Abstract

The lymphocytic ionotropic purinergic P2X receptors (P2X1R-P2X7R, or P2XRs) sense ATP released during cell damage-activation, thus regulating T-cell activation. We aim to define the role of P2XRs during islet allograft rejection and to establish a novel anti-P2XRs strategy to achieve long-term islet allograft function. Our data demonstrate that P2X1R and P2X7R are induced in islet allograft-infiltrating cells, that only P2X7R is increasingly expressed during alloimmune response, and that P2X1R is augmented in both allogeneic and syngeneic transplantation. In vivo short-term P2X7R targeting (using periodate-oxidized ATP [oATP]) delays islet allograft rejection, reduces the frequency of Th1/Th17 cells, and induces hyporesponsiveness toward donor antigens. oATP-treated mice displayed preserved islet grafts with reduced Th1 transcripts. P2X7R targeting and rapamycin synergized in inducing long-term islet function in 80% of transplanted mice and resulted in reshaping of the recipient immune system. In vitro P2X7R targeting using oATP reduced T-cell activation and diminished Th1/Th17 cytokine production. Peripheral blood mononuclear cells obtained from long-term islet-transplanted patients showed an increased percentage of P2X7R+CD4+ T cells compared with controls. The beneficial effects of oATP treatment revealed a role for the purinergic system in islet allograft rejection, and the targeting of P2X7R is a novel strategy to induce long-term islet allograft function.

The current mainstay of treatment for type 1 diabetes (T1D) is insulin therapy, which has proven to be a lifesaving breakthrough. However, insulin treatment cannot fully prevent the severe complications related to the disease, including kidney failure and coronary heart disease (1,2). Successful islet transplantation cures T1D, improves glycometabolic control, reduces hypoglycemic episodes, and halts diabetes complications (3–5). Unfortunately, the rate of functioning islet allografts at 5 years is well below 20% (6), primarily, although not exclusively, due to alloreactive and autoreactive immune responses (7–9). The anti-islet immune response involves a complex interplay between pathogenic and inflammatory immune pathways, which promote rejection, and regulatory or anti-inflammatory immune pathways, which facilitate tolerance toward transplants (10–12); one such pathway is the purinergic system (13).

The purine ATP is a small molecule (14) present at high concentrations within cells and released after cell damage or death (15) and immune cell activation (16,17); it acts as a danger signal and potent chemotactic mediator (15,18). ATP is abundant at inflammation sites and is sensed by ionotropic purinergic P2X receptors (seven receptors named P2X1-P2X7, or P2XRs) (19–21). In leukocytes, P2XRs regulate cytokine production, activation, and apoptosis (thus constituting an “autocrine alerting system”) (13,22–24). In particular, P2X7R (16,21,25,26) has been linked to T-cell activation and function, serving as a signal amplification mechanism for antigen recognition (13). Recent studies have shown that ATP may be a factor that determines the fate of T cells by promoting Th17 differentiation (24), and Th17 cells have been demonstrated to be relevant in islet allograft rejection (27–29). Inhibiting P2X7R halts the delivery of ATP signals and may redirect the immune system from a Th1/Th17 profile to a more tolerogenic state (30). P2X7R inhibitors are available for human use, including periodate-oxidized ATP (oATP) and CE-224535, thereby rendering P2X7R targeting a potential path to be tested in transplantation. Of particular interest is oATP, a small Schiff-base molecule that irreversibly antagonizes P2X7R through the selective modification of lysine residues in the vicinity of the ATP-binding site (31,32). We explored the role of P2X7R in islet allograft rejection as a means of establishing an anti–P2X7R-based strategy to redirect the immune system toward a more tolerogenic profile and thus achieving stable tolerance to islet allografts.

RESEARCH DESIGN AND METHODS

Patients.

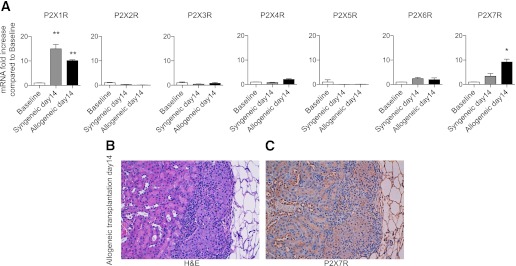

Peripheral blood mononuclear cell (PBMC) fractions were isolated by Ficoll (GE Healthcare, Piscataway, NJ) from patients with T1D (n = 8) and patients who had received allogeneic islet transplantation <3 (n = 8) or >3 (n = 8) years earlier, as well as healthy control patients (n = 8). Patient characteristics are presented in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Characteristics of islet-transplanted patients and healthy volunteers

Human islet transplantation and immunosuppression.

Islet-transplanted patients received the standard triple immunosuppressive regimen: anti-Thymoglobulin (Fresenius, Waltham, MA), followed by FK506 (target blood levels, 6–8 ng/mL; Astellas, Deerfield, IL) and/or cyclosporine (100 ng/mL; Novartis, Basel, Switzerland) and/or rapamycin (8–15 ng/mL; Pfizer, New York, NY) and/or mycophenolate (2 g/day; Roche, Basel, Switzerland) and prednisone (5–10 mg/day; Bruno Farmaceutici, Rome, Italy) (33).

Mice.

C57BL/6, BALB/c, and C57BL/6 P2X7R−/− mice were obtained from the Jackson Laboratory, Bar Harbor, Maine. All mice were cared for and used in accordance with institutional guidelines approved by the Harvard Medical School and the University of Miami Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Murine islet transplantation.

Pancreatic islets were isolated (34) and transplanted under the renal capsule of mice rendered diabetic with streptozotocin (225 mg/kg, administered i.p.; Sigma Aldrich, St. Louis, MO). Rejection was defined as blood glucose levels >250 mg/dL for 2 consecutive days.

Interventional studies.

Mice were injected intraperitoneally with 1) oATP (Medestea Srl, Turin, Italy) at 250 μg/day for 14 days, 2) rapamycin (LC Laboratories, Woburn, MA) at 0.1 mg/day for 10 days, or 3) oATP+rapamycin at the combination of 1 and 2. oATP, Benzoyl-ATP (Sigma-Aldrich), NF449 (P2X1R antagonist), and NF110 (P2X3R antagonist; Tocris, Minneapolis, MN) were used in in vitro assays. CE-224535 was provided by Pfizer.

Histology and immunohistochemistry.

Immunohistochemistry was performed on formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissue (34). Photomicrographs (original magnification ×40) were taken using an Olympus BX41 microscope (Center Valley, PA). The antibodies used were anti-CD3 (Cell Marque, Rocklin, CA), anti-FoxP3 (eBioscience, San Diego, CA), anti-insulin (Dako North America, Carpinteria, CA), anti-glucagon (Abcam, Cambridge, UK), anti-Mac2 (Euroclone, Milan, Italy), and anti-P2X7 (Alomone Laboratories, Jerusalem, Israel). Histology was evaluated by an expert pathologist.

Quantitative real-time PCR.

Total RNA was extracted from immune cells or islet grafts. For islet grafts RNA isolation, the kidney capsule was detached from the kidney, and the graft attached to the capsule was excised, thus minimizing contamination from parenchymal tissue. RNA was purified from the tissue using an RNeasy kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA), and homogenization was performed using a rotor-stator homogenizer. RNA was reverse-transcribed into cDNA using Superscript III (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). Transcripts were amplified using a 7300 Real-Time PCR System and analyzed by the ΔΔCT method, and GAPDH was used as the internal reference (35). Primers were obtained from Applied Biosystems (Foster City, CA), in particular, P2X1R (Mm00435460_m1), P2X2R (Mm01202368_g1), P2X3R (Mm00523699_m), P2X4R (Mm00501787_m1), P2X5R (Mm00473677_m1), P2X6R (Mm00440591_m1), and P2X7R (Mm00440578_m1).

Insulin and glucagon quantification.

Collected tissue was homogenized in ethanol. Islet content was extracted after two cycles of incubation with 85% phosphoric acid (Mallinckrodt, Paris, KY) at a pH of 1.8 to 2.0 (36). Supernatants were collected and stored at −80°C until assayed for insulin content by ELISA (Mercodia, Winston Salem, NC) and for glucagon by Luminex technology (Millipore, Billerica, MA).

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent spot assay.

An enzyme-linked immunosorbent spot (ELISPOT) assay was used to measure the number of cells producing interferon (INF)-γ/interleukin (IL)-4 according to the manufacturer’s protocol (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA) (37). Spots were counted using an Immunospot analyzer (Cellular Technology Ltd, Cleveland, OH).

Flow cytometry and intracellular cytokine staining.

Anti-mouse/anti-human CD3, CD4, CD45RO, CD45RA, CD8, CD25, CD44, CD62L, IL-17, annexin V, 7-amino-actinomycin D, and FoxP3 were purchased from BD Biosciences and eBioscience. Anti-P2X7R was purchased from Alomone Laboratories (38).

Mixed lymphocyte reaction.

BALB/c splenocytes were used after irradiation with 3,000 rads to stimulate C57BL/6 splenocytes at a ratio of 1:1. Proliferation was measured after 3 days following pulsing with [3H]TdR (Perkin Elmer, Wellesley, MA), and cell counts were quantified using a liquid scintillation counter.

Luminex assays.

Serum was collected from treated or control mice and analyzed using the Beadlyte Mouse Multi-Cytokine Beadmaster Kit (Millipore, Billerica, MA).

ATP level determination.

Bioluminescent detection of ATP levels was performed in serum samples using the Enliten ATP assay system (FF2000, Promega Corporation, Madison, WI).

Statistical analysis.

Data are expressed as mean ± SEM. Kaplan-Meier analysis was used for analysis of survival. When two groups were compared, a two-sided unpaired Student t test (for parametric data) or a Mann-Whitney test (for nonparametric data) was used. A P value < 0.05 (by two-tailed testing) was considered an indicator of statistical significance. Graphs were generated using GraphPad Prism 5.0 software (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA).

RESULTS

P2X7R is specifically expressed in islet allograft-infiltrating lymphocytes during the alloimmune response in vivo.

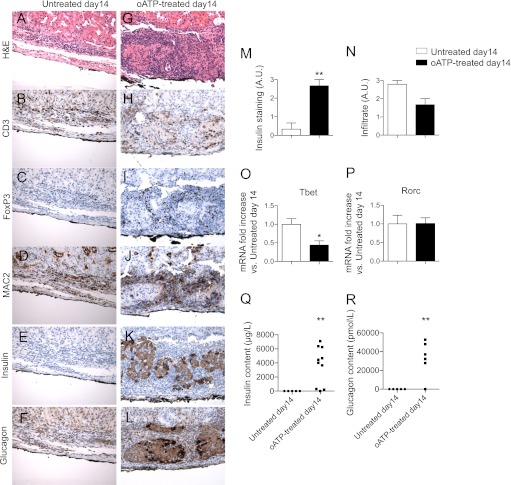

We first evaluated the expression of P2XR mRNA during the alloimmune response in vivo in an islet transplantation model. BALB/c (H-2d) islets were transplanted under the kidney capsule of C57BL/6 (H-2b) mice, rendered diabetic through streptozotocin, and islet allografts and spleens were harvested at day 14, according to the kinetics of islet allograft rejection (39). P2XR expression levels were compared with baseline values using untransplanted BALB/c islets or naïve C57BL/6 splenocytes. A significantly higher expression of P2X1R (10-fold increase vs. baseline, n = 3; P = 0.0002) and P2X7R (10-fold increase vs. baseline, n = 3; P = 0.01) was evident in the graft (Fig. 1A). No changes were observed in the expression of the remaining P2XRs in the graft (Fig. 1A) or in any P2XR in the spleen (data not shown).

FIG. 1.

Allogeneic (BALB/c) or syngeneic (C57BL/6) islets were transplanted into diabetic C57BL/6 recipient mice and harvested at day 14 after transplantation. P2XR mRNA levels were compared with untransplanted BALB/c islets (Baseline). A: Higher P2X1R expression was evident in syngeneic and allogeneic transplanted islets compared with baseline (n = 3, **P < 0.01), whereas higher expression of P2X7R was observed specifically in the allogeneic graft (n = 3; *P < 0.05). Immunohistochemical analysis showed positive staining for P2X7 in infiltrating mononuclear cells with absence of staining in islet and kidney parenchymal cells by hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) (B) and P2X7R (C).

To explore the possible effects of ischemia/reperfusion injury and peritransplant inflammation on P2XR expression levels, we evaluated P2XR expression in the setting of syngeneic islet transplantation—C57BL/6 islets into hyperglycemic C57BL/6 mice—in which the effects of the alloimmune response are absent. At day 14 after transplantation, P2X1R expression was increased in the syngeneic graft compared with baseline (14-fold increase, n = 3; P = 0.008), similarly to what we observed in allogeneic grafts (syngeneic day 14 vs. allogeneic day 14, n = 3; P = NS; Fig. 1A); these data suggest that P2X1R expression is related more to ischemia/reperfusion injury and peritransplant inflammation than to the allogeneic response. Conversely, P2X7R expression did not significantly increase in syngeneic grafts (n = 3; P = NS vs. baseline), thus suggesting that P2X7R expression is specifically increased during alloimmunity (syngeneic day 14 vs. allogeneic day 14, n = 3; P = 0.04; Fig. 1A).

We then used immunostaining to assess which cell-type was responsible for the higher expression of P2X7R observed. P2X7R-positive staining was observed in the mononuclear cell infiltrate at day 14 after transplantation, with no P2X7R expression in kidney structures or islet parenchymal cells (Fig. 1B and C). ATP levels in the serum were stable over the course of islet transplantation (data not shown).

Targeting P2X7R in vivo prolongs islet allograft survival.

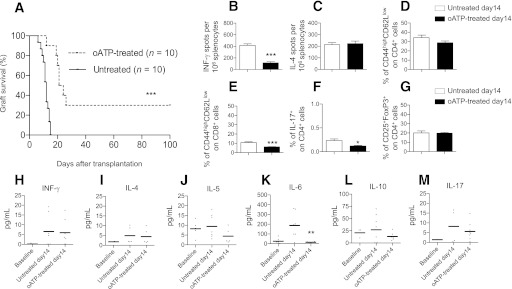

We next used oATP to test the effect of P2X7R targeting in the allogeneic islet transplantation model. oATP has been shown to irreversibly antagonize P2X7R through the selective modification of lysine residues in the vicinity of the ATP-binding site and may also exert additional immunomodulatory effects through the modulation of the other purinergic receptors (31,32). Untreated mice invariably rejected islet transplants within 14 days (mean survival time [MST] = 12 days, n = 10; Fig. 2A); conversely, mice treated daily with oATP (250 μg i.p.) for 14 days displayed a significant delay in islet rejection (MST = 22 days, n = 10; P < 0.0001 vs. untreated), and 3 of 10 mice showed long-term graft function at 100 days after transplantation (Fig. 2A).

FIG. 2.

The effect of P2X7R-targeting using oATP was tested in a model of allogeneic BALB/c islet transplantation into hyperglycemic C57BL/6 mice. A: Significant prolongation of graft survival was shown in oATP-treated compared with untreated mice (n = 10; ***P < 0.0001). Splenocytes obtained from oATP-treated mice displayed fewer numbers of cells producing IFN-γ compared with untreated mice when challenged with irradiated donor splenocytes (n = 5, ***P < 0.0001 vs. untreated at day 14) (B), whereas the number of cells producing IL-4 did not differ between the two groups (C). The percentages of CD4+ T effector (D) and Tregs were unchanged (G) at day 14 in the splenocyte population of oATP-treated islet-transplanted mice compared with untreated mice, whereas the percentages of CD8+ effector T-cells (n = 5, ***P < 0.0001 vs. untreated day 14) (E) and Th17 cells (n = 5, *P < 0.05 vs. untreated at day 14) (F) were reduced. IL-6 peripheral levels, but not levels of IFN-γ (H), IL-4 (I), IL-5 (J), IL-10 (L), or IL-17 (M), were reduced in oATP-treated mice compared with untreated mice (n = 5, **P < 0.01 vs. untreated at day 14) (K).

Targeting P2X7R in vivo reduces the severity of the alloimmune response.

We performed immune profiling of islet-transplanted oATP-treated and untreated mice at day 14 after transplantation. When splenocytes harvested from oATP-treated recipients were challenged with donor-derived splenocytes, a reduction was observed at day 14 in the number of cells producing IFN-γ (oATP-treated = 117 ± 9 vs. untreated = 418 ± 26, n = 5; P < 0.0001; Fig. 2B), with no effect on the number of cells producing IL-4 (Fig. 2C). No significant changes in the percentages of peripheral CD4+ T effector cells were observed between groups (CD44highCD62LlowCD4+ T cells; Fig. 2D). Slight reductions were evident in the percentages of CD8+ T effector cells (Fig. 2E) and of Th17 cells (Fig. 2F). No differences were observed in the percentages of regulatory T-cells (CD25+FoxP3+CD4+ T-cells, or Tregs; Fig. 2G). The cytokine profile of sera showed that IL-6, a Th17 cytokine, was reduced in oATP-treated recipients (Fig. 2K), whereas only minor changes were observed for all other cytokines examined (Fig. 2H–J, L and M).

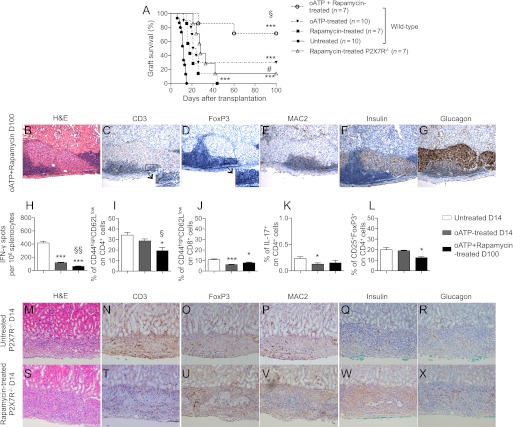

Targeting P2X7R in vivo reduces infiltration and Th1 transcripts in islet allografts.

We next analyzed the pathology of islet allografts 14 days after transplantation. Islet structure was substantially compromised, and insulin or glucagon staining were undetectable in untreated mice (Fig. 3A, E and F, respectively), with diffuse infiltration primarily constituted by CD3+ T cells and MAC2+ macrophages, with very few FoxP3+ cells (Fig. 3A–D). Conversely, islet structure and insulin and glucagon staining were maintained in oATP-treated mice (Fig. 3G, K and L, respectively), with infiltrate mainly confined to the islet borders with several FoxP3+ cells (Fig. 3G–J). Semiquantitative analysis confirmed preserved insulin staining at day 14 in oATP-treated mice but not in the untreated mice (Fig. 3M), with no major differences in the overall infiltrate (Fig. 3N). A reduction in the mRNA expression of Tbet, a marker of the Th1 immune response (threefold decrease, n = 3; P = 0.02 vs. untreated; Fig. 3O), but not in Rorc, a marker of the Th17 immune response (Fig. 3P), was observed in the graft infiltrate of oATP-treated mice. Further analysis of the insulin and glucagon content in the transplanted islets confirmed the graft protection conferred by oATP treatment at day 14 (insulin content: untreated = 2.3 ± 0.4 μg/L vs. oATP-treated = 3,698 ± 843 μg/L, n = 5 and 10; P = 0.009; Fig. 3Q; glucagon content: untreated = undetectable vs. oATP-treated = 32,999 ± 18,657 pmol/L, n = 5 and 6; P = 0.007; Fig. 3R).

FIG. 3.

Histological analysis of islet allografts at day 14 after transplantation in untreated mice (hyperglycemic) revealed complete destruction of the graft parenchyma (A) and absent insulin (E) and glucagon (F) staining, with diffuse infiltration primarily constituted by CD3+ (B) and MAC2+ (D) cells, with very few FoxP3+ cells (C); conversely in oATP-treated mice (normoglycemic), islet allograft structure (G), and insulin (K) and glucagon (L) staining were preserved, with mild infiltrate mainly confined to the islet borders (H, J) with several FoxP3+ cells (I) (representative of different mice). Semi-quantification of insulin staining confirmed enhanced preservation of islet allografts in oATP-treated mice (n = 5, **P < 0.01 vs. untreated at day 14) (M), with no significant differences in cell infiltrate (N). A reduction in Tbet (n = 3, *P < 0.05 vs. untreated at day 14) (O), but not of Rorc transcripts (P), was evident in islet allografts obtained from oATP-treated islet-transplanted mice compared with untreated mice. Insulin (n = 5 for untreated and n = 10 for oATP-treated; **P < 0.01) (Q) and glucagon content (n = 5 for untreated and n = 6 for oATP-treated; **P < 0.01) (R) resulted higher in transplanted islets harvested from oATP-treated compared with untreated recipients.

Targeting P2X7R in vitro reduces the severity of the alloimmune response.

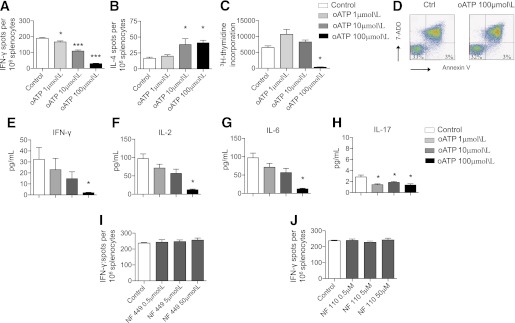

To confirm the data we obtained in vivo, we evaluated the effect of targeting P2X7R in vitro using alloimmune-relevant assays. Responder splenocytes from C57BL/6 mice were challenged with irradiated stimulator splenocytes from BALB/c mice. The numbers of cells producing IFN-γ and IL-4 were evaluated in an ELISPOT assay in the presence of increasing concentrations of oATP. P2X7R targeting robustly inhibited IFN-γ production (cells producing IFN-γ: oATP 100 μmol/L = 30 ± 2 vs. control = 190 ± 4, n = 5; P < 0.0001; Fig. 4A), but a dose-dependent increase in IL-4 production was observed (Fig. 4B). To confirm in vitro suppression of the alloantigen response, we performed a mixed leukocyte reaction experiment in which alloantigen-mediated cell proliferation appeared to be suppressed (number of proliferating cells as measured by 3H-thymidine incorporation: oATP 100 μmol/L = 136 ± 5 vs. control = 6,199 ± 498, n = 5; P < 0.0001; Fig. 4C). C57BL/6 splenocytes were also challenged with allogeneic cells in the presence of oATP (100 μmol/L) for 24 h, and apoptosis was assessed by fluorescence-activated cell sorter as the percentage of annexin V+7AAD− cells; no increase in the percentage of apoptotic cells was detected (Fig. 4D).

FIG. 4.

The effect of P2X7R targeting with oATP was tested in vitro. In an ELISPOT assay in which C57BL/6 splenocytes were challenged in vitro with irradiated BALB/c splenocytes (Control), oATP treatment greatly reduced the number of cells producing IFN-γ (n = 5, *P < 0.05, ***P < 0.0001 vs. Control) (A), as well as increased the number of cells producing IL-4 (n = 5, *P < 0.05 vs. Control) (B). C: oATP also inhibited the proliferation of C57BL/6 splenocytes challenged with irradiated BALB/c splenocytes measured as incorporation of 3H-thymidine (n = 5, ***P < 0.0001 vs. Control). D: No significant differences in the percentages of apoptotic cells (AnnexinV+7-ADD– cells) were evident in controls compared with oATP-cultured splenocytes (representative of three different experiments). Luminex analysis of the supernatant showed reduced IFN-γ (E), IL-2 (F), IL-6 (G), and IL-17 (H) production in C57BL/6 splenocytes challenged with irradiated BALB/c splenocytes (n = 5, *P < 0.05 vs. Control). Conversely, targeting of P2X1R using the specific inhibitor NF 449 (I) or targeting of P2X3R using the specific inhibitor NF 110 (J) was unable to modulate IFN-γ production by C57BL/6 splenocytes challenged in an ELISPOT assay with irradiated BALB/c splenocytes. (A high-quality color representation of this figure is available in the online issue.)

We then tested the effect of increasing doses of oATP on Th1/Th17 cytokine levels. A dose-dependent response was evident, in which oATP reduced the number of cells producing Th1 cytokines (IFN-γ and IL-2) and Th17 cytokines (IL-6 and IL-17; Fig. 4E–H). Because it has been reported that oATP may affect other P2XRs, we made use of the availability of the selective P2X1R inhibitor NF 449 and of the selective P2X3R inhibitor NF 110. C57BL/6 splenocytes were stimulated with irradiated BALB/c splenocytes, and IFN-γ production was evaluated in the presence of these inhibitors. P2X1R and P2X3R inhibition failed to modulate alloantigen-mediated IFN-γ production (Fig. 4I and J); these data confirmed the marginal role of P2X1R and P2X3R in the alloimmune response, at least in vitro.

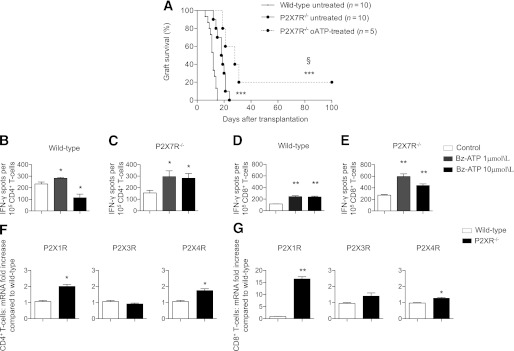

Genetic targeting of P2X7R slightly prolongs islet graft survival.

We also determined the effect of genetic targeting of P2X7R on islet graft survival. P2X7R−/− C57BL6 mice were transplanted with allogeneic BALB/c islets, and partial prolongation of graft survival was observed compared with wild-type recipients (MST: P2X7R−/− = 19 days, n = 10; P < 0.0001 vs. wild-type; Fig. 5A). oATP treatment on P2X7R−/− recipients was able to further prolong graft survival (MST: oATP-treated P2X7R−/− = 26 days, n = 5; P = 0.04 vs. untreated P2X7R−/−; Fig. 5A). To investigate the purinergic system function in P2X7R−/− mice, we analyzed the effect of benzoyl-ATP (Bz-ATP), a synthetic agonist of the purinergic receptors, in CD4+ and CD8+ T cells. When 1 μmol/L Bz-ATP was added to the cultured cells, IFN-γ production increased in CD4+ (Fig. 5B) and CD8+ T cells (Fig. 5D) isolated from wild-type mice. Bz-ATP similarly stimulated IFN-γ production from CD4+ (Fig. 5C) and CD8+ T cells (Fig. 5E) isolated from P2X7R−/− mice. We hypothesized that compensatory mechanisms may have arisen in P2X7R−/− mice, and in particular, we investigated a possible upregulation of P2X1R, P2X3R, and P2X4R, which also have been associated with the immune response (25). CD4+ and CD8+ T cells were extracted from wild-type and P2X7R−/− mice, and the relative expression of P2XRs was assessed by real-time PCR. Higher levels of P2X1R and P2X4R were found in P2X7R−/−-derived CD4+ T cells (P2X1R: 2-fold increase vs. wild-type, n = 3, P = 0.02; P2X4R: 1.7-fold increase vs. wild-type, n = 3, P = 0.03; Fig. 5F) and CD8+ T cells (P2X1R: 16-fold increase vs. wild-type, n = 3, P = 0.003; P2X4R: 1.3-fold increase vs. wild-type, n = 3, P = 0.04; Fig. 5G). Promotion of islet graft survival obtained by oATP treatment also in P2X7R−/− recipients demonstrates that the targeting of other purinergic receptors may contribute to the immunomodulatory effects of oATP; however, some caution should be used when analyzing data obtained from P2X7R−/− mice because compensatory mechanisms in the purinergic system are present.

FIG. 5.

A: A significant prolongation of islet allograft survival was shown in P2X7R−/− C57BL/6 recipients of allogeneic BALB/c islets compared with wild-type recipients (n = 10, ***P < 0.0001 vs. wild-type untreated), and oATP treatment prolonged islet graft survival in P2X7R−/− recipients (n = 5, §P < 0.05 vs. P2X7R−/− untreated; ***P < 0.0001 vs. wild-type untreated). CD4+ and CD8+ T cells purified from splenocytes of wild-type (B and D, respectively) or P2X7R−/− (C and E, respectively) C57BL/6 mice were challenged with anti-CD3 Ig and anti-CD28 Ig in the presence or absence of different concentrations of Bz-ATP and were tested for IFN-γ production in an ELISPOT assay. A preserved and efficient Bz-ATP response, despite the absence of P2X7R, was evident in P2X7R−/− mice (C and E) and in wild-type mice (B and D) (n = 5, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 vs. Control). CD4+ T cells and CD8+ T cells were extracted from wild-type and P2X7R−/− mice and were assessed for P2XRs expression. Higher levels of P2X1R and P2X4R were observed in P2X7R−/− CD4+ (F) and CD8+ (G) T cells (n = 3, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 vs. wild-type) compared with wild-type.

Rapamycin and P2XR7 targeting in vivo synergize in reducing the alloimmune response.

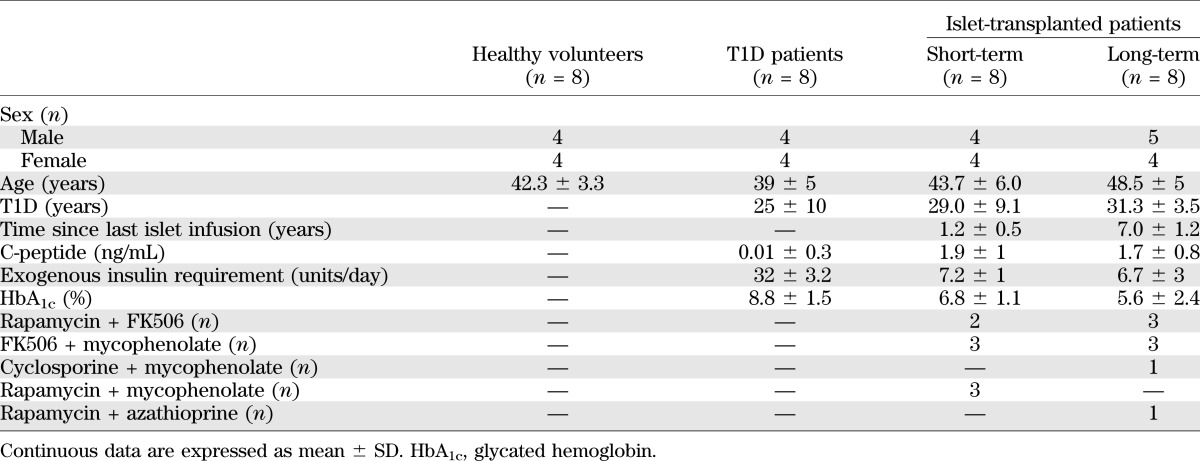

To evaluate a potential clinically relevant protocol, we tested oATP combined with a clinical-grade dose of rapamycin (oATP at 250 μg day 0 through day 15 + rapamycin at 0.1 mg/kg day 0 through day 10); five of seven islet-transplanted mice treated with oATP+rapamycin showed long-term graft function at 100 days after transplantation (MST: rapamycin = 18; oATP+rapamycin = indefinite, n = 7; oATP+rapamycin vs. both untreated and rapamycin, P < 0.0001; oATP+rapamycin vs. oATP, P = 0.04; Fig. 6A). Rapamycin was more effective in prolonging islet graft survival in P2X7R−/− compared with wild-type recipients (n = 7; P = 0.04 vs. rapamycin in wild-type; Fig. 6A), confirming the synergistic effect between P2X7R-targeting and rapamycin. Better protection of islet grafts was observed in wild-type recipients treated with oATP+rapamycin than in P2X7R−/− recipients treated with rapamycin alone (Fig. 6A), indicating that the oATP may also target other purinergic receptors. Pathology of islet allografts in long-term protected islet-transplanted oATP+rapamycin-treated mice revealed preserved architecture (Fig. 6B) and maintained insulin (Fig. 6F) and glucagon (Fig. 6G) staining. Islet infiltrate was evident but appeared confined to the border of islet allografts (Figs. 6C and E) At higher magnifications, FoxP3+ cells infiltrate appeared nearly as abundant as the CD3+ T-cell infiltrate, suggesting a high proportion of Tregs (Fig. 6C and D, high-magnification insert). Mice treated with short-course oATP+rapamycin were further protected from the alloimmune response, as demonstrated by a decrease in the responsiveness toward donor alloantigen and measured by the reduction in cells producing IFN-γ during ex vivo challenge with alloantigens (cells producing IFN-γ: oATP+rapamycin-treated at day 100 = 60 ± 8 vs. untreated at day 14, n = 3, P < 0.0001; vs. oATP-treated at day 14, n = 3, P = 0.008; Fig. 6H). A parallel reduction in the percentage of CD4+ and CD8+ effector cells was observed in oATP+rapamycin-treated mice. The percentages of peripheral CD4+ effector T cells (Fig. 6I) and CD8+ effector T cells (Fig. 6J) were greatly reduced compared with those observed in oATP-treated mice at day 14. Stable levels of Th17 cells (Fig. 6K) and a slight decrease in the number of Tregs were observed in oATP+rapamycin-treated mice (Fig. 6L). A better protection of the islet graft structure was observed in rapamycin-treated P2X7R−/− (Fig. 6S, W, and X) compared with untreated P2X7R−/− recipients (Fig. 6M, Q, and R) at day 14 after transplantation. Immune cell infiltration was reduced in rapamycin-treated P2X7R−/− recipients (Fig. 6T, U, and V) compared with untreated P2X7R−/− recipients (Fig. 6N, O, and P).

FIG. 6.

A: In a clinically relevant combination, low-dose rapamycin treatment significantly prolonged islet graft survival and synergized with oATP treatment in promoting long-term islet graft survival in BALB/c islet allografts transplanted into hyperglycemic C57BL/6 mice (***P < 0.0001 vs. untreated: §P < 0.05 vs. oATP-treated and rapamycin), and rapamycin was more effective in prolonging graft survival in P2X7R−/− than in wild-type recipients (n = 7; #P < 0.05 vs. rapamycin-treated wild-type). Histological analysis of graft islets at day 100 after transplantation in oATP+rapamycin-treated mice revealed preserved islet structure (B) and insulin (F) and glucagon production (G) with mild extraislet T-cell (C) and macrophage infiltration (E) as well as substantial Treg numbers (D). Splenocytes obtained from oATP+rapamycin-treated islet-transplanted mice at day 100 displayed a lower number of cells producing IFN-γ compared with untreated or oATP-treated mice at day 14 when challenged with irradiated donor splenocytes (n = 3, ***P < 0.0001 vs. untreated; §§P < 0.01 vs. oATP-treated) (H). The percentages of CD4+ effector T cells at day 14 (n = 3, *P < 0.05 vs. untreated; §P < 0.05 vs. oATP-treated) (I) and CD8+ effector T cells at day 14 (n = 3, *P < 0.05, ***P < 0.0001 vs. untreated) (J) were also reduced. No differences in the number of Th17 cells were observed at day 14 (n = 3, *P < 0.05 vs. untreated) (K), whereas a slight reduction was seen in the percentage of Tregs (n = 3, *P < 0.05 vs. untreated) (L) when rapamycin was added to the treatment protocol. A better protection of the islet graft structure was observed in rapamycin-treated P2X7R−/− (S, W, and X) compared with untreated P2X7R−/− recipients (M, Q, and R) at day 14 after transplantation. Immune cell infiltration was reduced in rapamycin-treated P2X7R−/− recipients (T, U, and V) compared with untreated P2X7R−/− recipients (N, O, and P). H&E, hematoxylin and eosin.

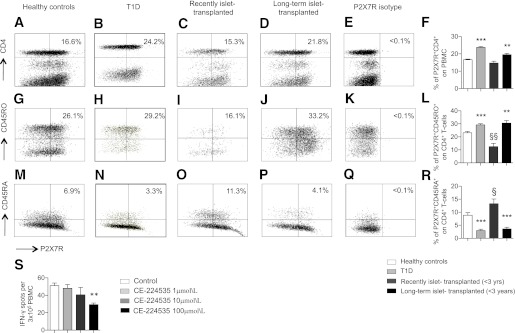

P2X7R expression is increased in CD4+ T cells obtained from islet-transplanted patients.

We then sought to determine the P2X7R expression profile in lymphocytes obtained from islet-transplanted patients to determine the relevance of the P2X7R/ATP system in human T cells and, potentially, in islet rejection in humans. PBMCs from islet-transplanted patients, T1D patients, and healthy control subjects were harvested, and CD4+ T cells, a key population in islet rejection, were analyzed by flow cytometry (Table 1). In healthy controls, the P2X7R+CD4+ T-cell population represented 17% of all PBMCs (Figs. 7A and F), and P2X7R was expressed in almost 50% of peripheral CD4+ T cells (data not shown). The percentage of P2X7R+CD4+ T cells observed in recently well-functioning transplanted patients (<3 years from last islet infusion) were comparable to those of healthy control subjects (Fig. 7A, C, and F). Conversely, the frequency of the P2X7R+CD4+ T-cell population significantly increased in long-term islet-transplanted patients (>3 years; Fig. 7A, D, and F) and in T1D patients (Figs 7A, B, and F). Among CD4+ T cells, an expansion of P2X7R+CD45RO+ cells (T cells with a mature phenotype or memory T cells) was observed in long-term islet-transplanted patients (Fig. 7G, J, and L) and in T1D patients (Fig. 7G, H, and L) compared with healthy control subjects. Conversely, a reduction in naïve P2X7R+CD45RA+ cells (Fig. 7M, N, P, and R) was observed. These data demonstrate a similar P2X7R expression pattern on CD4+ T cells in long-term islet-transplanted patients and in T1D patients, whereas a different pattern is expressed on recently islet-transplanted patients and healthy control subjects.

FIG. 7.

PBMCs from healthy control subjects, T1D patients, and islet-transplanted patients were harvested and analyzed by flow cytometry for P2X7 expression. A higher percentage of P2X7+CD4+ T cells was evident in T1D patients and in long-term islet-transplanted patients (>3 years, n = 8) compared with recently islet-transplanted (<3 years, n = 8) or healthy control subjects (n = 8; **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.0001 vs. healthy controls and recently islet-transplanted patients) (A, B, C, D, and F). Within the CD4+ T-cell population, an increase in the percentage of memory P2X7R+CD45RO+ cells was observed in T1D patients and in long-term islet-transplanted patients (**P < 0.01, ***P < 0.0001 vs. healthy controls and recently islet-transplanted; §§P < 0.01 vs. healthy controls) (G, H, I, J, and L). Conversely, a reduction in the percentage of naïve P2X7R+CD45RA+ cells was observed in T1D patients and in long-term islet-transplanted patients (***P < 0.0001 vs. healthy controls and recently islet-transplanted; §P < 0.05 vs. healthy volunteers) (M, N, O, P, R). S: The targeting of P2X7R using the specific human inhibitor CE-224535 in an ELISPOT assay in which human PBMCs were challenged with allogeneic human PBMC reduced the number of cells producing IFN-γ (n = 5, **P < 0.01 vs. control).

The specific human P2X7R antagonist CE-224535 inhibits the alloimmune response in vitro.

To confirm the immunomodulatory effect of P2X7R inhibition, we challenged PBMCs obtained from healthy control subjects with allogeneic irradiated PBMCs obtained from different donors in an ELISPOT assay in the presence of different concentrations of the human-specific P2X7R antagonist CE-224535, which has been investigated in clinical trials for rheumatoid arthritis. A reduction in the number cells producing IFN-γ was observed with CE-224535 treatment at 100 μmol/L (29 ± 1 vs. control 51 ± 3, n = 5, P = 0.003; Fig. 7S).

DISCUSSION

Successful islet transplantation can improve metabolic control and can reestablish normoglycemia in subjects with T1D (3). Unfortunately, transplanted islets are subjected to the damaging effects of the alloimmune response and the recurrence of autoimmunity (20% of the patients insulin-free at 5 years) (3,7,8,40). The better outcomes of autologous islet transplantation from patients with chronic pancreatitis (47% insulin-free at 5 years) (41), in whom the allo- and autoimmune responses are absent, confirms the primary role of immune response in islet graft failure, although multiple factors are ultimately responsible for islet graft loss (3). Considering the potential advantages of islet transplantation in diabetes complications and the relatively low invasiveness of the procedure, additional research is required to develop novel strategies to lessen the need for lifelong immunosuppression (42).

We studied the role of the ionotropic purinergic P2X receptors in islet allograft rejection, particularly in light of recent studies that have demonstrated roles for the ATP/P2XR system in T-cell activation and in Th1/Th17-cell generation (24–26). P2X7R may represent a crossroads for naïve T cells to become activated during the alloimmune response. Our data show that the expression of P2X1R and P2X7R is higher in the islet allograft during rejection, whereas in the syngeneic setting, only P2X1R has higher expression. These data seem to link P2X7R expression specifically to the alloimmune response, whereas P2X1R expression appears to be more related to ischemia/reperfusion and peritransplant inflammation.

In our model of islet allotransplantation, P2X7R targeting with oATP was able to promote long-term graft function in 30% of recipients, and this effect was associated with an extensive reshaping of the immune system, specifically in a reduction of the anti-islet Th1 response, a reduction in CD4+ T effector and Th17 cells, which are well known to promote the alloimmune response (29), and a preservation of Tregs, which, on the contrary, promote graft acceptance (43). Of particular interest in the clinical setting is the synergistic effect observed between rapamycin, which is a pivotal drug in clinical islet transplantation (44), and oATP. This combination treatment resulted in a preponderance of islet-transplanted mice accepting a fully major histocompatibility complex–mismatched allograft long-term, with hyporesponsiveness toward alloantigen and preservation of islet graft morphology and insulin staining.

Although oATP is described as one of the most effective P2X7R inhibitors in vivo (45,46), the targeting of P2X7R with oATP has also been associated with the targeting of other purinergic receptors (22). Our data in P2X7R−/− recipients confirmed the presence of additional targets for oATP, and this targeting appears beneficial in the context of allogeneic islet transplantation providing additional immunomodulation. In particular, our data suggest that the effect could be mediated by P2X1R targeting, which is upregulated in the syngeneic and allogeneic graft and in the CD4+ and CD8+ T cells obtained from P2X7R−/− mice. However, some caution should be used during analysis of data using P2X7R−/− recipients; in these mice, the immunological function of the other P2XRs may in fact become more relevant, as suggested by the preserved response to Bz-ATP in P2X7R−/−-derived lymphocytes, accompanied by the upregulation of other P2XRs. Further development of specific antagonists for the different P2XRs suitable for in vivo use (22,46) will help us to better dissect the relative contribution of the targeting various P2XRs in islet graft rejection.

In vitro, the targeting of P2X7R with oATP during allostimulation inhibited the production of Th1/Th17 cytokines and T-cell activation, confirming that P2X7R signaling is required to trigger the Th1/Th17 immune response (21,25); on the contrary, the expansion of Tregs is not evident in our model, although this has been reported in other settings (30).

By studying PBMCs obtained from different populations of human subjects, we were able to evaluate the expression of P2X7R in different lymphocyte subsets The P2X7R+CD4+ T-cell population appeared to be upregulated in T1D patients and islet-transplanted patients in the long-term, suggesting a link between activation of the immune system, the anti-islet response, and expression of P2X7R. Interestingly, an increase in memory and decrease of naïve CD4+ T-cells expressing P2X7R was observed in long-term islet-transplanted recipients. Considering that progressive loss of islet graft function may be associated with a mounting of memory allo- and autoimmune cell responses (40,47), identifying potential new targets for the memory-cell subpopulation is highly desirable. In this sense, the targeting of P2X7R may represent a viable option, particularly in light of the availability of clinical-grade therapeutics, such as the human-specific inhibitor CE-224535.

In conclusion, P2X7R-mediated alloimmunity is an important pathway in the alloimmune response that contributes to priming of Th1/Th17 effector cells. Targeting of P2X7R may thus be beneficial in preventing islet allograft rejection and inducing tolerance, thereby reducing the need for immunosuppressive agents. Indeed, complete tolerance induction may require a specific P2X7R-targeting approach to abrogate Th1/Th17 alloimmunity and to facilitate a Treg sparing/expansion strategy. In view of the novel anti-P2X7R inhibitors available for clinical use (e.g., CE-224535, AZD9056, and GSK1482160), our data may have significant clinical relevance for the field of islet transplantation.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

P.F. is the recipient of a Juvenile Diabetes Research Foundation Career Development Award, an American Society of Nephrology Career Development Award, and an American Diabetes Association (ADA) mentor-based fellowship. P.F. is supported by a Translational Research Program grant from Boston Children's Hospital. P.F. and A.V. are recipients of a Ministry of Health of Italy (“Staminali” RF-FSR-2008-1213704). A.V. is supported by a National Institutes of Health Research Training Grant to Boston Children's Hospital in Pediatric Nephrology (T32DK-007726-28). The studies performed in Miami were supported by the Diabetes Research Institute Foundation and Converge Biotech Inc. to C.R. and A.P. R.B. is supported by an ADA mentor-based fellowship to P.F. No other potential conflicts of interest relevant to this article were reported.

A.V. conducted this study as partial fulfillment of his PhD in Molecular Medicine, San Raffaele University, Milan, Italy.

A.V. designed and performed research, analyzed data, and wrote the paper. C.F. performed research, analyzed data, and wrote the paper. F.D., S.T., M.P., F.Ga., M.C., R.B., R.D.M., D.C., R.G., M.E.F., A.S., and P.M. performed research. F.Gr. edited the paper. C.R. designed research and edited the paper. M.H.S. designed research. A.P. and P.F. designed research and wrote and edited the paper. P.F. is the guarantor of this work and, as such, had full access to all the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

The authors are grateful to Medestea for providing clinical grade oATP and to Pfizer for providing CE-224535. The authors thank Rita Nano (Islet Processing Facility, San Raffaele Scientific Institute, Milan, Italy) for performing human islet isolation, Gabriella Becchi (Department of Biomedical, Biotechnological, and Translational Sciences, Section of Pathology, University of Parma, Italy), Maria Nicastro (Department of Clinical Sciences, University of Parma, Italy) for technical assistance in immunofluorescence methods, and the Diabetes Research Institute’s Cores (Preclinical Cell Processing and Translational Model, Flow Cytometry, and Imaging) at the University of Miami for technical assistance.

Footnotes

See accompanying commentary, p. 1394.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bloomgarden ZT. Diabetes complications. Diabetes Care 2004;27:1506–1514 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bloomgarden ZT. Consequences of diabetes: cardiovascular disease. Diabetes Care 2004;27:1825–1831 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fiorina P, Shapiro AM, Ricordi C, Secchi A. The clinical impact of islet transplantation. Am J Transplant 2008;8:1990–1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Venturini M, Fiorina P, Maffi P, et al. Early increase of retinal arterial and venous blood flow velocities at color Doppler imaging in brittle type 1 diabetes after islet transplant alone. Transplantation 2006;81:1274–1277 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vantyghem MC, Kerr-Conte J, Arnalsteen L, et al. Primary graft function, metabolic control, and graft survival after islet transplantation. Diabetes Care 2009;32:1473–1478 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shapiro AM, Ricordi C, Hering BJ, et al. International trial of the Edmonton protocol for islet transplantation. N Engl J Med 2006;355:1318–1330 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Makhlouf L, Kishimoto K, Smith RN, et al. The role of autoimmunity in islet allograft destruction: major histocompatibility complex class II matching is necessary for autoimmune destruction of allogeneic islet transplants after T-cell costimulatory blockade. Diabetes 2002;51:3202–3210 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ricordi C, Strom TB. Clinical islet transplantation: advances and immunological challenges. Nat Rev Immunol 2004;4:259–268 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bosi E, Braghi S, Maffi P, et al. Autoantibody response to islet transplantation in type 1 diabetes. Diabetes 2001;50:2464–2471 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rothstein DM, Sayegh MH. T-cell costimulatory pathways in allograft rejection and tolerance. Immunol Rev 2003;196:85–108 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Murphy SP, Porrett PM, Turka LA. Innate immunity in transplant tolerance and rejection. Immunol Rev 2011;241:39–48 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shen X, Reng F, Gao F, et al. Alloimmune activation enhances innate tissue inflammation/injury in a mouse model of liver ischemia/reperfusion injury. Am J Transplant 2010;10:1729–1737 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Junger WG. Immune cell regulation by autocrine purinergic signalling. Nat Rev Immunol 2011;11:201–212 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Novak I. ATP as a signaling molecule: the exocrine focus. News Physiol Sci 2003;18:12–17 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Elliott MR, Chekeni FB, Trampont PC, et al. Nucleotides released by apoptotic cells act as a find-me signal to promote phagocytic clearance. Nature 2009;461:282–286 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schenk U, Westendorf AM, Radaelli E, et al. Purinergic control of T cell activation by ATP released through pannexin-1 hemichannels. Sci Signal 2008;1:ra6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Piccini A, Carta S, Tassi S, Lasiglié D, Fossati G, Rubartelli A. ATP is released by monocytes stimulated with pathogen-sensing receptor ligands and induces IL-1beta and IL-18 secretion in an autocrine way. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2008;105:8067–8072 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Homolya L, Steinberg TH, Boucher RC. Cell to cell communication in response to mechanical stress via bilateral release of ATP and UTP in polarized epithelia. J Cell Biol 2000;150:1349–1360 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ralevic V, Burnstock G. Receptors for purines and pyrimidines. Pharmacol Rev 1998;50:413–492 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Khakh BS, North RA. P2X receptors as cell-surface ATP sensors in health and disease. Nature 2006;442:527–532 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wilhelm K, Ganesan J, Müller T, et al. Graft-versus-host disease is enhanced by extracellular ATP activating P2X7R. Nat Med 2010;16:1434–1438 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Casati A, Frascoli M, Traggiai E, Proietti M, Schenk U, Grassi F. Cell-autonomous regulation of hematopoietic stem cell cycling activity by ATP. Cell Death Differ 2011;18:396–404 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gabel CA. P2 purinergic receptor modulation of cytokine production. Purinergic Signal 2007;3:27–38 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Atarashi K, Nishimura J, Shima T, et al. ATP drives lamina propria T(H)17 cell differentiation. Nature 2008;455:808–812 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yip L, Woehrle T, Corriden R, et al. Autocrine regulation of T-cell activation by ATP release and P2X7 receptors. FASEB J 2009;23:1685–1693 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ferrari D, Pizzirani C, Adinolfi E, et al. The P2X7 receptor: a key player in IL-1 processing and release. J Immunol 2006;176:3877–3883 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Emamaullee JA, Davis J, Merani S, et al. Inhibition of Th17 cells regulates autoimmune diabetes in NOD mice. Diabetes 2009;58:1302–1311 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yuan X, Paez-Cortez J, Schmitt-Knosalla I, et al. A novel role of CD4 Th17 cells in mediating cardiac allograft rejection and vasculopathy. J Exp Med 2008;205:3133–3144 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chadha R, Heidt S, Jones ND, Wood KJ. Th17: contributors to allograft rejection and a barrier to the induction of transplantation tolerance? Transplantation 2011;91:939–945 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schenk U, Frascoli M, Proietti M, et al. ATP inhibits the generation and function of regulatory T cells through the activation of purinergic P2X receptors. Sci Signal 2011;4:ra12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Murgia M, Hanau S, Pizzo P, Rippa M, Di Virgilio F. Oxidized ATP. An irreversible inhibitor of the macrophage purinergic P2Z receptor. J Biol Chem 1993;268:8199–8203 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rizzo R, Ferrari D, Melchiorri L, et al. Extracellular ATP acting at the P2X7 receptor inhibits secretion of soluble HLA-G from human monocytes. J Immunol 2009;183:4302–4311 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fiorina P, Folli F, Maffi P, et al. Islet transplantation improves vascular diabetic complications in patients with diabetes who underwent kidney transplantation: a comparison between kidney-pancreas and kidney-alone transplantation. Transplantation 2003;75:1296–1301 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Vergani A, D’Addio F, Jurewicz M, et al. A novel clinically relevant strategy to abrogate autoimmunity and regulate alloimmunity in NOD mice. Diabetes 2010;59:2253–2264 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Vergani A, Clissi B, Sanvito F, Doglioni C, Fiorina P, Pardi R. Laser capture microdissection as a new tool to assess graft-infiltrating lymphocytes gene profile in islet transplantation. Cell Transplant 2009;18:827–832 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zahr E, Molano RD, Pileggi A, et al. Rapamycin impairs in vivo proliferation of islet beta-cells. Transplantation 2007;84:1576–1583 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Petrelli A, Carvello M, Vergani A, et al. IL-21 is an antitolerogenic cytokine of the late-phase alloimmune response. Diabetes 2011;60:3223–3234 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Carvello M, Petrelli A, Vergani A, et al. Inotuzumab ozogamicin murine analog-mediated B-cell depletion reduces anti-islet allo- and autoimmune responses. Diabetes 2012;61:155–165 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fiorina P, Jurewicz M, Tanaka K, et al. Characterization of donor dendritic cells and enhancement of dendritic cell efflux with CC-chemokine ligand 21: a novel strategy to prolong islet allograft survival. Diabetes 2007;56:912–920 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Fiorina P, Vergani A, Petrelli A, et al. Metabolic and immunological features of the failing islet-transplanted patient. Diabetes Care 2008;31:436–438 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sutherland DE, Gruessner AC, Carlson AM, et al. Islet autotransplant outcomes after total pancreatectomy: a contrast to islet allograft outcomes. Transplantation 2008;86:1799–1802 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Oberholzer J, Toso C, Ris F, et al. Beta cell replacement for the treatment of diabetes. Ann N Y Acad Sci 2001;944:373–387 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Shi Q, Lees JR, Scott DW, Farber DL, Bartlett ST. Endogenous expansion of regulatory T cells leads to long-term islet graft survival in diabetic NOD mice. Am J Transplant 2012;12:1124–1132 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Shapiro AM, Lakey JR, Ryan EA, et al. Islet transplantation in seven patients with type 1 diabetes mellitus using a glucocorticoid-free immunosuppressive regimen. N Engl J Med 2000;343:230–238 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gulbransen BD, Bashashati M, Hirota SA, et al. Activation of neuronal P2X7 receptor-pannexin-1 mediates death of enteric neurons during colitis. Nat Med 2012;18:600–604 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Arulkumaran N, Unwin RJ, Tam FW. A potential therapeutic role for P2X7 receptor (P2X7R) antagonists in the treatment of inflammatory diseases. Expert Opin Investig Drugs 2011;20:897–915 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Monti P, Scirpoli M, Maffi P, et al. Islet transplantation in patients with autoimmune diabetes induces homeostatic cytokines that expand autoreactive memory T cells. J Clin Invest 2008;118:1806–1814 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]