient for complete dissolution) and oxalyl chloride (1.5 equiv) was added. The reaction mixture was stirred for 2 h at RT, and the solvent and excess oxalyl chloride were evaporated in vacuo.

2-Hydroxy-N-(2-(m-tolyloxy)ethyl)benzamide (1a)

Prepared according to general procedure 6 from 5c (410 mg, 1.31 mmol), glacial AcOH (25.0 mL, 0.44 mol) and 32% aq HCl (1.0 mL, 10.3 mmol). Recrystallization from toluene gave a white crystalline solid (327 mg, 92%); mp: 92°C; 1H NMR (400 MHz, [D6]DMSO): δH=2.26 (s, 3 H), 3.67 (ps q, J =5.7 Hz, 2 H), 4.11 (t, J =5.8 Hz, 2 H), 6.74–6.78 (m, 3H), 6.87–6.92 (m, 2 H), 7.13–7.17 (m, 1H), 7.38–7.42 (m, 1 H), 7.86–7.89 (m, 1H), 9.02 (t, J =5.8 Hz, 1 H), 12.45 ppm (s, 1H); 13C NMR (100 MHz, [D6]DMSO): δC=21.0, 38.6, 65.6, 111.4, 115.1, 115.3, 117.3, 118.6, 121.4, 127.9, 129.2, 133.7, 139.0, 158.3, 159.7, 168.9 ppm; IR (ATR): ṽ =3356, 3054, 2943, 1645, 1583, 1539, 1490, 1251, 1162, 752 cm−1; MS (ESI): m/z (%): 272 [M+H]+ (100), 294 [M+Na]+ (84), 565 [2M+Na]+ (20); HRMS (EI): m/z calcd for [M]+: 271.1208, found: 271.1193.

3-((m-Tolylamino)methyl)chinolin-2-ol (1b)

Prepared according to general procedure 2 from 2f (302 mg, 1.15 mmol), NaBH3CN (145 mg, 2.3 mmol) and glacial AcOH (0.21 mL, 3.45 mmol). Purification by chromatography (Et2O) gave a white crystalline solid (238 mg, 78%); mp: 185°C; 1H NMR (400 MHz, [D6]DMSO): δH=2.15 (s, 3H), 4.13 (d, J =5.4 Hz, 2H), 5.99 (t, J =6.0 Hz, 1H), 6.35–6.41 (m, 3 H), 6.92–6.95 (m, 1 H), 7.11–7.15 (m, 1H), 7.30–7.59 (m, 3 H), 7.72 (s, 1H), 11.84 ppm (s, 1H); 13C NMR (100 MHz, [D6]DMSO): δC=21.3, 41.9, 109.3, 112.8, 114.8, 116.9, 119.1, 121.8, 127.4, 128.8, 129.5, 131.1, 134.6, 137.7, 137.8, 148.4, 161.7 ppm; IR (ATR): ṽ = 3340, 3015, 2971, 2822, 2445, 1645, 1603, 1568, 1425, 770, 747, 696 cm−1; MS (ESI): m/z (%): 265 [M+H]+ (96), 287 [M+Na]+ (100); HRMS (EI): m/z calcd for [M]+: 264.1263, found: 264.1265.

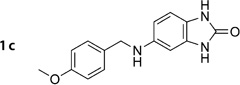

5-(4-Methoxybenzylamino)-1H-benzo[d]imidazol-2-(3H)-one (1c)

Prepared according to general procedure 2 from 2e (403 mg, 1.51 mmol), NaBH3CN (190 mg, 3.02 mmol) and glacial AcOH (0.26 mL, 4.53 mmol). Purification by chromatography (Et2O) gave a white crystalline solid (159 mg, 39%); mp: 267°C; 1H NMR (400 MHz, [D6]DMSO): δH=3.72 (s, 3H), 4.13 (d, J =5.7 Hz, 2H), 5.71 (t, J =5.7 Hz, 1 H), 6.20–6.22 (m, 2 H), 6.60–6.62 (m, 1 H), 6.86–6.88 (m, 2 H), 7.25–7.27 (m, 2H), 10.01 (s, 1 H), 10.15 ppm (s, 1H); 13C NMR (100 MHz, [D6]DMSO): δC=46.7, 54.9, 93.8, 105.3, 108.7, 113.6, 120.5, 128.2, 130.5, 132.2, 143.8, 155.4, 157.9 ppm; IR (ATR): ṽ =3397, 3010, 2955, 2836, 1747, 1607, 1509, 1460, 1179, 1029, 734, 715 cm−1; MS (ESI): m/z (%): 121 (68), 270 [M+H]+(100), 292 [M+Na]+ (31); HRMS (EI): m/z calcd for [M]+: 269.1164, found: 269.1175.

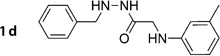

N’-Benzyl-2-(m-tolylamino)acetohydrazide (1d)

Prepared according to general procedure 2 from 2c (444 mg, 1.66 mmol), NaBH3CN (209 mg, 3.32 mmol) and glacial AcOH (0.30 mL, 4.98 mmol). Purification by chromatography (Et2O) gave a white crystalline solid (272 mg, 61%); mp: 76 °C; 1H NMR (400 MHz, [D6]DMSO): δH=2.17 (s, 3 H), 3.59 (d, J =6.2 Hz, 2 H), 3.85 (d, J = 5.0 Hz, 2 H), 5.21–5.26 (m, 1H), 5.71 (t, J =6.2 Hz, 1H), 6.32–6.41 (m, 3 H), 6.93–6.97 (m, 1 H), 7.23–7.38 (m, 5 H), 9.29 ppm (d, J =6.1 Hz, 1H); 13C NMR (100 MHz, [D6]DMSO): δC=21.3, 45.3, 54.5, 109.5, 112.9, 117.2, 126.9, 128.1, 128.5, 128.6, 137.7, 138.6, 148.2, 169.5 ppm; IR (ATR): ṽ =3316, 3230, 3028, 2920, 1645, 1605, 1509, 1481, 746, 688 cm−1; MS (ESI): m/z (%): 270 [M+H]+ (49), 292 [M+Na]+ (100), 561 [2M+Na]+ (22); HRMS (EI): m/z calcd for [M]+: 269.1528, found: 269.1548.

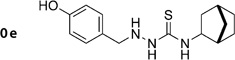

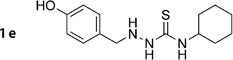

4-Cyclohexyl-1-(4-hydroxybenzyl)thiosemicarbazide (1e)

Prepared according to general procedure 2 from 2d (351 mg, 1.27 mmol), NaBH3CN (160 mg, 2.54 mmol) and glacial AcOH (0.22 mL, 3.81 mmol). Purification by chromatography (Et2O) gave a white crystalline solid (103 mg, 29%); mp: 165°C; 1H NMR (400 MHz, [D6]DMSO): δH=1.07–1.68 (m, 10H), 3.67 (d, J =4.4 Hz, 2 H), 3.86–3.95 (m, 1 H), 5.18 (t, J =4.3 Hz, 1H), 6.67–6.69 (m, 2H), 7.09–7.11 (m, 2 H), 7.34 (d, J =8.6 Hz, 1H), 8.54 (br s, 1 H), 9.26 ppm (s, 1H); 13C NMR (100 MHz, [D6]DMSO): δC=24.5, 25.1, 32.0, 51.1, 53.9, 115.0, 128.2, 130.1, 156.6, 179.3 ppm; IR (ATR): ṽ =3321, 3181, 3021, 2917, 2851, 1568, 1514, 1445, 1211, 831 cm−1; MS (ESI): m/z (%): 280 [M+H]+(100), 302 [M+Na]+ (77), 581 [2M+Na]+ (21); HRMS (EI): m/z calcd for [M]+: 279.1405, found: 279.1436.

N-((1H-Benzo[d][1,2,3]triazol-1-yl)methyl)-3-chloroaniline (1f)

3-Chloroaniline (0.30 mL, 2.84 mmol), paraformaldehyde (94 mg, 3.12 mmol) and 1H -benzotriazole were dissolved in EtOH (20 mL). The reaction mixture was heated at reflux for 2 h. Upon cooling, a solid was separated and recrystallized from EtOH to give a white crystalline solid (485 mg, 66%); mp: 181°C (181 °C); 1H NMR (400 MHz, [D6]DMSO): δH=6.14 (d, 1H), 6.61–6.64 (m, 1 H), 6.77–6.79 (m, 1 H), 6.88–6.89 (m, 1 H), 7.07–7.11 (m, 1H), 7.37–7.41 (m, 1 H), 7.52–7.58 (m, 2 H), 8.01–8.04 ppm (m, 2H); 13C NMR (100 MHz, [D6]DMSO): δC=56.3, 111.0, 111.5, 112.2, 117.2, 119.0, 124.0, 127.2, 130.5, 132.0, 133.6, 145.3, 147.3 ppm; IR (ATR): ṽ =3299, 3051, 2955, 1699, 1589, 1270, 1151, 735, 681 cm−1; MS (ESI): m/z (%): 120 (100), 281 [M+Na]+ (32); HRMS (EI): m/z calcd for [M]+: 258.0672, found: 258.0638. Analytical data are consistent with previous findings.[29]

2-((p-Tolylamino)methyl)isoindoline-1,3-dione (1g)

p -Toluidine (0.50 mL, 4.54 mmol), paraformaldehyde (150 mg, 5.00 mmol) and phthalimide were dissolved in EtOH (20 mL). The reaction mixture was heated at reflux for 2 h. Upon cooling, a solid was separated and recrystallized from EtOH to give a white crystalline solid (932 mg, 77%); mp: 171°C (174.5–175.5 °C); 1H NMR (400 MHz, [D6]DMSO): δH=2.10 (s, 3H), 4.97 (s, 2H,), 6.70–6.73 (m, 2 H), 6.87–6.89 (m, 2 H), 7.82–7.89 ppm (m, 4H); 13C NMR (100 MHz, [D6]DMSO): δC=19.9, 47.3, 112.7, 123.1, 129.3, 134.2, 134.6, 143.5, 167.9 ppm; IR (ATR): ṽ =3370, 3040, 2962, 1707, 1519, 1395, 1243, 723, 509 cm−1; MS (ESI): m/z (%): 120 (100), 267 [M+H]+(56), 289 [M+Na]+ (68), 555 [2M+Na]+ (18); HRMS (EI): m/z calcd for [M]+: 266.1055, found: 266.1059. Analytical data are consistent with previous findings.[30]

4-(5-Methylbenzo[d]oxazol-2-yl)benzene-1,3-diol (1h)

Diol 2g(303 mg, 1.25 mmol) was dissolved in glacial AcOH (10 mL) and treated with Pb(OAc)4 (612 mg, 1.38 mmol). The reaction mixture was stirred for 5 min at RT and then poured into H2O (100 mL). A solid was separated and purified by chromatography (Et2O) to give a red crystalline solid (147 mg, 49%); mp: 220°C; 1H NMR (400 MHz, [D6]DMSO): δH=2.42 (s, 3 H), 6.46–6.54 (m, 2 H), 7.18–7.23 (m, 1 H), 7.54–7.82 (m, 3H), 10.40 (s, 1 H), 11.30 ppm (s, 1H); 13C NMR (100 MHz, [D6]DMSO): δC=20.9, 101.9, 102.7, 108.6, 110.0, 118.3, 125.8, 128.6, 134.4, 139.6, 146.6, 159.7, 162.6, 162.9 ppm; IR (ATR): ṽ =3357, 2923, 1634, 1600, 1480, 1415, 1244, 1145, 796 cm−1; MS (ESI): m/z (%): 242 [M+H]+ (100); HRMS (EI): m/z calcd for [M]+: 241.0739, found: 241.0742.

Methyl-2-(m-tolylamino)acetate (2a)

m -Toluidine (2.00 mL, 18.5 mmol) was dissolved in acetone and treated with methyl 2-bromoacetate (0.86 mL, 9.25 mmol). The reaction mixture was stirred for 2 h at RT, and the solvent was then removed in vacuo. Purification by chromatography (Et2O) gave a light brown crystalline solid (1.48 g, 89%); 1H NMR (400 MHz, [D6]DMSO): δH=2.17 (s, 3 H), 3.64 (s, 3H), 3.88 (d, J =6.5 Hz, 2H), 5.90 (t, J =6.4 Hz, 1 H), 6.31–6.40 (m, 3 H), 6.93–6.97 ppm (m, 1H); 13C NMR (100 MHz, [D6]DMSO): δC=21.2, 44.5, 51.4, 109.2, 112.7, 117.2, 128.6, 137.7, 147.9, 171.7 ppm. Analytical data are consistent with previous findings.[31]

2-(m-Tolylamino)acetohydrazide (2b)

Prepared as previously described[32] from 2a (1.04 g, 5.80 mmol) and a 64% aq N2H4·H2O solution (0.66 mL, 8.70 mmol). Recrystallization from toluene gave a white crystalline solid (936 mg, 90%); 1H NMR (400 MHz, [D6]DMSO): δH=2.17 (s, 3 H), 3.59 (d, J =6.2 Hz, 2 H), 4.23 (br s, 2 H), 5.73 (t, J =6.1 Hz, 1H), 6.32–6.39 (m, 3H), 6.936.97 (m, 1 H), 9.04 ppm (br s, 1H); 13C NMR (100 MHz, [D6]DMSO): δC=21.2, 45.3, 109.5, 112.9, 117.2, 128.6, 137.7, 148.2, 169.4 ppm.

(E/Z)-N’-Benzylidene-2-(m-tolylamino)acetohydrazide (2c)

Prepared according to general procedure 1 from 2b (504 mg, 2.38 mmol) and 4-hydroxybenzaldehyde (291 mg, 2.38 mmol). Recrystallization from Et2O gave a yellow crystalline solid (528 mg, 80%); 1H NMR (400 MHz, [D6]DMSO): δH=2.18 (s, 3 H), 3.78/4.21 (2 d, J =6.1, 5.9 Hz, 0.8/1.2 H), 5.61/5.90 (2 t, J =5.9, 6.1 Hz, 0.4/ 0.6 H), 6.37–6.45 (m, 3 H), 6.94–6.99 (m, 1 H), 7.42–7.48 (m, 3 H), 7.66–7.74 (m, 2 H), 8.02/8.25 (2 s, 0.4/0.6 H), 11.42/11.51 ppm (2 s, 0.4/0.6 H); 13C NMR (100 MHz, [D6]DMSO): δC=21.2, 43.7/46.0, 109.5, 112.9/113.0, 117.0/117.4, 126.8/126.9, 128.6/128.7, 129.8/129.9, 134.0/134.1, 137.7/137.8, 143.4/146.8, 148.2/148.3, 167.0/171.4 ppm.

(E/Z)-4-Cyclohexyl-1-(4-hydroxybenzaldehyde)thiosemicarbazone (2d)

Prepared according to general procedure 1 from 4-cyclohexylthiosemicarbazide (504 mg, 2.38 mmol) and 4-hydroxybenzaldehyde (291 mg, 2.38 mmol). Recrystallization from Et2O gave a yellow crystalline solid (528 mg, 80%); 1H NMR (400 MHz, [D6]DMSO): δH=1.09–1.88 (m, 10H), 4.13–4.22 (m, 1 H), 6.79–6.81 (m, 2 H), 7.57–7.61 (m, 2 H), 7.84 (d, 1 H), 7.97 (s, 1H), 9.88 (br s, 1 H), 11.19 ppm (s, 1H); 13C NMR (100 MHz, [D6]DMSO): δC=24.8, 25.1, 31.8, 52.4, 115.5, 124.9, 129.0, 142.5, 159.2, 175.3 ppm. Analytical data are consistent with previous findings.[33]

(E/Z)-5-(4-Methoxybenzylideneamino)-1H-benzo[d]imidazol-2-(3H)-one (2e)

Prepared according to general procedure 1 from 5-amino-1H -benzo[d ]imidazol-2(3H)-one (507 mg, 3.40 mmol) and 4-methoxybenzaldehyde (0.41 mL, 3.40 mmol). Recrystallization from toluene gave a yellow crystalline solid (654 mg, 72%); 1H NMR (400 MHz, [D6]DMSO): δH=3.83 (s, 3H), 6.88–7.06 (m, 5 H), 7.85–7.87 (m, 2 H), 8.54 (s, 1H), 10.62 ppm (br s, 2H); 13C NMR (100 MHz, [D6]DMSO): δC=55.3, 100.9, 108.5, 114.1, 114.3, 128.0, 129.2, 130.0, 130.3, 145.0, 155.5, 157.3, 161.5 ppm.

(E/Z)-3-((m-Tolylimino)methyl)quinolin-2-ol (2f)

Prepared according to general procedure 1 from m -toluidine (0.26 mL, 2.40 mmol) and 2-hydroxyquinolin-3-carbaldehyde (415 mg, 2.40 mmol). Recrystallization from toluene gave a yellow crystalline solid (345 mg, 55%); 1H NMR (400 MHz, [D6]DMSO): δH=2.36 (s, 3 H), 7.05–7.10 (m, 3H), 7.22–7.37 (m, 3 H), 7.56–7.61 (m, 1H), 7.88–7.91 (m, 1 H), 8.67 (s, 1 H), 8.78 (s, 1 H), 12.12 ppm (s, 1H); 13C NMR (100 MHz, [D6]DMSO): δC=20.8, 115.1, 118.1, 118.8, 121.2, 122.3, 126.3, 126.9, 129.0, 129.6, 131.8, 137.5, 138.6, 139.7, 151.4, 154.9, 161.4 ppm.

(E/Z)-4-((2-Hydroxy-5-methylphenylimino)methyl)benzene-1,3-diol (2g)

Prepared according to general procedure 1 from 2-amino-4-methylphenol (630 mg, 5.12 mmol) and 2,4-dihydroxybenzaldehyde (707 mg, 5.12 mmol). Recrystallization from toluene gave a yellow crystalline solid (872 mg, 70%); 1H NMR (400 MHz, [D6]DMSO): δH=2.23 (s, 3 H), 6.21–6.22 (m, 1 H), 6.23–6.34 (m, 1H), 6.80–6.88 (m, 2 H), 7.13–7.14 (m, 1 H), 7.34–7.36 (m, 1 H), 8.77 (s, 1 H), 9.46 (s, 1 H), 10.18 (s, 1 H), 14.33 ppm (s, 1H); 13C NMR (100 MHz, [D6]DMSO): δC=20.1, 102.6, 107.4, 112.2, 116.1, 119.3, 127.4, 128.2, 133.9, 134.0, 148.0, 159.8, 162.3, 165.1 ppm.

2-(m-Tolyloxy)acetonitrile (3a)

Prepared according to general procedure 3 from m -cresol (5.01 mL, 47.7 mmol), K2CO3 (13.2 g, 95.4 mmol), chloroacetonitrile (3.00 mL, 47.7 mmol) and KI (238 mg, 1.44 mmol). Evaporation of the solvent in vacuo gave a reddish oil (4.84 g, 69%); 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): δH=2.36 (s, 3 H), 4.73 (s, 2 H), 6.78–6.80 (m, 2H), 6.91 (d, J =7.5 Hz, 1 H), 7.23 ppm (t, J =7.8 Hz, 1H); 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3): δC=21.4, 53.5, 111.7, 115.2, 115.7, 123.9, 129.5, 140.1, 156.5 ppm. Analytical data are consistent with previous findings.[34]

2-(m-Tolylsulfanyl)acetonitrile (3b)

NaH (60% dispersion in mineral oil; 280 mg, 6.99 mmol) was dissolved in DMF (15 mL) and cooled to 0 °C. m -Thiocresol (0.76 mL, 6.35 mmol) was added, and the reaction mixture was stirred for 30 min while it warmed to RT. Chloroacetonitrile (0.4 mL, 6.35 mL) and KI (32 mg, 0.19 mmol) were added, and the reaction mixture was stirred at 60°C for 2 h. The solution was concentrated to a volume of about 5 mL and then diluted with Et2O (100 mL). Aq NaOH (1 m) was added, and the mixture was extracted with Et2O (2×50 mL). Evaporation of the solvent in vacuo gave a reddish oil (798 mg, 77%); 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): δH=2.14 (s, 3H), 4.42 (s, 2 H), 6.79–6.92 (m, 3 H), 7.41–7.43 ppm (m, 1H); 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3): δC=22.0, 22.5, 117.1, 124.9, 126.1, 126.3, 129.1, 136.6, 137.6 ppm.

2-(4-Isopropylphenoxy)acetonitrile (3c)

Prepared according to general procedure 3 from 4-isopropylphenol (1.08 g, 7.95 mmol), K2CO3 (2.20 g, 15.9 mmol), chloroacetonitrile (0.50 mL, 7.95 mmol) and KI (40 mg, 0.24 mmol). Evaporation of the solvent in vacuo gave a reddish oil (975 mg, 70%); 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): δH= 1.25 (d, 6 H), 3.07 (m, 1H), 4.81 (s, 2 H), 6.87–6.92 (m, 2 H), 7.41– 7.45 ppm (m, 2H); 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3): δC=22.1, 30.0, 57.7, 115.0, 127.7, 111.6, 139.1, 154.2 ppm.

2-(5,6,7,8-Tetrahydronaphthalen-2-yloxy)acetonitrile (3d)

Prepared according to general procedure 3 from 2-(5,6,7,8-tetrahydronaphthalen-2-ol (1.18 g, 7.95 mmol), K2CO3 (2.20 g, 15.9 mmol), chloroacetonitrile (0.50 mL, 7.95 mmol) and KI (40 mg, 0.24 mmol). Evaporation of the solvent in vacuo gave a reddish oil (967 mg, 65%); 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): δH=1.69–1.73 (m, 4 H), 2.65–2.70 (m, 4 H), 5.08 (s, 2 H), 6.75–6.80 (m, 2 H), 7.01–7.03 ppm (m, 1H); 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3): δC=23.1, 23.3, 28.5, 29.6, 54.0, 113.1, 115.2, 117.4, 130.5, 131.2, 138.6, 154.6 ppm.

2-(Naphthalen-1-yloxy)acetonitrile (3e)

Prepared according to general procedure 3 from 1-naphthol (1.15 g, 7.95 mmol), K2CO3 (2.20 g, 15.9 mmol), chloroacetonitrile (0.50 mL, 7.95 mmol) and KI (40 mg, 0.24 mmol). Evaporation of the solvent in vacuo gave a reddish oil (946 mg, 65%); 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): δH=4.87 (s, 2 H), 6.81–6.90 (m, 2 H), 7.33–7.51 (m, 3 H), 7.81–7.88 ppm (m, 2H); 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3): δC=54.5, 104.5, 115.3, 120.6, 122.6, 126.7, 126.9, 127.2, 129.8, 132.0, 135.1, 155.5 ppm.

2-(Naphthalen-2-yloxy)acetonitrile (3f)

Prepared according to general procedure 3 from 2-naphthol (1.15 g, 7.95 mmol), K2CO3 (2.20 g, 15.9 mmol), chloroacetonitrile (0.50 mL, 7.95 mmol) and KI (40 mg, 0.24 mmol). Evaporation of the solvent in vacuo gave a reddish oil (976 mg, 67%); 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): δH=4.87 (s, 2 H), 7.18–7.25 (m, 2 H), 7.41–7.53 (m, 2 H), 7.78–7.83 ppm (m, 3H); 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3): δC=53.4, 107.7, 115.1, 118.1, 124.8, 126.9, 127.1, 127.7, 129.8, 130.2, 133.9, 154.4 ppm.

2-(m-Tolyloxy)ethanaminium chloride (4a)

Prepared according to general procedure 4 from 3a (4.82 g, 32.8 mmol) and LiAlH4 (4.10 mL, 16.4 mmol). Washing the precipitate with Et2O (1×5 mL) gave a white crystalline solid (5.53 g, 90%); 1H NMR (400 MHz, D2O): δH=2.30 (s, 3H), 3.39 (t, J =4.8 Hz, 2H), 4.23 (t, J =4.8 Hz, 2 H,), 6.81–6.91 (m, 3H), 7.23–7.27 ppm (m, 1H); 13C NMR (100 MHz, D2O): δC=20.5, 39.0, 63.8, 111.6, 115.3, 122.6, 129.8, 140.6, 155.7 ppm.

2-(m-Tolylsulfanyl)ethanaminium chloride (4b)

Prepared according to general procedure 4 from 3b (758 mg, 4.64 mmol) and LiAlH4 (0.58 mL, 2.32 mmol). Washing the precipitate with Et2O (1×5 mL) gave a white crystalline solid (823 mg, 87%); 1H NMR (400 MHz, D2O): δH=2.39 (s, 3 H), 3.24 (t, J =6.4 Hz, 2H), 3.31 (t, J = 6.2 Hz, 2 H), 7.24–7.40 ppm (m, 4H); 13C NMR (100 MHz, D2O): δC= 20.3, 30.6, 38.1, 127.4, 128.3, 129.4, 130.8, 132.6, 134.0 ppm.

2-(4-Isopropylphenoxy)ethanaminium chloride (4c)

Prepared according to general procedure 4 from 3c (960 mg, 5.48 mmol) and LiAlH4 (0.69 mL, 2.74 mmol). Washing the precipitate with Et2O (1×5 mL) gave a white crystalline solid (959 mg, 81%); 1H NMR (400 MHz, D2O): δH=1.16 (d, J =6.2 Hz, 6 H), 3.12–3.14 (m, 1 H), 3.47 (t, J =5.7 Hz, 2 H), 4.76 (t, J =5.7 Hz, 2 H,), 6.94–6.99 (m, 2 H), 7.53–7.59 ppm (m, 2H); 13C NMR (100 MHz, D2O): δC=23.1, 32.5, 41.3, 64.2, 114.6, 125.9, 140.6, 155.2 ppm.

2-(5,6,7,8-Tetrahydronaphthalen-2-yloxy)ethanaminium chloride (4d)

Prepared according to general procedure 4 from 3d (944 mg, 5.04 mmol) and LiAlH4 (0.63 mL, 2.52 mmol). Washing the precipitate with Et2O (1×5 mL) gave a white crystalline solid (1.01 g, 88%); 1H NMR (400 MHz, D2O): δH=1.77–1.80 (m, 4 H), 2.72–2.77 (m, 4H), 3.46 (t, J =5.7 Hz, 2H), 4.28 (t, J =5.7 Hz, 2H,), 6.84–6.87 (m, 2H), 7.13–7.15 ppm (m, 1H); 13C NMR (100 MHz, D2O): δC=22.6, 22.9, 28.0, 29.1, 39.0, 64.1, 112.6, 114.6, 130.3, 130.9, 139.1, 155.4 ppm.

2-(Naphthalen-1-yloxy)ethanaminium chloride (4e)

Prepared according to general procedure 4 from 3e (918 mg, 5.01 mmol) and LiAlH4 (0.63 mL, 2.50 mmol). Washing the precipitate with Et2O (1×5 mL) gave awhite crystalline solid (930 mg, 83%); 1H NMR (400 MHz, D2O): δH=3.34 (t, J =5.2 Hz, 2H), 4.14 (t, J =5.1 Hz, 2H,), 6.81–6.89 (m, 2 H), 7.31–7.50 (m, 3 H), 7.80–7.86 ppm (m, 2H); 13C NMR (100 MHz, D2O): δC=41.3, 69.9, 106.7, 118.6, 118.8, 120.3, 123.7, 125.6, 126.0, 127.2, 134.4, 153.8 ppm.

2-(Naphthalen-2-yloxy)ethanamine (4f)

3f (8.73 g, 47.7 mmol) was dissolved in Et2O, and the solution was cooled to 0°C. A 4 m solution of LiAlH4 in Et2O (6.00 mL, 23.9 mmol) was added, and the reaction mixture was stirred for 2 h at RT. The reaction mixture was again cooled to 0°C, and water was added dropwise. The organic layer was separated and dried over MgSO4. The solvent was evaporated to give a reddish solid (4.84 mg, 69%); 1H NMR (400 MHz, D2O): δH=1.48 (br s, 2H), 3.14 (t, J =5.2 Hz, 2 H), 4.10 (t, J =5.2 Hz, 2 H,), 7.14–7.19 (m, 2 H), 7.32–7.46 (m, 2H), 7.72–7.78 ppm (m, 3H); 13C NMR (100 MHz, D2O): δC=41.6, 70.2, 106.7, 118.8, 123.6, 126.3, 126.7, 127.6, 129.0, 129.4, 134.5, 156.8 ppm.

2-(2-Phenoxyethylcarbamoyl)phenyl acetate (5a)

Prepared according to general procedure 5a from 2-phenoxyethanamine (0.19 mL, 1.46 mmol), acetyl salicylic acid chloride (290 mg, 1.46 mmol) and Et3N (0.20 mL, 1.46 mmol). Recrystallization from toluene gave a white crystalline solid (359 mg, 82%); 1H NMR (400 MHz, [D6]DMSO): δH=2.18 (s, 3 H), 3.57 (ps q, J =5.7 Hz, 2 H), 4.07 (t, J =5.8 Hz, 2H), 6.92–7.00 (m, 3 H), 7.17–7.19 (m, 1H), 7.28–7.25 (m, 3 H), 7.45–7.59 (m, 2H), 8.48 ppm (t, J =5.4 Hz, 1H); 13C NMR (100 MHz, [D6]DMSO): δC=20.7, 38.6, 65.8, 114.4, 120.6, 123.2, 125.7, 129.0, 129.0, 129.5, 131.2, 147.8, 158.3, 165.4, 168.7 ppm.

2-(2-(Naphthalen-2-yloxy)ethylcarbamoyl)phenyl acetate (5b)

Prepared according to general procedure 5a from 2-phenoxyethanamine (0.19 mL, 1.46 mmol), acetyl salicylic acid chloride (290 mg, 1.46 mmol) and Et3N (0.20 mL, 1.46 mmol). Recrystallization from toluene gave a white crystalline solid (359 mg, 82%); 1H NMR (400 MHz, [D6]DMSO): δH=2.19 (s, 3 H), 3.67 (ps q, J =5.63 Hz, 2H), 4.22 (t, J =5.7 Hz, 2H), 8.50 (t, J =5.4 Hz, 1 H), 7.17–7.19 (m, 2 H), 7.31–7.53 (m, 5 H), 7.60–7.63 (m, 1 H), 7.80–7.84 ppm (m, 3H); 13C NMR (100 MHz, [D6]DMSO): δC=20.6, 38.6, 66.1, 106.9, 118.6, 123.2, 123.5, 125.7, 126.3, 126.6, 127.4, 127.9, 128.5, 129.0, 129.2, 131.2, 133.6, 147.9, 156.2, 165.4, 168.7 ppm.

2-(2-(m-Tolyloxy)ethylcarbamoyl)phenyl acetate (5c)

Prepared according to general procedure 5b from 2-(m -tolyloxy)ethanaminium chloride (150 mg, 0.79 mmol), acetylsalicylic acid chloride (143 mg, 0.79 mmol) and Et3N (0.22 mL, 1.58 mmol). Purification by chromatography (CH2Cl2/MeOH, 19:1) gave a white crystalline solid (221 mg, 89%); mp: 68°C; 1H NMR (400 MHz, [D6]DMSO): δH=2.18 (s, 3 H), 2.27 (s, 3H), 3.56 (ps q, J =5.7 Hz, 2H), 4.05 (t, J =5.8 Hz, 2 H), 6.73–6.78 (m, 3 H), 7.14–7.19 (m, 2 H), 7.31–7.35 (m, 1 H), 7.49–7.53 (m, 1 H), 7.57–7.59 (m, 1H), 8.46 ppm (t, J =5.7 Hz, 1H); 13C NMR (100 MHz, [D6]DMSO): δC=20.6, 21.0, 38.7, 65.8, 111.4, 115.1, 121.3, 123.1, 125.7, 128.9, 129.0, 129.2, 131.2, 138.9, 147.9, 158.4, 165.4, 168.7 ppm; IR (ATR): ṽ =3331, 3079, 2990, 2925, 1750, 1641, 1538, 1264, 1198, 1174, 658 cm−1; MS (ESI): m/z (%): 314 [M+H]+ (36), 336 [M+Na]+ (100), 649 [2M+Na]+ (23); HRMS (EI): m/z calcd for [M]+: 313.1314, found: 313.1298.

2-Hydroxy-N-(2-phenoxyethyl)benzamide (5d)

Prepared according to general procedure 6 from 5a (410 mg, 1.31 mmol), glacial AcOH (25.0 mL, 0.44 mol) and 32% aq HCl solution (1.0 mL, 10.3 mmol). Recrystallization from toluene gave a white crystalline solid (283 mg, 94%); mp: 120°C; 1H NMR (400 MHz, [D6]DMSO): δH=3.69 (ps q, J =5.7 Hz, 2 H), 4.13 (t, J =5.8 Hz, 2 H), 6.87–6.98 (m, 5 H), 7.27–7.31 (m, 2H), 7.38–7.42 (m, 1 H), 7.88–7.90 (m, 1H), 9.03 (t, J =5.3 Hz, 1H), 12.46 ppm (s, 1H); 13C NMR (100 MHz, [D6]DMSO): δC=38.5, 65.6, 114.4, 115.2, 117.2, 118.5, 120.6, 127.9, 129.4, 133.6, 158.2, 159.6, 168.8 ppm; IR (ATR): ṽ =3389, 2949, 1638, 1593, 1543, 1488, 1242, 1231, 752 cm−1; MS (EI, 70 eV): m/z (%): 121 (85), 164 (100), 257 [M]+ (15); HRMS (EI): m/z calcd for [M]+: 257.1052, found: 257.1091.

N-(2-(m-Tolyloxy)ethyl)benzamide (5e)

Prepared according to general procedure 5b from benzoic acid chloride (0.16 mL, 1.34 mmol), 2-(m -tolyloxy)ethanaminium chloride (252 mg, 1.34 mmol) and Et3N (0.37 mL, 2.68 mmol). Purification by chromatography (CH2Cl2/MeOH, 19:1) gave a white crystalline solid (285 mg, 83%); mp: 59°C; 1H NMR (400 MHz, [D6]DMSO): δH=2.26 (s, 3 H), 3.62 (ps q, J =5.9 Hz, 2 H), 4.10 (t, J =6.0 Hz, 2 H), 6.73–6.78 (m, 3 H), 7.31–7.17 (m, 1 H), 7.44–7.54 (m, 3 H), 7.857.87 (m, 2 H), 8.67 ppm (t, J =5.3 Hz, 1H); 13C NMR (100 MHz, [D6]DMSO): δC= 21.0, 38.9, 65.7, 111.4, 115.0, 121.3, 127.1, 128.2, 129.2, 131.2, 134.2, 138.9, 158.4, 166.4 ppm; IR (ATR): ṽ =3309, 3038, 2934, 2879, 1633, 1534, 1487, 1309, 1261, 1154, 1064, 768, 688 cm−1; MS (EI, 70 eV): m/z (%): 105 (59), 148 (100), 255 [M]+ (6); HRMS (EI): m/z calcd for [M]+: 255.1259, found: 255.1293.

3-Hydroxy-N-(2-(m-tolyloxy)ethyl)-2-naphthamide (5f)

Prepared according to general procedures 7 and 5b from 3-hydroxy-2-naphthoic acid (219 mg, 1.16 mmol), oxalyl chloride (0.15 mL, 1.74 mmol), 2-(m -tolyloxy)ethanaminium chloride (203 mg, 1.16 mmol) and Et3N (0.32 mL, 2.32 mmol). Purification by chromatography (CH2Cl2/MeOH, 19:1) gave a white crystalline solid (183 mg, 49%); mp: 143°C; 1H NMR (400 MHz, [D6]DMSO): δH= 2.26 (s, 3H), 3.74 (ps q, J =5.6 Hz, 2 H), 4.16 (t, J =5.7 Hz, 2 H), 6.74–6.81 (m, 3 H), 7.14–7.18 (m, 1H), 7.26 (s, 1 H), 7.32–7.36 (m, 1H), 7.48–7.51 (m, 1 H), 7.73–7.75 (m, 1 H), 7.85–7.87 (m, 1 H), 8.54 (s, 1 H), 9.22 (t, J =5.4 Hz, 1H), 11.93 ppm (s, 1H); 13C NMR (100 MHz, [D6]DMSO): δC=20.9, 38.7, 65.7, 110.6, 111.4, 115.1, 118.6, 121.4, 123.6, 125.6, 126.5, 128.1, 128.6, 129.1, 129.8, 135.9, 138.9, 154.9, 158.3, 167.9 ppm; IR (ATR): ṽ =3379, 2943, 1651, 1580, 1542, 1260, 1231, 1169, 777, 754 cm−1; MS (EI, 70 eV): m/z (%): 171 (49), 214 (100), 321 [M]+ (38); HRMS (EI): m/z calcd for [M]+: 321.1365, found: 321.1393.

1-Hydroxy-N-(2-(m-tolyloxy)ethyl)-2-naphthamide (5g)

Prepared according to general procedures 7 and 5b from 1-hydroxy-2-naphthoic acid (426 mg, 2.26 mmol), oxalyl chloride (0.29 mL, 3.39 mmol), 2-(m -tolyloxy)ethanaminium chloride (424 mg, 2.26 mmol) and Et3N (0.63 mL, 4.52 mmol). Purification by chromatography (CH2Cl2/MeOH, 19:1) gave a white crystalline solid (4.52 mg, 41%); mp: 92°C; 1H NMR (400 MHz, [D6]DMSO): δH=2.26 (s, 3 H), 3.73 (ps q, J =5.7 Hz, 2 H), 4.16 (t, J =5.8 Hz, 2 H), 6.73–6.80 (m, 3H), 7.13–7.17 (m, 1 H), 7.37–7.40 (m, 1H), 7.53–7.67 (m, 2 H), 7.86–7.92 (m, 2 H), 8.26–8.28 (m, 1H), 9.20 (t, J =5.4 Hz, 1 H), 14.53 ppm (s, 1H); 13C NMR (100 MHz, [D6]DMSO): δC=21.0, 38.8, 65.4, 106.8, 111.4, 115.1, 117.5, 121.4, 122.5, 122.9, 124.6, 125.7, 127.4, 128.8, 129.2, 135.7, 138.9, 158.3, 159.6, 170.8 ppm; IR (ATR): ṽ =3452, 3054, 2942, 1593, 1536, 1258, 783, 760 cm−1; MS (FAB): m/z (%): 170 (64), 214 (100), 321 [M]+ (62); HRMS (EI): m/z calcd for [M]+: 321.1365, found: 321.1394.

2-Hydroxy-N-(2-(naphthalen-2-yloxy)ethyl)benzamide (5h)

Prepared according to general procedures 7 and 5b from salicylic acid (310 mg, 2.24 mmol), oxalyl chloride (0.29 mL, 3.36 mmol), 2-(naphthalen-2-yloxy)ethanamine (420 mg, 2.24 mmol) and Et3N (0.31 mL, 2.24 mmol). Purification by chromatography (CH2Cl2/MeOH, 19:1) gave a white crystalline solid (393 mg, 57%); mp: 190°C; 1H NMR (400 MHz, [D6]DMSO): δH=3.77 (ps q, J =5.7 Hz, 2 H), 4.28 (t, J = 5.8 Hz, 2 H), 6.88–6.93 (m, 2H), 7.18–7.20 (m, 1 H), 7.32–7.47 (m, 4 H), 7.79–7.91 (m, 4H), 9.06 (t, J =5.3 Hz, 1 H), 12.43 ppm (s, 1H); 13C NMR (100 MHz, [D6]DMSO): δC=38.6, 65.9, 106.8, 115.3, 117.3, 118.5, 118.6, 123.6, 126.3, 126.6, 127.4, 127.9, 128.5, 129.3, 133.7, 134.2, 156.1, 159.7, 168.9 ppm; IR (ATR): ṽ =3386, 1638, 1592, 1550, 1337, 1256, 1215, 1177, 836, 750 cm−1; MS (ESI): m/z (%): 208 (33), 308 [M+H]+ (100), 330 [M+Na]+ (24); HRMS (EI): m/z calcd for [M]+: 307.1208, found: 307.1196.

2-Hydroxy-N-(2-(naphthalen-1-yloxy)ethyl)benzamide (5i)

Prepared according to general procedures 7 and 5b from salicylic acid (297 mg, 2.15 mmol), oxalyl chloride (0.28 mL, 3.23 mmol), 2-(m -tolyloxy) ethanaminium chloride (481 mg, 2.15 mmol) and Et3N (0.60 mL, 4.30 mmol). Purification by chromatography (CH2Cl2/MeOH, 19:1) gave a white crystalline solid (350 mg, 53%); mp: 131°C; 1H NMR (400 MHz, [D6]DMSO): δH=3.86 (ps q, J =5.6 Hz, 2 H), 4.32 (t, J =5.5 Hz, 2H), 6.87–7.01 (m, 3H), 7.37–7.53 (m, 5H), 7.84–7.91 (m, 2 H), 8.24–8.26 (m, 1H), 9.10 (t, J =5.5 Hz, 1 H), 12.44 ppm (s, 1H); 13C NMR (100 MHz, [D6]DMSO): δC=38.0, 66.3, 105.1, 115.4, 117.3, 118.6, 120.0, 121.6, 124.8, 125.1, 126.1, 126.4, 127.3, 127.9, 133.6, 133.9, 153.8, 159.7, 168.9 ppm; IR (ATR): ṽ = 3426, 1638, 1593, 1536, 1484, 1270, 1240, 1101, 752 cm−1; MS (ESI): m/z (%): 308 [M+H]+ (100), 325 [M+NH4]+ (32), 330 [M+Na]+ (40); HRMS (EI): m/z calcd for [M]+: 307.1208, found: 307.1180.

2-Chloro-N-(2-(m-tolyloxy)ethyl)benzamide (6a)

Prepared according to general procedure 5a from 2-(m -tolyloxy)ethanaminium chloride (202 mg, 1.08 mmol), 2-chlorobenzoic acid chloride (0.14 mL, 1.08 mmol) and Et3N (0.30 mL, 2.16 mmol). Recrystallization from toluene gave a white crystalline solid (278 mg, 89%); mp: 83 °C; 1H NMR (400 MHz, [D6]DMSO): δH=2.27 (s, 3 H), 3.59 (ps q, J =5.7 Hz, 2 H), 4.07 (t, J =5.8 Hz, 2H), 6.74–6.78 (m, 3 H), 7.14–7.18 (m, 1 H), 3.36–7.50 (m, 4H), 8.68 ppm (t, J =5.4 Hz, 1H); 13C NMR (100 MHz, [D6]DMSO): δC=21.0, 38.6, 65.7, 111.5, 115.1, 121.3, 126.9, 128.7, 129.1, 129.5, 129.8, 130.6, 136.7, 138.9, 158.4, 166.5 ppm; IR (ATR): ṽ =3248, 3061, 2931, 1640, 1561, 1292, 1257, 1159, 1058, 692 cm−1; MS (EI, 70 eV): m/z (%): 139 (57), 182 (100), 289 [M]+ (7); HRMS (EI): m/z calcd for [M]+: 289.0870, found: 289.0911.

(R,S)-N,N-(2-(m-Tolyloxy))-pentamethylene-2-chlorobenzamide (6b)

A solution of (R,S)-3-(p-tolyloxy)piperidine (202 mg, 1.11 mmol) and 2-chlorobenzoic acid chloride (0.14 mL, 1.11 mmol) in pyridine was heated at reflux for 3 h. The solvent was removed, and the residue was purified by chromatography (CH2Cl2/MeOH, 19:1) to give a white crystalline solid (320 mg, 87%); mp: 91°C; 1H NMR (400 MHz, [D6]DMSO): δH=1.51–1.71 (m, 2 H), 1.86–2.04 (m, 2 H), 2.26 (s, 3H), 3.09–3.53 (m, 3 H), 3.97–4.05 (m, 1 H), 4.60–4.65 (m, 1 H), 6.73–6.80 (m, 3H), 7.13–7.17 (m, 1H), 7.37–7.54 ppm (m, 4H); 13C NMR (100 MHz, [D6]DMSO): δC=21.0, 30.0, 30.7, 38.0, 43.3, 71.2, 112.7, 116.5, 121.5, 127.5, 127.6, 127.7, 129.0, 129.2, 129.3, 129.4, 130.3, 135.9, 139.0, 156.7, 165.3 ppm; IR (ATR): ṽ =2954, 2861, 1627, 1584, 1440, 1255, 1150, 1061, 765, 739 cm−1; MS (EI, 70 eV): m/z (%): 330 [M+H]+ (100), 347 [M+NH4]+ (33); HRMS (EI): m/z calcd for [M]+: 330.1261, found: 330.1241.

N,N-(2-(m-Tolyloxy))trimethylene-2-chlorobenzamide (6c)

A solution of 3 m -tolyloxy-azetidine (205 mg, 1.26 mmol) and 2-chlorobenzoic acid chloride (0.16 mL, 1.26 mmol) in pyridine was heated at reflux for 3 h. The solvent was removed, and the residue was purified by chromatography (CH2Cl2/MeOH, 19:1) to give a colorless resin (316 mg, 83%); 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): δH=2.31 (s, 3H), 4.00–4.04 (m, 1 H), 4.24–4.31 (m, 2H), 4.56–4.61 (m, 1H), 4.97 (tt, J =6.5, 4.2 Hz, 1 H), 6.51–6.56 (m, 2 H), 6.80–6.81 (m, 1H), 7.13–7.41 ppm (m, 5H); 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3): δC=21.4, 55.5, 57.9, 65.3, 111.2, 115.3, 122.6, 127.0, 128.4, 129.4, 129.8, 130.5, 130.8, 133.9, 139.9, 156.2, 167.9 ppm; IR (ATR): ṽ =3057, 2942, 2873, 1638, 1584, 1422, 1256, 1180, 1156, 771, 748, 691 cm−1; MS (ESI): m/z (%): 302 [M (35 Cl)+H]+ (100), 319 [M+NH4]+ (95); HRMS (ESI): m/z calcd for [M+H]+: 302.0948, found: 302.0925

2-Chloro-N-(2-(phenylsulfanyl)ethyl)benzamide (6d)

Prepared according to general procedure 5b from 2-(m -tolylsulfanyl)ethanaminium chloride (198 mg, 0.97 mmol), 2-chlorobenzoic acid chloride (0.12 mL, 0.97 mmol) and Et3N (0.27 mL, 1.93 mmol). Purification by chromatography (CH2Cl2/MeOH, 19:1) gave a white crystalline solid (251 mg, 85%); mp: 51 °C; 1H NMR (400 MHz, [D6]DMSO): δH=2.29 (s, 3 H), 3.11 (t, J =8.0, 6.3 Hz, 2H), 3.42 (td, J =7.5, 6.0 Hz, 2 H), 7.01–7.03 (m, 1 H), 7.19–7.25 (m, 3 H), 7.38–7.51 (m, 4 H), 8.66 ppm (t, J =6.0 Hz, 1H); 13C NMR (100 MHz, [D6]DMSO): δC=20.8, 31.2, 38.6, 125.2, 126.5, 127.0, 128.6, 128.8, 128.9, 129.5, 129.8, 130.7, 135.3, 136.7, 138.4, 166.3 ppm; IR (ATR): ṽ =3253, 3084, 2913, 1639, 1555, 1427, 1314, 1291, 755, 683 cm−1; MS (ESI): m/z (%): 306 [M+H]+ (35), 323 [M+NH4]+ (100), 328 [M+Na]+ (34); HRMS (ESI): m/z calcd for [M+H]+: 306.0719, found: 306.0686.

2-Chloro-N-(2-(4-isopropylphenoxy)ethyl)benzamide (6e)

Prepared according to general procedure 5b from 2-(4-isopropylphenoxy) ethanaminium chloride (194 mg, 0.90 mmol), 2-chlorobenzoic acid chloride (0.11 mL, 0.90 mmol) and Et3N (0.25 mL, 1.80 mmol). Purification by chromatography (CH2Cl2/MeOH, 19:1) gave a white crystalline solid (240 mg, 84%); mp: 46 °C; 1H NMR (400 MHz, [D6]DMSO): δH=1.17 (d, J =6.9 Hz, 6 H), 2.78–2.88 (m, 1H), 3.59 (ps q, J =5.7 Hz, 2 H), 4.07 (t, J =5.8 Hz, 2H), 6.87–6.89 (m, 2 H), 7.14–7.16 (m, 2 H), 7.35–7.50 (m, 4H), 8.66 ppm (t, J =5.4 Hz, 1H); 13C NMR (100 MHz, [D6]DMSO): δC=24.0, 32.4, 38.6, 65.9, 114.3, 126.9, 127.0, 128.7, 129.4, 129.8, 130.6, 136.7, 140.5, 156.4, 166.4 ppm; IR (ATR): ṽ =3261, 2959, 2869, 1637, 1551, 1510, 1305, 1244, 1042, 828, 700, 543 cm−1; MS (ESI): m/z (%): 318 [M+H]+ (51), 335 [M+NH4]+ (100), 342 [M+Na]+ (37); HRMS (ESI): m/z calcd for [M+H]+: 318.1261, found: 318.1243.

2-Chloro-N-(2-(5,6,7,8-tetrahydronaphthalen-2-yloxy)ethyl)benzamide (6f)

Prepared according to general procedure 5b from 2-(5,6,7,8-tetrahydronaphthalen-2-yloxy)ethanamime (196 mg, 0.86 mmol), 2-chlorobenzoic acid chloride (0.11 mL, 0.86 mmol) and Et3N (0.24 mL, 1.72 mmol). Purification by chromatography (CH2Cl2/MeOH, 19:1) gave a white crystalline solid (252 mg, 88%); mp: 65°C; 1H NMR (400 MHz, [D6]DMSO): δH=1.68–1.72 (m, 4 H), 2.63–2.68 (m, 4H), 3.56 (ps q, J =5.8 Hz, 2H), 4.04 (t, J =5.8 Hz, 2 H), 6.64–6.69 (m, 2 H), 6.93–6.96 (m, 1 H), 7.37–7.49 (m, 4H), 8.60 ppm (t, J =5.4 Hz, 1H); 13C NMR (100 MHz, [D6]DMSO): δC=22.6, 22.9, 27.9, 29.0, 38.7, 65.8, 112.4, 114.2, 127.0, 128.6, 128.8, 129.5, 129.7, 129.8, 130.7, 136.8, 137.5, 156.1, 166.5 ppm; IR (ATR): ṽ =3336, 2943, 2926, 1651, 1531, 1502, 1264, 1059, 735, 647 cm−1; MS (ESI): m/z (%): 330 [M+H]+(52), 347 [M+NH4]+(100), 352 [M+Na]+(59); HRMS (ESI): m/z calcd for [M+H]+: 330.1261, found: 330.1234.

2-Chloro-N-(2-(naphthalen-2-yloxy)ethyl)benzamide (6g)

Prepared according to general procedure 5a from 2-(naphthalen-2-yloxy)ethanaminium chloride (212 mg, 1.13 mmol), 2-chlorobenzoic acid chloride (0.14 mL, 1.13 mmol) and Et3N (0.16 mL, 1.13 mmol). Recrystallization from toluene/pentane (1:20) gave a white crystalline solid (244 mg, 66%); mp: 116°C; 1H NMR (400 MHz, [D6]DMSO): δH=3.69 (ps q, J =5.7 Hz, 2H), 4.24 (t, J =5.7 Hz, 2 H), 7.17–7.20 (m, 1H), 7.33–7.39 (m, 3H), 7.42–7.50 (m, 4 H), 7.80–7.85 (m, 3H), 8.70 ppm (t, J =5.3 Hz, 1H); 13C NMR (100 MHz, [D6]DMSO): δC=38.6, 66.0, 106.7, 118.7, 123.5, 126.3, 126.6, 127.0, 127.4, 128.4, 128.8, 129.2, 129.5, 129.8, 130.7, 134.2, 136.8, 156.3, 166.6 ppm; IR (ATR): ṽ =3274, 1645, 1547, 1258, 1118, 815, 747, 733, 474 cm−1; MS (ESI): m/z (%): 326 [M+H]+(22), 343 [M+NH4]+(100); HRMS (ESI): m/z calcd for [M+H]+: 326.0948, found: 326.0928.

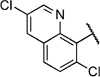

2-Chloro-N-(2-(7-chloroquinolin-4-ylamino)ethyl)benzamide (6h)

Prepared according to general procedure 5a from N’-[7-chloroquinolin-4-yl)ethane-1,2-diamine (194 mg, 0.83 mmol), 2-chlorobenzoic acid chloride (0.11 mL, 0.83 mmol) and Et3N (0.12 mL, 0.83 mmol). Recrystallization from toluene gave a white crystalline solid (268 mg, 89%); mp: 213°C; 1H NMR (400 MHz, [D6]DMSO): δH=3.37 (s, 1H), 3.48–3.55 (m, 4H), 6.60–6.62 (m, 1H), 7.37–7.50 (m, 5 H), 7.79–80 (m, 1H), 8.19–8.21 (m, 1 H), 8.42–8.44 (m, 1 H), 8.64 ppm (t, J =5.0 Hz, 1H); 13C NMR (100 MHz, [D6]DMSO): δC=37.7, 41.8, 98.6, 117.3, 123.8, 124.1, 127.0, 127.4, 128.8, 129.5, 129.8, 130.7, 133.3, 136.6, 148.9, 149.9, 151.8, 166.7 ppm; IR (ATR): ṽ = 3251, 1639, 1579, 1536, 1418, 1314, 1229, 810, 749, 688 cm−1; MS (ESI): m/z (%): 360 [M+H]+(100); HRMS (ESI): m/z calcd for [M+H]+: 360.0670, found: 360.0705.

2-Fluoro-N-(2-(m-tolyloxy)ethyl)benzamide (6i)

Prepared according to general procedure 5b from 2-(m -tolyloxy)ethanaminium chloride (191 mg, 1.02 mmol), 2-fluorobenzoic acid chloride (0.12 mL, 1.02 mmol) and Et3N (0.28 mL, 2.04 mmol). Purification by chromatography (CH2Cl2/MeOH, 19:1) gave a white crystalline solid (222 mg, 79); mp: 37 °C; 1H NMR (400 MHz, [D6]DMSO): δH=2.27 (s, 3 H), 3.63 (ps q, J =5.8 Hz, 2H), 4.09 (t, J =5.9 Hz, 2 H), 6.74–6.79 (m, 3 H), 7.14–7.18 (m, 1 H), 7.25–7.30 (m, 2 H), 7.50–7.65 (m, 2 H), 8.46 ppm (t, J =6.1 Hz, 1H); 13C NMR (100 MHz, [D6]DMSO): δC=21.0, 38.8, 65.6, 111.5, 115.1, 116.0 (d, JC–F=22 Hz), 121.4, 123.8 (d, JC–F=14 Hz), 124.4 (d, JC–F==3 Hz), 129.6, 130.0 (d, JC–F=3 Hz), 132.3 (d, JC–F=9 Hz), 138.9, 158.4, 159.1 (d, JC–F=249 Hz), 164.5 ppm; IR (ATR): ṽ =3374, 2924, 1644, 1523, 1480, 1261, 1166, 1158, 788, 757, 516 cm−1; MS (ESI): m/z (%): 274 [M+H]+(68), 291 [M+NH4]+ (100), 296.14 [M+Na]+(49); HRMS (ESI): m/z calcd for [M+Na]+: 296.1063, found: 296.1102.

N-(2-(m-Tolyloxy)ethyl)-2-(trifluoromethyl)benzamide (6j)

Prepared according to general procedures 7 and 5b from 2-trifluoromethylbenzoic acid (199 mg, 1.05 mmol), oxalyl chloride (0.13 mL, 1.57 mmol), 2-(m -tolyloxy)ethanaminium chloride (196 mg, 1.05 mmol) and Et3N (0.29 mL, 2.10 mmol). Purification by chromatography (CH2Cl2/MeOH, 19:1) gave a white crystalline solid (301 mg, 89%); mp: 75°C; 1H NMR (400 MHz, [D6]DMSO): δH=2.28 (s, 3 H), 3.59 (ps q, J =5.7 Hz, 2 H), 4.06 (t, J =5.7 Hz, 2 H), 6.73–6.77 (m, 3H), 7.15–7.19 (m, 1 H), 7.48–7.50 (m, 1H), 7.62–7.78 (m, 3 H), 8.72 ppm (t, J =5.4 Hz, 1H); 13C NMR (100 MHz, [D6]DMSO): δC=21.0, 38.7, 65.6, 111.4, 115.0, 121.3, 123.6 (q, JC–F=−270 Hz), 125.8 (q, JC–F=−31 Hz), 128.4, 129.2, 129.6, 132.3, 136.3, 138.9, 158.4, 167.3 ppm; IR (ATR): ṽ =3277, 2942, 1638, 1553, 1313, 1267, 1170, 1107, 1031, 779 cm−1; MS (ESI): m/z (%): 324 [M+H]+(15), 341 [M+NH4]+(100), 346 [M+Na]+(18); HRMS (ESI): m/z calcd for [M+Na]+: 346.1031, found: 346.1030.

2-Methoxy-N-(2-(m-tolyloxy)ethyl)benzamide (6k)

Prepared according to general procedures 7 and 5b from 2-methoxybenzoic acid (207 mg, 1.36 mmol), oxalyl chloride (0.18 mL, 2.04 mmol), 2-(m -tolyloxy)ethanaminium chloride (256 mg, 1.36 mmol) and Et3N (0.38 mL, 2.72 mmol). Purification by chromatography (CH2Cl2/MeOH, 19:1) gave a colorless resin (315 mg, 81%); 1H NMR (400 MHz, [D6]DMSO): δH=2.33 (s, 3 H), 3.93 (s, 3 H), 3.88 (ps q, J = 5.5 Hz, 2 H), 4.15 (t, J =5.2 Hz, 2 H), 6.73–6.80 (m, 3H), 6.95–6.97 (m, 1 H), 7.05–7.20 (m, 2 H), 7.42–7.48 (m, 1 H), 8.21–8.23 (m, 1 H), 8.36 ppm (br s, 1H); 13C NMR (100 MHz, [D6]DMSO): δC=21.5, 39.2, 55.9, 66.7, 111.3, 111.4, 115.2, 121.2, 121.3, 121.8, 129.3, 132.2, 132.8, 139.6, 157.5, 158.6, 165.4 ppm; IR (ATR): ṽ =3400, 2944, 1650, 1599, 1531, 1484, 1292, 1239, 1159, 758 cm−1; MS (ESI): m/z (%): 286 [M+H]+(100), 308 [M+Na]+(22); HRMS (ESI): m/z calcd for [M+Na]+: 308.1263, found: 308.1291.

3-Chloro-N-(2-(m-tolyloxy)ethyl)benzamide (6l)

Prepared according to general procedures 7 and 5b from 3-chlorobenzoic acid (202 mg, 1.29 mmol), oxalyl chloride (0.17 mL, 1.93 mmol), 2-(m -tolyloxy) ethanaminium chloride (242 mg, 1.29 mmol) and Et3N (0.36 mL, 2.58 mmol). Purification by chromatography (CH2Cl2/MeOH, 19:1) gave a white solid (306 mg, 82%); mp: 45°C; 1H NMR (400 MHz, [D6]DMSO): δH=2.26 (s, 3 H), 3.63 (ps q, J =5.8 Hz, 2 H), 4.10 (t, J =5.9 Hz, 2H), 6.73–6.78 (m, 3 H), 7.13–7.17 (m, 1H), 7.48–7.60 (m, 2 H), 7.82–7.91 (m, 2H), 8.80 ppm (t, J =5.3 Hz, 1H); 13C NMR (100 MHz, [D6]DMSO): δC=21.0, 39.0, 65.6, 111.4, 115.0, 121.3, 125.9, 127.0, 129.2, 130.3, 131.0, 133.1, 136.2, 138.9, 158.3, 165.0 ppm; IR (ATR): ṽ =3280, 3054, 2939, 1633, 1543, 1261, 1172, 1063, 779, 689 cm−1; MS (ESI): m/z (%): 290 [M+H]+(50), 307 [M+NH4]+(100); HRMS (ESI): m/z calcd for [M+Na]+: 312.0767, found: 312.0795.

2-Chloro-4-methoxy-N-(2-(m-tolyloxy)ethyl)benzamide (6m)

Prepared according to general procedures 7 and 5b from 2-chloro-4-methoxybenzoic acid (204 mg, 1.09 mmol), oxalyl chloride (0.14 mL, 1.64 mmol), 2-(m -tolyloxy)ethanaminium chloride (205 mg, 1.09 mmol) and Et3N (0.30 mL, 2.18 mmol). Purification by chromatography (CH2Cl2/MeOH, 19:1) gave a white solid (203 mg, 58%); mp: 65°C; 1H NMR (400 MHz, [D6]DMSO): δH=2.25 (s, 3 H), 3.54 (ps q, J =5.8 Hz, 2 H), 3.77 (s, 3 H), 4.04 (t, J =5.9 Hz, 2 H), 6.71–6.75 (m, 3 H), 6.90–7.02 (m, 2 H), 7.11–7.15 (m, 1H), 7.33–7.35 (m, 1 H), 8.44 ppm (t, J =5.5 Hz, 1H); 13C NMR (100 MHz, [D6]DMSO): δC=21.0, 38.7, 55.6, 65.7, 111.4, 112.7, 114.8, 115.1, 121.3, 128.8, 129.1, 130.0, 131.1, 138.8, 158.4, 160.3, 166.2 ppm; IR (ATR): ṽ = 3343, 2958, 1643, 1601, 1490, 1265, 1237, 1169, 1024, 789 cm−1; MS (ESI): m/z (%): 320 [M+H]+(100), 342 [M+Na]+(31); HRMS (ESI): m/z calcd for [M+H]+: 320.1054, found: 320.1077.

2-Chloro-4,5-dimethoxy-N-(2-(m-tolyloxy)ethyl)benzamide (6n)

Prepared according to general procedures 7 and 5a from 2-chloro-4,5-dimethoxybenzoic acid (208 mg, 0.96 mmol), oxalyl chloride (0.12 mL, 1.44 mmol), 2-(m -tolyloxy)ethanaminium chloride (180 mg, 0.96 mmol) and Et3N (0.27 mL, 1.92 mmol). Recrystallization from toluene gave a white solid (252 mg, 75%); mp: 112°C; 1H NMR (400 MHz, [D6]DMSO): δH=2.27 (s, 3H), 3.57 (ps q, J = 5.8 Hz, 2H), 3.76 (s, 3 H), 3.80 (s, 3H), 4.08 (t, J =5.9 Hz, 2H), 6.74–6.78 (m, 3 H), 7.00–7.03 (m, 2 H), 7.14–7.18 (m, 1 H), 8.45 ppm (t, J = 5.5 Hz, 1H); 13C NMR (100 MHz, [D6]DMSO): δC=21.0, 38.7, 55.7, 55.9, 65.7, 111.4, 112.0, 112.8, 115.1, 121.3, 121.5, 128.0, 129.1, 139.0, 147.2, 145.0, 158.4, 166.1 ppm; IR (ATR): ṽ =3358, 1646, 1598, 1503, 1260, 1213, 1158, 1033, 860, 790 cm−1; MS (ESI): m/z (%): 350 [M+H]+(100), 372 [M+Na]+(29); HRMS (ESI): m/z calcd for [M+H]+: 350.1159, found: 350.1149.

2,4-Dichloro-N-(2-(m-tolyloxy)ethyl)benzamide (6o)

Prepared according to general procedures 7 and 5b from 2,4-dichlorobenzoic acid (148 mg, 0.78 mmol), oxalyl chloride (0.10 mL, 1.17 mmol), 2-(m -tolyloxy)ethanaminium chloride (146 mg, 0.78 mmol) and Et3N (0.22 mL, 1.56 mmol). Purification by chromatography (CH2Cl2/MeOH, 19:1) gave a white solid (189 mg, 74%); mp: 75°C; 1H NMR (400 MHz, [D6]DMSO): δH=2.27 (s, 3 H), 3.59 (ps q, J =5.7 Hz, 2 H), 4.08 (t, J =5.7 Hz, 2H), 6.73–6.78 (m, 3 H), 7.14–7.18 (m, 1H), 7.42–7.49 (m, 2 H), 7.66–7.67 (m, 1H), 8.70 ppm (t, J =5.5 Hz, 1H); 13C NMR (100 MHz, [D6]DMSO): δC=21.1, 38.7, 65.7, 111.5, 115.1, 121.4, 127.2, 129.1, 129.2, 130.2, 131.1, 134.4, 135.6, 138.9, 158.4, 165.7 ppm; IR (ATR): ṽ =3253, 2931, 1651, 1590, 1540, 1262, 1176, 1104, 786, 691 cm−1; MS (ESI): m/z (%): 324 [M+H]+(30), 341 [M+NH4]+(100); HRMS (ESI): m/z calcd for [M+H]+: 324.0558, found: 324.0538.

2-Chloro-4-nitro-N-(2-(m-tolyloxy)ethyl)benzamide (6p)

Prepared according to general procedures 7 and 5b from 2-chloro-4-nitrobenzoic acid (220 mg, 1.09 mmol), oxalyl chloride (0.14 mL, 1.64 mmol), 2-(m -tolyloxy)ethanaminium chloride (205 mg, 1.09 mmol) and Et3N (0.30 mL, 2.18 mmol). Purification by chromatography (CH2Cl2/MeOH, 19:1) gave a white solid (260 mg, 72%); mp: 94 °C; 1H NMR (400 MHz, [D6]DMSO): δH=2.28 (s, 3 H), 3.63 (ps q, J =5.6 Hz, 2 H), 4.10 (t, J =5.6 Hz, 2H), 6.75–6.79 (m, 3 H), 7.15–7.19 (m, 1 H), 7.67–7.69 (m, 1 H), 8.21–8.33 (m, 2 H), 8.93 ppm (t, J = 5.5 Hz, 1H); 13C NMR (100 MHz, [D6]DMSO): δC=21.0, 38.7, 65.7, 111.5, 115.1, 121.4, 122.3, 124.4, 129.2, 129.8, 131.0, 138.9, 142.5, 148.1, 158.3, 165.1 ppm; IR (ATR): ṽ =3299, 1645, 1531, 1349, 1269, 1176, 1065, 880, 778, 690 cm−1; MS (ESI): m/z (%): 352 [M+NH4]+(100), 357 [M+Na]+(44); HRMS (ESI): m/z calcd for [M+Na]+: 357.0618, found: 357.0596.

4-Amino-2-chloro-N-(2-(m-tolyloxy)ethyl)benzamide (6q)