Abstract

Purpose: This study describes practitioner knowledge and practices related to BRCA testing and management and explores how training may contribute to practice patterns. Methods: A survey was mailed to all BRCA testing providers in Florida listed in a publicly available directory. Descriptive statistics characterized participants and their responses. Results: Of the 87 respondents, most were community-based physicians or nurse practitioners. Regarding BRCA mutations, the majority (96%) recognized paternal inheritance and 61% accurately estimated mutation prevalence. For a 35-year-old unaffected BRCA mutation carrier, the majority followed national management guidelines. However, 65% also recommended breast ultrasonography. Fewer than 40% recognized the need for comprehensive rearrangement testing when BRACAnalysis® was negative in a woman at 30% risk. Finally, fewer than 15% recognized appropriate testing for a BRCA variant of uncertain significance. Responses appeared to be positively impacted by presence and type of cancer genetics training. Conclusions: In our sample of providers who order BRCA testing, knowledge gaps in BRCA prevalence estimates and appropriate screening, testing, and results interpretation were identified. Our data suggest the need to increase regulation and oversight of genetic testing services at a policy level, and are consistent with case reports that reveal liability risks when genetic testing is conducted without adequate knowledge and training.

Introduction

The discovery of the BRCA1 and BRCA2 (BRCA) genes ∼15 years ago enables the identification of individuals at greatly elevated risk for breast and ovarian cancer in the range of 60%–70% and 40%, respectively (Antoniou et al., 2003; Pal et al., 2005; Chen and Parmigiani, 2007). Nevertheless, efficient identification and management of women with BRCA mutations remains challenging. Ensuring adequate knowledge and training among those who order genetic testing and manage patients at high risk for cancer is a key step to meeting this challenge. Prior research suggests that many clinicians in the United States lack sufficient genetics knowledge to provide adequate genetic counseling and testing services (Peterson et al., 2001; Doksum et al., 2003; Wideroff et al., 2005; Domchek and Weber, 2008; Cohen et al., 2009; Geier et al., 2009; Vig et al., 2009). Particularly challenging topics include (1) paternal inheritance of BRCA mutations (Albrecht et al., 2005; Wideroff et al., 2005); (2) interpretation of negative test results in the absence of a documented familial mutation (Cohen et al., 2009; Geier et al., 2009); and (3) recommendations for individuals and families with variants of uncertain significance (VUS) (Domchek and Weber, 2008; Plon et al., 2011).

Given the complexities of delivering high-quality genetic services, several professional organizations endorse involvement of a cancer genetic professional during the genetic testing process (Forum and Medicine, 2007; American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, 2009; Oncology Nursing Society, 2009; Robson et al., 2010; National Comprehensive Cancer Network, 2012; Riley et al., 2012). However, over the last decade, genetic testing has increasingly been ordered and interpreted by community practitioners without involvement of a genetics professional (Keating et al., 2008).

A 2004/2005 national study of practitioners in the U.S. who order BRCA testing concluded that community-based physicians' cancer surveillance recommendations are generally consistent with national guidelines (Keating et al., 2008). However, BRCA knowledge and genetic testing recommendations were not assessed as part of the study. This information is critical to fully assess the incorporation of BRCA testing into practice, especially as BRCA testing is marketed directly to community-based physicians who are increasingly encouraged to order and interpret genetic tests (American College of Obstetrics and Gynecologists, 2009; Geier et al., 2009). Furthermore, limited education not meeting any accreditation guidelines is offered to them (Vadaparampil et al., 2005; Myers et al., 2006), despite the availability of more in depth genetic training programs for healthcare practitioners who are not formally trained in genetics. In fact, higher levels of education and continuing education programs in cancer genetics have been shown to be positively associated with health professionals' knowledge (Peterson et al., 2001; Blazer et al., 2011). However, there remains a lack of information about the extent to which various types of training may influence BRCA-related knowledge and practices, and this information is necessary to promote the adoption of best practices. The objectives of the current study were to (1) assess knowledge and practices related to identifying, testing, and managing individuals at risk for BRCA mutations in a statewide sample of Florida-based providers, and (2) explore whether the type of clinical cancer genetics training influences differences in knowledge and reported practice recommendations.

Materials and Methods

Sample

A total of 452 healthcare practitioners and/or healthcare facilities were listed on the Myriad Genetics (the company that holds the patent to the BRCA genes in the United States) website as providers of BRCA testing services in the state of Florida in September of 2011. Of these, we excluded 36 facilities that did not include a practitioner name; 54 practitioners because they no longer practiced at the location listed based on attempted phone contact; and 4 who were associated with the investigative team. The remaining 358 practitioners from the Myriad list were combined with 28 Florida-based practitioners who study team members had previous contact with and were known to provide BRCA testing services. The final population included 386 Florida practitioners. Utilizing publicly available information, the study team collected demographic information for all practitioners to whom the survey was mailed.

Survey development

The survey was developed using the Competing Demands Model, which proposes that patient, physician, and practice level factors impact a physician's decision to provide a medical service, such as genetic counseling and testing (Jaen et al., 1994). Where possible, items were used from previous surveys of physician practices related to delivery of genetic counseling and testing services for inherited cancer predisposition (Wideroff et al., 2005; Keating et al., 2008). The survey covered four major areas: (1) current cancer susceptibility screening practices; (2) knowledge, clinical opinion, and recommendations; (3) information sources and preferences; and (4) demographic and practice characteristics. Clinical opinion and recommendations were assessed using brief clinical scenarios. Face validity was established through qualitative interviews with five nursing professionals (four nurse practitioners and one nurse) from five different states who have provided genetic counseling and testing for inherited cancer susceptibility in the community setting for a mean of 7 years (range: 5–12 years).

Survey procedures

All 386 Florida-based practitioners were mailed a notification postcard to advise them of the forthcoming survey. Approximately 2 weeks later, survey packets were sent via FedEx mail; these packets included a (1) cover letter, (2) paper survey, and (3) prepaid return envelope. For those who did return the initial survey, an identical survey packet was mailed ∼1 month after the first mailing. A third and final survey packet, identical to the preceding mailings, was sent to all practitioners who had not responded ∼1 month after the second mailing. In addition, a notification postcard was mailed ∼2 weeks before the distribution of the second and third survey packets. Upon receipt of the completed survey, respondents were sent a $25 gift card as a token of appreciation.

Statistical analyses

Frequencies and percentages were calculated to characterize demographics of respondents, decliners, and nonrespondents. To assess for response bias, chi-square tests were performed to determine the equivalence of participants and nonparticipants in terms of gender and profession. Frequencies and percentages for responses to knowledge and clinical recommendation questions were calculated for all respondents as well as subdivided by genetics professionals (defined as certified genetic counselors and board-certified clinical geneticists) and nongenetics professionals. Frequencies and percentages were similarly calculated after further subdividing all nongenetics professionals based on the following reported training in genetics: (1) completion of a formal cancer genetics course with or without training offered by commercial laboratory; (2) completion of training through commercial laboratory; and (3) no training in cancer genetics. Finally, in order to gain insight into how response bias may have influenced the results, frequencies and percentages for nongenetics professionals' responses to knowledge and clinical recommendation questions were calculated after subdividing by (1) professional training (MD versus other practitioners) and (2) gender.

Results

Response rate and sample characteristics

An overview of sampling, response rates, and profession of participants, decliners, and nonrespondents is provided in Figure 1. Of the 386 potential respondents, 11 packets were returned as “undeliverable” and of the remaining 375 respondents, 91 practitioners (24%) returned a survey and 15 (4%) declined participation. Of the 91 respondents, 4 practitioners who reported that they do not provide BRCA testing were removed from the sample.

FIG. 1.

Sampling and respondents.

Demographic variables of the remaining 87 respondents, 15 decliners, and 269 nonrespondents are shown in Table 1. Physicians comprised 62% of the respondents, followed by nurse practitioners (28%) and nurses (13%). Comparisons between the respondent and nonrespondent groups showed overrepresentation of nonphysicians and women among respondents (p<0.001).

Table 1.

Demographics of Respondents (Nongenetic and Genetic Professionals), Decliners, and Nonrespondents

| |

All respondents (n=87) |

Nongenetics (n=81) |

Genetics (n=6) |

Decliners (n=15) |

Nonrespondents (n=269) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) |

| Physicians | 54 (62) | 53 (65) | 1 (17) | 11 (73) | 240 (90) |

| Medical School | |||||

| US/Canada | 50 (93) | 49 (92) | 1 (100) | 8 (73) | 188 (78) |

| Other (outside US/Canada) | 4 (7) | 4 (8) | 0 | 3 (27) | 51 (21) |

| Specialty | |||||

| Medical oncologist | 6 (11) | 6 (11) | 0 | 0 | 1 (0.4) |

| General surgeon | 12 (22) | 12 (23) | 0 | 0 | 25 (10) |

| OB/GYN | 28 (52) | 28 (53) | 0 | 7 (64) | 151 (63) |

| Other (Internal Med, Peds, Rad) | 8 (15) | 7 (13) | 1 (100) | 4 (36) | 63 (26) |

| Nurse practitioner | 24 (28) | 24 (30) | 0 | 2 (13) | 19 (7) |

| Nurse | 3 (3) | 3 (4) | 0 | 2 (13) | 5 (2) |

| Genetic counselor | 5 (6) | 0 | 5 (83) | 0 | 2 (1) |

| Physician assistant | 1 (1) | 1 (1) | 0 | 0 | 3 (1) |

| Work setting | |||||

| Community/Private practice | 78 (90) | 77 (95) | 1 (17) | 14 (93) | 264 (98) |

| Academic center | 6 (7) | 1 (1) | 5 (83) | 1 (7) | 4 (1.5) |

| Other | 3 (3) | 3 (4) | 0 | 0 | 1 (0.4) |

| Sex (% female) | 64 (74) | 59 (73) | 5 (83) | 11 (73) | 123 (48) |

Information on genetic testing practices and genetics training of respondents is summarized in Table 2. Just under half (44%) of respondents reported having completed clinical cancer genetics training, of whom the majority completed training through Myriad Genetics.

Table 2.

Genetic Testing Practices and Formal Training in Cancer Genetics Reported by Respondents

| |

All respondents (n=87) |

Nongenetics professionals (n=81) |

Genetics professionals (n=6) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | median (min, max) | median (min, max) | median (min, max) |

| No. of years provided testing services | 5 (1, 16) | 5 (1, 16) | 7 (2, 14) |

| No. of patients in last 12 months tested for inherited cancer susceptibility to: | |||

| Breast cancer | 15 (1, 255) | 15 (1, 255) | 45 (5, 130) |

| Ovarian cancer | 8 (1, 250) | 8 (1, 250) | 13 (2, 35) |

| Other cancer | 3 (0, 30) | 3 (0, 30) | 10 (2, 25) |

| No. of patients who asked about inherited cancer susceptibility testing over last 12 months | 20 (2, 500) | 20 (2, 500) | 160 (10, 336) |

| No. of patients seen for genetic counseling for hereditary cancer per week | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) |

| 0 | 25 (29) | 25 (32) | 0 |

| 1 to 5 | 52 (61) | 49 (62) | 3 (50) |

| 6 to 10 | 6 (7) | 3 (3.8) | 3 (50) |

| >10 | 2 (2) | 2 (2.6) | 0 |

| Any formal training course(s) in clinical cancer geneticsa | n (% yes) | n (% yes) | n (% yes) |

| All respondents | 38 (44) | 35 (44) | 3 (50) |

| Myriad training only | 20 | 20 | 0 |

| Myriad training+other | 10 | 10 | 0 |

| Other only | 8 | 5 | 3 |

One respondent did not answer the question regarding formal training in clinical cancer genetics.

BRCA knowledge and practice recommendations

As summarized in Table 3, assessment of BRCA knowledge indicated that most (96%) respondents were aware of paternal inheritance; however, a smaller proportion (61%) recognized that ≤10% of breast cancer is due to germline BRCA mutations. Practices related to management, risk assessment, and testing revealed that most recommend mammography (96%) and breast magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) (86%); however, 65% also considered breast ultrasonography as part of standard cancer surveillance recommendations. Moreover, in a patient with a pretest probability of 30% for having a mutation, only 43% recognized the need for comprehensive rearrangement testing (CRT), marketed as “BART,” when standard BRCA testing (i.e., BRCA full gene sequencing; five common rearrangements in BRCA1) did not detect a mutation. Finally, only 14% recognized appropriate family testing when a VUS was detected.

Table 3.

Summary of Responses Related to Knowledge and Recommendations for Genetic Testing and Medical Management

| |

All Respondents (n=87) |

Nongenetics (n=81) |

Genetics (n=6) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Question posed | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) |

| BRCA knowledge: | |||

| Females can inherit BRCA1 mutation from father's side | |||

| Yes | 83 (96) | 77 (95) | 6 (100) |

| No | 1 (1) | 1 (1) | 0 |

| Not sure | 3 (3) | 3 (4) | 0 |

| % breast cancer patients with germline BRCA mutation | |||

| ≤10% | 52 (61) | 46 (58) | 6 (100) |

| >10% | 33 (39) | 33 (42) | 0 |

| BRCA management, risk assessment, and testing recommendations: | |||

| Scenario 1: Screening recommendations for a 35-year-old BRCA mutation carrier who desires no prophylactic surgerya | |||

| Mammographyb | 81 (96) | 76 (96) | 5 (100) |

| Breast ultrasonographyb | 55 (65) | 54 (68) | 1 (20) |

| Breast MRIb | 72 (86) | 67 (85) | 5 (100) |

| Transvaginal ultrasonographyb | 64 (76) | 59 (75) | 5 (100) |

| CA-125 levelb | 59 (70) | 54 (68) | 5 (100) |

| Scenario 2: Management recommendations for a 40-year-old woman with a risk assessment of 30% for a BRCA mutation based on BRCAPRO, who has a negative comprehensive BRACAnalysisc | |||

| Reassure patient that risk for breast cancer is similar to general population | 31 (37) | 31 (40) | 0 |

| Advise patient that they are at increased breast cancer risk based on family cancer history | 71 (84) | 65 (83) | 6 (100) |

| Order BRACAnalysis Large Rearrangement Test | 35 (43) | 30 (39) | 5 (83) |

| Refer to a genetics professional | * | 45 (57) | * |

| Scenario 3: 38-year-old woman with breast cancer treated with unilateral mastectomy at age 32 who has a BRCA1 variant of uncertain significance (VUS). She has a sister with the same BRCA VUS who had breast cancer at age 40, and another sister who is age 42 and well. Recommendations for the 42-year-old sister include:d | |||

| Test for BRCA1 VUS only | 37 (44) | 36 (44) | 1 (17) |

| Undergo full BRCA1/2 analysis | 35 (42) | 35 (43) | 0 |

| No further testing at this time | 12 (14) | 7 (9) | 5 (83) |

Number (%) of respondents who would recommend screening method at least annually.

Three professionals (two nongenetics and one genetics) who do not make any recommendations were removed from the denominator to calculate valid percentages.

Number (%) of respondents who indicated that they would likely or always perform action.

Number (%) of respondents who chose each of the three mutually exclusive options.

Not applicable to genetics professionals.

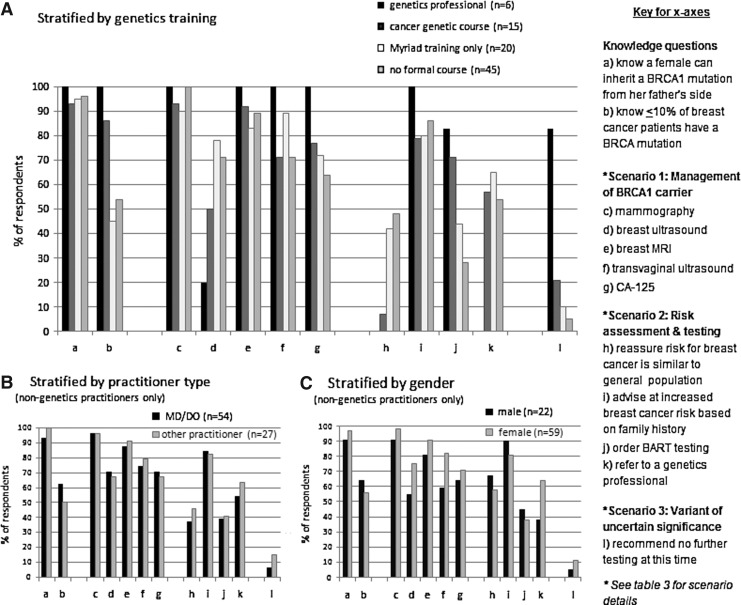

Additional comparisons of BRCA knowledge and practices were conducted through further subdividing the group of nongenetics professionals by type of genetics training (summarized in Fig. 2a). Overall, respondents across all groups correctly answered the knowledge question about paternal inheritance of BRCA. In contrast, those with no training or “Myriad only” training were less likely to know that germline BRCA mutations occur in ≤10% of women with breast cancer. As for recommended screening guidelines for BRCA carriers, over 70% of those with no training or “Myriad only” training recommended breast ultrasonography. As for testing recommendations, there was a general linear trend observed for both recognition of the need to offer CRT and appropriate family testing for a VUS.

FIG. 2.

BRCA knowledge, risk assessment, management, and testing recommendations. Stratified by (A) genetics training, (B) practitioner type, and (C) gender.

Finally, among nongenetics professionals, responses were compared by profession (i.e., physician versus other healthcare provider) and by gender. As shown in Figure 2b and 2c, most responses were not substantially different across groups.

Discussion

In this study, we surveyed a predominantly community-based sample of healthcare providers who offer BRCA testing services, the majority of whom reported no formal training in genetics. Our assessment of knowledge and practices related to identification, testing, and management of individuals at risk for BRCA mutations identified knowledge gaps pertaining to (1) proportions of breast and ovarian cancers with hereditary etiology; (2) management and genetic testing practices in high-risk families based on personal and/or family history of cancer; (3) testing practices when a BRCA VUS result is identified; and (4) nationally endorsed BRCA cancer screening guidelines.

Given that our sampling frame consisted solely of providers who offer BRCA testing, it is not surprising that respondents demonstrated higher knowledge than a nationally representative U.S. physician survey, in which the majority of respondents did not offer BRCA testing services (Wideroff et al., 2005). However, it is surprising that a substantial minority (39%) of our respondents did not know the prevalence of BRCA mutations, which is considered basic information that one could expect all providers of BRCA testing to know.

A large proportion of respondents also demonstrated a lack of understanding about cancer risks and genetic testing options following negative BRACAnalysis®. Specifically, less than half of respondents recommended CRT for a high-risk patient following negative BRACAnalysis®. CRC detects up to an additional 10% of mutations (Shannon et al., 2011; Judkins et al., 2012), and has been available since 2005. Unfortunately CRT has not been covered by many insurers until recently, following the issuance of the updated National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) guidelines, which now define comprehensive BRCA testing to include CRT (2012). However, Myriad has criteria for performing the test at no charge for any patient with a 30% or greater pre-test probability of carrying a BRCA mutation. The overwhelming lack of recognition regarding the availability of CRT for a patient at ≥30% risk of a BRCA mutation poses risk management liability issues for both healthcare providers and hospitals (Pal et al., accepted for publication); it also raises concerns about appropriate testing practices and the potential for the delivery of substandard care. In fact, a number of recent case reports highlight negative outcomes that can occur when genetic testing is performed without adequate genetic counseling by a trained genetics professional; these outcomes are serious, ranging from inappropriate prophylactic surgeries to premature death (Brierley et al., 2010; Caleshu et al., 2010; Esserman and Kaklamani, 2010; Robson et al., 2010).

Interestingly, most practitioners indicated that a high-risk patient who tests negative on comprehensive BRACAnalysis® remained at high risk of breast cancer based on her family history, yet over a third indicated they would reassure the patient that risk was similar to that of the general population. The etiology for this discrepancy is unclear, but it is possible that practitioners misunderstood the question.

Another challenging BRCA result involves a VUS, which represents a sequence change in which pathogenicity has not yet been determined and, consequently, does not help inform screening recommendations. For an at-risk family member unaffected with cancer, most practitioners inappropriately recommended site-specific testing for the previously identified VUS (which costs ∼$500) or full BRACAnalysis® (which costs over $3,000), consistent with findings from a recent survey of Texas physicians (Plon et al., 2011). Hence, inappropriate VUS testing may lead to unwarranted and substantially increased testing costs.

Despite the availability of NCCN practice guidelines for BRCA carriers, our findings identified management practices that may be enhanced through additional education. Specifically, NCCN-recommended breast cancer surveillance includes annual mammogram and breast MRI starting as early as age 25 (National Comprehensive Cancer Network, 2012). This is because MRI, which is generally superior to mammography, does not identify some cancers (e.g., ductal carcinoma in situ) with microcalcifications (Obdeijn et al., 2010). Our findings indicated over 85% follow NCCN recommendations; however, over 60% also recommended ultrasonography, which is not part of surveillance guidelines, and routine overuse represents a waste of resources.

Overall, study results highlight existing knowledge gaps among many nongenetics professionals who offer BRCA testing and reinforce the need for adequate training to ensure competence when delivering these specialized services. Not surprisingly, the type of training appears to influence provider knowledge. Specifically, trends in our data suggest that those who reported completing “Myriad training only” were less likely to know the prevalence of BRCA mutations, less likely to follow NCCN guidelines, and less likely than those with more formal genetics training to order CRT (i.e., BART) in a clinically appropriate situation in which testing would be covered by the laboratory at no charge. These findings fully support the content of the 2012 National Accreditation Program for Breast Centers (NAPBC) Commission on Cancer statement, which indicates that “Education limited to learning how to order a genetic test is not considered adequate training for risk assessment and genetic counseling” (p. 48). Study findings also raise concerns that inadequate provision of genetic services is a growing area of medical liability.

There are several developed countries outside the United States where the involvement of a genetic professional is required before initiating genetic testing (Rantanen et al., 2008). However, within the United States, no such requirements exist despite recommendations from several advisory committees and task forces regarding the importance of genetic counseling in the context of genetic testing for hereditary cancer (Oncology Nursing Society, 2009; U.S. Preventive Services Taskforce, 2005; National Comprehensive Cancer Network, 2012). Cost has been cited as a reason for not requiring the involvement of a trained genetics professional before initiating genetic testing (Hudson et al., 2006). Given that inappropriate testing and screening has great potential to increase costs, this should be factored into cost effectiveness analyses of genetic counseling and testing by cancer genetics professionals.

Regardless of economic factors, access to genetics professionals is cited as a barrier, especially in rural areas and certain states (Rosenthal, 2007; Vig et al., 2009). In Florida, the state in which the survey was conducted, the paucity of genetics professionals is of particular concern. As the fourth most populous state (U.S. Department of Commerce 2010 Census), Florida's ratio of genetic counselors is 2.3 per 1 million persons in the U.S. population (U.S. Department of Commerce 2010 Census; National Society of Genetic Counselors, 2012). In fact, of the top 10 most populous states, Florida has the fewest certified geneticists and genetic counselors per 1 million residents (U.S. Department of Commerce 2010 Census; American Board of Medical Genetics, 2012; National Society of Genetic Counselors, 2012). Given that access to genetics professionals is an independent predictor of physician referrals (Vig et al., 2009), our study highlights the need to actively recruit qualified genetics professionals to states such as Florida in order to enhance the delivery of these specialized services. However, a significant barrier to the provision of adequate genetic services is the low reimbursement rates, which can often result in these services costing more than the direct revenue they generate (McPherson et al., 2008; Tung, 2011); this needs to be addressed at a policy level. Hospital and Health Maintenance Organization administrators will also need to examine the benefit of hiring genetics professionals in terms of reducing the medical liability to their health-care providers and improving the quality of care for patients and families. Alternative means to gain remote access to these services in areas that lack qualified genetics professionals include subcontracting services through an academic partner or through telemedicine. Ultimately, the development of collaborative partnerships between genetics and nongenetics professionals is essential to promote successful strategies to offer high quality care to those with inherited cancer predisposition (Cohen et al., 2009; Geier et al., 2009). This approach leverages the multidisciplinary care for challenging cases while enabling patients to remain in their community for long-term follow-up care.

A number of strengths support the current study, including the real-world implications for BRCA testing practices, particularly because the majority of clinical BRCA testing within the United States is ordered in the community setting. Furthermore, the survey was based in Florida, a state with relatively few genetics professionals that has been the target of multiple direct to consumer marketing campaigns (Hull and Prasad, 2001; Matloff and Caplan, 2008), which makes it an ideal state to conduct such a survey. Finally, we were able to compare demographic information on respondents and nonrespondents, which enabled us to assess for response bias and evaluate how it may have influenced our results. Despite an over-representation of females and nonphysicians, responses to most questions did not generally differ based on gender or type of practitioner (MD versus other). This reduces the impact of potential response bias on our findings, thereby enhancing generalizability of results. Nevertheless, potential gender differences in cancer screening recommendations and referral to a genetic professional could have lead to overestimating proportions: (1) adhering to NCCN screening guidelines for BRCA1 carriers, (2) referring to a genetics professional for a high-risk woman negative on comprehensive BRACAnalysis®, and (3) recommending breast ultrasonography. Thus (with the exception of breast ultrasonography), our findings probably represent a best-case scenario especially given that respondents were more knowledgeable than practitioners who have responded to prior surveys that asked the same knowledge questions (Wideroff et al., 2005; Myers et al., 2006).

Despite these strengths, the low response rate limited our ability to formally test whether differences between groups were statistically significant. However, we observed several consistent trends that revealed noticeable and substantial differences based on presence and type of cancer genetics training. Additional limitations are related to the self-reported nature of the data and inability to measure actual practitioner behaviors as part of this study. However, the use of clinical scenarios has been found to correlate highly with clinical decision-making behaviors in a number of studies (Veloski et al., 2005). Lastly, although we were able to categorize participants based on type of cancer genetics education, these categories are likely to be somewhat heterogeneous.

In summary, our findings suggest that involvement of genetics professionals in the provision of BRCA testing services has great potential to both improve cost effectiveness of BRCA testing and enhance patient care through promotion of best practices based on national guidelines. As costs of genetic testing drop exponentially, due to advances in sequencing technologies (Chan et al., 2012) and multigene panels that enable testing for multiple inherited conditions simultaneously, demand for genetic testing may increase. Coupled with these advances will be the rise in complexity associated with interpreting test results as well as determining optimal recommendations and management of patients and their family members. As such, these advances will only magnify the need for involvement of genetics professionals in the provision of multidisciplinary care to those with inherited cancer predisposition. Specifically, genetics professionals are expected to help lead the integration of genetic and genomic knowledge and skills into clinical practice. Thus, key components to realizing the benefits of genetics and genomics innovations include expansion in access to genetics expertise. Furthermore, adequate insurance reimbursement is required to support widespread provision of high-quality, cost-effective services. Finally, regulation of these services at a policy level is needed to ensure competency of those who offer testing services, which is ultimately critical to maximize patient benefit.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a grant through Florida Biomedical (IBG09-34198).

We acknowledge the Survey Methods Core Facility at the H. Lee Moffitt Cancer Center & Research Institute for developing versions of the survey that could be scanned into an electronic data file.

Author Disclosure Statement

This study was supported by a grant through Florida Biomedical (IBG09-34198). However, Florida Biomedical played no role in the study design, data collection, data analysis, or the decision to publish this research. The authors have no real or perceived conflicts of interest to disclose. The authors report no competing financial interests or personal relationships that might bias this research.

References

- Albrecht TL. Ruckdeschel JC. Ray FL, 3rd, et al. A portable, unobtrusive device for videorecording clinical interactions. Behav Res Methods. 2005;37:165–169. doi: 10.3758/bf03206411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Board of Medical Genetics. Members. 2012. www.abmg.org/pages/searchmem.shtml. [Jun 15;2012 ]. www.abmg.org/pages/searchmem.shtml

- Antoniou A. Pharoah PD. Narod S, et al. Average risks of breast and ovarian cancer associated with BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutations detected in case Series unselected for family history: a combined analysis of 22 studies. Am J Hum Genet. 2003;72:1117–1130. doi: 10.1086/375033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blazer KR. Macdonald DJ. Culver JO, et al. Personalized cancer genetics training for personalized medicine: improving community-based healthcare through a genetically literate workforce. Genet Med. 2011;13:832–840. doi: 10.1097/GIM.0b013e31821882b7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brierley KL. Campfield D. Ducaine W, et al. Errors in delivery of cancer genetics services: implications for practice. Conn Med. 2010;74:413–423. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caleshu C. Day S. Rehm HL, et al. Use and interpretation of genetic tests in cardiovascular genetics. Heart. 2010;96:1669–1675. doi: 10.1136/hrt.2009.190090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan M. Mo Ji S. Yeo ZX, et al. Development of a next-generation sequencing method for BRCA mutation screening: a comparison between a high-throughput and a benchtop platform. J Mol Diagn. 2012;14:602–612. doi: 10.1016/j.jmoldx.2012.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen S. Parmigiani G. Meta-analysis of BRCA1 and BRCA2 penetrance. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:1329–1333. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.09.1066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen SA. McIlvried D. Schnieders J. A collaborative approach to genetic testing: a community hospital's experience. J Genet Couns. 2009;18:530–533. doi: 10.1007/s10897-009-9243-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doksum T. Bernhardt BA. Holtzman NA. Does knowledge about the genetics of breast cancer differ between nongeneticist physicians who do or do not discuss or order BRCA testing? Genet Med. 2003;5:99–105. doi: 10.1097/01.GIM.0000055198.63593.32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Domchek S. Weber BL. Genetic variants of uncertain significance: flies in the ointment. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:16–17. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.14.4154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esserman L. Kaklamani V. Lessons learned from genetic testing. JAMA. 2010;304:1011–1012. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.1263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forum NCP Medicine Io. Cancer-Related Genetic Testing and Counseling: Workshop Proceedings. The National Academies Press; Washington, D.C.: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Geier LJ. Mulvey TM. Weitzel JN. American Society of Clinical Oncology. Clinical Cancer Genetics Remains a Specialized Area: How Do I Get There From Here? ASCO 2009 Educational Book: Practice Management and Information Technology. 2009.

- Gynecologists ACoOa. ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 103: Hereditary breast and ovarian cancer syndrome. Obstet Gynecol. 2009;113:957–966. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181a106d4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hudson KL. Murphy JA. Kaufman DJ, et al. Oversight of US genetic testing laboratories. Nat Biotechnol. 2006;24:1083–1090. doi: 10.1038/nbt0906-1083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hull SC. Prasad K. Reading between the lines: direct-to-consumer advertising of genetic testing in the USA. Reprod Health Matters. 2001;9:44–48. doi: 10.1016/s0968-8080(01)90089-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaen CR. Stange KC. Nutting PA. Competing demands of primary care: a model for the delivery of clinical preventive services. J Fam Pract. 1994;38:166–171. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Judkins T. Rosenthal E. Arnell C, et al. Clinical significance of large rearrangements in BRCA1 and BRCA2. Cancer. 2012;118:5210–5216. doi: 10.1002/cncr.27556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keating NL. Stoeckert KA. Regan MM, et al. Physicians' experiences with BRCA1/2 testing in community settings. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:5789–5796. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.17.8053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matloff E. Caplan A. Direct to confusion: lessons learned from marketing BRCA testing. Am J Bioeth. 2008;8:5–8. doi: 10.1080/15265160802248179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McPherson E. Zaleski C. Benishek K, et al. Clinical genetics provider real-time workflow study. Genet Med. 2008;10:699–706. doi: 10.1097/gim.0b013e318182206f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myers MF. Chang MH. Jorgensen C, et al. Genetic testing for susceptibility to breast and ovarian cancer: evaluating the impact of a direct-to-consumer marketing campaign on physicians' knowledge and practices. Genet Med. 2006;8:361–370. doi: 10.1097/01.gim.0000223544.68475.6c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Accreditation Program for Breast Centers. Breast Center Standards Manual. 2012. http://napbc-breast.org/standards/2012standardsmanual.pdf. [Jun 15;]. http://napbc-breast.org/standards/2012standardsmanual.pdf

- National Comprehensive Cancer Network. Genetic/Familial High-risk Assessment: Breast and Ovarian. 2012. www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/recently_updated.asp. [Jul 10;2012 ]. www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/recently_updated.asp [DOI] [PubMed]

- National Society of Genetic Counselors. Find a Genetic Counselor. 2012. www.nsgc.org/FindaGeneticCounselor/FindAGeneticCounselorbyInformation/tabid/68/Default.aspx. [Jun 15;]. www.nsgc.org/FindaGeneticCounselor/FindAGeneticCounselorbyInformation/tabid/68/Default.aspx

- Obdeijn IM. Loo CE. Rijnsburger AJ, et al. Assessment of false-negative cases of breast MR imaging in women with a familial or genetic predisposition. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2010;119:399–407. doi: 10.1007/s10549-009-0607-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pal T. Permuth-Wey J. Betts JA, et al. BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations account for a large proportion of ovarian carcinoma cases. Cancer. 2005;104:2807–2816. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pal T. Radford C. Vadaparampil ST, et al. Practical Considerations in the delivery of genetic counseling and testing services for inherited cancer predisposition. Community Oncology (accepted for publication) [Google Scholar]

- Peterson SK. Rieger PT. Marani SK, et al. Oncology nurses' knowledge, practice, and educational needs regarding cancer genetics. Am J Med Genet. 2001;98:3–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plon SE. Cooper HP. Parks B, et al. Genetic testing and cancer risk management recommendations by physicians for at-risk relatives. Genet Med. 2011;13:148–154. doi: 10.1097/GIM.0b013e318207f564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rantanen E. Hietala M. Kristoffersson U, et al. Regulations and practices of genetic counselling in 38 European countries: the perspective of national representatives. Eur J Hum Genet. 2008;16:1208–1216. doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2008.93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riley BD. Culver JO. Skrzynia C, et al. Essential elements of genetic cancer risk assessment, counseling, and testing: updated recommendations of the National Society of Genetic Counselors. J Genet Couns. 2012;21:151–161. doi: 10.1007/s10897-011-9462-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robson ME. Storm CD. Weitzel J, et al. American Society of Clinical Oncology policy statement update: genetic and genomic testing for cancer susceptibility. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:893–901. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.27.0660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenthal ET. Shortage of genetics counselors may be anecdotal, but need is real. Oncology Times. 2007;29:34–36. [Google Scholar]

- Shannon KM. Rodgers LH. Chan-Smutko G, et al. Which individuals undergoing BRAC analysis need BART testing? Cancer Genet. 2011;204:416–422. doi: 10.1016/j.cancergen.2011.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oncology Nursing Society. Role of the Oncology Nurse in Cancer Genetic Counseling. 2009. www.ons.org/Publications/Positions/GeneticCounseling/ [Oct 17;]. www.ons.org/Publications/Positions/GeneticCounseling/

- Tung N. Management of women with BRCA mutations: a 41-year-old woman with a BRCA mutation and a recent history of breast cancer. JAMA. 2011;305:2211–2220. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Commerce. United States Census. 2010. www.census.gov/popest/data/state/totals/2011/index.html. [Jun 15;]. www.census.gov/popest/data/state/totals/2011/index.html

- U.S. Preventive Services Taskforce. Genetic Risk Assessment and BRCA Mutation Testing for Breast and Ovarian Cancer Susceptibility. 2005. www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/uspsbrgen.htm. [Aug 29;2012 ]. www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/uspsbrgen.htm

- Vadaparampil ST. Wideroff L. Olson L, et al. Physician exposure to and attitudes toward advertisements for genetic tests for inherited cancer susceptibility. Am J Med Genet A. 2005;135:41–46. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.30681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Veloski J. Tai S. Evans AS, et al. Clinical vignette-based surveys: a tool for assessing physician practice variation. Am J Med Qual. 2005;20:151–157. doi: 10.1177/1062860605274520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vig HS. Armstrong J. Egleston BL, et al. Cancer genetic risk assessment and referral patterns in primary care. Genet Test Mol Biomarkers. 2009;13:735–741. doi: 10.1089/gtmb.2009.0037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wideroff L. Vadaparampil ST. Greene MH, et al. Hereditary breast/ovarian and colorectal cancer genetics knowledge in a national sample of US physicians. J Med Genet. 2005;42:749–755. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2004.030296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]