Abstract

Although alcohol use disorders (AUDs) have been associated with different aspects of disinhibited personality and antisociality, less is known about the specific relationships among different domains of disinhibited personality, antisociality, alcohol use, and alcohol problems. The current study was designed to address three goals, (i) to provide evidence of a three-factor model of disinhibited personality (comprised of impulsivity [IMP], risk taking/ low harm avoidance [RTHA], excitement seeking [ES]), (ii) to test hypotheses regarding the association between each dimension and alcohol use and problems, and (iii) to test the hypothesis that antisociality (social deviance proneness [SDP]) accounts for the direct association between IMP and alcohol problems, while ES is directly related to alcohol use. Measures of disinhibited personality IMP, RTHA, ES and SDP and alcohol use and problems were assessed in a sample of young adults (N=474), which included a high proportion of individuals with AUDs. Confirmatory factor analyses supported a three-factor model of disinhibited personality reflecting IMP, RTHA, and ES. A structural equation model (SEM) showed that IMP was specifically associated with alcohol problems, while ES was specifically associated with alcohol use. In a second SEM, SDP accounted for the majority of the variance in alcohol problems associated with IMP. The results suggest aspects of IMP associated with SDP represent a direct vulnerability to alcohol problems. In addition, the results suggest that ES reflects a specific vulnerability to excessive alcohol use, which is then associated with alcohol problems, while RTHA is not specifically associated with alcohol use or problems when controlling for IMP and ES.

Keywords: Personality, Disinhibition, Antisociality, Alcohol Use, Alcohol Problems

1. INTRODUCTION

Poor self-regulation is a fundamental feature of alcohol use disorders (AUDs). AUDs are associated with disinhibited – undercontrolled personality (Finn, Sharkansky, Brandt, & Turcotte, 2000; Finn, Mazas, Justus, & Steinmetz, 2002; Sher Walitzer, Wood, & Brent, 1991) and antisociality (Finn et al., 2002; Finn & Hall, 2004; Iacono, Carlson, Taylor, Elkins, & McGue, 1999), both of which reflect problems with self-regulation. Although a range of studies have established associations between AUDs and several domains of disinhibited personality, such as impulsivity, novelty seeking, sensation seeking, low harm avoidance (risk taking), and antisocial traits (Finn et al., 2000, Grekin, Sher & Wood, 2006) it is less clear whether these different trait domains reflect separate, specific vulnerabilities to excessive alcohol use or problems. In addition, disinhibited personality includes a number of diverse, but interrelated, personality traits, such as impulsivity, low harm avoidance, excitement seeking, or general sensation seeking. While each of these traits has been associated with alcohol use and problems when considered univariately or when combined into broader trait dimensions such as sensation seeking (e.g., Castellanos-Ryan, Rubia, & Conrod, 2011; Chassin, Flora, & King, 2004, Sher et al., 1991; Smith et al., 2007; Wills, Vaccaro & McNamara, 1994; Whiteside & Lynam, 2003), some research suggests that specific traits (e.g., impulsivity and sensation seeking) reflect different mechanisms associated with a vulnerability to AUDs (Castellanos-Ryan et al, 2011; Magid, McClean, & Colder, 2007; Smith et al., 2007).

Although the specific nature of the personality constructs themselves suggest different mechanisms (Finn, 2002), it is difficult to identify specific personality-related pathways or vulnerabilities to AUDs, because many studies of personality and AUDs focus on a single trait domain or measure, rather than a range of unique traits. In addition, antisociality, or social deviance proneness, which has been shown to have strong associations with AUDs (Finn et al., 2000; Finn & Hall, 2004; Grekin et al., 2006; Iacono et al., 1999; Kendler, Prescott, Myers, & Neale, 2003; Mustanski, Viken, Kaprio & Rose, 2003), represents a trait phenotype somewhere between a basic personality trait and a clinical phenotype. Many studies of personality and AUDs exclude measures of antisociality, others have included antisociality, but excluded other key domains of disinhibited personality (Finn et al., 2000; Finn & Hall, 2004), and still others have included aspects of disinhibited personality and social deviance into a single latent variable of behavioral undercontrol (Sher et al., 1991). The overarching purpose of the current study is to investigate the specific dimensions of disinhibited personality and their associations with excessive alcohol use and alcohol problems. This broad purpose is accomplished by addressing two specific goals using two different methods. The first goal is to test a three-dimensional model of disinhibited personality using Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA). The second goal is to investigate evidence for specific personality-related mechanisms of vulnerability to excessive alcohol involvement. This second goal will be addressed by testing hypotheses regarding specific personality-related pathways (see below) using Structural Equation Models (SEMs) that include the three hypothesized dimensions of disinhibited personality as well as a measure of antisociality (social deviance proneness).

1.1. Personality, Social Deviance Proneness, and Alcohol Use and Problems

We theorize a model of disinhibited personality comprised of three interrelated dimensions of impulsivity, excitement seeking, and low harm avoidance (risk taking) (Finn, 2002). Impulsivity is narrowly defined and reflects basic problems in self-regulation associated with increased appetitive motivation in combination with difficulties inhibiting approach behavior (e.g., de Wit, 2009; Finn, 2002; Luego, Carillo de la Pena, & Ortero, 1991; Patton, Stanford, & Barratt,1995; Swann, Bjork, Moeller, & Dougherty, 2002).

Our approach to conceptualizing impulsivity narrowly is in contrast to the approach taken by Whiteside and Lynam (2001) and others (Evenden, 1999; Gullo, et al. 2010; MacKillop et al., 2007) who define impulsivity more broadly to include domains such as sensation seeking (including risk-taking and our construct of excitement seeking). Recent work suggests that sensation seeking and impulsivity reflect distinct constructs that have unique associations with different facets of alcohol use disorders (Castellanos-Ryan et al, 2011; Curcio & George, 2011; Smith et al., 2007), where sensation seeking was associated with alcohol use and negative urgency was associated with alcohol problems. Our approach extends this work further by decomposing sensation seeking into two constructs, excitement seeking and risk taking and proposing that the domain of excitement seeking is specifically associated with increased approach tendencies and excessive drinking, while risk-taking is not likely to be uniquely associated with excessive alcohol involvement in emerging / young adulthood.

Excitement seeking, a subdomain of sensation seeking, reflects increased approach tendencies and a general reliance on engaging in pleasurable-hedonistic – type approach behaviors to feel good and a tendency to experience boredom and negative affect when not actively engaged in appetitive behavior or when engaging in routine activity (Finn, 2002). Based on theory that excitement seeking is associated with increased approach, while impulsivity is associated with problems in self regulation, we hypothesize that excitement seeking will be uniquely associated with excessive alcohol use and impulsivity will be associated with more alcohol-use-related problems. Risk taking / low harm avoidance, on the other hand, is thought to reflect reduced activity in the aversive motivation system (Finn, 2002) and reflects a number of related mechanisms, including fearlessness, low behavioral inhibition to the prospect of aversive experience, and the experience of the physiological arousal inherent in dangerous situations as pleasurable rather than aversive (Finn, 2002; Justus & Finn, 2007; Ziv, Tomer, Defrin, & Hendler, 2010). Studies indicate that risking taking / low harm avoidance is associated with risk for excessive substance use in childhood and adolescence (Mâsse & Tremblay, 1997; Wills et al., 1994). However we propose that the association between risk taking and excessive alcohol use in emerging adulthood (18–25 years of age) will be weaker and that risk taking is not uniquely associated with excessive alcohol use, because excessive alcohol use in this developmental phase is not perceived as a very risky behavior (Chomynova, Miller & Beck, 2009; Finn, 2002), while alcohol use in childhood and adolescence is associated with more risk. Some research suggests that impulsivity and excitement seeking/ sensation seeking reflect different aspects of a vulnerability to AUDs (Castellanos-Ryan et al, 2011; Magid et al., 2007 Smith et al., 2007). We extend this further by postulating that social deviance proneness, or antisociality, plays a central role in the association between impulsivity and AUDs.

While we conceptualize impulsivity as a more generalized vulnerability to poor self-regulation, social deviance proneness, indexed by the Psychopathic Deviance scale of the MMPI-II (Hathaway & McKinley, 1989) and the Socialization (So) scale of the California Psychological Inventory (Gough, 1969) reflects a vulnerability to poor self-regulation in response to social norms, and interpersonal and contextual cues for appropriate behavior (Finn et al., 2000). High social deviance is associated with a general disregard for social norms, authority, and a tendency toward rule-breaking, delinquent behavior. We propose that social deviance reflects a particular facet of impulsivity where strong approach motivation is not sufficiently inhibited by social norms for appropriate behavior. This facet of impulsivity is particularly relevant for alcohol problems since a great deal of the problems related to alcohol abuse are associated with the violation of social norms for respectful, responsible, healthy behavior in domains of work, family, and interpersonal relationships (Finn et al, 2000; Finn & Hall, 2004). The general idea that antisociality accounts for much of the association between impulsivity and alcohol problems is consistent with the results of Whiteside & Lynam (2003), who reported that some personality traits related to impulsive behavior (from the UPPS scales; Whiteside & Lynam, 2001) are only related to alcohol abuse in groups who are also high in antisocial traits. We extend this further by postulating that social deviance proneness, or antisociality, plays a central role in the association between impulsivity and AUDs.

The overarching aim of the current study was to delineate the specific associations among three domains of disinhibited personality (impulsivity, excitement seeking, risk taking/low harm avoidance), social deviance proneness, and alcohol use and problems in order to provide evidence for different vulnerability processes. The study tested the following specific hypotheses: (i) confirmatory factor analyses will support a three factor model of disinhibited personality, (ii) in a structural equation model (SEM) that examines the association between the three dimensions of disinhibited personality and alcohol use and problems, impulsivity will be directly associated with more alcohol problems and excitement seeking will be directly associated with more alcohol use, and (iii) in another SEM, social deviance proneness will account for the variance the association between impulsivity and alcohol problems.

2. MATERIALS AND METHOD

2.1 Participants

2.1.1 Recruitment

Participants were recruited for a large study of behavioral disinhibition in early onset alcoholism by targeting a large sample of participants who met diagnostic criteria for alcohol dependence and who also varied widely in other externalizing disorders (cf. Finn et al., 2009). This was accomplished using a recruitment strategy designed to select a sample that varied widely in disinhibited, externalizing behavior with approximately half of the sample meeting DSM-IV criteria (American Psychological Association, 1994) for alcohol dependence (Finn et al., 2009). The recruitment strategy, outlined below, used advertisements designed to recruit this sample of alcohol dependent subjects who varied considerably in their level of disinhibited, externalizing behaviors and problems. In Finn et al. (2009), we showed substantial heterogeneity within the alcohol dependent sample on measures of externalizing problems and cognitive capacity. This strategy involved using newspaper advertisements and flyers placed around a university campus and local town asking for responses from persons who varied in terms of alcohol consumption levels, alcohol problems, antisocial behavior, impulsivity, and social deviance (cf. Finn et al., 2009; Cantrell et al., 2008). The advertisements / flyers requested responses from a range of types of individuals using statements such as: “Are you a heavy drinker?”, “ Did you get into a lot of trouble as a child?”, “Are you a more reserved and introverted type of person?”, “WANTED: Subjects interested in psychological research”, “Are you impulsive?”, “WANTED: Males/Females, 18–25 yrs old, who only drink modest amounts of alcohol and who do not take drugs.”, “Do you think you have a drinking problem?”, “Are you adventurous (daring, etc)?: Psychologist studying adventurous carefree people who have led exciting impulsive lives…”.

2.1.2 Telephone screening interview

Each participant who responded to the advertisements and flyers was administered a telephone screening interview. The interview began with a short description about the nature of the study, followed by a series of questions regarding the predetermined inclusion/exclusion criteria. Criteria questions addressed demographic and medical information, symptoms of alcohol and drug abuse and dependence, childhood conduct disorder, antisocial personality disorder, and attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder. Those who met the criteria were then described additional necessary information about the study. Potential participants were told the study would take a total of nine hours, divided into three testing sessions; and would be compensated with hourly pay for their participation. Participants were informed they would be asked to complete a breath alcohol test upon arrival at the laboratory. It was requested that they refrain from consuming alcoholic beverages or using recreational drugs within 12 hours of arriving for the experiment. It was also requested that they get at least 6 hours of sleep the night before and eat within 3 hours of the testing session.

2.1.3 Study exclusion criteria

Participants were excluded from the study if they (a) were not between the ages of 18 and 30, (b) could not read or speak English, (c) did not have at least a 6th grade education level, (d) had never consumed alcohol, (e) were currently taking prescription drugs that affect behavior, (f) had a history of severe psychological problems, (g) or a history of major cognitive impairments or head trauma. At the beginning of each session, participants were asked about their alcohol and drug use over the past 12 hours and were given a breath alcohol test using an Alco Sensor IV (Intoximeters Inc., St. Louis, MO). If a participant reported using any drugs within the past 12 hours, had a breath alcohol level above 0.0%, reported feeling hung over or sleepy, or were unable to answer test questions, they were excluded from participation at that session and rescheduled.

2.1.4 Sample Characteristics

The entire sample consisted of 463 young adults, 215 males and 248 females. Sixty-four percent of participants were college students, (M = 22.0 years, SD=.50) with a mean years of education of 13.8 years (SD = 2.0). Ethnicity breakdown of the sample consisted of 77% Caucasian, 12% African-American, 6% Asian, 3% Hispanic, and 2% accounted for other ethnic backgrounds. Fifty-six percent of the sample (n=260; 153 men; 118 women) met DSM-IV (American Psychiatric Association, 1994) diagnostic criteria for alcohol dependence. Our recruitment strategy also resulted in a relatively high prevalence of disinhibited characteristics in the non-alcohol dependent subjects evidenced by the fact that 35% of these subjects had a history of conduct disorder without alcohol dependence. DSM-IV diagnostic status was ascertained using the Semi-Structured Assessment for the Genetics of Alcoholism (SSAGA; Bucholz et al., 1994) administered by extensively trained research technicians and clinical psychology graduate students.

2.2 Measures

2.2.1 Alcohol use and problems

Alcohol use was assessed using an interview asking questions about typical alcohol use over the past 6 months. Participants were asked about how much they typically drink on a Monday, Tuesday, Wednesday, etc. Alcohol use was measured with two different variables: frequency (occasions per week) and average quantity consumed per occasion. The frequency and quantity measures were square-root transformed and used as indicators of a latent alcohol-use variable in the structural models. Alcohol problems was assessed as a single observed variable and quantified as the total number of positive responses to questions in the alcohol abuse and dependence section of the SSAGA (Bucholz et al., 1994) (dichotomous “yes” vs “no” response scoring format; α = .97). Problem counts included all questions in the alcohol abuse/dependence section of the SSAGA, some of which are not considered in establishing DSM-IV diagnoses, but are part of the interview for assessing diagnoses in other systems, such as RDC (Spitzer, Endicott, & Robbins, 1978), Feighner (Feighner et al., 1972), DSM-III-R (APA, 1987), and ICD-10 systems (World Health Organization, 1993). Alcohol problems were square-root transformed for SEM analyses because of a skewed distribution.

2.2.2 Personality assessment

Specific scales were selected for the three domains of disinhibited personality because they were specific measures of the constructs of interest. Previous research (Finn, 2002; Finn et al., 2002, 2000) suggests that these scales are valid assessments of these three latent personality traits. The measures of impulsivity have been associated with poor response inhibition in approach contexts (Finn et al., 2002), increased discounting of delayed rewards (Bobova et al., 2009), and increased alcohol problems (Bobova et al., 2009, Finn, 2002, Finn et al., 2002). The measures of low harm avoidance have been associated with antisocial behavior (Finn, 2002), engaging in risky behaviors (Tellegen & Waller, 1992), difficulties inhibiting behavior to avoid aversive consequences, such as electric shock (Finn et al., 2002), and decreased potentiation of startle in the presence of aversive stimuli (Justus & Finn, 2007), which suggests decreased fearfulness. Finally, the measures of excitement seeking have been consistently associated with increased alcohol and other substance use (Castellanos-Ryan, et al., 2011, Finn et al., 2000, Finn & Hall, 2004), higher positive alcohol expectancies (Finn et al., 2000), and sexual promiscuity (Justus, Finn, & Steinmetz, 2000).

The impulsivity latent variable (IMP) was assessed with the total scores of the 19-item Impulsivity scale (Imp) (dichotomous “yes” vs “no” response scale; α = .84) from the Eysenck Impulsivity I6 Questionnaire (Eysenck, Pearson, Easting, & Allsop, 1985), the 24-item Control scale (Cont) (mostly forced choice or true-false response scale; α = .88) from the Multidimensional Personality Questionnaire (MPQ; Tellegen, 1982), and the 20-item Novelty-Seeking subscale (Nov) (5 point response scale; [1- definitely false to 5 definitely true] α = .78) from the 144 item version of Cloninger’s Temperament and Character Inventory (TCI-144; Cloninger, 1995). The TCI-144 novelty seeking scale is a 20 item scale that is comprised of the items with the highest intra-item reliability (Cloninger, 1995). This version of Cloninger’s novelty seeking scale does not have the four subscales included in the original, longer version of the TCI (Cloninger, Pryzbec, Svrakic & Wetzel, 1994).

The risk taking / low harm avoidance latent variable (RTHA) was assessed with the total scores of the 10-item Thrill and Adventure Seeking subscale (Thrill) (forced choice response scale;α = .78) from the Sensation Seeking Scale (SSS; Zuckerman, 1979), the 28-item Harm Avoidance subscale (Harm) (mostly forced choice or true-false response scale; α = .87) of the MPQ (Tellegen, 1982), and the 16-item Venturesomeness scale (Ven) (dichotomous “yes” vs “no” response scale; α = .80) from the Eysenck I6 Questionnaire (Eysenck et al., 1985).

Finally, the Excitement Seeking latent variable (ES) was assessed with the total scores of the 7-item Disinhibition (Dis) (forced choice response scale; α = .54) scale and the10-item Boredom Susceptibility (Bore) (forced choice response scale; α = .54) scale of the SSS (Zuckerman, 1979). Three questions from the Dis that refer to drinking or drug use were dropped from the original 10 items to avoid criterion contamination with alcohol use and problem measures.

The indicators of the social deviance proneness latent variable (SDP) were the total scores of the 49-item Psychopathic Deviance (Pd) scale (dichotomous “yes” vs “no” response scale; α = .76) of the Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory - 2 (MMPI-2: Hathaway & McKinley, 1989) and the 49-item Socialization (So) scale (dichotomous “yes” vs “no” response scale; α = .97) of the California Psychological Inventory (Gough, 1969). One item was dropped from the Pd scale, (“I have used alcohol excessively”) because of criterion contamination. High scores on the MMPI-Pd scale have been associated with impulsivity, social/self alienation, problems with authorities and family, and antisocial practices (Hathaway & McKinley, 1989). Low So scores are associated with aggressive, uninhibited, and impulsive tendencies (Gough, 1960). These measures have been shown to discriminate family history positive from family history negative individuals in other studies (Finn et al., 1997) and are associated with alcohol problems (Finn et al., 2000).

2.3 Data Analysis

2.3.1 Approach

About five percent of subjects had missing data on some of the personality measures (not more than 2 measures). In all cases the data were missing at random and the missing data was handled by Full Information Maximum Likelihood imputation using all available measures for the imputation process. The primary data analysis methods were confirmatory factor analyses (CFA) to investigate the hypothesized three-factor model of disinhibited personality, and structural equation modeling (SEM) to test hypotheses about the association between personality, social deviance, alcohol use, alcohol problems. All measures except alcohol problems were assessed using latent variables. Pearson product moment correlations are reported to illustrate the strength and direction of the associations among the different indicator variables. CFA and SEM were conducted using AMOS 18.0 (Arbuckle, 2009).

2.3.2 Model Fit

To assess the degree to which the structural models fit the sample variance-covariance data, two criteria of model fit were relied upon: the Normed Fit Index (NFI: Bentler & Bonett, 1980), the Comparative Fit Index (CFI: Bentler, 1990), and the Root-mean-square error of residual approximation (RMSEA: Browne & Cudeck, 1993). Although guidelines for good fit vary, typically NFI and CFI values above .90 or .95 indicate very good fit (Browne &Cudeck, 1993; Hu & Bentler, 1999). An NFI value of .90 indicates that 90% of the saturated model is reproduced by a tested model. Generally speaking, RMSEA values at or below .08 reflect a reasonable fit to the data (Bentler & Bonett, 1980; Browne & Cudek, 1993); however, RMSEA values less than 0.06 are the rule of thumb criteria for a good fit to the data (Hu & Bentler, 1999).

2.3.4 Model Comparisons

The assessment of the best fit for competing measurement models was accomplished using the Bayesian information criterion (BIC) and chi-square statistics. The BIC was used to select which measurement (CFA) model of personality reproduced the observed variances and covariances with the fewest estimated parameters (i.e., the most parsimonious model). A lower BIC value indicates a superior comparative fit of the data in terms of the odds of the model with the lower value being superior to others (Raftery, 1995). A difference in BIC of 10 points between two models being compared indicates that the odds are approximately 150:1 that the model with the lower BIC value fits the data better than the higher BIC value model (Raftery, 1995).

An alternative models approach was used in a CFA to test the model fit of a three factor model of disinhibited personality against one and two-factor models. Latent variables were used to model these personality dimensions. A previously validated model in Finn (2002), indicating the presence of Impulsivity (IMP), Risk Taking / low Harm Avoidance (RTHA), and Excitement Seeking (ES) as independent dimensions of disinhibited personality is compared to single and two factor latent trait models. In order to fully confirm the three-factor model, the fit of several possible two-factor models and a single factor was compared to the fit of the hypothesized three-factor model using BIC measures of model fit. The first two-factor model consisted of an IMP-RTHA (Imp, Cont, Nov, Harm, Ven, Thrill) factor, and the ES (Dis, Bore) factor. The second consisted of an IMP-ES (Imp, Cont, Nov, Dis, Bore) factor and an RTHA (Harm, Ven, Thrill) factor. A third two-factor model consisted of an RTHA-ES (Harm, Ven, Thrill, Dis, Bore) factor and an IMP (Imp, Cont, Nov) factor. The single factor model included all eight indicators. BIC values for each model were compared to assess superior fit. In addition, we report χ2, NFI, and RMSEA measures of fit for each model as well.

SEM with maximum likelihood estimation was further used to test several hypothesized relationships. Model 1 included the latent disinhibitory personality traits (IMP, RTHA, and ES) as exogenous predictors of alcohol use and problems. A fully saturated model was compared to a model restricted to the hypothesized pathways from IMP to alcohol problems and ES to alcohol use. Model 2 included a latent variable of social deviance proneness as a mediator of the association between IMP and alcohol problems.

3. RESULTS

3.1 Confirmatory Factor Analysis of the 3-Factor Model of Disinhibited Personality

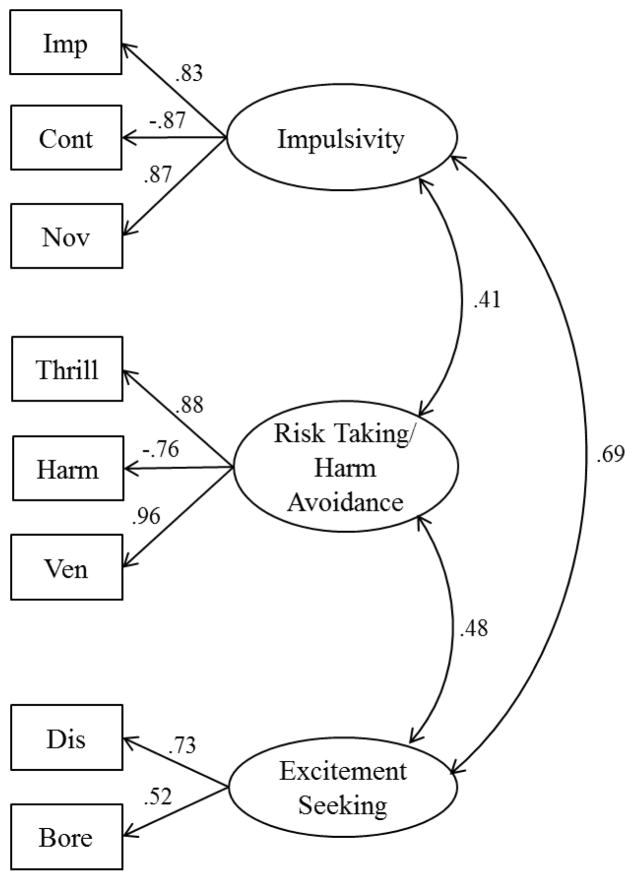

Table 1 presents the correlations among the variables used in the SEMs. As hypothesized, the indicator variables within each personality domain were strongly intercorrelated. A CFA showed that the hypothesized three factor model of disinhibited personality (IMP, RTHA, and ES) fit the data adequately, χ2 (17) = 69.9, p <.001; CFI= .98; NFI= .97; RMSEA= .08, BIC = 186.54. Table 2 presents the model fits for the three-factor model and each of the four comparison models. BIC values indicate that the three-factor model was the model with the superior fit. The next best fitting two-factor model had a BIC value 17 points greater than the three-factor model indicating a probability of over 200:1 that the three-factor model is a better fitting model (Raftery, 1995). The superior fit of the three factor model is evidenced by the other fit indices listed in Table 2 as well. Figure 1 displays the standardized regression weights for each factor and correlations between latent traits for this model of disinhibited personality.

Table 1.

Bivariate Correlations Among Personality Measures, Working Memory Capacity, and Recent Alcohol Use

| Variable | IMP | RTHA | ES | SDP | Alcohol Use | AlcProbs | Mean (SD) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||||||||

| 1. | 2. | 3. | 4. | 5. | 6. | 7. | 8. | 9. | 10. | 11. | 12. | 13. | ||

| 1. Imp | -- | −.74** | .71** | −.24** | .31** | .19** | .36** | .35** | .46** | −.56** | .31** | .31** | .51** | 10.3 (4.6) |

| 2. Cont | -- | −.75** | .32** | −.40** | −.27** | −.37** | −.40** | −.37** | .46** | −.28** | −.34** | −.47** | 11.4 (6.0) | |

| 3. Nov | -- | −.32** | .37** | .24** | .46** | .43** | . 37** | −.47** | .35** | .39** | .53** | 67.4 (11.0) | ||

| 4. Harm | -- | −.72** | −.69** | −.28** | −.18** | − .06 | .19* | −.17** | −.23** | −.16** | 14.8 (6.3) | |||

| 5. Ven | -- | .84** | .37** | .21** | .09 | −.19** | .25** | .28** | .26** | 10.1 (3.4) | ||||

| 6. Thrill | -- | .32** | .11* | .00 | − .07 | .20** | .22** | .11* | 6.7 (2.7) | |||||

| 7. Dis | -- | .38** | .12* | −.23* | .42** | .47** | .35** | 4.4 (1.7) | ||||||

| 8. Bore | -- | .24** | −.30** | .21** | .22** | .25** | 3.8 (2.0) | |||||||

| 9. Pd | -- | − .74** | .15* | .15 | .54** | 21.9 (6.3) | ||||||||

| 10. So | -- | −.20** | −.19 | −.57** | 28.9 (8.9) | |||||||||

| 11. AlcQ | -- | .74** | .51** | 2.1 (1.1) | ||||||||||

| 12. AlcF | -- | .47** | 1.6 (0.7) | |||||||||||

| 13. AlcProbs | -- | 4.6 (2.4) | ||||||||||||

Note. IMP = impulsivity; RTHA =Risk taking/ low harm avoidance; EX = excitement seeking; SDP = social deviance proneness Imp = Eysenck and Eysenck’s (1978) Impulsivity scale; Cont = Multidimensional Personality Questionnaire (MPQ) control scale; Nov = Tridimensional Character Inventory, Novelty Seeking scale; Harm = MPQ Harm Avoidance scale; Ven = Eysenck & Eysenck’s Venturesomeness scale; Thrill = Sensation Seeking Scale (SSS) Thrill & Adventure Seeking subscale; Dis = SSS Disinhibition scale; Bore = SSS Boredom Susceptibility scale; Pd = Psychopathic Deviate scale of the MMPI-2; So = Socialization scale of the Californian Personality Questionnaire; AlcQ = square root (Alcohol quantity); AlcF = square root (alcohol frequency); AlcProbs = square toor (Alcohol Problems)

p < .01,

p < .05

Table 2.

Model Fit Indices for Different Models in Confirmatory Factor Analysis

| Model | χ2 Statistics | CFI | NFI | RMSEA | BIC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Three Factor Model

|

χ2 = 69.9, df=17, p <.001 | 0.98 | 0.97 | 0.08 | 186.5 |

Two Factor Model

|

χ2 = 862.2, df=19, p <.000001 | 0.59 | 0.59 | 0.31 | 966.5 |

Two Factor Model

|

χ2 = 99.2, df=19, p <.000001 | 0.96 | 0.95 | 0.10 | 203.5 |

Two Factor Model

|

χ2 = 213.0, df=19, p <.000001 | 0.91 | 0.90 | 0.15 | 317.6 |

| Single Factor Model | χ2 = 878.7, df=20, p <.000001 | 0.59 | 0.58 | 0.30 | 976.9 |

Figure 1. Three-Factor Model of the Primary Dimensions of Disinhibited Personality.

Imp = Imp = Impulsivity scale of Eysenck & Eysenck’s (1978) Impulsivity scale; Cont = Control Scale from Multidimensional Personality Questionnaire (MPQ: Tellegen, 1982); Nov = Novelty Seeking Scale from Cloninger’s Tridimensional Character Inventory (TCI; 1994); Harm = MPQ Harm Avoidance scale; Ven = Eysenck & Eysenck’s Venturesomeness scale; Thrill = Thrill and Adventure Seeking subscale from the Sensation Seeking Scale (SSS: Zuckerman, 1979); Dis = SSS Disinhibition scale; Bore = SSS Boredom Susceptibility scale. Error terms are not presented. Single direction arrows depict regression paths (standard regression weights), and bidirectional curved arrows depict correlations. All paths are statistically significant at p < .001.

3.2 Personality, Alcohol Use, and Alcohol Problems

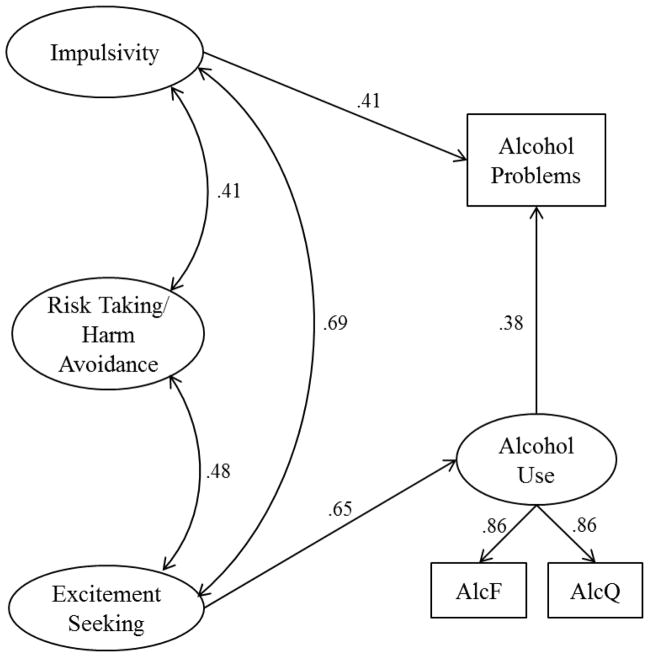

The SEM Model 1 of the hypothesized association between the three dimensions of disinhibited personality (exogenous variables), alcohol use, and alcohol problems fit the data adequately, χ2 (39) = 127.2, p <.001; CFI= .97; NFI= .96; RMSEA= .070, BIC = 292.97. This model is illustrated in Figure 2. Table 3 presents the model fit indices for all SEM models. The hypothesized (Final) model did not differ in fit from the Full Model, where each personality dimension was allowed to predict both alcohol use and alcohol problems, χ2 (35) = 122.5, p <.001; CFI= .97; NFI= .96; RMSEA= .074, BIC = 312.7. In the Final model (Figure 2), IMP was specifically associated with alcohol problems (β=. 41, p < .0001, R2 = .456), ES was specifically associated with alcohol use (β= .64, p < .0001), and alcohol use was significantly associated with alcohol problems (β= .38, p < .0001). In the Full Model the RTHA dimension was not significantly associated with either alcohol use (β= −.01, p = .99) or alcohol problems (β= −.04, p = .87). IMP also was not significantly associated with alcohol use (β= .03, p = .52) and ES was not significantly associated with alcohol problems (β= −.16, p = .18).

Figure 2. Single Structural Model of the Association between Disinhibited Personality Traits and Alcohol Use and Problems.

Previously defined latent personality trait indicators and error terms are not shown. AlcQ = 6 month alcohol quantity, AlcF = 6 month alcohol frequency. Rectangles depict observed variable, and ovals depict latent variables. Single direction arrows depict regression paths (standard regression weights), and bidirectional curved arrows depict correlations. Single arrow regression paths do not infer causal direction. All paths are statistically significant at p < .001.

Table 3.

Model Fit for Structural Equation Models

| Model | χ2 Statistics | CFI | NFI | RMSEA | BIC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1: Full Model | |||||

| Disinhibited Personality Traits, Alcohol Use and Problems | χ2 (35) = 122.5, p <.001 | 0.97 | 0.96 | 0.074 | 312.7 |

| Model 1: Hypothesized Model | |||||

| Impulsivity - > alcohol problems Excitement Seeking - > alcohol use |

χ2 (39) = 127.2, p <.001 | 0.97 | 0.96 | 0.070 | 293.0 |

| Model 2: Full Model | |||||

| Disinhibited Personality Traits, Social Deviance, Alcohol Use and Problems | χ2 (52) = 179.2, p <.0001 | 0.96 | 0.95 | 0.073 | 418.6 |

| Model 2: Hypothesized Model | |||||

| Impulsivity ->Social Deviance - > Alcohol Problems Excitement Seeking - > alcohol use |

χ2 (58) = 187.8, p <.0001 | 0.96 | 0.95 | 0.070 | 390.6 |

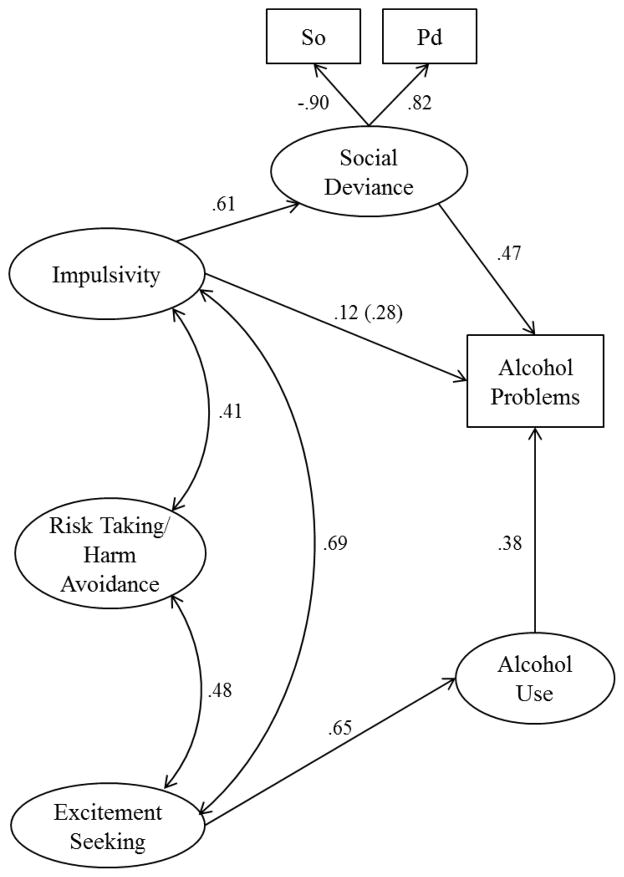

The SEM for Model 2 (Figure 3) that included social deviance as a mediator of the association between IMP and alcohol problems fit the data adequately, χ2 (58) = 187.8, p <.0001; CFI= .96; NFI= .95; RMSEA= .070, BIC = 390.56. This SEM shows that social deviance accounted for a significant portion of the variance in alcohol problems associated with IMP. In this model, IMP had only a modest direct association with alcohol problems (β= .12, p < .05), while social deviance had a strong effect on alcohol problems (β= .47, p < .0001). The indirect effect of IMP on alcohol problems (accounted for by social deviance) was highly significant (β= .28, p < .001). Together, social deviance and impulsivity predicted 59.9% of the variance in alcohol problems. The fully saturated Model 2 did not represent a superior fit to the hypothesized model, χ2 (52) = 179.2, p <.0001; CFI= .96; NFI= .95; RMSEA= .073, BIC = 418.58, indicating that social deviance is uniquely associated with the IMP pathway to alcohol problems when the three dimensions of disinhibited personality are considered simultaneously.

Figure 3. Single Structural Model of the Association between Disinhibited Personality Traits, Social Deviance Proneness, and Alcohol Use and Problems.

Previously defined latent personality trait indicators and error terms are not shown. Rectangles depict observed variable, and ovals depict latent variables. Single direction arrows depict regression paths (standard regression weights), and bidirectional curved arrows depict correlations. Single arrow regression paths do not infer causal direction. The indirect effect of impulsivity on alcohol problems (via social deviance) is presented in parentheses. All paths are statistically significant at p < .001.

4. DISCUSSION

The overarching purpose of the current study is to investigate the specific dimensions of disinhibited personality and their associations with excessive alcohol use and alcohol problems. Our results provide further evidence in support of a three-factor model of disinhibited personality comprised of dimensions of impulsivity, risk taking / low harm avoidance, and excitement seeking. Second, consistent with other studies (Magid et al., 2007) the results indicate that impulsivity is specifically associated with increased alcohol problems, while excitement seeking is specifically associated with elevated levels of alcohol use in a model that examines the association between all three domains of disinhibited personality and alcohol use and problems. These results (Model 1) suggest two separate vulnerability pathways or processes associated with aspects of disinhibited personality. Third, the analyses indicate the personality domain that reflects a general vulnerability to antisocial behavior, social deviance proneness, was specifically associated with the impulsivity pathway to alcohol problems and accounted for most of the variance in alcohol problems related to impulsivity. The results also indicate that risk taking / low harm avoidance does not reflect a specific mechanism that elevates risk for alcohol problems or excessive alcohol use in young adults independent of its association with impulsivity and excitement seeking.

4.1 Disinhibited Personality, Alcohol Use and Problems

We found a three factor model of disinhibited personality that included impulsivity, harm avoidance, and excitement seeking factors fit the data relatively well (Finn, 2002; Finn et al., 2002; Justus, Finn, & Steinmetz, 2001). This three factor model was far superior in fit to a single factor model and all possible two factor models of disinhibited personality. Our results suggest that impulsivity, harm avoidance (risk taking), and excitement seeking represent separate, but correlated, dimensions of disinhibited personality (Finn, 2002; Finn et al., 2002), rather than a unitary dimension of personality.

Furthermore, a structural model of the associations between the three factor model of disinhibited personality and alcohol use and problems provided additional evidence of the validity of our three factor model. The inclusion of the three domains of disinhibited personality in a model of the association between personality and alcohol use and problems represents a unique contribution to this literature. Impulsivity was directly associated with alcohol problems, while excitement seeking was directly associated with alcohol use, and alcohol use was associated with alcohol problems. On the other hand, risk taking / low harm avoidance did not represent a specific vulnerability to excessive alcohol use or alcohol problems independent of impulsivity and excitement seeking. Magid and colleagues (2007) observed a very similar pattern of results, although they did not assess risk taking and they employed a measure of monotony avoidance, which is very similar to our construct of excitement seeking. Additionally, Gullo and colleagues (2010) proposed a two-factor model of impulsivity that includes factors (rash impulsiveness and reward drive) that resemble our impulsivity and excitement seeking factors. They found that both factors were associated with hazardous alcohol use, which was measured as a single construct in terms of alcohol problems and excessive use. The current study differs from Gullo et al (2010) in that we start with a broader concept of disinhibited personality and provide support for three dimensions of disinhibited personality, define impulsivity narrowly, and conceptualize excitement seeking as distinct from impulsivity. Our model distinguished between alcohol problems and alcohol use and showed the impulsivity was specifically associated with problems and excitement seeking with use. Distinguishing between alcohol use and problems as outcome measures may have allowed for the identification of the distinct associations among excitement seeking and excessive alcohol use, and impulsivity and alcohol problems.

Although risk taking / low harm avoidance is associated with higher levels of alcohol use and problems, it is not associated with either alcohol use or problems when considered in a model together with impulsivity and excitement seeking. Risk taking / low harm avoidance may not be directly associated with alcohol use or problems in young adults because drinking is not considered as risky a behavior in young adults (Chomynova et al., 2009)as it might be in late childhood, a developmental phase where an association between low harm avoidance and drinking has been observed (Mâsse & Tremblay, 1997). In addition, earlier work from our laboratory suggests that low harm avoidance was more directly associated with antisocial behavior and insensitivity to aversive stimuli (Finn, 2002; Finn et al., 2002; Justus & Finn, 2007). The structural model also suggests that excitement seeking reflects a dimension of personality associated with seeking out appetitive and exciting experiences (Finn, 2002; Finn et al., 2000; Finn et al. 2002; Justus et al., 2001; Wills et al., 1994), such as drinking excessively in order to escape boredom.

Although impulsivity was associated with increased drinking levels in univariate analyses, it was specifically associated only with alcohol problems in the model. This is consistent with research indicating that impulsivity is associated with poor self-regulation, which, in this case, is reflected in higher levels of alcohol problems (Finn, 2002; Krueger, Caspi, Moffit, Silva, & McGee, 1996; Luego, Carrillo de la Pena, & Ortero, 1991; Magid, et al., 2007). Higher levels of impulsivity are associated with deficits in behavioral inhibition (Finn, 2002; Finn et al., 2002), poor emotional regulation (Trasseger & Robinson, 2009), increased discounting of delayed rewards (Bobova et al., 2009 Kirby, Petry, & Bickel, 1999), and reduced executive cognitive function (Dolan & Anderson, 2002; Finn, et al., 1999; Romer et al., 2009), all of which are associated with poor impulse control and may lead to behaviors such as continued drinking despite negative consequences.

Finally, Model 2 suggests that a vulnerability to antisocial behavior, indexed as social deviance proneness, is specifically associated with the pathway from impulsivity to alcohol problems. In fact, social deviance proneness accounted for most of the variance in alcohol problems associated with impulsivity. In a sense, this pattern of results qualifies the nature of the vulnerability to alcohol problems associated with impulsivity. The results suggest that it is the aspects of impulsivity that covary with antisociality that reflect most of the vulnerability to alcohol problems. Similar to other research, the current study indicates that antisociality, or social deviance proneness, represents an important aspect of the vulnerability to alcohol problems (Grekin et al., 2006; Sher & Gotham, 1999). The current work suggests that impulsivity reflects a key process underlying the association between antisociality and alcohol problems.

4.2 Limitations and Conclusions

There are a few limitations that should be considered when interpreting the results of this study. First, our data are cross-sectional in nature and cannot provide a true test of the theory that personality risk leads to alcohol use and problems. In addition, although the SEM path analyses include unidirectional regression paths, there is likely to be some bidirectionality in the effects. In other words, alcohol problems and excessive use may lead to more impulsive behavior, greater excitement seeking, or more social deviance (de Wit, 2009). Thus, one cannot make conclusions about causality from our results. Second, it should be noted that our sample is not randomly selected from the population. Rather, individuals in the study are biased toward those willing to participate in a research study conducted in a laboratory. The sample also is not representative of individuals in treatment for alcohol dependence. Some of our sample had sought and received treatment, but many of those with alcohol problems had not sought any sort of treatment for their problems, which is typical for college students with alcohol use disorders (Wu, Pilowsky, Schlenger & Hasin, 2007). Our sample also is limited in that it is comprised of mostly young white adults, two thirds whom are college students. However, it is worth noting that alcohol use disorders among college students are equal to (Wu et al., 2007), or higher than (Slutske, 2005), their peers who do not attend college. Although the severity of alcohol use disorders in college students is equivalent to their non-college-attending peers (Slutske, 2005), fewer seek treatment services for their alcohol-related problems (Wu et al., 2007). In addition, college students with AUDs are more likely to dropout and not complete their college studies (Slutske, 2005). Thus, although not representative of alcohol dependent individuals in treatment, the alcohol problems in this population represent a significant public health problem in the United States. Finally, because our sample is comprised of young adults in an emerging adulthood developmental phase, different patterns of association between the independent trait dimensions and alcohol use and problems may be present in comparison to late childhood, earlier adolescence, or middle age.

6. CONCLUSION

Despite these limitations, this research provides a more detailed account of the nature of the interrelationships between different dimensions of disinhibited personality, antisociality, and alcohol use and problems and suggests different vulnerability processes in alcohol use disorders. Besides providing further evidence for a three-factor model of disinhibited personality, our results suggest specific associations between impulsivity alcohol problems as well as between excitement seeking an alcohol use. Finally, the results underline the key association between impulsivity and alcohol problems, a significant portion of which is accounted for by social deviance/antisociality.

Highlights.

Analyses provide support for a three – dimensional model of basic disinhibitory personality traits that are differentially associated with alcohol use and problems

Impulsivity is directly associated with alcohol problems suggesting poor self-regulation contributes to problems related to alcohol consumption (problems regulating alcohol intake)

Excitement seeking, a specific subset of general sensation seeking, is associated with alcohol use, which is then related to alcohol problems.

Antisociality or social deviance proneness accounts for much of the association between impulsivity and alcohol problems, suggesting that problems regulating alcohol consumption to conform to social / interpersonal norms and expectations is a critical feature of the problems in self-regulation that are associated with alcohol problems in emerging adults.

Acknowledgments

We thank Jesolyn Lucas for her contributions to this research.

Role of Funding Sources: This research was supported by National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA) grant RO1 AA13650 to Peter R. Finn and a National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) training grant fellowship, T32 DA024628 to Rachel Gunn. The NIAAA and NIDA had no role in the study design, collection, analysis or interpretation of the data, writing the manuscript, or the decision to submit the paper for publication.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest. All authors declare that they have no conflict of interest in this research.

Contributors: Peter Finn and Rachel Gunn designed the study. Rachel Gunn and Peter Finn wrote the first draft of the manuscript together. Michael Endres contributed to the statistical analyses along with Rachel Gunn and Peter Finn. Suzanne Spinola conducted literature searches and provided summaries of previous research studies. Kyle Gerst managed the database, provided statistical analysis support, and prepared the figures. manaconducted the statistical analysis. All authors contributed to and have approved the final manuscript.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 3. APA Press; Washington, D.C: 1987. Revised. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 4. Washington, DC: Author; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Arbuckle JL. AMOS (Version 18. 0) [Computer software] Chicago: Small waters Corporation; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Bentler PM. Comparative fit indexes in structural models. Psychological Bulletin. 1990;107:238–246. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.107.2.238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bentler PM, Bonett DG. Significance tests and goodness of fit in the analysis of covariance structures. Psychological Bulletin. 1980;88:588–606. [Google Scholar]

- Bobova L, Finn PR, Rickert ME, Lucas J. Disinhibitory psychopathology and delay discounting in alcohol dependence: Personality and Cognitive Correlates. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmocology. 2009;17(1):51–61. doi: 10.1037/a0014503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Browne MW, Cudek R. Alternative ways of assessing model fit. In: Bollen KA, Long JS, editors. Testing structural equation models. Newbury Park, CA: Sage; 1993. pp. 136–162. [Google Scholar]

- Bucholz K, Cadoret R, Cloninger CR, Dinwiddie S, Hasselbrock V, Nurnberger J, et al. A new semistructured psychiatric interview for use in genetic linkage studies: A report of the reliability of the SSAGA. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1994;55:149–158. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1994.55.149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cantrell H, Finn PR, Rickert ME, Lucas J. Decision making in alcohol dependence: Insensitivity to future consequences and comorbid disinhibitory psychopathology. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2008;32(8):1398–1407. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2008.00714.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castellanos-Ryan N, Rubia K, Conrod PJ. Response inhibition and reward response bias mediate the predictive relationships between impulsivity and sensation seeking and the common and unique variance in conduct disorder and substance misuse. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2011;35:140–155. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2010.01331.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chassin L, Flora DB, King KM. Trajectories of alcohol and drug use from adolescence to adulthood. The effects of familial alcoholism and personality. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2004;113:483–498. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.113.4.483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chomynova P, Miller P, Beck F. Perceived risks of alcohol and illicit drug use: Relation to prevalence of use on individual and country level. Journal of Substance Use. 2009;14:250–264. [Google Scholar]

- Cloninger CR. TCI-144. Washington University: Department of Psychiatry; St. Louis, Mo: 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Cloninger CR, Pryzbeck TR, Svrakic DM, Wetzel RD. The Temperament and Character Inventory (TCI): A guide to its development and use. St. Louis, MO: Washington University, Center for the Psychobiology of Personality; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Curcio AL, George AM. Selected impulsivity facets with alcohol use/problems: The mediating role of drinking motives. Addictive Behaviors. 2011;36:959–964. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2011.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Wit H. Impulsivity as a determinant and consequence of drug use: a review of underlying processes. Addiction Biology. 2009;14:22–31. doi: 10.1111/j.1369-1600.2008.00129.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dolan M, Anderson IM. Executive and memory function and its relationship to trait impulsivity and aggression in personality disordered offenders. The Journal of Forensic Psychiatry. 2002;13(3):503–526. [Google Scholar]

- Evenden JL. Varieties of impulsivity. Psychopharmocology. 1999;146:348–361. doi: 10.1007/pl00005481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eysenck SBG, Pearson PR, Easting G, Allsop JF. Age norms for the Impulsiveness, venturesomeness, and empathy in adults. Personality and Individual Differences. 1985;6:613–619. [Google Scholar]

- Feighner JP, Robins E, Guze SB, Woodruff RA, Jr, Winokur G, Munoz R. Diagnostic Criteria for Use in Psychiatric Research. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1972;26(1):57–63. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1972.01750190059011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finn PR. Motivation, Working Memory, and Decision Making: A cognitive- motivational theory of personality vulnerability to Alcoholism. Behavioral and Cognitive Neuroscience Reviews. 2002;1(3):183–205. doi: 10.1177/1534582302001003001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finn PR, Hall J. Cognitive ability and risk for alcoholism: Short-term memory capacity and intelligence moderate personality-risk for alcohol abuse. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2004;113:569–581. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.113.4.569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finn PR, Mazas CA, Justus AN, Steinmetz J. Early-Onset Alcoholism with Conduct Disorder: Go/No Go Learning Deficits, Working Memory Capacity, and Personality. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2002;26(2):186–206. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finn PR, Rickert ME, Miller MA, Lucas J, Bogg T, Bobova L, Cantrell H. Reduced cognitive ability in alcohol dependence: Examining the role of covarying externalizing psychopathology. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2009;118(1):100–116. doi: 10.1037/a0014656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finn PR, Sharkansky EJ, Brandt KM, Turcotte N. The Effects of Familial risk, personality, and expectancies on Alcohol Use and Abuse. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2000;109(1):122–133. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.109.1.122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finn PR, Sharkansky E, Viken R, West TL, Sandy J, Bufferd G. Heterogeneity in the families of sons of alcoholics: The impact of familial vulnerability type on offspring characteristics. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1997;106:26–36. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.106.1.26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gough HG. Manual for the California Psychological Inventory. Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologists Press; 1969. [Google Scholar]

- Grekin ER, Sher KJ, Wood PK. Personality and Substance Dependence Symptoms: Modeling Substance-Specific Traits. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2006;20:415–424. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.20.4.415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gullo MJ, Ward E, Dawe S, Powell J, Jackson CJ. Support for a two-factor model of impulsivity and hazardous substance use. Journal of Personality Research. 2010;45:10–18. [Google Scholar]

- Hathaway SR, McKinley JC. Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory–2. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Hu LT, Bentler PM. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling. 1999;6:1–55. [Google Scholar]

- Iacono WG, Carlson SR, Taylor J, Elkins J, McGue M. Behavioral disinhibition and the development of substance use disorders. Development and Psychopathology. 1999;11:869–900. doi: 10.1017/s0954579499002369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Justus AN, Finn PR. Startle modulation in non-incarcerated men and women with psychopathic traits. Personality and Individual Differences. 2007;43(8):2057–2071. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2007.06.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Justus A, Finn PR, Steinmetz JE. The influence of disinhibition on the association between alcohol use and risky sexual behavior. Alcoholism: Clinical & Experimental Research. 2000;25:1457–1466. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Justus A, Finn PR, Steinmetz J. P300, disinhibited personality, and early-onset alcohol problems. Alcoholism: Clinical & Experimental Research. 2001;25:1457–1466. doi: 10.1097/00000374-200110000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kendler KS, Prescott C, Myers J, Neale MC. The structure of genetic and environmental risk factors for common psychiatric and substance use disorders in men and women. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2003;60:929–937. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.60.9.929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirby KN, Petry NM, Bickel WK. Heroin addicts have higher discount rates for delayed rewards than non-drug using controls. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General. 1999;128:78–87. doi: 10.1037//0096-3445.128.1.78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krueger RF, Caspi A, Moffit TE, Silva PA, McGee R. Personality traits are differentially linked to mental disorders: A multitrait-multidiagnosis study of an adolescent birth cohort. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1996;105:299–312. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.105.3.299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luego MA, Carrillo de la Pena MT, Ortero JM. The components of impulsiveness: A comparison of the I-7 Impulsiveness questionnaire and the Barratt Impulsivity Scale. Personality and Individual Difference. 1991;12:657–667. [Google Scholar]; Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 68:785–788. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2007.68.785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKillop J, Mattson RE, Anderson MacKillop EJ, Castelda BA, Donovick PJ. Multidimensional assessment of impulsivity in hazardous drinkers and controls. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2007;68:785–788. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2007.68.785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magid V, MacClean MG, Colder C. Differentiating between sensation seeking and impulsivity through their mediated relations with alcohol use and problems. Addictive Behaviors. 2007;32:2046–2061. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2007.01.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mâsse LC, Tremblay RE. Behavior of Boys in Kindergarten and the Onset of Substance Use During Adolescence. General Archives of Psychology. 1997;54:62–68. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1997.01830130068014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mustanski BS, Viken RJ, Kaprio J, Rose RJ. Genetic influences on the association between personality risk factors and alcohol use and abuse. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2003;112(2):282–289. doi: 10.1037/0021-843x.112.2.282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patton JH, Stanford MS, Barratt ES. Factor structure of the Barratt Impulsiveness Scale. Journal of Clinical Psychology. 1995;51:768–774. doi: 10.1002/1097-4679(199511)51:6<768::aid-jclp2270510607>3.0.co;2-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raftery AE. Bayesian model selection in social research. Sociological Methodology. 1995;25:111–163. [Google Scholar]

- Romer D, Betancourt L, Giannetta JM, Brodsky NL, Farah M, Hurt H. Executive cognitive functions and impulsivity as correlates of risk taking and problem behavior in preadolescents. Neuropsychologia. 2009;47(13):2916–2926. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2009.06.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sher KJ, Gotham HJ. Pathological alcohol involvement: A developmental disorder of young adulthood. Development and Psychopathology. 1999;11:933–956. doi: 10.1017/s0954579499002394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sher KJ, Walitzer KS, Wood PK, Brent EE. Characteristics of children of alcoholics: Putative risk factors, substance use and abuse, and psychopathology. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1991;100:427–448. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.100.4.427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slutske WS. Alcohol use disorders among US college students and their non-college- attending peers. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2005;62:321–327. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.3.321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith GT, Fischer S, Cyders MA, Annus AM, Spillane NS, McCarthy DM. On the validity and utility of discriminating among impulsivity-like traits. Assessment. 2007;14:155–170. doi: 10.1177/1073191106295527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spitzer RL, Endicott J, Robbins E. Research Diagnostic Criteria: Rationale and Reliability. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1978;35(6):773–782. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1978.01770300115013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swann AC, Bjork JM, Moeller JG, Dougherty DM. Two models of impulsivity: Relatonship to personality and psychopathology. Biological Psychiatry. 2002;51:988–994. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(01)01357-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tellegen A. Unpublished Manuscript. University of Minnesota; 1982. Brief manual of the Multi-Dimensional Personality Questionnaire. [Google Scholar]

- Tellegen A, Waller N. Unpublished manuscript. Department of Psychology, University of Minnesota; 1992. Exploring personality through test construction: development of the Multidimensional Personality Questionnaire (MPQ) [Google Scholar]

- Trasseger SL, Robinson J. The role of affective instability and UPPS impulsivity in borderline personality disorder features. Journal of Personality Disorders. 2009;23:370–383. doi: 10.1521/pedi.2009.23.4.370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whiteside SP, Lynam DR. The Five Factor Model and impulsivity: Using a structural model of personality to understand impulsivity. Personality and Individual Differences. 2001;30:669–689. [Google Scholar]

- Whiteside SP, Lynam DR. Understanding the role of impulsivity and externalizing psychopathology in alcohol abuse: application of the UPPS impulsive behavior scale. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology. 2003;11:210–217. doi: 10.1037/1064-1297.11.3.210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wills TA, Vaccaro D, McNamara G. Novelty seeking, risk taking, and related constructs as predictors of adolescent substance use: An application of Cloninger’s theory. Journal of Substance Abuse. 1994;6:1–20. doi: 10.1016/s0899-3289(94)90039-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. The ICD-10 classification of mental and behavioral disorders: Diagnostic criteria for research. Geneva: World Health Organization; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Wu LT, Pilowsky DJ, Schlenger WE, Hasin D. Alcohol use disorders and the use of treatment services among college-age young adults. Psychiatry Services. 2007;58:192–200. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.58.2.192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ziv M, Tomer R, Defrin R, Hendler T. Individual sensitivity in pain expectancy is related to differential activation of the hippocampus and amygdale. Human Brain Mapping. 2010;31:326–338. doi: 10.1002/hbm.20867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zuckerman M. Sensation seeking: Beyond the optimal level of arousal. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum; 1979. [Google Scholar]