Abstract

Hepatitis B virus (HBV) causes a chronic infection in 350 million people worldwide and greatly increases the risk of liver cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma. The majority of chronic HBV carriers live in Asia. HBV can be divided into eight genotypes with unique geographic distributions. Mutations accumulate during chronic infection or in response to external pressure. Because HBV is an RNA-DNA virus the emergence of drug resistance and vaccine escape mutants has become an important clinical and public health concern. Here, we provide an overview of the molecular biology of the HBV life cycle and an evaluation of the changing role of hepatitis B e antigen (HBeAg) at different stages of infection. The impact of viral genotypes and mutations/deletions in the precore, core promoter, preS, and S gene on the establishment of chronic infection, development of fulminant hepatitis and liver cancer is discussed. Because HBV is prone to mutations, the biological properties of drug-resistant and vaccine escape mutants are also explored.

Keywords: hepatitis B virus, persistent infection, genotype, mutant

A BRIEF INTRODUCTION TO THE MOLECULAR BIOLOGY OF HBV

Genome, genes, and proteins

The hepatitis B virus (HBV), an enveloped DNA virus of the hepatotropic DNA virus family (hepadnaviridae), has the smallest (3.2 kb) genome among DNA viruses.1 Related viruses have been found in woodchucks, ground squirrels, and ducks, suggesting a long evolutionary history of this virus family. The partially double-stranded HBV genome is encased within the core particle, which is wrapped by an envelope consisting of host-derived lipids containing dispersed viral envelope proteins. HBV enters hepatocytes via an as yet unknown receptor. Following uncoating and disassembly of the core particle, the viral DNA is delivered to the nucleus and converted into covalently closed circular (ccc) DNA (Figure 1). In the nucleus the cccDNA serves as a template for viral RNA transcription. Four genes are arranged on the 3.2 kb circular genome in the following order: core, polymerase (P), envelope, and X. The P gene overlaps with the 3' end of the core gene, the entire envelope gene, and the 5' end of the X gene (Figure 2). The envelope and core genes have alternative in-frame translation initiation sites resulting in 7 proteins being expressed from the 4 genes. Initiation from the ATG codons of preS1, preS2, and S in the envelope gene generates the large (L), middle (M), and small (S) envelope proteins, respectively, with the L protein having an extra preS1 domain compared to the M protein and M having an extra preS2 domain compared to the S protein (Figure 2 and Table 1). Similarly, translation from the ATG codons in the precore region and core gene generates the precore and core proteins, with the former being the precursor to the hepatitis B e antigen (HBeAg). Thus overlapping genes and alternative translation initiation sites partially overcome the constraints of a small genome.

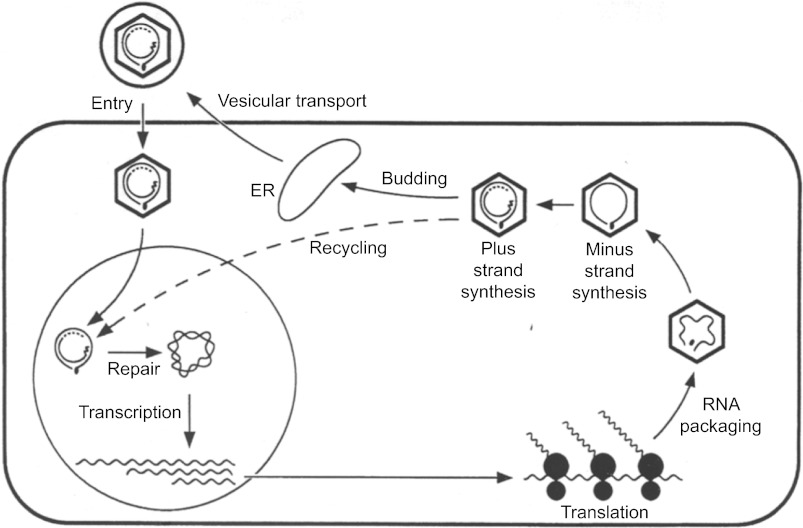

Figure 1.

An overview of the HBV lifecycle. The enveloped DNA virus enters hepatocytes via an as yet unknown receptor, followed by disassembly of nucleocapsid. The partially double-stranded DNA genome is delivered to the nucleus and converted to cccDNA, which serves as the template for viral mRNA transcription. The mRNAs are transported to the cytoplasm for protein synthesis. The pgRNA is packaged together with the P protein into the nucleocapsid assembled from the core protein, followed by sequential synthesis of minus- and plus-strand DNA. The nucleocapsids are then enveloped and secreted as virions.

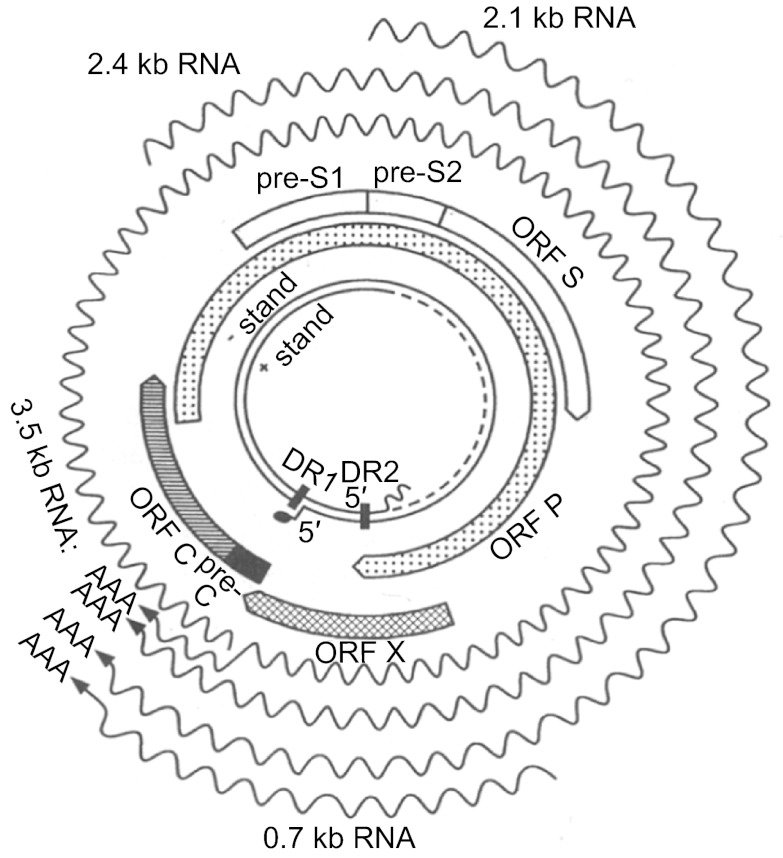

Figure 2.

HBV genome, genes, and transcripts. The inner circles show the partially double-stranded DNA of 3.2 kb. Next are the 4 open reading frames (ORFs): P, preS1/preS2/S, X, and preC/C. Please note that the P ORF overlaps with the other 3. The wavy lines indicate transcripts of 0.7 kb-3.5 kb, which have different start sites (5' end) but the same 3' end.

Table 1. Alternative translation initiation generates multiple products from core and envelope genes.

| Initiating AUG | Precore | Core | preS1 | preS2 | S |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intermediate | Precore/core | NA* | NA | NA | NA |

| Final product | HBeAg | Core | L (preS1/preS2/S) | M (preS2/S) | S (S) |

*NA: not applicable.

Transcriptional regulation and mechanisms of protein expression

Eukaryotic gene expression is often controlled by the ribosomal scanning mechanism. The 40s ribosomes bind to the 5' cap structure and scan down the mRNA to find the Kozak sequence-flanked AUG codon closest to the 5' terminus leading to the assembly of the 80s ribosomes for protein translation. The ribosomes disengage from the mRNA after translation. Thus, a single protein encoded by the most favourable ORF starting from the 5' end is translated from most mRNAs. HBV uses 4 promoters coupled with imprecise transcription initiation sites to generate 6 of its 7 proteins. These are the X promoter for the 0.7 kb RNA encoding Hepatitis B virus X (HBx), the L promoter for the 2.4 kb RNA encoding the L protein, the S promoter for the 2.1 kb RNA giving rise to the M and S proteins, and the core promoter for the 3.5 kb RNA for the precore/core and core proteins (Table 2). P protein expression is controlled at the translational level via leaky ribosomal scanning.

Table 2. HBV promoters, transcripts, and proteins.

| Promoter | Transcript | Protein(s) |

|---|---|---|

| Core | 3.5 kb | Longer (pc): HBeAg; shorter (pg): core + P |

| L | 2.4 kb | L |

| M/S | 2.1 kb | Longer: M; shorter: S |

| X | 0.7 kb | HBx |

Because its 5' end is located either upstream or downstream of the preS2 AUG codon, the 2.1 kb RNA expresses the M protein in addition to the S protein. Similarly, the core promoter generates 2 subsets of the 3.5 kb RNA, with the longer one (precore RNA) encoding the precore/core protein and the shorter one encoding the core protein (Table 2). The shorter one is referred to as pregenomic (pg) RNA because of its additional role as the precursor of viral DNA. The P protein, which does not have its own RNA, is translated from pgRNA through a combination of leaky ribosomal scanning and translational termination – reinitiation mechanisms. This makes the pgRNA the only bicistronic mRNA in HBV.

All of the HBV RNAs are transcribed by the host DNA-dependent RNA polymerase (pol II) from the same strand of cccDNA and consequently contain both the 5' cap and 3' polyA tail. They are co-terminal at the 3' end because they all use the same polyadenylation signal located at the 5' end of the core gene. Therefore the 0.7 kb X transcript is entirely overlapped by the longer (2.1 kb, 2.4 kb, and 3.5 kb) transcripts (Figure 2). The X, S, L, and core promoters overlap with the P gene, preS1 region of the envelope gene, the P gene, and the X gene, respectively. The overlap between cis-acting elements and coding sequences further expands the capacity of a small genome. How such a highly sophisticated genome has evolved from a more primitive version is still unknown. The compactness of the hepadnavirus genomes may make some mutants less fit than the wild-type virus. This compactness also complicates functional characterization of naturally occurring mutations in the HBV genome because a mutation often simultaneously alters several functional elements and thus may have a pleiotropic effect.

Protein expression and genome replication

The HBV transcripts described above are transported to the cytoplasm for protein translation and genome replication. HBV genome replication requires 3 components: the core protein, P protein, and pgRNA. The core protein is capable of self-assembly, but co-packaging of the P protein and pgRNA is a prerequisite for genome replication. Selective packaging of the pgRNA, which consists of the complement of the complete genomic DNA rather than the 2.4 kb, 2.1 kb, or 0.7 kb subgenomic RNAs, is mediated by a hairpin structure at its 5' end called the pregenome encapsidation (ε) signal (Figure 3).2 Inside the core particle the P protein converts the pgRNA into double-stranded DNA via a series of enzymatic reactions. The pgRNA serves as both the pregenome and the mRNA for the translation of core and P proteins and is the only transcript required for genome replication. Consequently, HBV replication capacity can be easily modulated by sequence changes in the core promoter that alter pgRNA levels.

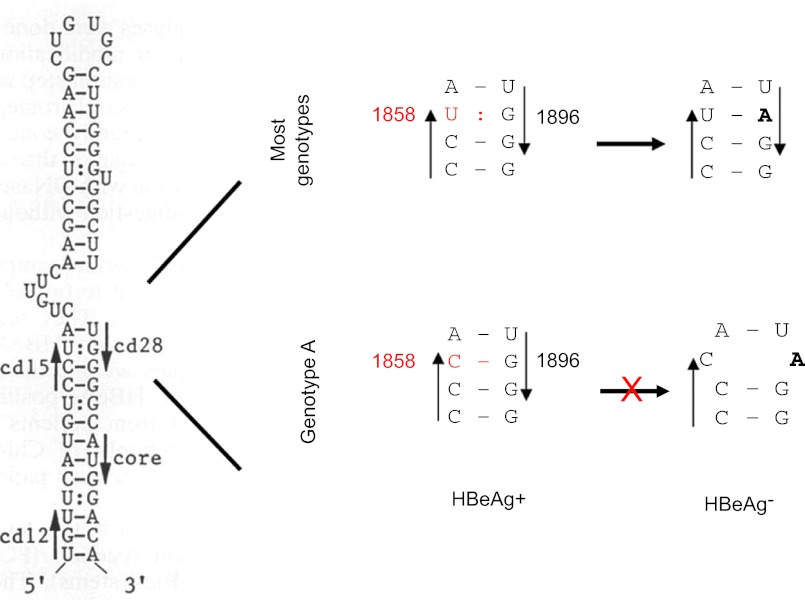

Figure 3.

The base-pairing requirement of the ε signal restricts the emergence of G1896A mutation from genotype A. The secondary structure of the ε signal is shown on the left, with the precore codons 15 and 28, and the initiation codon of the core gene indicated by arrowheads. The right panel is an enlarged figure showing the base pairing between codons 15 and 28. Notably, the G1896A mutation improves base pairing for most genotypes but disrupts base pairing for genotype A.

Secretion of virions and subviral particles

Plus-strand DNA synthesis triggers the interaction of the core particle with envelope proteins anchored on the endoplasmic reticulum, leading to vesicle formation and release of the 42 nm virions. In addition to virions, HBV also secretes 22 nm lipid particles called subviral particles, which consist of S and M proteins and exceed virions by 1000 – 100 000 fold in number. They are detected serologically as hepatitis B surface antigen, or hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg). The S protein constitutes the bulk of the envelope proteins on virions and subviral particles. The expression of the S protein alone can lead to the secretion of subviral particles, suggesting that the S protein is the morphogenic factor in particle formation. The L protein, present primarily on virions, inhibits subviral particle secretion in a dose-dependent manner. By simultaneously interacting with the S and core proteins, the L protein directs a fraction of the S protein towards virion formation. We found that a drastic reduction in the expression of all 3 envelope proteins or the S protein alone results in significantly reduced secretion of subviral particles but not virions.3 Therefore, HBV produces more envelope proteins, especially the S protein, than is needed for virion secretion. The overproduction of subviral particles most likely helps to overwhelm the immune system, facilitating persistent infection. Interestingly, although the M protein is thought to be dispensable for virion secretion,4,5 preventing M protein expression reduces virion secretion but increases virion genome maturity, or the extent of plus-strand DNA synthesis.3 Thus, the M protein enables core particle envelopment at an early time point during plus-strand DNA synthesis. The S domain of all 3 envelope proteins are modified by N-linked glycosylation, which is essential for the secretion of virions but not subviral particles.6

SELECTION FOR AND AGAINST HBeAg EXPRESSION AT DIFFERENT STAGES OF INFECTION

HBeAg biosynthesis

HBeAg is derived from the precore/core protein (p25) by 2 proteolytic cleavage events. Of the 29 residues encoded by the precore region, the N-terminal 19 residues target the precore/core protein to the endoplasmic reticulum, where they are removed by the signal peptidase.7 The truncated protein (p22) enters the constitutive secretory pathway, where its highly basic C-terminal 29 residues are cleaved off by furin or a similar dibasic endopeptidase.6,8 This cleavage converts p22 into mature HBeAg (p17), which has a slightly longer N-terminus than the core protein but has a shortened C-terminus. HBeAg is no longer able to form particles but rather circulates as a soluble protein. HBV isolates worldwide can be grouped into at least 8 genotypes (A-H) based on >8% sequence divergence of the entire genome.9,10,11,12 Only genotype A secretes HBeAg of several sizes because a unique 2 amino acid insertion at the C-terminal cleavage site diminishes its usage in promotion of cleavage at downstream sites.6

Role of HBeAg expression on HBV survival is dependent on the stage of infection

The ability to express the e antigen is conserved among all hepadnaviruses. It was thus surprising that nonsense or frameshift mutations introduced into the precore region to abolish e antigen expression had no detectable effect on duck hepatitis B virus (DHBV) replication or infectivity in vivo.13,14 However, these findings set the stage for the subsequent discovery of similar mutations in the precore region of HBV that prevent HBeAg expression.15,16,17,18,19 These include nonsense or frameshift mutations inside the precore region, as well as point mutations in the precore AUG codon. Importantly, it was soon realized that patients carrying these mutated viruses were initially infected with the wild-type virus and that precore mutation arose de novo at a late stage of chronic HBV infection, when the host had developed anti-HBe antibodies. Subsequent studies on the woodchuck hepatitis virus (WHV) demonstrated that a mutant unable to produce the e antigen has reduced capacity to establish persistent infection in neonatal woodchucks.20,21 Because of 2 nonsense mutations in the precore region, 1 specific HBV genotype (G) is always incapable of HBeAg expression. However, genotype G-infected patients are HBeAg positive at the early stage of infection because of coinfection with another HBV genotype.22 Genotype G gradually outgrows the other genotype as the patients seroconvert from being HBeAg-positive to anti-HBe. Thus, although virus survival during the anti-HBe stage does not require HBeAg expression, the establishment of de novo chronic infection does.

Why is HBeAg required for the establishment of chronic infection? As mentioned above, HBeAg can be considered as a secreted variant of the core protein, which is a strong immunogen and the major target of host immune clearance mechanisms. Studies in mice have suggested that the core protein induces type I T helper functions conducive to recovery, whereas HBeAg induces type II T helper functions contributing to viral persistence.23 Moreover, HBeAg can induce immune tolerance or switch the immune response against the core protein from type I to type II.24,25,26

The ε signal constrains the precore mutation abolishing HBeAg expression

The most common precore mutation abolishing HBeAg expression is G1896A, which converts the penultimate (28th) precore codon from TGG to TAG. Two-thirds of the precore region toward its 3' end constitutes part of the ε signal for pgRNA packaging, with a large portion of it being base-paired (Figure 3). The base-pairing requirement explains the limited type of nonsense mutations used by HBV to abolish HBeAg expression and the predominance of the G1896A mutation.27 As shown in Figure 3, the wobble G:U pairing between G1896 and U1858 in pgRNA is rendered more stable by the G1896A mutation as a result of the A:U pair formation. Because of the polymorphism at position 1858, the prevalence of the G1896A mutation was found to be genotype-dependent (Table 3). Therefore, genotype A with C1858 rarely circulates as an HBeAg-negative mutant because 1896A would disrupt the preexisting C:G pair and impair HBV genome replication.28,29 When the G1896A mutation develops, a compensatory C1858T mutation has to occur to maintain base pairing. Research from Lok and others suggests that most isolates of genotype C1, as found in Hong Kong, Southern China, and Southeast Asia, also harbor C1858 and are refractory to the G1896A mutation.30,31,32,33,34 Similarly, genotype F can be subdivided into those having C1858 or T1858, which determines the prevalence of G1896A mutation (Table 3).11,35,36

Table 3. Impact of sequence polymorphism at position 1858 on the emergence of G1896A mutation.

| Genotype | 1858 | 1896 tolerant phase | 1896 clearance phase |

|---|---|---|---|

| A, C1, F2, F3 | C | G | G |

| B, D, E, F, H | T | G | A |

| G | T | A* | A |

*Requires coinfection by an HBeAg-expressing genotype.

Core promoter mutations as a mechanism for simultaneously diminishing HBeAg expression and enhancing genome replication

By careful analysis of HBV sequences from patients at the anti-HBe stage of infection, Okamoto and colleagues discovered the core promoter mutant.37 The most common mutations in the core promoter are A1762T and G1764A occurring in tandem. Transfection experiments showed that the double mutation reduced precore RNA transcription and hence HBeAg expression. In addition, it moderately increased genome replication through up regulation of pgRNA levels.38,39,40 In addition to A1762T/G1764A, mutations can be detected at nearby positions such as 1753, 1757, 1766, and 1768. Site-directed mutagenesis experiments have suggested that the additional mutations at 1753, 1766, and 1788 further reduce HBeAg expression and enhance genome replication, with the A1762T/G1764A/C1766T triple mutant having greater than 10 fold higher replication capacity than the wild-type virus.41 The extent of changes in HBeAg expression and genome replication correlated with a reduction in precore RNA and an increase in pgRNA levels. Thus, core promoter mutations may cumulatively upregulate genome replication and downregulate HBeAg expression. The earlier emergence of 1762/1764 double-mutant compared to the less-common ones42 suggests a gradual increase of genome replication and reduction of HBeAg expression as the host immune clearance intensifies.

The reduced HBeAg expression and enhanced genome replication are not only the functional consequences of core promoter mutations, but they are also their likely driving forces. The emergence of core promoter mutations during the immune clearance phase of infection, as indicated by elevations in Alanine transaminase (ALT) levels, is consistent with a physiological significance of reducing HBeAg expression. If this is true, then HBV genotypes that are unable to develop the G1896A precore mutation should develop core promoter mutations more frequently. Consistent with this hypothesis, the A1762T/G1764A double-mutation was more prevalent in genotype C1 (with C1858) than C2 (with T1858).31,32,33 Genotype A also had a higher prevalence of core promoter mutations than genotype D.43,44 Moreover, because core promoter mutations enhance HBV genome replication, their acquisition may promote the survival of HBV isolates with low intrinsic replication capacity. It is well established that core promoter mutations in HBV develop more frequently in genotype C than genotype B isolates.32,45,46,47 Consistent with this observation, we found that the replication capacity of most genotype C2 isolates was lower than that of genotype B2 isolates.48

ENVIRONMENTAL AND VIRAL FACTORS FOR PREDISPOSITION TO CHRONIC HBV INFECTION

HBV infection can be divided into acute and chronic phases. Severe clinical outcomes, such as liver cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma, stem from chronic infection. Therefore, it is important to identify viral and environmental factors that predispose patients to chronic HBV infection.

Mode of transmission

HBV genotypes B and C prevail in the Far East (such as China, Japan, and Korea) with a south-to-north gradient. Genotype D is dominant in the Mediterranean region and along path of the Silk Road.49 Genotype A is widely distributed in Europe, North America, parts of Africa and Asia. Chronic HBV infection is common in Asia and Africa but is rare in Western countries. These trends are primarily due to the different modes of transmission prevalent in these countries. In Western countries, infection by genotypes A and D is often transmitted during adulthood by sex, sharing of injection needles, or blood transfusion. Such transmissions lead to clinical symptoms of acute hepatitis followed by the resolution of infection in most individuals. Less than 10% of such acute infections progress to the chronic stage. In the Far East, the most common route of HBV infection is via perinatal transmission of genotypes B and C from HBeAg+ mothers during birth. Over 90% of such perinatal transmission cases develop initially asymptomatic but chronic infection lasting for several decades. A study from Japan suggests that genotype C is more likely to cause perinatal transmission than genotype B.50 In Africa, infection is acquired during early childhood, and the chronicity rate ranges from 82% in infants less than 6 months old to 15% in children between 2 and 3 years of age.51 Most of these carriers are able to clear the infection around 20 years of age. Therefore, the age of transmission inversely correlates with the duration of infection, which is most likely because the immature host immune system in children is less capable of clearing infection. Moreover, it is likely that HBeAg can induce immune tolerance much more easily in infants than in adults.

Viral dose

Persistent WHV and DHBV infection can be established in young animals but not older ones, thus confirming the critical role of age on infection outcome. However, the resistance of older animals to persistent infection can be partially overcome with a large viral dose.21,52 The dose of exposure is expected to be high during blood transfusion but low during other modes of transmission, such as sexual contact, mosquito bite, and injury sustained at the time of shaving at a barber's shop. Virus transmission experiments in chimpanzees performed at the National Institutes of Health, USA suggest that as little as 3 copies of genotype C genomes can cause infection in 50% of chimpanzees (CID50) in contrast to 78 and 169 genomes for genotypes D and A, respectively.53 This suggests that it is possible to transmit HBV genotype C even with a very small viral dose, such as the amount of virus contained in a mosquito bite. Another study put the CID50 at 16-28 copies for genotype A and 35-46 for genotype C.54 A third study, based exclusively on genotype D, found that an infection rate of 100% of the hepatocytes and viral persistence could be achieved by either 1 genome or 1010 genomes. Surprisingly, exposure to intermediate doses (107 and 104 genomes) caused infection in only 0.1% of the hepatocytes followed by effective viral clearance.55 Therefore, it remains unclear whether the higher viral dose mimics blood transfusion, whereas the lower dose mimics mosquito bites, sexual and intrafamilial transmission.

Viral genotype in chronicification of acute infection in adults

Genotypes B and C can also be transmitted in adults by sex, close family contact, injury sustained during visits to the barber's shop, etc., leading to acute symptomatic infection. Studies from Japan suggest that only approximately 1% of such infections will become chronic in contrast to 5-10% chronicity rate associated with adulthood infection in Western countries. Moreover, the prevalence of genotype C2 was lower in acute hepatitis patients than in chronic carriers, indicative of its benign role in acute infection (which is likely under-reported) and increased role in chronicity, compared to genotype B1.56 Similarly, chronicification of acute adulthood infection was more common with genotype C2 than B2 in China with more prevalent sexual transmission of B2 but household transmission of C2.57 Recently, acute HBV infection in metropolitan areas of Japan has been increasingly attributed to the exotic genotype A, which is transmitted through promiscuous sex or homosexual behavior.58 Remarkably, as much as 20% of Japanese patients infected with genotype A became chronic carriers,59,60 thus confirming the role of the virus in determining the outcome of infection (Table 4). Through lifestyle changes coupled with universal vaccination of newborns, which provides protection to the younger generation, genotype A may increasingly become a source of chronic infection among adults in Asia. Studies from Europe found that most chronic active hepatitis patients were infected with genotype A, and most cases of acute resolving hepatitis were associated with genotype D.61,62 These observations suggest a higher tendency of genotype A to induce chronic infection than genotype D (Table 4). In contrast to sexual transmission, which is the preferred route for genotype A, genotype D is primarily transmitted by blood transfusion and transplantation.63

Table 4. Comparison of clinical features among different HBV genotypes.

| Acute infection: chronicity rate | A>D; C>B (C2>B1; C2>B2); A>C>B |

| Acute infection: rate of fulminant hepatitis | D>A; B>C (B1>C2) |

| Length of HBeAg+ phase of infection | A>D; C>B (by 10 yrs); C>A, B, D, F |

| Emergence of HBeAg-negative mutation | D>>A |

| Emergence of core promoter mutations | A>D; C>B |

| Response to interferon therapy | A>D: B>C |

| Age of HCC development | B2 earlier than C2; F earlier than A, C, D |

| Lifelong HCC risk | C2>B2; F>D |

Viral genotype in prolongation of chronic infection

Chronic HBV infection associated with perinatal transmission consists of the immune tolerance phase, immune active phase, and inactive phase. During the immune active phase, the cytotoxic T lymphocyte (CTL) response begins to destroy a fraction of HBV-infected hepatocytes leading to reduced viral load, liver damage (hepatitis) and regeneration. Because the CTL response associated with chronic HBV infection is weak and inefficient, the cycle of hepatocyte destruction, regeneration, and reinfection by HBV continues for decades before the replicating virus is finally eliminated from the liver and bloodstream. The loss of HBeAg followed by the subsequent rise of anti-HBe antibodies (HBeAg seroconversion) marks the turning point in the battle between the virus and the host because it is often accompanied by a marked drop in viremia and reduced long-term risks such as liver cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). Importantly, patients infected with genotype C seroconvert from HBeAg to anti-HBe about a decade later than genotype B patients,46,64,65,66 suggesting a protracted immune clearance phase and more liver damage. Among Alaskan natives infected with genotypes A, B, C, D, and F, genotype C patients also seroconvert at a much older age.67

VIRAL FACTORS CAUSING PREDISPOSITION TO FULMINANT HEPATITIS

Precore and core promoter mutations

Acute HBV infection sometimes leads to fulminant hepatitis. Because the wild-type virus is non-cytopathic, fulminant hepatitis most likely stems from robust HBV replication and/or antigen expression in a large percentage of hepatocytes, in conjunction with an equally strong and rapid CTL response. The consequences are massive hepatocyte destruction, liver failure, and high mortality rate. To a large extent, fulminant hepatitis is the opposite of immune tolerance induced during perinatal transmission, which triggers viral persistence but minimal liver disease (Table 5). Thus, while the wild-type virus is selected during perinatal transmission, certain mutations are associated with fulminant hepatitis. First, HBV isolates implicated in fulminant hepatitis often harbor the G1896A mutation to prevent HBeAg expression.68,69,70,71 Loss of immune tolerance induction by HBeAg could strengthen the CTL response against the related core protein. Second, core promoter mutations including the A1762T and G1764A hot spot mutations and those at positions 1753, 1757, 1766, 1768 have also been linked to fulminant hepatitis.72,73,74 As mentioned above, the presence of multiple core promoter mutations can dramatically enhance genome replication,75 which simultaneously increases core protein expression, triggering a strong CTL response. The most compelling evidence for viral factors leading in fulminant hepatitis came from characterization of isolates responsible for disease outbreak (clustered cases). Liang and colleagues identified a genotype D isolate responsible for an outbreak of fulminant hepatitis in Israel with 100% mortality of the 5 acutely infected individuals.76 This isolate contained G1896A precore mutation to abolish HBeAg expression and had an extremely high replication capacity in transfected cells because of the C1766T/T1768A double-mutation in the core promoter.74,77 In another study, five strains of genotype A were implicated in nosocomial HBV infections in France.78 The strain implicated in three cases of fatal sub-fulminant hepatitis harbored core promoter mutations, G1896A precore mutation (accompanied by the C1858T covariation), and several amino acid changes in the immune epitopes of the core protein. None of these mutations were found in the other four strains implicated in acute mild liver diseases. In Japan, a B2 isolate was implicated in five cases of fulminant hepatitis (four being fatal), apparently transmitted through contact with the same physician. The isolate contained G1896A and A1762T/G1764A mutations, as well as missense mutations in the core gene.79,80 Finally, an outbreak of acute hepatitis in India was traced to therapeutic injections from the same physician.81 Although multiple HBV isolates were involved in this outbreak, all the fatal fulminant hepatitis cases were caused by genotype D1 containing both precore and core promoter mutations. In contrast, most patients with a self-limiting disease were infected with genotype D2, and most such isolates harbored a wild-type precore and core promoter sequence.

Table 5. Contrasting features between induction of chronic infection and induction of fulminant hepatitis.

| Chronic infection | Fulminant hepatitis | |

|---|---|---|

| Often occurs in | Infants | Adults |

| Mutations involved | None | Precore; core promoter |

| Genotype involved | C>B; A>D; A>C>B | B>C; D>A |

| HBeAg expression | High | Negative (precore mutation) |

| Replication capacity | Low (wild-type virus) | High (core promoter mutations) |

HBV genotype

Consistent with the much higher prevalence of G1896A mutation in genotype D than in A, genotype D is more likely to cause fulminant hepatitis than A.73,82 In Japan genotype B1 was found to pose a greater risk for fulminant hepatitis than genotype C2.56,83 Similarly, in China genotype B2 has a stronger association with acute-on-chronic liver failure than genotype C.84 Overall, HBV genotypes that are prone to chronicification of acute infection are less involved in fulminant hepatitis, thus highlighting the importance of immune tolerance for the establishment of chronic infection but immune attack for the induction of fulminant hepatitis (Table 5).

VIRAL FACTORS LEADING TO PREDISPOSITION TO HCC FORMATION

HCC is the long-term consequence of chronic HBV infection. In most cases, HCC develops after decades of chronic infection and is preceded by liver cirrhosis. It is possible that 2 independent mechanisms work synergistically to promote hepatocarcinogenesis. First, liver damage and regeneration during the immune clearance phase indirectly increase the HCC risks. In HBV transgenic mice, HCC development is preceded by strong, sustained hepatocyte proliferation.85 It is anticipated that the HCC risk is influenced by both the duration of the immune clearance phase and the extent of hepatocyte turnover. Second, certain HBV gene products may directly promote hepatocyte proliferation or transformation, such as the mutant HBx protein and truncated envelope proteins.

Viral load

Although most patients are HBeAg negative and show low viremia at the time of HCC detection, a prolonged HBeAg+ phase and high levels of HBV replication combined with liver injury (ALT elevation) are responsible for HCC formation. A comparison of HBeAg+ with HBeAg- patients from Taiwan showed a more than 3 fold higher incidence of HCC in the former group during the 9-year follow up.86 Prospective studies from Japan, China, and Taiwan also confirmed the role of a high viral load as a risk factor for HCC development.87,88,89,90,91,92 Therefore, a reduction of viral load by antiviral therapy is predicted to reduce the HCC risk.

Viral genotype

HBV genotypes A, B, C, D, and F are known to cause HCC. A1 is the major genotype in sub-Saharan Africa and responsible for the majority of HCC cases detected there.93 Genotype D is more prevalent than genotype A (A1) in India, but both have been implicated in HCC development.94,95,96 Among Alaskan natives, genotypes F and D account for 18% and 58% of HBV infections, respectively, but 68% and 11% of HCC cases, respectively, suggesting a considerably higher oncogenicity of genotype F (Table 4).97 Intriguingly, among these Alaskan natives, the median age of HCC diagnosis was only 22.5 years for genotype F infection compared to 60 years for infection with genotypes D/A/C. The most exhaustive comparison has been performed between genotypes B and C in the Far East, where HBV-related HCC is most common. In Taiwan, genotype C was associated with liver cirrhosis and late-onset HCC, whereas genotype B was most likely responsible for the majority of HCC cases detected before 35 years, often without cirrhosis.98,99 Studies from Japan confirmed an increased severity of liver disease associated with genotype C, but these studies reported 10 to 15 years of delay in HCC development in genotype B infections.64,100 Interestingly, the core gene of the B2 subtype found in Taiwan, Hong Kong and China, but not of the B1 subtype circulating in Japan, is similar to that of genotype C. This is possibly due to a prior recombination event.101 According to most studies from Hong Kong, China, and Taiwan, the lifelong risk for HCC development is higher for genotype C than genotype B (Table 4).32,90,102,103,104

Core promoter mutations

In addition to their involvement in fulminant hepatitis, core promoter mutations are also implicated in HCC development.104,105,106,107,108,109 This association has been established for genotypes A, B, C, and D but not F.96,97 However, core promoter (and other) mutations accumulate over time, with their highest prevalence being detected at an old age, which is when most HCC cases are detected. The cross-sectional nature of most studies raises the question of whether the mutations trigger hepatocarcinogenesis or whether they have a selective advantage in cancerous liver tissue, but studies on age-matched controls suggest that the correlation is significant. More importantly, long-term large-scale prospective studies have confirmed the predictive value of core promoter mutations for HCC.110,111 Genotype C, especially the C1 subtype prevalent in Hong Kong, has a much higher incidence of the 1762/1764 double-mutation than genotype B (31, 32, 45, 46, 108, 112). Because most control genotype C patients have also acquired these mutations, the association of core promoter mutations with HCC is sometimes absent for genotype C in cross-sectional studies.42,102 Therefore the association of genotype C1 with HCC development could be secondary to core promoter mutations.102,111 However, genotype C2 remains an independent risk factor for HCC development.90,104,113

X gene mutations

In addition to the common 1762/1764 double-mutation, mutations at positions 1753, 1766, and 1768 in the core promoter and 1653 in enhancer II have also been linked to HCC.42,113,114,115,116,117 For genotype C the C1766T and T1768A mutations also contribute to liver cirrhosis.118 Because mutations at 1753, 1766, and 1768 have also been implicated in fulminant hepatitis and increase genome replication,75,77 they could promote cirrhosis/HCC through increased core protein expression, which increases hepatocyte turnover in conjunction with CTL responses. In addition, the core promoter overlaps with the X gene, and the T1753C, A1762T, G1764A, and T1768A mutations induce I127T, K130M, V131I, and F132Y changes near the C-terminus of the HBx protein. Previous studies have shown that wild-type HBx has inhibitory effects on cell proliferation and transformation. These effects were abrogated by C-terminal truncation of the HBx protein, which resulted from HBV DNA integration into HCC tissues.119,120,121 The amino acid substitutions associated with core promoter mutations also abolished the inhibitory effect.42 Wild-type HBx increased promoter activity for the tumor suppressor p21, which was blocked by the K130M mutation in HBx.122 Our recent study confirmed that the mutant HBx that is generated by core promoter mutations downregulates p21 protein levels.123

Deletions in the preS region of the envelope gene

Deletions at the 3' end of the preS1 region and especially the 5' end of the preS2 region have been implicated in HCC formation.106,124,125 These deletions are usually in-frame and generate a shortened L protein lacking the C-terminal preS1 domain and/or the N-terminal preS2 domain. These deletions often remove B-cell or T-cell epitopes in the L protein, thereby suggesting a mechanism of viral immune escape. M protein expression is often lost by the deletion of or additional point mutations in the preS2 AUG codon. PreS deletion-mutants can also be detected in chronic hepatitis patients, and their prevalence increases as the liver disease progresses to cirrhosis and HCC.118,126,127,128 So far, preS deletions have been detected mostly in genotypes B and C, with most studies suggesting a higher prevalence in genotype C.118,125,127,128 Although the cross-sectional nature of most studies cannot prove a cause and effect relationship, the high prevalence of such deletions in cases of childhood HCC supports their causative role.129,130 Moreover, a longitudinal study confirmed the predictive value of preS deletions for HCC development.118

Substantial progress has been made in elucidating the mechanisms by which deletions in the L protein potentially contribute to hepatocarcinogenesis. Deletions in the preS1 and preS2 regions have been linked to different types of ground glass hepatocytes, with the type associated with preS2 deletion being clustered (most likely because of proliferation of the hepatocyte harboring the deletion).131 Transfection experiments with mutant L protein constructs suggest that both types of deletion trigger endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress, resulting in oxidative stress and DNA damage.131,132 Moreover, the L protein of the specific preS2 deletion-mutant studied caused the degradation of cyclin-dependent kinase p27, phosphorylation of retinoblastoma protein, cell cycle progression, and increased cell growth and transformation.133,134 Transgenic mice expressing this preS2 deletion-mutant of L protein showed nodular liver surface and hepatocyte dysplasia.134

MUTANTS SELECTED BY ANTIVIRAL THERAPY AND VACCINATION

The precore/core promoter mutants and preS deletion-mutants are selected during the natural course of chronic HBV infection. With our efforts to control HBV infection through vaccination and antiviral therapy, novel resistant mutants have emerged. A better understanding of the biological properties of drug-resistant and vaccine escape mutants will help accurately estimate the threat they pose.

Drug-resistant mutants

Currently, pegylated interferon and nucleos(t)ide analogues (NAs) have been approved for treatment of chronic HBV infection. NAs inhibit minus-strand DNA synthesis from the pgRNA template (reverse transcription), although some NAs also affect plus-strand DNA synthesis. They can profoundly reduce DNA replication leading to a dramatic drop in viral titer in the blood. Unfortunately, NA-mediated suppression of HBV DNA replication is often not followed by HBeAg or HBsAg seroconversion, a marker of sustained virological response. Long-term treatment with the NAs, especially lamivudine, and to a lesser extent adefovir, results in rebound of viral load as a result of the selection of drug-resistant mutants.

The HBV P protein consists of 4 domains in the following order: terminal protein (TP), spacer, reverse transcriptase (RT), and RNase H. Resistance to NAs is caused by missense mutations in the RT domain such as rtA181V/T and rtN236T for adefovir. The rtM204V/I mutation confers resistance to lamivudine but also reduces replication capacity, which can be rescued by additional mutations such as rtV173L or rtL180M. Entecavir has a higher genetic barrier to resistance because three simultaneous mutations are needed to generate a resistant virus.135 Five years after therapy, resistance was 80% to lamivudine and 29% to adefovir but only 1.2% to entecavir.136 Owing to the overlap of the P gene with the envelope gene (Figure 2), many NA-resistant mutations are accompanied by amino acid changes in the S domain of the 3 envelope proteins. Some mutations introduce a premature termination codon in the S gene resulting in truncated envelope proteins. For example, the rtM204I mutation may cause sW196* (31 amino acid deletion), while the rtA181T mutation causes sW172* (55 amino acid deletion). The sW172* mutation has been shown to prevent the secretion of both virions and subviral particles,137 and a patient from Taiwan with the rtA181T/sW172* mutation developed HCC.138 This is reminiscent of preS1/preS2 deletions, which retain the envelope proteins and increase the risk for HCC. Further studies are necessary to determine whether the truncation of envelope proteins by drug-resistant mutations increases the HCC risk as well.

Vaccine escape mutants

Vaccination with a genetically engineered S protein is very effective at preventing de novo HBV infection if administered prior to exposure. However, in HBV-endemic areas, the vertical route of HBV transmission poses a special challenge. In such cases, the administration of hepatitis B immunoglobulin (HBIG) immediately after birth is required to neutralize infectious virions coming from maternal blood. Subsequent vaccination guarantees a stable supply of neutralizing antibodies. Despite the combination of HBIG with vaccination, approximately 5% of perinatal transmissions cannot be blocked, especially for genotype C.139 The reasons for breakthrough infection include high maternal viral load, intrauterine infection,140 and vaccine escape mutants, first recognized by Carman and colleagues.141,142,143 The same mutants are also responsible for HBV reinfection of newly grafted liver in former hepatitis B patients despite prophylaxis with HBIG.144,145,146,147

The vaccine escape mutants (also known as immune escape mutants) harbor amino acid substitutions in the “a” determinant of the S protein (residues 124–147 in the S domain), the major target of neutralizing antibodies elicited by the HBV vaccine. The most common mutation is G145R/A. The mutations diminish the binding of antibodies raised against wild-type S protein to virions and subviral particles.148,149,150 The former causes breakthrough infections, while the latter leads to diagnostic failure. Presently, the threat posed by immune escape mutants remains uncertain. In Taiwan the prevalence of immune escape mutants increased from 7.8% to 22.6% at 20 years after universal vaccination, but the HBV infection rate among children has declined from 9.6% to 0.5%.151,152 Transfection experiments suggested that the G145R and many other immune escape mutants are impaired in virion secretion to various extents,153,154,155,156 suggesting that the mutants are less fit than the wild-type virus. Nevertheless, an M133T mutation conferring a novel N-linked glycosylation site could efficiently rescue virion secretion of the G145R mutant, and to a lesser extent, of several other immune escape mutants.154,156 Experiments in the hepatitis δ virus, which employs HBV envelope proteins for release from and entry into hepatocytes, suggest that many immune escape mutants are impaired in infectivity.157,158 However, the G145R mutant was found to be as infectious as the wild-type virus. Therefore, the G145R mutant accompanied by a compensatory mutation to restore virion secretion might pose a serious threat to the vaccination program.

Occult HBV infection

Immune escape mutants can cause occult infection, which is defined by the presence of HBV DNA in the liver or blood despite a lack of detectable HBsAg.159,160 Such occult infections can transmit HBV through blood transfusion and have also been linked to HCC. Because the ratio of subviral particles (HBsAg) to virions (HBV DNA) is approximately 1000 to 100 000, most occult HBV infections represent low level viremia (with HBV DNA detectable only by sensitive PCR detection methods). Mutations in the “a” determinant render the low level of HBsAg undetectable. Occult HBV infection could represent the window period of HBsAg seroconversion, when HBsAg has disappeared (or is in complex with the corresponding antibody) and the HBV DNA level is very low. Alternatively, it could be associated with HBV/HCV (hepatitis C virus) coinfection or HBV/HIV coinfection. With the successful therapeutic control of conventional HBV infection more attention is likely to be paid to occult infection in the future.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by Research Scholar Grant 06-059-01-MBC from the American Cancer Society and the National Institutes of Health grants CA133976, CA109733, AA08169, and AA19072.

References

- Ganem D, Prince AM. Hepatitis B virus infection—natural history and clinical consequences. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:1118–1129. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra031087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Junker-Niepmann M, Bartenschlager R, Schaller H. A short cis-acting sequence is required for hepatitis B virus pregenome encapsidation and sufficient for packaging of foreign RNA. EMBO J. 1990;9:3389–3396. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1990.tb07540.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia T, Li J, Sureau C, et al. Drastic reduction in the production of subviral particles does not impair hepatitis B virus virion secretion. J Virol. 2009;83:1152–11165. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00905-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruss V, Ganem D. The role of envelope proteins in hepatitis B virus assembly. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88:1059–1063. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.3.1059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernholz D, Galle PR, Stemler M, Brunetto M, Bonino F, Will H. Infectious hepatitis B virus variant defective in pre-S2 protein expression in a chronic carrier. Virology. 1993;194:137–148. doi: 10.1006/viro.1993.1243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ito K, Kim KH, Lok AS, Tong S. Characterization of genotype-specific carboxyl-terminal cleavage sites of hepatitis B virus e antigen precursor and identification of furin as the candidate enzyme. J Virol. 2009;83:3507–3517. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02348-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ou JH, Laub O, Rutter WJ. Hepatitis B virus gene function: the precore region targets the core antigen to cellular membranes and causes the secretion of the e antigen. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1986;83:1578–1582. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.6.1578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Messageot F, Salhi S, Eon P, Rossignol JM. Proteolytic processing of the hepatitis B virus e antigen precursor. Cleavage at two furin consensus sequences. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:891–895. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M207634200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norder H, Courouce AM, Coursaget P, et al. Genetic diversity of hepatitis B virus strains derived worldwide: genotypes, subgenotypes, and HBsAg subtypes. Intervirology. 2004;47:289–309. doi: 10.1159/000080872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chu CJ, Lok AS. Clinical significance of hepatitis B virus genotypes. Hepatology. 2002;35:1274–1276. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2002.33161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kramvis A, Arakawa K, Yu MC, Nogueira R, Stram DO, Kew MC. Relationship of serological subtype, basic core promoter and precore mutations to genotypes/subgenotypes of hepatitis B virus. J Med Virol. 2008;80:27–46. doi: 10.1002/jmv.21049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanwar S, Dusheiko G. Is there any value to hepatitis B virus genotype analysis. Curr Gastroenterol Rep. 2012;14:37–46. doi: 10.1007/s11894-011-0233-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang C, Enders G, Sprengel R, Peters N, Varmus HE, Ganem D. Expression of the precore region of an avian hepatitis B virus is not required for viral replication. J Virol. 1987;61:3322–3325. doi: 10.1128/jvi.61.10.3322-3325.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schlicht HJ, Salfeld J, Schaller H. The duck hepatitis B virus pre-C region encodes a signal sequence which is essential for synthesis and secretion of processed core proteins but not for virus formation. J Virol. 1987;61:3701–3709. doi: 10.1128/jvi.61.12.3701-3709.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brunetto MR, Stemler M, Bonino F, et al. A new hepatitis B virus strain in patients with severe anti-HBe positive chronic hepatitis B. J Hepatol. 1990;10:258–261. doi: 10.1016/0168-8278(90)90062-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tong SP, Li JS, Vitvitski L, Trepo C. Active hepatitis B virus replication in the presence of anti-HBe is associated with viral variants containing an inactive pre-C region. Virology. 1990;176:596–603. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(90)90030-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carman WF, Jacyna MR, Hadziyannis S, et al. Mutation preventing formation of hepatitis B e antigen in patients with chronic hepatitis B infection. Lancet. 1989;2:588–591. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(89)90713-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okamoto H, Yotsumoto S, Akahane Y, et al. Hepatitis B viruses with precore region defects prevail in persistently infected hosts along with seroconversion to the antibody against e antigen. J Virol. 1990;64:1298–1303. doi: 10.1128/jvi.64.3.1298-1303.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J, Tong S, Vitvitski L, Zoulim F, Trepo C. Rapid detection and further characterization of infection with hepatitis B virus variants containing a stop codon in the distal pre-C region. J Gen Virol. 1990;71:1993–1998. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-71-9-1993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen HS, Kew MC, Hornbuckle WE, et al. The precore gene of the woodchuck hepatitis virus genome is not essential for viral replication in the natural host. J Virol. 1992;66:5682–5684. doi: 10.1128/jvi.66.9.5682-5684.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cote PJ, Korba BE, Miller RH, et al. Effects of age and viral determinants on chronicity as an outcome of experimental woodchuck hepatitis virus infection. Hepatology. 2000;31:190–200. doi: 10.1002/hep.510310128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kato H, Orito E, Gish RG, et al. Hepatitis B e antigen in sera from individuals infected with hepatitis B virus of genotype G. Hepatology. 2002;35:922–929. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2002.32096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milich DR, Schodel F, Hughes JL, Jones JE, Peterson DL. The hepatitis B virus core and e antigens elicit different Th cell subsets: antigen structure can affect Th cell phenotype. J Virol. 1997;71:2192–2201. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.3.2192-2201.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milich DR, Jones JE, Hughes JL, Price J, Raney AK, McLachlan A. Is a function of the secreted hepatitis B e antigen to induce immunologic tolerance in utero. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990;87:6599–6603. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.17.6599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milich DR, Chen MK, Hughes JL, Jones JE. The secreted hepatitis B precore antigen can modulate the immune response to the nucleocapsid: a mechanism for persistence. J Immunol. 1998;160:2013–2021. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen MT, Billaud JN, Sallberg M, et al. A function of the hepatitis B virus precore protein is to regulate the immune response to the core antigen. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:14913–14918. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0406282101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tong SP, Li JS, Vitvitski L, Trepo C. Replication capacities of natural and artificial precore stop codon mutants of hepatitis B virus: relevance of pregenome encapsidation signal. Virology. 1992;191:237–245. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(92)90185-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tong SP, Li JS, Vitvitski L, Kay A, Treepo C. Evidence for a base-paired region of hepatitis B virus pregenome encapsidation signal which influences the patterns of precore mutations abolishing HBe protein expression. J Virol. 1993;67:5651–5655. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.9.5651-5655.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li JS, Tong SP, Wen YM, Vitvitski L, Zhang Q, Trepo C. Hepatitis B virus genotype A rarely circulates as an HBe-minus mutant: possible contribution of a single nucleotide in the precore region. J Virol. 1993;67:5402–5410. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.9.5402-5410.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lok AS, Akarca U, Greene S. Mutations in the pre-core region of hepatitis B virus serve to enhance the stability of the secondary structure of the pre-genome encapsidation signal. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:4077–4081. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.9.4077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan HL, Tsui SK, Tse CH, et al. Epidemiological and virological characteristics of 2 subgroups of hepatitis B virus genotype C. J Infect Dis. 2005;191:2022–2032. doi: 10.1086/430324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Z, Tanaka Y, Huang Y, et al. Clinical and virological characteristics of hepatitis B virus subgenotypes Ba, C1, and C2 in China. J Clin Microbiol. 2007;45:1491–1496. doi: 10.1128/JCM.02157-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan J, Zhou B, Tanaka Y, et al. Hepatitis B virus (HBV) genotypes/subgenotypes in China: mutations in core promoter and precore/core and their clinical implications. J Clin Virol. 2007;39:87–93. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2007.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alestig E, Hannoun C, Horal P, Lindh M. Phylogenetic origin of hepatitis B virus strains with precore C-1858 variant. J Clin Microbiol. 2001;39:3200–3203. doi: 10.1128/JCM.39.9.3200-3203.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arauz-Ruiz P, Norder H, Visona KA, Magnius LO. Genotype F prevails in HBV infected patients of hispanic origin in Central America and may carry the precore stop mutant. J Med Virol. 1997;51:305–312. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norder H, Arauz-Ruiz P, Blitz L, Pujol FH, Echevarria JM, Magnius LO. The T(1858) variant predisposing to the precore stop mutation correlates with one of two major genotype F hepatitis B virus clades. J Gen Virol. 2003;84:2083–2087. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.19034-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okamoto H, Tsuda F, Akahane Y, et al. Hepatitis B virus with mutations in the core promoter for an e antigen-negative phenotype in carriers with antibody to e antigen. J Virol. 1994;68:8102–8110. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.12.8102-8110.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buckwold VE, Xu Z, Chen M, Yen TS, Ou JH. Effects of a naturally occurring mutation in the hepatitis B virus basal core promoter on precore gene expression and viral replication. J Virol. 1996;70:5845–5851. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.9.5845-5851.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scaglioni PP, Melegari M, Wands JR. Biologic properties of hepatitis B viral genomes with mutations in the precore promoter and precore open reading frame. Virology. 1997;233:374–381. doi: 10.1006/viro.1997.8594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moriyama K, Okamoto H, Tsuda F, Mayumi M. Reduced precore transcription and enhanced core-pregenome transcription of hepatitis B virus DNA after replacement of the precore-core promoter with sequences associated with e antigen-seronegative persistent infections. Virology. 1996;226:269–280. doi: 10.1006/viro.1996.0655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsai A, Kawai S, Kwei K, et al. Chimeric constructs between two hepatitis B virus genomes confirm transcriptional impact of core promoter mutations and reveal multiple effects of core gene mutations. Virology. 2009;387:364–372. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2009.03.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo X, Jin Y, Qian G, Tu H. Sequential accumulation of the mutations in core promoter of hepatitis B virus is associated with the development of hepatocellular carcinoma in Qidong, China. J Hepatol. 2008;49:718–725. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2008.06.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka Y, Hasegawa I, Kato T, et al. A case-control study for differences among hepatitis B virus infections of genotypes A (subtypes Aa and Ae) and D. Hepatology. 2004;40:747–755. doi: 10.1002/hep.20365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grabarczyk P, Garmiri P, Liszewski G, et al. Molecular and serological characterization of hepatitis B virus genotype A and D infected blood donors in Poland. J Viral Hepat. 2010;17:444–452. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2893.2009.01192.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orito E, Mizokami M, Sakugawa H, et al. A case-control study for clinical and molecular biological differences between hepatitis B viruses of genotypes B and C. Japan HBV Genotype Research Group. Hepatology. 2001;33:218–223. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2001.20532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuen MF, Sablon E, Yuan HJ, et al. Significance of hepatitis B genotype in acute exacerbation, HBeAg seroconversion, cirrhosis-related complications, and hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology. 2003;37:562–567. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2003.50098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindh M, Hannoun C, Dhillon AP, Norkrans G, Horal P. Core promoter mutations and genotypes in relation to viral replication and liver damage in East Asian hepatitis B virus carriers. J Infect Dis. 1999;179:775–782. doi: 10.1086/314688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qin Y, Tang X, Garcia T, et al. Hepatitis B virus genotype C isolates with wild-type core promoter sequence replicate less efficiently than genotype B isolates but possess higher virion secretion capacity. J Virol. 2011;85:10167–10177. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00819-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nie J, Li J, Sun K, et al. HBV/D1: a major HBV subgenotype circulating in Uyghur patients with chronic HBV infection in Xinjiang, China. Arch Virol. 2012;157:1541–1549. doi: 10.1007/s00705-012-1325-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inui A, Komatsu H, Sogo T, Nagai T, Abe K, Fujisawa T. Hepatitis B virus genotypes in children and adolescents in Japan: before and after immunization for the prevention of mother to infant transmission of hepatitis B virus. J Med Virol. 2007;79:670–675. doi: 10.1002/jmv.20884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coursaget P, Yvonnet B, Chotard J, et al. Age- and sex-related study of hepatitis B virus chronic carrier state in infants from an endemic area (Senegal) J Med Virol. 1987;22:1–5. doi: 10.1002/jmv.1890220102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jilbert A, Botten J, Miller D, et al. Characterization of age and dose related outcomes of duck hepatitis B virus infection. Virology. 1998;244:273–282. doi: 10.1006/viro.1998.9095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsia CC, Purcell RH, Farshid M, Lachenbruch PA, Yu MY. Quantification of hepatitis B virus genomes and infectivity in human serum samples. Transfusion. 2006;46:1829–1835. doi: 10.1111/j.1537-2995.2006.00974.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Komiya Y, Katayama K, Yugi H, et al. Minimum infectious dose of hepatitis B virus in chimpanzees and difference in the dynamics of viremia between genotype A and genotype C. Transfusion. 2008;48:286–294. doi: 10.1111/j.1537-2995.2007.01522.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asabe S, Wieland SF, Chattopadhyay PK, et al. The size of the viral inoculum contributes to the outcome of hepatitis B virus infection. J Virol. 2009;83:9652–9662. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00867-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imamura T, Yokosuka O, Kurihara T, et al. Distribution of hepatitis B viral genotypes and mutations in the core promoter and precore regions in acute forms of liver disease in patients from Chiba, Japan. Gut. 2003;52:1630–1637. doi: 10.1136/gut.52.11.1630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang HW, Yin JH, Li YT, et al. Risk factors for acute hepatitis B and its progression to chronic hepatitis in Shanghai, China. Gut. 2008;57:1713–1720. doi: 10.1136/gut.2008.157149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuura K, Tanaka Y, Hige S, et al. Distribution of hepatitis B virus genotypes among patients with chronic infection in Japan shifting toward an increase of genotype A. J Clin Microbiol. 2009;47:1476–1483. doi: 10.1128/JCM.02081-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki Y, Kobayashi M, Ikeda K, et al. Persistence of acute infection with hepatitis B virus genotype A and treatment in Japan. J Med Virol. 2005;76:33–39. doi: 10.1002/jmv.20320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobayashi M, Suzuki F, Arase Y, et al. Infection with hepatitis B virus genotype A in Tokyo, Japan during 1976 through 2001. J Gastroenterol. 2004;39:844–850. doi: 10.1007/s00535-004-1400-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayerat C, Mantegani A, Frei PC. Does hepatitis B virus (HBV) genotype influence the clinical outcome of HBV infection. J Viral Hepat. 1999;6:299–304. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2893.1999.00174.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez-Frias F, Jardi R, Buti M, et al. Hepatitis B virus genotypes and G1896A precore mutation in 486 Spanish patients with acute and chronic HBV infection. J Viral Hepat. 2006;13:343–350. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2893.2005.00691.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halfon P, Bourliere M, Pol S, et al. Multicentre study of hepatitis B virus genotypes in France: correlation with liver fibrosis and hepatitis B e antigen status. J Viral Hepat. 2006;13:329–335. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2893.2005.00692.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orito E, Ichida T, Sakugawa H, et al. Geographic distribution of hepatitis B virus (HBV) genotype in patients with chronic HBV infection in Japan. Hepatology. 2001;34:590–594. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2001.27221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kao JH, Chen PJ, Lai MY, Chen DS. Hepatitis B virus genotypes and spontaneous hepatitis B e antigen seroconversion in Taiwanese hepatitis B carriers. J Med Virol. 2004;72:363–369. doi: 10.1002/jmv.10534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chu CJ, Hussain M, Lok AS. Hepatitis B virus genotype B is associated with earlier HBeAg seroconversion compared with hepatitis B virus genotype C. Gastroenterology. 2002;122:1756–1762. doi: 10.1053/gast.2002.33588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Livingston SE, Simonetti JP, Bulkow LR, et al. Clearance of hepatitis B e antigen in patients with chronic hepatitis B and genotypes A, B, C, D, and F. Gastroenterology. 2007;133:1452–1457. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carman WF, Fagan EA, Hadziyannis S, et al. Association of a precore genomic variant of hepatitis B virus with fulminant hepatitis. Hepatology. 1991;14:219–222. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kosaka Y, Takase K, Kojima M, et al. Fulminant hepatitis B: induction by hepatitis B virus mutants defective in the precore region and incapable of encoding e antigen. Gastroenterology. 1991;100:1087–1094. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(91)90286-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Omata M, Ehata T, Yokosuka O, Hosoda K, Ohto M. Mutations in the precore region of hepatitis B virus DNA in patients with fulminant and severe hepatitis. N Engl J Med. 1991;324:1699–1704. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199106133242404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yotsumoto S, Kojima M, Shoji I, Yamamoto K, Okamoto H, Mishiro S. Fulminant hepatitis related to transmission of hepatitis B variants with precore mutations between spouses. Hepatology. 1992;16:31–35. doi: 10.1002/hep.1840160107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sato S, Suzuki K, Akahane Y, et al. Hepatitis B virus strains with mutations in the core promoter in patients with fulminant hepatitis. Ann Intern Med. 1995;122:241–248. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-122-4-199502150-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedt M, Gerner P, Lausch E, Trubel H, Zabel B, Wirth S. Mutations in the basic core promotor and the precore region of hepatitis B virus and their selection in children with fulminant and chronic hepatitis B. Hepatology. 1999;29:1252–1258. doi: 10.1002/hep.510290418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasegawa K, Huang J, Rogers SA, Blum HE, Liang TJ. Enhanced replication of a hepatitis B virus mutant associated with an epidemic of fulminant hepatitis. J Virol. 1994;68:1651–1659. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.3.1651-1659.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parekh S, Zoulim F, Ahn SH, et al. Genome replication, virion secretion, and e antigen expression of naturally occurring hepatitis B virus core promoter mutants. J Virol. 2003;77:6601–6612. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.12.6601-6612.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang TJ, Hasegawa K, Rimon N, Wands JR, Ben-Porath E. A hepatitis B virus mutant associated with an epidemic of fulminant hepatitis. N Engl J Med. 1991;324:1705–1709. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199106133242405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baumert TF, Rogers SA, Hasegawa K, Liang TJ. Two core promotor mutations identified in a hepatitis B virus strain associated with fulminant hepatitis result in enhanced viral replication. J Clin Invest. 1996;98:2268–2276. doi: 10.1172/JCI119037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stuyver L, De Gendt S, Cadranel JF, et al. Three cases of severe subfulminant hepatitis in heart-transplanted patients after nosocomial transmission of a mutant hepatitis B virus. Hepatology. 1999;29:1876–1883. doi: 10.1002/hep.510290614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inoue J, Ueno Y, Nagasaki F, et al. Enhanced intracellular retention of a hepatitis B virus strain associated with fulminant hepatitis. Virology. 2009;395:202–209. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2009.09.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagasaki F, Ueno Y, Niitsuma H, et al. Analysis of the entire nucleotide sequence of hepatitis B causing consecutive cases of fatal fulminant hepatitis in Miyagi Prefecture Japan. J Med Virol. 2008;80:967–973. doi: 10.1002/jmv.21167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arankalle VA, Gandhi S, Lole KS, Chadha MS, Gupte GM, Lokhande MU. An outbreak of hepatitis B with high mortality in India: association with precore, basal core promoter mutants and improperly sterilized syringes. J Viral Hepat. 2011;18:e20–28. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2893.2010.01391.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McMillan JS, Bowden DS, Angus PW, McCaughan GW, Locarnini SA. Mutations in the hepatitis B virus precore/core gene and core promoter in patients with severe recurrent disease following liver transplantation. Hepatology. 1996;24:1371–1378. doi: 10.1002/hep.510240610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ozasa A, Tanaka Y, Orito E, et al. Influence of genotypes and precore mutations on fulminant or chronic outcome of acute hepatitis B virus infection. Hepatology. 2006;44:326–334. doi: 10.1002/hep.21249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ren X, Xu Z, Liu Y, et al. Hepatitis B virus genotype and basal core promoter/precore mutations are associated with hepatitis B-related acute-on-chronic liver failure without pre-existing liver cirrhosis. J Viral Hepat. 2010;17:887–895. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2893.2009.01254.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang SN, Chisari FV. Strong, sustained hepatocellular proliferation precedes hepatocarcinogenesis in hepatitis B surface antigen transgenic mice. Hepatology. 1995;21:620–626. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang HI, Lu SN, Yun-Fan liaw SLY, et al. Hepatitis B e Antigen and the Risk of Hepatocellular Carcinoma. New Engl J Med. 2002;347:168–173. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa013215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishikawa T, Ichida T, Yamagiwa S, et al. High viral loads, serum alanine aminotransferase and gender are predictive factors for the development of hepatocellular carcinoma from viral compensated liver cirrhosis. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2001;16:1274–1281. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1746.2001.02616.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohata K, Hamasaki K, Toriyama K, Ishikawa H, Nakao K, Eguchi K. High viral load is a risk factor for hepatocellular carcinoma in patients with chronic hepatitis B virus infection. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2004;19:670–675. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2004.03360.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang B, Kruger WD, Chen G, et al. Hepatitis B viremia is associated with increased risk of hepatocellular carcinoma in chronic carriers. J Med Virol. 2004;72:35–40. doi: 10.1002/jmv.10559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu MW, Yeh SH, Chen PJ, et al. Hepatitis B virus genotype and DNA level and hepatocellular carcinoma: a prospective study in men. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2005;97:265–272. doi: 10.1093/jnci/dji043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu CF, Yu MW, Lin CL, et al. Long-term tracking of hepatitis B viral load and the relationship with risk for hepatocellular carcinoma in men. Carcinogenesis. 2008;29:106–112. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgm252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen CJ, Yang HI, Su J, et al. Risk of hepatocellular carcinoma across a biological gradient of serum hepatitis B virus DNA level. JAMA. 2006;295:65–73. doi: 10.1001/jama.295.1.65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kew MC, Kramvis A, Yu MC, Arakawa K, Hodkinson J. Increased hepatocarcinogenic potential of hepatitis B virus genotype A in Bantu-speaking sub-saharan Africans. J Med Virol. 2005;75:513–521. doi: 10.1002/jmv.20311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thakur V, Guptan RC, Kazim SN, Malhotra V, Sarin SK. Profile, spectrum and significance of HBV genotypes in chronic liver disease patients in the Indian subcontinent. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2002;17:165–170. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1746.2002.02605.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madan K, Batra Y, Sreenivas V, et al. HBV genotypes in India: do they influence disease severity. Hepatol Res. 2009;39:157–163. doi: 10.1111/j.1872-034X.2008.00417.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asim M, Malik A, Sarma MP, et al. Hepatitis B virus BCP, Precore/core, X gene mutations/genotypes and the risk of hepatocellular carcinoma in India. J Med Virol. 2010;82:1115–1125. doi: 10.1002/jmv.21774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Livingston SE, Simonetti JP, McMahon BJ, et al. Hepatitis B virus genotypes in Alaska Native people with hepatocellular carcinoma: preponderance of genotype F. J Infect Dis. 2007;195:5–11. doi: 10.1086/509894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kao JH, Chen PJ, Lai MY, Chen DS. Hepatitis B genotypes correlate with clinical outcomes in patients with chronic hepatitis B. Gastroenterology. 2000;118:554–559. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(00)70261-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chu CM, Liaw YF. Genotype C hepatitis B virus infection is associated with a higher risk of reactivation of hepatitis B and progression to cirrhosis than genotype B: a longitudinal study of hepatitis B e antigen-positive patients with normal aminotransferase levels at baseline. J Hepatol. 2005;43:411–417. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2005.03.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sumi H, Yokosuka O, Seki N, et al. Influence of hepatitis B virus genotypes on the progression of chronic type B liver disease. Hepatology. 2003;37:19–26. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2003.50036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sugauchi F, Orito E, Ichida T, et al. Hepatitis B virus of genotype B with or without recombination with genotype C over the precore region plus the core gene. J Virol. 2002;76:5985–5992. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.12.5985-5992.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuen MF, Tanaka Y, Mizokami M, et al. Role of hepatitis B virus genotypes Ba and C, core promoter and precore mutations on hepatocellular carcinoma: a case control study. Carcinogenesis. 2004;25:1593–1598. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgh172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan HL, Hui AY, Wong ML, et al. Genotype C hepatitis B virus infection is associated with an increased risk of hepatocellular carcinoma. Gut. 2004;53:1494–1498. doi: 10.1136/gut.2003.033324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu S, Xie J, Yin J, et al. A matched case-control study of hepatitis B virus mutations in the preS and core promoter regions associated independently with hepatocellular carcinoma. J Med Virol. 2011;83:45–53. doi: 10.1002/jmv.21829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsia CC, Yuwen H, Tabor E. Hot-spot mutations in hepatitis B virus X gene in hepatocellular carcinoma. Lancet. 1996;348:625–626. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)64851-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi K, Akahane Y, Hino K, Ohta Y, Mishiro S. Hepatitis B virus genomic sequence in the circulation of hepatocellular carcinoma patients: comparative analysis of 40 full-length isolates. Arch Virol. 1998;143:2313–2326. doi: 10.1007/s007050050463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baptista M, Kramvis A, Kew MC. High prevalence of 1762(T) 1764(A) mutations in the basic core promoter of hepatitis B virus isolated from black Africans with hepatocellular carcinoma compared with asymptomatic carriers. Hepatology. 1999;29:946–953. doi: 10.1002/hep.510290336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kao JH, Chen PJ, Lai MY, Chen DS. Basal core promoter mutations of hepatitis B virus increase the risk of hepatocellular carcinoma in hepatitis B carriers. Gastroenterology. 2003;124:327–334. doi: 10.1053/gast.2003.50053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuang SY, Jackson PE, Wang JB, et al. Specific mutations of hepatitis B virus in plasma predict liver cancer development. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:3575–3580. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0308232100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chou YC, Yu MW, Wu CF, et al. Temporal relationship between hepatitis B virus enhancer II/basal core promoter sequence variation and risk of hepatocellular carcinoma. Gut. 2008;57:91–97. doi: 10.1136/gut.2006.114066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuen MF, Tanaka Y, Fong DY, et al. Independent risk factors and predictive score for the development of hepatocellular carcinoma in chronic hepatitis B. J Hepatol. 2009;50:80–88. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2008.07.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan HL, Hussain M, Lok AS. Different hepatitis B virus genotypes are associated with different mutations in the core promoter and precore regions during hepatitis B e antigen seroconversion. Hepatology. 1999;29:976–984. doi: 10.1002/hep.510290352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka Y, Mukaide M, Orito E, et al. Specific mutations in enhancer II/core promoter of hepatitis B virus subgenotypes C1/C2 increase the risk of hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hepatol. 2006;45:646–653. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2006.06.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi K, Ohta Y, Kanai K, et al. Clinical implications of mutations C-to-T1653 and T-to-C/A/G1753 of hepatitis B virus genotype C genome in chronic liver disease. Arch Virol. 1999;144:1299–1308. doi: 10.1007/s007050050588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shinkai N, Tanaka Y, Ito K, et al. Influence of hepatitis B virus X and core promoter mutations on hepatocellular carcinoma among patients infected with subgenotype C2. J Clin Microbiol. 2007;45:3191–3197. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00411-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuen MF, Tanaka Y, Shinkai N, et al. Risk for hepatocellular carcinoma with respect to hepatitis B virus genotypes B/C, specific mutations of enhancer II/core promoter/precore regions and HBV DNA levels. Gut. 2008;57:98–102. doi: 10.1136/gut.2007.119859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ito K, Tanaka Y, Orito E, et al. T1653 mutation in the box alpha increases the risk of hepatocellular carcinoma in patients with chronic hepatitis B virus genotype C infection. Clin Infect Dis. 2006;42:1–7. doi: 10.1086/498522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen CH, Hung CH, Lee CM, et al. Pre-S deletion and complex mutations of hepatitis B virus related to advanced liver disease in HBeAg-negative patients. Gastroenterology. 2007;133:1466–1474. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma NF, Lau SH, Hu L, et al. COOH-terminal truncated HBV X protein plays key role in hepatocarcinogenesis. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14:5061–5068. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-5082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tu H, Bonura C, Giannini C, et al. Biological impact of natural COOH-terminal deletions of hepatitis B virus X protein in hepatocellular carcinoma tissues. Cancer Res. 2001;61:7803–7810. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sirma H, Giannini C, Poussin K, Paterlini P, Kremsdorf D, Brechot C. Hepatitis B virus X mutants, present in hepatocellular carcinoma tissue abrogate both the antiproliferative and transactivation effects of HBx. Oncogene. 1999;18:4848–4859. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1202867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwun HJ, Jang KL. Natural variants of hepatitis B virus X protein have differential effects on the expression of cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor p21 gene. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:2202–2213. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang Y, Tong S, Tai AW, Hussain M, Lok AS. Hepatitis B virus core promoter mutations contribute to hepatocarcinogenesis by deregulating SKP2 and its target, p21. Gastroenterology. 2012;141:1412–1421. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2011.06.048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fang ZL, Sabin CA, Dong BQ, et al. Hepatitis B virus pre-S deletion mutations are a risk factor for hepatocellular carcinoma: a matched nested case-control study. J Gen Virol. 2008;89:2882–2890. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.2008/002824-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen CH, Changchien CS, Lee CM, et al. Combined mutations in pre-s/surface and core promoter/precore regions of hepatitis B virus increase the risk of hepatocellular carcinoma: a case-control study. J Infect Dis. 2008;198:1634–1642. doi: 10.1086/592990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huy TT, Ushijima H, Win KM, et al. High prevalence of hepatitis B virus pre-s mutant in countries where it is endemic and its relationship with genotype and chronicity. J Clin Microbiol. 2003;41:5449–5455. doi: 10.1128/JCM.41.12.5449-5455.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen BF, Liu CJ, Jow GM, Chen PJ, Kao JH, Chen DS. High prevalence and mapping of pre-S deletion in hepatitis B virus carriers with progressive liver diseases. Gastroenterology. 2006;130:1153–1168. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2006.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sugauchi F, Ohno T, Orito E, et al. Influence of hepatitis B virus genotypes on the development of preS deletions and advanced liver disease. J Med Virol. 2003;70:537–544. doi: 10.1002/jmv.10428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]