Abstract

Lonely older adults have increased expression of pro-inflammatory genes as well as increased risk for morbidity and mortality. Previous behavioral treatments have attempted to reduce loneliness and its concomitant health risks, but have had limited success. The present study tested whether the 8-week Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction (MBSR) program (compared to a Wait-List control group) reduces loneliness and downregulates loneliness-related pro-inflammatory gene expression in older adults (N=40). Consistent with study predictions, mixed effect linear models indicated that the MBSR program reduced loneliness, compared to small increases in loneliness in the control group (treatment condition × time interaction: F(1,35)=7.86, p=.008). Moreover, at baseline, there was an association between reported loneliness and upregulated pro-inflammatory NF-κB-related gene expression in circulating leukocytes, and MBSR downregulated this NF-κB-associated gene expression profile at post-treatment. Finally, there was a trend for MBSR to reduce C Reactive Protein (treatment condition × time interaction: (F(1,33)=3.39, p=.075). This work provides an initial indication that MBSR may be a novel treatment approach for reducing loneliness and related pro-inflammatory gene expression in older adults.

Keywords: meditation, mindfulness, older adults, aging, loneliness, genetics, gene expression, stress

“Usually we regard loneliness as an enemy. Heartache is not something we choose to invite in. It's restless and pregnant and hot with the desire to escape and find something or someone to keep us company. When we can rest in the middle [through meditation practice], we begin to have a nonthreatening relationship with loneliness, a relaxing and cooling loneliness that completely turns our usual fearful patterns upside down”

-- Pema Chodron (2000), Buddhist nun and teacher

Feeling lonely is a significant risk factor for morbidity and mortality in older adults. For example, lonely older adults have increased risk for cardiovascular disease (Olsen et al., 1991; Thurston and Kubzansky, 2009), Alzheimer's disease (Wilson et al., 2007), and all-cause mortality (Tilvis et al., 2011). Developing effective treatments to reduce loneliness in older adults is thus essential, but previous treatment efforts have had limited success (Findlay, 2003; Masi et al., 2011). As Pema Chodron suggests above, meditation practice may provide a middle way for reducing one's feelings of loneliness (Chodron, 2000). Loneliness has been described as a state of social distress that arises when there is a discrepancy between one's desired and actual social relationships (Russell et al., 1980; Cacioppo and Hawkley, 2009). Previous mindfulness meditation studies using the standardized 8-week Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction (MBSR) program show that MBSR reduces measures of distress and negative affect in healthy and patient populations (for reviews, Brown et al., 2007; Hölzel et al., 2011) and can improve social relationship functioning in couples (Carson et al., 2004), although no studies have tested whether the MBSR program can reduce loneliness. Our primary aim was thus to test whether MBSR reduces loneliness in a small randomized controlled trial in older adults (N=40).

If the MBSR program reduces loneliness, it offers the intriguing possibility that mindfulness meditation training may also alter gene expression dynamics and protein markers of inflammation (i.e., C Reactive Protein (CRP) and Interleukin-6 (IL-6)) that are implicated in the physical health risks observed in lonely older adults (Cole et al., 2007). Several studies indicate that MBSR may reduce protein biomarkers of inflammation (Carlson et al., 2003, 2007; Lengacher et al., 2012), and inflammation is known to play a major role in structuring the development and progression of many diseases that drive late-life morbidity and mortality (Finch, 2007). Moreover, recent research shows that immune cells from lonely older adults have increased expression of genes involved in inflammation (Cole et al., 2007, 2011). Bioinformatic analyses of the signaling pathways regulating gene expression suggest that loneliness may activate a biological defensive program mediated by the pro-inflammatory transcription factor, NF-κB, in monocytes (Cole et al., 2007, 2011; Irwin and Cole, 2011; Antoni et al., 2012). Therefore we also tested whether MBSR reduces loneliness-related pro-inflammatory gene expression and circulating protein biomarkers of inflammation (as measured by CRP and IL-6).

Methods

Participants

Randomized participants (N=40) were healthy older adults (age 55-85 years; M= 65 SD= 7) recruited via newspaper advertisements from the Los Angeles area, who indicated an interest in learning mindfulness meditation techniques (a self-selected group). The sample was 64% Caucasian, 12% African American, 10% Latino, 7% Asian American, and 5% Other, and was predominantly female (33 women). The trial occurred during October 2007-January 2008. All participants provided written informed consent at the study screening. All study procedures were approved by the UCLA and CMU Institutional Review Boards.

Procedure

To determine eligibility, interested participants were phone screened and invited for an in-person evaluation. To qualify for the study, participants had to be English-speaking, not currently practicing any mind-body therapies more than once per week (e.g., meditation, yoga), non-smokers, mentally and physically healthy for the last three months, and not currently taking medications that affect immune, cardiovascular, endocrine, or psychiatric functioning. Participants also completed fMRI tasks (described in a separate report), and additional MRI criteria excluded participants at screening if they were left handed, had any non-removable metal (dental fillings okay) or non-MRI safety approved implants, or weighed more than 300lbs. Participants were also excluded if they had cognitive impairment (<23 on the Mini-Mental State Examination) (Folstein, 1975). Participants were compensated up to $200 for participating in this study (part of this compensation was for the fMRI-related study activities).

If participants were eligible, they were asked to complete a number of study measures, which included a questionnaire assessing loneliness and a blood sample (see Measures). Participants were then randomized to either the 8-week Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction (MBSR) program or a Wait-List (WL) control condition using a computerized number generator. MBSR is a standardized and manualized 8-week mindfulness meditation intervention (Kabat-Zinn, 1990) that has been used widely in behavioral medicine research. MBSR was administerd by one of three trained clinicians over three cohorts, and consisted of eight weekly 120-minute group sessions, a day-long retreat in the sixth or seventh week, and 30-minutes of daily home mindfulness practice. Our trained clinicians had co-taught previous MBSR programs together and all maintained a daily mindfulness meditation practice. During each group session, an instructor lead participants in guided mindfulness meditation exercises, mindful yoga and stretching, and group discussions with the intent to foster mindful awareness of one's moment-to-moment experience. The daylong seven-hour retreat during week six or seven of the MBSR intervention focused on integrating and elaborating on the exercises learned during the course. Finally, MBSR participants were asked to participate in 30 minutes of daily home mindfulness practice six days a week during the program. After the 8-week period, all participants returned to complete the same measures as those administered at baseline, including the loneliness questionnaire and another blood sample by blinded study staff. Participants in the WL condition were asked not to participate in any new behavioral health programs during the waiting-period and received the MBSR program after completing the primary dependent measures in the study.

Measures and Data Analytic Approach

MBSR class attendance was recorded by a hypothesis-blind staff member, and participants were asked to complete daily home practice logs indicating how many minutes they practiced each day during the 8-week MBSR program.

Mindfulness Skills

The 39-item Kentucky Inventory of Mindfulness Skills (KIMS) was administered at baseline and post-treatment as a manipulation check, to assess whether MBSR program increases self-reported use of mindfulness skills (anchored by 0= Never True to 5=Always True) (Baer et al., 2004). These skills include observing one's experience (sample item: “I notice when my moods begin to change”; baseline study α=.86), describing (sample item: “I'm good at finding words to describe my feelings”; baseline study α=.87), acting with awareness (sample item: “When I do things, my mind wanders and I am easily distracted (reverse-scored)”; baseline study α=.80), and acceptance (sample item: “I tell myself I shouldn't be feeling the way I'm feeling (reverse-scored) (baseline study α=.85). A composite measure of mindfulness skills was created by summing all items, and higher scores indicate greater mindfulness.

Loneliness

The composite UCLA-R Loneliness Scale (Russell et al., 1980) was administered at baseline and post-treatment, and consists of 20 items measuring general feelings of loneliness (sample item: “I lack companionship”; anchored 1(never) to 4 (often); baseline study α=.92). Higher scores indicate greater loneliness.

Following intent-to-treat principles, mixed effect linear models (MLMs) tested for treatment condition (MBSR vs WL) × time (baseline vs. post-treatment) interactions on mindfulness skills and loneliness using SPSS 19.0 (IBM, Armonk, New York). Treatment Condition and Time were modeled as fixed effects.

Gene Expression Profiling and Pro-Inflammatory Protein Analysis

Participants provided 10ml of blood at baseline and post-treatment. Genome-wide transcriptional profiling was carried out as previously described (Cole et al., 2010, 2011). Briefly, peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) were isolated by density gradient centrifugation and total RNA was extracted (RNeasy; Qiagen, Valencia CA), tested for suitable mass (Nanodrop ND1000) and integrity (Agilent Bioanalyzer), and converted to fluorescent cRNA for hybridization to human HT-12 BeadChips (Illumina, San Diego CA) following the manufacturer's standard protocol in the UCLA Southern California Genotyping Consortium Core Laboratory. Quantile normalized gene expression values were transformed to log2 for genome-wide general linear model analysis. Initial cross-sectional analyses examined baseline data collected prior to randomization in order to determine whether these samples showed the same associations previously observed between individual differences in loneliness and 1) bioinformatic indications of increased pro-inflammatory NF-κB transcription factor activity, and 2) increased monocytemediated gene expression (Cole et al., 2007, 2011). To prevent confounding loneliness with other potential influences on gene expression, all analyses controlled for sex, age, white vs. non-white race/ethnicity, and body mass index. To ensure that results were not confounded by individual differences in the prevalence of specific leukocyte subtypes within the PBMC pool, analyses also controlled for variation in the prevalence of gene transcripts marking T lymphocytes subsets (CD3D, CD3E, CD4, CD8A), B lymphocytes (CD19), NK cells (CD16/FCGR3A, CD56/NCAM1), and monocytes (CD14) (Cole et al., 2007).

Following cross-sectional analyses of baseline loneliness effects, effects of the MBSR intervention on the same two outcomes were evaluated in a 2 (Condition: MBSR vs. WL) × 2 (Time: baseline and post-treatment, repeated measure) factorial design, controlling for the same covariates as in the cross-sectional analyses. In both analyses, differentially expressed genes were identified by linear model parameter estimates exceeding a pre-specified substantive effect-size cut-off (Cross-sectional analysis: 25% difference over the observed interquartile range of loneliness scores, or 1% per scale point; Condition × Time interaction: ≥25% difference across Conditions in the average magnitude of the Time effect). Differentially expressed genes were then analyzed by the TELiS transcription factor search engine (Cole et al., 2005) to assess the prevalence of transcription factor-binding motifs targeted by the pro-inflammatory transcription factor NF-κB (TRANSFAC motif matrices V$NFKB_Q6 and V$CREL_01) in the promoter regions of genes that were relatively up-regulated over Time in MBSR vs. relatively up-regulated over time in the WL conditions, with results averaged over 9 parametric variations in motif scan stringency and promoter length (Miller et al., 2009). To identify the specific white blood cell subtypes mediating the observed differences in gene expression, we carried out Transcript Origin Analysis on the differentially expressed genes (Cole et al., 2011).

C Reactive Protein (CRP) and Interleukin-6 (IL-6) were measured in EDTA plasma samples by a high sensitivity ELISA (Immundiagnostik, ALPCO Immunoassays, Salem, NH) according to the manufacturer's protocol, but with an extended standard curve to a lower limit of detection of 0.2 mg/L. All samples were assayed in duplicate, with baseline and post-intervention samples from the same individual tested on the same ELISA plate. To correct for non-normality, CRP and IL-6 values were log-transformed prior to analysis (non-transformed CRP and IL-6 values are available in Table 3). MLMs tested for treatment condition (MBSR vs WL) × time (baseline vs. post-treatment) interactions on log transformed CRP and IL-6 using SPSS 19.0 (IBM, Armonk, New York). Treatment Condition and Time were modeled as fixed effects.

Table 3.

Effects of the MBSR Program on CRP and IL-6 in mg/L.

| Pre Mean | SE | Post Mean | SE | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Log-Transformed CRP | MBSR | .15 | .13 | .03 | .14 |

| WL | −.02 | .14 | .03 | .14 | |

|

| |||||

| Raw CRP | MBSR | 2.98 | 1.15 | 2.09 | 1.25 |

| WL | 3.42 | 1.17 | 3.06 | 1.17 | |

|

| |||||

| Log-Transformed IL-6 | MBSR | .10 | .08 | .14 | .09 |

| WL | .03 | .08 | .03 | .08 | |

|

| |||||

| Raw IL-6 | MBSR | 2.31 | .69 | 2.45 | .72 |

| WL | 1.79 | .71 | 1.41 | .71 | |

Notes: Means and Standard Errors at baseline (Pre) and post-treatment (Post) in the Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction (MBSR) and Wait-List (WL) groups for CRP and IL-6.

Results

Preliminary Analyses

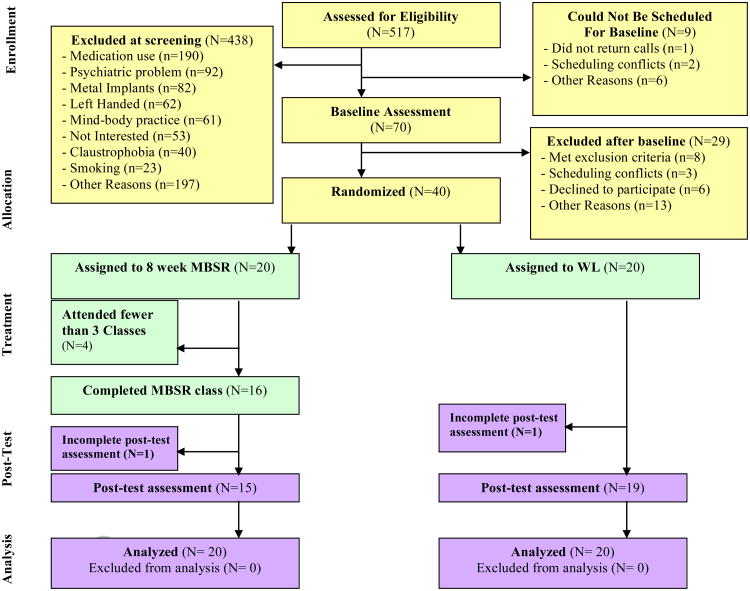

The MBSR and WL groups did not significantly differ on 131any measured demographic characteristics at baseline (see Table 1), indicating success of randomization. A CONSORT flowchart (Figure 1) depicts the flow of participants retained at each phase of the trial. Six participants dropped out of the study prior to completing post-treatment measures, reflecting a 15% dropout rate, which is comparable to attrition rates observed in published MBSR studies (Baer, 2003). More participants dropped out of the MBSR treatment group (N=5) compared to WL (N=1), this difference was marginally significant (χ2(1)= 3.04, p= 0.07). We note that this difference became approximately equal when five (N=5) WL participants dropped out of the MBSR program when it was offered to them after completing the primary treatment trial. These results suggest that the attention and behavioral training demands of MBSR produce modest experimental mortality compared to no treatment. Study dropouts in the primary treatment trial (N=6) were compared to treatment completers (N=34) on all measured baseline demographic characteristics and no significant differences emerged. However, the one exception was that males in the study were more likely to drop out (3/8) compared to females (3/32) (χ2(1)= 3.78, p= 0.05).

Table I.

Baseline Characteristics of Randomized Participants.

| Characteristic | MBSR Group | WL Group | Difference Statistic |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age [mean years (SD)] | 64.35 (6) | 65.16 (8) | t(37)= -.34, p= 0.74 |

| Gender | χ2(1)=.33, p= 0.57 | ||

| Male | 3 | 5 | |

| Female | 17 | 15 | |

| Ethnicity | χ2(5)= 3.55, p= 0.62 | ||

| Caucasian | 13 | 13 | |

| African American | 2 | 3 | |

| Asian American | 2 | 1 | |

| Latino(a) | 3 | 1 | |

| Native American | 0 | 1 | |

| Other | 0 | 1 | |

| Employment Status | χ2(3)= 5.33, p= 0.15 | ||

| Retired | 10 | 4 | |

| Unemployed | 0 | 1 | |

| Part-time | 5 | 4 | |

| Full-time | 5 | 10 | |

| Education | χ2(3)= 2.12, p= 0.55 | ||

| High school degree | 0 | 1 | |

| Some college | 6 | 3 | |

| College degree | 3 | 4 | |

| Graduate work | 11 | 11 | |

| Body Mass Index | 25.22 (4) | 25.22 (4) | t(37)= .003, p= 0.99 |

| Cognitive Impairment (MMSE) | 28.00 (2) | 27.84 (2) | t(37)= .24, p= 0.81 |

| Log-transformed CRP | .15 (.58) | -.02 (.74) | t(37)= .86, p= 0.39 |

| Log-transformed IL-6 | .10 (.42) | .03 (.34) | t(37)= -.58, p= 0.24 |

Notes: Standard deviation values are provided in parentheses in the MBSR group and WL Group columns. MBSR = Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction, WL = WL; MMSE = Mini-Mental State Exam; CRP = C Reactive Protein

Figure 1.

CONSORT flowchart of participants retained at each phase of the trial.

MBSR participants who completed the treatment trial (N=15) completed an average 7.20 (SD=1.15) out of the eight weekly classes offered, and all of these participants participated in the six-hour, day-long retreat held in week six of the MBSR program. MBSR treatment completers also completed, on average, 737 minutes of home meditation practice with home practice meditation compact discs over the course of the 8-week treatment (SD= 523.13). Moreover, as a manipulation check, we also confirmed that the MBSR program (compared to WL) increased self-reported mindfulness skills from baseline to post-treatment (see Table 2).

Table 2.

Effects of the MBSR program on self-reported mindfulness skills, as measured by the Kentucky Inventory of Mindfulness Skills (KIMS).

| Pre Mean | SE | Post Mean | SE | F-value | p-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| KIMS | MBSR | 137.15 | 3.96 | 148.24 | 4.19 | 19.72 | <.01 |

| WL | 137.61 | 3.99 | 133.88 | 3.96 | |||

|

| |||||||

| Observe | MBSR | 37.60 | 1.74 | 41.48 | 1.86 | 6.39 | .02 |

| WL | 40.77 | 1.75 | 40.40 | 1.74 | |||

|

| |||||||

| Describe | MBSR | 31.75 | 1.29 | 34.20 | 1.37 | 8.77 | .01 |

| WL | 30.07 | 1.30 | 29.08 | 1.29 | |||

|

| |||||||

| Awareness | MBSR | 32.00 | 1.38 | 34.29 | 1.46 | 4.48 | .04 |

| WL | 32.80 | 1.39 | 32.50 | 1.38 | |||

|

| |||||||

| Judgment | MBSR | 35.80 | 1.44 | 38.25 | 1.60 | 6.03 | .02 |

| WL | 33.90 | 1.46 | 31.90 | 1.44 | |||

Notes: Means and Standard Errors at baseline (Pre) and post-treatment (Post) in the Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction (MBSR) and Wait-List (WL) groups for the mindfulness skills composite (KIMS) and each of the KIMS subscales (Observe, Describe, Awareness, Judgment). F and corresponding p-values refer to the treatment condition × time interaction.

MBSR Training and Loneliness

Consistent with the prediction that MBSR reduces loneliness compared to a WL control condition, a mixed effect linear model revealed a significant treatment condition × time interaction (F(1,35)=7.86, p=.008). Specifically, MBSR participants had significant decreases in loneliness from baseline (M=42.35, SE=2.23) to post-treatment (M=37.40, SE=2.51) compared to small increases from baseline (M=38.40, SE=2.33) to post-treatment (M=40.75, SE=2.30) in WL control participants. A pairwise comparison found no significant differences between the MBSR and WL groups at baseline (Mdiff =3.95, p=.23). As an additional test of MBSR effects on loneliness, we conducted a follow-up ANCOVA in our subsample with complete pre-post data (N=33): MBSR participants (M=35.65, SE=2.02) had lower loneliness levels at post-test compared to WL participants (M=42.33, SE=1.73), after controlling for baseline loneliness (F(1,30)=6.27, p=.02, η2=.17; a large overall effect size).

MBSR Training, Pro-Inflammatory Gene Expression and Protein Biomarkers

To verify that the older adults in this sample showed loneliness-related increases in expression of NF-κB target genes as previously observed (Cole et al., 2007), we analyzed relationships between baseline loneliness scores and leukocyte gene expression profiles. Results identified 256 genes showing ≥25% difference in expression across the inter-quartile range of observed scores (87 genes up-regulated in high-lonely individuals, and 169 genes up-regulated in low-lonely individuals; listed in Supplementary Table 1). TELiS bioinformatics analysis identified greater prevalence of NF-κB target genes in the set of genes relatively up-regulated in high-lonely individuals compared to genes up-regulated in low-lonely individuals (mean prevalence ratio=1.89, z=3.05, p=.003, and ratio=1.21, z=2.39, p=.017, respectively, for the two distinct NF-κB DNA target patterns tested). Transcript origin analyses found genes up-regulated in association with loneliness to originate predominately from monocytes (t(68)=2.90, p=.003), and to a lesser extent, from B lymphocytes (t(68)=1.71, p=.046).

To determine whether MBSR might reverse the loneliness-related pattern of NF-κB/monocyte-associated gene expression, analyses compared the magnitude of pre-post change in gene expression across conditions. Results identified 143 genes showing ≥25% differential change over time between conditions (69 genes relatively down-regulated in MBSR subjects relative to WL controls and 74 genes relatively down-regulated in WL controls; listed in Supplementary Table 2). Consistent with reversal of loneliness-related transcriptional alterations by MBSR, TELiS bioinformatics analysis indicated reduced activity of NF-κB target genes in MBSR-treated subjects relative to WL controls (mean prevalence ratio=0.67, z=−2.43, p=.015 and ratio= 0.53, z=−2.14, p=.029 for the two NF-κB patterns tested). Monocytes were again identified as the primary cellular carrier of genes down-regulated in MBSR-treated participants (t(61)=2.08, p=.021).

There was not strong evidence for MBSR in reducing protein markers of inflammation (as measured by CRP and IL-6), although we observed a marginally significant effect for CRP that was consistent with the observed group differences in proinflammatory gene expression. Specifically, CRP was not significantly different between the MBSR and WL groups at baseline (Table 1), and MBSR participants had decreases in log-transformed CRP compared to WL participants from baseline to post-treatment (a marginally significant treatment condition × time interaction: F(1,33)=3.39, p=.075). We did not observe a significant treatment condition × time interaction for log-transformed IL-6 (F(1,32)=.33, p=.57). Table 3 provides the means and standard errors for raw and log-transformed CRP and IL-6.

MBSR Training and Health Behaviors

To determine whether changes in health behaviors might contribute to the observed effects, we conducted secondary data analyses testing whether MBSR affected measures of self-reported sleep quality and exercise. Results showed no significant treatment condition × time interaction in a MLM analyzing overall sleep quality on the composite Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index measure (Buysse et al., 1989) (p>.39) or self-reported vigorous exercise (p>.12).

Discussion

Using a randomized controlled trial design, the present study identifies MBSR as a novel approach for reducing loneliness in older adults. Although previous studies suggest a role for mindfulness-based treatments in reducing distress (Brown et al., 2007) and in fostering improved relational well-being (Carson et al., 2004; Brown et al., 2008), this is the first study to show that mindfulness meditation training reduces feelings of loneliness. We note that although we had no enrollment criteria for recruiting a lonely sample, our Los Angeles community sample had elevated levels of loneliness at baseline (M=41, SD=10) compared to a Midwestern older adult sample (M=37, SD=8) (Cacioppo, Hawkley, & Thisted, 2010) or an undergraduate student sample (M=37, SD=10) (Russell, Peplau, & Cutrona, 1980).

In addition to reducing loneliness, the present work provides additional clues into how MBSR may impact health in lonely older adults; namely, by down-regulating pro-inflammatory NF-κB -related gene expression dynamics that tend to be up-regulated in lonely older adults (Cole et al., 2007, 2011). The functional significance of the change in pro-inflammatory gene expression is not clear, as this study did not assess whether these gene expression effects translate into meaningful differences on inflammatory biology or disease outcomes. However, we note that CRP levels were elevated at baseline in our older adult sample (see Table 3), which suggests that our sample may have elevated cardiovascular disease and mortality risk (cf. Harris et al., 1999; Cesari et al., 2003). And there was some indication of differential trends in log-transformed CRP change over time, suggesting that MBSR may have reduced inflammatory biology in this initial pilot study. We did not observe any evidence for MBSR reducing IL-6, which may reflect the fact that there were low levels of IL-6 in our baseline sample (M=1.99 pg/ml, SE= .48) (cf. Harris et al., 1999), or the high biological variability commonly observed in spot IL-6 levels (vs. CRP, which provides a more smoothed, time integrated measure of IL-6 activity over the course of previous days) (Epstein et al., 1999; Pepys et al., 2003). Future MBSR RCT studies should evaluate these protein effects in lonely older adult samples with elevated cardiovascular and inflammatory disease risk factors.

Our finding that MBSR reduces pro-inflammatory gene expression provides a potential mechanistic account for previous studies showing that MBSR reduces stimulated pro-inflammatory cytokine production (Carlson et al., 2003, 2007). Moreover, our gene expression findings contribute to a new literature showing that behavioral stress management interventions, such as Relaxation Response training and Cognitive-Behavioral Stress Management training can are associated with gene expression in cells of the immune system (Dusek et al., 2008; Antoni et al., 2012). One implication of this work is that a common transcription control pathway (i.e., downregulated activity of NF-κB) may link a wide range of behavioral stress management interventions with reduced inflammatory disease risk.

Although our study highlights how MBSR can reduce subjective lonely feelings and loneliness-related pro-inflammatory gene expression in leukocytes, it will be important in future studies to consider the specific psychological and biological pathways that may link mindfulness meditation training with these effects. Recent work suggests that the health-compromising effects of loneliness are due to one's subjective perception of isolation and not one's objective number of social contacts (Cole et al., 2007, 2011), suggesting that psychological perceptions of social disconnection may be a critical component of loneliness. One potential psychological pathway then, is that MBSR reduces psychological perceptions of social threat or distress, and reduced distress may decrease perceptions of loneliness. As the Buddhist Nun Pema Chodron suggests (opening quote), mindfulness meditation training can “turn our fearful patterns upside down”, reducing the distress that can accompany loneliness (Chodron, 2000). At present, we show that MBSR (compared to a WL condition) reduces perceptions of loneliness, and it will be important for subsequent research to consider how changes in psychological pathways such as distress, depression, and threat appraisals in social encounters potentially explain how MBSR reduces loneliness in older adults (cf. (Cacioppo and Hawkley, 2009).

The biological pathways linking MBSR to changes in pro-inflammatory gene expression also need to be clarified in future studies. MBSR could potentially alter activity of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis or sympathetic nervous system, both of which produce stress mediators (e.g., cortisol, norepinephrine, eprinephrine) that can modulate NF-κB activity and pro-inflammatory gene expression (for reviews, Cole, 2009; Irwin and Cole, 2011). Indeed, some initial evidence suggests that MBSR alters diurnal cortisol output (Carlson et al., 2004; Witek-Janusek et al., 2008; Brand et al., 2012) (cf. Brown et al., in press). It is important for future studies to test these stress-reduction mediated biological pathways. Finally, it is possible that MBSR effects on gene expression may be explained by changes in health behaviors. Though, we did not find evidence that MBSR altered measures of sleep quality or exercise use in this sample, future studies might benefit from inclusion of objective measures of sleep and activity (e.g., actigraphy, polysomnography).

One limitation of the present study was the use of a WL control group. Future studies using active control groups that include nonspecific and/or specific components of the intervention will help clarify what aspects of the MBSR program decrease loneliness. It is possible that observed changes in loneliness in MBSR vs. WL control could be explained by non-specific factors (e.g., social support, participant contact with an instructor). For example, it may be that the group-based format of MBSR classes is providing social support (and networking), and these social factors are reducing loneliness. However, it is unlikely that non-specific group support accounts for the observed decreases in loneliness in the MBSR condition, as prior randomized controlled trials have found that loneliness is not altered following administration of social support and social skills training (Masi et al., 2011). Moreover, when mindfulness meditation training is taught individually (i.e., not in a group-based format) stress symptoms are reduced along with improvements in markers of physical health (Kabat-Zinn et al., 1998). Nevertheless, future RCT studies that control for non-specific factors with well-matched active treatment control conditions, and using new control programs as recently described (e.g., MacCoon et al., 2012) will advance understanding of the components of MBSR that are effectively driving benefit.

Conclusions

The present work makes two novel contributions to the literature. This study provides a promising initial indication that the 8-week MBSR program may reduce perceptions of loneliness in older adults, which is a well-known risk factor for morbidity and mortality in aging populations (Hawkley and Cacioppo, 2010). Second, consistent with previous reports (Cole et al., 2007, 2011), we find that loneliness is associated with up-regulated expression of pro-inflammatory genes in circulating leukocytes, and that MBSR can significantly down-regulate the expression of inflammation-related genes in parallel with reductions in loneliness. Although promising, it will be important for future studies to replicate and extend these initial findings in larger samples with active control groups.

Supplementary Material

Research Highlights.

Mindfulness meditation training reduces loneliness and pro-inflammatory gene expression in older adults.

Acknowledgments

This project was made possible by generous support from National Institutes of Health (R01-AG034588; R01-AG026364; R01-119159; R01-HL079955; R01-MH091352 (MRI)), the Cousins Center for Psychoneuroimmunology at UCLA, the Inflammatory Biology Core Laboratory of the UCLA Claude D. Pepper Older Americans Independence Center funded by the National Institute of Aging (5P30 AG028748), the UCLA Social Genomics Core Laboratory (P30-AG107265), and the Pittsburgh Life Sciences Greenhouse Opportunity Fund. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript. We thank Jaime Moran, Norr Santz, and Laura Pacilio for technical assistance; Robert Low for help coordinating the study; and our MBSR instructors Howard Blumenfeld, Gloria Kamler, and Catherine Baum.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Registered on Clinicaltrials.gov: NCT01532596

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Antoni MH, Lutgendorf SK, Blomberg B, Carver CS, Lechner S, Diaz A, Stagl J, Arevalo JMG, Cole SW. Cognitive-Behavioral Stress Management Reverses Anxiety-Related Leukocyte Transcriptional Dynamics. Biol Psychiat. 2012;71:366–372. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2011.10.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baer RA. Mindfulness training as a clinical intervention A conceptual and empirical review. Clin Psychol Sci Pract. 2003;10:125–143. [Google Scholar]

- Baer RA, Smith GT, Allen KB. Assessment of mindfulness by self-report. Assessment. 2004;11:191–206. doi: 10.1177/1073191104268029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brand S, Holsboer-Trachsler E, Naranjo JR, Schmidt S. Influence of Mindfulness Practice on Cortisol and Sleep in Long-Term and Short-Term Meditators. Neuropsychobiology. 2012;65:109–118. doi: 10.1159/000330362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown KW, Ryan RM, Creswell JD. Mindfulness: Theoretical foundations and evidence for its salutary effects. Psychol Inq. 2007;18:211–237. [Google Scholar]

- Brown KW, Ryan RM, Creswell JD, Niemiec CP. Transcending self-interest: Psychological explorations of the quiet ego. Washington DC: American Psychological Association; 2008. Beyond me: Mindful responses to social threat; pp. 75–84. [Google Scholar]

- Brown KW, Weinstein N, Creswell JD. Trait mindfulness modulates neuroendocrine and affective responses to social evaluative threat. Psychoneuroendocrinology. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2012.04.003. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buysse DJ, Reynolds CF, Monk TH, Berman SR, Kupfer DJ. The Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index: a new instrument for psychiatric practice and research. Psychiat Res. 1989;28:193–213. doi: 10.1016/0165-1781(89)90047-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cacioppo JT, Hawkley LC. Perceived social isolation and cognition. Trends Cogn Sci. 2009;13:447–454. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2009.06.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlson LE, Speca M, Faris P, Patel KD. One year pre-post intervention follow-up of psychological, immune, endocrine and blood pressure outcomes of mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR) in breast and prostate cancer outpatients. Brain Behav Immun. 2007;21:1038–1049. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2007.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlson LE, Speca M, Patel KD, Goodey E. Mindfulness-based stress reduction in relation to quality of life, mood, symptoms of stress, and immune parameters in breast and prostate cancer outpatients. Psychosom Med. 2003;65:571–581. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000074003.35911.41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlson LE, Speca M, Patel KD, Goodey E. Mindfulness-based stress reduction in relation to quality of life, mood, symptoms of stress and levels of cortisol, dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate (DHEAS) and melatonin in breast and prostate cancer outpatients. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2004;29:448–474. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4530(03)00054-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carson JW, Carson KM, Gil KM, Baucom DH. Mindfulness-based relationship enhancement*. Behav Ther. 2004;35:471–494. [Google Scholar]

- Cesari M, Penninx BWJH, Newman AB, Kritchevsky SB, Nicklas BJ, Sutton-Tyrrell K, Rubin SM, Ding J, Simonsick EM, Harris TB, et al. Inflammatory markers and onset of cardiovascular events. Circulation. 2003;108:2317–2322. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000097109.90783.FC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chodron P. Six kinds of loneliness. Shambhala Sun 2000 [Google Scholar]

- Cole SW. Social regulation of human gene expression. Curr Dir Psychol Sci. 2009;18:132–137. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8721.2009.01623.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cole SW, Arevalo JMG, Takahashi R, Sloan EK, Lutgendorf SK, Sood AK, Sheridan JF, Seeman TE. Computational identification of gene–social environment interaction at the human IL6 locus. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2010;107:5681–5686. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0911515107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cole SW, Hawkley LC, Arevalo JM, Sung CY, Rose RM, Cacioppo JT. Social regulation of gene expression in human leukocytes. Genome Biol. 2007;8:R189–R189. 13. doi: 10.1186/gb-2007-8-9-r189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cole SW, Hawkley LC, Arevalo JMG, Cacioppo JT. Transcript origin analysis identifies antigen-presenting cells as primary targets of socially regulated gene expression in leukocytes. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2011;108:3080–3085. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1014218108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cole SW, Yan W, Galic Z, Arevalo J, Zack JA. Expression-based monitoring of transcription factor activity: the TELiS database. Bioinformatics. 2005;21:803–810. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bti038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dusek JA, Otu HH, Wohlhueter AL, Bhasin M, Zerbini LF, Joseph MG, Benson H, Libermann TA. Genomic counter-stress changes induced by the relaxation response. PLos One. 2008;3:e2576. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0002576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epstein FH, Gabay C, Kushner I. Acute-phase proteins and other systemic responses to inflammation. New England Journal of Medicine. 1999;340:448–454. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199902113400607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finch CE. The biology of human longevity: inflammation, nutrition, and aging in the evolution of lifespans. Burlington, MA: Academic Press; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Findlay RA. Interventions to reduce social isolation amongst older people: where is the evidence? Ageing Soc. 2003;23:647–658. [Google Scholar]

- Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. Mini-mental state: a practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res. 1975;12:189–198. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(75)90026-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris TB, Ferrucci L, Tracy RP, Corti MC, Wacholder S, Ettinger WH, Jr, Heimovitz H, Cohen HJ, Wallace R. Associations of elevated Interleukin-6 and C-Reactive protein levels with mortality in the elderly*. Am J Med. 1999;106:506–512. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(99)00066-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawkley LC, Cacioppo JT. Loneliness matters: a theoretical and empirical review of consequences and mechanisms. Ann Behav Med. 2010;40:218–227. doi: 10.1007/s12160-010-9210-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hölzel BK, Lazar SW, Gard T, Schuman-Olivier Z, Vago DR, Ott U. How does mindfulness meditation work? Proposing mechanisms of action from a conceptual and neural perspective. Perspect Psychol Sci. 2011;6:537–559. doi: 10.1177/1745691611419671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irwin MR, Cole SW. Reciprocal regulation of the neural and innate immune systems. Nat Rev Immunol. 2011;11:625–632. doi: 10.1038/nri3042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kabat-Zinn J. Full catastrophe living: Using the wisdom of your body and mind to face stress, pain, and illness. New York, NY: Delta; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Kabat-Zinn J, Wheeler E, Light T, Skillings A, Scharf MJ, Cropley TG, Hosmer D, Bernhard JD. Influence of a mindfulness meditation-based stress reduction intervention on rates of skin clearing in patients with moderate to severe psoriasis undergoing phototherapy (UVB) and photochemotherapy (PUVA) Psychosom Med. 1998;60:625–632. doi: 10.1097/00006842-199809000-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lengacher CA, Kip KE, Barta MK, Post-White J, Jacobsen P, Groer M, Lehman B, Moscoso MS, Kadel R, Le N, et al. A Pilot Study Evaluating the Effect of Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction on Psychological Status, Physical Status, Salivary Cortisol, and Interleukin-6 Among Advanced-Stage Cancer Patients and Their Caregivers. [Accessed July 7, 2012];Journal of Holistic Nursing. 2012 doi: 10.1177/0898010111435949. Available at http://jhn.sagepub.com/content/early/2012/02/21/0898010111435949.abstract. [DOI] [PubMed]

- MacCoon DG, Imel ZE, Rosenkranz MA, Sheftel JG, Weng HY, Sullivan JC, Bonus KA, Stoney CM, Salomons TV, Davidson RJ, et al. The validation of an active control intervention for Mindfulness Based Stress Reduction (MBSR) Behav Res Ther. 2012;50:3–12. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2011.10.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masi CM, Chen HY, Hawkley LC, Cacioppo JT. A meta-analysis of interventions to reduce loneliness. Pers Soc Psychol Rev. 2011;15:219–266. doi: 10.1177/1088868310377394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller GE, Chen E, Fok AK, Walker H, Lim A, Nicholls EF, Cole S, Kobor MS. Low early-life social class leaves a biological residue manifested by decreased glucocorticoid and increased proinflammatory signaling. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2009;106:14716–14721. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0902971106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olsen RB, Olsen J, Gunner-Svensson F, Waldstrom B. Social networks and longevity. A 14 year follow-up study among elderly in Denmark. Soc Sci Med. 1991;33:1189–1195. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(91)90235-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pepys MB, Hirschfield GM, et al. C-reactive protein: a critical update. Journal of Clinical Investigation. 2003;111:1805–1812. doi: 10.1172/JCI18921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russell D, Peplau LA, Cutrona CE. The revised UCLA Loneliness Scale: Concurrent and discriminant validity evidence. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1980;39:472–480. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.39.3.472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thurston RC, Kubzansky LD. Women, loneliness, and incident coronary heart disease. Psychosom Med. 2009;71:836–842. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e3181b40efc. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tilvis RS, Laitala V, Routasalo PE, Pitkala KH. Suffering from loneliness indicates significant mortality risk of older people. J Aging Res. 2011;2011:1–5. doi: 10.4061/2011/534781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson RS, Krueger KR, Arnold SE, Schneider JA, Kelly JF, Barnes LL, Tang Y, Bennett DA. Loneliness and risk of Alzheimer disease. Arch Gen Psychiat. 2007;64:234–240. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.64.2.234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Witek-Janusek L, Albuquerque K, Chroniak KR, Chroniak C, Durazo-Arvizu R, Mathews HL. Effect of mindfulness based stress reduction on immune function, quality of life and coping in women newly diagnosed with early stage breast cancer. Brain Behav Immun. 2008;22:969–981. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2008.01.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.