Abstract

Background

Adjuvant endocrine therapy for breast cancer reduces recurrence and improves survival rates. Many patients never start treatment or discontinue prematurely. A better understanding of factors associated with endocrine therapy initiation and persistence could inform practitioners how to support patients.

Methods

We analyzed data from a longitudinal study of 2,268 women diagnosed with breast cancer and reported to the Metropolitan Detroit and Los Angeles SEER cancer registries in 2005-2007. Patients were surveyed approximately both 9 months and 4 years after diagnosis. At 4-years, patients were asked if they had initiated endocrine therapy, terminated therapy, or were currently taking therapy (defined as persistence). Multivariable logistic regression models examined factors associated with initiation and persistence.

Results

Of the 743 patients eligible for endocrine therapy, 80 (10.8%) never initiated therapy, 112 (15.1%) started therapy but discontinued prematurely, and 551 (74.2%) continued use at the second time point. Compared with whites, Latinas (OR 2.80, 95% CI 1.08-7.23) and black women (OR 3.63, 95% CI 1.22-10.78) were more likely to initiate therapy. Other factors associated with initiation included worry about recurrence (OR 3.54, 95% CI 1.31 – 9.56) and inadequate information about side effects (OR 0.24, 95% CI 0.10 – 0.55). Factors associated with persistence included two or more medications taken weekly (OR 4.19, 95% CI 2.28-7.68) and increased age (OR 0.98, 95% CI 0.95-0.99).

Conclusions

Enhanced patient education about potential side effects and the effectiveness of adjuvant endocrine therapy in improving outcomes may improve initiation and persistence rates and optimize breast cancer survival.

Keywords: breast neoplasms, aromatase inhibitors, Selective Estrogen Receptor Modulators, medication taking, health services research

Introduction

Adjuvant endocrine therapy for invasive breast cancer has well-established benefits in reducing recurrence and improving survival. Tamoxifen [1] and aromatase inhibitors [2] reduce mortality and longer duration of therapy provides greater benefit versus shorter duration [1, 3-5]. Despite this, not all eligible patients initiate (ever take) or persist with (defined as completing a prescribed course of clinically indicated) endocrine therapy [6-9].

The favorable efficacy data have culminated in clinical practice guidelines that recommend five years of adjuvant endocrine therapy – tamoxifen and, in postmenopausal women, aromatase inhibitors or sequential therapy with both tamoxifen and aromatase inhibitors for all women who have a hormone receptor-positive tumor over 1 centimeter [10-12]. Two clinical trials recently documented efficacy when endocrine therapy was extended to ten years [13-14]. These data may encourage clinicians to prescribe therapy beyond the current five year recommendation. Common side effects of all agents include hot flashes and vaginal discharge or dryness. Serious side effects, such as thromboembolism and uterine cancer, have been reported with tamoxifen. Although the aromatase inhibitors are generally well-tolerated[15], their use can cause loss of bone mineral density and arthralgias[16].

Initiation of treatment and persistence remains a continuing challenge to clinicians. While rates of guideline-concordant prescribing of adjuvant hormonal therapy are high[17-19], a number of studies have documented that long term persistence with prescribed endocrine therapy for breast cancer is alarmingly low [6-9, 20-26]. Between 33% and 40% of patients terminate therapy before the recommended five-year period, a discontinuation rate that is substantively higher than that reported in clinical trials [27]. The high termination rate is consistent, however, with studies of medication use for other chronic conditions [28-29]. Chronic care researchers have proposed several factors that may influence with suboptimal use of endocrine therapy. Patient attributes such as older age, greater uncertainty about the marginal benefit of treatment, clinical indication for treatment, and more comorbid conditions have been associated with lower persistence, as have side-effects from therapy [21-22, 30] and higher out-of-pocket costs [31-33].

There are noteworthy gaps in our understanding of adjuvant endocrine therapy initiation and persistence. These include a lack of studies investigating endocrine therapy use in populations not identified through clinical trials, convenience samples, or enrolled in specific health plans, the absence of data obtained directly from patients, and a reliance on cross-sectional designs. To address these gaps, we examined data on factors associated with endocrine therapy initiation and persistence in women diagnosed with invasive breast cancer, selected from two SEER (Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results) population-based cancer registries in the US, who participated in a longitudinal study.

Methods

Study Sample and Data Collection

Our sampling strategy has been reported previously [34]. Women who lived in Los Angeles county or the Detroit metropolitan area who were between 20-79 years of age, diagnosed with AJCC stages I-III breast cancer or ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS) between June 2005 and February 2007, and reported to the Los Angeles County and Metropolitan Detroit SEER tumor registries were eligible to participate. The recruitment strategy included a 20% random sample of non-Hispanic whites, all eligible black patients in Detroit and Los Angeles, and all eligible Latinas in Los Angeles. We did not survey Asian women in Los Angeles due to a concurrent study in that population. We excluded women with diagnoses of inflammatory breast cancer or metastatic disease at presentation, women for whom we did not have race/ethnicity information, and women who could not complete a questionnaire in English or Spanish. The final analyses included only women with invasive disease that was estrogen or progesterone receptive positive. We excluded women who were too ill or incompetent or whose doctor refused permission to contact the participant. We obtained a 73.1% response rate [34].

We used a modified version of the Dillman survey method to maximize response rates, which involved intensive telephone follow-up, second mailings of materials, and phone interviews when required [35]. Women were surveyed at two points in time: a baseline survey approximately 9 months after diagnosis (range of 5 to 14 months after diagnosis) and a follow up survey approximately 4 years later (range of 36 to 65 months after initial diagnosis). After physician notification of our intention to contact their patients, we mailed eligible patients a recruitment letter, questionnaire, and a $10 cash gift. Non-responders received a postcard reminder at 3 weeks, followed by a telephone call and an option to complete the questionnaire by telephone. To increase Latina participation, we used surnames to identify women who were likely to report Latina ethnicity and provided study materials in both English and Spanish [36]. Clinical data from the SEER registries were merged with survey data obtained by patients at both time points. Study procedures received approval from the Institutional Review Boards of the University of Michigan, the University of Southern California and Wayne State University.

Measures

Dependent Variables

The dependent variables of endocrine therapy initiation and persistence were obtained from the follow up questionnaire completed approximately four years after diagnosis. First, we asked women if they had taken any of the following hormonal breast cancer medicines in the past week: exemestane (Aromasin), letrozole (Femara), anastrozole (Arimedex), tamoxifen (Nolvadex), or raloxifene (Evista). Respondents who answered “yes” were classified as being persistent with endocrine therapy. Respondents who answered “no” were asked if they had ever taken any of the medications listed above. Those who answered “yes” were classified as having initiated therapy. The third group was comprised of those women who reported “no” to having taken endocrine therapy in the past week and also reported “no” to ever taking endocrine therapy.

Independent Variables

The SEER registries provided the following information: age at diagnosis, race/ethnicity (white, Latina, black), stage (I, II, III), grade (1, 2, 3, or unknown), tumor size (in cm), and estrogen/progesterone receptor status. The baseline questionnaire completed by patients approximately 9 months after diagnosis assessed the presence of comorbid conditions (none, 1, 2 or more), education (high school or less, some college, college graduate), weight (in pounds), and married or partnered (yes/no). In addition to the outcome measures defined above, the follow up questionnaire completed approximately 4 years after diagnosis queried patients on their primary provider for cancer follow up (surgeon, medical oncologist, or other), and whether patients had received enough information from their doctor about endocrine therapy (yes/no). Number of medications taken weekly (none, 1, 2 or more) was asked at the follow up survey and was included in analyses of the persistence outcome only. Two scales were included in the follow-up questionnaire to measure medication beliefs and worry about recurrence. To assess medication beliefs, items modified from the previously-validated beliefs about medicine questionnaire [37] assessed patients’ agreement about statements with regard to medicine, including “medicines do more harm than good.” Five items on a five-point Likert scale were used and a mean score (range of 1-5), with higher scores reflecting more positive beliefs toward medication use. As in our previous report [38], worry about recurrence was measured on a five-point Likert scale from three items: concern the cancer would recur in the same breast, the other breast, or in another part of the body. An overall worry score was calculated as a mean across the three items. Higher scores reflect greater worry about recurrence (range 1-5; Cronbach alpha = 0.86). For modeling purposes, we categorized the worry about recurrence score into three levels: low (≤ 2.0 on a 5-point scale), medium (2.1-4.0), and high (>4.0). Finally, women who never initiated endocrine therapy or discontinued therapy prematurely were asked their reasons for doing so. These included physician instructions to discontinue, concerns for side effects, and cost/insurance issues. Participants could select multiple responses to this question.

Statistical Analyses

We first calculated descriptive statistics for the entire analytical sample and the subgroups of women who initiated or persisted with therapy. To compare the patients who initiated (or persisted) with those who did not initiate (or persist), we used Chi-square tests for categorical variables and ANOVA for continuous variables. Several clinical variables that may influence use of endocrine therapy were included in all analyses. These include tumor stage, tumor grade, and age. Additional measures described above were candidates for model inclusion. To achieve model parsimony, backward variable selection procedures were used to eliminate non-clinical variables that did not reach statistical significance level of 0.10. All analyses were adjusted for geographic location (Los Angeles versus Detroit). Odds ratios (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (95% CI) were calculated and presented. The F tests were used to examine the overall association of independent variables with the outcome of interest. Finally, we used descriptive statistics to examine reported reasons for non-initiation of and non-persistence with adjuvant endocrine therapy.

Survey Weighting

In the initial descriptive statistics and multivariable models, we incorporated survey weights to make our statistical inference representative of the population. We created design weights to account for oversampling of blacks and Latinas, as well as disproportionate selection across locations. We also weighted the sample for non-response to recognize that certain patient characteristics are likely to influence response to both the baseline and follow up questionnaire. Multivariable logistic regression models were used to create the non-response weights, with the final weight calculated as the product of the design and non-response weights. All statistical tests were two-sided, and a p value less than .05 was considered statistically significant. All analyses were performed using STATA (College Station, TX).

Results

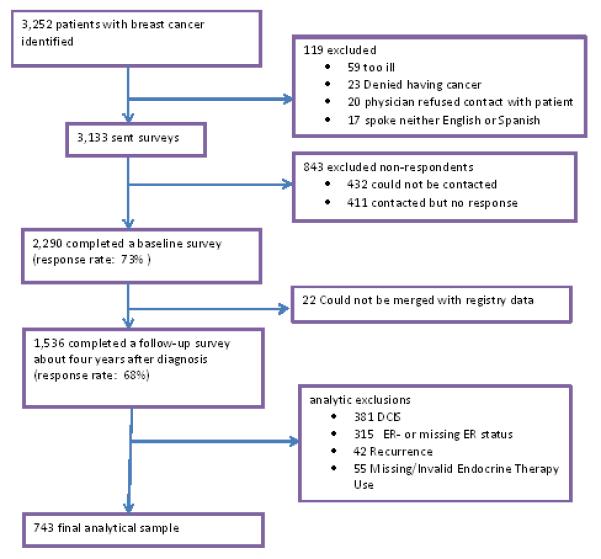

These analyses are based on 743 respondents with invasive disease (see Figure for details on how the analytic sample was derived). 1,536 women completed both the baseline and follow up surveys. To restrict our sample to women who met clinical indications for endocrine therapy, we excluded 793 respondents: those who did not have invasive disease (n = 381), had negative or unknown ER and/or PR receptor status (n = 315), had experienced a recurrence at the time of our follow up survey (n = 42), or had incomplete data on study measures (n = 55).

Figure.

The derivation of the analytic sample is shown, with reasons for exclusion.

Of the 743 women in our analytic sample, 663 (89.2%) initiated endocrine therapy. Of those who initiated therapy, 551 (83.1%) were persistent with therapy at approximately four years after diagnosis (74.2% of the entire analytic sample). Table 1 shows the characteristics of the study sample and the distribution of the outcome variables, initiation and persistence. In the bivariate analyses, significant differences were observed on rates of endocrine therapy initiation by age, SEER tumor grade, the presence of comorbid conditions, worry about recurrence score, receipt of information about endocrine therapy, and primary provider for cancer care follow up. Initiation rates varied by the presence of comorbid conditions (p < .01) with 82%, 94% and 90% for women with 2 or more conditions, one condition and none respectively. The degree of worry about recurrence was significantly associated with the rate of initiation (p=0.02); patients with higher worry about recurrence had higher rates of initiation (93%, 89% and 83% for high, medium and low worry scores, respectively).

Table 1.

Participant Characteristics by Initiation and Persistence of Endocrine Therapy

| Entire Sample (n=743) |

% Initiated Therapy (n=663) |

P | % Persist on Therapy (n=551) |

P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, mean (SD) | 58.9 (11.7) | 57.5 (11.2) | .05 | 57.1 (11.1) | .11 |

| Education | .59 | .26 | |||

| High school or less | 264 (39.9) | 90 | 82 | ||

| Some college | 253 (33.2) | 87 | 82 | ||

| College graduate + | 217 (26.8) | 91 | 88 | ||

| Race | .46 | .10 | |||

| White | 409 (48.3) | 87 | 81 | ||

| Latina | 183 (37.6) | 91 | 88 | ||

| Black | 140 (14.2) | 91 | 78 | ||

| SEER Stage | .31 | .21 | |||

| Stage I | 395 (48.5) | 88 | 81 | ||

| Stage II | 263 (38.6) | 89 | 84 | ||

| Stage III | 83 (12.9) | 93 | 91 | ||

| SEER Grade | <.01 | .07 | |||

| Grade 1 | 177 (21.8) | 85 | 81 | ||

| Grade 2 | 326 (45.7) | 94 | 84 | ||

| Grade 3 | 193 (25.6) | 86 | 91 | ||

| Unknown Grade | 47 (6.9) | 100 | 50 | ||

| Comorbid Conditions | <.01 | .57 | |||

| None reported | 297 (40.0) | 90 | 83 | ||

| One reported | 223 (31.1) | 94 | 85 | ||

| 2 or more reported | 223 (28.8) | 82 | 81 | ||

|

Number of medications taken

in the week prior to the follow up survey |

<.001 | ||||

| 0-1 | 157 (21.6) | 68 | |||

| 2 or more | 578 (78.5) | 87 | |||

|

Medication Beliefs Scale, mean (SD) |

2.91(0.57) | 2.83 (0.59) | 0.28 | 2.82 (0.59) | .13 |

| Worry about Recurrence Score | .020 | .05 | |||

| Low (≤ 2.0) | 154 (18.7) | 83 | 81 | ||

| Medium (2.1- 4.0) |

413 (54.5) | 89 | 81 | ||

| High (> 4.0) | 174 (26.8) | 93 | 90 | ||

|

Received enough information about endocrine

therapy |

<.001 | <.001 | |||

| Yes | 622 (83.8) | 92 | 84 | ||

| No | 110 (16.2) | 74 | 77 | ||

| Primary Oncology Provider | <.01 | .14 | |||

| Surgeon | 46 (6.3) | 84 | 77 | ||

| Medical | 561 (77.2) | 94 | 87 | ||

| Oncologist | |||||

| Other provider | 136 (16.5) | 70 | 65 | ||

Note: Values weighted to account for differential probabilities of sample selection and non-response.

In bivariate analyses (Table 1), fewer variables differed significantly on the persistence outcome. Weekly medication use was associated with different rates of persistence (p<.001) with 87% of patients who took 2 or more medications weekly persisted on therapy, compared with a persistence rate of 68% for women who took fewer than two medications weekly. Higher scores on the worry about recurrence scale were associated with significantly higher rates of persistence (p = .05). Those who reported they did not receive adequate information about endocrine therapy had lower rates of persistence (77 vs. 84%, p < .001).

Factors associated with endocrine therapy initiation

After backward variable selection procedures, several variables were removed from the initiation model, including tumor size, comorbid conditions, education, marital status, and the medication beliefs scale. The final weighted multivariable model is presented in Table 2. Initiation of therapy was associated with Latina ethnicity (OR 2.80, 95% CI 1.08-7.23), black race vs. non-Hispanic white (OR 3.63, 95% CI 1.22 – 10.78), and grade 2 tumors (versus Grade 1, OR 2.59, 95% CI 1.13-5.94). Women with higher scores on the worry about recurrence scale were more likely to report initiation (Medium vs. Low OR 2.25, 95% CI 1.06-4.82; High vs. Low OR 3.54, 95% CI 1.31-9.56), as were women who reported their primary provider for cancer follow up was a medical oncologist rather than a surgeon (OR 3.21, 95% CI 1.02-9.60). Women who reported they had received inadequate information about endocrine therapy were significantly less likely to initiate treatment than women who did not report inadequate information (OR 0.25, 95% CI 0.10-0.55). Age and tumor stage were not significantly associated with initiation.

Table 2.

Multivariable Model to Assess Factors Associated with Endocrine Therapy Initiation (n=598)

| Factor | Adjusted Odds Ratio |

95% CI | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Race | |||

| White | 1.0 | ref | .02 |

| Latina | 2.80 | 1.08-7.23 | |

| Black | 3.63 | 1.22-10.78 | |

| SEER Stage | |||

| Stage I | 1.0 | ref | .35 |

| Stage II | 1.62 | 0.76-3.51 | |

| Stage III | 1.84 | 0.55-6.19 | |

| SEER Grade | |||

| Grade 1 | 1.0 | ref | <.001 |

| Grade 2 | 2.59 | 1.13-5.94 | |

| Grade 3 | 1.84 | 0.55-6.19 | |

| Age | 1.00 | 0.97-1.04 | .80 |

| Worry about Recurrence Score | |||

| Low | 1.0 | ref | .03 |

| Medium | 2.25 | 1.06-4.82 | |

| High | 3.54 | 1.31-9.56 | |

|

Received enough information about endocrine therapy |

|||

| Yes | 1.0 | ref | <.001 |

| No | 0.24 | 0.10-0.55 | |

| Primary Oncology Provider | |||

| Surgeon | 1.0 | ref | <.001 |

| Medical Oncologist | 3.12 | 1.02-9.60 | |

| Other Provider | 0.44 | 0.14-1.40 |

Note: Parameter estimates weighted to account for differential probabilities of sample selection and non-response.

Model includes adjustment for SEER site (Detroit vs. Los Angeles)

Factors associated with endocrine therapy persistence at four years

Table 3 shows the weighted multivariable model for persistence with measures retained after backward variable selection procedures. Lower likelihood of persistence was associated significantly with increasing age (OR 0.98, OR 0.95-1.00, p < .04). Compared with those who reported taking none or one medication weekly, women who took two or medications weekly as reported in the follow up survey were more likely to persist on therapy (OR 4.19, 95% CI 2.28-7.68). No significant differences in persistence were observed by race/ethnicity, tumor stage, tumor grade, worry about recurrence, or type of provider for follow up oncology care.

Table 3.

Multivariable Model to Assess Factors Associated with Endocrine Therapy Persistence (n=539)

| Factor | Adjusted Odds Ratio |

95% CI | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Race | |||

| White | 1.0 | ref | .43 |

| Latina | 1.29 | 0.59-2.80 | |

| Black | 0.72 | 0.38-1.38 | |

| SEER Stage | |||

| Stage I | 1.0 | ref | |

| Stage II | 1.37 | 0.76-2.46 | .37 |

| Stage III | 1.90 | 0.65-5.59 | |

| SEER Grade | |||

| Grade 1 | 1.0 | ref | .06 |

| Grade 2 | 1.18 | 0.58-2.39 | |

| Grade 3 | 0.55 | 0.25-1.20 | |

| Age | 0.98 | 0.95-1.00 | .04 |

|

Number of medications taken

in the week prior to the follow up survey |

|||

| 0-1 | 1.0 | ref | <.001 |

| 2 or more | 4.19 | 2.28-7.68 | |

| Worry about Recurrence Score | |||

| Low | 1.0 | ref | .14 |

| Medium | 0.66 | 0.33-1.32 | |

| High | 1.29 | 0.49-3.41 | |

| Primary Oncology Provider | |||

| Surgeon | 1.0 | ref | .11 |

| Medical Oncologist | 1.44 | 0.51-4.04 | |

| Other Provider | 0.40 | 0.13-1.22 |

Note: Parameter estimates weighted to account for differential probabilities of sample selection and non-response.

Model includes adjustment for SEER site (Detroit vs. Los Angeles)

Reasons for non-initiation and non-persistence

Therapy-eligible participants who never initiated therapy (n = 80) were asked why they did not, and these unweighted descriptive responses are shown in Table 4a. Participants could choose multiple responses. Clinician factors were primarily cited, including statements such as doctor said they did not need therapy (n=27, 33.8%), or the doctor left it up to the patient (n=17, 21.3). Reported patient factors included concerns about side effects (n=23, 28.8%) and cost (n=4, 5.0%). Patient factors were cited by many of the 112 women who discontinued treatment; 45 (40.2%) cited side effects, 28 (25%) cited concerns about the risks from the medication, and 26 (23.2%) reported a general dislike of medication (see Table 4b).

Table 4a.

Reasons for Never Initiating Endocrine Therapy (n=80)

| Never Initiated n (%) |

|

|---|---|

| Clinician Factors | |

| Doctor said I did not need | 27 (33.8) |

| Doctor left it up to me | 17 (21.3) |

| Doctor never discussed | 6 (7.5) |

| Patient Factors | |

| Worried about side effects | 23 (28.8) |

| Doctor recommended, but I chose not to |

15 (18.8) |

| Too expensive | 4 (5.0) |

Table 4b.

Reasons for Premature Discontinuation of Endocrine Therapy (n=112)

| Discontinued n (%) |

|

|---|---|

| Patient Factors | |

| Side Effects | 45 (40.2) |

| Worried about risks | 28 (25.0) |

| Dislike medication | 26 (23.2) |

| I wasn’t sure if it was helping | 25 (22.3) |

| Too expensive | 21 (18.8) |

| I’d taken it long enough | 20 (17.9) |

| I wanted to move on from cancer | 14 (16.1) |

| I stopped for insurance reasons | 8 (7.1) |

| Clinician Factors | |

| Doctor told me to stop | 28 (25.0) |

| Completed course of treatment | 14 (12.5) |

Note. Percentages do not add up to 100% as participants could choose multiple responses.

Discussion

The majority of women in our population based sample eligible for endocrine therapy both initiated and persisted on therapy: of the 743 patients eligible for endocrine therapy, 80 (10.8%) never initiated therapy, 112 (15.1%) started therapy but discontinued prematurely, and 551 (74.2%) continued use at the second time point. Our findings are consistent with previously published reports. A study that used commercial claims data to assess adherence with adjuvant anastrozole therapy [8] showed that women enrolled in three different insurance plans had adherence rates of 62-79% by the third year of treatment. Women in our study were treated more recently (2005-2010) compared with a timeframe of 2002-2004 in above-cited study [8]. A single-site study performed in 2006 reported similar rates of initiation and persistence [39].

Blacks and Latinas had the highest rates of initiation and persistence in our sample. Ours is not the first study to document null findings or higher rates of treatment completion in groups historically considered disadvantaged. Recent reports have documented the absence of racial disparities in adjuvant endocrine therapy in the Medicare [40] and Medicaid [41] populations, as well in the receipt of systemic chemotherapy [34, 42]. Poverty, insurance coverage, family support, and overall treatment experiences are contextual factors that may explain endocrine therapy persistence [43-46]. Our study did not examine the effects of peer support or breast cancer navigator programs, both of which may have supported black and Latinas through treatment during the study period.

Patients who initiated endocrine therapy expressed more worry about recurrence, regardless of tumor stage and grade. While clinicians educate patients to mitigate the anxiety surrounding a breast cancer diagnosis, health behaviorists assert that perceived susceptibility is a strong motivator for desired health behaviors [47]. In our study and in a report by others [25], women who reported receiving less information about endocrine therapy were less likely to initiate therapy. Adequacy of information was associated with initiation but not persistence. This suggests that clinicians need to address patient information needs regarding therapy prior to initiation of treatment. Treatment initiation was higher for women who saw medical oncologists as opposed to other providers for their follow-up cancer care. It is likely that patients who saw medical oncologists may have clearer indications for endocrine therapy. Other providers of follow up oncology care may benefit from additional education or resources to support patients receiving endocrine therapy. Women who took two or more medications at the time of the follow up survey were more likely to persist with endocrine therapy, which suggests that women who were less experienced in medication use prior to a breast cancer diagnosis may be at risk for low persistence.

Patients who did not initiate treatment cited provider factors as the primary reason. These responses likely reflect physician judgment that endocrine therapy is not warranted in these cases. It is interesting to note that few patients endorsed insurance coverage as a reason for not starting therapy, despite the findings from previous investigators [48]. However, a total of 32 patients cited drug expense or insurance issues as one of many reasons for not initiating or persisting with therapy. In our sample, patient attitudes about endocrine therapy and medication in general were associated with premature termination. Side effects, safety concerns, and a general dislike of medication were the most often-cited factors. Severe side effects were the largest predictor of discontinuation of tamoxifen in a prior study [25]. These findings from a population-based sample of patients are timely considering the ATLAS trial results reported at the 2012 San Antonio Breast Cancer Symposium. In this clinical trial, women who completed 10 years of adjuvant tamoxifen therapy compared with five years had significantly lower recurrence and breast cancer mortality rates [13]. Outside of a clinical trial, clinicians may be challenged to maintain patients on therapy for ten years if side effects are a key barrier to persistence. Aggressive supportive care and consultation with oncology pharmacists may be important interventions to consider if the duration of endocrine therapy is extended in forthcoming clinical practice guidelines.

There are several limitations of this study. First, we relied on patient self-report of initiation and persistence to endocrine therapy. We were unable to ascertain if patients who did not initiate were not offered a prescription for endocrine therapy. Measurement of medication use with prescription data or the clinical record would strengthen the validity of our findings [49]. The data derived from a sample of women who completed surveys at approximately 9 months and 4 years after breast cancer diagnosis. Our sample of women is more likely to persist on therapy than women in the general population. Because routine medication use was measured only at the 4-year follow up survey, we cannot assess the degree to which routine medical use influences initiation of therapy. Another limitation of this study is that the study participants were recruited from only two sites—Los Angeles county and Metropolitan Detroit—with three racial and ethnic groups: white, black, and Latina women. While our study sample is diverse, findings may not be generalizable to other populations or geographic settings.

In conclusion, adjuvant endocrine therapy initiation and persistence rates are high in a diverse population-based sample of eligible women. Differences by socioeconomic status are small. Initiation is influenced by worry about recurrence, sufficient information receipt about these agents, and primary source of cancer care during treatment with endocrine therapy. Persistence is associated with younger age and concurrent medication use. Care settings without medical oncologists may benefit from additional resources to support eligible patients. Non-persistence was largely related to patient attitudes toward therapy. These findings highlight the need for additional education and support strategies for women – regardless of race or ethnicity – at risk for not initiating or persisting on adjuvant endocrine therapy to optimize treatment and reduce breast cancer recurrence and improve survival.

Acknowledgements

This work was funded by grants R01 CA109696 and R01 CA088370 from the National Cancer Institute to the University of Michigan. Dr. Friese was supported by a Pathway to Independence Award from the National Institute for Nursing Research (R00NR01570). Dr. Katz was supported by an Established Investigator Award in Cancer Prevention, Control, Behavioral, and Population Sciences Research from the National Cancer Institute (K05CA111340). Dr. Jagsi was supported by a Mentored Research Scholar Grant from the American Cancer Society (MRSG-09-145-01). The collection of Los Angeles County cancer incidence data was supported by the California Department of Public Health as part of the statewide cancer reporting program mandated by California Health and Safety Code §103885. The National Cancer Institute’s Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program under contract N01-PC-35139 was awarded to the University of Southern California. Contract N01-PC-54404 and agreement 1U58DP00807-01 were awarded to the Public Health Institute. The collection of metropolitan Detroit cancer incidence data was supported by the National Cancer Institute’s Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program under contract N01-PC-35145.

Footnotes

Financial Disclosures: None

Ethical Standards: Institutional Review Boards of the University of Michigan, the University of Southern California, and Wayne State University approved the study described in this manuscript.

Conflict of Interest: The authors declare they have no conflict of interest.

Contributor Information

Christopher R. Friese, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, Michigan.

T. May Pini, Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, Texas

Yun Li, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, Michigan.

Paul H. Abrahamse, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, Michigan.

John J. Graff, Cancer Institute of New Jersey, Robert Wood Johnson Medical School, New Brunswick, NJ.

Ann S. Hamilton, Keck School of Medicine, University of Southern California.

Reshma Jagsi, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor.

Nancy K. Janz, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, Michigan.

Sarah T. Hawley, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, Michigan.

Steven J. Katz, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, Michigan.

Jennifer J. Griggs, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, Michigan.

References Cited

- 1.Early Breast Cancer Trialists’ Collaborative Group Effects of chemotherapy and hormonal therapy for early breast cancer on recurrence and 15-year survival: An overview of the randomised trials. Lancet. 2005;365:1687–1717. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)66544-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Forbes JF, Cuzick J, Buzdar A, Howell A, Tobias JS, Baum M. Effect of anastrozole and tamoxifen as adjuvant treatment for early-stage breast cancer: 100-month analysis of the ATAC trial. Lancet Oncol. 2008;9:45–53. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(07)70385-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yood MU, Owusu C, Buist DS, et al. Mortality impact of less-than-standard therapy in older breast cancer patients. J Am Coll Surg. 2008;206:66–75. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2007.07.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Swedish Breast Cancer Cooperative Group Randomized trial of two versus five years of adjuvant tamoxifen for postmenopausal early stage breast cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1996;88:1543–1549. doi: 10.1093/jnci/88.21.1543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sacco M, Valentini M, Belfiglio M, et al. Randomized trial of 2 versus 5 years of adjuvant tamoxifen for women aged 50 years or older with early breast cancer: Italian Interdisciplinary Group Cancer Evaluation Study of Adjuvant Treatment in Breast Cancer 01. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:2276–2281. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.06.116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Weaver KE, Camacho F, Hwang W, Anderson R, Kimmick G. Adherence to adjuvant hormonal therapy and its relationship to breast cancer recurrence and survival among low-income women. Am J Clin Oncol. 2012 doi: 10.1097/COC.0b013e3182436ec1. Available from DOI:10.1097/COC.0b013e3182436ec1 [September 29, 2012] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hershman DL, Shao T, Kushi LH, et al. Early discontinuation and non-adherence to adjuvant hormonal therapy are associated with increased mortality in women with breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2011;126:529–37. doi: 10.1007/s10549-010-1132-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Partridge AH, Lafountain A, Mayer E, Taylor BS, Winer E, Asnis-Alibozek A. Adherence to initial adjuvant anastrozole therapy among women with early-stage breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:556–562. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.11.5451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Partridge AH, Wang PS, Winer EP, Avorn J. Nonadherence to adjuvant tamoxifen therapy in women with primary breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:602–606. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.07.071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.National Comprehensive Cancer Network [October 1, 2012];NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology: Breast Cancer. Version 3.2012. Available from URL: http://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/breast.pdf.

- 11.Goldhirsch A, Wood WC, Gelber RD, Coates AS, Thurlimann B, Senn HJ. Meeting highlights: Updated international expert consensus on the primary therapy of early breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:3357–3365. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.04.576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Thuerlimann B. Breast Cancer; International consensus meeting on the treatment of primary breast cancer 2001; St. Gallen, Switzerland. 2001. pp. 294–297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Davies C, Hongchao P, Godwin J, et al. ATLAS. 10 v 5 years of adjuvant tamoxifen (TAM) in ER+ disease: Effects on outcome in the first and in the second decade after diagnosis. Paper presented at: CTRC-AACR San Antonio Breast Cancer Symposium; San Antonio TX. December 5, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jin H, Tu D, Zhao N, et al. Longer-term outcomes of Letrozole versus placebo after 5 years of tamoxifen in the NCIC CTG MA.17 trial: analyses adjusting for treatment crossover. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30(7):718–721. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.34.4010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Buzdar A, Howell A, Cuzick J, et al. Comprehensive side-effect profile of anastrozole and tamoxifen as adjuvant treatment for early-stage breast cancer: Long-term safety analysis of the ATAC trial. Lancet Oncol. 2006;7:633–643. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(06)70767-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Henry NL, Giles JT, Ang D, et al. Prospective characterization of musculoskeletal symptoms in early stage breast cancer patients treated with aromatase inhibitors. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2008;111:365–372. doi: 10.1007/s10549-007-9774-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mariotto A, Feuer EJ, Harlan LC, Wun LM, Johnson KA, Abrams J. Trends in use of adjuvant multi-agent chemotherapy and tamoxifen for breast cancer in the United States: 1975-1999. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2002;94:1626–1634. doi: 10.1093/jnci/94.21.1626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Harlan LC, Clegg LX, Abrams J, Stevens JL, Ballard-Barbash R. Community-based use of chemotherapy and hormonal therapy for early-stage breast cancer: 1987-2000. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:872–877. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.03.5840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hebert-Croteau N, Brisson J, Latreille J, Gariepy G, Blanchette C, Deschenes L. Time trends in systemic adjuvant treatment for node-negative breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 1999;17:1458–1464. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1999.17.5.1458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lash TL, Silliman RA, Guadagnoli E, Mor V. The effect of less than definitive care on breast carcinoma recurrence and mortality. Cancer. 2000;89:1739–1747. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(20001015)89:8<1739::aid-cncr14>3.0.co;2-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Atkins L, Fallowfield L. Intentional and non-intentional non-adherence to medication amongst breast cancer patients. Eur J Cancer. 2006;42:2271–2276. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2006.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Demissie S, Silliman RA, Lash TL. Adjuvant tamoxifen: Predictors of use, side effects, and discontinuation in older women. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19:322–328. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2001.19.2.322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fink AK, Gurwitz J, Rakowski W, Guadagnoli E, Silliman RA. Patient beliefs and tamoxifen discontinuance in older women with estrogen receptor-positive breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:3309–3315. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.11.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Grunfeld EA, Hunter MS, Sikka P, Mittal S. Adherence beliefs among breast cancer patients taking tamoxifen. Patient Educ Couns. 2005;59:97–102. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2004.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kahn KL, Schneider EC, Malin JL, Adams JL, Epstein AM. Patient centered experiences in breast cancer: Predicting long-term adherence to tamoxifen use. Med Care. 2007;45:431–439. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000257193.10760.7f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lash TL, Fox MP, Westrup JL, Fink AK, Silliman RA. Adherence to tamoxifen over the five-year course. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2006;99:215–220. doi: 10.1007/s10549-006-9193-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chlebowski RT, Geller ML. Adherence to endocrine therapy for breast cancer. Oncology. 2006;71:1–9. doi: 10.1159/000100444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.DiMatteo MR. Variations in patients’ adherence to medical recommendations: A quantitative review of 50 years of research. Med Care. 2004;42:200–209. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000114908.90348.f9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Osterberg L, Blaschke T. Adherence to medication. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:487–497. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra050100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Owusu C, Buist DS, Field TS, et al. Predictors of tamoxifen discontinuation among older women with estrogen receptor -positive breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:549–555. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.10.1022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Doshi JA, Zhu J, Lee BY, Kimmel SE, Volpp KG. Impact of a prescription copayment increase on lipid-lowering medication adherence in veterans. Circulation. 2009;119:390–397. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.783944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Piette JD, Heisler M. Problems due to medication costs among VA and non-VA patients with chronic illnesses. Am J Manag Care. 2004;10:861–868. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Piette JD, Heisler M, Krein S, Kerr EA. The role of patient-physician trust in moderating medication nonadherence due to cost pressures. Arch Intern Med. 2005;165:1749–1755. doi: 10.1001/archinte.165.15.1749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Griggs JJ, Hawley ST, Graff JJ, et al. Factors associated with receipt of breast cancer adjuvant chemotherapy in a diverse population-based sample. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:3058–3064. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.41.9564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dillman DA. Mail and Internet Surveys: The Tailored Design Method. 2nd Ed Wiley; New York: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hamilton AS, Hofer TP, Hawley ST, et al. Latinas and breast cancer outcomes: population-based sampling, ethnic identity, and acculturation assessment. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2009;18:2022–2029. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-09-0238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Horne R, Weinman J. Patients’ beliefs about prescribed medicines and their role in adherence to treatment in chronic physical illness. J Psychosom Res. 1999;47:555–567. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3999(99)00057-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Janz NK, Hawley ST, Mujahid MS, et al. Correlates of worry about recurrence in a multiethnic population-based sample of women with breast cancer. Cancer. 2011;117:1827–1836. doi: 10.1002/cncr.25740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Danilak M, Chambers CR. Adherence to adjuvant endocrine therapy in women with breast cancer. J Oncol Pharm Pract. 2012 Aug 15; doi: 10.1177/1078155212455939. epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yen TW, Czypinski LK, Sparapani RA, et al. Socioeconomic factors associated with adjuvant hormone therapy use in older breast cancer survivors. Cancer. 2011;117:398–405. doi: 10.1002/cncr.25412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yung RL, Hassett MJ, Chen K, et al. Initiation of adjuvant hormone therapy by Medicaid insured women with nonmetastatic breast cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2012;104:1102–1105. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djs273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lipscomb J, Gillespie TW, Goodman M, et al. Black-white differences in receipt and completion of adjuvant chemotherapy among breast cancer patients in a rural region of the US. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2012;133:285–296. doi: 10.1007/s10549-011-1916-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kimmick GG, Anderson R, Camacho F, et al. Adjuvant hormonal therapy use among insured, low-income women with breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:3445–3551. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.19.2419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Land SR, Cronin WM, Wickerham DL, et al. Cigarette smoking, obesity, physical activity, and alcohol use as predictors of chemoprevention adherence in the national surgical adjuvant breast and bowel project p-1 breast cancer prevention trial. Cancer Prev Res. 2011;4:1393–1400. doi: 10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-11-0172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lin JH, Zhang SM, Manson JE. Predicting adherence to tamoxifen and breast cancer adjuvant therapy and prevention. Cancer Prev Res. 2011:1360–1365. doi: 10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-11-0380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Friese CR. Disparities in breast cancer care delivery: solving a complex puzzle. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2012;133:297–299. doi: 10.1007/s10549-012-2005-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Janz NK, Becker MH. The health belief model: a decade later. Health Educ Q. 1984;11:1–47. doi: 10.1177/109019818401100101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wu XC, Lund MJ, Kimmick GG, et al. Influence of race, insurance, socioeconomic status, and hospital type on receipt of guideline-concordant adjuvant systemic therapy for locoregional breast cancers. J Clin Oncol. 2011;30(2):142–50. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.36.8399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Oberguggenberger A, Sztankay M, Beer B, et al. Adherence evaluation of endocrine treatment in breast cancer: methodological aspects. BMC Cancer. 2012:474. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-12-474. Available from URL: http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2407/12/474 [October 22, 2012] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]