Abstract

Aims

To ascertain the tolerability profile of single and repeated oral doses of methanesulfonyl fluoride (MSF, SNX-001) in healthy aged subjects, and to determine the degree of erythrocyte acetylcholinesterase (AChE) inhibition induced by MSF after single and repeated oral doses.

Methods

To calculate properly the kinetics and the duration of AChE inhibition, the effects of MSF were also studied in rodents. These experiments suggested that MSF administered three times per week should provide safe and efficacious AChE inhibition. In a randomized placebo-controlled phase I study, 3.6 mg, 7.2 mg or 10.8 mg MSF were then orally administered to 27 consenting healthy volunteers (aged 50 to 72 years). After a single dose phase and a 1 week wash-out period, the subjects received the same doses three times per week for 2 weeks.

Results

Twenty-two out of the 27 subjects completed the study. Four patients withdrew due to adverse events (AEs) and one for non-compliance. Erythrocyte AChE was inhibited by a total of 33%, 46%, and 62% after 2 weeks of 3.6 mg, 7.2 mg and 10.8 mg MSF, respectively. No serious AEs occurred. The most frequent AEs were headache (27%), nausea (11%) and diarrhoea (8%).

Conclusions

MSF proved to be well tolerated even with repeated oral dosing. It is estimated that MSF provided a degree of AChE inhibition that should effectively enhance memory. This molecule deserves to be tested for efficacy in a pilot randomized controlled study in patients with Alzheimer's disease.

Keywords: acetylcholinesterase, Alzheimer's disease, cholinesterase inhibition, methanesulfonyl fluoride, MSF, phase I human study

WHAT IS ALREADY KNOWN ABOUT THIS SUBJECT

Deterioration in memory and cognitive abilities in Alzheimer's disease is due, in part, to loss of cholinergic CNS neurons and a deficit of acetylcholine.

Cholinesterase inhibition is a proven therapeutic target for symptomatic treatment of memory and cognitive deficits in Alzheimer's dementia.

Despite the strong rational basis for cholinesterase therapy, the approved short acting cholinesterase inhibitors produce disappointingly modest improvements in memory, due, in part, to dose limiting peripheral toxicity (nausea, vomiting and diarrhoea).

WHAT THIS STUDY ADDS

This study of single and multiple oral doses of methanesulfonyl fluoride (MSF) provides information on the safety, pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of a potential new treatment for Alzheimer's dementia.

This study also provides a method for monitoring the dosing and safety of an irreversible inhibitor through erythrocyte acetylcholinesterase inhibition.

Unlike the approved short acting inhibitors, MSF exploits the slow de novo synthesis of acetylcholinesterase in the brain vs. peripheral tissues, introducing the next generation of cholinesterase inhibitors with reduced toxicity and heretofore unrealized potential efficacy.

Introduction

It is widely accepted that cognitive deficits in Alzheimer's disease (AD) are due, particularly as far as memory impairment is concerned, to the loss of central cholinergic neurons [1, 2]. The currently approved drugs have not fulfilled expectations, probably because of tolerability issues rather than lack of efficacy [3]. Although CNS acetylcholinesterase (AChE) inhibition may contribute to nausea and vomiting, direct cholinergic overstimulation in peripheral tissues, especially the smooth muscles of the gastrointestinal system, may be preventing adequate dosing with current drugs and thereby limiting the realization of the full benefit of cholinesterase inhibitor (ChEI) therapy. Therefore, a ChEI with exceptional CNS selectivity may produce heretofore unrealized efficacy [4].

An irreversible ChEI has the potential for exceptional selectivity for the CNS, as compared with competitive or pseudo-irreversible inhibitors because the half-time for de novo synthesis of AChE in the CNS is much longer (estimated 12 days) than in the smooth muscle of the gastrointestinal system (estimated 1 day) [5]. Therefore, by administering small doses, appropriately spaced in time (e.g. three times per week), greater AChE inhibition is accumulated and maintained in the CNS than in peripheral tissues. Secondly, such a schedule reduces direct patient exposure to the drug to a period of only several hours 3 days per week, leaving the patients essentially drug free most of the time. Exploiting the fundamental pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic advantages of an irreversible ChEI may lead to a leap forward in cholinergic therapy.

Methanesulfonyl fluoride (MSF, SNX-001) is the only truly irreversible ChEI that has been proposed for Alzheimer's therapy. Additionally, the bond between 2,2-dicholorvinyldimethyl phosphate (DDVP), the active metabolite of metrifonate, and the catalytic site of cholinesterase undergoes significant spontaneous hydrolysis, producing inhibition with a half-life of only several hours [6]. Metrifonate development was curtailed because of the appearance of muscular and respiratory paralysis, complications of organophosphate-induced delayed neuropathy [7]. It is important to note that the sulfonyl fluorides, like carbamates (e.g. rivastigmine), do not produce organophosphate-induced delayed neuropathy [8, 9] and specifically MSF, by comparison, does not inhibit the target enzyme associated with this disorder [10]. There is also no spontaneous hydrolysis of the MSF–cholinesterase bond [6].

MSF was well tolerated in a small phase I study and showed some promise as a treatment for dementia in a small double-blind, placebo-controlled, crossover phase II trial, producing 7 to 8 points improvement on the Alzheimer's disease Assessment Scale – Cognitive (ADAS-Cog) as compared with controls after 8 weeks treatment, a 20% improvement over baseline [11]. However, a continuing concern about irreversible ChEIs is safety. Therefore, the purpose of the present studies was to explore further the pharmacokinetics, pharmacodynamics and safety of MSF in animal and human studies including a double-blind randomized escalating dose phase I study in healthy aged subjects.

Methods

Animal experiments

The animal studies were reviewed and approved by Institutional Animal Care and Use Committees and conform to the PHS Guide for the Care and Use of Animals.

Pharmacodynamic study

Ten 6 month old female Sprague Dawley rats (mean weight 280 g) reared at U.T. El Paso to avoid uncontrolled exposure to pesticides were randomly divided into two groups of five. One group was injected i.p. with 0.3 mg kg−1 MSF (MTM Chemical Co., Blythewood, S.C., USA, diluted in peanut oil (USP/NF, Spectrum Chemical Mfg, Gardena, CA, USA) to 0.6 mg ml−1) and one group was injected with an equal volume of peanut oil alone three times per week for 3 weeks to simulate the proposed schedule of clinical use. At the end of the 3 weeks of treatment, the animals were sacrificed and samples of their tissues were removed, homogenized and assayed for AChE activity according to the method of Ellman et al. [12] as described in detail elsewhere [5].

Pharmacokinetic study

Male and female rats (5/sex) were dosed orally with 14C-MSF (Moravek Biochemicals, Brea, California, USA, specific activity of 2.849 × 108 Bq /mmol) in peanut oil. Blood samples (EDTA treated) were collected pre-dose and at 0.25, 0.5, 2, 4, 6, 12 and 24 h after dosing. A 200 μl aliquot of each sample was diluted in 3 ml of sterile water and counted by liquid scintillation.

Human study

The study was approved by the Ethik-Kommission der Ärztekammer Hamburg, the Bundesinstitut für Arzneimittel und Medizinprodukte (BfArM), the United States Food and Drug Administration, and registered at http://Clincialtrials.gov under protocol SNX-001-PH1-09/SCO5451.

The volunteers were healthy male and female volunteers aged > 50 years with physical and mental health confirmed by interview, medical history, physical examination, laboratory haematological tests and electrocardiogram (ECG) with body weight > 50 kg and <100 kg (body mass index between 18–30 kg m−2). Female volunteers had to be post-menopausal by at least 1 year, or surgically sterilized. Subjects needed to be capable of communicating with the investigator and giving signed informed consent.

Twenty-four subjects were initially randomized into three cohorts of eight. Six subjects in the first, second and third cohorts received 3.6 mg, 7.2 mg, or 10.8 mg MSF, respectively, and two subjects in each cohort received placebo in an ascending single dose and a multiple dose randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled design.

After receiving a single dose followed by at least a 1 week washout, the subjects received the same dose three times per week for 2 weeks (no interval more than 72 h). Subjects who dropped out for other than AEs were replaced and the replacements underwent both the single and multiple dose phases. For this reason, a larger number of subjects (n = 27) than anticipated (n = 24) made up the single dose pharmacokinetic study population. The multiple dose part of the study was completed by only 22 subjects. The 27 volunteers included in the study were 11 males and 16 females, aged 50–72 years (mean of 60.6 years), recruited and screened from a total of 82 (Table 1). The demographics of the subjects in each cohort are shown in Table 2.

Table 1.

Allocation of patients (total assessed for eligibility = 82)

| Included | 27 | Excluded | 55 |

| Cohort 1 | 8 | Did not meet criteria | 47 |

| Cohort 2 | 8 | Declined to participate | 6 |

| Cohort 3 | 8 | Other reasons | 2 |

| Replacements | 3 | m |

Table 2.

Summary of demographic data – all subjects

| Group | Gender | Race | Statistic | Age (years) | Weight (kg) | Height (cm) | BMI (kg m−2) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Placebo (n = 6) | 4 male | 6 White | Mean | 60.5 | 80.5 | 174.8 | 26.22 |

| 2 female | SD | 6.4 | 11.6 | 11.2 | 1.26 | ||

| Range | 50–68 | 65–94 | 160–186 | 25.0–28.1 | |||

| Dose 3.6 mg (n = 6) | 6 female | 6 White | Mean | 59.8 | 65.7 | 165.5 | 23.97 |

| SD | 8.0 | 6.7 | 4.2 | 2.21 | |||

| Range | 50–68 | 60–78 | 158–170 | 22.3–28.3 | |||

| Dose 7.2 mg (n = 7) | 4 male 3 female | 7 White | Mean | 60.9 | 77.9 | 173.0 | 25.97 |

| SD | 8.6 | 10.3 | 11.3 | 1.87 | |||

| Range | 50–72 | 62–92 | 159–186 | 23.8–28.9 | |||

| Dose 10.8 mg (n = 8) | 3 male 5 female | 8 White | Mean | 61.0 | 70.0 | 168.8 | 24.55 |

| SD | 6.7 | 8.3 | 9.8 | 1.63 | |||

| Range | 53–70 | 60–82 | 155–182 | 22.6–27.1 | |||

| Total (n= 27) | 11 male 16 female | 27 White | Mean | 60.6 | 73.4 | 170.5 | 25.16 |

| SD | 7.0 | 10.6 | 9.8 | 1.91 | |||

| Range | 50–72 | 60–94 | 155–186 | 22.3–28.9 |

The cohorts could not be balanced with respect to the ratio of male and female subjects due to randomizations. Both male subjects in cohort 1 (3.6 mg MSF) were randomized to receive placebo, making all the subjects receiving 3.6 mg MSF women only. Of the 27 subjects described above, 22 completed the study (see Figure 1).

| Cohort | Allocated | Drop outs | Replacements | Completed |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cohort 1 | ||||

| Placebo | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| 3.6 mg | 6 | 1 | 0 | 5 |

| Cohort 2 | ||||

| Placebo | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| 7.2 mg | 6 | 1 | 1 | 6 |

| Cohort 3 | ||||

| Placebo | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| 10.8 mg | 6 | 3 | 2 | 5 |

| Total completed | 22 |

MSF (GMP, SAFC Pharma, Manchester, U.K.) was formulated in peanut oil (Alpex Pharma SA, Mezzovico, Switzerland) and packaged in vials that were calibrated to deliver exactly 3.6 mg MSF in a 2 ml volume. The contents of one, two, or three MSF-containing vials or an equal volume of peanut oil from identical appearing vials were put into a spoon and given orally to make MSF doses of 3.6 mg, 7.2 mg or 10.8 mg or the equivalent placebo, respectively, for cohorts 1, 2 and 3.

The pharmacokinetics (PK) of MSF were calculated according to standard non-compartmental methods. The data were statistically analyzed by Scope Life Science GmbH (Hamburg, Germany) to determine area under the time curve (AUC), mean residence time (MRT), maximum concentration (Cmax), time at which Cmax occurred (tmax), relative bioavailability (Frel), half-life (t1/2), total volume of distribution (Vd/F), total clearance (CLt/F), renal clearance (CLr), cumulative amount of MSF excreted in urine (ΣXu) and maximal excretion rate in urine (dXu/dtmax). MSF in plasma and urine was determined by liquid chromatography/mass spectrometry (5.0–1000 ng ml−1 in plasma and 10.0–1000 ng ml−1 in urine).

Safety

In the single dose phase, AE questioning, vital signs, respiratory frequency and a 12-lead ECG were conducted at the time of drug administration and then at 1, 2, 4, 8, 12, 24, 36 and 48 h after drug. In the multiple dose phase, these same measurements were made at the time of drug administration on days 1, 3, 5, 8, 10 and 12 and then 4 h later on days 1, 5 and 10. On day 12 these measurements were made at the time of the last drug administration and then at 1, 2, 4, 12, 24, 36 and 48 h later. Supplemental AE questioning occurred on days 1, 5 and 10 and 4 h after MSF and in the mornings of days 2, 4, 6, 7 and day 11 (non-drug days).

Safety laboratory analyses (haematology: erythrocytes, haemoglobin, haematocrit, WBC, differential count and platelet count, coagulation: Quick's value, PTT, biochemistry: total protein, glucose, alkaline phosphatase, uric acid, creatinine, AST, ALT, γGT, sodium, potassium, α-amylase, bilirubin, LDH, lipase and urea and urinalysis: Multistix®) were conducted at the time of drug administration and then 24 h later in the single dose phase. In the multiple dose phase, they were also conducted on days 5 and 10, before drug administration. In addition to measuring erythrocyte AChE inhibition to monitor dosing, the primary safety variables were AEs, vital signs, ECG evaluation, and clinical laboratory parameters listed above for the single dose phase.

A comprehensive motor examination was also conducted each morning from the first day of the single dose phase until 2 days after the final dose of the multiple dose phase. On dosing days, the examination was conducted before the drug was administered.

Spirometry (forced expiratory volume in 1 s, FEV1) was measured before each dose of MSF during the multiple dose phase.

A final examination was conducted 7 days after the last study drug administration (day 21), including a physical examination, a 12-lead ECG, vital signs, respiratory frequency, spirometry (FEV1 and vital capacity, VC), comprehensive motor examination, AE questioning, erythrocyte AChE assay and haematology and biochemistry as for subject inclusion to determine possible changes in the subject's state of health.

Atropine was available in case of a severe reaction.

Pharmacodynamics as measured in erythrocyte AChE

Erythrocyte AChE activity was assayed by a modified spectrophotometric method of Ellman et al. [12] according to the manufacturer's instructions from finger-prick samples as an ongoing assessment of dosing and to protect the subjects (QuantiChrom® AChE assay kit, DACE-100, BioAssay Systems, Hayward, CA, USA). These samples were taken at the time of drug administration and then 4 and 24 h later in the single dose phase. In the multiple dose phase AChE was assayed at the time of drug administration on days 1, 3, 5, 8, 10 and 12 (drug days). AChE was also assayed 4 h after drug administration on days 1, 5, 10 and 12 and then again 12 and 24 h after the last dose of MSF given on day 12, the last dose in the multiple dose phase.

AChE levels for detailed pharmacodynamic (PD) analysis were also determined by the method of Ellman et al. [12] in frozen whole blood samples taken before the first dose of the multiple dose phase (day 1) and then again on day 12 before the last dose of the multiple dose phase, 4 h later and then again on day 21 (9 days after the last dose).

Statistical procedures

Descriptive statistics and regression analyses were used for pharmacokinetics, descriptive statistics and analyses of variance were used for pharmacodynamics, and descriptive statistics and frequency tables were used for safety analysis. In all cases P ≤ 0.05 (two-tailed) was required for statistical significance. Post hoc tests were conducted with the Tukey HSD. Sample sizes used were consistent with other phase I studies, not upon statistical considerations of power for comparative inference.

Results

Animal experiments

The pharmacodynamics of AChE inhibition accumulated in rat peripheral vs. CNS tissue are shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Accumulated AChE inhibition in four rat tissues: smooth muscle (ileum), skeletal muscle (pectoral), heart and brain. **Brain is more inhibited than peripheral tissues (P < 0.01) (Analysis of Variance) but peripheral tissues are not different from each other. Error bars show SEM

As expected, MSF treatment accumulated significant AChE inhibition as compared with control (F(1,8) = 212.000, P < 0.001), there were significant differences in the percent AChE inhibition in different tissues (F(3,24) = 15.910, P < 0.01), and there was a significant interaction between MSF-induced AChE inhibition and type of tissue (F(3,24) = 16.114, P < 0.01). Post hoc analyses showed that percent AChE inhibition in the brain was different from the peripheral tissues (P < 0.01) but there was no difference between peripheral tissues.

MSF produced the high level of CNS selectivity predicted by the difference between the half-times for de novo synthesis of AChE in the various tissues. These results also showed that a three times per week dosing schedule, like that used in the phase I human study, was sufficient to produce highly favourable CNS selective AChE inhibition as predicted from the unique pharmacodynamics of an irreversible inhibitor.

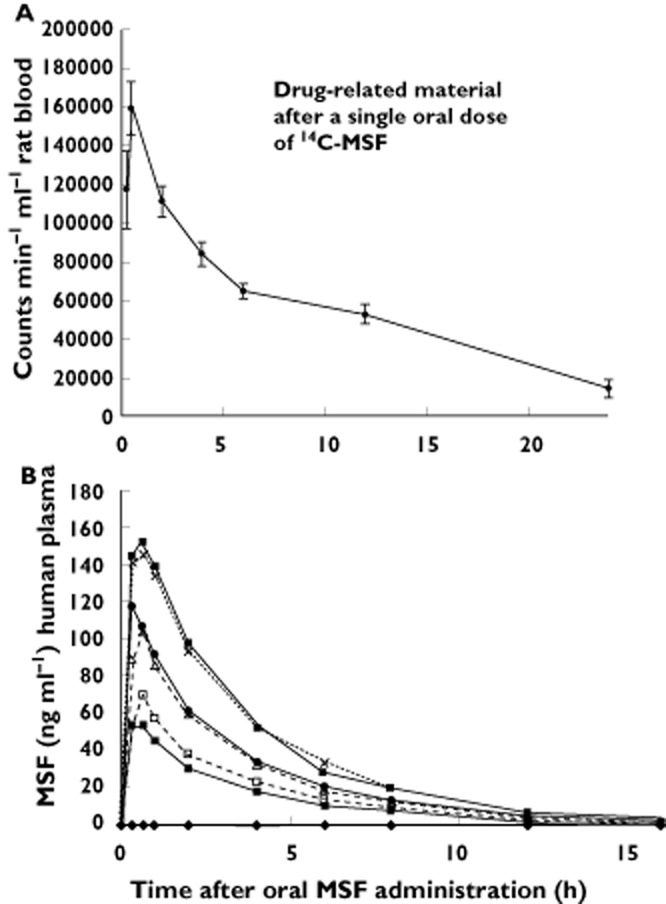

The pharmacokinetics of 14C-MSF and drug related products after a single oral dose in rats are shown in Figure 2A. The time–concentration profiles of MSF in rat blood showed maximum concentrations within 20 to 40 min after application. Thereafter the concentrations declined steadily, approaching baseline, over 24 h. There were no differences between males and females and the data were combined.

Figure 2.

Elimination of drug-related material from rat blood after a single dose (sd) of 1.0 mg kg−1 (A) or MSF from human plasma after single dose (sd) or multiple doses (md) (B). Error bars show SEM. (A)  , 1 mg kg−1 sd; (B)

, 1 mg kg−1 sd; (B)  , placebo;

, placebo;  , 3.6 mg sd;

, 3.6 mg sd;  , 7.2 mg sd;

, 7.2 mg sd;  , 10.8 mg sd;

, 10.8 mg sd;  , 3.6 mg md;

, 3.6 mg md;  , 7.2 mg md;

, 7.2 mg md;  , 10.8 ng md

, 10.8 ng md

Human study

Safety

No serious AEs were encountered in this study. In addition, there were no unexpected AEs or relevant changes in laboratory variables, cardiac, respiratory or motor function.

There were 53 AEs reported by 23 of the 27 subjects treated (MSF 18 out of 21, placebo five out of six). The number of AEs increased proportionally with the dose of MSF. The intensity of the AEs was rated as mild in 49 cases (MSF 44, placebo 5) and moderate (the highest degree of severity reached in the study) in four cases (all at the highest dose of MSF). All AEs were transient with complete recovery to normality. The most common AEs were headache, nausea, nasopharyngitis and diarrhoea (Table 3).

Table 3.

Number and percent of adverse events by organ system

| Adverse event | Placebo (n = 6) | MSF 3.6 mg (n = 6) | MSF 7.2 mg (n = 7) | MSF 10.8 mg (n = 8) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total number of AEs n = 53 | 5 (9%) | 10 (19%) | 10 (19%) | 28 (53%) |

| Cardiac | ||||

| Palpitations | 0 | 1 (2%) | 0 | 0 |

| Gastrointestinal | ||||

| Nausea | 0 | 0 | 1 (2%) | 5 (9%) |

| Diarrhoea | 1 (2%) | 0 | 1 (2%) | 2 (4%) |

| Flatulence | 0 | 1 (2%) | 1 (2%) | 0 |

| Abdominal pain | 1 (2%) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Vomiting | 0 | 0 | 1 (2%) | 0 |

| General | ||||

| Asthenia | 0 | 0 | 1 (2%) | 0 |

| Hyperhydrosis | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (2%) |

| Malaise | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (2%) |

| Infections | ||||

| Nasopharyngitis | 1 (2%) | 3 (6%) | 0 | 1 (2%) |

| Erysipelas | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (2%) |

| Investigations | ||||

| Blood amylase increased | 0 | 1 (2%) | 0 | 0 |

| Lipase increased | 0 | 1 (2%) | 0 | 0 |

| Musculoskeletal | ||||

| Back pain | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (2%) |

| Pain in extremities | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (2%) |

| Nervous system | ||||

| Headache | 2 (4%) | 2 (4%) | 3 (6%) | 7 (13%) |

| Dizziness | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (2%) |

| Psychiatric | ||||

| Abnormal dreams | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 (4%) |

| Sleep disorder | 0 | 1 (2%) | 0 | 1 (2%) |

| Agitation | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (2%) |

| Confusion | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (2%) |

| Depression | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (2%) |

| Nightmares | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (2%) |

| Respiratory | ||||

| Oropharyngeal pain | 0 | 0 | 1 (2%) | 0 |

| Vascular: | ||||

| Secondary hypertension | 0 | 0 | 1 (2%) | 0 |

Of the moderate AEs, one volunteer experienced 6 days of erysipelas beginning 9 days after the single dose of 10.8 mg MSF. The erysipelas was treated with medication and resolved completely. The other three moderate AEs were all experienced by one volunteer who had onset of intermittent depressive mood 2.5 h after 10.8 mg MSF in the single dose phase which continued for 27 days. The cessation of recurrent depressive moods on day 27 was followed 5 h later with the onset of a constant headache and intermittent confusion which lasted an additional 4 and 9 days, respectively. The headache was treated with medication but the intermittent depressive mood and confusion did not require medication. The AEs resolved completely. Neither patient experiencing the moderate AEs continued into the multidose phase.

Pharmacokinetics

The time–concentration profiles of MSF in humans were highly similar after single and multiple dose applications with maximal concentrations reached 20 to 40 min after application. Thereafter the concentrations returned rapidly below the limit of quantification (LOQ). No accumulation was observed (Figure 2B).

The total extent of exposure in terms of the area under the time curve extrapolated to infinity (AUC(0,∞)) after single dose application amounted to 255.5 ng ml−1 h, 364.1 ng ml−1 h and 590.6 ng ml−1 h (geometric means) for doses of 3.6, 7.2, and 10.8 mg MSF, respectively. These figures are similar to the AUCs within a multiple dose interval (steady-state, AUC(0,τ,ss) = 191.1 ng ml−1 h, 381.2 ng ml−1 h and 588.6 ng ml−1, respectively, for doses of 3.6, 7.2 and 10.8 mg MSF) indicating that no MSF metabolism was induced or inhibited after multiple dose application.

The dose dependency of AUC and Cmax after single and multiple dose applications were investigated by fitting the data to the power model ln AUC = alpha + beta ln(dose). The data indicated dose proportionality for AUC(0,τ,ss) (beta = 1.01 with 95% CI = 0.73, 1.31) and for Cmax,ss (beta = 0.96 with 95% CI = 0.58, 1.35) at steady state but some deviation from dose proportionality for AUC(0,∞) (beta = 0.73 with 95% CI = [0.53, 0.94] and for Cmax (beta = 0.69 with 95% CI = 0.38,1.00) in the single dose study. The direction of the deviation was lower than expected from fitting the AUC and Cmax to the power model. From the clinical point of view, the deviation from dose proportionality for the single dose study is not relevant.

Except for the lowest dose, the total clearance was independent from dose (geometric means; 3.6 mg MSF = 13.79 l h−1, 7.2 mg MSF = 19.77 l h−1 and 10.8 mg MSF = 18.29 l h−1), and similar for single and multiple dose applications (18.76 l h−1, 18.89 l h−1 and 18.35 l h−1, respectively).

After single dose application the terminal elimination half-lives with geometric means of 2.84 h, 2.63 h and 2.79 h, respectively) appeared to be independent of dose. Considering the variability, the half-life after multiple dose application also did not appear to be dose related, although the geometric means decreased with increasing doses from 3.41 h to 3.06 h to 2.72 h, respectively.

Generally, the PK variables could be determined with a high precision in spite of the small sample size. There was no major deviation from dose proportionality of the dose-related PK variables AUC and Cmax. The clearance and terminal elimination half-life did not show a dose dependency.

Urine samples for the PK profile after single dose administration were taken 0–4, 4–8, 8–12, 12–24, 24–36 and 36–48 h after the single dose. Urine samples for the PK profile after the multiple dose phase were taken on day 12 at 0–4, 4–8, 8–12, 12–24, 24–36, 36–48 h after the last dose of the multiple dose phase. MSF excretion in urine was detectable up to 8 h after doses of 3.6 mg, until 12 h after 7.2 mg, and up to 24 h after the highest dose of 10.8 mg. A definite conclusion whether MSF excretion in urine was dose dependent was not possible. It was estimated that roughly 1% was excreted in urine which was not surprising given the poor long term stability of MSF in aqueous solution [13]. The vast majority of MSF probably underwent spontaneous hydrolysis to methanesulfonic acid within a few hours at physiological pH (kw = 1 × 10−4 s−1) [13]. The absolute oral bioavailability could not be measured from the present study.

Pharmacodynamics

As expected from an irreversible inhibitor, the accumulated AChE inhibiton in erythrocytes (half-life of 45 days) after multiple administration was not proportional to dose with 33.1%, 46.5% and 62.7% after multiple doses of 3.6 mg, 7.2 mg, and 10.8 mg, respectively (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Accumulated AChE inhibition in human erythrocytes during the multiple dose phase (first 12 days) and recovery of activity to day 21. Note the small increase in AChE inhibition in the 4 h after the last MSF dose. Error bars show SEM.  , 7.2 mg;

, 7.2 mg;  , 3.6 mg;

, 3.6 mg;  , 10.8 mg;

, 10.8 mg;  , placebo

, placebo

The finger-stick method consistently showed 3–4% more AChE inhibition than obtained with the direct Ellman method but excellent overall correlation (r = +0.991).

Detailed analysis of the finger-stick samples gathered during the multiple dose phase showed a strictly proportional response to dose. Each increase of 3.6 mg in MSF dose produced a mean increment of about 6% inhibition of the remaining erythrocyte AChE activity present at the time each dose was given (6.6% ± 0.2%, 11.5% ± 1.2%, and 18.1% ± 1.5% for 3.6 mg, 7.2 mg, and 10.8 mg doses, respectively, r = +0.998).

Discussion

Figure 1 shows that an irreversible ChEI with a short pharmacokinetic half-life can have widely varying effects in different tissues, depending on the rate of de novo synthesis in each tissue. In this case, MSF produced relatively short acting biological effects in peripheral tissues, and less accumulated AChE inhibition in peripheral tissues because of rapid de novo synthesis. Long-acting biological effects were observed in the CNS, with high accumulation, because of very slow de novo synthesis. The relatively slow de novo synthesis of AChE in the brain, compared with peripheral tissues, is the key advantage of an irreversible inhibitor such as MSF in the treatment of a CNS disorder.

The PK of MSF in both humans and animals show that it is cleared from the blood rapidly and almost completely by 12 h in humans. The human data also show an orderly dose-dependent plasma concentration with no evidence of accumulation or change with repeated dosing. These data indicate that patients receiving MSF on a schedule of three doses per week would have limited direct exposure to the drug only on drug days and would be drug-free the remaining days of the week.

Although cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) may be useful in monitoring steady-state CNS AChE inhibition induced by competitive or pseudo-irreversible inhibitors, it is not suitable as a direct measure of MSF-induced CNS inhibition because the effects of an irreversible inhibitor do not depend on maintaining a steady-state concentration. Furthermore, the apparent inhibition is diluted out because of the high turnover rate of CSF. Human CSF AChE has a half-time of 2.21 (±1.22) days [14], a period too short to be useful for measuring the accumulated inhibition that accrues from an irreversible inhibitor given every 2 to 3 days. However, 80% cortex AChE inhibition has been found by cortical biopsies in monkeys (M. fasicularis) 2.5 days after the last of 2 months of repeated high doses of MSF [5], confirming a robust CNS AChE inhibition that has also been observed in rodents at more clinically relevant doses (Figure 1 and [5, 15]).

Furthermore, the finding of 80% AChE inhibition in the monkey brain 2.5 days after the last dose of MSF [5] suggests a minimum possible turnover rate of 8 days (if recovery had started from 100% inhibition). These same experiments showed that the turnover rate of monkey CSF AChE was 2.37 days, similar to that observed in humans, confirming that the turnover rate of CNS AChE is slower than CSF AChE.

A better, less invasive estimate of the CNS effect is obtained from measurements of AChE inhibition in erythrocytes if the difference in half-time for de novo synthesis in erythrocytes and brain is taken into account [11]. By modelling the timing of the doses, the percent inhibition produced by each dose, and the recovery of AChE activity from de novo synthesis between doses, reiterative computations can estimate the accumulation of AChE in the brain. They have correctly predicted the CNS accumulation of AChE inhibition in rats [15]. Based upon the above finger prick data showing that doses of 3.6 mg, 7.2 mg, and 10.8 mg produce 6.6%, 11.5%, and 18.1%, respectively, each time they are given, three times per week for 2 weeks against de novo synthesis of AChE with an estimated half-time of 12 days in the CNS, these calculations lead to an estimated accumulated AChE inhibition in the brain of 26%, 41% and 56% [16].

The highest MSF dose (10.8 mg) in the present study corresponds to the dose of 0.18 mg kg−1 (60 kg patient) used in an earlier phase II study [11] which found similar accumulated human erythrocyte AChE inhibition, adjusted for dosing for 2 months instead of 2 weeks. The AChE inhibition observed in the erythrocytes and estimated in the CNS for the highest dose in the present study seem to be at a therapeutic level insofar as similar inhibition was found in an earlier phase II trial that resulted in good clinical efficacy [11].

It should be noted that, as expected, the estimated accumulated AChE inhibition in the brain is less than that measured in the erythrocytes. This is because the erythrocytes have a longer half-time for de novo AChE synthesis (estimated 45 days, determined by the appearance of new erythrocytes) than in the CNS (estimated 12 days). Therefore, the use of erythrocyte AChE inhibition to estimate AChE inhibition in the brain requires PD calculations that take into account the shorter half-time in the brain.

In summary, it appears that the cumulative effect of MSF may be adequately monitored by erythrocyte AChE inhibition and the finger prick method offers a suitable, minimally invasive method of assessing drug action on its molecular target.

The results of the present phase I study suggest that MSF is potentially suitable as a treatment for dementia of the Alzheimer's type. The dosing schedule of three times per week seems to be desirable for practical clinical use because it minimizes direct patient exposure to the drug in the blood. Also, erythrocyte AChE inhibition in the range of 33% to 67% appears to be well tolerated and, at the high end, correlated with good efficacy [11].

As an irreversible inhibitor of AChE, MSF produces high levels of AChE inhibition in the brain by taking advantage of the very slow half-time for AChE de novo synthesis. This helps separate the therapeutic effect of MSF in the brain from the undesired peripheral cholinergic side effects that are commonly experienced with the currently available short-acting AChEIs which also may limit dosing to what can be tolerated by the patients. An irreversible AChE inhibitor such as MSF should produce more pronounced and longer lasting potentiation of central cholinergic function [17], enhanced clinical efficacy, and a fuller exploration of the real potential of AChE inhibition for the treatment of memory deficits in both vascular [18] and degenerative forms of dementia [4, 11].

Acknowledgments

Thanks to Viviana Vigil and Stephanie Quezada for assistance with the preparation of the manuscript.

Competing Interests

All authors have completed the unified Competing Interest Form at http://www.icmje.org/coi_disclosure.pdf (available on request from the corresponding author) and declare: DEM and RGF received support for the submitted work from SeneXta Therapeutics, EB and FP had ownership interest in SeneXta Therapeutics and IS and JS had no financial relationships with any organizations that might have an interest in the submitted work for the previous 3 years.

References

- 1.Bartus RT, Dean RL, 3rd, Beer B, Lippa AS. The cholinergic hypothesis of geriatric memory dysfunction. Science. 1982;217:408–414. doi: 10.1126/science.7046051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Whitehouse PB, Price DL, Struble RG, Clark AW, Coyle JT, Delong MR. Alzheimer's disease and senile dementia: loss of neurons in the basal forebrain. Science. 1982;215:1237–1239. doi: 10.1126/science.7058341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Imbimbo BP. Pharmacodynamic-tolerability relationships of cholinesterase inhibitors for Alzheimer's disease. CNS Drugs. 2001;15:375–390. doi: 10.2165/00023210-200115050-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nordgren I. Cholinesterase inhibitors – are they all the same? Int J Ger Psychopharmacol. 1998;1:176–178. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Moss DE, Kobayashi H, Pacheco G, Palacios R, Perez RG. Methanesulfonyl fluoride: a CNS selective cholinesterase inhibitor. In: Giacobini E, Becker R, editors. Current Research in Alzheimer Therapy: Cholinesterase Inhibitors. New York: Taylor and Francis; 1988. pp. 305–314. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kobayashi H, Nakano T, Moss DE, Tadahiko S. Effects of a central anticholinesterase, methanesulfonyl fluoride on the cerebral cholinergic system and behavior in mice: comparison with an organophosphate DDVP. J Health Sci. 1999;45:191–202. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lotti M, Moretto A. Organophosphate-induced delayed polyneuropathy. Toxicol Rev. 2005;24:37–49. doi: 10.2165/00139709-200524010-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Marquis JK. Contemporary Issues in Pesticide Toxicology and Pharmacology (Concepts in Toxicology, Vol. 2) Basel, New York: Karger; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Caroldi S, Lotti M, Masutti A. Intra-arterial injection of DFP or PMSF produces unilateral neuropathy or protection, respectively, in hens. Biochem Pharmacol. 1984;33:3213–3217. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(84)90079-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Osman KA, Moretto A, Lotti M. Sulfonyl fluorides and the promotion of diisopropyl flurophosphate neuropathy. Fundam Appl Toxicol. 1996;33:294–297. doi: 10.1006/faat.1996.0167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Moss DE, Berlanga P, Hagan MM, Sandoval H, Ishida C. Methanesulfonyl fluoride (MSF): a double blind, placebo controlled study of safety and efficacy in the treatment of senile dementia of the Alzheimer type. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 1999;13:20–25. doi: 10.1097/00002093-199903000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ellman GL, Courtney KD, Andres V, Jr, Featherstone RM. A new and rapid colorimetric determination of acetylcholinesterase activity. Biochem Pharmacol. 1961;7:85–95. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(61)90145-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Snow AW, Barger WR. A chemical comparison of methanesulfonyl fluoride with organofluorophosphorus ester anticholinesterase compounds. Chem Res Toxicol. 1988;1:379–384. doi: 10.1021/tx00006a009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Unni L, Vicari S, Moriearty P, Schaefer F, Becker R. The recovery of cerebrospinal fluid acetylcholinesterase activity in Alzheimer's disease patients after treatment with metrifonate. Methods Find Exp Clin Pharmacol. 2000;22:57–61. doi: 10.1358/mf.2000.22.1.795849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Malin DH, Plotner RE, Radulescu SJ, Ferebee RN, Lake JR, Negrete PG, Schaefer PJ, Crothers MK, Moss DE. Chronic methanesulfonyl fluoride enhances one-trial per day reward in aged rats. Neurobiol Aging. 1993;14:393–395. doi: 10.1016/0197-4580(93)90127-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tallarida RJ, Murray RB. Manual of Pharmacologic Calculations with Computer Programs. New York: Springer-Verlag; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Imanishi T, Hossain MM, Suzuki T, Xu P, Itaru S, Kobayashi H. Effect of a CNS-sensitive anticholinesterase methane sulfonyl fluoride on hippocampal acetylcholine release in freely moving rats. Adv Pharm Sci. 2012 doi: 10.1155/2012/708178. 2012 (Article ID708178). DOI: 10.1155/2012/708178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Borlongan CV, Sumaya I, Moss DE. Methanesulfonyl fluoride, an acetylcholinesterase inhibitor, attenuates cognitive deficits in ischemic rats. Brain Res. 2005;1038:50–58. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2005.01.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]