Abstract

While smoking is a major cause of mortality and morbidity, and maternal smoking is a risk factor for smoking among their offspring, the mechanisms involved in the intergenerational transmission of smoking are not well understood. This study examines the pathways from maternal and adolescent child factors, and the parent-child relationship, to smoking among the adult offspring, approximately 25 years' later. Data for the present analysis were based on time waves 2 (T2; 1983) and 7 (T7; 2007–2009) of an on-going study of a community sample of mothers and their children. Offspring and mother ages were 14.1 and 40.0 years, respectively, at T2, and 36.6 and 65.0 years, respectively, at T7. At T2, trained interviewers administered individual structured interviews. Psychosocial questionnaires were self-administered at T7. Structural equation modeling (SEM) was used to analyze the interrelationships among maternal and offspring attributes (T2 and T7). SEM results indicated a satisfactory model fit (RMSEA=0.052; CFI=0.91; SRMR=0.057), and confirmed hypothesized pathways. One pathway linked maternal maladaptive attributes (T2) to the mother-adolescent child attachment relationship (T2), which was associated with the offspring's maladaptive attributes over time (T2 to T7), which then predicted the adult offspring's smoking (T7). Other pathways highlighted the stability of maternal smoking, the continuity of maladaptive attributes, and less offspring educational attainment as predictors of offspring smoking at T7. Findings suggest the importance of early interventions to treat maternal smoking, maternal and offspring maladaptive attributes, and the mother-child relationship in order to reduce risk factors for the intergenerational transmission of smoking behavior. Interventions which enhance educational success should also prove effective in reducing smoking.

Keywords: Adult smoking, Intergenerational smoking, Mother-child relationship, Maladaptive attributes, Educational attainment and smoking, Midlife women

1. INTRODUCTION

Cigarette smoking accounted for over 6 million deaths globally in 2010, and is the second leading cause of disability worldwide (Lim et al., 2012). In the United States, approximately one in five deaths is attributable to cigarette smoking (CDC, 2008). Although maternal smoking is a risk factor for smoking among their offspring, the mechanisms involved in the intergenerational transmission of smoking are not well understood. Numerous studies have identified associations between maternal attributes (e.g., smoking), adolescent psychological problems, aspects of the mother-child relationship, and adolescent smoking (Chassin, Presson, Todd, Rose, & Sherman, 1998; Ennett et al., 2010; Lawlor et al., 2005; SAMHSA, 2010a). There is a dearth of research, however, on the longitudinal impact of these earlier influences, or the effects of contemporaneous factors, on smoking among adults. A better understanding of the impact of these maternal factors on smoking among their offspring may contribute to the development of prevention and intervention programs which reduce the intergenerational transmission of risk factors for smoking. The present study, therefore, uses data spanning approximately 25 years to examine the pathways from earlier maternal attributes and the mother-adolescent relationship to the offspring's smoking in adulthood.

1.1 Maternal and Offspring Maladaptive Attributes and Smoking

Prior research has found that maternal smoking during pregnancy is a risk factor for numerous adverse outcomes among their offspring, such as externalizing behaviors and disorders (Brook, Zhang, Rosenberg, & Brook, 2006; Fitzpatrick, Barnett, & Pagani, in press), diminished academic achievement (Agrawal et al., 2010), and substance use, including smoking (Agrawal et al., 2010; D'Onofrio et al., 2012). The association of maternal gestational smoking and problems among their offspring may be both causal (e.g., specific to the in utero effects of nicotine on neurodevelopment) as well as derived from environmental factors shared by mother and child (e.g., Agrawal et al., 2010; D'Onofrio et al., 2008; Lieb, Schreier, Pfister, & Wittchen, 2003; O'Callaghan et al., 2006).

A substantial literature has also found that maternal smoking during the offspring's childhood or adolescence is related to the offspring's smoking during adolescence or young adulthood (e.g., Gilman et al., 2009; Kelly et al., 2011; Leonardi-Bee, Jere, & Britton, 2011; Osler, Clausen, Ibsen, & Jensen, 1995; SAMSHA, 2010a). In one of few investigations to examine the link between earlier maternal smoking and the offspring's smoking in adulthood, Vink, Willemsen, & Boomsma (2003) showed that maternal smoking during the offspring's adolescence predicted offspring smoking during adolescence, young adulthood, and adulthood. To our knowledge, there are no studies on the relationship of concurrent smoking among older women and their adult offspring. Some factors which have been shown to operate between maternal smoking and smoking among the offspring include role modeling of maternal smoking behavior (Weden & Miles, 2012), fewer anti-smoking rules (Sargent & Dalton, 2001), and common genetic vulnerabilities shared by mother and child (Weden & Miles, 2012).

Although a review of the genetics of smoking is beyond the scope of this paper, both genes and environment have been shown to contribute to smoking behavior, with genetic influences exerting greater effects on later stages of smoking and nicotine dependence (Shenassa et al., 2003; White, Hopper, Wearing, & Hill, 2003). Human and animal studies have identified variants of cholinergic nicotinic receptor subunit gene clusters (e.g., CHRNA5-CHRNA3-CHRNB4) and nicotine-metabolizing enzymes (e.g., CYP2A6 and CYP2B6) which have been implicated in smoking (Saccone et al., 2009). These variants have also been linked to heavy smoking and nicotine dependence (Berrettini et al., 2008; Saccone et al., 2009; Thorgeirsson et al., 2008), the age of smoking cessation (Chen et al., 2012), severity of withdrawal symptoms (Baker et al., 2009), and smoking-related morbidity, i.e., lung cancer and peripheral arterial disease (Saccone et al., 2009; Thorgeirsson et al., 2008).

In addition, mothers who smoke tend to have elevated rates of psychological symptoms and psychiatric disorders (Degenhardt & Hall, 2001), which have been found to be linked with smoking among their offspring (SAMHSA, 2010a). However, as noted, the precise mechanisms involved in the intergenerational transmission of smoking behavior are not entirely understood.

Smoking and psychological problems (e.g., depression) are highly related among both adolescent and adult smokers (Hu, Davies, & Kandel, 2006; Klungsøyr, Nygård, Sørensen, & Sandanger, 2006), although it is unclear whether this relationship is causal, reciprocal, or stems from a shared underlying etiology (e.g., Boden, Fergusson & Horwood, 2010; Orlando, Ellickson & Jinnett, 2001). Furthermore, the results of some studies suggest that psychological maladjustment during adolescence may predict smoking and nicotine dependence during later developmental stages (McKenzie, Olsson, Jorm, Romaniuk, & Patton, 2010).

There is considerable evidence (especially in the literature on adolescence) of the intergenerational transmission of psychological difficulties, such as depression, anxiety, and low self-esteem (Campbell, Morgan-Lopez, Cox, & McLoyd, 2009; Papp, Cummings, & Goeke-Morey, 2005). The concordance of psychological problems among mothers and their offspring may stem from maternal role modeling of maladaptive affect and behaviors (Brook, Brook, Gordon, Whiteman, & Cohen, 1990; Campbell et al., 2009), shared contextual influences (such as exposure to stressful neighborhoods; Patterson, Eberly, Ding, & Hargreaves, 2004), a genetic vulnerability (Kendler, Myers, Maes, & Keyes, 2011), and/or the adverse effects of maladaptive maternal attributes on the mutual attachment relationship with the child (e.g., Hammen, Shih, & Brennan, 2004; National Research Council [NRC] and Institute of Medicine [IOM], 2009).

1.2. Family Interactional Theory and the Mother-Child Mutual Attachment Relationship

The theoretical framework for the present study is based on Family Interactional Theory (FIT; Brook et al., 1990). FIT posits that there is a developmental progression from maternal to child maladaptive psychological attributes, which may be mediated by the effect of maternal attributes on the mother-child relationship (Papp et al., 2005). According to FIT, maternal substance use and/or psychopathology may undermine the development of a close, non-conflictual mutual attachment relationship with the child. Children with a weaker and more distant maternal bond, in turn, are less likely to identify with and model parental pro-social behaviors and, therefore, may be at risk for maladaptive personal attributes, behaviors, and functioning, e.g., Brook et al., 1990; Papp et al., 2005. Furthermore, the FIT paradigm may be extended to later developmental stages. That is, the mother-adolescent child attachment relationship may have enduring effects on the offspring. Flouri (2005), for instance, reported that maternal involvement with her adolescent child predicted less distress among the offspring in adulthood. Bell and Bell (2005) also demonstrated a pathway from parental resources (e.g., ego development) to positive family dynamics (e.g., connectedness) during the offspring's adolescence to the offspring's well-being in the 30s and 40s.

Here, we extend FIT to an adult sample to test the longitudinal impact of a weak and conflictual mother-adolescent attachment relationship on the adult offspring's maladaptive attributes, educational attainment, and smoking in the late 30s.

1.3. Continuity of Smoking, Stability of Maladaptive Attributes, and the Adult Offspring's Educational Attainment

With a few important exceptions, there is limited research on intra-individual continuity of smoking across adulthood and into late midlife (Yong, Borland, Thrasher, & Thompson, 2012). However, Frosch, Dierker, Rose, & Waldinger (2009) identified several developmental patterns of smoking throughout adulthood, which demonstrated both continuity and discontinuity (i.e., smoking cessation at different stages) in smoking behavior.

With respect to maladaptive attributes, several investigations (e.g., Colman, Wadsworth, Croudace, & Jones, 2007; Roza, Hofstra, van der Ende, & Verhulst, 2003) have reported considerable stability of psychopathology over time, although most of this research has focused on the period from adolescence to young adulthood. For example, Dekker et al. (2007) demonstrated that trajectories of depressive symptoms (beginning in childhood or adolescence) predicted more symptoms of depression and other mental health problems in young adulthood. Clark, Rodgers, Caldwell, Power, & Stansfeld (2007) found that internalizing and externalizing disorders in childhood, pre-adolescence, and adolescence were related to psychological distress in the 20s, 30s, and 40s, as well as depressive and anxiety disorders at age 45.

In the United States (and other industrialized nations), there is a strong inverse relationship between each component of socioeconomic status (i.e., educational level, occupational status, and income), and cigarette smoking (IOM, 2007; Sorensen, Barbeau, Hunt, & Emmons, 2004). Chassin, Curran, Presson, Sherman, & Wirth (2009), for example, examined smoking trajectories from ages 10–42 years, and found that the most severe smoking group (early-onset persistent smokers) was the least educated, compared to all other groups identified.

1.4. Hypotheses

We hypothesized the following three sets of relationships between maternal and offspring factors and smoking among the adult offspring (in the late 30s). First, maternal maladaptive personal attributes are associated with the mother-adolescent child relationship, which is linked with the offspring's maladaptive personal attributes. Offspring maladaptive attributes, in turn, are related to their smoking in the late 30s. Second, maternal maladaptive attributes are related to the continuity of maternal smoking (from the early 40s to the mid-60s), which increases the likelihood of smoking among the adult offspring. Third, maternal and offspring maladaptive attributes (in the mid-60s and late 30s, respectively) are related. Adult offspring maladaptive attributes are linked with the offspring's lower educational attainment which, in turn, predicts offspring smoking in adulthood.

2. METHODS

2.1. Participants and Procedure

Data on the participants came from a longitudinal psychosocial study of mothers and their children, begun in 1975. Participants were from a community-based random sample of families, residing in one of two counties, Albany or Saratoga, in upstate New York. The sampled families were generally representative of families in the northeast U.S. at that time. For example, there was a close match between the participants and the 1980 U.S. Census with regard to family income, maternal education, and family structure.

The present analysis (N=404) is based on data from time wave 2 (T2; 1983) and wave 7 (T7; 2007–2009) of the longitudinal study. Participants consisted of N=404 mother-offspring pairs, who were interviewed at both T2 and T7. The mean age of mother participants at T2 was 40.0 years (SD=6.2), and the offspring participants'mean age at this time wave was 14.1 years (SD=2.8). At T7, the mean age of the mother participants was 65 years (SD=6.2), and the offspring participants were mean age 36.6 years (SD=2.8).

To assess attrition, we compared the mothers (N=318) who were interviewed in 1983 (T2) but not in 2009 (T7) with the mothers who were included in the present study (N=404). Those mothers who were included in the current analyses had a significantly greater educational level (t=5.65, p-value<0.001) than those who were not included. We also compared the offspring participants (N=404) who were included in the analysis with the offspring participants (N=352) who were interviewed in 1983 but not studied here. There were fewer male participants (χ2(1)=5.96, p-value<0.015), and less reported impulsivity (t=2.0, p-value=0.04) among those studied at T7 (2009) compared with participants not included at T7. There were no statistically significant differences between offspring participants included in the analyses and those who were not included with respect to age (t=−0.51, p=0.61), smoking at T2 (t=−1.39, p=0.56), ego control at T2 (t=1.12, p=0.26), or depressed mood at T2 (t=0.59, p=0.56).

Extensively trained and supervised lay interviewers administered individual structured interviews at T2 (mothers and offspring were interviewed separately and in private). Questionnaires were self-administered by mother and offspring participants at T7. Written informed consent and HIPAA authorization (as of April 2003) were obtained from all participants. The procedures used in this research study at T7 were approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of the New York University School of Medicine. Earlier waves of data collection were approved by the Mount Sinai School of Medicine IRB. Additional information regarding the study methodology is available in prior publications (e.g., Cohen & Cohen, 1996).

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. The Dependent Variable

The dependent variable, adult offspring cigarette smoking at T7, was the response to a question which asked the adult offspring, “How many cigarettes did you smoke in the past two months?” (adapted from the Monitoring the Future study; Johnston, O'Malley, Bachman, & Schulenberg, 2006). The response range was a scale coded as (0) not at all, (1) some, but less than daily, (2) 1–5 cigarettes a day, (3) about half a pack a day, (4) about a pack a day, (5) about 1.5 packs a day, and (6) more than 1.5 packs a day. This measure of cigarette smoking has been found to predict young adult psychiatric disorders (Brook, Brook, Zhang, Cohen & Whiteman, 2002) and health problems (Brook, Brook, Zhang, & Cohen, 2004).

2.2.2. The Independent Latent and Manifest Variables

The independent latent variables were maternal maladaptive personal attributes at T2 and T7, offspring maladaptive personal attributes at T2 and T7, and the mother-adolescent child mutual attachment relationship at T2. The independent manifest variables consisted of maternal cigarette smoking at T2 and T7, and the offspring's educational attainment at T7. For each of the scales for the independent variables, the subject (mother or offspring), time wave, response range, a sample item, and the Cronbach's alpha are listed in Table 1. (See Table 1.) All measures were self-report except for Child's Resistance to Maternal Control, one of the scales in the Mother-Adolescent Mutual Attachment Relationship latent construct, which was the mother's report of her adolescent child.

Table 1.

Independent Variables: Scales, Authors, Response Ranges, Time Wave, Number of Items, Cronbach's Alpha, and Sample Item

| Variable | Mother (T2) | Mother (T7) | Offspring (T2) | Offspring (T7) | Sample Item |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Maternal and Offspring Maladaptive | α=0.83 | α=0.91 | α=0.77 | α=0.79 | |

| Personal Attributes | |||||

| Depressed Mooda (Derogatis, Lipman, Rickels, Uhlenhuth, & Covi, 1974) | X 8 items | X 6 items | X 4 items | X 5 items | “Within the past few years, how much were you bothered by feeling hopeless about the future?” |

| Ego Controlb (Brook et al., 1990) | X 6 items | X 7 items | X 7 items | X 7 items | “I rely on careful reasoning in making up my mind.” |

| Impulsivityb (Gough, 1957) | X 6 items | X 6 items | “I often act on the spur of the moment without stopping to think.” | ||

| Self-esteemb (Brook et al., 1990) | X 5 items | X 3 items | “I see myself as a very respected and successful person.” | ||

| Maternal Smokingc (Adapted from Johnston et al., 2006) | X Single item | X Single item | “How many cigarettes did you smoke in the past two months?” (T2) “…in the past year?” (T7) |

||

| Mother-Adolescent Child Weak Mutual Attachment Relationship: | α=0.89 (Maternal and offspring reports - T2) | ||||

| Child's Resistance to Maternal Controld (Schaefer & Finkelstein, 1975) | X 5 items | “How often does your child do the opposite of what you tell him/her?” | |||

| Mother-Adolescent Child Weak Mutual Attachment Relationship (continued): | |||||

| Maternal Identification | |||||

| Maternal Admiratione (Brook et al., 1990) | X 5 items | “How much do you admire your mother in her role as mother?” | |||

| Maternal Emulatione (Brook et al., 1990) | X 5 items | “How much do you want to be like your other in your role as a parent?” | |||

| Maternal Similaritye (Brook et al., 1990) | X 4 items | “How similar do you think you actually are to your mother in terms of personality? | |||

| 14 items total | |||||

| Maternal Affectionf (Schaefer, 1965) | X 4 items | “She frequently shows her love for me.” | |||

| Offspring Educational Attainmentg (Brook et al., 1990) | X Single item | “What was the last year of school you completed?” | |||

Notes:

X = Scale included in analysis.

Response ranges:

(1) not at all - (5) extremely;

(1) false - (4) true;

(0) none, (1) used to smoke but stopped, (2) less than ½ a pack a day, (3) ½ a pack to 1 pack a day, (4) more than 1 pack a day. Asked at T7 only: (5) about 1.5 packs a day, (6) more than 1.5 packs a day;

(1) not at all like my child - (4) very much like my child;

(1) not at all - (5) in every way;

(1) not at all like my mother - (2) very much like my mother;

(1) ≤ 8th grade to 11) Graduate student.

2.2.3. Control Variables

In the analyses, we statistically controlled for the following variables: the offspring's gender, age in their late 30s, and frequency of cigarette smoking in adolescence (T2) [(0) not at all - (5) about 1.5 packs a day or more], and the mother's age and educational level in the mid-60s [(1) less than high school - (6) doctoral degree or equivalent].

2.3. Data Analysis

A latent variable structural equation model was used to examine the empirical validity of the hypothesized pathways. To account for the influences of the offspring's gender, age, and smoking in adolescence (T2), and the mother's age and educational level (T7) on these models, we used a partial correlation matrix as the input matrices. This was created by statistically partialing out (removing the effect of) the baseline measure of the variables cited above (section 2.2.3.) on each of the original manifest variables in the present analyses. Our proposed model was estimated using Mplus (Muthén & Muthén, 2010). The Mplus (Muthén & Muthén, 2010) default option was used (i.e., full information maximum likelihood approach; FIML) to treat missing data. The advantage of FIML is that the results are less likely to be biased even if the data are not missing completely at random (Muthén, Kaplan, & Hollis, 1987). We chose three fit indices to assess the fit of the models: (1) the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA), (2) Bentler's comparative fit index (CFI) (Bentler, 1990), and (3) the standardized root mean square residual (SRMR). Values between .90 and 1.0 on Bentler's CFI indicate that the model provides a good fit to the data (Kelloway, 1998). Values for the RMSEA and the SRMR should be below .10 to indicate a good fit. We also calculated the standardized total effects, which equal the sum of the direct and the indirect effects of each latent or manifest variable estimated in the analysis on the dependent variable.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Descriptive Statistics

Table 2 presents the response ranges, means, and standard deviations of the dependent, independent, and control variables used in the SEM analyses. (See Table 2.) Almost one quarter (22.1%) of the offspring participants reported smoking on a daily basis at T7. Among the mother participants, 26.2% reported daily smoking at T2, and 12.2% smoked daily at T7. The respective percentages of mothers and adult offspring who smoked at T7 were comparable to national averages in the U.S. population as reported by The National Survey on Drug Use and Health for 2009, the year in which our data were collected (SAMSHA, 2010b).

Table 2.

Descriptive Statistics (N=404).

| Variables | Response Range | Mean | Standard Deviation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dependent and Independent Variables at T7 | |||

| Offspring Cigarette Smoking (Late 30s) | (0) not at all - (6) more than 1.5 packs a day | 0.86 | 1.62 |

| Offspring Depressed Mood (Late 30s) | (1) not at all - (5) extremely | 1.85 | 0.66 |

| Offspring Ego Control (Late 30s) | (1) false - (4) true | 3.09 | 0.46 |

| Offspring Impulsivity (Late 30s) | (1) false - (4) true | 1.96 | 0.45 |

| Offspring Educational Attainment (Late 30s) | (1) 8th grade or below - (11) graduate student | 8.29 | 2.55 |

| Maternal Cigarette Smoking (Mid-60s) | (0) not at all - (6) more than 1.5 packs a day | 0.47 | 1.29 |

| Maternal Depressed Mood (Mid-60s) | (1) not at all - (5) extremely | 1.89 | 0.74 |

| Maternal Ego Control (Mid-60s) | (1) false - (4) true | 3.38 | 0.44 |

| Maternal Self-Esteem (Mid-60s) | (1) quite dissatisfied - (4) quite satisfied | 3.54 | 0.59 |

| Independent Variables at T2 | |||

| Offspring Depressed Mood (Adolescence) | (1) not at all - (5) extremely | 2.10 | 0.68 |

| Offspring Ego Control (Adolescence) | (1) false - (4) true | 2.80 | 0.49 |

| Offspring Impulsivity (Adolescence) | (1) false - (4) true | 2.22 | 0.51 |

| Resistance to Maternal Control (Adolescence) | (1) not at all like my child - (4) very much like my child | 1.45 | 0.54 |

| Maternal Identification (Adolescence) | (1) not at all - (5) in every way | 3.50 | 0.87 |

| Maternal Affection (Adolescence) | (1) not at all like my mother - (4) very much like my mother | 3.36 | 0.60 |

| Maternal Cigarette Smoking (Early 40s) | (0) none - (4) more than one pack a day | 1.14 | 1.51 |

| Maternal Depressed Mood (Early 40s) | (1) not at all - (5) extremely | 1.69 | 0.52 |

| Maternal Ego Control (Early 40s) | (1) false - (4) true | 3.02 | 0.44 |

| Maternal Self-Esteem (Early 40s) | (1) false - (4) true | 3.27 | 0.48 |

| Control Variables | |||

| Offspring Gender | (0) female - (1) male | 0.47 | 0.50 |

| Offspring Age (Late 30s) | Years | 36.44 | 2.85 |

| Offspring Cigarette Smoking (Adolescence) | (0) not at all - (5) about 1.5 packs a day or more | 0.55 | 1.06 |

| Maternal Age (Mid-60s) | Years | 65.29 | 6.17 |

| Maternal Educational Attainment (Mid-60s) | (1) less than a high school - (6) doctoral degree or equivalent | 2.61 | 1.08 |

3.2. Path Analyses

Supplementary Table S1 in Appendix A presents the direction and standardized factor loadings for each manifest variable (within the latent construct). Each factor loading was significant at p<.001 (see Appendix A, Supplementary Table S1).

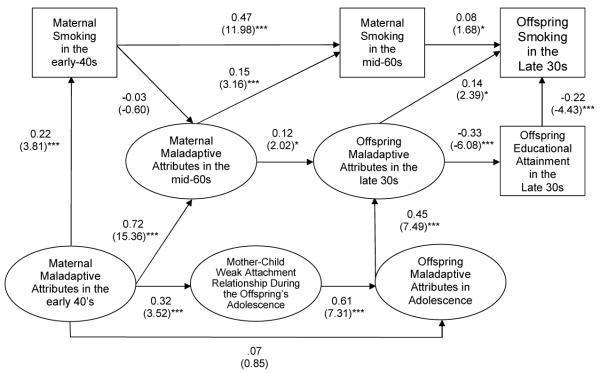

The RMSEA was 0.052, Bentler's CFI was 0.91, and the SRMR was 0.057, and reflect a satisfactory model fit. The obtained path diagram along with the standardized regression coefficients and z-statistics are depicted in Figure 1. For each of the latent and manifest constructs, we examined the total variance explained by the latent/manifest variables which were hypothesized to be predictors of that construct. The variance for the dependent variable, offspring smoking in the late 30s, was R2=.10.

Figure 1.

Obtained model: Standardized Pathways (z-statistic) to Cigarette Smoking Among Adult Offspring (N=404).

Notes:

a- * p<.05; ** p<.01; *** p<.001 (one-tailed test);

b- RMSEA=0.052; CFI=0.91; SRMR=0.057;

c- The participants' age, gender, smoking in adolescence, and the mother's age and educational level were statistically controlled.

d- Manifest variables comprising latent variables: Maternal Maladaptive Attributes in the early 40's and in the mid-60's=Depressed Mood, Ego Control, and Self-Esteem; Mother-Child Weak Attachment Relationship During the Offspring's Adolescence=Child's Resistance to Maternal Control, Maternal Identification (Admiration, Emulation, Similarity), and Maternal Affection; Offspring Maladaptive Attributes in Adolescence and in the late 30s=Depressed Mood, Ego Control, and Impulsivity.

As shown in Figure 1, the results supported our major hypotheses. First, maternal maladaptive personal attributes in the early 40s were linked with a weak and conflictual mother-adolescent child relationship (β=0.32; z=3.52; p<.001), which was associated with the offspring's maladaptive attributes in adolescence (β=0.61; z=7.31; p<.001). Offspring maladaptive attributes were generally stable into the late 30s (β=0.45; z=7.49; p<.001), and related to offspring smoking in the late 30s (β=0.14; z=2.39; p<.05). Second, maternal maladaptive attributes (early 40s) were related to maternal smoking (also in the early 40s) (β=0.22; z=3.81; p<.001) which, in turn, was associated with maternal smoking in the mid-60s (β=0.47; z=11.98; p<.001). There was a direct pathway from maternal smoking (mid-60s) to the offspring's smoking in the late 30s (β=0.08; z=1.68; p<.05). Third, there was continuity of maternal maladaptive personal attributes from the early 40s to the mid-60s (β=0.72; z=15.36; p<.001). Maternal maladaptive attributes in the mid-60s were linked with the offspring's maladaptive attributes in the late 30s (β=0.12; z=2.02; p<.05), which were inversely associated with the offspring's educational attainment (late 30s) (β=−0.33; z=−6.08; p<.001). The offspring's educational attainment was directly and inversely related to their smoking in the late 30s (β=−0.22; z=−4.43; p<.001). (See Figure 1.)

3.2.1. Alternate Pathways

We also tested an alternative model, which consisted of reciprocal pathways between adolescent maladaptive attributes and maternal maladaptive attributes. The pathway from adolescent maladaptive attributes to maternal maladaptive attributes was non-significant (z=0.95, p>0.05).

3.3. Standardized Total Effects

Table 3 presents the results of the total effect analyses. With the exception of maternal smoking in the early 40's, each of the latent/manifest constructs had significant total effects (p<0.05). Among the constructs, offspring maladaptive attributes (late 30s) (β=0.21; z=3.81; p<.001) and offspring educational attainment (also late 30s) (β=−0.22; z=−4.43; p<.001) had the greatest total effects on adult offspring smoking in the late 30s. (See Table 3.)

Table 3.

Standardized Total Effects (z-statistic) of Independent Variables (N=404).

| Independent Constructs | Offspring Cigarette Smoking at T7 (Late 30s) |

|---|---|

|

| |

| Standardized Total Effects (z-statistic) | |

| Offspring Maladaptive Personal Attributes (Late 30s) | 0.21 (3.81)*** |

| Offspring Educational Level (Late 30s) | −0.22 (−4.43)*** |

| Maternal Maladaptive Personal Attributes (Mid-60s) | 0.04 (2.32)* |

| Maternal Cigarette Smoking (Mid-60s) | 0.08 (1.68)* |

| Offspring Maladaptive Personal Attributes in Adolescence | 0.10 (3.33)*** |

| Maternal Cigarette Smoking (Early 40s) | 0.04 (1.62) |

| Mother-Adolescent Child Weak Attachment Relationship | 0.06 (2.98)** |

| Maternal Maladaptive Personal Attributes (Early 40s) | 0.06 (3.28)*** |

Notes:

p<.05;

p<.01;

p<.001 (one-tailed test);

The offspring's age, gender, smoking in adolescence, and the mother's age and educational level were statistically controlled.

4. DISCUSSION

Our study is innovative in three important ways. First, we examined the intergenerational transmission of smoking behavior over a period of approximately 25 years. Second, aspects of this study are consistent with the theoretical framework of Family Interactional Theory (FIT; Brook et al., 1990), as discussed in section 4.1 below. Third, our research highlights three types of mechanisms which increase the extent of smoking among the adult offspring: 1) an impaired mother-child mutual attachment relationship; 2) social role modeling of maladaptive behaviors; and 3) low educational attainment.

4.1. Pathways to Smoking in Adulthood

Overall, our results suggest that there are multiple developmental pathways through which earlier factors during the offspring's adolescence may play a role in the intergenerational transmission of smoking in adulthood, even with statistical control on the offspring's smoking during adolescence. The first hypothesized pathway is in accord with FIT (Brook et al., 1990), which postulates that earlier maternal personality attributes are associated with the mother-child relationship which, in turn, predicts later offspring maladaptive attributes and smoking in the late 30s. This finding supports the extension of FIT to an adult population, and implies a “continuation effect” whereby the parent-adolescent child relationship continues to impact later stages of development when the offspring is more independent of parents. As suggested by the extension of FIT, earlier poor maternal attachment and more offspring maladaptive attributes may undermine the offspring's ability to form close, supportive relationships in adulthood. Individuals who lack such social support, in turn, are more likely to have diminished well-being and to smoke (Sun, Buys, Stewart, & Shum, 2011). Furthermore, individuals with greater maladaptive personal attributes may perceive their lives as more stressful (Ng & Jeffery, 2003), but may not have developed the skills to cope with these difficulties (Sun et al., 2011). Smoking, therefore, may be a means by which the adult offspring attempts to manage emotional dysregulation, as posited by the self-medication hypothesis (Khantzian & Albanese, 2008).

With regard to the second hypothesized pathway to the offspring's smoking in adulthood, the findings provide support for social role modeling, as suggested by the link between maternal smoking and adult offspring smoking. This association is consistent with aspects of Social Learning Theory (Bandura, 1977), according to which parental behaviors may be transmitted to the child via role modeling (Brook et al., 1990; IOM, 2007). The neurobiological effects on the offspring of earlier exposure to maternal smoking (Bandiera, 2011), and/or a genetic predisposition towards smoking, shared by mother and child (Shenassa et al., 2003), may also contribute to the association between maternal and adult offspring smoking.

The third hypothesized pathway involves the intergenerational transmission of maternal maladaptive attributes to the offspring, and the relationship of adult offspring maladaptive attributes to both educational attainment and smoking. Prior research (e.g., Slominski, Sameroff, Rosenblum, & Kasser, 2011; Suldo, Thalji, & Ferron, 2011) has demonstrated that psychological symptoms and disorders are associated with lower educational attainment. Individuals with more maladaptive attributes may experience impaired cognitive functioning, such as problems with concentration, and they may lack the task persistence needed to pursue their studies (e.g., less impulse control; Andersson & Bergman 2011; Goodman, Joyce, & Smith, 2011). Furthermore, our finding of an association between low educational attainment and smoking in adulthood is consistent with an extensive body of research (e.g., CDC, 2011; Fagan, Shavers, Lawrence, Gibson, & O'Connell, 2007; Johnson et al., 2011). Bachman et al. (2008), for instance, found that educational attainment at age 18 predicted smoking up until age 40 years.

4.2. Strengths and Limitations

To our knowledge, the present study is the first to demonstrate the theoretically hypothesized associations between the parent-adolescent child mutual attachment relationship and the adult offspring's maladaptive personal attributes, educational attainment, and smoking, across a span of approximately 25 years. Additional contributions of this investigation are the findings regarding the stability of maternal smoking, as well as the mother's and offspring's maladaptive attributes, and their respective associations with the adult offspring's smoking. We also add to the literature on the impact of the mother's psychological attributes and smoking behavior on their offspring during adulthood. However, there are some limitations to the findings. First, our data are based on a primarily White sample, and the results, therefore, may not be generalizable to other racial or ethnic groups. Second, the greater impulsivity among participants lost to attrition (as noted in section 2.1) may have affected the prevalence of smoking among the adult offspring. Because of the established association between impulsivity and smoking (Chase & Hogworth, 2011; Ryan, Mackillop, & Carpenter, 2013), our findings may have been even stronger if we had been able to include data from the non-participants at T7. Third, as previously noted, there may be some unmeasured selection biases, given the rate of attrition.

4.3. Conclusions

In sum, the present study highlights the enduring effects of the parent-adolescent child attachment relationship on the adult offspring's psychological and behavioral functioning, including smoking in the late 30s. This finding is in accordance with a developmental perspective, which posits that experiences with parents during adolescence continue to be salient when the individual reaches adulthood. Our results also demonstrated the significance of maternal maladaptive personal attributes as a precursor of an impaired parent-child attachment relationship, and the important impact of education on smoking during adulthood. Programs that support academic progress may help individuals to achieve higher levels of education, which are protective against smoking and, therefore, potentially bestow both public health and economic benefits. Clinical implications highlight the importance of early intervention to reduce maternal smoking and maternal psychopathology. Family therapy designed to strengthen the mother-adolescent child relationship may also reduce the risk factors for the intergenerational transmission of smoking.

Supplementary Material

References

- Agrawal A, Scherrer JF, Grant JD, Sartor CE, Pergadia ML, Duncan AE, Xian H. The effects of maternal smoking during pregnancy on offspring outcomes. Preventive Medicine. 2010;50:13–18. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2009.12.009. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ypmed.2009.12.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andersson H, Bergman LR. The role of task persistence in young adolescence for successful educational and occupational attainment in middle adulthood. Developmental Psychology. 2011;47:950–960. doi: 10.1037/a0023786. doi:10.1037/a0023786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bachman J, O'Malley PM, Schulenberg JE, Johnston L, Freedman-Doan P, Messersmith EE. The education-drug use connection: How successes and failures in school relate to adolescent smoking, drinking, drug use, and delinquency. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates/Taylor & Francis; New York: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Baker TB, Weiss RB, Bolt D, von Niederhausern A, Fiore MC, Dunn DM, Cannon DS. Human neuronal acetylcholine receptor A5-A3-B4 haplotypes are associated with multiple nicotine dependence phenotypes. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2009;11:785–796. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntp064. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/ntr/ntp064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bandiera FC. What are candidate biobehavioral mechanisms underlying the association between secondhand smoke exposure and mental health? Medical Hypotheses. 2011;77:1009–1010. doi: 10.1016/j.mehy.2011.08.036. doi:10.1016/j.mehy.2011.08.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bandura A. Social learning theory. Prentice-Hall; Englewood, NJ: 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Bell LG, Bell DC. Family dynamics in adolescence affect midlife well-being. Journal of Family Psychology. 2005;19:198–207. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.19.2.198. doi:10.1037/0893-3200.19.2.198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bentler PM. Comparative fit indexes in structural models. Psychological Bulletin. 1990;107:238–246. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.107.2.238. doi:10.1037//0033-2909.107.2.238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berrettini W, Yuan X, Tozzi F, Song K, Francks C, Chilcoat H, Mooser V. alpha-5/alpha-3 nicotinic receptor subunit alleles increase risk for heavy smoking. Molecular Psychiatry. 2008;13:368–373. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4002154. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/sj.mp.4002154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boden JM, Fergusson DM, Horwood LJ. Cigarette smoking and depression: tests of causal linkages using a longitudinal birth cohort. British Journal of Psychiatry. 2010;196:440–446. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.109.065912. doi:10.1192/bjp.bp.109.065912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brook DW, Brook JS, Zhang C, Cohen P, Whiteman M. Drug use and the risk of major depressive disorder, alcohol dependence, and substance use disorders. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2002;59:1039–1044. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.59.11.1039. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.59.11.1039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brook DW, Brook JS, Zhang C, Cohen P. Tobacco use and health in young adulthood. Journal of Genetic Psychology. 2004;65:310–323. doi: 10.3200/GNTP.165.3.310-323. doi:10.3200/GNTP.165.3.310-323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brook JS, Brook DW, Gordon AS, Whiteman M, Cohen P. The psychosocial etiology of adolescent drug use: A family interactional approach. Genetic, Social and General Psychology Monographs. 1990;116:111–267. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brook DW, Zhang C, Rosenberg G, Brook JS. Maternal cigarette smoking during pregnancy and child aggressive behavior. American Journal on Addictions. 2006;15:450–456. doi: 10.1080/10550490600998559. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/10550490600998559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell SB, Morgan-Lopez AA, Cox MJ, McLoyd VC. A latent class analysis of maternal depressive symptoms over 12 years and offspring adjustment in adolescence. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2009;118:479–493. doi: 10.1037/a0015923. doi:10.1037/a0015923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Adult smoking in the US. 2011 Sep; Vital Signs. Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/VitalSigns/pdf/2011-09-vitalsigns.pdf.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Smoking-attributable mortality, years of potential life lost, and productivity losses -- United States, 2000–2004. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 2008;57:1226–1228. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chase HW, Hogarth L. Impulsivity and symptoms of nicotine dependence in a young adult population. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2011;13:1321–1325. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntr114. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/ntr/ntr114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chassin L, Presson CC, Todd M, Rose JS, Sherman SJ. Maternal socialization of adolescent smoking: the intergenerational transmission of parenting and smoking. Developmental Psychology. 1998;34:1189–1201. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.34.6.1189. doi:10.1037//0012-1649.34.6.1189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chassin L, Curran PJ, Presson CC, Sherman SJ, Wirth RJ. Developmental trajectories of cigarette smoking from adolescence to adulthood: An overview and relations to indicators of tobacco dependence. In: Swan GE, Baker TB, Chassin L, Conti DV, Lerman C, Perkins KA, editors. Phenotypes and Endophenotypes: Foundations for Genetic Studies of Nicotine Use and Dependence. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, National Institutes of Health, National Cancer Institute; Bethesda, MD: 2009. pp. 189–244. Tobacco Control Monograph No. 20. (NIH Publication No. 09-6366.) [Google Scholar]

- Chen LS, Baker TB, Piper ME, Breslau N, Cannon NS, Doheny KF, Bierut LJ. Interplay of genetic risk factors (CHRNA 5 -CHRNA 3 -CHRNB4) and cessation treatments in smoking cessation success. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2012;169:735–742. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2012.11101545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark C, Rodgers B, Caldwell T, Power C, Stansfeld S. Childhood and adulthood psychological ill health as predictors of midlife affective and anxiety disorders: The 1958 British Birth Cohort. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2007;64:668–678. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.64.6.668. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.64.6.668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen P, Cohen J. Life Values and Adolescent Mental Health. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; Mahwah, NJ: 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Colman I, Wadsworth ME, Croudace TJ, Jones PB. Forty-year psychiatric outcomes following assessment for internalizing disorder in adolescence. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2007;164:126–133. doi: 10.1176/ajp.2007.164.1.126. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.164.1.126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Degenhardt L, Hall W. The relationship between tobacco use, substance-use disorders and mental health: Results from the National Survey of Mental Health and Well-being. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2001;3:225–234. doi: 10.1080/14622200110050457. doi:10.1080/14622200110050457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dekker MC, Ferdinand RF, van Lang ND, Bongers IL, van der Ende J, Verhulst FC. Developmental trajectories of depressive symptoms from early childhood to late adolescence: Gender differences and adult outcome. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2007;48:657–666. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2007.01742.x. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7610.2007.01742.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Derogatis LR, Lipman RS, Rickels K, Uhlenhuth EH, Covi L. The Hopkins Symptom Checklist (HSCL): A self-report symptom inventory. Behavioral Science. 1974;19:1–15. doi: 10.1002/bs.3830190102. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/bs.3830190102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D'Onofrio BM, Rickert ME, Langström N, Donahue KL, Coyne CA, Larsson H, Ellingson JM, Lichtenstein P. Familial confounding of the association between maternal smoking during pregnancy and offspring substance use and problems. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2012;69:1140–1150. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2011.2107. http://dx.doi.org/10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2011.2107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D'Onofrio BM, Van Hulle CA, Waldman ID, Rodgers JL, Harden KP, Rathouz PJ, Lahey BB. Smoking during pregnancy and offspring externalizing problems: An exploration of genetic and environmental confounds. Development & Psychopathology. 2008;20:139–164. doi: 10.1017/S0954579408000072. http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S0954579408000072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fagan P, Shavers VL, Lawrence D, Gibson JT, O'Connell ME. Employment characteristics and socioeconomic factors associated with disparities in smoking abstinence and former smoking among U.S. workers. Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved. 2007;18:52–72. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2007.0119. doi:10.1353/hpu.2007.0119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fitzpatrick C, Barnett TA, Pagani LS. Parental bad habits breed bad behaviors in youth: exposure to gestational smoke and child impulsivity. International Journal of Psychophysiology. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpsycho.2012.11.006. in press. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ijpsycho.2012.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Flouri E. Women's psychological distress in midadulthood: The role of childhood parenting experiences. European Psychologist. 2005;10:116–123. doi:10.1027/1016-9040.10.2.116. [Google Scholar]

- Frosch ZA, Dierker LC, Rose JS, Waldinger RJ. Smoking trajectories, health, and mortality across the adult lifespan. Addictive Behaviors. 2009;34:701–704. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2009.04.007. doi:10.1016/j.addbeh.2009.04.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilman SE, Rende R, Boergers J, Abrams DB, Buka SL, Clark MA, Niaura RS. Parental smoking and adolescent smoking initiation: An intergenerational perspective on tobacco control. Pediatrics. 2009;123:e274–281. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-2251. doi:10.1542/peds.2008-2251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodman A, Joyce R, Smith JP. The long shadow cast by childhood physical and mental problems on adult life. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2011;108:6032–6037. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1016970108. doi:10.1073/pnas.1016970108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gough HG. The California Psychological Inventory. Consulting Psychological Press; Palo Alto, CA: 1957. [Google Scholar]

- Hammen C, Shih JH, Brennan PA. Intergenerational transmission of depression: test of an interpersonal stress model in a community sample. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2004;72:511–522. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.72.3.511. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0022-006X.72.3.511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu MC, Davies M, Kandel DB. Epidemiology and correlates of daily smoking and nicotine dependence among young adults in the United States. American Journal of Public Health. 2006;96:299–308. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2004.057232. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2004.057232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Institute of Medicine . In: Ending the tobacco problem: A blueprint for the nation. Bonnie RJ, Stratton K, Wallace RB, editors. The National Academies Press; Washington, DC: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson W, Kyvik KO, Mortensen EL, Skytthe A, Batty GD, Deary IJ. Does education confer a culture of healthy behavior? Smoking and drinking patterns in Danish twins. American Journal of Epidemiology. 2011;173:55–63. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwq333. doi:10.1093/aje/kwq333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnston LD, O'Malley PM, Bachman JG, Schulenberg JE. Monitoring the Future national survey results on drug use, 1975–2005: Volume I, Secondary School Students (NIH Publication No. 06–5883) National Institute on Drug Abuse; Bethesda, MD: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Kelloway EK. Using LISREL for structural equation modeling. Sage; Thousand Oaks, CA: 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Kelly AB, O'Flaherty M, Connor JP, Homel R, Toumbourou JW, Patton GC, Williams J. The influence of parents, siblings and peers on pre- and early-teen smoking: A multilevel model. Drug and Alcohol Review. 2011;30:381–387. doi: 10.1111/j.1465-3362.2010.00231.x. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1465-3362.2010.00231.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kendler KS, Myers JM, Maes HH, Keyes CL. The relationship between the genetic and environmental influences on common internalizing psychiatric disorders and mental well-being. Behavioral Genetics. 2011;41:641–650. doi: 10.1007/s10519-011-9466-1. doi:10.1007/s10519-011-9466-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khantzian EJ, Albanese MJ. Understanding Addiction as Self Medication: Finding Hope Behind the Pain. Rowman and Littlefield; Lanham, MD: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Klungsøyr O, Nygård JF, Sørensen T, Sandanger I. Cigarette smoking and incidence of first depressive episode: An 11-year, population-based follow-up study. American Journal of Epidemiology. 2006;163:421–432. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwj058. doi:10.1093/aje/kwj058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawlor DA, O'Callaghan MJ, Mamun AA, Williams GM, Bor W, Najman JM. Early life predictors of adolescent smoking: findings from the Mater-University study of pregnancy and its outcomes. Paediatric and Perinatal Epidemiology. 2005;19:377–387. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3016.2005.00674.x. doi:10.1111/j.1365-3016.2005.00674.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leonardi-Bee J, Jere ML, Britton J. Exposure to parental and sibling smoking and the risk of smoking uptake in childhood and adolescence: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Thorax. 2011;66:847–855. doi: 10.1136/thx.2010.153379. doi:10.1136/thx.2010.153379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lieb R, Schreier A, Pfister H, Wittchen H. Maternal smoking and smoking in adolescents: A prospective community study of adolescents and their mothers. European Addiction Research. 2003;9:120–130. doi: 10.1159/000070980. http://dx.doi.org/10.1159/000070980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim SS, Vos T, Flaxman AD, Danaei G, Shibuya K, Adair-Rohani H, Ezzati M. A comparative risk assessment of burden of disease and injury attributable to 67 risk factors and risk factor clusters in 21 regions, 1990-2010: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet. 2012;380:2224–2260. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61766-8. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61766-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKenzie M, Olsson CA, Jorm AF, Romaniuk H, Patton GC. Association of adolescent symptoms of depression and anxiety with daily smoking and nicotine dependence in young adulthood: Findings from a 10-year longitudinal study. Addiction. 2010;105:1652–1659. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2010.03002.x. doi:10.1111/j.1360-0443.2010.03002.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén B, Kaplan D, Hollis M. On structural equation modeling with data that are not missing completely at random. Psychometrika. 1987;52:431–462. doi:10.1007/BF02294365. [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, Muthén BO. Mplus user's guide. 6th ed. Muthén & Muthén; Los Angeles, CA: 1998–2010. Retrieved from http://www.statmodel.com/download/usersguide/Mplus%20Users%20Guide%20v6.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Ng DM, Jeffery RW. Relationships between perceived stress and health behaviors in a sample of working adults. Health Psychology. 2003;22:638–642. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.22.6.638. doi:10.1037/0278-6133.22.6.638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orlando M, Ellickson PL, Jinnett K. The temporal relationship between emotional distress and cigarette smoking during adolescence and young adulthood. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2001;69:959–970. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.69.6.959. doi:10.1037//0022-006X.69.6.959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osler M, Clausen J, Ibsen KK, Jensen G. Maternal smoking during childhood and increased risk of smoking in young adulthood. International Journal of Epidemiology. 1995;24:710–714. doi: 10.1093/ije/24.4.710. doi:10.1093/ije/24.4.710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papp LM, Cummings EM, Goeke-Morey MC. Parental psychological distress, parent-child relationship qualities, and child adjustment: Direct, mediating, and reciprocal pathways. Parenting: Science and Practice. 2005;5:259–283. doi:10.1207/s15327922par0503_2. [Google Scholar]

- National Research Council and Institute of Medicine . Depression in Parents, Parenting, and Children: Opportunities to Improve Identification, Treatment, and Prevention Committee on Depression, Parenting Practices, and the Healthy Development of Children. Board on Children, Youth, and Families. Division of Behavioral and Social Sciences and Education. The National Academies Press; Washington, DC: 2009. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Callaghan FV, O'Callaghan M, Najman JM, Williams GM, Bor W, Alati R. Prediction of adolescent smoking from family and social risk factors at 5 years, and maternal smoking in pregnancy and at 5 and 14 years. Addiction. 2006;101:282–290. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2006.01323.x. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1360-0443.2006.01323.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patterson JM, Eberly LE, Ding Y, Hargreaves M. Associations of smoking prevalence with individual and area level social cohesion. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health. 2004;58:692–697. doi: 10.1136/jech.2003.009167. doi:10.1136/jech.2003.009167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roza SJ, Hofstra MB, van der Ende J, Verhulst FC. Stable prediction of mood and anxiety disorders based on behavioral and emotional problems in childhood: A 14-year follow-up during childhood, adolescence, and young adulthood. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2003;160:2116–2121. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.160.12.2116. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.160.12.2116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryan KK, Mackillop J, Carpenter MJ. The relationship between impulsivity, risk-taking propensity and nicotine dependence among older adolescent smokers. Addictive Behaviors. 2013;38:1431–1434. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2012.08.013. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2012.08.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sargent JD, Dalton M. Does parental disapproval of smoking prevent adolescents from becoming established smokers? Pediatrics. 2001;108:1256–1262. doi: 10.1542/peds.108.6.1256. doi:10.1542/peds.108.6.1256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaefer ES. Children's report of parental behavior: An inventory. Child Development. 1965;36:413–424. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaefer ES, Finkelstein NW. Child behavior toward parents: An inventory and factor analysis. Paper presented at: 83rd Annual Meeting of American Psychological Association; Chicago, IL. 1975, August 30–September 2. [Google Scholar]

- Saccone NL, Wang JC, Breslau N, Johnson EO, Hatsukami D, Saccone SF, Bierut LJ. The CHRNA5-CHRNA3-CHRNB4 nicotinic receptor subunit gene cluster affects risk for nicotine dependence in African-Americans and in European-Americans. Cancer Research. 2009;69:6848–6856. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-0786. http://dx.doi.org/10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-0786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shenassa ED, McCaffery JM, Swan GE, Khroyan TV, Shakib S, Lerman C, Santangelo SL. Intergenerational transmission of tobacco use and dependence: A transdisciplinary perspective. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2003;5(Suppl 1):S55–S69. doi: 10.1080/14622200310001625500. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/14622200310001625500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slominski L, Sameroff A, Rosenblum K, Kasser T. Longitudinal predictors of adult socioeconomic attainment: The roles of socioeconomic status, academic competence, and mental health. Development and Psychopathology. 2011;23:315–324. doi: 10.1017/S0954579410000829. doi:10.1017/S0954579410000829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sorensen G, Barbeau E, Hunt MK, Emmons K. Reducing social disparities in tobacco use: a social-contextual model for reducing tobacco use among blue-collar workers. American Journal of Public Health. 2004;94:230–239. doi: 10.2105/ajph.94.2.230. doi:10.2105/AJPH.94.2.230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Office of Applied Studies . The NSDUH Report: Adolescent Smoking and Maternal Risk Factors. Rockville, MD: May 7, 2010a. Retrieved from http://www.samhsa.gov/data/2k10/166/166SmokingMomsHTML.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration . Results from the 2009 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: Volume I. Summary of National Findings (Office of Applied Studies, NSDUH Series H-38A, HHS Publication No. SMA 10-4586 Findings) Rockville, MD: 2010b. [Google Scholar]

- Suldo S, Thalji A, Ferron J. Longitudinal academic outcomes predicted by early adolescents' subjective well-being, psychopathology, and mental health status yielded from a dual factor model. The Journal of Positive Psychology. 2011;6:17–30. doi:10.1080/17439760.2010.536774. [Google Scholar]

- Sun J, Buys N, Stewart D, Shum D. Mediating effects of coping, personal belief, and social support on the relationship among stress, depression, and smoking behaviour in university students. Health Education. 2011;111:133–146. doi:10.1108/09654281111108544. [Google Scholar]

- Thorgeirsson TE, Geller F, Sulem P, Rafnar T, Wiste A, Magnusson KP, Stefansson K. A variant associated with nicotine dependence, lung cancer and peripheral arterial disease. Nature. 2008;452:638–642. doi: 10.1038/nature06846. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/nature06846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vink JM, Willemsen G, Boomsma DI. The association of current smoking behavior with the smoking behavior of parents, siblings, friends and spouses. Addiction. 2003;98:923–931. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2003.00405.x. doi:10.1046/j.1360-0443.2003.00405.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weden MM, Miles JN. Intergenerational relationships between the smoking patterns of a population-representative sample of US mothers and the smoking trajectories of their children. American Journal of Public Health. 2012;102:723–731. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300214. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2011. 300214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White VM, Hopper JL, Wearing AJ, Hill DJ. The role of genes in tobacco smoking during adolescence and young adulthood: a multivariate behaviour genetic investigation. Addiction. 2003;98:1087–1100. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2003.00427.x. http://dx.doi.org/10.1046/j.1360-0443.2003.00427.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yong HH, Borland R, Thrasher JF, Thompson ME. Stability of cigarette consumption over time among continuing smokers: a latent growth curve analysis. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2012;14:531–539. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntr242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.