Abstract

Double (bi-allelic) mutations in the gene encoding the CCAAT/enhancer-binding protein-alpha (CEBPA) transcription factor have a favorable prognostic impact in acute myeloid leukemia (AML). Double mutations in CEBPA can be detected using various techniques, but it is a notoriously difficult gene to sequence due to its high GC-content. Here we developed a two-step gene expression classifier for accurate and standardized detection of CEBPA double mutations. The key feature of the two-step classifier is that it explicitly removes cases with low CEBPA expression, thereby excluding CEBPA hypermethylated cases that have similar gene expression profiles as a CEBPA double mutant, which would result in false-positive predictions. In the second step, we have developed a 55 gene signature to identity the true CEBPA double-mutation cases. This two-step classifier was tested on a cohort of 505 unselected AML cases, including 26 CEBPA double mutants, 12 CEBPA single mutants, and seven CEBPA promoter hypermethylated cases, on which its performance was estimated by a double-loop cross-validation protocol. The two-step classifier achieves a sensitivity of 96.2% (95% confidence interval [CI] 81.1 to 99.3) and specificity of 100.0% (95% CI 99.2 to 100.0). There are no false-positive detections. This two-step CEBPA double-mutation classifier has been incorporated on a microarray platform that can simultaneously detect other relevant molecular biomarkers, which allows for a standardized comprehensive diagnostic assay. In conclusion, gene expression profiling provides a reliable method for CEBPA double-mutation detection in patients with AML for clinical use.

Introduction

One of the hallmarks of acute myeloid leukemia (AML) is the accumulation of undifferentiated myeloid cells carrying specific genetic aberrations in the bone marrow (Löwenberg et al., 1999). The CCAAT/enhancer-binding protein-alpha gene (CEBPA) encodes a transcription factor that has been found to play a critical role in granulopoiesis and is mutated in 5%–14% of patients with AML (Pabst et al., 2001; Gombart et al., 2002; Preudhomme et al., 2002; Snaddon et al., 2003; van Waalwijk van Doorn-Khosrovani et al., 2003; Fröhling et al., 2004; Nerlov, 2004; Bienz et al., 2005). Two types of mutations in CEBPA are more frequently found in AML; first, out-of-frame mutations or mutations introducing a stop codon in the N-terminal part of the gene causing premature stops in translation (Zhang et al., 2004), and second, in-frame mutations in the C-terminal basic leucine zipper (bZIP) region of the gene, which appear to impair DNA binding and/or homo- and heterodimerization (Nerlov, 2004). Most AML cases with mutant CEBPA have two mutations, most probably bi-allelic (referred to as CEBPA dm, double mutant, here). The majority of these cases carry a combination of an N-terminal and C-terminal mutation (Nerlov, 2004; Leroy et al., 2005; Pabst and Mueller, 2007). A minority of CEBPA mutant AML cases are mono-allelic, with a single mutation (referred to as CEBPA sm, single mutant) (Nerlov, 2004; Leroy et al., 2005).

The WHO has defined AML with CEBPA mutations (single and double collectively) as a provisional favorable subtype of AML (Swerdlow et al., 2008). AML cases with a CEBPA mutation are predominantly found among the cytogenetically intermediate risk group, mainly those with normal karyotypes (Grimwade et al., 1998). However, AMLs carrying CEBPA double mutations rather than CEBPA single mutations represent a distinct prognostically favorable group of AML cases, and therefore, CEBPA double mutants provide a clinically useful marker for risk stratification of the leukemia (Pabst et al., 2009; Renneville et al., 2009; Wouters et al., 2009; Green et al., 2010; Taskesen et al., 2011). Finally, AML cases have been identified that are CEBPA wt, yet are hypermethylated (Figueroa et al., 2009). Not surprisingly, these AMLs display gene expression patterns that are very similar to those of CEBPA double mutants because a shared set of downstream transcripts are low either due to the bi-allelic mutations or the hypermethylated promoter status of CEBPA (Figueroa et al., 2009; Taskesen et al., 2011). However, CEBPA double-mutation AMLs and CEBPA hypermethylated AMLs are different as regard to the gene expression levels of CEBPA itself, which are generally higher in the double-mutant AML subtypes, but low to absent in the hypermethylated subtype.

Classification of CEBPA dm cases has been previously demonstrated using gene expression profiling (Wouters et al., 2009); however, misclassified cases were the CEBPA hypermethylated AMLs (Figueroa et al., 2009; Taskesen et al., 2011). Herein we have developed a two-step classifier, which explicitly distinguishes the CEBPA double mutants from the CEBPA hypermethylated. Accuracy of this two-step classifier was established by means of a double-loop cross validation on a cohort of 505 primary AML cases. The two-step classifier was then incorporated on a custom chip, along with detection capabilities for AML1-ETO, CBFB-MYH11, PML-RARA, other mutations such as NPM1 (Van Vliet et al., Submitted), as well as overexpression of prognostic genes EVI1 and BAALC (Brand et al., in preparation). Thus, this gene expression assay provides a standardized test for multiple molecular biomarkers relevant for AML at the time of diagnosis.

Materials and Methods

Custom in vitro diagnostic gene expression array

A customized Affymetrix (Santa Clara, CA) GeneChip microarray was designed (AMLprofiler™). This custom chip includes a subset of the probe sets present on the Affymetrix HG-U133 Plus2 platform and a subset of probes designed for specific purposes. Its resulting .CEL file is automatically routed through proprietary software that reports 0 or 1 for CEBPA wt and CEBPA dm, respectively.

Datasets

We employed the blood or bone marrow specimens from 505 AML patients, who had been enrolled in the Dutch–Belgian Hematology–Oncology Cooperative group protocols -04, -04A, -29, and -42 (HOVON-SAKK, the Erasmus University Medical Center, Rotterdam), (Valk et al., 2004; Wouters et al., 2009). The 505 cases employed here are a subset from the 524 cases (Wouters et al., 2009) for which the hybridization cocktail was available. The 505 set contains all 26 CEBPA dm and 12 CEBPA sm cases from the Wouters et al. (2009) cohort (Table 1). Sample processing and quality control were performed as previously described (Wouters et al., 2009). Bi-allelic mutant, single mutant, and wild-type CEBPA annotations were confirmed in all cases by the entire CEBPA coding region investigation by denaturing high-performance liquid chromatography (dHPLC), analysis of selected regions by agarose gel analysis (van Waalwijk van Doorn-Khosrovani et al., 2003), and/or nucleotide sequencing (Wouters et al., 2009). CEBPA promoter hypermethylation was determined using the HELP assay (HpaII tiny fragment enrichment by ligation-mediated PCR), as previously described (Valk et al., 2004). Table 1 shows an overview of the CEBPA mutation status of all AML cases in the cohort.

Table 1.

Overview of Cases in the Cohort, and Distribution of CEBPA Mutations

| |

|

Training cohort |

Above step 1 threshold |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CEBPA status | Label | n | % | n | % |

| CEBPA WT | Neg | 458 | 90.7% | 48 | 60.8% |

| CEBPA Hypermethylated | Neg | 9 | 1.8% | 0 | 0.0% |

| CEBPA single mutant | Neg | 12 | 2.4% | 5 | 6.3% |

| CEBPA double mutant | Pos | 26 | 5.1% | 26 | 32.9% |

| Total | 505 | 100.0% | 79 | 100.0% | |

Hybridization cocktails were obtained for all cases (Verhaak et al., 2009), and were hybridized onto the AMLprofiler platform. All .CEL files were preprocessed using the MAS5 algorithm (scaling to 1500), and probe set intensities below 30 truncated to 30. Subsequently, geometric mean centering was applied per probe set relative to a subset of 244 AML cases.

AML profiler CEL files are available at the Gene Expression Omnibus (National Center for Biotechnology Information) under accession number GSE42194.

All patients provided written informed consent in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Double-loop cross validation

To build diagnostic classifiers from high throughput data, we used the double-loop cross-validation framework (Wessels et al., 2005). We adopted this methodology combined with forward filtering as the feature selector, the signal to noise ratio as a criterion to evaluate the individual genes, and ClaNC (Dabney, 2005) a simple classifier that is known to perform well on this type of data. The double-loop cross validation was executed with 100 repeats of 26-fold cross validation in the outer (validation) loop, and 10-fold cross validation in the inner loop. Learning curves were constructed for up to 100 genes, using the average of the sensitivity and specificity as criterion (reported as percentages, 50% is random classification, 100% is perfect classification) to be optimized. At all points, data splits were stratified with respect to the class prior probabilities. To optimize a classifier toward less FN or less FP cases, the prior probabilities were adjusted, such that the classifier boundary gets shifted.

Results

Development of a classifier for CEBPA dm

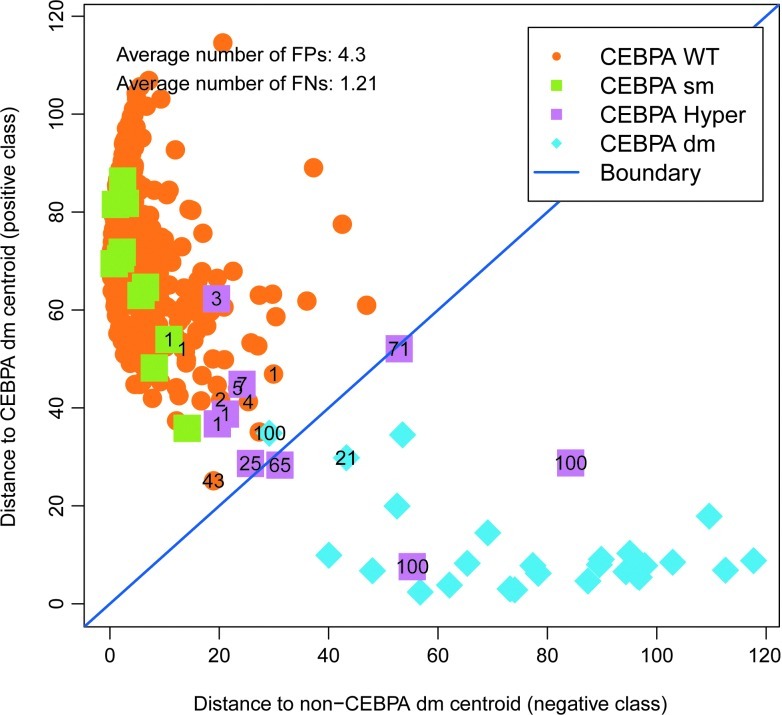

We set out to develop a classifier for detecting CEBPA dm AML cases in a cohort of 505 patients with AML (Table 1). For this, we consider the CEBPA dm as the positive group, and the remainder as negative (CEBPA wt, sm, or hypermethylated). This provides a six gene classifier with high performance, as shown in Figure 1 and Table 2. The misclassified cases are predominantly the hypermethylated cases (Fig. 1), which are consistent with their biological background, as the downstream gene expression profiles from a nonfunctional CEBPA protein due to the bi-allelic gene mutations may be equivalent to the absence of the protein due to the hypermethylated gene status. Although this classifier has a high accuracy, from a clinical utility point of view, false-positive cases are undesirable as they might be at risk of undertreatment given the favorable prognosis of CEBPA double mutants. Therefore, we investigated methods to exclude the hypermethylated cases before the application of a classifier.

FIG. 1.

CEBPA hypermethylated cases are often FP in CEBPA double-mutant classifiers. The scatter plot showing the output of a one-step classifier trained on the 505 cases as determined by the double-loop cross-validation procedure. Numbers indicate how often a case was misclassified in the 100 repeats (samples always correctly classified do not have a number printed). Color images available online at www.liebertpub.com/gtmb

Table 2.

Double-loop Cross-Validation Performances of the Classifiers for Predicting CEBPA Double Mutations

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

95% CI |

|

95% CI |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Classifier | n | TP | FN | TN | FP | Sens | LL | UL | Spec | LL | UL |

| Overall classifier | 505 | 24.79 | 1.21 | 474.70 | 4.30 | 95.3 | 80.0 | 99.1 | 99.1 | 97.8 | 99.6 |

| Two-Step classifier | 505 | 25.00 | 1.00 | 479.00 | 0.00 | 96.2 | 81.1 | 99.3 | 100.0 | 99.2 | 100.0 |

Sens, sensitivity; spec, specificity; CI, confidence interval; LL, lower limit; UL, upper limit.

Development of a two-step classifier for CEBPA dm

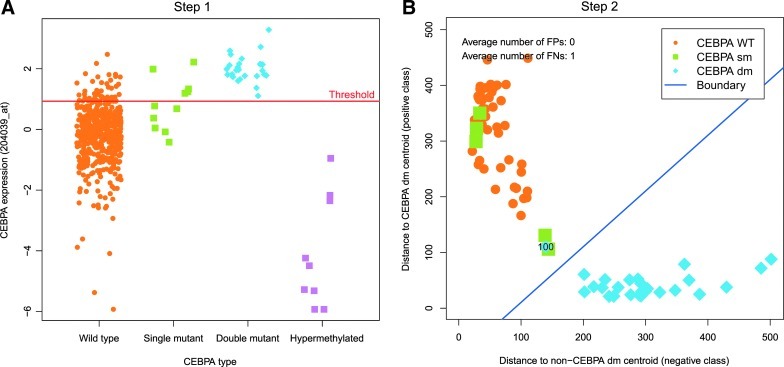

Since AML cases with hypermethylated CEBPA show reduced CEBPA gene expression levels, we propose a two-step classifier. In step 1, the CEBPA expression level is assessed in comparison with a threshold. In step 2, only the selected cases exceeding that threshold will subsequently be input into the classifier (Fig. 2).

FIG. 2.

Overview of the two-step classifier for predicting CEBPA dm.

The step 1 threshold was developed as follows. The expression levels for the different CEBPA mutation groups were compared (Fig. 3A). As expected, the hypermethylated CEBPA cases all have notably low CEBPA expression values. The CEBPA wt cases show a wide range of variable CEBPA expression levels, whereas the CEBPA sm cases have slightly elevated CEBPA expression. However, the CEBPA dm cases all share high CEBPA expression levels. The aim of the step 1 classifier is to classify all hypermethylated cases below the threshold and all CEBPA dm cases above the threshold. The threshold is determined by the intersection of the two fitted normal distributions on the group of CEBPA dm cases and CEBPA hypermethylated cases. At that point, the groups have an equal chance of correct classification (i.e., where the overall chance of misclassification is minimal), indicated by the red line in Figure 3A. A total of 79 cases exceeds this threshold, including all 26 CEBPA dm cases, 5 CEBPA sm cases, and 48 CEBPA wt cases (see Table 1).

FIG. 3.

(A) Step 1: Scatter plot indicating the distribution of the CEBPA expression level (y-axis) for all 505 cases split across the four groups of CEBPA status (x-axis). The red line indicates the threshold chosen for the first classifier. (B) Step 2: Scatter plot showing the classifier trained on the 79 cases that are above the threshold in (A), as determined by the double-loop cross-validation procedure. Numbers indicate how often a case was misclassified in the 100 repeats (samples always correctly classified do not have a number printed). Color images available online at www.liebertpub.com/gtmb

The step 2 classifier was developed using the 79 cases that exceed the threshold of the first step of the classifier. On these 79 cases, we trained a classifier without FPs and minimal FNs. This results in a 55-gene classifier with 0 FP and 1 FN (sensitivity 96.2%; specificity 100.0%; Fig. 3B). This classifier has a better sensitivity and specificity compared with the classifier trained on all 505 cases (see Table 2). The 55 probe sets used in the classifier are provided in Table 3.

Table 3.

55 Probe Sets Used in the Classifier

| AffyID | Gene name | Ensembl gene | AffyID | Gene name | Ensembl gene |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 223095_at | MARVELD1 | ENSG00000155254 | 204069_at | MEIS1 | ENSG00000143995 |

| 200765_x_at | CTNNA1 | ENSG00000044115 | 1559477_s_at | MEIS1 | ENSG00000143995 |

| 200764_s_at | CTNNA1 | ENSG00000044115 | 213844_at | HOXA5 | ENSG00000106004 |

| 1555630_a_at | RAB34 | ENSG00000109113 | 235521_at | HOXA3 | ENSG00000105997 |

| 232227_at | LOC100505976 | ENSG00000228401 | 205453_at | HOXB2 | ENSG00000173917 |

| 1553183_at | UMODL1 | ENSG00000177398 | 235753_at | HOXA7 | ENSG00000122592 |

| 209191_at | TUBB6 | ENSG00000176014 | 225368_at | HIPK2 | ENSG00000064393 |

| 1556599_s_at | ARPP21 | ENSG00000172995 | 204039_at | CEBPA | ENSG00000184771 |

| 210844_x_at | CTNNA1 | ENSG00000044115 | 206940_s_at | POU4F1 | ENSG00000152192 |

| 206622_at | TRH | ENSG00000170893 | 209686_at | S100B | ENSG00000160307 |

| 222423_at | NDFIP1 | ENSG00000131507 | 204082_at | PBX3 | ENSG00000167081 |

| 202252_at | RAB13 | ENSG00000143545 | 209994_s_at | ABCB4 | ENSG00000005471 |

| 215772_x_at | LOC283398 | ENSG00000172340 | 225841_at | C1orf59 | ENSG00000162639 |

| 217226_s_at | SFXN3 | ENSG00000107819 | 224428_s_at | CDCA7 | ENSG00000144354 |

| 205382_s_at | CFD | ENSG00000197766 | 211682_x_at | UGT2B10 | ENSG00000109181 |

| 217853_at | TNS3 | ENSG00000136205 | 206847_s_at | HOXA7 | ENSG00000122592 |

| 241706_at | CPNE8 | ENSG00000139117 | 228904_at | HOXB3 | ENSG00000120093 |

| 213147_at | HOXA10 | ENSG00000153807 | 216733_s_at | GATM | ENSG00000171766 |

| 209905_at | HOXA9 | ENSG00000078399 | 202746_at | ITM2A | ENSG00000078596 |

| 210762_s_at | DLC1 | ENSG00000164741 | 226065_at | PRICKLE1 | ENSG00000139174 |

| 228365_at | CPNE8 | ENSG00000139117 | 206772_at | PTH2R | ENSG00000144407 |

| 214651_s_at | HOXA9 | ENSG00000078399 | 211341_at | POU4F1 | ENSG00000152192 |

| 216667_at | ECRP/RNASE2 | ENSG00000136315 | 206111_at | RNASE2 | ENSG00000169385 |

| 225116_at | HIPK2 | ENSG00000064393 | 203509_at | SORL1 | ENSG00000137642 |

| 213150_at | HOXA10 | ENSG00000153807 | 206589_at | GFI1 | ENSG00000162676 |

| 224822_at | DLC1 | ENSG00000164741 | 209360_s_at | RUNX1 | ENSG00000159216 |

| 201841_s_at | HSPB1 | ENSG00000106211 | 202718_at | IGFBP2 | ENSG00000115457 |

| 217800_s_at | NDFIP1 | ENSG00000131507 |

Discussion

Given the favorable prognostic value of CEBPA double mutants, accurate detection of CEBPA mutations at the time of AML diagnosis is important. Current methods include dHPLC followed by Sanger sequencing, direct sequencing, melting curves, etc. However, CEBPA is a notoriously difficult gene to sequence due to its high GC content. In addition, due to short sequence reads, most next generation sequencing (NGS) techniques cannot confirm whether two co-occurring mutations inactivate both alleles or reside on the same allele. Alternatively, a gene expression classifier for CEBPA dm in AML has been built previously (Wouters et al., 2009), but not one that explicitly prevented CEBPA promoter hypermethylated AML cases as false-positive CEBPA double mutants (Figueroa et al., 2009; Taskesen et al., 2011).

Given the favorable prognosis of CEBPA double mutants, FP cases might be at risk of undertreatment. CEBPA hypermethylated cases have a gene expression pattern that is overall very similar to CEBPA double-mutant cases (Figueroa et al., 2009; Taskesen et al., 2011), and therefore, they are more likely than others to end up as FP. Therefore, we have built a two-step classifier that first eliminates CEBPA hypermethylated cases based on their low CEBPA expression level, which is the only difference that distinguishes them from CEBPA double-mutant cases. Next, a classifier with unequal prior probability is employed such that there were zero FPs. This two-step classifier provides an accurate method for predicting CEBPA dm status in AML.

Validation of a classifier on an independent cohort is a common way to estimate its performance. However, such gene expression data measured using the custom Affymetrix GeneChip platform is currently unavailable. As an alternative, we employed the double-loop cross-validation procedure, which estimates the classifier's performance using multiple resamplings of the same data (generalization performance, Wessels et al., 2005). Finally, the two-step classifier presented here will also be validated in an ongoing prospective clinical trial.

In conclusion, the two-step classifier provides an accurate means to detect CEBPA dm status. Moreover, the CEBPA dm classifier has been included on the AML profiler Affymetrix platform that also detects the presence of t(8;21), t(15;17), inv(16)/t(16;16), NPM1 mutations, EVI1 overexpression, and BAALC overexpression, in a single standardized test. Together, this enables a more efficient analysis at diagnosis, with a single sample work up that is suitable for clinical use.

Acknowledgments

This research was performed within the framework of CTMM, the Center for Translational Molecular Medicine, project BioCHIP grant 03O-102.

Author Disclosure Statement

M.H.V.V. performed research, design of experiments, data analysis, data interpretation, and manuscript writing. P.B., L.D.Q., J.P.M.B., L.C.M.B., and H.V. performed research. B.L. and P.J.M.V. conceptuated the project, and were involved in research, design of the experiments, data interpretation, and manuscript writing. EHVB performed research, design of experiments, data interpretation, and manuscript writing. M.H.V.V., P.B., L.D.Q., J.P.M.B., L.C.M.B., H.V., B.L., P.J.M.V., and E.H.V.B. have declared ownership interests in Skyline Diagnostics.

References

- Bienz M. Ludwig M. Leibundgut EO, et al. Risk assessment in patients with acute myeloid leukemia and a normal karyotype. Clin Cancer Res. 2005;11:1416–1424. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-1552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dabney AR. Classification of microarrays to nearest centroids. Bioinformatics. 2005;21:4148–4154. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bti681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Figueroa ME. Wouters BJ. Skrabanek L, et al. Genome-wide epigenetic analysis delineates a biologically distinct immature acute leukemia with myeloid/T-lymphoid features. Blood. 2009;113:2795–2804. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-08-172387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fröhling S. Schlenk RF. Stolze I, et al. CEBPA mutations in younger adults with acute myeloid leukemia and normal cytogenetics: prognostic relevance and analysis of cooperating mutations. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:624–633. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.06.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gombart AF. Hofmann W-K. Kawano S, et al. Mutations in the gene encoding the transcription factor CCAAT/enhancer binding protein alpha in myelodysplastic syndromes and acute myeloid leukemias. Blood. 2002;99:1332–1340. doi: 10.1182/blood.v99.4.1332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green CL. Koo KK. Hills RK, et al. Prognostic significance of CEBPA mutations in a large cohort of younger adult patients with acute myeloid leukemia: impact of double CEBPA mutations and the interaction with FLT3 and NPM1 mutations. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:2739–2747. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.26.2501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grimwade D. Walker H. Oliver F, et al. The importance of diagnostic cytogenetics on outcome in AML: analysis of 1,612 patients entered into the MRC AML 10 trial. Blood. 1998;92:2322–2333. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leroy H. Roumier C. Huyghe P, et al. CEBPA point mutations in hematological malignancies. Leukemia. 2005;19:329–334. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2403614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Löwenberg B. Downing JR. Burnett A. Acute myeloid leukemia. N Engl J Med. 1999;341:1051–1062. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199909303411407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nerlov C. C/EBPalpha mutations in acute myeloid leukaemias. Nat Rev Cancer. 2004;4:394–400. doi: 10.1038/nrc1363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pabst T. Mueller BU. Zhang P, et al. Dominant-negative mutations of CEBPA, encoding CCAAT/enhancer binding protein-alpha (C/EBPalpha), in acute myeloid leukemia. Nat Genet. 2001;27:263–270. doi: 10.1038/85820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pabst T. Mueller BU. Transcriptional dysregulation during myeloid transformation in AML. Oncogene. 2007;26:6829–6837. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pabst T. Eyholzer M. Fos J, et al. Heterogeneity within AML with CEBPA mutations; only CEBPA double mutations, but not single CEBPA mutations are associated with favourable prognosis. Br J Cancer. 2009;100:1343–1346. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6604977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preudhomme C. Sagot C. Boissel N, et al. Favorable prognostic significance of CEBPA mutations in patients with de novo acute myeloid leukemia: a study from the Acute Leukemia French Association (ALFA) Blood. 2002;100:2717–2723. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-03-0990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Renneville A. Boissel N. Gachard N, et al. The favorable impact of CEBPA mutations in patients with acute myeloid leukemia is only observed in the absence of associated cytogenetic abnormalities and FLT3 internal duplication. Blood. 2009;113:5090–5093. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-12-194704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snaddon J. Smith ML. Neat M, et al. Mutations of CEBPA in acute myeloid leukemia FAB types M1 and M2. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2003;37:72–78. doi: 10.1002/gcc.10185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swerdlow SH. Campo E. Harris NL, et al. IARC Press; Lyon: 2008. WHO Classification of Tumours of Haematopoietic and Lymphoid Tissues. [Google Scholar]

- Taskesen E. Bullinger L. Corbacioglu A, et al. Prognostic impact, concurrent genetic mutations, and gene expression features of AML with CEBPA mutations in a cohort of 1182 cytogenetically normal AML patients: further evidence for CEBPA double mutant AML as a distinctive disease entity. Blood. 2011;117:2469–2475. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-09-307280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valk PJM. Verhaak RGW. Beijen MA, et al. Prognostically useful gene-expression profiles in acute myeloid leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:1617–1628. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa040465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Waalwijk van Doorn-Khosrovani SB. Erpelinck C. Meijer J, et al. Biallelic mutations in the CEBPA gene and low CEBPA expression levels as prognostic markers in intermediate-risk AML. Hematol J. 2003;4:31–40. doi: 10.1038/sj.thj.6200216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verhaak RGW. Wouters BJ. Erpelinck CAJ, et al. Prediction of molecular subtypes in acute myeloid leukemia based on gene expression profiling. Haematologica. 2009;94:131–134. doi: 10.3324/haematol.13299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wessels LFA. Reinders MJT. Hart AAM, et al. A protocol for building and evaluating predictors of disease state based on microarray data. Bioinformatics. 2005;21:3755–3762. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bti429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wouters BJ. Löwenberg B. Erpelinck-Verschueren CAJ, et al. Double CEBPA mutations, but not single CEBPA mutations, define a subgroup of acute myeloid leukemia with a distinctive gene expression profile that is uniquely associated with a favorable outcome. Blood. 2009;113:3088–3091. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-09-179895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang P. Iwasaki-Arai J. Iwasaki H, et al. Enhancement of hematopoietic stem cell repopulating capacity and self-renewal in the absence of the transcription factor C/EBP alpha. Immunity. 2004;21:853–863. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2004.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]