Abstract

AIM

To analyse previous literature and to formulate a management strategy for iris microhaemangiomas (IMH).

METHODS

A review of the literature in English language articles on IMH.

RESULTS

Thirty five English language articles fulfilled the criteria for inclusion to the study and based on the contents on these articles a management strategy was formulated. Age at presentation ranged from 42 to 80 years with no sex or racial predisposition. Most patients with IMH have no systemic disease but a higher incidence had been reported in patients with diabetes mellitus, myotonic dystrophy, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) and several other systemic and ophthalmic co-morbidities. Most patients remained asymptomatic until they experienced a sudden blurring of vision due to a hyphaema. Some patients only develop a self-limiting single episode of hyphaema and therefore the laser or surgical photocoagulation of iris should be reserved for the cases complicated with recurrent hyphaema. In some patients, several laser photocoagulation sessions may be needed and the recurrent iris vascular tufts may require more aggressive treatment. Iris fluorescein angiography (IFA) is useful in identifying the true extent of the disease and helps to improve the precision of the laser treatment. Surgical excision (iridectomy) should only be considered in patients who fail to respond to repeated laser treatment. In some cases IMHs has been initially misdiagnosed as amaurosis fugax, iritis and Posner-Schlossman syndrome.

CONCLUSION

Owing to its scarcity, there is no good quality scientific evidence to support the management of IMH. The authors discuss the various treatment options and present a management strategy based on the previous literature for the management for this rare condition and its complications.

Keywords: iris microhaemangioma, iris vascular tufts, capillary haemangioma of iris, Cobb's tufts, Argon laser photocoagulation

INTRODUCTION

Iris microhaemangiomas (IMH) are hamartomas of the iris stromal vasculature of the eye [1]. They can cause spontaneous bleeding into the anterior chamber of the eye which sometimes results in severely raised intraocular pressure (IOP) which could last for several days and may potentially cause irreversible visual field loss[2],[3]. Owing to the rarity of IMH, there is no good quality scientific evidence to support the management of this rare but challenging condition [3]. Therefore, there is no mutually agreed plan of management in the literature in the treatment of IMH. The purpose of the following literature review was to analyse the previous reports on this subject and to formulate a plan of management for this condition and its complications. In addition, the authors present an example of a case managed successfully following the proposed treatment protocol.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The investigators searched the English language PubMed articles on IMH indexing keywords ‘iris microhaemangiomas’, ‘iris vascular tufts’, ‘capillary haemangioma of iris’, ‘Cobbs tufts’ or ‘spontaneous hyphaema’. All the articles on IMH were included in the study and the full text articles of 35 publications (from 1958 to 2010) were carefully studied.

RESULTS

Patient Demographics

IMHs appear as very small nodular lesions on the iris and range from 15-150µm[4]-[8]. They are also known as iris vascular tufts[4], capillary haemangioma of iris[7] or Cobbs tufts[4], [9], [10]. They can be single or multiple and commonly affects both eyes [5]. The patients are usually in the fifth decade or older[1], [5], [7], [9]. IMH appears to occur more frequently in myotonic dystrophy and in these patients they manifest earlier than in other patients[11]. No sex or racial predisposition has been noted [7].

Symptoms and Signs

Patients tend to remain asymptomatic unless they experience sudden blurring of vision due to hyphaema [2], [3], [12]. This is the commonest presenting complaint and the degree of visual disturbance is usually proportionate to the extent of hyphaema and may range from normal visual acuity to ‘light perception’ [3]. IMH should therefore, be suspected in all patients presenting with spontaneous hyphaema[13]. In mild cases, the blood in the anterior chamber clears within hours and the visual acuity returns back to their normal visual acuity[2]. In these patients transient visual loss can be erroneously attributed to Amaurosis fugax. As a result they may undergo expensive investigations and subsequently subjected to the wrong treatment. In some cases in which the hyphaema had completely cleared, the only positive finding can be the raised IOP giving the impression that the patient suffers from ocular hypertension. But after a short period of time, the IOP returns to normal levels posing a diagnostic confusion and such cases may often be misdiagnosed and mistreated indefinitely for ocular hypertension/glaucoma unless fully investigated. Some patients experience a chronic ocular discomfort [2] or even significant ocular pain [5] especially during reading. Rarely the conjunctiva can also be injected [5]. When the hyphaema is limited only to the free floating red blood cells, they may be mistaken for cells in ‘mild iritis’. Ah-Fat et al[2] presented a case which was misdiagnosed to have ‘mild iritis in two previous presentations. If the IOP persist for several weeks at very high levels these cases can be misdiagnosed as ‘Posner-Schlossman syndrome’ after the resolution of the hyphaema which may be limited to a few free floating red cells[2], [3], [14]. In some reports patients have noticed ‘blood in the eye’ on looking in the mirror. The presenting complaint may include erythropsia or red desaturation due to the presence of blood in the anterior chamber [2]. Winnick et al[15] reports an intra-operative hyphaema during cataract surgery, most probably secondary to iris trauma during the surgical procedure. IMH are isolated or multiple tightly-coiled tufts of blood vessels with thin, delicate, capillary-like walls at the ruff of the pupillary border and they are difficult to be identified by the slitlamp examination alone and difficult to be photographed due their small size [14], [16]. Occasionally, the pigmentation of the iris around the microhaemangioma is altered giving a clue to the diagnosis [9]. After the blood clot is retracted, these recently bled fleshy red vascular tufts can sometimes be identified on the pupillary margin when examined at high magnification [2], [3]. The gonioscopic examination is normal except for blood in the anterior chamber angle inferiorly in acute cases [2], [3], [15]. The fundoscopy is usually normal [5]. However, both Akram et al[3] and Winnick et al reported two cases of iris vascular tufts associated with ipsilateral optic disc hyperaemia, nerve fiber layer haemorrhages and venous congestion. Akram et al[3] reports complete resolution of these retinal changes within the next six weeks.

Ocular and Systemic Associations

Although the exact aetiology remains unknown several ocular and systemic co-morbidities have been observed to co-exist with IMH. There may be similar vascular anomalies elsewhere in the body such as cavernous hemangiomas of the orbit[17]-[19], Sturge-Weber syndrome or cutaneous haemangiomas[15] Cota et al[9] reported a case of Hereditary haemorrhagic telangiectasia presenting with bilateral hyphaema and vascular anomalies of the iris similar to IMH. This rare autosomal dominant disorder is characterised by abnormal multiple dilatations of capillaries and venules which have a tendency to bleed. In a large proportion of these patients (45%-65%) conjunctival and/or eyelid telangiectasia can be seen. Rarely retinal neovascularization can also be present [7]. In contrast, IMH is thought to be an acquired vascular anomaly and usually there is no family history. The majority of patients with IMH are in good general health [2], [20]. Whilst it is unclear whether there is an association or not, previous authors have attributed that hypertension[3], [16], type 2 diabetes mellitus[4], [5], [9], [16], [21], [22], myotonic dystrophy[4], [9], [21], congenital cyanotic heart disease[23], congenital hemangiomatosis[24] and COPD [16] could be associated with IMH. Due to the bilateral iris involvement in some cases, some authors suspect a systemic aetiology[25]. Brusini et al[20] and Laidlaw et al[26] presented two cases of spontaneous hyphaema originating from an aneurysmal dilatation of iris vasculature similar to IMH in association with persistent remnants of the pupillary membrane. Some authors have reported the presence of IMH in patients with both new and old retinal venous occlusions [4], [6]. Mason [22] reported a patient with unilateral acute retinal branch vein occlusion who had bilateral iris neovascular tufts. Idiopathic juxtafoveolar retinal telangiectasis also found to be present in association with IMH[27]. Perry et al[14] reported a case of IMH which presented with acute angle closure crisis with hyphaema caused by IMH. Mason [21] reported an incidence of iris neovascular tufts in 12.5% (2 of 16) myotonic dystrophy patients, 6.7% (2 of 30) in type 2 diabetics, and no association in juvenile-onset diabetic (0 of 14) patients in his case series.

Investigations

The full blood count, clotting screen, urine analysis are usually normal [2], [3]. The Iris Fluorescein Angiogram (IFA) is the diagnosis of choice and it can show the true extent of these hamartomas which are far more numerous than detected by direct inspection [15]-[18]. Bilateral involvement should also be excluded by careful slit-lamp biomicroscopy of the fellow eye and should be photographed during the Iris Fluorescein Angiography (IFA) (see below) [4], [5]. In acute cases rarely a small stream of active bleeding into the anterior chamber can be seen [6]. IFA also helps to distinguish IMH from other iris pathology such as iris melanomas [26], [21]. It has been shown that tuft-like peripupillary leakage occurs incidentally in a significant number of apparently normal individuals [28]. The true extent of the vascular malformation is often significantly worse than the findings of the clinical examination [1], [16]-[18], [29]. The fellow eye should also be photographed to identify bilateral disease [5], [30].

Light microscopy and Electron microscopy

Histopathology studies of IMHs biopsied at the time of cataract extractions showed an aggregate of small thin walled vessels at the pupillary margin and there was a mild chronic inflammatory cell infiltrates in some cases[4], [7], [9]. Meades et al [24] and Amasio et al[31] presented their light and electron microscopic findings of IMHs following surgical iridectomy. This IMH was found to be a hamartoma formed by iris stromal blood vessels. These vessels were composed of endothelial cells and pericytes surrounded by loose connective tissue. Electron microscopy showed that the endothelial cells of these vessels of normal thickness with no fenestrations, and joined at their apices by terminal bars composed of zonula occludens and zonula adherens. Endothelial cells and pericytes lining the capillary are enveloped in a basement membrane, which closely connected to the surrounding loose connective tissue[21].

Differential Diagnosis

Iris melanoma is the most important differential diagnosis and serial examinations with photographic surveillance and specialist openion may be indicated in suspicious cases. IFA can be very useful non-invasive investigation and iridectomy can be both therapeutic and diagnostic and may be considered in atypical cases [24]. Hereditary haemorrhagic telangiectasia (HHT) is characterised by multiple dilatations of capillaries and venules in the skin, mucous membranes, and viscera that have a tendency to bleed. Although a relatively rare condition, conjunctival and eyelid involvement is common. But the iris involvement is extremely rare. Cota et al[12] reported a patient with Hereditary haemorrhagic telangiectasia (HHT) with spontaneous bilateral hyphaemas. This is an autosomal dominant disorder and it is characterized by abnormal multiple dilatations of capillaries and venules which have a tendency to bleed. Fortunately, iris vascular malformations are rare. In contrast, IMH is an acquired condition and there is no cutaneous and mucous membrane involvement. Inflamed iris vessels, rubeosis, iris haemangioma, iris neovascular tufts all can resemble the appearance of IMH and also result in spontaneous hyphaema [12].

Conservative Management

Acute conservative management

Raised IOP should be managed promptly to avoid permanent optic nerve damage. The response to oral acetazolamide [2], [3], and topical beta-blockers [2], [3], [7] has been reported to be rapid even in severe cases. Topical Mydriatics [15], [29] and topical steroids [4], [15], [32] can help to reduce the posterior synechiae formation and anterior chamber inflammation.

Definitive treatment

Some patients remain asymptomatic and some only develop a single episode of hyphaema [10], [16]. Therefore, laser or surgical treatment may be reserved for IMH complicated with recurrent hyphema [10], [16]. All patients who require treatment should undergo a pre-treatment IFA to assess the true extent of vascular anomalies [1].

IFA guided Serial Laser Photocoagulation

Laser photocoagulation has been used in several cases previously with good results [9], [7], [33]. It may serve to mitigate the risk of hemorrhage from these lesions during subsequent intraocular surgery and therefore, can be used prophylactic ally in circumstances such as cataract surgery. Laser settings should be titrated to therapeutic effect during the initial treatment sessions. Different reports recommend different laser settings and the laser spot size range from 50 to 250µm, and the duration of a single laser burn range from 0.05 to 0.2s in these reports [15], [17], [33]-[35]. Winnick et al[15] performed the most extensive laser photocoagulation for IMH using a 200µm spot size, power of 200mW for 0.1 seconds duration. In this case a total of 50 burns were required to close all tufts clinically and angiographically. The laser energy and the number of burns used depend on the number and size of the lesion and the pigmentation of the iris tissue. In the reported literature the laser energy used range from 100-400mW and the number of burns range from 2-50. The permanent obliteration may require several treatment sessions. The total energy required to complete treatment of the extensive lesions may be substantially more than expected. It is a safer to deliver the treatment over a several treatment sessions in severe cases. The conservative management of increased total treatment energy may minimize the potential risk of corneal decompensation with laser therapy [34]. However, no adverse corneal complications reported to be associated with the laser therapy for iris vascular tufts in the literature so far [29]. Although the main concern is the precipitation of anterior chamber bleeding, no hyphaema has been reported to occur during the laser procedure [29]. The IFA is useful in identifying the extent of the vascular anomalies as it allows accurate treatment in both first and recurrent cases [17]. Bandello F and associates had observed the appearance of fresh vascular anomalies as early as 3 months after laser treatment administered for IMH. Further treatment for these lesions had led to permanent obliteration. Therefore, they emphasized the importance of post-treatment IFA to assess the response to treatment and to detect recurrences [17].

Iridectomy

Amasio et al[31] and Meades et al[24] described the pros and cons of conservative iridectomy in the management of IHA with good post- operative recovery. The authors recommend that this should be considered in cases which are still symptomatic in spite of repeat laser treatment and in cases histological diagnosis is critical to rule out a malignant lesion.

Case Report

We present the following case which was managed according to the above treatment protocol and discuss some of the challenges faced in diagnosis and treatment of IMH.

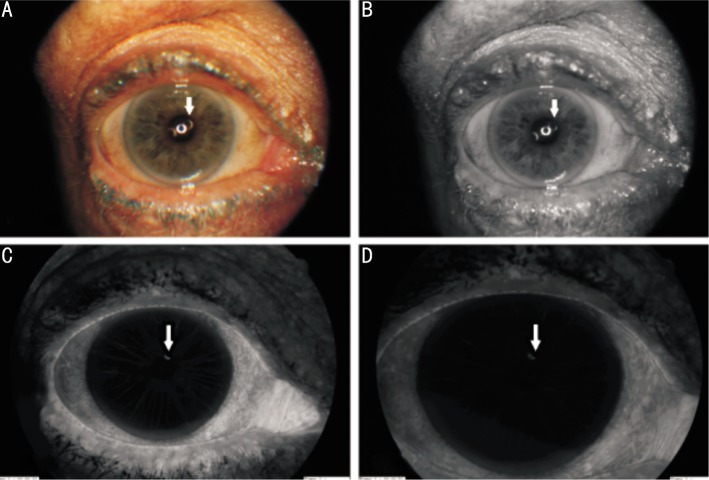

A 68-year-old Caucasian female presented with a long history of intermittent blurring of vision, ocular discomfort and dull aching pain of left eye. Her symptoms were made worse by leaning forward or even reading. Initially, the blurred vision spontaneously improved after a day or two and no abnormality was seen during examination of the eye when seen in the ophthalmic emergency department. She gave a past medical history of well controlled hypertension and was on bendroflumethiazide and aspirin. Due to the transient blurring of vision and given her past-medical history of hypertension she was investigated for amourosis fugax with carotid duplex scan and magnetic resonance angiography (MRA). Both these investigations confirmed that the degree of internal carotid artery narrowing was not significant enough for surgical intervention as per ECST (European Carotid Surgery Trialists' Collaborative Group) criteria. Therefore, she was continued to be managed conservatively by blood pressure control, antiplatelet agents, cholesterol lowering through diet and lifestyle change. During her subsequent visits to the ophthalmic emergency department with transient blurring of vision she was found to have micro-hyphaemas which also caused secondary intraocular pressure rise often requiring oral acetazolamide and topical anti-glaucoma drugs. These episodes of visual disturbances lasted for several days and rarely improved spontaneously. On examination at her most recent visit prior to treatment her visual acuity was Snellen 6/9 in both eyes. The intraocular pressure was within the normal range in between attacks. There was no clinically obvious abnormality in the anterior segment and in the retina. Given the previous episodes of spontaneous hyphaema she underwent an anterior segment fluorescein angiogram which revealed an iris microhaemangiomas (IMH) at the pupil border (Figure 1A-D). Due to the recurrent nature of her symptoms and due to the severity of secondary IOP raise it was decided that she would benefit from argon laser photocoagulation. We used the laser settings recommended for the pre-treatment iridoplasty procedure performed prior to Nd:YAG peripheral iridotomy. We used a 500µm laser spot size and 100mW laser power and 0.5 second of duration and we only needed 8 confluent burns covering the IMH and the feeder vessels in our patient. The laser beam was aimed at an angle so that an inadvertent macula laser burn can be avoided. The fundus and the peripheral retina were examined to confirm that no unintentional retinal laser burns had occurred afterwards. Her symptoms resolved completely within a week and during subsequent follow-up the IMH found to be fibrosed with iris stromal atrophy around it. She had no recurrence of symptoms during the subsequent six month follow up.

Figure 1. Anterior segment photograph of the left eye during Iris Fluorescein Angiogram (IFA) (arrow: the site of the IMH).

A: No obvious abnormality seen on the iris on the colour photograph; B: Red-free photograph of the anterior segment with slit lamp with no obvious abnormality seen on the iris; C: IFA highlighting the IMH of the iris and the feeder-vessel during its early phase; D: IFA highlighting the micro-haemangioma in its late phase.

DISCUSSION

IMHs are convoluted, capillary-like fine vascular loops with thin, delicate, walls which easily break and bleed [5]. They usually occur in the elderly patients in the fifth decade or older [1], [5], [7], [9], [16]. Previous reports have attributed vascular tufts at the papillary margin of the iris to several ophthalmic and systemic disorders and clinicians should have a high degree of suspicion of co-existing IMH in these patients [11]. They are difficult to be identified by slitlamp examination alone and IFA, however, enables demonstration of a larger number of these lesions than are apparent on slitlamp biomicroscopy [1], [4], [9], [14]. The sudden onset visual deterioration is the commonest symptom and sometimes small anterior chamber bleeds rapidly improve spontaneously. There are several reports of misdiagnosis of IMH as ‘mild iritis’, ‘Posner-Schlossman syndrome’ or even amaurosis fugax [2]. Therefore, this condition ought to be considered in the differential diagnosis of patients presenting with transient blurring of vision. Unnecessary investigations and treatment of the carotid circulation may therefore be avoided. After an intraocular bleed the intraocular pressure may remain very high even after rapid resolution of hyphaema and these cases may potentially be misdiagnosed as acute angle closure glaucoma crisis. On the other hand, when patients with shallow anterior chambers presents with IMH due to hyphaema and severely raised IOP it is difficult to say whether the bleeding from the IMH was caused by venous congestion associated with acute angle closure crisis or vice versa. Since some ocular and systemic conditions have been reported to be found more frequently in some patients with IMH the clinicians should always take a good history of past medical conditions and have a high index of suspicion especially in patients with predisposing co-morbidities such as diabetes mellitus or myotonic dystrophy [2]. Often the vascular tufts are bilateral and both eyes should be photographed during IFA [1]. Some patients are asymptomatic and in these patients the vascular tufts can be seen in IFA [1]. Even in symptomatic patients the anterior chamber hyphaema can sometimes be an isolated occurrence and the haemorrhage could spontaneously improve with conservative therapy [1]. In recurrent symptomatic cases with troublesome transient glaucoma the laser photocoagulation is an effective treatment option for this condition but should be carefully administered avoiding the retina and especially the macula. Surgical treatment is fortunately rarely indicated and can be combined with cataract surgery in selected cases. Iridectomy allows histopathological analysis of the biopsy sample and excludes the possibility of a malignant lesion [21]. The authors recommend that the patients experiencing a rare occasional haemorrhage should be conservatively managed. The IFA is the investigation of choice and should be performed in all cases if there are no contraindications. The patients who presents with multiple repeat haemorrhages would be treated with laser coagulation, which if correctly administered, is very effective. We recommend conservative iridectomy in the severely symptomatic cases unresponsive to laser treatment and when the clinical diagnosis is inconclusive requiring a histological diagnosis.

References

- 1.Blanksma LJ, Hooijmans JM. Vascular tufts of the pupillary border causing a spontaneous hyphaema. Ophthalmologica. 1979;178(6):297–302. doi: 10.1159/000308840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ah-Fat FG, Canning CR. Recurrent visual loss secondary to an iris microhaemangioma (letter) Eye. 1994;8(Pt 3):357. doi: 10.1038/eye.1994.75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Akram I, Reck AC, Sheldrick J. Iris microhaemangioma presenting with total hyphema and elevated intraocular pressure. Eye. 2003;17(6):784–785. doi: 10.1038/sj.eye.6700455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Coleman SL, Green WR, Patz A. Vascular tufts of pupillary margin of iris. Am J Ophthalmol. 1977;83(6):881–883. doi: 10.1016/0002-9394(77)90919-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Elgohary MA, Sheldrick JH. Spontaneous hyphaema from pupillary vascular tufts in a patient with branch retinal vein occlusion. Eye (Lond) 2005;19(12):1336–1338. doi: 10.1038/sj.eye.6701756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fechnker PU. Spontaneous hyphaema with abnormal iris vessels. Br J Ophthalmol. 1958;42(5):311–313. doi: 10.1136/bjo.42.5.311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dahlmann AH, Benson MT. Spontaneous hyphema secondary to iris vascular tufts. Arch Ophthalmol. 2001;119(11):1728. doi: 10.1001/archopht.119.11.1728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Francis IC, Kappagoda MB. Iris microhaemangiomas. Aust J Ophthalmol. 1982;10(3):167–171. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cobb B. Vascular tufts at the pupillary margin: a preliminary report on 44 patients. Trans Ophthalmol Soc U K. 1969;88:211–221. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Puri P, Chan J. Cobb's tufts: a rare cause of spontaneous hyphaema. Int Ophthalmol. 2001;24(6):299–300. doi: 10.1023/b:inte.0000006761.23314.22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cobb B, Shilling JS, Chisholm IH. Vascular tufts at the pupillary margin in myotonic dystrophy. Am J Ophthalmol. 1970;69(4):573–582. doi: 10.1016/0002-9394(70)91622-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cota NR, Peckar CO. Spontaneous hyphaema in hereditary haemorrhagic telangiectasia. Br J Ophthalmol. 1998;82(9):1093. doi: 10.1136/bjo.82.9.1090d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Robinson AJ, Izad AA, Noël LP. Recurrent spontaneous microhyphema from iris vascular tufts. Can J Ophthalmol. 2008;43(1):118–119. doi: 10.3129/i07-213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Perry HD, Mallen FJ, Sussman W. Microhaemangiomas of the iris with spontaneous hyphaema and acute glaucoma. Br J Ophthalmol. 1977;61(2):114–116. doi: 10.1136/bjo.61.2.114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Winnick M, Margalit E, Schachat AP, Stark WJ. Treatment of vascular tufts at the pupillary margin before cataract surgery. Br J Ophthalmol. 2003;87(7):920–921. doi: 10.1136/bjo.87.7.920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Podolsky M, Srinivasan BD. Spontaneous hyphema secondary to vascular tuft of pupillary margin of the iris. Arch Ophthalmol. 1979;97(2):301–302. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1979.01020010153012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bandello F, Brancato R, Lattanzio R, Maestranzi G. Laser treatment of iris vascular tufts. Ophthalmologica. 1993;206(4):187–191. doi: 10.1159/000310389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Savir H, Manor RS. Spontaneous hyphema and vessel anomaly. Arch Ophthalmol. 1975;93(10):1056–1058. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1975.01010020830018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sellman A. Hyphaema from microhaemangiomas. Acta Ophthalmol (Copenh) 1972;50(1):58–61. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-3768.1972.tb05641.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Brusini P, Beltrame G. Spontaneous hyphaema from persistent remnant of the pupillary membrane: a case report. Acta Ophthalmol (Copenh) 1983;61(6):1099–1103. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-3768.1983.tb01497.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mason GI. Iris neovascular tufts. Relationship to rubeosis, insulin, and hypotony. Arch Ophthalmol. 1979;97(12):2346–2352. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1979.01020020562014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mason G. Iris neovascular tufts. Ann Ophthalmol. 1980;12(4):420–422. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Krarup JC. Atypical rubeosis iridis in congenital cyanotic heart disease. Report of a case with microhaemangiomas at the pupillary margin causing spontaneous hyphaemas. Acta Ophthalmol (Copenh) 1977;55(4):581–585. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-3768.1977.tb05654.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Meades KV, Francis IC, Kappagoda MB, Filipic M. Light microscopic and electron microscopic histopathology of an iris microhaemangioma. Br J Ophthalmol. 1986;70(4):290–294. doi: 10.1136/bjo.70.4.290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Manor RS, Sachs W. Spontaneous hyphema. Am J Ophthalmol. 1972;74(2):293–295. doi: 10.1016/0002-9394(72)90547-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Laidlaw DA, Bloom PA. Spontaneous hyphaema arising from a strand of persistent pupillary membrane. Eur J Ophthalmol. 1993;3(2):98–100. doi: 10.1177/112067219300300209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bakke EF, Drolsum L. Iris microhaemangiomas and idiopathic juxtafoveolar retinal telangiectasis. Acta Ophthalmol Scand. 2006;84(6):818–822. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0420.2006.00708.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kottow MH. Iris neovascular tufts. Arch Ophthalmol. 1980;98(11):2084. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1980.01020040936035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Welch RB. Spontaneous anterior chamber hemorrhage from the iris: a unique cinematographic documentation. Trans Am Ophthalmol Soc. 1980;78:132–147. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rosen E, Lyons D. Microhaemangiomas at the pupillary border. Am J Ophthalmol. 1969;67(6):846–853. doi: 10.1016/0002-9394(69)90077-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Amasio E, Brovarone FV, Musso M. Angioma of the iris. Ophthalmologica. 1980;180(1):15–18. doi: 10.1159/000308950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Thomas R, Aylward GM, Billson FA. Spontaneous hyphaema from an iris microhaemangioma. Aust N Z J Ophthalmol. 1988;16(4):367–368. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-9071.1988.tb01243.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hagen AP, Williams GA. Argon laser treatment of a bleeding iris vascular tuft. Am J Ophthalmol. 1986;101(3):379–380. doi: 10.1016/0002-9394(86)90839-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Strauss EC, Aldave AJ, Spencer WH, Branco BC, Barsness DA, Calman AF, Margolis TP. Management of prominent iris vascular tufts causing recurrent spontaneous hyphema. Cornea. 2005;24(2):224–226. doi: 10.1097/01.ico.0000141236.33719.04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Goyal S, Foster PJ, Siriwardena D. Iris vascular tuft causing recurrent hyphema and raised IOP: a new indication for laser photocoagulation, angiographic follow-up, and review of laser outcomes. J Glaucoma. 2010;19(5):336–338. doi: 10.1097/IJG.0b013e3181bd899b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]