SUMMARY

Background

Anxiety disorders are highly prevalent in elderly persons, and they are associated with functional impairment, poorer quality of life, and adverse long-term consequences such as cognitive decline. Intervention research in late-life anxiety disorders (LLAD) lags behind where it ought to be. Research in cognitive neuroscience, aging, and stress intersects in LLAD and provides the opportunity to develop innovative interventions to prevent chronic anxiety and its consequences in this age group.

Methods

This paper evaluates gaps in the evidence base for treatment of LLAD and synthesizes recent research in cognitive neuroscience, basic behavioral science, stress, and aging.

Results

We examine three intervention issues in LLAD: (1) prevention; (2) acute treatment; and (3) pre-empting adverse consequences. We propose combining randomized controlled trials (RCTs) with mechanistic biobehavioral methodologies as an optimal approach for developing novel, optimized, and personalized treatments. Additionally, we examine three barriers in the field of LLAD research: (1) How do we measure anxiety?; (2) How do we raise awareness?; (3) How will we ensure our research is applicable to underserved populations (particularly minority groups)?

Conclusions

This prospectus outlines approaches for intervention research that can reduce the morbidity of LLAD.

Keywords: anxiety, generalized anxiety disorder, elderly, neurobiology, prevention, intervention, personalized medicine, stress, aging, fMRI

INTRODUCTION

The gap

Despite data attesting to the public health importance of late-life anxiety disorders (LLAD), intervention research in this area is far behind the related fields of late-life depression and mid-life anxiety. Personalized mental health treatment is the goal, but in LLAD we have yet to glimpse even evidence-based empirical medicine.

Significant gaps (Figure 1), are:

What are the biological and basic behavioral correlates of LLAD? Given age differences in emotional processing (Gunning-Dixon et al., 2003), how do basic anxiety processes—fear conditioning and extinction, and attentional bias towards threat—interact with aging (Fox and Knight, 2005)? Resultant questions include: What biobehavioral paradigms underlie the development and maintenance of anxiety in older adults and how do they differ from young adults? What neurobiological systems are disturbed in both aging and chronic anxiety (such as HPA axis function [Lupien et al., 2007]), and what are the implications for the development or acceleration of aging-related decline in health and cognition?

What treatments have efficacy for LLAD? Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy (CBT) has some support (Stanley et al., 1996; Barraclough et al., 2001; Mohlman et al., 2003; Wetherell et al., 2003) but appears less effective than in younger adults. SSRIs (Sheikh, 2004; Lenze et al., 2005a; Schuurmans et al., 2006), dual reuptake antidepressants (Katz et al., 2002), and buspirone (Bohm et al., 1990) lack evidence in large-scale acute or maintenance studies. Benzodiazepines have the most evidence (Koepke et al., 1982, Bresolin et al., 1988), but also have potential for harm (Herings et al., 1995; Hemmelgarn et al., 1997; Hanlon et al., 1998; Pomara et al., 1998). Additionally, absent clarification of links between LLAD and its putative long-term adverse consequences (depression, cognitive decline, and health problems such as cardiovascular disease), we don’t know whether or how we can pre-empt these consequences.

How do we manage LLAD in real-world settings (e.g. primary care [Ettner and Hermann, 1997])? Although many studies have demonstrated the benefits of collaborative care in late-life depression (Frederick et al., 2007), none have examined LLAD. There is almost no research in minority populations, despite the propensity of African-Americans and Latinos for posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and panic disorder, respectively (Tolin et al., 2005; Ford et al., 2007). Also, little research has examined barriers to treatment-seeking in the elderly (e.g. anxiety knowledge and awareness, availability of services).

Figure 1.

The continuum of unanswered questions in late life anxiety disorders, from bench to bedside to community.

The opportunity

The overarching theme of this prospectus is that randomized clinical trials (RCTs) needed to address the treatment gaps could also be platforms for mechanistic biobehavioral research. Cognitive neuroscience, basic behavioral research, and stress and aging research are robust methods for developing novel, optimized, and personalized treatments for LLAD, now more than ever, for two reasons. First, research on basic behavioral processes in anxiety disorders—such as attentional bias towards threat, fear conditioning and extinction, and evaluation of ambiguous stimuli—is merging with fMRI of limbic-prefrontal-insular interactions (Bishop, 2007). Second, the fields of stress neurobiology and aging research merge in LLAD.

‘Bringing the bedside to the bench’—incorporating mechanistic studies into RCTs—has two advantages to the usual ‘bench to bedside’ approach (which considers mechanistic research and clinical trials as separate steps; i.e. discovery vs evaluation): (1) the RCT design allows for causal inference in mechanistic research, and (2) biobehavioral evaluations of mechanism can examine why treatments work and in whom. We examine three such possibilities in LLAD prevention, acute intervention, and pre-emption of long-term adverse consequences, and we outline a research strategy for each issue. We also outline barriers in LLAD research—accurate measurement, adequate awareness, and applicability to underserved populations—and potential solutions.

PROSPECTUS

Question #1: How do we prevent the onset of anxiety in late life?

Current: no studies have examined preventive interventions for LLAD

Need: personalized prevention for LLAD; i.e. novel evidence-based strategies targeted at those most likely to develop the disorder and to benefit from prevention

Anxiety commonly develops in old age, suggesting the need for LLAD prevention. Mental health prevention research is challenging, requiring an understanding of risk factors, a robust intervention at these factors, and concerns about power and ‘number needed to treat (NNT)’ (Smit et al., 2006; Reynolds et al., 2007). Yet, mental health prevention has enormous potential for public health impact (Insel and Scolnick, 2006).

Substantial data support the onset of anxiety disorders in elderly. One incidence study found onset of anxiety disorders in 11% of older women and 2% of older men (Samuelsson et al., 2005). One-third to one-half of older patients with Generalized Anxiety Disorder (GAD) develop it in later life (Blazer, 1991; Flint, 2005; Lenze et al., 2005b; Leroux et al., 2005). The incidence of agoraphobia and possibly obsessive- compulsive disorder in women may increase over the lifespan (Riedel-Heller et al., 2006). Older adults may develop PTSD and other anxiety syndromes after exposure to traumatic events less frequently than younger adults do (Acierno et al., 2006), but late-onset or delayed-onset PTSD is not uncommon (Mittal et al., 2001; Ruzich et al., 2005; Andrews et al., 2007). Substantial numbers of late-onset panic disorder cases present for medical treatment (Sheikh et al., 2004; Todaro et al., 2007).

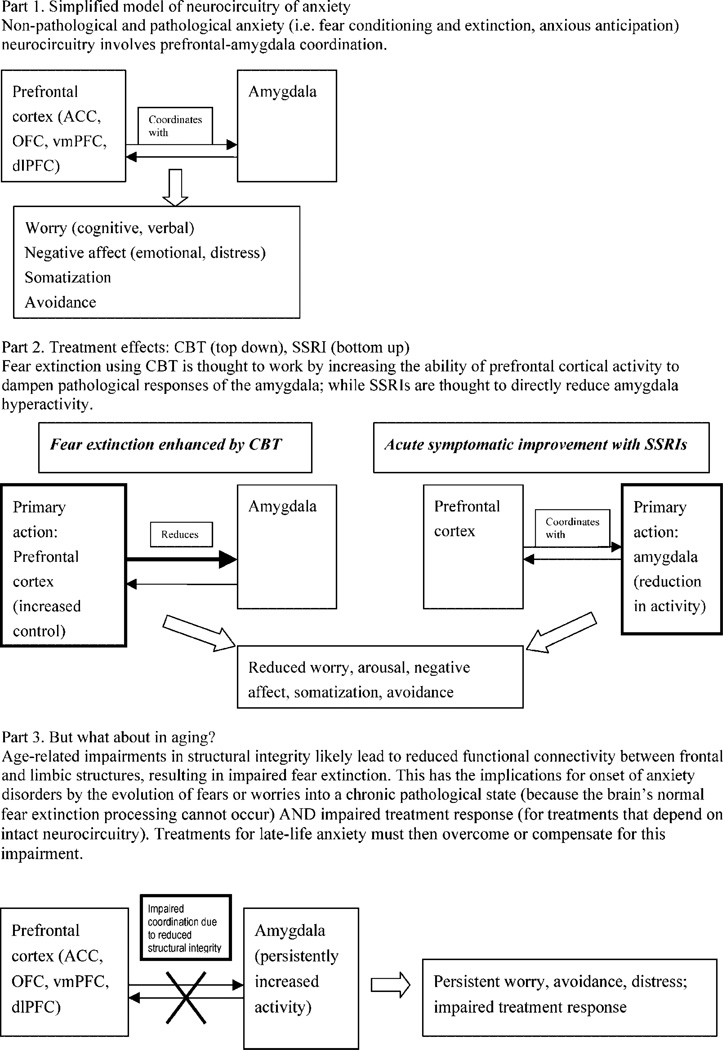

Neurobiology understands pathological anxiety as potentially resulting from a functional disconnect between amygdala (and possibly insula) and frontal areas (including anterior cingulate cortex, dorsolateral and ventromedial prefrontal cortex), impairing natural fear extinction with the result that anxiety persists and is pathological (Mathew et al., 2008). Although such research has been primarily carried out in young adults, it is likely relevant in elderly persons, in whom neurodegenerative changes may reduce connectivity. Late-onset anxiety may thus be conceptualized as a consequence of age-related changes in neurobiological pathways (e.g. corticolimbic-HPA connections [Urry et al., 2006]), not unlike evidence in late-life depression (Gunning-Dixon et al., 2008; Aizenstein et al., in press). This model is relevant for prevention but also treatment response, as described in the next section.

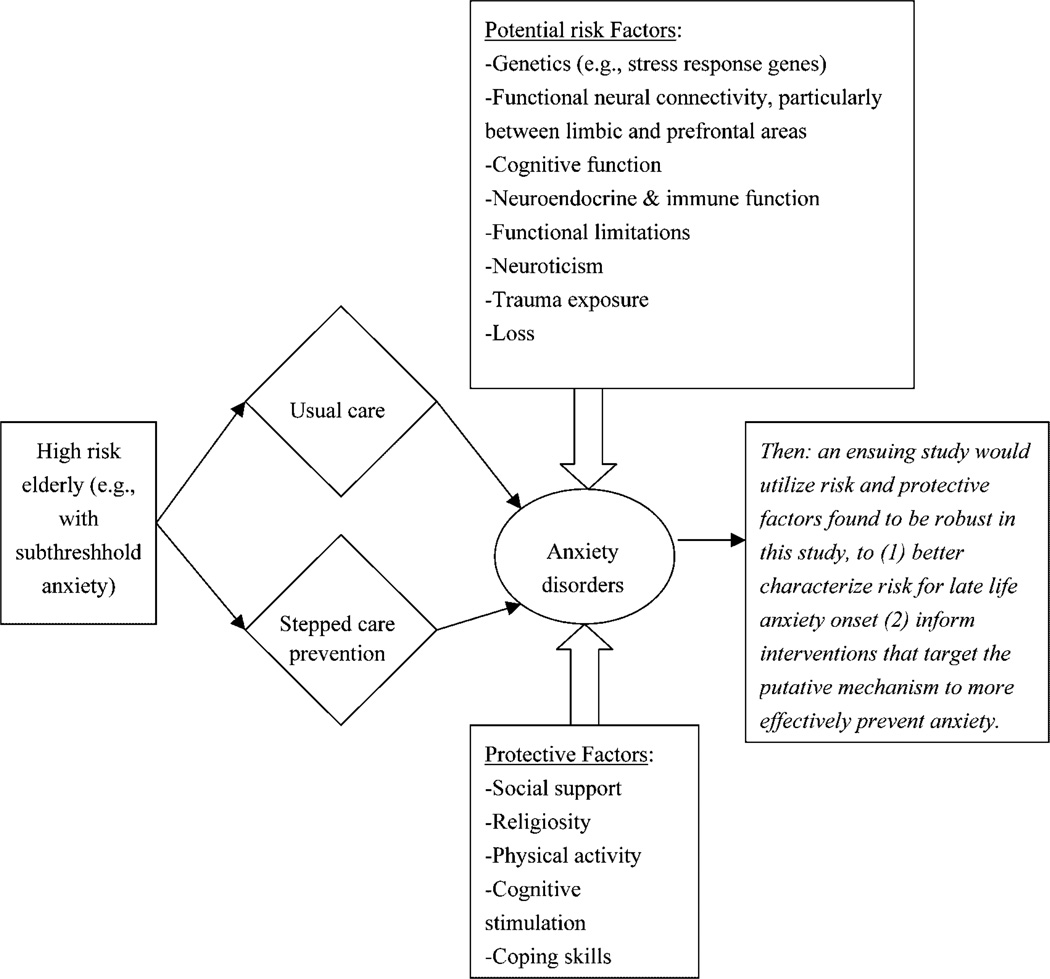

Psychosocial risk factors also play a role, uniquely for LLAD as well as shared with depression (Vink et al., 2008). One study examining shared risks for late-life depression and anxiety disorders found that virtually all risks were greater for anxiety than depression (Schoevers et al., 2003). LLAD research must also consider protective factors, including social support, religiosity, physical activity, cognitive stimulation, and effective coping skills.

Elucidation of risk and protective factors must be done in a longitudinal naturalistic study; an option, therefore, is a prevention RCT based on known risk factors (Smit et al., 2007). Subjects with these risk factors could be randomized to a preventive stepped-care approach vs usual care (van’t Veer Tazelaar et al., 2006). At the same time, this study could gather biobehavioral data and develop risk signatures—interactions among biological, psychological, and social variables associated with increased likelihood of developing chronic anxiety (Figure 2). Elucidation of such risk signatures could lead to an ensuing prevention paradigm that would be more robust in two ways: first, a greater understanding of risk would help target individuals most likely to benefit from prevention (i.e. ‘personalized prevention’, with improved NNT and cost-effectiveness); second, preventive interventions would be more robust by directly intervening at the modifiable risk.

Figure 2.

A potential design for preventive research in late-life anxiety disorders.

Question #2: How do we improve the outcomes of acute treatment?

Current: minimal evidence for any evidence-based acute treatment of LLAD

Need: novel or optimized, theory-driven, evidence-based treatments for LLAD; tailored treatments; i.e. interventions targeted at those most likely benefit

Surpsingly little is known about acute treatment of LLAD (Pinquart and Duberstein, 2007). Benzodiazepines remain the mainstay (Mamdani et al., 2005; Benitez et al., 2008) despite their adverse effects. Only two studies have prospectively examined the efficacy of SSRIs; although both demonstrated efficacy (Lenze et al., 2005a; Schuurman et al., 2006), their size and scope were too limited to clarify risk-benefit ratio.

With respect to psychotherapy, CBT is modestly effective for late-life GAD (Hofmann and Smits, 2008). With one exception (Ladouceur et al., 2004), no novel theory-driven behavioral interventions have been tested in LLAD, and little is known about the relevance of leading psychological models of GAD to this age group. Similarly, although several psychological models of GAD have been proposed—including emotional dysregulation (Mennin, 2006), interpersonal (Newman et al., 2004), experiential avoidance (Roemer and Orsillo, 2007), attention processing (Papageorgiou and Wells, 1998), and metacognitive models (Wells and King, 2006)—few have been combined with neurobiology. There is empirical support for an avoidance model of worry, in which a cortical process (worry) serves to dampen aversive autonomic responses (Borkovec and Roemer, 1995). Similarly, a model of intolerance of uncertainty (Ladouceur et al., 2004) showed promise in a small sample of older GAD patients, and neuroimaging evidence suggests a role of insular cortex activation in this behavioral process (Simmons et al., 2007). Likewise, a model based on attentional processing of threat cues has shown empirical support (Mathews and MacLeod, 2005).

A significant recent success combining neurobiology with basic behavioral theory in anxiety is d-cycloserine augmentation of exposure therapy (Davis et al., 2006), lending support for research merging fMRI paradigms related to the ‘cognitive control of affect’ circuit of frontal-limbic interactions with basic behavioral paradigms such as fear conditioning or extinction (Bishop, 2007). Pertinent to LLAD, aging is associated with reduced ability to cognitively control affective sensitivity, in part due to reduced structural connectivity (Urry et al., 2006); therefore fMRI connectivity could be combined with structural integrity measures (Aron et al., 2007; Rykhlevskaia et al., 2008). Figure 3 illustrates this implication of aging for the neurocircuitry of LLAD and their acute response to treatment, positing that disruptions in white matter tracts prevent fear extinction and lead to persistent and treatment-resistant illness. The figure is simplistic; it does not account for additional putative anxiety neurocircuitry (hippocampus, insula) or variability of the neurocircuitry between anxiety disorders; e.g. anxious apprehension, prominent in GAD, may involve different circuitry than overt fear, as in phobias or panic disorder (Mobbs et al., 2007; Mathews et al., 2008).

Figure 3.

Neurobiological models of anxiety and resultant directions for personalized late-life anxiety treatment.

If this account of neurocircuitry of illness and response is valid, research combining MRI with behavioral models could help develop novel, theory-driven acute interventions for LLAD, similar to initiatives in mid-life anxiety (Arce et al., 2007; McClure et al., 2007). This model suggests a two-step approach: (1) RCTs of existing treatments (i.e. CBT, SSRIs) as a platform for fMRI (with behavioral probes informed by psychological theories of anxiety) combined with structural MRI (to examine age-related changes in relevant structures and their connectivity) to examine the biosignature of response; (2) novel, personalized treatments (or optimized existing treatments) to bypass or compensate for the neurocircuitry implicated in treatment resistance. Some possible intervention strategies would be: (1) improving or maintaining structural integrity (perhaps using cerebrovascular protective agents similar to some ‘vascular depression’ research [Taragano et al., 2005], or neurotrophic agents); (2) compensating for impaired structural integrity by optimizing the circuit pharmacologically, such as using SSRIs (which improve functional connectivity [Anand et al., 2007] as a ‘catalyst,’ or psychotherapeutically (de Raedt, 2006); (3) directly dampening the amygdala (perhaps via cannabinoid, GABA, or serotonergic inputs [Harmer et al., 2006]); and/or (4) alternative/compensatory pathways (perhaps involving HPA axis modulators). An intriguing possibility is real-time fMRI feedback, in which the subject sees and manipulates their own fMRI signal in real time (in an understandable format, e.g. ‘thermometer’; DeCharms, 2007). Real-time fMRI feedback could be an intervention itself or a useful probe (since sham feedback provides an experimental control); however, this advance would require methodologic progress to be utilized in elderly.

Question #3: How do we pre-empt long-term adverse consequences of LLAD?

Current: no studies examining long-term management (e.g. collaborative care, maintenance treatment) or its effects on adverse outcomes

Need: optimized and personalized pre-emption, targeted at those most likely to develop long-term adverse consequences and most likely to benefit from long-term treatment

LLAD are toxic to health and cognition (Sinoff and Werner, 2003; DeLuca et al., 2005; Palmer et al., 2007). Putative mechanisms, depicted in Figure 4, include:

LLAD are associated with activation of the HPA axis leading to higher cortisol levels (Chaudieu et al., 2008; Mantella et al., 2008). Aging individuals are likely more susceptible to such elevations and their putative toxic effects (in brain and systemically), because homeostatic control is reduced (in brain and systemically). Recent research showing increases in β-amyloid-42 peptide (Aβ42) production and tau hyperphosphorylation attributable to excessive HPA activation (mediated via Corticotropin Releasing Factor-1 [CRF1]) links chronic stress, increased CRF1 production, and the pathogenic steps in Alzheimer’s disease (Csernansky et al., 2006; Green et al., 2006; Kang et al., 2007).

LLAD may lead to immune activation, similar to late-life depression (Tiemeier, 2003; Bremmer et al., 2008); evidence suggests that inflammatory and immunological consequences of stress are particularly relevant in individuals with harm-avoidant (i.e. anxious) temperament (Gerra et al., 2003).

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) is the main cause of premature mortality in mental illness (Newcomer and Hennekens, 2007), and additional mechanisms between LLAD and CVD may include insulin resistance, endothelial reactivity and impaired autonomic function (Narita et al., 2007, 2008).

Research in stress and cellular aging (Epel et al., 2004) suggests that chronic affective disorders lead, via oxidative stress, to decreased telomerase activity and telomere shrinking (Simon et al., 2006).

Finally, altering serotonin function in aging appears to affect not only stress responsivity but also longevity and age-related neurodegeneration (Sibille et al., 2007).

Figure 4.

Late life anxiety as accelerated aging: adverse consequences and treatment options.

These data demonstrate how stress research and aging research have rapidly evolved and are intersecting: accelerated aging and chronic hyperreactivity to stress are overlapping concepts. As LLAD lie at the intersection of stress and aging, agents that affect aging pathways (e.g. caloric restriction mimetics [Westphal et al., 2007], superoxide dismutase mimetics [Quick et al., 2008], CRF1 antagonists [Ising and Holsboer, 2007]) may pre-empt the adverse consequences of LLAD.

Yet despite the wealth of stress, immunology, and aging research that could be applied to elucidate these connections, there is no longitudinal mechanistic research, to our knowledge, examining consequences of LLAD. We propose that the best study would be an RCT, similar to PROSPECT and IMPACT (Unutzer et al., 2002; Bruce et al., 2004), which showed that collaborative care for late-life depression prevents or reduces myriad of adverse consequences of aging—including adverse health, disability, and mortality (Katon et al., 2005; Lin et al., 2006; Bogner et al., 2007; Gallo et al., 2007). Unfortunately, these studies lacked biomarkers necessary to determine mechanisms of pre-emption.

Therefore, a collaborative care study for LLAD (Figure 4) could also examine neuroendocrine function (Russell and Kahn, 2007), neuroimmune function (Franceschi et al., 2007), autonomic nervous system function (Carney et al., 2005), oxidative stress (Kregel and Zhang, 2007), and other cellular and systemic aging markers (e.g. telomerase activity). Using structural neuroimaging, neuropsychological measures, clinical dementia ratings, and other health measures, such a study could examine the consequences of untreated (or poorly treated) anxiety by comparing the usual care arm with the active treatment arm. The project could demonstrate the effectiveness of collaborative care for LLAD, elucidate the leading candidates for mechanisms of the adverse consequences of LLAD, and generate risk signatures of those most likely to suffer from these adverse consequences. Such a study should also include a healthy comparison group for longitudinal follow-up, as even the active treatment group is likely to suffer some adverse consequences of anxiety owing to limited efficacy of existing treatments.

The next step could be ‘personalized pre-emption’ studies that intervene, in those at highest risk, directly at the level of these mechanisms (e.g. CRF1 antagonists, antioxidants, or calorie restriction mimetics); or indirectly (e.g. dietary changes, exercise, meditation, cognitive stimulation). Many such intervention studies are ongoing but none to our knowledge that explicitly aim to pre-empt adverse consequences of anxiety.

There is a larger implication of this strategy. As research on successful vs accelerated aging is highly relevant to the LLAD field, the converse is also true: anxiety is highly relevant to research studying mechanisms of, and prevention of, the adverse consequences of aging. Measuring anxiety ought to be part of any such study, but it rarely is. Asking why is a lead-in to the next section.

BARRIERS TO PROGRESS

Despite exciting potential, several potential barriers exist in LLAD research, as outlined in Table 1.

Table 1.

Barriers to research on late-life anxiety and potential solutions

| 1. How do we measure anxiety in older adults? |

|

| 2. How do we increase awareness? |

|

| 3. How do we increase participation of diverse populations, particularly minorities? |

|

Barrier #1: How do we accurately measure anxiety in late life?

Progress in techniques generally precedes scientific advances, and in LLAD neither our diagnostic instruments nor our severity measures are adequate. This is reflected in the dramatically different prevalence and incidence estimates in LLAD epidemiologic studies (Bryant et al., 2007), with more than a ten-fold difference in overall anxiety disorder prevalence and in agoraphobia (0.6%, McCabe et al., 2006; to 7.8%, Uhlenhuth et al., 1983) and GAD (0.7%, Uhlenhuth et al., 1983; to 7.3%, Beekman et al., 1998).

Problems in diagnosing LLAD include difficulty for clinicians or patients to distinguish between adaptive and pathologic anxiety symptoms (worry, fear, or avoidance). An example is fear of falling (FOF), a common and disabling problem (Friedman et al., 2002; Zijlstra et al., 2007) which nevertheless is rarely diagnosable as an anxiety disorder. Most elderly with FOF have low risk of an injurious fall (Friedman et al., 2002; Murphy et al., 2002; Zijlstra et al., 2007), and many restrict their activities (Wilson et al., 2005) or change their gait (Chamberlin et al., 2005). Yet, few meet criteria for any anxiety disorder (Gagnon et al., 2005), likely due to lack of insight regarding the pathological nature of their anxiety.

It has been suggested that this problem represents the limitation of diagnostic categories, and the solution is dimensional assessment. Yet, current anxiety assess-mentinstruments, developed for younger adults, may be inappropriate in the elderly. First, anxiety is often rated in terms of peripheral (usually autonomic) responses: panic is largely defined by a hyperactive sympathetic response (e.g. palpitations, shortness of breath). Autonomic nervous system biology is different in older adults (De Meersman and Stein, 2007), and it may be inappropriate to use autonomic criteria from younger adults in older adults, just as normative heart-rate data from 20-year-olds would not apply to a stress test of an 80-year-old. Other problems include: older individuals may have different conceptualizations of the problem (e.g. seeing it as an immutable trait and/or a normal response to negative events), downplay or even deny symptoms asked in the usual yes/no or categorical frequency/severity format of standard assessments, use different language to describe it (e.g. ‘concerns’ rather than worry or anxiety), have difficulty remembering or identifying symptoms, misinterpret lengthy, reverse-scored, or complex items; and/or find it unnatural to assign numeric ratings to cognitive, emotional, or somatic experiences. Owing to these issues, measurement of function, and quality of life changes, important assessments of a treatment’s effectiveness (Lenze et al., 2001), will be similarly imprecise.

To address the barrier of inaccurate measurement of LLAD, as one concrete step, both the anxiety item bank in NIH PROMIS and its planned use in computer adaptive testing (Cella et al., 2007) should be validated in LLAD. Yet, the problems of diagnosis and symptom severity assessment in geriatric mental health RCTs are not necessarily solved by new symptomatic assessments (Schultz, 2008). Therefore, although patient-reported measures need to be tailored for a geriatric population (Hopko et al., 2003), we also posit inclusion of novel ways of monitoring anxiety in RCTs, including ecological momentary assessment (EMA), actigraphy, and biobehavioral markers.

EMA involves real-world (i.e. ‘ecological’) collection of real time (i.e. ‘momentary’) sampling data, typically multiple times daily using automated technology. Such measurement is already being carried out in other psychiatric disorders (e.g. Granholm et al., 2007; Axelson et al., 2003). EMA reduces reporting biases such as recency and severity effects, ‘telescoping’, and difficulties with estimation, likely improving precision of self-reports in RCTs (Moskowitz and Young, 2006).

Although past psychophysiological measures of anxiety such as skin conductance have proven disappointing, novel measures may yield better results. Actigraphy findings correlate with depression severity and have been used to evaluate depression treatment response (Raoux et al., 1994; Lamke et al., 1997; Volkers et al., 2002). Actigraphy can examine sleep, activity, and circadian rhythm, which may be substantially affected by LLAD and therefore potentially provide a complementary measure of treatment response.

Biobehavioral markers may also provide a useful provide a complementary picture to symptom reports to identify individuals at risk for anxiety, evaluate treatment response, or subtype those in whom anxiety is most likely to have long-term adverse consequences. Cortisol sampling could assess ‘stress hyperreactivity’, and functional neuroimaging could assess amygdala-prefrontal cortex interactions, as has been demonstrated in depression (Siegle et al., 2006). With respect to behavioral markers, research has shown that attention, interpretation, and memory biases underlie anxiety disorders. These behavioral markers may be a complement to symptom reports by predicting treatment response in anxiety disorders, and they may be particularly useful with older adults, given age-associated cognitive changes.

Thus, options for overcoming measurement barriers in RCTs of LLAD include increasing the precision of, and complementing, patient reports. Though presently limited by costs, burden, and infrastructure demands, these options could conceivably be simplified, automated, and therefore importable not only into RCTs but eventually into primary care and other settings as part of routine treatment, in order to implement personalized mental health treatment in the future.

Barrier #2: How do we increase awareness of late-life anxiety?

Anxiety is typically off the radar for older adults, geriatric mental health researchers, and health care providers alike and thus is a critical barrier not only for carrying out RCTs but more importantly for implementing the evidence they produce. Only one study has examined community awareness of anxiety in any age population (Edwards et al., 2007), finding that compared to depression, anxiety is regarded as less personally controllable but more amenable to treatment. Older adults are less likely than younger adults to recognize depression (Hasin and Link, 1988; Yoder et al., 1990; Highet et al., 2002; Fisher and Goldney, 2003), and it is likely that recognition of anxiety would fail to reach even this lower bar.

Some steps in understanding this barrier could be enfolded into treatment research. RCT screening could assess LLAD patients’ knowledge about anxiety. Medical records collected in RCTs could be examined to determine prior diagnosis or treatment of anxiety, informing us about provider awareness.

Moving beyond defining the problem, how can RCTs improve the ‘implementation gap’ that is a limitation of most clinical research? One way would be to consider implementation issues in the design of the RCT itself, by including treatments, assessments, and follow-up measures that are low-burden and user-friendly and thus scalable and importable to primary care and similar settings. Because RCTs utilize baseline and follow-up assessments that would be impracticable in routine care, the sharp increase in computerization and automation expected in mental health care (e.g. Farzanfar et al., 2007) should be a design element in studies developing evidence for LLAD treatment.

Beyond RCTs, large-scale awareness campaigns have improved community knowledge about depression (Paykel et al., 1998; Hegerl et al., 2003). The goal for geriatric mental health ought to be a public awareness like that achieved in Alzheimer’s disease, and LLAD need to be a part of this. Help should be solicited from NIMH and consumer organizations (including those devoted to older adults, such as AARP). Investigators are obliged to do their part.

Barrier #3: How do we increase participation of diverse populations, particularly minorities?

Our society’s elderly are increasingly ethnically diverse; without adequate representation, LLAD RCTs will not generalize to the actual population.

Low income and exposure to trauma are risk factors for LLAD (Lindesay, 1991; Vink et al., 2008), and ethnic minorities tend to have lower incomes and higher rates of trauma exposure than non-Hispanic whites. Therefore, research on LLAD in low income and minority communities should be a high priority. As LLAD research in ethnic minority or economically disadvantaged communities is at a nascent stage, studies in these populations should start with the basics and use anthropological methods such as participant-observer studies and qualitative designs to identify illness representation models (Karasz, 2005). Anxiety treatment may likewise need modification for individuals from different ethnic backgrounds or socioeconomic status, such as a greater use of family and other resources already present in the community, and the addition of case management (Arean et al., 2005).

SUMMARY AND CONCLUSION

To address LLAD intervention gaps regarding prevention, acute treatment, and pre-emption of adverse consequences, we argue for ‘bringing the bedside to the bench’—translational and clinical disciplines collaborating on RCTs that would both provide evidence for current treatments and lay the ground-work for novel, theory-driven and personalized treatments to effectively prevent and treat LLAD. We also describe the need to improve precision in RCTs and ‘bring the bedside to the community’, ensuring the relevance and implementation of RCT results. Such research can play a central role in the intersecting fields of aging and stress, developing novel and personalized interventions and benefitting aging research, psychiatry, neuroscience, and behavioral science as a whole.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This research was supported by National Institutes of Health grant numbers R01 MH070547, R34 MH080151, and K23 MH067643.

Dr Lenze has received research support from Forest Laboratories and OrthoMcNeill Neurologics. Dr Wetherell has received research support from Forest Laboratories.

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

REFERENCES

- Acierno R, Ruggiero KJ, Kilpatrick DG, et al. Risk and protective factors for psychopathology among older versus younger adults after the 2004 Florida hurricanes. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2006;14:1051–1059. doi: 10.1097/01.JGP.0000221327.97904.b0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aizenstein HJ, Butters MA, Wu M, et al. Altered functioning of the executive control circuit in late-life depression: episodic and persistent phenomena. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. doi: 10.1097/JGP.0b013e31817b60af. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anand A, Li Y, Wang Y, et al. Reciprocal effects of antidepressant treatment on activity and connectivity of the mood regulating circuit: an FMRI study. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2007;19:274–282. doi: 10.1176/appi.neuropsych.19.3.274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andrews B, Brewin CR, Philpott R, et al. Delayed-onset posttraumatic stress disorder: a systematic review of the evidence. Am J Psychiatry. 2007;164:1319–1326. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2007.06091491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arce E, Simmons AN, Lovero KL, et al. Escitalopram effects on insula and amygdale BOLD activation during emotional processing. Psychopharmacology. 2007 Dec 6; doi: 10.1007/s00213-007-1004-8. [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arean PA, Gum A, McCulloch CE, et al. Treatment of depression in low-income older adults. Psychol Aging. 2005;20:601–609. doi: 10.1037/0882-7974.20.4.601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aron AR, Behrens TE, Smith S, et al. Triangulating a cognitive control network using diffusion-weighted magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and functional MRI. J Neurosci. 2007;27:3743–3752. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0519-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Axelson DA, Bertocci MA, Lewin DS, et al. Measuring mood and complex behavior in natural environments: use of ecological momentary assessment in pediatric affective disorders. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2003;13:253–266. doi: 10.1089/104454603322572589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrowclough C, King P, Colville J, et al. A randomized trial of the effectiveness of cognitive-behavioral therapy and supportive counseling for anxiety symptoms in older adults. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2001;69:756–762. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.69.5.756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beekman AT, Bremmer MA, Deeg DJ, et al. Anxiety disorders in later life: a report from the Longitudinal Aging Study Amsterdam. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 1998;13:717–726. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1099-1166(1998100)13:10<717::aid-gps857>3.0.co;2-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benitez CI, Smith K, Vasile RG, et al. Use of benzodiazepines and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors in middle-aged and older adults with anxiety disorders: a longitudinal and prospective study. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2008;16:5–13. doi: 10.1097/JGP.0b013e31815aff5c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bishop SJ. Neurocognitive mechanisms of anxiety: an integrative account. Trends Cogn Sci. 2007;11:307–316. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2007.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blazer D, George LK, Hughes D. The epidemiology of anxiety disorders: an age comparison. In: Salzman Carl, Lebowitz Barry D., editors. Anxiety in the elderly: Treatment and research. New York, NY, US: Springer Publishing Co; 1991. pp. 17–30. 1991, xvi, 320. [Google Scholar]

- Bogner HR, Morales KH, Post EP, et al. Diabetes, depression, and death: a randomized controlled trial of a depression treatment program for older adults based in primary care (PROSPECT) Diabetes Care. 2007;30:3005–3010. doi: 10.2337/dc07-0974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bohm C, Robinson DS, Gammans RE, et al. Buspirone therapy in anxious elderly patients: a controlled clinical trial. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 1990;10:47S–51S. doi: 10.1097/00004714-199006001-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borkovec TD, Roemer L. Perceived functions of worry among generalized anxiety disorder subjects: distraction from more emotionally distressing topics? J Behav Ther Exp Psychiatry. 1995;26:25–30. doi: 10.1016/0005-7916(94)00064-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bremmer MA, Beekman AT, Deeg DJ, et al. Inflammatory markers in late-life depression: results from a population-based study. J Affect Disord. 2008;106:249–255. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2007.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bresolin N, Monza G, Scarpini E, et al. Treatment of anxiety with ketazolam in elderly patients. Clin Ther. 1988;10:536–542. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruce M, Ten Have TR, Reynolds CF, 3rd, et al. Reducing suicidal ideation and depressive symptoms in depressed older primary care patients: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2004;291:1081–1091. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.9.1081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bryant C, Jackson H, Ames D. The prevalence of anxiety in older adults: Methodological issues and a review of the literature. J Affect Disord. 2007 Dec 21; doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2007.11.008. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carney RM, Blumenthal JA, Freedland KE, et al. Low heart rate variability and the effect of depression on post-myocardial infarction mortality. Arch Intern Med. 2005;165:1486–1491. doi: 10.1001/archinte.165.13.1486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cella D, Gershon R, Lai JS, et al. The future of outcomes measurement: item banking, tailored short-forms, and computerized adaptive assessment. Qual Life Res. 2007;16(Suppl 1):133–141. doi: 10.1007/s11136-007-9204-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chamberlin ME, Fulwider BD, Sanders SL, et al. Does fear of falling influence spatial and temporal gait parameters in elderly persons beyond changes associated with normal aging? J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2005;60:1163–1167. doi: 10.1093/gerona/60.9.1163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaudieu I, Beluche I, Norton J, et al. Abnormal reactions to environmental stress in elderly persons with anxiety disorders: evidence from a population study of diurnal cortisol changes. J Affect Disord. 2008;106:307–313. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2007.07.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Csernansky JG, Dong H, Fagan AM, et al. Plasma cortisol and progression of dementia in subjects with Alzheimer-type dementia. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163:2164–2169. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.163.12.2164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis M, Reesler K, Rothbaum BO, et al. Effects of D-cycloserine on extinction: translation from preclinical to clinical work. Biol Psychiatry. 2006;60:369–375. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.03.084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- deCharms RC. Reading and controlling human brain activation using real-time functional magnetic resonance imaging. Trends Cogn Sci. 2007;11:473–481. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2007.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeLuca AK, Lenze EJ, Mulsant BH, et al. Comorbid anxiety disorder in late life depression: association with memory decline over four years. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2005;20:848–854. doi: 10.1002/gps.1366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Meersman RE, Stein PK. Vagal modulation and aging. Bio Psychol. 2007;74:165–173. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsycho.2006.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Raedt R. Does neuroscience hold promise for the further development behavior therapy? The case of emotional change after exposure in anxiety and depression. Scand J Psychol. 2006;47:225–236. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9450.2006.00511.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards S, Tinning L, Brown JS, et al. Reluctance to seek help and the perception of anxiety and depression in the United Kingdom: a pilot vignette study. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2007;195:258–261. doi: 10.1097/01.nmd.0000253781.49079.53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epel ES, Blackburn EH, Lin J, et al. Accelerated telomere shortening in response to life stress. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:17312–17315. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0407162101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ettner SL, Hermann RC. Provider specialty choice among Medicare beneficiaries treated for psychiatric disorders. Health Care Financ Rev. 1997;18:43–59. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farzanfar R, Stevens A, Vachon L, et al. Design and development of a mental health assessment and intervention system. J Med Syst. 2007;31:49–62. doi: 10.1007/s10916-006-9042-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher LJ, Goldney RD. Differences in community mental health literacy in older and younger Australians. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2003;18:33–40. doi: 10.1002/gps.769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flint AJ. Generalised anxiety disorder in elderly patients: epidemiology, diagnosis and treatment options. Drugs Aging. 2005;22:101–114. doi: 10.2165/00002512-200522020-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ford BC, Bullard KM, Taylor RJ, et al. Lifetime and 12-month prevalence of Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition disorders among older African Americans: findings from the National Survey of American Life. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2007;15:652–659. doi: 10.1097/JGP.0b013e3180437d9e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox LS, Knight BG. The effects of anxiety on attentional processes in older adults. Aging Mental Health. 2005;9:585–593. doi: 10.1080/13607860500294282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franceschi C, Capri M, Monti D, et al. Inflammaging and anti-inflammaging: a systemic perspective on aging and longevity emerged from studies in humans. Mech Ageing Dev. 2007;128:92–105. doi: 10.1016/j.mad.2006.11.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frederick JT, Steinman LE, Prohaska T, et al. Community-based treatment of late life depression an expert panel-informed literature review. Am J Prev Med. 2007;33:222–249. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2007.04.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedman SM, Munoz B, West SK, et al. Falls and fear of falling: which comes first? A longitudinal prediction model suggests strategies for primary and secondary prevention. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2002;50:1329–1335. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2002.50352.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gagnon N, Flint AJ, Naglie G, et al. Affective correlates of fear of falling in elderly persons. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2005;13:7–14. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajgp.13.1.7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallo JJ, Bogner HR, Morales KH, et al. The effect of a primary care practice-based depression intervention on mortality in older adults: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2007;146:689–698. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-146-10-200705150-00002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerra G, Monti D, Panerai AE, et al. Long-term immune-endocrine effects of bereavement: relationships with anxiety levels and mood. Psychiatry Res. 2003;121:145–158. doi: 10.1016/s0165-1781(03)00255-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Granholm E, Loh C, Swendsen J. Feasibility and Validity of Computerized Ecological Momentary Assessment in Schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 2007 Oct 10; doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbm113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green KN, Billings LM, Roozendaal B, et al. Glucocorticoids increase amyloid-beta and tau pathology in a mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. J Neurosci. 2006;26:9047–9056. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2797-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunning-Dixon FM, Hoptman MJ, Lim KO, et al. Macromolecular White Matter Abnormalities in Geriatric Depression: A Magnetization Transfer Imaging Study. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2008;16:255–262. doi: 10.1097/JGP.0b013e3181602a66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunning-Dixon FM, Gur RC, Perkins AC, et al. Age-related differences in brain activation during emotional face processing. Neurobiol Aging. 2003;24:285–295. doi: 10.1016/s0197-4580(02)00099-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanlon JT, Horner RD, Schmader KE, et al. Benzodiazepine use and cognitive function among community-dwelling elderly. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1998;64:684–692. doi: 10.1016/S0009-9236(98)90059-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harmer CJ, Mackay CE, Reid CB, et al. Antidepressant drug treatment modifies the neural processing of nonconscious threat cues. Bio Psychiatry. 2006;59:816–820. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2005.10.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasin D, Link B. Age and recognition of depression: Implications for a cohort effect in major depression. Psychol Med. 1988;18:683–688. doi: 10.1017/s0033291700008369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hegerl U, Althaus D, Stefanek J. Public attitudes towards treatment of depression: effects of an information campaign. Pharmacopsychiatry. 2003;36:288–291. doi: 10.1055/s-2003-45115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hemmelgarn B, Suissa S, Huang A, et al. Benzodiazepine use and the risk of motor vehicle crash in the elderly. JAMA. 1997;278:27–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herings RMC, Stricker BHC, deBoer A, et al. Benzodiazepines and the risk of falling leading to femur fractures. Arch Intern Med. 1995;155:1801–1807. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Highet NJ, Hickie IB, Davenport TA. Monitoring awareness of and attitudes to depression in Australia. Austral Med J. 2002;176:S63–S68. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2002.tb04506.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hofmann SG, Smits JA. Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy for Adult Anxiety Disorders: A Meta-Analysis of Randomized Placebo-Controlled Trials. J Clin Psychiatry. 2008 Mar 5;:e1–e12. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v69n0415. [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hopko DR, Stanley MA, Reas DL, et al. Assessing worry in older adults: confirmatory factor analysis of the Penn State Worry Questionnaire and psychometric properties of an abbreviated model. Psychol Assess. 2003;15:173–183. doi: 10.1037/1040-3590.15.2.173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Insel TR, Scolnick EM. Cure therapeutics and strategic prevention: raising the bar for mental health research. Mol Psychiatry. 2006;11:11–17. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4001777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ising M, Holsboer F. CRH-sub-1 receptor antagonists for the treatment of depression and anxiety. Exp Clin Psychopharmacol. 2007;15:195–528. doi: 10.1037/1064-1297.15.6.519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang JE, Cirrito JR, Dong H, et al. Acute stress increases interstitial fluid amyloid-beta via corticotrophin-releasing factor and neuronal activity. Proc Natl Aca Sci USA. 2007;104:10673–10678. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0700148104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karasz A. Cultural differences in conceptual models of depression. Soc Sci Med. 2005;60:1625–1635. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2004.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katon WJ, Schoenbaum M, Fan MY, et al. Cost-effectiveness of improving primary care treatment of late-life depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62:1313–1320. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.12.1313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katz IR, Reynolds CF, 3rd, Alexopoulos GS, et al. Venlafaxine ER as a treatment for generalized anxiety disorder in older adults: pooled analysis of five randomized placebo-controlled clinical trials. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2002;50:18–25. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2002.50003.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koepke HH, Gold RL, Linden ME, et al. Multicenter controlled study of oxazepam in anxious elderly outpatients. Psychosom. 1982;23:641–645. doi: 10.1016/S0033-3182(82)73363-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kregel KC, Zhang HJ. An integrated view of oxidative stress in aging: basic mechanisms, functional effects, and pathological considerations. Am J Physiol Regul Comp Physiol. 2007;292:R18–R36. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00327.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ladouceur R, Leger E, Dugas M, et al. Cognitive-behavioral treatment of generalized anxiety disorder (GAD0 for older adults. Int Psychogeriatr. 2004;16:195–207. doi: 10.1017/s1041610204000274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamke MR, Broderick A, Zeitelberger M, et al. Motor activity and daily variation of symptoms intensity in depressed patients. Neuropsychobiol. 1997;36:57–61. doi: 10.1159/000119362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lenze EJ, Rogers JC, Martire LM, et al. The association of late-life depression and anxiety with physical disability: a review of the literature and prospectus for future research. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2001;9:113–135. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lenze EJ, Mulsant BH, Mohlman J, et al. Generalized Anxiety Disorder in late life: lifetime course and comorbidity with Major Depressive Disorder. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2005a;13:77–80. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajgp.13.1.77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lenze EJ, Mulsant BH, Shear MK, et al. Efficacy and tolerability of citalopram in the treatment of late life anxiety disorders: Results from an eight-week, placebo-controlled trial. Am J Psychiatry. 2005b;162:146–150. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.162.1.146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LeRoux H, Gatz M, Wetherell JL. Age at onset of generalized anxiety disorder in older adults. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2005;13:23–30. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajgp.13.1.23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin EH, Tang L, Katon W, et al. Arthritis pain and disability: response to collaborative depression care. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2006;28:482–486. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2006.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindesay J. Phobic disorders in the elderly. Br J Psychiatry. 1991;159:531–541. doi: 10.1192/bjp.159.4.531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lupien SJ, Maheu F, Tu M, Fiocco A, et al. The effects of stress and stress hormones on human cognition: Implications for the field of brain and cognition. Brain Cogn. 2007;65:209–237. doi: 10.1016/j.bandc.2007.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mamdani M, Rapoport M, Shulman KI, et al. Mental health- related drug utilization among older adults: prevalence, trends, and costs. A. J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2005;13:892–900. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajgp.13.10.892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mantella RC, Butters MA, Amico JA, et al. Salivary cortisol is associated with diagnosis and severity of late-life Generalized Anxiety Disorder. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2008 doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2008.03.002. (epub). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathew SJ, Price RB, Charney DS. Recent advances in the neurobiology of anxiety disorders: implications for novel therapeutics. Am J Med Genet C Semin Med Genet. 2008;148:89–98. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.c.30172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathews A, MacLeod C. Cognitive vulnerability to emotional disorders. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. 2005;1:167–195. doi: 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.1.102803.143916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCabe L, Cairney J, Veldhuizen S, et al. Prevalence and correlates of agoraphobia in older adults. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2006;14:515–522. doi: 10.1097/01.JGP.0000203177.54242.14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McClure EB, Monk CS, Nelson EE, et al. Abnormal attention modulation of fear circuit function in pediatric generalized anxiety disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2007;64:97–106. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.64.1.97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mennin DS. Emotion regulation therapy: an integrative approach to treatment-resistant anxiety disorders. J Contemporary Psychother. 2006;36:95–105. [Google Scholar]

- Mittal D, Torres R, Abashidze A, et al. Worsening of posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms with cognitive decline: case series. J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol. 2001;14:17–20. doi: 10.1177/089198870101400105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mobbs D, Petrovic P, Marchant JL, et al. When fear is near: threat imminence elicits prefrontal-periaqueductal gray shifts in humans. Science. 2007;317:1079–1083. doi: 10.1126/science.1144298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohlman J, Gorenstein EE, Kleber M, et al. Standard and enhanced cognitive-behavior therapy for late-life generalized anxiety disorder: two pilot investigations. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2003;11:24–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moskiwitz DS, Young SN. Ecological momentary assessment: what it is and why it is a method of the future in clinical psychopharmacology. J Psychiatry Neurosci. 2006;31:13–20. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy SL, Williams CS, Gill TM. Characteristics associated with fear of falling and activity restriction in community-living older persons. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2002;50:516–520. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2002.50119.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Narita K, Murata T, Hamada T, et al. Interactions among higher trait anxiety, sympathetic activity, and endothelial function in the elderly. J Psychiatr Res. 2007;41:418–427. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2006.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Narita K, Murata T, Hamada T, et al. Associations between trait anxiety, insulin resistance, and atherosclerosis in the elderly: A pilot cross-sectional study. Psychoneuroendrocrinology. 2008 Jan 4; doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2007.11.013. [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newcomer JW, Hennekens CH. Severe mental illness and risk of cardiovascular disease. JAMA. 2007;298:1794–1796. doi: 10.1001/jama.298.15.1794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newman MG, Castonguay LG, Borkovec TD, et al. Integrative psychotherapy. In: Heimberg RG, Turk CL, Mennin DS, editors. Generalized Anxiety Disorder: Advances in Research and Practice. London: Guilford Press; 2004. pp. 320–350. [Google Scholar]

- Palmer K, Berger AK, Monastero R, et al. Predictors of progression from mild cognitive impairment to Alzheimer disease. Neurology. 2007;68:1596–1602. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000260968.92345.3f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papageorgiou C, Wells A. Effects of attention training on hypochondriasis: a brief case series. Psychol Med. 1998;28:193–200. doi: 10.1017/s0033291797005825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paykel ES, Hart D, Priest RG. Changes in public attitudes to depression during the Defeat Depression Campaign. Br J Psychiatry. 1998;173:519–522. doi: 10.1192/bjp.173.6.519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinquart M, Duberstein PR. Treatment of anxiety disorders in older adults: a meta-analytic comparison of behavioral and pharmacological interventions. Am J Geriatric Psychiatry. 2007;15:639–651. doi: 10.1097/JGP.0b013e31806841c8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pomara N, Tun H, DaSilva D, et al. The acute and chronic performance effects of alprazolam and lorazepam in the elderly: relationship to duration of treatment and self-rated sedation. Psychopharmacol Bull. 1998;34:139–153. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quick KL, Ali SS, Arch R, et al. A carboxyfullerene SOD mimetic improves cognition and extends the lifespan of mice. Neurobiol Aging. 2008;29:117–128. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2006.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raoux N, Benoit O, Dantchev N, et al. Circadian pattern of motor activity in major depressed patients undergoing antidepressant therapy: relationship between actigraphic measures and clinical course. Psychiatry Res. 1994;52:85–98. doi: 10.1016/0165-1781(94)90122-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds CF, 3rd, Dew MA, Lenze EJ, et al. Preventing depression in medical illness: a new lead? Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2007;64:884–885. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.64.8.884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riedel-Heller SG, Busse A, Angermeyer MC. The state of mental health in old-age across the ‘old’ European Union–a systematic review. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2006;113:388–401. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2005.00632.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roemer L, Orsillo SM. An open trial of an acceptance-based behavior therapy for generalized anxiety disorder. Behavior Therapy. 2007;38:72–85. doi: 10.1016/j.beth.2006.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russell SJ, Kahn CR. Endocrine regulation of ageing. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2007;8:681–691. doi: 10.1038/nrm2234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruzich MJ, Looi JC, Robertson MD. Delayed onset of posttraumatic stress disorder among male combat veterans: a case series. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2005;13:424–427. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajgp.13.5.424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rykhlevskaia E, Gratton G, Fabiani M. Combining structural and functional neuroimaging data for studying brain connectivity: a review. Psychophysiology. 2008;45:173–187. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8986.2007.00621.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samuelsson G, McCamish-Svensson C, Hagberg B, et al. Incidence and risk factors for depression and anxiety disorders: results from a 34-year longitudinal Swedish cohort study. Aging Ment Health. 2005;9:571–575. doi: 10.1080/13607860500193591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schoevers RA, Beekman AT, Deeg DJ, et al. Comorbidity and risk-patterns of depression, generalised anxiety disorder and mixed anxiety-depression in later life: results from the AMSTEL study. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2003;18:994–1001. doi: 10.1002/gps.1001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schultz SK. Moving forward in clinical trials for late-life disorders. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2008;16:1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Schuurman J, Comijs H, Emmelkamp PM, et al. A randomized, controlled trial of the effectiveness of cognitive-behavioral therapy and sertraline versus a waitlist control group for anxiety disorders in older adults. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2006;14:255–263. doi: 10.1097/01.JGP.0000196629.19634.00. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheikh JI, Lauderdale SA, Cassidy EL. Efficacy of sertraline for panic disorder in older adults: a preliminary open-label trial. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2004;12:230. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sibille E, Su J, Leman S, et al. Lack of serotonin1B receptor expression leads to age-related motor dysfunction, early onset of brain molecular aging and reduced longevity. Mol Psychiatry. 2007;12:1042–1056. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4001990. 975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siegle GJ, Carter CS, Thase ME. Use of FMRI to predict recovery from unipolar depression with cognitive behavior therapy. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163:735–738. doi: 10.1176/ajp.2006.163.4.735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simmons A, Matthews SC, Paulus MP, et al. Intolerance of uncertainty correlates with insula activation during affective ambiguity. Neurosci Lett. 2007 Nov 6; doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2007.10.030. [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simon NM, Smoller JW, McNamara KL, et al. Telomere shortening and mood disorders: preliminary support for a chronic stress model of accelerated aging. Biol Psychiatry. 2006;60:432–435. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sinoff G, Werner P. Anxiety disorder and accompanying subjective memory loss in the elderly as a predictor of future cognitive decline. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2003;18:951–959. doi: 10.1002/gps.1004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smit F, Comijs H, Schoevers R, et al. Target groups for the prevention of late-life anxiety. Br J Psychiatry. 2007;63:428–434. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.106.023127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smit F, Comijs H, Schoevers R, et al. Opportunities for cost-effective prevention of late-life depression: an epidemiological approach. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2006;63:290–296. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.63.3.290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stanley MA, Beck JG, Glassco JD. Treatment of generalized anxiety in older adults: a preliminary comparison of cognitive-behavioral and supportive approaches. Behav Ther. 1996;27:565–581. [Google Scholar]

- Taragano FE, Bagnatti P, Allegri RF. A double-blind, randomized clinical trial to assess the augmentation with nimodipine of antidepressant therapy in the treatment of ‘vascular depression’. Int Psychogeriatr. 2005;17:487–498. doi: 10.1017/s1041610205001493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tiemeier H, Hofman A, van Tuijl HR, et al. Inflammatory proteins and depression in the elderly. Epidemiology. 2003;14:103–107. doi: 10.1097/00001648-200301000-00025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Todaro JF, Shen BJ, Raffa SD, et al. Prevalence of anxiety disorders in men and women with established coronary heart disease. J Cardiopulm Rehabil Prev. 2007;27:86–91. doi: 10.1097/01.HCR.0000265036.24157.e7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tolin DF, Robinson JT, Gaztambide S, et al. Anxiety disorders in older Puerto Rican primary care patients. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2005;13:150–156. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajgp.13.2.150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uhlenhuth EH, Balter MB, Mellinger GD, et al. Symptom checklist syndromes in the general population. Correlations with psychotherapeutic drug use. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1983;40:1167–1173. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1983.01790100013001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Unutzer J, Katon W, Callahan CM, et al. Collaborative care management of late-life depression in the primary care setting: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2002;288:2836–2845. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.22.2836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Urry HL, van Reekum CM, Johnstone T, et al. Amygdala and ventromedial prefrontal cortex are inversely coupled during regulation of negative affect and predict the diurnal pattern of cortisol secretion among older adults. J Neurosci. 2006;26:4415–4425. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3215-05.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van ‘t Veer-Tazelaar N, van Marwijk H, van Oppen P, et al. Prevention of anxiety and depression in the age group of 75 years and over: a randomized controlled trial testing the feasibility and effectiveness of a generic stepped care programme among elderly community residents at high risk of developing anxiety and depression versus usual care. BMC Public Health. 2006;6:186. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-6-186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vink D, Aartsen MJ, Schoevers RA. Risk factors for anxiety and depression in the elderly: a review. J Affect Disord. 2008;106:29–44. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2007.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volkers AC, Tulen JH, Van Den Broek WW, et al. 24-Hour motor activity after treatment with imipramine or fluvoxamine in major depressive disorder. Eur Neuropsychaopharmacol. 2002;12:273–278. doi: 10.1016/s0924-977x(02)00019-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wells A, King P. Metacognitive therapy for generalized anxiety disorder: An open trial. J Behavior Ther Experiment Psychiatry. 2006;37:206–212. doi: 10.1016/j.jbtep.2005.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westphal CH, Dipp MA, Guarente L. A therapeutic role for sirtuins in diseases of aging? Trends Biochem Sci. 2007;32:555–560. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2007.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wetherell JL, Gatz M, Craske MG. Treatment of generalized anxiety disorder in older adults. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2003;71:31–40. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.71.1.31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson MM, Miller DK, Andresen EM, et al. Fear of falling and related activity restriction among middle-aged African Americans. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2005;60:355–360. doi: 10.1093/gerona/60.3.355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoder CY, Shute GE, Tryban GM. Community recognition of objective and subjective characteristics of depression. Am J Commun Psychol. 1990;18:547–566. doi: 10.1007/BF00938059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zijlstra GA, van Haastregt JC, van Eijk JT, et al. Prevalence and correlates of fear of falling, and associated avoidance of activity in the general population of community-living older people. Age Ageing. 2007;36:304–309. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afm021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]