This study found a high incidence of hepatitis C virus infection among a sample of human immunodeficiency virus–infected men who have sex with men engaged in primary care in Boston, Massachusetts, in the absence of traditional risk factors such as injection drug use.

Keywords: HIV, hepatitis C virus, men who have sex with men, screening, incidence

Abstract

Background. Sexually transmitted hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection is an emerging epidemic among human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)–infected men who have sex with men (MSM). HCV may be underrecognized in this population, historically thought to be at low risk.

Methods. We determined the prevalence and incidence of HCV among HIV-infected men at Fenway Health between 1997 and 2009. We describe characteristics associated with HCV.

Results. Of 1171 HIV-infected men, of whom 96% identify as MSM, 1068 (91%) were screened for HCV and 64 (6%) had a positive HCV antibody (Ab) result at initial screening. Among the 995 men whose initial HCV Ab result was negative, 62% received no further HCV Ab testing. Among the 377 men who had ≥1 additional HCV Ab test, 23 (6%) seroconverted over 1408 person-years, for an annualized incidence of 1.63 per 100 person-years (95% confidence interval, .97–2.30). Among the 87 HIV-infected MSM diagnosed with prevalent or incident HCV, 33% reported history of injection drug use, 46% noninjection drug use (NIDU), and 70% sexually transmitted infections (STIs). Sixty-four (74%) of HCV-infected MSM developed chronic HCV; 22 (34%) initiated HCV treatment and 13 (59%) of treated persons achieved a sustained virologic response (SVR).

Conclusions. Prevalent and incident HCV, primarily acquired through nonparenteral means, was common in this HIV-infected population despite engagement in care. STIs and NIDU were common among HIV/HCV-coinfected MSM. SVR rates were high among those who underwent HCV treatment. All sexually active and/or substance-using HIV-infected MSM should receive routine and repeated HCV screening to allow for early diagnosis and treatment of HCV.

Although injection drug use (IDU) is the principal mode of hepatitis C virus (HCV) transmission in the United States, 10%–40% of persons in many epidemiologic studies have no identifiable parenteral source of infection [1]. Among HIV-infected men who have sex with men (MSM), evidence is accumulating that HCV transmission may be facilitated by traumatic sexual practices [2–11] and noninjection drug use (NIDU) [12, 13], in the absence of IDU.

Although the epidemiology of HCV among HIV-infected injection drug users is well described, less is known about the prevalence and incidence of HCV among HIV-infected MSM in the United States. A study of HIV-infected male participants in the US AIDS Clinical Trial Group Longitudinal Linked Randomized Trials cohort found an annualized HCV incidence of 0.5 per 100 person-years between 1996 and 2008. Notably, 75% of seroconverters reported no history of IDU [14], but this sample might not reflect the diversity of HIV-infected MSM in care. A study conducted among noninjection drug–using HIV-infected MSM in San Francisco found HCV seroprevalence to decline from 8.7% in 2004 to 4.5% in 2008 [15]. These findings contrast with multiple European studies that have identified an increasing incidence of HCV among HIV-infected MSM [16, 17]. An important barrier to assessing the burden of HCV among HIV-infected MSM in the United States is that rates of initial and repeat HCV antibody (Ab) screening in this population remain low [18].

Fenway Health, in Boston, Massachusetts, provides care to >20 000 patients, of whom approximately 50% are MSM and other sexual and gender minorities [19]. An estimated 96% of HIV-infected men who seek care at Fenway Health identify as MSM. Among the >1750 HIV-infected MSM in care at Fenway Health, the prevalence of self-reported IDU is <3%. This large sample of noninjection drug–using, HIV-infected MSM, who are engaged in care at a single site, offers a unique opportunity to explore the epidemiology of HCV among a population of patients previously perceived to be at low risk.

METHODS

Study Design

A retrospective analysis was performed through data abstraction from a standardized electronic medical record database (Centricity). To capture patients actively engaged in care, all HIV-infected men seen at Fenway Health at least twice between January 2008 and June 2009 were included in the analysis. Data from 1997 to 2009 were collected on patient demographics, self-reported risk factors for HIV infection, sexually transmitted infections (STIs), self-reported substance use (excluding alcohol use), and HCV Ab results (Abbott HCV EIA 1997–2006; Bayer Advia Centaur HCV 2006–2009). For patients with a positive HCV Ab result, data were abstracted on plasma HCV RNA, HCV genotype, liver function tests, referral to an off-site HIV/HCV-coinfection clinic, liver biopsy results, HCV treatment, and achievement of sustained virologic response (SVR), defined as an undetectable HCV plasma RNA 6 months after completion of HCV therapy.

Among patients with incident HCV, alanine aminotransferase (ALT) data were examined to describe documented rises prior to HCV Ab seroconversion. Among patients with chronic HCV infection, defined as the presence of HCV RNA in the blood for >6 months, aspartate aminotransferase (AST)–to–platelet index (APRI) scores [20] were calculated using last documented AST and platelet values, to noninvasively assess degree of liver fibrosis. Based on the APRI index, 85% of individuals with a score <0.5 are likely to have no significant liver fibrosis, and 85% of individuals with a score >1.5 are likely to have significant fibrosis [20].

Statistical Analysis

Among patients who were previously untested or had a negative HCV Ab result, the proportion that underwent HCV Ab testing was calculated yearly from 1997 to 2009. Pearson correlations were used to detect linear trends in the number of HCV Ab tests performed per year and the proportion of HCV Ab-positive results per year. For patients with at least 1 negative HCV Ab result, the frequency of repeat Ab testing was also examined. Baseline characteristics were compared between patients who received no HCV Ab testing vs those who received 1 or more HCV Ab test over the study period. Among all tested patients, the proportion with an HCV Ab–positive result upon initial testing, including those with known HCV prior to entry into care at Fenway Health, provided the baseline HCV prevalence. For patients with an initial HCV Ab-negative result and at least 1 repeat HCV Ab test, HCV incidence was calculated by dividing number of seroconversion events by person-time at risk; a 95% confidence interval was calculated assuming a Poisson distribution. Person-time was calculated using the dates of the first negative HCV Ab result and the first positive HCV Ab result. To account for variable intervals of HCV Ab testing, the date of seroconversion was reassigned as halfway between the date of the last negative and first positive HCV Ab result, using previously described methods [21, 22]. Bivariate significance testing was completed using Mann-Whitney U tests for continuous variables and χ2 and Fisher exact tests for categorical variables. Tests were 2-tailed with a significance level of .05. Analyses were performed using SAS software, version 9.2 (Cary, North Carolina).

RESULTS

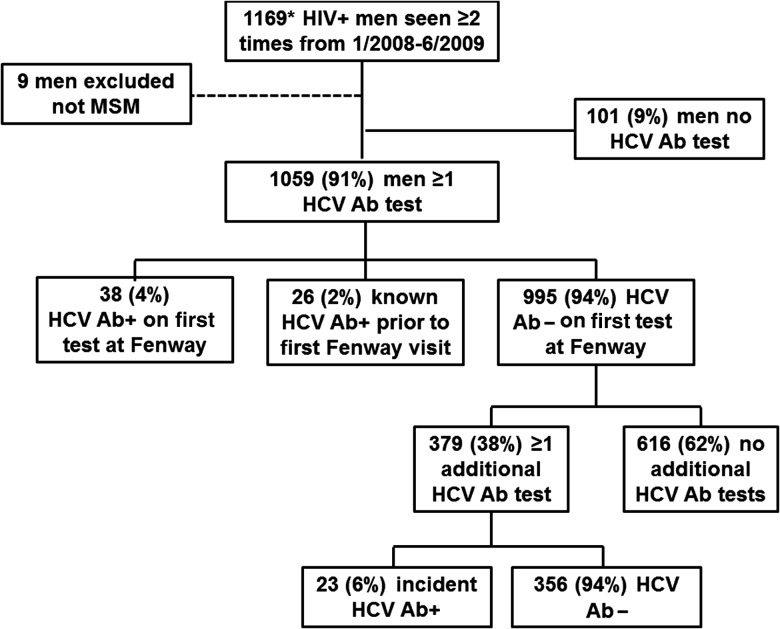

Of 1169 HIV-infected men seen at least twice between January 2008 and June 2009, 9 men were excluded who did not identify as MSM. Of the remaining 1160 men, 1059 (91%) had at least 1 HCV Ab test (Figure 1). The 101 (9%) HIV-infected men who were not tested for HCV did not differ from those who were tested for HCV by age, race, or baseline CD4+ cell count. However, men who reported sex with men as their only risk factor for HIV acquisition were more likely to have had at least 1 HCV Ab test compared to men who reported sex with men plus IDU as a risk factor for HIV acquisition (P ≤ .01). Men who had a baseline HIV load >10 000 copies/mL were more likely to have had at least 1 HCV Ab test compared to those who had an undetectable HIV load (P = .01; data not shown).

Figure 1.

Study population of human immunodeficiency virus–infected men who receive primary care at Fenway Health. Abbreviations: HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; HCV Ab, hepatitis C virus antibody; MSM, men who have sex with men.

Among the 1059 men who had at least 1 HCV Ab test, 38 (4%) were found to have a positive HCV Ab result on initial testing, 26 (2%) were known to be HCV seropositive prior to entry into care, and 995 (94%) were found to have a negative HCV Ab result on initial testing. Among the 995 men with an initial negative HCV Ab result, 616 (62%) were not retested. In comparing the 616 men who only had 1 HCV Ab test with the 379 men who had ≥2 HCV Ab tests, there were no significant differences in race, risk factor for HIV acquisition, and initial CD4+ cell count (Table 1). However, men with an HIV load of up to 10 000 copies/mL were more likely to have >1 HCV Ab test compared with men who had an undetectable HIV load (P < .01).

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics of HIV-Infected Men in Care at Fenway Health by Number of Hepatitis C Virus Antibody Tests (n = 995)a

| Characteristic | Total No. (n = 995) |

Only 1 HCV Ab Test During Study Period (n = 616) |

>1 HCV Ab Test During Study Period (n = 379) |

P Value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, y, median (range) | 38 | (18–71) | 38 | (20–71) | 37 | (18–65) | .0012 |

| Race/ethnicity | |||||||

| White | 767/968 | (7) | 475/599 | (79) | 292/369 | (79) | .44 |

| Black | 66/968 | (79) | 36/599 | (6) | 30/369 | (8) | |

| Hispanic | 86/968 | (9) | 54/599 | (9) | 32/369 | (9) | |

| Other | 49/968 | (5) | 34/599 | (6) | 15/369 | (4) | |

| Self-reported risk factor for HIV acquisition | |||||||

| MSM only | 903/925 | (98) | 559/572 | (98) | 344/353 | (98) | .93 |

| MSM + IDU | 9/925 | (1) | 5/572 | (1) | 4/353 | (1) | |

| MSM + other | 13/925 | (1) | 8/572 | (1) | 5/353 | (1) | |

| CD4+ cell count at initial visit | |||||||

| <200 cells/mm3 | 175/995 | (18) | 104/616 | (17) | 71/379 | (19) | .73 |

| 200–499 cells/mm3 | 432/995 | (43) | 268/616 | (43) | 164/379 | (43) | |

| ≥500 cells/mm3 | 388/995 | (39) | 244/616 | (40) | 144/379 | (38) | |

| HIV RNA at initial visit | |||||||

| Undetectable | 259/916 | (28) | 173/573 | (30) | 86/343 | (25) | Ref |

| 0–10 000 copies/mL | 264/916 | (29) | 141/573 | (25) | 123/343 | (36) | .0018 |

| >10 000 copies/mL | 393/916 | (43) | 259/573 | (45) | 134/343 | (39) | .81 |

Data are presented as No. (%) unless otherwise specified.

Abbreviations: HCV Ab, hepatitis C virus antibody; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; IDU, injection drug use; MSM, men who have sex with men; Ref, reference group.

a Table excludes men with no HCV Ab tests (n = 101), men with prevalent HCV upon entry into care at Fenway Health (n = 64), and non-MSM (n = 9).

Of the 379 men who had 1 or more subsequent HCV Ab tests after an initial negative result, 255 were tested twice, 85 were tested 3 times, and 37 were tested ≥4 times over a maximum 12-year period. The median time between HCV Ab tests was comparable between men who seroconverted (2.5 years) and those who did not (2.8 years; P = .59). Among the 379 men with 2 or more HCV Ab tests, 27 were diagnosed with HIV infection after entry into care at Fenway Health. We excluded person-time from entry into care at Fenway Health until HIV diagnosis for these 27 men. Twenty-three (6%) of 379 men seroconverted to HCV Ab positive during 1408 person-years of follow-up, for an incidence of 1.63 per 100 person-years (95% confidence interval, .97–2.30).

Of the 23 men with incident HCV, the median baseline ALT (closest to the date of last negative HCV Ab result) prior to HCV Ab seroconversion was 29 IU/L (range, 10–95 IU/L) and the median peak ALT documented prior to HCV Ab seroconversion was 206 IU/L (range, 16–1124 IU/L).

The annual number of HCV Ab tests among men at Fenway Health increased from 40 tests in 1997 to 213 tests in 2009 (P < .01). Overall, the percentage of HCV Ab tests that were positive did not increase between 1997 and 2009, ranging from 3% to 8% (P = .57). However, among the 23 men with incident HCV, the number of cases diagnosed increased over time: 6 seroconverted from 2001 to 2004, 4 seroconverted in 2007, 5 seroconverted in 2008, and 8 seroconverted in 2009 (P < .01).

Among men with incident or prevalent HCV, 33% reported a history of IDU, 46% reported a history of NIDU, 16% reported no drug use, and substance use history was unknown for 5% (Table 2). Among noninjection-drug users, cocaine was the most commonly reported substance used. The majority of men had a history of at least 1 STI in addition to HIV. Men with incident HCV were younger (37 vs 44 years; P < .01) and a higher proportion had an STI history other than HIV compared to men with prevalent HCV (87% vs 64%; P = .04).

Table 2.

Characteristics of HIV-Infected Men Who Have Sex With Men With Hepatitis C Virus Antibody Positivity (n = 87)

| Characteristic | Total HCV Ab+ (n = 87) |

Prevalent HCV Ab+ (n = 64) |

Incident HCV Ab+ (n = 23) |

P Value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Agea, y, median (range) | 43 | (23–58) | 44 | (24–58) | 37 | (23–50) | .0001 |

| HIV durationa, y, median (range) | 5 | (−27 to 9) | 8 | (−27 to 8) | 1 | (−17 to 9) | .0014 |

| Race/ethnicity | |||||||

| White | 60 | (70) | 44 | (71) | 16 | (70) | .48d |

| Black | 9 | (11) | 8 | (13) | 1 | (4) | |

| Hispanic | 11 | (13) | 7 | (11) | 4 | (17) | |

| Other | 5 | (6) | 3 | (5) | 2 | (9) | |

| Self-reported risk factor for HIV acquisition | |||||||

| MSM only | 70 | (81) | 49 | (78) | 21 | (91) | .33e |

| MSM + IDU | 14 | (16) | 12 | (19) | 2 | (9) | |

| MSM + other | 2 | (2) | 2 | (3) | 0 | (0) | |

| Erectile enhancer useb | 32 | (37) | 24 | (38) | 8 | (35) | .82 |

| STI historyb | 61 | (70) | 41 | (64) | 20 | (87) | .04 |

| HPV warts | 41 | (47) | 28 | (44) | 13 | (57) | .29 |

| Syphilis | 25 | (29) | 15 | (23) | 10 | (43) | .07 |

| Herpes | 19 | (22) | 16 | (25) | 3 | (13) | .38 |

| Gonorrhea | 16 | (18) | 11 | (17) | 5 | (22) | .63 |

| Chlamydia | 7 | (8) | 6 | (6) | 3 | (13) | .37 |

| Drug use historyb | |||||||

| IDU + non-IDU | 29 | (33) | 20 | (31) | 9 | (39) | .23 |

| Non-IDU | 40 | (46) | 32 | (50) | 8 | (35) | |

| None | 14 | (16) | 8 | (12) | 6 | (26) | |

| Unknown | 4 | (5) | 4 | (6) | 0 | (0) | |

| Types of non-IDUc (n = 67) | |||||||

| Cocaine | 50 | (75) | 37 | (74) | 13 | (76) | |

| Marijuana | 39 | (58) | 28 | (56) | 11 | (65) | |

| Crystal meth | 32 | (48) | 25 | (50) | 7 | (41) | |

| Ecstasy | 10 | (15) | 7 | (14) | 3 | (18) | |

| Poppers | 5 | (7) | 4 | (8) | 1 | (6) | |

| Ketamine | 4 | (6) | 4 | (8) | 0 | (0) | |

| GHB | 4 | (6) | 2 | (4) | 2 | (12) | |

| Insurance statusa,f | |||||||

| Private | 36 | (43) | 22 | (36) | 14 | (64) | .08e |

| Medicaid | 15 | (18) | 12 | (20) | 3 | (14) | |

| Medicare | 27 | (33) | 23 | (38) | 4 | (18) | |

| Other | 5 | (6) | 4 | (7) | 1 | (5) | |

| HCV spontaneous clear | 22 | (26) | 15 | (23) | 7 | (30) | .53 |

| CD4+ cell count at initial visit | |||||||

| <200 cells/mm3 | 20 | (23) | 16 | (25) | 4 | (17) | .36 |

| 200–499 cells/mm3 | 31 | (36) | 20 | (31) | 11 | (48) | |

| ≥500 cells/mm3 | 36 | (41) | 48 | (44) | 8 | (35) | |

| HIV RNA at initial visit | |||||||

| Undetectable | 26 | (30) | 21 | (33) | 5 | (22) | .30 |

| 0–10 000 copies/mL | 27 | (31) | 17 | (26) | 10 | (43) | |

| >10 000 copies/mL | 34 | (39) | 26 | (41) | 8 | (35) | |

Data are presented as No. (%) unless otherwise specified.

Abbreviations: crystal meth, crystal methamphetamine; GHB, gamma-hydroxybutyric acid; HCV Ab, hepatitis C virus antibody; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; HPV, human papillomavirus; IDU, injection drug use; MSM, men who have sex with men; poppers, amyl nitrate; STI, sexually transmitted infection.

a Status at first visit to Fenway Health.

b History of exposure ever.

c Type on non-IDU.

d Race/ethnicity: black vs white vs Hispanic.

e HIV risk factor: MSM only vs MSM + IDU.

f Private insurance vs Medicare vs Medicaid.

Sixty-four (74%) men who were seropositive for HCV developed chronic HCV infection (Table 3). Of these, 47 had prevalent and 17 incident HCV infection. Among men who underwent HCV treatment, SVR rates were higher for those with incident HCV infection (6/7 [86%]) compared to those with prevalent HCV infection (7/15 [47%]; P = .02). Of 16 men with a known date of initial HCV diagnosis and HCV treatment start date, the median time from HCV diagnosis to treatment initiation was 14 months (range, 2–67 months); the median time was 6 months (range, 2–67 months) among 10 of 16 men who achieved SVR compared with 18 months (range, 14–35 months) among 6 of 16 men who did not achieve SVR (P = .33).

Table 3.

Characteristics of HIV-Infected Men Who Have Sex With Men With Chronic Hepatitis C Virus Infection (n = 64)

| Characteristic | Total HCV (n = 64) |

Prevalent HCV (n = 47) |

Incident HCV (n = 17) |

P Value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| High HCV RNA | 50 | (80) | 39 | (85) | 11 | (69) | .16 |

| HCV genotype | |||||||

| 1 | 40 | (63) | 29 | (62) | 11 | (65) | .73a |

| 2 | 11 | (17) | 9 | (19) | 2 | (12) | |

| 3 | 5 | (8) | 4 | (9) | 1 | (6) | |

| Unknown | 8 | (12) | 5 | (11) | 3 | (18) | |

| Off-site liver clinic referral | 54 | (84) | 41 | (87) | 13 | (76) | .29 |

| Appointment kept (n = 54) | 45 | (83) | 35 | (85) | 10 | (77) | .68 |

| Liver biopsy performed | 29 | (45) | 22 | (47) | 7 | (41) | .69 |

| Biopsy resultb (n = 26) | |||||||

| Stage 0 | 3 | (12) | 3 | (16) | 0 | 0 | >.99b |

| Stage 1 | 10 | (38) | 7 | (37) | 3 | 43 | |

| Stage 2 | 5 | (19) | 3 | (16) | 2 | 29 | |

| Stage 3 | 4 | (15) | 3 | (16) | 1 | (14) | |

| Stage 4 | 4 | (15) | 3 | (16) | 1 | 14 | |

| HCV therapy started | 22 | (34) | 15 | (32) | 7 | (41) | .49 |

| HCV therapy completed (n = 22) | 16 | (73) | 10 | (67) | 6 | (86) | |

| SVR achieved (n = 22) | 13 | (59) | 7 | (47) | 6 | (86) | .17 |

| Clinical evidence of cirrhosis | 7 | (11) | 5 | (11) | 2 | (12) | >.99 |

Data are presented as No. (%) unless otherwise specified.

Abbreviations: HCV, hepatitis C virus; SVR, sustained virologic response.

a HCV genotype 1 vs HCV genotype 2 or 3.

b Liver fibrosis stage 0 or 1 vs liver fibrosis stage 3 or 4 based upon Metavir scoring system [28].

Twenty-six men with chronic HCV infection underwent liver biopsy; 13 (50%) had stage 0–1, 5 (19%) had stage 2, and 8 (31%) had stage 3–4 liver fibrosis (Metavir scoring system). Among 16 of 47 men with prevalent HCV infection, the median time from HCV diagnosis to liver biopsy was 2.8 years (range, 0.1–11.3 years); among 7 of 17 men with incident HCV infection, the median time from HCV diagnosis to liver biopsy was 0.3 years (range, 0.2–4.5 years; P = .53).

Among 51 men with chronic HCV infection who did not initiate treatment or who were treated but did not achieve SVR, the median APRI score was 1.22 (range, 0.12–6.09); 22 (43%) had a score <0.5, 20 (39%) had a score between 0.5 and 1.5, and 9 (17.6%) had a score >1.5.

DISCUSSION

The annualized incidence of HCV among this sample of HIV-infected MSM engaged in primary care in Boston, Massachusetts, was 1.63 per 100 person-years. To our knowledge, this is the highest HCV incidence reported in the United States among HIV-infected MSM to date and suggests that incident HCV is common in this population. Studies from Europe and Australia have demonstrated a similarly high incidence of HCV among HIV-infected MSM [2, 3, 5, 7, 10, 23]. In a recent study that utilized data from 12 European cohorts, HCV incidence was found to increase over time from 0.09–0.22 per 100 person-years in 1990 to 2.34–5.11 per 100 person-years in 2007 [16]. Phylogenetic analyses of HIV-infected MSM with recent HCV acquisition from Europe and Australia suggest the presence of an international HCV transmission network [4]. Studies are ongoing to determine whether similar networks exist within the United States [24, 25].

Compared with HIV-infected MSM with prevalent HCV, those with incident HCV tended to be younger and to have a higher frequency of STIs other than HIV. Only one-third of HIV-infected MSM with either prevalent or incident HCV reported a history of IDU, while many more reported a history of only NIDU. These findings are consistent with other studies of acute or recently acquired HCV infection, in which the median age of HCV acquisition among HIV-infected MSM ranged from 35 to 40 years [4, 25]. Among HIV-infected MSM, factors that have been associated with sexually transmitted HCV include concurrent anogenital infections, unprotected receptive anal intercourse, group sex, and other traumatic sexual practices, as well as NIDU, particularly sex while high on methamphetamines [5, 8, 10, 11, 23, 25]. One-third of HCV-infected MSM in this study also used erectile-enhancing medications despite the younger age of the cohort. Nonmedical use of erectile-enhancing agents has been implicated in transmission of HIV and other STIs among MSM, and may be a marker of a riskier subset of patients in care [26]. Our findings support the growing body of evidence that the epidemiology of HCV infection may be changing among HIV-infected MSM in the United States. In the absence of IDU, high-risk sexual behaviors and NIDU appear to play an important role in transmission. Importantly, because patients and providers may be unaware of the risk of HCV transmission in the setting of these nontraditional risk factors [27, 28], early screening may be uncommon.

In this study, 9% of HIV-infected MSM did not have a documented HCV Ab test at any point in the study, and 62% had only an initial negative HCV Ab result with no subsequent testing despite long-term follow-up care at this clinic. This low rate of repeat HCV Ab testing may in part be due to healthcare provider perceptions that their patients are at low risk for HCV. Of the patients with incident HCV, many lacked documented evidence of a preceding rise in ALT or clinical exposure history to HCV, either of which might have prompted clinicians to order HCV Ab testing. Incident HCV infection may remain undiagnosed in this group of patients if risk-based testing or testing based on ALT rise alone is utilized. European guidelines since 2008 have recommended annual HCV screening among HIV-infected individuals with a negative HCV Ab result [29]. In contrast, US HIV primary care guidelines endorse HCV Ab screening at the time of HIV diagnosis but lack recommendations for repeated screening among individuals with a negative HCV Ab result [30]. Although baseline screening for HCV will diagnose infection acquired either prior to or at the time of HIV acquisition, HCV acquired after HIV infection is typically clinically silent [31], and may not be diagnosed until late in its clinical course without rescreening. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) now recommends routine ongoing HCV testing among HIV-infected MSM with high-risk sexual behaviors or concomitant ulcerative STIs [32]. The CDC also now recommends screening all Americans born between 1945 and 1965 (the “baby boomers”) [33].

In this study, 59% of HIV-infected MSM with chronic HCV infection who underwent treatment achieved SVR, despite a high prevalence of genotype 1 infection and elevated baseline HCV RNA. This SVR rate is higher than previously reported among HIV-infected persons with chronic HCV [34] and may in part be explained by an earlier stage of fibrosis at the time of treatment. A shorter duration of HCV infection at the time of treatment and higher treatment completion rates may also have contributed to the high SVR rate. In addition, much of the earlier data on HCV treatment response rates in HIV/HCV-coinfected individuals involved patients who were older and of African American ancestry [35, 36]. The high SVR rate observed may reflect more optimal HCV treatment responses with interferon-based treatment among patients who are younger and white. Finally, provider experience at Fenway Health and the coinfection-specific referral center may have contributed to increased HCV treatment rates and improved outcomes [37, 38]. Given that the addition of the HCV protease inhibitors improves SVR rates in patients with genotype 1 infection [39], earlier recognition and treatment of HCV infection may greatly improve outcomes.

Several study limitations should be noted. Data collection was based upon retrospective chart review and may not have captured risk factor data that was undocumented by providers. Data on alcohol use were not systematically documented and was not included in this analysis. Data on IDU and NIDU was based upon patient self-report and may have underestimated the true prevalence of substance use as well as the contribution of substance use to HCV acquisition in this population. However, audio computer–assisted interview methods are employed at Fenway Health to collect behavioral data [40, 41] and have been shown to be effective in increasing the reporting of risky or undesirable behaviors. Although 96% of HIV-infected men at Fenway Health identify as MSM, current sexual behavior data were not available for all individuals. While all 87 men with HCV were MSM, some non-MSM patients may have been included in the denominator, which included all male HIV-infected patients in care, suggesting that annualized HCV incidence might actually be higher for HIV-infected MSM. Nine percent of patients at Fenway Health did not receive an HCV Ab test, and the remaining patients had variable HCV Ab testing over the study period, with the majority of patients undergoing a single negative screening test. Thus, we may have underestimated true HCV Ab prevalence and incidence among HIV-infected MSM at Fenway Health. Given that data were retrospectively collected, we were unable to determine whether patients with incident HCV had recent acute vs chronic HCV infection; thus, some patients may have been misclassified. Finally, although we included data on baseline CD4+ cell count and HIV load in our analyses, we were unable to assess the association between antiretroviral therapy use and HCV Ab testing, disease progression, and treatment outcomes.

In the United States and other regions where HIV-infected individuals have access to highly active antiretroviral therapy, HCV is a leading cause of non-AIDS-related mortality [42] Increasing evidence supports a high prevalence and incidence of HCV infection among HIV-infected MSM. To reduce the morbidity and mortality associated with chronic HIV/HCV coinfection, HIV-infected MSM should receive annual HCV Ab screening to diagnose and treat infection at earlier stages; higher-risk patients should be screened more often [43]. Furthermore, HIV-infected MSM who use recreational drugs and/or engage in unprotected sex should receive education and services related to sexual risk reduction, be offered counseling and treatment for substance use and addiction, and be made aware of nonclassic risk factors for HCV. Such preventive interventions are crucial to stemming the ongoing spread of HCV.

Notes

Acknowledgments. The authors thank the patients and providers at Fenway Health.

Disclaimer. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute on Drug Abuse, the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, or the National Institutes of Health.

Financial support. This work was supported by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (5T32AI007438-17 to S. G.; P30AI042853) to support the Lifespan/Tufts/Brown Center for AIDS Research, and the National Institute on Drug Abuse (K23DA020383 to L. E. T.).

Potential conflicts of interest. All authors: No reported conflicts.

All authors have submitted the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest. Conflicts that the editors consider relevant to the content of the manuscript have been disclosed.

References

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Recommendations for prevention and control of hepatitis C infection and HCV-related chronic disease. MMWR Recomm Rep. 1998;47(RR19):1–39. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.van de Laar TJ, Matthews GV, Prins M, et al. Acute hepatitis C in HIV-infected men who have sex with men: an emerging sexually transmitted infection. AIDS. 2010;24:1799–812. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32833c11a5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Urbanus AT, van der Laar TJ, Stolte IG, et al. Hepatitis C virus infection among HIV-infected men who have sex with men: an expanding epidemic. AIDS. 2009;23:F1–7. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32832e5631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.van der Laar T, Pybus O, Bruisten S, et al. Evidence of a large, international network of HCV transmission in HIV-positive men who have sex with men. Gastroenterology. 2009;136:1609–17. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2009.02.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bottieau E, Apers L, Van Esbroeck M, et al. Hepatitis C virus infection in HIV-infected men who have sex with men: sustained rising incidence in Antwerp, Belgium, 2001–2009. Euro Surveill. 2010;15:19673. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fierer DS, Uriel AJ, Carriero DC, et al. Liver fibrosis during an outbreak of acute hepatitis C virus infection in HIV-infected men: a prospective cohort study. J Infect Dis. 2008;198:683–6. doi: 10.1086/590430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Giraudon I, Ruf M, Maguire H, et al. Increase in diagnosed newly acquired hepatitis C in HIV-positive men who have sex with men across London and Brighton, 2002–2006: is this an outbreak? Sex Transm Infect. 2008;84:111–5. doi: 10.1136/sti.2007.027334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Danta M, Brown D, Bhagani S, et al. Recent epidemic of acute hepatitis C virus in HIV- positive men who have sex with men linked to high risk sexual behaviors. AIDS. 2007;11:983–91. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e3281053a0c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rauch A, Rickenbach M, Weber R, et al. Unsafe sex and increased incidence of hepatitis C infection among HIV-infected men who have sex with men: the Swiss HIV Cohort Study. Clin Infect Dis. 2005;41:395–402. doi: 10.1086/431486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gambotti L, Batisse D, Colin-de-Verdiere N, et al. Acute hepatitis C infection in HIV positive men who have sex with men in Paris, France, 2001–2004. Euro Surveill. 2005;10:115–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Larsen C, Chaix ML, Le Strat Y, et al. Gaining greater insight into HCV emergence in HIV-infected men who have sex with men: the HEPAIG Study. PLoS One. 2011;6:e29322. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0029322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Marcias J, Palacios RB, Claro E, et al. High prevalence of hepatitis C virus infection among noninjection drug users: associations with sharing the inhalation implements of crack. Liver Int. 2008;28:781–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1478-3231.2008.01688.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schmidt AJ, Rockstroh JK, Vogel M, et al. Trouble with bleeding: risk factors for acute hepatitis C among HIV-positive gay men from Germany—a case-control study. PLoS One. 2011;6:1–9. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0017781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Taylor LE, Holubar M, Wu K, et al. Incident hepatitis C virus infection among US HIV-infected men enrolled in clinical trials. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;52:812–8. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciq201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Raymond HF, Hughes A, O'Keefe K, et al. Hepatitis C prevalence among HIV-positive MSM in San Francisco: 2004 and 2008. Sex Transm Dis. 2011;38:219–20. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e3181f68ed4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.van der Helm JJ, Prins M, Del Amo J, Bucher HC, et al. The hepatitis C epidemic among HIV-positive MSM: incidence estimates from 1990 to 2007. AIDS. 2011;15:1083–91. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e3283471cce. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wandeler G, Gsponer T, Bregenzer A, et al. Hepatitis C virus infections in the Swiss HIV Cohort Study: a rapidly evolving epidemic. Clin Infect Dis. 2012;55:1408–16. doi: 10.1093/cid/cis694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hoover KW, Butler M, Workowski KA, et al. Low rates of hepatitis screening and vaccination of HIV-infected MSM in HIV clinics. Sex Transm Dis. 2012;39:349–53. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e318244a923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Johnson CV, Mimiaga MJ, Reisner SL, et al. Health care access and sexually transmitted infection screening frequency among at-risk Massachusetts men who have sex with men. Am J Public Health. 2009;99:S187–92. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2007.127464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wai CT, Greenson JK, Fontana RJ, et al. A simple nonvasive index can predict both significant fibrosis and cirrhosis in patients with chronic hepatitis C. Hepatology. 2003;38:518–26. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2003.50346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tassiopoulos KK, Seage G, Sam N, et al. Predictors of herpes simplex virus type 2 prevalence and incidence among bar and hotel workers in Moshi, Tanzania. J Infect Dis. 2007;195:493–501. doi: 10.1086/510537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hanson JH, Posner SP, Hassig S, et al. Assessment of sexually transmitted diseases as risk factors for HIV seroconversion in a New Orleans sexually transmitted disease clinic, 1990–1998. Ann Epidemiol. 2005;15:13–20. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2004.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gamage DG, Read TR, Bradshaw CS, et al. Incidence of hepatitis-C among HIV infected men who have sex with men (MSM) attending a sexual health service: a cohort study. BMC Infect Dis. 2011;11:39. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-11-39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fierer D, Khudyakov Y, Hare B, et al. Molecular epidemiology of incident HCV infection in HIV-infected MSM in the US versus infections in Europe and Australia. 2011 18th Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections, Boston, MA, 27 February–2 March Session 34. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Sexual transmission of hepatitis C virus among HIV-infected men who have sex with men—New York City, 2005–2010. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2011;60:945–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Spindler HH, Scheer S, Chen SY, et al. Viagra, methamphetamines, and HIV risk: results from a probability sample of MSM, San Francisco. Sex Transm Dis. 2007;34:586–91. doi: 10.1097/01.olq.0000258339.17325.93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Taylor LE, Delong AK, Maynard MA, et al. Acute hepatitis C in an HIV clinic: a screening strategy, risk factors, and perception of risk. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2011;25:571–7. doi: 10.1089/apc.2011.0106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.De Ryck I, Berghe VW, Antonneau C, Colebunders R. Awareness of hepatitis C infection among men who have sex with men in Flanders, Belgium. Acta Clin Belg. 2011;66:46–8. doi: 10.2143/ACB.66.1.2062513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.The European AIDS Treatment Network (NEAT) Acute Hepatitis C Consensus Panel. Acute Hepatitis C in HIV-infected individuals: recommendations from the European AIDS Treatment Network (NEAT) Consensus Conference. AIDS. 2011;25:399–409. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e328343443b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Aberg JA, Kaplan JE, Libman H, et al. Primary care guidelines for the management of persons infected with HIV: 2009 update by the HIV Medicine Association of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2009;49:651–81. doi: 10.1086/605292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Alberti A, Noventa F, Benvegnu L, et al. Prevalence of liver disease in a population of asymptomatic persons with hepatitis C virus infection. Ann Intern Med. 2002;137:961–4. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-137-12-200212170-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Workowski KA, Berman S. Sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines, 2010. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2010;59(RR12):1–110. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Recommendations for the identification of chronic hepatitis C virus infection among persons born during 1945–1965. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2012;61(RR-4):1–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shire NJ, Welge JA, Sherman KE. Response rates to pegylated interferon and ribavirin in HCV/HIV coinfection: a research synthesis. J Viral Hepat. 2007;14:239–48. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2893.2006.00824.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Conjeevaram HS, Fried MW, Jeffers LJ, et al. Peginterferon and ribavirin treatment in African American and Caucasian American patients with hepatitis C genotype 1. Gastroenterology. 2006;131:470–7. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2006.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mehta SH, Lucas GM, Mirel LB, Torbenson M, Higgins Y, Moore RD, Thomas DL, Sulkowski MS. Limited effectiveness of antiviral treatment for hepatitis C in an urban HIV clinic. AIDS. 2006;20:2361–9. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32801086da. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kanwal F, Hoang T, Spiegel BM, Eisen S, Dominitz JA, Gifford A, Goetz M, Asch SM. Predictors of treatment in patients with chronic hepatitis C infection—role of patient versus nonpatient factors. Hepatology. 2007;46:1741–9. doi: 10.1002/hep.21927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rackal JM, Tynan AM, Handford CD, Rzeznikiewz D, Agha A, Glazier R. Provider training and experience for people living with HIV/AIDS. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;6:CD003938. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003938.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jacobson IM, McHutchison JG, Dusheiko G, et al. ADVANCE Study Team. Telaprevir for previously untreated chronic hepatitis C virus infection. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:2405–16. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1012912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mayer K, O'Cleirigh C, Skeer M, et al. Which HIV-infected men who have sex with men in care are engaging in risky sex and acquiring sexually transmitted infections: findings from a Boston community health centre. Sex Transm Infect. 2010;86:66–70. doi: 10.1136/sti.2009.036608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Skeer MR, Mimiaga MJ, Mayer KH, et al. Patterns of substance use among a large urban cohort of HIV-infected men who have sex with men in primary care. AIDS Behav. 2012;16:676–89. doi: 10.1007/s10461-011-9880-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Weber R, Friis-Moller N, Sabin CA, et al. Liver-related deaths among HIV-infected persons: data from the D:A:D study. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166:1632–41. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.15.1632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Taylor LE, Swan T, Mayer KH. HIV coinfection with hepatitis C virus: evolving epidemiology and treatment paradigms. Clin Infect Dis. 2012;55(suppl 1):33–42. doi: 10.1093/cid/cis367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]