Abstract

Aim of the study

Twitter has over 500 million subscribers but little is known about how it is used to communicate health information. We sought to characterize how Twitter users seek and share information related to cardiac arrest, a time-sensitive cardiovascular condition where initial treatment often relies on public knowledge and response.

Methods

Tweets published April–May 2011 with keywords cardiac arrest, CPR, AED, resuscitation, heart arrest, sudden death and defib were identified. Tweets were characterized by content, dissemination, and temporal trends. Tweet authors were further characterized by: self-identified background, tweet volume, and followers.

Results

Of 62,163 tweets (15,324, 25%) included resuscitation/cardiac arrest-specific information. These tweets referenced specific cardiac arrest events (1130, 7%), CPR performance or AED use (6896, 44%), resuscitation-related education, research, or news media (7449, 48%), or specific questions about cardiac arrest/resuscitation (270, 2%). Regarding dissemination (1980, 13%) of messages were retweeted. Resuscitation specific tweets primarily occurred on weekdays. Most users (10,282, 93%) contributed three or fewer tweets during the study time frame. Users with more than 15 resuscitation-specific tweets in the study time frame had a mean 1787 followers and most self-identified as having a healthcare affiliation.

Conclusion

Despite a large volume of tweets, Twitter can be filtered to identify public knowledge and information seeking and sharing about cardiac arrest. To better engage via social media, healthcare providers can distil tweets by user, content, temporal trends, and message dissemination. Further understanding of information shared by the public in this forum could suggest new approaches for improving resuscitation related education.

1. Introduction

Cardiac arrest is a time-sensitive condition in which immediate cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) provided by bystanders can greatly improve survival.1 Efforts to engage the public in bystander resuscitation are widespread, and have included public awareness campaigns, broadly distributed basic life support training in schools, business, and community groups, and wall mounted automatic external defibrillators (AEDs) in public settings.2–5 Despite these efforts, low rates of bystander CPR, limited utilization of AEDs, and dismal survival rates (median 6.4%) suggest that there is a considerable need for improvement.6–10 While public health education will certainly remain an important part of efforts to improve the extent and quality of bystander CPR, new trends in social media allow us to observe some forms of peer to peer communication about CPR—observations that may help us improve public understanding and action.

Twitter (http://www.twitter.com) is a free social networking platform that allows users to communicate via 140 character messages called “tweets.”11 An individual “tweeter” may “tweet” a short message, which will be received on a desktop or handheld device by anyone who subscribes to that person’s tweets. With few exceptions, nearly anyone with Internet access can tweet, and nearly anyone can subscribe to that individual’s tweets. Some tweeters, because of who they are or the content of their tweets, can have large followings. Because tweets that are received can be re-tweeted, some tweets can propagate rapidly and broadly. At this writing, Twitter has more than 500 million registered users and distributes over 200 million tweets per day.12 Although the sociodemographic characteristics of Twitter users does not completely represent the general population in the United States (US), the community of Twitter users is diverse and rapidly evolving: in 2011, Twitter was used by 13% of all Internet users over the age of 18, with consistently higher adoption rates among Black (25%) and Hispanic (19%) Internet users compared with Whites (9%), and by those with college degrees (16%) compared with those with high school diplomas (8%).13

Because Twitter messages can be publicly viewed and searched, they offer an opportunity to observe and describe one form of person to person communication, revealing message content and reach. Prior reports have primarily focused on how Twitter can be used for public health surveillance.14–16 Several have used Twitter to track disease activity and public concern during the H1N1 pandemic in 2009.17,18 Twitter has also been used to monitor attitudes toward influenza vaccination efforts.19 Further, researchers have documented how Twitter proved useful in tracking and determining the source of the 2011 Haitian cholera outbreak.20 Further, this suggests that Twitter has the potential to inform and educate public health education efforts in novel ways. Twitter can identify current knowledge deficiencies (areas that require education), identify key “social influencers” measured by twitter networks (e.g. followers) and tweet penetration (e.g. retweets), and evaluate the success of public education campaigns.21–23

Despite the potential for Twitter, little is known however about the prevalence or type of messages shared on Twitter related to resuscitation and cardiovascular health, topics of major public health significance. Given the central importance of the public in initiating pre-hospital resuscitation for cardiac arrest, we sought to characterize cardiac arrest and resuscitation related public conversation on Twitter by analyzing both tweets (content, dissemination, temporal trends) and the users posting tweets.

2. Methods

This was a retrospective review of publicly available tweets posted on Twitter. Tweets can take many forms, including statements, questions, responses, pictures, and web links. Users can choose to make their tweets available to the general public, or only to specific pre-approved users. Upon logging in to Twitter, users can read the updated real-time stream of tweets written by users they follow or posted by others about a specific topic.11 Tweets can also be directed to the attention of specific followers by using either a preset list of users with shared interests or by using the “@” symbol followed by the username of the recipient and then the tweet directed to that user (e.g. @<Username> <tweet content>). Users can also propagate tweets generated by the users they follow using the “retweet (RT)” function. “Retweets” then appear with “RT” preceding them (e.g. RT <tweet content>). Topics of particular interest can be identified by searching tweets for keywords or usage of specific terms preceded by a hashtag (e.g. #[term]). Twitter users create hashtags organically to help categorize common themes among tweets.

2.1. Study design

A Twitter search engine was used to identify publically available tweets posted April 19–May 26, 2011. Tweets with the following keywords: cardiac arrest, CPR, AED, resuscitation, heart arrest, sudden death, and defib were downloaded daily for the study time frame. Keywords were determined by author consensus and a review of tweets identified using cardiac arrest as a search term, one week prior to study initiation.

2.2. Tweet categorization

Using the above keywords, a randomly selected 1% sample of identified tweets was initially reviewed independently by three study investigators (JB, NZ, RM) to determine tweet categories. Using these categories, all tweets were then independently reviewed by these investigators.

Tweets were first categorized as either related or unrelated to cardiac arrest/resuscitation. Tweets identified as unrelated to cardiac arrest/resuscitation (e.g. extraneous content, non-sequiturs) were categorized as miscellaneous. For example, “Check out the train schedule at the CPR, Canadian Pacific Railway website.” Tweets were excluded if they contained non-English words or terms.

Tweets considered to relate to cardiac arrest/resuscitation were categorized as: (1) cardiac arrest [personal or information sharing], (2) CPR [personal or information sharing], (3) AED [personal or information sharing], (4) cardiac arrest/CPR/AED [information seeking], (5) resuscitation education/research/news media.

Personal information sharing referred to messages that appeared to be directly related to a personal experience and included pronouns such as “I,” “my,” or “our.” For example, “My relative just had a cardiac arrest and is now en route to the hospital.” Tweets classified as general information sharing lacked a personal focus and included words such as “you,” “others,” or “the public.” For example, “5 things you should know about automated external defibrillators in schools are at this website.” Tweets containing questions were categorized as information seeking. For example, “Which hospitals provide cooling therapy for cardiac arrest patients?”

Tweets in categories 1–5 above were considered the final study cohort. Tweets of uncertain categorization were reviewed and discussed by three study investigators (JB, NZ, RM) for final adjudication. Inter-rater reliability for tweet categories assigned by study investigators (JB, NZ, RM) was assessed using the kappa statistic; k = 0.78).

2.3. Tweet volume

To assess the volume of cardiac arrest/resuscitation related tweets in the study time frame, tweets were numbered and summed by search term, and then by assigned category (1–5 above).

2.4. Tweet dissemination

To quantify dissemination of resuscitation-specific messages, the number of messages in the final study cohort that were retweeted was evaluated. These messages were identified as having content preceded by the letters “RT.” Tweets containing a search term with a preceding hashtag (#) were also identified to quantify how often tweets contained labels that would allow others searching for resuscitation related content to locate these messages.

2.5. Tweet temporal trends

The day of the week of each tweet in the study cohort was recorded to determine when resuscitation related tweets were occurring and periods of high and low volume. Weekday was defined as Monday through Friday, and weekend was considered Saturday and Sunday. Tweet themes on high volume days were reviewed and reported.

2.6. Tweeter characterization

The number of tweets per user in the study time frame was assessed to characterize the users posting tweets in the study cohort and identify high volume tweeters. Tweeters in the top decile were considered high volume. For this group, data from their publicly posted profile were evaluated to determine their number of followers and if they self-identified as having a professional connection with health care as a provider, educator, researcher, or organization.

2.7. Statistical analysis

Summary statistics were used to describe tweets by search term (cardiac arrest, CPR, AED, resuscitation, heart arrest, sudden death, defib) and category (cardiac arrest/CPR/AED personal or general information sharing, information seeking, resuscitation related education/research/news media, or miscellaneous). To evaluate resuscitation-specific tweet temporal patterns, tweets were characterized by day of the week. Median tweets per day were determined.

Summary statistics were used to characterize users and user characteristics, volume of tweets, and potential influence (i.e. number of followers). All statistical analyses were performed with Stata version 10, College Station, TX. The institutional review board of the University of Pennsylvania approved this study.

3. Results

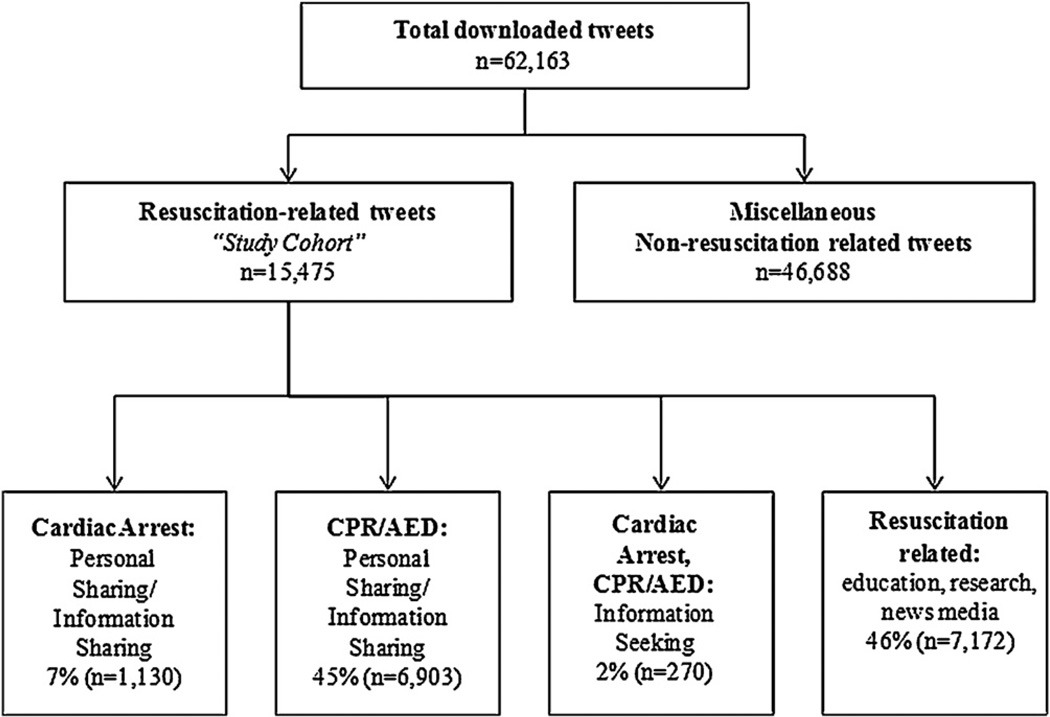

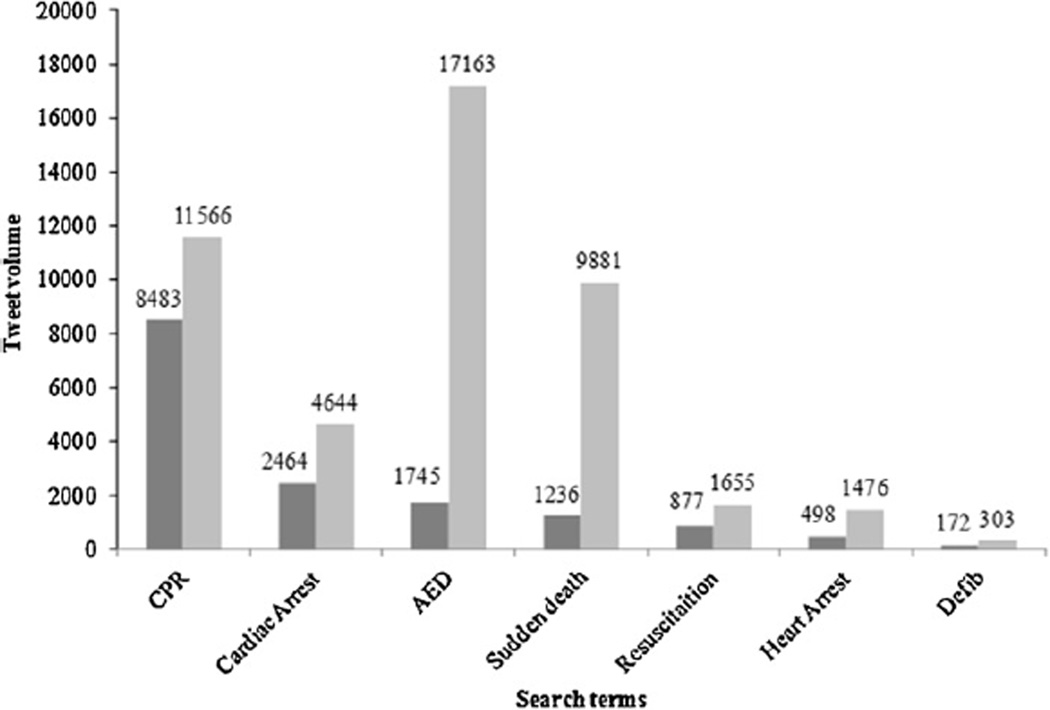

Using seven search terms, we identified 62,163 tweets in the 38- day study time frame. Many of these tweets (15,324, 25%) contained actual resuscitation/cardiac arrest-specific information (Fig. 1) and these were considered the final study cohort. The categorization of tweets by search term is shown in Fig. 2.

Fig. 1.

Flow diagram of the cardiac arrest/resuscitation tweet study cohort. This figure illustrates the tweet categories identified from all downloaded tweets.

Fig. 2.

Tweets identified by search term. This figure illustrates the total tweets identified by search term. The light gray bars represent tweets identified per search term for the entire sample. The dark gray bars indicate the tweets identified per search term for the study cohort of actual resuscitation specific content.

3.1. Tweet content

The distribution of tweet categories is shown in Table 1, along with example tweets: (1130, 7%) tweets referred to cardiac arrest events, 6896 (44%) referred to CPR/AED performance/ use, and (7449, 48%) referred to resuscitation related education/research/news media.

Table 1.

Characterization of resuscitation related tweets by category.

| Category n (%) | Description | Example tweets |

|---|---|---|

| Cardiac arrest (n = 1130) | ||

| Personal sharing 323 (2%) | Tweet shares information about a cardiac arrest event with presumed personal significance to the tweeter | “@[user] my dad went under cardiac arrest and is in icu” |

| “@[user] I can’t even imagine my mom was 51 just made 51...fighting cancer...but she had a bloodclot on her lung..it burst. Cardiac arrest.” | ||

| “Being a part in saving a patient with cardiac arrest just made my day:’)” | ||

| “Heading to VA hosp. 2 visit Dad. Had full cardiac arrest last mo. Looks like he’ll see his 90th B’day on May 2. All there mentally. Pray.” | ||

| Information sharing 802 (5%) | Tweet shares general information about a cardiac arrest event | “A 33 yr old Tennessee woman’s Heart Stopped for 5 mins at Gaga concert, as she went into cardiac arrest..her temp dropped to 86 deg.:/” |

| “Chief: cops helped save man in cardiac arrest – msnbc.com [link] #hashtag #hashtag | ||

| “3 kids struck by lightning in [location] when playing soccer. 1 or 2 went into cardiac arrest but now revived and being taken to hospital.” | ||

| “22-year old goalkeeper dies of cardiac arrest. 22? That’s the youngest I’ve heard so far.” | ||

| “cardiac arrest now at [address]” | ||

| CPR/AEDa,b(n = 6903) | ||

| Personal sharing 4687 (30%) | Tweet shares information about CPR or AEDa,b use with presumed personal significance to the tweeter | “@[user] I just got my CPR/AED, was the AHA Heartsaver CPR/AED course, was in a classroom, hands on, all that. Cost $55” |

| “@[user] I’m doing cpr at my school:p” | ||

| “@[user] things have changed since I took it. Daughter just did lifeguard training and got certified. We all should learn or relearn CPR.” | ||

| “Class went late:(now at least I know first aid, cpr for infants, children, & adults with the AED... I could never be an MD in the ER!” | ||

| “So not only am I CPR certified, but I think I can handle an AED now. Those things are cool and if they weren’t a grand I’d get one for home!” | ||

| Information sharing 2216 (14%) | Tweet shares information about CPR or AEDa,b use without personal significance to the tweeter | “CPR has changed... oh great” |

| “They say doing CPR outside of the hospitals work 7% of the time! WTH!” | ||

| “Updated First Aid/choking/CPR chart now available u should check it out” | ||

| “@[user] AEDs are awesome and provide the ability to actually save a life, unlike CPR which generally just delays death.” | ||

| “There is a lot of AED units @ [amusement park]” | ||

| “@[user] That’s the ratio. 30 breaths, two compressions to essentially act as their heart till a defib arrives.” | ||

| Cardiac arrest and CPR/AEDa,b | ||

| Education, research, news media (n = 7172) | Tweet shares information about cardiac arrest, resuscitation, CPR, or AEDsa,b related to education, research, or a news media link | ““Young Tennis Players Could Be At Risk For Sudden Cardiac Arrest” [news link] With no real symptoms, this is a serious matter” |

| “#news: Improving survival after out-of-hospital cardiac arrest [news link]” | ||

| “Prepared for cardiac emergencies? Learn CPR/AED skills FREE CPR Saturday April 30 [news link] Bring friends + family!” |

CPR indicates cardiopulmonary resuscitation.

AED, automated external defibrillator.

Of tweets referencing cardiac arrest events (n = 1130), [323, 29%] represented personal sharing (e.g. “when I or a family member/ friend had a cardiac arrest”) and (807, 71%) represented general information sharing.

Of tweets referencing CPR/AED use (n = 6896), most [4687, 68%] represented personal sharing (e.g. actual or classroom provision of CPR/AED, likes/dislikes regarding CPR/AED courses) and (2216, 32%) represented general information sharing (e.g., observation of CPR delivery or AED use, commentary regarding hands-only CPR).

Of tweets referencing resuscitation specific education/ research/news media articles (n = 7172), the content primarily related to advocacy group events, heart health surveys, research publications, and news reports of celebrities, athletes, and young adults affected by cardiac arrest.

Some (270, 2%), tweets included resuscitation-specific questions and were characterized as “information seeking.” These inquiries were distributed across the study time period with a mean 4.8 questions daily. Of these tweets, (122, 45%) were questions directed at specific users via “@” tags while the remaining (148, 55%) were questions posed more generally to the public. Regarding information-seeking questions, (86, 32%) inquiries were related to CPR education, training, and certification, (27, 10%) to clarifications about definitions for resuscitation related terms or acronyms such as CPR and AED, and (16, 6%) represented queries about if others knew how to perform CPR or use an AED. Few (13, 5%), questions represented users seeking clarification about signs, symptoms, or risk factors for cardiac arrest and sudden death. There were also (13, 5%) tweets from users seeking subjective opinions or advice, such as how to cope after sudden cardiac death events. Example tweets are listed in Table 2.

Table 2.

Characterization of resuscitation related tweet questions (i.e. information seeking tweets).

| Category n (%) | Description | Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Definition 27 (10%) | Tweet seeks definition or meaning of unknown terms | “what’s aed?” |

| “CPR? Whats that? Sorry:P” | ||

| “It would be cool if i knew what cardiac arrest was” | ||

| Skill knowledge 16 (6%) | Tweet contains question about general knowledge of CPR, AED,a,b and resuscitation. Excludes tweets on education and training classes. | “do you know cpr?” |

| “Anyone AED certified? I may need it.” | ||

| “Who knows about continuous chest compression CPR?” | ||

| Follow-up 39 (14%) | Tweet seeks clarification or further information on a presumed past event involving resuscitation | “@[user] what!!! When did u have cardiac arrest?” |

| “where was this code? What level of EMS? General practice is to continue CPR, as long as AED shocks stay on scene then call ERP.” | ||

| “I really don’t want to see the footage... but are there any more updates on [person] after the CPR?” | ||

| Education and training 86 (32%) | Tweet seeks information related to CPRa training or certification. Includes questions on time, location, participants, price, materials | “@[user] where you do your CPR classes at and how much?” |

| “@[user] you going to cpr training??” | ||

| “Who wants to take a free cpr training class with me at [location]?” | ||

| “@[user] Did they send you home with one of the creepy CPR babies?” | ||

| Procedure, technique, or use 17% (46) | Tweet seeks information on resuscitation procedure or technique or use. Includes questions on efficacy and portrayals of CPRa on television | “How long can u give a person cpr before u pronounced them dead?” |

| “CPR is one breath for every five compressions again??” | ||

| “If the person is having a cardiac arrest, do you do CPR, or just CR?” | ||

| “Why do they never do CPR properly on Tv?” | ||

| Symptoms and risks 5% (13) | Tweet seeks clarification on signs, symptoms, and risk factors for cardiac arrest or sudden death | “anyone knows what a heart attack feels like? I may be going into cardiac arrest; my chest feels all tight.” |

| “Is it normal that the stress of this week is giving me pre-signs of cardiac arrest? Cant breathe” | ||

| “I have high blood pressure and pretty much in under control. Can I still get heart attack or cardiac arrest?” | ||

| Advice and opinion 5% (13) | Tweet seeks subjective advice or personal opinions that does not fall into the above categories | “Should I Buy a Used or New AED? [link]” |

| “tell me how to cope with all these sudden death around especially when I’m not there for them.” | ||

| “What are some good ideas for some fund raisers. My sister in law’s sister went into cardiac arrest two weeks ago? [link]” | ||

| Jobs or services 3% (7) | Tweet queries about work or occupation related topics | “...Looking for a Babysitter?: I am a First Aid/CPR certified nanny looking for full-time summer work” |

| “...Childcare opening: I have an opening for a child starting the first week of June. I am cpr first aid certified | ||

| Data and facts 4% (10) | Tweet poses a question involving objective information that does not fall into the above categories | “@[user] is this value worldwide or just in america. I think more than 90 percent of my patients don’t survive a cardiac arrest.” |

| “a few statistical questions about sudden cardiac arrest? What... [link] #hashtag” | ||

| “@[user] What’s the most common cause of sudden death in athletes >30? Nevermind. One sudden death thingie per year is good enough!:)” |

CPR indicates cardiopulmonary resuscitation.

AED, automated external defibrillator.

3.2. Tweet message dissemination

As an indicator for message dissemination, we evaluated retweeting and use of hashtags. Of the study cohort (1980, 13%) represented retweets. The most frequently retweeted messages related to education about cardiac arrest mortality and news reports about celebrities affiliated with adult and pediatric cardiac arrest events (Table 3). Few (307, 2%) messages contained hashtags. Of this group, “#CPR” (209, 68%) was the most common.

Table 3.

Retweets by category.

| Category | Retweets, n(%) | Examples of frequently retweeted tweets |

|---|---|---|

| Cardiac arrest | ||

| Personal sharing (n = 323) | 19 (6%) | “RT @[user]: just saw a man receiving resuscitation on the side of the [interstate] a mile from [town]. Hope he’s ok.” |

| “RT @[user]: Hi guys! Pls say a prayer for our dear friend [name] of [town] who’s in a coma right now following a cardiac arrest:(” | ||

| “RT @[user]: #[hashtag] our team doctor [name] saved a life today at the [name] track meet. [name] coach went into cardiac arrest. [name] & staff saved him # hashtag” | ||

| Information sharing (n = 802) | 136 (17%) | “RT @[user]: All of our thoughts & prayers are with @[celebrity] after he suffered cardiac arrest yesterday in [city]. He’s still hospitalized there” |

| CPR/AEDa,b | ||

| Personal sharing (n = 4687) | 28 (<1%) | “RT @[user]: #[hashtag] In my opinion – All practices MUST have a maintained defib, training & an emergency plan [link]” |

| Information sharing (n = 2216) | 92 (4%) | “RT @[user]: LOVE that the ideal tempo to perform CPR is 100 bpm aka the tempo of “Stayin’ Alive” by The BeeGees OR “Another One Bites the Dust” by Queen” |

| Cardiac arrest and CPR/AEDa,b | ||

| Information seeking (n = 270) | 8 (3%) | “RT @[user]: Who’s ready for Easter? We sure are, but what if someone chokes at your family meal? Do you know CPR? Get trained! [link]” |

| “RT @[user]: Anyone know of a place in Charlotte that a free class on CPR could be held? Please let @[user] know. (Pls RT)” | ||

| Cardiac arrest and CPR/AEDa,b | ||

| Education, research, news media(n = 7172) | 1692 (24%) | “RT @[news org] The answer to this week’s Myth or matter-of-fact question, Only 10% of people survive cardiac arrest. [link]#hashtag” |

| “RT @[news org]: 9-Year-Old Boy, [name], Saved Sister With CPR, Congratulated by Movie Producer @[user]: [link]” | ||

| “RT @[user]: [name] used defibrilator & perf CPR on unresponsv 3-mo-old girl at [intersection name] crash on [street] this morn. She regained pulse & @ [hospital name] ICU.” | ||

| “RT @[user]: Helicopter is flying in to take [celebrity athlete], who is not responding to CPR. #hashtag” |

CPR indicates cardiopulmonary resuscitation.

AED, automated external defibrillator.

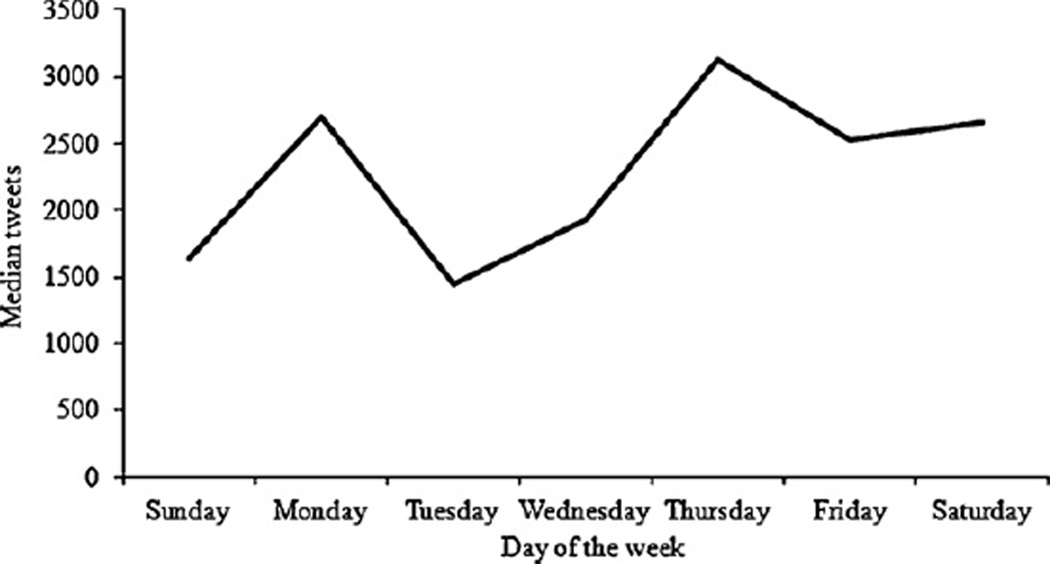

3.3. Tweet temporal trends

Most tweets were posted during the week: Mondays, Thursdays, and Fridays (Fig. 3). During the study time frame, there were three distinct increases in resuscitation-specific tweet volume. These were related to mainstream media stories about the successful use of an AED to revive a fan at a Lady Gaga concert in Tennessee; the story of a 9-year-old boy saving his sister using CPR emulated from watching the Jerry Bruckheimer movie “Blackhawk Down”; and the use of CPR on the United Kingdom based television show “Dr. Who.”

Fig. 3.

Median cardiac arrest/resuscitation related tweets by day of the week. This figure represents median tweets by day of the week. Day of the week is on the x-axis and median tweets are on the y-axis.

3.4. User (tweeter) characteristics

A total of 11,036 users contributed resuscitation relevant tweets; (8856, 80%) contributed a single tweet, (1426, 13%) contributed two tweets, and (714, 6%) contributed 3–10 tweets. A small group of (40, 0.4%) users contributed more than 10 tweets. The top decile of tweeters had a mean 1787 followers (range: 54–6759) and most (37, 95%) self-identified in their profiles as healthcare providers, emergency responders, or medical device manufacturers.

4. Discussion

This study has four main findings. First, the public is using Twitter to both seek and share a wide variety of information about cardiac arrest and resuscitation. Prior work has primarily focused on Twitter as a surveillance tool or means for data tracking in public health disasters and emergencies.14,17,18,24 This study found that Twitter users discussed a wide variety of topics related to cardiac arrest and resuscitation including symptoms, risk factors, personal experiences, training, education, news media events, research articles, cardiac arrest/AED locations, fundraising opportunities, conference notifications, and screenings.

Second, considering the large volume of tweets (200 million per day) our findings also demonstrated that Twitter can be mined to identify resuscitation related content. Using seven search terms, 25% of the reviewed content was identified to be relevant to resuscitation/ cardiac arrest. While much of the content on Twitter is related to non-healthcare topics, our findings demonstrate that Twitter can be used to identify a “signal among the noise.” This suggests that Twitter can be used to better understand how not just cardiac arrest, but other cardiovascular health related information is being disseminated and discussed. Further, considering that Twitter is publicly available, this tool is readily accessible for scientific evaluations of other medical topics. There is already a presence of physicians on Twitter who actively discuss medical information and new literature.25–27

Third, the public will propagate resuscitation related messages through retweeting. Previous reports suggest that an estimated 2% of messages are retweets on the broader Twitter platform.28 However, in our study, retweets represented 13% of resuscitation related. This suggests that the public may be more likely to disseminate previous resuscitation and cardiac health information than generate original content, which presents a new opportunity for healthcare professionals to engage in the social media health community through the creation of targeted messages for propagation.

Fourth, an additional finding is that Twitter may serve as a window into one part of public interest and communication in health in real time. Our study adds to the current literature in demonstrating how Twitter can identify knowledge and concerns about individual public health issues, how communication is stimulated by public circumstances and propagated through social networks.

A few tweets in the study cohort were identified as question-containing or information-seeking. This subset represents an important piece of the overall conversation because these public questions could pave the way for other individuals or organizations to respond. The regular screening of such questions could provide a unique opportunity for health professionals to reach, respond to, and educate a community of online individuals.

Prior data suggests that tweeting behavior differs depending on the day of the week and the time of day.25 As illustrated with non-health related topics, tweet spikes also coincided with mass media events.29 Monitoring these and other temporal patterns could then help maximize efforts to share validated information and provide context for ideal times for tweeting new content or disseminating previously published content.

Finally, previous studies have also shown that the health-related traffic on Twitter is a mix of individuals and organizations.8 In our study, we found that while most users contributed single tweets, those who tweeted frequently (15 or more tweets during the study time period) were often self-identified as having an affiliation with the healthcare field (e.g. medical providers, emergency responders, or medical device manufacturers). These high-volume users had a substantial number of followers—this supports the idea that healthcare professionals are an important part of the online health conversation. Fostering physician and healthcare professional involvement in social media to disseminate valid health information may be beneficial in supporting public health interventions routed through social media.

The options for using Twitter for future research are vast and include applications that would allow for real time promotion and analysis of targeted messaging (e.g. CPR education campaigns), the use of GIS to identify areas of high cardiac arrest through the use of social media influencers, and many others.

4.1. Limitations

This study has several limitations. First we analyzed only publicly available tweets and were unable to access tweets by users who elected to make their content private and accessible only to pre-approved contacts. Nevertheless, our purpose was to view the transmission of information across publicly accessible channels, the same ones that would be used if Twitter were deployed in a messaging campaign. Second, the search terms selected may not include all of the words used by the lay public when discussing cardiac arrest and resuscitation (e.g. heart attack, heart stop, heart thump, chest compression). We did not however, uncover a prevalence of alternate terms within our study cohort. Third, tweet days of the week were reported relative to the time frame of the authors which may differ from the time zone of the tweet. Unless specifically stated in the tweet, the time zone of the tweeter is not able to be definitively determined. No comprehensive measures exist to determine when tweets are actually read or baseline temporal trends for all tweets. This study provides insights about when resuscitation specific tweets could be posted relative to day of the week of the study authors (eastern standard time). Third, we sampled over a limited time frame. Given the rapid evolution of social media, it will be instructive to repeat these analyses in several years. Finally, although Twitter users are a large and growing number, they are not representative of the general population in the US or elsewhere. A disadvantage of Twitter is its unrepresentative scope. An advantage is that it allows researchers access into person to person communication that would otherwise be out of reach.

5. Conclusion

This study represents an initial step in understanding the intersection of social media and public health as it relates to resuscitation science. We illustrated that Twitter messages can be collected and analyzed to better understand the public’s thoughts and feelings about cardiac arrest and resuscitation. These messages can also be identified to characterize the reach of public health information that is derived organically. These analyses may help shape organized public health messages designed to improve resuscitation or other cardiovascular health goals.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding

Grant/research support: NIH, K23 grant 10714038 (Merchant).

The funding source did not play any role in the study design, in the collection, analysis and interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Footnotes

A Spanish translated version of the summary of this article appears as Appendix in the final online version at http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.resuscitation.2012.10.017.

Conflicts of interest statement

Merchant: Grant/research support: NIH, K23 grant 10714038, Pilot funding: Physio-Control Seattle, Washington; Zoll Medical, Boston MA; Cardiac Science, Bothell, Washington; Philips Medical Seattle, Washington.

Becker: Speaker honoraria/consultant fees: Philips Healthcare, Seattle, WA. Institutional grant/research support: Philips Healthcare, Seattle, WA; Laerdal Medical, Stavanger, Norway; NIH, Bethesda, MD; Cardiac Science, Bothell, Washington.

Asch: US Government employee, no conflicts to disclose.

Bosley, Zhao, Hill, Shofer: None, no conflicts to disclose.

References

- 1.Cummins RO, Ornato JP, Thies WH, Pepe PE. Improving survival from sudden cardiac arrest: the “chain of survival” concept. A statement for health professionals from the advanced cardiac life support subcommittee and the emergency cardiac care committee, american heart association. Circulation. 1991;83:1832–1847. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.83.5.1832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Berg RA, Hemphill R, Abella BS, et al. Part 5: adult basic life support: 2010 american heart association guidelines for cardiopulmonary resuscitation and emergency cardiovascular care. Circulation. 2010;122:S685–S705. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.970939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Caffrey SL, Willoughby PJ, Pepe PE, Becker LB. Public use of automated external defibrillators. New Eng J Med. 2002;347:1242–1247. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa020932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mancini ME, Soar J, Bhanji F, et al. Education I. Teams Chapter C. Part 12: education, implementation, and teams: 2010 international consensus on cardiopulmonary resuscitation and emergency cardiovascular care science with treatment recommendations. Circulation. 2010;122:S539–S581. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.971143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bobrow BJ, Spaite DW, Berg RA, et al. Chest compression-only cpr by lay rescuers and survival from out-of-hospital cardiac arrest. JAMA. 2010;304:1447–1454. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.1392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McNally B, Robb R, Mehta M, et al. Centers for disease C, prevention. Out-of-hospital cardiac arrest surveillance—cardiac arrest registry to enhance survival (cares), united states, october 1, 2005–december 31, 2010. Morbidity and mortality weekly report. Surveill Summ. 2011;60:1–19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Roger VL, Go AS, Lloyd-Jones DM, et al. American Heart Association Statistics C, stroke statistics S. Heart disease and stroke statistics—2012 update: a report from the american heart association. Circulation. 2012;125:e2–e220. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0b013e31823ac046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nichol G, Thomas E, Callaway CW, et al. Resuscitation Outcomes Consortium I. Regional variation in out-of-hospital cardiac arrest incidence and outcome. JAMA. 2008;300:1423–1431. doi: 10.1001/jama.300.12.1423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Culley LL, Rea TD, Murray JA, et al. Public access defibrillation in out-of-hospital cardiac arrest: a community-based study. Circulation. 2004;109:1859–1863. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000124721.83385.B2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Valenzuela TD, Roe DJ, Cretin S, Spaite DW, Larsen MP. Estimating effectiveness of cardiac arrest interventions: a logistic regression survival model. Circulation. 1997;96:3308–3313. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.96.10.3308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. [[accessed 04.09.12]];About twitter. www.Twitter.com.

- 12. [[accessed 14.10.12]];Infographic labs, Twitter 2012. http://infographiclabs.com/news/twitter-2012/

- 13.Smith A. [[accessed 14.10.12]];Twitter update 2011. Pew internet and american life project. 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 14.Collier N, Son NT, Nguyen NM. Omg u got flu? Analysis of shared health messages for bio-surveillance. J Biomed Semantics. 2011;2(Suppl. 5):S9. doi: 10.1186/2041-1480-2-S5-S9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Heaivilin N, Gerbert B, Page JE, Gibbs JL. Public health surveillance of dental pain via twitter. J Dent Res. 2011;90:1047–1051. doi: 10.1177/0022034511415273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sullivan SJ, Schneiders AG, Cheang CW, et al. ’What’s happening?’ A content analysis of concussion-related traffic on twitter. Br J Sports Med. 2012;46:258–263. doi: 10.1136/bjsm.2010.080341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chew C, Eysenbach G. Pandemics in the age of twitter: content analysis of tweets during the 2009 h1n1 outbreak. PLoS ONE. 2010;5:e14118. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0014118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Signorini A, Segre AM, Polgreen PM. The use of twitter to track levels of disease activity and public concern in the U.S. During the influenza a h1n1 pandemic. PLoS ONE. 2011;6:e19467. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0019467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Salathe M, Khandelwal S. Assessing vaccination sentiments with online social media: implications for infectious disease dynamics and control. PLoS Comput Biol. 2011;7:e1002199. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1002199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chunara R, Andrews JR, Brownstein JS. Social and news media enable estimation of epidemiological patterns early in the 2010 haitian cholera outbreak. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2012;86:39–45. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.2012.11-0597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Szczypka GES, Aly E. Harvesting the twitter firehose for measurement and evaluation: a content analysis of tweets from the CDC’s tips from former smokers campaign. CDC Health Communication Workshop 2012; https://cdc.confex.com/cdc/nphic12/webprogram/Paper31009.html. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Paul MJ DM. You are what you tweet: analyzing twitter for public health; Proceedings of the fifth international AAAI conference on weblogs and social media (ICWSM 2011); http://www.Cs.Jhu.Edu/?mdredze/publications/twitter_health_icwsm_11.Pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Thackeray R, Neiger BL, Smith AK, Van Wagenen SB. Adoption and use of social media among public health departments. BMC Public Health. 2012;12:242. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-12-242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Merchant RM, Elmer S, Lurie N. Integrating social media into emergency-preparedness efforts. New Eng J Med. 2011;365:289–291. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1103591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chretien KC, Azar J, Kind T. Physicians on twitter. JAMA. 2011;305:566–568. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mandavilli A. Peer review: trial by twitter. Nature. 2011;469:286–287. doi: 10.1038/469286a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bottles K. Twitter: an essential tool for every physician leader. Physician Exec. 2011;37:80–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zarrella D. [[accessed 14.10.12]];The science of retweets. 2011 www.DanZarella.com.

- 29.Miller G. Sociology, social scientists wade into the tweet stream. Science. 2011;333:1814–1815. doi: 10.1126/science.333.6051.1814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.