Abstract

Background And Objectives

The purpose of our studies was to determine the effects of extended platelet storage on post-storage platelet viability.

Materials and Methods

Normal subjects were recruited to donate platelets using two different apheresis systems: either the COBE Spectra (n=58) or the Haemonetics MCS+ (n=84). Platelet recovery and survival data from the two systems were compared to each other and to in vitro measurements of the stored platelets.

Results

There were no significant differences in either platelet recoveries or survivals between the two machines between 1 and 8 days of storage. Combining the data from both machines, platelet recoveries decreased by 2.6% and survivals by 0.3 days/storage day. In vitro assays did not predict either platelet recoveries or survivals during storage for 5 to 8 days. After 9 days of storage, pH’s were unacceptable (≤6.1), suggesting that 8 days will be the longest possible storage time.

Conclusions

These data suggest that, if stored platelet bacterial contamination issues are resolved, significant extension of platelet storage times is possible.

Keywords: Platelets, Platelet Storage, Apheresis Platelets

INTRODUCTION

Currently, platelet storage time in the U,S. is limited to 5 days because of concerns about bacterial overgrowth with extended storage. However, some other countries allow storage for up to 7 days with bacterial screening or pathogen-reduction technologies. It is anticipated that better bacterial detection systems than presently available(1) or pathogen reduction methods(2,3) may permit extension of platelet storage times. Certainly, in the past, between 1984 and 1986, platelets could be stored for up to 7 days. Recently, the FDA allowed apheresis platelets to, again, be stored for 7 days with the stipulation that any platelets that were not transfused by day 7 would be re-cultured. When 2 out of 2,571 collections grew bacteria on a re-cultured sample, the study was stopped by the study sponsors, and platelet storage times were returned to 5 days or less.(4) The data reported here were obtained from 142 autologous platelet storage studies performed over six years. These data permitted the assessment of several platelet storage outcomes; 1) how long autologous apheresis platelets can be stored in plasma without resulting in unacceptable post-storage viability; 2) how platelet viability changes over storage time; 3) evaluate which, if any, of the in vitro measures of platelet quality correlate with post-transfusion platelet recovery or survival measurements; 4) assess these measurements using two different apheresis systems; and 5) determine the correlations between the in vivo storage results of the two apheresis systems.

METHODS

Experimental Design

Two different apheresis systems – the COBE Spectra (COBE® Spectra Apheresis System; CaridianBCT, Inc., Lakewood, CO), and the Haemonetics MCS+ (Haemonetics Corporation, Braintree, MA) were used in these studies according to the manufacturers’ directions. The anticoagulant-to-whole blood ratio used during the apheresis collections for Haemonetics was 1 to 9 and, for Caridian Spectra, was 1 to 8. After the apheresis platelets were collected, they were separated equally into two storage bags. The storage bags for Haemonetics collection was a 1000 ml bag composed of CLX bag [Cutter 5025 PVC with plasticizer (MCS+ List No. 994)], and, for Caridian, it was a 1000 ml bag [COBE ELP platelet bag PVC with citrate plasticizer (Gambro, BCT) Spectra, Dual Needle LRS]. The platelets were stored in a Helmer incubator (Helmer Corporation; Fort Wayne, IN) at 22 ± 2°C with constant flatbed agitation at 70 cycles per minute.

To evaluate the effect of apheresis platelet storage time on autologous platelet recoveries and survivals, we compiled the data presented in this manuscript from past studies. Hence, some subjects provided more than one observation to our data set depending on the nature and objective of the original study. However, subjects did not participate in a given study more than once. The data set has a total of 142 observations from 107 different subjects, using the COBE system for 58 collections and the Haemonetics MCS+ for 84. The apheresis collections were performed over a six-year period between 09/28/2000 and 09/27/2006.

Platelet Radiolabeling

At the end of the selected storage time, a 43 ml aliquot from the apheresis platelets was labeled with either 51Cr or 111In. Labeling was performed using established techniques.(5) Blood samples were drawn from the donor before, within 2 hours, and on days 1, 2, 3, 4 or 5, and 7 or 8 or 9 after transfusion to test for radioactivity bound to platelets using an Auto-Gamma Counter (Model 5530; Packard Instruments, Meridian, CT). Platelet recoveries and survivals were calculated using the COST program.(6) The radiolabeled data were corrected for neither potential elution of the label nor for possible isotope bound to red blood cells.

In Vitro Platelet Measurements

Platelet counts were performed on the day following collection and after storage using an ABX Hematology Analyzer (ABX Diagnostics; Irvine, CA). After storage, several in vitro measurements of platelet quality were performed on most, but not all of the platelets collected; i.e., pH was measured and is reported at 37°C using a blood gas analyzer machine [Bayer Model 248 Blood Gas Analyzer; Bayer Diagnostics (Seimens), East Walpole, MA], extent of shape change (ESC), and hypotonic shock response (HSR),(7) Annexin V binding using a kit from Molecular Probes (Eugene, OR), morphology score,(8) and mean platelet volume (MPV). Both the ESC and HSR assays were performed using a chrono-log whole blood aggregometer (Chrono-Log Model 500-Ca; Havertown, PA) to measure the response photometrically. Annexin V binds to phosphatidyl serine in the presence of calcium and is an indicator of apoptosis. Annexin V is fluorescently labeled with Alexa Fluor 488 to allow its detection using a FACSCAN (Becton Dickinson; San Jose, CA).

Statistical Methods

We present a retrospective analysis of data compiled from previous studies. Since results from both storage bags from an apheresis collection from some studies are included in the data set, not all observations are independent. Hence, we could not compare group means using t-tests. We fit linear mixed effects (LME) models to the data which include independent random subject effects and account for the lack of independence between some observations. Several different LME models have been fit to the data to evaluate specific hypotheses. The results presented in Table 1 are based on a LME in which the fixed effects are apheresis system x storage interval subclass means. The p values presented are from hypothesis tests of comparisons made between these fixed effects. For example, the p value for the comparison of platelet recovery from the Haemonetics 8-day platelets to COBE 8-day platelets is based on a hypothesis test that the difference between the LME model fixed effects for Haemonetics 8-day platelets and COBE 8-day platelets is equal to zero. To evaluate whether recovery and survival change as storage interval increases, we fit a LME model to both recovery and survival which includes a fixed slope term for the storage interval covariate and the random subject effects. For both recovery and survival, we test the hypothesis that the slope parameter (regression coefficient) for storage interval is equal to zero, i.e., that recovery or survival do not depend on how long the platelets have been stored. LME models were fit and hypothesis tests of model parameters were evaluated using the nlme package of the R statistical language.(9)

TABLE 1.

IN VIVO RECOVERIES AND SURVIVALS OF AUTOLOGOUS PLASMA STORED HAEMONETICS MCS+ AND COBE SPECTRA APHERESIS PLATELETS

| Storage Time (Days) |

Apheresis System | N | Platelet Recovery (%) |

Platelet Survival (Days) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Haemonetics MCS+ | 39 | 66 ± 2 | 7.2 ± 0.3 |

| COBE Spectra | 14 | 66 ± 3 | 7.7 ± 0.4 | |

| p = 0.92 | p = 0.27 | |||

| 5 | Haemonetics MCS+ | 7 | 59 ± 5 | 6.2 ± 0.7 |

| COBE Spectra | 12 | 55 ± 4 | 6.4 ± 0.5 | |

| p = 0.54 | p = 0.87 | |||

| 7 | Haemonetics MCS+ | 16 | 42 ± 3 | 4.9 ± 0.4 |

| COBE Spectra | 9 | 52 ± 5 | 4.8 ± 0.7 | |

| p = 0.09 | p = 0.97 | |||

| 8 | Haemonetics MCS+ | 20 | 47 ± 3 | 5.8 ± 0.4 |

| COBE Spectra | 20 | 47 ± 3 | 5.1 ± 0.4 | |

| p = 0.97 | p = 0.25 | |||

| 9 | Haemonetics MCS+ | 2 | 42 ± 6 | 2.3 ± 1.2 |

| COBE Spectra | 3 | 49 ± 5 | 3.0 ± 1.0 | |

| p = 0.42 | p = 0.66 |

Data given are estimates of the LME model parameters ±1 S.E. All p values are for contrasts between the LME model parameters for Haemonetics MCS+ and COBE Spectra at the same storage interval.

Descriptive results for in vitro variables in Table 2 are presented as means and standard deviations. Numbers of observations vary from variable to variable as not all assays were conducted during all the studies, and some units did not have samples drawn for in vitro evaluation. No p values are presented as they would be dependent on the number of observations available and not just the underlying associations or effects. Assessment of associations between in vivo and in vitro variables were done by fitting LMEs to recovery and survival where one or more in vitro assays were included as fixed covariates. Percentages of variability explained were determined by calculating an R2 statistic for linear mixed effect models(10) and are presented for descriptive purposes.

TABLE 2.

IN VITRO ASSAYS OF PLASMA STORED HAEMONETICS AND COBE SPECTRA APHERESIS PLATELETS

| Storage Time (Days) |

Apheresis System | N | Donor’s Platelet Count/μl (x 103) |

Unit Volume (mls) |

Total Platelet Count of Unit (x 1011) | MPV (fL)* | Morphology Score |

Annexin V Binding (%) |

ESC (%)** | HSR (%)*** |

pH | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Day 1 | End of Storage | |||||||||||

| 1 | Haemonetics MCS+ | 39 | 235 ± 49 | 151 ± 21 | 2.63 ± 0.43 | ND | 6.3 ± 0.7 | 355 ± 28 | 7 ± 2 | 24 ± 5 | 89 ± 11 | 7.3 ± 0.1 |

| COBE Spectra | 14 | 239 ± 36 | 162 ± 22 | 2.85 ± 0.61 | ND | 5.9 ± 0.8 | 341 ± 32 | 7± 4 | 21 ± 3 | 79 ± 10 | 7.5 ± 0.2 | |

| 5 | Haemonetics MCS+ | 7 | 245 ± 30 | 143 ± 27 | ND | 2.38 ± 0.48 | ND | 248 ± 57 | 14 ± 3 | 26 ± 4 | 75 ± 13 | 7.1 ± 0.1 |

| COBE Spectra | 12 | 242 ± 83 | 245 ± 61 | 2.11 ± 1.04 | 2.16 ± 0.89 | ND | 333 ± 56 | 13 ± 3 | 21 ± 12 | 63 ± 15 | 7.5 ± 0.3 | |

| 7 | Haemonetics MCS+ | 16 | 241 ± 53 | 188 ± 33 | 4.04 ± 0.60 | 3.19 ± 0.92 | 7.0 ± 0.4 | 263 ± 62 | 18 ± 13 | 17 ± 3 | 67 ± 15 | 7.1 ± 0.8 |

| COBE Spectra | 9 | 234 ± 45 | 249 ± 47 | ND | 2.39 ± 0.93 | ND | 243 ± 28 | 16 ± 6 | 11 ± 1 | 47 ± 8 | 7.2 ± 0.1 | |

| 8 | Haemonetics MCS+ | 18 | 218 ± 50 | 176 ± 32 | 2.84 ± 0.83 | 2.75 ± 0.76 | 6.8 ± 0.8 | 267 ± 49 | 24 ± 24 | 16 ± 2 | 76 ± 11 | 7.0 ± 0.3 |

| COBE Spectra | 19 | 231 ± 46 | 193 ± 55 | 2.91 ± 0.33 | 3.06 ± 0.63 | 6.6 ± 0.8 | 289 ± 47 | 17 ± 4 | 13 ± 5 | 55 ± 11 | 7.0 ± 0.2 | |

| 9 | Haemonetics MCS+ | 2 | 265 ± 2 | 167 ± 0 | ND | 2.54 ± 0.06 | 5.8 ± 0.4 | 225 ± 35 | 34 ± 23 | 10 ± 13 | 41 ± 47 | 6.3 ± 0.8 |

| COBE | 3 | 255 ± 55 | 174 ± 39 | 2.91 ± 0.95 | 3.26 ± 1.23 | 6.9 ± 1.3 | 250 ± 50 | 26 ± 10 | 6 ± 8 | 49 ± 26 | 6.7 ± 0.5 | |

MPV = Mean platelet volume.

ESC = Extent of shape change.

HSR = Hypotonic shock response.

ND = Not done.

The data presented in the table are means ± S.D.

RESULTS

In Vivo Results

Data from the stored platelet studies are given in Table 1. There were no differences between the systems regardless of storage time. After 9 days of storage, one of the two 9-day stored Haemonetics collected platelets had a post-storage pH of 5.8, and one of three 9-day stored COBE Spectra platelets had a post-storage pH of 6.1 with platelet recoveries of 36% and 23% and survivals of 1.1 and 1.5 days, respectively. These collections, as with all of the other collections, were within the bag parameters for volume, platelet concentration, and total platelet content established by the manufacturers. These results indicate that 8 days will be the maximum permissible storage time for Haemonetics MCS+ and COBE Spectra collected apheresis platelets when stored in plasma.

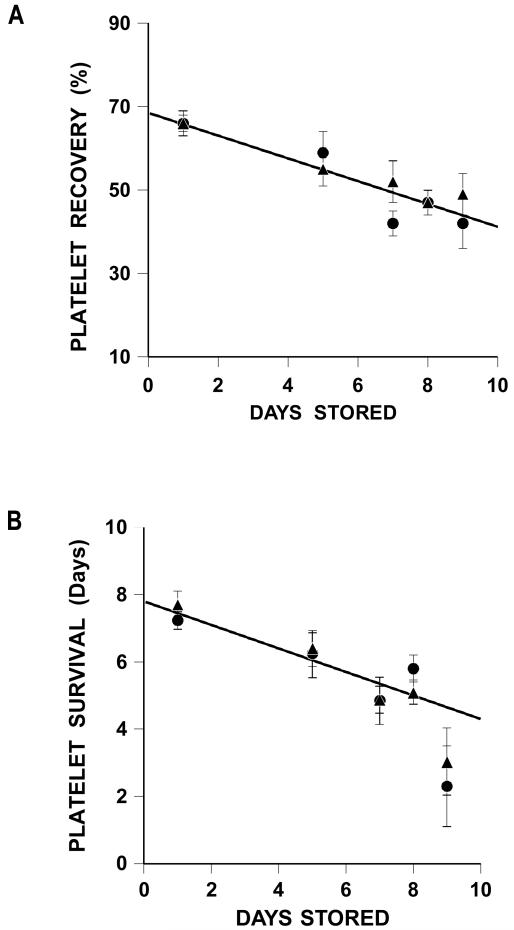

There were progressive decreases in both platelet recoveries and survivals over storage time (Figure 1A and 1B). Because there were no differences between the platelet recovery and survival data for the two systems, the data for both apheresis systems and all storage intervals between 1 and 8 days were combined to fit regression models to the data. The decrease in platelet recovery was estimated as 2.7% per day stored, while the decrease in platelet survival was estimated as 0.3 days per day stored (R2 = 0.40(10), p<0.001 and R2 = 0.25, p<0.001, respectively).

Figure 1.

Recoveries and Survivals of Stored Apheresis Platelets.

A Recoveries of COBE Spectra and Haemonetics stored platelets for 1 to 9 days.

Regression line is for combined 1- to 8-day stored COBE Spectra and Haemonetics recoveries (%) = 67 – 2.6 × days stored (p<0.001), R2=0.40.

B Survivals of COBE Spectra and Haemonetics stored platelets for 1 to 9 days.

Regression line is for combined 1- to 8-day stored COBE Spectra and Haemonetics survivals (days) = 7.7 – 0.3 × days stored (p<0.001), R2=0.25.

Data for COBE Spectra stored platelets are given as triangles (▲) and for Haemonetics stored platelets as circles (●). Data are given as average ±1 S.E.

In Vitro Results

The in vitro results for the stored platelets are given in Table 2. Pre- and post-storage platelet counts remained stable. Over storage time, there were progressive increases in MPV and Annexin V binding with decreases in morphology score, ESC, HSR and pH.

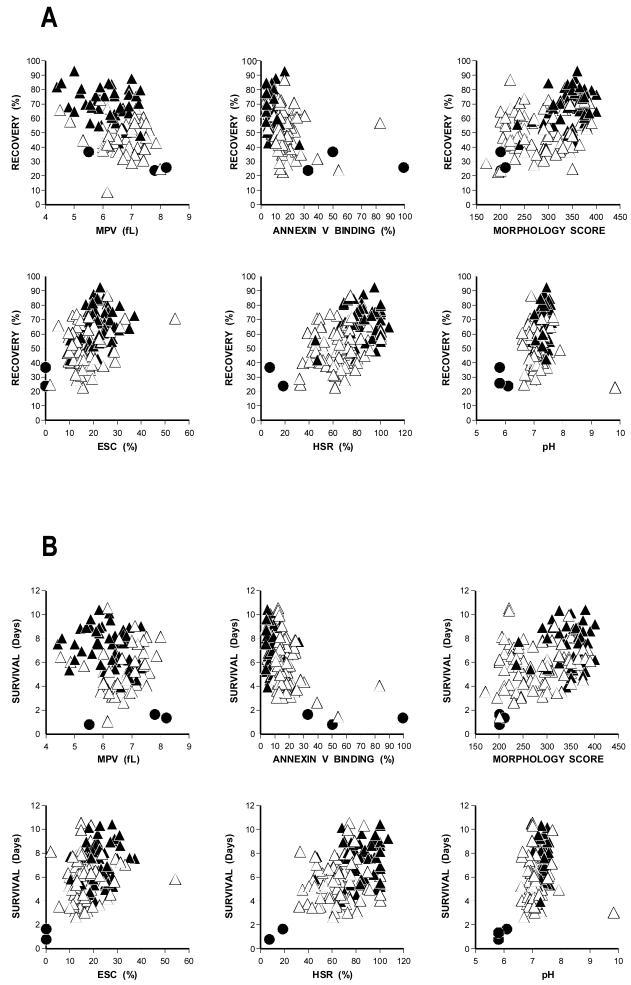

Analysis of associations between each in vivo variable and individual in vitro variables indicate that there are statistically significant correlations between recovery and ESC, HSR, Annexin V binding, and morphology score and between survival and HSR, Annexin V binding and morphology score when all products are included in the analyses (Figures 2A and 2B, respectively). Multivariable analyses of the associations between the in vivo and in vitro measures done using step-wise fitting of MLE models indicate that pH, morphology score, HSR and Annexin V binding together can explain about 44% of the variability(10) in platelet recovery and that HSR and Annexin V binding can explain about 17% of the variability in platelet survival. However, if the analyses are restricted to products stored more than 1 day, none of the associations remain statistically significant and the percentages of variability explained by the same predictors’ drops to 10% and 2%, respectively.

Figure 2.

In Vivo Platelet Recoveries And Survivals Versus Post-Storage In Vitro Measurements.

A Platelet Recoveries Versus In Vitro Data.

B Platelet Survivals Versus In Vitro Data.

All in vivo data for platelet recoveries and survivals from 1 day to 9 day data are plotted against end of storage mean platelet volume (MPV), Annexin V binding, Morphology Score, Extent of Shape Change (ESC), Hypotonic Shock Response (HSR), and pH measured at 37°C. Day 1 data are shown as closed triangles (▲), 5 to 9 day storage data as open triangles (△), and the three storage studies with pH values of ≤6.2 are shown as closed circles (●).

DISCUSSION

Our laboratory has evaluated autologous radiolabeled platelet recovery and survival measurements of a variety of platelet products over the years. Therefore, we have accumulated a substantial number of apheresis collections on two different apheresis systems over storage times of 1 to 9 days which have allowed us to assess changes in platelet viability during storage. In contrast, most other studies have only reported results for a single storage time.

As expected, there were progressive decreases in both platelet recoveries and survivals with increasing storage time that were similar between the two systems (Figures 1A and 1B, respectively). Because there were no significant differences between the platelet recovery and survival results for any storage interval between the two systems, we were able to combine the data from both systems. Platelet recoveries decreased by 2.7% a day between 1 and 8 days of storage, while platelet survivals decreased by 0.3 days per day of storage. This indicates that platelet viability is well maintained during storage until 9 days when viability is lost in 2/5 (40%) of the products due to low pHs. Our results evaluating extended storage of apheresis platelets in plasma are comparable to those reported by ourselves and others.(11-16)

In vitro measurements of pH, MPV, Annexin V binding, morphology score, HSR, and ESC were performed on most units at the end of storage (Table 2). The relationship between these in vitro parameters and in vivo platelet recovery and survival results are shown in Figures 2A and 2B, respectively. The data show that there are statistically-significant relationships between platelet recoveries and ESC, HSR, Annexin V binding, and morphology score and between platelet survivals and HSR, Annexin V binding, and morphology score when all products were included. However, when the in vitro results for the platelets stored for 1 day were removed from the analyses, there is no longer any association between any of these measurements and units stored between 5 to 9 days. This is likely related to the increased variability of the in vitro variables at storage times of 5 to 9 days relative to the variability of in vitro variables at 1 day. Furthermore, low pH values of 6.2 or less consistently identify poor quality units better than any other assay in our studies as well as by others.(17) The failure of in vitro assays to predict in vivo results has been a fairly consistent finding over the years.(reviewed in Ref.18) Part of this may be related to the observations that, by adding fresh plasma to stored platelets, the results of the in vitro assays are improved,(19,20) and this correlates with similar findings when stored platelets are re-tested following transfusion.(20-24) Unfortunately, within the known range of acceptable post-storage platelet quality, none of these assays are able to identify platelets at the low end of the acceptable range from those at the high end.

There are several problems with our studies. First of all, the data are retrospective and were accumulated over six years. However, they were all performed in the same laboratory and by the same staff which lends internal consistency to the data. In addition, the observation that similar platelet recovery and survival results were achieved with two different apheresis systems when platelets were stored for the same time, as well as the large number of observations, improves the reliability of the results. However, the current method of radiolabeling was not used as our studies pre-dated this newer method.(25) The newer method allows for determination of elution of the label and detection of radiolabeled red cells. Both of these factors may sometimes prevent accurate determination of both platelet recoveries and survivals. Also, radiolabeled fresh platelet controls from the same donor were not collected for comparison with the stored results.(26) Therefore, we cannot determine from our studies how long the platelets may be stored and still meet the United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) criteria for the quality of platelets at the end of storage. The FDA requires that, at the end of storage, the lower 95% confidence limits for radiolabeled autologous normal subjects’ recoveries should be ≥66% and that survivals should be ≥58% of fresh.(26) However, methods to better detect or inactivate bacteria will be required before the FDA will allow storage of platelets beyond the five days currently licensed in the U.S.(27)

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

All of the authors have made substantial contributions to the research design, acquisition, analysis, and interpretation of the data, as well as drafting, revising, and review of the submitted manuscript.

The authors are indebted to the Haemonetics and COBE Corporations who supplied the apheresis systems and collection kits that were used in these studies.

The authors gratefully acknowledge the excellent administrative assistance of Ginny Knight in the preparation of this manuscript.

Supported By: National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute, National Institutes of Health grant P50 HL081015.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: The authors certify that they have no affiliation with or financial involvement in any organization or entity with a direct financial interest in the subject matter or materials discussed in this manuscript.

Disclaimers: S.J. Slichter: None

D. Bolgiano: None

J. Corson: None

T. Christoffel: None

M.K. Jones: None

E. Pellham: None

Competing Interests: The authors certify that they have no competing interests.

REFERENCES

- 1.Koopman MMW, van Ende E, Kieshout-Krikke R, et al. Bacterial screening of platelet concentrates: Results of 2 years active surveillance of transfused positive cultured units released as negative to date. Vox Sang. 2009;97:355–357. doi: 10.1111/j.1423-0410.2009.01221.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lin L, Cook DN, Wiesehahn GP, et al. Photochemical inactivation of viruses and bacteria in platelet concentrates by use of a novel psoralen and long-wave length ultraviolet light. Transfusion. 1997;37:423–435. doi: 10.1046/j.1537-2995.1997.37497265344.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ruanne PH, Edrich R, Gampp D, et al. Photochemical inactivation of selected viruses and bacteria in platelet concentrates using riboflavin and light. Transfusion. 2004;44:877–885. doi: 10.1111/j.1537-2995.2004.03355.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kleinman S, Dumont LJ, Tomasulo P, et al. The impact of discontinuation of 7-day storage of apheresis platelets (PASSPORT) on recipient safety: An illustration of the need for proper risk assessments. Transfusion. 2009;49:903–912. doi: 10.1111/j.1537-2995.2008.02048.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Snyder EL, Moroff G, Simon T, et al. Recommended methods for conducting radiolabeled platelet survival studies. Transfusion. 1986;26:37–42. doi: 10.1046/j.1537-2995.1986.26186124029.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lotter MG, Rabe WL, Van Zyl JM, et al. A computer program in compiled BASIC for the IBM personal computer to calculate the mean platelet survival time with the multiple hit and weighted mean methods. Comput Biol Med. 1988;18:305–315. doi: 10.1016/0010-4825(88)90006-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Holme S, Moroff G, Murphy S. A multi-laboratory evaluation of in vitro platelet assays: The tests for extent of shape change and response to hypotonic shock. Biomedical Excellence for Safer Transfusion Working Party of the International Society of Blood Transfusion. Transfusion. 1998;38:31–40. doi: 10.1046/j.1537-2995.1998.38198141495.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kunicki TJ, Tuccelli M, Becker GA, et al. A study of variables affecting the quality of platelets stored at “room temperature.”. Transfusion. 1975;15:414–421. doi: 10.1046/j.1537-2995.1975.15576082215.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. R Core Team R Foundation for Statistical Computing. 2012 http://www.R-project.org.

- 10.Kramer M. R2 Statistics for Mixed Models; Presented at the 17th Annual Kansas State University Conference on Applied Statistics in Agriculture; Manhattan, Kansas. 24–26 April 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 11.AuBuchon JP, Herschel L, Roger J. Further evaluation of a new standard of efficacy for stored platelets. Transfusion. 2005;45:1143–1150. doi: 10.1111/j.1537-2995.2005.00177.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ezuki S, Kanno T, Ohto H, et al. Survival and recovery of apheresis platelets stored in a polyolefin container with high oxygen permeability. Vox Sang. 2008;94:292–298. doi: 10.1111/j.1423-0410.2008.01042.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Slichter SJ, Bolgiano D, Jones MK, et al. Viability and function of 8-day stored apheresis platelets. Transfusion. 2006;46(10):1763–1769. doi: 10.1111/j.1537-2995.2006.00970.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cardigan R, Williamson LM. The quality of platelets after storage for 7 days. Transfus Med. 2003;13:173–187. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3148.2003.00449.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dumont LJ, AuBuchon JP, Whitley P, et al. Seven-day storage of single-donor platelets: recovery and survival in an autologous transfusion study. Transfusion. 2002;42:847–854. doi: 10.1046/j.1537-2995.2002.00147.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vassallo RR, Murphy S, Einarson M, et al. Evaluation of platelets stored for 8 days in PL2410 containers. Transfusion. 2004;44(Suppl):28A. Abstract. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rudderow D, Soslau G. Permanent lesions of stored platelets correlate to pH and cell count while reversible lesions do not. Proc Soc Exp Biol Med. 1998;217:219–227. doi: 10.3181/00379727-217-44226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rinder HM, Smith BR. In vitro evaluation of stored platelets: Is there hope for predicting posttransfusion platelet survival and function? (Editorial) Transfusion. 2003;43:2–6. doi: 10.1046/j.1537-2995.2003.00261.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mondoro TH, Shafer BC, Vostal JG. Restoration of in vitro response in platelets stored in plasma. Am J Clin Pathol. 1999;111:693–699. doi: 10.1093/ajcp/111.5.693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rinder HM, Snyder EL, Tracey JB, et al. Reversibility of severe metabolic stress in stored platelets after in vitro plasma rescue or in vivo transfusion: restoration of secretory function and maintenance of platelet survival. Transfusion. 2003;43:1230–1237. doi: 10.1046/j.1537-2995.2003.00484.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Holme S. Storage and quality assessment of platelets. Vox Sang. 1998;74(Suppl 2):207–216. doi: 10.1111/j.1423-0410.1998.tb05422.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Brubaker DB, Marcus C, Holmes E. Intravascular and total body platelet equilibrium in healthy volunteers and in thrombocytopenic patients transfused with single donor platelets. Am J Hematol. 1998;58:165–176. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-8652(199807)58:3<165::aid-ajh2>3.0.co;2-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Miyaji R, Sakai M, Urano H, et al. Decreased platelet aggregation of platelet concentrate during storage recovers in the body after transfusion. Transfusion. 2004;44:891–899. doi: 10.1111/j.1537-2995.2004.03214.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rosenfeld BA, Herfel B, Faraday N, et al. Effects of storage time on quantitative and qualitative platelet function after transfusion. Anesthesiology. 1995;83:1167–1172. doi: 10.1097/00000542-199512000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.The Biomedical Excellence for Safer Transfusion (BEST) Collaborative: Platelet radiolabeling procedure. Transfusion. 2006;46:59S–66S. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Vostal JG. Efficiency evaluation of current and future platelet transfusion products. J Trauma. 2006;6(Suppl):S78–S82. doi: 10.1097/01.ta.0000199921.40502.5d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kleinman S, Dumont LJ, Tomasulo P, et al. The impact of discontinuation of 7-day storage of apheresis platelets (PASSPORT) on recipient safety: An illustration of the need for proper risk assessments. Transfusion. 2009;49:903–912. doi: 10.1111/j.1537-2995.2008.02048.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]