Abstract

Objective

To determine the incidence, clinical and demographic correlates, and relationship to treatment outcome of self-reported premenstrual exacerbation of depressive symptoms in premenopausal women with major depressive disorder who are receiving antidepressant medication.

Method

This post-hoc analysis used clinical trial data from treatment-seeking, premenopausal, adult female outpatients with major depression who were not using hormonal contraceptives. For this report, citalopram was used as the first treatment step. We also used data from the second step in which one of three new medications were used (bupropion-SR [sustained release], venlafaxine-XR [extended release], or sertraline). Treatment-blinded assessors obtained baseline treatment outcomes data. We hypothesized that those with reported premenstrual depressive symptom exacerbation would have more general medical conditions, longer index depressive episodes, lower response or remission rates, and shorter times-to-relapse with citalopram, and that they would have a better outcome with sertraline than with bupropion-SR.

Results

At baseline, 66% (n=545/821) of women reported premenstrual exacerbation. They had more general medical conditions, more anxious features, longer index episodes, and shorter times-to-relapse (41.3 to 47.1 weeks, respectively). Response and remission rates to citalopram, however, were unrelated to reported premenstrual exacerbation. Reported premenstrual exacerbation was also unrelated to differential benefit with sertraline and bupropion-SR.

Conclusions

Self-reported premenstrual exacerbation has moderate clinical utility in the management of depressed patients, although it is not predictive of overall treatment response. Factors that contribute to a more chronic or relapsing course may also play a role in premenstrual worsening of major depressive disorder (MDD).

Introduction

Major depressive disorder (MDD) affects nearly 15 million adults in the United States each year, approximately two-thirds of whom are women.1 Many women with depression experience premenstrual exacerbation of depressive symptoms (PME), defined as a worsening of the symptoms of an ongoing depressive disorder during the week prior to menses.2–5 Even when antidepressant treatment is effective, some women with PME experience premenstrual breakthrough symptoms.3,6–8 In addition, studies have found the presence of PME to be associated with longer duration of depressive episodes,2 deterioration in functioning,4 and increased risk of both acute worsening of episodes and non-response to antidepressant treatment.9

Although research has yet to understand the underlying mechanisms of PME and premenstrual dysphoric disorder (PMDD) and whether there is any overlap between the two disorders, there is debate that PME may be the manifestation of two concurrent disorders: PMDD and simultaneous MDD.5,10 As such, some speculate that treatments that have shown to be effective for PMDD may also be effective in controlling the PME symptoms in women with MDD.

PME appears to be quite common in women with depression, with recent studies reporting rates ranging from 50%3 to 64%.2 Despite this high frequency, there is a scarcity of scientific information for this population. We previously examined this issue in a preliminary report2 that studied the first 1500 participants enrolled into the Sequenced Treatment Alternatives to Relieve Depression (STAR*D) study (www.star-d.org). Results from this sample indicated that a majority of premenopausal women with MDD endorsed PME, and women with reported PME appeared to experience a longer duration of the current depressive episode, as well as greater general medical comorbidity.2

The present study was undertaken to replicate2 and extend our preliminary findings using data from the full sample of the completed STAR*D trial. A single, clinically simple self-report PME question was used to explore the clinical value of self-reported PME at pretreatment for MDD and whether it could be useful in guiding medication treatment decisions.

To this end, we examined the rates and clinical and demographic correlates of reported PME and investigated whether reported PME was related to treatment outcome in the STAR*D study. Based on our prior work, we expected most premenopausal women to endorse PME2 and for these women to have higher rates of general medical conditions2 and to have a worse course of illness prior to seeking treatment for the index episode (i.e., more likely to have had at least one prior episode, greater number of months in the index episode, and/or more likely to have been in the index episode for ≥24 months)2 as compared with women who did not endorse PME. We also improved upon our prior work by including validated composite scores to measure anxious,11 atypical,12 and melancholic13 features of depression in women with reported PME, which has not been fully explored previously. With respect to treatment outcomes, we hypothesized that women who reported PME would have lower response and/or remission rates to first step citalopram treatment and a shorter time to relapse compared to those without reported PME.14 Further, we hypothesized that at second step treatment, an equal or greater proportion of women with reported PME would respond to a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) as compared to women without reported PME, and a lesser proportion of women with reported PME would respond to bupropion-sustained release (bupropion-SR), given that SSRIs have been shown to be effective in treating premenstrual dysphoric disorder (PMDD)15,16 and bupropion-SR has been shown to be ineffective for PMDD.17

Materials and Methods

Study overview

Data for this secondary analysis were drawn from the STAR*D study, the rationale, design, and methods of which have been described in detail elsewhere.18–20 In brief, STAR*D was a prospective, multisite, randomized clinical trial that examined which of several treatment options are most effective for depressed patients who experience an unsatisfactory response to initial treatment with the SSRI citalopram. The study enrolled patients with nonpsychotic MDD from 18 primary care and 23 psychiatric outpatient clinics across the United States. Clinical research coordinators at each site were responsible for enrolling participants, assisting clinicians and participants in collecting clinical data, and implementing the study protocol. Research outcome assessors blinded to treatment collected primary outcome data via telephone interview.

Participants

STAR*D enrolled participants from July 2001 through April 2004 with the goal of recruiting 4000 participants. Eligible participants were treatment-seeking adult outpatients aged 18–75 years who met the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, fourth edition (DSM-IV) criteria for single episode or recurrent nonpsychotic MDD, as determined by the treating clinician and confirmed using a DSM-IV checklist. To enroll, patients were required to have at least moderately severe depression, defined as a baseline 17-item Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression (HRSD17)21 score ≥14. Exclusion criteria included a lifetime history of bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder, or psychosis; a current diagnosis of anorexia, bulimia, or obsessive-compulsive disorder; and the need for immediate hospitalization or day treatment for substance use or psychiatric disorders. Patients who had a prior non-response with—or were clearly intolerant to—an adequate trial of one or more of the study medications during the current episode were excluded, as were women who were pregnant or breastfeeding.

The STAR*D protocol was developed in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. All procedures were approved and monitored by the National Coordinating Center (University Of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas, TX), the Data Coordinating Center (University of Pittsburgh Epidemiology Data Center, Pittsburgh, PA), and institutional review boards at the 14 regional centers, the clinical sites, and the Data Safety Monitoring Board of the National Institute of Mental Health (Bethesda, MD). After a complete description of the study was provided to participants, written informed consent was obtained.

Selection of sample for PME analyses

STAR*D participants were included in the PME analyses if they were female, under 40 years of age, and were not using hormonal contraceptives. The presence of reported PME was determined based on endorsement of the following clinical interview question: “In the course of the current MDE [major depressive episode], does the patient regularly experience worsening of depressive symptoms 5 to 10 days prior to menses?”

Treatment protocol

A standard study protocol was used at all sites (see Rush et al.19 for a detailed description) wherein all participants were treated with citalopram for 12–14 weeks (level 1 of the trial). Those who reached remission after the initial treatment were then entered into naturalistic follow-up. Participants who did not experience remission of depressive symptoms at level 1 were given the option of continuing to level 2. Those who continued to level 2 were presented the options of either augmenting citalopram with bupropion-SR, buspirone, or cognitive therapy; or discontinuing citalopram and switching to bupropion-SR, venlafaxine-extended release (venlafaxine-XR), sertraline, or cognitive therapy. After the participant and clinician determined which options would be acceptable, beneficial, and medically safe, the participant was randomized to one of the acceptable treatment options.

Uniform random number generation (via an interactive voice response [IVR] system accessed by clinical research coordinators) was used to randomize participants among the treatment options, with an equal chance of receiving any option. Randomization was blocked with the block size equal to the number of treatment options within the preferred strata.

The protocol recommended that medication treatment visits for all treatment levels be conducted at weeks 0, 2, 4, 6, 9, and 12; however, the visit schedule was flexible and extra visits could be held if clinically indicated. The protocol required that cognitive therapy visits be scheduled twice per week for weeks 1–4, then once per week for the remaining 8 weeks.

At the first step (level 1), citalopram was started at 20 mg per day and gradually raised to a maximum dose of 60 mg per day.

For level 2 switch options, dose recommendations for the switch to bupropion-SR began at 150 mg/day and increased to 200 mg/day after one week, 300 mg/day at week 4 and 400 mg/day at week 6. Switch to sertraline began at 50 mg/day for one week and increased to 100 mg/day at week 2, 150 mg/day at week 4 and 200 mg/day at week 9. Switch to venlafaxine-XR began at 37.5 mg/day and increased to 150 mg/day after one week, 225 mg/day at week 4, 300 mg/day at week 6 and 375 mg/day at week 9.

For level 2 augmentation options, bupropion-SR augmentation began at 200 mg/day and was increased to 300 mg/day at week 4 and 400 mg/day at week 6. Buspirone augmentation began at 15 mg/day and was increased to 30 mg/day after one week, 45 mg/day at week 4 and 60 mg/day at week 6.

All medication dosing recommendations were flexible based on clinical judgment informed by the Frequency, Intensity, and Burden of Side Effects Rating (FIBSER)22 and the 16-item Quick Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology: Clinician-Rated (QIDS-C16).23–25 A web-based medication monitoring system,26 use of a clinical research coordinator at each site, and didactic training represented intensive efforts to provide appropriate, vigorous dosing when inadequate symptom reduction occurred in the context of acceptable side effects.

Baseline sociodemographic and clinical measures

At baseline, trained clinical research coordinators at each site collected sociodemographic information and clinical characteristics (e.g., age at first episode, history of suicide attempt, family history of psychiatric disorder) using a standardized intake interview. Concurrent psychiatric diagnoses were assessed using the Psychiatric Diagnostic Screening Questionnaire (PDSQ)27,28 and comorbid general medical conditions were assessed using the Cumulative Illness Rating Scale (CIRS).29 The HRSD17, the QIDS-C16 and QIDS Self-Report (QIDS-SR16)23–25 were used to assess severity of depressive symptoms. Presence of anxious,11 atypical,12 and melancholic13 features were determined based on responses to the HRSD17 and the 30-item Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology: Clinician-Rated (IDS-C30).24 Perceived physical functioning and mental health functioning were evaluated using the 12-item Short-Form Health Survey (SF-12),30 the 16-item Quality of Life Enjoyment and Satisfaction Questionnaire (Q-LES-Q),31 and the Work and Social Adjustment Scale (WSAS).32

Level 1 treatment measures

The QIDS-C16 and QIDS-SR16 were administered at all clinical visits along with a standardized record form that included the FIBSER. Additional treatment measures included presence of serious adverse events, number of weeks in treatment, number of post-baseline visits, maximum citalopram dose, final citalopram dose, number of weeks on the final citalopram dose, and whether the participant discontinued the trial due to citalopram intolerance.

Treatment outcome measures

Treatment outcome variables were the changes in HRSD17 and QIDS-SR16 scores from baseline to endpoint. For this report, response was defined as ≥50% reduction in QIDS-SR16 total score from baseline to final assessment. Remission (primary outcome) was defined as a final QIDS-SR16 score of ≤5, equivalent to a final HRSD17 score of ≤7. Relapse was defined when the QIDS-SR16 score obtained from the IVR during the naturalistic follow-up phase was ≥11, which corresponds to an HRSD17 score ≥14.23 STAR*D remission and relapse threshold scores were established using item response theory (IRT) analysis, described in detail elsewhere.18,23,24 Outcome scores were collected by research outcome assessors who were blinded to treatment, via telephone interview at study completion.

Statistical analyses

Group differences in baseline characteristics, course of treatment, and outcome measures were examined using Student's t-tests and Kruskal-Wallis tests for continuous variables, and chi-squared tests for categorical variables. Logistic regression was used to compare the two groups on binary treatment outcome variables. Kaplan-Meier survival analysis was used to examine differences in time-to-relapse for women in level 1 of treatment (n=200) by the presence or absence of reported PME. A series of binary logistic regressions were computed to determine whether reported PME had a moderating effect on remission status among women who switched to a different medication at level 2. Main effects were included for PME, treatment, and the two-way interaction between PME and treatment. Separate odds ratios were calculated for switch to bupropion-SR, sertraline, or venlafaxine-XR. Statistical significance was set at p<0.05 for all analyses. No adjustments were made for multiple comparisons, so results must be interpreted accordingly.

Results

Baseline sociodemographic and clinical characteristics

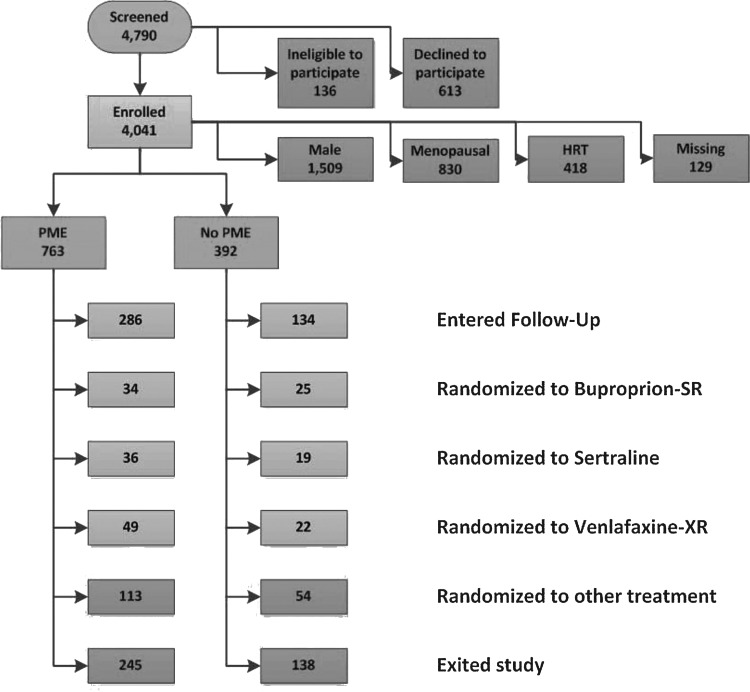

STAR*D recruited 4041 participants across all study sites (Fig. 1). Of this group, 2876 constituted the analyzable sample (HRSD17 score ≥14 and completion of at least one post-baseline visit). Of these, 821 were premenopausal depressed women who were not using hormonal contraceptives. Of this evaluable sample, approximately two-thirds endorsed PME (n=545, 66.3%) and one-third did not (n=276, 33.6%). This is consistent with the hypothesis that most women would report PME.

FIG. 1.

Flow of participants through the study.

In the study, 72.7% were white, 62.6% were employed, and 41.7% were married/cohabiting. Women with reported PME were slightly older than those without reported PME, but there were no significant between-group differences in race, ethnicity, education, employment status, marital status, or medical insurance (Table 1).

Table 1.

Baseline Sociodemographic and Clinical Characteristics Measures by Self-Reported Premenstrual Exacerbation

| |

|

|

PME |

Analyses |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Characteristic |

All (N=821) |

Yes (N=545) |

No (N=276) |

Test statistic |

p value |

|||

| |

n |

% |

n |

% |

n |

% |

|

|

| Sociodemographic characteristics | ||||||||

| Race | chi-squared (2)=1.09 | 0.581 | ||||||

| White | 596 | 72.7 | 392 | 71.9 | 204 | 74.2 | ||

| Black | 156 | 19.0 | 104 | 19.1 | 52 | 18.9 | ||

| Other | 68 | 8.3 | 49 | 9.0 | 19 | 6.9 | ||

| Hispanic | 134 | 16.3 | 81 | 14.9 | 53 | 19.2 | chi-squared (1)=2.53 | 0.112 |

| Employment status | (p)=0.01 | 0.533 | ||||||

| Employed | 513 | 62.6 | 344 | 63.2 | 169 | 61.2 | ||

| Unemployed | 304 | 37.1 | 197 | 36.2 | 107 | 38.8 | ||

| Retired | 3 | 0.4 | 3 | 0.6 | 0 | 0.0 | ||

| Medical insurance | chi-squared (2)=1.04 | 0.594 | ||||||

| Any private | 392 | 49.6 | 263 | 49.9 | 129 | 49.0 | ||

| Public only | 118 | 14.9 | 74 | 14.0 | 44 | 16.7 | ||

| None | 280 | 35.4 | 190 | 36.1 | 90 | 34.2 | ||

| Marital status | chi-squared (3)=2.1 | 0.553 | ||||||

| Never married | 270 | 32.9 | 172 | 31.6 | 98 | 35.5 | ||

| Married/cohabiting | 342 | 41.7 | 227 | 41.7 | 115 | 41.7 | ||

| Divorced/separated | 201 | 24.5 | 140 | 25.7 | 61 | 22.1 | ||

| Widowed | 8 | 1.0 | 6 | 1.1 | 2 | 0.7 | ||

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 34.2 | 8.8 | 34.6 | 8.6 | 33.3 | 9.1 | t(819)=2.01 | 0.045 |

| Education (years) | 13.6 | 2.97 | 13.6 | 3.05 | 13.6 | 2.83 | t(819)=0.22 | 0.828 |

| Monthly household income | 2354 | 2813 | 2447 | 2936 | 2167 | 2540 | H(1)=3.11 | 0.078 |

| Clinical characteristics | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | n | % | |||

| Age at first episode<18 | 385 | 47.6 | 263 | 48.9 | 122 | 45.0 | chi-squared (1)=1.08 | 0.299 |

| At least one prior episode | 585 | 77.2 | 405 | 80.0 | 180 | 71.4 | chi-squared (1)=7.08 | 0.008 |

| Ever attempted suicide | 201 | 24.5 | 131 | 24.0 | 70 | 25.4 | chi-squared (1)=0.17 | 0.677 |

| Family history of | ||||||||

| Alcohol abuse | 355 | 43.5 | 249 | 45.8 | 106 | 38.8 | chi-squared (1)=3.57 | 0.059 |

| Bipolar disorder | 88 | 10.8 | 62 | 11.4 | 26 | 9.6 | chi-squared (1)=0.64 | 0.425 |

| Depression | 502 | 61.5 | 349 | 64.2 | 153 | 56.3 | chi-squared (1)=4.79 | 0.029 |

| Any mood disorder | 522 | 64.0 | 361 | 66.4 | 161 | 59.2 | chi-squared (1)=4.04 | 0.044 |

| Substance abuse | 400 | 49.0 | 274 | 50.4 | 126 | 46.2 | chi-squared (1)=1.29 | 0.256 |

| Drug abuse | 201 | 24.6 | 137 | 25.2 | 64 | 23.4 | chi-squared (1)=0.3 | 0.586 |

| Suicide attempt | 28 | 3.4 | 18 | 3.3 | 10 | 3.7 | chi-squared (1)=0.07 | 0.793 |

| Chronic index* | 165 | 20.3 | 123 | 22.8 | 42 | 15.4 | chi-squared (1)=6.13 | 0.013 |

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age at first episode | 20.8 | 10.4 | 20.6 | 10.4 | 21.3 | 10.3 | H(1)=0.71 | 0.400 |

| Years since first episode | 13.4 | 10.5 | 14.1 | 10.4 | 12.1 | 10.6 | H(1)=9.94 | 0.002 |

| No. episodes | 4.9 | 7.9 | 5.2 | 8.2 | 4.4 | 7.3 | H(1)=7.27 | 0.007 |

| Months since index onset | 22.2 | 50.9 | 23.9 | 54.2 | 18.8 | 43.3 | H(1)=9.49 | 0.002 |

Index episode longer than 24 months.

H, Kruskal-Wallis test statistic; PME, premenstrual exacerbation (reported); SD, standard deviation.

Regarding baseline clinical characteristics (Table 1), women with reported PME endorsed more depressive episodes, more years since their first depressive episode, and more months since onset of the index episode. More women with reported PME had experienced at least one prior depressive episode or had been in the index episode for ≥24 months. This is consistent with our hypothesis that women with reported PME would have worse course of illness prior to seeking treatment for the index episode. Women with reported PME were also more likely to endorse family histories of depression or mood disorders.

Although there were no significant differences between groups in rates of baseline concurrent comorbid psychiatric disorders or number of psychiatric conditions (Table 2), women with reported PME had slightly more general medical conditions and greater general medical burden, as well as more moderate-to-severe general medical conditions. These results regarding general medical conditions are consistent with our hypothesis.

Table 2.

Baseline Comorbidity, Depression, and Function Characteristics by Self-Reported Premenstrual Exacerbation

| |

|

|

PME |

Analyses |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Measure |

All (N=821) |

Yes (N=545) |

No (N=276) |

Test statistic |

p value |

|||

| Comorbidity characteristics | ||||||||

| n | % | n | % | n | % | |||

| PDSQ Agoraphobia | 105 | 12.9 | 75 | 13.8 | 30 | 11.1 | chi-squared (1)=1.19 | 0.275 |

| PDSQ Alcohol abuse | 78 | 9.6 | 56 | 10.3 | 22 | 8.1 | chi-squared (1)=0.99 | 0.320 |

| PDSQ Bulimia | 151 | 18.5 | 102 | 18.8 | 49 | 18.1 | chi-squared (1)=0.05 | 0.817 |

| PDSQ Drug abuse | 60 | 7.4 | 42 | 7.7 | 18 | 6.6 | chi-squared (1)=0.32 | 0.569 |

| PDSQ Generalized anxiety | 240 | 29.5 | 167 | 30.8 | 73 | 26.9 | chi-squared (1)=1.27 | 0.260 |

| PDSQ Hypochondriasis | 45 | 5.5 | 33 | 6.1 | 12 | 4.4 | chi-squared (1)=0.94 | 0.332 |

| PDSQ Obsessive-compulsive | 121 | 14.9 | 89 | 16.4 | 32 | 11.8 | chi-squared (1)=3.00 | 0.083 |

| PDSQ Panic | 111 | 13.6 | 72 | 13.2 | 39 | 14.4 | chi-squared (1)=0.21 | 0.650 |

| PDSQ Posttraumatic stress | 181 | 22.2 | 125 | 23.0 | 56 | 20.7 | chi-squared (1)=0.56 | 0.454 |

| PDSQ Social phobia | 304 | 37.3 | 205 | 37.7 | 99 | 36.5 | chi-squared (1)=0.10 | 0.749 |

| PDSQ Somatoform | 19 | 2.3 | 15 | 2.8 | 4 | 1.5 | chi-squared (1)=1.30 | 0.255 |

| No. psychiatric disorders | chi-squared (4)=3.79 | 0.436 | ||||||

| 0 | 250 | 30.8 | 155 | 28.7 | 95 | 35.2 | ||

| 1 | 196 | 24.2 | 136 | 25.1 | 60 | 22.2 | ||

| 2 | 155 | 19.1 | 105 | 19.4 | 50 | 18.5 | ||

| 3 | 90 | 11.1 | 63 | 11.6 | 27 | 10.0 | ||

| 4+ | 120 | 14.8 | 82 | 15.2 | 38 | 14.1 | ||

| No. moderate to severe GMCs | chi-squared (4)=10.6 | 0.032 | ||||||

| 0 | 474 | 57.7 | 308 | 56.5 | 166 | 60.1 | ||

| 1 | 182 | 22.2 | 114 | 20.9 | 68 | 24.6 | ||

| 2 | 103 | 12.5 | 77 | 14.1 | 26 | 9.4 | ||

| 3 | 36 | 4.4 | 23 | 4.2 | 13 | 4.7 | ||

| 4+ | 26 | 3.2 | 23 | 4.2 | 3 | 1.1 | ||

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CIRS No. problems | 2.58 | 2.02 | 2.75 | 2.07 | 2.22 | 1.88 | H(1)=13.0 | <0.001 |

| CIRS Ratings sum | 3.40 | 2.99 | 3.66 | 3.16 | 2.88 | 2.56 | H(1)=11.0 | 0.001 |

| CIRS Severity index | 1.11 | 0.59 | 1.13 | 0.57 | 1.07 | 0.62 | H(1)=1.75 | 0.185 |

| Depression and function characteristics | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | n | % | |||

| Anxious features | 420 | 51.2 | 295 | 54.1 | 125 | 45.3 | chi-squared (1)=5.73 | 0.017 |

| Atypical features | 179 | 21.8 | 122 | 22.4 | 57 | 20.7 | chi-squared (1)=0.29 | 0.587 |

| Melancholic features | 184 | 22.4 | 123 | 22.6 | 61 | 22.1 | chi-squared (1)=0.02 | 0.879 |

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HRSD17 | 21.8 | 5.24 | 21.8 | 5.21 | 21.8 | 5.32 | t(819)≤0.01 | 0.997 |

| IDS-C30 | 39.2 | 9.59 | 39.3 | 9.54 | 39.0 | 9.70 | t(814)=0.51 | 0.612 |

| QIDS-C16 | 17.2 | 3.20 | 17.0 | 3.23 | 17.5 | 3.11 | t(815)=1.91 | 0.056 |

| QIDS-SR16 | 16.7 | 3.96 | 16.5 | 4.04 | 17.3 | 3.74 | t(816)=2.69 | 0.007 |

| Q-LES-Q | 38.8 | 14.0 | 39.4 | 14.0 | 37.7 | 14.1 | t(774)=1.53 | 0.126 |

| SF-12 Mental | 24.1 | 7.88 | 24.4 | 7.73 | 23.4 | 8.14 | t(774)=1.73 | 0.084 |

| SF-12 Physical | 51.6 | 10.9 | 50.9 | 10.9 | 52.8 | 10.8 | H(1)=6.02 | 0.014 |

| WSAS | 25.3 | 8.6 | 25.0 | 8.56 | 26.0 | 8.65 | t(774)=1.66 | 0.098 |

CIRS, Cumulative illness rating scale; GMC, general medical comorbidity; HRSD17, 17-item Hamilton rating scale for depression; IDS-C30, 30-item Inventory of depressive symptomatology: Clinician-rated; PDSQ, Psychiatric diagnostic screening questionnaire; PME, premenstrual exacerbation (reported); QIDS-C16, 16-item Quick inventory of depressive symptomatology: Clinician-rated, QIDS-SR16, 16-item Quick inventory of depressive symptomatology: Self-rated; Q-LES-Q, Quality of life enjoyment and satisfaction questionnaire; SF-12, Short-form health survey; WSAS Work and social adjustment scale.

There were no significant between-group differences in clinician-rated depressive symptoms (Table 2), but self-reported depressive symptoms were slightly lower for women in the PME group. Women with reported PME were more likely to meet criteria for anxious features and to function more poorly based on the SF-12 physical functioning subscale.

Citalopram treatment and outcomes

Women with reported PME did not significantly differ from those without reported PME regarding number of weeks in citalopram treatment, number of post-baseline visits, maximum citalopram dose, final citalopram dose, number of weeks on last citalopram dose, side-effect frequency, side-effect intensity, side-effect burden, presence of serious adverse events, or exit from the trial due to citalopram intolerance (Table 3).

Table 3.

Treatment Features and Outcomes With Citalopram for Those With and Without Self-Reported Pre-menstrual Exacerbation

| |

|

|

PME |

Analyses |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Measure |

All (n=821) |

Yes (n=545) |

No (n=276) |

Test statistic |

p value |

|||

| Treatment measures | ||||||||

| n | % | n | % | n | % | |||

| Weeks in treatment | ||||||||

| <4 | 107 | 13.0 | 70 | 12.8 | 37 | 13.4 | chi-squared (1)=0.05 | 0.821 |

| <8 | 248 | 30.2 | 155 | 28.4 | 93 | 33.7 | chi-squared (1)=2.4 | 0.121 |

| Maximum FIBSER frequency | chi-squared (3)=0.68 | 0.878 | ||||||

| No side effects | 124 | 15.1 | 79 | 14.5 | 45 | 16.4 | ||

| 10%–25% of the time | 255 | 31.1 | 169 | 31.0 | 86 | 31.3 | ||

| 50%–75% of the time | 271 | 33.0 | 181 | 33.2 | 90 | 32.7 | ||

| 90%–100% of the time | 170 | 20.7 | 116 | 21.3 | 54 | 19.6 | ||

| Maximum FIBSER intensity | chi-squared (3)=2.33 | 0.507 | ||||||

| No side effects | 125 | 15.2 | 79 | 14.5 | 46 | 16.7 | ||

| Minimal/mild | 233 | 28.4 | 156 | 28.6 | 77 | 28.0 | ||

| Moderate/marked | 351 | 42.8 | 230 | 42.2 | 121 | 44.0 | ||

| Severe/intolerable | 111 | 13.5 | 80 | 14.7 | 31 | 11.3 | ||

| Maximum FIBSER burden | chi-squared (3)=4.84 | 0.184 | ||||||

| No impairment | 173 | 21.1 | 103 | 18.9 | 70 | 25.5 | ||

| Minimal/mild | 340 | 41.5 | 234 | 42.9 | 106 | 38.5 | ||

| Moderate/marked | 250 | 30.5 | 170 | 31.2 | 80 | 29.1 | ||

| Severe/intolerable | 57 | 7.0 | 38 | 7.0 | 19 | 6.9 | ||

| Exited due to intolerance* | 131 | 16.0 | 84 | 15.4 | 47 | 17.0 | chi-squared (1)=0.36 | 0.550 |

| At least one SAE | 31 | 3.8 | 19 | 3.5 | 12 | 4.3 | chi-squared (1)=0.37 | 0.541 |

| At least one psychiatric SAE | 19 | 2.3 | 10 | 1.8 | 9 | 3.3 | chi-squared (1)=1.65 | 0.199 |

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Weeks in treatment | 10.0 | 4.41 | 10.2 | 4.41 | 9.7 | 4.4 | H(1)=2.07 | 0.150 |

| No. postbaseline visits | 3.74 | 1.53 | 3.79 | 1.52 | 3.64 | 1.55 | H(1)=1.95 | 0.163 |

| Weeks to first postbaseline visit | 2.38 | 0.93 | 2.36 | 0.82 | 2.43 | 1.13 | H(1)=0.08 | 0.773 |

| Maximum citalopram dose | 43.1 | 15.5 | 43.2 | 15.4 | 42.9 | 15.6 | H(1)=0.01 | 0.913 |

| Last citalopram dose | 41.0 | 16.0 | 41.2 | 15.8 | 40.6 | 16.3 | H(1)=0.17 | 0.684 |

| Weeks on last citalopram dose | 2.80 | 2.89 | 2.94 | 3.01 | 2.51 | 2.61 | H(1)=2.93 | 0.087 |

| Outcome measures | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Unadjusted |

Adjusted** |

||

| n | % | n | % | n | % | Parameter | p value | Parameter | p value | |

| HRSD17 remission | 262 | 31.9 | 174 | 31.9 | 88 | 31.9 | OR(1)=1.002 | 0.9901 | OR(1)=1.059 | 0.762 |

| QIDS-SR16 remission | 292 | 35.6 | 190 | 34.9 | 102 | 37.0 | OR(1)=0.913 | 0.5538 | OR(1)=0.859 | 0.409 |

| QIDS-SR16 response | 405 | 49.5 | 266 | 49.0 | 139 | 50.5 | OR(1)=0.940 | 0.6737 | OR(1)=0.939 | 0.720 |

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Exit QIDS-SR16 score | 8.95 | 6.03 | 8.81 | 5.89 | 9.23 | 6.29 | β(1)=–0.426 | 0.3378 | β(1)=–0.047 | 0.923 |

| % QIDS-SR16 change | −46 | 34.8 | −46 | 35.0 | −47 | 34.6 | β(1)=0.895 | 0.7285 | β(1)=0.848 | 0.774 |

Exited prior to week 4 for any reason or after week 4 citing side effects.

Adjusted for age, years since first episode, number of episodes, family history of depression and mood disorder, months since index onset, number of moderate to severe general medical conditions, baseline QIDS-SR16, anxious features, and 12-item Short-form health survey: Physical.

β, linear regression model parameter estimate; FIBSER Frequency, intensity, and burden of side effects rating scale; OR, odds ratio; SAE serious adverse event.

Approximately half of the women in the sample responded to initial citalopram treatment, as evidenced by a ≥50% reduction in QIDS-SR16 score from baseline to level 1 endpoint. No significant differences were found for women with reported PME compared to those without reported PME regarding QIDS-SR16 severity, treatment response, or remission at the end of level 1 (Table 3). These results remained nonsignificant after adjusting for age, years since first episode, number of depressive episodes, family history of depression or mood disorder, months since onset of index episode, number of moderate-to-severe general medical conditions, baseline QIDS-SR16 score, presence of anxious features, and SF-12 physical functioning score. These results did not support the hypotheses for worse treatment outcome (both response and/or remission) with citalopram in women with reported PME.

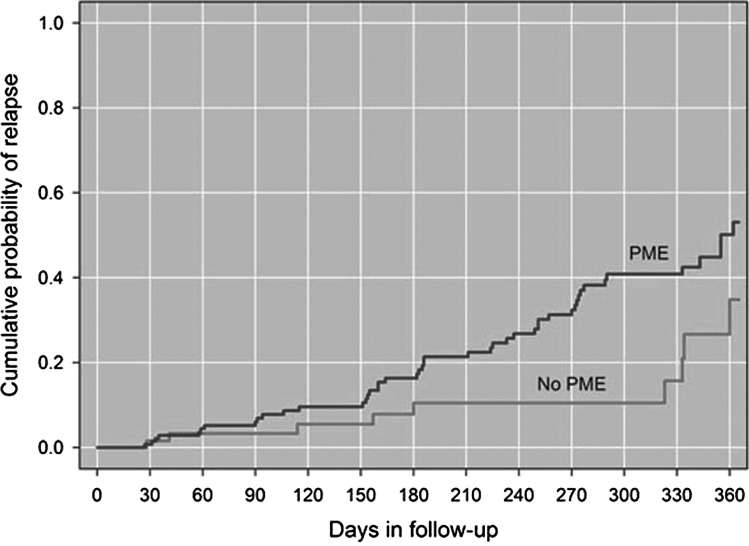

Time-to-relapse in level 1

Examination of stratified survival curves for time-to-relapse for women with reported PME and women without reported PME (Fig. 2) indicated a significantly different time-to-relapse for the two groups. Women with reported PME had an average of 289 days to relapse whereas women without reported PME had an average of 330 days to relapse (Log-rank chi-squared=4.89, p=0.027). These results support the hypothesis that women with reported PME would have a shorter time-to-relapse.

FIG. 2.

Kaplan-Meier curves showing time-to-relapse in level 1 by self-reported premenstrual exacerbation (PME).

Remission status by medication in level 2

Approximately one-fourth (n=185, 22.5%) of the 821 women included in the level 1 analyses switched from citalopram to another medication in level 2. Assignment to medication groups was as follows: bupropion-SR, n=59, 31.9%; sertraline, n=55, 29.7%; and venlafaxine-XR, n=71, 38.4%. Results from logistic regression analyses indicated that the overall moderating effect of reported PME on remission status was not statistically significant (Table 4). These results do not support the hypothesis that an equal or greater proportion of women with reported PME would respond to an SSRI in level 2 and a lesser proportion would respond to bupropion, as compared with women without reported PME.

Table 4.

Remission Rates and Model Statistics by Self-Reported Premenstrual Exacerbation, Overall and Stratified by Treatment

| |

PME |

No PME |

Model statistics |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Treatment | n/N | (%) | n/N | (%) | β | Wald chi-squared | OR | 95% CI | p |

| Overall | 36/118 | (30.5) | 14/66 | (21.2) | 0.4888 | 1.8292 | 1.630 | 0.803–3.311 | 0.1762 |

| Bupropion-SR | 10/34 | (29.4) | 4/25 | (16.0) | 0.7828 | 1.3948 | 2.187 | 0.597–8.019 | 0.2376 |

| Sertraline | 8/35 | (22.9) | 6/19 | (31.6) | −0.4432 | 0.4844 | 0.642 | 0.184–2.237 | 0.4864 |

| Venlafaxine-XR | 18/49 | (36.7) | 4/22 | (18.2) | 0.9605 | 2.3451 | 2.613 | 0.764–8.933 | 0.1257 |

Note: In the columns labeled “n/N”, “n” refers to the number that have remitted and “N” refers to the total number with/without PME for that treatment group.

CI, confidence interval; SR, sustained release; XR extended release.

Discussion

Baseline sociodemographic and clinical characteristics

This study had the largest sample to date for investigating rates, characteristics, correlates and antidepressant treatment outcome relevance of self-reported PME. As hypothesized, we found that a majority (66%) of women endorsed PME and that at baseline, women with reported PME had a worse course of MDD prior to seeking treatment for the index episode, more prior depressive episodes, a greater likelihood of a positive family history of depression or other mood disorder, and more general medical conditions. Women with reported PME were also more likely to have anxious features as part of their depressive episode.

This study's baseline characteristic findings were similar to preliminary findings from a sample of women enrolled during the first half of the STAR*D trial,2 although data from this complete sample did not show as great a difference in length of current episode at baseline for women with reported PME compared to those without reported PME as was found in our preliminary report. This difference may have decreased due to greater variability in a larger sample size.

The association between anxious features of depression and self-report of PME was not evident in the preliminary report, which may be due to different approaches in analyzing the anxiety data. The preliminary report presented a single anxiety item from the IDS-C30, which found similar rates between women with and without reported PME (80% vs. 79%), while our current analyses used a composite score of items from the HRSD17 created specifically to examine anxious depression, as detailed in a previous STAR*D report.33 Research on PME and PMDD has found high comorbidity with anxiety disorders and worsening of anxiety symptoms.34,35 It is possible that the presence of severe premenstrual symptoms, whether PME or PMDD, may signal an increased risk for additional vulnerabilities/comorbid symptoms that increase the complication of illness and treatment.15 Although the relationship and underlying mechanisms of PME and PMDD are not yet fully understood,15 they may have important similarities or differences that, once we understand them, could assist in delivering more effective treatment.

Citalopram treatment and outcomes

We did not find significant differences on any of the course-of-treatment variables, and there were no differences in rates of response or remission with citalopram. This was surprising, as we anticipated that PME might contribute to treatment barriers, such as deterioration of functioning, acute worsening of current episode or non-response to treatment, perhaps due to breakthrough symptoms or other mechanisms yet to be clarified in research to date. The lack of difference in course of treatment, response, and remission may indicate that PME is unrelated to overall initial treatment progress and outcomes for MDD, but may play a detrimental role elsewhere, either in worsening untreated episodes or in later risk for relapse or recurrence. On the other hand, it is possible that adequate treatment of MDD with citalopram also controls the PME symptoms effectively, perhaps indicating similar underlying mechanisms for MDD and PME.

Time-to-relapse in level 1

However, our finding that women with reported PME relapsed an average of 41 days sooner while continuing on citalopram after initially responding to it is a relationship between reported PME and relapse that has not been previously reported. Although speculative, this relationship may indicate increased vulnerabilities related to hormonal fluctuations in women with reported PME, which, when paired with a previous experience of MDD, might contribute to a higher probability of relapse. Perhaps continuing to explore variable antidepressant dosing6,7 or other emerging treatment variations8 will contribute to a greater understanding of the effects of PME on the successful treatment and relapse prevention of depressive episodes.

Remission status by medication in level 2

It was surprising that the presence or absence of reported PME was unrelated to acute outcomes with any second-step medication. Our finding that women with reported PME responded as well to bupropion-SR as those without reported PME is intriguing, as it differs from treatment outcomes for PMDD, where bupropion-SR has been shown to be ineffective.17 If bupropion-SR is effective for self-reported PME but not for PMDD, this suggests that effective treatment of the underlying depression may also take care of the PME. In addition, it could suggest that the features of PME may well differ from PMDD. As this study focused on self-reported PME, it will be important to further examine these potential differences between PME and PMDD in future studies that can track PME symptoms prospectively.

Strengths and limitations

Strengths of this study include the large sample size and generalizability of the results to typical female clinical outpatients with nonpsychotic MDD. This generalizability was enhanced by the recruitment of treatment-seeking participants (no advertising) from a number of primary and psychiatric care sites across the United States, and the use of wide inclusion criteria (including patients with suicidality, substance abuse, general medical conditions, and/or other psychiatric disorders) and minimal exclusion criteria. Although one of the strengths of STAR*D is the large sample size and greater diversity than most randomized controlled trials, most women in this analyses were Caucasian (72.7%) and employed (62.6%), both of which were factors found to increase the chance of remission in level 1 outcomes in a previous STAR*D analyses.36 As such, it is possible that these results may not fully generalize to women from a more diverse racial or ethnic background and/or who are not employed.

The primary limitation of this study was the use of retrospective reporting, as opposed to the gold standard of prospective charting, to identify the presence of PME. Retrospective reporting may have increased the chance of recall bias with regard to participant report of symptoms, and little correspondence has been found between retrospectively self-reported PME and PME actually identified via prospective charting.4,37 As such, this study can only address the clinical relevance of using self-reported PME, which is the general method used in clinical practice to identify the impact of the menstrual cycle on depressive symptoms and treatment. Additionally, although the self-reported PME information was gathered during a clinical interview, a structured, validated assessment method was not used, and the number and severity of worsening symptoms were not recorded. Thus, it was not possible to determine the variability of reported PME symptoms for those endorsing PME or to evaluate the possible effects of variability on our analyses. Finally, a standard operationalized definition of PME has yet to be established across disciplines.

Conclusions

Nearly two-thirds of our premenopausal participants reported having PME. These women had more general medical conditions and longer index depressive episodes, and a shorter time to relapse with citalopram treatment than those without reported PME. In addition, participants with reported PME had more anxious features at baseline than those without reported PME. Response and remission rates did not differ between the two groups defined by reported PME. Our report suggests that self-reported PME does not relate to treatment outcome but is related to sustaining the benefit if response is achieved, and thus may be clinically useful in managing depressed patients. The mechanisms related to the detrimental role of PME are unclear, and further research is needed.

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge the editorial support of Jon Kilner, MS, MA (Pittsburgh, PA). Funding support provided by NIMH under contract N01MH90003 to University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center at Dallas (principal investigator, A. Rush; Madhukar H. Trivedi). Medications for this trial were provided at no cost by Bristol-Myers Squibb, Forest Laboratories, GlaxoSmithKline, King Pharmaceuticals, Organon, Pfizer, and Wyeth. The content of this publication does not necessarily reflect the views or policies of the Department of Health and Human Services, nor does mention of trade names, commercial products, or organizations imply endorsement by the U.S. government. The funders had no role in the design or conduct of the study; data collection, management, analysis or interpretation; decision to publish; or the preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript.

Disclosure Statement

Dr. Kornstein has served as a consultant for Bristol-Myers Squibb, Forest Laboratories, Lilly, Pfizer, Trovis, and Takeda. She has received research support from the National Institute of Mental Health, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Lilly, Euthymics, Forest Laboratories, Boehringer-Ingelheim, Pfizer, Otsuka, and Rexahn. She has received book royalties from Guilford Press.

Dr. A. Rush has received consulting fees from Otsuka Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., University of Michigan, and Brain Resource, Ltd.; speaker fees from Singapore College of Family Physicians; royalties from Guilford Publications and the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center; travel grant from CINP; and research support from the National Institute of Mental Health and Duke-NUS.

Dr. Trivedi has been a consultant for Abbott Laboratories, Inc.; Akzo (Organon Pharmaceuticals, Inc.); AstraZeneca; Bayer; Bristol-Myers Squibb Company; Cephalon, Inc.; Cyberonics, Inc.; Eli Lilly and Company; Fabre-Kramer Pharmaceuticals, Inc.; Forest Pharmaceuticals; GlaxoSmithKline; Janssen Pharmaceutica Products, LP; Johnson and Johnson PRD; Eli Lilly and Company; Meade Johnson; Neuronetics; Parke-Davis Pharmaceuticals, Inc.; Pfizer, Inc.; Pharmacia and Upjohn; Sepracor; Solvay Pharmaceuticals, Inc.; VantagePoint; and Wyeth-Ayerst Laboratories. He has served on speakers bureaus for Abdi Brahim; Akzo (Organon Pharmaceuticals, Inc.); Bristol-Myers Squibb Company; Cephalon, Inc.; Cyberonics, Inc.; Forest Pharmaceuticals; GlaxoSmithKline; Janssen Pharmaceutica Products, LP; Eli Lilly and Company; Pharmacia and Upjohn; Solvay Pharmaceuticals, Inc.; and Wyeth-Ayerst Laboratories. He has also received grant support from Bristol-Myers Squibb Company; Cephalon, Inc.; Corcept Therapeutics, Inc.; Cyberonics, Inc.; Eli Lilly and Company; Forest Pharmaceuticals; GlaxoSmithKline; Janssen Pharmaceutica; Merck; National Institute of Mental Health; National Alliance for Research in Schizophrenia and Depression; Novartis; Pfizer Inc.; Pharmacia and Upjohn; Predix Pharmaceuticals; Solvay Pharmaceuticals, Inc.; and Wyeth-Ayerst Laboratories.

Dr. Wisniewski has been a consultant for Cyberonic Inc. (2005–2009), ImaRx Therapeutics, Inc. (2006), Bristol-Myers Squibb Company (2007–2008), Organon (2007), Case-Western University (2007), Singapore Clinical Research Institute (2009), Dey Pharmaceuticals (2010), Venebio (2010), and Dey (2010).

For all remaining authors, no conflicts of interest exist.

References

- 1.Kessler RC. Chiu WT. Demler O. Merikangas KR. Walters EE. Prevalence, severity, and comorbidity of 12-month DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62:617–627. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kornstein SG. Harvey AT. Rush AJ, et al. Self-reported premenstrual exacerbation of depressive symptoms in patients seeking treatment for major depression. Psychol Med. 2005;35:683–692. doi: 10.1017/s0033291704004106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hartlage A. Brandenburg DL. Kravitz HM. Premenstrual exacerbation of depressive disorders in a community-based sample in the United States. Psychosom Med. 2004;66:698–706. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000138131.92408.b9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kornstein SG. Yonkers KA. Schatzberg AF. Manber R. Burke L. Premenstrual exacerbation of depression. Abstract No. 87C:147. Presented at the 148th Annual Meeting of the American Psychiatric Association; Miami, FL. May, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yonkers KA. White K. Premenstrual exacerbation of depression: One process or two? J Clin Psychiatry. 1992;53:289–292. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Miller MN. Newell CL. Miller BE. Frizzell PG. Kayser RA. Ferslew KE. Variable dosing of sertraline for premenstrual exacerbation of depression: A pilot study. J Women's Health. 2008;17:993–997. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2007.0491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Miller MN. Miller BE. Chinouth R. Coyle BR. Brown GR. Increased premenstrual dosing of nefazodone relieves premenstrual magnification of depression. Depress Anxiety. 2002;15:48–51. doi: 10.1002/da.1086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Joffe H. Petrillo LF. Viguera AC, et al. Treatment of premenstrual worsening of depression with adjunctive oral contraceptive pills: a preliminary report. J Clin Psychiatry. 2007;68:1954–1962. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v68n1218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Harvey AT. Silkey BS. Kornstein SG. Clary CM. Acute worsening of chronic depression during a double-blind, randomized clinical trial of antidepressant efficacy: differences by sex and menopausal status. J Clin Psychiatry. 2007;68:951–958. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v68n0620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Endicott J. Amsterdam J. Eriksson E, et al. Is premenstrual dysphoric disorder a distinct clinical entity? J Womens Health Gend Based Med. 1999 Jun;8:663–679. doi: 10.1089/jwh.1.1999.8.663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fava M. Alpert JE. Carmin CN, et al. Clinical correlates and symptom patterns of anxious depression among patients with major depressive disorder in STAR*D. Psychol Med. 2004;34:1299–1308. doi: 10.1017/s0033291704002612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Novick JS. Stewart JW. Wisniewski SR, et al. (STAR*D investigators). Clinical and demographic features of atypical depression in outpatients with major depression: Preliminary findings from STAR*D. J Clin Psychiatry. 2005;66:1002–1011. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v66n0807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Khan AY. Carrithers J. Preskorn SH, et al. Clinical and demographic factors associated with DSM-IV melancholic depression. Ann Clin Psychiatry. 2006;18:91–98. doi: 10.1080/10401230600614496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dias RS. Lafer B. Russo C, et al. Longitudinal follow-up of bipolar disorder in women with premenstrual exacerbation: findings from STEP-BD. Am J Psychiatry. 2011;168:386–394. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2010.09121816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pinkerton JV. Guico-Pabia CJ. Taylor HS. Menstrual cycle-related exacerbation of disease. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2010;202:221–231. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2009.07.061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rapkin AJ. Winer SA. The pharmacologic management of premenstrual dysphoric disorder. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2008;9:429–445. doi: 10.1517/14656566.9.3.429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pearlstein TB. Stone AB. Lund SA. Scheft H. Zlotnick C. Brown WA. Comparison of fluoxetine, bupropion, and placebo in the treatment of premenstrual dysphoric disorder. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 1997;17:261–266. doi: 10.1097/00004714-199708000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fava M. Rush AJ. Trivedi MH, et al. Background and rationale for the sequenced treatment alternatives to relieve depression (STAR*D) study. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 2003;26:457–494. doi: 10.1016/s0193-953x(02)00107-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rush AJ. Fava M. Wisniewski SR, et al. STAR*D Investigators Group. Sequenced treatment alternatives to relieve depression (STAR*D): rationale and design. Control Clin Trials. 2004;25:119–142. doi: 10.1016/s0197-2456(03)00112-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Trivedi MH. Rush AJ. Wisniewski SR, et al. STAR*D Study Team. Evaluation of Outcomes With Citalopram for Depression Using Measurement-Based Care in STAR*D: Implications for Clinical Practice. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163:28–40. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.163.1.28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hamilton M. A rating scale for depression. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1960;23:56–61. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.23.1.56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wisniewski SR. Rush AJ. Balasubramani GK. Trivedi MH. Nierenberg AA. Self-rated global measure of the frequency, intensity, and burden of side effects. J Psychiatr Pract. 2006;12:71–79. doi: 10.1097/00131746-200603000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rush AJ. Trivedi MH. Ibrahim HM, et al. The 16-item Quick Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology (QIDS), Clinician Rating (QIDS-C), and Self-Report (QIDS-SR): A psychometric evaluation in patients with chronic major depression. Biol Psychiatry. 2003;54:573–583. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(02)01866-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Trivedi MH. Rush AJ. Ibrahim HM, et al. The Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology, Clinician Rating (IDS-C) and Self-Report (IDS-SR), and the Quick Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology, Clinician Rating (QIDS-C) and Self-Report (QIDS-SR) in public sector patients with mood disorders: A psychometric evaluation. Psychol Med. 2004;34:73–82. doi: 10.1017/s0033291703001107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rush AJ. Bernstein IH. Trivedi MH, et al. An evaluation of the Quick Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology and the Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression: A Sequenced Treatment Alternatives to Relieve Depression (STAR*D) trial report. Biol Psychiatry. 2006;59:493–501. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2005.08.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wisniewski SR. Eng H. Meloro L, et al. Web-based communications and management of a multi-center clinical trial: the Sequenced Treatment Alternatives to Relieve Depression (STAR*D) project. Clinical Trials. 2004;1:387–398. doi: 10.1191/1740774504cn035oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zimmerman M. Mattia JI. The reliability and validity of a screening questionnaire for 13 DSM-IV axis I disorders (the Psychiatric Diagnostic Screening Questionnaire) in psychiatric outpatients. J Clin Psychiatry. 1999;60:677–683. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v60n1006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zimmerman M. Mattia JI. A self-report scale to help make psychiatric diagnoses: The Psychiatric Diagnostic Screening Questionnaire. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2001;58:787–794. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.58.8.787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Linn B. Linn M. Gurel L. Cumulative illness rating scale. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1968;16:622–626. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1968.tb02103.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ware J., Jr Kosinski M. Keller SD. A 12-item short-form health survey: construction of scales and preliminary tests of reliability and validity. Med Care. 1996;34:220–233. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199603000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Endicott J. Nee J. Harrison W. Blumenthal R. Quality of Life Enjoyment and Satisfaction Questionnaire (Q-LES-Q): A new measure. Psychopharmacol Bull. 1993;29:321–326. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mundt JC. Marks IM. Shear MK. Greist JH. The work and social adjustment scale: A simple measure of impairment in functioning. Br J Psychiatry. 2002;180:461–464. doi: 10.1192/bjp.180.5.461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fava M. Rush AJ. Alpert JE, et al. Difference in treatment outcome in outpatients with anxious versus nonanxious depression: A STAR*D report. Am J Psych-atry. 2008;165:342–351. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2007.06111868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pearlstein T. Steiner M. Premenstrual dysphoric disorder: Burden of illness and treatment update. J Psychiatry Neuorsci. 2008;33:291–301. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yonkers KA. Anxiety symptoms and anxiety disorders: how are they related to premenstrual disorders? J Clin Psychiatry. 1997;58:62–67. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gaynes BN. Warden D. Trivedi MH, et al. What did STAR*D teach us? Results from a large-scale, practical, clinical trial for patients with depression. Psychiatr Serv. 2009;60:1439–1445. doi: 10.1176/ps.2009.60.11.1439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Harvey AT. Frequency and correlates of perimenstrual exacerbation of depression in clinical trial participants. Poster presented at the 40th Annual Meeting, New Clinical Drug Evaluation Unit (NCDEAU); Boca Raton FL. Jun 2, 2000. May 30. [Google Scholar]