Abstract

Background:

Preeclampsia is an important cause of maternal morbidity and mortality with unclear cause. It is believed that inflammation plays an important role in the pathogenesis of preeclampsia. Periodontal disease is a chronic inflammatory infectious condition which commonly involves humans. Recently, chronic infection was linked to atherosclerosis. Atherosclerosis shares some histopathologic features with uteroplacental atherosis of preeclamptic women. This study was aimed to investigate the presence of periopathogenic bacteria in the placental tissue of preeclamptic women, and compare it with women with normal pregnancy.

Methods:

Samples were obtained from 23 placentas of preeclamptic women and from 23 age-matched healthy pregnant women. Qualitative polymerase chain reaction was performed to detect the presence of five periopathogenic bacteria.

Results:

There was no significant difference between the two groups regarding the relative frequency of women with different types of periopathogenic bacterial infection of the placenta. In addition, there was no significant difference in the number of women with any type of infection of the placenta (regardless of the type of periopathogenic bacteria) [14 (61%) mothers with placental infection in the case group vs. 18 (78%) mothers in the control group, P value = 0.16].

Conclusions:

This study did not show any significant difference between preeclamptic women and healthy women with normal pregnancy regarding the periopathogenic bacterial profile of the placenta.

Keywords: Periodontitis, periopathogenic bacteria, placenta, preeclampsia

INTRODUCTION

Preeclampsia is an important cause of maternal morbidity and mortality which complicates approximately 3% of all pregnancies.[1,2] Although several theories including abnormal placentation, cardiovascular maladaptation to pregnancy, genetic and immune mechanisms, increased systemic inflammatory response, and nutritional, hormonal, and angiogenic factors have been suggested to cause preeclampsia, the etiology of this serious disorder is still unclear.[3–7]

Compared to women with normal pregnancy, preeclamptic women have a significantly greater systemic inflammatory response.[4] It suggests an important role for inflammation in the pathogenesis of preeclampsia.[4,8] Infection is considered as an important source of inflammation that may play a role in many adverse pregnancy outcomes including preeclampsia.[9–11] Infection can either increase the risk of acute uteroplacental atherosis, and therefore initiate preeclampsia, or amplify the maternal systemic inflammatory response, and consequently potentiate preeclampsia.[12,13]

According to the suggested association between infection and preeclampsia, periodontal infection, which is one of the most common chronic infectious disorders in humans, might be linked to preeclampsia.[10,14–16] Depending on the definition of periodontal disorders and the population, the prevalence of periodontal disorders is reported to be between 10% and 60%.[14,15]

Detection of oral pathogens in atherosclerotic plaques has been reported. Uteroplacental atherosis shares some histopathologic features with atherosclerosis.[17] Therefore, some studies suggest an association between preeclampsia and periodontitis, and some believe that periodontal pathogens may be present in the placenta of women with preeclampsia.[8,17–20] However, it is still controversial due to some claims that deny such association.[21]

Given the above evidence and the controversy on this topic, this study was aimed to investigate the presence of periopathogenic bacteria in the placental tissue of preeclamptic women, and compare it with women with normal pregnancy.

METHODS

After approval for the study by the ethics committee of Isfahan University of Medical Sciences (research project number 390058) and informed consent were obtained, this case–control study was performed on 46 women (23 preeclamptic women and 23 age-matched healthy women with normal pregnancy) between June 2011 and February 2012 in Beheshti and Al-zahra hospitals, Isfahan, Iran.

We obtained the placental samples only from those who underwent cesarean section in order to avoid possible vaginal and cervical contamination.

Preeclamptic women who underwent cesarean section formed the case group. According to the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) guideline, preeclampsia was considered when a woman had hypertension (diastolic blood pressure of at least 90 mm Hg or a systolic pressure of at least 140 mm Hg) after 20th week of gestation plus proteinuria (urinary excretion of >300 mg protein/24 h, or two random urine specimens obtained at least 4 h apart demonstrating ≥1+by dipstick testing or measured as >30 mg protein per desyliter).[8,22]

Women who underwent cesarean section for reasons other than preeclampsia were assigned to the control group.

The excluding criteria were multiple gestation, diabetes mellitus, urinary tract infection, rupture of membrane, chronic hypertension, and having other medical disorders. In addition, women who had received antibiotics over the 5 months before the study, or had been treated with calcium channel blockers, phenytoin, or cyclosporine A for more than 3 months before the investigation were excluded from this study.

After qualifying patients according to the aforementioned criteria, demographic and clinical features of patients including age, parity, gravidity, and gestational age at delivery were recorded. Besides these, the labor phase at the time of delivery and the status of membranes were registered.

After the cesarean section, four placental samples were taken from both central and marginal areas of each placenta by a single physician under sterile condition. Two samples were obtained from the maternal side and two samples from the fetal side.

To make the study blind, a code was assigned to each sample. Then, the samples were sent to the laboratory for evaluation by qualitative polymerase chain reaction (PCR) regarding the presence of five periopathogenic bacteria (Actinomycetemcomitans, Prevotella intermedia, Porphyromonas gingivalis, Treponema denticula, and Tannerella forsythensis).

Data were analyzed by SPSS 16.5, and Chi-square test and independent t-test were used when appropriate. P values less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Baseline data

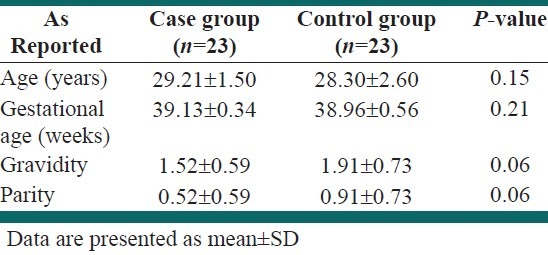

There was no significant difference between the two groups in the mean of age, gestational age, gravidity, and parity [Table 1].

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics

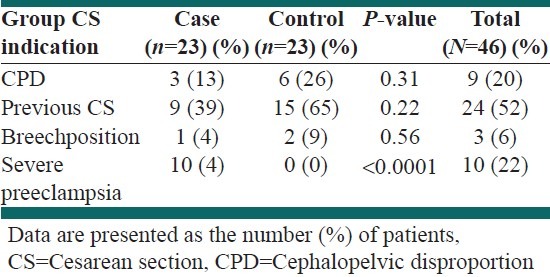

Indications of cesarean section in each group are presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Indications of cesarean section in each group

Periopathogenic bacterial infection of the placenta

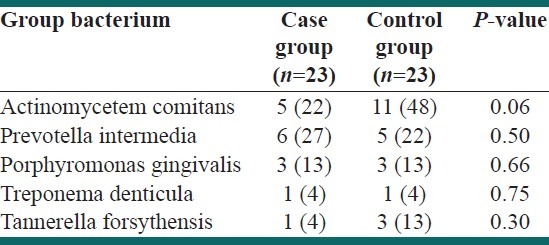

The two groups were compared regarding the number of cases with positive periopathogenic bacterial infection of the placenta, and no significant difference was observed [Table 3].

Table 3.

Frequency of women with different types of periopathogenic bacterial infection of the placenta in each group

Surprisingly, the number of women with placental periopathogenic bacterial infection was higher in the control group; however, this difference was not statistically significant.

Data are presented as the number (%) of patients infected with different types of periopathogenic bacteria in each group

Moreover, we compared the number of mothers who had positive placental infection (regardless of the type of periopathogenic bacteria) and found no significant difference between the two groups [14 (61%) mothers with placental infection in the case group vs. 18 (78%) mothers in the control group, P value = 0.16].

DISCUSSION

The present study demonstrated no significant difference between preeclamptic women and healthy women with normal pregnancy regarding the relative frequency of placental infection with periopathogenic bacteria.

Surprisingly, we found a non-significantly higher frequency of placental infection with periopathogenic bacteria in healthy women, which is inconsistent with the findings reported by previous studies.

The study design of Barak et al. that was performed earlier was almost similar to this study. They found significantly higher frequency of infected placental samples in the preeclampsia group compared with healthy women.

Having found Ta. forsythensis, Po. gingivalis, A. actinomycetemcomitans, Pr. intermedia and Fusobacterium nucleatum in placenta, Barak et al. suggested that these pathogens may have transmitted hematogenously and played a role in the formation of placental atherosis.

They also reported significantly higher bacterial count in the preeclamptic women;[17] however, we do not have data about bacterial count detected by qualitative PCR.

While all the five investigated types of periopathogenic bacteria were found in both case and control groups of our study, Barak et al. found all types in the case group and only three types in the control group. These dissimilarities between what we found and the findings of Barak et al. could be attributed to some factors, including racial and socioeconomic differences.

For instance, the difference could be caused by different levels of oral hygiene of the studied women. In other words, it could be supposed that women who were investigated in the Barak, et al. study had better average level of oral hygiene than ours, so the difference between women with good oral hygiene and those with poor oral hygiene has been more prominent and has led to significant differences between the two groups. However, it is just a hypothesis, not a definite reason, because we do not have any idea about the baseline level of oral hygiene of patients, either from our study or from the Barak, et al. study.

Another investigation performed by Swati et al. confirms the findings of Barak et al.[19] The important finding which could be helpful in interpretation of what we found is that Swati et al. had detected periopathogenic bacteria in the placenta of two cases who did not have periodontal diseases. This finding shows that having infected placenta with periopathogenic bacteria does not necessarily mean having periodontitis. It was suggested that these pathogens might have gained access to the placenta through the genital tract as an ascending infection, or they might have been translocated retrogradely from the peritoneal cavity through the fallopian tubes. Based on this condition, general hygiene could also play an important role in this regard, and can affect the probability of having placental infection with periopathogenic bacteria in the absence of periodontitis. This emphasizes the role of socioeconomic status in the presence of periopathogenic bacteria in the placenta.

Another study by Siqueira et al. on Brazilian women revealed that maternal periodontitis is a risk factor associated with preeclampsia.[18] Their study design was completely different from that of this investigation. They defined the clinical criteria for periodontitis, and then assessed the relationship between periodontitis and preeclampsia after controlling the confounders. Siqueira, et al. did not study the bacterial profile of the placenta. They believe that maternal infections such as periodontitis accelerate cytokine release and endothelial dysfunction, which increase the risk of preeclampsia.[18,23–25] The main difference between our study and the study of Siqueira, et al. is that we investigated the local effects of periodontitis on the placenta of preeclamptic women, while they investigated the systemic effects of periodontitis on preeclampsia.

Therefore, although we did not find any evidence that supports the role of placental infection with periopathogenic bacteria, we are not able to rule out the suggested association between preeclampsia and periodontitis at this stage.

Another study on a relatively large number of Jordanian women investigated the association between periodontal parameters and preeclampsia, and reported no association between them.[21] This conclusion partly supports our findings. Khader et al. suggested that differences in study design, sample size, periodontal disease definition, and adjustment criteria may be the reasons of their findings.

CONCLUSIONS

In summary, our study did not show any significant difference between preeclamptic women and healthy women with normal pregnancy regarding the periopathogenic bacterial profile of the placenta. We suggest further investigations on larger sample size with better control of confounding factors such as socioeconomic status, accompanied by simultaneous assessment of periodontal parameters to achieve more accurate results.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared

REFERENCES

- 1.Conde-Agudelo A, Belizan JM. Risk factors for pre-eclampsia in a large cohort of Latin American and Caribbean women. BJOG. 2000;107:75–83. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2000.tb11582.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Villar J, Say L, Shennan A, Lindheimer M, Duley L, Conde-Agudelo A, et al. Methodological and technical issues related to the diagnosis, screening, prevention, and treatment of pre-eclampsia and eclampsia. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2004;85(Suppl 1):28–41. doi: 10.1016/j.ijgo.2004.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lam C, Lim KH, Karumanchi SA. Circulating angiogenic factors in the pathogenesis and prediction of preeclampsia. Hypertension. 2005;46:1077–85. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000187899.34379.b0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Redman CW, Sargent IL. Latest advances in understanding preeclampsia. Science. 2005;308:1592–4. doi: 10.1126/science.1111726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Roberts JM, Pearson G, Cutler J, Lindheimer M. Summary of the NHLBI working group on research on hypertension during pregnancy. Hypertension. 2003;41:437–45. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000054981.03589.E9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Haddad T. Update on pre-eclampsia. Int Anesthesiol Clin. 2002;40:115–35. doi: 10.1097/00004311-200210000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Higgins JB. Pre-eclampsia-Still a disease of theories? Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol. 1998;10:129–33. doi: 10.1097/00001703-199804000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Conde-Agudelo A, Villar J, Lindheimer M. Maternal infection and risk of preeclampsia: Systematic review and metaanalysis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2008;198:7–22. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2007.07.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lopez NJ, Gutierrez J. Periodontal therapy may reduce the risk of preterm low birth weight in women with periodontal disease: A randomized controlled trial. J Periodontol. 2002;73:911–24. doi: 10.1902/jop.2002.73.8.911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Srinivas SK, Sammel MD, Stamilio DM, Clothier B, Jeffcoat MK, Parry S, et al. Periodontal disease and adverse pregnancy outcomes: Is there an association.? Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2009;200:497.e1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2009.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Khader YS, Taani Q. Periodontal diseases and the risk of preterm birth and low birth weight: A meta-analysis. J Periodontol. 2005;76:161–5. doi: 10.1902/jop.2005.76.2.161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Herrera JA, Chaudhuri G, Lopez-Jaramillo P. Is infection a major risk factor for preeclampsia? Med Hypotheses. 2001;57:393–7. doi: 10.1054/mehy.2001.1378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.von Dadelszen P, Magee LA. Could an infectious trigger explain the differential maternal response to the shared placental pathology of preeclampsia and normotensive intrauterine growth restriction? Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2002;81:642–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Albandar JM, Rams TE. Global epidemiology of periodontal diseases: An overview. Peridontol 2000. 2002;29:7–10. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0757.2002.290101.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Papapanou PN. Periodontal diseases: epidemiology. Ann Periodontol. 1996;1:1–36. doi: 10.1902/annals.1996.1.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Page RC, Komman KS. The pathogenesis of human periodontitis: An introduction. Periodontol. 1997;2000:9–11. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0757.1997.tb00189.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Barak S, Oettinger-Barak O, Machtei EE, Sprecher H, Ohel G. Evidence of periopathogenic microorganisms in placentas of women with preeclampsia. J Periodontol. 2007;78:670–6. doi: 10.1902/jop.2007.060362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Siqueira FM, Cota LO, Costa JE, Haddad JP, Lana AM, Costa FO. Maternal periodontitis as a potential risk variable for preeclampsia: A case-control study. J Periodontol. 2008;79:207–15. doi: 10.1902/jop.2008.070174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Swati P, Thomas B, Vahab SA, Kapaettu S, Kushtagi P. Simultaneous detection of periodontal pathogens in subgingival plaque and placenta of women with hypertension in pregnancy. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2012;285:613–9. doi: 10.1007/s00404-011-2012-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Boggess KL, Murtha A, Moss K, Beck J, Offenbacher S. Maternal periodontal disease is associated with an increased risk for pre-eclampsia. Obstet Gynecol. 2003;101:227–31. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(02)02314-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Khader YS, Jibreal M, Al-Omiri M, Amarin Z. Lack of association between periodontal parameters and preeclampsia. J Periodontol. 2006;77:1681–7. doi: 10.1902/jop.2006.050463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.ACOG practice bulletin. Diagnosis and management of preeclampsia and eclampsia. Number 33, January 2002. Obstet Gynecol. 2002;99:159–67. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(01)01747-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ness RB, Sibai SB. Shared and disparate components of the pathophysiologies of fetal growth restriction and preeclampsia. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2006;195:40–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2005.07.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Azuma M. Fundamental mechanisms of host immune responses to infection. J Periodontal Res. 2006;41:361–73. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0765.2006.00896.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Offenbacher S, Beck JD, Lieff S, Slade G. Role of periodontitis in systemic health: Spontaneous preterm birth. J Dent Educ. 1998;62:852–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]