Abstract

Carbon nanotubes internalize into cells and are potential molecular platforms for siRNA and DNA delivery. A comprehensive understanding of the identity and stability of ammoniumfunctionalized carbon nanotube (f-CNT)-based nucleic acid constructs is critical to deploying them in vivo as gene delivery vehicles. This work explored the capability of f-CNT to bind single- and double-strand oligonucleotides by determining the thermodynamics and kinetics of assembly and the stoichiometric composition in aqueous solution. Surprisingly, the binding affinity of f-CNT and short oligonucleotide sequences was in the nanomolar range, kinetics of complexation were extremely rapid, and from one to five sequences were loaded per nanotube platform. Mechanistic evidence for an assembly process that involved electrostatic, hydrogen-bonding and π-stacking bonding interactions was obtained by varying nanotube functionalities, oligonucleotides, and reaction conditions. 31P-NMR and spectrophotometric fluorescence emission data described the conditions required to assemble and stably bind a DNA or RNA cargo for delivery in vivo and the amount of oligonucleotide that could be transported. The soluble oligonucleic acid-f-CNT supramolecular assemblies were suitable for use in vivo. Importantly, key evidence in support of an elegant mechanism by which the bound nucleic acid material can be ‘off-loaded’ from the f-CNT was discovered.

Keywords: Keywords: Functionalized carbon nanotubes, oligonucleotides, supramolecular assembly, fluorescence quenching, gene delivery

INTRODUCTION

Carbon nanotubes (CNT) exhibit a distinctive collection of electronic,1,2 mechanical,3 chemical4 and pharmacokinetic properties5–9 that may ultimately play key roles in designing novel delivery platforms for medical applications.10 The physicochemical versatility of these nanomaterials is related to their large surface area and aspect ratios that results in their ability to be functionalized with a multi-component array of diagnostic and therapeutic agents.11,12 In addition, CNT have been proposed to function as molecular transporters with the demonstrated ability to deliver several types of biological molecules into cells, including drugs,6,12 oligonucleotides (RNA and DNA),13,14 plasmids,15–17 peptides18 and proteins.19

The gene knockdown strategy, employing small interfering RNA sequences, has attracted considerable interest in cancer therapy.20,21 However, the major drawback in the clinical translation of this technology was the lack of an effective delivery platform for systemic administration.22,23 Oligonucleotide sequences have serum half-lives of seconds to minutes, are degraded or rapidly cleared through the kidney, and do not readily transit the cell membrane.24 Consequently, silencing RNA sequences (siRNA) exhibited a limited cellular uptake as well as non-specific distribution in vivo. Some of these design issues can be overcome by conjugating or encapsulating siRNA with nanoparticles such as liposomes, cationic polymers or dendrimers and some of these systems have been approved for clinical trials.25–27 The increasing interest in the deployment of CNT as platforms for oligonucleotide delivery28–30 is encouraged by reports that single-stranded (ss) and double-stranded (ds) DNA interacted with pristine single walled (SW) CNT and that adsorption of ss-DNA onto a mixture of different types of nanotubes can be used to separate and purify SWCNT by length and chirality.31–36

The toxicological profile of insoluble, pristine CNT has been a major challenge in advancing these materials as constituents of medical devices and drugs.37–40 Drug and gene delivery applications of these nanomaterials require a better strategy to deal with issues of biological compatibility.41–48 Non-covalent approaches using DNA to stabilize pristine SWCNT demonstrated an increased serum stability and cell uptake.49,50 However, the covalent chemical functionalization of CNT has overcome the biocompatibility issues associated with pristine CNT and permitted renal elimination.5–8,51–57 Our group recently demonstrated that covalently functionalized SWCNT (f-CNT) constructs were rapidly cleared intact through the kidneys by glomerular filtration with partial tubular cell reabsorption.8 We proposed that f-CNT were longitudinally aligned with the blood flow and readily penetrated the glomerular capillary pores due to their high aspect ratio as explanation to this paradoxical behavior. In conclusion, the chemical functionalization of nanotubes significantly improved renal clearance, tissue distribution and toxicity profile of CNT.8,11,58–60

Molecular-scale engineering of CNT-based gene delivery systems requires a quantitative chemical understanding of the several different non-covalent interactions that direct the supramolecular assembly of constructs. Designing and constructing self-complementary molecular assemblies in polar solvents is a challenging problem61 and there has been little done to quantitatively explain the thermodynamic, kinetic, and stoichiometric parameters guiding the non-covalent assembly of f-CNT constructs in aqueous solution. Molecular dynamic simulations have been performed in order to predict structure, self-assembly, and the binding affinity of ss-DNA with pristine CNT,62–65 but rarely have similar studies with f-CNT or charged nanotubes been described.66 One experimental thermodynamic study investigated the binding of ss-DNA with pristine SWCNT and reported that the DNA was able to exchange with surfactant molecules adsorbed onto the nanotube surface and subsequently bind with micromolar affinities that depended on the oligomer length and the chirality of the nanotubes.67

In the present work, we analyzed the binding affinity of a series of ss and double strand (ds) DNA and RNA oligomers with ammonium f-CNT. We investigated the kinetics, binding affinity, and stoichiometric loading of complex formation by means of fluorescence spectrophotometric titration with a fluorophore bound to the oligonucleotide sequence. This methodology used the quenching of fluorescent dye emission by CNT as the observed experimental parameter. When the dye and the CNT molecules are in close proximity, typically < 10 nm, an energy transfer between the excited state of the fluorescent molecule and the delocalized f-CNT molecular orbitals occured, preventing fluorescence emission.57,68 Graphical and mathematical elaboration of the spectrophotometric titration data turned out to be a reliable and rapid method to examine and analyze the supramolecular assembly of oligonucleotides and f-CNT, providing useful information on kinetics, stoichiometry and binding affinity. Phosphorous NMR was also utilized to investigate the contribution of hydrogen-bonding in the supramolecular assembly. These data were valuable in design optimization as they provided guidance for predicting stability under physiological conditions, and at the same time, mechanistically explained how to disassemble the construct and offload the genetic vector.

EXPERIMENTAL

Chemical functionalization and characterization of SWCNT

Single-walled carbon nanotubes (SWCNT) produced by high pressure carbon monoxide (HiPCO) technique were acquired from Unidym, Inc. (Menlo Park, CA). All solvents and chemicals were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich and used without further purification unless otherwise stated. The initial step was to purify the raw SWCNT to yield ox-CNT (1). Covalent sidewall-functionalization of 1 with multiple N-tert-butoxycarbonyl protected-amine groups was performed using the azomethine ylide cycloaddition strategy69 to yield CNT-NHBoc (2). The multiple amine groups covalently appended to 2 were deprotected with trifluoroacetic acid to yield CNT-NH3+ (3) and the amine content was assayed by a quantitative Sarin assay.70 The amine functionalities on 3 were modified with the bifunctional chelate 2-(4-isothiocyanatobenzyl)-1,4,7,10-tetraazacyclododecane-1,4,7,10-tetraacetic acid (p-SCN-Bz-DOTA; Macrocyclics, Inc.) to synthesize CNT-DOTA (4). Surface-enhanced Raman spectroscopy (SERS), transmission electron microscopy (TEM), dynamic light scattering (DLS) and ζ-potential analyses were used to characterize 3. SERS analysis employed silver colloid films prepared using a modified Lee-Meisel method71 and the Raman spectrum was obtained with a custom-built Raman microscope using 0.1 mW of laser power at a wavelength of 488 nm, and an integration time of 30 s.72 TEM analysis was performed on 200 mesh grids coated with carbon support film and viewed on a JEOL JEM 1400 TEM with a LaB6 filament. Images were taken using an Olympus SIS Veleta 2k x 2k side mount camera. DLS and ζ potential measurements were performed using a Zetasizer Nano ZS system equipped with a narrow bandwidth filter (Malvern Instruments, MA). The average value of the radius of hydration (Rh) of 3 was obtained using the non-negative least squares fitting algorithm provided with the DLS software. See the Supporting Information (SI) for complete details of synthesis and characterizations.

Oligonucleotides

Deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) sequences with phosphorothiolate-modified backbones and ribonucleic acid (RNA) sequences with 2’O-methoxy-modified backbones were obtained from Trilink Biotechnologies (San Diego, CA) and are found in Table 1. Selected sequences were covalently modified with fluorescent dyes either using phosphoramidite coupling at the 5’-terminus or via a N-hydroxysuccinimide moiety appended to the dye molecule that was reactive with a primary amine at the 3’-terminus. Briefly, the 3’-modification was performed as follows: 1 mg of VivoTag 680 XL (VT680, 1,856 g/mol; excitation at 665 nm; emission at 688 nm; ε = 210,000 M−1cm−1) or VivoTag-S 750 (VT750, 1,183 g/mol; excitation at 750 nm; emission at 775 nm; ε = 240,000 M−1cm−1) (Perkin Elmer, Waltham MA) were dissolved in 0.1 mL of DMF and added dropwise to 0.6 mL of a solution of the oligonucleotide in a 20:1 mole ratio. The reaction was stirred at room temperature for 4h in the dark and unreacted fluorophore was separated from the functionalized oligonucleotide using a 10 DG size-exclusion chromatography column (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA) with a phosphate-buffered saline (PBS, 137 mM NaCl, 10 mM Na2HPO4, and 2.0 mM KH2PO4, pH 7.4) mobile phase. The purity of the oligonucleotide-dye molecule was evaluated by analytical HPLC and UV-Vis spectroscopy. HPLC was performed using a Beckman Coulter System Gold Bioessential 125/168 diode array detection system (Beckman Coulter, Fullerton, CA) equipped with an in-line Jasco FP-2020 fluorescence detector (Tokyo, Japan). UV-Vis spectroscopy was performed with a Cary 100 Bio spectrophotometer (Varian, Palo Alto, CA) or a Spectramax M2 (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA).

Table 1.

DNA and RNA sequences used in this work.

| DNA oligonucleotide sequences | |

| 5a | 5’ Cy3-TAGTGTTGACGAAGGGAC-C3SSC3 3’ |

| 5b | 5’ TAGTGTTGACGAAGGGAC-XT-C6-NH2 3’ |

| 5c | 5’ TAGTGTTGACGAAGGGAC-XT-C6-VT680 3’ |

| 6a | 5’ GTCCCTTCGTCAACACTA-XT-C6-NH2 3’ |

| 6b | 5’ GTCCCTTCGTCAACACTA-XT-C6-VT750 3’ |

| RNA oligonucleotide sequences | |

| 7 | 5’ GUCCCUUCGUCAACACUA-C6-NH2 3’ |

| 8a | 5’ UAGUGUUGACGAAGGGAC-C6-NH2 3’ |

| 8b | 5’ UAGUGUUGACGAAGGGAC-C6-VT680 3’ |

| 9 | 5’ Cy3-AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAA 3’ |

| 10 | 5’ UUUUUUUUUUUUUUUUUU-C6-NH2 3’ |

| Additional substituents in the oligonucleotide sequences above were abbreviated as follows: C6 indicated a (-CH2-)6 hexyl spacer; C3 a (-CH2-)3 propyl spacer; X a hexaethylene glycol spacer; and C3SSC3 a terminal (-CH2-)3-SS-(-CH2-)2-CH3 group. | |

The DNA and RNA sequences were annealed with complementary sequences to prepare duplexes by mixing equimolar aliquots of oligonucleotides in a hybridization buffer (10 mM HEPES, 140 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, pH 7.6) or PBS (pH 7.4) and heated at 70–95°C for 10 minutes. Upon slow cooling to ambient temperature, the melting temperature of the duplex was evaluated by the hyperchromic change in absorbance at 260 nm. The spectra were recorded while temperature was increased at a rate of 2°C per minute using a Cary 100 Bio UV-Vis Spectrophotometer coupled to a Cary Temperature Controller. The data were plotted to graphically yield a duplex melting temperature. Duplex molecules of 5a and 6a (5a:6a); 5c and 6b (5c:6b); 7 and 8b (7:8b); and 9 and 10 (9:10) were prepared and characterized in this manner.

Spectrophotometric fluorescence quenching titration experiments

The oligonucleotide solution concentrations were determined spectrophotometrically by absorbance at 260 nm and when available, at the absorbance maxima of the appended fluorophore. A standard curve of the fluorescence emission was generated at different concentrations of 5a in pH 7.4 PBS to confirm linearity. The concentrations of f-CNT solutions were determined by the absorbance at 600 nm as described.5,6 In all of the experiments, the measured emission values (F) were obtained in triplicate at 37°C from the spectral data using a Cary Eclipse Fluorescence Spectrophotometer and the mean value reported. A similar concentration range of oligonucleotide was used for each titration experiment and aliquots of f-CNT were added incrementally with mixing. Sequential fluorescence spectra were recorded in order to determine emission values after each f-CNT aliquot addition. The fluorescence emission of different concentrations of 3 was determined at 562 nm to determine the contribution of f-CNT emission to the titration data. In all titration experiments described, F values were normalized to the original oligonucleotide-dye fluorescence value, F0. The emission signal was also volumetrically corrected for dilution effects. Data were analyzed graphically, by curve fitting methods using GraphPad Prism (LaJolla, CA), or mathematically.73

The spectrophotometric titrations of the ss-DNA 5a with 3 (CNT-NH3+) was conducted at three pH conditions of 5.5, 7.4, and 9.6. Briefly, a 0.31 μM solution of 5a at 37°C was titrated with incremental additions of 3 and the subsequent decrease in fluorescence was monitored. The solutions were buffered to pH 5.5 with 137 mM NaCl, 0.5 mM Na2HPO4, and 10 mM KH2PO4; pH 7.4 with 137 mM NaCl, 10 mM Na2HPO4, and 2 mM KH2PO4; or pH 9.6 with 137 mM NaCl, 10 mM NaHCO3. Further data were collected by titration of 5a with 2 (CNT-NHBoc) and 4 (CNT-DOTA) at pH 7.4. The titrations of the ds-DNA 5a:6a with 3 was also conducted at the three same pH conditions. Briefly, a 0.16 μM solution of 5a:6a at 37°C was titrated with incremental additions of 3 and the subsequent decrease in fluorescence emission was monitored. The solutions were buffered as described. Further data were collected by titration of 5a:6a with 2 and 4 at pH 7.4.

Analogous spectrophotometric titration of ss-RNA 8b with 3 was conducted at pH 7.4. Briefly, a 0.96 μM solution of 8b at 37– was titrated with incremental additions of 3 and the subsequent decrease in fluorescence was monitored. Similarly, 9 was titrated with 3 at pH 7.4. The titration of the ds-RNA 7:8b with 3 was conducted at pH 7.4. Briefly, a 0.42 μM solution of 7:8b at 37°C was titrated with incremental additions of 3 and the subsequent decrease in fluorescence was monitored. Similarly, 9:10 was titrated with 3 at pH 7.4.

The stoichiometry of the complex was also investigated by the continuous variation method to yield a Job plot. This method is based on the difference in fluorescence emission (ΔF) between the nanotube complex and the free fluorophore-labeled oligonucleotide at the same concentration. Briefly, a number of solutions with different mole fraction but with a constant total concentration (carbon nanotube and oligonucleotide) were prepared in PBS at pH 5.5 in order for the total concentration to remain constant. ΔF values (F0-F) were calculated by measuring the fluorescence intensity of the oligonucleotide in the absence (F0) and presence (F) of 3 for each different mole fraction, at 37°C. The analysis was performed for ss- and ds-DNA (5a and 5a:6a) as well as ss- and ds-RNA (9 and 9:10).

NMR spectroscopy

Phosphorous-31 nuclear magnetic resonance (31P-NMR) spectra were obtained at 25°C on a Bruker Ultra Shield Plus 500 MHz spectrometer operating at a frequency of 202.5 MHz. The 31P-NMR analyses were performed in a 0.9% NaCl/D2O solution and all chemical shifts were determined on proton-decoupled spectra referenced to an external standard of phosphoric acid (H3PO4). 31P-NMR spectra of 9, 10, and 9:10 alone and complexed with 3 at different mole ratios were measured. These experiments employed a fixed oligonucleotide concentration and the pH was adjusted to 7.4 with of the addition of 0.1 N NaOH in D2O.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Pristine CNT were subjected to a purification and mild oxidation process and ox-CNT (1) was isolated in 92% yield; this procedure served to purge the CNT of metallic impurities that might later interfere with the complexation of the oligonucleotides. The sidewall functionalization of 1 produced the CNT-NHBoc (2) derivative in 18% yield, and the ensuing amine-deprotection of 2 provided CNT-NH3+ (3) in 12% yield; it was determined that there was 0.377 mmol of amine per gram of 3. The amine content of 2 was below the detection limit of the assay. The CNT-DOTA derivative (4) was prepared in 97% yield and was assayed to have 0.052 mmol amine per gram of 4 and indicated that 86% of the amines were DOTA-functionalized. SERS analyses confirmed the f-CNT identity of 3 and the spectrum is shown in Figure 1a. The characteristic RBM, D- and G-bands were observed at 238, 1371, and 1595 cm−1, respectively. TEM analysis of 3 demonstrated a pure f-CNT sample with bundled lengths approximately 300 nm (Figure 1b). DLS analysis of 3 showed an average intensity-based diameter of hydration of 234.5 ± 15.5 nm. Based on this evidence we estimated an average molecular weight of 300,000 kDa for 3. The ζ-potential of 3 was determined to be +15.9 ± 0.58 mV.

Figure 1.

Characterization of 3 showing the a. SERS spectrum and a b. TEM image. (n.b., An asterisk in 1a is used to mark a spurious peak that arises from laser scatter.)

This functionalization process promoted CNT solubility and dispersion in aqueous solutions, and conferred fibrillar pharmacology and biological compatibility.8,55,74,75 It was decided to use f-CNT platforms for gene vector delivery and therefore necessary to fully investigate the nature of the supramolecular interactions with representative 18-mer oligonucleotide sequences (ss- and ds-DNA or RNA). Our goal was to determine the binding strength, loading-stoichiometry and kinetics of the constructs that were assembled in aqueous solution.

The DNA and RNA oligonucleotides used in this work are reported in Table 1 and contained random 18-mer sequences that were designed to not exhibit self-complementary binding.7 Some of them were covalently modified with fluorescent dye molecules.

It was known that molecular fluorophores in close proximity to the surface of a CNT realize a loss of fluorescence emission by a quenching mechanism.14,76–80 The quenching effect can be attributed to two different phenomena: (i) dynamic interaction - when the fluorophore diffuses to the CNT surface during the lifetime of the excited state and transfers its surplus energy to the CNT ground state; or (ii) static interaction - when a new non-fluorescent species with different chemical and physical properties is formed. In the case of the dye-functionalized oligonucleotide 5a, a red shift in the UV-Vis spectra81 (Figure S-1a) indicated a static interaction with 3. Therefore, the fraction of fluorescence extinguished was directly correlated to the relative amount of oligonucleotide binding to the f-CNT complex, as the oligonucleotide was covalently linked to a fluorophore. The kinetics of ss- and ds-oligonucleotide complex assembly with 3 was very rapid at 37°C in pH 7.4 PBS as shown in Figures S-1b and S-1c. The fluorescence was quenched immediately upon adding an aliquot of 3 sufficient to coordinate all of the oligonucleotide in solution.

Fluorescence quenching has been investigated with pristine SWCNT and PEG-fluorescein,78 Rhodamine B,81 and dye-modified oligomers.82 However, there have been no analogous investigations of the interactions of dye-modified oligomers with amino-functionalized CNT.

The overall positive, neutral, and negative surface charges of the three different f-CNT (i.e., 3, 2, and 4, the CNT-NH3+, CNT-NHBoc, and CNT-DOTA2−, respectively) were selected to control the net surface charge and thus presented a key means to probe the electrostatic binding interactions with short ss- and ds-oligonucleotide sequences. Varying the pH of the titration reaction and thus the extent of amine protonation was another means to control the surface charge of 3. The pKa of the primary aliphatic amines that were attached to 3 was taken to be 9.5.83 The ratio of [RNH3+]/[RNH2] was 10,000, 125, and 0.79 at pH 5.5, 7.4, and 9.6, respectively; 99.9, 99.2, and 44.1% of the amines on 3 were protonated at those pH values. The pKa of the Boc-protected amines on 2 was -0.5 and essentially no (1E-08%) amines were protonated, which conferred an overall neutral charge at pH 7.4. Each appended DOTA moiety on derivative 4 possesses a double negative charge at pH 7.484 and f-CNT constructs similar to 4 had a ζ potential of −8.9 ± 3.3 mV.8

Oligonucleotide sequences were chosen to avoid self-complementary folding and contained a 50% GC base composition. Phosphorothiolate or 2’O-methoxy backbone modifications were incorporated to improve the stability of DNA and RNA sequences, respectively, in anticipation of translation to studies in vivo. Fluorescent dye modification of DNA and RNA sequences yielded 1 Cy3-to-1 DNA in 5a; 1 VT680-to-1.9 DNA in 5b; 1 VT750-to-1.4 DNA in 6b; 1 VT680-to-2.2 RNA in 8b; and 1 Cy3-to-1 RNA in 9. The duplex melting temperatures (see Figure S-2) of 5a:6a; 5c:6b; 7:8b; and 9:10 were 50, 50, 95, and 54 °C, respectively.

Sigmoidal titration curves were observed for ss-DNA 5a titrated with 3 at different pH values. Figure 2a graphically shows the stoichiometric-loading data. The curves at pH 5.5 and 7.4 showed almost complete quenching of the starting fluorescence when the mole ratio of 5a and 3 was about 5 and 3, respectively. In the case of pH 9.6 data, the fluorescence was incompletely quenched. In particular, when the ratio was 1-to-1, only 60% of the F0 was extinguished, whereas with a 5-to-1 ratio only 18% quenched. The outcome was explained assuming that a major component of the supramolecular interaction was electrostatic. The incomplete complex formation at pH 9.6 was attributed to the decreased positive charge of 3 at this pH versus the almost complete protonation of the amines at pH 5.5 and 7.4. The protonation of phosphate groups on oligonucleotides is not relevant in this pH range. Hence, the decreased number of 5a bound to 3 at higher pH was attributed to an overall reduced number of electrostatic interactions. The titration data also provided key information about binding affinity, Kd. Values were evaluated by plotting the fraction of quenched fluorescence, ΔF/F0 (where ΔF = F0 − F) as a function of increasing concentration of 3 (Figure 2b). The Kd and stoichiometric-loading data for numerous assemblies are reported in Tables 2 and 3, respectively. Dissociation constants were in the nanomolar range and demonstrated a very strong, nanomolar range, affinity between f-CNT and oligonucleotides. The exceptional stability of the ss-DNA:CNT-NH3+ complexes in physiological conditions was also confirmed by the challenge experiment illustrated in Figure S-3. Furthermore, varying the pH affected both the stoichiometry of the complexation as well as the stability of the final supramolecular assembly.

Figure 2.

Spectrophotometric titration data shows the pH dependence of ss-DNA 5a with 3 at pH 5.5, 7.4, and 9.6, at 37ºC. Data are reported in a. as fluorescence ratio (F/F0) plotted against the mole ratio of oligonucleotide-to-CNT; and in b. as the fraction of quenched fluorescence (ΔF/F0) versus the concentration of carbon nanotube, 3. (n.b., the mean molecular weight of 3 was assumed to be 300,000 g/mol.).

Table 2.

Dissociation constants of different carbon nanotube platforms with ss- and ds-oligonucleotides measured at different pH values.

| f-CNT | 3 | 2 | 3 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||

| Oligo | 5a | 5a:6a | 5a | 5a:6a | 8b | 7:8b | 9 | 9:10 |

|

| ||||||||

| PH | Kd (nM) | |||||||

| 5.5 | 8.9 | 7.8 | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND |

| 7.4 | 21 | 11 | 130 | 234 | 7.1 | 9.8 | 9.5 | 10 |

| 9.6 | 120 | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND |

Table 3.

Loading-stoichiometry values for complex formation with 3 and various ss- or ds-oligonucleotides at different pH values.

| Number of oligonucleotide substituents per 3

| ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PH | 5a | 5a:6a | 8b | 7:8b | 9 | 9:10 |

| 5.5 | 5 | 4 | ND | ND | ND | ND |

| 7.4 | 3 | 2 | 4 | 2 | 3 | 1 |

| 9.6 | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND |

A parallel series of titration experiments was performed with ds-DNA 5a:6a. The data are reported in Figure 3 and were similar to the ss-DNA data. In particular, the highest mole ratio of 5a:6a-to-3 at which the fluorescence was completely extinguished was 4 at pH 5.5 and 2 at pH 7.4; and the pH 9.6 titration again showed incomplete quenching. Also in this case, Kd values were in the nanomolar range (Table 2), but were slightly smaller (more strongly bound) than the corresponding ss-DNA data. This difference was attributed to the higher number of phosphate groups available to interact with the ammonium moieties on the nanotube surface, which accounted for a bigger enthalpic factor toward the free energy change upon supramolecular interaction. Also, the greater number of degrees of freedom (higher flexibility) of free ss-DNA with respect to ds-DNA implied a more positive entropy change after complexation with the nanotube. On the other hand, the lower loading-stoichiometry values of ds-DNA compared to ss-DNA was correlated to a more remarkable impact on polarity of the nanotube surface after binding of the first molecules of ds-DNA, as they carry double the amount of negative charges per unit length.

Figure 3.

Spectrophotometric titration data shows the pH dependence of ds-DNA 5a:6a with 3 at pH 5.5, 7.4, and 9.6, at 37ºC. Data are reported in a. as fluorescence ratio (F/F0) plotted against the mole ratio of oligonucleotide-to-CNT; and in b. as the fraction of quenched fluorescence (ΔF/F0) versus the concentration of carbon nanotube, 3.

Almost no fluorescence quenching was observed when 5a was titrated with the negative-charged derivative 4, because of electrostatic repulsion (Figure 4). This observation leads to the conclusion that electrostatic attractive forces were crucial in the association of the two species in aqueous solution. As further proof of this thesis, we demonstrated that charge neutral 2 exhibited a very limited interaction with ss-DNA and that was even weaker with ds-DNA. The weaker ds-DNA interaction can be explained by considering that π-stacking forces, which were playing a secondary role in the complex formation with derivative 3, were the only relevant interactions for assembly with 2. Specifically, these involve π-stacking interactions between the aromatic nitrogen bases of 5a and the aromatic surface of the carbon nanotube.

Figure 4.

Spectrophotometric titration data at 37°C and pH 7.4 of combinations of the ss-5a and ds-5a:6a with positive-, neutral-, and negative-charged 3, 2, and 4, respectively. Data are reported in a. plotting the fluorescence ratio (F/F0) vs. the mole ratio of oligonucleotide-to-carbon nanotube, and in b. as fraction of quenched fluorescence (ΔF/F0) vs. carbon nanotube concentration.

Analysis of the data in Figure 4 showed that when the π-stacking interactions were limited using a ds-DNA, in which only the exposed ends were available to exert hydrophobic base contacts, then the affinity of the molecular assembly decreased relative to the ss-DNA. This result was explained with a model where the attractive electrostatic interactions dominate over π-stacking forces. Previously, a molecular modeling study predicted that a 12-mer ds-DNA would adsorb onto a positive-charged CNT through electrostatic interaction whereas only the hydrophobic end groups of the DNA oligomer were able to interact with uncharged CNT.66 Furthermore, when a negative charged 4 and a negative charged 5a were mixed, repulsive forces separated them and π-stacking had no impact on binding.

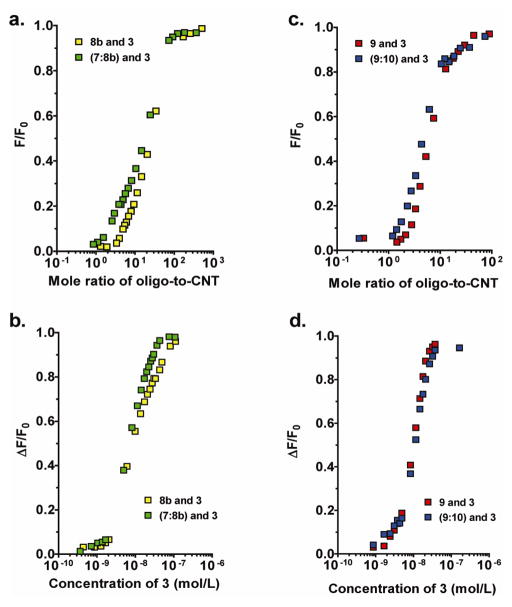

RNA sequences were titrated with 3 in corresponding fluorescence experiments. The sequences studied were similar to the DNA, except for the substitution of uracil for thymine. Interestingly, the ss- and ds-RNA (8b and 7:8b) complexes with 3 had similar Kd values of 7.1 and 9.8 nM, respectively and loading-stoichiometries of 4 and 2, respectively (Figures 5a and b).

Figure 5.

Spectrophotometric titration curves comparing ss- and ds-RNA oligonucleotide complex formation with 3 at pH 7.4 and 37°C. Titration data showing ss-RNA 8b and ds-RNA 7:8b titrated with 3. Data are reported in a. plotting the fluorescence ratio (F/F0) vs. the mole ratio of oligonucleotide-to-carbon nanotube, and in b. as fraction of quenched fluorescence (ΔF/F0) vs. carbon nanotube concentration. Similarly, ss-RNA oligomer 9 and ds-RNA oligomer 9:10 were titrated with 3 and data reported in c. as fluorescence ratio (F/F0) vs. mole ratio of oligonucleotide-to-CNT. The same data were processed in d. as fraction of quenched fluorescence (ΔF/F0) vs. concentration of 3.

Polyadenosyl (poly(A)) phosphate ss-sequence 9 and a poly(A):polyuridine (poly(U)) ds-sequence 9:10 had Kd values of 9.5 and 10 nM, respectively, while the loading capabilities were 3 and 1, respectively (Figures 5c and d). The RNA oligomers demonstrated slightly greater affinities compared to the corresponding DNA sequences and this difference was explained by the lower flexibility of the modified RNA backbone, which suggested a smaller reorganizational requirement for the DNA oligonucleotide to conform and bind to the charged nanotube surface.

Assuming that multiple negatively charged phosphate moieties were simultaneously interacting with the positively charged surface of a nanotube, the supramolecular assembly of oligonucleotides and carbon nanotubes was an enthalpically driven process. In the case of ss-RNA:CNT-NH3+ the entropic factor was not as unfavorable as in the case of ss-DNA, as the DNA was more flexible and more easily conformed to the nanotube. Furthermore, there was not a significant difference either in the loading-stoichiometry or in the binding affinity between the two different sequences of RNAs that were studied (e.g. 8b and 9). This implied that the base sequence did not strongly affect the actual binding and corroborated our hypothesis of the greater importance of electrostatic interactions over π-stacking forces.

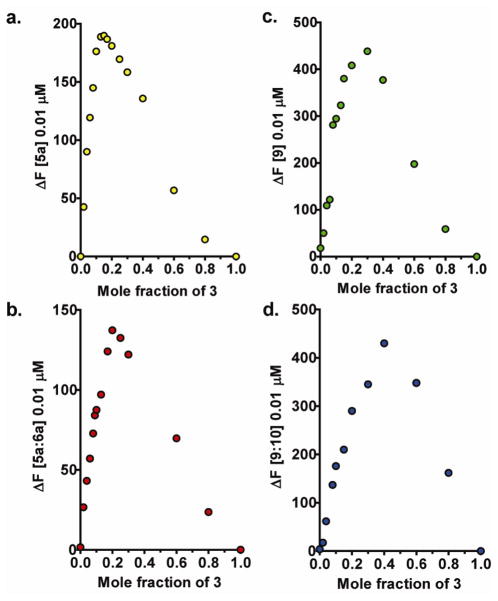

The loading-stoichiometry of 3 with ss- and ds-DNA and RNA complexes was also evaluated by using the continuous variation method of Job as previously reported for the fluorescence dependent formation of other supramolecular systems.85 The total concentration of the ss- or ds-oligonucleotide sequence and 3 was held constant, while the mole fractions were varied. The fluorescence intensity, which was proportional to the concentration of the oligonucleotide-CNT complex, was plotted versus the mole fraction of 3. The position of the maxima in the Job plot in Figure 6 showed that complexes of 5a, 5a:6b, 9, and 9:10 with 3 was 5.7, 4.0, 2.3, and 1.5 moles of oligonucleotide per mole of 3, respectively.

Figure 6.

The loading-stoichiometry of the assembled complexes investigated by the method of continuous variation based on the difference in fluorescence intensity (ΔF). Job plots for a. ss-DNA 5a and 3; b. ds-DNA 5a:6 and 3; c. ss-RNA 9 and 3; and d. ds-RNA 9:10 and 3. 3

The concentration of unbound oligonucleotide 5a in solution at different mole ratios of 5a-to-3 was empirically determined by constructing a fluorescence standard curve (Figure S-1f) and evaluated with a dissociation equilibrium relationship (SI Equation 1). The data reported in Table S-1 converged at an average value of 3 guest molecules of 5a per host molecule 3. Noteworthy, these loading-stoichiometry results obtained from the empirical analysis of the titration data were in good agreement with the graphically extrapolated data in Figure 2a and with the results obtained from the Job plot in Figure 6a. These three different analyses all provided similar results for the loading-stoichiometry of 3 with 5a.

Moreover, we employed a mathematical elaboration of the spectroscopic data (SI Equations 2–8) for the assembly of 5a with 3, which confirmed the dissociation constant obtained by graphical methods. In fact, the linear regression plot (Figure S–4) of the data deduced from SI Equation 8 yielded a Kd value of 21.5 nM, precisely matching the value determined graphically from the curve in Figure 2b and reported in Table 2.

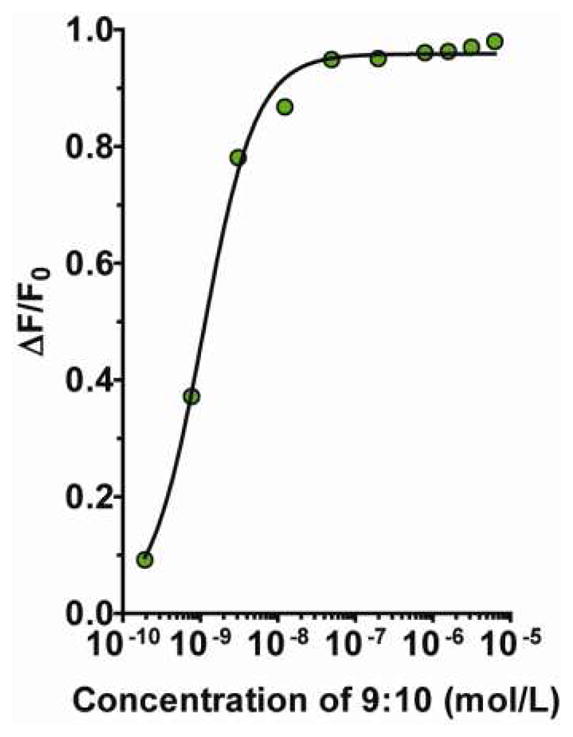

Evidence for the mechanism of off-loading the oligonucleotide from the f-CNT was obtained for the construct of 9:10 and 3 using serial dilution. The relative increase in fluorescence emission was measured and compared to the emission of only 9:10 at the same concentration. The emission at 562 nm was recorded for a 1-to-1 complex of ds-RNA 9:10 and 3 versus a solution of 9:10 alone in PBS (pH 7.4) and 37°C. Serial dilutions were performed and the relative change in emission intensity was reported as a function of the ds-RNA concentration (Figure 7); this data illustrated that as the complex was diluted, the effective concentration decreased below the binding threshold, and the oligonucleotide was released from the f-CNT. Dissociation of 9:10 from 3 confirmed the static fluorescence quenching mechanism, thus restoring the emission of the cyanine dye appended to the ds-RNA. Importantly, this experiment demonstrated the reversibility of the complex assembly under these conditions and recommended a means to control release of the cargo.

Figure 7.

The dissociation of the complex formed from assembled 9:10 and 3 by serial dilution. The solid black line represents the binding curve generated from the data plotted as fraction of quenched fluorescence (ΔF/F0) vs. concentration of ds-RNA. 3

This serial dilution experiment demonstrated the effectiveness of this data in designing these constructs for deployment in biological studies. The loading-stoichiometry data described the amount of cargo that can be efficiently bound to f-CNT of this size. The kinetic data demonstrated the rapid and quantitative assembly process in aqueous solution at 37°C. The Kd values were in the nM affinity range and implied excellent stability in vivo or in vitro. These data described the concentration conditions that would be required to stably bind the DNA or RNA cargo for delivery in vivo as well as the amount of oligonucleotide loaded onto the platform. Now, serial dilution of the assembled construct provided key evidence for a mechanism by which any oligonucleotide cargo could be off-loaded from the f-CNT vehicle once targeted to a cellular destination. Consider that if the assembled construct was delivered to a cell, internalized and compartmentalized, and any undelivered construct was cleared from the host (e.g., renal elimination),8 then the assembled construct will necessarily undergo dilution and the f-CNT would be compelled to release the oligonucleotide cargo.

Nuclear magnetic resonance studies were also conducted in order to provide more detailed information about the contribution of the hydrogen-bonding component of the supramolecular interaction. Phosphorous-31 NMR was used to investigate the hydrogen-bonding interaction between the RNA phosphate backbone and the ammonium groups on the nanotubes to determine if it was relevant in complex formation. The poly(A) and poly(U) oligonucleotide sequences (9 and 10, respectively) were selected to acquire uniform signals in the NMR spectra as the internal phosphates had an almost identical chemical environment, due to the presence of only one type of nitrogen base per sequence, rendering them approximately magnetically equivalent.

The terminal 5’-phosphate appeared in a distinct position in the NMR spectra compared to the internal phosphate signals and the integrated ratio was 1:17, respectively. Furthermore, as the kinetics of complexation and decomplexation appeared to be rapid on the NMR timescale, only one peak was observed for the free and complexed oligonucleotide species.

The spectra of ss-RNA sequences 9 and 10 showed a broad singlet at −1.220 and −1.201 ppm, respectively (Figures 8a and b). Another minor peak was observed at −0.858 ppm for 9 and −0.381 ppm for 10. Spectra of the ds-RNA 9:10 (Figure 8c) showed two broad peaks at −1.207 and −1.590 ppm, attributed to the nonequivalence of the poly(U) and poly(A) phosphates in the duplex.86 The NMR spectra of the assembled complexes of 9, 10, and 9:10 with 3, each exhibited upfield shifts in the 31P resonances with decreasing RNA-to-3 ratio, as compared to the free RNA species (Table 4).

Figure 8.

31P-NMR spectra of mixtures of A. 9 and 3 with decreasing 9-to-3 mole ratios (from top to bottom: ∞, 10000-, 1000-, 500-, 100-, and 10-to-1); b. 10 and 3 with decreasing 10-to-3 mole ratios (from top to bottom: ∞, 1000-, 500-, 100-, and 10-to-1); c. 9:10 and 3 with decreasing 9:10-to-3 mole ratios (from top to bottom: ∞, 1000-, 500-, 100-, and 10-to-1); All NMR spectra were referenced to an external phosphoric acid (H3PO4) standard solution in D2O with a resonance at 0.0 ppm.

Table 4.

31P-NMR chemical shifts of the internal phosphate resonances measured for solutions of ss- and ds-RNA complexed with 3 at different mole ratios.

| 9 | 10 | 9:10 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| oligo-to-3 mole ratio | Chemical shift δ (ppm) | |||

| ∞1 | −1.220 | −1.201 | −1.207 | −1.590 |

| 10000 | −1.236 | ND | ND | ND |

| 1000 | −1.277 | −1.207 | −1.208 | −1.593 |

| 500 | −1.283 | −1.212 | −1.212 | −1.599 |

| 100 | −1.305 | −1.215 | −1.217 | −1.602 |

| 10 | −1.307 | −1.220 | −1.228 | −1.604 |

The phosphorous NMR of oligonucleotide only.

There were not many examples of 31P-NMR studies of the interactions between oligonucleotide phosphates and amino groups in the literature. However, the effect of hydrogen-bonding on 31P-NMR chemical shifts have been described for a variety of cyclic nucleotides which invariably shifted downfield with increasing proportions of organic solvent relative to water.87 The data for the RNA assembled onto an ammonium-functionalized CNT demonstrated that the chemical shift of the phosphorous of a phosphate group moved upfield indicating hydrogen bond formation. Furthermore, the solvent induced chemical shifts observed for linear poly(U) and poly(C) were much smaller (~0.1 ppm) than in the case of the cyclic mononucleotides (~2 ppm),88 suggesting that steric and polyelectrolyte effects may compensate the hydrogen bond induced changes.

A 31P-NMR study of the crystallographically-solved89 nicotinamide adenosine dinucleotide phosphate (NADPH) - dihydrofolate reductase (DHFR) complex offered insight on how the 31P chemical shift was correlated to hydrogen-bonding interactions between the NADPH phosphates and the ammonium residues on the DHFR enzyme. The atomic distances revealed that the adenine pyrophosphate (PA) was extensively involved in hydrogen-bonding, and as a consequence, the PA 31P-resonance showed a large upfield shift upon complexation (2.69 ppm).90 Conversely, the nicotinamide phosphate (PN), which was connected to both amino acid residues and water molecules through hydrogen-bonding, was only slightly shifted upfield (0.16 ppm) upon binding to the DHFR active site.91

In general, an upfield shift in the 31P signals of the RNA oligonucleotides 9, 10, and 9:10 was observed upon interaction with f-CNT, relative to an H3PO4 solution used as external standard. The small peak at −0.858 ppm in Figure 8a was assigned to the terminal 5’-phosphate of 9, and in the same way, the minor peak at −0.381 ppm in Figure 8b was assigned to the terminal 5’-phosphate of 10.92 A shift towards higher fields, relative to the free oligonucleotide, was observed upon assembly of the complexes with 3 for both the terminal and internal phosphate groups.

As the mole ratio of oligonucleotide-to-CNT was decreased, increasingly larger chemical shifts towards higher field were observed. Similar to the DHFR-NADPH example, we argue that the smooth shift towards higher fields in the 31P-NMR spectra were evidence of hydrogen bond formation between 10 and 3 (The same trend was also observed with the assembly of 9 and 3.). The subtle magnitude of the shift was attributed to the presence of solvation molecules of water surrounding the phosphate groups in our aqueous system. As proof of concept, when the 31P-NMR of 9 and of its supramolecular adduct with 3 were measured in D2O:d6-DMSO (v/v, 1:1), the upfield shift of the complex was more remarkable (0.40 ppm) as shown in Figure S-5. In fact, when hydrogen bonds between nucleotide phosphates and water molecules were perturbed by addition of aprotic solvents,87,88 then those with the f-CNT-ammonium groups were favored.

The observed NMR behavior of 9:10 showed that both of the main phosphate peaks of poly(A) and poly(U) shifted upfield with a similar magnitude (Table 4) upon assembly with 3, indicating that there was no preferential binding of either one of the two sequences on the ammonium f-CNT surface, again confirming the significance of the electrostatic and hydrogen-bonding interactions relative to the π-stacking contributions. Also, a comparison of the relative chemical shifts of ss- and ds-RNA upon complexation with 3 showed two sigmoidal plots (Figure S-6) and demonstrated a good correlation between the two species, thus confirming the fluorescence titration result in Figure 5c. In general, this NMR data supported the hypothesis that hydrogen-bonding was an important contribution to the overall array of interactions directing the supramolecular assembly.

CONCLUSIONS

Identifying the significance and relative contributions of the several different non-covalent bonding interactions that direct the formation of stable supramolecular assemblies of DNA and RNA oligonucleotides and functionalized carbon nanotubes is essential to developing technologies that could facilitate deploying these vectors for gene therapy applications. This study should provide guidance in design, assembly, and utilization of f-CNT delivery vehicles for use in vitro and in vivo. Additionally, the data presented evidence for a unique mechanism to off-load the DNA or RNA cargo under physiological conditions. The fluorescence quenching phenomenon associated with molecular dyes and f-CNT was innovatively utilized in tandem with spectrophotometric techniques to collect data that described the binding affinity, kinetics and loading-stoichiometry of DNA and RNA oligonucleotides with f-CNT. A remarkable nanomolar affinity between the ammonium-functionalized carbon nanotubes and oligonucleotide species was observed as were very rapid and quantitative kinetics of complexation in aqueous solution at 37°C. A range from one to five oligonucleotide sequences was stably loaded per f-CNT. 31P-NMR was very useful to further interrogate this system. The strategic combination of methods, components and experimental conditions permitted the discovery that primarily electrostatic and hydrogen-bonding interactions, and to a lesser extent, π-stacking forces, all contributed to the supramolecular assembly of oligonucleotide and functionalized carbon nanotubes.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We appreciate the technical assistance of Ms. KD Derr of the Weill Cornell Medical College Electron Microscopy & Histology Core Facility and discussions with Dr. Daniel Thorek (MSKCC). The authors declare no competing financial interest. Supporting Information Available: Details of the chemical functionalization and characterization of SWCNT; spectroscopic and kinetic data characterizing the fluorescence quenching phenomenon; melting curves for duplex DNA and RNA; f-CNT bound oligo challenge experiment; empirical evaluation of the supramolecular assembly loading-stoichiometry; mathematical analysis of fluorescence titration curves; 31P-NMR of ss-RNA and a complex of ss-RNA and f-CNT in D2O:d6-DMSO and 31P NMR relative chemical shift is included in the Supporting Information. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

FUNDING

U.S. Department of Energy (Award DE-SC0002456), Emerging Technologies Continuing Umbrella of Research Grant from the National Cancer Institute (3U54CA132378-02S1), NIH R01CA55349 and PO1CA33049 and The MSKCC Experimental Therapeutics Center and the MSKCC Nanotechnology Center.

References

- 1.Bachilo SM, Strano MS, Kittrell C, Hauge RH, Smalley RE, Weisman RB. tructure-Assigned Optical Spectra of Single-Walled Carbon Nanotubes. Science (Washington, DC, U S) 2002;298:2361–2366. doi: 10.1126/science.1078727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tans SJ, Verschueren ARM, Dekker C. Room-Temperature Transistor Based on a Single Carbon Nanotube. Nature (London) 1998;393:49–52. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wong EW, Sheehan PE, Lieber CM. Nanobeam Mechanics: Elasticity, Strength, and Toughness of Nanorods and Nanotubes. Science (Washington, D C) 1997;277:1971–1975. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tasis D, Tagmatarchis N, Bianco A, Prato M. Chemistry of Carbon Nanotubes. Chem Rev (Washington, DC, U S) 2006;106:1105–1136. doi: 10.1021/cr050569o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McDevitt MR, Chattopadhyay D, Jaggi JS, Finn RD, Zanzonico PB, Villa C, Rey D, Mendenhall J, Batt CA, Njardarson JT, et al. PET Imaging of Soluble Yttrium-86-Labeled Carbon Nanotubes in Mice. Plos One. 2007;2 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0000907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McDevitt MR, Chattopadhyay D, Kappel BJ, Jaggi JS, Schiffman SR, Antczak C, Njardarson JT, Brentjens R, Scheinberg DA. Tumor Targeting With Antibody-Functionalized, Radiolabeled Carbon Nanotubes. J Nucl Med. 2007;48:1180–1189. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.106.039131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Villa CH, McDevitt MR, Escorcia FE, Rey DA, Bergkvist M, Batt CA, Scheinberg DA. Synthesis and Biodistribution of Oligonucleotide-Functionalized, Tumor-Targetable Carbon Nanotubes. Nano Lett. 2008;8:4221–4228. doi: 10.1021/nl801878d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ruggiero A, Villa CH, Bander E, Rey DA, Bergkvist M, Batt CA, Manova-Todorova K, Deen WM, Scheinberg DA, McDevitt MR. Paradoxical Glomerular Filtration Of Carbon Nanotubes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:12369–12374. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0913667107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McDevitt MR, Ma D, Lai LT, Simon J, Borchardt P, Frank RK, Wu K, Pellegrini V, Curcio MJ, Miederer M, et al. Tumor Therapy With Targeted Atomic Nanogenerators. Science (Washington, DC, U S) 2001;294:1537–1540. doi: 10.1126/science.1064126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Baughman RH, Zakhidov AA, de HWA. Carbon Nanotubes-the Route Toward Applications. Science (Washington, DC, U S) 2002;297:787–792. doi: 10.1126/science.1060928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Liu Z, Chen K, Davis C, Sherlock S, Cao Q, Chen X, Dai H. Drug Delivery with Carbon Nanotubes for In vivo Cancer Treatment. Cancer Res. 2008;68:6652–6660. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-1468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Liu Z, Fan AC, Rakhra K, Sherlock S, Goodwin A, Chen X, Yang Q, Felsher DW, Dai H. Supramolecular Stacking of Doxorubicin on Carbon Nanotubes for In Vivo Cancer Therapy. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2009;48:7668–7672. doi: 10.1002/anie.200902612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wu YR, Phillips JA, Liu HP, Yang RH, Tan WH. Carbon Nanotubes Protect DNA Strands During Cellular Delivery. Acs Nano. 2008;2:2023–2028. doi: 10.1021/nn800325a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kirkpatrick DL, Weiss M, Naumov A, Bartholomeusz G, Weisman RB, Gliko O. Carbon Nanotubes: Solution for the Therapeutic Delivery of siRNA? Materials. 2012;5:278–301. doi: 10.3390/ma5020278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pantarotto D, Singh R, McCarthy D, Erhardt M, Briand JP, Prato M, Kostarelos K, Bianco A. Functionalized Carbon Nanotubes for Plasmid DNA Gene Delivery. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2004;43:5242–5246. doi: 10.1002/anie.200460437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Al-Jamal KT, Gherardini L, Bardi G, Nunes A, Guo C, Bussy C, Herrero MA, Bianco A, Prato M, Kostarelos K, et al. Functional Motor Recovery from Brain Ischemic Insult by Carbon Nanotube-Mediated siRNA Silencing. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:10952–10957. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1100930108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Singh R, Pantarotto D, McCarthy D, Chaloin O, Hoebeke J, Partidos CD, Briand JP, Prato M, Bianco A, Kostarelos K. Binding and Condensation of Plasmid DNA onto Functionalized Carbon Nanotubes: Toward the Construction of Nanotube-Based Gene Delivery Vectors. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:4388–4396. doi: 10.1021/ja0441561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Terzian LA, Stahler N, Dawkins AT., Jr Differences in Drug Response of the Sporogonous Cycles of Three Strains of Plasmodium Falciparum in Anopheles Stephensi. Res Commun Chem Pathol Pharmacol. 1970;1:16–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kam NWS, Dai H. Carbon Nanotubes as Intracellular Protein Transporters: Generality and Biological Functionality. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:6021–6026. doi: 10.1021/ja050062v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tong AW, Jay CM, Senzer N, Maples PB, Nemunaitis J. Systemic Therapeutic Gene Delivery for Cancer: Crafting Paris' Arrow. Curr Gene Ther. 2009;9:45–60. doi: 10.2174/156652309787354630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tong AW, Zhang YA, Nemunaitis J. Small Interfering RNA for Experimental Cancer Therapy. Curr Opin Mol Ther. 2005;7:114–124. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bartlett DW, Davis ME. Impact of Tumor-Specific Targeting and Dosing Schedule on Tumor Growth Inhibition after Intravenous Administration of siRNA-Containing Nanoparticles. Biotechnol Bioeng. 2008;99:975–985. doi: 10.1002/bit.21668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Behlke MA. Progress Towards In Vivo Use of siRNAs. Mol Ther. 2006;13:644–670. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2006.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sun X, Pawlyk B, Xu X, Liu X, Bulgakov OV, Adamian M, Sandberg MA, Khani SC, Tan MH, Smith AJ, et al. Gene Therapy with a Promoter Targeting both Rods and Cones Rescues Retinal Degeneration Caused by AIPL1 Mutations. Gene Ther. 2010;17:117–131. doi: 10.1038/gt.2009.104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 25.Davis ME. The First Targeted Delivery of siRNA in Humans via a Self-Assembling, Cyclodextrin Polymer-Based Nanoparticle: From Concept to Clinic. Mol Pharm. 2009;6:659–668. doi: 10.1021/mp900015y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Aleku M, Schulz P, Keil O, Santel A, Schaeper U, Dieckhoff B, Janke O, Endruschat J, Durieux B, Roder N, et al. Atu027, a Liposomal Small Interfering RNA Formulation Targeting Protein Kinase N3, Inhibits Cancer Progression. Cancer Res. 2008;68:9788–9798. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-2428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Santel A, Aleku M, Keil O, Endruschat J, Esche V, Fisch G, Dames S, Loffler K, Fechtner M, Arnold W, et al. A Novel siRNA-Lipoplex Technology for RNA Interference in the Mouse Vascular Endothelium. Gene Ther. 2006;13:1222–1234. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3302777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kam NWS, Liu Z, Dai H. Functionalization of Carbon Nanotubes via Cleavable Disulfide Bonds for Efficient Intracellular Delivery of siRNA and Potent Gene Silencing. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:12492–12493. doi: 10.1021/ja053962k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhang Z, Yang X, Zhang Y, Zeng B, Wang S, Zhu T, Roden RBS, Chen Y, Yang R. Delivery of Telomerase Reverse Transcriptase Small Interfering RNA in Complex with Positively Charged Single-Walled Carbon Nanotubes Suppresses Tumor Growth. Clin Cancer Res. 2006;12:4933–4939. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-2831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Liu Y, Wu DC, Zhang WD, Jiang X, He CB, Chung TS, Goh SH, Leong KW. Polyethylenimine-grafted multiwalled carbon nanotubes for secure noncovalent immobilization and efficient delivery of DNA. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2005;44:4782–4785. doi: 10.1002/anie.200500042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zheng M, Jagota A, Semke ED, Diner BA, McLean RS, Lustig SR, Richardson RE, Tassi NG. DNA-Assisted Dispersion and Separation of Carbon Nanotubes. Nat Mater. 2003;2:338–342. doi: 10.1038/nmat877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zheng M, Jagota A, Strano MS, Santos AP, Barone P, Chou SG, Diner BA, Dresselhaus MS, McLean RS, Onoa GB, et al. Structure-Based Carbon Nanotube Sorting by Sequence-Dependent DNA Assembly. Science (Washington, DC, U S) 2003;302:1545–1548. doi: 10.1126/science.1091911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zheng M, Diner BA. Solution Redox Chemistry of Carbon Nanotubes. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126:15490–15494. doi: 10.1021/ja0457967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Strano MS, Zheng M, Jagota A, Onoa GB, Heller DA, Barone PW, Usrey ML. Understanding the Nature of the DNA-Assisted Separation of Single-Walled Carbon Nanotubes Using Fluorescence and Raman Spectroscopy. Nano Lett. 2004;4:543–550. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lustig SR, Jagota A, Khripin C, Zheng M. Theory of Structure-Based Carbon Nanotube Separations by Ion-Exchange Chromatography of DNA/CNT Hybrids. J Phys Chem B. 2005;109:2559–2566. doi: 10.1021/jp0452913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yamamoto Y, Fujigaya T, Niidome Y, Nakashima N. Fundamental Properties of Oligo Double-Stranded DNA/Single-Walled Carbon Nanotube Nanobiohybrids. Nanoscale. 2010;2:1767–1772. doi: 10.1039/c0nr00145g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shvedova A, Castranova V, Kisin E, Schwegler-Berry D, Murray A, Gandelsman V, Maynard A, Baron PJ. Exposure to Carbon Nanotube Material: Assessment of Nanotube Cytotoxicity using Human Keratinocyte Cells. Toxicol Environ Health, Part A. 2003;66:1909–1926. doi: 10.1080/713853956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mattson MP, Haddon RC, Rao AM. Molecular Functionalization of Carbon Nanotubes and Use as Substrates for Neuronal Growth. J Mol Neurosci. 2000;14:175–182. doi: 10.1385/JMN:14:3:175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cui D, Tian F, Ozkan CS, Wang M, Gao H. Effect of Single Wall Carbon Nanotubes on Human HEK293 Cells. Toxicol Lett. 2005;155:73–85. doi: 10.1016/j.toxlet.2004.08.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Magrez A, Kasas S, Salicio V, Pasquier N, Seo JW, Celio M, Catsicas S, Schwaller B, Forro L. Cellular Toxicity of Carbon-Based Nanomaterials. Nano Lett. 2006;6:1121–1125. doi: 10.1021/nl060162e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Oh SH, Finones RR, Daraio C, Chen LH, Jin S. Growth of Nano-Scale Hydroxyapatite Using Chemically Treated Titanium Oxide Nanotubes. Biomaterials. 2005;26:4938–4943. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2005.01.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lin Y, Taylor S, Li H, Fernando KAS, Qu L, Wang W, Gu L, Zhou B, Sun YP. Advances Toward Bioapplications of Carbon Nanotubes. J Mater Chem. 2004;14:527–541. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kostarelos K, Lacerda L, Partidos CD, Prato M, Bianco A. Carbon Nanotube-Mediated Delivery of Peptides and Genes to Cells: Translating Nanobiotechnology to Therapeutics. J Drug Delivery Sci Technol. 2005;15:41–47. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zhang L, Kiny VU, Peng H, Zhu J, Lobo RFM, Margrave JL, Khabashesku VN. Sidewall Functionalization of Single-Walled Carbon Nanotubes with Hydroxyl Group-Terminated Moieties. Chem Mater. 2004;16:2055–2061. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Martin CR, Kohli P. The Emerging Field of Nanotube Biotechnology. Nat Rev Drug Discovery. 2003;2:29–37. doi: 10.1038/nrd988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gasparac R, Kohli P, Paulino MOM, Trofin L, Martin CR. Template Synthesis of Nano Test Tubes. Nano Lett. 2004;4:513–516. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Cai D, Mataraza JM, Qin ZH, Huang Z, Huang J, Chiles TC, Carnahan D, Kempa K, Ren Z. Highly Efficient Molecular Delivery into Mammalian Cells using Carbon Nanotube Spearing. Nat Methods. 2005;2:449–454. doi: 10.1038/nmeth761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kohli P, Martin CR. Template-Synthesized Nanotubes for Biotechnology and Biomedical Applications. J Drug Delivery Sci Technol. 2005;15:49–57. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Fujigaya T, Yamamoto Y, Kano A, Maruyama A, Nakashima N. Template-Synthesized Nanotubes for Biotechnology and Biomedical Applications. Enhanced Cell Uptake Via Non-Covalent Decollation of a Single-Walled Carbon Nanotube-DNA Hybrid with Polyethylene Glycol-Grafted Poly(L-lysine) Labeled with an Alexa-Dye and its Efficient Uptake in a Cancer Cell. Nanoscale. 2011;3:4352–4358. doi: 10.1039/c1nr10635j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Noguchi Y, Fujigaya T, Niidome Y, Nakashima N. Single-Walled Carbon Nanotubes/DNA Hybrids in Water Are Highly Stable. Chem Phys Lett. 2008;455:249–251. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Schipper ML, Nakayama-Ratchford N, Davis CR, Kam NWS, Chu P, Liu Z, Sun X, Dai H, Gambhir SS. A Pilot Toxicology Study of Single-Walled Carbon Nanotubes in a Small Sample of Mice. Nat Nanotechnol. 2008;3:216–221. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2008.68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Singh R, Pantarotto D, Lacerda L, Pastorin G, Klumpp C, Prato M, Bianco A, Kostarelos K. Tissue Biodistribution and Blood Clearance Rates of Intravenously Administered Carbon Nanotube Radiotracers. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:3357–3362. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0509009103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lacerda L, Soundararajan A, Singh R, Pastorin G, Al-Jamal KT, Turton J, Frederik P, Herrero MA, Li S, Bao A, et al. Dynamic Imaging of Functionalized Multi-Walled Carbon Nanotube Systemic Circulation and Urinary Excretion. Adv Mater (Weinheim, Ger) 2008;20:225–230. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lacerda L, Ali-Boucetta H, Herrero MA, Pastorin G, Bianco A, Prato M, Kostarelos K. Tissue Histology and Physiology Following Intravenous Administration of Different Types of Functionalized Multiwalled Carbon Nanotubes. Nanomedicine (London, U K) 2008;3:149–161. doi: 10.2217/17435889.3.2.149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Sayes CM, Liang F, Hudson JL, Mendez J, Guo W, Beach JM, Moore VC, Doyle CD, West JL, Billups WE, et al. Functionalization Density Dependence of Single-Walled Carbon Nanotubes Cytotoxicity In Vitro. Toxicol Lett. 2006;161:135–142. doi: 10.1016/j.toxlet.2005.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Dumortier H, Lacotte S, Pastorin G, Marega R, Wu W, Bonifazi D, Briand JP, Prato M, Muller S, Bianco A. Functionalized Carbon Nanotubes Are Non-Cytotoxic and Preserve the Functionality of Primary Immune Cells. Nano Lett. 2006;6:1522–1528. doi: 10.1021/nl061160x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ahmad A, Kern K, Balasubramanian K. Selective Enhancement of Carbon Nanotube Photoluminescence by Resonant Energy Transfer. Chemphyschem. 2009;10:905–909. doi: 10.1002/cphc.200800796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kostarelos K. The Long and Short of Carbon Nanotube Toxicity. Nat Biotechnol. 2008;26:774–776. doi: 10.1038/nbt0708-774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Liu Z, Davis C, Cau W, He L, Chen X, Dai H. Circulation and Long-Term Fate of Functionalized, Biocompatible Single-Walled Carbon Nanotubes in Mice Probed by Raman Spectroscopy. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:1410–1415. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0707654105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Sato Y, Yokoyama A, Shibata K-i, Akimoto Y, Ogino S-i, Nodasaka Y, Kohgo T, Tamura K, Akasaka T, Uo M, et al. Influence of Length on Cytotoxicity of Multi-Walled Carbon Nanotubes Against Human Acute Monocytic Leukemia Cell Lne THP-1 in Vitro and Subcutaneous Tissue of Rats in Vivo. Mol BioSyst. 2005;1:176–182. doi: 10.1039/b502429c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Rether C, Sicking W, Boese R, Schmuck C. Self-Association of an Indole Based Guanidinium-Carboxylate-Zwitterion: Formation of Stable Dimers in Solution and the Solid State. Beilstein J Org Chem. 2010;6 doi: 10.3762/bjoc.6.3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Johnson RR, Johnson ATC, Klein ML. Probing the Structure of DNA-Carbon Nanotube Hybrids with Molecular Dynamics. Nano Lett. 2008;8:69–75. doi: 10.1021/nl071909j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Martin W, Zhu WS, Krilov G. Simulation Study of Noncovalent Hybridization of Carbon Nanotubes by Single-Stranded DNA in Water. J Phys Chem B. 2008;112:16076–16089. doi: 10.1021/jp8040567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Karachevtsev MV, Karachevtsev VA. Peculiarities of Homooligonucleotides Wrapping around Carbon Nanotubes: Molecular Dynamics Modeling. J Phys Chem B. 2011;115:9271–9279. doi: 10.1021/jp2026362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Xiao ZT, Wang X, Xu X, Zhang H, Li Y, Wang YH. Base- and Structure-Dependent DNA Dinucleotide-Carbon Nanotube Interactions: Molecular Dynamics Simulations and Thermodynamic Analysis. J Phys Chem C. 2011;115:21546–21558. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Zhao X, Johnson JK. Simulation of adsorption of DNA on carbon nanotubes. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129:10438–10445. doi: 10.1021/ja071844m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Kato Y, Inoue A, Niidome Y, Nakashima N. Thermodynamics on Soluble Carbon Nanotubes: How Do DNA Molecules Replace Surfactants on Carbon Nanotubes? Sci Rep. 2012;2 doi: 10.1038/srep00733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Swathi RS, Sebastian KL. Excitation Energy Transfer from a Fluorophore to Single-Walled Carbon Nanotubes. J Chem Phys. 2010;132 doi: 10.1063/1.3351844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Georgakilas V, Tagmatarchis N, Pantarotto D, Bianco A, Briand J-P, Prato M. Amino Acid Functionalization of Water Soluble Carbon Nanotubes. Chem Commun (Cambridge, U K) 2002:3050–3051. doi: 10.1039/b209843a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Sarin VK, Kent SBH, Tam JP, Merrifield RB. Quantitative Monitoring of Solid-Phase Peptide Synthesis by the Ninhydrin Reaction. Anal Biochem. 1981;117:147–157. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(81)90704-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Leona M. Microanalysis of Organic Pigments and Glazes in Polychrome Works of Art by Surface-Enhanced Resonance Raman Scattering. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:14757–14762. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0906995106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Londero P, Lombardi JR, Leona M. A Compact Optical Parametric Oscillator Raman Microscope for Wavelength-Tunable Multianalytic Microanalysis. J Raman Spectrosc. Ahead of Print. [Google Scholar]

- 73.Mas MT, Colman RF. Spectroscopic Studies of the Interactions of Coenzymes and Coenzyme Fragments with Pig-Heart, Oxidized Triphosphopyridine Nucleotide Specific Isocitrate Dehydrogenase. Biochemistry. 1985;24:1634–1646. doi: 10.1021/bi00328a011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Nimmagadda A, Thurston K, Nollert MU, McFetridge PS. Chemical Modification of SWNT Alters In Vitro Cell-SWNT Interactions. J Biomed Mater Res, Part A. 2006;76A:614–625. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.30577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Murugesan S, Park TJ, Yang H, Mousa S, Linhardt RJ. Blood Compatible Carbon Nanotubes - Nano-based Neoproteoglycans. Langmuir. 2006;22:3461–3463. doi: 10.1021/la0534468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Britz DA, Khlobystov AN. Noncovalent Interactions of Molecules with Single Walled Carbon Nanotubes. Chem Soc Rev. 2006;35:637–659. doi: 10.1039/b507451g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Li H, Zhou B, Lin Y, Gu L, Wang W, Fernando KAS, Kumar S, Allard LF, Sun YP. Selective Interactions of Porphyrins with Semiconducting Single-Walled Carbon Nanotubes. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126:1014–1015. doi: 10.1021/ja037142o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Nakayama-Ratchford N, Bangsaruntip S, Sun X, Welsher K, Dai H. Noncovalent Functionalization of Carbon Nanotubes by Fluorescein-Polyethylene Glycol: Supramolecular Conjugates with pH-Dependent Absorbance and Fluorescence. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129:2448–2449. doi: 10.1021/ja068684j. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Boul PJ, Cho DG, Rahman GMA, Marquez M, Ou Z, Kadish KM, Guldi DM, Sessler JL. Sapphyrin-Nanotube Assemblies. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129:5683–5687. doi: 10.1021/ja069266h. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Yang R, Jin J, Chen Y, Shao N, Kang H, Xiao Z, Tang Z, Wu Y, Zhu Z, Tan W. Carbon Nanotube-Quenched Fluorescent Oligonucleotides: Probes that Fluoresce upon Hybridization. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:8351–8358. doi: 10.1021/ja800604z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Ahmad A, Kurkina T, Kern K, Balasubramanian K. Applications of the Static Quenching of Rhodamine B by Carbon Nanotubes. Chemphyschem. 2009;10:2251–2255. doi: 10.1002/cphc.200900246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Sprafke JK, Stranks SD, Warner JH, Nicholas RJ, Anderson HL. Noncovalent Binding of Carbon Nanotubes by Porphyrin Oligomers. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2011;50:2313–2316. doi: 10.1002/anie.201007295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Hall HK. Correlation of the Base Strengths of Amines. J Am Chem Soc. 1957;79:5441–5444. [Google Scholar]

- 84.Jang YH, Blanco M, Dasgupta S, Keire DA, Shively JE, Goddard WA. Mechanism and Energetics for Complexation of Y-90 with 1,4,7,10-tetraazacyclododecane-1,4,7,10-tetraacetic acid (DOTA), a Model for Cancer Radioimmunotherapy. J Am Chem Soc. 1999;121:6142–6151. [Google Scholar]

- 85.Loukas YL. Multiple complex formation of fluorescent compounds with cyclodextrins: Efficient determination and evaluation of the binding constant with improved fluorometric studies. J Phys Chem B. 1997;101:4863–4866. [Google Scholar]

- 86.Alderfer JL, Hazel GL. Non-Equivalence of P-31 Nmr Chemical-Shifts of Rna Complexes. J Am Chem Soc. 1981;103:5925–5926. [Google Scholar]

- 87.Lerner DB, Kearns DR. Observation of Large Solvent Effects on the P-31 Nmr Chemical-Shifts of Nucleotides. J Am Chem Soc. 1980;102:7611–7612. [Google Scholar]

- 88.Lerner DB, Becktel WJ, Everett R, Goodman M, Kearns DR. Solvation Effects on the P-31-Nmr Chemical-Shifts and Infrared-Spectra of Phosphate Diesters. Biopolymers. 1984;23:2157–2172. doi: 10.1002/bip.360231105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Filman DJ, Bolin JT, Matthews DA, Kraut J. Crystal-Structures of Escherichia-Coli and Lactobacillus-Casei Dihydrofolate-Reductase Refined at 1.7 a Resolution .2. Environment of Bound Nadph and Implications for Catalysis. J Biol Chem. 1982;257:13663–1372. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Feeney J, Birdsall B, Roberts GCK, Burgen ASV. P-31 Nmr-Studies of Nadph and Nadp+ Binding to L-Casei Dihydrofolate-Reductase. Nature (London) 1975;257:564–566. doi: 10.1038/257564a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Gerothanassis IP, Birdsall B, Feeney J. Hydrogen-Bonding Effects on P-31 Nmr Shielding in the Pyrophosphate Group of Nadph Bound to Lactobacillus-Casei Dihydrofolate-Reductase. Febs Lett. 1991;291:21–23. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(91)81094-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Gueron M, Shulman RG. Magnetic-Resonance of Transfer-Rna. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1975;72:3482–3485. doi: 10.1073/pnas.72.9.3482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.