Abstract

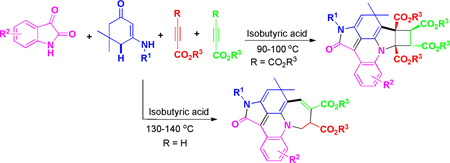

Highly selective four-component domino multi-cyclizations for the synthesis of new fused acridines and azaheterocyclic skeletons have been established by mixing common reactants in isobutyric acid under microwave irradiation. The reactions proceeded at fast rates, and were conducted to completion within 20–30 min. Up to seven new chemical bonds, four rings and four stereocenters were assembled in a convenient one-pot operation. The resulting hexacyclic and pentacyclic fused acridines and their stereochemistry have been fully characterized and determined by X-ray structural analysis.

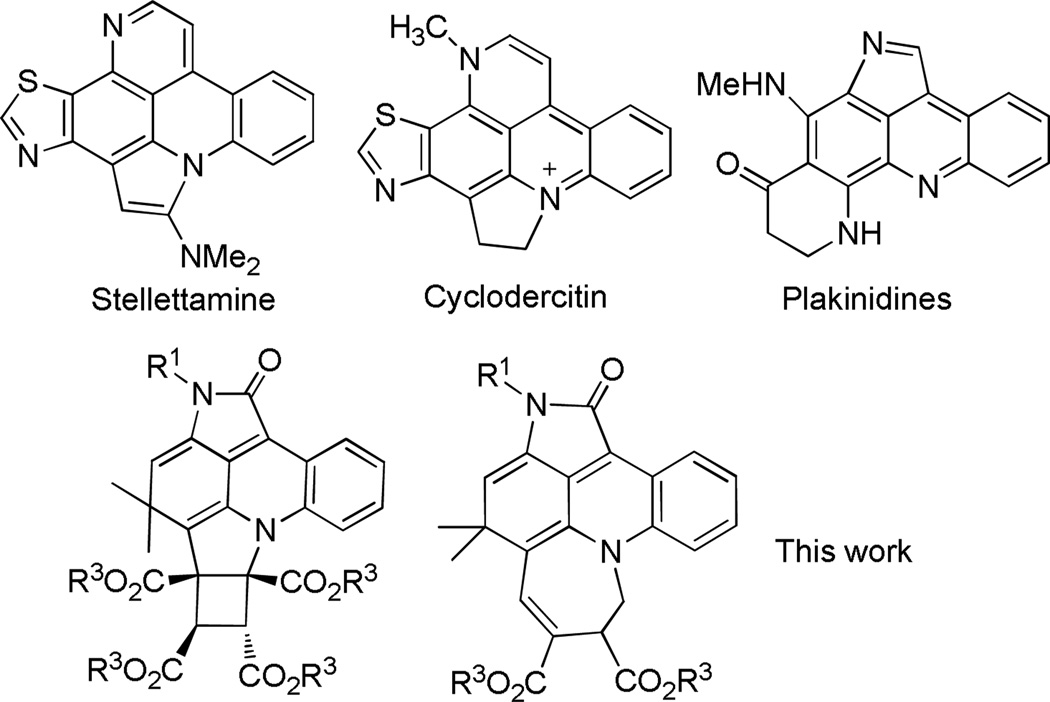

The assembly of complex polycyclic skeletons of chemical and biomedical importance has become a challenging and hot topic in modern organic chemistry.1,2 Among these skeletons, a unique pyrrolo-fused acridine parent ring system commonly exists in natural alkaloids and has been represented by Stellettamine,3 Cyclodercitin3,4 and Plakinidines5 (Figure 1); it shows a broad range of biological activities. These complex architectures have inspired our interest on creating new synthetic strategies for total synthesis and methodologies.6

Figure 1.

Several Representative Natural Products

Highly efficient syntheses usually reflect the sum of enormous efforts aimed at atom-economic and environmental elements and remarkable chemo-, stereo-and regioselective control of multi-ring construction.7 Domino multi-cyclizations (DMCs) have been successfully applied to total synthesis of natural and natural-like products by controlling multi-ring-junction frameworks.8 These reactions can not only enable constructing complex structures in a single operation but also avoid tedious isolation and purification work-up.9 Among these methodologies, various DMCs toward the formation of polycyclic fused azaheterocycles have been extensively studied.10 However, more efficient methodologies for the total synthesis of azaheterocyclic products from readily available reactants are remained to be extremely challenging.

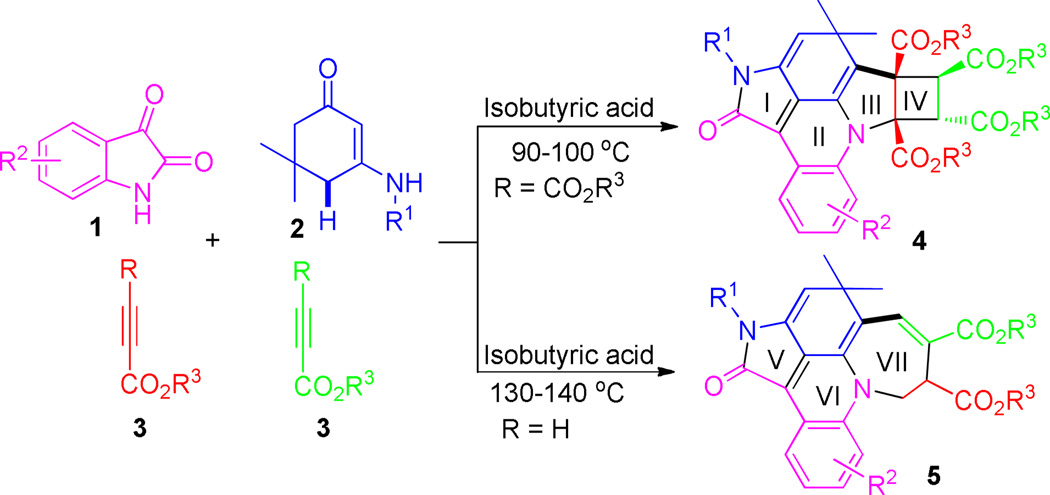

In the past several years, we and others have developed a series of domino reactions for the construction of multiple functional ring structures of chemical and pharmaceutical importance.11,12 During our continuous effort on this domino project, we now discovered novel domino multi-cyclization reactions of enaminones with isatin and electron-deficient alkynes divergently leading to formation of polyfunctionalized hexacyclic and pentacyclic fused acridines 4 and 5 in good yields and excellent stereoselectivity (Scheme 1). The resulting polyfunctionalized multicyclic fused acridines are important scaffolds for drug design and discovery, and can serve for pharmaceutical research.1

Scheme 1.

Two Novel Domino Multi-Cyclization Reactions

The attractive aspects of these domino reactions are shown by the fact that up to seven new chemical bonds and four new rings (tetracyclic 5-6-5-4 skeleton including pyrrole (I and III), pyridine (II), and cyclobutane (IV)) were readily formed in domino fashions that involved novel sequential [3+2]/[4+2]/[2+2+1]/[2+2] cyclizations in a one-pot operation. The newly formed four stereocenters including two quaternary centers were also controlled very well in a one-pot operation. Very interestingly, by changing of terminal groups of alkynes, the reaction can be controlled toward formation of tricyclic 5-6-7 skeletons including pyrrole (V), pyridine (VI) and azepine (VII) via another novel sequential [3+2]/[4+2]/[2+2+2+1] cyclization mechanism. In addition, the direct conversion of allylic C–H bonds into C–C bonds was achieved in this domino system without the use of any metal catalysts. To the best of our knowledge, the synthetic strategy and mechanistic sequences described in this communication have not been reported so far.

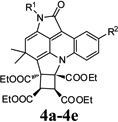

We began our investigation on multi-cyclization reaction of unsubstituted indoline-2,3-dione 1a, N-(4-chlorophenyl) enaminones 2a and symmetrical diethyl but-2-ynedioate 3a. When these components was mixed in a ratio of 1:1:2.2 and subjected to microwave irradiation in acetic acid (HOAc) at 110 °C, an intermolecular hexacyclic product, cyclobuta[4,5]pyrrolo [3,2,1-de]pyrrolo[4,3,2-mn]acridines 4a, was obtained in 45% yield. Its structure was unambiguously determined by X-ray diffraction analysis (See SI). This unprecedented observation prompted us to further optimize reaction conditions. Various acidic solvents, such as formic acid (HCOOH), trifluoroacetic acid (TFA), propanoic acid (EtCOOH), n-butyric acid (CH3(CH2)2COOH) and isobutyric acid ((CH3)2CHCOOH), were thus employed as microwave irradiation media. Among these solvents, the first two acids (HCOOH and TFA) led to poor yields of product 4a even at an enhanced temperature of 120 °C. Instead, only the intermediate D (Table 1, entries 2–3 and Scheme 2) was observed. Other two solvents, propanoic acid and n-butyric acid, resulted in product 4a in 47% and 51% isolated yield, respectively. The best yield of 59% was achieved when the reaction was performed in isobutyric acid. Attempting to enhance yield further, metal triflates such as Sc(OTf)3, Cu(OTf)2 and Zn(OTf)2, were then employed to promote the reaction.14 Unfortunately, complex mixtures were formed, making purification very difficult. It was found that acetic acid can serve not only as a suitable media but also as an adequate Brønsted acid promoter for the present multicyclizations shown in Scheme 1. It should be noted that for four-component reactions, this yield would be interpreted as a very good one.

Table 1.

Optimization for the Synthesis of 4a under MW

| entry | solvent | temp (°C) | time(min) | yielda% |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Acetic acid | 100 | 20 | 45 |

| 2 | Formic acid | 120 | 25 | trace |

| 3 | Trifluoroacetic acid | 120 | 25 | trace |

| 4 | Propanoic acid | 100 | 20 | 47 |

| 5 | n-Butyric acid | 100 | 20 | 51 |

| 6 | Isobutyric acid | 100 | 20 | 59 |

Isolated yield

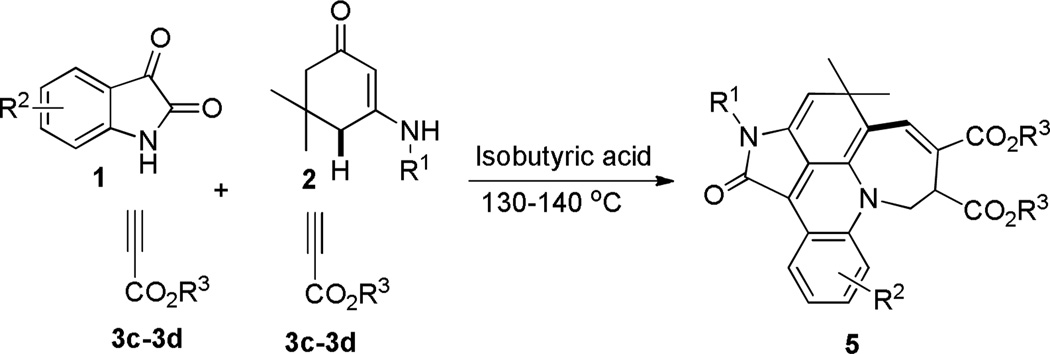

Scheme 2.

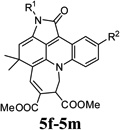

Domino Synthesis of Pentacyclic Fused Acridines 5

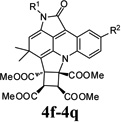

With this optimization in hand, we next examined the substrate scope of this reaction by using various readily available starting materials. As revealed in Table 2, various starting materials can be employed for this reaction and result in highly functionalized fused acridine derivatives that offer flexibility for structural modifications. For enaminone substrates, a variety of N-substituents bearing electron-withdrawing or electron-donating groups can all tolerate the reaction conditions. In the meanwhile, various substituted isatins, such as 5-F (1b) 5-Me (1c), and 5-Cl (1d) can also be utilized and result in corresponding hexacyclic fused acridines 4b–4q smoothly. Considering importance of N-substituted amino acids,15 the preformed N-carboxymethyl enaminones 2f was subjected to the reaction with 1a and 3b, providing the corresponding polycyclic substituted amino acid derivative 4k. As shown in Table 2, the present intermolecular domino multiple cyclilaztions showed the great substrate scope to give hexacyclic products in excellent stereoselectivity. Essentially, only a single diastereomer was detected by 1H and 13C NMR spectroscopic analysis.

Table 2.

Domino Synthesis of Fused Acridines 4 and 5

| entry | product 4 and 5a | substrate (1) | 2(R1) | 3’ | time /min | yield b/% | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 |  |

4a | Indoline-2,3-dione (1a) | 4-Chlorophenyl (2a) | 3a | 20 | 59 |

| 2 | 4b | Indoline-2,3-dione (1a) | Phenyl (2b) | 3a | 24 | 54 | |

| 3 | 4c | Indoline-2,3-dione (1a) | 4-Tolyl (2c) | 3a | 30 | 61 | |

| 4 | 4d | Indoline-2,3-dione (1a) | 3,4-Dimethoxyphenyl (2d) | 3a | 20 | 50 | |

| 5 | 4e | 5-Fluoroindoline-2,3-dione (1b) | 4-Tolyl (2c) | 3a | 25 | 46 | |

| 6 | 4f | Indoline-2,3-dione (1a) | 4-Chlorophenyl (2a) | 3b | 20 | 53 | |

| 7 | 4g | Indoline-2,3-dione (1a) | Phenyl (2b) | 3b | 22 | 56 | |

| 8 |  |

4h | Indoline-2,3-dione (1a) | 4-Tolyl (2c) | 3b | 24 | 59 |

| 9 | 4i | Indoline-2,3-dione (1a) | 3,4-Dimethoxyphenyl (2d) | 3b | 26 | 51 | |

| 10 | 4j | Indoline-2,3-dione (1a) | 4-Methoxyphenyl (2e) | 3b | 30 | 48 | |

| 11 | 4k | Indoline-2,3-dione (1a) | Carboxymethyl (2f) | 3b | 28 | 52 | |

| 12 | 41 | 5-Methylindoline-2,3-dione (1c) | 4-Chlorophenyl (2a) | 3b | 26 | 58 | |

| 13 | 4m | 5-Methylindoline-2,3-dione (1c) | Phenyl (2b) | 3b | 25 | 62 | |

| 14 | 4n | 5-Methylindoline-2,3-dione (1c) | 4-Tolyl (2c) | 3b | 26 | 64 | |

| 15 |  |

4o | 5-Methylindoline-2,3-dione (1c) | 4-Methoxyphenyl (2e) | 3b | 30 | 49 |

| 16 | 4p | 5-Methylindoline-2,3-dione (1c) | 4-Bromophenyl (2g) | 3b | 30 | 52 | |

| 17 | 4q | 5-Chloroindoline-2,3-dione (1d) | 4-Chlorophenyl (2a) | 3b | 28 | 45 | |

| 18 | 5a | Indoline-2,3-dione (1a) | Phenyl (2b) | 3c | 30 | 48 | |

| 19 | 5b | Indoline-2,3-dione (1a) | 4-Tolyl (2c) | 3c | 20 | 51 | |

| 20 | 5c | Indoline-2,3-dione (1a) | 4-Methoxyphenyl (2e) | 3c | 30 | 46 | |

| 21 | 5d | Indoline-2,3-dione (1a) | 3,5-Dichlorophenyl (2g) | 3c | 30 | 43 | |

| 22 |  |

5e | Indoline-2,3-dione (1a) | 4-Chlorophenyl (2a) | 3c | 28 | 40 |

| 23 | 5f | Indoline-2,3-dione (1a) | Phenyl (2b) | 3d | 25 | 50 | |

| 24 | 5g | Indoline-2,3-dione (1a) | 4-Tolyl (2c) | 3d | 28 | 52 | |

| 25 | 5h | Indoline-2,3-dione (1a) | 3,4-Dimethoxyphenyl (2d) | 3d | 28 | 45 | |

| 26 | 5i | Indoline-2,3-dione (1a) | 4-Methoxyphenyl (2e) | 3d | 30 | 42 | |

| 27 | 5j | Indoline-2,3-dione (1a) | Carboxymethyl (2f) | 3d | 30 | 46 | |

| 28 | 5k | Indoline-2,3-dione (1a) | 3-Chlorophenyl (2h) | 3d | 28 | 52 | |

| 29 | 51 | 5-Methylindoline-2,3-dione (1c) | 4-Tolyl (2c) | 3d | 28 | 55 | |

| 30 | 5m | 5-Methylindoline-2,3-dione (1c) | 4-Methoxyphenyl (2e) | 3d | 30 | 50 |

Conditions: the synthesis of products 4, (CH3)2CHCOOH (1.5 mL), 90–100 °C, microwave heating; the synthesis of products 5, (CH3)2CHCOOH (1.5 mL), 130–140 °C, microwave heating.

Isolated yield.

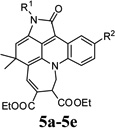

During our investigation on alkyne substrates, we found when unsymmetrical electron-deficient alkynes, propargyl esters 3c–d, were subjected to the reaction with indoline-2,3-diones 1 and N-substituted enaminones 2a–2h in acetic acid at 130–140 °C, propargyl esters were consumed within 20–30 min. Surprisingly, the reaction occurred toward another direction to give multifunctionalized pentacyclic fused acridines 5 that belong to another family of important scaffolds for organic and pharmaceutical sciences (Scheme 2).16 Two molecules of unsymmetrical electron-deficient alkynes 3c–d were introduced into the final pentacyclic fused acridine products (Scheme 2). The structural elucidation and attribution of stereoselectivity were unequivocally determined by NMR spectroscopic analysis and X-ray diffraction of single crystals that were obtained by slow evaporation of the solvents (4a and 5i see SI). The results are summarized in Table 2. Both electron-deficient and electron-rich aromatic groups on the N-substituted enaminones gave very good chemical yields (5a–5m) for this reaction. Furthermore, halogen functional groups (Cl, and Br) were tolerated well the current condition and can provide opportunities for further functional manipulations via cross-couplings.17 Similar to the former reaction, the latter also resulted in multiple rings and chemical bonds rapidly in a one-pot operation. Besides the characteristic of fast speed, these two reactions can be both worked out conveniently, in which water is a major by-product and the products can precipitate out after cold water was poured into the reaction mixture, which makes work-up very convenient simply by filtration/washing.

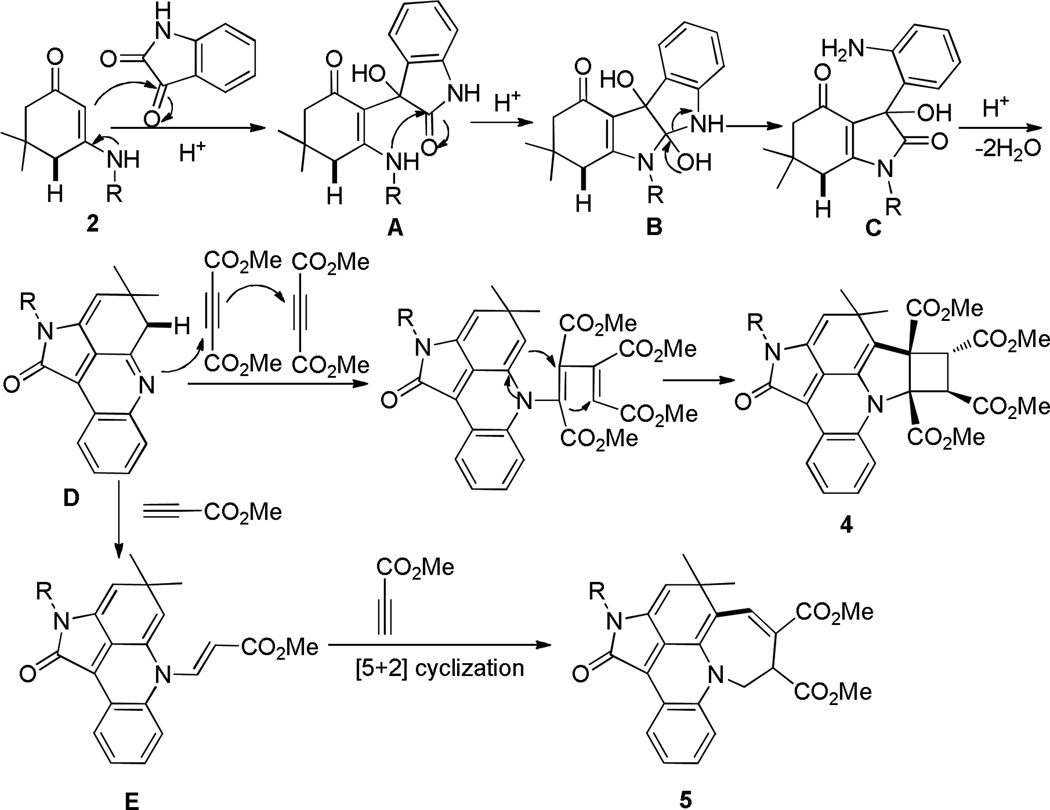

The mechanism for these two domino cyclizations are proposed and shown in Scheme 3. The former involves the ring closure cascade reactions that consist of initial nucleophilic addition (2 to A), intramolecular cyclization (A to B) and ring-opening of indoline-2,3-dione 1 (B to C), re-cyclization and dehydration (C to D), second intermolecular double nucleophilic additions and third double cyclizations (D to 4). Similar to the former, the latter underwent same sequent processes to give the intermediate D, which is followed by subsequent intermolecular nucleophilic addition with one molecular propargyl ester leading to formation of N-vinylethenamines E. The [5+2] cycloaddition between N-vinylethenamines E and propargyl ester occurred to yield thermodynamically stable pentacyclic products 5. This mechanism has been partially supported by an experiment in which the isolated intermediate D was subjected to the reaction with 3a in isobutyric acid; the hexacyclic product 4a was generated in 58% yield.

Scheme 3.

Mechanism Hypothesis for Forming 4 and 5

In summary, novel four-component domino [3+2]/[4+2]/[2+2+1] /[2+2] and [3+2]/[4+2]/[2+2+2+1] multi-cyclizations have been discovered for selectively diverse constructions of hexacyclic and pentacyclic fused acridines and polycyclic fused azaheterocyclic skeletons. The ready accessibility of starting materials and the broad compatibility of N-substituted enaminones make these reactions highly valuable for organic and biomedical fields. Other attractive features of these reactions include the mild condition, convenient one-pot operation, short reaction times of 20–30 min and excellent regio- and stereoselectivity. The continuing work on this project will be focused on the development of asymmetric versions of these reactions and applications of the resulting highly conjugate systems.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgment

We are grateful to financial support from the NSFC (Nos. 20928001, 21072163, 21232004 and 21102124), PAPD of Jiangsu Higher Education Institutions, Jiangsu Sci & Tech Support Program (No. BE2011045), NIH (R21DA031860-01, GL) and Robert A. Welch Foundation (D-1361, GL) for their generous support.

Footnotes

Supporting Information Available Experimental procedures and spectroscopic data for all new compounds. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

References

- 1.(a) Melhado AD, Brenzovitch WE, Lackner AD, Toste FD. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010;132:8885–8887. doi: 10.1021/ja1034123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Adams GL, Carroll PJ, Smith AB., III J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013;135:519–528. doi: 10.1021/ja3111626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Snyder SA, Breazzano SP, Ross, Lin Y, Zografos AL. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009;131:1753. doi: 10.1021/ja806183r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.(a) Yoder RA, Johnston JN. Chem. Rev. 2005;105:4730–4756. doi: 10.1021/cr040623l. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Sutherland JK. In: Comprehensive Organic Synthesis. Trost BM, editor. Vol. 1. Elmsford, NY: Pergamon Press; 1991. pp. 341–377. [Google Scholar]

- 3.(a) Gunawardana GP, Koehn FE, Lee AY, Clardy J, He HY, Faulkner DJ. J. Org. Chem. 1992;57:1523–1526. [Google Scholar]; (b) Agrawal MS, Bowden BF. Nat. Prod. Res. 2007;21:782–786. doi: 10.1080/14786410601132212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Le Bozec L, Moody CJ. Aust. J. Chem. 2009;62:639–647. [Google Scholar]

- 5.(a) Inman WD, O’Neill-Johnson M, Crews P. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1990;112:1–4. [Google Scholar]; (b) West RR, Mayne CL, Ireland CM, Brinen LS, Clardy J. Tetrahedron Lett. 1990;31:3271–3274. [Google Scholar]

- 6.(a) Wang H, Li L, Lin W, Xu P, Huang Z, Shi D. Org. Lett. 2012;14:4598–4601. doi: 10.1021/ol302058g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Jiang B, Wang X, Li M-Y, Wu Q, Ye Q, Xu H-W, Tu S-J. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2012;10:8533–8538. doi: 10.1039/c2ob26315g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Kefayati H, Narchin F, Rad-Moghadam K. Tetrahedron Lett. 2012;53:4573–4575. [Google Scholar]; (d) Gellerman G, Rudi A, Kashman Y. Tetrahedron. 1994;50:12959. [Google Scholar]

- 7.(a) Tietze LF. Chem. Rev. 1996;96:115–136. doi: 10.1021/cr950027e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Tietze LF, Brasche G, Gerike K. Domino Reactions in Organic Chemistry. Weinheim: Wiley-VCH; 2006. [Google Scholar]; (b) Padwa A. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2009;38:3072–3081. doi: 10.1039/b816701j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Tietze LF, Kinzel T, Brazel CC. Acc. Chem. Res. 2009;42:367–378. doi: 10.1021/ar800170y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Ganem B. Acc. Chem. Res. 2009;42:463–472. doi: 10.1021/ar800214s. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.(a) Turner CI, Williamson RM, Tumer P, Sherburn MS. Chem. Comm. 2003:1610–1611. [Google Scholar]; (b) Padwa A, Brodney MB, Lynch SM, Rashatasakhon P, Wang Q, Zhang H. J. Org. Chem. 2004;69:3735–3745. doi: 10.1021/jo049808i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.(a) Stearman CJ, Wilson M, Padwa A. J. Org. Chem. 2009;74:3491–3499. doi: 10.1021/jo9003579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) France S, Boonsombat J, Leverett CA, Padwa A. J. Org. Chem. 2008;73:8120–8123. doi: 10.1021/jo8016956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Topczewski JJ, Callahan MP, Neighbors JD, Wiemer DF. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009;131:14630–14631. doi: 10.1021/ja906468v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.(a) Trost BM, Shi Y. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1993;115:12491–12509. [Google Scholar]; (b) Huang AX, Xiong Z, Corey EJ. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1999;121:9999–10003. [Google Scholar]

- 11.(a) Jiang B, Li C, Shi F, Tu S-J, Kaur P, Wever W, Li G. J. Org. Chem. 2010;75:2962–2965. doi: 10.1021/jo1002278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Jiang B, Tu SJ, Kaur P, Wever W, Li G. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009;131:11660–11661. doi: 10.1021/ja904011s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Jiang B, Wang X, Shi F, Tu SJ, Ai T, Ballew A, Li G. J. Org. Chem. 2009;74:9486–9489. doi: 10.1021/jo902204s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (f) Jiang B, Li QY, Zhang H, Tu S-J, Pindi S, Li G. Org. Lett. 2012;14:700–703. doi: 10.1021/ol203166c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.(a) Snyder SA, Breazzano SP, Ross AG, Lin Y, Zografos AL. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009;131:1753–1765. doi: 10.1021/ja806183r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Yang JW, Fonseca MTH, List B. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005;127:15036–15037. doi: 10.1021/ja055735o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.(a) Groundwaater PW, Ali Munawar M. Advances in Heterocyclic Chemistry. 1998;70:88–161. doi: 10.1016/S0065-2725(08)60930-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Cookson JC, Heald RA, Stevens MFG. J. Med. Chem. 2005;48:7198–7207. doi: 10.1021/jm058031y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Antonini I, Polucci P, Magnano A, Sparapani S, Martelli S. J. Med. Chem. 2004;47:5244–5250. doi: 10.1021/jm049706k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.(a) Kobayashi S, Hachiya I, Araki M, Ishitani H. Tetrahedron Lett. 1993;34:3755–3758. [Google Scholar]; (b) Kobayashi S, Nagayama S, Busujima T. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1998;120:8287–8288. [Google Scholar]; (c) Nishina Y, Kida T, Ureshino T. Org. Lett. 2011;13:3960–3963. doi: 10.1021/ol201479p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.(a) Paquette LA. J. Org. Chem. 1964;29:3447–3449. [Google Scholar]; (b) Paquette LA, Broadhurst MJ. J. Org. Chem. 1973;38:1886–1893. [Google Scholar]; (c) Sato E, Ikeda Y, Kanaoka Y. Lieb. Ann. Chem. 1989;8:781–788. [Google Scholar]

- 16.(a) Gowan SM, Heald R, Stevens MFG, Kelland LR. Mol. Pharmcol. 2001;60:981–988. doi: 10.1124/mol.60.5.981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Stanslas J, Hagan DJ, Ellis MJ, Turner C, Carmichael J, Ward W, Hammonds TR, Stevens MFG. J. Med. Chem. 2000;43:1563–1572. doi: 10.1021/jm9909490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.(a) Rummelt SM, Ranocchiari M, van Bokhoven JA. Org. Lett. 2012;14:2188–2190. doi: 10.1021/ol300582y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Ma D, Cai Q. Acc. Chem. Res. 2008;41:1450–1460. doi: 10.1021/ar8000298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Fagnoni M, Albini A. Acc. Chem. Res. 2005;38:713–721. doi: 10.1021/ar0402356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Cho J-Y, Tse MK, Holmes D, Jr, Maleczka RE, Smith MR., III Science. 2002;295:305–308. doi: 10.1126/science.1067074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Lipshutz BH, Butler T, Swift E. Org. Lett. 2008;10:697–700. doi: 10.1021/ol702453q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.