Abstract

Chédiak-Higashi syndrome (CHS) is an extremely rare autosomal recessive immunodeficiency disorder. Approximately 200 cases have been reported worldwide. To the best of our knowledge, not more than 10 cases have been reported from India. Herein we are reporting a case of CHS in one-and-half-year-old boy who presented to us in the accelerated phase of disease. Other syndromes presenting with similar clinical features have also been discussed.

Keywords: Silvery hair syndrome, Chédiak-Higashi syndrome, Granular abnormality, Immunodeficiency disorder

Introduction

Chédiak-Higashi syndrome (CHS) is a rare childhood autosomal recessive immunodeficiency disorder described by Beguzz (1943), Steinberk (1948), Chédiak (1952) and Higashi (1954) [10]. About 200 cases of CHS have been reported in the world literature [2, 5]. In India, the first case of CHS was reported from Bangalore (1982) and till the year 2000 only five cases have been reported [3]. Symptoms of CHS usually occur soon after birth or in children younger than 5 years. Clinically it is characterized by occulocutaneous albinism, photophobia, silver gray hypopigmented hair and recurrent pyogenic infections particularly of skin, respiratory tract and gastrointestinal tract due to functional abnormality of neutrophils. Diagnosis of CHS can be done by finding characteristic giant cytoplasmic granules in all the granule-containing cells of the body, particularly in white blood cells (WBC) of the blood and the bone marrow. In the terminal phase it is characterized by non malignant lympho-histiocytic infiltration of multiple organs (pseudolymphoma). This accelerated lymphoma-like phase is precipitated by viral infections particularly Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) and patient develops severe anaemia, bleeding manifestations, organomegaly and overwhelming infections leading to death. Death usually occurs in first decade of life in 80% cases. The remaining 20% patients who survive adulthood develop progressive neurologic dysfunction including peripheral neuropathy, both axonal and demyelinating type. Herein we report a case of CHS in one-and-half-year-old boy who presented to us in the accelerated phase of disease. The case is being reported due to its extreme rarity. The differential diagnosis is also discussed with few other syndromes presenting with similar clinical features [4, 7–9].

Case Report

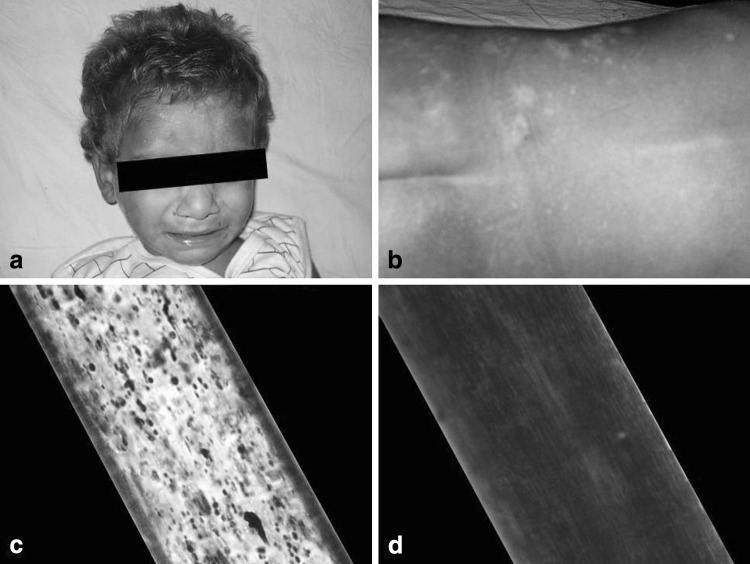

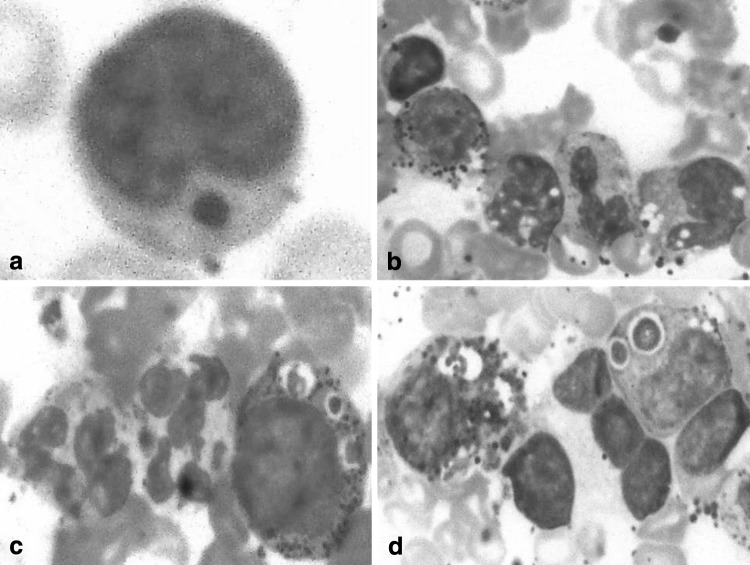

A one-and-half-year-old boy, born of a non-consanguinous marriage, presented to us with complaints of high-grade fever, diarrhea, rapid breathing and progressive distension of the abdomen for last 7 days. Clinical examination revealed mild pallor, oral thrush, angular cheilosis, micrognathia, low-set right ear, photophobia, marked bilateral cervical, submandibular and axillary lymphadenopathy and hepatosplenomegaly 5 cm firm, smooth and non-tender. Skin examination was remarkable with patchy hypopigmentation around face, trunk, back, abdomen, perianal region, hands and feet along with hypopigmented silver gray hair (Fig. 1a–b). Past history of the patient was notable for frequent chest infections, draining bilateral ears and high-grade fever since birth. He achieved normal developmental mile stones up to the age of 1 year, thereafter, his weight and development started to decline. His family history revealed parents, one elder brother and one elder sister to be normal. However, one elder male sibling died undiagnosed at the age of one-month due to repeated infections. A chest x-ray showed consolidation in bilateral lung fields. Laboratory investigations revealed hemoglobin 5.5 g/dL, total leukocyte count 3.7 × 103/μL, platelet count 80 × 103/μL. The general blood picture showed differential leukocyte count N10L80MY7MM3. The lymphocytes were large and almost all of them contained a single, large, round-to-oval, reddish coloured inclusion body in the cytoplasm (Fig. 2a). Because of neutropenia, no abnormality in the cytoplasm of neutrophils could be made out. Red blood cells (RBC) were normocytic normochromic. Platelets were reduced in number with many giant platelets exhibiting coarse granules. Bone marrow examination revealed hypercellular smears with M:E ratio 6:1, erythropoiesis normoblastic. Myeloid series of cells were distributed normally but morphologically majority of them showed giant (some as big as the size of RBCs) intracytoplasmic round-to-oval inclusions, phagolysosomes and features of haemohistiophagocytosis which are pathognomonic of this disease (Fig. 2b–d). Megakaryocytes were seen normally. As the haematological findings were indicative of CHS, the patient was re-assessed clinically and subjected to further examinations. Microscopic examination of the hair shaft was done, which showed small, regularly distributed melanin aggregates in the medulla (Fig. 1c). A coagulation analysis with platelet function tests was also done. Prothrombin time (13.4 s), activated partial thromboplastin time (36.8 s) and plasma fibrinogen level (250 mg%)—all were within normal limits. Platelet factor-3 activity was prolonged by 10 s and platelet aggregation with both adenosine di-phosphate (ADP) and adrenaline was reduced to 50.2 and 45.8%, respectively. IgM antibody to EBV was positive. Fine needle aspiration cytology and biopsy of the lymph nodes showed features of reactive lymphoid hyperplasia. Parents of the patient refused for skin biopsy to evaluate for abnormal granules in melanosomes. Based on clinical presentation and haematological findings, a diagnosis of accelerated phase of CHS was made. The patient was managed with intravenous antibiotics, vitamin C and blood transfusions. He was discharged in a stable and satisfactory condition with an advice to regular follow-up.

Fig. 1.

a, b Silvery gray hair and hypopigmentation of skin of the patient. Light microscopic examination of hair shaft of the patient (c) compared to normal hair (d)

Fig. 2.

a–d Peripheral blood and bone marrow smears showing abnormal granules (Leishman stain ×1000)

Discussion

Our patient presented with typical clinical features of CHS in accelerated phase. The accelerated phase is characterized by extreme lympho-proliferation believed to be due to viral infections, especially EBV. At presentation, the patient had severe neutropenia, therefore, the characteristic abnormal granules were difficult to identify in neutrophils. However, the diagnosis of CHS was clinched by observing a single large eosinophilic inclusion body (the granule) in almost all of the lymphocytes in peripheral smear. The bone marrow aspirate smears were characteristic of CHS, showing abnormal granules in all stages of myeloid cell maturation, lymphocytes and monocytes along with features of haemohistiophagocytosis. These massive lysosomal inclusions are formed through a combined process of fusion, cytoplasmic injury and phagocytosis due to microtubular defect [6]. Increased susceptibility to infection specially skin and respiratory tract is due to the defective function of neutrophils i.e., poor mobilization from bone marrow, decreased deformability resulting in defective chemotaxis and delayed phagolysosomal fusion resulting in impaired bactericidal activity. Our patient also showed mild thrombocytopenia with defective platelet aggregation with ADP and adrenaline, however, no defect in coagulogram was observed and patient had no bleeding manifestations. Bleeding manifestations with thrombocytopenia, altered coagulogram with features of disseminated intravascular coagulation and enhanced fibrinolysis have been observed by some workers in patients with accelerated phase of CHS [1]. It is pertinent to mention that CHS should be differentiated from pseudo-CHS where abnormal granules are seen only in granulocytic cells in some cases of acute myeloid leukaemias [6]. Granular abnormality is never seen in other types of WBCs in pseudo-CHS. Further, two other extremely rare syndromes i.e. Griscelli syndrome (GS) and Elejalde syndrome (ES) also clinically mimic CHS [4, 7–9]. Both are characterized by skin hypopigmentation, silvery gray hair, central nervous system dysfunction in infancy and childhood and very large unevenly distributed granules of melanin in the hair shaft and skin. But the presence of giant abnormal granules in all types of WBCs e.g., granulocytes, lymphocytes and monocytes is the single most important differentiating feature of CHS from these two syndromes, which characteristically lack them. All these syndromes (CHS, GS, and ES) have autosomal recessive transmission and therefore parental consanguinity is often obtained. The other features of these syndromes are compared (Table 1) [4, 8, 9].

Table 1.

Comparison of Chédiak-Higashi syndrome (CHS), Griscelli syndrome (GS) and Elejalde syndrome (ES)

| Features | CHS | GS | ES |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mode of inheritance | AR | AR | AR |

| Gene present on | Chromosome 1 | Chromosome 15 | Not known |

| Incidence | Rare | Extremely rare | Extremely rare |

| Clinical features | |||

| Skin hypopigmentation | + | + | + |

| Silvery gray hair | + | + | + |

| Neurological impairment | + | + | ++ |

| Immunodeficiency | + | + | − |

| Investigations | |||

| Giant intracytoplasmic granules in all leukocytes | + | − | − |

| Clusters of melanin pigment on hair microscopy | Small, evenly distributed melanin aggregates | Very large (8–10 times larger than in CHS) unevenly distributed melanin aggregates | Very large unevenly distributed melanin aggregates |

| Impaired transfer of melanin to keratinocytes on skin biopsy | + | + | + |

| Haemophagocytic syndrome | + | + | − |

| Treatment of choice | BMT | BMT | Supportive & symptomatic |

AR Autosomal recessive

The gene implicated in CHS is located on chromosome 1 (1q42–43) and encodes a protein called lysosomal trafficking regulator (formerly termed LYST, but currently termed CHS1), which is defective in patients with CHS. This protein is responsible for synthesis, storage and maintenance of secretory granules in various types of granule-containing cells of the body, e.g., WBCs, melanocytes, fibroblasts, endothelial cells, Schwann cells, neurons, hepatocytes, renal tubular cells, pneumocytes, etc. It is recommended that parents and all the siblings of the patients of CHS should be screened for the presence of giant granules in the leukocytes for early diagnosis. Prenatal diagnosis can be done by examination of hair from fetal scalp biopsy specimens and leukocytes from fetal blood samples. Allogenic bone marrow transplantation (BMT) is the treatment of choice when performed early in the course of disease before the onset of accelerated phase.

Contributor Information

Shashikant C. U. Patne, Email: scup.pathology08@gmail.com

Sandip Kumar, Email: krsandy2007@rediff.com.

Jyoti Shukla, Phone: +0542-2309222, Email: jyotishuklabhu@yahoo.co.in.

References

- 1.Ahluwalia J, Pattari S, Trehan A, Marwaha RK, Garewal G. Accelerated phase at initial presentation: an uncommon occurrence in Chédiak-Higashi syndrome. Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2003;20:563–567. doi: 10.1080/08880010390232790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Al-Sheyyab M, Daoud AS, El-Shanti H. Chediak-Higashi syndrome: a report of eight cases from three families. Indian Pediatr. 2000;37:69–75. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kumar P, Rao KS, Shashikala P, Chandrashekar HR, Banapurmath CR. Chediak-Higashi syndrome. Indian J Pediatr. 2000;67:595–597. doi: 10.1007/BF02758492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Malhotra AK, Bhaskar G, Nanda M, Kabra M, Singh MK, Ramam M. Griscelli syndrome. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;55:337–340. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2005.11.1056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nowicki JR, Szarmach H. Chediak-Higashi syndrome. http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/1114607-print. Accessed 15 Oct 2009

- 6.Rao S, Kar R, Saxena R. Pseudo Chediak-Higashi anomaly in acute myeolmonocytic leukemia. Indian J Pathol Microbiol. 2009;52:255–256. doi: 10.4103/0377-4929.48937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rath S, Jain V, Marwaha RK, Trehan A, Rajesh LS, Kumar V. Griscelli syndrome. Indian J Pediatr. 2004;71:173–175. doi: 10.1007/BF02723104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Scheinfeld NS, Johnson AM. Elejalde syndrome. http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/1069594-print. Accessed 11 Jan 2010

- 9.Sheela SR, Latha M, Injody SJ. Griscelli syndrome: Rab 27a mutation. Indian Pediatr. 2004;41:944–947. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Usha HN, Prabhu PD, Sridevi M, Baindur K, Balakrishnan CM. Indian Pediatr. 1994;31:1115–1119. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]