Abstract

MicroRNAs (miRs) comprise a class of tiny (∼19–24 nucleotide), noncoding RNAs that regulate gene expression posttranscriptionally. Since the discovery of the founding members lin-4 and let-7 as key regulators in the developing nematode, miRs have been found throughout the eukaryotic kingdom. Functions for miRs are wide-ranging and encompass embryogenesis, stem cell biology, tissue differentiation, and human diseases including cancers. In this chapter, we begin by acquainting our readers with miRs and introducing them to their biogenesis. Then, we focus on the roles of miRs in stem cells during tissue development and homeostasis. We use mammalian skin as our main paradigm, but we also consider miR functions in several different types of adult stem cells. We conclude by discussing future challenges that will lead to a comprehensive understanding of miR functions in stem cells and their lineages.

1. Introduction

MicroRNAs (miRs) comprise a class of noncoding, regulatory RNAs that are widely expressed in both plants and animals (reviewed by Ambros, 2004; Bartel, 2009). In animals, the miR pathway constitutes small RNAs and their protein partners, including Dicer and Argonaute proteins. Their origins can be traced back to sponges, making them one of the most ancient pathways to regulate output of the transcriptome (Grimson et al., 2008).

MiRs regulate mRNA stability and protein production by recruiting the RNA-induced silencing complex (RISC) to their cognate target sites (reviewed by Bartel, 2009). It is estimated that more than one-third of protein-coding mRNAs are regulated by miRs (Friedman et al., 2009; Lewis et al., 2005). In turn, miR-mediated regulation is believed to have a widespread impact both on protein output of the transcriptome (Baek et al., 2008; Selbach et al., 2008) and on evolution of gene regulatory networks (Farh et al., 2005; Stark et al., 2005). miR's recognition of its mRNA targets is primarily mediated by base-pairing between nucleotides no. 2–8 of the miR, commonly referred to as its “seed sequences,” and complementary mRNA sequences that are often located within the 3′-untranslated region (3′UTR) (reviewed by Bartel, 2009). Although the targets of a miR cannot be identified simply by whether an mRNA contains a sequence of perfect complementarity to the miR's seed sequence, there is no doubt that a miR's seed sequence plays a critical role in target recognition. Such evidence includes not only preferential conservation of the seed sequences of miRs and their cognate sequences in the 3′UTR of mRNA but also the crystal structures of these sequences complexed with the Argonaute protein (Wang et al., 2009; Xie et al., 2005). However, because a single miR can recognize >100 targets, a single mRNA can be simultaneously regulated by multiple miRs, and the homology match is not always a perfect one, miR-mediated gene regulation networks are extraordinarily complex.

The complexity of miR-mediated regulation and its potential impact on the expression of a large number of proteins has drawn increasing attention to these tiny riboregulators. Since the discovery a decade ago of let-7, much progress has been made in deciphering miR expression patterns and functions in embryonic development, differentiation, maintenance of stem cells, and human diseases (reviewed by Ambros, 2004; Bartel, 2009). The existence of a hitherto unappreciated dimension of gene regulation mediated by miRs led to an explosion of new studies, which have not only provided new insights into our understanding of developmental and stem cell biology but also pointed to new directions for therapeutic applications of stem cells.

In this review, we consider the most recent progress toward understanding the biological role of miRs in mammalian skin development and in various adult stem cells. Because of the significant interest in this topic, many excellent reviews have been published in recent years and we also refer our readers to these chapters for a comprehensive view of the field (Gangaraju and Lin, 2009; Ivey and Srivastava, 2010; Martinez and Gregory, 2010).

2. The Discovery of miRs and their Roles in Caenorhabditis Elegans

The founding members of the miR family, namely, lin-4 and let-7, were originally identified as heterochronic genes that govern developmental transitions in the nematode C. elegans (Lee et al., 1993; Pasquinelli et al., 2000; Reinhart et al., 2000; Wightman et al., 1993). In those early studies, lin-4 and let-7 were both found to negatively regulate the translation of master regulators of differentiation such as lin-14, lin-28, and lin-41. Intriguingly, these proteins were found not only to maintain an early developmental lineage but also then be downregulated as the animal transitions to a later lineage. Thus for example, lin-4 functions in downregulating lin-14 and lin-28 through the first larval stage (L1), while let-7 down-regulates hbl-1 and lin-41 when the animal develops from the fourth larval stage (L4) to the adult stage (Lee et al., 1993; Reinhart et al., 2000).

The negative regulatory networks involving lin-4, let-7, and their mRNA targets provided the basis for the paradigm, whereby miRs help deplete protein production by mRNAs that were inherited from an earlier stage in the lineage, but which impair progression to the next step. In doing so, miRs facilitate a precise, robust transition through the developmental program. Indeed, in many of the recent investigations which we discuss in the chapter, and which are aimed at exploring miR regulation of mammalian stem cell lineages and development, miRs appear to act in accordance to such model.

Although lin-4 was identified in 1993, it took the subsequent discovery of let-7 in 2000 and the rapid realization that it is highly conserved before miRs began to attract broader interest from the scientific community. A decade later, as the sequencing of genomes and their miR components soared to an unprecedented pace, it has become apparent that lin-4 is also deeply conserved (Christodoulou et al.,2010). However, unlike let-7 whose sequence is almost identical between C. elegans and human, the conservation between lin-4 and its human orthologues miR-125a/b is limited to the 5′ end of the miR. Despite these variations, the miR pathway has emerged as one of the most ancient pathways that are deeply involved in animal evolution (Christodoulou et al., 2010; Grimson et al., 2008). Notably, miR-100 is likely to be the most deeply conserved miR as its orthologues are identified from Nematostella to human (Christodoulou et al., 2010; Grimson et al., 2008).

Because of the ease for genetic manipulation, C. elegans has long served as a fertile ground for functional characterization of novel genes by the loss-of-function studies. Recently, the roles of most individual miRs and miR families have been investigated by examining developmental defects and viability in a large collection of miR knockout (KO) models in C. elegans (Alvarez-Saavedra and Horvitz, 2010; Miska et al., 2007). Surprisingly, very few miRs either individually (7 out of 95) or collectively as a family (3 out of 15 families) were found to be essential for development and viability in these studies (Alvarez-Saavedra and Horvitz, 2010; Miska et al., 2007). However, when challenged with sensitized genetic background, many miR mutants (25 out of 31 miRs) manifest strong defects (Brenner et al., 2010). These interesting findings are also echoed by studies with miR KO mouse models where miR KO animals often only show discernible defects under stress conditions (Liu and Olson, 2010). Together, these results support the view that the miR-mediated regulatory network is complex and suggest that rather than having absolute functions, miRs may instead operate to more rapidly reinforce or enhance a pathway, a feature that may only surface under circumstances like stress, where the sense of urgency in responding is more acutely felt by a tissue.

3. The Biogenesis Pathways of miR

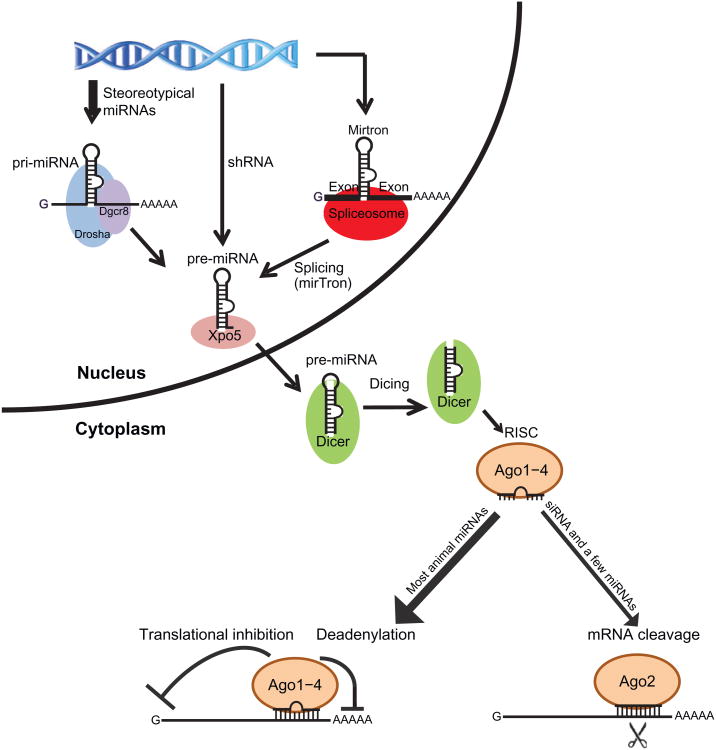

In the past decade, the miR biogenesis pathway has been extensively investigated. For the clarity of this chapter, we reiterate some of the key steps that are important to our discussion but refer our readers to several recent reviews for detailed analysis (Kim et al., 2009; Krol et al., 2010).

In mammals, most miRs are transcribed by RNA polymerase II but some of them are generated by RNA polymerase III (Borchert et al., 2006; Cai et al., 2004). During the transcription of the primary transcript, the flanking sequences of the miR fold into a hairpin structure, called pre-miR, characteristic of miR coding genes (Fig. 7.1). For stereotypical miRs that are represented by most abundantly expressed miRs, the hairpin is first processed by the Drosha–DiGeorge syndrome critical region gene 8 (Dgcr8) microprocessor complex in the nucleus (Denli et al., 2004; Gregory et al., 2004; Han et al., 2004; Landthaler et al., 2004). However, in a few exceptions where the hairpin is generated directly from transcription of short-hairpin RNA or derived from splicing of a certain type of intron that is capable of folding into the hairpin structure (also known as the mirtron pathway), the biogenesis of these noncanonical miRs can bypass the requirement of Drosha/Dgcr8 (Babiarz et al., 2008). In all cases, the liberated hairpin is then exported by Xpo5 (Lund et al., 2004; Yi et al., 2003) to the cytoplasm where it undergoes a second cleavage by Dicer (Hutvagner et al., 2001). After the processing by Dicer, one strand of the double-stranded duplex is selectively incorporated into an RISC composed of one of the four Argonaute proteins and their associated cofactors (Schwarz et al., 2003). Given the nearly universal mechanism for miR biogenesis, it is possible to explore the global function of the miR pathway by genetically deleting either the Drosha-Dgcr8 complex or the Dicer.

Figure 7.1.

Dgcr8 and Dicer are essential components for miRNA biogenesis. Most highly expressed miRs are transcribed as long RNA transcripts and processed by the Drosha/Dgcr8 complex to liberate the hairpin precursor (pre-miRNA) in the nucleus. However, a few miRs are either directly transcribed as short-hairpin (sh) RNA or processed via splicing (the mirtron pathway). Thus these miRs are independent of the Drosha/Dgcr8 processing for the generation of the hairpin. After transported to the cytoplasm by Xpo5, pre-miRNAs are further processed by Dicer. One strand of the double-stranded RNA duplex is complexed with Ago proteins to form the RISC.

4. Mammalian Skin as a Model to Uncover How miRs Regulate Stem Cell Biology and Tissue Morphogenesis

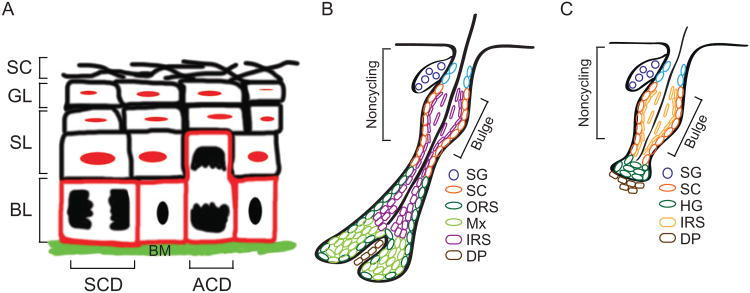

With its easy accessibility and established genetic tools for conditional targeting, the mouse skin epithelium provides an excellent system to explore functions of miR regulatory pathways in mammalian stem cell biology and tissue morphogenesis. The architecture of the skin is spatially and temporally well defined. The skin epithelium is separated from the underlying dermis by a basement membrane rich in extracellular matrix. In the epidermis, an inner (basal) layer of progenitors periodically withdraws from the cell cycle and commits to upward program of terminal differentiation, involving three distinct stages: spinous, granular, and stratum corneum (Fig. 7.2A). Transcriptional activity ceases at the transition after the granular stage, as terminally differentiated dead squames are sloughed from the skin surface, continually replaced by inner cells moving outward.

Figure 7.2.

Illustration of skin lineages. (A) The epidermis comprises of four layers: basal layer (red, BL), spinous layer (black, SL), granular layer (black, GL), and stratum corneum (black, SC). Stem cells are located in the basal layer, residing on a basement membrane (BM). They undergo symmetric cell division (SCD) to double their population or asymmetric cell division (ACD) to self-renew and generate another daughter for terminal differentiation. (B) Hair follicle and their associated sebaceous glands are appendages of the epidermis. Stem cells (orange, SC) reside in the bulge stem cell niche. They move upward to become progenitor cells for the sebaceous gland (light blue, SG-P) and subsequently terminally differentiated to sebaceous gland cells (dark blue, SG-M). In the hair follicle lineage, stem cells give rise to outer root sheath (dark green, ORS), matrix (light green, Mx), inner root sheath (purple, IRS), and eventually hair shaft. Derma papilla (DP) is a cluster of mesenchymal cells surrounded by the hair bulb. (C) At the telogen, the secondary hair germ (HG) is formed at the base of the bulge and directly interacts with the DP. Inner root sheath (IRS) is generated directly from the stem cells.

By contrast, hair follicles (HFs) and their associated sebaceous glands (SGs) are appendages of the epidermis (Fig. 7.2B). Hair growth is cyclical, fueled by epithelial stem cells that reside within a niche called the bulge, located just below the SG. At the base of the bulge is an extension of SCs referred to as the secondary hair germ (HG). The HG maintains the closest proximity to an essential cluster of mesenchymal cells, the dermal papilla (DP), which undergoes stimulatory crosstalk with the stem cells. Once activated (the telogen to anagen transition), a new HF emerges from the HG as the DP is pushed downward. At the base of the mature HF and in contact with the DP, matrix cells rapidly but transiently divide and then differentiate in concentric upward cylinders of cells to form the hair shaft at the center and the channel or inner root sheath (IRS) surrounded by the outer root sheath (ORS). Following the anagen growth phase, most of the lower two-thirds of the HF undergo apoptosis and the remaining epithelial strand retracts upward with the DP to begin the cycle anew (Fig. 7.2C).

With over two decades of molecular genetic analyzes of the epidermis and HFs, there is extensive knowledge of the signaling circuitry and physiologically relevant changes in gene expression that occur, not only during normal adult homeostasis and embryonic development but also in wound repair and tumorigenesis. This provides an exceptional foundation for dissecting how miR-mediated regulation fine-tunes these molecular events in mammalian stem cell and tissue biology.

5. Insights into the Global Role of miRs in the Skin Epithelium: Conditional Ablation of Dicer

Not surprisingly, the first insights of the importance of miRs in the skin epithelium came from profiling the ones that are expressed in this tissue and examining the consequences of conditionally ablating Dicer in this tissue (Andl et al., 2006; Yi et al., 2006). Temporal profiling during skin development unveiled a myriad of miRs which are differentially expressed in the epidermis and its notable appendage, the HF (Yi et al., 2006). Interestingly, this included not only miRs such as miR-100, miR-125, and let-7, which are conserved throughout the animal kingdom, but also several vertebrate-specific miRs such as miR-203 and miR-205. As more and more species were analyzed for tissue-specific expression of miRs, it became evident that these miRs are characteristic of the vertebrate skin epithelium.

Complete ablation of Dicer in all mouse tissues results in the arrest of development by embryonic day 7.5 (E7.5) (Bernstein et al., 2003). Epidermal stratification does not take place until E13.5→E16.5, and HFs form in waves from E14.5→P0 (Schmidt-Ullrich and Paus, 2005). Thus to study Dicer function in skin, several groups have generated Dicer conditional KO (cKO) mice by using a floxed Dicer allele and a Cre recombinase transgene driven by a skin epithelial-specific keratin-14 (K14) promoter (Andl et al., 2006; Yi et al., 2006). Like its coexpressed partner K5, K14 becomes strongly active in embryonic skin progenitor cells by ∼E15 (Byrne et al., 1994; Vassar et al., 1989). As such, the K14-Cre-mediated Dicer ablation depletes Dicer and miRs in all skin lineages.

Because the loss of mature miRs is secondary to the ablation of Dicer and the relatively long half-life of miRs, mature miRs were not completely depleted until E17.5 (Yi et al., 2006) or birth (Andl et al., 2006) depending most likely upon strain-specific differences. However, more than 100 miRs were lost by then, and yet the cKO pups initially appeared normal in size and appearance, and the epidermis, HFs, and SGs were correctly specified. Thus, unlike well-established master regulatory circuits, for example, BMP, Wnt, and Notch signaling pathways, the miR pathway did not seem to be required for lineage specification during skin development.

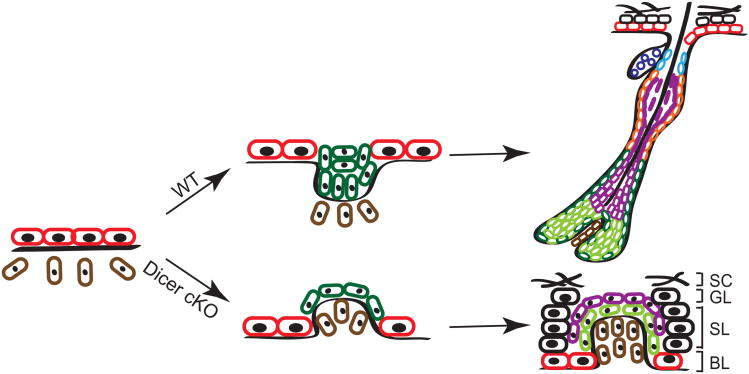

Closer inspection revealed that the epidermis generated the expected architectural and morphological signs of differentiation (Yi et al., 2006). By contrast, developing Dicer-null HFs evaginated upward and arrested within the epidermis, rather than invaginating inward into the dermis (Andl et al., 2006; Yi et al., 2006) (Fig. 7.3). Strikingly, the evaginating HFs attracted the DP into the epidermis, thereby maintaining the mesenchymal–epithelial association typically requisite to execute the program of terminal differentiation. However, only concentric rings of matrix and IRS cells surrounded the basement membrane around the DP, with no traces of hair shaft formation.

Figure 7.3.

Hair follicle evagination in the Dicer cKO skin. In the Dicer-null skin, developing hair follicles evaginate upward and arrest within the epidermis. Notably, the epidermal differentiation is intact except in the region where the epidermal integrity is disrupted by evaginating hair follicles. The same phenotype was also observed in the Dgcr8-null skin, suggesting a causative role of the loss of stereotypical miRs for the defects in hair morphogenesis.

Exactly, how miR-deficiency-induced dysregulation in epithelial gene expression might cause these gross abnormalities remains unclear. However, even when Dicer was ablated after the HFs have formed, they subsequently degenerated, leaving behind only cyst-like structures, and interestingly no bulge compartment (Andl et al., 2006). Thus, the arrest in HFs cannot simply be due to the architectural constraints associated with evagination, but rather must reflect perturbations in the differentiation program itself.

These collective studies on Dicer cKO skin present the view that miRs in the skin might be required to maintain the appropriate output of signaling pathway(s) and, in turn, the finely tuned pathway(s) that are essential for the maintenance of HF stem cells and the mesenchymal–epithelial cross talk that orchestrates their proper downgrowth and lineage progression.

In striking contrast to hypoproliferation within the HF and the depletion of its stem cells, hyperproliferation was observed in the mature Dicer cKO epidermis (Andl et al., 2006). These defects suggest that the specific miRs differentially expressed by these tissues may have functionally distinct roles. If so, HF miRs would appear to control stem cell survival and maintenance, while epidermal miRs seem more likely to govern cell cycle exit and/or the balance between proliferation and differentiation.

Another differential feature of ablating Dicer in the skin was the preferential increase in apoptosis within the HFs, and particularly so within the highly proliferative matrix compartment (Andl et al., 2006; Yi et al., 2006). The specific localization of apoptotic cells was suggestive of either a general requirement of Dicer (miRs) in rapidly dividing cells, consistent with apoptotic phenotypes observed in Dicer cKO limb and T cells (Harfe et al., 2005; Muljo et al., 2005), or a specific requirement for Dicer (miRs) in the hair bulb. Recently, an exciting study has identified the C. elegans Dicer homolog as a caspase substrate, and upon cleavage, the liberated Dicer RNase III domain translocates to the nucleus and becomes a DNase that is critical for the DNA fragmentation during apoptosis (Nakagawa et al., 2010). It is of great interest to examine mammalian Dicer homologues share this function that is independent of the miR pathway, and if so, how it might be differentially regulated in the epidermis and HF.

6. Conditional Ablation of DGCR8

While studies with Dicer cKO skin provided a glimpse of how miRs may be functioning in the skin, two key questions arise: (1) Are the phenotypes observed in the Dicer cKO truly caused by depletion of mature miRs? and (2) Are miRs the only Dicer products in the skin? To address these questions, researchers engineered the equivalent K14-Cre-driven cKO of Dgcr8, thereby targeting an essential nuclear cofactor for miR processing. Moreover, while Dicer has been reported to control the processing of both miRs- and mRNA-derived small RNAs (Babiarz et al., 2008; Tam et al., 2008; Watanabe et al., 2008), Dgcr8 is specific for stereotypical miRs (Babiarz et al., 2008; Yi et al., 2009).

When comparing the number of deep sequencing reads that can be mapped to different classes of small RNAs, stereotypical miRs emerged as the most abundant species in the skin (Yi et al., 2009). In comparing the reads between the K14-Cre X Dicer and K14-Cre X Dgcr8 cKO skins, the production of the overwhelming majority of miRs was dependent upon both Dicer and Dgcr8, while only a few hairpin miR- and mRNA-derived small RNAs showed dependency only upon Dicer and not Dgcr8 (Yi et al., 2009).

Most importantly, both Dicer and Dgcr8 skin cKO animals displayed indistinguishable phenotypes including evaginating HFs, enriched apoptosis in hair bulbs, rough and dehydrated skin, and neonatal lethality. Thus, these results confirmed that the previously reported Dicer cKO skin phenotypes (Andl et al., 2006; Yi et al., 2006) were indeed bona fide consequences of the loss of miRs in the skin and firmly established that stereotypical miRs are the key Dicer products in skin.

7. Dissecting the Complexities of the Differential Expression of miRs in Skin

By investigating Dicer and Dgcr8 skin cKOs, the global importance of miRs in skin development was established and the differential effects on the epidermis versus HF pointed to a physiological relevance to their differential expression. With this information at hand, the next step was to begin to unearth the functions of individual miRs in the skin.

miR-203 is highly expressed in a spatiotemporal-specific manner in vertebrate epidermis (Aberdam et al., 2008; Lena et al., 2008; Sonkoly et al., 2007; Yi et al., 2008), rendering it an obvious first choice for exploring the functional significance of an individual miR in the skin. In situ hybridizations revealed miR-203 in the differentiating suprabasal and not the basal progenitors of the epidermis (Yi et al., 2009), making it tempting to speculate that the hyperproliferative epidermal phenotype observed in the Dicer cKO skin (Andl et al., 2006; Yi et al., 2006, 2008) might be attributable specifically to the loss of miR-203.

Functional studies revealed miR-203's ability to unleash its potent inhibitory powers on proliferative potential. When miR-203 was precociously expressed in the epidermal stem/progenitor cells either in vivo or in vitro, keratinocytes exited the cell cycle and displayed significantly reduced capacity to form colonies (Lena et al., 2008; Yi et al., 2008). Conversely, when epidermal cells or neonatal mice were treated with the chemically modified antisense oligonucleotide (antagomir) against miR-203, an increase was observed in actively dividing cells within the suprabasal epidermal layers (Yi et al., 2008). Consistent with its function in inhibiting cell proliferation in mammalian skin, miR-203 potently inhibited the growth of the repairing fin when overexpressed in Zebrafish skin (Thatcher et al., 2008).

To understand how miR-203 exerts these effects, it is critical to know its physiological targets. Although systematic and unbiased target identification approaches are yet to be established, a few miR-203 targets have now been documented (Lena et al., 2008; Yi et al., 2008). The best characterized is the transcription factor ΔNp63α (also known as p73-like in human). Over the past decade, ΔNp63α has been extensively investigated for its essential function in the maintenance of “stemness” in the skin and in other stratified epithelia (Mills et al., 1999; Senoo et al., 2007; Yang et al., 1999). Intriguingly and in a fashion expected of a miR's action on its targets, ΔNp63α and miR-203 have mutually exclusive expression patterns, opposite functions, and evolutionarily conserved regulatory relationships (Yi et al., 2008).

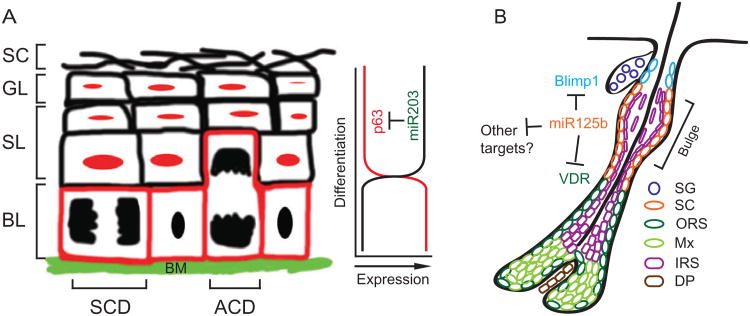

Importantly in the miR-203 gain- and loss-of-function studies, ΔNp63α was diminished when miR-203 was prematurely expressed basally, and conversely, ΔNp63α expanded aberrantly into the suprabasal layers when animals were treated with miR-203 antagomir (Yi et al., 2008). Although it is not yet clear whether ΔNp63α is the only target that mediates the function of miR-203, this study provided an important example of miR's ability to sharpen a developmental transition by targeting a master stem cell regulator at the juncture at which they become induced to differentiate (Yi et al., 2008) (Fig. 7.4A).

Figure 7.4.

Two distinct models for miR's functions in skin stem cells. (A) Reciprocal spatial expression of miR-203 and its target, p63, in the epidermis. In the basal stem cells (BL), p63 is highly expressed to maintain the stemness. Upon differentiation, miR-203 is rapidly upregulated to repress p63 expression in the suprabasal layers including spinous (SL) and granular (GL) layers. (B) miR-125b fine-tunes the input of hair follicle stem cells into sebaceous gland and hair follicle lineages by targeting Blimp1 and VDR, respectively.

An additional note of intrigue is that whereas miR-203 potently repressed epidermal stem cell proliferation, many structural markers of terminal differentiation were not ectopically activated in the stem cells when miR-203 was precociously expressed (Yi et al., 2008). Thus in this case, the exit of somatic stem cell cycling and the induction of terminal differentiation appeared to be regulated by distinct mechanisms. This model is in a close agreement with the paradigm established by the lin-4 and let-7 studies in C. elegans where miRs function to promote developmental transitions by inhibiting key molecules that are required for early developmental stages, but which must later be downregulated to progress through the differentiation program.

8. miR-203 as a Tumor Suppressor?

Because of the potent inhibition of miR-203 to cell proliferation, miR-203 might be expected to function as a tumor suppressor. Indeed, miR-203 was induced in a head and neck squamous cell carcinoma cell line exposed to UVC irradiation, a treatment that results in cell death and cell cycle exit (Lena et al., 2008). Conversely, an elegant study in human hematopoietic tumors revealed that frequent silencing of miR-203 either genetically or epigenetically is correlated with T cell lymphomas (Bueno et al., 2008). Moreover, forced expression of miR-203 directly resulted in the downregulation of the oncogene, BCR-ABL1, and blocked cancer cell proliferation (Bueno et al., 2008). Oddly, however, and in contrast to the epidermis, miR-203 is not detected in normal T cell lineages (Landgraf et al., 2007; Neilson et al., 2007; Wu et al., 2007). Even more paradoxical are the findings that miR-203 is upregulated in psoriasis, a common human hyperproliferative skin disease involving a proinflammatory response, and in a few epithelial tumors (Bandres et al., 2006; Gottardo et al., 2007; Iorio et al., 2007; Sonkoly et al., 2007; Szafranska et al., 2007). While further studies will be necessary to reconcile these differences, one possibility is that the expression of miR-203 can be independently induced under stress conditions, for example, cancer, psoriasis, or other diseases, perhaps as a negative and in some cases futile feedback mechanism to suppress the proliferative state.

A final interesting twist to the possible tumor suppressive roles of miR-203 comes from recent studies on the human papillomaviruses (HPVs), which do not encode their own miRs (Cai et al., 2006) but do modulate expression of cellular miRNAs to regulate the activities of cellular proteins. Recently, it was discovered that one of HPV's two oncoproteins, E7, downregulates miR-203 expression upon epidermal differentiation (Melar-New and Laimins, 2010), while the other, E6, downregulates miR-203 by compromising p53 function (McKenna et al., 2010). Moreover, HPV-positive cells maintain significantly higher levels of ΔNp63α than normal keratinocytes do, and when miR-203 was introduced into keratinocytes that stably maintain HPV episomes, the HPV was rapidly lost upon subsequent passage. Together, these findings suggest that miR-203 is inhibitory to HPV amplification and that HPV oncoproteins act in part by suppressing miR-203 in differentiating cells to disrupt the balance between proliferation and differentiation and allow productive HPV replication and propagation.

9. Characterizing and Defining the Functions of Specific miRs that are Differentially Expressed by HF Stem Cells

Most recently, a study for miR in HF stem cells provides another dimension to miR function. MiR-125b, a lin-4 homologue, was identified as a markedly upregulated miR in HF stem cells relative to any of the three other proliferating compartments within the skin epithelium (Zhang et al., 2011). Moreover, as judged by in situ hybridizations, miR-125b rapidly waned once stem cells exited their niche and became ORS progenitors. Thereafter, miR-125b remained off as ORS cells progressed further to become the matrix cells (Zhang et al., 2011).

To understand how this switch in miR-125b expression relates to the ability of SCs to embark upon the HF lineage, Zhang and Fuchs took a doxycycline (tetracycline) inducible, transgenic strategy and sustained miR-125b expression in the proliferative progeny of HF-SCs. The outcome was a shift in the balance between the stem cells and their committed progeny. Thus, when the HF-SCs were unable to downregulate miR-125b, the upper ORS became hyperthickened with cells that appeared to be uncommitted HF-SCs. Similarly, the entire process of lineage progression appeared to be delayed when miR-125b could not be properly downregulated (Zhang et al., 2011). The overall outcome was eventual baldness. Similarly, the SG progenitors were expanded as a consequence of miR-125b overexpression, leading to enlarged SGs.

Intriguingly, the maintenance of HF-SCs and SG progenitors appeared to be intact, as upon withdrawal of doxycycline, the block to differentiation was lifted and HFs and SGs were restored even after up to 4 months of continuous miR-125b induction (Zhang et al., 2011). These observations suggest a new model for the role of miRs in stem cells, namely, as a rheostat to precisely govern their input into the differentiation program (Fig. 7.4B).

In C. elegans, one of lin-4′s major targets is lin-28, which binds endogenous primary let-7 transcripts and blocks its biogenesis into a miR. Although let-7 is expressed by skin progenitors, lin-28 is not expressed anywhere in the normal skin epithelium, suggesting that miR-125b/lin4 in the HF-SCs must have other targets besides lin-28, and that let-7 must be regulated by mechanisms that go beyond lin-28 (Zhang et al., 2011). Microarray profiling of miR-125b-induced skin epithelium and subsequent target analyzes revealed several downstream targets that could explain the phenotype: the VdR gene encoding the vitamin D receptor, whose ablation results in baldness (Li et al., 1997; Palmer et al., 2008) and the Blimp1 gene encoding a transcriptional repressor of c-Myc, whose ablation results in SG enlargement (Horsley et al., 2006). Interestingly, both VdR and Blimp1 have been identified as miR-125b targets in other cell types and tissues (Gururajan et al., 2010; Malumbres et al., 2009; Mohri et al., 2009). That said, the skin phenotype of the miR-125b-induced mouse is complex, and additional targets are likely to be involved. Future studies will be needed to address these issues.

10. Delving Further into miR Functions in Stem Cells: The Hematopoietic System

Hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs), with their well-defined cell lineages, offer an ideal system to map the lineage-specific expression patterns of miRs and decipher their roles in differentiation. In one of the earliest studies of mammalian miRs, miR-181, miR-223, and miR-142 were all found to be upregulated when bone marrow progenitor cells differentiate toward B lymphocytes (Chen et al., 2004). Moreover, forced expression of miR-181 in those progenitors enhanced B-lymphoid development at the expense of T-lymphoid differentiation. In another important study, it was discovered that miR-155 is expressed in mature B and T lymphocytes, and that it is also significantly upregulated in a variety of lymphomas (Eis et al., 2005). Loss-of-function studies in mice revealed that miR-155 is a critical in vivo regulator of specific differentiation processes in the immune response (Rodriguez et al., 2007; Thai et al., 2007).

In an effort to identify miR-155 targets, upregulated mRNAs in miR-155 null T lymphocytes were analyzed for the presence of seed matches to miR-155 (Rodriguez et al., 2007). Even though ∼65% of the upregulated genes contained miR-155 seed matches in their 3′UTRs, the key miR-155 targets appeared to be mRNAs encoding cytokines, providing an explanation for the remarkable impact and specificity of this miR on immune cell lineages.

Another elegant study of hematopoietic-specific miRs focused on miR-150 and provided an example of a single mRNA:miR regulatory pair that functions critically in lymphocyte development (Xiao et al., 2007). Like miR-155, miR-150 is primarily expressed in mature lymphocytes rather than the progenitor cells. By loss- and gain-of-function studies, miR-150 was shown to regulate lymphocyte terminal differentiation (Xiao et al., 2007). Importantly, the expression of c-Myb, a key transcription factor and the top predicted target of miR-150, inversely correlates with that of miR-150, suggesting that miR-150 might be both necessary and sufficient to control c-Myb expression. Interestingly, the ensuing c-Myb heterozygous KO mouse showed phenotypes similar to those observed in a miR-150 transgenic mouse, lending support to the argument that miR-150 carries out its function through the accurate control of c-Myb expression (Xiao et al., 2007).

Similar to miR-150 and miR-155, miR-223 is also expressed at a low level in the HSCs but gradually upregulated during the differentiation toward mature peripheral blood granulocytes (Johnnidis et al., 2008). When genetically ablated, miR-223 KO mice have an increased population of granulocyte progenitors. This phenotype is likely due to the derepression of one of miR-223 direct targets, Mef2c, a transcription factor that promotes proliferation of the myeloid progenitors. Remarkably, when the miR-223 KO mice were across to Mef2c KO mice, the loss of Mef2c was able to repress the enhanced progenitor proliferation. This result strongly suggests that the downregulation of Mef2c by miR-223 during granulocyte differentiation is important to suppress the proliferative capacity of the differentiating progenitors. It is also interesting that although Mef2c is dispensable for the hematopoietic homeostasis, its regulation by miR-223 appears to be critical to modulate the pool of progenitor cells during the granulocytic differentiation.

Studies of the erythroid lineage have also revealed an inverse relationship between miR expression and progenitor. When erythroid progenitors begin to differentiate into red blood cells, the miR-144/miR-451 locus is directly activated by a key erythroid transcription factor, Gata-1 (Dore et al., 2008). Loss-of-function studies in both Zebrafish and mouse revealed that this conserved miR locus is required for erythroblast maturation (Dore et al., 2008; Rasmussen et al., 2010). Interestingly, the mRNA of 14-3-3ζ, a key regulator of cytokine signaling, was identified as a direct target of miR-451. More importantly, knocking down 14-3-3ζ in miR-451 null HSCs rescued these defects during erythroid differentiation in vitro, providing another example where a single target may be primarily responsible for mediating the effects of a miR in a defined cellular context (Patrick et al., 2010; Yu et al., 2010).

11. miR Function in Neural Stem Cells

In the adult brain, Dicer ablation results in massive hypotrophy of the cortex due to neuronal apoptosis, accompanied by a dramatic impairment of neuronal differentiation (De Pietri Tonelli et al., 2008). Remarkably, the neuroepithelial cells and the neurogenic progenitors derived from them were not grossly affected by depletion of Dicer, suggesting that like the epidermis, the progenitors are less dependent on miRNAs than their differentiated progeny.

miR-9 is interesting in that it is expressed specifically in the subventricular zone (SVZ) of the brain known to harbor the neural stem cells (NSCs). However, miR-9 appears to negatively regulate NSC proliferation and accelerate neural differentiation (Zhao et al., 2009). Intriguingly, TLX, requisite for NSC self-renewal, is a target for miR-9, but, in turn, it also antagonizes miR-9's expression by directly reducing the transcription of pri-miR-9 (Zhao et al., 2009). Thus, TLX and miR-9 form a negative feedback regulatory network to balance both proliferation and differentiation of NSCs. In this regard, miR-9's effects on NSCs appear to be distinct from the effects of either miR-125b or miR-203 on skin SCs.

In contrast, miR-124, one of the most specific and abundant miRs in the brain, more closely mirrors the behavior of miR-203 in skin. Like miR-203, miR-124 is expressed at low levels in the SVZ stem cell compartment but is sharply upregulated in mature granule and periglomerular neurons (Cheng et al., 2009). Similarly, gain-of-function of miR-124 induces cell cycle exit, while inhibition of miR-124 by antagomir in vivo results in an increase in the population of precursor cells in the SVZ. Moreover, Sox9, a key transcription factor whose downregulation is required for neural differentiation, has been identified as a direct target of miR-124 (Cheng et al., 2009). In this regard, the effect of miR-124 on NSCs seems to be a mirror image of those of miR-125b on HF-SCs.

Finally, it is worth mentioning that miRs have also been implicated in the regulation of stem cell aging. Hmga2, a key transcription factor for the self-renewal of several types of stem cells, is highly expressed in fetal NSCs, but its levels decline by more than 99% during the mouse's lifespan (Nishino et al., 2008). This decline in Hmga2 is accompanied by a reduction in self-renewal capacity of NSCs and appears to be in part caused by a ∼30-fold age-induced increase in the miR let-7b, known to target and inhibit Hmga2 expression (Mayr et al., 2007; Nishino et al., 2008). The specific disruption of Hmga2 regulation with a truncated 3′UTR refractory to let-7 targeting resulted in a significant rescue of the self-renewal capacity in an in vitro culture assay, supporting the causative role of let-7b in the downregulation of Hmga2 expression (Nishino et al., 2008).

12. miR Function in Muscle Stem Cells

A recent study of skeletal muscle satellite cells provides another interesting parallel to that of the skin stem cell lineages. Pax7 is a critical transcription factor that is highly expressed in quiescent muscle stem (satellite) cells and is required to maintain the stem cell population. Upon injury, satellite stem cells are activated to repair the wound, and Pax7 is concomitantly downregulated to allow these cells to progress to differentiate and contribute to muscle regeneration. Both miR-1 and miR-206 target Pax7 mRNA and are markedly upregulated concomitant with downregulation of Pax7 and satellite cell differentiation (Chen et al., 2010). Conversely, specific inhibition of miR-1 and miR-206 by antagomirs delays Pax7 downregulation and interferes with the differentiation program (Chen et al., 2010). Overall, such findings are remarkably similar to the role of miR-203 in regulating ΔNp63α in epidermal stem cells (Yi et al., 2008) and together, point to the view that a number of somatic miRs expressed at the transition between the stem cells and their differentiation lineage function in fine-tuning the switch.

13. miR Function in Cancer Stem Cells

The role of miRs extends beyond normal development and is particularly intriguing in human cancer. The miR pathway is often dampened in tumor cells (Lu et al., 2005). Indeed, reduced miR expression in Dicer heterozygous animals has been shown a causative role in driving tumorigenesis and cellular transformation in several mouse models (Kumar et al., 2009), and in the skin, the hyperproliferative epidermal phenotype is suggestive of an increased sensitivity (Andl et al., 2006). In addition, the shortening of 3′UTRs of proto-oncogenes in cancer cell lines has been found to enable the mRNA to escape the repression by miRs and result in oncogene activation (Mayr and Bartel, 2009). Together, these studies raise the hypothesis that the miR pathway often functions in tumor suppression, as suggested earlier in this review.

It is also interesting that let-7 miRs appear to be powerful tumor suppressors in their ability to target multiple critical oncogenes including RAS, c-Myc, Hmga2, and Lin28 (Johnson et al., 2005; Mayr et al., 2007; Roush and Slack, 2008; Viswanathan et al., 2009). Several miRs that are highly expressed in normal skin, including miR-200 and miR-205, have also been implicated in epithelial cancers. Both miR-200 miRs and miR-205 are highly expressed in normal skin, where they specifically target the expression of the mRNAs encoding transcriptional repressors of E-cadherin, ZEB1, and ZEB2 (Christoffersen et al., 2007; Gregory et al., 2008; Korpal et al., 2008; Park et al., 2008). By doing so, miR-200 and miR-205 promote the upregulated expression of the intercellular adhesion protein E-cadherin. Conversely, downregulation of the miR-200 family or miR-205 leads to the inhibition of E-cadherin, thereby promoting an epithelial–mesenchymal transition (Gregory et al., 2008; Korpal et al., 2008; Park et al., 2008). Consistent with these studies, miR-205 is often significantly downregulated in human epithelial tumors when comparing to the normal tissues (Childs et al., 2009; Feber et al., 2008). That said, there are profiling studies of human epithelial cancers, where miR-200 family and/or miR-205 were found to be upregulated (Iorio et al., 2007; Tran et al., 2007; Yu et al., 2008). These apparently contrasting results suggest that miRs may have different targets and roles in different cells.

The identification of cancer stem cells in numerous tumors including those derived from brain, breast, prostate, colon, head and neck, pancreas, and skin necessitates an investigation into the underlying molecular mechanisms involved. Given the diversity of miR expression patterns and functions, it is perhaps not surprising that miRs are critically involved in cancer stem cells. For instance, in the tumor initiating cells of breast cancer, let-7 is significantly downregulated to allow the expression of H-Ras and Hmga2 (Yu et al., 2007). Forced expression of let-7 in the tumor initiating cells inhibits self-renewal through the downregulation of H-Ras and promotes differentiation by repressing Hmga2 (Yu et al., 2007). Similarly, miR-34a, a miR transcriptionally activated by p53 (He et al., 2007), functions to inhibit clonogenic expansion of prostate cancer stem cells and metastasis by directly repressing CD44 (Liu et al., 2011). In breast cancer stem cells, the miR-200 family members including miR-200b and miR-200c have multiple functions in restricting tumor development, including repressing self-renewal by repressing a key polycomb protein complex 1 (PRC1) member, BMI1 (Shimono et al., 2009; Wellner et al., 2009). These miRs also play important roles in EMTs (Wellner et al., 2009), as well as repress a key epigenetic component of the PRC2 complex, Suz12, which together with PRC1 functions in epigenetic silencing of genes through H3K27me3 trimethylation (Iliopoulos et al., 2010).

Together, these findings provide critical mechanisms that link miRs to cancer stem cells. Recently, a chemical screen specifically targeting breast cancer stem cells led to the identification of compounds that are particular effective to reduce the cancer stem cell population (Gupta et al., 2009). With the emerging roles of miRs in cancer stem cells, it is tempting to speculate that studies specifically focusing on miRs in these often rare cell populations could yield novel insights toward diagnosis and treatment in the future.

14. Closing Remarks and Future Challenges

Functional characterization of miRs in mammalian development and adult stem cells is still in its infancy. Much of our knowledge of the just how critical miRs are to mammalian development can still be traced to the global miR depletion studies in which Dicer and Dgcr8 were ablated specifically in either embryonic stem cells or adult tissues. The strong defects in differentiation and minor defects in proliferation appear to be a recurring theme, whether for embryonic or adult SCs (Kanellopoulou et al., 2005; Murchison et al., 2005; Wang et al., 2007). However, ESCs and adult tissues do show some notable differences, for instance, those showing that the differences between Dicer- and Dgcr8-deficient ESCs and mouse oocytes are significantly greater than for skin lineages (Suh et al., 2010; Wang et al., 2007). That said, it is notable that endo-siRNAs, accounting for much of the difference between Dicer and Dgcr8 null phenotypes, have only been detected in ESCs and oocytes and not in adult tissues in mammals (Babiarz et al., 2011; Suh et al., 2010; Tam et al., 2008; Watanabe et al., 2008). In this regard, it is also interesting to note that lin-28, a key downstream target of lin-4 in C. elegans, is also primarily restricted to mammalian ESCs and is generally not seen in adult SCs. Whether these differences are reflective of the unique pluripotent state of the ESCs remains to be addressed in the future.

Among the myriad of key issues that remain unresolved is the question regarding the role of a single miR or miR family in the regulation of mammalian development and stem cells. When C. elegans miRs are knocked out individually or by the whole family that share the same seed sequences combinatorially, only a few exhibit developmental defects (Alvarez-Saavedra and Horvitz, 2010; Miska et al., 2007). Similarly, with more than 30 miRs having been individually knocked out to date without affecting viability in mice, it is evident that the loss of a single miR or even a whole family might not cause the severe developmental defects in cell fate specification that would be expected from ablation of a gene encoding a master regulator. However, when these mutant mice are subject to physiological stresses like injury or DNA damage, significant phenotypes surface (reviewed by Leung and Sharp, 2010; Liu and Olson, 2010). These observations are yet further indicators that miR-mediated regulation functions by fine-tuning responses and reinforcing the robustness of biological systems that may not be readily manifested in a well-maintained laboratory condition (reviewed by Herranz and Cohen, 2010). It is worth noting that because of the central role of stem cells during the development and homeostasis of adult tissues, dysregulation in stem cells could be magnified and manifested as defects in their differentiated daughters. This illustrates a critical need for the future to investigate how stress signals regulate miR expression and how miR-mediated regulation, in turn, balances the output of gene expression and protects stem cells from the various and diverse stresses that they encounter throughout the life.

A second key issue to address will be how a single miR can execute its physiological function by regulating its targets. Directly related to this is the question whether a single miR can perform different roles when placed in distinct cellular contexts. As miR functions in mammalian stem cells begin to unfold, some of the most challenging questions to be answered will be which mRNAs are targeted by a specific miR and which of its many targets are key in a given cellular context.

A third key area to be addressed in the future is the question of how miR-mediated regulation integrates with other regulatory mechanisms, for example, transcriptional regulation, to modulate stem cell fate. Although biologists now appreciate the importance of the regulatory layer provided by miRs, the interactions between the miR pathway and other regulatory mechanisms must be elucidated to fully understand how miRs work. Further, it will be important to unveil the characteristics of the miR pathway that are distinct from other mechanisms such as cellular context-dependent function.

Finally, miR's functions in human diseases especially cancer are particularly intriguing. Because miRs' functions are highly dependent upon local mRNA content, it is conceivable that their functions in cancer cells could dramatically differ from their functions during normal development. Thus, characterization of individual miRs' roles at different stage of tumorigenesis will be important to understand the underlying biology of tumor development. In particular, because of the central roles of cancer stem cells in tumor development and relapse, it is critical to focus on miR-mediated regulation in these cells. Answers to these fascinating questions are certainly not only going to provide significant new insights into miR functions but also point to new directions to utilize and target miRs in the manipulation of stem cells for regenerative medicine as well as in the development of cancer therapies.

Acknowledgments

This publication was made possible by grants R00AR054704 and R01AR059697 (to R. Y.), and R01AR031737 (to E. F.) from NIAMS/NIH. E. F. is a Howard Hughes Medical Institute Investigator.

References

- Aberdam D, Candi E, Knight RA, Melino G. Trends Biochem Sci. 2008;33:583–591. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2008.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alvarez-Saavedra E, Horvitz HR. Curr Biol. 2010;20:367–373. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2009.12.051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ambros V. Nature. 2004;431:350–355. doi: 10.1038/nature02871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andl T, Murchison EP, Liu F, Zhang Y, Yunta-Gonzalez M, Tobias JW, Andl CD, Seykora JT, Hannon GJ, Millar SE. Curr Biol. 2006;16:1041–1049. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2006.04.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Babiarz JE, Ruby JG, Wang Y, Bartel DP, Blelloch R. Genes Dev. 2008;22:2773–2785. doi: 10.1101/gad.1705308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Babiarz JE, Hsu R, Melton C, Thomas M, Ullian EM, Blelloch R. RNA. 2011;17:1489–1501. doi: 10.1261/rna.2442211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baek D, Villen J, Shin C, Camargo FD, Gygi SP, Bartel DP. Nature. 2008;455:64–71. doi: 10.1038/nature07242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bandres E, Cubedo E, Agirre X, Malumbres R, Zarate R, Ramirez N, Abajo A, Navarro A, Moreno I, Monzo M, Garcia-Foncillas J. Mol Cancer. 2006;5:29. doi: 10.1186/1476-4598-5-29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartel DP. Cell. 2009;136:215–233. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein E, Kim SY, Carmell MA, Murchison EP, Alcorn H, Li MZ, Mills AA, Elledge SJ, Anderson KV, Hannon GJ. Nat Genet. 2003;35:215–217. doi: 10.1038/ng1253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borchert GM, Lanier W, Davidson BL. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2006;13:1097–1101. doi: 10.1038/nsmb1167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brenner JL, Jasiewicz KL, Fahley AF, Kemp BJ, Abbott AL. Curr Biol. 2010;20:1321–1325. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2010.05.062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bueno MJ, Perez de Castro I, Gomez de Cedron M, Santos J, Calin GA, Cigudosa JC, Croce CM, Fernandez-Piqueras J, Malumbres M. Cancer Cell. 2008;13:496–506. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2008.04.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Byrne C, Tainsky M, Fuchs E. Development. 1994;120:2369–2383. doi: 10.1242/dev.120.9.2369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai X, Hagedorn CH, Cullen BR. RNA. 2004;10:1957–1966. doi: 10.1261/rna.7135204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai X, Li G, Laimins LA, Cullen BR. J Virol. 2006;80:10890–10893. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01175-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen CZ, Li L, Lodish HF, Bartel DP. Science. 2004;303:83–86. doi: 10.1126/science.1091903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen JF, Tao Y, Li J, Deng Z, Yan Z, Xiao X, Wang DZ. J Cell Biol. 2010;190:867–879. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200911036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng LC, Pastrana E, Tavazoie M, Doetsch F. Nat Neurosci. 2009;12:399–408. doi: 10.1038/nn.2294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Childs G, Fazzari M, Kung G, Kawachi N, Brandwein-Gensler M, McLemore M, Chen Q, Burk RD, Smith RV, Prystowsky MB, Belbin TJ, Schlecht NF. Am J Pathol. 2009;174:736–745. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2009.080731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christodoulou F, Raible F, Tomer R, Simakov O, Trachana K, Klaus S, Snyman H, Hannon GJ, Bork P, Arendt D. Nature. 2010;463:1084–1088. doi: 10.1038/nature08744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christoffersen NR, Silahtaroglu A, Orom UA, Kauppinen S, Lund AH. RNA. 2007;13:1172–1178. doi: 10.1261/rna.586807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Pietri Tonelli D, Pulvers JN, Haffner C, Murchison EP, Hannon GJ, Huttner WB. Development. 2008;135:3911–3921. doi: 10.1242/dev.025080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denli AM, Tops BB, Plasterk RH, Ketting RF, Hannon GJ. Nature. 2004;432:231–235. doi: 10.1038/nature03049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dore LC, Amigo JD, Dos Santos CO, Zhang Z, Gai X, Tobias JW, Yu D, Klein AM, Dorman C, Wu W, Hardison RC, Paw BH, et al. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:3333–3338. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0712312105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eis PS, Tam W, Sun L, Chadburn A, Li Z, Gomez MF, Lund E, Dahlberg JE. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:3627–3632. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0500613102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farh KK, Grimson A, Jan C, Lewis BP, Johnston WK, Lim LP, Burge CB, Bartel DP. Science. 2005;310:1817–1821. doi: 10.1126/science.1121158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feber A, Xi L, Luketich JD, Pennathur A, Landreneau RJ, Wu M, Swanson SJ, Godfrey TE, Litle VR. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2008;135:255–260. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2007.08.055. discussion 260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedman RC, Farh KK, Burge CB, Bartel DP. Genome Res. 2009;19:92–105. doi: 10.1101/gr.082701.108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gangaraju VK, Lin H. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2009;10:116–125. doi: 10.1038/nrm2621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gottardo F, Liu CG, Ferracin M, Calin GA, Fassan M, Bassi P, Sevignani C, Byrne D, Negrini M, Pagano F, Gomella LG, Croce CM, et al. Urol Oncol. 2007;25:387–392. doi: 10.1016/j.urolonc.2007.01.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gregory RI, Yan KP, Amuthan G, Chendrimada T, Doratotaj B, Cooch N, Shiekhattar R. Nature. 2004;432:235–240. doi: 10.1038/nature03120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gregory PA, Bert AG, Paterson EL, Barry SC, Tsykin A, Farshid G, Vadas MA, Khew-Goodall Y, Goodall GJ. Nat Cell Biol. 2008;10:593–601. doi: 10.1038/ncb1722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grimson A, Srivastava M, Fahey B, Woodcroft BJ, Chiang HR, King N, Degnan BM, Rokhsar DS, Bartel DP. Nature. 2008;455:1193–1197. doi: 10.1038/nature07415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta PB, Onder TT, Jiang G, Tao K, Kuperwasser C, Weinberg RA, Lander ES. Cell. 2009;138:645–659. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.06.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gururajan M, Haga CL, Das S, Leu CM, Hodson D, Josson S, Turner M, Cooper MD. Int Immunol. 2010;22:583–592. doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxq042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han J, Lee Y, Yeom KH, Kim YK, Jin H, Kim VN. Genes Dev. 2004;18:3016–3027. doi: 10.1101/gad.1262504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harfe BD, McManus MT, Mansfield JH, Hornstein E, Tabin CJ. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:10898–10903. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0504834102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He L, He X, Lim LP, de Stanchina E, Xuan Z, Liang Y, Xue W, Zender L, Magnus J, Ridzon D, Jackson AL, Linsley PS, et al. Nature. 2007;447:1130–1134. doi: 10.1038/nature05939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herranz H, Cohen SM. Genes Dev. 2010;24:1339–1344. doi: 10.1101/gad.1937010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horsley V, O'Carroll D, Tooze R, Ohinata Y, Saitou M, Obukhanych T, Nussenzweig M, Tarakhovsky A, Fuchs E. Cell. 2006;126:597–609. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.06.048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hutvagner G, McLachlan J, Pasquinelli AE, Balint E, Tuschl T, Zamore PD. Science. 2001;293:834–838. doi: 10.1126/science.1062961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iliopoulos D, Lindahl-Allen M, Polytarchou C, Hirsch HA, Tsichlis PN, Struhl K. Mol Cell. 2010;39:761–772. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.08.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iorio MV, Visone R, Di Leva G, Donati V, Petrocca F, Casalini P, Taccioli C, Volinia S, Liu CG, Alder H, Calin GA, Menard S, et al. Cancer Res. 2007;67:8699–8707. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-1936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ivey KN, Srivastava D. Cell Stem Cell. 2010;7:36–41. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2010.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnnidis JB, Harris MH, Wheeler RT, Stehling-Sun S, Lam MH, Kirak O, Brummelkamp TR, Fleming MD, Camargo FD. Nature. 2008;451:1125–1129. doi: 10.1038/nature06607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson SM, Grosshans H, Shingara J, Byrom M, Jarvis R, Cheng A, Labourier E, Reinert KL, Brown D, Slack FJ. Cell. 2005;120:635–647. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.01.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanellopoulou C, Muljo SA, Kung AL, Ganesan S, Drapkin R, Jenuwein T, Livingston DM, Rajewsky K. Genes Dev. 2005;19:489–501. doi: 10.1101/gad.1248505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim VN, Han J, Siomi MC. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2009;10:126–139. doi: 10.1038/nrm2632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korpal M, Lee ES, Hu G, Kang Y. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:14910–14914. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C800074200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krol J, Loedige I, Filipowicz W. Nat Rev Genet. 2010;11:597–610. doi: 10.1038/nrg2843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar MS, Pester RE, Chen CY, Lane K, Chin C, Lu J, Kirsch DG, Golub TR, Jacks T. Genes Dev. 2009;23:2700–2704. doi: 10.1101/gad.1848209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landgraf P, Rusu M, Sheridan R, Sewer A, Iovino N, Aravin A, Pfeffer S, Rice A, Kamphorst AO, Landthaler M, Lin C, Socci ND, et al. Cell. 2007;129:1401–1414. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.04.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landthaler M, Yalcin A, Tuschl T. Curr Biol. 2004;14:2162–2167. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2004.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee RC, Feinbaum RL, Ambros V. Cell. 1993;75:843–854. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90529-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lena AM, Shalom-Feuerstein R, di Val Cervo PR, Aberdam D, Knight RA, Melino G, Candi E. Cell Death Differ. 2008;15:1187–1195. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2008.69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leung AK, Sharp PA. Mol Cell. 2010;40:205–215. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.09.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis BP, Burge CB, Bartel DP. Cell. 2005;120:15–20. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.12.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li YC, Pirro AE, Amling M, Delling G, Baron R, Bronson R, Demay MB. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:9831–9835. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.18.9831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu N, Olson EN. Dev Cell. 2010;18:510–525. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2010.03.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu C, Kelnar K, Liu B, Chen X, Calhoun-Davis T, Li H, Patrawala L, Yan H, Jeter C, Honorio S, Wiggins JF, Bader AG, et al. Nat Med. 2011;17:211–215. doi: 10.1038/nm.2284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu J, Getz G, Miska EA, Alvarez-Saavedra E, Lamb J, Peck D, Sweet-Cordero A, Ebert BL, Mak RH, Ferrando AA, Downing JR, Jacks T, et al. Nature. 2005;435:834–838. doi: 10.1038/nature03702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lund E, Guttinger S, Calado A, Dahlberg JE, Kutay U. Science. 2004;303:95–98. doi: 10.1126/science.1090599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malumbres R, Sarosiek KA, Cubedo E, Ruiz JW, Jiang X, Gascoyne RD, Tibshirani R, Lossos IS. Blood. 2009;113:3754–3764. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-10-184077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez NJ, Gregory RI. Cell Stem Cell. 2010;7:31–35. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2010.06.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayr C, Bartel DP. Cell. 2009;138:673–684. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.06.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayr C, Hemann MT, Bartel DP. Science. 2007;315:1576–1579. doi: 10.1126/science.1137999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKenna DJ, McDade SS, Patel D, McCance DJ. J Virol. 2010;84:10644–10652. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00703-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melar-New M, Laimins LA. J Virol. 2010;84:5212–5221. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00078-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mills AA, Zheng B, Wang XJ, Vogel H, Roop DR, Bradley A. Nature. 1999;398:708–713. doi: 10.1038/19531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miska EA, Alvarez-Saavedra E, Abbott AL, Lau NC, Hellman AB, McGonagle SM, Bartel DP, Ambros VR, Horvitz HR. PLoS Genet. 2007;3:e215. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.0030215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohri T, Nakajima M, Takagi S, Komagata S, Yokoi T. Int J Cancer. 2009;125:1328–1333. doi: 10.1002/ijc.24459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muljo SA, Ansel KM, Kanellopoulou C, Livingston DM, Rao A, Rajewsky K. J Exp Med. 2005;202:261–269. doi: 10.1084/jem.20050678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murchison EP, Partridge JF, Tam OH, Cheloufi S, Hannon GJ. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:12135–12140. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0505479102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakagawa A, Shi Y, Kage-Nakadai E, Mitani S, Xue D. Science. 2010;328:327–334. doi: 10.1126/science.1182374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neilson JR, Zheng GX, Burge CB, Sharp PA. Genes Dev. 2007;21:578–589. doi: 10.1101/gad.1522907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishino J, Kim I, Chada K, Morrison SJ. Cell. 2008;135:227–239. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.09.01. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palmer HG, Anjos-Afonso F, Carmeliet G, Takeda H, Watt FM. PLoS One. 2008;3:e1483. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0001483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park SM, Gaur AB, Lengyel E, Peter ME. Genes Dev. 2008;22:894–907. doi: 10.1101/gad.1640608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pasquinelli AE, Reinhart BJ, Slack F, Martindale MQ, Kuroda MI, Maller B, Hayward DC, Ball EE, Degnan B, Muller P, Spring J, Srinivasan A, et al. Nature. 2000;408:86–89. doi: 10.1038/35040556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patrick DM, Zhang CC, Tao Y, Yao H, Qi X, Schwartz RJ, Jun-Shen Huang L, Olson EN. Genes Dev. 2010;24:1614–1619. doi: 10.1101/gad.1942810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rasmussen KD, Simmini S, Abreu-Goodger C, Bartonicek N, Di Giacomo M, Bilbao-Cortes D, Horos R, Von Lindern M, Enright AJ, O'Carroll D. J Exp Med. 2010;207:1351–1358. doi: 10.1084/jem.20100458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reinhart BJ, Slack FJ, Basson M, Pasquinelli AE, Bettinger JC, Rougvie AE, Horvitz HR, Ruvkun G. Nature. 2000;403:901–906. doi: 10.1038/35002607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez A, Vigorito E, Clare S, Warren MV, Couttet P, Soond DR, van Dongen S, Grocock RJ, Das PP, Miska EA, Vetrie D, Okkenhaug K, et al. Science. 2007;316:608–611. doi: 10.1126/science.1139253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roush S, Slack FJ. Trends Cell Biol. 2008;18:505–516. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2008.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt-Ullrich R, Paus R. Bioessays. 2005;27:247–261. doi: 10.1002/bies.20184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwarz DS, Hutvagner G, Du T, Xu Z, Aronin N, Zamore PD. Cell. 2003;115:199–208. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00759-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selbach M, Schwanhausser B, Thierfelder N, Fang Z, Khanin R, Rajewsky N. Nature. 2008;455:58–63. doi: 10.1038/nature07228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Senoo M, Pinto F, Crum CP, McKeon F. Cell. 2007;129:523–536. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.02.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimono Y, Zabala M, Cho RW, Lobo N, Dalerba P, Qian D, Diehn M, Liu H, Panula SP, Chiao E, Dirbas FM, Somlo G, et al. Cell. 2009;138:592–603. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.07.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sonkoly E, Wei T, Janson PC, Saaf A, Lundeberg L, Tengvall-Linder M, Norstedt G, Alenius H, Homey B, Scheynius A, Stahle M, Pivarcsi A. PLoS One. 2007;2:e610. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0000610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stark A, Brennecke J, Bushati N, Russell RB, Cohen SM. Cell. 2005;123:1133–1146. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.11.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suh N, Baehner L, Moltzahn F, Melton C, Shenoy A, Chen J, Blelloch R. Curr Biol. 2010;20:271–277. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2009.12.044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szafranska AE, Davison TS, John J, Cannon T, Sipos B, Maghnouj A, Labourier E, Hahn SA. Oncogene. 2007;26:4442–4452. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tam OH, Aravin AA, Stein P, Girard A, Murchison EP, Cheloufi S, Hodges E, Anger M, Sachidanandam R, Schultz RM, Hannon GJ. Nature. 2008;453:534–538. doi: 10.1038/nature06904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thai TH, Calado DP, Casola S, Ansel KM, Xiao C, Xue Y, Murphy A, Frendewey D, Valenzuela D, Kutok JL, Schmidt-Supprian M, Rajewsky N, et al. Science. 2007;316:604–608. doi: 10.1126/science.1141229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thatcher EJ, Paydar I, Anderson KK, Patton JG. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:18384–18389. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0803713105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tran N, McLean T, Zhang X, Zhao CJ, Thomson JM, O'Brien C, Rose B. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2007;358:12–17. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2007.03.201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vassar R, Rosenberg M, Ross S, Tyner A, Fuchs E. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1989;86:1563–1567. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.5.1563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Viswanathan SR, Powers JT, Einhorn W, Hoshida Y, Ng TL, Toffanin S, O'Sullivan M, Lu J, Phillips LA, Lockhart VL, Shah SP, Tanwar PS, et al. Nat Genet. 2009;41:843–848. doi: 10.1038/ng.392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Medvid R, Melton C, Jaenisch R, Blelloch R. Nat Genet. 2007;39:380–385. doi: 10.1038/ng1969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Juranek S, Li H, Sheng G, Wardle GS, Tuschl T, Patel DJ. Nature. 2009;461:754–761. doi: 10.1038/nature08434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watanabe T, Totoki Y, Toyoda A, Kaneda M, Kuramochi-Miyagawa S, Obata Y, Chiba H, Kohara Y, Kono T, Nakano T, Surani MA, Sakaki Y, et al. Nature. 2008;453:539–543. doi: 10.1038/nature06908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wellner U, Schubert J, Burk UC, Schmalhofer O, Zhu F, Sonntag A, Waldvogel B, Vannier C, Darling D, zur Hausen A, Brunton VG, Morton J, et al. Nat Cell Biol. 2009;11:1487–1495. doi: 10.1038/ncb1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wightman B, Ha I, Ruvkun G. Cell. 1993;75:855–862. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90530-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu H, Neilson JR, Kumar P, Manocha M, Shankar P, Sharp PA, Manjunath N. PLoS One. 2007;2:e1020. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0001020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao C, Calado DP, Galler G, Thai TH, Patterson HC, Wang J, Rajewsky N, Bender TP, Rajewsky K. Cell. 2007;131:146–159. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.07.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie X, Lu J, Kulbokas EJ, Golub TR, Mootha V, Lindblad-Toh K, Lander ES, Kellis M. Nature. 2005;434:338–345. doi: 10.1038/nature03441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang A, Schweitzer R, Sun D, Kaghad M, Walker N, Bronson RT, Tabin C, Sharpe A, Caput D, Crum C, McKeon F. Nature. 1999;398:714–718. doi: 10.1038/19539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yi R, Qin Y, Macara IG, Cullen BR. Genes Dev. 2003;17:3011–3016. doi: 10.1101/gad.1158803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yi R, O'Carroll D, Pasolli HA, Zhang Z, Dietrich FS, Tarakhovsky A, Fuchs E. Nat Genet. 2006;38:356–362. doi: 10.1038/ng1744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yi R, Poy MN, Stoffel M, Fuchs E. Nature. 2008;452:225–229. doi: 10.1038/nature06642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yi R, Pasolli HA, Landthaler M, Hafner M, Ojo T, Sheridan R, Sander C, O'Carroll D, Stoffel M, Tuschl T, Fuchs E. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:498–502. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0810766105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu F, Yao H, Zhu P, Zhang X, Pan Q, Gong C, Huang Y, Hu X, Su F, Lieberman J, Song E. Cell. 2007;131:1109–1123. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.10.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu J, Ryan DG, Getsios S, Oliveira-Fernandes M, Fatima A, Lavker RM. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:19300–19305. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0803992105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu D, dos Santos CO, Zhao G, Jiang J, Amigo JD, Khandros E, Dore LC, Yao Y, D'Souza J, Zhang Z, Ghaffari S, Choi J, et al. Genes Dev. 2010;24:1620–1633. doi: 10.1101/gad.1942110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang L, Stokes N, Polak L, Fuchs E. Cell Stem Cell. 2011;8:294–308. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2011.01.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao C, Sun G, Li S, Shi Y. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2009;16:365–371. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]