In August, 2011, a 38-year-old man presented to his local doctor in Qingyuan, Guangdong Province, China, with generalised fatigue. He had had fever for 2 weeks, a non-productive cough, and a 5 kg weight loss. He was treated with antibiotics for 3 days, but the fever continued. He fainted twice at work, falling to the ground. He was taken to the local hospital by his coworkers. Because he admitted to having had unprotected sex with commercial sex workers, an HIV test was done. HIV ELISA was positive, and he went to the local Centre for Disease Control and Prevention clinic for a confirmatory Western blot. He continued to have nightly fevers and developed lesions on his face, trunk, and back. A week later, when the Western blot test result was returned positive, he was referred to our provincial HIV clinic in Guangzhou.

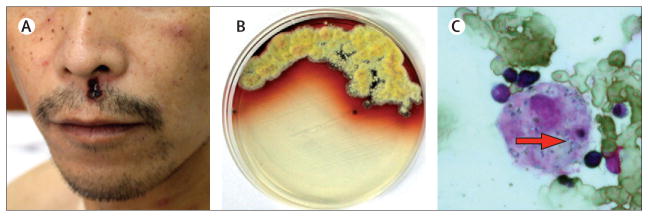

On examination, our patient had several 1 to 3 mm erythematous papules on the face, neck, trunk, and back with a single 3 cm necrotic lesion above his lips (figure A). His temperature was 40·3°C, and pulse rate was 104 beats per min. He had pale conjunctiva. There was no lymphadenopathy, and the respiratory examination was normal. He had a CD4 cell count of 10 cells per μL, white blood cell count of 5·46×109 cells per L, haematocrit of 21%, and platelet count of 26×109 cells per L. Radio graph of the chest showed no evidence of infiltrates. A diagnosis of penicilliosis with syncope due to anaemia was made. Treatment with 2 weeks of intravenous amphotericin B deoxycholate was initiated. Blood cultures at 25°C on Sabouraud dextrose agar grew fungus that produced red pigment spreading into the agar. Septated cigar-shaped yeast was seen on microscopy of a bone marrow biopsy sample (figure B). He was discharged with itraconazole, cotrimoxazole, and HIV antiretroviral therapy (ART). At last follow-up in February, 2012, he had resumed work and was asymptomatic.

Penicilliosis is a subtropical infection caused by the dimorphic fungus, Penicillium marneffei, and occurs in southeast Asia and southern China. Penicilliosis is the sixth most common cause of death in HIV patients in southern China, a region with many immigrants from other provinces and neighbouring countries.1 Common presentation is fever, malaise, and anaemia in immunocompromised patients. Pathognomonic molluscum-like papular skin lesions are found in 71% of patients and their presence assists early diagnosis.2 The fungus has been isolated in bamboo rats and soil. A correlation with the rainy season has been observed, but transmission is poorly understood. 2 weeks of amphotericin B is the recommended treatment. In HIV-positive patients ART should be started with prophylactic oral itraconazole and continued for 6 months after the CD4 cell count reaches 100 cells per μL to prevent relapse.3 Although China has improved access to HIV testing and offers ART through the Four Frees One Care policy, poor linkage between health services results in treatment delay which can further cause HIV transmission.4 HIV screening and confirmation, and initiation of ART are often implemented at administratively separate clinics, increasing the time between diagnosis and treatment. Expanding services to improve linkage and retention are crucial for preventing opportunistic infections such as penicilliosis. To reap the benefits of current advances in HIV treatment, prompt diagnosis and treatment are required. Delays between HIV screening and management reflect gaps in health systems.5 Our patient’s case underlines the importance of prompt, integrated health systems in order to prevent opportunistic infections and associated morbidity and mortality.

Figure. Penicilliosis in our patient.

(A) Necrotic lesion on upper lip; (B) blood culture showing red pigment diffusion of Penicillium marneffei; and (C) bone marrow biopsy with Wright Giemsa’s stain showing septated cigar shaped yeast inside a macrophage.

Acknowledgments

This work was funded by a research grant from the Ministry of Science and Technology, the People’s Republic of China (2012ZX10001003-003), the National Institutes of Health (NIH), and the UNC Center for AIDS Research.

Footnotes

Contributors

W-PC and L-HL looked after the patient. CW and JDT wrote the report. F-YH did the tests. Written consent to publish was obtained.

References

- 1.Wong KH, Lee SS, Lo YC, et al. Profile of opportunistic infections among HIV-1 infected people in Hong Kong. Zhonghua Yi Xue Za Zhi (Chinese Medical Journal) 1995;55:127–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Supparatpinyo K, Khamwan C, Baosoung V, Nelson KE, Sirisanthana T. Disseminated Penicillium marneffei infection in southeast Asia. Lancet. 1994;344:110–13. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(94)91287-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kaplan JE, Benson C, Holmes KH, et al. Guidelines for prevention and treatment of opportunistic infections in HIV-infected adults and adolescents: recommendations from CDC, the National Institutes of Health, and the HIV Medicine Association of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2009;58:1–2074. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhang F, Dou Z, Ma Y, et al. Five-year outcomes of the China National Free Antiretroviral Treatment Program. Ann Intern Med. 2009;151:241–51. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-151-4-200908180-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rosen S, Fox MP. Retention in HIV care between testing and treatment in sub-Saharan Africa: a systematic review. PLoS Med. 2011;8:e1001056. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]