Abstract

This paper summarises a research program on the new immigrant second generation initiated in the early 1990s and completed in 2006. The four field waves of the Children of Immigrants Longitudinal Study (CILS) are described and the main theoretical models emerging from it are presented and graphically summarised. After considering critical views of this theory, we present the most recent results from this longitudinal research program in the forum of quantitative models predicting downward assimilation in early adulthood and qualitative interviews identifying ways to escape it by disadvantaged children of immigrants. Quantitative results strongly support the predicted effects of exogenous variables identified by segmented assimilation theory and identify the intervening factors during adolescence that mediate their influence on adult outcomes. Qualitative evidence gathered during the last stage of the study points to three factors that can lead to exceptional educational achievement among disadvantaged youths. All three indicate the positive influence of selective acculturation. Implications of these findings for theory and policy are discussed.

Keywords: segmented assimilation, selective acculturation, significant others, cultural capital, second generation

Introduction

Back in 1990 when Rubén Rumbaut and Alejandro Portes launched a longitudinal study of the second generation, the field of immigration studies in American social science was still not very popular and the bulk of it concentrated on adult immigrants, particularly the undocumented. The reason that led us to turn attention to the children was the realization that the long-term effects of immigration on American society would be determined less by the first than by the second generation and that the prognosis for this outcome was not as rosy as the dominant theories of the time would lead us to believe. First generation immigrants have always been a flighty bunch, here today and gone tomorrow, in the society, but not yet of it. By contrast, their U.S.-born and reared children are, overwhelmingly, here to stay and, as citizens, fully entitled to ‘voice’ in the American political system (in Hirschman’s [1970] sense of the term). Hence, the course of their adaptation will determine, to a greater extent than other factors, the long-term destiny of the ethnic groups spawned by today’s immigration.

In a prescient article, Gans (1992) argued that the future of children of immigrants growing up at present in America might not be as straightforward as the optimistic conclusions derived from the then-dominant assimilation perspective. Gans noted that many immigrants came from modest class backgrounds, bringing very scarce human capital that did not equip them to steer their offspring around the complexities of the American educational system. In an increasingly knowledge-based economy, children of immigrants without an advanced education would not be able to access the jobs that provided them with a ticket to the upper-middle classes and may stagnate into manual, low-wage work not too different from that performed by their parents. Those unwilling to do so because of heightened American-style aspirations would live frustrated lives or, more poignantly, would be tempted to join the gangs and drug culture ravaging American inner cities.

Portes and Rumbaut had just completed the first edition of Immigrant America: A Portrait (1990) and it became clear that Gans was on to something: the condition of today’s children of immigrants stood in need of serious scrutiny. Accordingly, we decided to launch an empirical study of the question on the basis of a large sample of second generation students in the school systems of two of the main metropolitan areas of immigrant concentration –Miami/Ft. Lauderdale and San Diego. In 1992, Portes and Zhou published a theoretical article that sought to bring together Gans’ premonitions with what we had learned so far from our preliminary studies.

The argument was that the imagery of a uniform assimilation path did not do justice to what was taking place on the ground. Instead, the process had become segmented into several distinct paths, some leading upwards but others downward. These alternative outcomes reflect the barriers to adaptation encountered by second generation youths in today’s America and the social and economic resources to confront them that they and their families possess (Portes and Zhou 1992).

By 1996, the first survey of the Children of Immigrants’ Longitudinal Study (CILS) was completed and analyzed and Rumbaut and Portes could present the results, along with a more refined version of the segmented assimilation model, in the second edition of Immigrant America, published in the same year. Simultaneously, these two authors were completing the second follow-up survey of CILS, together with a survey of our respondents’ parents. Results of the full study appeared in a set of two volumes, Legacies: The Story of the Immigrant Second Generation (Portes and Rumbaut 2001) and Ethnicities: Children of Immigrants in America (Rumbaut and Portes 2001). The following section summarises the revised theoretical model advanced in these books as background for the presentation of the most recent findings based on the same study.

Segmented Assimilation: The Model

The theory of segmented assimilation consists of three parts: a) an identification of the major exogenous factors at play; b) a description of the principal barriers confronting today’s children of immigrants; c) a prediction of the distinct paths expected from the interplay of these forces. Exogenous factors can be conceptualised as the principal resources (or lack thereof) that immigrant families bring to the confrontation with the external challenges confronting their children. These factors are: 1) the human capital that immigrant parents possess; 2) the social context that receives them in America; and 3) the composition of the immigrant family. Human capital, operationally defined by formal education and occupational skills, translates into competitiveness in the host labor market and the potential for achieving desirable positions in the American hierarchies of status and wealth. The transformation of this potential into reality depends, however, on the context into which immigrants are incorporated. A receptive or at least neutral reception by government authorities; a sympathetic or at least not hostile reception by the native population; and the existence of social networks with a well-established and prosperous co-ethnic community pave the ground for the possibility of putting to use whatever credentials and skills have been brought from abroad.

Conversely, a hostile reception by authorities and the public and a weak or non-existent co-ethnic community handicaps immigrants and makes it difficult for them to translate their human capital into commensurate occupations or to acquire new occupational skills. Modes of incorporation is the concept used in the literature to refer to these tripartite (government/society/community) differences in the contexts that receive newcomers (Portes and Rumbaut 2001; Haller and Landolt 2005). Lastly, the composition of the immigrant family has also proven to be highly significant in determining second generation outcomes. Parents who stay together, extended families where grandparents and older siblings play a role at motivating and controlling adolescents have a significant role in promoting upward assimilation. Conversely, broken families, where a single parent struggles with conflicting demands leaving children to their own devices, have exactly the opposite effect (Zhou and Bankston 1998; Kasinitz et. al. 2001; Portes and Rumbaut 2001).

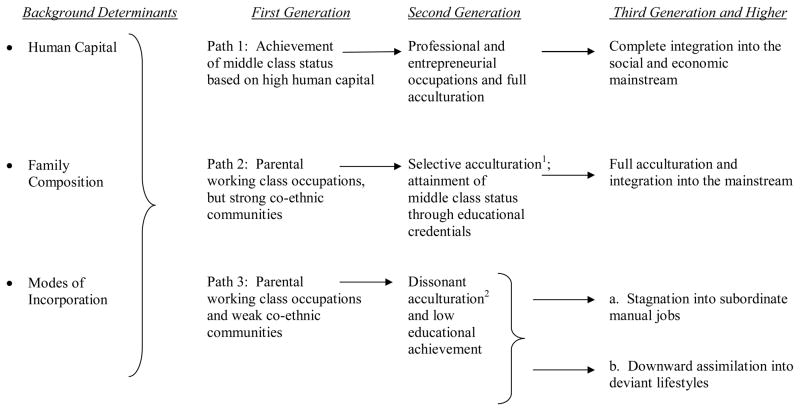

Figure 1 graphically summarises this discussion, outlining both the discrete adaptation paths and the key determinants of segmented assimilation. Contrary to some misinterpretations of the model (to be discussed below), the figure makes clear that several distinct paths of adaptation exist, including upward assimilation grounded on parental human or social capital, stagnation into working-class menial jobs, and downward assimilation into poverty, unemployment, and deviant lifestyles. The latter two options are more common among offspring of poor and poorly-received migrants, including, in particular, those who arrived without legal status.

Figure 1. Paths of Mobility across Generations: A Model.

1Defined as preservation of parental language and elements of parental culture along with acquisition of English and American ways.

2Defined as rejection of parental culture and breakdown of communication across generations.

The barriers that confront children of immigrants can also be summarised as racism, bifurcated labor markets, and the existence of alternative deviant lifestyles grounded on gangs and the drug trade. By American standards, the majority of today’s second generation is non-white, being formed by children of mestizo, black, and Asian parents whose physical features differentiate them from the dominant white American majority. Social scientists know that race and racial features have no intrinsic significance. Their meaning is assigned to them in the course of social interaction. In such a racially-sensitive environment as that of American society, physical features are assigned major importance. They then go on to affect, sometimes determine, the life chances of young people. Children of black and mulatto parents find themselves particularly disadvantaged because of the character of the American racial hierarchy (Geschwender 1978; Wilson 1987; Massey and Denton 1993).

With the onset of massive de-industrialization and the advent of a service-based economy, the U.S. labor market has become progressively bifurcated into a top-tier of knowledge-based occupations requiring computer literacy and advanced education and a bottom tier of manual occupation requiring little more than physical strength. This bifurcation spells the end of the previous pyramidal structure of unskilled, semi-skilled, and skilled industrial occupations that served so well to promote the inter-generational mobility of earlier European immigrants and their descendants (Bluestone and Harrison 1982; Wilson 1987; Loury 1981).

The new ‘hourglass’ labor market created has been accompanied by growing economic inequality, transforming the United States from a relatively egalitarian society to one where income and wealth disparities have come to approach Third World levels. For new entrants into the labor force, including children of immigrants, this stark bifurcation means that they must acquire in the course of a single generation the advanced educational credentials that took descendants of Europeans several generations to achieve. Otherwise, their chances to fulfill their life’s aspirations would be compromised, as few opportunities exist between the low-paid manual occupations that most immigrant parents occupy and the lofty, highly-paid jobs in business, health, the law and the academy that these parents earnestly wish for their offspring. Without the costly and time-consuming achievement of a university degree, such dreams are likely to remain beyond reach (Hirschman 2001; Massey and Hirst 1998).

Failure to move ahead educationally and occupationally in the second generation carries an added risk. Under ‘normal’ circumstances, youths who cannot navigate the educational system could simply move laterally, entering jobs comparable to those occupied by their parents. Inter-generational lack of mobility and second generation stagnation into working-class occupations actually happens and may well be the normative path for the offspring of immigrants disadvantaged by low parental human capital and a negative mode of incorporation (Perlman 2004; Lopez and Stanton-Salazar 2001; Rumbaut 1994; 2005).

An even less desirable alternative befalls youths who, dissatisfied with the prospect of toiling at low-wage, dead-end jobs all their lives, look toward alternatives readily provided by deviant activities and organised gangs. Students attending poor inner-city schools are regularly exposed to these alternatives that convey the lure of quick profits and a ‘cool’ lifestyle, bypassing the white-dominated mainstream mobility channels. This illusion quickly translates, for most, into a life of violence, drug use, jail sentences, and even premature death (Vigil 2002). This path has been labeled downward assimilation because the learning and introjection of American cultural ways do not lead for these youths into upward mobility but precisely the opposite (Fernández-Kelly and Konczal 2005).

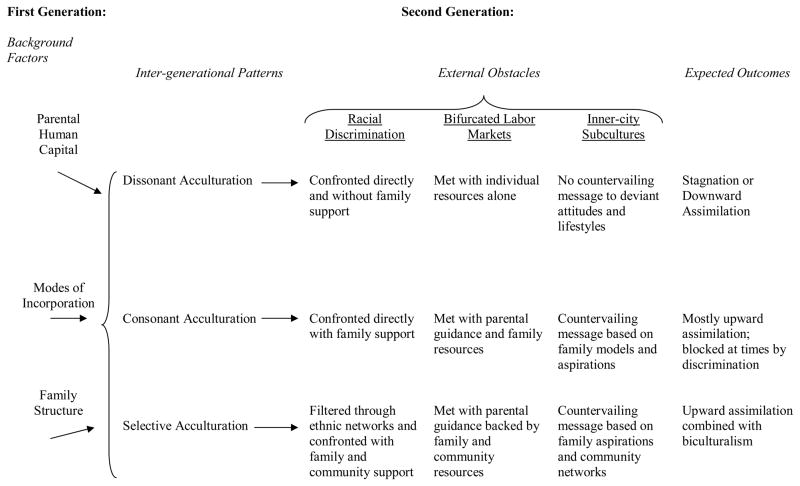

The interaction among exogenous factors influencing second-generation adaptation and the barriers posed by racism, bifurcated labor markets, youth gangs and the drug trade do not translate in a straightforward fashion into the distinct adaptation paths portrayed in Figure 1. Instead, there are a series of intervening outcomes reflected in the different pace of acculturation across generations. The children of professionals and other high human capital immigrants frequently undergo a process of consonant acculturation where parents and children jointly learn and accommodate to the language and culture of the host society. Others from similar backgrounds or with lower levels of human capital, but ensconced in strong co-ethnic communities undergo selective acculturation, where learning of English and American ways takes place simultaneously with preservation of key elements of the parental culture. Fluent bilingualism in the second generation is a good indicator of this eclectic path (Portes and Hao 2002).

Alternatively, youths from working-class migrant families that lack strong community supports may experience dissonant acculturation where introjection of the values and language of the host society is accompanied by rejection of those brought and associated with their parents. To the extent that parents remain foreign-language monolinguals, dissonant acculturation leads to rupture of family communications, as children reject use of a non-English language and, more importantly, reject parental ways that they have come to regard as inferior and even embarrassing (Portes and Hao 2002; Zhou and Bankston 1996, 1998).

While dissonant acculturation does not necessarily produce downward assimilation, it makes this outcome more probable because the breakdown in family communications leads to parental loss of control and, consequently, the inability of families to guide and control their offspring. Conversely, consonant and, especially, selective acculturation are associated with positive outcomes because youths learn to appreciate and respect the culture of parents and because command of another language gives them a superior cognitive vantage point, as well as a valuable economic tool (Peal and Lambert 1962; Portes and Hao 2002). Figure 2 presents an alternative and more refined model of segmented assimilation that incorporates these intervening generational outcomes.

Figure 2.

The Process of Segmented Assimilation: A Model

Critiques

The segmented assimilation model has not been without its critics. In particular, two authors, Perlmann and Waldinger, have taken issue with the model by arguing, first, that the situation and challenges confronting children of immigrants today are not too different from those experienced by offspring of earlier European immigrants and, hence, that a reconceptualization of the process is unnecessary (Waldinger and Perlmann 1998). Second, that there is little evidence of second generation stagnation or downward assimilation among contemporary children of immigrants.

To bolster these points, these authors have undertaken a series of empirical studies. Perlmann (2005) compared the assimilation process of Italian immigrants and their descendants at the beginning of the twentieth century and Mexicans at the end. Waldinger and his associates (2007) analyzed the labor market performance of Mexican-American youths, the largest second-generation group in the United States and one deemed at significant risk of downward assimilation. Ultimately, results of these studies turn out to be generally compatible with the segmented assimilation model and to support its principal tenets. Perlmann’s study shows that the comparison between ‘Italians then, Mexicans now’ is strained by the very different historical contexts faced by each group. Whatever the disadvantages that they confronted, and there were many, Italian immigrants never faced the generalised stigma and insecurity of illegal status. Further, they arrived to meet the labor needs of an expanding industrial economy which offered, to them and their offspring, multiple opportunities for advancement. These opportunities did not depend on achievement of a college education since they occurred in skilled industrial trades.

In one striking chart, Perlmann attempts to estimate the ethnic wage disadvantage due to education of South/Central Europeans and Mexicans relative to native whites by multiplying the average standardised gap of education for both immigrant groups by the wage returns to education in 1950 (for the children of Europeans) and 2000 (for the children of Mexicans). The analysis finds that Mexican-Americans are doubly handicapped, both by their lower educational achievement and by the much higher returns to education at the present time. Hence, the ‘Mexican [second generation] brings their great handicap in educational profile into the labor market in the worst possible context, when the returns to education are higher than at any point from 1940 to 2000’ (Perlmann 2005:55).

In the end, this author finds that contemporary high school dropout rate among Mexican-Americans are so far higher than among native whites and even native blacks as to prompt serious concern for the future: ‘Mexican-American dropout rates should bring to mind the warnings of the segmented assimilation hypothesis: that an important part of the contemporary second generation will assimilate downwards’ (Perlmann 2005: 82–83).

In fact, the theory asserts that downward assimilation into underclass-like conditions is just one possible outcomes of the process and that an alternative, indeed more common result among the offspring of disadvantaged labor immigrants is stagnation into the working-class (see Figure 1). This is actually the principal result emerging from Waldinger et. al.’s (2007) analysis. They find that, while most Mexican-American youths work for a living, their occupations are overwhelmingly modest and low-paying, not too different from those held by their parents. That result accords with the low average levels of educational achievement among this group detected in Perlmann’s analysis. In the end, the vigorous initial critique of the segmented assimilation model by these authors turns out to be quibbles at the margin, for their own evidence supports its principal tenets.

The possibility that a significant minority of the contemporary second generation experiences downward assimilation – signaled by such events as school abandonment, unemployment, teenage childbearing, and arrest and incarceration – is more than of purely academic interest. Given the size of this population, even a minority experiencing these outcomes will have a significant impact in the cities and regions where it concentrates. The following sections present evidence from the third and last wave of CILS that bears directly on this question and, by the same token, puts the original model to a more rigorous empirical test. The segmented assimilation model predicts two basic things: first, that downward assimilation, as indexed by the above series of outcomes, exists and affects a sizable number of second generation youths; second, that incidents of downward or, for that matter, upward assimilation are not random but are patterned by the set of exogenous causal determinants identified by the model. We present results bearing on both issues.

Findings

a. Adaptation Outcomes by Nationality

In 2002, the third and final CILS survey was conducted. By this time, the average age of the sample was 24. Hence, adaptation outcomes measured in this survey are ‘hard’ in the sense of gauging objective events in the lives of young persons – from level of education completed to incidents of arrest and incarceration. It is thus possible with these data to test the predictions advanced by the segmented assimilation model, as well as its overall structure. The survey retrieved a total of 3,564 cases, approximately 85 percent of the preceding one and close to 70 percent of original respondents. There is evidence of bias in the final follow-up which underrepresented youths from lower SES families and who grew up without both biological parents present. It is possible, however, to adjust for this source of bias by applying a correction for selectivity on the basis of data from the original survey. The following results have been corrected accordingly.

The existence of downward assimilation in the second generation can be equated with the series of outcomes outlined previously: school abandonment, unemployment, poverty, early childbearing, and incidents of arrest and incarceration. CILS-III contains indicators of all these outcomes. Table 1 and 2, which refer respectively to the first and second generation, present the results broken down by nationality. The nine national groups identified in the table are representative of over 80 percent of the contemporary immigrant population of the United States. Smaller nationalities are grouped in the ‘other Latin,’ ‘other Asian,’ and ‘other’ categories.1

Table 1.

Characteristics and Adaptation Outcomes of First-Generations Immigrants

| Nationality | First Generation | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Percent Less than High Schoo11 | Percent College Graduates1 | Modes of Incorporation2 | Annual Average Incomes3 | Percent in Professional/Executive Occupations | Percent Stable Families4 | |

| Chinese | 4.4 | 64.3 | Neutral | 58627 | 47.9 | 76.7 |

| Cuban | 38.3 | 19.4 | Positive | 48266 | 23.3 | 58.8 |

| Filipino | 12.0 | 44.8 | Neutral | 49007 | 28.5 | 79.4 |

| Haitian | 35.5 | 12.6 | Negative | 16394 | - | 44.9 |

| Jamaican/West Indian | 20.7 | 18.0 | Negative | 39102 | 24.7 | 43.4 |

| Laotian/Cambodian | 45.3 | 12.3 | Positive | 25696 | 14.7 | 70.8 |

| Mexican | 69.8 | 3.7 | Negative | 22442 | 5.1 | 59.5 |

| Nicaraguan | 39.6 | 14.1 | Negative | 32376 | 7.2 | 62.8 |

| Vietnamese | 30.8 | 15.3 | Positive | 26822 | 12.9 | 73.5 |

For persons 16 years or older.

Modes of incorporation are defined as follows: Positive: Refugees and asylees receiving government resettlement assistance. Neutral: Non-black immigrants admitted for legal permanent residence. Negative: Black immigrants and those nationalities with large proportions of unauthorised entrants.

Family incomes.

Children living with both biological parents.

Sources: Current Population Surveys and Parental Survey of the Children of Immigrants Longitudinal Study (CILS). Originally published in Portes and Rumbaut, 2006, p. 25l

Table 2.

Characteristics and Adaptation Outcomes of Second-generation Immigrants

| Nationality | Education | Family Income | Unemployed5 | Has had Children | Incarcerated | N | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Average Years | High School or Less % | Mean $ | Median $ | % | % | Total % | Males % | ||

| Chinese | 15.4 | 5.7 | 57,583 | 33,611 | 2.9 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 35 |

| Cuban (Private School) | 15.32 | 7.5 | 104,767 | 70,395 | 3.0 | 3.0 | 2.9 | 3.4 | 133 |

| Cuban (Public School) | 14.32 | 21.7 | 60,816 | 48,598 | 6.2 | 17.7 | 5.6 | 10.5 | 670 |

| Filipino | 14.5 | 15.5 | 64,442 | 55,323 | 7.8 | 19.4 | 3.9 | 6.8 | 586 |

| Haitian | 14.44 | 15.3 | 34,506 | 26,974 | 16.7 | 24.2 | 7.1 | 14.3 | 95 |

| Jamaican/West Indian | 14.63 | 18.1 | 40,654 | 30,326 | 9.4 | 24.3 | 8.5 | 20.0 | 148 |

| Laotian/Cambodian | 13.3 | 45.9 | 34,615 | 25,179 | 9.3 | 25.4 | 4.3 | 9.5 | 186 |

| Mexican | 13.4 | 38.0 | 38,254 | 32,585 | 7.3 | 41.5 | 10.8 | 20.2 | 408 |

| Nicaraguan | 14.17 | 26.4 | 54,049 | 47,054 | 4.9 | 20.1 | 4.4 | 9.9 | 222 |

| Vietnamese | 14.9 | 12.6 | 44,717 | 34,868 | 13.9 | 9.0 | 7.8 | 14.6 | 194 |

| Other (Asian) | 15.2 | 9.1 | 58,659 | 40,278 | 4.5 | 11.4 | 6.7 | 9.5 | 46 |

| Other (Latin) | 14.4 | 25.5 | 43,476 | 31,500 | 2.2 | 15.2 | 6.4 | 18.8 | 47 |

| Other | 14.55 | 20.8 | 59,719 | 40,619 | 7.3 | 16.4 | 4.9 | 8.3 | 404 |

Respondents without jobs, whether looking or not looking for employment, except those still enrolled at school. Source: Children of Immigrants Longitudinal Study (CILS), third survey, 2002–03. Results corrected for third-wave sample attrition.

There are good reasons to present these results tabulated by national origin. Immigrant groups differ markedly in the three exogenous factors identified by the model – human capital, family composition, and modes of incorporation. For illustration, the first columns of Table 1 present data on the average education, occupation, family structure, and contexts of reception of all nine immigrant groups. The marked differences between first generation Chinese, Filipinos, and Cubans, on the one hand, and Mexicans, Haitians, West Indians, and Laotian/Cambodians, on the other, provide the necessary background for the analysis of second generation results in Table 2.

These differences in the human capital and modes of incorporation in the first generation go on to affect the second. Table 2 divides the large Cuban-American sample according to whether respondents attended public schools or the private bilingual schools set up by Cuban exiles arriving in the 1960s and 1970s. Private school Cuban-Americans are mostly the children of these early upper-and middle-class arrivals. Their public-school counterparts are mostly the offspring of refugees who arrived during the chaotic 1980 Mariel exodus or afterwards, whose levels of human capital were significantly lower and who experienced a much more negative context of reception in the United States. Of all major immigrant groups arriving in the United States after 1960, Cubans are the only one to have gone from a positive to a negative mode of incorporation, marked by the Mariel exodus and its aftermath (Perez 2001; Portes and Stepick 1993).

Variations in school dropout rates or quitting study after attaining only a high school diploma are significant. In South Florida, youths who failed to pursue their studies beyond this level range from a low of 7.5 percent among middle-class Cubans to a high of 26 percent among Nicaraguans. Public school Cuban-Americans do much worse in this dimension than their private school compatriots. In Southern California, Chinese and other Asians have extraordinary levels of educational achievement; in contrast, close to 40 percent of second generation Mexicans and Laotian/Cambodians failed to advance beyond high school. The proportion of second generation Laotians and Cambodians with more than a high school education is not significantly higher than among their parents (see Table 1and 2). Mexican-Americans, on the other hand, advanced significantly beyond the first generation. Their below-average achievements relative to other nationalities reflect the very low family educational levels from which they started.2

Family incomes follow closely these differences. In South Florida, middle-class Cuban-Americans enjoy a median family income of over $70,000 and mean incomes over $104,000, while second generation West Indians have median incomes of just above $30,000 and Haitians even less. Approximately one-third of these mostly black groups have annual incomes of $20,000 or less. In California, similar differences separate second generation Chinese, Filipinos, and other Asian-Americans with average incomes above $57,000 from Mexicans and Laotian/Cambodians with mean incomes in the mid-30s. Median incomes of these Southeast Asian refugee families are the lowest in the sample.3

The dictum that ‘the rich get richer and the poor get children’ is well supported by figures in Table 2. Only 3 percent of middle-class Cuban-Americans have had children by early adulthood. The figure is 0 percent for Chinese Americans. The rate then rises to about 10 percent of the Vietnamese; over 15 percent of Colombians, public school Cubans, and Filipinos; 25 percent among Haitians, West Indians, Laotians and Cambodians; and a remarkable 41 percent among Mexican-Americans. Hence, the second generation groups with the lowest education and incomes are those most burdened, at an early age, by the need to support children, a third generation that will grow up in conditions of comparable disadvantage.

Still more compelling evidence comes from differences in incidents of arrest and incarceration. Young males are far more likely than young females to be arrested and to find themselves behind bars. Yet, among Chinese males in the CILS sample no one did so and among middle-class Cubans just 3 percent did. The rate then climbs to 1-in-10 among Laotian/Cambodians; 19 percent among Salvadorans and other Latins in California; and a full 20 percent among Mexicans, Jamaicans, and other West Indians. To put these figures into perspective, they can be compared with the nationwide rate of incarcerated African-American males, ages 18 to 40 – 26.6 percent (Western 2002; Western and Beckett 1998). With another 16 years to go on average, it is quite likely that second generation Mexicans, Salvadorans, and West Indians will match or surpass the African-American figure.

This is the most tangible evidence of downward assimilation available to date. It clusters, overwhelmingly, among children of non-white and poorly educated immigrants, reflecting the lasting effects of low parental human capital, unstable families, and a negative mode of incorporation. Informative as these results are, they still leave open the question of the relative strength of determinants of upward and downward adaptation in the second generation and the processes through which these outcomes develop. We do not know, for example, whether ‘ethnicity’ trumps ‘class’ in this process, or the extent to which family characteristics persist over time as determinants of adulthood outcomes. An alternative possibility is that such characteristics are translated into early achievement and aspirations patterns in school that, in turn, lead to subsequent ‘hard’ outcomes when children reach adulthood. To examine these and related questions, we must examine determinants of downward assimilation in a multivariate framework. The following section is dedicated to this purpose.

The other important question prompted by these results are the conditions that may lead second generation youths growing up in a context of significant disadvantage to escape lower-class stagnation or downward assimilation and move up educationally and occupationally. The final sections of the paper explore this central question.

b. Multivariate Models

Studying second generation adaptation as a process requires longitudinal data. In this respect, the CILS study provides the best available source for two reasons. First, it allows researchers to establish a clear temporal order between potential determinants, measured at average ages 14 and 17, and early adult outcomes, measured seven years later. Second, it provides data on a series of ‘hard’ objective outcomes in early adulthood that facilitate the construction of a single summary index.

The Downward Assimilation Index (DAI) is a count variable consisting of the unit-weighted sum of a series of discrete negative outcomes experienced by CILS respondents. These include: dropping out of high school, being unemployed (and not attending school), living in poverty, having had a child in adolescence, having been arrested, and having been incarcerated for a crime. DAI’s range is 0-to-6, with higher scores indicating more frequent incidents of downward assimilation. Unlike attitudinal indices, DAI is not intended to measure a single underlying dimension, but rather to summarise a series of separate negative outcomes in the lives of our respondents.

The analysis of sample mortality in the final CILS survey indicates that low-SES, low-achievement students, and those raised by single parents are underrepresented. Hence, DAI’s frequency distribution is likely to underestimate the number of cases experiencing downward assimilation. This made it necessary to correct the coefficients in the following analysis for missing data. As a count variable, DAI is not amenable to ordinary least squares analysis which would yield inconsistent or inefficient estimates; count variables are commonly modeled as Poisson processes (Long 1997); however, Poisson regression models rarely fit the data because of the assumption of equidispersion in the conditional distribution μi = σ = exp(χiβ). Negative binomial regression (NBR) obviates this constraint by replacing the conditional mean by a random variable, μ, where μi = (xiβ+Σi) and Σi is random error uncorrelated with xi (Long 1997: 233).

As predictors of DAI, the model includes parental SES, family composition, and national origins, plus controls for age and sex. Subsequently, we nested these estimates in models that add the effects of the type of school attended in early adolescence, indexed by its ethnic and class composition. Finally, we add early adaptation outcomes – namely junior high school grades and educational expectations, measured in the first CILS survey, in order to examine the extent to which these variables mediate the early effects of family status, family composition and modes of incorporation. These models allow us to see how the adaptation process unfolds over time and the extent to which it is cumulative as the effects of exogenous variables are mediated by subsequent life events or, on the contrary, those effects are impervious to the influence of later factors.4

NBR coefficients can be transformed into percentages indicating the net increase/decrease in the relative probabilities of the dependent variable associated with a unit increase in each predictor. For clarity of presentation, we present these figures only for coefficients that are statistically significant. We use robust standard errors to correct for the clustered, multi-stage design of the CILS sample. The corrected SEs do not affect the actual coefficients, but they adjust for underestimation of errors that can lead to inflated z-scores. Robust SEs give us a much more demanding criteria for statistical significance than ordinary ones so that results that meet these criteria can be tagged as reliable.

Tables 3 and 4 present both unadjusted models and those adjusted for sample selectivity. The Heckman adjustment constructs a selectivity estimator, λ, and enters it additively into the substantive equation. As just noted, predictors of selectivity overlap with substantive ones, indicating the underrepresentation of disadvantaged respondents in the final survey. For this reason, we present both models and comment on the substantive significance of the selectivity coefficients.

Table 3.

Exogenous Determinants of Downward Assimilation in the Second Generation1

| Predictor | I | II2 | III | IV2 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| z-score | % change3 | z-score | % change3 | z-score | % change3 | z-score | % change3 | |

| Family SES | −5.90*** | −19.8 | −2.73** | −9.9 | −4.64*** | −16.6 | −1.75 | n.s. |

| Stable Family4 | −6.89*** | −30.2 | −0.74 | n.s. 5 | −6.78*** | −29.9 | −0.74 | n.s. |

| Age | 2.04* | 6.7 | 1.46 | n.s. | 2.67** | 9.1 | 2.08* | 6.9 |

| Sex (Male) | 2.86** | 15.9 | 1.14 | n.s. | 2.95** | 16.4 | 1.19 | n.s. |

| National Origin: | ||||||||

| Haitian | 2.57* | 41.6 | 3.30** | 57.3 | 2.05* | 32.1 | 2.83** | 47.8 |

| Jamaican/West Indian | 3.81*** | 50.6 | 3.83*** | 51.3 | 3.68*** | 48.4 | 3.71*** | 49.3 |

| Mexican | 7.00*** | 61.7 | 5.32*** | 45.6 | 5.32*** | 51.4 | 3.56*** | 33.1 |

| Lao/Cambodian | 1.82 | n.s. | 1.96 | n.s. | 1.05 | n.s. | 0.94 | n.s. |

| School Characteristics: | ||||||||

| School SES | -- | -- | -- | -- | −3.36** | −0.4 | −3.22** | −0.4 |

| Minority School | -- | -- | -- | -- | −1.00 | n.s. | −1.72 | n.s. |

| λ6 | -- | -- | 9.76*** | 39.8 | -- | -- | 9.87*** | 40.3 |

| Constant | −2.07** | -- | −2.90** | -- | −3.02** | -- | −3.17** | -- |

| Wald Chi Square | 229.54*** | 365.33*** | 246.83*** | 388.05*** | ||||

| Log Likelihood | −3177.05 | −3076.22 | −3171.30 | −3070.26 | ||||

| N | 3168 | 3115 | 3168 | 3115 | ||||

Negative binomial regression coefficients. Positive coefficients indicate higher probability of downward assimilation.

Models corrected for sample selectivity.

Net change in the probability of downward assimilation per unit change of predictor.

Both biological parents present.

N.S. = not significant.

Heckman sample selectivity adjustment.

p <.05

p < .01

p < .001

Table 4.

Exogenous and Endogenous Determinants of Downward Assimilation in the Second Generation1

| Predictor | I | II2 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| z-score | % change3 | z-score | % change3 | |

| Family SES | −2.74** | −10.2 | −2.56* | −10.0 |

| Stable Family | −5.58*** | −25.1 | −4.36*** | −24.8 |

| Age | 1.60 | n.s. 4 | 1.60 | n.s. |

| Sex (Male) | −0.02 | n.s. | −0.02 | n.s. |

| National Origin: | ||||

| Haitian | 2.34* | 37.7 | 2.33* | 37.9 |

| Jamaican/West Indian | 3.13** | 40.8 | 3.13** | 40.9 |

| Mexican | 2.98** | 26.1 | 2.97** | 26.1 |

| Lao-Cambodian | 1.49 | n.s. | 1.48 | n.s. |

| School Characteristics: | ||||

| School SES | −3.42** | −0.40 | −3.40** | −0.4 |

| Minority School | −4.18*** | −23.3 | −4.04*** | −23.2 |

| School Outcomes: | ||||

| Jr. High GPA | −11.30*** | −29.7 | −7.09*** | −29.4 |

| Jr. High Educ. Expectations | −3.48** | −9.0 | −3.48** | −9.0 |

| λ5 | -- | -- | 0.08 | n.s. |

| Constant | −0.09 | -- | −0.11 | -- |

| Wald Chi Square | 444.63*** | 446.10*** | ||

| Log Likelihood | −3015.10 | −3015.10 | ||

| N | 3104 | 3104 | ||

Negative binomial regression coefficients. Positive coefficients indicate higher probability of downward assimilation..

Models corrected for sample selectivity.

Net change in the probability of downward assimilation per unit change of predictor.

N.S. = Not significant.

Sample selectivity adjustment.

p < .05

p < .01

p < .001

c. Determinants of Downward Assimilation

Table 3 presents early determinants of second generation adaptation in the two stages described previously. The first model includes parental SES, family structure, and nationality dummies for the groups found to be at greatest disadvantage in the preliminary results: children of Mexican, Haitian, West Indian, and Lao-Cambodian parents.5 The second model adds the additive effects of early school characteristics. Positive coefficients indicate greater probabilities of downward assimilation. Unadjusted results in the first column of the table show the strong inhibiting effects on the DAI of parental SES and stable families and the strong positive effect of Mexican origin. Additional positive and significant effects are associated with sex (males) and all other national origin indicators, except that for Lao-Cambodians.

When the model is corrected for selectivity, the family composition effect drops out, to be substituted for a strong lambda coefficient. All other effects are attenuated, but remain significant, except that of sex. These results reflect the influence of collinearity in the model because family composition is also a predictor of sample selectivity. Substantively, the significant λ coefficient re-states the importance of stable families and also points toward the greater probability of downward assimilation among respondents absent from the final sample.

The strong inhibiting effects of family SES and stable families were expected. So were the effects of a negative mode of incorporation as reflected in national origin. Somewhat unexpected, however, are the strength of the Mexican coefficient and the insignificance of that linked to Lao-Cambodian origins. Substantively, this means that, after controlling for all family characteristics, Mexican-American children continue to experience a significant adaptation disadvantage. On the contrary, the favorable mode of incorporation received by Laotian and Cambodian refugees is reflected in the fact that, once low parental human capital (captured by the family SES index) is taken into account, no handicap linked to national origin remains. Like Mexicans, black Haitian and Jamaican/West Indian parents also experienced a negative mode of incorporation (see Table 1) and this is reflected in resilient nationality effects that do not disappear after family controls are introduced.

The addition of school characteristics does not modify these conclusions, except to demonstrate the expected effect of average school SES: students attending higher-status schools in early adolescence are significantly less likely to experience downward assimilation later on in life. This effect does not remove, however, those of family characteristics or contexts of incorporation. The greater proclivity of second generation males to find themselves in a disadvantaged situation in early adulthood was anticipated. It is a consequence of the stronger tendency of young males to leave school prematurely and to be incarcerated. However, this gender effect is not resilient and disappears when models are adjusted for sample selectivity or when new variables are introduced, as seen next.

Equations adding early school outcomes are presented in Table 4. They include junior high GPAs and educational expectations at that time. These variables were measured in the original CILS survey so they are causally prior to indicators of downward assimilation, measured in the third. Once these variables are added to the equation, the correction for sample selectivity drops out, reflecting the fact that presence/absence in the last follow-up is significantly affected by early academic achievement. The substantive effect of this variable (GPA) is very strong, as shown by the corresponding z-score: every one-point increase in early grades reduces the probability of downward assimilation by a net 30 percent. The influence of educational ambition, although weaker, runs in the same direction with college and post-college aspirations reducing DAI scores by 9 percent.

A theoretically important finding is that, with these controls in place, the long-term influence of exogenous factors, though attenuated, remains significant. Stable families still reduce the likelihood of downward assimilation by a net 25 percent and each standard deviation in the family SES index leads to an additional 10 percent reduction. Still more important, the previously observed nationality effects persist. Substantively, these results say that early academic achievement and ambition significantly affect subsequent adaptation outcomes, but do not ‘filter’ the influence of core structural determinants.

Average school SES continues to have its expected significant effect, with each additional SES point reducing DAI scores by 0.4 percent. Less expected is the effect of school ethnic composition. This coefficient is now highly significant, but its direction is opposite from expected: junior high schools with 60 or more percent minority students (coded higher) reduce downward assimilation, controlling for other variables. Part of the explanation for this result is the inclusion in the CILS sample of 100 percent Hispanic bilingual private schools in Miami whose students tend to do quite well in all indicators of achievement. With other factors controlled, this particularity of the sample comes to the fore. It should be noticed, however, that this minority school effect only emerges when grades and educational aspirations are controlled. Hence, it is only among statistically equivalent students in academic achievement and ambition that mostly minority school exercise a positive influence.

After controlling for all early school variables, Mexican-American youths continue to have a 26 percent chance of greater downward assimilation and the two predominantly black minorities in the sample – Haitians and Jamaican/West Indians – about a 40 percent greater chance relative to the rest of the sample. These results are a poignant indicator that not only are there are major differences among immigrant nationalities in adaptation outcomes, but that these differences endure into adulthood, even after taking educational achievement and aspirations into account. Children from middle-class families that stayed together and experienced a favorable or at least neutral context of reception have little probability of downward assimilation; those at the other end of the spectrum have a much higher probability of doing so.

In synthesis, this analysis provides conclusive answers to the two questions posed to segmented assimilation theory in the introductory section. First, there is strong evidence of downward assimilation in the second generation; second, the process is not random but patterned by the exogenous factors identified by the theory. In this sense, the model offers a more nuanced account of the process of adaptation than blanket predictions of second generation success. The support for segmented assimilation theory provided by these results does not extend, however, to evidence of the role of the intervening factors associated with the pace of acculturation, as portrayed in Figure 2. That role must be inferred indirectly from the causal power of family variables, especially stable families. There are, however, additional and more direct indicators of the bearing of selective acculturation on the adaptation process. This comes from the last stage of the CILS project, discussed in the next section.

Overcoming Disadvantage

Sociology deals, for the most part, with rates and averages, not with exceptions. There are instances, however, when outliers can teach us something valuable about additional factors obscured by main causal forces. While the power of the exogenous variables identified by segmented assimilation is almost frightening in its implications, it is not necessarily the case that every child advantaged by family background and a favorable context manages to pull forward; nor that those disadvantaged by poverty and a negative mode of incorporation succumb to stagnation or downward mobility. If some instances of success-out-of-disadvantage in the second generation can be identified, they could teach us something important about factors other than random luck that would be significant in overcoming the effects of poverty and a negative mode of incorporation.

Two features of the CILS project come to our assistance in seeking to address this issue. First, its large sample size and second, its longitudinal character. Just as these two features proved important in testing the overall theory, they can also help us identify exceptional cases. To do this, we first located the sub-sample of CILS respondents that grew up in conditions of severe disadvantage. These are children who, at average age 14, were living in poor and frequently disrupted families and whose parents experienced a negative context of reception.

We then pose the question of whether any members of this sub-sample managed to overcome these handicaps in order to graduate from a 4-year college and start a professional career or attend graduate school in early adulthood. The answer to this question comes from the third CILS survey. From an initial sample of over 5,200 respondents, we identified just fifty cases that met these criteria. The next logical step was obviously to trace this small group of exceptional young men and women and re-interview them, as well as members of their immediate families.

This was done during the summer and fall of 2006 during the final stage of the study, dubbed CILS-IV. In total, sixty-one interviews were completed with respondents, their parents, and their spouses, if married. We were aided in this effort by the availability of tracking information from the CILS files which made possible effective Internet searches and by the willingness of our respondents to be re-interviewed. In general, it is easier to talk about success than failure and this feature played into our hands by facilitating lengthy and detailed interviews. These interviews were not conducted by hired staff, but by the authors themselves in an effort to obtain maximum information from this exceptional sample.

This last stage of the CILS project is qualitative and its conclusions emerge from reflection on common trends identifiable in the interviews. We do not present all the trends identified in this final stage of the study, but only those necessary to ‘round the picture’ by bearing on the general theoretical model in Figure 2. For this purpose, we include selected personal stories from CILS-IV interviews that are useful for illustrating the principal patterns.

a. Parenting and Selective Acculturation

The child-rearing and educational psychology literatures have converged in preaching to parents a tolerant, patient, non-authoritarian attitude toward their offspring; and in promoting openness to new experiences and intensive socializing among the young. In parallel fashion, schools and other mainstream institutions pressure immigrants and their children to acculturate as fast as possible, viewing their full Americanization as a step forward toward economic mobility and social acceptance (Unz 1999; Alba and Nee 2003).

Not really. A leitmotif in the CILS-IV interviews was the presence of strong and stern parental figures who controlled, if not suppressed, extensive external contacts and who sought to preserve the cultural and linguistic traditions in which they themselves were raised. Talking back to such parents is not an option and physical punishment is a distinct possibility when parental authority is challenged. These family environments have the effect of isolating children from much of what is going on outside: they are expected to go to school and return home with few distractions in between. While such rearing practices may be frowned upon by educational psychologists, they have the effect of protecting children from the perils of street life in their immediate surroundings.

Put differently, while freedom to explore and tolerant parental attitudes may work well in protected suburban environments, they do not have the same effect in poor urban neighborhoods where what there is to ‘explore’ is frequently linked to the presence of gangs and the drug trade. In addition, and contrary to conventional wisdom, full Americanization has the effect of disconnecting youths from their parents and depriving them of a cultural reference point on which to ground their sense of self and their personal dignity. As we shall see, this reference point is also an important component of these success stories.

Maintenance of parental authority and strong family discipline have the effect of inducing selective acculturation, as opposed to the full-barreled variety advocated by public schools and other mainstream institutions. Selective acculturation combines learning of English and American culture with preservation of key elements of the parental heritage, including language. Previous studies based on CILS and other data have shown that fluent bilingualism is significantly associated with positive outcomes in late adolescence, including higher school grades, higher educational aspirations, higher self-esteem, and lesser intergenerational conflict (Peal and Lambert 1962; Hakuta 1986; Rumbaut 1994; Portes and Hao 2002). The CILS-IV interviews confirm this result, indicating that instances of success-out-of-disadvantage are almost invariably undergirded by strong parental controls, leading to selective acculturation. These results are congruent with the theoretical expectations of the model.

b. Outside Help

First Narrative: Raquel Torres, Mexican, aged 29, interviewed in San Diego, July 2006

Raquel Torres is the oldest daughter of a Mexican couple who emigrated illegally to San Diego after living for years in Tijuana. The mother has a ninth grade education and did not work while her three children were growing up; the father has a sixth grade education. While living in Tijuana, he commuted to San Diego to work as a waiter. At some point, his commuter permit was taken away and the family simply decided to sneak across the border. They settled in National City, a poor and mostly Mexican neighborhood where Raquel grew up monolingual in Spanish. As the result of her limited English fluency, she had problems at El Toyon Elementary, but she was enrolled in a bilingual training program where children were pulled out of classes for intensive English training. ‘My teachers were wonderful,’ she says.

It was while attending elementary school that she noticed how poor her family really was. She wanted jeans, tennis shoes, popular toys that she saw other children having, but her parents said no. ‘No tenemos dinero,’ (we don’t have any money), they responded. On the other hand, discipline at home was stern: ‘My parents, they brought us up very strict, very traditional, there was no argument; you just got the look and knew better than to insist.’ In middle school, she made contact with AVID (Achievement via Individual Determination). While she was still struggling with English, AVID provided her with a college student as a tutor and took her in field trips to San Diego State University. ‘It was a fabulous field trip; we were paired up with other students and sat in class. Mine was on biology. Still, I hadn’t thought of going to college.’

The decisive moment came in her first year at Sweetwater Senior High in National City after she enrolled in Mr. Carranza’s French class. Carranza, a Mexican-American himself and a Vietnam veteran, took a keen interest on his students. ‘I mean, it wasn’t so much the French that he taught, but he would also bring Chicano poetry and, within the first month, I remember he asked me, ‘Where are you going to college?’’ At Open House that year, Carranza took her mother apart, ‘Usted sabe que su hija es muy inteligente?’ (Do you know that your daughter is very intelligent?) ‘De veras, mi hija?’ (Really, my daughter?) answered the mother. ‘Yes,’ he said, ‘she can go to college.’ ‘All of a sudden, everything made sense to me; I was going to college.’

Raquel graduated with a 3.5 GPA from Sweetwater and applied and was admitted at the University of California – San Diego. At the time, her family had moved to Las Vegas in search of work, but Raquel wanted to be on her own. She had clearly outgrown parents who, at this time, had started to be an obstacle. ‘When I was studying late at night in senior high, my mother would come and turn off the light. She would say, ‘Go to sleep, you’ll go blind reading so much.’’ Raquel entered UCSD in the last year of the Affirmative Action Program in California. As a result, she got some lip from several fellow students who criticised her for getting an unfair advantage. But she strongly defends the program: ‘Without Affirmative Action, I probably would not have made it into UCSD. Besides, the Program made me work harder. Other students took their education for granted and didn’t study as much, instead going to parties and fooling around.’

Raquel graduated from UCSD with a 3.02 GPA and immediately enrolled in a Masters in Education at San Diego State. After graduating, she took a job as a counselor in the Barrio Logan College Institute, another private organization helping minority students like herself attend college. She is currently planning to enroll in a doctoral program in education. Her advice for immigrant students: ‘Stop making excuses; there’s always going to be family drama, there’s always gonna be many issues. But it’s what you want to do that matters.’

Despite these ‘where there’s a will, there’s a way,’ parting words, it is clear that Raquel Torres moved ahead by receiving assistance in multiple ways. First, the stern traditional family upbringing that we saw previously kept her out of trouble, although it set her back in English. Her own selective acculturation had to be nudged along by those ‘wonderful’ teachers at El Toyon Elementary. Then she encountered the AVID program which provided her with personalised educational assistance and the first inklings of what college life would be like.

Finally, she met Carranza and her future took a decisive turn. The French teacher did not ask whether she was going to college, but what college she would attend. The fact that he was a co-ethnic and brought ‘Chicano poetry’ to class surely helped. He went beyond motivating her to recruiting the mother in order to support Raquel’s new aspirations. Stern immigrant parents may instill discipline and promote selective acculturation in their children, but they are often helpless in the face of school bureaucracies. The last bid of important outside help that Raquel received was enrolling in the now phased-out Affirmative Action Program. The program allowed her to attend a first-rate institution, rather than a regional college. Nevertheless, after Carranza’s intervention, it was clear that Raquel would attend college one way or another.

A constant in our sixty-one interviews, in addition to authoritative and alert parents, is the appearance of a really significant other. That person can be a teacher, a counselor, a friend of the family, or even an older sibling. The important thing is that they take a keen interest in the child, motivate him or her to graduate from high school and attend college, and possess the necessary knowledge and experience to guide the student in this direction. Neither family discipline nor the presence of a significant other is by itself sufficient to produce high educational attainment but their combination is decisive.

The second element that Raquel Torres’ story illustrates is the important role of organised programs sponsored by non-profits to assist disadvantaged students. Whether it is AVID; the PREUSS Program, also organised by the University of California; Latinas Unidas; the Barrio Logan College Institute; or other philanthropic groups, they can play a key supplementary role by conveying information that parents do not possess: how to fill a college application; how to prepare for Standardized Admissions Tests (SATs) and when to take them; how to present oneself in interviews; how college campuses look and how college life is like, etc.

This finding is important because the creation and support of such programs is within the power of external actors and can be strengthened by policy. While the character of family life or the emergence of a really significant other is largely in the private realm, the presence and effectiveness of special assistance programs for minority students is a public matter, amenable to policy intervention. The programs and organizations that proved effective were grounded, invariably, on knowledge of the culture and language that the children brought to school and on respect for them. They are commonly staffed by co-ethnics or, at least, bilingual staff. Thus, unlike the full assimilation approach emphasised by public school personnel, these programs convey the message that it is not necessary to reject one’s own culture and history in order to do well in school. In this sense, AVID and similar programs both depend and promote selective acculturation as the best natural path toward educational achievement.

c. Cultural Capital

Second Narrative: Luis Donato Esquivel, Mexican-American, aged 28, interviewed with his parents in San Diego, July 2006

The modest home of Jose Donato Esquivel and his wife, Griselda, in a working-class neighborhood of San Diego, is vintage Mexican, featuring a living room replete with family portraits, velvet-covered furniture, and lots of lace. Born in Tijuana, Jose, now aged 51, met Griselda in that city, to which her family had moved from Monterrey. Jose managed to graduate from high school, but then had to drop out to go to work; Griselda has a grade school education and has worked cleaning houses all her life. The couple eventually moved to San Diego, first illegally, but then managed to get their green cards with help from Griselda’s father who was already living there as a legal immigrant. It was in San Diego that Jose and Griselda had their three children. The middle one, Luis Donato, fell into the CILS sample.

In San Diego, Jose Sr. worked at a succession of manual jobs until he managed to get a more stable one as service supervisor in a Honda dealership; Griselda always cleaned houses. Despite both working outside the home, they held tightly to their children. Discipline at the Esquivel home was tight. Griselda asserts that she and her husband nunca les dimos libertad (we never gave our children freedom). Luis was not allowed to have friends his parents did not approve of. A curfew was not necessary because the children were expected to be at home most of the time. Even while attending college, Luis was persuaded to continue living at home.

Father and son share the second name ‘Donato’ in honor of his grandfather, an accountant and businessman in Mexico. He was a big man in his city, fathering many children by different women, but he managed to care and inspire respect and admiration in all of them. Luis’ younger brother also bears his name. Luis attributes his exceptional ability in math, a subject in which he excelled in high school, to his grandfather’s influence. As an accountant, Donato Sr. was well-known for his skill with numbers.

Despite being U.S.-born, Luis took a keen interest in the history of his family in Mexico and in Mexican culture in general. The proximity of San Diego to the border and the presence of kin in Tijuana allowed him to travel there several times. Later in life, when he could afford it, he travelled to Mexico City to learn more about the country and its customs. Meanwhile, his good grades and good disposition for schoolwork caught the attention of a high school counselor, Janina Fernandez, who eventually helped him with his college applications. With her assistance, he also gained admittance into a program for minority high school students that took him to the University of California-Berkeley for three summers in a row, all expenses paid.

Luis graduated with honors from Morse High School in 1997 and was admitted to Berkeley. It was at this point that his father intervened: ‘Look, you’re going to go to that big-name university and meet other people, maybe marry a woman from that area and so you will abandon us. What’s the difference if you go to Berkeley? We have good universities here.’ Reluctantly, Luis cancelled his admission to Berkeley and enrolled in San Diego State. There, he did exceptionally well majoring in math, one of only 50 students in a class of 20,000 who did so. In 2001, he graduated with a 3.75 GPA, getting to wear at Commencement the white robe of high honors. His parents attended the ceremony: ‘Ahí si uno se siente con tal orgullo que hasta se le caen los calcetines’ (there I was so flush with pride that even my socks fell off).

Luis is currently a high school maths teacher pursuing a Master’s degree in order to be able to teach at the college level. He has married a woman of Mexican descent, also a college graduate. They both maintain a strong interest in things Mexican, travelling there frequently. Jose Sr. says that, despite his son and daughter-in-law being U.S.-born, ‘They are more Mexican than I; they celebrate all Mexican holidays.’ At his high school, Luis teaches five classes per day to all kinds of students, including undocumented Mexicans. He despairs at the low achievement of these children, handicapped by their lack of English and poor families. ‘Parents rarely attend meetings with teachers like my own parents did; how can we teach them to do better for their kids?’ he asks.

Luis Esquivel’s story embodies all the elements seen previously: the importance of stern parenting and of significant others; the role of external assistance programs; the barriers that well-meaning but poorly educated parents can throw in the path of their offspring. In Luis’ case he had to trade the University of California – Berkeley for San Diego State. For Don Jose one university was as good as another and, crucially, he wanted his son at home. There is, however, one other factor that this story illustrates with singular clarity, namely the importance of symbolic assets, cultural capital, transformed from the country of origin.

The parents of our respondents repeated stories of who they or their ancestors ‘really were’ as a way to sustain their dignity, despite their humble present circumstances. Children exposed to those stories often introject them, using them as a spur to achievement. We heard references to uncles and grandparents who were ‘doctors’ or ‘professors’ in Mexico; to ancestors who were ‘landowners in California and put down an Indian rebellion’; and to parents who were high government officials before having to leave escaping political persecution.

This cultural capital brought from abroad actually has two components. The first is the motivational force to restore family pride and status. Regardless of whether the achievements of the past are real or imaginary, they can still serve as a means to instill high aspirations among the young. The second is the ‘know-how’ that immigrants that did originate in their country’s middle-classes possess. This know-how consists of information, values, and demeanor that migrants from more modest origins lack. Regardless of how difficult present circumstances are, former middle-class parents have a clear sense of who they are, knowledge of the possible means to overcome the situation, and the right attitude when opportunities present themselves. These two dimensions of cultural capital converge in cases where both family lore and the habitus of past middle-class life are decisive in helping second generation youths overcome seemingly insurmountable obstacles.

In the case of Luis Esquivel the towering figure of his grandfather played a decisive role. While his father, the son of a single mother forced to go to work early in life, had dropped significantly in the social hierarchy, he kept very much alive the memory of the achievements and demeanor of his own father. That Donato Sr. had been ‘good with numbers’ and a prominent figure in Mexico spurred his grandson to imitate him and to take an interest in his ancestral country, thereby promoting his own selective acculturation.

While not part of the CILS sample, the story of Dan-el Padilla provides another suitable illustration of this pattern. Dan-el was the 2006 Latin Salutatorian at Princeton University in which he majored in Classics, graduating with the highest honors. He is a black Dominican migrant who grew up in the Bronx with his mother and siblings. The father returned to the Dominican Republic and never came back. Dan-el’s family alternated between spells of homelessness, sleeping in shelters, and public housing. All the while, he attended the worst public schools in the Bronx. A junior high school teacher gave him a book on classics and that little gesture set his course. The boy persisted, graduated from high school with highest honors and gained admission to Princeton. After delivering his address in Latin in May 2006, he proceeded to announce that he himself was an undocumented immigrant.

What saved the day in Dan-el’s case was the solid middle-class status of the family in the Dominican Republic. Though black, both parents were university-educated and the father had been a prominent functionary before losing his job in a government change. He refused to stay in the United States for fear of having to toil in menial jobs beneath his dignity. It was the mother who migrated and faced life in dire circumstances in America for the sake of her children. Despite terrible conditions in the Bronx, Dan-el always kept alive the memory of that middle-class life and schooling in his native country. When his teacher gave him that book on classics, he fully understood what it meant.

Cultural capital brought from the home country is a product of selective acculturation. Referring to the theoretical model in Figure 2, it is clear that dissonant acculturation deprives youths of this resource, as they lose contact or even reject the language and culture of parents. Whatever resources are embodied in that culture effectively dissipate. Consonant acculturation is less problematic but, as both parents and children strive to Americanise, it is unlikely that family memories and ancestral cultures can be used either as an anchor or as a point of reference. Only selective acculturation provides a natural path to make full use of symbolic resources brought from abroad.

Conclusion

Soon, one-in-four of all young Americans will be an immigrant or a child of an immigrant. This surging population cannot but have a deep effect on the entire society and, especially, on the cities and regions where it concentrates. Following the lead of classic assimilation theory, some scholars have advanced a highly optimistic prognosis about the future of this population: children of immigrants will assimilate into English and American ways, advance educationally and occupationally, and take their rightful place into society’s mainstream (Alba and Nee 2003).

There are valid grounds for this prognosis since the majority of this population is managing to do well in school and avoid the pitfalls that can derail their progress. However, this optimistic outlook neglects two facts: first, a sizable minority is not managing to overcome these challenges; second, those who do not come disproportionately from certain immigrant groups and not others. Young men and women from these groups are also assimilating, but they are doing so to sectors of U.S. society that are not conducive to their upward mobility. The concept of downward assimilation was coined to capture this reality.

The contemporary research literature on poverty and juvenile delinquency commonly deals with outcomes of the process. However, by relying on pan-ethnic labels – ‘Asians’, ‘Hispanics’, ‘Blacks’, etc. – this literature cannot clarify the root causes and the sequence of events leading to these unenviable results. To do so, it is necessary to learn about the specific histories of each national minority, including the characteristics of the immigrant generation and the political and social context that it met at arrival. Aggregating a number of such groups into pan-ethnic categories obscures rather than clarifies the causal processes at play.

The data analyzed in this paper is more appropriate for clarifying how the process of segmented assimilation unfolds. It focuses exclusively on the second generation and identifies individual nationalities within it. Past results based on this data set gave rise to the theoretical models presented in Figures 1 and 2. This article presents a synthesis of more recent findings showing how the process plays itself over time and what effects school context, academic outcomes, and selective acculturation have on it.

These effects are of two types: first, those that mediate or reinforce the three exogenous determinants in Figure 1; second, countervailing factors in the process of acculturation, leading to upward mobility. The first set of effects indicates that school contexts, in particular the average status of the student body, has a reliable influence on adult outcomes, even when controlling for family characteristics. They also show that school outcomes – academic achievement and educational ambition – play a strong inhibiting role on downward assimilation reinforcing those of parental SES and intact families.

Finally the results point to the resilient effects of certain national origins, used as a proxy for a negative mode of incorporation. These effects are impervious to mediation by school characteristics or academic outcomes and impinge directly on the likelihood of downward assimilation. The fact that one of these disadvantaged groups, Mexican-Americans, is, by far, the largest among today’s second generation is worthy of attention and should give pause to optimistic declarations about the future of this population.

The second set of effects draws on the intervening variables identified in Figure 2 to show how factors associated with selective acculturation may countermand the power of exogenous determinants and lead, in exceptional cases, to educational and occupational success from backgrounds of severe disadvantage. These factors are associated, first, with authoritative parenting and prevention of dissonant acculturation; second, with the presence of significant others and external assistance programs; third, with the preservation of cultural skills and family memories brought from the home country.

What practical lessons can be derived from this analysis? A first is the difference that an immigrant population bifurcated by human capital can make. If all contemporary immigration were composed of professionals and entrepreneurs, most of the negative outcomes linked to downward assimilation would go away. That scenario will not materialise, however, because of the persistent and growing need of the American economy for low-wage manual labor (Massey et. al. 2002). This structural demand in large sectors of the economy such as agriculture, construction, and personal services virtually guarantees that poor immigrants will continue to come. To the extent that they bring their families along, the problems associated with low parental human capital and a negative mode of incorporation will continue.

A second lesson is how these initial disadvantages transform themselves into objective outcomes. While over 40 percent of Mexican-American youths in the sample were burdened by premature childbearing and 20 percent of Mexican-American, Central American, and West Indian young males had already been incarcerated for a crime, just 50 cases or less than 1 percent of the original sample managed to overcome the consequences of a heavily disadvantaged upbringing. In the long term, these are unacceptable outcomes since, if projected into the future, they would lead to an increasingly unequal society, the expansion of areas of poverty associated with particular ethnicities, and the perpetuation of an urban nightmare of crime, drugs, imprisonment, and death.

The third lesson coming from these results consists of factors that can make a difference in leveling the field for disadvantaged children of immigrants. Making successful outcomes less exceptional among this population should be a public policy priority. The tools to accomplish this goal are at hand in the creation and support of voluntary after-school programs, in the promotion by teachers and counselors of a selective acculturation pattern, and in the creation of incentive schedules for school personnel to take a real interest in the future and prospects of immigrant students. Firms and employers who profit greatly from immigrant labor should also accept part of the financial burden required to insure that the children have at least a fighting chance to attain the American dream. Making assimilation less ‘segmented’ emerges from this analysis as a public good to be sought, not only for the sake of immigrant children, but of the entire society.

Footnotes

The ‘other’ category is comprised of children of Canadian, European, and Middle Eastern immigrants.

The proportion of second generation Mexican-Americans with high school education or less is approximately half the corresponding figure among their parents in the CILS survey, 70 percent. This indicates both the very low level of human capital of Mexican immigrant parents and the considerable educational strides made by their children in the U.S.

The Laotian/Cambodian figures indicate that extensive governmental assistance for these refugee groups did not suffice to lift them out of poverty, as least on average. The very low levels of parental human capital trumped, in this case, a favorable mode of incorporation linked to their refugee status.

Descriptive characteristics of the variables used in this analysis are omitted for reasons of space. They are found in http://cmd.princeton.edu/papers/wp0802Appendix.pdf.

Contributor Information

Alejandro Portes, Princeton University.

Patricia Fernández-Kelly, Princeton University.

William Haller, Clemson University.

References

- Alba RD, Nee V. Remaking the American Mainstream: Assimilation and Contemporary Immigration. Cambridge MA: Harvard University Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Bluestone B, Harrison B. Advantage and Disadvantage: A Profile of American Youth. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum; 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez-Kelly P, Konczal L. “Murdering the Alphabet” Identity and Entrepreneurship among Second-Generation Cubans, West Indians, and Central Americans. Ethnic and Racial Studies. 2005 Nov;28:1153–1181. special issue of. [Google Scholar]

- Gans H. Second-Generation Decline: Scenarios for the Economic and Ethnic Futures of the Post-1965 American Immigrants. Ethnic and Racial Studies. 1992;15:173–92. [Google Scholar]

- Geschwender JA. Racial Stratification in America. Dubuque, IA: William C. Brown; 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Hakuta K. Mirror of Language: The Debate on Bilingualism. New York: Basic Books; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Haller W, Landolt P. The Transnational Dimensions of Identity Formation: Adult Children of Immigrants in Miami. Ethnic and Racial Studies. 2005 Nov;28:1182–1214. special issue of. [Google Scholar]

- Hirschman C. Exit, Voice, and Loyalty: Responses to Decline in Firms, Organizations, and States. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 1970. [Google Scholar]

- Hirschman C. The Educational Enrollment of Immigrant Youth: A Test of the Segmented Assimilation Hypothesis. Demography. 2001 Aug;38:317–336. doi: 10.1353/dem.2001.0028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]