Abstract

Nursing home (NH) residents with dementia continue to receive inadequate pain treatment. The purpose of this qualitative study was to examine how nurses make decisions to pharmacologically treat pain in NH residents with dementia. Using Grounded Dimensional Analysis, 15 in-depth interviews were conducted with 13 nurses from 4 Skilled Nursing Facilities in Wisconsin. Nurses experienced varying levels of certainty regarding suspected pain in response to certain resident characteristics and whether pain was perceived as visible/obvious or non-visible/not obvious. Nurses felt highly uncertain about pain in residents with dementia. Suspected pain in residents with dementia was nearly always conceptualized as a change in behavior which nurses responded to by trialing multiple interventions in attempts to return the resident to baseline, which despite current recommendations, did not include pain relief trials. Residents with dementia were described as being at greatest risk for experiencing underassessment, undertreatment and delayed treatment for pain.

Keywords: dementia, nursing homes, pain management, decision-making

Background

Pain is a commonly occurring symptom among older persons which is largely the result of functional age-related changes and the development of chronic conditions (American Geriatrics Society Panel on the Pharmacological Management of Persistent Pain in Older Persons, 2009). Estimates of the prevalence of daily pain in community dwelling older persons range from 32 to 56% while estimates of pain in older persons living in nursing homes range from 60 to 70% (Kruger & Stone, 2008; Takai et al. 2010). Untreated and undertreated pain in older persons has a serious negative impact on health, functioning, and quality of life; contributing to depression, social isolation, sleep disturbances, and functional and cognitive impairment (Gibson & Weiner, 2005; Herr & Garand, 2000). Older people living in nursing homes (NH) are at high risk for experiencing poor pain management as a result of system-related barriers such as incomplete medical records and highly burdened staff with limited resources (Ferrell, 2000). This risk increases further for residents with dementia whose ability to reason and communicate their needs is often compromised, diminishing their ability to recognize and report pain (Bachino, Snow, Kunrk, Cody, & Wristers, 2001; Horgas & Elliot, 2004).

Research has consistently documented the high prevalence of underassessment and pharmacologic undertreatment of pain in NH residents with dementia (Reynolds, Hanson, DeVellis, Henderson, & Steinhauser, 2008; Williams, Zimmerman, Sloane, & Reed, 2005; Wu, Miller, Lapane, Roy, & Mor, 2005). Misconceptions about pain and aging, stoical attitudes, inadequate training and underuse of appropriate assessment tools present barriers to effective pain assessment and treatment in older persons with dementia (McAuliffe et al., 2008). Collectively, this research has made a compelling case for the need to develop and implement more suitable pain assessment strategies for persons with dementia. Over the last decade, researchers have made significant advancements in this area through the development, evaluation and dissemination of numerous assessment tools designed to recognize behavioral pain indicators in nonverbal older persons (Herr, Bjoro, & Decker, 2006; Herr, Bursch, & Black, 2008; Herr, Bursch, Ersek, Miller, & Swafford, 2010). Despite the availability of these tools and clear guidelines for their use, an alarming number of residents are still experiencing poor pain management (American Geriatrics Society Panel on the Pharmacological Management of Persistent Pain in Older Persons, 2009; American Medical Directors Association, 2009; Hadjistavropoulos et al., 2011).

Research suggests that there is a discrepancy between nurses’ identification of pain indicators in persons with dementia and their decisions to provide analgesics (Kaasalainen et al., 1998; McCaffery, Ferrell, & Pasero, 2000). Horgas and Tasi (1998) found that even when controlling for number of painful conditions, NH residents with cognitive impairment received significantly fewer analgesics than residents without cognitive impairment. Research has focused largely on the assessment of pain but few empirical studies have examined reasons for the continued inadequacy of pharmacologic treatment of pain for NH residents with dementia. One grounded theory study conducted by Kaasalainen and colleagues (2007) examined long-term care physician and nurse attitudes and beliefs about prescribing and administering pain medication in long-term care. They identified several barriers to effective treatment including underrecognition of pain, uncertainty regarding pain assessment and diagnosis and discomfort with opioid use (Kaasalainen et al., 2007). No study, however, has explored nurse decision-making about providing analgesics to persons with dementia. Identifying reasons for the inconsistency between nurses’ identification of pain indicators in residents with dementia and the actions they take related to treatment can inform interventions to improve pain management for this vulnerable population. Please note that ‘treatment’ throughout this article refers to the provision of analgesics, while acknowledging that other treatment modalities are available.

The purpose of this study was to examine how nurses make decisions to pharmacologically treat pain in NH residents with dementia as well as to identify the conditions that influence treatment decisions and to develop a conceptual model that can guide future research and clinical practice.

Method

Research Design

This study employed a qualitative design, Grounded Dimensional Analysis, to explore the understandings nurses have about pain in persons with dementia, the actions they take in relation to those understandings, and how the two are related (Caron & Bowers, 2000). Another major goal of this research was to identify conditions that influence nurses’ actions relating to pain management. These aims are well suited for Grounded Dimensional Analysis (Caron & Bowers, 2000; Schatzman, 1991). Grounded Dimensional Analysis is a qualitative methodology that was developed as an alternative to grounded theory. It is similar in that it shares a Symbolic Interactionist foundation and is designed specifically to generate theory about how social understandings guide actions and to identify consequences associated with various actions. The end product of Grounded Dimensional Analysis is a conceptual model that explains the phenomenon of interest (Bowers & Schatzman, 2008).

Sample and Setting

Fifteen in-depth interviews were conducted with 13 nurses from 4 Skilled Nursing Facilities in Wisconsin. The only eligibility criterion for nurse participants was that they be licensed nurses (practical or registered nurses) with experience caring for NH residents with dementia. Both practical and registered nurses were included because practical nurses compose about half of the licensed nurse workforce in NHs (Rantz et al., 2004) and despite clear differences in scope of practice, practical nurses often function in a similar capacity as registered nurses (Corazzini et al., 2010). The study was determined to be exempt from review by the University of Wisconsin-Madison Institutional Review Board as no identifiable patient or nurse information was collected. As a result, no demographic information was collected from participants outside of what was needed to ascertain eligibility. Researchers worked in collaboration with Directors of Nursing to recruit participants.

Interviews were conducted with participants in a private room at their place of work at a time that was convenient for them. Participants were asked to participate in one to two interviews and received a $15 honorarium per interview. Interviews were audiotaped and transcribed verbatim. Two participants were interviewed twice; these follow-up interviews were used to engage in verification strategies such as member checking, to ensure fit with the developing conceptual model, and to pursue new questions that arose during analysis.

Both convenience and theoretical sampling were used throughout the study. Participants were recruited by convenience sampling through e-mails from their Director of Nursing, flyers posted in designated workspaces and an announcement about the study at one staff meeting. Theoretical sampling involves the pursuit of data that will provide opportunities for constant comparative analysis, a process fundamental to grounded theory analysis (Strauss, 1987). Constant comparative analysis involves the pursuit of variability and complexities inherent in the phenomenon being studied (Strauss, 1987). Theoretical sampling can be achieved through identification of participants with relevant experience or through modifying interview questions to maximize comparisons, sampling for variations in experiences or events with a single participant. In this study, theoretical sampling was pursued primarily by modifying interview questions. For example, if a participant recounts a treatment decision involving a resident with very severe dementia who recently underwent surgery the investigator would explore how that differs from a resident with no dementia or mild dementia post-surgery. Thus, asking a single participant to provide details of the two separate situations and to explain and compare how each is approached, provides a comparative sample. Researchers relied primarily on theoretical saturation of the core category to determine the appropriate sample size but also considered other important data elements, including the quality of the data (which was rich and descriptive), the scope of the core category of interest (which was specific and not too broad), the use of shadowed data (which was fairly common), and the complex nature of the topic (which is complex) (Morse, 2000).

Data Collection and Analysis

In conducting Grounded Dimensional Analysis, data collection and analysis occur simultaneously and cyclically (Schatzman, 1991; Strauss, 1987). That is, data are analyzed following each interview, allowing the researcher to pursue questions in subsequent interviews that are informed by the development of the conceptual model. Analysis progressed through several non-linear phases: open, axial and selective coding. Open coding focused on the discovery and description of categories and their characteristics (dimensions). Axial coding involved the exploration of conditions that influence the social process (pain management) and consequences related to different conditions and decisions. The primary goal of axial coding was to explore the interactions between different dimensions, conditions and decisions in a variety of social situations that influenced these relationships. After conducting several very open interviews using these analytic procedures, selective coding became the focus of analysis. During selective coding, identifying a central social process or core category became the primary goal of analysis.

Toward the beginning of the study, line-by-line open coding techniques were used to analyze the data to ensure that the products of analysis were consistent with the data (Strauss, 1987). The first of several interviews opened by asking participants broad, non-directive questions such as: “Tell me about your experience working as a nurse.” Most participants began by describing positions they have held and different nursing duties such as assessment and treatment. Other initial categories that resulted from open coding were supervising, becoming aware of problems and identifying different sources of information through which nurses’ became aware of issues such as pain. As interviews progressed and analysis shifted towards axial coding, more direct questions were asked about nursing duties surrounding pain management which highlighted nurses’ typing of residents (dementia/no dementia, drug seeking/not drug seeking, short stay/long-term stay) and pain (visible/obvious or non-visible/not obvious). Participants also described inability to communicate due to other conditions such as aphasia or trauma as challenging for pain management, however, this study focused only on communication difficulties due to dementia.

These categories informed subsequent theoretical sampling decisions, interview questions and the selection of the core category: responding to pain that presents as a change in behavior. Data collection and analysis continued until this core category was theoretically saturated. Throughout the research process, conceptual diagrams were developed and continually revised in light of new evidence. These conceptual diagrams were also used for member checking at different points in theory development. Member checking was achieved by presenting conceptual diagrams to participants at the end of interviews to verify accuracy of the relationships among categories and to stimulate the identification of other relevant categories not previously identified. Several methodological strategies were implemented to ensure that data analysis procedures were rigorous and appropriately represented the data collected. Among these were the use of an interdisciplinary research group to analyze data and member checking. Author Gilmore-Bykovskyi also maintained ongoing memos to document theoretical and methodological decisions.

Findings

Summary of Findings

A total of 15 interviews were conducted with 13 nurses from 4 Skilled Nursing Facilities in Wisconsin. Three nurses were LPNs and the 10 were RNs. Across findings, there were no notable differences in responses from LPN versus RN participants. All participants worked in facilities that were part of a larger Continuing Care Retirement Community (CCRC). Interviews ranged from 40 to 96 minutes in length.

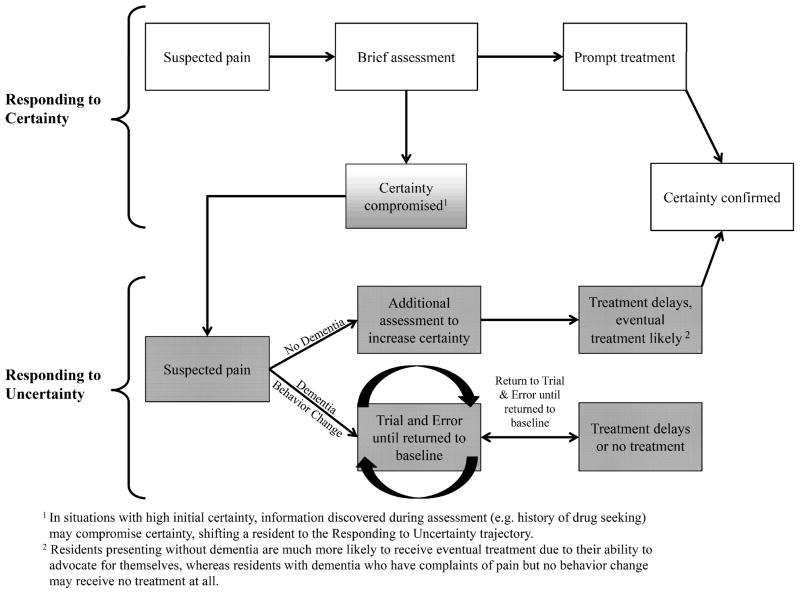

A conceptual model (Figure 1) was developed to illustrate the process nurses engage in while identifying and deciding whether or not to treat pain in NH residents with dementia. The model describes how nurses’ perceived level of certainty regarding suspected pain influences treatment decisions. Nurses perceived level of certainty about the presence of pain was the most significant factor in determining whether and how quickly a resident’s pain would be treated pharmacologically. Resident characteristics as well as presence or absence of an obvious reason for pain, influenced the nurses’ levels of certainty regarding pain. Visible/obvious reasons for pain were considered to exist when a resident had a condition or experience for which pain is widely known to be an expected outcome, such as recent surgery. Major concepts of the conceptual model are defined with examples in Table 1.

Figure 1.

Table 1.

The Process Nurses Engage in to Identify and Decide to Pharmacologically Treat Pain in Residents with Dementia: Major Concepts

| Concept | Definition | Examples Provided by Participants |

|---|---|---|

| Pain indicators: behaviors suggestive of pain | Verbal and non-verbal behaviors that nurses perceive as being suggestive of pain. | Grimacing Bracing body part Repetitive rubbing of a body part Clenching jaw or fist |

| Pain indicators: behaviors highly suggestive of pain | Verbal and non-verbal behaviors that nurses perceive as being highly suggestive pain, particularly when one or more behavior is displayed. | Crying Verbal complaints of pain Intense guarding with care |

| Pain indicators: general behavior changes | Behaviors that nurses described as representing a general shift from baseline functioning in a person with dementia. Often considered to be vague but indicative of an underlying problem. | Changes in sociability Withdrawal Negative vocalizations Restless behaviors Agitation |

| Visible/obvious reason for pain | Conditions or recent experiences for which pain is widely known to be an expected outcome. Many, but not all conditions described contained some type of visible damage. | Surgical operations Hip Fracture Actively dying |

| Non-Visible/not obvious reason pain | Conditions or recent experiences for which pain is an expected outcome. | Osteoarthritis Diabetic neuropathy Chronic back pain Fibromyalgia |

| Certainty/uncertainty regarding suspected pain | The degree to which nurses feel they can be certain that pain is likely present. Resident characteristics and characteristics of pain (obvious or not-obvious) contribute to nurses’ degree of certainty. | Uncertain regarding accuracy of self- report from resident with dementia Less certain regarding self-report from a resident with a history of drug seeking Very certain regarding suspected pain in a resident who is actively dying |

| Treatment delays | Treatment delays occurred as a result of additional steps nurses went through in responding to behavior changes and suspected pain in residents with dementia. | Waiting “a few shifts or days” before requesting medication regimen changes for a resident displaying agitation due to a perceived lack of certainty that pain was the underlying cause of agitation. |

The most salient resident characteristics were whether a resident: (1) was a long-term stay resident or short stay residents (2) had dementia (3) had a history of drug-seeking, and (4) was actively dying (See Table 2). Nurses described engaging in different assessment and treatment procedures in response to whether they had generally high or low levels of certainty regarding the presence of pain leading to two distinct treatment trajectories: (1) Responding to Uncertainty and (2) Responding to Certainty (Figure 1). The Responding to Uncertainty trajectory led to treatment delays and generally occurred with patients who were long-term stay and/or had dementia and/or had a history of drug-seeking, and/or had no visible/obvious reason for pain. Responding to Certainty led to prompt treatment and usually occurred with residents who were short stay and/or did not have dementia and/or were actively dying, and/or had a visible/obvious reason for pain.

Table 2.

Resident and pain characteristics that influence nurses’ certainty regarding the presence of pain.

| Resident Characteristics | Influence on Certainty |

|---|---|

| Long-term resident | Less certain because pain is not anticipated and rarely visible, more thorough assessment undertaken. |

| Short stay resident | More certain because resident is more likely to have an obvious reason for pain, less likely to have dementia, more likely to need regular pain treatment and to have pain medication ordered. |

| Dying resident* | Very certain, leading to prompt treatment. |

| Drug-seeking resident | Less certain, undergo additional assessment to increase certainty, likely to experience treatment delays. |

| Presence of dementia | Highly uncertain, considered to be a situation wherein certainty is impossible, more complicated assessment takes place in addition to a process of trial and error with multiple interventions if pain presents as a behavior change. |

| Characteristics of Pain | Influence on Certainty |

| Visible or obvious reason for pain* | More certain when pain has a visible origin, assessment treatment are more prompt. |

| Non-visible, not obvious reason pain | Less certain and more thorough assessment undertaken. |

These conditions appear to be dominant and their corresponding influence on certainty and assessment are likely to superimpose other co-existing conditions.

Nurses’ identification of pain in residents with dementia relied heavily on the display of 3 types of pain indicators: (1) behaviors suggestive of pain, (2) behaviors highly suggestive of pain and (3) general behavior changes (See Table 1 for examples). Nurses described general behavior changes as indicative of possible pain but also potentially related to other causes. Examples of general behavior changes included withdrawal, restless behaviors and negative vocalizations. Nurses described these different types of pain indicators when directly asked how they perceive signs of pain persons with dementia. Without guidance from the interviewer, however, nurses conceptualized any type of pain indicator exhibited by a person with dementia as a behavior change. Even in situations when residents with dementia self-reported pain, nurses still conceptualized their pain and these reports as representing a change in normal behavior. Nurses felt uncertain about the reliability of physical complaints from persons with dementia and about whether pain was the cause for behavior changes. As a result, even though they identify pain indicators in residents with dementia, nurses generally had very low levels of certainty regarding suspected pain for these residents. The presence of pain indicators was not routinely sufficient to trigger pharmacologic intervention. In response to suspected pain, nurses attempted various, non-sequenced interventions to try to relieve behavior changes which didn’t always include analgesics. As a result of this “trial and error” process, analgesics that were provided to residents with dementia would often be delayed.

The goals of assessment and treatment also varied in response to whether or not a resident had dementia. In the absence of dementia for both characteristics associated with certainty and uncertainty, the purpose of assessment and treatment activities was to confirm certainty regarding pain and/or verify effectiveness of treatment. In the presence of dementia, however, the goal of assessment and treatment shifted towards returning the resident to baseline functioning by reducing or eliminating behavioral symptoms. Interestingly, although nurses felt very uncertain about their ability to confirm suspected pain in residents with dementia, they did not pursue certainty or routinely document effectiveness of interventions for residents with dementia. Nurses expressed feeling that it was nearly impossible to establish certainty regarding the underlying causes of pain indicators in residents with dementia. In situations when residents displayed pain indicators highly suggestive of pain nurses suspected pain more strongly and were more likely to provide prompt treatment although the focus of treatment remained returning the resident to baseline.

Responding to Uncertainty

Consistently, residents (1) with dementia or (2) who were perceived by nurses to be drug-seeking or (3) or were long-term residents, or (4) had no obvious or visible reason for pain fell into the Responding to Uncertainty trajectory. This trajectory produces further, more comprehensive assessments, and delayed or no treatment. While treatment delays were not explicitly measured in this study, they were spontaneously reported to occur by most participants. The extent of treatment delays was elicited by examining additional processes nurses described engaging in when responding to uncertainty, which invariably took additional time to complete.

Long-term residents were understood to have conditions that might contribute to the experience of persistent pain. However, because pain generally was not anticipated in long-term residents and usually was not obvious or visible, nurses considered its occurrence to be abnormal and necessitate more extensive assessment:

Most of our patients here are rehab…they’ve had new hips, knees, they’ve had strokes. They’re tiny little frail bodies I mean they have to have pain…Just plain long term folks those are people that are there to live…they may have arthritis, Parkinson’s… and many of those diseases result in pain…but it takes a good body assessment to figure out why someone whose long term and whose not supposed to be in pain, why are they in pain?

Nurses considered pain to be easier to assess and treat in residents with visible/obvious reasons for pain and with residents who could accurately report the effectiveness of treatment. Nurses described feeling highly uncertain regarding pain in persons with dementia due to a perceived inability to accurately interpret and answer assessment questions and felt it was impossible to ever achieve certainty in the absence of a more obvious reason for pain:

And we do have a lot of people with chronic pain too like arthritis, neuropathies, old fractures… scheduled pain meds are for people with the more severe pain…some of the long-term people can’t speak anymore then you’re relying more on whether they grimace or whether they moan, look comfortable…it’s harder to judge their pain. They can’t tell you so even if you think they’re in pain – you don’t know. Easy is when they can tell you and they’re showing the signs and symptoms. They have the evidence, they have had surgery, they’ve got a gaping wound, they’re telling you it’s a ten or an eight and when you see results—you give them the pain pill, you go back and they say ‘well now it’s a two.’…those are the easy ones.

Whether a resident is considered to be drug-seeking appeared to have more direct implications for the time to treatment. Residents with a history of drug-seeking or who display drug-seeking behaviors (e.g. routinely asking for prn pain medication in more frequent intervals than ordered while not appearing to have substantial pain). These patients were described as experiencing additional assessments and delays in treatment, “…I’m not gonna run down there and give them that pain pill, they can wait… [I] may be a little slower.”

Resident and pain characteristics associated with uncertainty had an additive effect on the extent of treatment delays. Behaviors highly suggestive of pain generally resulted in more prompt analgesia, however, when in addition to dementia a resident had no obvious reason for pain or a history of drug seeking, nurses experienced increased uncertainty which produced greater treatment delays. Of the 4 characteristics associated with uncertainty, dementia was described as being the greatest deterrent to prompt pain treatment. Residents with no obvious reason for pain, a history of drug seeking, or who were long-term without dementia were described as receiving eventual but less automatic treatment, which may even have taken the form of deliberately delayed treatment. Comparatively, residents with dementia were described as very likely to receive delayed treatment and in some instances unlikely to receive any treatment.

Nurses Understanding of Pain and Decisions to Treat in Residents with Dementia

Nurses often learned about suspected pain in residents with dementia as the result of a behavior change or because of a resident complaint. Regardless of variation in the symptoms or presenting complaints of suspected pain in residents with dementia, it was almost exclusively discussed and responded to as representing a change in behavior. Only one deviation to this response was described which involved residents who both had dementia and were actively dying, a characteristic that led to the Responding to Certainty Trajectory. Nurses described feeling very uncertain regarding their ability to confirm the presence of pain and its’ etiology for residents with dementia. Nurses’ strategies for assessing pain in residents with dementia varied, and in some instances they did not attempt to gather any verbal information:

It’s a lot easier when they’re intact to just explain to them on a scale… I don’t even ask the question of someone who’s demented because they wouldn’t understand it anyway… so I look at their body language, their facial expressions, how they’re responding to you, to your touch, to your trying to care for them.

Changes in behavior were consistently considered to be indications of some underlying discomfort, psychosocial unrest (e.g. altercation with another resident), or pathophysiologic change. Nurses considered pain to be only one of a number of potential causative agents for behavioral changes and explained that it is likely that a combination of these factors contribute to behavior changes. In response to suspected pain in residents with dementia, nurses embarked on a trial and error approach which involves piloting different combinations of pharmacologic and non-pharmacologic interventions to relieve the underlying discomfort. Among the interventions they described are: toileting, adjusting room to suit patient preferences, offering a low-dose of Tylenol, repositioning, adjusting temperature and thermal comfort, increasing or decreasing stimulation, taking the resident outdoors or changing environment, offering food, and checking for signs of acute illness if behaviors are from baseline (e.g. pneumonia, UTI). Interestingly, although nurses did not think it was possible to pinpoint the exact causes of the behavior change, they considered a return to baseline to indicate that some combination of interventions performed during the trial and error process had relieved the causes of behavior. The following quotation elucidates this process:

Well with the demented resident, I think you have to narrow it down. You have to toilet them. You have to bring them food. You have to offer a back rub. Some of them a pain pill isn’t going to help if they still have to go to the toilet, if they’re still hungry. You turn on the light, I might get ice cream. I might turn on the television, along with that I would give them a pain pill… if they’re restless or have a temp, maybe they’re having discomfort from a UTI. So it’s a matter of elimination….It is kind of a hit and miss.

Nurses continued the trial and error process until the behaviors resolved. Most nurses stated that there is no specific order to these interventions, but some discussed adopting an individualized approach, wherein they would first try interventions known to be successful in the past. If significant time passed without resolution of the behaviors, nurses would contact a supervisor, or a nurse practitioner/physician. Some nurses provided estimates of this delay as commonly being two to three 8-hour shifts. N did not consider the use of analgesics harmful in the event that pain cannot be established as the cause for behavior change, “there is no order, you have to deal with what’s pertinent at hand… I may give them the pain pill… I don’t think we’re hurting anybody by giving them a pain pill if they don’t have pain.”

Residents who displayed general behavior changes that were vague in nature (e.g. being withdrawn or disengaged) were described as being the least likely to receive analgesics or as experiencing the longest delays in time to treat. Hypoactive behavioral changes were also less likely to suggest the need for pain treatment and nurses highlighted the importance of developing relationships with residents to facilitate recognition of these more silent presentations of behavior change:

I think that the demented resident who cannot complain sometimes is forgotten …especially the ones that are quiet. I think the ones that strike out and are combative, any nurse can [figure out] maybe the pain is causing this behavior… there are so many things we can look at with dementia. Do they need to go to the toilet? Are they hungry? Is there something wrong with the room that they’re afraid of? Building a trustful relationship with the staff is very important for [pain] management.

The consequences of the Responding to Uncertainty trajectory for a resident with dementia may include underrecognition and undertreatment of pain as well as treatment delays. Because many interventions occur simultaneously and little effort is made to evaluate the effectiveness of individual interventions, it is unclear whether staff are able to establish patterns in individual residents’ behaviors that would facilitate the development of more individualized responses. Only when behavior changes remain unresolved and pain is the suspected cause did nurses described documentation of treatment and outcomes over a period of time. Nurses said that it would commonly take one to two days for a pattern to be established which would merit implementing new pain medication orders.

Responding to Certainty

Nurses described a process of prompt treatment for residents without dementia, and/or those who are short stay, and/or those who are actively dying, and/or residents considered to have visible/obvious reasons for pain. Nurses described responding to obvious reasons for pain with high levels of certainty, consequently expediting treatment. Although nurses recognized that not all short-stay residents are cognitively intact with obvious reasons for pain, they consistently dichotomized long-term and short stay residents into different treatment trajectories. Suspected pain that occurs in the context of resident and pain characteristics associated with certainty was responded to by conducting a brief assessment (generally by using a 0–10 pain rating scale), offering prompt treatment, and following-up to confirm certainty and/or verify effectiveness (See Figure 1).

The absence of dementia produces a strong influence on decisions to treat because of non-demented residents’ ability to communicate. Even if a visible/obvious reason for pain was not apparent and nurses had a low level of certainty regarding suspected pain, residents without dementia were reported to receive prompt treatment for two reasons: (1) because they could reason and communicate clearly and (2) because they were able to advocate for themselves.

Visible/Obvious Pain: A Dominant Condition

The presence of a visible and obvious reason or pain was a dominant condition that could shift residents who would generally be prone to the Responding to Uncertainty into the Responding to Certainty trajectory. For example, a resident with severe dementia with a recent surgically repaired hip fracture or who is actively dying would be considered to have obvious and visible pain therefore more likely to receive prompt analgesic treatment. Nurses commented that overall, however, residents with obvious reasons for pain and dementia may receive somewhat less treatment for other reasons including: limited or absent ability to verbalize pain or request treatment, only being formally assessed by a nurse once per shift, and hypoactive or vague presentation of pain.

Discussion

Findings from this study provide important insights into how nurses conceptualize pain in NH residents with dementia and their decisions to provide pharmacologic treatment in several Skilled Nursing Facilities in Wisconsin. Findings also highlight reasons for continued inadequate pain treatment for NH residents without dementia with various chronic diseases that were perceived by nurses in this study to have few obvious reasons for pain. Nurses that were interviewed in this study were most uncertain about the likelihood of pain in residents with dementia who were also at greatest risk for experiencing underassessment, undertreatment and delayed treatment for pain.

Participants’ uncertainty regarding the accuracy of self-report in persons with dementia was exacerbated by a general inability to differentiate between behavioral presentations that merited analgesic interventions and those that did not. Nurses in this study described the reality of pain management from their perspective. This conceptualization of pain sheds some light on potential reasons for continued disproportionately low levels of analgesic treatment for NH residents with dementia. Under the condition of dementia, nurses encountered pain in the context of behavior change. The actions that they undertake, specifically the process of trial and error to relieve behaviors are likely responsive to the irregularity, vagueness and complexity of the presenting behaviors.

Practice recommendations highlight the utilization of nonpharmacologic interventions as first line therapy for behavioral symptoms of dementia as antipsychotics that are often used to address these symptoms are not effective in improving functioning, decreasing care needs or improving quality of life and are associated with numerous adverse side effects (Salzman et al., 2008). There is growing recognition, however, that other pharmacologic interventions, particularly analgesics are both necessary and appropriate as research suggests that acute physical problems such as pain are a common cause of behavioral symptoms (Kovach et al., 2006; Kovach, Logan, Simpson, & Reynolds, 2010). Nurses in this study did not prioritize assessment and treatment of physical problems but did consider numerous non-physical etiologies for behavioral changes such as psychosocial or environmental imbalance. This approach may be reflective of care foci in the NH environment, where the basis for many care interactions is a relationship between staff and the resident rather than the intersection of illness and treatment more commonly seen in acute care settings. To that point, it is important to add that all nurses in this study described dedicated and thorough attempts to maintain resident’s wellbeing by meeting what they considered to be a variety of unmet needs. This suggests important implications for future intervention work: acknowledging and appreciating for nurses genuine concern regarding resident’s needs is likely central to achieving the buy-in necessary to effect change in nurses pain management practices. More empirical examination of how nurses in this environment encounter and respond to pain indicators and dementia-related behavioral symptoms is needed to ensure that interventions to improve pain and symptom management are responsive to the real-world needs of the NH work environment.

Nurses in this study did not have clear procedures for assessing pain, responding to pain indicators and behavior changes, or prioritizing interventions. It is also clear that a large degree of inconsistency abounds regarding the provision of different interventions in response to pain indicators and behavioral symptoms which suggests that nurses might benefit from easily accessible decision-support algorithms that integrate guidelines for both pain and behavioral symptom management. Algorithms could help nurses decide when to implement which types of interventions (pharmacologic and non-pharmacologic) and in which order. An example of a decision-support intervention that follows an algorithmic model is the Serial Trial Intervention, a clinical protocol for assessing and treating unmet needs symptoms in persons with severe dementia (Kovach et al., 2006).

Findings from this study suggest that uncertainty about the likelihood of pain and accuracy of self-report in persons with dementia present major barriers to prompt treatment. Similar to findings from other studies, uncertainty played a significant role in staff’s perception of pain (Clark, 2004; Kaasalainen, et al., 2007). Findings from this study expand this knowledge by providing information about how uncertainty influences treatment: in uncertain situations nurses in this study described deliberately delaying treatment decisions or negating treatment in certain situations such as with drug seeking behaviors. This finding suggests that certain attitudes/beliefs towards drug seeking behaviors are a clear barrier to proper pain management. Although persons with mild-to-moderate cognitive impairment are able to provide reliable pain reports over time (Weiner, Peterson, Logue, & Keefe, 1998) some nurses in this study felt so uncertain about the reliability of self-report in residents with dementia that they reported regularly failing to ask any direct questions about pain.

Nurses in this study felt little to no need to validate the effectiveness of treatment but rather focused their efforts on returning the resident to baseline. This practice limits the degree to which future interventions can be individualized. Consistent with findings from other qualitative studies (Clark, L., Jones, K., Pennington, K., 2004; Parke, B., 1998; Kovach, Griffie, Muchka, Noonan, & Weissman, 2000), personal knowledge and the use of an individualized approach for addressing behavioral changes was identified by some nurses as particularly important for identifying and responding to hypoactive behavioral changes. Decision support systems capable of accommodating and even recommending individualized assessment and treatment approaches may be particularly useful as nurses’ described very little documentation of results from any approaches.

Findings from this study highlight an urgent need to improve long-term care nurses’ understanding of evidence-based pain management guidelines in older persons, particularly for persons with dementia and chronic pain. Nurses in this study held numerous misconceptions regarding pain in older persons that presented barriers to adequate pain management. Nurses in this study understood that many residents had co-morbid chronic conditions but did not consistently associate older age and chronicity with increased risk for persistent pain. The underrecognition of pain in long-term residents likely to experience persistent pain by nurses in this study represents an alarming gap between current evidence and practice (American Geriatrics Society Panel on the Pharmacological Management of Persistent Pain in Older Persons, 2009).

The progression of assessment techniques nurses used rarely followed evidence-based recommendations. The Hierarchy of Pain Assessment Techniques outlines these steps: (1) attempt some form of self-report, (2) search for potential causes, (3) observe patient behavior, (4) obtain proxy reports if available and (5) attempt an analgesic trial (Hadjistavropoulos et al., 2007; Herr, Coyne, McCaffery, Manworren, & Merkel, 2011). Some nurses made no attempts to obtain self-report from residents with dementia and most began assessment efforts by initiating interventions to relieve behaviors void of any analgesic trial. Guidelines further recommend regular reassessment and documentation (Herr, et al., 2011) which were rarely described by nurses in this study.

The only pain assessment tools nurses described were the 0–10 Numeric Pain Intensity Scale and Faces Pain Scale (Manias, Gibson, & Finch, 2011). No mention was made by nurses in this study of other validated non-verbal pain tools for advanced dementia such as the Pain Assessment in Advanced Dementia (PAINAD) Scale, Non-Communicative Patient’s Pain Assessment Instrument (NOPPAIN), or the Pain Assessment Checklist for Seniors with Limited Ability to Communicative (PACSLAC) (Herr, et al., 2010). Many of these evidence-based tools and instructions for their use are available for free online (The Center for Nursing Excellence in Long Term-Care ™, 2012) but when asked, no participant was able to name any other pain assessment tool used in their facility. Exploring the extent of long-term care nurses’ knowledge of non-verbal pain tools and reasons for the under application of evidence-based pain assessment practices in NHs using a larger sample can help in identifying areas of need for translational research.

NHs receiving reimbursements from the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) must demonstrate that all residents with pain symptoms or who have the potential for pain (1) have their pain recognized and anticipated, (2) have existing pain and its causes evaluated, and (3) manage or prevent pain consistent with clinical standards of practice and the residents’ preferences (McSpadden, 2010). Faced with the complexity of dementia and dementia-related behaviors, however, nurses in this study did not have a strong enough understanding of pain and behavioral symptom management to meet these goals. Overwhelmingly, nurses expressed strong feelings about the importance of providing comprehensive pain treatment, which strongly suggest that unwillingness to treat on behalf of nurses is not the root cause of this problem. Interventions geared towards improving decision-making and decision-support among nurses need to go beyond providing education and also address the need for additional system supports and facility-level integration of appropriate pain management practices.

Limitations

The findings of this study must be interpreted in light of its limitations. This study included a small sample of licensed nurses who all worked in a geographically similar area. No demographic information was collected and no participant observation took place and as a result we are unable to establish, with certainty, consistency between nurses reported treatment patterns and their actions.

Conclusions and Future Directions

Findings from this qualitative study provide an understanding of treatment decisions regarding pain from nurses at 4 Skilled Nursing Facilities in Wisconsin. This study provides further evidence of low levels of evidence-based pain management practices in NHs and expands our understanding of possible reasons for continued undtertreatment of pain among residents with dementia according to the nurses’ perspective. This study also expands our understanding of the interrelationships among resident, pain and provider factors related to pain treatment decisions. Examining nurses’ pain treatment decision-making practices with a larger sample and expanded care area is suggested.

Supplementary Material

References

- American Geriatrics Society on the Pharmacological Management of Persistent Pain in Older Persons. Pharmacological management of persistent pain in older persons. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2009;57(8):1331–1346. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2009.02376.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Medical Directors Association (AMDA) Pain management in the long-term care setting clinical practice guideline. Columbia, MD: AMDA; 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bachino C, Snow AL, Kunrk ME, Cody M, Wristers K. Principles of pain assessment and treatment in non-communicative demented patients. Clinical Gerontologist. 2008;23(3–4):97–115. [Google Scholar]

- Bowers B, Schatzman L. Dimensional Analysis. In: Morse J, Stern P, Corbin J, Bowers B, Clarke A, Charmaz K, editors. Developing Grounded Theory: The Second Generation. Walnut Creek, California: Left Coast Press; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Caron C, Bowers B. Methods and application of dimensional analysis: A contribution to concept and knowledge development in nursing. In: Rodgers B, Knafl K, editors. Concept development in nursing, foundations, techniques and applications. Philadelphia: W.B. Saunders Co; 2000. pp. 285–319. [Google Scholar]

- Clark ME. Post-deployment pain: a need for rapid detection and intervention. Pain Medicine. 2004;5(4):333–334. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4637.2004.04059.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark L, Jones K, Pennington K. Pain assessment practices with nursing home residents. Western Journal of Nursing Research. 2004;26(7):733–750. doi: 10.1177/0193945904267734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corazzini KN, Anderson RA, Rapp CG, Mueller C, McConnell ES, Lekan D. Delegation in long-term care: scope of practice or job description? OJIN: The Online Journal of Issues in Nursing. 2010;15(2) doi: 10.3912/OJIN.Vol15No02Man04. Manuscript 4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrell BA. Pain Management. Clinics in Geriatric Medicine. 2000;16(4):853–874. doi: 10.1016/s0749-0690(05)70048-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibson SJ, Weiner DK, editors. Pain in Older Persons, Progress in Pain Research and Management. Vol. 35. Seattle, WA: IASP Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Hadjistavropoulos T, Herr K, Turk DC, Fine PG, Dworkin RH, Helme R, Williams J. An interdisciplinary expert consensus statement on assessment of pain in older persons. The Clinical Journal of Pain. 2007;23(1 Suppl):S1–43. doi: 10.1097/AJP.0b013e31802be869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hadjistavropoulos T, Janzen Claude JA, Hadjistavropoulos H, Marchildon GP, Kaasalainen S, Gallagher R, Beattie BL. Stakeholder opinions on a transformational model of pain management in long-term care. Journal of Gerontological Nursing. 2011;37(7):40–51. doi: 10.3928/00989134-20100503-03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herr K, Bjoro K, Decker S. Tools for assessment of pain in nonverbal older adults with dementia: a state-of-the-science review. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management. 2006;31(2):170–192. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2005.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herr K, Bursch H, Black B. State of the art review of tools for assessment of pain in nonverbal older adults. 2008 doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2005.07.001. Retrieved from http://prc.coh.org/PAIN-NOA.htm. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Herr K, Bursch H, Ersek M, Miller L, Swafford K. Use of pain-behavioral assessment tools in the nursing home: expert consensus recommendations for practice. Journal of Gerontological Nursing. 2010;36(3):18–29. doi: 10.3928/00989134-20100108-04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herr K, Coyne P, McCaffery M, Manworren R, Merkel S. Pain assessment in the patient unable to self-report: position statement with clinical practice recommendations. Pain Management Nursing. 2011;12(4):230–250. doi: 10.1016/j.pmn.2011.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herr K, Garand L. Assessment and measurement of pain in older adults. Clnics in Geriatric Medicine. 2001;17(3):457–478. vi. doi: 10.1016/s0749-0690(05)70080-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horgas AL, Elliott AF. Pain assessment and management in persons with dementia. Nursing Clinics of North America. 2004;39(3):593–606. doi: 10.1016/j.cnur.2004.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horgas AL, Tsai PF. Analgesic drug prescription and use in cognitively impaired nursing home residents. Nursing Research. 1998;47(4):235–242. doi: 10.1097/00006199-199807000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaasalainen S, Coker E, Dolovich L, Papaioannou A, Hadjistavropoulos T, Emili A, Ploeg J. Pain management decision making among long-term care physicians and nurses. Western Journal of Nursing Research. 2007;29(5):561–580. doi: 10.1177/0193945906295522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaasalainen S, Middleton J, Knezacek S, Hartley T, Stewart N, Ife C, Robinson L. Pain and cognitive status in the institutionalized elderly: perceptions & interventions. Journal of Gerontological Nursing. 1998;24(8):24–31. doi: 10.3928/0098-9134-19980801-07. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kovach CR, Griffie J, Muchka S, Noonan PE, Weissman DE. Nurses’ perceptions of pain assessment and treatment in the cognitively impaired elderly. It’s not a guessing game. Clinical Nurse Specialist. 2000;14(5):215–220. doi: 10.1097/00002800-200009000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kovach C, Logan B, Noonan P, Schlidt A, Smerz J, Simpson M, Wells T. Effects of the serial trial intervention on discomfort and behavior of nursing home residents with dementia. American Journal of Alzheimer's Disease and Other Dementias. 2006;21(3):147–155. doi: 10.1177/1533317506288949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kovach CR, Logan BR, Simpson MR, Reynolds S. Factors associated with tiem to identify physical problems of nursing home residents with dementia. American Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease and Other Dementias. 2010;25(4):317–23. doi: 10.1177/1533317510363471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kruger AB, Stone AA. Assessment of pain: a community-based diary survey in the USA. Lancet. 2008;3(371):1519–25. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60656-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manias E, Gibson SJ, Finch S. Testing an educational nursing intervention for pain assessment and management in older people. Pain Medicine. 2011;12:1199–1215. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4637.2011.01181.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McAuliffe L, Nay R, O’Donnell M, Fetherstonhaugh D. Pain assessment in older people with dementia: literature review. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 2008;65(1):2–10. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2008.04861.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCaffery M, Ferrell B, Pasero C. No justified use of placebos for pain. Journal of Nursing Scholarship. 2000;32(2):114–115. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McSpadden C. Criteria for compliance: Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services pain management at F-Tag 309. The Consultant Pharmacist. 2010;25(Suppl A):20–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morse JM. Determining sample size. Qualitative Health Research. 2000;10(1):3–5. doi: 10.1177/1049732315602867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parke B. Gerontological nurses’ ways of knowing. Realizing the presence of pain in cognitively impaired older adults. Journal of Gerontological Nursing. 1998;24(6):21–28. doi: 10.3928/0098-9134-19980601-08. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rantz MJ, Hicks L, Grando V, Petroski GF, Madsen RW, Mehr DR, Maas M. Nursing home quality, cost, staffing, and staff mix. The Gerontologist. 2004;44(1):24–38. doi: 10.1093/geront/44.1.24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds KS, Hanson LC, DeVellis RF, Henderson M, Steinhauser KE. Disparities in pain management between cognitively intact and cognitively impaired nursing home residents. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management. 2008;35(4):388–396. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2008.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salzman C, Jeste D, Meyer R, Cohen-Mansfield J, Cummings J, Grossberg G, Zubenko G. Elderly patients with dementia-related symptoms of severe agitation and aggression: consensus statement on treatment options, clinical trials methodology, and policy. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 2008;68:889–898. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v69n0602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schatzman L, editor. Dimensional Analysis: Notes on an alternative approach to grounding of theory in qualitative research. New York: Aldine De Gruyter; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Strauss A. Qualitative Analysis for Social Scientists. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Takai Y, Yamamoto-Mitani N, Okamoto Y, Koyama K, Honda A. Literature review of pain prevalence among older residents of nursing homes. Pain Management Nursing. 2010;11(4):209–223. doi: 10.1016/j.pmn.2010.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The Center for Nursing Excellence in Long Term-Care ™. 2012 Oct 4; Retrieved from http://www.centerfornursingexcellence.org/

- Weiner DK, Peterson BL, Logue P, Keefe FJ. Predictors of pain self-report in nursing home residents. Aging. 1998;10(5):411–420. doi: 10.1007/BF03339888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams CS, Zimmerman S, Sloane PD, Reed PS. Characteristics associated with pain in long-term care residents with dementia. Gerontologist. 2005;45(1):68–73. doi: 10.1093/geront/45.suppl_1.68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu N, Miller SC, Lapane K, Roy J, Mor V. Impact of cognitive function on assessments of nursing home residents’ pain. Medical Care. 2005;43(9):934–939. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000173595.66356.12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.