Abstract

Aging is an important factor in memory decline in aged animals and humans and in Alzheimer’s disease and is associated with the impairment of hippocampal long-term potentiation (LTP) and down-regulation of NR1/NR2B expression. Gaseous formaldehyde exposure is known to induce animal memory loss and human cognitive decline; however, it is unclear whether the concentrations of endogenous formaldehyde are elevated in the hippocampus and how excess formaldehyde affects LTP and memory formation during the aging process. In the present study, we report that hippocampal formaldehyde accumulated in memory-deteriorating diseases such as age-related dementia. Spatial memory performance was gradually impaired in normal Sprague–Dawley rats by persistent intraperitoneal injection with formaldehyde. Furthermore, excess formaldehyde treatment suppressed the hippocampal LTP formation by blocking N-methyl-d-aspartate (NMDA) receptor. Chronic excess formaldehyde treatment over a period of 30 days markedly decreased the viability of the hippocampus and down-regulated the expression of the NR1 and NR2B subunits of the NMDA receptor. Our results indicate that excess endogenous formaldehyde is a critical factor in memory loss in age-related memory-deteriorating diseases.

Keywords: Alzheimer’s disease (AD), Aging, Endogenous formaldehyde, Long-term potentiation (LTP), Long-term memory (LTM), NMDA receptor

Introduction

It is widely known that aging is an important factor in memory decline in aged animals and humans (McGahon et al. 1999) and a pathogenic factor for Alzheimer’s disease (AD) (Drachman 2006; Cummings 2008). Abundant evidence shows that memory decline occurs and hippocampal long-term potentiation (LTP) is impaired in aged animals (Almaguer et al. 2002; Chapman et al. 1999; Kamal et al. 2005) and memory-deteriorating animal models such as amyloid precursor protein (APP) transgenic mice (Gureviciene et al. 2004), APP/PS1 mice (Gengler et al. 2010), and senescence-accelerated-prone 8 mice (SAMP8) (López-Ramos et al. 2012). NR2B, one of the subunits of N-methyl-d-aspartate (NMDA) receptor, is critical in regulating the age-dependent synaptic plasticity and memory formation (Tang et al. 1999). In addition, expression of NR1 and NR2B markedly decreases in the hippocampus of APP transgenic mice, aged rats (Mesches et al. 2004), and AD patients (Amada et al. 2005; Hynd et al. 2004). However, which endogenous factors associated with the decline in NR1/NR2B expression contribute to memory impairment has not been ascertained.

Formaldehyde is present in the cytoplasm and nucleus of all cells (Kalapos 1999; Kalász 2003; Trézl et al. 1997; Tyihák et al. 1998). Using fluorescence high-performance liquid chromatography (Fluo-HPLC), we have shown that the levels of brain formaldehyde are about 0.2–0.4 mM, similar to the levels previously reported using gas chromatography/mass spectrometry (Heck et al. 1982; Tong et al. 2011). There is abundant evidence indicating that excess formaldehyde can impair memory. Exposure of rats to exogenous gaseous formaldehyde induces the accumulation of formaldehyde (Cui 1996), decreases the number of hippocampal neurons (Gurel et al. 2005), and leads to memory decline (Malek et al. 2003). Epidemiological investigations indicate that exogenous formaldehyde exposure causes human cognitive decline and is associated with neurofilament protein changes and demyelization in hippocampal neurons (Kilburn 1994; Kilburn et al. 1987; Perna et al. 2001). In addition, we have previously reported that brain tissues from AD animal models have abnormally high levels of formaldehyde (about 0.5 mM) and that treatment of normal mice with 0.5 mM formaldehyde induces marked memory decline (Tong et al. 2011). These diverse lines of evidence strongly suggest that excess endogenous formaldehyde is a pathogenic factor involved in memory decline.

To understand how excess formaldehyde induces memory decline, we first detected endogenous formaldehyde levels during the aging process and in age-related memory-deteriorating diseases. We then ascertained whether excess hippocampal formaldehyde affected LTP and spatial memory formation in Sprague–Dawley (SD) rats. In addition, we examined whether excess formaldehyde regulated NR1 and NR2B expression. Our results show that excess hippocampal formaldehyde suppresses LTP and spatial memory formation not only by non-specifically blocking NMDA receptor, but also by decreasing NMDA receptor expression.

Materials and methods

Reagents

All reagents were from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA) unless otherwise indicated.

Animal models and brain tissue collection

All animal experiments were carried out in accordance with the National Institutes of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals and were approved by the Biological Research Ethics Committee, Institute of Biophysics, Chinese Academy of Sciences (SYXK2010-127).

APP transgenic mice model

APP transgenic mice were obtained from the Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences (Beijing).

Diabetic rat model

Since Reisi and colleagues have demonstrated that streptozotocin (STZ)-induced diabetic SD rats show memory decline after 3 months (Reisi et al. 2009), this model was employed in this work. To induce diabetes in male SD rats (250 ~ 300 g), STZ was freshly dissolved in 0.05 M citrate buffer, pH 4.5, and a single intraperitoneal (i.p.) injection (150 mg/kg) was given to each animal. Animals whose blood glucose exceeded 200 mg/dl 24 h after treatment were considered diabetic (Abu-Abeeleh et al. 2010).

Human brain samples

Autopsy hippocampal and cortical tissues from healthy controls and Alzheimer’s disease patients were obtained from the Netherlands Brain Bank.

Intracerebroventricular formaldehyde injections

Three groups of SD rats were intracerebroventricularly (i.c.v.) injected with formaldehyde (normal saline, 0.3 and 0.5 mM, 5 μl, i.c.v. in 5 min) before high frequency electrical stimulation (HFS) for 30 min and were then subjected to electrophysiological experiments or hippocampal formaldehyde detection.

Acute formaldehyde injection for seven consecutive days

The normal male SD rats (250–300 g) were intraperitoneally (i.p.) administered with formaldehyde once a day at 0.5 mM formaldehyde (60 mg/kg) prior to Morris water maze training and were then used for memory behavior tests or formaldehyde level detection.

Chronic formaldehyde injection for 30 days

The normal male SD rats were intraperitoneally injected with 0.5 mM formaldehyde (i.p. 60 mg/kg) over a period of 30 consecutive days (Gurel et al. 2005; Tong et al. 2011). Hippocampal formaldehyde concentrations were then detected by Fluo-HPLC after completion of Morris water maze testing.

Hippocampal neuron and astrocyte culture in vitro

We prepared primary hippocampal neuron cultures from 18-day-old embryos, as described previously (Nie et al. 2007a). Medium from the mature hippocampal neuron culture (cultured for 14–16 days) was collected in order to detect formaldehyde concentration. Astrocytes were cultured as reported previously (Song et al. 2010).

Morris water maze behavioral test

Four groups of normal male SD rats were intraperitoneally injected with normal saline, 0.5 mM formaldehyde (i.p. 60 mg/kg), resveratrol (1 mM), or formaldehyde with resveratrol over a period of 30 consecutive days (Gurel et al. 2005; Tong et al. 2011). Spatial memory behaviors of rats were assessed by the Morris water maze test, as described previously (Morris 1984).

Quantification of extracellular formaldehyde by Fluo-HPLC

Drug-treated medium from cultured hippocampal neurons was collected and immediately placed on ice before storing at −70°C. After centrifugation (3,000 rpm, 4°C, 10 min), supernatants from the above culture medium samples and brain homogenates (weight of brain tissue/ultrapure water = 1:4) were analyzed by Fluo-HPLC as described (Luo et al. 2001).

Cytosolic free Ca2+ concentration in NR1/NR2B-transfected CHO cells in vitro

For transfection of pcDNA3.1–GFP–NR1a and pcDNA3.1–NR2B plasmids (gifts from Dr. Jianhong Luo, Zhejiang University, China), Chinese hamster ovary (CHO) cells were harvested after a brief trypsin digestion and seeded onto chambered cover glasses (LabTek, Nunc, USA) precoated with 20 μg/ml poly-l-lysine. Actively growing cells were transfected with these two plasmids using Lipofectamine plus (Life Technologies, Rockville, MD, USA). The cells transfected with pcDNA3.1 plasmid alone were set as control. After 16 ~ 24 h of culture, cells were loaded with 50 μM Fluo-3/AM (Molecular Probes) and incubated for 30 min at 37°C. Fluo-3/AM was excited at 488 nm, and its emitted fluorescence was collected at 515 nm. These cells were then treated with 0.2 mM NMDA plus 0.01 mM glycine or NMDA with formaldehyde at different concentrations (0, 0.3, and 0.5 mM). Changes in cytosolic free Ca2+ concentration ([Ca2+]i) in these cells were measured with a confocal laser scanning microscope (Leica Company Ltd, Germany) as described previously (Tong et al. 2010).

Recording hippocampal LTP in vivo

Electrophysiological recordings were performed as described in previous reports (Cheng et al. 2009; Zhang et al. 2009). The normal male SD rats (250–300 g) were placed in a stereotaxic frame and the recording electrode was positioned in the stratum radiatum of area CA1 (3.4 mm posterior to the bregma and 2.5 mm lateral to the midline); a bipolar concentric stimulating electrode was placed in the Schaffer collateral–commissural pathway (4.2 mm posterior to the bregma and 3.8 mm lateral to the midline) distal to the recording electrode.

Baseline stimulation (BS) for field excitatory postsynaptic potentials (fEPSPs)

Baseline fEPSPs were elicited by BS at intervals of 30 s at an intensity that elicited 50% of the maximal response. Baseline fEPSPs were monitored for at least 30 min prior to the induction of LTP to ensure a steady-state response.

HFS for LTP

LTP was induced using an HFS protocol consisting of 20 pulses at 100 Hz. A >50% increase in fEPSP amplitude from the baseline was considered as a significant LTP. Drug or normal saline intracerebroventricular injections (i.c.v. 5 μl, in 5 min) were carried out 30 min before different stimulations. After electrophysiological recordings, hippocampi from these different groups of rats were collected to detect formaldehyde concentration.

Hippocampal viability assays

Four groups of normal SD rats (250–300 g) were injected with normal saline, 0.5 mM formaldehyde (i.p. 60 mg/kg), resveratrol (1 mM), or formaldehyde with resveratrol, respectively, over a period of 30 consecutive days, and then hippocampal slices (300 μm) of these rats were dyed with an 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT) solution. Photomicrographs were typically obtained after 1 h of incubation with MTT as described in previous reports (Connelly et al. 2000).

Hippocampal neuron and astrocyte viability assays

Cell viability was assessed by the MTT assay as previously described (Tong et al. 2010). Hippocampal neurons and astrocytes were treated with various concentrations of formaldehyde for 3 h. An MTT solution was freshly prepared in complete medium at a concentration of 1 mg/ml. Absorbance at 540 nm was measured on a Multiscan MK3 spectrophotometer (Thermo, USA).

Western blotting

Control, formaldehyde-treated hippocampal neurons, and hippocampus samples were lysed with a protein extraction reagent (M-PER; Thermo Scientific, Rockford, IL, USA). Protein concentrations were determined with BCA protein assay reagent using a standard protocol. Equivalent amounts of proteins were separated on SDS-PAGE gels, transferred to nitrocellulose membranes (Millipore, Bedford, MD, USA), and incubated with antibodies to NR1 (1:2,000, Cell Signaling Technology, Inc. USA), NR2B (1:1,500), and AMPA (GluR 2/3/4) (1:2,000). β-actin was used as a gel-loading control. Protein bands were visualized after exposing the membranes to Kodak X-ray film and were quantified by densitometry. Results are presented as total integrated densitometric values.

Statistics

fEPSPs were expressed as a percentage of the mean baseline amplitude (set arbitrarily as 100%). Statistical comparisons of the LTP from control and drug-treated groups were carried out at 5, 30, and 60 min after HFS treatment. We determined the statistical significance of data by conducting an analysis of variance followed by the unpaired Student’s t test. The level for statistical significance was set at P < 0.05. Data are reported as means ± standard error.

Results

Endogenous formaldehyde concentrations increase in age-related memory-deteriorating diseases

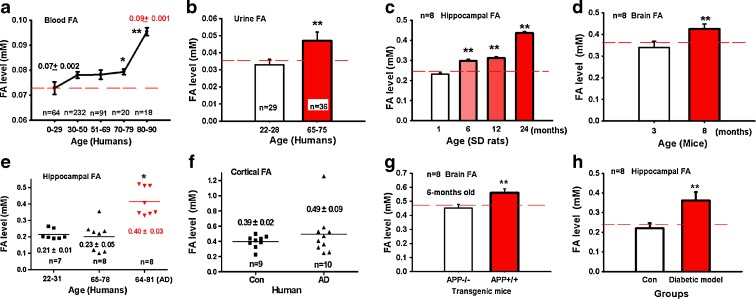

To determine whether endogenous formaldehyde is related to aging, we investigated the blood and urine formaldehyde levels of people of different ages (Fig. 1a, b). There was a slight increase in blood formaldehyde concentration with aging (from 0 to 70 years old); however, there was a marked elevation in the elderly group over 79 years old. Urine formaldehyde levels of elderly people (65–75 years old) were also significantly higher than those of young volunteers (22–28 years old) (P < 0.01). Since it is extremely difficult to obtain human brain samples from enough people of different ages, we detected the brain formaldehyde concentrations of SD rats and C57BL/6 mice at different ages in our experiments. As shown in Fig. 1c, d, hippocampal formaldehyde levels in rats aged 6–24 months were significantly higher than those of 1-month-old rats (P < 0.01), and brain formaldehyde levels of 8-month-old mice were higher than those of 3-month-old mice (P < 0.01). This indicates that endogenous formaldehyde levels increase with aging.

Fig. 1.

Endogenous formaldehyde is accumulated during aging and in some memory-deteriorating diseases. Formaldehyde levels in human blood (a) and urine (b) as aging. Formaldehyde levels in the hippocampus of SD rats (c), mouse brain (d); those in the hippocampus (e) and cortex (f) of patients with Alzheimer’s disease; and those in the brains of APP transgenic (hypomethylation of the APP gene) mice (g), and hippocampi of streptozotocin-induced diabetic SD rats (h). *P < 0.5; **P < 0.01

Alzheimer’s disease patients often suffer from progressively worsening memory problems. As shown in Fig. 1e, the hippocampal formaldehyde level of Alzheimer’s patients was significantly higher than that of age-matched controls or young people (P < 0.01). The cortical formaldehyde level of Alzheimer’s disease patients was slightly higher than that of controls, but this difference did not reach significance (Fig. 1f). Furthermore, the brain formaldehyde level of APP+/+ transgenic mice was significantly higher than that of APP−/− mice 6 months old (Fig. 1g). Since Reisi and colleagues have demonstrated that STZ-induced diabetic SD rats show memory decline (Reisi et al. 2009), we measured formaldehyde levels in the hippocampi of STZ-induced diabetic SD rats after 3 months. Similarly, there was a marked increase in hippocampal formaldehyde level of diabetic rats compared with controls (P < 0.01) (Fig. 1h). These data strongly suggest that excess formaldehyde (over 0.5 mM) in the brain is closely related with memory loss in these memory-deteriorating diseases.

Excess formaldehyde suppresses hippocampal LTP in vivo

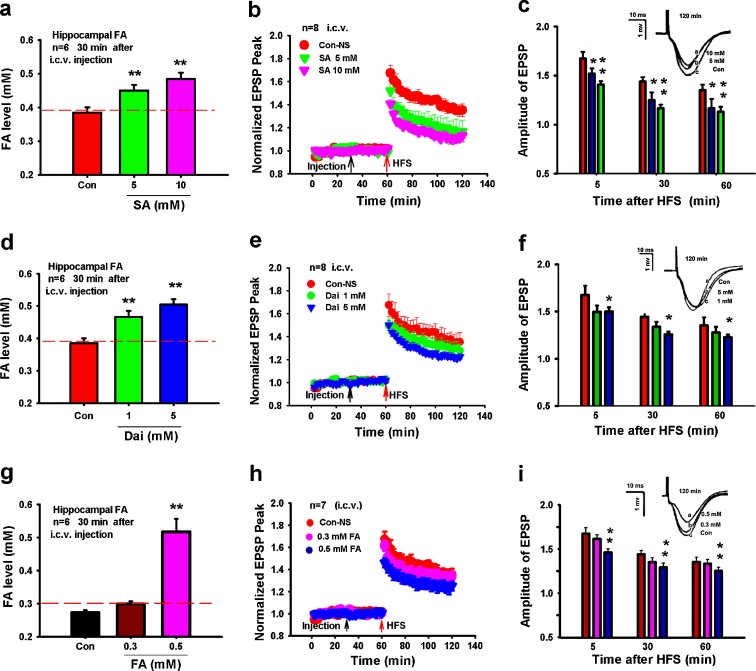

Accumulation of endogenous formaldehyde induces LTP suppression

We next used the inhibitors of the formaldehyde-degrading enzymes alcohol dehydrogenase 3 (ADH3) and aldehyde dehydrogenase 2 (ALDH2) (Teng et al. 2001) to examine whether excess formaldehyde affects LTP formation. Hippocampal formaldehyde levels increased to over 0.5 mM 30 min after rats had been injected i.c.v. with succinic acid (an inhibitor of ADH3) (Fig. 2a) (Denk et al. 1976), and a dose-dependent decrease of fEPSP amplitude was also observed (Fig. 2b, c). Injection of daidzin (a selective inhibitor of ALDH2) (Kollau et al. 2005) gave a similar result (Fig. 2d–f). These data suggest that the LTP suppression by excess hippocampal formaldehyde is associated with the inhibition of ADH3 or ALDH2 in vivo.

Fig. 2.

Excess endogenous formaldehyde suppresses the hippocampal LTP formation in vivo. Formaldehyde levels in hippocampi from rats treated with succinic acid (SA, an ADH3 inhibitor, i.c.v.) after 30 min (a). Effects of succinic acid on LTP (b). Statistical analyses of EPSP amplitude (c). Formaldehyde levels in hippocampi from rats treated with daidzin (Dai, an ALDH2 inhibitor, i.c.v.) after 30 min (d). Effects of daidzin on LTP (e). Statistical analyses of EPSP amplitude (f). Formaldehyde levels in hippocampi after these rats were intracerebroventricularly treated with excess formaldehyde for 30 min (g). Excess formaldehyde induces LTP suppression (h). Statistical analysis of EPSP amplitude (i). *P < 0.5; **P < 0.01

Direct injection with exogenous formaldehyde suppresses LTP formation

To further confirm the effect of excess hippocampal formaldehyde on LTP formation, different concentrations of formaldehyde (normal saline, 0.3 and 0.5 mM) were injected (i.c.v.) into SD rats. The hippocampal formaldehyde level rose to about 0.52 mM 30 min after injection (Fig. 2g), and the fEPSP amplitude was markedly reduced at this level of formaldehyde in vivo (P < 0.01) (Fig. 2h, i). Exogenous formaldehyde injections (0.5 mM) did not affect the baseline of the fEPSP recorded for 1 h post-injection (Fig. 2h). These data support our hypothesis that excess hippocampal formaldehyde suppresses the LTP formation in vivo.

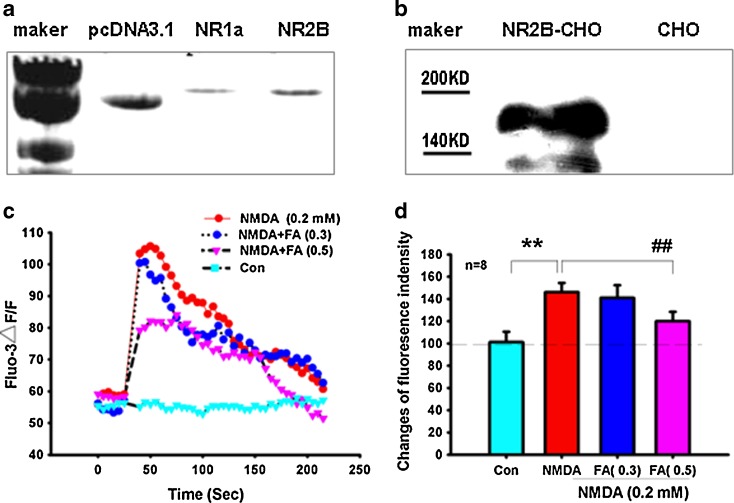

Excess formaldehyde blocks NMDA-induced elevation of intracellular [Ca2+]i in vitro

A previous study has suggested that formaldehyde may block NMDA receptor (McKenna and Melzack 2001). To explore whether this is the case, NR1 and NR2B expression plasmids (pcDNA3–GFP–NR1 and pcDNA3–NR2B) were co-transfected into CHO cells. Expression of these transfected plasmids was confirmed by agarose gel electrophoresis and western blotting (Fig. 3a, b). The effects of different concentrations of formaldehyde on the elevation of intracellular [Ca2+]i were then measured by confocal laser scanning microscopy. We found that excess formaldehyde non-specifically inhibited NMDA-induced Ca2+ influx (Fig. 3c, d). This result is similar to the report suggesting that excess ethanol inhibits NMDA-induced Ca2+ influx in NR1/NR2B-transfected HEK 293 cells (Blevins et al. 1997). Our results suggest that excess formaldehyde (0.5 mM) can non-specifically inhibit functions of the NR1/NR2B subunits of the NMDA receptor.

Fig. 3.

Excess formaldehyde non-specifically blocks the NMDA receptor in vitro. DNA bands of pcDNA3.1, NR1a, and NR2B (a). NR2B expression detected by western blotting (b). Effect of NMDA (0.2 mM) or NMDA and formaldehyde (0, 0.3, and 0.5 mM) on the [Ca2+]i fluorescence intensity of NR1/NR2B-transfected CHO cells (c). Statistical analysis of changes in fluorescence intensity (d). **P < 0.01 versus control group, ##P < 0.01 versus NMDA (0.2 mM) treatment group

Acute and chronic excess formaldehyde treatments impair spatial memory in rats

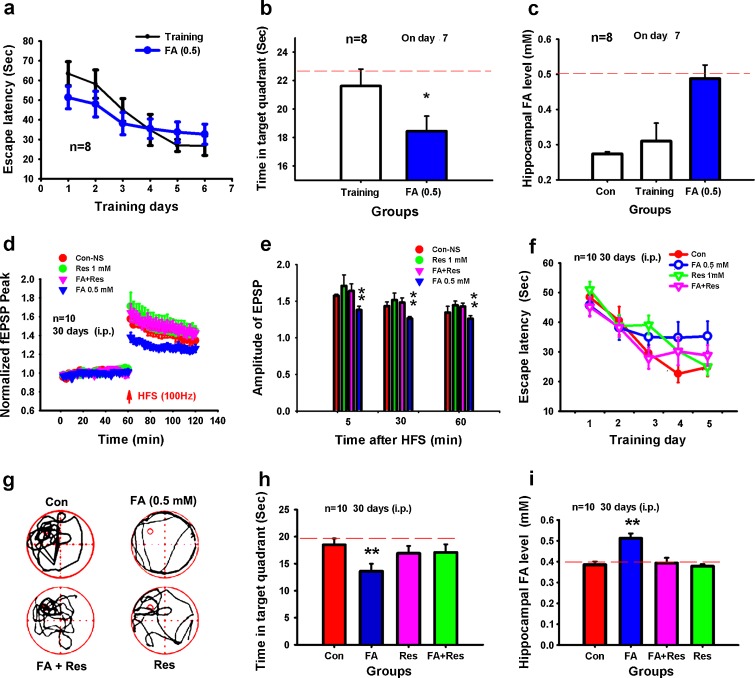

Acute injection with formaldehyde slows spatial memory formation

Since our results indicated that excess hippocampal formaldehyde induces LTP suppression (Fig. 2), excess formaldehyde might also affect the spatial memory of rats. To test this hypothesis, we treated SD rats with formaldehyde (0.5 mM, i.p. 60 mg/kg) over a period of 7 days. Spatial learning ability of the formaldehyde-treated rats was insignificantly gradually decreased (P > 0.05), but memory retrieval ability was markedly reduced (P < 0.05) (Fig. 4a, b) as hippocampal formaldehyde levels increased (Fig. 4c). This demonstrates that excess hippocampal formaldehyde inhibits spatial memory formation in rats.

Fig. 4.

Acute or chronic excess formaldehyde impairs spatial memory in rats. Escape latency in controls and rats injected with formaldehyde for 7 days (a). Time (seconds) spent in the target quadrant during probe trials (b). Formaldehyde levels in hippocampi from rats intraperitoneally treated with excess formaldehyde on day 7 (c). An exogenous supply of the formaldehyde scavenger resveratrol rescued LTP suppression by formaldehyde injection (i.p.) over 30 consecutive days (d). Statistical analysis of EPSP amplitude (e). Escape time (seconds) in these four groups (f). The swimming track and the time (seconds) spent in the target quadrant during probe trials (g, h). Formaldehyde levels in the hippocampus of rats intraperitoneally treated with different reagents on day 30 (i). *P < 0.5; **P < 0.01

Chronic injection with formaldehyde induces spatial memory deficits

The above experiments show that acute excess formaldehyde (0.5 mM) treatment can reduce fEPSP amplitude and inhibit spatial memory formation (Figs. 2 and 4b, c). However, age-related dementia involves chronic gradual and irreversible memory decline and neurodegeneration. We therefore examined whether chronic excess formaldehyde treatment over a period of 30 days induces memory decline in rats. We injected normal adult SD rats intraperitoneally with 0.5 mM formaldehyde (60 mg/kg, i.p.) for 30 consecutive days. Results showed that excess formaldehyde suppressed hippocampal LTP in vivo. The amplitude of fEPSP in these groups (140%, Fig. 4d) was markedly lower than that (160%, Fig. 2h) of SD rats injected (i.c.v.) with excess formaldehyde. Significantly, there was a decline in learning and memory retrieval ability in the formaldehyde-treated group. Resveratrol, an exogenous formaldehyde scavenger (Szende et al. 1998), substantially rescued (P < 0.01) rat hippocampal LTP suppression caused by excess formaldehyde (Fig. 4d, e). That is to say, resveratrol markedly rescued (P < 0.01) excess formaldehyde-induced cognitive decline and decreased levels of hippocampal formaldehyde (Fig. 4f–i). This study demonstrates that chronic excess formaldehyde induces persistent memory loss.

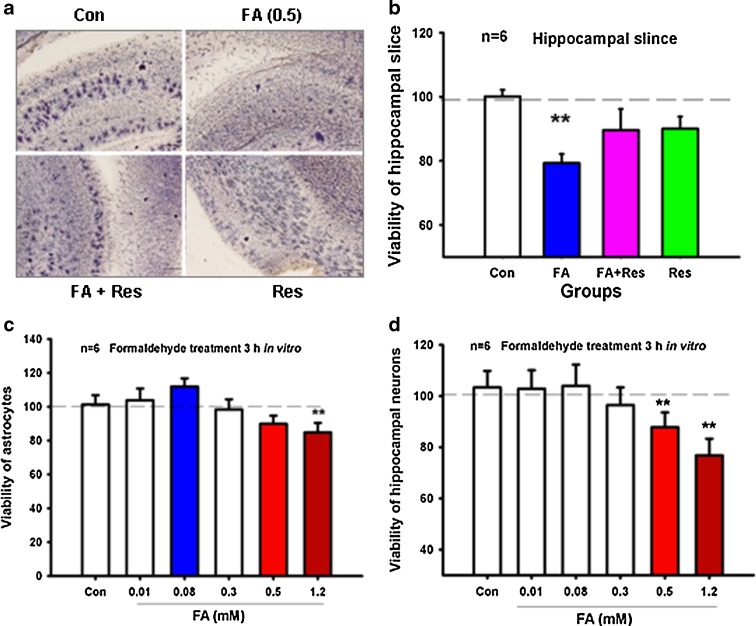

Chronic excess formaldehyde induces hippocampal neurotoxicity in formaldehyde-treated rats

Atrophy of the hippocampus is a typical pathological characteristic of Alzheimer’s disease and occurs from the early to the final stages of the disease. The hippocampus is not only a critical organ for short-term memory formation, but also a transfer station for LTM (Nakazawa et al. 2004). We therefore examined whether chronic excess formaldehyde treatment over a period of 30 days induces hippocampus impairment. Viability of hippocampal slices (300 μm) from rats injected with excess formaldehyde for 30 days was markedly lower than that of controls (P < 0.01). In addition, resveratrol, a formaldehyde scavenger, rescued formaldehyde-induced neurotoxicity of the hippocampus (Fig. 5a, b).

Fig. 5.

Chronic excess formaldehyde decreases the viability of the hippocampus. Hippocampal slices from SD rats treated with different reagents (control, formaldehyde, formaldehyde with resveratrol, and resveratrol) for 30 consecutive days were stained with MTT solution (a). Statistical analysis of the optical intensity of MTT staining (b). Viability of cultured hippocampal neurons treated with different concentrations of formaldehyde (0, 0.01, 0.08, 0.3, 0.5, and 1.2 mM) in vitro (c). Viability of cultured astrocytes treated with different concentrations of formaldehyde (0, 0.01, 0.08, 0.3, 0.5, and 1.2 mM) in vitro (d). *P < 0.5; **P < 0.01

To further confirm that the neurotoxicity was directly derived from excess formaldehyde (0.5 mM), hippocampal neurons and astrocytes were cultured in vitro. After treating with different concentrations of formaldehyde for 3 h, the viability of hippocampal neurons and astrocytes was decreased to a greater extent in the 0.5- and 1.2-mM formaldehyde treatment groups compared with the respective controls (P < 0.01) (Fig. 5c, d), indicating that excess formaldehyde directly leads to hippocampal impairment.

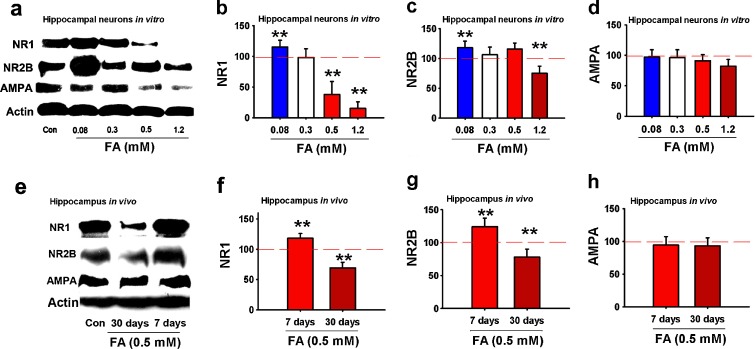

NR1/NR2B expression in hippocampal neurons relates with formaldehyde

Since the age-related decrease in the expression of NR2B is correlated with memory decline (Tang et al. 1999), if excess formaldehyde is a critical risk factor for memory loss in aging and AD patients, excess formaldehyde is speculated to decrease NR2B expression in the chronic formaldehyde treatment groups. To test this hypothesis, we detected NR1 and NR2B expression in vitro and in vivo by western blotting. NR1 expression of primary cultured hippocampal neurons increased in the presence of formaldehyde at 0.08 mM and decreased at 0.5 mM (P < 0.01) or higher concentration. NR2B expression markedly decreased at 1.2 mM formaldehyde (P < 0.01) (Fig. 6a–d). Furthermore, NR1 and NR2B expression increased in hippocampi of SD rats that had been treated with 0.5 mM formaldehyde for 7 days, but significantly decreased for 30 days (P < 0.01). Formaldehyde had little effect on AMPA receptor expression (Fig. 6e–h) under the experimental conditions. This indicates that changes in NR1 and NR2B expression are related with the level and duration of excess formaldehyde accumulated in the hippocampus of rats.

Fig. 6.

Formaldehyde regulates the expression of NMDA receptor subunits in vitro and in vivo. The effects of different concentrations of formaldehyde on the expression of NR1, NR2B, and AMPA receptors in primary cultured hippocampal neurons after formaldehyde treatment at different concentrations (0, 0.3, 0.5, and 1.2 mM) 3 h in vitro (a). Statistical analysis of the expression of NR1 (b), NR2B (c), and AMPA receptors (d). Expression of NR1, NR2B, and AMPA receptors in the hippocampi of rats injected with formaldehyde (0.5 mM) for 7 and 30 days (e). Statistical analysis of the expression of NR1 (f), NR2B (g), and AMPA receptors (h). N = 6; *P < 0.5; **P < 0.01

Discussion

In the present study, we provide evidence that excess hippocampal formaldehyde is an endogenous pathogenic factor in memory decline in age-related memory-deteriorating diseases. It is widely accepted that aging leads to memory loss in aged animals and humans, especially in Alzheimer’s disease (McGahon et al. 1999). Our study shows that endogenous formaldehyde is accumulated in aged animals and Alzheimer’s disease patients (Fig. 1). That formaldehyde is a small molecule (M.W. = 30) and able to permeate the blood–brain barrier (Grönvall et al. 1998; Shcherbakova et al. 1986) may explain why chronic excess formaldehyde induces wide neurotoxicity in the brain (Fig. 5). This neurotoxicity includes impairment of the hippocampus (Gurel et al. 2005), neurofilament protein changes (He et al. 2010), hyperphosphorylation of Tau protein (Lu et al. 2011), and demyelization of hippocampal neurons (Kilburn 1994; Kilburn et al. 1987; Perna et al. 2001). Physiological and/or pathological accumulation of formaldehyde is affected by a number of factors. (1) Aging: Recent research has shown that DNA demethylation leads to formaldehyde generation (Patra et al. 2008; Wu and Zhang 2010). A genome-wide decline in DNA methylation (DNA demethylation) occurs in the brain during normal aging, and aging accelerates memory decline (Liu et al. 2009). In this study, formaldehyde levels were markedly higher in aged mice and rats (Fig. 1c, d). These data hint that wide global DNA demethylation may be an endogenous factor for formaldehyde accumulation during the aging process or in Alzheimer’s disease. (2) Environmental pollutants: For example, environmental mercury contamination, which is believed as a pathogenic factor for Alzheimer’s disease (Ely 2001), induces formaldehyde accumulation in vivo (Retfalvi et al. 1998). (3) Diet: Formaldehyde participates in the “one-carbon cycle” (Kalász 2003). Deficiencies of vitamin B12 or folate in the diet lead to dysfunction of one-carbon metabolism in Alzheimer’s patients (Coppedè 2010). (4) Tumor: Cancer is known to be related to the occurrence of Alzheimer’s disease (Burke et al. 1994), and cancer cells and tumor tissues release higher levels of formaldehyde than normal cells and tissues (Tong et al. 2010). (5) Metabolic enzyme of formaldehyde: ADH3 and ALDH2, enzymes that catabolize formaldehyde (Teng et al. 2001), are related to memory. ADH3 is distributed in brains and contributes to defending the brain against neurodegenerative processes (Mori et al. 2000). However, ADH3 is a glutathione-dependent enzyme; levels of glutathione in brains decline during aging (Zhu et al. 2006). Therefore, decrease of ADH3 activity could lead to formaldehyde accumulation in brains with aging. ALDH2 polymorphism, which can result in the low activity of ALDH2 (Wang et al. 2008), is related to susceptibility to late-onset Alzheimer’s disease (Wang et al. 2002). Knockout of ALDH2 induces age-dependent neurodegeneration with accompanying memory loss (Ohsawa et al. 2008). (6) Genetic factor: Notably, amyloid 1–40 induces global DNA demethylation in vitro (Chen et al. 2009), and excess formaldehyde is observed in APP transgenic (hypomethylation of APP gene) mice when memory started to decline on month 6 (Tong et al. 2011). This hints that DNA demethylation of APP induces formaldehyde accumulation. Taken together, aging, diet, environmental pollution, enzyme dysfunction, and related genetic factors, all can induce endogenous formaldehyde accumulation.

As mentioned above, the concentrations of blood and urine formaldehyde changed in the aging process. The endogenous formaldehyde concentrations were statistically increased (P < 0.05) in people aged more than 70 years (Fig. 1a, b), and it should be noted that samples from people with dementia were not ruled out. Furthermore, we found that the level of hippocampal formaldehyde of AD patients was significantly increased. However, the hippocampal formaldehyde of humans without dementia at the age of 65–78 did not increase significantly (P > 0.05) compared to that of people at the age of 22–31 (Fig. 1e). According to an epidemiological investigation, the frequency of dementia doubles every 5 years, increasing from affecting 1% of individuals 60–64 years of age to 8% of those 75–79 years of age and to 35–45% of those >85 years of age (Cummings 2008). This suggests that endogenous formaldehyde increases with the aging process, similar to the frequency change in the onset of age-related dementia.

Furthermore, we have elucidated that molecular mechanisms of excess formaldehyde impair synaptic plasticity and spatial memory. NMDA receptor is a critical molecule for LTP and memory formation, and blocking the NMDA receptor induces memory loss (Tang et al. 1999). In our study, first, we demonstrated that excess formaldehyde suppresses hippocampal LTP and spatial memory formation in rats (Figs. 2 and 4), consistent with other reports of hippocampal LTP suppression and memory decline in aged mice and rats (Almaguer et al. 2002; Chapman et al. 1999; Kamal et al. 2005), STZ-induced diabetic SD rats (Reisi et al. 2010), and Alzheimer’s disease animal models such as APP transgenic mice (Gureviciene et al. 2004), APP/PS1 mice (Gengler et al. 2010), and SAMP8 (López-Ramos et al. 2012). Second, we showed that excess formaldehyde non-specifically blocks the NR1/NR2B subunits of the NMDA receptor in vitro (Fig. 3). An analogous study has shown that ethanol inhibits LTP formation by blocking the NMDA receptor, possibly because the cysteine residues of NR2B are sensitive to ethanol (Herin et al. 2001), and leads to amnesia (Brioni et al. 1989; Dildy and Leslie 1989; Tokuda et al. 2007; Wirkner et al. 1999). Some studies have shown that formaldehyde can spontaneously modify the cysteine residues of proteins (Metz et al. 2006; Toews et al. 2008). We therefore hypothesized that formaldehyde may modify the cysteine residues of NR1 or NR2B, although the specific residues involved need further investigation. Taken together, excess formaldehyde affects LTP and memory formation by non-specifically blocking NMDA receptor.

Another critical question is whether chronic excess formaldehyde treatment induces the decreased expression of NR1 and NR2B. It is known that NR1 and NR2B are both necessary for long-term memory formation (Nakazawa et al. 2004), since knockout of either NR1 or NR2B induces cognitive deficits in mice (Clayton et al. 2002; Rondi-Reig et al. 2006). In our study, NR2B expression initially increased then decreased in cultured hippocampal neurons after treatment with different concentrations of formaldehyde in vitro (Fig. 6a–d). Interestingly, the expression of NR1 and NR2B was increased in the hippocampus of the formaldehyde-treated groups after 7 days of formaldehyde treatment (Fig. 6e–h), consistent with a previous study indicating that acute formaldehyde treatment increases NR1 and NR2B expression (Gaunitz et al. 2002). We speculate that the increase in NR1/NR2B expression on day 7 compensates for the non-specific blocking of the NMDA receptor by excess formaldehyde. Some previous reports support this viewpoint. For example, chronic ethanol treatment, which induces amnesia (Brioni et al. 1989), up-regulates the expression of the NMDA receptor in vitro and in vivo (Henniger et al. 2003; Kalluri et al. 1998). Memory behavior is impaired in the Rett syndrome mice model even though hippocampal NR2B expression is increased (Asaka et al. 2006).

The expression of NR2B, a molecule that is critical for memory formation, declines with aging (Tang et al. 1999). Down-regulation of NR1 and NR2B expression has been found in the brains of APP transgenic mice (Dewachter et al. 2009), aged rats (Mesches et al. 2004), and AD patients (Amada et al. 2005; Hynd et al. 2004). As mentioned above, significant memory decline was associated with a decrease in NR1 and NR2B expression after 30 days of chronic excess formaldehyde treatment (Fig. 6e–h). Endogenous formaldehyde gradually accumulates in the brains of mice, rats, and humans during the process of aging and in AD patients (Fig. 1). Recent research has shown that long-term excess formaldehyde treatment induces up-regulation of DNA methyltransferases (DNMT1a) in 16HBE cells (Liu et al. 2011). DNMT binds with the promoter of NR2B, and up-regulation of DNMT leads to the silencing of NR2B (Lee et al. 2008). Our data along with these reports strongly suggest that chronic excess formaldehyde induces memory loss by decreasing NR1 and NR2B expression.

In conclusion, excess endogenous formaldehyde is a pathogenic factor in aged-dependent memory decline. Excess formaldehyde not only suppresses hippocampal LTP by blocking NMDA-receptor, but also persistently induces spatial memory deterioration by decreasing expression of the NMDA receptor. Furthermore, excess formaldehyde can induce amyloid or Tau protein aggregation, two of the markers of the late stages of Alzheimer’s disease (Chen et al. 2006; Nie et al. 2007a, b). The formaldehyde scavenger resveratrol (Tyihák et al. 1998) can directly decrease hippocampal formaldehyde levels (Tong et al. 2011) and the numbers of senile plaques in APP transgenic mice (Karuppagounder et al. 2009), although the activation of other pathways by resveratrol has not been ruled out (Sun et al. 2010). These data suggest that the scavenger of hippocampal formaldehyde is a potential and beneficial therapeutic target for age-related memory decline and neurodegeneration.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by grants from the Chinese Postdoctoral Fund 20090460047, the Natural Scientific Foundation of China NSFC (31171080, 30970695), the 973 Program (2010CB912303; 2012CB911004), the QCAS Biotechnology Fund (GJHZ1131), CAS-KSCX2-YW-R-119, KSCX2-YW-R-256, QCAS GJHZ1131, and the Johnson & Johnson Corporate Office of Science & Technology.

Footnotes

Zhiqian Tong, Chanshuai Han, Wenhong Luo, and Xiaohui Wang contributed equally to this work.

Contributor Information

Jinshun Qi, Email: jinshunqi2006@yahoo.com.

Rongqiao He, Email: herq@sun5.ibp.ac.cn.

References

- Abu-Abeeleh M, Bani Ismail ZA, Alzaben KR, Abu-Halaweh SA, Aloweidi AS, Al-Ammouri IA, Al-Essa MK, Jabaiti SK, Abu-Abeeleh J, Alsmady MM. A preliminary study of the use of human adipose tissue-derived stem cells for the treatment of streptozotocin-induced diabetes mellitus in a rat model. Comp Clin Pathol. 2010;19(1):1–4. doi: 10.1007/s00580-009-0912-x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Almaguer W, Estupiņán B, Uwe Frey J, Bergado JA. Aging impairs amygdala–hippocampus interactions involved in hippocampal LTP. Neurobiology of aging. 2002;23(2):319–324. doi: 10.1016/S0197-4580(01)00278-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amada N, Aihara K, Ravid R, Horie M. Reduction of NR1 and phosphorylated Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II levels in Alzheimer's disease. Neuroreport. 2005;16(16):1809. doi: 10.1097/01.wnr.0000185015.44563.5d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asaka Y, Jugloff DGM, Zhang L, Eubanks JH, Fitzsimonds RM. Hippocampal synaptic plasticity is impaired in the Mecp2-null mouse model of Rett syndrome. Neurobiol Dis. 2006;21(1):217–227. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2005.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blevins T, Mirshahi T, Chandler LJ, Woodward JJ. Effects of acute and chronic ethanol exposure on heteromeric N-methyl-d-aspartate receptors expressed in HEK 293 cells. J Neurochem. 1997;69(6):2345–2354. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1997.69062345.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brioni JD, McGaugh JL, Izquierdo I. Amnesia induced by short-term treatment with ethanol: attenuation by pretest oxotremorine. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 1989;33(1):27–29. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(89)90424-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burke WJ, McLaughlin JR, Chung HD, Gillespie KN, Grossberg GT, Luque FA, Zimmerman J. Occurrence of cancer in Alzheimer and elderly control patients: an epidemiologic necropsy study. Alzheimer Disease & Associated Disorders. 1994;8(1):22. doi: 10.1097/00002093-199408010-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chapman PF, White GL, Jones MW, Cooper-Blacketer D, Marshall VJ, Irizarry M, Younkin L, Good MA, Bliss T, Hyman BT. Impaired synaptic plasticity and learning in aged amyloid precursor protein transgenic mice. Nat Neurosci. 1999;2(3):271–276. doi: 10.1038/6374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen K, Maley J, Yu PH. Potential implications of endogenous aldehydes in β-amyloid misfolding, oligomerization and fibrillogenesis. J Neurochem. 2006;99(5):1413–1424. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2006.04181.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen KL, Wang SSS, Yang YY, Yuan RY, Chen RM, Hu CJ. The epigenetic effects of amyloid-[beta] 1–40 on global DNA and neprilysin genes in murine cerebral endothelial cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2009;378(1):57–61. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2008.10.173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng L, Yin WJ, Zhang JF, Qi JS. Amyloid beta-protein fragments 25–35 and 31–35 potentiate long-term depression in hippocampal CA1 region of rats in vivo. Synapse. 2009;63(3):206–214. doi: 10.1002/syn.20599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clayton DA, Mesches MH, Alvarez E, Bickford PC, Browning MD. A hippocampal NR2B deficit can mimic age-related changes in long-term potentiation and spatial learning in the Fischer 344 rat. J Neurosci. 2002;22(9):3628–3637. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-09-03628.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connelly CA, Chen LC, Colquhoun SD. Metabolic activity of cultured rat brainstem, hippocampal and spinal cord slices. Journal of neuroscience methods. 2000;99(1–2):1–7. doi: 10.1016/S0165-0270(00)00205-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coppedè F. One-carbon metabolism and Alzheimer's disease: focus on epigenetics. Current genomics. 2010;11(4):246–260. doi: 10.2174/138920210791233090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cui X. Inhaled formaldehyde on the effects of GSH level and distribution of formaldehyde. China J PrevMed. 1996;3:186. [Google Scholar]

- Cummings JL. The black book of Alzheimer's disease, part 1. Primary Psychiatry. 2008;15(2):66–76. [Google Scholar]

- Denk H, Moldeus PW, Schulz RA, Schenkman JB, Keyes SR, Cinti DL. Hepatic organelle interaction. IV. Mechanism of succinate enhancement of formaldehyde accumulation from endoplasmic reticulum N-dealkylations. The Journal of cell biology. 1976;69(3):589–598. doi: 10.1083/jcb.69.3.589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dewachter I, Filipkowski R, Priller C, Ris L, Neyton J, Croes S, Terwel D, Gysemans M, Devijver H, Borghgraef P. Deregulation of NMDA-receptor function and down-stream signaling in APP [V717I] transgenic mice. Neurobiology of aging. 2009;30(2):241–256. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2007.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dildy JE, Leslie SW. Ethanol inhibits NMDA-induced increases in free intracellular Ca2+ in dissociated brain cells. Brain research. 1989;499(2):383–387. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(89)90789-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drachman DA. Aging of the brain, entropy, and Alzheimer disease. Neurology. 2006;67(8):1340–1352. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000240127.89601.83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ely J. Mercury induced Alzheimer's disease: accelerating incidence? Bull Environ Contam Toxicol. 2001;67(6):800–806. doi: 10.1007/s001280193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaunitz C, Schüttler A, Gillen C, Allgaier C. Formalin-induced changes of NMDA receptor subunit expression in the spinal cord of the rat. Amino Acids. 2002;23(1):177–182. doi: 10.1007/s00726-001-0125-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gengler S, Hamilton A, Hölscher C. Synaptic plasticity in the hippocampus of a APP/PS1 mouse model of Alzheimer's disease is impaired in old but not young mice. PLoS One. 2010;5(3):e9764. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0009764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grönvall JLE, Garpenstrand H, Oreland L, Ekblom J. Autoradiographic imaging of formaldehyde adducts in mice: possible relevance for vascular damage in diabetes. Life Sci. 1998;63(9):759–768. doi: 10.1016/S0024-3205(98)00331-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gurel A, Coskun O, Armutcu F, Kanter M, Ozen OA. Vitamin E against oxidative damage caused by formaldehyde in frontal cortex and hippocampus: biochemical and histological studies. J Chem Neuroanat. 2005;29(3):173–178. doi: 10.1016/j.jchemneu.2005.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gureviciene I, Ikonen S, Gurevicius K, Sarkaki A, Van Groen T, Pussinen R, Ylinen A, Tanila H. Normal induction but accelerated decay of LTP in APP + PS1 transgenic mice. Neurobiol Dis. 2004;15(2):188–195. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2003.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He R, Lu J, Miao J. Formaldehyde stress. Science China Life Sciences. 2010;53(12):1399–1404. doi: 10.1007/s11427-010-4112-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heck HDA, White EL, Casanova-Schmitz M. Determination of formaldehyde in biological tissues by gas chromatography/mass spectrometry. Biological Mass Spectrometry. 1982;9(8):347–353. doi: 10.1002/bms.1200090808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henniger MSH, Wotjak CT, Hölter SM. Long-term voluntary ethanol drinking increases expression of NMDA receptor 2B subunits in rat frontal cortex. Eur J Pharmacol. 2003;470(1–2):33–36. doi: 10.1016/S0014-2999(03)01787-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herin GA, Du S, Aizenman E. The neuroprotective agent ebselen modifies NMDA receptor function via the redox modulatory site. J Neurochem. 2001;78(6):1307–1314. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2001.00517.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hynd MR, Scott HL, Dodd PR. Differential expression of N-methyl-d-aspartate receptor NR2 isoforms in Alzheimer's disease. J Neurochem. 2004;90(4):913–919. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2004.02548.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalapos MP. A possible evolutionary role of formaldehyde. Experimental & molecular medicine. 1999;31(1):1–4. doi: 10.1038/emm.1999.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalász H. Biological role of formaldehyde, and cycles related to methylation, demethylation, and formaldehyde production. Mini reviews in medicinal chemistry. 2003;3(3):175–192. doi: 10.2174/1389557033488187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalluri HSG, Mehta AK, Ticku MK. Up-regulation of NMDA receptor subunits in rat brain following chronic ethanol treatment. Molecular brain research. 1998;58(1–2):221–224. doi: 10.1016/S0169-328X(98)00112-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamal A, Biessels GJ, Ramakers GMJ, Hendrik Gispen W. The effect of short duration streptozotocin-induced diabetes mellitus on the late phase and threshold of long-term potentiation induction in the rat. Brain research. 2005;1053(1–2):126–130. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2005.06.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karuppagounder SS, Pinto JT, Xu H, Chen HL, Beal MF, Gibson GE. Dietary supplementation with resveratrol reduces plaque pathology in a transgenic model of Alzheimer's disease. Neurochem Int. 2009;54(2):111–118. doi: 10.1016/j.neuint.2008.10.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kilburn KH. Neurobehavioral impairment and seizures from formaldehyde. Archives of Environmental Health: An International Journal. 1994;49(1):37–44. doi: 10.1080/00039896.1994.9934412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kilburn KH, Warshaw R, Thornton JC. Formaldehyde impairs memory, equilibrium, and dexterity in histology technicians: effects which persist for days after exposure. Archives of Environmental Health: An International Journal. 1987;42(2):117–120. doi: 10.1080/00039896.1987.9935806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kollau A, Hofer A, Russwurm M, Koesling D, Keung WM, Schmidt K, Brunner F, Mayer B. Contribution of aldehyde dehydrogenase to mitochondrial bioactivation of nitroglycerin: evidence for the activation of purified soluble guanylate cyclase through direct formation of nitric oxide. Biochem J. 2005;385(Pt 3):769. doi: 10.1042/BJ20041354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee S, Kim W, Ham BJ, Chen W, Bear MF, Yoon BJ. Activity-dependent NR2B expression is mediated by MeCP2-dependent epigenetic regulation. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2008;377(3):930–934. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2008.10.082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu L, van Groen T, Kadish I, Tollefsbol TO. DNA methylation impacts on learning and memory in aging. Neurobiology of aging. 2009;30(4):549–560. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2007.07.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Q, Yang L, Gong C, Tao G, Huang H, Liu J, Zhang H, Wu D, Xia B, Hu G. Effects of long-term low-dose formaldehyde exposure on global genomic hypomethylation in 16HBE cells. Toxicol Lett. 2011;205(3):235–240. doi: 10.1016/j.toxlet.2011.05.1039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- López-Ramos JC, Jurado-Parras MT, Sanfeliu C, Acuña-Castroviejo D, Delgado-García JM. Learning capabilities and CA1-prefrontal synaptic plasticity in a mice model of accelerated senescence. Neurobiology of aging. 2012;33(3):627. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2011.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu J, Miao J, Pan R, He R. Formaldehyde-mediated hyperphosphorylation disturbs the interaction between Tau protein and DNA. Progress in Biochemistry and Biophysics. 2011;38(12):1113–1120. doi: 10.3724/SP.J.1206.2011.00451. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Luo W, Li H, Zhang Y, Ang CYW. Determination of formaldehyde in blood plasma by high-performance liquid chromatography with fluorescence detection. J Chromatogr B: Biomed Sci Appl. 2001;753(2):253–257. doi: 10.1016/S0378-4347(00)00552-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malek FA, Möritz KU, Fanghänel J. A study on the effect of inhalative formaldehyde exposure on water labyrinth test performance in rats. Annals of Anatomy-Anatomischer Anzeiger. 2003;185(3):277–285. doi: 10.1016/S0940-9602(03)80040-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGahon BM, Martin DSD, Horrobin DF, Lynch MA. Age-related changes in LTP and antioxidant defenses are reversed by an [alpha]-lipoic acid-enriched diet. Neurobiology of aging. 1999;20(6):655–664. doi: 10.1016/S0197-4580(99)00050-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKenna JE, Melzack R. Blocking NMDA receptors in the hippocampal dentate gyrus with AP5 produces analgesia in the formalin pain test. Exp Neurol. 2001;172(1):92–99. doi: 10.1006/exnr.2001.7777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mesches MH, Gemma C, Veng LM, Allgeier C, Young DA, Browning MD, Bickford PC. Sulindac improves memory and increases NMDA receptor subunits in aged Fischer 344 rats. Neurobiology of aging. 2004;25(3):315–324. doi: 10.1016/S0197-4580(03)00116-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Metz B, Kersten GFA, Baart GJE, de Jong A, Meiring H, ten Hove J, van Steenbergen MJ, Hennink WE, Crommelin DJA, Jiskoot W. Identification of formaldehyde-induced modifications in proteins: reactions with insulin. Bioconjugate chemistry. 2006;17(3):815–822. doi: 10.1021/bc050340f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mori O, Haseba T, Kameyama K, Shimizu H, Kudoh M, Ohaki Y, Arai Y, Yamazaki M, Asano G. Histological distribution of class III alcohol dehydrogenase in human brain. Brain research. 2000;852(1):186–190. doi: 10.1016/S0006-8993(99)02201-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris R. Developments of a water-maze procedure for studying spatial learning in the rat. Journal of neuroscience methods. 1984;11(1):47–60. doi: 10.1016/0165-0270(84)90007-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakazawa K, McHugh TJ, Wilson MA, Tonegawa S. NMDA receptors, place cells and hippocampal spatial memory. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2004;5(5):361–372. doi: 10.1038/nrn1385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nie C, Wang X, Liu Y, Perrett S, He R. Amyloid-like aggregates of neuronal tau induced by formaldehyde promote apoptosis of neuronal cells. BMC Neurosci. 2007;8(1):9. doi: 10.1186/1471-2202-8-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nie C, Wei Y, Chen X, Liu Y, Dui W, Liu Y, Davies MC, Tendler SJB, He R. Formaldehyde at low concentration induces protein tau into globular amyloid-like aggregates in vitro and in vivo. PLoS One. 2007;2(7):e629. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0000629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohsawa I, Nishimaki K, Murakami Y, Suzuki Y, Ishikawa M, Ohta S. Age-dependent neurodegeneration accompanying memory loss in transgenic mice defective in mitochondrial aldehyde dehydrogenase 2 activity. J Neurosci. 2008;28(24):6239–6249. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4956-07.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patra SK, Patra A, Rizzi F, Ghosh TC, Bettuzzi S. Demethylation of (Cytosine-5-C-methyl) DNA and regulation of transcription in the epigenetic pathways of cancer development. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2008;27(2):315–334. doi: 10.1007/s10555-008-9118-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perna RB, Bordini EJ, Deinzer-Lifrak M. A case of claimed persistent neuropsychological sequelae of chronic formaldehyde exposure: clinical, psychometric, and functional findings. Arch Clin Neuropsychol. 2001;16(1):33–44. doi: 10.1093/arclin/16.1.33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reisi P, Alaei H, Babri S, Sharifi MR, Mohaddes G. Effects of treadmill running on spatial learning and memory in streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats. Neurosci Lett. 2009;455(2):79–83. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2009.03.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reisi P, Babri S, Alaei H, Sharifi MR, Mohaddes G, Noorbakhsh SM, Lashgari R. Treadmill running improves long-term potentiation (LTP) defects in streptozotocin-induced diabetes at dentate gyrus in rats. Pathophysiology. 2010;17(1):33–38. doi: 10.1016/j.pathophys.2009.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Retfalvi T, Nemeth Z, Sarudi I, Albert L. Alteration of endogenous formaldehyde level following mercury accumulation in different pig tissues. Acta biologica Hungarica. 1998;49(2–4):375. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rondi-Reig L, Petit GH, Tobin C, Tonegawa S, Mariani J, Berthoz A. Impaired Sequential egocentric and allocentric memories in forebrain-specific-NMDA receptor knock-out mice during a new task dissociating strategies of navigation. J Neurosci. 2006;26(15):4071–4081. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3408-05.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shcherbakova L, Tel'Pukhov V, Trenin S, Bashilov I, Lapkina T. Permeability of the blood–brain barrier to intra-arterial formaldehyde. Biull Eksp Biol Med. 1986;102(11):573–575. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song MS, Baker GB, Dursun SM, Todd KG. The antidepressant phenelzine protects neurons and astrocytes against formaldehyde-induced toxicity. J Neurochem. 2010;114(5):1405–1413. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2010.06857.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun AY, Wang Q, Simonyi A, Sun GY. Resveratrol as a therapeutic agent for neurodegenerative diseases. Mol Neurobiol. 2010;41(2):375–383. doi: 10.1007/s12035-010-8111-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szende B, Tyihák E, Trézl L, Szöke E, László I, Kátay G, Király-Véghely Z. Formaldehyde generators and capturers as influencing factors of mitotic and apoptotic processes. Acta biologica Hungarica. 1998;49(2–4):323. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang YP, Shimizu E, Dube GR, Rampon C, Kerchner GA, Zhuo M, Liu G, Tsien JZ. Genetic enhancement of learning and memory in mice. Nature. 1999;401(6748):63–69. doi: 10.1038/43432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teng S, Beard K, Pourahmad J, Moridani M, Easson E, Poon R, O'Brien PJ. The formaldehyde metabolic detoxification enzyme systems and molecular cytotoxic mechanism in isolated rat hepatocytes. Chemico-Biological Interactions. 2001;130:285–296. doi: 10.1016/S0009-2797(00)00272-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toews J, Rogalski JC, Clark TJ, Kast J. Mass spectrometric identification of formaldehyde-induced peptide modifications under in vivo protein cross-linking conditions. Anal Chim Acta. 2008;618(2):168–183. doi: 10.1016/j.aca.2008.04.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tokuda K, Zorumski CF, Izumi Y. Modulation of hippocampal long-term potentiation by slow increases in ethanol concentration. Neuroscience. 2007;146(1):340–349. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2007.01.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tong Z, Luo W, Wang Y, Yang F, Han Y, Li H, Luo H, Duan B, Xu T, Maoying Q. Tumor tissue-derived formaldehyde and acidic microenvironment synergistically induce bone cancer pain. PLoS One. 2010;5(4):e10234. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0010234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tong Z, Zhang J, Luo W, Wang W, Li F, Li H, Luo H, Lu J, Zhou J, Wan Y, He R. Urine formaldehyde level is inversely correlated to mini mental state examination scores in senile dementia. Neurobiology of aging. 2011;32(1):31–41. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2009.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trézl L, Csiba A, Juhasz S, Szentgyörgyi M, Lombai G, Hullán L, Juhász A. Endogenous formaldehyde level of foods and its biological significance. Zeitschrift für Lebensmitteluntersuchung und -Forschung A. 1997;205(4):300–304. doi: 10.1007/s002170050169. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tyihák E, Albert L, Németh ZI, Kátay G, Király-Véghely Z, Szende B. Formaldehyde cycle and the natural formaldehyde generators and capturers. Acta biologica Hungarica. 1998;49(2–4):225–238. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang RS, Nakajima T, Kawamoto T, Honma T. Effects of aldehyde dehydrogenase-2 genetic polymorphisms on metabolism of structurally different aldehydes in human liver. Drug metabolism and disposition. 2002;30(1):69–73. doi: 10.1124/dmd.30.1.69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang B, Wang J, Zhou S, Tan S, He X, Yang Z, Xie YC, Li S, Zheng C, Ma X. The association of mitochondrial aldehyde dehydrogenase gene (ALDH2) polymorphism with susceptibility to late-onset Alzheimer's disease in Chinese. J Neurol Sci. 2008;268(1–2):172–175. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2007.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wirkner K, Poelchen W, Köles L, Mühlberg K, Scheibler P, Allgaier C, Illes P. Ethanol-induced inhibition of NMDA receptor channels. Neurochem Int. 1999;35(2):153–162. doi: 10.1016/S0197-0186(99)00057-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu SC, Zhang Y. Active DNA demethylation: many roads lead to Rome. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2010;11(9):607–620. doi: 10.1038/nrm2950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang JF, Qi JS, Qiao JT. Protein kinase C mediates amyloid [beta]-protein fragment 31-35-induced suppression of hippocampal late-phase long-term potentiation in vivo. Neurobiol Learn Mem. 2009;91(3):226–234. doi: 10.1016/j.nlm.2008.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu Y, Carvey PM, Ling Z. Age-related changes in glutathione and glutathione-related enzymes in rat brain. Brain research. 2006;1090(1):35–44. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2006.03.063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]