Abstract

The goal of this study is to employ the HaloTag technology for positron emission tomography (PET), which involves two components: the HaloTag protein (a modified hydrolase which covalently binds to synthetic ligands) and HaloTag ligands (HTLs). 4T1 murine breast cancer cells were stably transfected to express HaloTag protein on the surface (termed as 4T1-HaloTag-ECS, ECS denotes extracellular surface). Two new HTLs were synthesized and termed NOTA-HTL2G-S and NOTA-HTL2G-L (2G indicates second generation, S stands for short, L stands for long, NOTA denotes 1,4,7-triazacyclononane-N,N’N’’-triacetic acid). Microscopy studies confirmed surface expression of HaloTag in 4T1-HaloTag-ECS cells, which specifically bind NOTA-HTL2G-S/L. Uptake of 64Cu-NOTA-HTL2G-L in 4T1-HaloTag-ECS tumors (4.3 ± 0.5, 4.1± 0.2, 4.0 ± 0.2, 2.3 ± 0.1, and 2.2 ± 0.1 %ID/g at 0.5, 3, 6, 18, and 24 h post-injection respectively; n = 4) was significantly higher than that in the 4T1 tumors (3.0 ± 0.3, 3.0± 0.1, 3.0 ± 0.2, 2.0 ± 0.4, and 2.4 ± 0.3 %ID/g at 0.5, 3, 6, 18, and 24 h post-injection respectively; n = 4) at early time points. In comparison, 64Cu-NOTA-HTL2G-S did not demonstrate significant uptake in either 4T1-HaloTag-ECS or 4T1 tumors. Blocking studies and autoradiography of tumor lysates confirmed that 64Cu-NOTA-HTL2G-L binds specifically to HaloTag protein in the 4T1-HaloTag-ECS tumors, corroborated by histology. HaloTag protein-specific targeting and PET imaging in vivo with 64Cu-NOTA-HTL2G-L serves as a proof-of-principle for future non-invasive and sensitive tracking of HaloTag-transfected cells with PET, as well as many other studies of gene/protein/cell function in vivo.

Keywords: HaloTag, positron emission tomography (PET), reporter gene, 64Cu, cancer, molecular imaging

Introduction

As a versatile tool, the HaloTag technology has attracted much attention for a broad array of biomedical applications such as in vitro optical imaging [1-3], in vivo cell labeling/imaging [4,5], protein purification/trafficking [6,7], study of protein-protein and protein-DNA interactions [8], analysis of protein stability [9], high-throughput assays [10], single molecule force spectroscopy [11], ribosome tagging [12], among many others [13]. The HaloTag technology involves two key components: the HaloTag protein and HaloTag ligands (HTLs).

The HaloTag protein is a modified bacterial hydrolase that was designed to covalently bind to synthetic HTLs [14,15]. The attractive features for its use as a reporter include its small size (33 kDa) and lack of cross-reactive interference with the endogenous mammalian biochemistry, since the protein is not common to mammalian cells. A typical HTL is composed of a chloroalkane, which can be flexible in its structure, and a functional tag (e.g. dye, affinity ligand, solid surface, radioisotope, etc.) depending on the specific applications [13,14]. Covalent bond formation between the HaloTag protein and the chloroalkane within a HTL occurs rapidly under physiological conditions, which is essentially irreversible and highly specific.

Among the many molecular imaging strategies available, reporter gene-based approaches continue to be a vibrant area of research [16]. A number of these reporter genes and corresponding reporter probes have been designed and optimized, and several of them are already under clinical investigation [16-18]. Commonly used reporter genes include those that can be detected with optical [19,20], single-photon emission computed tomography (SPECT) and positron emission tomography (PET) [21], or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) techniques [22].

The goal of this study is to employ HaloTag as a PET reporter gene, using our newly designed 2nd generation HTLs that can be labeled with 64Cu (t1/2: 12.7 h) via the 1, 4, 7-triazacyclononane-N, N’, N’’-triacetic acid (NOTA) chelator. Hydrophilic polyethylene glycol (PEG) chains of different length were incorporated into the HTLs and compared using mice bearing 4T1 murine breast tumors stably expressing the HaloTag protein on the cell surface. Since PET is highly quantitative, sensitive, non-invasive, and clinically relevant [23-25], this technique may be used for future non-invasive tracking of HaloTag-transfected cells with PET, as well as many other applications such as cancer imaging and therapy.

Materials and methods

Reagents

2-S-(4-isothiocyanatobenzyl)-1,4,7-triazacyclononane-1,4,7-triacetic acid (p-SCN-Bn-NOTA) was purchased from Macrocyclics, Inc. (Dallas, TX). Water and all buffers were of Millipore grade and pre-treated with Chelex 100 resin (50-100 mesh; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) to ensure that the aqueous solutions were heavy-metal free. PD-10 desalting columns were purchased from GE Healthcare (Piscataway, NJ). High-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) solvents (water, acetonitrile, and trifluoroacetic acid [TFA]) were purchased from Thermo Fisher Scientific (Fair Lawn, NJ). 64Cu was produced via a 64Ni(p,n)64Cu reaction using a CTI RDS 112 cyclotron at the University of Wisconsin - Madison. All other reagents were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich, except when noted in the following text, and used as received.

Syntheses of the HTLs

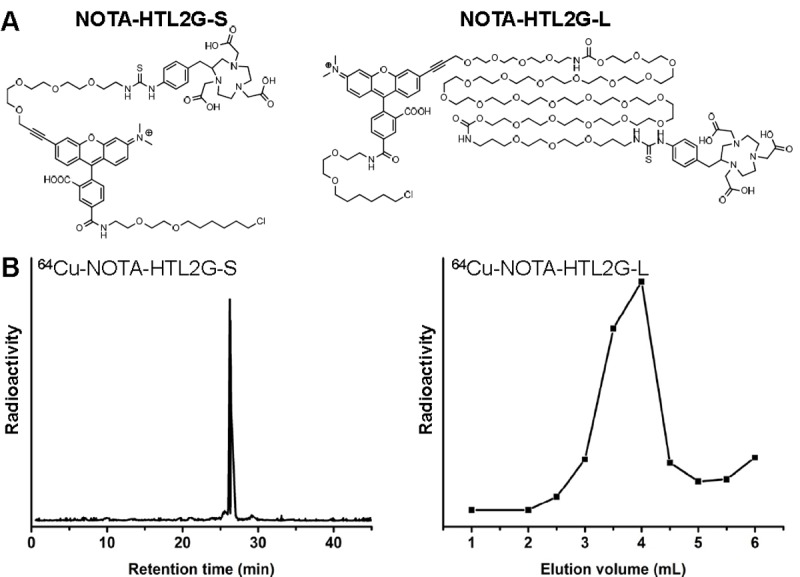

Syntheses of the two NOTA-conjugated HTLs (Figure 1A) were straightforward. Since the HaloTag-reactive chloroalkane was very hydrophobic, PEG chains with different length (3, and > 25 ethylene glycol units) were incorporated between the chloroalkane and NOTA. The two compounds were purified by HPLC, and subsequently characterized with 1H-NMR spectroscopy and mass spectrometry. For NOTA-HTL2G-S (2G denotes second generation and S denotes short), the m/z was calculated to be 1272.53 (C64H83ClN7O16S+) and an m/z of 1272.7 was observed in mass spectrometry. For NOTA-HTL2G-L (L denotes long with > 25 ethylene glycol units), which was purified to homogeneity as a single peak by HPLC, a range of peaks were observed which were separated by 44 Da (i.e., one ethylene glycol unit), characteristic for PEG-containing compounds.

Figure 1.

A. Chemical structures of NOTA-HTL2G-S and NOTA-HTL2G-L. B. HPLC trace of 64Cu-NOTA-HTL2G-S and size exclusion column chromatography profile of 64Cu-NOTA-HTL2G-L (base line separation was achieved).

Stable transfection of 4T1 cells with HaloTag

4T1 murine breast cancer cells were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC, Manassas, VA) and cultured in the RPMI 1640 medium (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, and incubated at 37°C with 5% CO2. pCI-neo mammalian expression vector (E1841, Promega, Madison, WI) was used for cloning of the HaloTag construct, which was fused to a single transmembrane domain of β1 integrin. G418 (V8091, Promega, Madison, WI) was used for selection of the clones. When the cells under selective pressure were expanding at the same rate as non-transfected controls, they were serially diluted and single colonies were harvested and confirmed positive by microscopy studies.

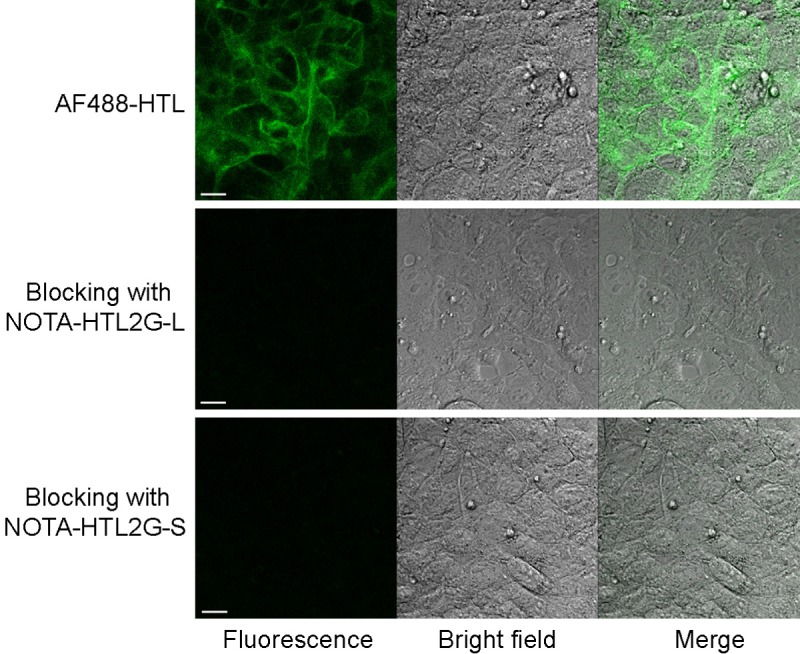

Microscopy studies were performed after labeling the transfected 4T1 cells with AlexaFluor 488-conjugated HTL (AF488-HTL, Promega, Madison, WI), which is not cell membrane permeable and therefore only labels the HaloTag protein expressed on the extracellular surface. One positive clone with stable HaloTag expression was selected, expanded, and termed as “4T1-HaloTag-ECS” (ECS denotes extracellular surface). The 4T1-HaloTag-ECS cells were used for all subsequent in vitro and in vivo experiments when it reached ~80% confluence in culture.

Cellular studies of NOTA-HTL2G-S/L

NOTA-HTL2G-L and NOTA-HTL2G-S were investigated in 4T1-HaloTag-ECS cells for their ability to bind to the HaloTag protein on the surface of these cells. The cells were plated in Lab-Tek II chambered cover glass (Nalge Nunc International) and allowed to attach overnight. To assess the HaloTag protein binding ability of NOTA-HTL2G-S/L, 4T1-HaloTag-ECS cells were first incubated in a 5 μM solution of NOTA-HTL2G-S/L (i.e. blocking) in complete media for 15 minutes at 37°C in the presence of 5% CO2. Afterwards, the cells were labeled with 1 μM of AF488-HTL for 15 minutes and examined under an Olympus FV500 confocal microscope equipped with a 37°C + 5% CO2 environmental chamber and appropriate filter sets. Control 4T1-HaloTag-ECS cells were labeled with 1 μM of AF488-HTL only before microscopy studies.

Animal model

All animal studies were conducted under a protocol approved by the University of Wisconsin Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. To generate the tumor model, four- to five-week-old female BALB/c mice were purchased from Harlan (Indianapolis, IN) and tumors were established by subcutaneously injecting 2 × 106 cells, suspended in 100 μL of RPMI 1640, into the front flanks of mice (left: 4T1; right: 4T1-HaloTag-ECS). The tumor sizes were monitored every other day and mice were subjected to in vivo experiments when the tumor diameter reached 5-8 mm (~10 days after inoculation).

64Cu-labeling

64CuCl2 (111 MBq) was diluted in 300 μL of 0.1 M sodium acetate buffer (pH 6.5) and added to 15 μg of NOTA-HTL2G-S/L. The reaction mixture was incubated for 30 min at 37°C with constant shaking. 64Cu-NOTA-HTL2G-L was purified using PD-10 columns with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) as the mobile phase, whereas 64Cu-NOTA-HTL2G-S was purified by a Dionex Ultimate 3000 HPLC system equipped with radioactivity and UV detectors using a C-18 column (Figure 1B). A solvent gradient (A: water with 0.1% TFA; B: acetonitrile with 0.1% TFA) was used, where solvent B was gradually increased from 5% to 75% over a period of 30 min. After collection of the radioactive peak, acetonitrile was removed from the solution with continuous argon flow. The remaining solution was reconstituted into a final concentration of 1 × PBS. The purified 64Cu-NOTA-HTL2G-S/L solution was passed through a 0.2 μm syringe filter before in vivo experiments.

PET imaging and biodistribution studies

Details of the PET scans, region-of-interest (ROI) analysis, and biodistribution studies have been reported previously [26-28]. Briefly, each tumor-bearing mouse was injected with 5-10 MBq of PET tracer via tail vein and 3 - 10 min static PET scans were performed at various time points post-injection (p.i.) in a microPET/microCT Inveon rodent model scanner (Siemens Medical Solutions USA, Inc.). The images were reconstructed using a maximum a posteriori (MAP) algorithm, with no attenuation or scatter correction. ROI analysis was performed on all PET images to obtain quantitative data in the unit of percentage of injected dose per gram of tissue (%ID/g). Blocking studies were carried out for 64Cu-NOTA-HTL2G-L to evaluate its HaloTag specificity in vivo, where a group of 4 mice was each injected with 2 mg of NOTA-HTL2G-L simultaneously with 5-10 MBq of 64Cu-NOTA-HTL2G-L.

After the last PET scans at 24 h p.i., mice were euthanized and biodistribution studies were carried out to confirm that the quantitative tracer uptake values based on microPET imaging accurately represented tracer distribution in tumor-bearing mice. Another cohort of four mice was euthanized at 3 h p.i. (when uptake of 64Cu-NOTA-HTL2G-L peaks in the 4T1-HaloTag-ECS tumors based on PET) for biodistribution studies. The radioactivity in the tumor and major organs was measured with a gamma-counter (Perkin Elmer) and presented as %ID/g (mean ± SD).

Histology

Frozen tumor slices of 7 μm thickness were fixed with cold acetone for 10 min and dried in the air for 30 min. After rinsing with PBS and blocking with 10% donkey serum for 30 min at room temperature, the slices were incubated with rabbit anti-HaloTag polyclonal antibody (Promega, Madison, WI) at a concentration of 2 μg/mL for 1 h at 4°C and visualized using AlexaFluor488-labeled donkey anti-rabbit IgG. After washing with PBS, the tissue slices were also stained for endothelial marker CD31 as described previously [29]. After final wash with PBS, all images were acquired with a Nikon Eclipse Ti microscope.

Electrophoresis and autoradiography

To confirm the specificity of 64Cu-NOTA-HTL2G-L for HaloTag in vivo, both 4T1-HaloTag-ECS and 4T1 tumors from the same mouse were harvested at 3 h p.i. of the tracer. The tumor tissues were homogenized and lysed with radioimmunoprecipitation assay (RIPA) buffer (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.). After centrifugation, the supernatant protein solution was analyzed with sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE, 5% stacking gel and 8% resolving gel) under non-reducing conditions with 100 μg of total protein loading per lane (the amount of total protein was quantified with Coomassie Brilliant Blue G-250). After 1 h running time, the gel was placed on a phosphorimaging film for high resolution autoradiography. After overnight exposure, the films were scanned in a Cyclone Storage Phosphor Screen System (Perkin Elmer, Branford, CT).

Statistical analysis

Quantitative data were expressed as mean ± SD. Means were compared using Student’s t-test. P values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

Investigation of NOTA-HTL2G-S/L in 4T1-HaloTag-ECS cells

Both NOTA-HTL2G-S and NOTA-HTL2G-L contain several ethylene glycol units (Figure 1A), which can improve the hydrophilicity and pharmacokinetics of the HTLs since the chloroalkane is very hydrophobic. Compared with the first generation HTLs [26], the presence of multiple aromatic rings (which was a fluorescent dye but no longer fluorescent in the current form) in the NOTA-HTL2G-S/L improved HaloTag binding in cells. HaloTag protein expression in the 4T1-HaloTag-ECS cells (membrane bound and faces the outside of the cell) was confirmed by labeling with AF488-HTL, an established high affinity ligand for HaloTag that is not cell membrane permeable (Figure 2). Saturating the HaloTag protein on the 4T1-HaloTag-ECS cells with either NOTA-HTL2G-S or NOTA-HTL2G-L prior to incubation with AF488-HTL (i.e., blocking) led to negligible fluorescence signal on the cells, which confirmed that both NOTA-HTL2G-S and NOTA-HTL2G-L bind to HaloTag protein with high affinity in cell culture.

Figure 2.

4T1-HaloTag-ECS cells are labeled with AF488-HTL (cell impermeable ligand) to confirm surface expression of HaloTag. Blocking with either NOTA-HTL2G-L or NOTA-HTL2G-S prior to incubation with AF488-HTL led to significantly lower fluorescence signal, confirming HaloTag specific binding of both ligands. Scale bar: 20 μm.

64Cu-labeling

For NOTA-HTL2G-S, 64Cu-labeling including HPLC purification took 100 ± 10 min (n = 4). The crude radio-HPLC profile of 64Cu-NOTA-HTL2G-S is shown in Figure 1B, which has a sharp peak with a retention time of 27.6 min. For NOTA-HTL2G-L, 64Cu-labeling including purification using PD-10 columns took 70 ± 10 min (n = 8), with a representative radioactivity elution profile from the column shown in Figure 1B. After purification with HPLC or PD-10 column, the decay-corrected radiochemical yield was > 80% for 64Cu-NOTA-HTL2G-L and ~25% for 64Cu-NOTA-HTL2G-S, both with radiochemical purity of > 98%.

PET imaging

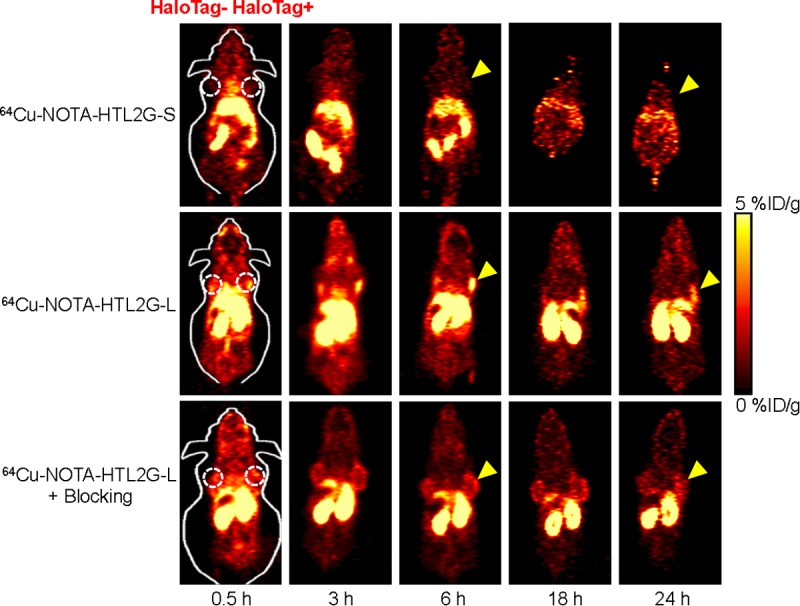

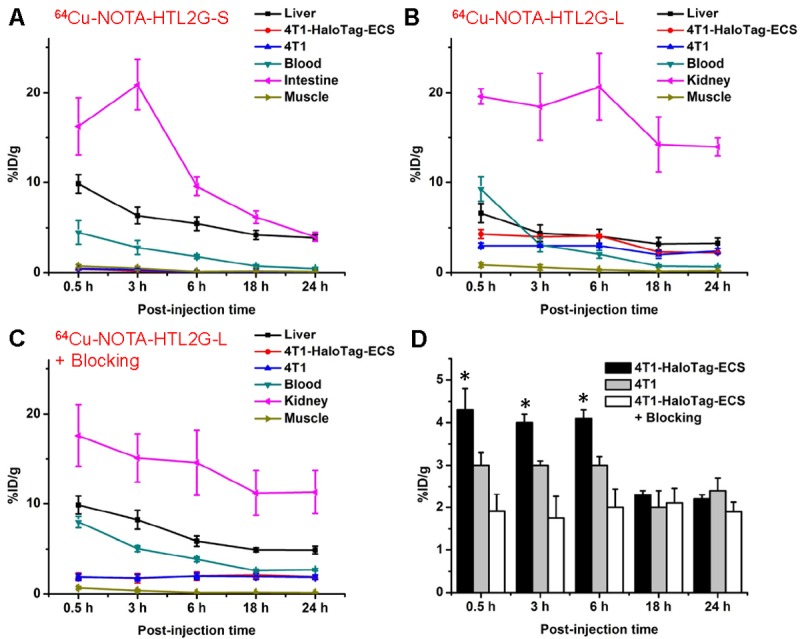

Based on the low molecular weight of 64Cu-NOTA-HTL2G-S/L, which typically undergo fast blood clearance and excretion, the time points of 0.5, 3, 6, 18, and 24 h were chosen for serial PET scans after intravenous injection of each tracer. Representative coronal slices of mice bearing both 4T1-HaloTag-ECS (right) and 4T1 (left) tumors are shown in Figure 3, and the quantitative data obtained from ROI analysis of the PET images are shown in Figure 4.

Figure 3.

Serial coronal PET images of mice bearing both 4T1 (left) and 4T1-HaloTag-ECS (right) tumors at different time points post-injection of 64Cu-NOTA-HTL2G-S, 64Cu-NOTA-HTL2G-L, or 64Cu-NOTA-HTL2G-L with a blocking dose of NOTA-HTL2G-L. Images are representative of 4 mice per group and arrowheads indicate the 4T1-HaloTag-ECS tumors.

Figure 4.

Time-activity curves of the liver, 4T1-HaloTag-ECS tumor, 4T1 tumor, blood, intestine/kidney, and muscle after intravenous injection of 64Cu-NOTA-HTL2G-S (A), 64Cu-NOTA-HTL2G-L (B), or 64Cu-NOTA-HTL2G-L with a blocking dose of NOTA-HTL2G-L (C). D. Tumor uptake of 64Cu-NOTA-HTL2G-L in different groups. *: P < 0.05 (n = 4).

Uptake of 64Cu-NOTA-HTL2G-S in the abdomen area (especially in intestines) was prominent at all time points examined, which is typically observed for hydrophobic PET tracers. The intestine uptake of 64Cu-NOTA-HTL2G-S was 16.3 ± 3.2, 20.9 ± 2.8, 9.6 ± 1.0, 6.2 ± 0.7, and 4.0 ± 0.5 %ID/g at 0.5, 3, 6, 18, and 24 h p.i. respectively (n = 4; Figure 4A). The tracer was cleared rapidly from the circulation, with < 5%ID/g of radioactivity in the blood at 0.5 h p.i. The uptake of 64Cu-NOTA-HTL2G-S in 4T1-HaloTag-ECS tumor was very low at all time points examined (0.4 ± 0.1, 0.2 ± 0.02, 0.05 ± 0.01, 0.02 ± 0.01, and 0.005 ± 0.001 %ID/g at 0.5, 3, 6, 18, and 24 h p.i. respectively; n = 4; Figure 4A).

With significantly lower hydrophobicity than 64Cu-NOTA-HTL2G-S, the intestine uptake of 64Cu-NOTA-HTL2G-L was much lower since it undergoes primarily renal instead of hepatobiliary clearance (Figure 3). 64Cu-NOTA-HTL2G-L also exhibited longer circulation life time than 64Cu-NOTA-HTL2G-S, with a blood radioactivity level of ~10 %ID/g at 0.5 h p.i. The kidney uptake of 64Cu-NOTA-HTL2G-L was 19.6 ± 0.9, 18.5 ± 3.7, 20.7 ± 3.7, 14.2 ± 3.1, and 13.9 ± 1.0 %ID/g at 0.5, 3, 6, 18, and 24 h p.i. respectively (n = 4; Figure 4B). Importantly, the 4T1-HaloTag-ECS tumor uptake of 64Cu-NOTA-HTL2G-L is prominent at 4.3 ± 0.5, 4.1± 0.2, 4.0 ± 0.2, 2.3 ± 0.1, and 2.2 ± 0.1 %ID/g at 0.5, 3, 6, 18, and 24 h p.i. respectively (n = 4; Figure 4B and 4D), which was significantly higher than the uptake in HaloTag-negative 4T1 tumors (3.0 ± 0.3, 3.0± 0.1, 3.0 ± 0.2, 2.0 ± 0.4, and 2.4 ± 0.3 %ID/g at 0.5, 3, 6, 18, and 24 h p.i. respectively (n = 4; P < 0.05 at 0.5, 3, and 6 h p.i.).

Administering a blocking dose of NOTA-HTL2G-L with 64Cu-NOTA-HTL2G-L injection significantly reduced the 4T1-HaloTag-ECS tumor uptake to 1.9 ± 0.4, 1.8 ± 0.5, 2.0 ± 0.4, 2.1 ± 0.4, and 1.9 ± 0.2 %ID/g at 0.5, 3, 6, 18, and 24 h p.i respectively (n = 4; P < 0.05 before 18 h p.i.; Figures 3, 4C and 4D), which demonstrated that 64Cu-NOTA-HTL2G-L maintained HaloTag specificity in vivo. Liver/kidney uptake of 64Cu-NOTA-HTL2G-L in the “blocking” group was similar to mice injected with 64Cu-NOTA-HTL2G-L alone, and radioactivity level in the blood was also similar between the two groups (Figure 4B and 4C). Tumor uptake of 64Cu-NOTA-HTL2G-L in the various groups based on ROI analysis of the PET data are summarized in Figure 4D, where the %ID/g values in the 4T1-HaloTag-ECS tumors were significantly higher than the other two groups (i.e., 4T1 or “4T1-HaloTag-ECS + blocking”) at 0.5, 3, and 6 h p.i. At 18 and 24 h p.i., most of the tracer has been cleared from the mice and the differences in tumor uptake of 64Cu-NOTA-HTL2G-L were no long statistically significant.

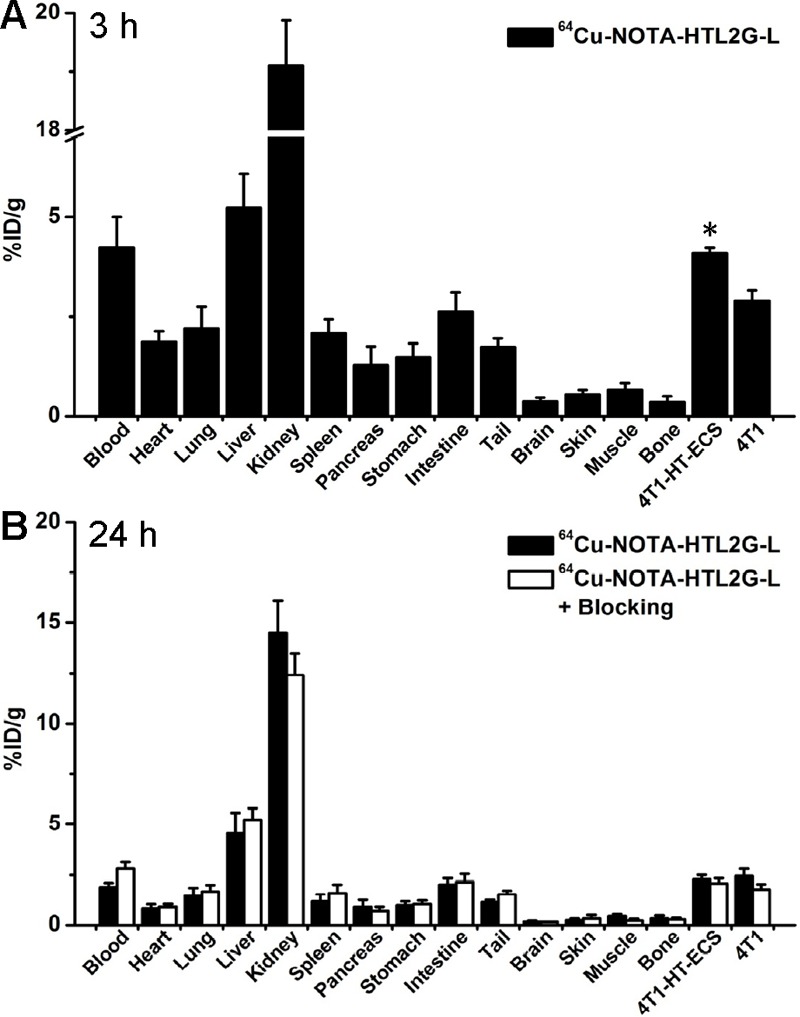

Biodistribution studies

A cohort of four mice bearing both 4T1-HaloTag-ECS and 4T1 tumors was intravenously injected with 64Cu-NOTA-HTL2G-L and euthanized at 3 h p.i. (when tumor uptake was at the peak based on PET results) for biodistribution studies. Both the liver and kidneys (i.e. the clearance organs for the tracer) had significant tracer uptake at 3 h p.i. for 64Cu-NOTA-HTL2G-L (Figure 5A). More importantly, the 4T1-HaloTag-ECS tumor uptake of 64Cu-NOTA-HTL2G-L was higher than all major organs except the liver and kidneys, thus providing good tumor contrast and confirmed specific HaloTag targeting (i.e. significantly higher tracer uptake than in the 4T1 tumors). After the last PET scans at 24 h p.i., the mice were euthanized for biodistribution studies to validate the in vivo PET data. The kidneys and liver had significant tracer uptake at 24 h p.i. for 64Cu-NOTA-HTL2G-L, and the tumor uptake was still prominent (Figure 5B). Overall, the biodistribution data was in good agreement with the quantitative data obtained from ROI analysis of the non-invasive PET scans.

Figure 5.

Biodistribution of 64Cu-NOTA-HTL2G-L at 3 h (A) and 24 h (B) post-injection in mice bearing both 4T1-HaloTag-ECS and 4T1 tumors (n = 4). *P < 0.05.

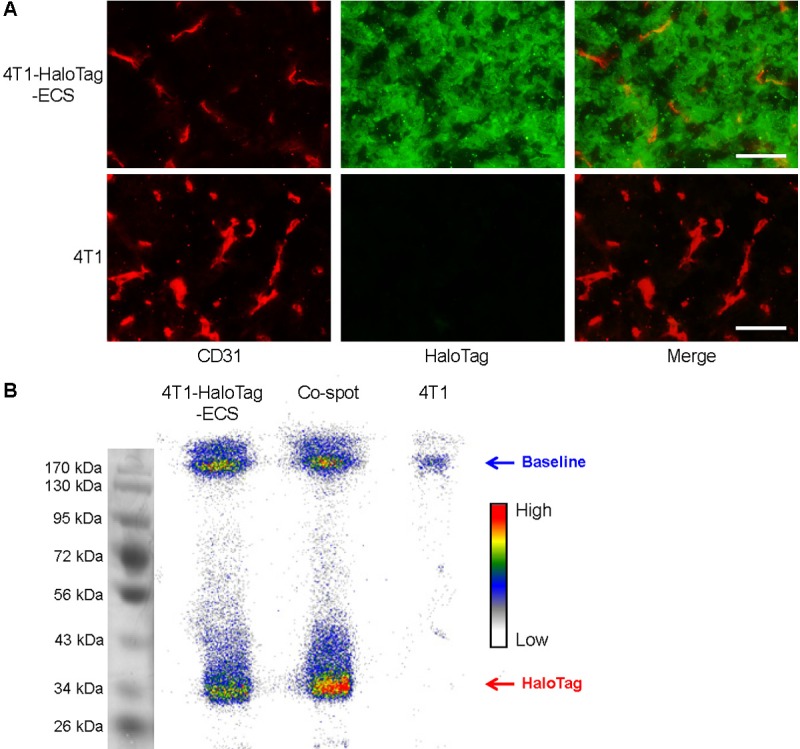

Ex vivo studies

Immunofluorescence HaloTag and CD31 (marker for vessels) staining of tumor slices indicated strong HaloTag expression in the 4T1-HaloTag-ECS tumor, but not the 4T1 tumor, confirming stable transfection of the cells with HaloTag which remained persistent after inoculation into immunocompetent mice (Figure 6A). Therefore, higher uptake of 64Cu-NOTA-HTL2G-L in the 4T1-HaloTag-ECS tumors than in the 4T1 tumors, which are identical except for the expression level of HaloTag, confirmed the in vivo specificity and affinity of 64Cu-NOTA-HTL2G-L for the HaloTag protein.

Figure 6.

A. Immunofluorescence HaloTag/CD31 double-staining of the 4T1-HaloTag-ECS and 4T1 tumor slices. Green: HaloTag; red: CD31. All images were acquired under the same conditions and displayed at the same scale. Scale bars: 50 μm. B. Autoradiography after SDS-PAGE separation of 4T1-HaloTag-ECS or 4T1 tissue lysates at 3 h post-injection of 64Cu-NOTA-HTL2G-L. A mixture of the two tissue lysates were loaded in the center lane and denoted as “co-spot”.

Autoradiography of whole tumor lysates after SDS-PAGE separation clearly indicated the strong association between 64Cu-NOTA-HTL2G-L and cell surface HaloTag protein. The radioactivity band for 4T1-HaloTag-ECS tumor lysate was at the expected molecular weight of ~33 kDa for HaloTag protein, while the corresponding band in the 4T1 tumor lysate was undetectable (Figure 6B). Most radioactivity for the 4T1 tumor lysate is seen at the baseline, which is likely attributed to non-specific accumulation of 64Cu-NOTA-HTL2G-L in the 4T1 tumor. An appreciable amount of radioactivity in the 4T1-HaloTag-ECS tumor lysate is also seen at the baseline, consistent with the in vivo PET data (i.e., tumor uptake of 64Cu-NOTA-HTL2G-L is composed of significant amount of non-specific accumulation as well as specific HaloTag binding). Loading a mixture of the two tumor lysates into the same lane (termed as “co-spot”) did not alter the location of radioactivity bands.

Discussion

In this work, we investigated the use of two 2nd generation HTLs for PET imaging of HaloTag-expressing tumors in vivo. Non-invasive imaging with reporter genes is technically challenging and low level of tumor uptake is common, most of which are less than a few %ID/g [16]. To achieve sufficient tumor contrast, 64Cu-labeled HTLs need to circulate in the blood for a sufficient time period, extravasate, bind to HaloTag protein expressed on the surface of 4T1-HaloTag-ECS cells, and undergo covalent linkage through enzymatic reaction to prevent rapid washout from the tumor. Given the short circulation lifetime of these HTLs, all these processes must happen rapidly while the unbound tracers undergo renal and/or hepatobiliary clearance. Although 64Cu-NOTA-HTL2G-S exhibited specific binding to HaloTag protein in cell culture, it did not give significant tumor uptake in mice bearing 4T1-HaloTag-ECS tumors presumably due to its hydrophobicity and short circulation life time. Therefore, this study was mainly focused on 64Cu-NOTA-HTL2G-L, which exhibited HaloTag-specific binding both in vitro and in vivo.

As the circulation half-lives of both HTLs are relatively short (< 1 h based on blood radioactivity level), tumor uptake at the early time points (0.5, 3, and 6 h p.i., during which specific binding is taking place) can provide more meaningful insights regarding HaloTag specificity of 64Cu-NOTA-HTL2G-L in vivo. Inclusion of the PET and biodistribution data at 18 and 24 h p.i. was primarily for evaluation of tracer clearance over time. Since binding to the HaloTag protein does not lead to subsequent internalization and intracellular retention of 64Cu-NOTA-HTL2G-L, tumor uptake at late time points (18 & 24 h p.i.) is significantly lower than the early time points due to possible metabolism and clearance of extracellular 64Cu. Nonetheless, tumor uptake of 64Cu-NOTA-HTL2G-L is much higher (> 4%ID/g vs. < 2%ID/g) compared with 64Cu-labeled 1st generation HTL, which has similar structure but lacks the aromatic component [26].

Although 4T1-HaloTag-ECS tumor uptake of 64Cu-NOTA-HTL2G-L was partly attributed to passive targeting, as suggested by appreciable tracer uptake in the 4T1 tumors that do not express HaloTag, substantial amount of tumor uptake was indeed HaloTag specific as confirmed by ex vivo histology/autoradiography studies (Figure 6), as well as significantly lower tumor uptake when a large dose of NOTA-HTL2G-L was co-injected to saturate the HaloTag on 4T1-HaloTag-ECS cell surface. A few strategies may be employed to improve the pharmacokinetics, absolute tumor uptake, and tumor retention of radiolabeled HTLs in the future. First, the expression level of HaloTag protein was only moderate in the 4T1-HaloTag-ECS cells. Further increasing the HaloTag protein expression level on the extracellular surface may lead to higher tumor uptake in subsequent studies. Second, multimerization may be investigated to improve tracer uptake and retention, which has been widely adopted for peptide- and small molecule-based imaging agents [30,31].

Combining multiple imaging techniques can provide synergistic information and allow scientists to interrogate various biological events from different angles. Multimodal reporter genes in the literature typically rely on the fusion of different reporter proteins that can each be used for single modality imaging [16,32]. However, fusion of multiple reporter proteins is technically challenging and the overall larger size may also affect the expression and/or function of each reporter protein. HaloTag can potentially serve as a multimodality reporter gene using a single small protein of 33 kDa. Previous reports have demonstrated the use of HaloTag protein for in vivo optical imaging [5], and herein we report its application in PET imaging. The advantages of PET over optical techniques for non-invasive imaging include better tissue penetration of signal, higher clinical relevance, enhanced quantitation accuracy, etc. [33-36]. Similar chloroalkane-containing HTLs may also be labeled with different image tags, such as 99mTc for SPECT and Gd3+ for MRI. Lastly, a major potential application of HaloTag-based reporter gene imaging is to non-invasively track cells in vivo, independent of the cell types (e.g. immune cells, stem cells, cancer cells, induced pluripotent stem cells, etc. [37-39]), which can provide important biological insights in many research areas.

In conclusion, we have demonstrated that the HaloTag protein can be used as a reporter gene for PET imaging in vivo using a murine tumor model stably transfected with HaloTag on the extracellular surface. HaloTag protein-specific targeting and PET imaging in vivo was achieved with 64Cu-NOTA-HTL2G-L, which serves as a proof-of-principle for future non-invasive and sensitive tracking of HaloTag-transfected cells with PET, as well as many other studies of gene/protein/cell function in vivo.

Acknowledgments

This work is supported, in part, by the University of Wisconsin Carbone Cancer Center, University of Wisconsin Graduate School, the Department of Defense (W81XWH-11-1-0644), the Elsa U. Pardee Foundation, and Promega Corporation.

References

- 1.Liu DS, Phipps WS, Loh KH, Howarth M, Ting AY. Quantum Dot Targeting with Lipoic Acid Ligase and HaloTag for Single-Molecule Imaging on Living Cells. ACS Nano. 2012;6:11080–11087. doi: 10.1021/nn304793z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zhang Y, So MK, Loening AM, Yao H, Gambhir SS, Rao J. HaloTag protein-mediated site-specific conjugation of bioluminescent proteins to quantum dots. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2006;45:4936–4940. doi: 10.1002/anie.200601197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Takemoto K, Matsuda T, McDougall M, Klaubert DH, Hasegawa A, Los GV, Wood KV, Miyawaki A, Nagai T. Chromophore-Assisted Light Inactivation of HaloTag Fusion Proteins Labeled with Eosin in Living Cells. ACS Chem Biol. 2011;6:401–406. doi: 10.1021/cb100431e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schroder J, Benink H, Dyba M, Los GV. In vivo labeling method using a genetic construct for nanoscale resolution microscopy. Biophys J. 2009;96:L01–03. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2008.09.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kosaka N, Ogawa M, Choyke PL, Karassina N, Corona C, McDougall M, Lynch DT, Hoyt CC, Levenson RM, Los GV, Kobayashi H. In vivo stable tumor-specific painting in various colors using dehalogenase-based protein-tag fluorescent ligands. Bioconjug Chem. 2009;20:1367–1374. doi: 10.1021/bc9001344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ohana RF, Hurst R, Vidugiriene J, Slater MR, Wood KV, Urh M. HaloTag-based purification of functional human kinases from mammalian cells. Protein Expr Purif. 2011;76:154–164. doi: 10.1016/j.pep.2010.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Svendsen S, Zimprich C, McDougall MG, Klaubert DH, Los GV. Spatial separation and bidirectional trafficking of proteins using a multi-functional reporter. BMC Cell Biol. 2008;9:17. doi: 10.1186/1471-2121-9-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Urh M, Hartzell D, Mendez J, Klaubert DH, Wood K. Methods for detection of protein-protein and protein-DNA interactions using HaloTag. Methods Mol Biol. 2008;421:191–209. doi: 10.1007/978-1-59745-582-4_13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yamaguchi K, Inoue S, Ohara O, Nagase T. Pulse-chase experiment for the analysis of protein stability in cultured mammalian cells by covalent fluorescent labeling of fusion proteins. Methods Mol Biol. 2009;577:121–131. doi: 10.1007/978-1-60761-232-2_10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hartzell DD, Trinklein ND, Mendez J, Murphy N, Aldred SF, Wood K, Urh M. A functional analysis of the CREB signaling pathway using HaloCHIP-chip and high throughput reporter assays. BMC Genomics. 2009;10:497. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-10-497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Taniguchi Y, Kawakami M. Application of HaloTag protein to covalent immobilization of recombinant proteins for single molecule force spectroscopy. Langmuir. 2010;26:10433–10436. doi: 10.1021/la101658a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhou ZP, Shimizu Y, Tadakuma H, Taguchi H, Ito K, Ueda T. Single molecule imaging of the trans-translation entry process via anchoring of the tagged ribosome. J Biochem. 2011;149:609–618. doi: 10.1093/jb/mvr010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Urh M, Rosenberg M. HaloTag, a Platform Technology for Protein Analysis. Curr Chem Genomics. 2012;6:72–78. doi: 10.2174/1875397301206010072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Los GV, Wood K. The HaloTag: a novel technology for cell imaging and protein analysis. Methods Mol Biol. 2007;356:195–208. doi: 10.1385/1-59745-217-3:195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Los GV, Encell LP, McDougall MG, Hartzell DD, Karassina N, Zimprich C, Wood MG, Learish R, Ohana RF, Urh M, Simpson D, Mendez J, Zimmerman K, Otto P, Vidugiris G, Zhu J, Darzins A, Klaubert DH, Bulleit RF, Wood KV. HaloTag: a novel protein labeling technology for cell imaging and protein analysis. ACS Chem Biol. 2008;3:373–382. doi: 10.1021/cb800025k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kang JH, Chung JK. Molecular-genetic imaging based on reporter gene expression. J Nucl Med. 2008;49(Suppl 2):164S–179S. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.107.045955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jacobs A, Voges J, Reszka R, Lercher M, Gossmann A, Kracht L, Kaestle C, Wagner R, Wienhard K, Heiss WD. Positron-emission tomography of vector-mediated gene expression in gene therapy for gliomas. Lancet. 2001;358:727–729. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(01)05904-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yaghoubi SS, Jensen MC, Satyamurthy N, Budhiraja S, Paik D, Czernin J, Gambhir SS. Noninvasive detection of therapeutic cytolytic T cells with 18F-FHBG PET in a patient with glioma. Nat Clin Pract Oncol. 2009;6:53–58. doi: 10.1038/ncponc1278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Giepmans BN, Adams SR, Ellisman MH, Tsien RY. The fluorescent toolbox for assessing protein location and function. Science. 2006;312:217–224. doi: 10.1126/science.1124618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Contag CH, Bachmann MH. Advances in in vivo bioluminescence imaging of gene expression. Annu Rev Biomed Eng. 2002;4:235–260. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bioeng.4.111901.093336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Min JJ, Gambhir SS. Molecular imaging of PET reporter gene expression. Handb Exp Pharmacol. 2008:277–303. doi: 10.1007/978-3-540-77496-9_12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gilad AA, Ziv K, McMahon MT, van Zijl PC, Neeman M, Bulte JW. MRI reporter genes. J Nucl Med. 2008;49:1905–1908. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.108.053520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gambhir SS. Molecular imaging of cancer with positron emission tomography. Nat Rev Cancer. 2002;2:683–693. doi: 10.1038/nrc882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cai W, Hong H. Peptoid and positron emission tomography: an appealing combination. Am J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2011;1:76–79. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Grassi I, Nanni C, Allegri V, Morigi JJ, Montini GC, Castellucci P, Fanti S. The clinical use of PET with 11C-acetate. Am J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2012;2:33–47. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hong H, Benink HA, Zhang Y, Yang Y, Uyeda HT, Engle JW, Severin GW, McDougall MG, Barnhart TE, Klaubert DH, Nickles RJ, Fan F, Cai W. HaloTag: a novel reporter gene for positron emission tomography. Am J Transl Res. 2011;3:392–403. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhang Y, Hong H, Engle JW, Yang Y, Barnhart TE, Cai W. Positron emission tomography and near-infrared fluorescence imaging of vascular endothelial growth factor with dual-labeled bevacizumab. Am J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2012;2:1–13. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhang Y, Hong H, Severin GW, Engle JW, Yang Y, Goel S, Nathanson AJ, Liu G, Nickles RJ, Leigh BR, Barnhart TE, Cai W. ImmunoPET and near-infrared fluorescence imaging of CD105 expression using a monoclonal antibody duallabeled with 89Zr and IRDye 800CW. Am J Transl Res. 2012;4:333–346. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hong H, Yang Y, Zhang Y, Engle JW, Barnhart TE, Nickles RJ, Leigh BR, Cai W. Positron emission tomography imaging of CD105 expression during tumor angiogenesis. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2011;38:1335–1343. doi: 10.1007/s00259-011-1765-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Alauddin MM. Positron emission tomography (PET) imaging with 18F-based radiotracers. Am J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2012;2:55–76. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nolting DD, Nickels ML, Guo N, Pham W. Molecular imaging probe development: a chemistry perspective. Am J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2012;2:273–306. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ray P, Tsien R, Gambhir SS. Construction and validation of improved triple fusion reporter gene vectors for molecular imaging of living subjects. Cancer Res. 2007;67:3085–3093. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-2402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.James ML, Gambhir SS. A molecular imaging primer: modalities, imaging agents, and applications. Physiol Rev. 2012;92:897–965. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00049.2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Balyasnikova S, Lofgren J, de Nijs R, Zamogilnaya Y, Hojgaard L, Fischer BM. PET/MR in oncology: an introduction with focus on MR and future perspectives for hybrid imaging. Am J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2012;2:458–474. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Temma T, Saji H. Radiolabelled probes for imaging of atherosclerotic plaques. Am J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2012;2:432–447. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zeman MN, Scott PJ. Current imaging strategies in rheumatoid arthritis. Am J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2012;2:174–220. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hong H, Yang Y, Zhang Y, Cai W. Non-invasive imaging of human embryonic stem cells. Curr Pharm Biotechnol. 2010;11:685–692. doi: 10.2174/138920110792246500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hong H, Yang Y, Zhang Y, Cai W. Non-invasive cell tracking in cancer and cancer therapy. Curr Top Med Chem. 2010;10:1237–1248. doi: 10.2174/156802610791384234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cai W, Zhang Y, Kamp TJ. Imaging of induced pluripotent stem cells: from cellular reprogramming to transplantation. Am J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2011;1:18–28. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]