Abstract

Pharmaceuticals have emerged as a major group of environmental contaminants over the past decade but relatively little is known about their occurrence in freshwaters compared to other pollutants. We present a global-scale analysis of the presence of 203 pharmaceuticals across 41 countries and show that contamination is extensive due to widespread consumption and subsequent disposal to rivers. There are clear regional biases in current understanding with little work outside North America, Europe, and China, and no work within Africa. Within individual countries, research is biased around a small number of populated provinces/states and the majority of research effort has focused upon just 14 compounds. Most research has adopted sampling techniques that are unlikely to provide reliable and representative data. This analysis highlights locations where concentrations of antibiotics, cardiovascular drugs, painkillers, contrast media, and antiepileptic drugs have been recorded well above thresholds known to cause toxic effects in aquatic biota. Studies of pharmaceutical occurrence and effects need to be seen as a global research priority due to increasing consumption, particularly among societies with aging populations. Researchers in all fields of environmental management need to work together more effectively to identify high risk compounds, improve the reliability and coverage of future monitoring studies, and develop new mitigation measures.

Introduction

Pharmaceuticals have been used by humans for centuries with commercialization beginning in the late 19th Century. Aside from pioneering studies in the 1970s and 1980s1−3 pharmaceuticals have only emerged as a major group of environmental contaminants over the last 15 years.4−7 Their presence in numerous environmental compartments including surface and ground waters, soils, and biota is now well established8 and the predominant pathway of entry to the environment is considered to be postconsumption excretion to the sewer network and subsequent passage to rivers via straight piping, sewage treatment plants (STPs; where their removal is variable e.g., ref (9)) or sewer overflows.10−12 Pesticide research in the 1990s identified clofibric acid as a widespread aquatic contaminant,13 which in turn sparked an expansion of method development and pharmaceutical research in subsequent years.14,15 These studies have vastly improved the reliability, availability, and precision of pharmaceutical detection methods.14

The shift from gas to high-performance liquid chromatography with tandem mass spectrometry (HPLC-MS/MS) has been a key driver in improving knowledge in recent years.16 Despite the availability of these methods, analysis and monitoring of pharmaceuticals in freshwaters remains far from routine and research is often sporadic and isolated. This is despite an increased awareness of the potential effects of pharmaceuticals on ecosystems and the services they provide.16−20 Existing research indicates that pharmaceuticals are generally present in freshwaters within the ng L–1 range and, at these subtherapeutic levels, the risk of acute toxicity is thought to be negligible.21 However, there are substantial knowledge gaps in terms of chronic, long-term exposure of nontarget aquatic organisms and the effects on ecosystem functioning.16 Data are available to suggest that some compounds may display chronic effects at or close to the levels detected in the environment.17,20 Moreover, the development of antibiotic resistant bacteria is a major public health concern; the prudent use of pharmaceuticals in the future is seen as key to reducing risks to public health and the environment.19,22

It is likely that pharmaceutical consumption will increase in coming years, particularly in developing countries and those with aging human demographics.23,24 Nevertheless, pharmaceutical compounds currently receive minimal consideration by regulators, policy makers, and managers,25 perhaps because there have been few attempts to amalgamate research findings from disparate spatial and temporal studies. However, the status quo is unlikely to remain in future, and the European Union has already started the process of adding the anti-inflammatory drug diclofenac to its list of Priority Substances.26 This change will potentially mean that in the future member states must maintain concentrations below a defined Environmental Quality Standard in an attempt to meet the requirements of good ecological status under the Water Framework Directive.27

This study synthesizes the disparate research on pharmaceutical occurrence in freshwaters at national, regional, and global scales. In particular we critique current research effort by compound class and individual substance. We also present a critical review of sampling strategies and methods adopted by researchers in this field, a crucial factor in considering how reliable and representative data are. Moreover, we provide a brief summary of the environmental effects of pharmaceuticals in freshwater ecosystems to highlight potentially high risk compound classes. The substantial assembled database is provided as a tool to better inform future research on the occurrence andeffects of pharmaceuticals in freshwaters, and to identify key areas where future research should be focused. Finally, we discuss the benefits of meta-analyses such as this in support of policy development to target the highest risk and most widespread compounds.

Methodology

A review was conducted via a search of the Web of Knowledge (WoK) publications database (http://apps.isiknowledge.com/) on March 6, 2011. The search term below was applied to the title, abstract, and keywords of articles:

(((((pharmaceutical* OR API* OR drug* OR PPCP* OR PhAC*) AND (aquatic* OR river* OR stream* OR “surface water*” OR freshwater* OR effluent* OR wastewater* OR “wastewater*”)))))

Refined by: Document Types=(ARTICLE OR REVIEW OR ABSTRACT) AND Research Domains=(SCIENCE & TECHNOLOGY) AND Languages=(ENGLISH) AND Subject Areas=(ENVIRONMENTAL SCIENCES & ECOLOGY OR PUBLIC, ENVIRONMENTAL & OCCUPATIONAL HEALTH OR MARINE & FRESHWATER BIOLOGY OR WATER RESOURCES OR BIODIVERSITY & CONSERVATION)

This was intended to identify all studies that analyzed for pharmaceuticals in either STP effluent or receiving waters; there was no restriction on timespan for this query. Research conducted by governmental departments or reported in the “gray” literature is also available; for example the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (http://www.epa.gov/ppcp/) but such work was not included here. The acronyms API (active pharmaceutical ingredient), PPCP (pharmaceuticals and personal care products), and PhAC (pharmaceutically active compound) are the most widely used by researchers in this field. This initial search yielded 57 289 results which were sorted by their relevance to the search term (using the in-built WoK algorithm).

The refined search criteria yielded 18 245 results and consequently the study was constrained further to the 28 most common journals returned by the search; these 28 accounted for ∼50% of results (9072 records) and included most major environmental and analytical chemistry journals. The remaining records were sorted by relevance and the first 1000 results were examined individually. The cutoff of 1000 and top 28 journals results was deemed necessary due to the time taken to assess each individual data source for the meta-analyses, versus the “success rate” for inclusion. The criterion for inclusion in the database was that a study explicitly analyzed for, detected, and quantified at least one human-use pharmaceutical compound in either STP effluent or receiving waters. From these 1000 studies, only 236 met the inclusion criterion (Table 1). While a more exhaustive search may have improved coverage, the assembled database represents the broadest review of the most detailed research studies to date.

Table 1. Summary of Journal Sources for the 236 Studies Included in the Full Database.

| journal | record count | % total (236) |

|---|---|---|

| Journal of Chromatography A | 42 | 17.80 |

| Environmental Science & Technology | 34 | 14.41 |

| Water Research | 34 | 14.41 |

| Science of the Total Environment | 33 | 13.98 |

| Chemosphere | 27 | 11.44 |

| Environmental Toxicology and Chemistry | 23 | 9.75 |

| Analytical and Bioanalytical Chemistry | 11 | 4.66 |

| Environmental Pollution | 9 | 3.81 |

| Journal of Hazardous Materials | 9 | 3.81 |

| Water Science and Technology | 8 | 3.39 |

| Aquatic Toxicology | 1 | 0.42 |

| Environmental Science and Pollution Research | 1 | 0.42 |

| Environmental Health Perspectives | 1 | 0.42 |

| Talanta | 1 | 0.42 |

| Archives of Environmental Contamination and Toxicology, | 1 | 0.42 |

| Ecotoxicology and Environmental Safety | 1 | 0.42 |

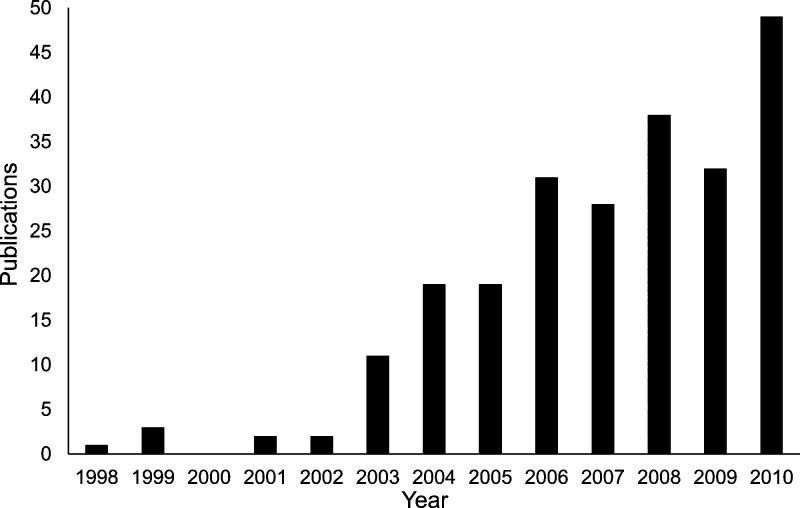

Analysis of publication dates of the 236 studies showed a clear upward trend from the late 1990s onward (Figure 1). The majority of studies included (>80%) were published between 2005 and 2010, a trend most likely driven by the advancement of analytical techniques such as HPLC-MS/MS and increased interest in pharmaceutical pollution.16 This is reflected in the relatively high number of studies published in analytical chemistry journals such as Journal of Chromatography A and Analytical and Bioanalytical Chemistry (Table 1) despite neither of these journals having a specific environmental focus.

Figure 1.

Number of publications per year for the 236 published studies included in the database shows a rapid increase after 2003.

For each of the 236 studies the following data were extracted from the main report body or Supporting Information: Compound(s) detected; Country; Median and maximum concentration(s); Sampling technique(s) adopted; Sampling period; Analytical methodologies; Number of samples; Number of detections; Number of no detections; Frequency of detection; Referencing information; Any pertinent information (e.g., raw drinking water or estuarine sampling). Median and maximum concentrations were recorded when explicitly stated by authors or in some cases were calculated using data tables and in a small number of cases, concentrations had to be derived from graphical representations such as boxplots. Other concentrations stated in the studies were not recorded as it was felt that median levels were appropriately representative of “normal” conditions and maxima represent peaks in concentrations indicative of a worst-case scenario in terms of ecological effects.

The ratio of maximum:median concentration was also calculated and recorded; this ratio was available for 74% of the studies. For the purposes of this review only data concerning receiving waters (and not treated effluent) were subjected to meta-analysis because these were the most relevant indicators of potential effects in freshwater ecosystems. Effluent concentrations are inherently variable28 and are less reliable as indicators of effects given the broad range of dilution factors and chemical transformations to which they are subjected when entering receiving waters. When published studies reporting only treated effluent concentrations were excluded, a total of 155 studies were retained. Fifty studies (26.8%) contained samples of a nonriverine source (marine, estuarine, groundwater, raw drinking water, or sediment samples); lentic and raw drinking water samples were included as these were deemed relevant. Five studies contained samples extracted from freshwater sediments and although these are relevant to freshwaters, the small number of studies was deemed insufficient to merit inclusion. The full database containing all receiving water records is freely available upon request or from http://www.wateratleeds.org.

All concentrations were recorded in the database as nanograms per liter (ng L–1) to enable direct comparison. Individual compounds were then grouped into the following classes: Antibiotics; Antidepressants; Antiepileptics; Antivirals; Blood lipid regulators; Cancer treatments; Contrast media; Endocrine drugs; Gastro-intestinal drugs; Illicit drugs; Other cardiovascular drugs; Other CNS (central nervous system) drugs; Others; Painkillers and Respiratory drugs.

Results

Table 2 presents a summary of the 61 most frequently encountered pharmaceuticals (out of a total of 203); these 61 compounds represent the 1st to 50th most frequently studied compounds in the database. Median concentrations ranged from 6.2 ng L–1 for the antibiotic sulfathiazole to 163 673 ng L–1 for the antibiotic ciprofloxacin which also had the highest maximum concentration of the entire database at 6 500 000 ng L–1. Of these 61 compounds, 39% were antibiotics, 21% were painkillers, 20% were cardiovascular drugs or blood lipid regulators, and 3% were antidepressants.

Table 2. Summary of Occurrence Data for the Top 61 Most Frequently Studied (1st to 50th) Pharmaceutical Compounds in Freshwater Ecosystems.

| compound | compound type | median concn (ng L–1) | max concn (ng L–1) | no. observations | mean detection frequencya(%) | references |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| amoxicillin | antibiotics | 59.9 | 622.0 | 5 | 29.8 | (31−35) |

| amphetamine | illicit drugs | 10.3 | 50.0 | 5 | 29.7 | (31,32,36−38) |

| aspirin (acetylsalicyclic acid) | painkillers | 662.6 | 90 000.0 | 22 | 81.3 | (32,33,39−58) |

| atenolol | other cardiovascular drugs | 90.9 | 859.0 | 24 | 83.0 | (31,32,37,39,45,47,59−75) |

| atorvastatin | blood lipid regulators | 39.7 | 101.0 | 5 | 18.2 | (37,74,76−78) |

| azithromycin | antibiotics | 188.4 | 1546.7 | 6 | 40.8 | (37,64,69,79−81) |

| benzoylecgonine | painkillers | 72.8 | 770.0 | 10 | 74.6 | (32,36,38,82−87) |

| bezafibrate | blood lipid regulators | 85.0 | 15 060.0 | 38 | 58.0 | (32,40,43,45,47,53,54,61,64,66,68,69,72,75,78,88−96) |

| carbamazepine | antiepileptics | 174.2 | 11 561.0 | 98 | 85.0 | (17,31,32,37,41,42,45,47,49,51−55,58,60,62−81,84,88−90,92,93,96−124) |

| chlortetracycline | antibiotics | 142.0 | 2800.0 | 8 | 18.2 | (34,103,108,109,125−128) |

| cimetidine | gastro-intestinal drugs | 97.3 | 1338.0 | 9 | 47.5 | (31,32,37,47,98,100,103,108,126) |

| ciprofloxacin | antibiotics | 163 673.5 | 6 500 000.0 | 17 | 33.4 | (29,34,35,37,61,67,72,73,75,77,80,108,126,129−132) |

| citalopram | antidepressants | 19.8 | 219.0 | 6 | 100.0 | (37,65,70,133−135) |

| clarithromycin | antibiotics | 16.5 | 260.0 | 13 | 53.9 | (35,37,52,61,67,69,70,75,96,101,121,136,137) |

| clindamycin | antibiotics | 20.6 | 1100.0 | 8 | 48.0 | (33,34,37,52,67,121,129,136) |

| clofibric acid | blood lipid regulators | 136.2 | 7910.0 | 26 | 52.9 | (32,37,45,47,50,51,54,57,58,61,64,66,68−70,78,89,94,96,115,120,122,138−141) |

| cocaine | illicit drugs | 9.3 | 115.0 | 9 | 49.8 | (32,36,38,82,83,86,87,142) |

| codeine | painkillers | 49.6 | 1000.0 | 17 | 64.4 | (31,32,38,47,49,82−84,87,103,108,117,126,142−144) |

| diazepam | other CNS drugs | 8.7 | 33.6 | 9 | 59.6 | (37,49,61,70,71,74,84,110,131) |

| diclofenac | painkillers | 136.5 | 18 740.0 | 80 | 75.5 | (32,33,39−45,47,52−55,57,58,60,64,66−72,74,78,90−96,99,107,115,116,119−121,123,124,127,139−141,145−153) |

| diltiazem | other cardiovascular drugs | 13.0 | 146.0 | 13 | 36.3 | (32,47,52,69,77,97,98,100,101,103,108,121,126) |

| diphenhydramine | respiratory drugs | 88.7 | 1410.6 | 6 | 28.7 | (37,79,80,101,103,108) |

| doxycycline | antibiotics | 25.9 | 400.0 | 5 | 23.7 | (34,37,109,125,128) |

| enalpril | other cardiovascular drugs | 316.7 | 1500.0 | 6 | 25.6 | (29,37,61,71,75,126) |

| enrofloxacin | antibiotics | 5754.0 | 30 000.0 | 5 | 38.0 | (29,34,80,108,131) |

| erythromycin | antibiotics | 50.8 | 90 000.0 | 32 | 55.5 | (31−33,35,47,51,61,64,66,68,70,75,80,89,96,101,103,104,107−109,117,121,125−127,131,137,146,154−156) |

| fluoxetine | antidepressants | 17.8 | 596.0 | 12 | 29.2 | (45,66,71,74,77,78,98,103,126,133−135) |

| furosemide | other cardiovascular drugs | 28.3 | 630.0 | 7 | 58.7 | (32,37,39,47,61,69,75) |

| gabapentin | antiepileptics | 208.1 | 1887.0 | 5 | 94.2 | (31,32,47,67) |

| gemfibrozil | blood lipid regulators | 103.3 | 7780.0 | 52 | 45.3 | (33,40−44,52,54−58,60,62,64−68,71,74,78,89,90,92,93,96,104,107,116,121,126,127,141,157−159) |

| ibuprofen | painkillers | 503.8 | 31 323.0 | 92 | 63.0 | (32,33,37,40−51,54−58,60−62,64−66,68,72,74,75,78,80,88−93,95,96,99,107,112,114−116,118,120−122,126,127,138−141,146,148,149,151,153,157−165) |

| indomethacin | painkillers | 51.0 | 380.0 | 11 | 41.9 | (40,54,66,68,69,78,89,96,121,124,157) |

| ketoprofen | painkillers | 97.0 | 2710.0 | 38 | 40.1 | (32,37,40−45,47,54,55,60,64,68,69,72,78,91,92,95,99,104,114−116,120,139,145,158) |

| lincomycin | antibiotics | 23.2 | 730.0 | 11 | 50.3 | (34,35,51,61,75,89,104,108,109,121,126) |

| mefenamic acid | painkillers | 26.3 | 366.0 | 14 | 51.3 | (32,39,47,51,57,58,64,66,68,114,141,146,150,160) |

| metoprolol | other cardiovascular drugs | 104.5 | 8041.1 | 22 | 89.6 | (29,31,32,45,53,54,56,59,60,63,65−68,70,72,111,119,131,133,157) |

| morphine | painkillers | 6.5 | 108.0 | 8 | 45.9 | (38,83−85,87,143,144) |

| naproxen | painkillers | 98.0 | 19 600.0 | 65 | 69.0 | (32,33,37,40−47,50,51,54−58,60,62,64−68,71,72,74,78,89−92,94−96,104,107,114,115,120,122,127,139,141,145,153,157−159,161,166) |

| norfloxacin | antibiotics | 11 412.4 | 520 000.0 | 11 | 52.3 | (29,34,67,108,126,131,132,154−156,167) |

| ofloxacin | antibiotics | 628.6 | 11 000.0 | 16 | 60.0 | (29,33,35,37,64,66−68,72,75,130−132,154,155,167) |

| oxytetracycline | antibiotics | 74 757.7 | 712 000.0 | 11 | 50.0 | (30,34,35,37,61,125,126,128,131,151,168) |

| paracetamol | painkillers | 148.2 | 15 700.0 | 35 | 51.6 | (31−33,39,45,47,51,65−70,76,77,79−81,89,97,98,100,103,107,108,116,117,122,126,127,148,160,169,170) |

| pentoxifylline | other cardiovascular drugs | 197.1 | 299.1 | 5 | 39.6 | (49,90,104,107,112,118) |

| primidone | antiepileptics | 70.9 | 590.0 | 5 | 75.8 | (67,70,74,84,106) |

| propranolol | other cardiovascular drugs | 18.8 | 590.0 | 22 | 69.4 | (31,32,41,42,45,47,54,59,60,64,66−68,110,124,127,146,148,150,157,165,171) |

| propylphenazone | painkillers | 31.4 | 180.0 | 5 | 94.0 | (64,66,68,96,114) |

| ranitidine | gastro-intestinal drugs | 26.5 | 570.0 | 11 | 35.3 | (32,47,61,64,66,68,75,98,103,108,126) |

| roxithromycin | antibiotics | 20.4 | 2260.0 | 11 | 49.0 | (34,70,96,109,126,136,137,154−156,172) |

| salbutamol | respiratory drugs | 25.3 | 1440.0 | 8 | 39.9 | (32,37,47,54,61,75,98,160) |

| sotalol | other cardiovascular drugs | 101.6 | 1820.0 | 10 | 96.0 | (37,59,62,63,66−68,70,72,73) |

| sulfachloropyridazine | antibiotics | 34.3 | 70.0 | 5 | 3.3 | (79,104,109,125,128) |

| sulfadiazine | antibiotics | 62.6 | 2312.0 | 5 | 48.6 | (154,156,173−175) |

| sulfadimethoxine | antibiotics | 9.7 | 3955.6 | 15 | 44.2 | (45,52,67,69,79,100,108,109,125−128,173−175) |

| sulfamethazine | antibiotics | 146.1 | 6192.0 | 12 | 30.1 | (33,79,104,109,121,125−128,156,174,175) |

| sulfamethoxazole | antibiotics | 83.0 | 11 920.0 | 77 | 66.9 | (31−35,37,41,45,53,60,62,64−71,74,76,77,89,92,93,96−98,101,103,107−110,117−119,121,124−130,136,137,151,154,155,167,173−176) |

| sulfapyridine | antibiotics | 11.5 | 12 000.0 | 8 | 75.5 | (31,32,47,65,173−175) |

| sulfathiazole | antibiotics | 6.2 | 960.6 | 8 | 47.7 | (34,79,109,125,151,173−175) |

| tetracycline | antibiotics | 41.5 | 300.0 | 10 | 45.0 | (34,37,89,125−128,131,151,168) |

| tramadol | painkillers | 801.6 | 7731.0 | 5 | 87.0 | (31,32,47,84) |

| trimethoprim | antibiotics | 53.4 | 4000.0 | 49 | 49.8 | (29,31−34,41,42,45,47,60,64−68,70,71,74,76,77,80,81,89,90,96,98,100,101,103,104,107−110,117,118,121,126,129,133,136,137,146,150,165,167,169,172,173) |

| tylosin | antibiotics | 12.5 | 280.0 | 7 | 35.4 | (34,61,89,125−127,131) |

Mean detection frequency is the mean of all stated or calculated detection frequencies (no. positive detections/no. samples analyzed) for that particular compound. Sixty-two studies representing 32.2% of all database records did not state a detection frequency, or sampling numbers to enable its calculation.

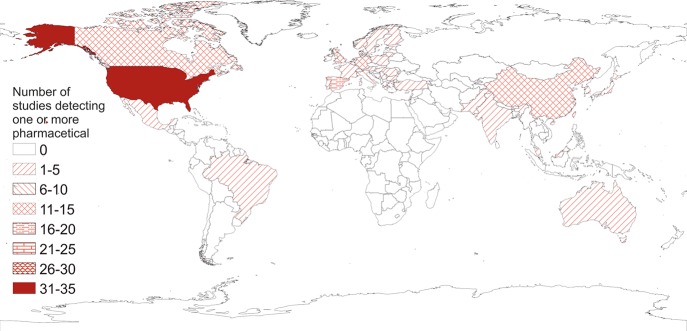

From 155 published studies pharmaceutical compounds were identified in receiving waters across 41 countries on all continents except Africa and Antarctica (Figure 2). The database included 1417 records representing 67 903 analyses and median/maximum concentrations from >14 155 samples (27 studies did not state sampling numbers) and >24 989 positive detections of pharmaceuticals; this equated to an overall detection frequency of 37%. The results illustrated a heavy bias toward research in Europe and North America which accounted for 80% of studies, with a further 16% in Asia (predominantly China). Only three studies reported from South America and just one was from the Middle East (Israel). The United States had the most studies (34) and Spain, China, Germany, Canada, and the UK were the only other countries to have >10 studies. Seventy-one percent of nations in the database had three or fewer studies conducted, including very large or populous nations such as Japan, Brazil, Mexico, Pakistan, and Australia.

Figure 2.

Global-scale distribution of the number of published studies identifying pharmaceuticals in inland surface waters.

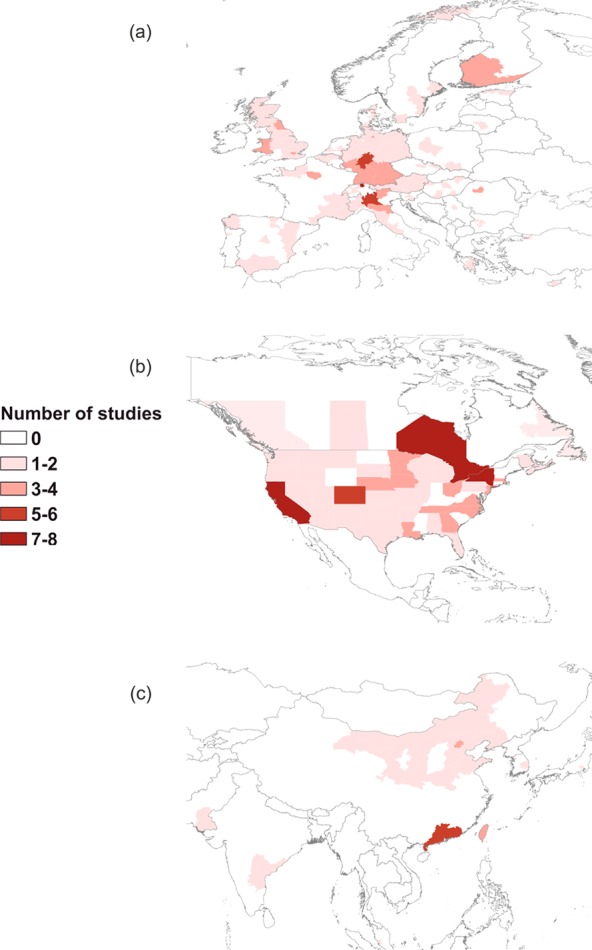

When examining data at the “continental” scale strong biases are again evident (Figure 3). For example, just 6/176 provinces in Asia accounted for >50% of published studies in that region, with the most populous province in China (Guangdong) having the highest number at six. In Europe most studies have been undertaken in Germany, Spain, and Switzerland (in the Elbe, Rhine, Ebro, and Llobregat basins). The spread of research in the UK is even, covering most counties except South West England and Northern Ireland; however these are generally isolated, with the only repeated work undertaken in Wales, Greater London, and the North East. A similar story is evident in North America with a good spread of research but multiple studies in the populated states of California, New York, and Ontario; 9 Canadian provinces (69%) and 28 U.S. states (55%) have just one or fewer studies.

Figure 3.

Number of published studies detecting at least one pharmaceutical compound in (a) European regions, (b) North American states, and (c) south Asian provinces.

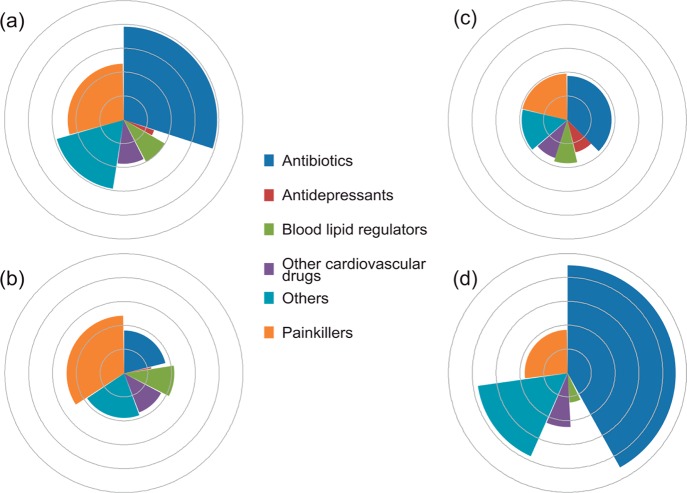

Globally, painkillers were the most frequently detected compounds accounting for 31% of records with a median concentration of 230 ng L–1 followed by antibiotics (21%, 8128 ng L–1; Figure 4a). The remaining compound classes each demonstrated medians of <100 ng L–1 except for Others (830 ng L–1 including antiepileptics and contrast media). The picture changes when data are examined regionally (Figure 4b–d). For example, the most commonly encountered pharmaceuticals were painkillers in Europe (34%, median concentration 261 ng L–1) and antibiotics in North America (38%, 71 ng L–1) and Asia (42%, 33,446 ng L–1). Contrast media and respiratory drugs had particularly high median concentrations in Asian waters of 1257 and 50 023 ng L–1 respectively, although these were from a small number of studies contaminated by effluent from pharmaceutical manufacturing facilities.29,30 Additionally, antidepressants were more frequently detected in North America (9%, 25 ng L–1) compared to Europe and Asia where they account for <1% of records.

Figure 4.

Relative frequency of detection and median concentration of pharmaceuticals in receiving waters: (a) global, (b) Europe, (c) North America, and (d) Asia. (The circumference of each fan is scaled by the relative proportion of detections. Each point outward on the radial axis represents 10y of the median concentration in ng L–1. For example, the innermost circle represents 101 ng L–1; the second represents 102 ng L–1, etc.)

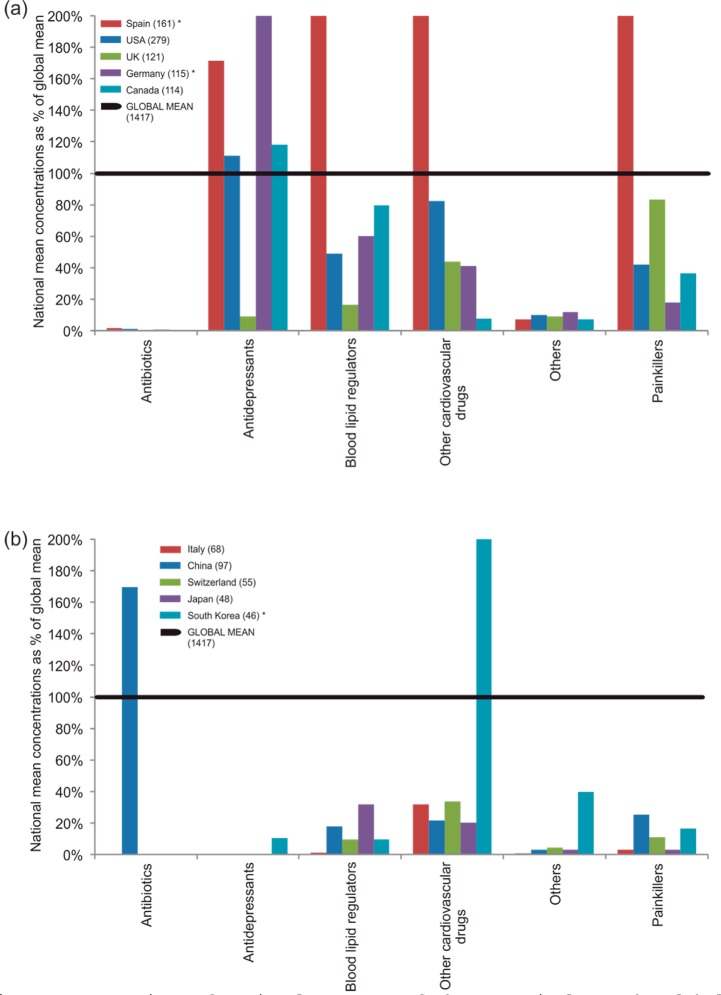

A striking result from mean concentrations in the top 10 most studied countries was that all except China demonstrated very low proportions of the global mean (<2%) for antibiotics (Figure 5); this was due to the very high concentrations detected in a small number of Asian studies. Interestingly, China displayed values well below the global means for all compound classes ranging from 2 to 25%. Spain was above the global mean (171–441%) for all classes except Antibiotics and Others compared to Italy, Switzerland, Japan, and the UK which were below the global mean for all classes. No single country in the top 10 demonstrated mean concentrations above 40% of the global mean for Others. This is due to there being only seven countries within this group which are heavily skewed by one study in India detecting very high concentrations (15 000 ng L–1) of the antifungal terbinafine.29

Figure 5.

Comparison of national averages of pharmaceuticals to the global average for (a) the 1st to 5th and (b) the 6th to 10th top countries (as determined by number of entries in the database; represented by the number in brackets. Global mean is the mean concentration for all records of that compound group). (Values exceeding 200% of global mean: Spain (blood lipid regulators 441%, other cardiovascular drugs 213%, painkillers 209%), Germany (antidepressants 246%), South Korea (other cardiovascular drugs 404%)).

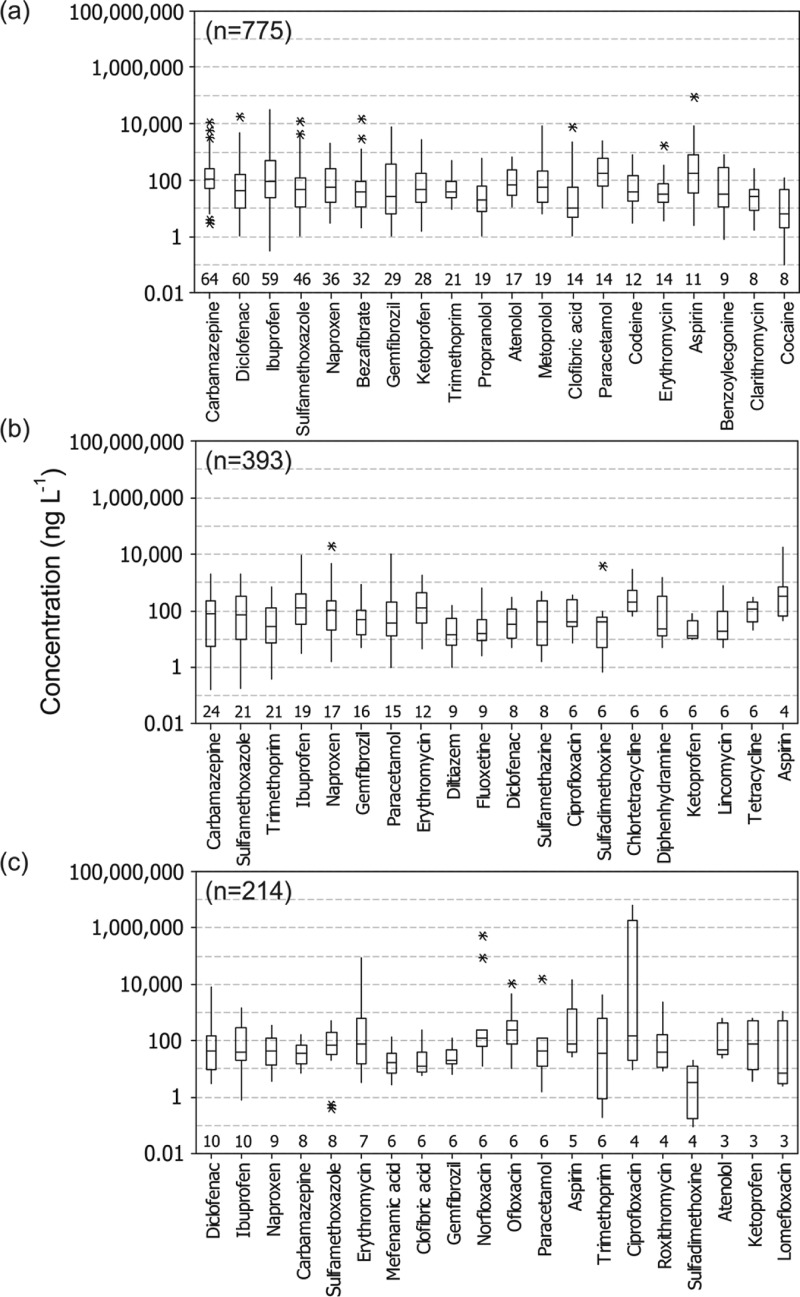

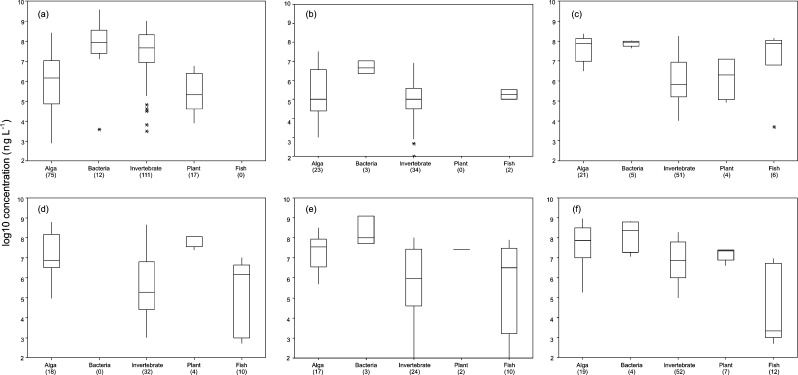

The top 20 most frequently studied compounds in Europe included 8 painkillers, 6 cardiovascular drugs, and 4 antibiotics with median concentrations for all compounds below 100 ng L–1 except aspirin and paracetamol (median approximately 190 ng L–1; Figure 6). A similar picture was evident in North America and Asia with mostly antibiotics, cardiovascular drugs, and painkillers present in the top 20 and median concentrations generally <100 ng L–1. A small number of compounds (6 in Europe and Asia and 2 in North America) had maxima >10 000 ng L–1. Of particular note was the antiepileptic drug carbamazepine which was the most frequently studied and detected compound in both North America and Europe and third in Asia. The minimum detection frequency for compounds displayed in Figure 6 was 9% (diclofenac in North America) but average detections frequencies were 70% (Europe), 27% (North America), and 65% (Asia).

Figure 6.

Boxplots of the 20 most commonly encountered pharmaceuticals in (a) European, (b) North American, and (c) Asian receiving waters. n values represent total number of records for the respective region and values above the x axes represent records for each of the 20 specific compounds. (Boxes represent interquartile ranges with median concentration represented by the horizontal line. Whiskers show the range of data and asterisks represent outliers).

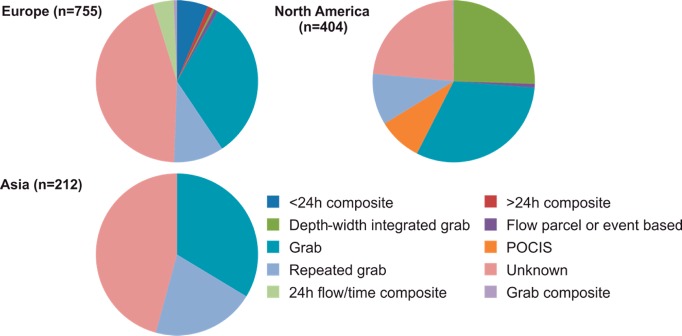

A major finding from this analysis was that 45% of European and Asian and 23% of North America studies failed to provide any details of the sampling regime and techniques adopted (Figure 7). Isolated and nonrepeated grab sampling was by far the most common technique adopted in 31–34% of studies. Slightly more representative repeated grab sampling over periods ranging from days to years was adopted in just 12% of studies. Additional techniques are available including composite sampling and the use of passive samplers (e.g., polar organic contaminant integrative sampling, POCIS) which give an integrated sample over a period of days to weeks. However, these were adopted by just 11% of European and 9% of North American studies and not at all elsewhere.

Figure 7.

Pie chart summarizing sampling methodologies employed in detection of pharmaceutical compound(s) in rivers. (n = number of records in the database; POCIS = polar organic contaminant integrative sampler).

Chronic effects data for the six main compound classes were collated from four major reviews17,20,21,177 and any duplicate results were removed manually. Chronic data (rather than acute) was chosen as these were deemed to be more representative of actual long-term, low-level exposure of aquatic organisms;178 the end points assessed included lethal and sublethal indices (e.g., feeding, growth, behavior, and reproduction). The data included here are not intended as a direct assessment of particular compound toxicity but rather to highlight where overlaps between measured environmental concentrations and chronic toxicity indicate potential environmental risk.

The ranges of chronic toxicity vary markedly across compound types and taxa (Figure 8). From these data antidepressants appear to pose particular risk to all taxa except bacteria with effective concentrations ranging from μg to mg L–1. Invertebrates and fish show chronic toxic effects at sub mg L–1 levels for cardiovascular drugs and Others; fish also appear susceptible to painkillers with median effects manifesting at 40 μg L–1. This summary highlights where research is lacking; in particular there were no studies examining the effects of antibiotics on fish, antidepressants on aquatic plants, or cardiovascular drugs on bacteria. Overall, bacteria and aquatic plants appear to be the least well studied whereas research on chronic effects in aquatic invertebrates is relatively abundant.

Figure 8.

Summary of chronic ecotoxicological data for pharmaceuticals and freshwater organisms across (a) antibiotics, (b) antidepressants, (c) blood lipid regulators, (d) other cardiovascular drugs, (e) others, and (f) painkillers; data summarized from refs (17, 20, 21, and 177).

Discussion

Spatial Distribution of Research

This study shows that knowledge of pharmaceutical occurrence is poor or absent for large parts of the globe, particularly in developing countries. The research that has been undertaken displays a heavy bias toward North America, Europe, and the more populous parts of China. Given that the consumption of pharmaceuticals is ubiquitous across the globe,179 there is clearly a pressing need to expand research into their occurrence particularly in Russia, southern Asia, Africa, the Middle East, South America, and eastern Europe. As more data becomes available, the better able researchers will be to highlight the scale of the problem and inform management decisions. Moreover, even where studies have been relatively numerous knowledge is still minimal compared to that for other stressors such as nutrients,180,181 acidification,182 river regulation,183 and sedimentation.184

When looking at the spread of research it is apparent that the spatial biases manifest at multiple scales. In Europe, an obvious cluster of research is evident around central Europe particularly and to a lesser extent in the UK and Spain. Research effort appears to be clustered around the high population areas of e.g., London, Paris, Hamburg, Frankfurt, California and the North American eastern seaboard, Beijing and Guangdong province in China. This is understandable given that pharmaceutical pollution can be expected to be at its greatest in densely populated areas, and a risk-based approach185 should target these receiving waters first. However, this leaves substantial proportions of Europe and North America with insufficient research. For example, in the UK no research has been conducted in the major urban areas of the West Midlands, Greater Manchester, or West Yorkshire which have a combined population of 6 million people.186 Researchers should expand monitoring efforts to previously unstudied catchments while at the same time increasing the length/breadth and temporal resolution of monitoring campaigns if the dynamics of pharmaceutical pollution are to be fully understood. Research in less densely populated and rural areas should also be a priority as it is probable that STPs in such locations are smaller and less advanced when compared to their larger counterparts serving urban areas.187

Coverage of Compound Classes

When viewed globally, antibiotics, antiepileptics, cardiovascular drugs (including blood lipid regulators), and painkillers accounted for 86% of all database records with carbamazepine being the single most commonly identified compound. A likely reason for this bias is that these drug types are the most widely prescribed and purchased over-the-counter.188,189 For example, cardiovascular drugs and painkillers were among the top three compound types prescribed to adults in the U.S. during 2007189 and as such could be expected to enter the environment in the highest concentrations. However, this leaves major groups of potentially toxic pharmaceuticals being poorly studied. For example, antidepressants, antivirals, cancer treatments, tranquilizers, and antifungals combined accounted for just 6.3% of records. A reason for this imbalance in detections could be that researchers have not been analyzing these compounds in environmental samples, rather than their being genuinely scarce. It may also be possible that less frequently detected compounds are less refractory and are more efficiently removed during sewage treatment (e.g., (9)). Further studies on these “rarer” compounds are particularly necessary because some studies have shown effects on microalgal communities even at very low environmental concentrations.190 Interestingly, antidepressants were the most widely prescribed compounds among young American adults,189 and this is reflected in the relatively high number of North American studies analyzing these compounds (9%) when compared to Asia and Europe (1%).

The analysis confirmed that knowledge of some pharmaceutical groups is almost completely lacking, with >50% of entries in the database represented by just 14 compounds (all of which are antibiotics, antiepileptics, cardiovascular drugs, or painkillers). The entire database represents only a snapshot (203) of all pharmaceuticals approved for use, which is estimated to be well over 5000 in Europe alone.191 This gives a conservative estimate that fewer than 4% of pharmaceuticals have been analyzed for and detected in freshwaters. It demonstrates a clear need for future research to be expanded across the less well studied compounds, particularly those identified as posing environmental risk.

Pharmaceutical Concentrations in Freshwaters

One of the most striking results from the data was the relatively high concentrations for antibiotics and Others (comprising just the respiratory drug ceterizine and the contrast medium ioprimide in Asia) compared to other classes. However, these very high concentrations were skewed by a small number of studies which analyzed waters receiving pharmaceutical manufacturing effluent.29,30 Up until recently pharmaceutical manufacturing facilities (PMFs) were considered a low priority given the high value of pharmaceutical products and the adoption of “good management practice” by the industry intended to reduce wastage and loss to the environment.192 However, several studies have shown that PMFs can be a significant source of pharmaceuticals to receiving waters both within developed (e.g., (193)) and developing countries (e.g., refs (30, 194)); these should be considered a priority for future research effort given the potential for strong localized effects.

National means were compared to global means to evaluate the appropriateness of local studies as indicators of concentrations at larger spatial scales. These comparisons highlight the importance of local studies to inform stakeholders and regulators, and emphasize a need for caution when scaling up to larger spatial scales, or vice versa. Given the relative paucity of data it is possible for a small number of studies at particularly polluted locations to have a disproportionate influence on national and even global mean concentrations. The very high concentrations for antibiotics in Asia and globally are an example of this problem. The global median antibiotic concentration (8135 ng L–1) reduces (58 ng L–1) if just two Chinese and Indian studies are excluded.29,30

Frequently Studied Compounds

Ibuprofen and sulfamethoxazole were consistently within the top five studied compounds across all regions and had similar concentration ranges (1–10 000 ng L–1). Notably though, very high concentrations (up to a maximum of 10 000 000 ng L–1) of ciprofloxacin, erythromycin, norfloxacin, and ofloxacin were evident in Asia; this is of concern because these are well within the range known to cause acute and chronic toxic effects to aquatic organisms.20 Also of note was the presence of the antidepressant fluoxetine in the top 20 North American compounds; this type of antidepressant causes chronic effects at the low ng L–1 range,195,196 well below the median and maximum concentrations detected in the environment. Carbamazepine is the single most widely studied and detected compound in Europe and North America but is not generally considered to pose a risk of acute or chronic toxicity to freshwater organisms (e.g., (197)). However, its refractory nature and generally ubiquitous presence in STP effluent may make carbamazepine a useful source-specific tracer of domestic wastewater contamination.198

Sampling Strategies

Perhaps the most crucial step in reliably quantifying the presence of compounds such as pharmaceuticals in freshwaters is the collection of a representative sample using appropriate strategies and methodologies.199,200 Sampling uncertainty can often exceed that during the analytical procedure.201 Large sample numbers and sophisticated analytical techniques, although important, should not be seen as a substitute for the collection of a representative sample199 and a poor sampling can be the dominant source of error in water quality data.202 Some exponents of sampling theory have gone so far as to argue that “nothing good (certainly nothing representative) has ever come from grab sampling”203 due to the fact they provide a mere snapshot in time. Grab sampling does have a part to play in furthering our understanding of pharmaceutical occurrence particularly for extensive spatial or long-term studies where the equipment and set-up costs of more representative techniques may be prohibitive. However, efforts should be made to adopt more representative techniques wherever possible. For pharmaceuticals in particular, non-repeated grab sampling is unlikely to be representative as sample concentrations have been shown to vary considerably over time.28

A possible explanation for the lack of robust sampling is the relatively high proportion of studies published in journals with a focus on analytical chemistry (namely Journal of Chromatography A, Analytical and Bioanalytical Chemistry, and Talanta). The main thrust of these journals is method development rather than the collection of large, representative data sets and this is borne out by the fact that 64% of these papers did not state the sampling methodologies adopted (c.f. 44% across all journals) and only 11% of studies adopted repeated grab or composite sampling strategies (c.f. 21–23% across all journals). This propensity of analytical studies to collect fewer samples for shorter periods is probably due to analytical chemists needing to validate methods on “real” samples which require only minimal numbers to achieve. The contribution of these papers should not be understated though, as they provide reliable and sophisticated analytical methods that can be adopted as part of more representative sampling studies. The occurrence data alone provided by these studies covers 94 compounds in 34 countries, so minor modifications to sampling strategies and subsequent reporting by these scientists could benefit the field substantially.

In addition to the techniques adopted, appropriate sampling numbers, duration, and frequency are crucial to obtain a reliable quantification of variable water quality parameters. Most studies collected a relatively small number of samples (1–50) with only 13% of studies collecting for >12 months. This indicates a dearth of long-term monitoring which may be crucial in understanding seasonal and annual dynamics. Conversely, sampling at an appropriately high temporal resolution over the short-term is equally important if we are to fully quantify variability over the periods of minutes to days (e.g., refs (28, 199, 200)). Studies on other aquatic contaminants have shown the importance of a robust sampling strategy; Rabiet et al.205 demonstrated that fixed time interval grab sampling underestimated pesticide fluxes from a small catchment by as much as a factor of 5. Robertson206 recommended tailoring sampling strategies to the variable of interest and the duration of the study when monitoring in small streams. An interesting research question would be the systematic comparison of measured concentrations between grab sampling and continuous or composite techniques; the database assembled here may prove useful in such a study.

These data clearly highlight the importance of adopting flexible, appropriate sampling strategies in order to supply reliable and representative data. Furthermore, researchers should explicitly state the techniques employed in addition to sample numbers, frequencies, and locations so that other researchers can fairly evaluate the results presented and use them to inform their own research.

Effects of Pharmaceuticals on Freshwater Ecosystems

Despite the widespread presence of many pharmaceuticals in freshwaters, some risk assessments have suggested that they pose little risk of acute or chronic toxicity at environmentally relevant concentrations.17,207 The data summaries presented here and elsewhere indicate potential overlap between chronic effects levels and the concentrations detected within freshwaters. In particular, potential risks are evident for invertebrates and fish from antibiotics and cardiovascular drugs in Asia and from the contrast media, tranquilizers, and antiepileptics (carbamazepine) across all regions. Additionally, invertebrates and fish are potentially at risk (i.e., low margin of safety) from antidepressants and painkillers in North America. While this may suggest that future research should shift toward less well studied but more “toxic” compounds, particular care needs to be taken with these conclusions because many effects studies on aquatic “ecosystems” have been undertaken using ecologically unrealistic (i.e., single species) laboratory experiments. Additionally, such studies tend to test at concentrations that are orders of magnitude above those detected in the environment and be run over short time-scales, and as such do not adequately address the issue of low-level, chronic exposure. Studies which have examined the effects of low-level pharmaceutical exposure on aquatic ecosystem structure and functioning are rare but have indicated that pharmaceuticals can display significant effects on important ecosystem services.208−211

The data presented here are a useful indicator of particular compound classes exhibiting some kind of toxic effect at the levels stated. As such, the combined occurrence and effects data sets can serve as a guide for future ecotoxicological research. However, they should be treated with caution as they integrate a variety of toxicological tests which employ a range of exposures and end points across a variety of species. The exposure regime of any testing should attempt to cover both the median as a measure of frequently encountered concentrations, and the maximum concentration as an indicator of worst-case exposure. Furthermore, standard assessments of toxicity, while useful in producing comparable results, suffer from low bio-complexity and environmental relevance, so researchers need to adopt a more flexible, knowledge-based approach tailored to specific risks.212 A problem with undertaking research in “natural” freshwaters is that there will probably be myriad other compounds in addition to the one of interest, meaning a high potential for confounding effects. More realistic controlled experiments need to be designed and undertaken (e.g., (213)) before researchers can make better predictions about ecosystem response to pharmaceutical pollution. Researchers and regulators must therefore be wary of dismissing particular pharmaceuticals as “low risk” on the basis of isolated and overly simplified laboratory studies.

Conclusion

This study is the first to assemble a comprehensive database of widely distributed information on pharmaceutical concentrations at global, continental, national, and provincial scales. In doing so it has highlighted large parts of the globe where knowledge of pharmaceutical occurrence is minimal or nonexistent. In particular, large parts of Asia, Africa, South America, and Australia should be seen as a priority for future research. Additionally, the majority of countries where research is sparse or absent are developing nations, and as such it is possible that the pharmaceutical consumption (and hence pollution) profile may differ markedly from that of developed nations. It may be the case that in developing countries water resource management has not yet progressed to the stage where environmental monitoring and regulation of pollutants typically start to be taken seriously.214

Even within the developed nations of Europe and North America there is a pressing need for better spatial coverage across all provinces and states. Future research should learn lessons from other fields and use appropriate, representative sampling strategies to give much more reliable estimates of the pollution problem. The current proposal for statutory monitoring of diclofenac in European waters26 will provide a substantial boost to our knowledge but researchers and regulators should also see this as an opportunity to increase our understanding of the thousands of other pharmaceuticals and domestic chemicals that routinely enter freshwaters via STPs.

The most striking results of this study were the very high concentrations reported (particularly antibiotics, painkillers, and antidepressants) that are within the range known to cause acute or chronic toxicity in aquatic systems. This challenges the assumption that pharmaceuticals in rivers generally pose little risk28 and highlights the need for an expansion of robust monitoring and the adoption of more realistic ecotoxicological experiments. Expanding research effort to previously understudied compounds (some antibiotics, antidepressants, respiratory drugs, and contrast media) and areas of the globe where research coverage is poor should be a priority. This is particularly important as in coming decades it is anticipated that pharmaceutical use will increase substantially, partly due to the aging population structure in developed countries, and with ongoing increases in the standard of living in developing countries. These improvements in quality of life are accompanied by an increase in meat consumption in developing countries215 which in turn may boost the consumption of veterinary pharmaceuticals posing additional environmental risk.

The database assembled in this study should serve as a useful tool for industry professionals, academics, regulators, and water managers in prioritizing future work on both pharmaceutical occurrence and the effects of such compounds on aquatic ecosystems. Ultimately, the results indicate that despite almost two decades of research effort, our knowledge of pharmaceutical occurrence and effects in the environment is still substantially lacking when compared to that of other aquatic pollutants.

Acknowledgments

This project was funded primarily via a Natural Environment Research Council PhD studentship (NE/G523771/1) to S.H.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

References

- Aherne G. W.; English J.; Marks V. The role of immunoassay in the analysis of microcontaminants in water samples. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 1985, 9(1), 79–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hignite C.; Azarnoff D. L. Drugs and drug metabolites as environmental contaminants: Chlorophenoxyisobutyrate and salicylic acid in sewage water effluent. Life Sci. 1977, 20(2), 337–341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richardson M. L.; Bowron J. M. The fate of pharmaceutical chemicals in the aquatic environment. J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 1985, 37, 1–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kidd K. A.; Blanchfield P. J.; Mills K. H.; Palace V. P.; Evans R. E.; Lazorchak J. M.; Flick R. W. Collapse of a fish population after exposure to a synthetic estrogen. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci., U.S.A. 2007, 104(21), 8897–8901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oaks J. L.; Gilbert M.; Virani M. Z.; Watson R. T.; Meteyer C. U.; Rideout B. A.; Shivaprasad H. L.; Ahmed S.; Iqbal Chaudhry M. J.; Arshad M.; Mahmood S.; Ali A.; Ahmed Khan A. Diclofenac residues as the cause of vulture population decline in Pakistan. Nature 2004, 427(6975), 630–633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwarzenbach R. P.; Escher B. I.; Fenner K.; Hofstetter T. B.; Johnson C. A.; von Gunten U.; Wehrli B. The Challenge of Micropollutants in Aquatic Systems. Science 2006, 313(5790), 1072–1077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wall R.; Strong L. Environmental consequences of treating cattle with the antiparasitic drug ivermectin. Nature 1987, 327(4), 418–421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daughton C. G.; Ruhoy I. S. Environmental footprint of pharmaceuticals: The significance of factors beyond direct excretion to sewers. Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 2009, 28(12), 2495–2521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tambosi J. L.; Yamanaka L. Y.; José H. J.; Moreira R. d. F. P. M.; Schröder H. F. Recent research data on the removal of pharmaceuticals from sewage treatment plants (STP). Quim. Nova 2010, 33, 411–420. [Google Scholar]

- Daughton C. G.PPCPs in the environment: Future research - beginning with the end always in mind. In Pharmaceuticals in the Environment: Sources, Fate, Effects and Risks, 2nd ed.; Kummerer K., Ed.; Springer: Berlin, 2004; pp 463–495. [Google Scholar]

- Heberer T. Occurrence, fate, and removal of pharmaceutical residues in the aquatic environment: A review of recent research data. Toxicol. Lett. 2002, 131(1–2), 5–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones O. A. H.; Voulvoulis N.; Lester J. N. Human Pharmaceuticals in Wastewater Treatment Processes. Crit. Rev. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2005, 35(4), 401–427. [Google Scholar]

- Heberer T.; Butz S.; Stan H. J. Analysis of Phenoxycarboxylic Acids and Other Acidic Compounds in Tap, Ground, Surface and Sewage Water at the Low ng/L Level. Int. J. Environ. Anal. Chem. 1995, 58(1–4), 43–53. [Google Scholar]

- Petrovic M.; Farré M.; de Alda M. L.; Perez S.; Postigo C.; Köck M.; Radjenovic J.; Gros M.; Barcelo D. Recent trends in the liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry analysis of organic contaminants in environmental samples. J. Chromatogr., A 2010, 25(1217), 4004–4017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stan H. J.; Linkerhaegner M. Identification of 2-(4-chlorophenoxy)-2-methyl-propionic acid in groundwater by capillary gas chromatography with atomic emission detection and mass spectrometry. Vom Wasser 1992, 79, 75–88. [Google Scholar]

- Kümmerer K. The presence of pharmaceuticals in the environment due to human use - Present knowledge and future challenges. J. Environ. Manage. 2009, 90(8), 2354–2366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fent K.; Weston A. A.; Caminada D. Ecotoxicology of human pharmaceuticals. Aquat. Toxicol. 2006, 76(2), 122–159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kümmerer K.Pharmaceuticals in the Environment: Sources, Fate, Effects and Risk, 3rd ed.; Springer: Berlin, 2008; p 521. [Google Scholar]

- Kümmerer K. Antibiotics in the aquatic environment - A review - Part I. Chemosphere 2009, 75, 417–434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santos L. H. M. L. M.; Araújo A. N.; Fachini A.; Pena A.; Delerue-Matos C.; Montenegro M. C. B. S. M. Ecotoxicological aspects related to the presence of pharmaceuticals in the aquatic environment. J. Hazard. Mater. 2010, 175(1–3), 45–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enick O. V.; Moore M. M. Assessing the assessments: Pharmaceuticals in the environment. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2007, 27(8), 707–729. [Google Scholar]

- Kümmerer K. Antibiotics in the aquatic environment – A review – Part II. Chemosphere 2009, 75(4), 435–441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daughton C. G. Green Pharmacy: Mini-Monograph: Cradle-to-cradle stewardship of drugs for minimizing their environmental disposition while promoting human health. I: Rationale for and avenues toward a Green Pharmacy. Environ. Health Perspect. 2003, 111(5), 757–774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- European Environment Agency. Technical report No. 1/2010: Pharmaceuticals in the Environment; EEA: Copenhagen, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Farré M. l.; Pérez S.; Kantiani L.; Barceló D. Fate and toxicity of emerging pollutants, their metabolites and transformation products in the aquatic environment. TrAC Trends Anal. Chem. 2008, 27(11), 991–1007. [Google Scholar]

- Proposal for a Directive amending the WFD and EQSD (COM(2011)876); European Commission: Brussels, 31/01/2012, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Directive 2000/60/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 23 October 2000 establishing a framework for Community action in the field of water policy. Off. J. Eur. Commun. 2000, 43, L327/1. [Google Scholar]

- Kanda R.; Griffin P.; James H. A.; Fothergill J. Pharmaceutical and personal care products in sewage treatment works. J. Environ. Monit. 2003, 5(5), 823–830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fick J.; Soderstrom H.; Lindberg R. H.; Phan C.; Tysklind M.; Larsson D. G. J. Contamination of surface, ground and drinking water from pharmaceutical production. Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 2009, 28(12), 2522–2527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li D.; Yang M.; Hu J.; Ren L.; Zhang Y.; Li K. Determination and fate of oxytetracycline and related compounds in oxytetracycline production wastewater and the receiving river. Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 2008, 27(1), 80–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kasprzyk-Hordem B.; Dinsdale R. M.; Guwy A. J. Multi-residue method for the determination of basic/neutral pharmaceuticals and illicit drugs in surface water by solid-phase extraction and ultra performance liquid chromatography-positive electrospray ionisation tandem mass spectrometry. J. Chromatogr., A 2007, 1161(1–2), 132–145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kasprzyk-Hordern B.; Dinsdale R. M.; Guwy A. J. The occurrence of pharmaceuticals, personal care products, endocrine disruptors and illicit drugs in surface water in South Wales, UK. Water Res. 2008, 42(13), 3498–3518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waiser M. J.; Humphries D.; Tumber V.; Holm J. Effluent-dominated streams. Part 2: Presence and possible effects of pharmaceuticals and personal care products in Wascana Creek, Saskatchewan, Canada. Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 2011, 30(2), 508–519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watkinson A. J.; Murby E. J.; Kolpin D. W.; Costanzo S. D. The occurrence of antibiotics in an urban watershed: From wastewater to drinking water. Sci. Total Environ. 2009, 407(8), 2711–2723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zuccato E.; Castiglioni S.; Bagnati R.; Melis M.; Fanelli R. Source, occurrence and fate of antibiotics in the Italian aquatic environment. J. Hazard. Mater. 2010, 179(1–3), 1042–1048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huerta-Fontela M.; Galceran M. T.; Ventura F. Stimulatory drugs of abuse in surface waters and their removal in a conventional drinking water treatment plant. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2008, 42(18), 6809–6816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kostich M. S.; Batt A. L.; Glassmeyer S. T.; Lazorchak J. M. Predicting variability of aquatic concentrations of human pharmaceuticals. Sci. Total Environ. 2010, 408(20), 4504–4510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vazquez-Roig P.; Andreu V.; Blasco C.; Pico Y. SPE and LC-MS/MS determination of 14 illicit drugs in surface waters from the Natural Park of L’Albufera (Valencia, Spain). Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2010, 397(7), 2851–2864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Al-Odaini N. A.; Zakaria M. P.; Yaziz M. I.; Surif S. Multi-residue analytical method for human pharmaceuticals and synthetic hormones in river water and sewage effluents by solid-phase extraction and liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry. J. Chromatogr., A 2010, 1217(44), 6791–6806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brun G. L.; Bernier M.; Losier R.; Doe K.; Jackman P.; Lee H. B. Pharmaceutically active compounds in Atlantic Canadian sewage treatment plant effluents and receiving waters, and potential for environmental effects as measured by acute and chronic aquatic toxicity. Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 2006, 25(8), 2163–2176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Camacho-Munoz D.; Martin J.; Santos J. L.; Aparicio I.; Alonso E. Occurrence, temporal evolution and risk assessment of pharmaceutically active compounds in Donana Park (Spain). J. Hazard. Mater. 2010, 183(1–3), 602–608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Camacho-Munoz M. D.; Santos J. L.; Aparicio I.; Alonso E. Presence of pharmaceutically active compounds in Donana Park (Spain) main watersheds. J. Hazard. Mater. 2010, 177(1–3), 1159–1162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Comeau F.; Surette C.; Brun G. L.; Losier R. The occurrence of acidic drugs and caffeine in sewage effluents and receiving waters from three coastal watersheds in Atlantic Canada. Sci. Total Environ. 2008, 396(2–3), 132–146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farre M.-l.; Ferrer I.; Ginebreda A.; Figueras M.; Olivella L.; Tirapu L.; Vilanova M.; Barcelo D. Determination of drugs in surface water and wastewater samples by liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry: Methods and preliminary results including toxicity studies with Vibrio fischeri. J. Chromatogr., A 2001, 938(1–2), 187–197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez C.; Gonzalez-Doncel M.; Pro J.; Carbonell G.; Tarazona J. V. Occurrence of pharmaceutically active compounds in surface waters of the Henares-Jarama-Tajo river system (Madrid, Spain) and a potential risk characterization. Sci. Total Environ. 2010, 408(3), 543–551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibson R.; Becerril-Bravo E.; Silva-Castro V.; Jimenez B. Determination of acidic pharmaceuticals and potential endocrine disrupting compounds in wastewaters and spring waters by selective elution and analysis by gas chromatography-mass spectrometry. J. Chromatogr., A 2007, 1169, 31–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kasprzyk-Hordern B.; Dinsdale R. M.; Guwy A. J. The removal of pharmaceuticals, personal care products, endocrine disruptors and illicit drugs during wastewater treatment and its impact on the quality of receiving waters. Water Res. 2009, 43(2), 363–380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matamoros V.; Arias C.; Brix H.; Bayona J. M. Preliminary screening of small-scale domestic wastewater treatment systems for removal of pharmaceutical and personal care products. Water Res. 2009, 43(1), 55–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moldovan Z. Occurrences of pharmaceutical and personal care products as micropollutants in rivers from Romania. Chemosphere 2006, 64(11), 1808–1817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng X. Z.; Yu Y. J.; Tang C. M.; Tan J. H.; Huang Q. X.; Wang Z. D. Occurrence of steroid estrogens, endocrine-disrupting phenols, and acid pharmaceutical residues in urban riverine water of the Pearl River Delta, South China. Sci. Total Environ. 2008, 397(1–3), 158–166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sim W. J.; Lee J. W.; Oh J. E. Occurrence and fate of pharmaceuticals in wastewater treatment plants and rivers in Korea. Environ. Pollut. 2010, 158(5), 1938–1947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spongberg A. L.; Witter J. D. Pharmaceutical compounds in the wastewater process stream in Northwest Ohio. Sci. Total Environ. 2008, 397(1–3), 148–157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stolker A. A. M.; Niesing W.; Hogendoorn E. A.; Versteegh J. F. M.; Fuchs R.; Brinkman U. A. T. Liquid chromatography with triple-quadrupole or quadrupole-time of flight mass spectrometry for screening and confirmation of residues of pharmaceuticals in water. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2004, 378(4), 955–963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ternes T. A. Occurrence of drugs in German sewage treatment plants and rivers. Water Res. 1998, 32(11), 3245–3260. [Google Scholar]

- Togola A.; Budzinski H. Analytical development for analysis of pharmaceuticals in water samples by SPE and GC-MS. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2007, 388(3), 627–635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verenitch S. S.; Lowe C. J.; Mazumder A. Determination of acidic drugs and caffeine in municipal wastewaters and receiving waters by gas chromatography-ion trap tandem mass spectrometry. J. Chromatogr., A 2006, 1116(1–2), 193–203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang L.; Ying G. G.; Zhao J. L.; Yang X. B.; Chen F.; Tao R.; Liu S.; Zhou L. J. Occurrence and risk assessment of acidic pharmaceuticals in the Yellow River, Hai River and Liao River of north China. Sci. Total Environ. 2010, 408(16), 3139–3147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao J. L.; Ying G. G.; Liu Y. S.; Chen F.; Yang J. F.; Wang L.; Yang X. B.; Stauber J. L.; Warne M. S. Occurrence and a screening-level risk assessment of human pharmaceuticals in the Pearl River system, South China. Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 2010, 29(6), 1377–1384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alder A. C.; Schaffner C.; Majewsky M.; Klasmeier J.; Fenner K. Fate of beta-blocker human pharmaceuticals in surface water: Comparison of measured and simulated concentrations in the Glatt Valley Watershed, Switzerland. Water Res. 2010, 44(3), 936–948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bendz D.; Paxeus N. A.; Ginn T. R.; Loge F. J. Occurrence and fate of pharmaceutically active compounds in the environment, a case study: Hoje River in Sweden. J. Hazard. Mater. 2005, 122(3), 195–204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calamari D.; Zuccato E.; Castiglioni S.; Bagnati R.; Fanelli R. Strategic survey of therapeutic drugs in the rivers Po and Lambro in northern Italy. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2003, 37(7), 1241–1248. [Google Scholar]

- Conkle J. L.; White J. R.; Metcalfe C. D. Reduction of pharmaceutically active compounds by a lagoon wetland wastewater treatment system in Southeast Louisiana. Chemosphere 2008, 73(11), 1741–1748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daneshvar A.; Svanfelt J.; Kronberg L.; Prevost M.; Weyhenmeyer G. A. Seasonal variations in the occurrence and fate of basic and neutral pharmaceuticals in a Swedish river-lake system. Chemosphere 2010, 80(3), 301–309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gros M.; Petrovic M.; Barcelo D. Wastewater treatment plants as a pathway for aquatic contamination by pharmaceuticals in the Ebro River basin (northeast Spain). Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 2007, 26(8), 1553–1562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H. X.; Helm P. A.; Metcalfe C. D. Sampling in the Great Lakes for pharmaceuticals, personal care products and endocrine-disrupting substances using the passive polar organic chemical integrative sampler. Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 2010, 29(4), 751–762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez-Roldan R.; de Alda M. L.; Gros M.; Petrovic M.; Martin-Alonso J.; Barcelo D. Advanced monitoring of pharmaceuticals and estrogens in the Llobregat River basin (Spain) by liquid chromatography-triple quadrupole-tandem mass spectrometry in combination with ultra performance liquid chromatography-time of flight-mass spectrometry. Chemosphere 2010, 80(11), 1337–1344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morasch B.; Bonvin F.; Reiser H.; Grandjean D.; de Alencastro L. F.; Perazzolo C.; Chevre N.; Kohn T. Occurrence and fate of micropollutants in the Vidy Bay of Lake Geneva, Switzerland. Part II: Micropollutant removal between wastewater and raw drinking water. Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 2010, 29(8), 1658–1668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munoz I.; Lopez-Doval J. C.; Ricart M.; Villagrasa M.; Brix R.; Geiszinger A.; Ginebreda A.; Guasch H.; de Alda M. J. L.; Romani A. M.; Sabater S.; Barcelo D. Bridging levels of pharmaceuticals in river water with biological community structure in the Llobregat river basin (northeast Spain). Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 2009, 28(12), 2706–2714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakada N.; Komori K.; Suzuki Y.; Konishi C.; Houwa I.; Tanaka H. Occurrence of 70 pharmaceutical and personal care products in Tone River basin in Japan. Water Sci. Technol. 2007, 56(12), 133–140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nodler K.; Licha T.; Bester K.; Sauter M. Development of a multi-residue analytical method, based on liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry, for the simultaneous determination of 46 micro-contaminants in aqueous samples. J. Chromatogr., A 2010, 1217(42), 6511–6521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vanderford B. J.; Snyder S. A. Analysis of pharmaceuticals in water by isotope dilution liquid chromatography/tandem mass spectrometry. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2006, 40(23), 7312–7320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vieno N. M.; Harkki H.; Tuhkanen T.; Kronberg L. Occurrence of pharmaceuticals in river water and their elimination in a pilot-scale drinking water treatment plant. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2007, 41(14), 5077–5084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vieno N. M.; Tuhkanen T.; Kronberg L. Analysis of neutral and basic pharmaceuticals in sewage treatment plants and in recipient rivers using solid phase extraction and liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry detection. J. Chromatogr., A 2006, 1134(1–2), 101–111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoon Y.; Ryu J.; Oh J.; Choi B.-G.; Snyder S. A. Occurrence of endocrine disrupting compounds, pharmaceuticals, and personal care products in the Han River (Seoul, South Korea). Sci. Total Environ. 2010, 408(3), 636–643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zuccato E.; Castiglioni S.; Fanelli R. Identification of the pharmaceuticals for human use contaminating the Italian aquatic environment. J. Hazard. Mater, 2005, 122(3), 205–209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conley J. M.; Symes S. J.; Kindelberger S. A.; Richards S. A. Rapid liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry method for the determination of a broad mixture of pharmaceuticals in surface water. J. Chromatogr., A 2008, 1185(2), 206–215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conley J. M.; Symes S. J.; Schorr M. S.; Richards S. M. Spatial and temporal analysis of pharmaceutical concentrations in the upper Tennessee River basin. Chemosphere 2008, 73(8), 1178–1187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Metcalfe C. D.; Koenig B. G.; Bennie D. T.; Servos M.; Ternes T. A.; Hirsch R. Occurrence of neutral and acidic drugs in the effluents of Canadian sewage treatment plants. Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 2003, 22(12), 2872–2880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartelt-Hunt S. L.; Snow D. D.; Damon T.; Shockley J.; Hoagland K. The occurrence of illicit and therapeutic pharmaceuticals in wastewater effluent and surface waters in Nebraska. Environ. Pollut. 2009, 157(3), 786–791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Focazio M. J.; Kolpin D. W.; Barnes K. K.; Furlong E. T.; Meyer M. T.; Zaugg S. D.; Barber L. B.; Thurman M. E. A national reconnaissance for pharmaceuticals and other organic wastewater contaminants in the United States - II) Untreated drinking water sources. Sci. Total Environ. 2008, 402(2–3), 201–216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grujic S.; Vasiljevic T.; Lausevic M. Determination of multiple pharmaceutical classes in surface and ground waters by liquid chromatography-ion trap-tandem mass spectrometry. J. Chromatogr., A 2009, 1216(25), 4989–5000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berset J. D.; Brenneisen R.; Mathieu C. Analysis of llicit and illicit drugs in waste, surface and lake water samples using large volume direct injection high performance liquid chromatography - Electrospray tandem mass spectrometry (HPLC-MS/MS). Chemosphere 2010, 81(7), 859–866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez-Marino I.; Quintana J. B.; Rodriguez I.; Cela R. Determination of drugs of abuse in water by solid-phase extraction, derivatisation and gas chromatography-ion trap-tandem mass spectrometry. J. Chromatogr., A 2010, 1217(11), 1748–1760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hummel D.; Loffler D.; Fink G.; Ternes T. A. Simultaneous determination of psychoactive drugs and their metabolites in aqueous matrices by liquid chromatography mass spectrometry. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2006, 40(23), 7321–7328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin A. Y. C.; Lin C. F.; Tsai Y. T.; Lin H. H. H.; Chen J.; Wang X. H.; Yu T. H. Fate of selected pharmaceuticals and personal care products after secondary wastewater treatment processes in Taiwan. Water Sci. Technol. 2010, 62(10), 2450–2458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Nuijs A. L. N.; Pecceu B.; Theunis L.; Dubois N.; Charlier C.; Jorens P. G.; Bervoets L.; Blust R.; Neels H.; Covaci A. Spatial and temporal variations in the occurrence of cocaine and benzoylecgonine in waste- and surface water from Belgium and removal during wastewater treatment. Water Res. 2009, 43(5), 1341–1349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zuccato E.; Chiabrando C.; Castiglioni S.; Bagnati R.; Fanelli R. Estimating community drug abuse by wastewater analysis. Environ. Health Perspect. 2008, 116(8), 1027–1032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Comoretto L.; Chiron S. Comparing pharmaceutical and pesticide loads into a small Mediterranean river. Sci. Total Environ. 2005, 349(1–3), 201–210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hao C. Y.; Zhao X. M.; Tabe S.; Yang P. Optimization of a multiresidual method for the determination of waterborne emerging organic pollutants using solid-phase extraction and liquid chromatography/tandem mass spectrometry and isotope dilution mass spectrometry. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2008, 42(11), 4068–4075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hua W. Y.; Bennett E. R.; Maio X. S.; Metcalfe C. D.; Letcher R. J. Seasonality effects on pharmaceuticals and s-triazine herbicides in wastewater effluent and surface water from the Canadian side of the upper Detroit River. Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 2006, 25(9), 2356–2365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindqvist N.; Tuhkanen T.; Kronberg L. Occurrence of acidic pharmaceuticals in raw and treated sewages and in receiving waters. Water Res. 2005, 39(11), 2219–2228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loos R.; Gawlik B. M.; Locoro G.; Rimaviciute E.; Contini S.; Bidoglio G. EU-wide survey of polar organic persistent pollutants in European river waters. Environ. Pollut. 2009, 157(2), 561–568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loos R.; Wollgast J.; Huber T.; Hanke G. Polar herbicides, pharmaceutical products, perfluorooctanesulfonate (PFOS), perfluorooctanoate (PFOA), and nonylphenol and its carboxylates and ethoxylates in surface and tap waters around Lake Maggiore in Northern Italy. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2007, 387(4), 1469–1478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radke M.; Ulrich H.; Wurm C.; Kunkel U. Dynamics and attenuation of acidic pharmaceuticals along a river stretch. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2010, 44(8), 2968–2974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vieno N. M.; Tuhkanen T.; Kronberg L. Seasonal variation in the occurrence of pharmaceuticals in effluents from a sewage treatment plant and in the recipient water. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2005, 39(21), 8220–8226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weigel S.; Berger U.; Jensen E.; Kallenborn R.; Thoresen H.; Huhnerfuss H. Determination of selected pharmaceuticals and caffeine in sewage and seawater from Tromso/Norway with emphasis on ibuprofen and its metabolites. Chemosphere 2004, 56(6), 583–592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alvarez D. A.; Stackelberg P. E.; Petty J. D.; Huckins J. N.; Furlong E. T.; Zaugg S. D.; Meyer M. T. Comparison of a novel passive sampler to standard water-column sampling for organic contaminants associated with wastewater effluents entering a New Jersey stream. Chemosphere 2005, 61(5), 610–622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benotti M. J.; Brownawell B. J. Distributions of pharmaceuticals in an urban estuary during both dry- and wet-weather conditions. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2007, 41(16), 5795–5802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen H. C.; Wang P. L.; Ding W. H. Using liquid chromatography-ion trap mass spectrometry to determine pharmaceutical residues in Taiwanese rivers and wastewaters. Chemosphere 2008, 72(6), 863–869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi K.; Kim Y.; Park J.; Park C. K.; Kim M.; Kim H. S.; Kim P. Seasonal variations of several pharmaceutical residues in surface water and sewage treatment plants of Han River, Korea. Sci. Total Environ. 2008, 405(1–3), 120–128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrer I.; Zweigenbaum J. A.; Thurman E. M. Analysis of 70 Environmental Protection Agency priority pharmaceuticals in water by EPA Method 1694. J. Chromatogr., A 2010, 1217(36), 5674–5686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gasser G.; Rona M.; Voloshenko A.; Shelkov R.; Tal N.; Pankratov I.; Elhanany S.; Lev O. Quantitative Evaluation of Tracers for Quantification of Wastewater Contamination of Potable Water Sources. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2010, 44(10), 3919–3925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glassmeyer S. T.; Furlong E. T.; Kolpin D. W.; Cahill J. D.; Zaugg S. D.; Werner S. L.; Meyer M. T.; Kryak D. D. Transport of chemical and microbial compounds from known wastewater discharges: Potential for use as indicators of human fecal contamination. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2005, 39(14), 5157–5169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hao C. Y.; Lissemore L.; Nguyen B.; Kleywegt S.; Yang P.; Solomon K. Determination of pharmaceuticals in environmental waters by liquid chromatography/electrospray ionization/tandem mass spectrometry. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2006, 384(2), 505–513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hua W. Y.; Bennett E. R.; Letcher R. J. Ozone treatment and the depletion of detectable pharmaceuticals and atrazine herbicide in drinking water sourced from the upper Detroit River, Ontario, Canada. Water Res. 2006, 40(12), 2259–2266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kahle M.; Buerge I. J.; Muller M. D.; Poiger T. Hydrophilic anthropogenic markers for quantification of wastewater contamination in ground and surface waters. Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 2009, 28(12), 2528–2536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim S. D.; Cho J.; Kim I. S.; Vanderford B. J.; Snyder S. A. Occurrence and removal of pharmaceuticals and endocrine disruptors in South Korean surface, drinking, and waste waters. Water Res. 2007, 41(5), 1013–1021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kolpin D. W.; Skopec M.; Meyer M. T.; Furlong E. T.; Zaugg S. D. Urban contribution of pharmaceuticals and other organic wastewater contaminants to streams during differing flow conditions. Sci. Total Environ. 2004, 328(1–3), 119–130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lissemore L.; Hao C. Y.; Yang P.; Sibley P. K.; Mabury S.; Solomon K. R. An exposure assessment for selected pharmaceuticals within a watershed in southern Ontario. Chemosphere 2006, 64(5), 717–729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madureira T. V.; Barreiro J. C.; Rocha M. J.; Rocha E.; Cass Q. B.; Tiritan M. E. Spatiotemporal distribution of pharmaceuticals in the Douro River estuary (Portugal). Sci. Total Environ. 2010, 408(22), 5513–5520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magner J.; Filipovic M.; Alsberg T. Application of a novel solid-phase-extraction sampler and ultra-performance liquid chromatography quadrupole-time-of-flight mass spectrometry for determination of pharmaceutical residues in surface sea water. Chemosphere 2010, 80(11), 1255–1260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moldovan Z.; Chira R.; Alder A. C. Environmental exposure of pharmaceuticals and musk fragrances in the Somes River before and after upgrading the municipal wastewater treatment plant Cluj-Napoca, Romania. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2009, 16, 46–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Musolff A.; Leschik S.; Schafmeister M. T.; Reinstorf F.; Strauch G.; Krieg R.; Schirmer M. Evaluation of xenobiotic impact on urban receiving waters by means of statistical methods. Water Sci. Technol. 2010, 62(3), 684–692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakada N.; Kiri K.; Shinohara H.; Harada A.; Kuroda K.; Takizawa S.; Takada H. Evaluation of pharmaceuticals and personal care products as water-soluble molecular markers of sewage. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2008, 42(17), 6347–6353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ollers S.; Singer H. P.; Fassler P.; Muller S. R. Simultaneous quantification of neutral and acidic pharmaceuticals and pesticides at the low-ng/L level in surface and waste water. J. Chromatogr., A 2001, 911(2), 225–234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rabiet M.; Togola A.; Brissaud F.; Seidel J. L.; Budzinski H.; Elbaz-Poulichet F. Consequences of treated water recycling as regards pharmaceuticals and drugs in surface and ground waters of a medium-sized Mediterranean catchment. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2006, 40(17), 5282–5288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stackelberg P. E.; Furlong E. T.; Meyer M. T.; Zaugg S. D.; Henderson A. K.; Reissman D. B. Persistence of pharmaceutical compounds and other organic wastewater contaminants in a conventional drinking-water treatment plant. Sci. Total Environ. 2004, 329(1–3), 99–113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Standley L. J.; Rudel R. A.; Swartz C. H.; Attfield K. R.; Christian J.; Erickson M.; Brody J. G. Wastewater-contaminated groundwater as a source of endogenous hormones and pharmaceuticals to surface water ecosystems. Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 2008, 27(12), 2457–2468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stolker A. A. M.; Niesing W.; Fuchs R.; Vreeken R. J.; Niessen W. M. A.; Brinkman U. A. T. Liquid chromatography with triple-quadrupole and quadrupole-time-of-flight mass spectrometry for the determination of micro-constituents - A comparison. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2004, 378(7), 1754–1761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tixier C.; Singer H. P.; Oellers S.; Muller S. R. Occurrence and fate of carbamazepine, clofibric acid, diclofenac, ibuprofen, ketoprofen, and naproxen in surface waters. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2003, 37(6), 1061–1068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu C. X.; Witter J. D.; Spongberg A. L.; Czajkowski K. P. Occurrence of selected pharmaceuticals in an agricultural landscape, western Lake Erie basin. Water Res. 2009, 43(14), 3407–3416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]