Abstract

A set polyethylene glycol (PEG) appended BODIPY architectures (BOPEG1 – BOPEG3) have been prepared and studied in CH2Cl2, H2O:CH3CN (1:1) and aqueous solutions. BOPEG1 and BOPEG2 both contain a short PEG chain and differ in substitution about the BODIPY framework. BOPEG3 is comprised of a fully substituted BODIPY moiety linked to a PEG polymer that is roughly 13 units in length. The photophysics and electrochemical properties of these compounds have been thoroughly characterized in CH2Cl2 and aqueous CH3CN solutions. The behavior of BOPEG1 – BOPEG3 correlates with established rules of BODIPY stability based on substitution about the BODIPY moiety. ECL for each of these compounds was also monitored. BOPEG1, which is unsubstituted at the 2- and 6-positions dimerized upon electrochemical oxidation while BOPEG2, which contains ethyl groups at the 2- and 6-positions, was much more robust and served as an excellent ECL luminophore. BOPEG3 is highly soluble in water due to the long PEG tether and demonstrated modest ECL activity in aqueous solutions using tri-n-propylamine (TPrA) as a coreactant. As such, BOPEG3 represents the first BODIPY derivative that has been shown to display ECL in water without the need for an organic cosolvent, and marks an important step in the development of BODIPY based ECL probes for various biosensing applications.

Keywords: ECL, Electrochemistry, Emission, Sensing

INTRODUCTION

Boron-dipyrromethane (BODIPY) dyes represent an important class of molecule characterized by strong absorption and emission profiles in the visible region, high photostability and small Stokes shift.1,2,3 Moreover, the intensity and energy of BODIPY emission can be tuned through the addition of properly placed electron donor and/or acceptor substituents about the chromophore periphery. For instance, prior work has shown that appending electron donating substituents to positions 2 and 6 of the BODIPY core (Scheme 1) shifts the absorption and emission profiles to lower energy wavelengths, while electron withdrawing functionalities have the opposite effect. Furthermore, variation of the BODIPY substitution pattern dramatically impacts the molecule’s emission quantum yield and redox properties. The ability to tailor the photophysical properties of the parent BODIPY dye to a given application has led to the wide adoption of these fluorophores for many biological imaging and other optical studies.4-8

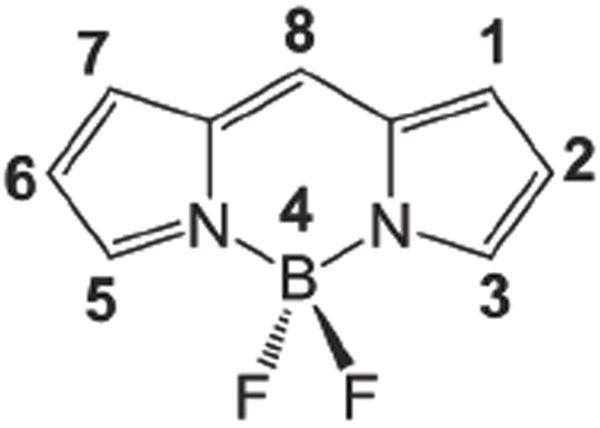

Scheme 1.

Numbered BODIPY skeleton.

Although BODIPY derivatives have been utilized for biological imaging studies, the overwhelming majority of BODIPY photophysical and electrochemical studies have been carried out in organic solvents, while complementary studies in water are scarce.9-13 Emblematic of this are studies dealing with electrogenerated chemiluminescence (ECL) of BODIPY dyes.14 ECL is a widely used technique for blood testing with multi-billion dollar annual revenues.15-17 Polypyrridyl complexes such as Ru(bpy)32+ are typically used as ECL emitters for such applications and are characterized by emission centered at roughly 610 nm.18-23 A suite of ECL probes with output signals that vary in energy would permit for imaging of multiple labeled biological species simultaneously. Accordingly, current efforts are aimed at the development of new ECL probes, which display emission responses that span the visible region and include various nanostructures,24-26 metal polypyrridyl complexes,27 porphyrins28 and other organic fluorophores.29-32 BODIPY derivatives are promising candidates in this regard, since their emission output can be synthetically tuned by varying the substituents about the fluorophore and often display higher solubilities than many other polycyclic hydrocarbons of similar size. Accordingly, the ECL response of BODIPY derivatives substituted by simple alkyl or aromatic groups has been recorded in organic solvents.33-37 However, the dearth of water soluble BODIPY derivatives has precluded analogous studies in aqueous solutions and has limited the development of such species as ECL probes for biological applications. To date, there have been no reports of ECL using BODIPY dyes in water.

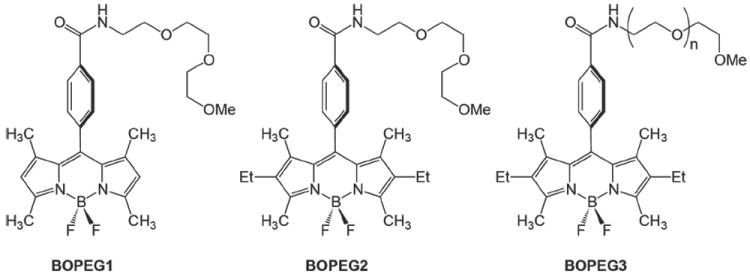

A common strategy for the water solubilization and protection of many proteins, pharmaceuticals and other molecules of biotechnological interest is covalent tethering of polyethyleneglycol chains (PEGylation).38-41 Very recently this general approach was applied to the synthesis of water soluble BODIPY derivatives.12,13 We have prepared a similar set of BODIPY—PEG (BOPEG) conjugates in which both the substituents about the fluorophore periphery and nature of the PEG chain are systematically varied. These compounds are shown in Chart 1. Furthermore, we have undertaken a detailed study of the photophysics and electrochemical properties of these compounds in both non-polar organic solvents and water. Moreover, we report ECL response for each of the BOPEG derivatives, including the first reported ECL spectrum of a BODIPY derivative under aqueous conditions.

Chart 1.

EXPERIMENTAL

General Considerations

Reactions were performed in oven-dried round-bottomed flasks unless otherwise noted. Reactions that required an inert atmosphere were conducted under a positive pressure of N2 using flasks fitted with Suba-Seal rubber septa. Air and moisture sensitive reagents were transferred using standard syringe or cannulae techniques. Silica gel 60 (40-63μm, 60 Å, 230 - 400 mesh) and glass plates coated with silica gel 60 with F254 indicator were used for column and analytical thin-layer chromatography, respectively. Reagents and solvents were purchased from Sigma Aldrich, Acros, Fisher, Strem, or Cambridge Isotopes Laboratories. Solvents for synthesis were of reagent grade or better and were dried by passage through activated alumina and then stored over 4 Å molecular sieves prior to use.42 All other reagents were used as received. Triethylene glycol methyl ether tosylate (2) was prepared using a previously published method.43

Compound Characterization

1H NMR and 13C NMR spectra were recorded at 25 °C on a Bruker 400 MHz spectrometer. Proton spectra are referenced to the residual proton resonance of the deuterated solvent (CDCl3 = δ 7.26) and carbon spectra are referenced to the carbon resonances of the solvent (CDCl3 = δ 77.23). All chemical shifts are reported using the standard δ notation in parts-per-million; positive chemical shifts are to higher frequency from the given reference. LR-GCMS data were obtained using an Agilent gas chromatograph consisting of a 6850 Series GC System equipped with a 5973 Network Mass Selective Detector. LR-ESI MS data was obtained using either a LCQ Advantage from Thermofinnigan or a Shimadzu LCMS-2020. HR-ESI mass spectrometric analyses were performed by the University of Delaware Mass Spectrometry Facility or the Mass Spectrometry Laboratory at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign.

Absorbance and Emission Spectroscopy

Absorption and emission measurements were recorded in either CH2Cl2 or water using 1 cm screw cap quartz cuvettes (7q) from Starna. UV/vis absorption spectra were acquired using a DU 640 spectrophotometer (Beckman) and fluorescence spectra were obtained using a double-beam QuantaMaster Spectrofluorimeter (Photon Technology International) equipped with a 70 W Xe lamp. Slit widths were maintained at 0.5 mm for all emission experiments. All spectral data acquisitions were made at 25.0 ± 0.05 °C.

Electrochemistry and Electrogenerated Chemiluminescence

Electrochemistry experiments were carried out using a standard three-electrode setup. Experiments in CH2Cl2 were conducted using a 0.0314 cm2 platinum disk working electrode, a platinum auxiliary electrode, and a silver wire quasireference electrode. Experiments in aqueous solutions employed an analogous setup with a glassy carbon (area = 0.071 cm2 or 0.2 cm2) working electrode. A straight working electrode (disk oriented horizontally downward) was used for the CV measurements and an L-shaped electrode (disk oriented vertically) was used for the ECL experiments. Working electrodes were polished prior to every experiment with 0.3 μm alumina particles dispersed in water, followed by sonication in ethanol and water for several minutes. Electrochemical measurements employing methylene chloride were conducted in an argon filled glovebox using a conventional electrochemical apparatus with a Teflon plug containing three metal rods for electrode connections. Glassware for electrochemistry was dried for one hour at 120 °C prior to transfer to the glovebox. Supporting electrolytes used for electrochemistry experiments were 0.1 M tetrabutylammonium hexafluorophosphate (TBAPF6) for experiments in methylene chloride, tetramethylammonium perchlorate (TMAP) for 50% aqueous acetonitrile and phosphate buffer for studies in water. Ferrocene was used to calibrate the Ag wire quasireference electrode (QRE) taking the Fc/Fc+ potential as 0.342 V vs SCE.44 Cyclic voltammetry and chronoamperometry experiments were carried out with a CHI instruments model 660 electrochemical workstation.

ECL transients and simultaneous CV-ECL measurements were made using a multichannel Eco Chemie Autolab PGSTAT100 (Utrecht, The Netherlands) instrument. ECL recorded using annihilation methods were obtained by pulsing the applied potential (~80 mV past the peak potential) in 0.1 sec increments for 60 sec. The slit width was set to be 0.5 cm for these experiments. ECL spectra recorded using benzoyl peroxide, ammonium or potassium persulfate and tri-n-propylamine (TPrA) as coreactants, and were obtained by stepping to 80 mV from the reduction or oxidation peak of the BOPEG derivative at a pulse frequency of 1 Hz with a step time determined by experimental conditions. ECL spectra were recorded with a Princeton Instruments Spec 10 CCD camera (Trenton, NJ) with an Acton SpectPro-150 monochromator cooled with liquid nitrogen to −100 °C. The CCD camera was calibrated by using an Hg/Ar pen-ray lamp from Oriel (Stratford, CT). ECL-potential signals were recorded using a photomultiplier tube (PMT, Hamamatsu R4220, Japan) and ECL quantum yield measurements for each BOPEG derivative obtained using Ru(bpy)32+ as a standard. Voltage for the PMT (−750 V), was provided by a Kepco power supply (New York, NY) and the signal from the PMT to the potentiostat was transferred through a Model 6517 multimeter (Keithley Instruments Inc., Cleveland, OH).

1-Azido-2-(2-(2-methoxyethoxy)ethoxy)ethane (3)

Triethylene glycol methyl ether tosylate (2) (500 mg, 1.6 mmol) and NaN3 (1.25 g, 19.2 mmol) were dissolved in a 5 mL solution of 30% aqueous methanol. The reaction solution was heated at 80 °C with stirring for 15 hrs, after which time, the aqueous mixture was extracted four times with CH2Cl2. After drying the organic phase over Na2SO4, the solvent was removed under reduced pressure to produce 180 mg of a clear oil (59 %), which was carried forward without further purification. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3, 25 °C) δ/ppm: 3.62 – 3.56 (m, 6H), 3.49 – 3.47 (m, 4H), 3.32 (t, 2H), 3.30 (s, 3H). 13C NMR (101 MHz, CDCl3, 25 °C) δ/ppm: 77.16, 71.65, 70.40, 70.38, 70.32, 69.78, 58.71, 53.38, 50.39. νmax (CH2Cl2)/cm-1 2108 (s, N3).

2-(2-(2-methoxyethoxy)ethoxy)ethanamine (4)

To 1.55 g (8.2 mmol) of azide 3, dissolved in a solution of THF (10 ml) and water (1.2 mL) was added 2.68 g (10.2 mmol) of PPh3. The resulting solution was stirred under air for 6 hrs, following which, the solvent was removed under reduced pressure. The crude product was purified on a silica column using CH2Cl2 and MeOH (5:1) containing 2% Et3N as the eluent to generate 708 mg of a clear oil (53 %). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3, 25 °C) δ/ppm: 3.66 – 3.61 (m, 6H), 3.56 – 3.53 (m, 2H), 3.52 – 3.48 (t, J = 8.0 Hz, 2H), 3.37 (s, 3H) 2.86 (s, 2H). 13C NMR (101 MHz, CDCl3, 25 °C) δ/ppm: 77.16, 71.73, 70.41, 70.34, 70.08, 58.88, 29.52. HR-ESI-MS: [M + H]+ m/z: calcd for C7H18NO3, 164.1281; found, 164.1274.

tert-Butyl 4-formylbenzoate (6)

4-Formylbenzoic acid (5) (1.5 g, 10 mmol) and 2.68 g of N,N′-Dicyclohexylcarbodiimide (13 mmol) were dissolved in 100 mL of CH2Cl2. To this solution were added 10 mL of tert-butanol (104 mmol) and 10.1 g of DMAP (82.6 mmol). The resulting solution was stirred for 14 hrs prior to being filtered to remove any insoluble materials. After removing all volatiles under reduced pressure, the resulting crude material was purified on a silica column using 10% hexanes in CH2Cl2 as the eluent to yield 860 mg (42 %) of the desired product as a white solid. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3, 25 °C) δ/ppm: 10.09 (s, 1H), 8.13 (d, J = 8.2 Hz, 2H), 7.92 (d, J = 8.6 Hz, 2H), 1.61 (s, 9H). 13C NMR (101 MHz, CDCl3, 25 °C) δ/ppm: 191.95, 164.77, 138.90, 137.15, 130.13, 129.53, 82.15, 28.24. GCMS [M]+ m/z: Calcd for C12H14O3, 206.0. Found, 206.

8-(4-carboxyphenyl)-1,3,7,9-tetramethyl-BODIPY (7)

To 400 mg of t-butyl 4-formylbenzoate (6) (1.94 mmol) dissolved in 60 mL of CH2Cl2 was added 0.44 mL of 2,4-dimethylpyrrole (4.27mmol) and the resulting solution was sparged with N2 for 10 minutes. Following the addition of 52 μL (0.71 mmol) of trifluoroacetic acid, the resulting solution was stirred under a nitrogen atmosphere for 18 hrs at room temperature. Tetrachloro-1,4-benzoquinone (477 mg, 1.94 mmol) was added to the reaction, which was stirred for an addition 20 min, after which, 1.75 mL of TEA (12.6mmol) and 2.63 ml of BF3•OEt2 (21.4mmol) were added to the stirred solution. The resulting mixture was stirred for an additional 45 min and the solvent was then removed under reduced pressure. Purification of the crude purple solid by chromatography on silica was accomplished using a mobile phase of ethyl acetate and CH2Cl2 (1:1) to deliver 560 mg of a red solid. Yield 68%. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3, 25 °C) δ/ppm: 8.24 (d, J = 8.1 Hz, 2H), 7.45 (d, J = 8.2 Hz, 2H), 6.00 (s, 2H) 2.57 (s, 6 H), 1.37 (s, 6H). 13C NMR (101 MHz, DMSO, 25 °C) δ/ppm: 166.92, 155.28, 142.72, 140.81, 138.34, 131.83, 130.11, 128.32, 121.56, 14.23, 13.94. ESI-MS [M − H]−, m/z: Calcd for C20H18BF2N2O2, 367.14. Found, 367.

(8-(4-carboxyphenyl)-2,8-diethyl-1,3,7,9-tetramethyldipyrromethane (8)

This compound was prepared following the same procedure as that used for the synthesis of BODIPY acid 7, using 380 mg t-butyl 4-formylbenzoate (6) (1.84 mmol) and 0.50 mL of 2,4-dimethyl-3-ethylpyrrole (3.69 mmol). All other reagents were scaled appropriately and the crude material was purified by chromatography on silica using a mobile phase of ethyl acetate and CH2Cl2 (1:1) to deliver 380 mg of a red solid. Yield 49%. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3, 25 °C) δ/ppm: 8.21 (d, J = 7.1 Hz, 2H), 7.41 (d, J = 7.1 Hz, 2H), 2.50 (s, 6H), 2.26 (q, J = 7.4 Hz, 4H), 1.23 (s, 6H), 0.94 (t, J = 7.4 Hz, 6H). 13C NMR (101 MHz, CDCl3, 25 °C) δ/ppm: 170.24, 154.57, 141.84, 138.60, 138.23, 133.34, 131.09, 130.38, 129.75, 129.14, 17.26, 14.87, 12.80, 12.09. ESI-MS [M − H]−, m/z: Calcd for C24H26BF2N2O2, 423.21. Found, 423.

8-(4-(N-succinimidoxycarbonyl)phenyl)-1,3,7,9-tetramethyl-BODIPY (9)

Carboxylic acid BODIPY derivative 7 (0.47 mmol, 172 mg) was dissolved in 12 ml of DMF. N-Hydroxysuccinimide (0.71 mmol, 82 mg) was added followed by the addition of N-(3-Dimethylaminopropyl)-N′-ethylcarbodiimide hydrochloride (0.71 mmol, 136 mg). Reaction was stirred at room temperature for 18 hr then solvent was removed under reduced pressure. Column chromatography was used to purify the product with hexanes and ethyl acetate (2:1) giving 128 mg of a red solid. Yield 56 %. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3, 25 °C) δ/ppm: 8.26 (d, J = 8.2 Hz, 2H), 7.49 (d, J = 8.2 Hz, 2H), 6.00 (s, 2H) 2.94 (s, 4H), 2.56 (s, 6H), 1.37 (s, 6H); 13C NMR (101 MHz, CDCl3, 25 °C) δ/ppm: 169.40, 161.47, 156.54, 143.03, 142.28, 139.38, 131.53, 130.88, 129.22, 125.92, 121.93, 25.90, 15.06, 14.83. ESI-MS [M + H]+, m/z: Calcd for C24H23BF2N3O4, 466.17. Found, 466.

8-(4-(N-succinimidoxycarbonyl)phenyl)-2,8-diethyl-1,3,7,9-tetramethyl-BODIPY (10)

Carboxylic acid BODIPY derivative 8 (54 mg, 0.13 mmol) was dissolved in 10 mL of DMF and 23 mg (0.2 mmol) of N-hydroxysuccinimide was added to the solution followed by 38 mg (0.2 mmol) of N-(3-Dimethylaminopropyl)-N′-ethylcarbodiimide hydrochloride (EDC). The resulting reaction mixture was stirred at room temperature for 10 hrs, following which the solvent was removed by rotary evaporation. The product was purified by column chromatography on silica using hexanes and ethyl acetate (2:1) as the mobile phase to deliver giving 43 mg of the title compound in 65% yield. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3, 25 °C) δ/ppm: 8.27 (d, J = 8.3 Hz, 2H), 7.50 (d, J = 8.3 Hz, 2H), 2.96 (s, 4H), 2.54 (s, 6H), 2.31 (q, J = 8.0 Hz, 4H), 1.27 (s, 6H), 0.98 (t, J = 7.5 Hz, 6H); 13C NMR (101 MHz, CDCl3, 25 °C) δ/ppm: 169.72, 161.84, 155.09, 143.46, 138.47, 138.14, 133.77, 131.70, 130.50, 129.78, 125.96, 26.18, 17.52, 15.07, 13.06, 12.59.

BOPEG1

To 50 mg (0.11 mmol) of BODIPY synthon 9 dissolved in 5 mL of CH2Cl2 was added 5 mL of CH2Cl2 containing 38 mg of amine 4 (0.23 mmol). To the reaction was added 130 μL (0.93 mmol) of triethylamine and the resulting solution was stirred at room temperature for 15 hrs. The reaction was then diluted with additional CH2Cl2 and washed with water. After the organic fraction was separated, it was dried over Na2SO4 and the solvent was removed by rotary evaporation. The crude product was purified by column chromatography on silica using CH2Cl2 and ethyl acetate (4:1) as the eluent to deliver 60 mg of the desired compound as a red solid. Yield is quantitative. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3, 25 °C) δ/ppm: 7.96 (d, J = 8.3 Hz, 2H), 7.38 (d, J = 8.3 Hz, 2H), 5.98 (s, 2H), 3.66 (m, 10H), 3.55 (m, 2H), 3.34 (s, 3H), 2.55 (s, 6H), 1.36 (s, 6H). 13C NMR (101 MHz, CDCl3, 25 °C) δ/ppm: 166.71, 155.94, 143.00, 140.56, 138.26, 135.04, 131.08, 128.23, 121.49, 114.45, 71.96, 70.58, 70.48, 70.23, 69.89, 59.05, 39.98, 14.67. HR-ESI-MS: [M + H]+ m/z: calcd for C27H34BF2N3O4, 514.2699; found, 514.2628

BOPEG2

To 47 mg (0.09 mmol) of BODIPY synthon 10 dissolved in 5 mL of CH2Cl2 was added 5 mL of CH2Cl2 containing 33 mg of amine 4 (0.20 mmol). To the reaction was added 120 μL (0.86 mmol) of triethylamine and the resulting solution was stirred at room temperature for 15 hrs. The reaction was then diluted with additional CH2Cl2 and washed with water. After the organic fraction was separated, it was dried over Na2SO4 and the solvent was removed by rotary evaporation. The crude product was purified by column chromatography on silica using CH2Cl2 and ethyl acetate (4:1) as the eluent to deliver 48 mg (98 %) of the desired compound as a red solid. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3, 25 °C) δ/ppm: 7.96 (d, J = 8.2 Hz, 2H), 7.38 (d, J = 8.2 Hz, 2H), 6.99 (s, 1H), 3.70 (dd, J = 8.1, 5.6 Hz, 8H), 3.69 – 3.65 (m, 2H), 3.55 (dd, J = 5.6, 3.5 Hz, 2H), 3.34 (s, 3H), 2.53 (s, 6H), 2.29 (q, J = 7.5 Hz, 4H), 1.26 (s, 6H), 0.97 (t, J = 7.5 Hz, 6H). 13C NMR (101 MHz, CDCl3, 25 °C) δ/ppm: 166.79, 154.29, 139.25, 139.02, 138.30, 134.97, 133.16, 130.56, 128.80, 128.00, 72.05, 70.70, 70.62, 70.37, 69.93, 59.15, 40.03, 29.84, 17.19, 14.73, 12.67, 12.03. HR-ESI-MS: [M − F]+ m/z: calcd for C31H42BFN3O4, 550.3252; found, 550.3246.

Poly(ethylene glycol) methyl ether tosylate (12)

To 10.0 g (18.2 mmol) of poly(ethylene glycol) methyl ether (15) (Average Mn 550) dissolved in 40 mL of CH2Cl2 was added 5.1 mL (36.4 mmol) of triethylamine. To this stirred mixture, was added in dropwise fashion, a solution of 5.2 g (27.3 mmol) of tosyl chloride dissolved in 40 ml of CH2Cl2. The reaction was stirred for 24 hrs at room temperature and then washed sequentially with 1 M HCl (3 × 80 mL) and brine and then dried over Na2SO4 and concentrated under reduced pressure. The crude product was purified by column chromatography on silica using 5% CH3OH in CH2Cl2 to deliver 7.5 g (58 %) of the title compound as a colorless oil. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3, 25 °C) δ/ppm: 7.78 (d, J = 8.3 Hz, 2H), 7.33 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 2H), 4.18 – 4.10 (m, 2H), 3.71 – 3.50 (m, 31H), 3.37 (s, 2H), 2.44 (s, 2H), 2.00 (s, 1H). 13C NMR (101 MHz, CDCl3, 25 °C) δ/ppm: 144.86, 132.95, 129.88, 128.02, 71.95, 70.76, 70.63, 70.59, 70.54, 69.31, 68.69, 59.09, 53.55, 21.71. Mass spectral analysis showed the PEG chain to be roughly 12 – 14 units in length. This distribution was centered around a polymer chain 13 glycol units long. HRESI- MS: [M + Na]+ m/z: calcd for C34H62NaO16S, 781.3651; found, 781.3634.

Poly(ethylene glycol) methyl ether azide (13)

A combination of 1.0 g (1.42 mmol) of poly(ethylene glycol) methyl ether tosylate (12) and NaN3 (1.1 g, 17 mmol) were dissolved in 1.5 mL of methanol and 3.5 mL of deinoized water. The reaction was then heated at 80 °C with stirring for 15 hrs. After cooling the solution to room temperature, the aqueous mixture was extracted four times is CH2Cl2. The organic extracts were combined, dried over Na2SO4 and concentrated under reduced pressure to deliver the desired azide as a clear oil. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3, 25 °C) δ/ppm: 3.66 – 3.61 (m, 36H), 3.55 – 3.51 (m, 4H), 3.36 (t, 2H), 3.35 (s, 3H). 13C NMR (101 MHz, CDCl3, 25 °C) δ/ppm: 72.06, 70.83, 70.80, 70.76, 70.69, 70.18, 59.20, 50.80. Mass spectral analysis showed the PEG chain to be roughly 12 – 14 units in length. This distribution was centered around a polymer chain 13 glycol units long. APCI-MS: [M + Na]+ m/z: calcd for C27H55N3NaO13, 652.36; found, 652. νmax (CH2Cl2)/cm-1 2109 (s, N3).

Poly(ethylene glycol) methyl ether amine (14)

Poly(ethylene glycol) methyl ether azide (13) (660 mg, 1.12 mmol) was dissolved in 10 mL of THF and 1.2 mL of water. To this solution was added 365 mg (1.4 mmol) of PPh3 and the reaction was stirred at room temperature for 8 hrs. Following removal of the solvent under reduced pressure, the product was purified by column chromatography on alumina using 10% CH3OH in CH2Cl2 to deliver 424 mg (67%) of the title compound as a colorless oil. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3, 25 °C) δ/ppm: 3.83 (br, 44H), 3.53 (br, 4H), 3.36 (br, 3H), 2.87 (br, 2H). 13C NMR (101 MHz, CDCl3, 25 °C) δ/ppm: 72.95, 71.77, 70.44, 70.41, 70.36, 70.11, 58.90, 53.47, 41.56. Mass spectral analysis showed the PEG chain to be roughly 12 – 14 units in length. This distribution was centered around a polymer chain 13 glycol units long. HR-ESI-MS: [M + H]+ m/z: calcd for C27H58NO13, 604.3903; found, 604.3902.

BOPEG3

Amine 14 (93 mg, 0.16 mmol) was dissolved in 5 mL of CH2Cl2 and added to 43 mg (0.08mmol) of BODIPY synthon 10 that was dissolved in 5 ml of CH2Cl2. Triethylamine (120 μL, 0.86 mmol) was added to the reaction, which was stirred at room temperature for 15 hrs. Following dilution of the reaction with additional CH2Cl2, the crude mixture was washed with water and dried over Na2SO4. After removal of the solvent under reduced pressure, the product was purified via column chromatography. Purification involved flash chromatography on silica using CH2Cl2 containing 3% CH3OH as the mobile phase, followed by a second gravity column on alumina using CH2Cl2 containing 0.5% CH3OH as the eluent to deliver 40 mg (51%) of the desired BODIPY derivative as a red solid. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3, 25 °C) δ/ppm: 7.99 (d, J = 8.2 Hz, 2H), 7.37 (d, J = 8.1 Hz, 2H), 3.70 (d, J = 11.5 Hz, 6H), 3.67 – 3.57 (m, 26H), 3.54 (dd, J = 5.6, 3.6 Hz, 2H), 3.37 (s, 3H), 2.53 (s, 6H), 2.29 (q, J = 8 Hz, 4H), 1.25 (s, 6H), 0.97 (t, J = 7.5 Hz, 6H); 13C NMR (101 MHz, CDCl3, 25 °C) δ/ppm: 167.09, 154.55, 139.46, 139.39, 138.61, 135.24, 133.43, 130.84, 129.04, 128.41, 72.35, 71.03, 70.98, 70.96, 70.63, 70.32, 59.50, 40.38, 30.15, 17.51, 15.08, 12.99, 12.36. Mass spectral analysis showed the PEG chain to be roughly 12 – 14 units in length. This distribution was centered around a polymer chain 13 glycol units long. HR-ESI-MS: [M + Na]+ m/z: calcd for C49H78BF2N3NaO13, 988.5488; found, 988.5486.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Synthesis and Characterization

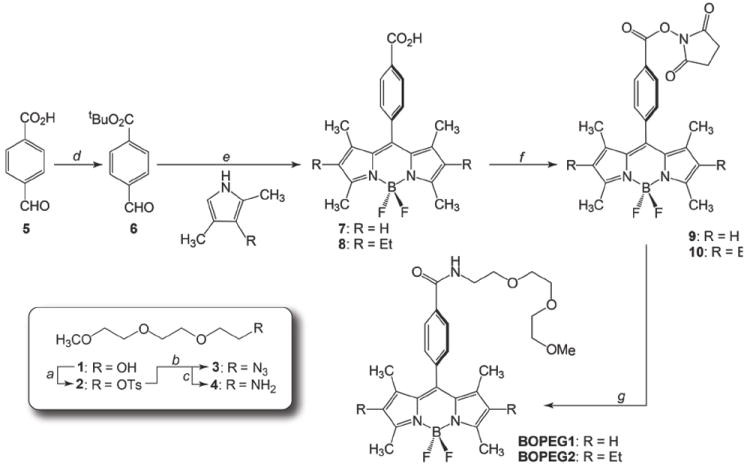

Synthesis of the three BOPEG derivatives of Chart 1 began with BOPEG1 and BOPEG2. The synthetic route to these compounds is presented in Scheme 2. The preparation of these two homologues is highly parallel with BOPEG1 and BOPEG2 differing only in the substitution of the 2,6-positions on the indacene framework. The syntheses began with the conversion of triethylene glycol monomethyl ether (1) to the corresponding tosylate (2) by treatment with tosyl chloride and base. Substitution with NaN3 generated the corresponding terminal azide (3), which was subsequently converted to amine 4 by reduction with PPh3 in aqueous THF.

Scheme 2.

Synthesis of BOPEG1 and BOPEG2.

a) Tos–CI, NEt3; b) NaN3, MeOH; c) PPh3, THF, H2O; d) tBuOH, DCC, DMAp; e) 1. TFA; 2. p-chloranil; 3. BF3•OEt2, NEt3; f) NHS,EDC, DMF; g) 4, NEt3, DCM.

The BODIPY based synthons were prepared by adapting standard synthetic methodologies for the fluorescent dyes. Initial attempts to prepare BODIPY-carboxylic acids 7 and 8 directly from 4-formylbenzoic acid (5) and the appropriate pyrroles failed due to the insolubility of the aldehyde in the typical chlorinated solvents used for BODIPY synthesis. Accordingly, we converted 5 to the tert-butyl ester to improve the solubility of the aldehyde building block. Esterification of 4-formylbenzoic acid (5) with tert-butanol using DCC and DMAP delivered aldehyde 6.45 Condensation of 6 with either 2,4-dimethylpyrrole or 2,4-dimethyl-3-ethyl pyrrole using TFA as an acid catalyst, followed by oxidation with p-chloranil and addition BF3•OEt2 cleanly generated BODIPY derivatives 7 and 8 in 68% and 50% yield, respectively (Scheme 2).

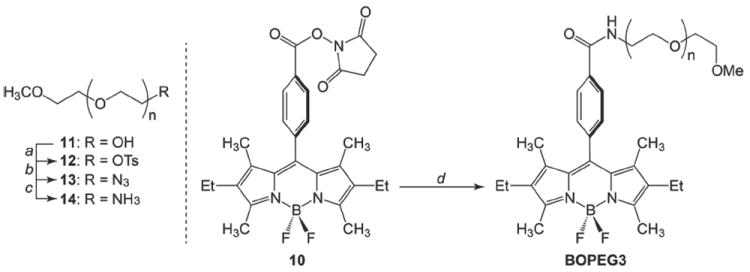

The synthesis of the PEGylated BODIPY constructs was completed in two succinct steps. The BODIPY carboxylic acids (7 and 8) were first activated by conversion to the corresponding N-hydroxysuccinimide esters (9 and 10) using a standard EDC coupling method.46 Subsequent incubation of 9 or 10 with amine 4 cleanly delivered the desired BOPEG1 and BOPEG2 derivatives in quantitative yield. The third PEG appended BODIPY derivative was prepared similarly, except that a significantly longer PEG chain was employed to ensure that BOPEG3 would be water-soluble. As shown in Scheme 3, poly(ethylene glycol) methyl ether of average Mn = 550 (11) was converted to the corresponding amine (14) following the identical strategy used for amine 4 (vide supra). This approach afforded a PEG chain averaging 12 – 13 glycol units in length with a terminal amino group (14). Incubation of 14 with BODIPY derivative 10 cleanly delivered BOPEG3 in good yield.

Scheme 3.

Synthesis of BOPEG3.

a) Tos–CI, NEt3; b) NaN3, MeOH; c) PPh3, THF, H2O; d) 14, NEt3, DCM.

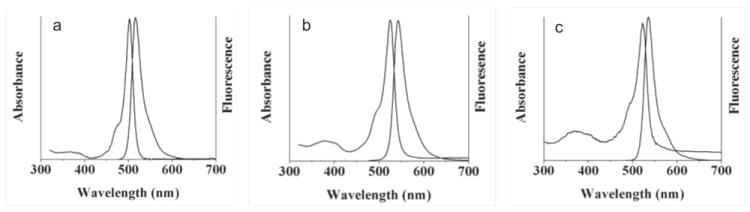

BOPEG Photophysics

Basic photophysical characterization of the BOPEG derivatives of Chart 1 was undertaken to determine how the PEG substituents influence the electronic structure of the BODIPY dye. Steady state UV-vis and fluorescence data for each of the compounds studied is reproduced in Table 1. In general, the PEG groups do not markedly affect the observed BODIPY photophysics, which are typical of the pyrrole substitution pattern. BOPEG1 displays characteristic electronic absorbance and emission profiles common to BODIPY derivatives, which are unsubstituted at the 2- and 6-positions,1 with absorbance and emission maxima at 503 and 515 nm, respectively in CH2Cl2 (Figure 1a).

Table 1.

Photophysical parameters for BOPEG dyes in CH2Cl2.

| Dye | λabs (nm) | ε × 104 (M−1cm−1) | λem (nm) | ϕfl | Es (eV) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BOPEG1 | 352, 503 | 0.70, 7.9 | 515 | 0.82 | 2.41 |

| BOPEG2 | 370, 520 | 0.70, 7.8 | 535 | 0.70 | 2.32 |

| BOPEG3 | 371, 519 | 0.68, 7.5 | 537 | 0.59 | 2.31 |

Figure 1.

Absorption and fluorescence spectra of 2 μM CH2Cl2 solutions of (a) BOPEG1; (b) BOPEG2; (c) BOPEG3.

BOPEG2 and BOPEG3 display similar spectral profiles that are shifted ~20 – 30 nm to longer wavelengths due to the ethyl groups at the 2- and 6-positions of the BODIPY framework (Figure 1b,c). Variation of PEG chain length does not attenuate the dye photophysics. All three BOPEG dyes display small Stokes shifts of 12 – 15 nm, and relatively high fluorescence quantum yields, which range from 59 – 82%. Both of these observations are typical of BODIPY derivatives. Interestingly, increasing the length of the PEG chain, is manifest in lower fluorescence quantum yields. The BOPEG photophysics are also largely invariant to solvent polarity, as absorbance and fluorescence spectra with similar profiles to those obtained in CH2Cl2 were also obtained in polar solvents such as MeCN or water (Figure S1).

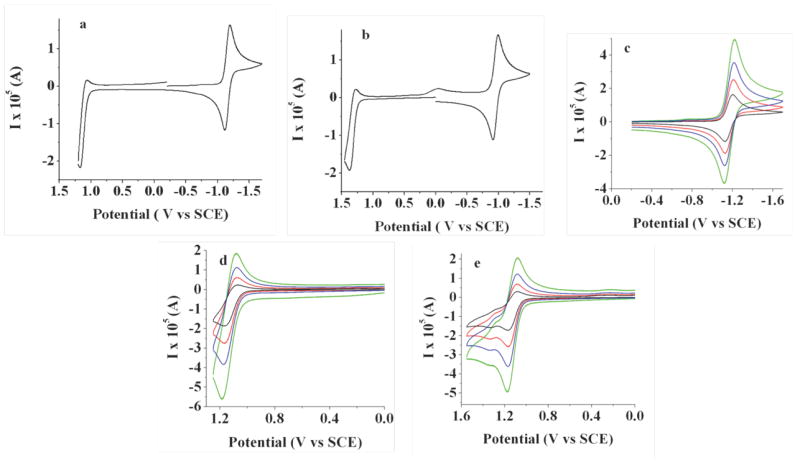

BOPEG Electrochemical Properties

The electrochemical properties of each of the three BOPEG dyes have been studied in CH2Cl2. and are summarized in Table 2. Each BOPEG derivative displays single electron oxidation and reduction waves, the potentials and reversibility of which are impacted by dye substitution and PEG chain length. For example, BOPEG1 exhibits a reversible nernstian reduction (Figure 2a-c) and some degree of irreversibility upon oxidation. This irreversible oxidation is consistent with instability of the BODIPY radical cation due to dimerization through the unsubstituted positions on the indacene framework, which has been observed previously.14,47 At faster scan rates, the oxidation process appears more reversible due to suppression of the dimerization kinetics (Figure 3h,p). The appearance of a second set of oxidation peaks at 1.03 and 1.27 V vs SCE, further supports this dimerization mechanism. Digital simulations are also consistent with a radical radical cation (rrc) mechanism,48,49 which is a well-established dimerization mechanism for BODIPY dyes lacking substituents at the indacene 2- and 6-positions. Relevant parameters for dimerization of BOPEG1 are summarized by equations 1 - 5 below.

| (1) |

| (2) |

| (3) |

| (4) |

| (5) |

Successful fitting of the simulations at two concentrations (1.0 and 2.2 mM), as shown in Figure 3 is accomplished with a dimerization constant of 400 M−1s−1, which is relatively small compared to the analogous process for simple BODIPY homologs14,33 and is reflected by the disappearance of the dimer oxidation waves as scan rates approach 1.0 V/s (Figure 3h,p).

Table 2.

Electrochemical parameters for BOPEG dyes in CH2Cl2.

| Dye | E1/2 (vs SCE) | ECL | E0-0 (eV) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A/A− | A/A+ | λmax (nm) | ΦECL | ||

| BOPEG1 | −1.21 V | 1.11 V | 532 | 0.005 | 2.32 |

| BOPEG2 | −1.36 V | 0.94 V | 534 | 0.20 | 2.30 |

| BOPEG3 | −1.36 V | 0.95 V | 551 | 0.002 | 2.31 |

Figure 2.

Cyclic voltammograms of 2.4 mM BOPEG1 at a scan rate of 0.1 V/s: (a) first scan negative; (b) first scan positive; (c – e) scan rate study for 0.1 V/s (black line), 0.25 V/s (red line), 0.5 V/s (blue line) and 1.0 V/s (green line). CV measurements employed 0.1 M TBAPF6 in CH2Cl2 as the supporting electrolyte and a platinum disk electrode (A = 0.0314 cm2).

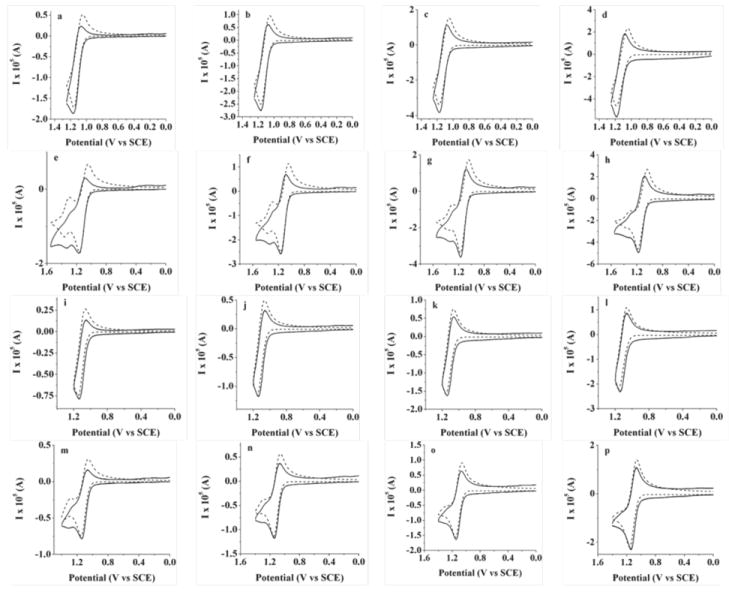

Figure 3.

Experimental (solid line) and simulated (dashed line) traces for oxidation of (a-h) 2.2 mM and (i-p) 1 mM of BOPEG1; (a),(e), (i), (m) scan rate 0.1 V/s; (b), (f), (j), (n) 0.25 V/s; (c), (g), (k), (o) 0.5 V/s; (d), (h), (l), (p) 1 V/s. CV measurements employed 0.1 M TBAPF6 in CH2Cl2 as the supporting electrolyte and a platinum disk electrode (A = 0.0314 cm2). Simulated data: diffusion coefficient of the dye is 7 × 10-6 cm2/s; uncompensated resistance 800 Ω; capacitance 3 × 10-7 F. The dimerization constant was set equal to 400 M-1 s-1 with a deprotonation constant of 1010 s-1.

BOPEG2 exhibits reversible single electron oxidation and reduction waves at virtually identical potentials (Table 2). CV traces for these experiments are reproduced in Figure S2 of the Supporting Information. The length of the PEG chain appended to the BODIPY moiety impacts the observed electrochemistry in CH2Cl2. Although BOPEG3 displays oxidation and reduction waves in CH2Cl2 at potentials that are similar to those observed for BOPEG2, these processes are less reversible due to the large molecular weight and length of this compound’s PEG chain (Figure S3), which may insulate the BODIPY unit from the electrode. Although we did not observe the formation of a film of BOPEG3 on the electrode surface during electrochemistry experiments, the lack of reversibility in the CVs may also be due to adsorption of this BODIPY derivative at the electrode surface. Each of the BOPEG derivatives displays an electrochemical HOMO-LUMO gap of ~2.3 eV, which is good agreement with the E0−0 values obtained from the BOPEG photophysics (Table 1).

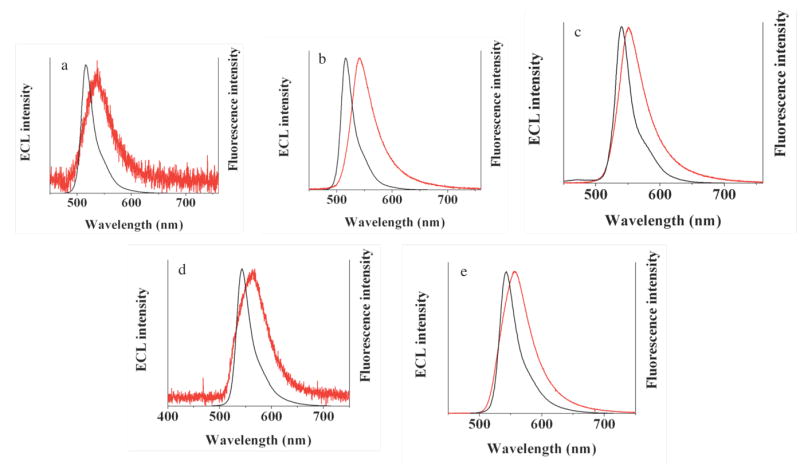

Electrogenerated chemiluminescence of BOPEG derivatives

ECL studies for each of the BOPEG derivatives were conducted in a variety of solvents, including CH2Cl2, aqueous acetonitrile and water. In general, the ECL spectra recorded for each of the BOPEG derivatives are similar to the normal fluorescence profiles recorded for each BODIPY derivative when corrected for a small inner filter effect.34 Initial experiments were carried out for BOPEG1 in CH2Cl2 by pulsing at 10 Hz (for 1 – 30 min) to generate radical ions, but their subsequent annihilation only produced low light levels (Figure 4a). The general mechanistic scheme established for ECL by an annihilation mechanism is embodied by Equations 6 - 9.

| (6) |

| (7) |

| (8) |

| (9) |

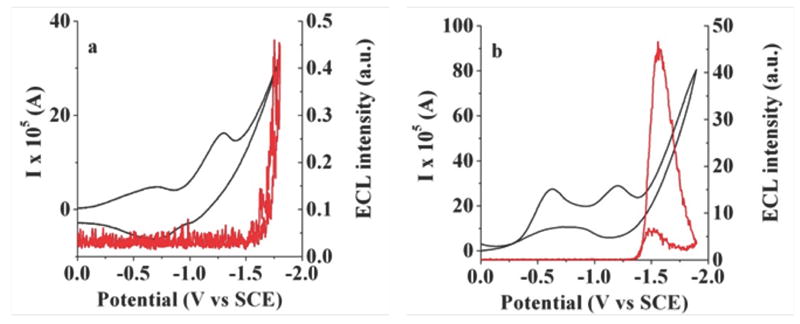

Figure 4.

ECL (red) and fluorescence (black) spectra for 2.2 mM BOPEG1 obtained (a) by annihilation or (b) in the presence of 10 mM BPO; (c) annihilation results for 2.2 mM BOPEG2. Spectra obtained for 2.2 mM BOPEG3 by (d) annihilation and (e) in the presence of 10 mM BPO. Stepping time = 1 minute, frequency = 10 Hz, platinum working electrode (A = 0.0314 cm2) in 0.1 M TBAPF6 in CH2Cl2.

The weak ECL produced through the annihilation mechanism for BOPEG1 can be rationalized for in terms of the instability of the BOPEG1•+ species (vide supra). By contrast, a strong ECL signal was obtained upon reduction of CH2Cl2 solutions of BOPEG1 in the presence of a benzoyl peroxide (BPO) co-reactant (Figure 4b),50-52 presumably following the pathway outlined below (Eq 10 - 14).

| (10) |

| (11) |

| (12) |

| (13) |

| (14) |

BOPEG2 displays a relatively high ECL annihilation quantum yields in CH2Cl2 (Table 2). The efficiency of the annihilation pathway for this compound (Figure 4c) is a result of the reversible oxidation and reduction of the BODIPY moiety. BOPEG3 displays an ECL quantum yield that is markedly lower than that observed for BOPEG2 despite the fact that both these systems have identical substitution patterns. This is may be due to slow ET kinetics or adsorption of BOPEG3 derivative at the electrode surface, as the low ECL efficiency observed for this compound reflects the irreversibility associated with oxidation and reduction of this large BODIPY derivative (vide supra). Accordingly, annihilation experiments employing BOPEG3 only produce weak emission (Figure 4e), while reduction in the presence of BPO generates a much stronger ECL signal (Figure 4f). Note that each of the ECL spectra of Figure 4, are very similar to the normal fluorescence spectra when corrected for a small difference inner filter effect.37

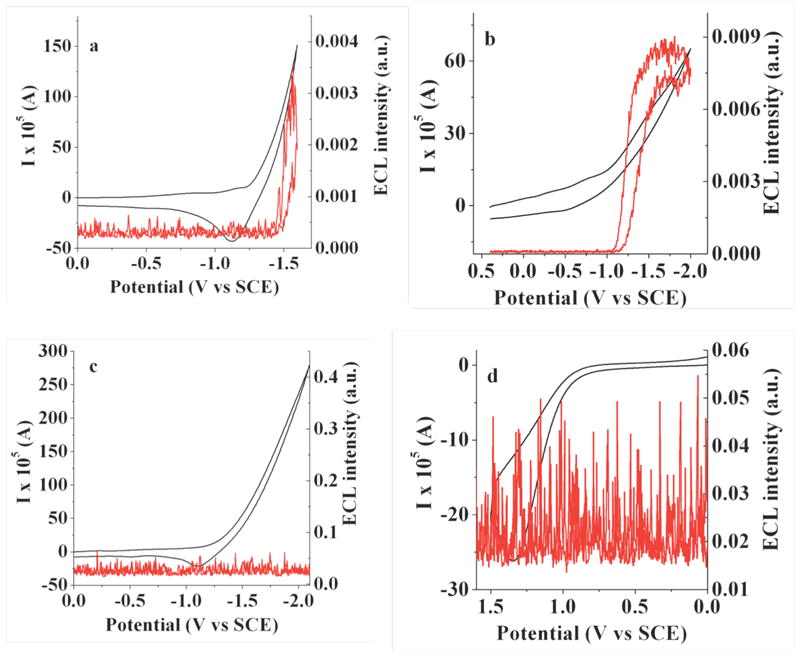

The ECL properties of the BOPEG derivatives were also surveyed in aqueous solutions. The relatively short length of the PEG chains of BOPEG1 and BOPEG2 limits the solubility of these compounds in water and dictated that our ECL studies be conducted in 50% aqueous solutions of MeCN. Given the poor solubility of these derivatives, CV-ECL measurements proved useful in detecting the small ECL signals obtained under these conditions. Using ammonium or potassium persulfate (20 mM) as the reductive coreactant,53 ECL was generated for BOPEG1 and BOPEG2 (Figures 5 - 6) following the mechanism outlined by Equations 15 - 18.

| (15) |

| (16) |

| (17) |

| (18) |

Figure 5.

Simultaneous ECL-CV measurements for 2 mM BOPEG1 in (a) 50% aqueous MeCN with 20 mM ammonium persulfate; (b) 20 mM potassium persulfate in 0.1 M phosphate buffer (pH = 7.4). CV traces are shown in black with corresponding ECL response in red.

Figure 6.

Simultaneous ECL-CV measurements for 2 mM BOPEG2 in (a) 50% aqueous MeCN with 20 mM ammonium persulfate; (b) 20 mM potassium persulfate in 0.1 M phosphate buffer (pH = 7.4); (c) 2 mM BOPEG2 in 50% aqueous MeCN without coreactant; (d) 0.2 mM BOPEG2 in 50% aqueous MeCN containing 10 mM TPrA; Scan rate = 1 V/s; 0.1 M TMAP was employed as the supporting electrolyte when using 50% aqueous MeCN as the solvent. CV traces are shown in black with corresponding ECL response in red.

The simultaneous CV-ECL experiments clearly implicate persulfate reduction, as ECL signal is strongly correlated to SO4•− formation at potentials more negative than – 1.4 V vs. SCE. Similarly, no ECL response is observed in the absence of either persulfate or the BOPEG dye. The data recorded under the conditions outlined in Figures 5 and 6 is noisy due to hydrogen evolution at the electrode surface.53 This hydrogen evolution side reaction also serves to slowly passivate the cathode,53 leading to loss of ECL after roughly 60 minutes. Similar experiments were carried out using tri-n-propylamine (TPrA) as an oxidative coreactant. Under these conditions, BOPEG2 displayed negligible ECL regardless of the concentration of dye or TPrA (Figure 6d). Similarly, no ECL response is observed in the absence of either persulfate or BOPEG dye (Figure 6c).

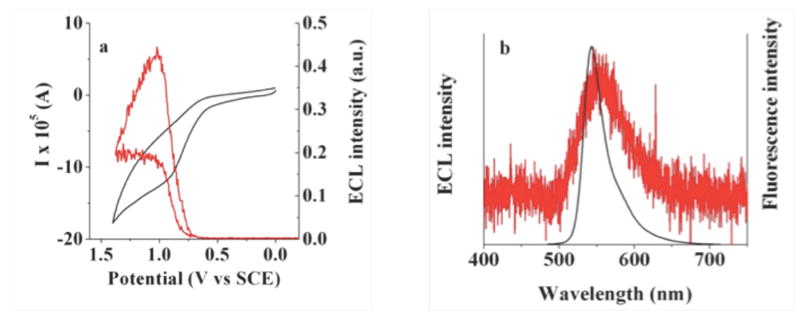

In contrast to the other BOPEG derivatives studied, BOPEG3 displays excellent solubility in water up to millimolar concentrations. This improved solubility in water is due to the extended length of the PEG chain of this derivative, as compared to the relatively short PEG units incorporated into BOPEG1 and BOPEG2. The water solubility imparted by the PEG polymer of BOPEG3 has allowed an investigation of the ECL properties of this derivative in water, without the need for an organic cosolvent. As shown in Figure 7, BOPEG3 displays a notable ECL response in aqueous solutions containing 5mM TPrA as a coreactant that generates a reductant on oxidation. Simultaneous ECL-CV experiments demonstrate that an ECL signal is evident at potentials more positive than ~1.0 V versus SCE (Figure 7a). This response is consistent with the measured potential for formation of BOPEG3•+ at 0.95 V versus SCE (Table 2). Figure 7b overlays the ECL profile obtained for BOPEG3 under these conditions onto the fluorescence spectrum recorded for this water soluble dye. The emission maximum under these conditions is shifted slightly to the red of 550 nm, which is consistent with the recorded fluorescence spectrum (Figure 1d). Accordingly, this marks to first example of ECL recorded for a BODIPY based system under purely aqueous conditions. The strength of the ECL signal displayed by BOPEG3 in water is modest, with a measured ECL efficiency that is roughly 1% of that obtained using Ru(bpy)32+ under analogous conditions. This ECL response is likely limited by the irreversibility of BOPEG3 oxidation, as judged by the voltammograms shown in Figure S3. Nonetheless, the demonstration that properly designed BODIPY derivatives that contain PEG functionalities can be used for ECL in water is noteworthy.

Figure 7.

(a) Simultaneous ECL-CV experiment for an aqueous solution of 1 mM BOPEG3 containing 5 mM TPrA at a scan rate of 1 V/s. The CV trace is shown in black with ECL response in red. (b) ECL spectrum recorded for an aqueous 1 mM solution of BOPEG3 (red) overlaid onto the fluorescence spectrum of the BOPEG dye. A glassy carbon electrode with an area of 0.071 cm2 was used for ECL-CV measurements, while a glassy carbon electrode with area of 0.2 cm2 was employed to record the entire ECL spectrum. For both sets of experiments, 0.2 M NaNO3 was used as the supporting electrolyte and 0.1 M phosphate buffer was employed to maintain a solution pH of 7.0.

SUMMARY AND FUTURE DIRECTIONS

A set of BODIPY derivatives containing water solubilizing PEG chains of varying length have been prepared and studied in detail. These BOPEG systems exhibit photophysical and electrochemical properties that are attenuated by variation of the BODIPY substitution pattern and size of the PEG solubilizing groups. The ability of these constructs to serve as ECL luminophores in aqueous environments has also been gauged. While BOPEG1, which lacks substituents at the 2- and 6-positions of the BODIPY core only functions as an ECL emitter under reductive conditions using BPO as a cosensitizer, BOPEG2 and BOPEG3, which are fully substituted BODIPY derivatives are more versatile.

BOPEG3 is a fully substituted BODIPY derivative that displays excellent water solubility. The electrochemical properties of this compound are well suited for ECL. In the presence of a coreactant, BOPEG3 displays electrogenerated chemiluminescence in water. Although the ECL efficiency of BOPEG3 is modest compared to more commonly employed ruthenium polypyrridyl systems, this study has demonstrated for the first time, that properly constructed BODIPY architectures can serve as ECL probes under aqueous conditions. Given the ease with which the photophysical properties of BODIPY dyes can be tailored via synthetic elaboration of the indacene framework, this work opens the door to the assembly of an array of ECL emitters that span the visible and near-IR regions. Construction of such a library may allow for simultaneous ECL detection of multiple labeled analytes under physiological conditions. It is with this goal in mind that our laboratories are pursuing the elaboration and study of water-soluble BODIPY derivatives.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Financial support for this work was provided to AJB by Roche Diagnostics, Inc., and the Robert A. Welch Foundation (F-0021). Financial support was provided to JR through an Institutional Development Award (IDeA) from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences of the National Institutes of Health under grant number P20GM103541. JR also thanks the University of Delaware for funding, and Oak Ridge Associated Universities for a Ralph E. Powe Junior Faculty Enhancement Award. NMR and other data were acquired at UD using instrumentation obtained with assistance from the NSF and NIH (NSF-MIR 0421224, NSF-CRIF MU CHE-0840401 and CHE-0541775, NIH P20 RR017716).

ABBREVIATIONS

- BPO

benzoyl peroxide

- ECL

electrogenerated chemiluminescence

- PEG

polyethyelene glycol

- SCE

Saturated calomel electrode

- TBAPF6

tetrabutylammonium hexafluorophosphate

- TMAP

tetramethylammonium perchlorate

- TPrA

tri-n-propylamine

Footnotes

Author Contributions

The manuscript was written through contributions of all authors. All authors have given approval to the final version of the manuscript.

Supporting Information Spectroscopic and voltammetric data. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

References

- 1.Loudet A, Burgess K. BODIPY Dyes and Their Derivatives: Syntheses and Spectroscopic Properties. Chem Rev. 2007;107:4891–4932. doi: 10.1021/cr078381n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ziessel R, Ulrich G, Harriman A. The Chemistry of Bodipy: A New El Dorado for Fluorescence Tools. New J Chem. 2007;31:496–501. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Benniston AC, Copley G. Lighting the Way ahead with Boron Dipyrromethene (Bodipy) Dyes. Phys Chem Chem Phys. 2009;11:4124–413. doi: 10.1039/b901383k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kennedy DP, Kosmos CM, Burdette S. FerriBRIGHT: A Rationally Designed Fluorescent Probe for Redox Active Metals. J Am Chem Soc. 2009;131:8578–8586. doi: 10.1021/ja901653u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rosenthal J, Lippard SJ. Direct Detection of Nitroxyl in Aqueous Solution Using a Tripodal Copper(II) BODIPY Complex. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132:5536–5537. doi: 10.1021/ja909148v. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Urano Y, Asanuma D, Hama Y, Koyama Y, Barrett T, Kamiya M, Nagano T, Watanabe T, Hasegawa A, Choyke PL, Kobayashi H. Selective Molecular Imaging of Viable Cancer Cells with pH-Activatable Fluorescence Probes. Nature Medicine. 2009;15:104–109. doi: 10.1038/nm.1854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lee CY, Hupp JT. Dye Sensitized Solar Cells: TiO2 Sensitization with a Bodipy-Porphyrin Antenna System. Langmuir. 2010;26:3760–3765. doi: 10.1021/la9031927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nierth A, Kobitski AY, Nienhaus U, Jäschke A. Anthracene–BODIPY Dyads as Fluorescent Sensors for Biocatalytic Diels–Alder Reactions. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132:2646–2654. doi: 10.1021/ja9084397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Li L, Han J, Nguyen B, Burgess K. Syntheses and Spectral Properties of Functionalized, Water-Soluble BODIPY Derivatives. J Org Chem. 2008;73:1963–1970. doi: 10.1021/jo702463f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Thivierge C, Bandichhor R, Burgess K. Spectral Dispersion and Water Solubilization of BODIPY Dyes via Palladium-Catalyzed C–H Functionalization. Org Lett. 2007;9:2135–2138. doi: 10.1021/ol0706197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Niu SL, Ulrich G, Ziessel R, Kiss A, Renard P–Y, Romieu AA. Spectral Dispersion and Water Solubilization of BODIPY Dyes via Palladium-Catalyzed C–H Functionalization. Org Lett. 2009;11:2049–2052. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bura T, Ziessel R. Water-Soluble Phosphonate-Substituted BODIPY Derivatives with Tunable Emission Channels. Org Lett. 2011;13:3072–3075. doi: 10.1021/ol200969r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhu S, Zhang J, Vegesna G, Luo F–T, Green SA, Liu H. Highly Water-Soluble Neutral BODIPY Dyes with Controllable Fluorescence Quantum Yields. Org Lett. 2011;13:438–441. doi: 10.1021/ol102758z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nepomnyashchii AB, Bard AJ. Electrochemistry and Electrogenerated Chemiluminescence of BODIPY Dyes. Acc Chem Res. 2012;45:1844–1853. doi: 10.1021/ar200278b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yang H, Leland JK, Yost D, Massey RJ. Electrochemiluminescence: A New Diagnostic and Research Tool. Bio/Technology. 1994;12:193–194. doi: 10.1038/nbt0294-193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Elecsys is a registered trademark of a Member of the Roche group

- 17.Kibbey MC, MacAllan D, Karaszkiewicz JW. Novel Electrochemiluminescent Assays for Drug Discovery. J Assoc Lab Automation. 2000;5:45–48. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rubinstein I, Bard AJ. Electrogenerated Chemiluminescence. 37. Aqueous ECL Systems Based on Tris(2,2’-bipyridine)ruthenium(2+) and Oxalate or Organic Acids. J Am Chem Soc. 1981;103:512–516. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Noffsinger JB, Danielson ND. Generation of Chemiluminescence upon Reaction of Aliphatic Amines with Tris(2,2’-bipyridine)ruthenium(III) Anal Chem. 1987;59:865–868. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Leland K, Powell MJ. Electrogenerated Chemiluminescence: An Oxidative-Reduction Type ECL Reaction Sequence Using Tripropyl Amine. J Electrochem Soc. 1990;137:3127–3131. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Miao W, Choi J–P, Bard AJ. Electrogenerated Chemiluminescence 69: The Tris(2,2‘-bipyridine)ruthenium(II), (Ru(bpy)32+)/Tri-n-propylamine (TPrA) System Revisited – A New Route Involving TPrA•+ Cation Radicals. J Am Chem Soc. 2002;124:14478–14475. doi: 10.1021/ja027532v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bruce D, McCall J, Richter MM. Effects of electron withdrawing and donating groups on the efficiency of tris(2,2’-bipyridyl)ruthenium(II)/tri-n-propylamine electrochemiluminescence. Analyst. 2002;127:125–128. doi: 10.1039/b108072p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Richards TM, Bard AJ. Electrogenerated chemiluminescence. 57. Emission from sodium 9,10-diphenylanthracene-2-sulfonate, thianthrenecarboxylic acids, and chlorpromazine in aqueous media. Anal Chem. 1995;67:3140–3147. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Omer KM, Bard AJ. Electrogenerated Chemiluminescence of Aromatic Hydrocarbon Nanoparticles in an Aqueous Solution. J Phys Chem C. 2009;113:11575–11578. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Myung N, Ding Z, Bard AJ. Electrogenerated Chemiluminescence of CdSe Nanocrystals. Nano Lett. 2002;2:1315–1319. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chang Y–Y, Palacios RE, Fan FF, Bard AJ, Barbara PF. Electrogenerated Chemiluminescence of Single Conjugated Polymer Nanoparticles. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:8906–8907. doi: 10.1021/ja803454x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zanarini S, Felici M, Valenti G, Marcaccio M, Prodi L, Bonacchi S, Contreras-Carballada P, Williams RM, Feiters MC, Nolte RJM, et al. Green and Blue Electrochemically Generated Chemiluminescence from Click Chemistry—Customizable Iridium Complexes. Chem Eur J. 2011;17:4640–4647. doi: 10.1002/chem.201002956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chen F-C, Ho J-H, Chen C-Y, Su YO, Ho T-I. Electrogenerated chemiluminescence of sterically hindered porphyrins in aqueous media. J Electroanal Chem. 2001;499:17–23. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rashidnadimi S, Hung TH, Wong K–T, Bard AJ. Electrochemistry and Electrogenerated Chemiluminescence of 3,6-Di(spirobifluorene)-Nphenylcarbazole. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:634–639. doi: 10.1021/ja076033x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Oh J–W, Lee YO, Kim TH, Ko KC, Lee JY, Kim H, Kim JS. Enhancement of Electrogenerated Chemiluminescence and Radical Stability by Peripheral Multidonors on Alkynylpyrene Derivatives. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2009;48:2522–2524. doi: 10.1002/anie.200804669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Omer KM, Ku S–Y, Chen Y–C, Wong K–T, Bard AJ. Electrochemical Behavior and Electrogenerated Chemiluminescence of Star-Shaped D–A Compounds with a 1,3,5-Triazine Core and Substituted Fluorene Arms. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132:10944–10952. doi: 10.1021/ja104160f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shen M, Rodriguez-López J, Huang J, Liu Q, Zhu X–H, Bard AJ. Electrochemistry and Electrogenerated Chemiluminescence of Dithienylbenzothiadiazole Derivative. Differential Reactivity of Donor and Acceptor Groups and Simulations of Radical Cation–Anion and Dication–Radical Anion Annihilations. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132:13453–13461. doi: 10.1021/ja105282u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nepomnyashchii AB, Cho S, Rossky PJ, Bard AJ. Dependence of Electrochemical and Electrogenerated Chemiluminescence Properties on the Structure of BODIPY Dyes. Unusually Large Separation between Sequential Electron Transfers. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132:17550–17559. doi: 10.1021/ja108108d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rosenthal J, Nepomnyashchii AB, Kozhukh J, Bard AJ, Lippard SJ. Synthesis, Photophysics, Electrochemistry, and Electrogenerated Chemiluminescence of a Homologous Set of BODIPY-Appended Bipyridine Derivatives. J Phys Chem C. 2011;115:17993–18001. doi: 10.1021/jp204487r. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sartin MA, Camerel F, Ziessel R, Bard AJ. Electrogenerated Chemiluminescence of B8amide: A BODIPY-Based Molecule with Asymmetric ECL Transients. J Phys Chem C. 2008;112:10833–10841. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nepomnyashchii AB, Bröring M, Ahrens J, Bard AJ. Synthesis, Photophysical, Electrochemical, and Electrogenerated Chemiluminescence Studies. Multiple Sequential Electron Transfers in BODIPY Monomers, Dimers, Trimers, and Polymer. J Am Chem Soc. 2011;133:8633–8645. doi: 10.1021/ja2010219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nepomnyashchii AB, Bröring M, Ahrens J, Krüger R, Bard AJ. Electrochemistry and Electrogenerated Chemiluminescence of n-Pentyl and Phenyl BODIPY Species: Formation of Aggregates from the Radical Ion Annihilation Reaction. J Phys Chem C. 2010;114:14453–14460. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Harris JM, Chess RB. Effect of Pegylation on Pharmaceuticals. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2003;2:214–221. doi: 10.1038/nrd1033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Latham AW, Williams ME. Versatile Routes toward Functional, Water-Soluble Nanoparticles via Trifluoroethylester–PEG–Thiol Ligands. Langmuir. 2006;22:4319–4326. doi: 10.1021/la053523z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Monfardini C, Veronese FM. Stabilization of Substances in Circulation. Bioconjugate Chem. 1998;9:418–450. doi: 10.1021/bc970184f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zhao Y, Wang W, Wu F, Zhou Y, Huang N, Gu Y, Zoua Q, Yanga W. Polyethylene Glycol-Functionalized Benzylidene Cyclopentanone Dyes for Two-Photon Excited Photodynamic Therapy. Org Biomol Chem. 2011;9:4168–4175. doi: 10.1039/c0ob01278e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pangborn AB, Giardello MA, Grubbs RH, Rosen RK, Timmers FJ. Safe and Convenient Procedure for Solvent Purification. Organometallics. 1996;15:1518–1520. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gentilini C, Boccalon M, Pasquato L. Straightforward Synthesis of Fluorinated Amphiphilic Thiols. Eur J Org Chem. 2008;19:3308–3313. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sahami S, Weaver M. Entropic and Enthalpic Contributions to the Solvent Dependence of the Thermodynamics of Transition-Metal Redox Couples: Part I. Couples Containing Aromatic Ligands. J Electroanal Chem. 1981;122:155–170. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Chen C-W, Luh T-Y. J Elimination of β-Thioalkoxy Alcohols under Mitsunobu Conditions. A New Synthesis of Conjugated Enynes from Propargylic Dithioacetals. Org Chem. 2008;73:8357–8363. doi: 10.1021/jo8013885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yun W, Li S, Wang B, Chen L. Solid-Phase Synthesis of Diaryl Ketones Through a Three-Component Stille Coupling Reaction. Tett Lett. 2001;42:175–177. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Nepomnyashchii AB, Bröring M, Ahrens J, Bard AJ. Chemical and Electrochemical Dimerization of BODIPY Compounds: Electrogenerated Chemiluminescent Detection of Dimer Formation. J Am Chem Soc. 2011;133:19498–19504. doi: 10.1021/ja207545t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Nadjo L, Saveaunt JM. Electrodimerization: VIII. Role of Proton Transfer Reactions in the Mechanism of Electrohydrodimerization Formal Kinetics for Voltammetric Studies (Linear Sweep, Rotating Disc, Polarography) J Electroanal Chem. 1973;44:327–366. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Debad JD, Morris JC, Magnus P, Bard AJ. Anodic Coupling of Diphenylbenzo[k]fluoranthene: Mechanistic and Kinetic Studies Utilizing Cyclic Voltammetry and Electrogenerated Chemiluminescence. J Org Chem. 1997;62:530–537. doi: 10.1021/jo961448e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Chandross EA, Sonntag FI. Chemiluminescent Electron-Transfer Reactions of Radical Anions. J Am Chem Soc. 1966;88:1089–1096. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Akins DL, Birke RL. Energy Transfer in Reactions F Electrogenerated Aromatic Anions and Benzoyl Peroxide. Chemiluminescence and its Mechanism. Chem Phys Lett. 1974;29:428–435. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Santa Cruz TD, Akins DL, Birke RL. Chemiluminescence and Energy Transfer in Systems of Electrogenerated Aromatic Anions and Benzoyl Peroxide. J Am Chem Soc. 1976;98:1677–1682. [Google Scholar]

- 53.White HS, Bard AJ. Electrogenerated Chemiluminescence. 41. Electrogenerated Chemiluminescence and Chemiluminescence of the Ru(2,2- bpy)32+-S2O82- System in Acetonitrile-Water Solutions. J Am Chem Soc. 1982;104:6891–6895. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.