SUMMARY

The ZIC transcription factors are key mediators of embryonic development and ZIC3 is the gene most commonly associated with situs defects (heterotaxy) in humans. Half of patient ZIC3 mutations introduce a premature termination codon (PTC). In vivo, PTC-containing transcripts might be targeted for nonsense-mediated decay (NMD). NMD efficiency is known to vary greatly between transcripts, tissues and individuals and it is possible that differences in survival of PTC-containing transcripts partially explain the striking phenotypic variability that characterizes ZIC3-associated congenital defects. For example, the PTC-containing transcripts might encode a C-terminally truncated protein that retains partial function or that dominantly interferes with other ZIC family members. Here we describe the katun (Ka) mouse mutant, which harbours a mutation in the Zic3 gene that results in a PTC. At the time of axis formation there is no discernible decrease in this PTC-containing transcript in vivo, indicating that the mammalian Zic3 transcript is relatively insensitive to NMD, prompting the need to re-examine the molecular function of the truncated proteins predicted from human studies and to determine whether the N-terminal portion of ZIC3 possesses dominant-negative capabilities. A combination of in vitro studies and analysis of the Ka phenotype indicate that it is a null allele of Zic3 and that the N-terminal portion of ZIC3 does not encode a dominant-negative molecule. Heterotaxy in patients with PTC-containing ZIC3 transcripts probably arises due to loss of ZIC3 function alone.

INTRODUCTION

The gene most commonly associated with congenital situs defects, known as heterotaxy, in humans encodes the X-linked transcription factor ZIC3 (MIM 306955). Mouse models of Zic3 dysfunction also result in heterotaxy, indicating conserved mammalian function of this protein. Deletion of the entire ZIC3 locus in humans, or in the classical mouse mutant bent tail (Bn), results in heterotaxy, indicating that loss-of-function is the most likely pathogenic mechanism (Garber, 1952; Ferrero et al., 1997; Gebbia et al., 1997; Carrel et al., 2000; Klootwijk et al., 2000). To date, 12 ZIC3 variant sequences have also been identified in heterotaxy-affected families: six missense, five nonsense and one frameshift [caused by a two-nucleotide insert, which results in a premature termination codon (PTC) 182 nucleotides upstream from the wild-type transcription termination codon] (Gebbia et al., 1997; Mégarbané et al., 2000; Ware et al., 2004; Chhin et al., 2007). The functional significance of the 12 variant sequences has been investigated in vitro using mutant proteins expressed from ZIC3 full-length cDNAs containing each relevant mutation (Ware et al., 2004; Chhin et al., 2007). The in vivo consequence of the mutations that produce a PTC-containing transcript is, however, hard to predict from these analyses. In vivo these mutant transcripts might be subjected to nonsense-mediated decay (NMD), whereas the cDNA variants used to model these mutations would typically evade NMD, which, in mammalian cells, appears dependent upon mRNA splicing (Neu-Yilik et al., 2001).

NMD is a method of gene regulation and surveillance that recognizes and rapidly decays PTC-containing transcripts (Frischmeyer and Dietz, 1999; Maquat, 2004). One purpose of NMD is to limit the formation of C-terminally truncated polypeptides that might possess deleterious gain-of-function or dominant-negative activity. The mechanism by which a normal stop codon is distinguished from a premature one appears dependent upon the position of the PTC; a transcript will be committed to decay if a PTC is situated more than about 50–55 nucleotides upstream of an exon-exon junction (Nagy and Maquat, 1998). Because the rules regarding PTC recognition are not completely understood, the NMD sensitivity of PTC-containing transcripts needs to be assessed on a case-by-case basis (Holbrook et al., 2004). Moreover, not only do transcripts differ in their intrinsic sensitivity to NMD, the efficiency of NMD with respect to a given transcript can vary between tissues. To determine the functional significance of a nonsense mutation, RNA and/or protein levels must therefore be documented in the tissue and stage of development relevant to the particular disorder (Bateman et al., 2003). For heterotaxy cases, this requires assessing mRNA or protein levels at gastrulation (the time of left-right axis formation); a task not possible for human cases of heterotaxy. If the identified ZIC3 PTC-containing transcripts evade NMD, they might code for a ZIC3 molecule with a hypermorphic, hypomorphic or dominant-negative effect.

TRANSLATIONAL IMPACT.

Clinical issue

Heterotaxy, or situs ambiguous, refers to a group of rare congenital defects that are characterized by abnormal organ distribution. In heterotaxy, the normal, asymmetric position of organs (known as situs solitus) is disrupted, and this typically causes severe congenital heart disease that is sometimes accompanied by malformation of other organs. The most commonly mutated gene in heterotaxy is ZIC3, which encodes an X-linked transcription factor that plays a role in embryonic development. Half of the heterotaxy-associated ZIC3 mutations identified to date introduce a premature termination codon (PTC) and the aberrant transcripts are expected to undergo nonsense-mediated decay (NMD). NMD of PTC-containing mRNAs varies in a transcript-, tissue- and stage-dependent manner and incomplete NMD can produce truncated proteins of unknown function. The presence of truncated proteins with varied functional abilities could underlie the remarkable phenotypic diversity observed in cases of heterotaxy.

Results

This study utilizes a novel model of murine Zic3 dysfunction, called katun, which harbours a point mutation that introduces a premature stop codon into the Zic3 transcript. Based on the presence of this PTC, the transcript was predicted to undergo NMD. However, the authors show that at the embryonic stage of left-right axis formation (during which organ asymmetry is established), the transcript evades NMD and a stable truncated protein is generated. They show that the truncated protein lacks endogenous function yet does not interfere with other coexpressed Zic proteins. The authors’ analysis of all known PTC-containing ZIC3 mutations provided the same result: all of the truncated proteins behaved as partial or complete loss-of-function mutants that did not interfere with wild-type ZIC3 function.

Implications and future directions

These results suggest that ZIC3-associated heterotaxy arises due to partial or complete loss of ZIC3 function, and not as a consequence of dominant-negative effects. The work also demonstrates the importance of investigating whether PTC-incorporating mutations lead to NMD in vivo (at the relevant stage and in the appropriate tissue type), rather than assuming that PTC-containing transcripts will be subject to NMD and will generate a null allele. The katun mouse strain will serve as a useful model for further investigations into the molecular pathways underlying ZIC3-associated heterotaxy, and for studies of Zic protein interactions and transcriptional surveillance mechanisms.

There is some evidence from the study of Xenopus zic3 and murine Zic2 that it is possible to produce a dominant-negative Zic molecule (Kitaguchi et al., 2000; Elms et al., 2003; Brown et al., 2005). The X-linked location of Zic3 in humans and mice dictate, however, that the gene is not generally bi-allelically expressed and it is therefore unlikely that the putative dominant-negative activity could affect Zic3 function in vivo. Males are hemizygous for the maternal copy of ZIC3, and females (after random X-inactivation occurs in the embryo proper at implantation) are chimeric for cells that express either the mutant or the wild-type Zic3 allele. Zic3, however, shares significant sequence homology with four other members of the mammalian Zic gene family (Zic1, Zic2, Zic4 and Zic5) (Aruga et al., 1996a; Aruga et al., 1996b; Furushima et al., 2000; Ali et al., 2012). The five genes show extensive homology throughout the DNA binding zinc fingers and Zic1, Zic2 and Zic3 also contain a conserved region within the N-terminal portion of the protein called the ZOC motif (Aruga et al., 2006). The coexpression of family members could, therefore, enable a dominant-negative Zic3 molecule to interfere with the function of other Zic proteins. At the time of axis formation, Zic3 is extensively coexpressed with Zic2 and Zic5 (Furushima et al., 2000; Elms et al., 2004). Some cases of heterotaxy could therefore result from a composite phenotype due to deleterious effects on not only ZIC3 function but also on one or more additional family members. This scenario could partially explain the extreme phenotypic variability associated with ZIC3 cases of heterotaxy (Ware et al., 2004).

Here, we show that the katun (Ka) mouse mutant (Bogani et al., 2004) harbours a mutation in the Zic3 gene that introduces a PTC. At the time of left-right axis formation, the mutant transcript is not subjected to NMD, predicting the production of a mutant protein during embryogenesis. When the analogous mutant cDNA is expressed in cultured mammalian cell lines, a stable protein that is truncated just two amino acids upstream of the zinc finger domain is produced. The truncated protein lacks the zinc finger domain and should fail to undergo nuclear import (Bedard et al., 2007); however, it accumulates within the nucleus as a result of passive diffusion. Despite its presence in the nucleus, the katun protein is unable to elicit transcription of a ZIC3 target promoter and does not compete with the wild-type trans-activation ability of the ZIC3, ZIC2 or ZIC5 proteins, indicating that the N-terminal portion of ZIC3 does not possess dominant-negative activity. Additionally, the katun protein fails to inhibit Wnt-mediated transcription, unlike wild-type ZIC3 protein. The phenotype of katun mutant embryos replicates that of a targeted null allele of Zic3 and confirms that the Ka mutant phenotype results from a loss of Zic3 activity alone.

The relative ability of a transcript to undergo NMD is influenced by sequences within the transcript that promote RNA splicing, such as splice donor and acceptor sites (Gudikote et al., 2005). The murine Zic3 and human ZIC3 transcripts contain identical splice sites so the finding that the murine Zic3 transcript is relatively insensitive to NMD during axis formation and early organogenesis suggests that the human transcript also evades NMD at these stages of embryogenesis. This prompted the examination of other truncated ZIC3 proteins predicted in human heterotaxy cases and none were found to possess dominant-negative activity. The data suggest that ZIC3-associated heterotaxy caused by nonsense or frameshift mutations affects ZIC3 function alone. The katun mutant is useful not only for investigations into the molecular mechanisms underlying ZIC3-associated heterotaxy but also for studies of Zic protein interaction and transcriptional surveillance mechanisms.

RESULTS

The Zic3 gene is mutated in the katun mouse strain

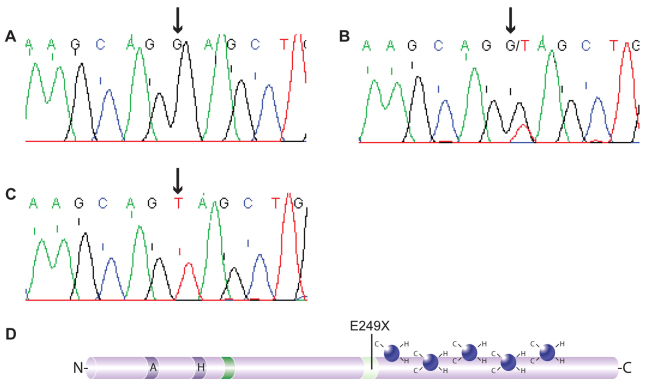

The katun allele arose as a spontaneous, X-linked mutation during an N-ethyl-N-nitrosourea (ENU) mutagenesis experiment (Bogani et al., 2004), indicating that it might be a new allele of Zic3, the gene deleted in the classical, X-linked mouse mutant bent tail (Bn) (Carrel et al., 2000; Klootwijk et al., 2000) and mutated in targeted mouse strains (Purandare et al., 2002; Zhu et al., 2007). The coding region of Zic3 was amplified from the genomic DNA of a heterozygous female, a hemizygous male, a C3H mouse and a BALB/c mouse and sequenced. This revealed a single base change of guanine (G) to thymine (T) at nucleotide position 1283 (1283G >T) of accession number NM_009575 in the affected animals (Fig. 1A–C). The colony has subsequently been maintained via genotyping of this variant, and non-segregation between the phenotype and mutation found in more than 1000 meioses. A further five strains of mice (Mus Castaneus, Mus Spretus, C57BL/6J, 129Sv and 101/H) were analysed and none were found to contain the variant allele, eliminating the possibility that the variant is a naturally occurring polymorphism. The identified base change introduces a PTC at amino acid 249 (E249X) and, if translated, would cause termination of the protein sequence just two amino acids upstream of the zinc finger domain (Fig. 1D).

Fig. 1.

The katun mouse strain carries a mutation in Zic3. (A–C) Sequence traces from exon 1 of the murine Zic3 gene, with arrows indicating the altered base. (A) The parental C3H/HeH and BALB/c OlaHsd alleles have a G at position 1283 of accession number NM_009575. (B) Female carriers of the mutation have a G/T heteroduplex at this position. (C) Male hemizygotes have a G to T transversion at this position. (D) Representation of the Zic3 protein showing the position of the katun (E249X) mutation relative to other protein features, including the C2H2 zinc fingers (dark blue), amino acid repeat regions (blue; A, alanine repeat; H, histidine repeat), the Zic-Opa conserved (ZOC) motif (bright green) and the zinc finger N-flanking conserved (ZF-NC) region (light green).

The katun transcript evades nonsense-mediated decay

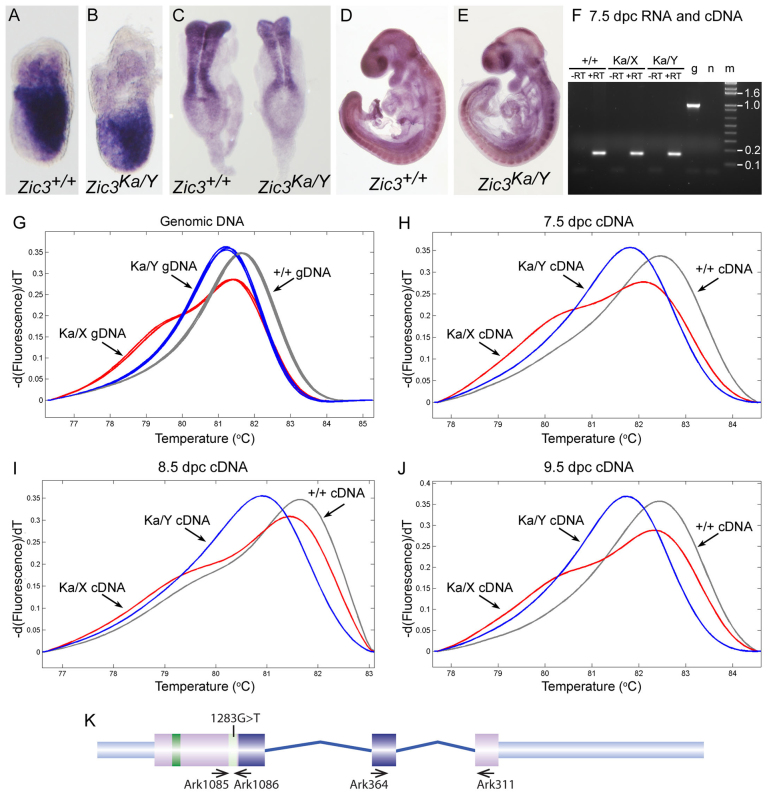

The katun transcript conforms to the rule for NMD (Nagy and Maquat, 1998) and is predicted to be absent from hemizygous null embryos. To determine whether the katun transcript is subjected to NMD we performed whole mount in situ hybridization (WMISH) to Zic3 in wild-type and Ka/Y embryos (7.0, 8.5, and 9.5 days post-conception; dpc). As shown in Fig. 2A–E, Zic3 transcript levels were indistinguishable from wild-type levels in the hemizygous null embryos at all stages examined, suggesting that NMD of the Ka transcript is deficient. To confirm this, allele-specific RT-PCR was performed at each of the embryonic stages examined by WMISH from embryos of all three genotypes (+/+, Ka/X and Ka/Y). The absence of genomic DNA in each sample was confirmed by amplification of an intron spanning fragment from the Zic3 gene. The 162-bp cDNA-specific product was only amplified from cDNA samples synthesized in the presence of reverse transcriptase, whereas the 1006-bp genomic DNA-specific product was absent in all samples (Fig. 2F and data not shown). Allele-specific RT-PCR products were then produced (using exon 1 primers) from each RNA sample and analysed by high resolution melt analysis. In each case, the melt profile of the products obtained from cDNA samples was compared with positive control profiles obtained from genomic DNA of animals of known genotype (Fig. 2G). At 7.5, 8.5 and 9.5 dpc, embryos containing only the mutant Zic3 allele (Zic3Ka/Y) exclusively express the Ka transcript, embryos containing only the normal Zic3 allele (Zic3+/+) exclusively express the wild-type transcript whereas embryos with one mutant and one wild-type allele (Zic3Ka/X) express a mixture of the two transcripts (Fig. 2G–J). The hybridization signal seen in Zic3Ka/Y mutant embryos is therefore due to the accumulation of the Ka transcript. Together, these data indicate that the Ka transcript is not rapidly subjected to NMD during axis formation (the stage at which the Zic3-associated heterotaxy phenotype emerges).

Fig. 2.

The katun PTC-containing transcript accumulates in gastrulation and organogenesis stage mutant embryos. (A–E) Lateral views of embryos after WMISH to Zic3 RNA; embryos are shown with anterior to the left (A,B,D,E) or top (C). (A,B) 7.0 dpc embryos of the genotype indicated on the panel. (C) 8.5 dpc embryos of the genotype indicated on the panel. (D,E) 9.5 dpc embryos of the genotype indicated on the panel. (F) PCR amplification of an intron-spanning product from the Zic3 gene (generated with primers Ark364 and Ark311; expected product size for genomic DNA is 1006 bp and for cDNA is 162 bp) following cDNA synthesis from each of the RNAs used for allele-specific PCR. –RT, without reverse transcriptase; +RT, with reverse transcriptase; g, genomic DNA; n, no template control; m, size marker. (G–J) Melting peak analysis following high resolution melting of Zic3 allele-specific PCR products (generated with primers Ark1085 and Ark1086). The Zic3+/+ DNA melt profiles are shown in gray, the Zic3Ka/Y DNA melt profiles in blue and the Zic3Ka/X profiles in red. (G) Zic3 amplicons after PCR of genomic DNA isolated from three Zic3+/+ mice, three Zic3Ka/X mice or three Zic3Ka/Y mice. (H) Zic3 amplicons after PCR of cDNAs synthesized from 7.5 dpc RNA. (I) Zic3 amplicons after PCR of cDNAs synthesized from 8.5 dpc RNA. (J) Zic3 amplicons after PCR of cDNAs synthesized from 9.5 dpc RNA. (K) Diagram of the murine Zic3 genomic locus showing the location of the mutation and the primers used for allele-specific and intron-spanning RT-PCR.

The mutant protein is stable and accumulates in the nucleus via passive diffusion

The finding of incomplete NMD raises the possibility that the message could be translated into a short-lived, truncated protein with some function. Detection of Zic3 protein in wild-type and katun mutant embryos using SDS-PAGE and western blotting was not successful due to failure of the antibodies to specifically detect endogenous Zic3 (data not shown). Therefore, to determine whether this mutant Zic3 transcript can be translated into a stable protein, either a N-terminal V5-epitope tagged version of ZIC3 (V5-ZIC3-wt) or ZIC3-katun variant (V5-ZIC3-katun) were expressed in cultured mammalian cell lines. Following transfection of COS-7, HEK293T or NIH 3T3 cells a wild-type protein of ∼60 kDa and a katun protein of ∼35 kDa were detected with western blotting using either an anti-Zic3 antibody or an anti-V5 antibody. Both proteins were detected in lysates made 24, 42 and 72 hours post-transfection, indicating that the katun protein is stable (Fig. 3A and data not shown). The predicted sizes of the wild-type and katun ZIC3 proteins are 52 kDa and 27 kDa, respectively, with the difference corresponding to the size of the V5 tag and spacer fragment within the pcDNA3.1/nV5-DEST vector.

Fig. 3.

Truncated katun protein diffuses into the nucleus. (A) HEK293T cells expressing either V5-ZIC3-wt or V5-ZIC3-katun were lysed to generate nuclear (N) and cytoplasmic (C) fractions. Lysates were then subjected to SDS-PAGE and western blotting with anti-V5 antibodies. (B) HEK293T cells expressing V5- or EGFP-tagged ZIC3 constructs were co-immunostained with anti-lamin B antibody (to detect nuclear envelope, in red) and either anti-V5 or anti-GFP antibodies (in green). Overlaid images are shown. (C) HEK293T cells expressing either EGFP-ZIC3-wt or EGFP-ZIC3-katun were lysed and fractionated into nuclear (N) and cytoplasmic (C) fractions. Lysates were then subjected to SDS-PAGE and western blotting with anti-GFP antibodies. (D) Localization of V5-ZIC3-wt or V5-ZIC3-katun in nuclear (gray) and cytoplasmic (black) compartments of HEK293T cells was quantified using ImageJ. *P<0.01 using ANOVA.

The Zic3 protein does not contain a canonical nuclear localization signal but is transported into the nucleus via the importin pathway through cryptic nuclear localization signals within the zinc finger domain (Bedard et al., 2007; Hatayama et al., 2008). The absence of the zinc finger domain in the katun protein is therefore expected to prevent accumulation of V5-ZIC3-katun within the nucleus. As shown in Fig. 3A, subcellular fractionation of transfected cell lysates revealed that a significant proportion of the katun protein was found in the nucleus. To confirm this result and quantify the extent of katun nuclear accumulation, the subcellular localization of V5-ZIC3-katun was compared with that of V5-ZIC3-wt by immunofluorescent staining following transfection into HEK293T cells (Fig. 3B,D). Consistent with previous studies on the subcellular location of Zic proteins (Ware et al., 2004), 88.5% of the wild-type V5-ZIC3-wt protein was found within the nucleus. Strikingly, 61.4% of the mutant V5-ZIC3-katun protein accumulated within the nucleus. This raised the possibility that the N-terminal portion of Zic3 contains sequences sufficient for directed nuclear transport. It is, however, also possible that the small size of the katun protein enables it to diffuse into the nucleus because proteins smaller than ∼40 kDa can diffuse into the nucleus (Wei et al., 2003). To distinguish between these possibilities, the size of the katun protein was artificially increased by fusion with enhanced green fluorescent protein (EGFP). The subcellular localization of EGFP-ZIC3-katun was compared with that of EGFP-ZIC3-wt following transfection into HEK293T cells using western blot and immunofluorescent staining (Fig. 3B–D). Western blot analysis detected EGFP-ZIC3-wt in the nuclear fraction at ∼85 kDa (predicted size, 79 kDa) and EGFP-katun predominately in the cytoplasmic fraction at ∼55 kDa (predicted size, 54 kDa). Immunofluorescent localization analysis found that 88.9% of the EGFP-ZIC3-wt protein was within the nucleus, whereas only 10.3% of the mutant EGFP-ZIC3-katun protein accumulated within the nucleus. The difference between the localization of the V5-ZIC3-katun protein and the EGFP-ZIC3-katun protein suggests that the katun protein accumulates in the nucleus by passive diffusion.

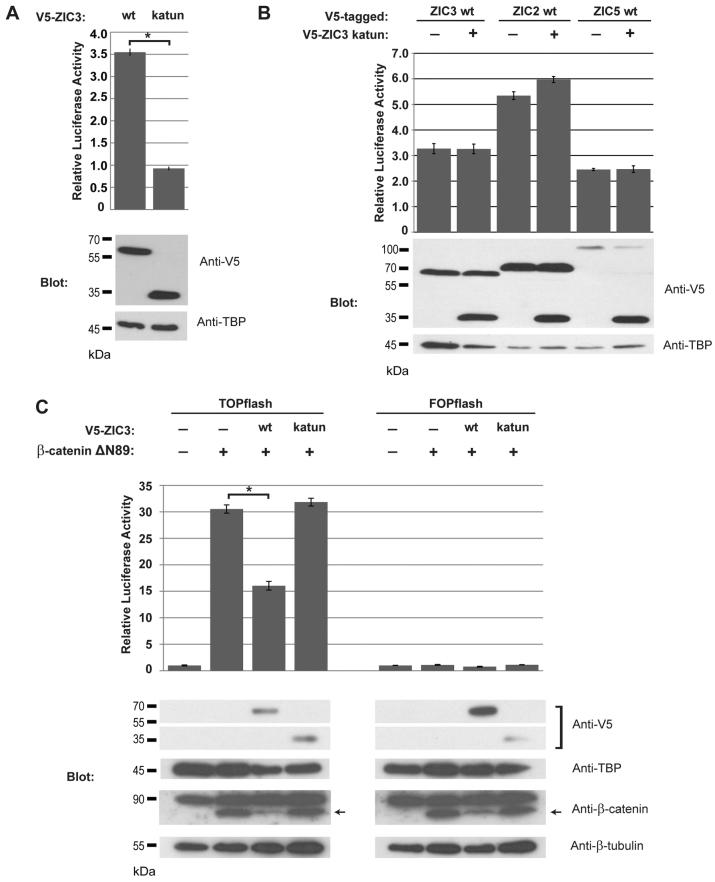

The mutant protein is transcriptionally inactive and does not compete with wild-type ZIC3

Given that the katun protein is stable and localizes to the nucleus, it is possible that the protein exerts some effect. The zinc finger domain is crucial for the trans-activation ability of Zic proteins because deletion of the domain or point mutations within the zinc fingers that disrupt DNA binding leads to proteins that are unable to stimulate transcription (Brown et al., 2005). The ability of V5-ZIC3-katun to stimulate transcription was evaluated using a well-established cell-based Apoe promoter luciferase reporter assay (Salero et al., 2001; Brown et al., 2005). Co-transfection of the Apoe reporter construct with either the V5-ZIC3-wt construct or the V5-ZIC3-katun construct into HEK293T cells followed by quantification of luciferase activity demonstrated that the truncated protein was unable to elicit transcription (Fig. 4A). The comparable expression of each ZIC3 construct was confirmed by SDS-PAGE and western blot (Fig. 4A, Blot). When V5-ZIC3-katun was placed in competition with wild-type ZIC proteins (V5-ZIC3-wt, V5-ZIC2-wt or V5-ZIC5-wt) the trans-activation abilities of the wild-type proteins were not significantly altered (Fig. 4B).

Fig. 4.

The katun protein is functionally inert. (A) Trans-activation assay in HEK293T cells co-transfected with the Apoe reporter construct and the expression plasmids shown. The anti-V5 western blot shows the level of overexpressed proteins and the anti-TBP western blot acts as a nuclear fraction loading control. (B) Competition assay in HEK293T cells co-transfected with the Apoe reporter construct and the expression plasmids shown. The anti-V5 western blot shows the level of overexpressed proteins and the anti-TBP western blot acts as a loading control. (C) Wnt inhibition assay in HEK293T cells co-transfected with either TOPflash or FOPflash reporter construct and the expression plasmids shown. The anti-V5 and anti-β-catenin western blots show the level of overexpressed proteins in the nuclear and cytoplasmic fractions, respectively. The anti-TBP and anti-β-tubulin western blots act as nuclear and cytoplasmic loading controls, respectively. Anti-β-catenin detects both endogenous β-catenin and the smaller exogenously expressed β-catenin-ΔN89 (marked by arrows). Error bars denote s.d. between internal replicates; *P<0.01 using ANOVA.

The mutant protein does not inhibit β-catenin-mediated transcription

The human ZIC2 and Xenopus zic1-5 proteins have recently been shown to act as cofactors that inhibit Wnt-dependent-β-catenin-mediated transcription (Pourebrahim et al., 2011; Fujimi et al., 2012). Upon Wnt stimulation, β-catenin enters the nucleus and interacts with the TCF transcription factors to stimulate transcription of target genes (Behrens et al., 1996). A luciferase reporter construct containing consensus TCF binding sites (TOPflash) or mutated TCF sites (FOPflash) is routinely used to assess Wnt-dependent transcription (Korinek et al., 1997). Co-transfection of the TOPflash construct with one encoding a stabilized form of β-catenin (β-catenin-ΔN89) into HEK293T cells drove high levels of luciferase activity (Fig. 4C) but this level was not attained in the presence of V5-ZIC3-wt. This indicates that human ZIC3, like ZIC2, is able to inhibit β-catenin-mediated transcription of Wnt target genes in cultured HEK293T cells. In addition, when ZIC3 is expressed, lower levels of β-catenin-ΔN89 are detected, which is consistent with the enhanced β-catenin degradation previously seen with the expression of Xenopus zic3 (Fujimi et al., 2012). In contrast to wild-type ZIC3 protein, co-transfection with V5-ZIC3-katun does not decrease luciferase activity, indicating that the katun protein is unable to inhibit Wnt-dependent β-catenin-mediated transcription.

Ka phenocopies a targeted null allele of Zic3

The most definitive test of allele type involves placing the new allele in trans to a known null allele, but this test cannot be performed for X-linked genes. To determine whether the Ka allele of Zic3 behaves as a null mutation in vivo we therefore recovered embryos at gastrulation stages and examined the associated phenotype. The allele of Zic3 that is best characterized at these stages is the targeted null allele of Zic3 (Zic3tm1Bca) (Purandare et al., 2002). Embryos from this strain that are hemizygous or homozygous null have a variable phenotype, with mutant embryos being assigned to three classes. Type I and Type II embryos display aberrant morphology at early and mid-gastrula stages, whereas the Type III embryos are not morphologically abnormal until the end of gastrulation. The Type I and Type II embryos are characterized by defects in the endoderm and mesoderm formed during gastrulation (Ware et al., 2006b). When embryos hemizygous for the Ka allele (Zic3Ka/Y) were recovered at gastrulation a highly variable phenotype was apparent. A proportion of the recovered embryos displayed defects of the distal egg cylinder or of the extra-embryonic/embryonic junction that are characteristic of the Type I and Type II embryos, as described previously (Ware et al., 2006b). 100% of these embryos were of the Zic3Ka/Y genotype.

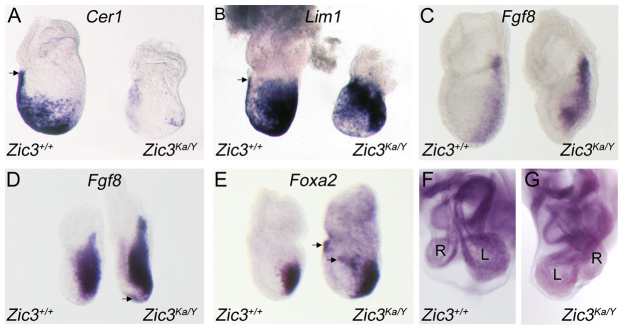

To confirm that the phenotype observed in the Zic3Ka/Y embryos is analogous to that described for embryos from the targeted null allele, WMISH to markers of endoderm and mesoderm formation was performed (a minimum of four embryos were examined per genotype class and probe). Embryos that had morphological defects characteristic of type I mutants were analysed by hybridization to probes to detect Cer1 and Lim1 expression (Fig. 5A,B). At this stage of development, both of these genes are expressed in the anterior visceral endoderm (AVE) at the embryonic anterior (arrows in Fig. 5A,B). This expression was either lacking or markedly reduced in all mutant embryos examined. Cer1 is also expressed in the emerging definitive endoderm and Lim1 is expressed in the wings of developing embryonic mesoderm and this expression was also disrupted in Type I Zic3Ka/Y embryos (Fig. 5A,B). Embryos that had morphological defects characteristic of Type II embryos were analysed by hybridization to probes that mark the primitive streak and emerging wings of embryonic mesoderm (Fgf8 and Foxa2). Consistent with previous analysis (Ware et al., 2006b), Type II embryos exhibited mesoderm abnormalities that included a protrusion of the primitive streak into the amniotic cavity (Fig. 5C) and ectopic expression of mesoderm markers (arrows in Fig. 5D,E). Additional embryos (n=65 Zic3+/+ and n=27 Zic3Ka/Y) were recovered at 9.5 dpc and the heart examined for looping defects indicative of heterotaxy. Consistent with previous analysis of a Zic3 null allele (Ware et al., 2006a), 52% of null embryos exhibited normal hearts (dextral looping, Fig. 5F), 19% exhibited a leftward curve of the heart tube (sinistral looping, Fig. 5G) and the remaining 30% had a heart tube that looped forward (ventral looping) or did not loop at all.

Fig. 5.

The katun mutant embryos have altered primitive streak, mesoderm and endoderm formation. (A–G) All embryos are shown in lateral view, anterior to the left, following in situ hybridization to the RNA named on each panel. (A) Wild-type and type I mutant embryo, 7.0 dpc. (B) Wild-type and type I mutant embryo, 7.0 dpc. Arrows in A and B mark the anterior visceral endoderm (AVE). (C) Wild-type and type II mutant embryo, 7.5 dpc. (D) Wild-type and type II mutant embryo, 7.0 dpc. (E) Wild-type and type II mutant embryo, 7.0 dpc. Arrows in D and E point to regions of ectopic expression of mesoderm markers. (F,G) Developing hearts of 9.5-dpc embryos of the genotype indicated (photographed following in situ hybridization to mRNAs not expressed in the heart; the signal seen is nonspecific). R, right ventricle; L, left ventricle.

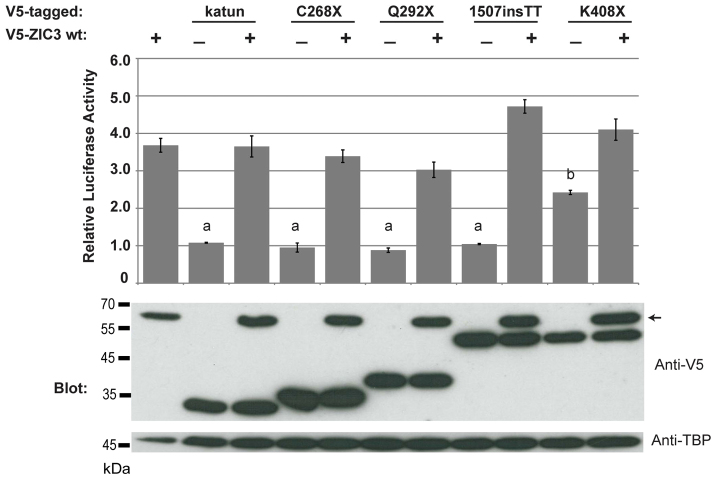

PTC-containing ZIC3 mutant transcripts produce proteins that do not compete with wild-type ZIC3

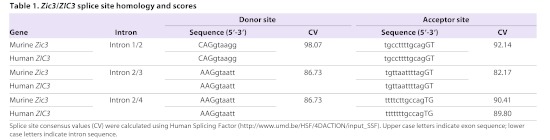

The magnitude of NMD is dependent upon the strength of the splice donor and acceptor sites within an intron, with stronger sites (i.e. those that more closely match the consensus sequence) subject to increased NMD (Gudikote et al., 2005). To assess whether inefficient NMD of the human ZIC3 can be predicted, the mouse Zic3 and human ZIC3 splice sites were compared. As shown in Table 1, the sites are identical (intron 1/2 and 2/3) or nearly so (intron 2/4). Intron 2/3 has the weakest splice signals, as indicated by a lower consensus value score. The absolute conservation of Zic3 and ZIC3 splice sites prompted the examination of the predicted proteins from each of the ZIC3-associated heterotaxy mutations that generate a PTC. Six different ZIC3-associated heterotaxy mutations with a PTC have been previously documented and the protein stability, subcellular localization and transcriptional ability of each of these has been assessed using cell-based assays. Two of these mutations generate unstable proteins (S43X and Q249X) whereas the remaining mutations generate stable proteins that can either be found exclusively in the cytoplasm (C268X and Q292X) or in both cytoplasmic and nuclear compartments (1507insTT and K408X) (Ware et al., 2004). To test whether any of these proteins possess dominant-negative properties, the analogous mutant proteins were expressed in HEK293T in competition with wild-type ZIC3. Expression of each ZIC3 construct was verified by SDS-PAGE and western blot of lysates containing both nuclear and cytoplasmic fractions. Note that the Q249X mutation was excluded from this analysis because it is probably well-modelled by experiments with the V5-ZIC3-katun construct. Our results confirm the finding of Ware and colleagues that the K408X protein retains some trans-activation ability (Ware et al., 2004). Importantly, co-transfection of each ZIC3 mutant construct (V5-ZIC3-C268X, V5-ZIC3-Q292X, V5-ZIC3-1507insTT and V5-ZIC3-K408X) with wild-type ZIC3 (V5-ZIC3-wt) demonstrated that none of the mutant proteins significantly alter the ability of wild-type ZIC3 to activate transcription (Fig. 6).

Table 1.

Zic3/ZIC3 splice site homology and scores

Fig. 6.

ZIC3-heterotaxy-associated mutant proteins do not compete with wild-type ZIC. Competition assay using HEK293T cells co-transfected with the Apoe reporter construct and the expression plasmids shown. The anti-V5 western blot shows the level of overexpressed proteins and the anti-TBP western blot acts as a loading control. Arrow marks the position of V5-ZIC3-wt in the blot. Error bars denote s.d. between internal replicates. a, P<0.01 using ANOVA, compared with V5-ZIC3-wt. b, P<0.001 using ANOVA, compared with V5-ZIC3-wt and other ZIC3 mutants.

DISCUSSION

The katun mouse strain carries a null allele of Zic3

The katun mouse strain arose spontaneously during an ENU-mutagenesis experiment (Bogani et al., 2004). We show here that the identified phenotype (a bent tail) is caused by mutation of the X-linked Zic3 gene. Several lines of evidence indicate that the identified mutation is responsible for the phenotype: (i) the identified base pair change is not a commonly occurring polymorphism; (ii) the variant segregates with the phenotype, being linked through over 1000 meioses to date during maintenance of the colony; (iii) the identified nonsense mutation generates an inactive protein; and (iv) the phenotype precisely recapitulates that documented for a pre-existing null allele of Zic3.

The katun mutation introduces a nonsense codon into the Zic3 transcript that conforms to the rule for PTC recognition in mammalian cells. This provides the first opportunity to investigate the fate of such Zic3 transcripts during mammalian axis formation. WMISH to Zic3 in Ka/Y embryos at gastrulation and early organogenesis stages showed no decrement in Zic3 mRNA accumulation. Allele-specific RT-PCR confirmed that the only transcript expressed in Ka/Y embryos carries the nonsense mutation and that both wild-type and mutant transcripts are present in Ka/X embryos. These data indicate that the Zic3 transcript is a poor substrate for NMD at the time of left-right axis formation and raise the possibility that the Ka mutation does not represent a null allele. Investigations into the molecular properties of the katun mutant protein confirmed, however, that it lacks activities associated with wild-type ZIC3. The katun protein is truncated just two amino acid residues upstream of the zinc finger domain that is required for nuclear localization (Bedard et al., 2007; Hatayama et al., 2008), trans-activation of target gene expression (Koyabu et al., 2001; Mizugishi et al., 2001; Ware et al., 2004) and inhibition of β-catenin-mediated transcription (Fujimi et al., 2012). Although katun can accumulate in the nucleus to appreciable levels (due to passive diffusion rather than active transport), it is transcriptionally inert and does not inhibit β-catenin-mediated transcription.

These data establish that the katun protein is null for the known Zic3 molecular activities, but Xenopus experiments have implied that a similar zic3 protein interferes with the function of wild-type zic3 during axis formation (Kitaguchi et al., 2000). This possibility has not previously been biochemically tested. When the katun mutant protein is placed in competition with either wild-type ZIC3 or the other ZIC molecules coexpressed at the time of axis formation (ZIC2 and ZIC5), it does not interfere with their ability to activate transcription of a target promoter in HEK293T cells. More rigorous evidence that the katun protein does not dominantly interfere with the activity of other Zic proteins comes from the in vivo studies presented here. Experiments that decrease Zic2 activity in a Zic3 null background indicate that these two molecules exhibit partial redundancy during murine axis formation (Inoue et al., 2007). If the katun protein interferes with Zic2 function in vivo then the Ka strain should exhibit a more severe phenotype than other known Zic3 null alleles. Analysis of the phenotype of the Ka/Y embryos shows that it mimics a null allele of Zic3 in several precise details and indicates that that the Ka allele alters the function of Zic3 alone. Together, the phenotype and protein studies demonstrate that Ka encodes a null allele of Zic3 and that the N-terminal portion of mammalian Zic3 does not encode a dominant-negative molecule.

The possibility of incomplete NMD influences the interpretation of ZIC3 PTC-inducing mutations

The finding that the murine Zic3 transcript is a poor substrate for NMD at axis formation suggests that this is also the case for the human ZIC3 transcript. Direct assessment of the fate of human ZIC3 PTC-containing transcripts during axis formation is not possible and predictions regarding the likely NMD behaviour based on the murine transcript provide one alternative. The features that render a transcript a poor target for NMD are not fully characterized. There is, however, evidence that the position of the PTC within the transcript and RNA splicing influences NMD amplitude (Nagy and Maquat, 1998; Gudikote et al., 2005). The genomic arrangement of the murine (Zic3) and human (ZIC3) genes is nearly identical and the splice donor and acceptor sites are completely conserved. It is likely that the human ZIC3 transcript is similarly able to avoid mRNA surveillance mechanisms, which needs to be considered when interpreting the probable effect of ZIC3 PTC-inducing mutations. If PTC-containing transcripts are translated, the two most likely effects are: (i) proteins that truncate downstream of crucial domains might be hypomorphic; and (ii) proteins that do not produce crucial domains might encode dominant-negative molecules.

Six mutations that introduce a PTC into the human ZIC3 transcript have been associated with congenital defects. Four of these adhere to the position rule for NMD (i.e. the PTC is sited more than about 50–55 nucleotides upstream of an exon-exon junction (Nagy and Maquat, 1998). The most 5′-ward of the mutations (C633A) would encode a severely truncated molecule (S43X) if not degraded. Previous examination of this putative protein has shown that it is not stably produced in cell lines (Ware et al., 2004) and is therefore likely to generate a null allele regardless of NMD amplitude. The C1250T mutation would encode the Q249X protein. An expression construct incorporating this mutation into the ZIC3 cDNA has previously been reported to produce no protein (Ware et al., 2004). This PTC lies very close to that generated here in order to mimic the katun protein (E250X), but the katun mutation results in a stable protein. Whatever the reason for the discrepancy between these results, the studies of the katun protein suggest that even if the Q249X protein is generated in vivo it would encode a protein with neither transcriptional Wnt inhibition nor dominant-negative activity. The remaining two mutations (C1338A and C1408T) that conform to the NMD PTC position rule would generate proteins that contain part of the zinc finger domain (C268X and Q292X, respectively). Previous studies indicate that these proteins are transcriptionally inactive and here we confirm and extend this analysis to show that these proteins also fail to dominantly interfere with ZIC trans-activation ability. It seems likely that each of these four mutations would generate a null allele of ZIC3 regardless of NMD amplitude and not result in a composite ZIC phenotype. The remaining two mutations (1507insTT and A1741T) introduce a PTC close to the last intron and, regardless of ZIC3 transcript sensitivity to NMD, are likely to be translated into a stable protein. Here, we confirm that the frameshift protein is transcriptionally inert whereas the K408X protein (corresponding to the A1741T mutation) retains some trans-activation ability. Neither protein is able to interfere with the trans-activation ability of wild-type ZIC. The frameshift mutation therefore appears to generate a null allele whereas the K408X mutation is predicted to be hypomorphic. This conclusion is consistent with the finding of incomplete penetrance for the A1741T mutation (Mégarbané et al., 2000).

In summary, the work presented here confirms the notion that loss of function (partial or complete) of ZIC3 alone is the probable mode of pathology in ZIC3-associated heterotaxy cases that involve PTC-containing transcripts. It implies, however, that ZIC3 PTC-inducing mutations cannot, a priori, be considered to encode a null allele. It is possible that the ZIC3 transcript, like Zic3, is a poor substrate for NMD at the axis formation stage of embryogenesis. Instead, each putative protein needs to be evaluated for its trans-activation ability, co-repressor ability and potential dominant-negative effects. Analysis of the phenotype associated with a murine PTC-containing transcript suggests that the N-terminal portion of the Zic3 protein that lies upstream of the zinc finger does not possess dominant-negative activity and does not interfere with the function of other coexpressed Zic proteins.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Mouse strains and husbandry

Mice were maintained according to Australian Standards for Animal Care under protocol A2011/63 approved by The Australian National University Animal Ethics and Experimentation Committee for this study. The katun (Ka) allele (MGI:3043027) of Zic3 (Zic3Ka) was maintained by continuous backcross to C57BL/6J inbred mice; animals from backcross 10 and beyond were used for analysis. Mice were maintained in a 12-hour light-dark cycle, the midpoint of the dark cycle being 1 am. For the production of staged embryos, 1 pm on the day of appearance of the vaginal plug was designated 0.5 dpc. Genomic DNA was prepared for genotyping as previously described (Arkell et al., 2001) and amplified for high resolution melt analysis using IMMOLASE™ DNA polymerase with TD60 PCR thermal cycling conditions (Thomsen et al., 2012). The Ka mice and embryos were genotyped using the primers Ark1085_F 5′-CCTTCTTCCGTTACATGCG-3′ and Ark1086_R 5′-CTGAGC-CTCCTCGATCC-3′ and sexed using primers Ark1002_F 5′-GAGGTCATGAAGGTCAG-3′ and Ark1003_R 5′-GGGCATAA-ACTTTCCAG-3′.

Mutation detection

Mutation detection was performed by direct sequencing of PCR amplicons from genomic DNA isolated from affected animals and the appropriate parental strains (C3H/HeH and BALB/c OlaHsd) (Bogani et al., 2004). All primers correspond to intron sequence such that coding sequence and intron/exon boundaries were examined for mutations. The oligonucleotides used for sequencing Zic3 were: fragment 1, Ark207_F 5′-TAGGAAAGTTGCAGCTCC-3′ and Ark208_R 5′-ATAGTTAGGGAACTGCGC-3′; fragment 2, Ark209_F 5′-CTACTTGCTCTTTCCTGG-3′ and Ark210_R 5′-TGGTACTGAAAGGTCTCG-3′; fragment 3, Ark211_F 5′-CAGATGCTATGTCCTTCC-3′ and Ark212_R 5′-TTCAAGGT-GTCAGTGCTG-3′; fragment 4, Ark213_F 5′-CTAGGGGTA-TCTATCTCG-3′ and Ark214_R 5′-CTGAGAAAAGGGCAT-AGC-3′.

Whole mount in situ hybridization and cDNA clones

All embryos were dissected from the maternal membranes in PBS with 10% newborn calf serum and staged using morphological criteria (Downs and Davies, 1993). Embryos were fixed overnight at 4°C in 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS. WMISH was carried out according to standard procedures (Wilkinson, 1992; Rosen and Beddington, 1994). Probes for WMISH were as previously described: Zic3 (Elms et al., 2004), Lhx1 (Shawlot and Behringer, 1995), Cer1 (Belo et al., 1997), Foxa2 (Sasaki and Hogan, 1993) and Fgf8 (Mahmood et al., 1995). After completion of the WMISH, embryos were de-stained in PBT (PBS with 0.1% Tween-20) for 48 hours and post-fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS for 1 hour at room temperature. Embryos were processed for photography through a glycerol series (50%, 80% and 100%) and photographed on a glass slide.

RT-PCR

Embryos, dissected and staged, for RT-PCR were individually frozen in 96-well plates on dry ice and stored at −70°C. Upon geno- and sex-typing of the corresponding embryo tissue, the embryos were pooled in three genotype classes (Zic3+/+, Zic3Ka/X and Zic3Ka/Y). Each pool consisted of ten embryos at 7.5 dpc, four embryos at 8.5 dpc and two embryos at 9.5 dpc. Genomic DNA-free RNA was extracted from each sample using the Ambion RNAqueous 4 PCR kit (Life Technologies). RNA concentration was quantified by Nanodrop spectrophotometry and 500 ng of RNA template included in a random primed cDNA first strand synthesis reaction (Superscript VILO cDNA synthesis kit; Life Technologies). A RT negative control synthesis reaction was performed in parallel from each RNA sample. To confirm absence of contaminating genomic DNA in the original RNA samples, amplification from each cDNA sample was performed using primers Ark364 and Ark311 (located in exons 2 and 3, respectively, of Zic3) using Abgene DNA polymerase (with buffer: 10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.3, at 25°C, 50 mM KCl, 1.5 mM MgCl2) and TD60 PCR thermal cycling conditions with an extension time of 45 seconds (Thomsen et al., 2012). PCR products were analysed by agarose gel electrophoresis. Amplification from genomic DNA produces a 1006-bp product whereas that from cDNA results in a 162-bp product. For allele-specific PCR, each cDNA (0.5 μl) was used in the genotyping assay.

Plasmids

All plasmid construction used standard molecular biology procedures. The Gateway® Recombination Cloning Technology (Life Technologies™) was used to generate V5-epitope-tagged expression plasmids. The appropriate cDNA was transferred to the pENTR™3C vector that had been linearized with EcoRI (NEB) and dephosphorylated with Antarctic Phosphatase (NEB) to produce an ‘entry’ clone. Four entry clones were generated as follows.

pENTR™3C-ZIC3-wt: a full length ZIC3 cDNA was recovered from the HA-ZIC3-wt expression plasmid (a gift from Stephanie Ware, Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center, OH) (Ware et al., 2004) by PCR with oligonucleotides Ark1152_F 5′-ATCCGGTACCGAATTCACCCTCTCTCACTTCGG-3′ and Ark1153_R 5′-GTGCGGCCGCGAATTCCCGCTCTAGAAC-TAGTGG-3′. This amplicon was cloned using In-Fusion™ Dry-Down PCR Cloning System (Clontech) into pENTR™3C vector (Life Technologies).

pENTR™3C-ZIC3-katun: the HA-ZIC3-wt plasmid was subjected to site-directed mutagenesis with the QuikChange® II Site-Directed Mutagenesis Kit (Stratagene) using oligonucleotides Ark1006_F 5′-GCCTATCAAGCAGTAGCTGTCGTGCAAGTG-3′ and Ark1007_R 5′-CACTTGCACGACAGCTACTGCTTG-ATAGGC-3′. The ZIC3-katun cDNA was amplified and cloned as for ZIC3-wt into pENTR™3C.

pENTR™3C-ZIC2-wt: a full length ZIC2 cDNA was PCR amplified from pcDNA-ZIC2 (a gift from Maral Mouradian, Robert Wood Johnson Medical School, NJ) (Yang et al., 2000), using oligonucleotides: Ark1150_F 5′-ATCCGGTACCGAATTCAGTG-TGGTGGAATTCCTGGCC-3′ and Ark1168_R 5′-GTGCGGCC-GCGAATTCGAGGGTTAGGGATAGGCTTAC-3′ and cloned into pENTR™3C using the In-Fusion™ Dry-Down PCR Cloning System.

pENTR™3C-ZIC5-wt: a full length ZIC5-wt cDNA was excised from pCMV6-XL5-ZIC5 (Origene) via EcoRI digestion and ligated into pENTR™3C using T4 DNA ligase (NEB). Entry clones for all other ZIC3 mutant plasmids were created via site-directed mutagenesis of pENTR™3C-ZIC3-wt with the QuikChange II Site-Directed Mutagenesis Kit (Stratagene). Primers used to introduce mutations were as follows: pENTR™3C-ZIC3-C268X, Ark1399_F 5′-CGGCCCAAGAAGAGCTGAGACCGGACCTTCAGC-3′ and Ark1400_R GCTGAAGGTCCGGTCTCAGCTCTTCTTGGGC-CG-3′; pENTR™3C-ZIC3-Q292X, Ark1401_F 5′-GTGGGGGG-CCCGGAGTAGAACAACCACGTCTGC-3′ and Ark1402_R 5′-GCAGACGTGGTTGTTCTACTCCGGGCCCCCCAC-3′; pENTR™3C-ZIC3-1507insTT, Ark1403_F 5′-CCGAGTGC-ACACGGGCTTGAGAAGCCCTTCCCA-3′ and Ark1404_R 5′-TGGGAAGGGCTTCTCAAGCCCGTGTGCACTCGG-3′; pENTR™3C-ZIC3-K408X, Ark1405_F 5′-CTGCGCAAACAC-ATGTAGGTTCATGAATCTCAA-3′ and Ark1406_R 5′-TTGA-GATTCATGAACCTACATGTGTTTGCGCAG-3′.

In each case, the inserts from the entry clones were transferred to the destination clone pcDNA3.1/nV5-DEST™ (Life Technologies) via a Gateway® LR Clonase reaction (as per manufacturer’s instructions; Life Technologies) to produce the following plasmids: V5-ZIC3-wt, V5-ZIC3-katun, V5-ZIC3-C268X, V5-ZIC3-Q292X, V5-ZIC3-1507insTT, V5-ZIC3-K408X, V5-ZIC2-wt and V5-ZIC5-wt. To generate the EGFP-tagged ZIC3 constructs, ZIC3 was amplified from HA-ZIC3-wt or HA-ZIC3-katun using the following primers: Ark1208_F 5′-GAGCTCAAGCTTCGAATTCTACCC-TCTCTCACTTCGG-3′ and Ark1209_R 5′-TACCGTCGAC-TGCAGAATTCCCGCTCTAGAACTAGTG-3′. The PCR product was cloned into pEGFP-C1 (linearized with EcoRI and dephosphorylated with Antartic Phosphatase) using the In-Fusion™ Dry-Down PCR Cloning System. The Apoe reporter construct pXP2-Apoe (−189/+1) was a gift from Francisco Zafra (Centro de Biología Molecular, Universidad Autonoma de Madrid, Spain) (Salero et al., 2001). The TOPflash and FOPflash vectors contain four optimal TCF binding sites or four mutant TCF binding sites, respectively, upstream of a minimal c-Fos promoter and luciferase cDNA. These vectors and the pCAN-β-catenin-ΔN89 expression construct (Munemitsu et al., 1996) were a gift from Sabine Tejpar (Molecular Digestive Oncology, Katholieke Universiteit Leuven, Belgium) (Pourebrahim et al., 2011).

Cell culture and transfection

Mammalian cell lines COS-7, NIH3T3 and HEK293T were cultured in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) (Life Technologies), supplemented with 10% (v/v) fetal bovine serum (Life Technologies), 2 mM L-glutamine (Life Technologies) and 0.1 mM non-essential amino acid solution (Life Technologies) at 37°C in humidified air. For transient transfections, cells were transfected with either 0.4–0.6 μg or 3–4 μg of the mammalian expression plasmid DNA using Lipofectamine™ 2000 (Life Technologies) according to the manufacturer’s guidelines.

Immunofluorescence staining, microscopy and quantification of subcellular localization

Cells were prepared for immunofluorescence microscopy as previously described (Kovacs et al., 2002) and viewed using the LSM 5 Pascal (ZEISS) confocal microscope. At least 100 transfected cells per experiment were scored blind as follows. For each cell, the nuclear and cytoplasmic compartment was traced using the Intuos® 2 graphics tablet (Wacom) and the average fluorescence intensity for each compartment of the cell was measured with ImageJ analysis software (NIH). The values from the 100 scored cells were averaged to give the percentage nuclear and percentage cytoplasmic localization for the experiment. Three independent experiments were conducted and the percentage localization in each cellular compartment averaged across the three experiments. For statistical analysis, GenStat (VSN International) was used to perform a nonorthogonal factorial ANOVA. Images were assembled in Adobe Photoshop CS7.

Subcellular fractionation, SDS-PAGE and western blotting

HEK293T cells grown on 35-mm tissue culture dishes or 12-well tissue culture plates (Corning®) were lysed and fractioned into nuclear and cytoplasmic fractions using the NE-PER kit (Pierce) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. CERI and NERI lysis buffers were supplemented with protease inhibitors (complete, EDTA-free protease inhibitor cocktail, Roche). Then, 2 mM DTT (Sigma Aldrich) and 1× NuPAGE LDS Sample Buffer (Life Technologies) were added to nuclear and cytoplasmic fractions and the samples heated for 5 minutes at 90°C. Samples were then loaded onto 8%, 10% or 12% SDS-PAGE gels and run at 100 V. Proteins were transferred to PVDF membranes (Millipore) via wet transfer at 15 V for 16 hours. Membranes were blocked overnight at 4°C with a solution of 5% skim milk powder, PBS and 0.2% Tween 20 (Sigma Aldrich) (western blot blocking buffer) before being immunoblotted using standard western blotting techniques. To detect protein bands, blots were incubated with SuperSignal West Pico reagent (as per manufacturer’s guidelines; Pierce) then exposed to film (Amersham Hyperfilm MP, GE Life Sciences). Developed films were scanned and assembled in Adobe Illustrator CS5.1.

Antibodies

Primary antibodies used were: goat polyclonal anti-Zic3 N-19 (1:500 dilution for western blot; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, sc-28154), mouse monoclonal anti-HA (1:100 dilution for immunofluorescence, 1:4000 dilution for western blot; Sigma, H3663), mouse monoclonal anti-V5 (1:200 dilution for immunofluorescence, 1:3000 dilution for western blot; Life Technologies, R960-25), rabbit polyclonal anti-GFP (1:300 dilution for immunofluorescence, 1:1000 dilution for western blot; Cell Signaling, 2555), rabbit polyclonal anti-Lamin B1 (1:1000 dilution for immunofluorescence; Abcam, ab16048), mouse monoclonal anti-β-tubulin (1:1000 dilution for western blot; Abcam, ab7792), mouse monoclonal anti-TATA binding protein (TBP) (1:2000 dilution for western blot; Abcam, ab818) and goat polyclonal β-catenin C-18 (1:500 dilution for western blot; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, sc-1496). Secondary antibodies used for immunofluorescence (all at 1:500 dilution) were Alexa-Fluor-594-and Alexa-Fluor-488-conjugated donkey anti-mouse, anti-goat and anti-rabbit (Molecular Probes, Life Technologies). Secondary antibodies used for western blot (all at 1:5000 dilution) were horseradish peroxidase-conjugated rabbit anti-mouse, rabbit anti-goat and goat anti-rabbit (Zymed, Life Technologies). All antibodies were diluted in blocking buffer.

Luciferase reporter assays

HEK293T cells grown in 12-well tissue culture plates were transfected with the relevant combination of constructs. For ZIC trans-activation assays, a total of 1.2 μg of DNA was added per well: 0.6 μg of the Apoe reporter construct and either 0.6 μg of the expression construct or the negative control construct, pcDNA3.1/nV5-DEST™. For ZIC competition assays, a total of 1.2 μg of DNA was added per well: 0.4 μg of the Apoe reporter construct, 0.4 μg of the wild-type ZIC expression construct and 0.4 μg of either the competing katun expression construct or the pcDNA3.1/nV5-DEST™ vector when required to equalize the amount of transfected DNA. For the Wnt inhibition assays, a total of 1.5 μg of DNA was transfected per well: 0.5 μg of the TOPflash or FOPflash reporter vectors, 0.5 μg β-catenin-ΔN89 construct and 0.5 μg of the appropriate ZIC3 construct or pcDNA3.1/nV5-DEST™. To assess background Wnt activation levels, one well was transfected with 0.5 μg of the TOPflash or FOPflash reporter vectors and 1 μg of the pcDNA3.1/nV5-DEST™ vector. Either 8 hours (for the ZIC trans-activation and competition assays) or 5.5 hours (for the Wnt inhibition assays) post-transfection, cells were dissociated from the growth surface using 0.05 g/l trypsin (Life Technologies) and plated in triplicate onto a solid white tissue-culture treated 96-well plate (Costar®, CLS3917). To avoid any position bias error of the luminometer, sample order was randomized for each independent experimental repeat. The remaining cells were re-plated for SDS-PAGE and western blot analysis and lysed at the time of the reporter assay. Either 16 (for ZIC trans-activation and competition assays) or 19.5 hours (for Wnt inhibition assays) after re-plating, cells in each well were lysed by incubation with 100 μl of a 1:1 dilution of luciferase substrate (ONE-Glo™ Luciferase Assay System, Promega) with DMEM and the luminescence from each well measured in a GloMax®-96 Microplate Luminometer (Promega). The luciferase activity was normalized to the pcDNA3.1/nV5-DEST™ negative control and the average value and standard deviation calculated from the three internal repeats. At least three independent experiments were performed for each assay, with one representative experiment shown. For statistical analysis, GenStat was used to perform ANOVA with Fischer’s unprotected post ad hoc test.

Acknowledgments

We thank M. Maral Mouradian, Sabine Tejpar, and Francisco Zafra and Stephanie Ware for the gift of plasmids, and Emlyn Williams for assistance with statistical analysis. We also thank Andy Greenfield and Rob Houtmeyers for helpful comments on the manuscript.

Footnotes

COMPETING INTERESTS

The authors declare that they do not have any competing or financial interests.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

J.N.A. and R.G.A. developed the concepts and approach, performed experiments, analysed data and prepared the manuscript. N.W., H.M.W., H.M.B., K.S.B. and A.J.T. performed experiments and analysed data. R.M.A. oversaw the project, developed the concepts and approach, analysed data and prepared the manuscript.

FUNDING

This work was funded by The Sylvia and Charles Viertel Charitable Foundation Fellowship to R.M.A.

REFERENCES

- Ali R. G., Bellchambers H. M., Arkell R. M. (2012). Zinc fingers of the cerebellum (Zic): transcription factors and co-factors. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 44, 2065–2068 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arkell R. M., Cadman M., Marsland T., Southwell A., Thaung C., Davies J. R., Clay T., Beechey C. V., Evans E. P., Strivens M. A., et al. (2001). Genetic, physical, and phenotypic characterization of the Del(13)Svea36H mouse. Mamm. Genome 12, 687–694 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aruga J., Nagai T., Tokuyama T., Hayashizaki Y., Okazaki Y., Chapman V. M., Mikoshiba K. (1996a). The mouse zic gene family. Homologues of the Drosophila pair-rule gene odd-paired. J. Biol. Chem. 271, 1043–1047 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aruga J., Yozu A., Hayashizaki Y., Okazaki Y., Chapman V. M., Mikoshiba K. (1996b). Identification and characterization of Zic4, a new member of the mouse Zic gene family. Gene 172, 291–294 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aruga J., Kamiya A., Takahashi H., Fujimi T. J., Shimizu Y., Ohkawa K., Yazawa S., Umesono Y., Noguchi H., Shimizu T., et al. (2006). A wide-range phylogenetic analysis of Zic proteins: implications for correlations between protein structure conservation and body plan complexity. Genomics 87, 783–792 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bateman J. F., Freddi S., Nattrass G., Savarirayan R. (2003). Tissue-specific RNA surveillance? Nonsense-mediated mRNA decay causes collagen X haploinsufficiency in Schmid metaphyseal chondrodysplasia cartilage. Hum. Mol. Genet. 12, 217–225 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bedard J. E., Purnell J. D., Ware S. M. (2007). Nuclear import and export signals are essential for proper cellular trafficking and function of ZIC3. Hum. Mol. Genet. 16, 187–198 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Behrens J., von Kries J. P., Kühl M., Bruhn L., Wedlich D., Grosschedl R., Birchmeier W. (1996). Functional interaction of beta-catenin with the transcription factor LEF-1. Nature 382, 638–642 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belo J. A., Bouwmeester T., Leyns L., Kertesz N., Gallo M., Follettie M., De Robertis E. M. (1997). Cerberus-like is a secreted factor with neutralizing activity expressed in the anterior primitive endoderm of the mouse gastrula. Mech. Dev. 68, 45–57 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bogani D., Warr N., Elms P., Davies J., Tymowska-Lalanne Z., Goldsworthy M., Cox R. D., Keays D. A., Flint J., Wilson V., et al. (2004). New semidominant mutations that affect mouse development. Genesis 40, 109–117 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown L., Paraso M., Arkell R., Brown S. (2005). In vitro analysis of partial loss-of-function ZIC2 mutations in holoprosencephaly: alanine tract expansion modulates DNA binding and transactivation. Hum. Mol. Genet. 14, 411–420 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carrel T., Purandare S. M., Harrison W., Elder F., Fox T., Casey B., Herman G. E. (2000). The X-linked mouse mutation Bent tail is associated with a deletion of the Zic3 locus. Hum. Mol. Genet. 9, 1937–1942 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chhin B., Hatayama M., Bozon D., Ogawa M., Schön P., Tohmonda T., Sassolas F., Aruga J., Valard A. G., Chen S. C., et al. (2007). Elucidation of penetrance variability of a ZIC3 mutation in a family with complex heart defects and functional analysis of ZIC3 mutations in the first zinc finger domain. Hum. Mutat. 28, 563–570 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Downs K. M., Davies T. (1993). Staging of gastrulating mouse embryos by morphological landmarks in the dissecting microscope. Development 118, 1255–1266 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elms P., Siggers P., Napper D., Greenfield A., Arkell R. (2003). Zic2 is required for neural crest formation and hindbrain patterning during mouse development. Dev. Biol. 264, 391–406 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elms P., Scurry A., Davies J., Willoughby C., Hacker T., Bogani D., Arkell R. (2004). Overlapping and distinct expression domains of Zic2 and Zic3 during mouse gastrulation. Gene Expr. Patterns 4, 505–511 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrero G. B., Gebbia M., Pilia G., Witte D., Peier A., Hopkin R. J., Craigen W. J., Shaffer L. G., Schlessinger D., Ballabio A., et al. (1997). A submicroscopic deletion in Xq26 associated with familial situs ambiguus. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 61, 395–401 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frischmeyer P. A., Dietz H. C. (1999). Nonsense-mediated mRNA decay in health and disease. Hum. Mol. Genet. 8, 1893–1900 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujimi T. J., Hatayama M., Aruga J. (2012). Xenopus Zic3 controls notochord and organizer development through suppression of the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway. Dev. Biol. 361, 220–231 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furushima K., Murata T., Matsuo I., Aizawa S. (2000). A new murine zinc finger gene, Opr. Mech. Dev. 98, 161–164 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garber E. D. (1952). ‘Bent-Tail’, a dominant, sex-linked mutation in the mouse. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 38, 876–879 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gebbia M., Ferrero G. B., Pilia G., Bassi M. T., Aylsworth A., Penman-Splitt M., Bird L. M., Bamforth J. S., Burn J., Schlessinger D., et al. (1997). X-linked situs abnormalities result from mutations in ZIC3. Nat. Genet. 17, 305–308 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gudikote J. P., Imam J. S., Garcia R. F., Wilkinson M. F. (2005). RNA splicing promotes translation and RNA surveillance. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 12, 801–809 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatayama M., Tomizawa T., Sakai-Kato K., Bouvagnet P., Kose S., Imamoto N., Yokoyama S., Utsunomiya-Tate N., Mikoshiba K., Kigawa T., et al. (2008). Functional and structural basis of the nuclear localization signal in the ZIC3 zinc finger domain. Hum. Mol. Genet. 17, 3459–3473 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holbrook J. A., Neu-Yilik G., Hentze M. W., Kulozik A. E. (2004). Nonsense-mediated decay approaches the clinic. Nat. Genet. 36, 801–808 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inoue T., Ota M., Mikoshiba K., Aruga J. (2007). Zic2 and Zic3 synergistically control neurulation and segmentation of paraxial mesoderm in mouse embryo. Dev. Biol. 306, 669–684 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitaguchi T., Nagai T., Nakata K., Aruga J., Mikoshiba K. (2000). Zic3 is involved in the left-right specification of the Xenopus embryo. Development 127, 4787–4795 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klootwijk R., Franke B., van der Zee C. E., de Boer R. T., Wilms W., Hol F. A., Mariman E. C. (2000). A deletion encompassing Zic3 in bent tail, a mouse model for X-linked neural tube defects. Hum. Mol. Genet. 9, 1615–1622 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korinek V., Barker N., Morin P. J., van Wichen D., de Weger R., Kinzler K. W., Vogelstein B., Clevers H. (1997). Constitutive transcriptional activation by a beta-catenin-Tcf complex in APC−/− colon carcinoma. Science 275, 1784–1787 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kovacs E. M., Ali R. G., McCormack A. J., Yap A. S. (2002). E-cadherin homophilic ligation directly signals through Rac and phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase to regulate adhesive contacts. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 6708–6718 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koyabu Y., Nakata K., Mizugishi K., Aruga J., Mikoshiba K. (2001). Physical and functional interactions between Zic and Gli proteins. J. Biol. Chem. 276, 6889–6892 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahmood R., Bresnick J., Hornbruch A., Mahony C., Morton N., Colquhoun K., Martin P., Lumsden A., Dickson C., Mason I. (1995). A role for FGF-8 in the initiation and maintenance of vertebrate limb bud outgrowth. Curr. Biol. 5, 797–806 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maquat L. E. (2004). Nonsense-mediated mRNA decay: splicing, translation and mRNP dynamics. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 5, 89–99 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mégarbané A., Salem N., Stephan E., Ashoush R., Lenoir D., Delague V., Kassab R., Loiselet J., Bouvagnet P. (2000). X-linked transposition of the great arteries and incomplete penetrance among males with a nonsense mutation in ZIC3. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 8, 704–708 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mizugishi K., Aruga J., Nakata K., Mikoshiba K. (2001). Molecular properties of Zic proteins as transcriptional regulators and their relationship to GLI proteins. J. Biol. Chem. 276, 2180–2188 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munemitsu S., Albert I., Rubinfeld B., Polakis P. (1996). Deletion of an amino-terminal sequence beta-catenin in vivo and promotes hyperphosporylation of the adenomatous polyposis coli tumor suppressor protein. Mol. Cell. Biol. 16, 4088–4094 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagy E., Maquat L. E. (1998). A rule for termination-codon position within intron-containing genes: when nonsense affects RNA abundance. Trends Biochem. Sci. 23, 198–199 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neu-Yilik G., Gehring N. H., Thermann R., Frede U., Hentze M. W., Kulozik A. E. (2001). Splicing and 3′ end formation in the definition of nonsense-mediated decay-competent human beta-globin mRNPs. EMBO J. 20, 532–540 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pourebrahim R., Houtmeyers R., Ghogomu S., Janssens S., Thelie A., Tran H. T., Langenberg T., Vleminckx K., Bellefroid E., Cassiman J. J., et al. (2011). Transcription factor Zic2 inhibits Wnt/β-catenin protein signaling. J. Biol. Chem. 286, 37732–37740 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Purandare S. M., Ware S. M., Kwan K. M., Gebbia M., Bassi M. T., Deng J. M., Vogel H., Behringer R. R., Belmont J. W., Casey B. (2002). A complex syndrome of left-right axis, central nervous system and axial skeleton defects in Zic3 mutant mice. Development 129, 2293–2302 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosen B., Beddington R. (1994). Detection of mRNA in whole mounts of mouse embryos using digoxigenin riboprobes. Methods Mol. Biol. 28, 201–208 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salero E., Pérez-Sen R., Aruga J., Giménez C., Zafra F. (2001). Transcription factors Zic1 and Zic2 bind and transactivate the apolipoprotein E gene promoter. J. Biol. Chem. 276, 1881–1888 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sasaki H., Hogan B. L. (1993). Differential expression of multiple fork head related genes during gastrulation and axial pattern formation in the mouse embryo. Development 118, 47–59 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shawlot W., Behringer R. R. (1995). Requirement for Lim1 in head-organizer function. Nature 374, 425–430 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomsen N., Ali R. G., Ahmed J. N., Arkell R. M. (2012). High resolution melt analysis (HRMA); a viable alternative to agarose gel electrophoresis for mouse genotyping. PLoS ONE 7, e45252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ware S. M., Peng J., Zhu L., Fernbach S., Colicos S., Casey B., Towbin J., Belmont J. W. (2004). Identification and functional analysis of ZIC3 mutations in heterotaxy and related congenital heart defects. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 74, 93–105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ware S. M., Harutyunyan K. G., Belmont J. W. (2006a). Heart defects in X-linked heterotaxy: evidence for a genetic interaction of Zic3 with the nodal signaling pathway. Dev. Dyn. 235, 1631–1637 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ware S. M., Harutyunyan K. G., Belmont J. W. (2006b). Zic3 is critical for early embryonic patterning during gastrulation. Dev. Dyn. 235, 776–785 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei X., Henke V. G., Strübing C., Brown E. B., Clapham D. E. (2003). Real-time imaging of nuclear permeation by EGFP in single intact cells. Biophys. J. 84, 1317–1327 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilkinson D. G. (1992). Whole mount in situ hybridisation of vertebrate embryos. In In Situ Hybridisation (ed. Wilkinson D. G.), pp. 75–83 Oxford: IRL Press [Google Scholar]

- Yang Y., Hwang C. K., Junn E., Lee G., Mouradian M. M. (2000). ZIC2 and Sp3 repress Sp1-induced activation of the human D1A dopamine receptor gene. J. Biol. Chem. 275, 38863–38869 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu L., Peng J. L., Harutyunyan K. G., Garcia M. D., Justice M. J., Belmont J. W. (2007). Craniofacial, skeletal, and cardiac defects associated with altered embryonic murine Zic3 expression following targeted insertion of a PGK-NEO cassette. Front. Biosci. 12, 1680–1690 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]