Abstract

Objectives:

Cone beam CT (CBCT) is used widely to depict root fracture (RF) in endodontically treated teeth. Beam hardening and other artefacts due to gutta-percha may increase the time of the diagnosis and result in an incorrect diagnosis. Two CBCT machines, ProMax® (Planmeca, Helsinki, Finland) and Master 3D® (Vatech, Hwaseong, Republic of Korea), have the option of applying an artefact reduction (AR) algorithm. The aim of this study was to determine whether using an AR algorithm in two CBCT machines enhances the accuracy of detecting RFs in endodontically treated teeth.

Methods:

66 roots were collected and decoronated. All roots were treated endodontically using the same technique with gutta-percha and zinc oxide cement. One-half of the roots were randomly selected and fractured using a nail that was tapped gently with a hammer until complete fracture resulted in two root fragments; the two root fragments were glued together with one layer of methyl methacrylate. The roots were placed randomly in eight prepared beef rib fragments.

Results:

The highest accuracy was obtained when the ProMax was used without AR. The lowest accuracy was obtained with the Master 3D when used with AR. For both machines, accuracy was significantly higher without AR than with AR. Both with and without AR, the ProMax machine was significantly more accurate than the Master 3D machine. The same rank ordering was obtained for both sensitivity and specificity.

Conclusions:

For both machines, AR decreased the accuracy of RF detection in endodontically treated teeth. The highest accuracy was obtained when using the ProMax without AR.

Keywords: cone beam computed tomography, root fracture, artefact reduction, diagnosis, endodontics

Introduction

High-density objects have been shown to cause artefacts that interfere with the diagnostic quality of CT and cone beam CT (CBCT) images.1 The examination of high-density bodies shows strong beam hardening and scattering effect artefacts that lead to images unsuitable for diagnostic purposes.2 Tissues through which X-rays pass to form dental images alter the energy spectrum of the beam; metallic objects are known to alter that energy the most.3 High-density object artefacts detected by CBCT influence the image quality by reducing the contrast, obscuring structures and impairing the detection of areas of interest, thereby making the diagnosis more difficult and time-consuming.4,5 Various methods for artefact reduction (AR) on CBCT have been proposed.6,7

Root fracture (RF) is a complication that leads often to teeth extraction.8,9 RF is usually iatrogenic and can occur after the insertion of posts or screws in a root after an endodontic treatment. Vertical compaction of the root-filling material also may induce a fracture. A common aetiology of RF is excessive occlusal force, especially in restored teeth that have undergone a root canal treatment. The teeth at highest risk for RF are endodontically treated and uncrowned posterior teeth.10 Early detection of RF may prevent extensive damage to the periodontium.9 Radiographic diagnosis of a RF is based on the presence of a radiolucent fracture line. To be able to see that line, the X-ray beam should pass directly along the fracture line, or else the RF may not be diagnosed.11

CBCT has been introduced as one of the most accurate imaging modalities for dental diagnosis purposes.12,13 In some studies, limited CBCT volumes have been shown to be more accurate in diagnosing RFs.14 CT also has been found to perform better than intraoral techniques in both in vivo15 and in vitro16 detection of RF. CBCT imaging is currently well known in the dental profession and has largely replaced conventional tomography in dental diagnostics.17 Advantages of the use of CBCT in clinical practice are easy image acquisition, more accurate images, lower radiation doses than medical CT and an enhanced cost-effectiveness.18,19

Khedmat et al20 found that the presence of gutta-percha reduced the accuracy, sensitivity and specificity of CBCT. Costa et al21 studied the accuracy of horizontal RF detection using CBCT with and without metallic posts inserted within the roots. They found that the presence of metallic posts did reduce the accuracy of RF detection. Beam hardening artefact is usually seen on CBCT images owing to gutta-percha, which is a high-density root canal filling material and may decrease the ability of RF depiction on CBCT images.

The Master 3D® machine (Vatech, Hwaseong, South Korea) and the ProMax® (Plameca, Helsinki, Finland) have an option of applying an AR algorithm. It was demonstrated that the AR algorithm in the Master 3D enhances the contrast-to-noise ratio (CNR) of the resulting images when phantoms were used; no clinical simulation was used.22,23

The primary purpose of this study was to evaluate whether using AR in two CBCT machines enhances the accuracy of detecting simulated RFs in endodontically treated teeth.

Materials and methods

66 human teeth were collected and decoronated. Root canals were prepared using the same technique and were filled with gutta-percha. 33 roots, chosen randomly, were fractured with a tapered pin inserted in the root canal and tapped gently with a hammer. The fractures caused were two vertical fracture lines in the coronal and middle thirds that went obliquely and met in the apical third; two separate fragments resulted. The fragments were repositioned and glued together with one layer of methyl methacrylate. The other 33 roots were kept intact. Eight bovine rib fragments were prepared to receive the roots. With a high-speed instrument and a bur, holes were drilled in every rib so that the roots would fit completely. Every hole was immersed with soft wax before placing each root so that the wax filled the gap between the bone and the root. Two rib fragments contained nine roots and the remainder contained eight roots.

The roots were distributed randomly to the eight bovine ribs fragments. The fragments were numbered from 1 to 8. Wax was added around the roots to keep them stable. The ribs were wrapped with three layers of wax to simulate soft tissues. Rib fragments were scanned by pairs. The AR algorithms built into the two machines were used in the present study.

Each pair was scanned with the Master 3D machine, with and without the AR option, 16×7 cm scan size with a 0.2 voxel size, and with the ProMax with and without the AR option, 8×8 cm scan size with a 0.2 voxel size. Figure 1 shows examples of images of the same root made with and without AR using both CBCT machines.

Figure 1.

Example of images of the same fractured root visualized with and without artefact reduction using both CBCT machines

Each of five observers classified each image for each modality reading detection of RFs using a five-point scale: (1) definitely absent, (2) probably absent, (3) unsure, (4) probably present and (5) definitely present. OnDemand3D™ (Cybermed, Seoul, Republic of Korea) software was used for evaluation of the scans. The whole volume was analysed. The observers were two oral and maxillofacial radiology faculty members with 21 and 8 years of experience, respectively, two oral and maxillofacial radiology residents and one endodontics resident.

At the beginning of the first session, observers were shown how RFs appear and were calibrated. The same calibrated monitor was used for all the reviews. After calibration, observers independently classified each of the images twice during two distinct viewing sessions. The sessions were separated by at least 14 days.

Statistical analyses

The kappa statistic24 was used to assess interobserver and intraobserver agreements. The area under the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve was used to assess the accuracy of assessment of the presence or absence of an RF. Sensitivity and specificity were calculated using a two-category classification constructed by considering a score of 3 or greater as positive. The area under the ROC curves, sensitivity and specificity by machine (four machines), readers (five readers) and readings (two readings for each reader) were analysed using analysis of variance.25 All calculations were carried out using the SAS statistical software v. 9.3 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC) that computes the non-parametric c-statistic that is equal to the trapezoidal area under an empirical ROC curve.

Results

Interobserver and intraobserver agreements

Interobserver agreement using the five-category classification is given, by machine, with and without use of AR, in Table 1. For the Master 3D with AR, the agreement was not significantly different from the agreement expected by change; all other kappa values indicate greater agreement than those due to chance. For both machines, interobserver agreement was significantly higher without AR than with AR. With AR, interobserver agreement using the ProMax was significantly higher than for the Master 3D; without AR, there was no significant difference between the ProMax and the Master 3D. Interobserver agreement using the two-category classification is also given in Table 1. Kappa values indicate greater agreement than those due to chance. Difference between machines and use of AR were similar to those obtained using the five-category classification, with the addition that the ProMax was significantly higher than for the Master 3D without AR.

Table 1.

Interobserver and intraobserver agreement

| Machine | Interobserver agreement |

Intraobserver agreement |

||

| Five-category scale | Two-category scale | Five-category scale | Two-category scale | |

| Kappa (95% CI) | Kappa (95% CI) | Kappa (95% CI) | Kappa (95% CI) | |

| Master 3D AR | 0.04 (−0.01–0.08) | 0.13 (0.05–0.20)a | 0.07 (0.01–0.13)a | 0.18 (0.07–0.28)a |

| Master 3D N | 0.16 (0.12–0.20)a,b | 0.24 (0.17–0.32)a,b | 0.18 (0.12–0.24)a,b | 0.32 (0.22–0.41)a |

| ProMax AR | 0.13 (0.09–0.17)a,d | 0.26 (0.19–0.34)a,d | 0.18 (0.12–0.24)a,d | 0.30 (0.20–0.39)a |

| ProMax N | 0.22 (0.18–0.26)a,c | 0.51 (0.43–0.58)a,c,e | 0.30 (0.24–0.36)a,c,e | 0.53 (0.44–0.62)a,c,e |

AR, artefact reduction; CI, confidence interval; N, no artefact reduction.

Significantly different from 0.5.

Master 3D N significantly higher than Master 3D AR.

ProMax N significantly higher than ProMax AR.

ProMax AR significantly higher than Master 3D AR.

ProMax N significantly higher than Master 3D N.

Intraobserver agreement using the five- and two-category classifications is given in Table 1. Kappa values for all four machines indicate greater agreement than that due to chance. Using the five-category classification, for both machines, intraobserver agreement was significantly higher without AR than with AR. With and without AR, intraobserver agreement using the ProMax was significantly higher than for the Master 3D. Using the two-category classification, there was no significant difference with and without AR for the Master 3D machine.

Area under the ROC curve

Areas under the ROC curve for each machine, with and without AR, are shown in Figure 2. Areas under the ROC curves were significantly higher than 0.5, indicating that both machines, with and without AR, were able to identify the presence of a RF to a degree greater than that due to chance. For both the Master 3D and ProMax machines, the areas under the ROC curves were significantly higher without AR than with AR. Both with and without AR, the areas under the ROC curves were significantly higher for the ProMax machine than for the Master 3D machine. The area under the ROC curve for the ProMax machine without AR was significantly higher than for the Master 3D machine with AR.

Figure 2.

Average area under receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve, by machine, with and without artefact reduction algorithm. Error bars represent 95% confidence intervals. Dashed reference line represents area of 0.5, i.e. classification no better than chance. a, Significantly different from 0.5; b, Master 3D N significantly higher than Master 3D AR; c, ProMax N significantly higher than ProMax AR; d, ProMax AR significantly higher than Master 3D AR; e, ProMax N significantly higher than Master 3D N. AR, artefact reduction; N, no artefact reduction

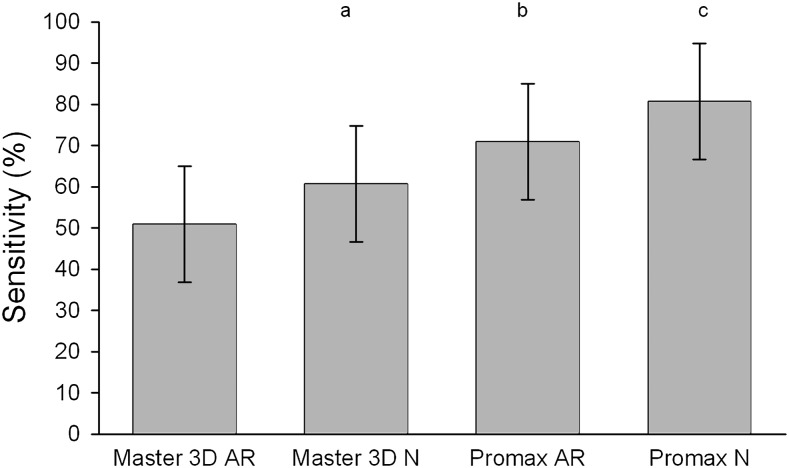

Sensitivity and specificity

Using a score of 3 or greater as indicating a positive classification, the average sensitivity for each machine, with and without AR, is shown in Figure 3. The sensitivity of the Master 3D without AR was significantly higher than for the Master 3D with AR; there was no significant difference with and without AR for the ProMax machine. Both with and without AR, the sensitivity of the ProMax machine was significantly higher than for the Master 3D machine. The sensitivity of the ProMax without AR machine was significantly greater than for the Master 3D with AR.

Figure 3.

Average sensitivity, by machine, with and without artefact reduction algorithm. Error bars represent 95% confidence intervals. a, Master 3D N significantly higher than Master 3D AR; b, ProMax AR significantly higher than Master 3D AR; c, ProMax N significantly higher than Master 3D N. AR, artefact reduction; N, no artefact reduction

The average specificity for each machine, with and without AR, is shown in Figure 4. The specificity of the ProMax machine without AR was significantly higher than for the ProMax with AR; there was no significant difference with and without AR for the Master 3D machine. The specificity of the ProMax machine without AR was higher than the specificity of the Master 3D machine without AR; there was no significant difference in specificity between the ProMax and Master 3D machines when AR was used. The specificity of the ProMax machine without AR was significantly higher than that of the Master 3D with AR.

Figure 4.

Average specificity, by machine, with and without artefact reduction algorithm. Error bars represent 95% confidence intervals. a, ProMax N significantly higher than ProMax AR; b, ProMax N significantly higher than Master 3D N. AR, artefact reduction; N, no artefact reduction

Discussion

Bechara et al22 found that the CNR, which is one of the image quality factors, was enhanced if the AR algorithm was used when acquiring scans with the Master 3D machine. In the current study, the same algorithm did not enhance the accuracy of RF detection, which suggests that the algorithm results in better appearing images without any improvement in diagnostic accuracy. The same findings were noted using the AR algorithm of the ProMax. Those results suggest that the AR algorithm may be usable with a patient who has an increased quantity of high-density material, such as metal, in their maxillofacial complex.

The high-density materials that may be used within root canals are mainly gutta-percha and metallic posts. Other materials that cause artefacts and contribute to image noise are any metallic structures that may be used for full or partial restoration of a crown. It has been shown that the presence of gutta-percha and metallic posts reduces the accuracy of RF detection.20,21

The sensitivity was the highest (lowest rate of false negatives) when the ProMax without AR was used. The ProMax with AR was more accurate and had a higher sensitivity than the results obtained with the Master 3D. The volume size used with the ProMax was 8×8 cm compared with a 16×7 cm volume used with the Master 3D. The voxel size was the same. Bechara et al26 found that a smaller field of view (FOV) using the Master 3D resulted in an enhanced CNR. The increased CNR is needed to diagnose RF, which is usually diagnosed by noting a low-density line on a high-density root. It is important to stress that the image quality will be influenced by a multitude of different factors: FOV, voxel size, signal-to-noise ratio, contrast, spatial resolution, scatter, artefacts, detector quality and reconstruction algorithms. Hassan et al27 studied the influence of scanning and reconstruction parameters on the quality of three-dimensional surface models of dental arches on CBCT. They used the Newtom 3G® CBCT (QR SLR, Verona, Italy) machine. Three volume sizes were tested: the 12 inch (30 cm) (large) FOV, the 9 inch (22.5 cm) (medium) scan FOV and the 6 inch (15 cm) (small) FOV. The authors found that the visibility of the external surfaces of the teeth in the maxilla and the interproximal space between the teeth in the anterior region in the maxilla and the mandible were better using a small volume than a big volume, with no significant differences from the midsize volume. The specificity was the highest for the results obtained when the ProMax was used without AR and the lowest resulted when the Master 3D was used with AR. The specificity represents the rate of false-negative diagnoses.

The accuracy of RF detection obtained in this paper is less than what was found by Mora et al28 and Wenzel et al.29A major factor that led to this difference was the presence of gutta-percha in the roots used in this study. It is well established that high-density structures cause artefacts on CBCT images which interfere with the diagnostic quality.30 The presence of high-density material within the imaged area causes beam hardening and streak artefacts31 and ultimately will lead to a limited diagnostic field of the images by obscuring anatomical structure, reducing the contrast between adjacent objects and impairing the detection of areas of interest.4,32 Bechara et al23 studied the Master 3D AR algorithm and found that it did not lead to regaining of the original grey value of a phantom. In addition, the algorithm altered the limit of the high-density structure.

Mahnken et al33 presented an AR approach that is a projection interpolation technique, which considers the projection data passing through the metal to be corrupted and subsequently removes it. This procedure generally markedly reduces the metal artefacts. However, all the attenuation information from high-density objects is removed as well which may cause alteration of the high-density object. The authors mentioned that applying such an approach in the maxillofacial complex may not be accurate. The ProMax AR algorithm is activated based on a threshold. Any structure denser than the threshold will be corrected. According to the results obtained in our current study and that by Bechara et al,23 the AR algorithms in both CBCT machines are not reducing the artefact accurately and are not leading to a more accurate diagnosis. In contrast, the image was altered and the accuracy decreased. The same root shown using the four modalities in Figure 1 provides a clear example. With AR, it is clear that low-density lines are added to the root, bone and wax. The image obtained using the Master 3D with AR shows how the algorithm is changing the image; a part of the periphery of the gutta-percha is missing compared with the image obtained with the Master 3D without AR.

The AR algorithms used in this project were built into the machines and cannot be modified by the user. Bechara et al22 had found that the AR available in the Master 3D increased the CNR and decrease the grey value variation. Still, these findings were not associated with an increased accuracy in detection of RFs in endodontically treated teeth. Using these AR algorithms may be beneficial when there is no need for a high contrast and spatial resolution.

More effort should be exerted by manufacturers to improve algorithms that will decrease the artefact effect and enhance the diagnostic accuracy.

Conclusion

The accuracy of RF detection in endodontically treated teeth was decreased after using the AR algorithms available in two different CBCT machines. Diagnoses obtained using the machine with the smaller FOV were more accurate.

References

- 1.Sanders MA, Hoyjberg C, Chu CB, Leggitt VL, Kim JS. Common orthodontic appliances cause artifacts that degrade the diagnostic quality of CBCT images. J Calif Dent Assoc 2007; 35: 850–857 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Draenert FG, Coppenrath E, Herzog P, Müller S, Mueller-Lisse UG. Beam hardening artefacts occur in dental implant scans with the NewTom cone beam CT but not with the dental 4-row multidetector CT. Dentomaxillofac Radiol 2007; 36: 198–203 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Webber RL, Tzukert A, Ruttimann U. The effects of beam hardening on digital subtraction radiography. J Periodontal Res 1989; 24: 53–58 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Barrett JF, Keat N. Artifacts in CT: recognition and avoidance. Radiographics 2004; 24: 1679–1691 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vande Berg B, Malghem J, Maldague B, Lecouvet F. Multi-detector CT imaging in the postoperative orthopedic patient with metal hardware. Eur J Radiol 2006; 60: 470–479 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Robertson DD, Weiss PJ, Fishman EK, Magid D, Walker PS. Evaluation of CT techniques for reducing artifacts in the presence of metallic orthopedic implants. J Comput Assist Tomogr 1988; 12: 236–241 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kalender WA, Hebel R, Ebersberger J. Reduction of CT artifacts caused by metallic implants. Radiology 1987; 164: 576–577 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shemesh H, van Soest G, Wu MK, Wesselink PR. Diagnosis of vertical root fractures with optical coherence tomography. J Endod 2008; 34: 739–742 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tamse A, Kaffe I, Lustig J, Ganor Y, Fuss Z. Radiographic features of vertically fractured endodontically treated mesial roots of mandibular molars. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod 2006; 101: 797–802 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lam EWN. Trauma to teeth and facial structures. In: White SC, Pharoah MJ. eds. Oral radiology. Principles and interpretation. 2009. 6th edn St. Louis, MO: Mosby; 542–548 [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tsesis I, Kamburoğlu K, Katz A, Tamse A, Kaffe I, Kfir A. Comparison of digital with conventional radiography in detection of vertical root fractures in endodontically treated maxillary premolars: an ex vivo study. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod 2008; 106: 124–128 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ghaeminia H, Meijer GJ, Soehardi A, Borstlap WA, Mulder J, Bergé SJ. Position of the impacted third molar in relation to the mandibular canal. Diagnostic accuracy of cone beam computed tomography compared with panoramic radiography. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2009; 38: 964–971 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chen Q, Liu DG, Zhang G, Ma XC. Relationship between the impacted mandibular third molar and the mandibular canal on panoramic radiograph and cone beam computed tomography. Zhonghua Kou Qiang Yi Xue Za Zhi 2009; 44: 217–221 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Iikubo M, Kobayashi K, Mishima A, Shimoda S, DaiARuya T, Igarashi C, et al. Accuracy of intraoral radiography, multidetector helical CT, and limited cone-beam CT for the detection of horizontal tooth root fracture. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod 2009; 108: e70–e74 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Youssefzadeh S, Gahleitner A, Dorffner R, Bernhart T, Kainberger FM. Dental vertical root fractures: value of CT in detection. Radiology 1999; 210: 545–549 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hannig C, Dullin C, Hulsmann M, Heidrich G. Three-dimensional, non-destructive visualization of vertical root fractures using flat panel volume detector computer tomography: an ex vivo in vitro case report. Int Endod J 2005; 38: 904–913 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.White SC. Cone-beam imaging in dentistry. Health Phys 2008; 95: 628–637 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Scarfe WC, Farman AG, Sukovic P. Clinical applications of cone-beam computed tomography in dental practice. J Can Dent Assoc 2006; 72: 75–80 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Scarfe WC, Farman AG. What is cone-beam CT and how does it work? Dent Clin North Am 2008; 52: 707–730 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Khedmat S, Rouhi N, Drage N, Shokouhinejad N, Nekoofar MH. Evaluation of three imaging techniques for the detection of vertical root fractures in the absence and presence of gutta-percha root fillings. Int Endod J 2012; 45: 1004–1009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Costa FF, Gaia BF, Umetsubo OS, Cavalcanti MG. Detection of horizontal root fracture with small-volume cone-beam computed tomography in the presence and absence of intracanal metallic post. J Endod. 2011; 37: 1456–1459 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bechara BB, Moore WS, McMahan CA, Noujeim M. Metal artefact reduction with cone beam CT: an in vitro study. Dentomaxillofac Radiol 2012; 41: 248–253 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bechara B, McMahan C, Geha H, Noujeim M. Evaluation of a cone beam CT artefact reduction algorithm. Dentomaxillofac Radiol 2012; 41: 422–428 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fleiss JL, Levin B, Paik MC. Statistical methods for rates and proportions. 2003. 3rd edn. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons; [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhou XH, Obuchowski NA, McClish DK. Statistical methods in diagnostic medicine. 2002. New York, NY: John Wiley & Sons; [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bechara B, McMahan CA, Moore WS, Noujeim M, Geha H. Contrast-to-noise-ratio with different large volumes in a cone-beam computerized tomography machine: an in vitro study. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol 2012; 114: 658–665 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hassan B, Couto Souza P, Jacobs R, de Azambuja Berti S, van der Stelt P. Influence of scanning and reconstruction parameters on quality of three-dimensional surface models of the dental arches from cone beam computed tomography. Clin Oral Investig 2010; 14: 303–310 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mora MA, Mol A, Tyndall DA, Rivera EM. In vitro assessment of local computed tomography for the detection of longitudinal tooth fractures. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod 2007; 103: 825–829 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wenzel A, Haiter-Neto F, Frydenberg M, Kirkevang LL. Variable-resolution cone-beam computerized tomography with enhancement filtration compared with intraoral photostimulable phosphor radiography in detection of transverse root fractures in an in vitro model. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod 2009; 108: 939–945 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sanders MA, Hoyjberg C, Chu CB, Leggitt VL, Kim JS. Common orthodontic appliances cause artifacts that degrade the diagnostic quality of CBCT images. J Calif Dent Assoc 2007; 35: 850–857 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Draenert FG, Coppenrath E, Herzog P, Müller S, Mueller-Lisse UG. Beam hardening artefacts occur in dental implant scans with the NewTom cone beam CT but not with the dental 4-row multidetector CT. Dentomaxillofac Radiol 2007; 36: 198–203 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Webber RL, Tzukert A, Ruttimann U. The effects of beam hardening on digital subtraction radiography. J Periodontal Res 1989; 24: 53–58 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mahnken AH, Raupach R, Wildberger JE, Jung B, Heussen N, Flohr TG, et al. A new algorithm for metal artifact reduction in computed tomography: in vitro and in vivo evaluation after total hip replacement. Invest Radiol 2003; 38: 769–775 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]