Abstract

A monosyllabic word test was administered to 114 postlingually-deaf adult cochlear implant (CI) recipients at numerous intervals from two weeks to two years post-initial CI activation. Biographic/audiologic information, electrode position, and cognitive ability were examined to determine factors affecting CI outcomes. Results revealed that Duration of Severe-to-Profound Hearing Loss, Age at Implantation, CI Sound-field Threshold Levels, Percentage of Electrodes in Scala Vestibuli, Medio-lateral Electrode Position, Insertion Depth, and Cognition were among the factors that affected performance. Knowledge of how factors affect performance can influence counseling, device fitting, and rehabilitation for patients and may contribute to improved device design.

INTRODUCTION

Clinical research in the field of cochlear implants (CI) has shown that optimization of the speech processor program can improve adult CI users’ speech understanding (Skinner et al. 1997a; Skinner et al. 1999; James et al. 2002; Skinner et al. 2002a, Fourakis et al. 2007; Buechner et al. 2010; Holden et al. 2011; Mauger et al. 2012). However, substantial variability in speech recognition exists among CI recipients even after optimization of programming parameters (Heydebrand et al. 2007; Finley et al. 2008; Gifford et al. 2008; Lazard et al. 2012). Previous research has established certain biographic factors associated with variability in performance across CI users. Blamey et al. (1996) retrospectively examined data from a group of 808 CI recipients. Biographical information and speech recognition results were obtained from Cochlear Corporation as well as seven implant centers world-wide. Results identified several factors that were significant predictors of speech recognition; for example, duration of deafness had a strong significant negative effect on CI outcomes. In addition, age at implantation and age of onset of deafness were negatively related to speech recognition especially for patients over age 60. Blamey and colleagues (1996) discussed the influence of cognitive factors, such as intelligence, on speech recognition but noted that these factors have not been routinely studied in CI recipients. Moreover, central processing changes occur during aging and may affect speech recognition which likely compound results (Wingfield et al. 2005; Gates et al. 2008). Etiology was also significantly related to speech recognition; meningitis patients had lower while patients with Meniere’s disease had higher speech recognition than patients with other etiologies.

There were limitations with the patient population in the Blamey study that the authors acknowledged. The patients were obtained from a large number of centers using different speech recognition materials. Duration of deafness and age of onset of deafness may have been defined differently by each center. Various speech processor programming techniques were utilized across centers. Some patients may have received aural rehabilitation while others did not. Still, the factors affecting CI performance reported by Blamey et al. (1996) were in agreement with previous research studies (Millar et al. 1986; Dorman et al. 1989; Battmer et al. 1995; Summerfield and Marshall 1995).

More recent literature also supports duration of deafness as a primary factor contributing to CI outcomes. Rubinstein et al. (1999) found a strong correlation between duration of deafness and post-implant monosyllabic word recognition and a significant, but weaker, correlation between pre-implant sentence recognition scores and post-implant monosyllabic word recognition. Green et al. (2007) reported duration of deafness to be an independent predictor of performance, accounting for 9% of the variability in a retrospective study examining 117 postlingually-deaf patients implanted between 1988 and 2002. Neither pre-implant residual hearing nor age at implantation was a significant predictor of CI outcomes. Leung et al. (2005) examined a large group of CI recipients aged 14–91 enrolled at a number of centers. The recipients were divided into a younger group (< 65 years of age, n = 491) and an older group (≥ 65 years of age, n = 258). No correlation between age at implantation and post-implant monosyllabic word scores was seen. However, for both groups, monosyllabic word scores significantly declined with longer duration of deafness.

In a retrospective study, Budenz et al. (2011) compared two-year post-implant monosyllabic word and sentence recognition scores for an older (≥ 70 years, n = 60) and a younger (< 70 years, n = 48) group of postlingually-deaf CI users. Both groups had significant improvements in monosyllabic words and phonemes, sentences in quiet, and sentences in noise when comparing pre- to post-implant scores. After controlling for duration of deafness, there were no significant differences between groups or in the rate of improvement in speech recognition scores over a two year period. The authors concluded that older and younger CI users benefit equally from their devices.

Friedland et al. (2010) compared speech recognition scores obtained one year post-implant from groups of older (≥ 65 years, n = 28) and younger (< 65 years, n = 28) recipients. The participants in each group were matched for pre-implant sentence scores and duration of deafness. Significant differences were found between the groups for scores on monosyllabic words and sentences in quiet with the younger group having higher scores. The authors speculated that diminished cognition, specifically central auditory processing abilities, could be a contributing factor to the lower speech recognition scores in the older group.

Collison et al. (2004) examined the relation between cognitive and linguistic skills and speech recognition in postlingually-deaf adult CI users (mean age = 55, range = 34–68, n = 15). Since CI users hear a degraded signal which must be matched to words in memory, it was hypothesized that adults with a large vocabulary and a strong working memory may have better speech recognition than adults with a small vocabulary and relatively weak working memories. Based on standardized tests, the participants were found to have a distribution of cognitive and linguistic abilities comparable to the normative sample (adults with normal hearing). However, post-implant speech recognition was not correlated with cognitive or linguistic abilities for this group. Participants varied in their duration of deafness, duration of implant use, age at implantation, etiology, device type, and monosyllabic word recognition score (range = 5%–75%). The degree to which the signal was degraded for participants with poor word recognition may have negated the benefits of a large vocabulary and strong working memory. The authors hypothesized that with a larger, more homogeneous group of CI users, stronger cognitive and linguistic abilities may improve outcomes.

In a sample of 33 CI recipients, Heydebrand et al. (2007) did not find a significant correlation between improvement in monosyllabic word recognition and general cognitive ability at six months post-implantation. However, a specific cognitive skill, verbal learning, as measured by a composite score from the four subtests of the California Verbal Learning Test (CVLT, Delis et al. 2000), predicted 42% of the variance in six-month post-implant, monosyllabic word scores. When combined, verbal learning, baseline monosyllabic word performance (measured at two weeks post initial CI activation), and lipreading ability accounted for 82% of the variance in six-month word scores. The authors concluded that verbal learning may contribute to recipients’ ability to encode and ultimately interpret the degraded signal received from a CI by having a repertoire of possible material from which to “match” an ambiguous sound or word and being able to rapidly and efficiently select the best choice.

By means of various imaging techniques, the position of the electrode array within the cochlea can be determined and has been shown to be an additional source of variability in CI outcomes. Aschendorff et al. (2007) used rotational tomography to examine electrode position between the Nucleus Contour (n = 21) and Nucleus Contour Advance (n = 22) electrode arrays. Electrode arrays were categorized as positioned in scala tympani (ST), scala vestibuli (SV) or a translocation from ST to SV. Rotational tomography indicated a higher incidence of electrode arrays in SV and dislocations from ST to SV with the Contour electrode array than with the Contour Advance array. Moreover, group mean speech recognition scores were significantly higher for those individuals with arrays in ST as opposed to SV. Skinner et al. (2007) described a technique using spiral CT to determine the position of each electrode within the cochlea and reported results for fifteen postlingually-deaf participants implanted with Advanced Bionics’ devices (HiFocus I, n= 5; HiFocus Ij, n = 9; HiFocus Helix, n = 1). A negative correlation was found between the number of electrodes located in SV and monosyllabic word scores. Finley et al. (2008) extended this research further to better understand the effect of electrode position within the cochlea on the variability in speech recognition. Monosyllabic word scores and electrode position characteristics were examined for 14 of the 15 CI recipients who participated in the Skinner et al. (2007) study. The participants’ monosyllabic word scores ranged from 2% to 88% and electrode position varied along several dimensions across all participants (see Figure 4, Finley et al. [2008]). Results of a linear regression analysis revealed that scalar position of the electrode array (i.e. the scala with which the array was inserted and whether or not the array stayed in or transitioned from that scala), age at implantation, and total number of electrodes in SV accounted for 83% of the variance in monosyllabic word scores. In contrast, Wanna et al. (2011) did not find a correlation between post-implant monosyllabic word and sentence scores and position of the electrode array within the cochlea for 16 bilateral CI users (32 CIs). Based on modeling intracochlear anatomy of six cadaver temporal bones, the applied algorithm indicated 20 arrays were in ST, 11 transitioned from ST to SV, and one was in SV.

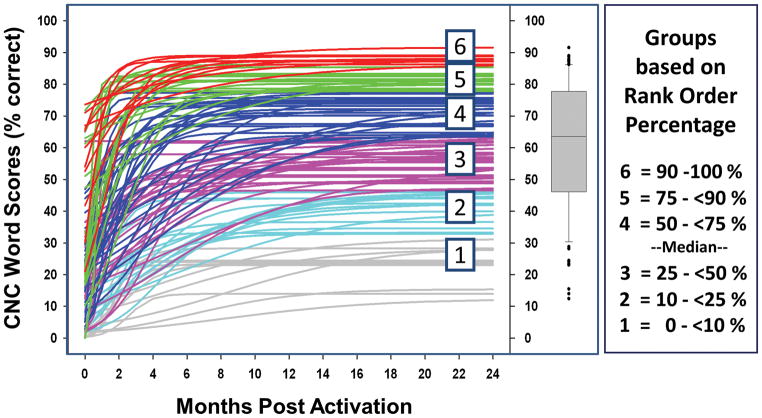

Figure 4.

The logistic curves for each of the participants and their assigned outcome group. The box plot shows the upper and lower quartiles about the median. The upper whisker represents the 90th rank-order percentile of all data. The lower whisker represents the 10th rank-order percentile of all data, and the filled circles represent individuals beyond those limits. The panel on the far right indicates the range of rank-order percentages defined for each group.

An additional descriptor of array position, insertion depth, was found by a number of investigators to relate to CI outcomes. Skinner et al. (2002b) examined electrode insertion depth and speech recognition for 26 Nucleus 22 recipients. Results revealed that monosyllabic word scores, obtained one-year post implant, were modestly but significantly and positively correlated with insertion depth. Yukawa et al. (2004) reported insertion depth to be positively correlated with speech recognition for recipients of Nucleus 22 and Nucleus 24 devices (n = 48). However, no correlation between insertion depth and CI outcome was found in a postmortem study of 15 temporal bones with a variety of CI devices, i.e. Nucleus 22, Nucleus 24, Ineraid, and Clarion (Kahn et al. 2005). Lee et al. (2010) extended the postmortem study of Khan et al. (2005) with more participants (27 total) and did not find a significant relationship between insertion depth and monosyllabic word recognition. In contrast to the above studies, Finley et al. (2008) found a negative correlation between insertion depth and word recognition scores in14 AB CI recipients.

The studies described above indicate that many factors may potentially influence an individual’s speech understanding with a CI. Aside from duration of deafness, there was not agreement among studies on which factors have the greatest bearing on speech recognition. Some studies retrospectively examined large groups of participants from a number of implant centers, whereas other studies prospectively examined a small group from the same center. The majority of studies do conclude that recognizing factors that may limit speech understanding with a CI would be useful in counseling patients before implantation. Furthermore, such knowledge would be valuable in improving fitting, developing new post-implant rehabilitative procedures, and designing improved cochlear implant systems.

The objective of the current study was to identify sources of variability in CI outcomes by evaluating word recognition in newly-implanted, postlingually-deaf adult CI recipients (n = 114) from a single center over a two-year period. This prospective, longitudinal study was designed to address some of the limitations recognized by Blamey and colleagues in their 1996 outcomes study. Additionally, the newly-implanted participants in the present study were evaluated for CI candidacy under expanded inclusion criteria and were implanted with a newer generation of devices compared to the CI users studied by Blamey et al. (1996). Based on previous studies, we expected that duration of deafness would contribute to outcome in addition to factors related to both the peripheral and central auditory system. Specifically, we hypothesized that electrode position within the periphery, calculated from CT scans, and cognition, based on its relationship to verbal processing in the central auditory system, contribute to variability in outcomes. Consequently, the main factors examined in the present study were biographic/audiologic information, electrode position within the cochlea, and cognitive function in each CI participant.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

This study was approved by the Human Research and Protection Office (HRPO # 201102047) at Washington University School of Medicine (WUSM) in St. Louis.

Participants

Between February 2003 and October of 2008, 201 adults were implanted at WUSM. All were invited to participate in the study. Of the 176 who agreed to participate, 114 postlingually-deaf adults were included in the current data set. All were unilaterally implanted by six surgeons associated with WUSM. Data from 62 adults were excluded for the following reasons: pre/perilingual onset of deafness (n = 31), excessive missing data due to illness, death, or inability to return for study visits (n = 15), obtained a 2nd CI during study (n = 11), device problem or re-implantation (n = 5). Table 1 summarizes participants’ biographic/audiologic information. Sixty-four females and 50 males participated with a mean age at implantation of 57.4 years. The criterion used to define postlingual deafness was onset of severe-to-profound hearing loss (SPHL) in both ears after the age of three. The majority of participants (n = 105) had onset of SPHL after age 16, six participants were between 3.2 and 9 years of age, and three were between 11 and 15 years of age. Of the nine participants with onset of SPHL prior to age 16, all wore a hearing aid in the ear to be implanted following diagnosis with one exception. This participant had sudden SPHL at the age of 11 due to ototoxicity. She was implanted at age 23 and had never worn a hearing aid in the implanted ear. The mean duration of SPHL for the total sample was 13.1 years.

Table 1.

Participants’ Biographic/Audiologic Information (N = 114)

| Biographic/Audiologic Information | Range* | Mean* | SD* |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age at CI | 23 – 83 | 57.4 | 16.3 |

| Education Level | 5 – 20 | 13.6 | 3.2 |

| Age at Onset of Hearing Loss | 7 wks – 69.5 | 25.5 | 19.1 |

| Duration of Hearing Loss | 0.7 – 67.7 | 31.8 | 15.5 |

| Age at Onset of SPHL | 3.2 – 78.1 | 44.3 | 19.3 |

| Duration of SPHL | 0.5 – 45 | 13.1 | 11.3 |

| Duration of HA Use | 0 – 55 | 18.9 | 14.4 |

| Pre-CI 4-Freq PTA (dB HL), CI Ear | 65 – 120 dB | 99.6 dB | 13.4 dB |

| Pre-CI 4-Freq PTA (dB HL), Other Ear | 60 – 120 dB | 97.6 dB | 15.6 dB |

| Pre-CI Sentence Recognition | 0 – 66% | 16.4% | 18% |

| Lipreading | 0% – 95.3% | 28.6% | 21.5% |

Abbreviations:

= years unless otherwise noted, CI = cochlear implant, Freq = frequency, HA = hearing aid, PTA = pure tone average, SPHL = severe-to-profound hearing loss, wks = weeks

All participants spoke and communicated in American English. The participants’ education level ranged from the fifth grade to doctoral level (20 years) with a mean of 13.6 years of education. The etiologies represented among participants were: autoimmune disease (n = 2), genetic (n = 37), head trauma (n = 2), high fever/infection (n = 5), maternal rubella (n = 3), Meniere’s disease (n = 3), meningitis (n = 2), multiple sclerosis (n = 1), noise exposure (n = 8), otosclerosis (n = 5), ototoxicity (n = 8), Usher’s Syndrome (n = 1), and unknown (n = 37).

The mean four-frequency, pure-tone average (PTA at 0.5, 1, 2, and 4 kHz) across participants in the ear to be implanted was 99.6 dB HL and in the other ear 97.6 dB HL. If a participant had no response at a tested frequency, 120 dB HL was assigned. For the majority of participants (n = 96), pre-implant, aided speech recognition was evaluated with HINT sentences (Nilsson et al. 1994), whereas the remaining 18 participants were administered the more clearly spoken CID sentences (Davis and Silverman 1978). The group mean pre-implant sentence recognition score in the ear to be implanted was 16.4%. Participants’ ability to lipread was evaluated pre-implant with CID sentences presented via 3M Scotch™ laser videodisc (Johns Hopkins University, 1986) with the sound turned off. The group mean lipreading score was 28.6%.

Cognitive Test Battery

Prior to implantation, all participants were evaluated with a battery of psychological tests selected to comprehensively assess cognitive functioning. The tests were given in a quiet office by a neuropsychologist. All measures were administered in both spoken and written format to ensure comprehension, and no procedure was initiated until the participant had repeated back the instructions accurately. The neuropsychological test battery included measures of short-term and working memory (Forward and Backward Digit Span tests; Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale III, 1997), language (Vocabulary test, Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale III, 1997), reasoning/executive function (Similarities and Matrices, Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale III, 1997; Trails A & B, Armitage 1946), and verbal learning (California Verbal Learning Test). For a description of each test, see text, Supplemental Digital Content 1.

Cochlear Implantation

Twenty-two participants were implanted in the better ear, 34 in the poorer ear, and 58 had similar hearing between ears (a four-frequency PTA mean difference of ≤ 5 dB between ears). The mean difference in the four-frequency PTA between ears for those implanted in the better ear was 20 dB (range = 6–47 dB) and for those implanted in the poorer ear was 19 dB (range = 6–51 dB). Sixty-seven of the 114 participants were implanted in the right ear, 47 in the left ear. Three-dimensional reconstruction of pre- and post-implant CT scans indicated that 110 participants had a complete insertion of the electrode array into the cochlea. One participant had two electrodes and three participants had one electrode located outside the cochlear canal in the region of the cochleostomy.

Nineteen participants were implanted with the Advanced Bionics (AB, Valencia, CA) CI system. Three of these participants used the CII receiver/stimulator and HiFocus I electrode array; 16 used the HiRes 90K receiver/stimulator where four had the HiFocus I electrode array, four had the HiFocus Helix, and eight had the HiFocus Ij electrode array. Ninety-five participants were implanted with a Nucleus device manufactured by Cochlear (Centennial, CO). Thirty-six were implanted with the Nucleus 24 receiver/stimulator, 32 with the Contour electrode array and four with the Contour Advance electrode array. The remaining 59 were implanted with the Freedom receiver/stimulator and Contour Advance electrode array. A variety of speech processors and speech processing strategies were used by participants. Table 2 summarizes device information for the group.

Table 2.

Device Usage Across All Participants (N=114)

| Implant System | Advanced Bionics (N=19 total) | N | Cochlear (N=95 total) | N |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Internal Device | CII/HiFocus I | 3 | Nucleus 24/Contour | 32 |

| HiRes 90K/HiFocus I | 4 | Nucleus 24/Contour Advance | 4 | |

| HiRes90K/HiFocus Helix | 4 | Freedom/Contour Advance | 59 | |

| HiRes 90K/HiFocus Ij | 8 | |||

|

| ||||

| Speech Processor | Auria | 4 | Sprint | 19 |

| Harmony | 8 | 3G | 17 | |

| Platinum Speech Processor | 7 | Freedom | 59 | |

|

| ||||

| Processing Strategy | HiRes-Sequential | 11 | ACE | 90 |

| HiRes-Paired | 3 | SPEAK | 5 | |

| HiRes-Fidelity 120 | 5 | |||

Abbreviations: ACE = Advanced Combination Encoder, HiRes = HiResolution, SPEAK = Spectral Peak

Speech Processor Fitting and Clinical Aural Rehabilitation

All participants had speech processor programming and aural rehabilitation (AR) performed by experienced CI audiologists at WUSM (Skinner et al. 2002c). The programming procedure used for each participant was the standard clinical protocol used for all adult CI patients at WUSM. This protocol included trying different stimulation rates and speech processing strategies, adjusting minimum and maximum electrical stimulation levels on each electrode, and modifying other parameters such as gain, frequency assignment table, input dynamic range, and number of active electrodes. To optimize benefit in everyday life for each recipient, soft speech/sound needs to be audible, conversational speech comfortably loud, and loud speech/sound tolerable. Frequency modulated (FM) tone, sound-field threshold (SFT) levels were routinely checked with the aim of obtaining SFT levels < 30 dB HL from 250–6000 Hz to ensure audibility of soft speech and sound. During AR, participants learned to listen with their speech processors via auditory training exercises and were taught effective strategies for communicating in difficult listening environments and over the telephone. This comprehensive program provided individual guidance and support to maximize benefit with a CI. Post-Implant Test Stimuli

All test stimuli were presented in a doubled-walled sound attenuating booth through a loudspeaker placed at ear-level at 0° azimuth and 1.5 meters from the center of the participant’s head. Monosyllabic word recognition after cochlear implantation was evaluated using the Consonant-Vowel Nucleus-Consonant (CNC) Monosyllabic Word Test (Peterson and Lehiste 1962). The words are spoken by a male talker with mid-western American dialect and are part of the Minimum Speech Test Battery for Adult CI Users (Luxford et al. 2001). FM tones at .25, .5, .75, 1, 1.5, 2, 3, 4, and 6 kHz were presented to evaluate CI SFT levels. (For details regarding calibration of equipment and test materials, see Holden et al. 2011.)

Audiometric and Word Recognition Test Procedures

Participants were tested using the speech processor program, volume, and sensitivity settings that they used most often in everyday life. If the participant wore a hearing aid on the nonimplanted ear, the hearing aid was turned off. Sound-field, FM tones were presented using the Hughson-Westlake procedure (Carhart and Jerger 1959) and a 2 dB step size. If SFT levels were not consistent with those obtained previously, equipment was checked and replaced if necessary or the participant’s program was re-evaluated; however, the need for reprogramming was rare. CNC words were then presented at 60 dB SPL. A total of 100 words were presented (2 lists, 50 words per list). Of the 10 CNC word lists available, eight lists were used to form four pairs (Lists: 1 & 2, 3 & 4, 5 & 6, 9 & 10). These pairs were presented in sequence over four test sessions and then repeated. No pair of lists was repeated more often than six weeks apart; Skinner et al. (1997b) reported no significant differences due to learning for CNC word scores for this time period. From February 2003 until November of 2007, participants were administered CNC words during 21 test sessions from two weeks to two years post initial activation of their CI. CNC words were administered at two-week test intervals until three months post initial activation, monthly until one year, and then every other month until two years post initial activation. In November of 2007, the number of test sessions was streamlined from 21 to 12 (i.e. 2, 4, 6 and 9 weeks, then 3, 6, 9, 12, 15, 18, 21, and 24 months).

Analysis of Position of Implanted Electrodes from CT Scan Data

Metal artifact contamination, referred to as metallic bloom, affects the CT images of implanted electrode arrays by creating an image or bloom effect around the array that interferes with the ability to identify individual electrode contacts and obscures adjacent cochlear anatomy. Skinner et al. (2007) developed and Teymouri et al. (2011) validated a technique to overcome the metal artifact contamination and correctly identify the position of implanted electrodes in the inner ear. Using well-defined anatomical landmarks, we co-register with ANALYZE software (Mayo Clinic, Rochester; Robb 2001) an individual’s pre-implant CT image voxel space optimized for anatomical detail with their post-implant CT image space optimized for resolution of the electrode. The electrode lead wires and contacts are identified, segmented from the post-implant image data, and copied into the pre-implant image space to provide a composite image of electrode placement within an individual’s cochlea. To better visualize the scalar position of the segmented array and the individual electrode contacts, the aforementioned composite CT volume is then aligned with a high resolution cochlear atlas to infer the location of fine and soft tissue intra-cochlear structures not resolved by CT, such as the basilar membrane. The atlas is based on an orthogonal-plane, fluorescence optical sectioning (OPFOS) microscopy scan of a single male donor with normal cochlear anatomy and illustrates details of both the soft tissue and boney structure of the cochlea (Voie 2002).

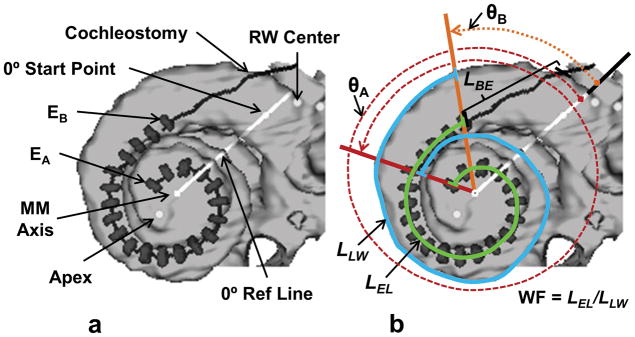

Figure 1 is a composite CT volume rendering of a participant’s lateral cochlear wall and electrode array viewed along the mid modiolar (MM) axis and shown with the markers and lines used to measure the participant’s cochlear dimensions and array position. The dark line and gray hash marks in Figure 1a show the path of the array and the location of the 22 electrode contacts of a Contour Advance array (EA = apical-most electrode, EB = basal-most electrode). Shown are the center of the round window (RW), the cochleostomy site, the 0° start point which marks the beginning of the cochlear canal as described in Skinner et al. (2007), the apex of the cochlea, the mid modiolar axis, and the 0° reference line. Figure 1b illustrates how the angular positions or insertion angles, θB and θA, of electrodes EB and EA, respectively, are measured based on rotation about the MM axis from the 0° reference line. Figure 1b also shows the length measurements used to determine the array insertion depth and the medio-lateral position of the array (Wrapping Factor, WF). These measurements include the lateral wall length (LLW) from the angular position of EB to the angular position of EA (blue line), the length along the electrode trajectory (LEL) from EB to EA (green line), and the distance along the electrode array from the cochleostomy to EB (LBE). The electrode insertion length to EA is then the sum of lengths LBE and LEL

Figure 1.

CT derived image of a participant’s electrode array (Contour Advance) and corresponding markers used to measure array position. See text for description.

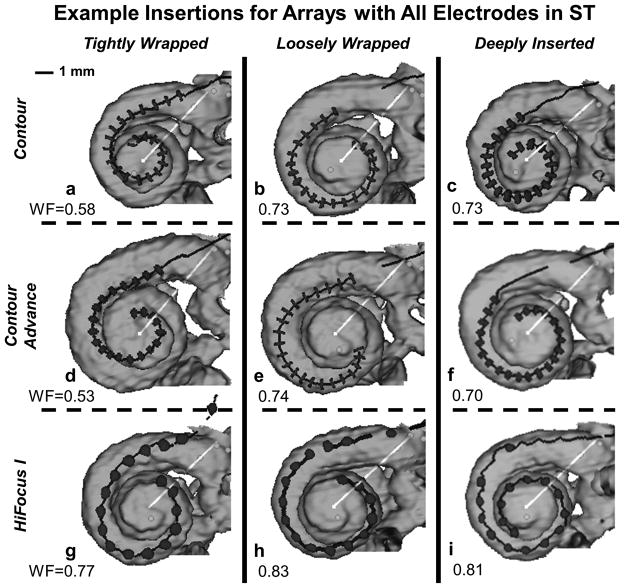

The medio-lateral position of the electrode array or Wrapping Factor was defined [WF = LEL/LLW] to provide a metric of how tightly or loosely wrapped an electrode array is relative to the modiolar wall (i.e. perimodiolar position). Because the modiolar wall was not directly visible in the CT scans, the metric is indirectly based on measurements of electrode position relative to the visible lateral wall. As defined, the Wrapping Factor metric approaches 1.0 when the array is closest to the lateral wall and LEL approaches LLW (loosely wrapped). The Wrapping Factor metric becomes smaller when the array is wrapped more tightly relative to the modiolar wall (LEL < LLW). As such, the Wrapping Factor metric is only meaningful for electrodes located in ST and is not applied for electrodes located in SV or which translocate from ST to SV. Figure 2 shows tightly-wrapped, loosely-wrapped and deeply-inserted examples of three array types (Nucleus Contour, Nucleus Contour Advance, and AB HiFocus I). Each of these insertions maintained all electrodes in ST; the corresponding Wrapping Factor is indicated in each panel. The figure illustrates that an array of any given type can assume highly disparate medio-lateral positions during insertion. Arrays can be positioned laterally (panel 2i) or medially (panel 2a) along their full length or assume both medial and lateral positions at different depths (panels 2b, 2e or 2g). Note that similar Wrapping Factor metrics can describe somewhat different electrode positions (panels 2b, 2c and 2e). A greater degree of variability in electrode positioning can be observed across all participants when insertions involve scalar translocations.

Figure 2.

Examples of tightly-wrapped, loosely-wrapped and deeply-inserted electrode arrays positioned in ST for the Nucleus Contour, Nucleus Contour Advance, and AB HiFocus I. See text for description.

RESULTS

Post-Implant Word Recognition Measures and Logistic Curve Fitting

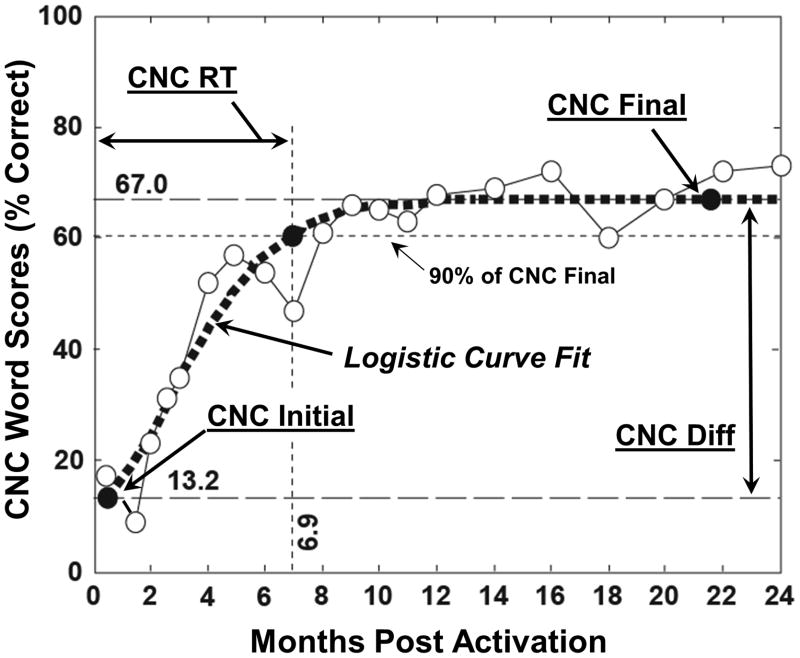

CNC word scores, longitudinally collected over two years for each participant, were fit with a logistic curve to model word scores as a function of time. The logistic curve fitting procedure was chosen because of its effectiveness in describing natural processes exhibiting limited-growth behavior over time as is characteristic of CI-user word recognition. The logistic model allowed interpolation of data for participants with some missing data and use of datasets in which the timing of data collection varied about a target point. In addition, the logistic curve fit reduced within-subject data variability by modeling the general growth trend of the data for each individual. To provide clinically-relevant word recognition measures for each participant, four metrics of post-implant CNC word recognition were derived from the logistic curve fits and statistically examined. These included CNC Initial Score obtained at the first test interval two weeks after initial activation of the CI, CNC Final Score comprised of an asymptotic score to which performance converged over two years, CNC Rise Time (RT) defined as the time to achieve 90% of the CNC Final Score, and CNC Difference (Diff) Score which is the difference between CNC Initial and Final Scores. Figure 3 shows CNC word scores at each post-implant test interval (open circles) over a two-year period for a typical participant. The data points have been fit with a logistic curve (dotted line). The four word recognition metrics are also indicated on the figure.

Figure 3.

A participant’s CNC word scores over time (open circles), the corresponding logistic curve fit (dotted line), and the four post-implant word recognition metrics. CNC Initial Score for this participant was 13.2%. CNC Final Score was 67%; CNC Rise Time (RT) to 90% of the CNC Final Score was 6.9 months, and CNC Diff Score was 53.8%.

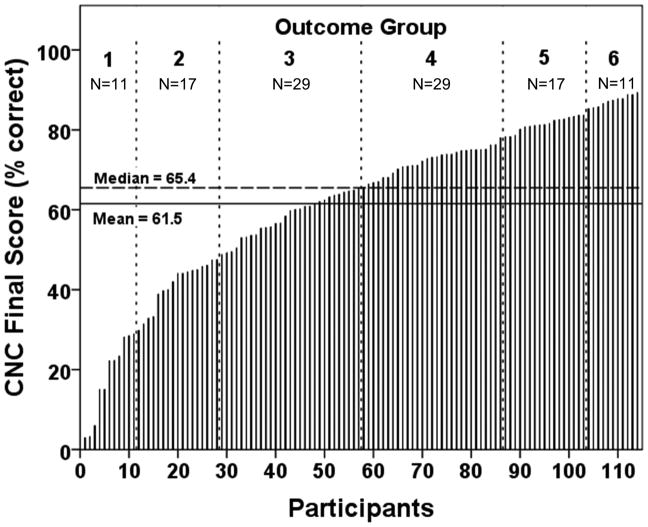

Individual logistic curves for all 114 participants are shown in Figure 4. To facilitate the examination of the factors affecting word recognition in postlingually deafened, adult CI users, participants were divided into six outcome groups based on the percentile ranking of their CNC Final Score. The panel to the far right of Figure 4 indicates the rank order percentages defined for each group. These groupings were motivated by the summary box plot in the middle panel of Figure 4. The horizontal line near the middle of the box is the median, and the box spans the range of the quartiles above and below the median (25% to 50% by rank order). The whiskers define the range of CNC word recognition scores of participants ranked above 10% and less than 90% for all participants. The individual data points beyond the whiskers represent the participants with either very low or high word recognition. These individuals are not considered outliers but are individuals at the extremes of performance. Outcome groups were defined on these percentile ranking boundaries and numbered from 1 to 6 in increasing order of word recognition. Figure 5 shows each participant’s CNC Final Score in rank order from lowest to highest, along with the outcome groupings. By including Groups 1 and 6, the top and bottom 10% of performers, we emphasize the conditions that may occur less frequently but contribute strongly to the extremes of CI performance. To check for the possibility that the group selections might distort the results, alternative groupings (e.g. 10, 6, 5, 4, 3, or 2 groups with linearly-spaced boundaries or with boundaries based on estimates from clinical experience) were also examined using the subsequent analysis procedures. The alternative groupings had little effect on the statistical findings.

Figure 5.

CNC Final Score for each participant rank ordered from lowest to highest score and each participant’s corresponding outcome group.

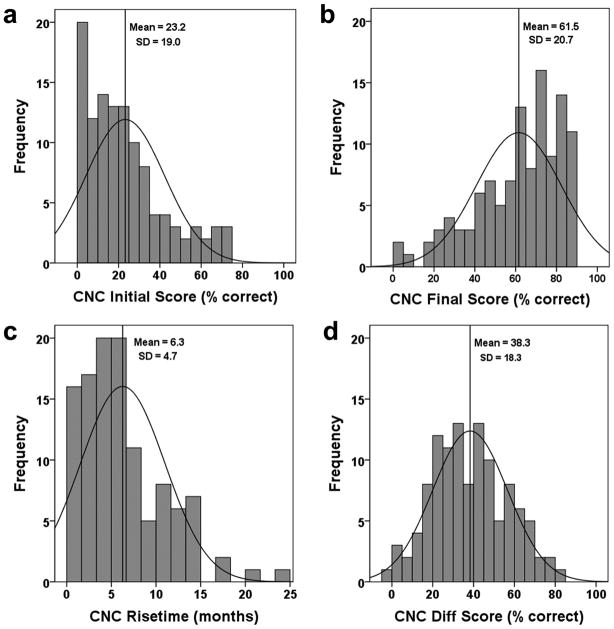

Summary descriptive statistics for the four post-implant word recognition metrics across all participants and each outcome group are shown in Table 3. The average participant had a CNC Initial Score (obtained two weeks after initial activation of the CI) of 23.3% that rose 38.3 percentage points to a stable plateau (CNC Final Score) of 61.5% in 6.3 months (RT). A comparison of medians to means shows that at two weeks post initial activation the majority of participants scored below the mean CNC Initial Score, whereas after achieving asymptotic performance, the majority scored above the mean CNC Final Score. Furthermore, most participants made this transition in less than the mean transition time for all participants. These relationships are also evident in Figure 6 which shows histograms and expected normal distributions for the word recognition metrics. In Figure 6b the mean CNC Final Score (61.5%) is less than the median (65.4%) as indicated by the distribution being skewed above the mean toward higher performance. Applying the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test of normality, CNC Final Score [D(114) = 0.101, p = 0.007], CNC Initial Score [D(114) = 0.111, p = 0.002] and CNC RT [D(114) = 0.136, p = <0.000] were significantly non-normal, whereas CNC Diff Score [D(114) = 0.053, p > 0.20] was normally distributed. The lack of normality for the key metric of CNC Final Score indicated that traditional parametric statistical tools could not be appropriately used; consequently, a non-parametric statistical tool was employed in the data analysis.

Table 3.

Summary Data for the Four Word Recognition Metrics for All Participants and Across Outcome Groups 6 to 1 (Highest to Lowest Performers)

| WR Metrics | All Participants Mean [Median] (± SD) {Min–Max} | Group 6 Mean [Median] (± SD) {Min-Max} | Group 5 Mean [Median] (± SD) {Min–Max} | Group 4 Mean [Median] (± SD) {Min–Max} | Group 3 Mean [Median] (± SD) {Min–Max} | Group 2 Mean [Median] (± SD) {Min–Max} | Group 1 Mean [Median] (± SD) {Min–Max} |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | 114 | 11 | 17 | 29 | 29 | 17 | 11 |

| CNC Initial Score (%) | 23.3 [19.2] (± 19) {0–73.6} | 51.0 [54.0] (± 20.3) {21.0–73.6} | 30.0 [22.2] (± 20.1) {1.5–65} | 24.7 [23.1] (± 17) {0–68.9} | 23.4 [23.8] (± 12.7) {2.1–59.7} | 9.3 [8.9] (± 4.8) {2.4–21.7} | 3.2 [2.5] (± 3.7) {0–10.2} |

| CNC Final Score (%) | 61.5 [65.4] (± 20.7) {2.9–89.3} | 87.3 [87.4] (± 1.4) {85.3–89.3} | 81.4 [81.3] (± 1.8) {78.3–83.7} | 72.1 [73.1] (± 3.4) {65.5–78} | 58.5 [59.9] (± 5.0) {49.2–65.4} | 41.4 [44.1] (± 5.9) {29.8–48.8} | 17.7 [22.2] (± 10) {2.9–28.8} |

| CNC RT (months) | 6.3 [5.3] (± 4.7) {0.5–24.0} | 3.2 [2.9] (± 1.6) {0.7–6.2} | 3.1 [2.4] (± 2.7) {0.7–10.5} | 7.2 [5.2] (± 6.1) {0.5–24} | 7.2 [6.4] (± 4.2) {0.5–18.3} | 7.3 [6.7] (± 3.6) {2.4–12.6} | 7.7 [5.0] (± 5.1) {1.7–18.1} |

| CNC Diff Score (%) | 38.3 [36.3] (± 18.3) {−2.5–82.1} | 36.2 [34.8] (± 19.8) {13.8–66.4} | 51.4 [56.3] (± 20.5) {16.2–82.1} | 47.4 [48.5] (± 17.7) {−2.5–78} | 35. 0 [33.6] (± 13) {2.3–55.9} | 32.1 [32.6] (± 5.9) {22.2–43.8} | 14.5 [18.3] (± 8.3) {2.8–25.1} |

Abbreviations: Diff = Difference, Max = maximum value, Min = minimum value, N = number, RT = Rise Time to 90% of CNC Final Score, SD = Standard Deviation, WR = Word Recognition

Figure 6.

Histograms in panels (a–c) display the non-normal distribution of CNC Initial Score, CNC Final Score, and CNC RT, respectively. Panel (d) displays the normal distribution of CNC Diff Score.

Analysis of the relationship between the Wrapping Factor and word recognition metrics was performed separately and only for array insertions in which all electrodes were within ST (n = 59). With this select population, outcome group sizes were small and prevented group-based analysis. Applying the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test of normality, CNC Final Score [D(59) = 0.106, p = 0.095], CNC Initial Score [D(59) = 0.114, p = 0.054] and CNC Diff Score [D(59) = 0.108, p = 0.086] were significantly normal, whereas CNC RT [D(59) = 0.186, p < 0.001] was not normally distributed.

Non-parametric Correlations and Principal Component Measures

Tables 4 and 5 summarize the correlations and corresponding significance levels (Spearman, ρs, 2-tailed) of an analysis of the dependent performance measures (outcome groups and/or word recognition metrics) and the independent experimental measures. Included in these tables are various principal component (PC) measures which were computed to reduce and summarize the information contained across multiple, highly-correlated metrics related to the same general topics, specifically hearing loss duration, cognitive measures, and electrode insertion depth. In all cases the PCs were computed using no rotation and accepted if eigenvalues were >1. Factor coefficients for individual participants were computed using the Anderson-Rubin method to ensure orthogonal factors with means of 0.0 and SDs of 1.0.

Table 4.

Bivariate Spearman Correlation Coefficients and Significance Levels (2-Tailed) for Dependent Performance Measures and Independent Biographic, Audiologic, and Cognitive Measures for All Participants (N=114)

| Measures (All Participants) | Outcome Group | CNC Final | CNC Initial | CNC RT to 90% of CNC Final | CNC Difference (Final-Initial) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dependent Performance Measures | |||||

| Outcome Group | 1 | ||||

| CNC Final | .980 *** | 1 | |||

| CNC Initial | .596 *** | .587 *** | 1 | ||

| CNC RT | −.384 *** | −.385 *** | ns | 1 | |

| CNC Diff | .430 *** | .457 *** | −.262 ** | ns | 1 |

| Independent Experimental Measures | |||||

| Biographic Measures | |||||

| Age at CI | −.254 ** | −.268 ** | ns | ns | −.271 ** |

| Educational Level | ns | .205 * | ns | ns | .218 * |

| Gender, Handedness, and CI Ear | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns |

| Audiologic Measures | |||||

| Age Onset HL | ns | ns | .313 *** | ns | −.296 ** |

| Duration of HL | −.378 *** | −.359 *** | −.475 *** | .198 * | ns |

| Duration of SPHL | −.402 *** | −.380 *** | −.441 *** | .248 ** | ns |

| Duration of HA Use | −.190 * | ns | ns | ns | ns |

| 1st PC HL Duration | −.402 *** | −.381 *** | −.429*** | .226* | ns |

| Pre-CI Sent Recog | ns | ns | ns | ns | −.256 ** |

| Lipreading | ns | ns | ns | ns | .220 * |

| Unaided PTA in CI Ear (Pre-Implant) | ns | ns | ns | .217 * | ns |

| CI SFT Levels | −.336 *** | −.327 *** | −.235 * | .350 *** | ns |

| Cognitive Measures | |||||

| 1st PC Raw Data | .304 *** | .278 *** | .206 * | ns | ns |

| 2nd PC Raw Data | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns |

| 1st PC STD Data for Age, Gender, Ethnicity | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns |

| 2nd PC STD Data | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns |

Significance: ns (p>0.05),

(p≤0.05),

(p≤0.01),

(p≤0.001)

Abbreviations: CI = cochlear implant, Diff = difference, HA = hearing aid, HL = hearing loss, ns = not significant, PC = principal component, PTA = pure tone average, Recog = recognition, RT = rise time, Sent = sentence, SFT = sound-field threshold, SPHL = severe-to-profound hearing loss, STD = standardized

Table 5.

Bivariate Spearman Correlation Coefficients and Significance Levels (2-Tailed) for Dependent Performance Measures and Independent Measures of Electrode Position

| Independent Measures (continued from Table 4) (All Participants) | Outcome Group | CNC Final | CNC Initial | CNC RT to 90% of CNC Final | CNC Difference (Final-Initial) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Scalar Location for All Participants (N=114) | |||||

| % Elect in ST | .302 *** | .332 *** | ns | −.258 ** | .209 * |

| % Elect in Mid Pos | ns | ns | ns | .203 * | ns |

| % Elect in ST+Mid | .336 *** | .341 *** | ns | −.242 ** | .239 ** |

| % Elect in SV | −.336 *** | −.341 *** | ns | .242 ** | −.239 ** |

| Insertion Depth for All Participants(N=114) | |||||

| Array Trajectory Length | ns | −.204 ** | −.214 * | ns | ns |

| Angular Pos Apical Elect | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns |

| Angular Pos Basal Elect | ns | −.200 * | ns | ns | ns |

| 1st PC Array Insertion Depth | ns | −.204 * | ns | ns | ns |

| Medio-lateral Position for Array Insertions with All Electrodes in ST (N=59) | |||||

| Wrapping Factor | na | −.378 ** | ns | ns | ns |

Significance: ns (p>0.05),

(p≤0.05),

(p≤0.01),

(p≤0.001)

Abbreviations: Elect = electrode(s), Mid Pos = position in middle of scalar cross section approximately at the level of the basilar membrane, na = not applicable, ns = not significant, Pos = position, PC = principal component, RT = rise time, ST = scala tympani, ST+Mid = sum of electrodes in ST and Mid Pos, SV = scala vestibuli

The data indicate that a number of independent biographic/audiologic, electrode position, and cognitive measures were related to outcome group and word recognition metrics. These measures are the focus of the subsequent non-parametric analyses. The greatest associations between outcome groups and the performance metrics were Age at CI, Duration of Hearing Loss (HL), Duration of SPHL, CI SFT Levels, Cognitive Measures (Table 4), Scalar Location and Medio-lateral Position of the electrode array (Table 5). In select cases, analyses revealed significant correlations between various independent variables which are discussed in the text but not included in the tables. For example, Age at CI correlated highly with both CNC Final Score (ρs = −.268, p = .004, 2-tailed) and Cognitive Measures (1st PC Cognitive Raw Data: ρs = −.468, p < .001, 2-tailed). This suggests that age may be a dominant cofactor in the study and may mask the effects of other experimental measures related to audiologic history and details of cochlear implantation. To address the correlation between Age at CI and Cognitive Measures, the cognitive data were analyzed both as raw and age-standardized scores. To address age effects directly, a subpopulation of participants was examined where Age at CI was controlled. Both topics are addressed later in the paper.

Non-parametric Multivariate Analysis of Variance

A non-parametric multivariate analysis of variance (NPMANOVA) was performed across the six outcome groups in relation to the independent experimental factors identified to have significant or strong relationships to the outcome groups or word recognition metrics based on the ρs correlations shown in Tables 4 and 5. Because of the non-normal distribution of the data, this analysis was conducted using a permutationally-based, one-way MANOVA analysis method (NPMANOVA, Anderson 2001) as implemented in the PAST statistical analysis package (Hammer et al, 2001) followed by post hoc comparisons and Bonferroni applied corrections.1

Subsequent analyses focused primarily on the significant relationships between the six outcome groups and specific measures related to biographic/audiologic information, electrode position, and cognitive measures. The non-parametric Jonckheere-Terpstra (JT) Test identified the measures which showed significant linear relationships across the medians of the six outcome groups (Jonckheere 1954; Field 2009).2

Table 6 shows the standardized JT statistics and associated significance level for each of the experimental measures determined to be significant (p ≤ 0.05, 1-tailed). The experimental measures are ordered by descending effect size. Effect sizes are also presented in terms of percentages or multipliers normalized to the greatest effect size. In some cases, several factors co-vary and address aspects of the same general topic (designated by common superscripts). Factors selected for further elaboration are underlined in the table.

Table 6.

Factors that Varied Significantly (Jonckheere-Terpstra Test, 1-tailed) across Outcome Groups Arranged in Order of Decreasing Effect Size for All Participants (N=114)

| Factor Type | Factors | Std. J-T Statistic | Effect Size | Normalized Effect Size | Reciprocal of Normalized Effect Size |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | Duration of SPHL# | −4.50 *** | 0.42 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| A | 1st PC HL Duration# | −4.47 *** | 0.42 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| A | Duration of HL# | −4.13 *** | 0.39 | 0.92 | 1.09 |

| A | CI SFT Levels | −3.64 *** | 0.34 | 0.81 | 1.23 |

| EP | % Elect in ST+Mid Pos§ | 3.58 *** | 0.34 | 0.80 | 1.25 |

| EP | % Elect in SV§ | −3.58 *** | 0.34 | 0.80 | 1.25 |

| EP | % Elect in ST§ | 3.32 *** | 0.31 | 0.74 | 1.35 |

| C | 1st PC of Raw Cognitive Data | 3.26 *** | 0.31 | 0.73 | 1.38 |

| B | Age at CI | −2.75 ** | 0.26 | 0.61 | 1.63 |

| A | Duration of HA Use# | −2.08 * | 0.20 | 0.46 | 2.16 |

| EP | Array Trajectory Length* | −1.89 * | 0.18 | 0.42 | 2.37 |

| B | Education Level | 1.88 * | 0.18 | 0.42 | 2.39 |

| EP | 1st PC Array Insertion Depth* | −1.79 * | 0.17 | 0.40 | 2.52 |

| EP | Angular Pos Basal Elect* | −1.71 * | 0.16 | 0.38 | 2.63 |

| A | Pre-CI Sent Recog | 1.66 * | 0.16 | 0.37 | 2.71 |

| EP | % Elect in Mid Pos§ | −1.65 * | 0.15 | 0.37 | 2.73 |

Significance:

(p≤0.05),

(p≤0.01),

(p≤0.001)

Factor Type: A = Audiologic, B = Biographic, C = Cognitive, EP = Electrode Placement

Abbreviations: CI = cochlear implant, Elect = electrode(s), HA = hearing aid, HL = hearing loss, PC = principal component, Pos = position, Recog = recognition, Sent = sentence, SFT = sound-field threshold, SPHL = severe-to-profound hearing loss, ST = scala tympani, ST+Mid = sum of electrodes in ST and Mid Pos, SV = scala vestibuli

Biographic/Audiologic Factors

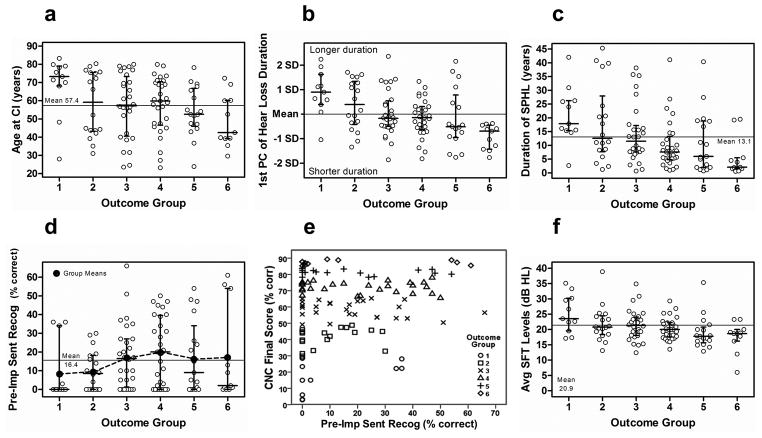

Figure 7 (panels a–d, f) displays individual participant data for Groups 1–6 for select biographic/audiologic factors. The median for each group is shown by the longer horizontal bar. The error bars with short tick marks represent the quartiles above and below the median. Individual data points are shown by the open symbols. The horizontal line fully traversing each graph is the grand mean across groups. This same style is repeated for Figures 8 and 10. Age at CI was significantly and negatively related to performance across outcome groups as plotted in Figure 7a. The greatest deviations from the grand mean across all participants for Age at CI existed in Group 1 (lowest performers) and Group 6 (highest performers). Education Level, while found to be positively and significantly related to outcome group (Table 6), was also significantly and negatively correlated with Age at CI (ρs = −0.29, p = 0.002, 2-tailed). Further examination of this latter relationship indicated that the older participants (≥ 65 years) had on average fewer years of schooling (≤ 12 years), whereas younger participants (< 65 years) had more (> 12 years). Consequently, the effect of Education Level on outcome was suspected to be secondary to the effect of Age of CI and is addressed again later, after controlling for age effects.

Figure 7.

Scatter plots of select biographic/audiologic factors plotted in relation to the six outcome groups, Group 1 (poorest performers) and Group 6 (highest performers) (panels a–d, f). Panel (e) is a scatter plot of Pre-Implant Sentence Recognition vs. CNC Final Score for all participants. The different symbols represent the six outcome groups.

Figure 8.

Scatter plots of select electrode position factors in relation to the six outcome groups.

Figure 10.

Scatter plots of the 1st PC of Cognitive Factors (raw data) and 1st PC of Cognitive Factors (standardized data) in relation to the six outcome groups.

The audiologic factors of Duration of HL, Duration of Hearing Aid (HA) Use, and Duration of SPHL were each significantly and negatively related to performance across outcome groups. Moreover, these three factors were each significantly correlated with one another (p ≤ 0.001); therefore, a composite variable, 1st PC of Hearing Loss Duration, was computed for these three factors explaining 65% of the variance of the raw measures. Hearing Loss Duration was found to be significantly and negatively related to outcome group as expected (p <0.001). The variation across outcome groups for the 1st PC of Hearing Loss Duration and the more familiar Duration of SPHL are plotted in Figures 7b and 7c, respectively. Similar to the pattern seen for Age at CI, the greatest deviations from the grand means for these related factors are in the extremes with Group 1 having longer and Groups 4, 5 and 6 having shorter periods of hearing loss and/or SPHL prior to implantation.

Pre-implant, aided sentence recognition was also significantly related to outcome groups (Table 6). Figure 7d shows an increase in the medians from Group 1 (median = 0%) to Group 4 (median = 20%), then a decrease across Groups 5 and 6. From Group 1 to 6, there is a general increase in the range of scores. This disassociation between ranges and medians is due to a large floor effect in the data with many participants having Pre-Implant Sentence Recognition scores of 0%. Mean sentence recognition scores for each outcome group (filled circles) are also included in Figure 7d and tend to rise with increasing outcome. To better illustrate the relationship of Pre-Implant Sentence Recognition with CI outcome, Figure 7e shows a scatter plot of Pre-Implant Sentence Recognition scores versus CNC Final Scores for all 114 participants. The figure indicates a wide range of CNC Final Scores (3–89%) for participants with Pre-Implant Sentence Recognition of 0%. However, as participants’ Pre-Implant Sentence Recognition increased above 0%, a corresponding increase in CNC Final Scores was seen.

FM tone, SFT levels obtained with the CI varied significantly across outcome groups as indicated in Figure 7f. Higher performers had significantly lower CI SFT Levels averaged across frequencies (250–6000 Hz) at three months post-initial activation compared to poorer performers. As previously seen, participants in Group 1 and Groups 5 and 6 deviated most from the grand mean.

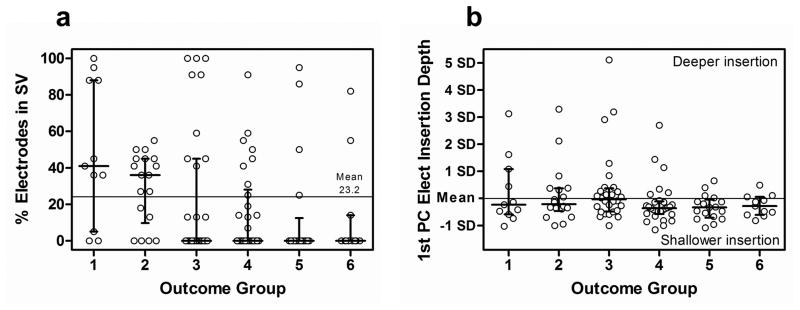

Electrode Position Factors

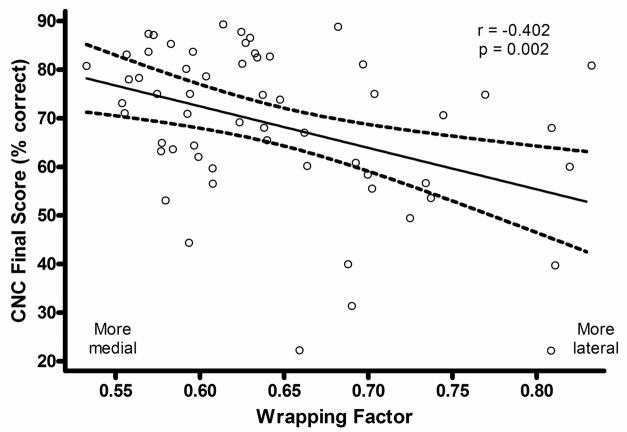

A number of measures associated with electrode position were found to be significantly related to the outcome groups (Table 6). These fall into the general categories of scalar location (i.e. ST vs. SV) and insertion depth of the electrode array. In addition, the medio-lateral position (i.e. perimodiolar position) of the electrode array, described by the Wrapping Factor metric, was significantly related to CNC Final Score in a separate analysis for participants with ST insertions (Table 5).

Scalar location of the array is described by four measures of the percentage of total contacts in four scalar locations including (1) ST (% Electrodes in ST), (2) a mid position approximating the basilar membrane (% Electrodes in Mid Position), (3) the summation of contacts in ST or the mid position (% Electrodes in ST + Mid Position), and (4) SV (% Electrodes in SV). Results are expressed in terms of the percentage of total contacts on the array as opposed to contact counts to accommodate the different arrays used in the study with either 16 or 22 total contacts. As indicated in Table 6, all four measures varied significantly across outcome group. The Percentage of Electrodes in SV was chosen as the best representation of array scalar location and is plotted against outcome group in Figure 8a. Scalar location had a significant effect with a grand mean of 23.2 % of all electrode contacts across all participants located in SV. As illustrated in Figure 8a, the median for participants in Groups 1 and 2 was above the grand mean, whereas the median for participants in Groups 3–6 was zero electrodes in SV. Electrode translocation into SV occurred in all outcome groups but occurred more often and with greater degree as group performance declined.

Length of Insertion along the Array Trajectory and the Angular Position of the Basal-most Electrode were significantly and inversely related to outcome group using the JT statistic (1-tailed) (Table 6). With the Spearman correlation (2-tailed), they were only related to outcome group as a strong trend but were significantly related to CNC Final Score (Table 5). These two metrics were combined into a single composite variable, 1st PC of Array Insertion Depth, explaining 92% of the variance of the metrics and plotted in Figure 8b. For the majority of participants, arrays were inserted to their intended design depth; however, deeper insertions occurred more frequently and to a greater degree in lower performing Groups 1–4 compared to Groups 5–6.

As noted, the Wrapping Factor describing medio-lateral electrode position was examined in a subgroup of participants whose electrodes were located only in ST which is the condition for which the metric is defined. Figure 9 is a scatter plot with linear regression line and ± 95% confidence intervals for the Wrapping Factor plotted in relation to CNC Final Score for the 59 participants. The regression coefficient is −0.402 (p = 0.002). Wrapping Factor varied significantly with CNC Final Score (ρs = −0.378, p = 0.003, 2-tailed) but not with CNC Initial, CNC RT or CNC Diff Scores (Table 5). Wrapping Factor covaried significantly with Angular Pos Apical Elect (ρs = −0.478, p < 0.001, 2-tailed), and 1st PC Array Insertion Depth (ρs = 0.275, p = 0.035, 2-tailed), but not with Angular Pos Basal Elect. This is consistent with more tightly-wrapped electrodes having greater angular distance between apical- and basal-most electrodes. Wrapping Factor also covaried with average CI SFT Levels (ρs = 0.264, p = 0.044, 2-tailed) and 1st PC HL Duration (ρs = 0.264, p = 0.044, 2-tailed) but no other factors. Partial correlation analysis controlling for these latter significant cofactors showed that Wrapping Factor remained significantly related to CNC Final Score (ρ= −0.298, p = 0.026, 2-tailed).

Figure 9.

A scatter plot of Wrapping Factor vs. CNC Final Score for 59 participants with electrode arrays positioned in ST.

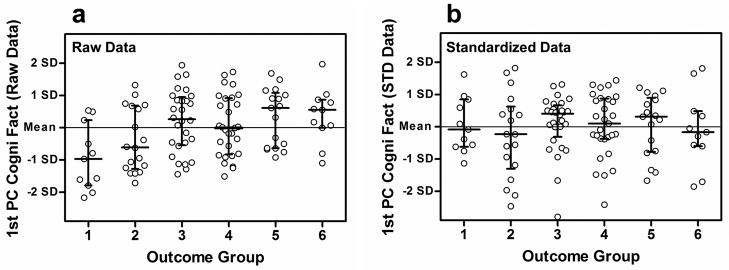

Cognitive Factors

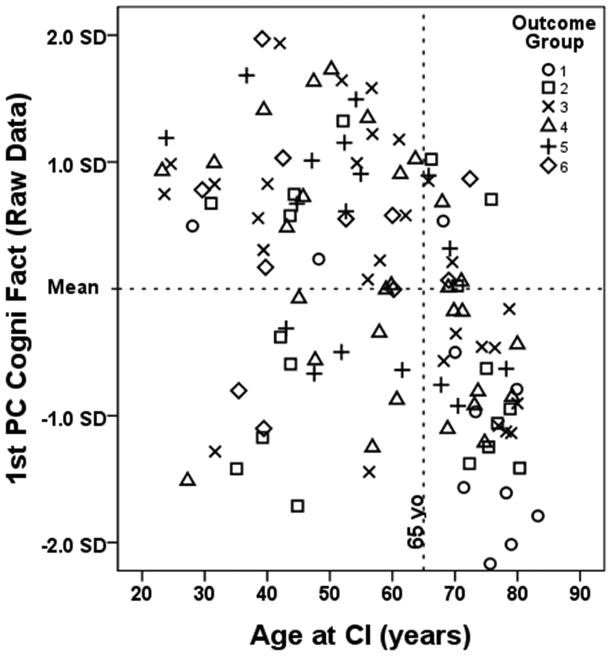

High correlations were observed among all cognitive measures except for the Trails A and Trails B tests. Consequently, the cognitive measures were reduced into two sets of 1st and 2nd PCs based on raw and standardized scores of the CVLT metrics (total words recalled, short delay free recall, long delay free recall) and the WAIS-III metrics of vocabulary, similarities and matrix reasoning. Raw CVLT measures were standardized according to gender, age and ethnicity per the method of Norman et al. (2000). Raw scores for the WAIS-III subtests were standardized using the tests’ normative tables. The 1st and 2nd cognitive PCs explained 55% and 22% of the variance of the raw measures and 45% and 32% of the variance of the standardized measures, respectively. The Spearman correlations in Table 4 indicate that only the 1st PC of the Cognitive Raw Scores was significantly related to any of the word recognition metrics or outcome groups. This relationship was maintained in the JT analysis as well (Table 6). Figures 10a and 10b show the 1st PCs of the raw and standardized cognitive scores plotted against outcome group, respectively. Figure 10a indicates that participants in Groups 1 and 2 have lower cognitive skills than the higher performing groups. Participants in Groups 5 and 6 have greater cognitive skills with medians well above the grand mean. In contrast, this relationship does not exist in Figure 10b after the cognitive data have been standardized for gender, age and ethnicity. Gender was not observed to be a significant factor in this ethnically homogenous study; consequently, it was concluded that a large component of lower performance was due to age effects mediated by cognitive decline.

Controlling for Effects of Age at Implantation

Figures 7a and 10a indicated that participants in Group 1 were the oldest and had the lowest cognitive scores. To more closely examine the relationship between age, cognition and outcome, Age at CI was plotted against the 1st PC of the Cognitive Raw Data for each participant in Figure 11. The outcome group for each participant is represented by a different symbol. Participants ≥ 65 years of age are to the right of the vertical dashed line and those < 65 are to the left. The lower right quadrant shows a group of 34 older participants who have lower than average cognitive scores. These older individuals, who composed 30% of all participants, represented 11% of participants in Groups 5–6, 29% of Groups 3–4, and 50% of Groups 1–2. A Spearman correlation analysis indicated that for individuals ≥ 65 years of age, CNC Final Score, Age at CI and the 1st PC Cognitive Raw Data were all significantly correlated with one another in all combinations (p ≤ .05; 2-tailed), whereas for those < 65, these factors were not correlated in any manner.

Figure 11.

Scatter plot of 1st PC of Cognitive Factors (raw data) vs. Age at CI for all 114 participants. The different symbols represent the six outcome groups. Participants to the left of the dashed vertical line are < 65 years old and those to the right are ≥ to 65 years.

To control for the effects of age, the analysis was repeated after Groups 1 and 6 were removed. Figure 7a illustrates that for Groups 2–5, age was roughly equally distributed about the grand mean. Six new performance groups based on the same percentage distributions were created from the remaining 92 participants originally in Groups 2–5. The age range for this subpopulation was 23 to 80 years (mean = 57 years, SD = 15.9 years). The number of participants in each group was as follows: Groups 1 and 6 (n = 9), Groups 2 and 5 (n = 14), and Groups 3 and 4 (n = 23). The Spearman and JT analyses were repeated on the six new outcome groups, and results are shown in Tables 7–9. After removing the original Groups 1 and 6, Age at CI was no longer significantly correlated with performance for the remaining 92 participants (Table 7) indicating that the effect of Age at CI had been successfully controlled. Note also that the 1st PC of Cognitive Raw Data no longer was correlated with performance. Table 8 shows the relation between Wrapping Factor and CNC Final Score for those participants with all electrodes in ST. A partial correlations analysis was used to control for Age at CI. The Wrapping Factor remained significant (ρ= −0.403, p = 0.002, 2-tailed).

Table 7.

Bivariate Spearman Correlation Coefficients and Significance Levels (2-Tailed) for Dependent Performance Measures and Independent Biographic, Audiologic, and Cognitive Measures for Age-Controlled Sub Population (N=92)

| Measures (Age-Controlled) | Outcome Group | CNC Final | CNC Initial | CNC RT to 90% of CNC Final | CNC Difference (Final-Initial) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dependent Performance Measures | |||||

| Outcome Group | 1 | ||||

| CNC Final | .963 *** | 1 | |||

| CNC Initial | .359 *** | .346 *** | 1 | ||

| CNC RT | −.340 ** | −.343 *** | ns | 1 | |

| CNC Diff | .447 *** | .491 *** | −.542 *** | ns | 1 |

| Independent Experimental Measures | |||||

| Biographic Measures | |||||

| Age at CI | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns |

| Educational Level | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns |

| Gender, Handedness, and CI Ear | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns |

| Audiologic Measures | |||||

| Age Onset HL | ns | ns | .313 ** | ns | −.348 *** |

| Duration of HL | ns | ns | .317 ** | ns | .277 ** |

| Duration of SPHL | −.247 * | −.205 * | −.288 ** | .229 * | ns |

| Duration of HA Use | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns |

| 1st PC HL Duration | ns | ns | −.255 * | ns‡ | ns |

| Pre-CI Sent Recog | ns | ns | ns | ns | .268 ** |

| Lipreading | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns |

| Unaided PTA in CI Ear (Pre-op) | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns |

| CI SFT Levels | −.237 * | −.215 * | ns | .323 ** | ns |

| Cognitive Measures | |||||

| 1st PC Raw Data | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns |

| 2nd PC Raw Data | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns |

| 1st PC STD Data for Age, Gender, Ethnicity | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns |

| 2nd PC STD Data | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns |

Significance: ns (p >0.05),

(p≤0.05),

(p≤0.01),

(p≤0.001)

Abbreviations: CI = cochlear implant, Diff = Difference, HA = hearing aid, HL = hearing loss, ns = not significant, PC = principal component, PTA = pure tone average, RT = rise time, SFT = sound-field threshold, SPHL = severe-to-profound hearing loss, STD = standardized

Table 9.

Factors that Varied Significantly (Jonckheere-Terpstra Test, 1-tailed) across Outcome Groups Arranged in Order of Decreasing Effect Size for Age-Controlled Sub Population (N=92)

| Factor Type | Factors | Std. J-T Statistic | Effect Size | Normalized Effect Size | Reciprocal of Normalized Effect Size |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EP | % Elect in SV§ | −2.55** | 0.27 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| EP | % Elect in ST+Mid Pos§ | 2.55** | 0.27 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| EP | % Elect in ST§ | 2.42** | 0.25 | 0.95 | 1.05 |

| EP | Angular Pos of Basal Elect* | −2.42* | 0.25 | 0.95 | 1.05 |

| EP | 1st PC Array Insertion Depth* | −2.39* | 0.25 | 0.94 | 1.06 |

| A | CI SFT Levels | −2.18* | 0.23 | 0.86 | 1.17 |

| EP | Array Trajectory Length* | −2.10* | 0.22 | 0.82 | 1.22 |

| A | Duration of SPHL# | −1.96* | 0.20 | 0.77 | 1.30 |

|

| |||||

| B | Age at CI | ns | |||

| B | Education Level | ns | |||

| C | 1st PC of Raw Cognitive Data | ns | |||

| A | 1st PC of HL Duration# | ns | |||

| A | Duration of HL# | ns | |||

| A | Duration of HA Use# | ns | |||

| A | Pre-CI Sent Recog | ns | |||

| EP | % Electrodes in Mid Pos§ | ns | |||

Significance:

(p≤0.05),

(p≤0.01)

Factor Type: A = Audiologic, B = Biographic, C = Cognitive, EP = Electrode Placement

Abbreviations: CI = cochlear implant, Elect = electrode(s), HA = hearing aid, HL = hearing loss, PC = principal component, Pos = position, Recog = recognition, Sent = sentence, SFT = sound-field threshold, SPHL = severe-to-profound hearing loss, ST = scala tympani, ST+Mid = sum of electrodes in ST and Mid Pos, SV = scala vestibuli

Table 8.

Spearman Correlation Coefficients and Significance Levels (2-Tailed) for Dependent Performance Measures and Independent Measures of Electrode Position for Age-Controlled Sub Population

| Independent Measures (continued from Table 7) (Age-Controlled) | Outcome Group | CNC Final | CNC Initial | CNC RT to 90% of CNC Final | CNC Difference (Final-Initial) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Scalar Location (Bivariant correlation analysis, N=92) | |||||

| % Elect in ST | .217 * | .265 * | ns | ns | ns |

| % Elect in Mid Pos | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns |

| % Elect in ST+Mid | .265 * | .271 ** | ns | ns | ns |

| % Elect in SV | −.265 * | −.271 ** | ns | ns | ns |

| Insertion Depth (Bivariant correlation analysis, N=92) | |||||

| Array Trajectory Length | ns | −.228 * | −.249 * | ns | ns |

| Angular Pos Apical Elect | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns |

| Angular Pos Basal Elect | −.216 * | −.276 ** | ns | ns | ns |

| 1st PC Array Insertion Depth | −.210 * | −.266 ** | ns | ns | ns |

| Medio-lateral Position for Array Insertions with All Electrodes in ST (Partial correlation analysis controlling for Age, N=59) | |||||

| Wrapping Factor | na | −.403 ** | ns | ns | ns |

Significance: ns (p >0.05),

(p≤0.05),

(p≤0.01)

Abbreviations: Elect = electrode(s), Mid Pos = position in middle of scalar cross section approximately at the level of the basilar membrane, na = not applicable, ns = not significant, Pos = position, PC = principal component, RT = rise time, ST = scala tympani, ST+Mid = sum of electrodes in ST and Mid Pos, SV = scala vestibuli

The JT analysis (Table 9) revealed that most of the electrode position factors as well as Duration of SPHL were still significantly related to outcome groups. The factors which remain significant are listed in the upper part of Table 9 in order of decreasing effect size. Note the ordering of the significant factors has changed after controlling for age effects. The factors no longer significant are listed in the lower portion of Table 9 by order of general factor type (i.e. biographic, audiologic, etc). The factors no longer significantly related to outcome groups after controlling for age were largely expected based on the participants eliminated from the original population. Education Level and Cognitive abilities of older participants were lower than for younger participants. Older participants had longer Duration of HL and longer Duration of HA Use than younger participants. Pre-Implant Sentence Recognition no longer being related to performance was somewhat surprising as there was little difference between group mean sentence scores for those < 65 (18%, SD = 18%) and for those ≥ 65 (13%, SD = 18%); although, 27% of participants < 65 scored 0% on sentences pre-implant, whereas 36% of those ≥ 65 scored 0%. In general, controlling for age confirmed our suspicion that the predominant effect of Age at CI was the reduction in performance due to cognitive ability.

DISCUSSION

Outcome Measures

The 114 postlingually-deaf CI recipients participating in this study had a wide range of post-implant word recognition abilities (Figure 5). This wide variability across CI users is a long-standing issue for the field and makes it difficult to counsel patients regarding their potential outcomes with a CI; disappointment with performance can occur when expectations are not met. In addition, understanding factors that affect performance may influence surgical technique, device design, device fitting and post-implant aural rehabilitation. To closely examine the range in performance seen in this study and the underlying contributing factors, participants were divided into six outcome groups based on the percentile ranking of their CNC Final Score (Figure 4). Overall, the grand mean CNC Initial Score, CNC Final Score, and CNC RT was 23.3%, 61.5%, and 6.3 months, respectively. Table 3 shows the variability across the six outcome groups and illustrates that postlingually-deaf, adult CI users achieve diverse performance levels and demonstrate different degrees of progress at various rates over time.

Biographic/Audiologic Factors

In earlier studies examining factors that affect CI outcomes, length of deafness has consistently been inversely related to outcome (Blamey et al. 1996; Rubinstein et al. 1999; Friedland et al. 2003; UK Cochlear Implant Study Group 2004). Similarly, in the current study the lower performing groups had longer Duration of SPHL than the higher performing groups (Figure 7c). In addition, Duration of HL, Duration of SPHL as well as the 1st PC of Hearing Loss Duration were inversely correlated with CNC Initial and CNC Final Scores and positively correlated to CNC RT. While length of deafness is inarguably a primary factor related to CI outcome, Age at CI as a factor predictive of outcome is divisive among studies. The studies also differ in their definition of “younger” and “older” and length of CI use among participants. Blamey et al. (1996) found poorer speech recognition for older participants, mainly for those over age 60. Using an age division of 65 years, Friedland et al. (2010) reported significantly higher speech recognition scores at one year post-implant for younger CI users (< 65 years). In contrast, Budenz et al. (2011) observed no difference in speech recognition scores at two years post-implant between younger (< 70 years) and older (≥ 70 years) CI recipients. Furthermore, Carlson et al. (2010) found no differences in monosyllabic word or sentence in noise scores between CI users ≥ 80 years of age (n = 31) and those 18–79 years of age (n = 149). The results of the current study indicated that Age at CI varied significantly across outcome groups with participants in the lowest performing Group 1 being the oldest. Moreover, a significant difference in mean performance between participants < 65 years of age (CNC Final Score = 67%) and those ≥ 65 years of age (CNC Final Score = 54%) was seen (p<0.001). Choosing age 65 as the division between groups was based on the scatter plot in Figure 11. A natural division occurred at age 65 with a cluster of participants older than 65 falling below the mean cognitive score. To determine if the selected cut-off age changed the results of the current data, participants were divided based on various ages (e.g. < 50 and ≥ 50; < 55 and ≥ 55; < 60 and ≥ 60; < 65 and ≥ 65; and < 70 and ≥ 70). Statistically significant differences (p < 0.05) in mean CNC Final Scores were seen between all age divisions except those participants grouped as < 50 and ≥ 50. Furthermore, the largest F-value for the above comparisons was found for age 65, suggesting that 65 is a reasonable age division for evaluating onset of cognitive effects on CI performance.

To optimize CI performance in everyday life, soft speech/sound needs to be audible. Previous research has shown that lower CI SFT levels were significantly correlated with better speech recognition at conversational (60 dB SPL) and soft (50 dB SPL) presentation levels (Firszt et al. 2004; Davidson et al. 2009). Recently, Geers and colleagues (Reference Note 1) found higher speech recognition scores for children (n = 60) with lower CI SFT levels. These findings are in agreement with the current results. Mean CI SFT Levels (averaged across frequencies [250 to 6000 Hz]) were negatively correlated with CNC Initial Score, CNC Final Score, and positively correlated with CNC RT (Table 4). Furthermore, CI SFT Levels were significantly related to outcome groups; that is, better performers had lower SFT levels (Figure 7f). Group 1 had mean SFT levels < 26 dB HL. These levels ensured the audibility of the test materials. Group 6 had mean SFT levels < 20 dB HL. However, Group 6 was younger and had fewer years of SPHL than Group 1. It is possible that participants in Group 6 preferred and could tolerate more sound in daily life than those in Group 1. This being said, even after Groups 1 and 6 were removed to control for age-effects, CI SFT Levels remained significantly and negatively related to performance (Tables 7 and 9). These results illustrate the importance of programming the CI speech processor to attain FM-tone SFT levels of approximately 20 dB HL across the frequency range to promote optimal performance.

Analogous to the results of Rubinstein et al. (1999), the current study found a significant relationship between Pre-Implant Sentence Recognition and outcome groups (Table 6) with higher performing groups having higher Pre-Implant Sentence Recognition than lower performing groups. Figure 7e shows a wide range of CNC Final Scores for participants with Pre-Implant Sentence Recognition of 0% indicating that low pre-implant sentence scores do not preclude the possibility of higher outcomes; whereas Pre-Implant Sentence Recognition above 0% does suggest more favorable outcomes. Pre-Implant Sentence Recognition, even limited, may indicate ganglion cell survival (Rubinstein et al. 1999), functional auditory memory (Heydebrand et al. 2007), and the likelihood of preserving normal phonological processing (Lazard et al. 2010); all of which may contribute to better CI outcomes.

Electrode Position Factors

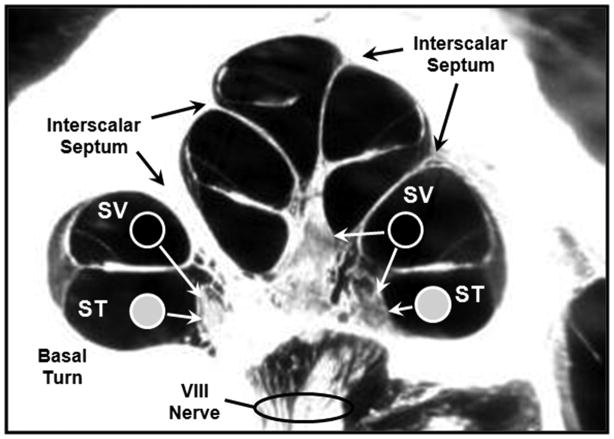

The results of this study indicate that the position of the electrode array within the cochlea contributes to CI outcome. Variation of electrode position in terms of ST vs. SV location, medio-lateral position of the array, and depth of insertion have been addressed. CNC Final Scores were higher when more electrodes were located in ST compared to SV. Note that neither SV nor ST position were correlated with CNC Initial Score (Table 5), but both were correlated with CNC Final Score, CNC RT, CNC Diff Score as well with outcome group. These results agree with those of Aschendorff et al. (2007), Skinner et al. (2007), and Finley et al. (2008). There are several possible mechanisms by which SV placement may affect outcomes. Figure 12 is a mid-modiolar section through the cochlea and illustrates differences seen between scalar locations. Monopolar-coupled electrodes located in ST (filled circles) most likely stimulate ganglion cells in the immediate scalar turn. When monopolar-coupled electrodes are positioned in SV (open circles), they are more likely to stimulate ganglion cells in the next, more-apical turn in addition to those in the immediate turn, except in the portion of the basal turn (BT) that is separated from the upper cochlear spiral by the thickened, bony, interscalar septum. The potential of electrodes located in SV to stimulate ganglion cells in more than one cochlear turn contributes to cross-turn stimulation which can lead to pitch confusions and diminished speech recognition (Finley et al. 2008). Additionally, an electrode array that enters SV or transitions from ST to SV may cause damage to the osseous spiral lamina, basilar membrane, spiral ligament, and Reisner’s membrane (Skinner et al. 2007). Current clinical imaging techniques cannot resolve damage to these structures; however, Leake et al. (1999) have shown through animal studies that trauma to cochlear structures may result in a decrease in spiral ganglion cells in the damaged region. Post mortem studies of spiral ganglion cells have not, however, shown a positive relationship between survival and outcome (Kahn et al. 2005; Fayad and Linthicum 2006).

Figure 12.

A mid-modiolar cochlear cross section showing a hypothetical ST electrode array placment (filled circles) compared to placement of an electrode array translocated to SV (open circles).

The Wrapping Factor was inversely correlated with CNC Final Score for participants with electrodes implanted in ST indicating that positioning of the electrode array closer to the modiolar wall is related to higher outcomes (Figure 9). These results are similar to those found by van der Beek and colleagues (2005) who compared speech perception scores for Clarion CII HiFocus I implant recipients with positioner (n = 25) and without positioner (n = 20). Significantly higher word and phoneme scores were found for those with the positioner at three, six and twelve months post implant. Multi-slice, CT imaging verified that electrode arrays with the positioner were closer to the modiolus, especially in the basal end of the cochlea, than those arrays without the positioner. The effect of the positioner being greater at the basal location was also observed when recording electrical auditory brainstem responses, specifically Wave V, before and after placement of the positioner during surgery (Firszt et al. 2003). Wave V thresholds were lower and amplitudes larger for the basal location after the positioner was placed resulting in less electrical current needed for stimulation of an intracochlear electrode. In van der Beek et al. (2005), the arrays with the positioner were also more deeply inserted into the cochlea than those without the positioner, but the location of the basal electrode contacts were similar for both groups. The authors hypothesize that with the array closer to the modiolus “spatial selectivity” is enhanced. That is, electrode contacts that are in close proximity to the ganglion cells have a better chance of stimulating a more specific tonotopic region of the cochlea than electrode contacts that are located farther away providing better discrimination between electrodes and improved speech perception. Furthermore, with perimodiolar placement, apical electrode contacts are more deeply inserted compared to a lateral placement; consequently, the array spans a greater length of the cochlea. This in turn may provide a better approximation to the normal frequency to place mapping in the cochlea as well as access to a greater population of surviving spiral ganglion cells providing better speech perception. These current and previous results suggest that a device with a perimodiolar electrode array may enhance CI performance.