Abstract

Background

The performance in master marathoners has been investigated in flat city marathons but not in mountain marathons. This study examined changes in the sex differences in performance across time in female and male master runners competing in a mountain marathon compared to a flat city marathon.

Methods

The association between age and performance of finishers in the Jungfrau Marathon, Switzerland, with 1830 meter changes in altitude and a flat city marathon (Lausanne Marathon), Switzerland, were analyzed from 2000 to 2011.

Results

In both events, athletes in the 35–44 years age group showed the highest number of finishers. In the mountain marathon, the number of female master runners aged > 35 years increased in contrast to female finishers aged < 35 years, while the number of male finishers was unchanged in all age groups. In the city marathon, the number of female finishers was unchanged while the number of male finishers in the age groups for 25–34-year-olds and 35–44-year-olds decreased. In female marathoners, performance improved in athletes aged 35–44 and 55–64 years in the city marathon. Male marathoners improved race time in age group 45–54 years in both the city marathon and the mountain marathon. Female master runners reduced the sex difference in performance in the 45–54-year age group in both competitions and in the 35–44-year age group in the mountain marathon. The sex difference in performance decreased in the 35–44-year age group from 19.1% ± 4.7% to 16.6% ± 1.9% in the mountain marathon (r2 = 0.39, P = 0.03). In age groups 45–54 years, the sex difference decreased from 23.4% ± 1.9% to 15.9% ± 6.1% in the mountain marathon (r2 = 0.39, P < 0.01) and from 34.7% ± 4.6% to 11.8% ± 6.2% in the city marathon (r2 = 0.39, P < 0.01).

Conclusion

These findings suggest that female master runners aged 35–54 years reduced sex differences in their performance in both mountain and city marathon running.

Keywords: endurance, age, female, male

Introduction

Marathon running became a mass fitness phenomenon in the 1980s.1 Recent studies reported that master runners increased participation and improved performance in flat city marathon running, such as in the New York City Marathon.2,3 Master runners were defined as athletes typically older than 35 years of age and systematically training for and competing in organized forms of sport specifically designed for older adults.4 An age-related decrease in the number of finishers in master sports has been reported.5 However, the community of master runners is still growing quickly in marathons;3 conversely, the number of younger participants increased at a lower rate.2

Older master athletes are able to achieve exceptional performances. For example, the Canadian marathoner Ed Whitlock achieved, at the age of 80 years, a marathon race time of 3 hours, 15 minutes, and 54 seconds at the Toronto marathon held in 2011.6 In 2009, an 86-year-old man became a double champion in the European championship for road running. He won the 10 km road run with a time of 58 minutes and 1 second, setting a new European record for men aged 85 years and older. Two days later, he became a European champion in the same age group for the half-marathon, with a time of 2 hours and 17 minutes.7

Several studies investigated participation and performance trends in master ultramarathoners where participation increased and performance improved.8,9 In marathon running, a few studies focused on the number of finishers and the performance in master marathoners competing in flat city marathons.2,3,10 The number of finishers in master runners increased at a higher rate than the number of younger marathoners,3 and their performances improved over time.2,3 Lepers and Cattagni3 showed an increase in performance for men older than 64 years and for women older than 44 years, competing between 1980 and 2009 in the New York City Marathon. Participation and performance trends for master runners in a city marathon, such as the New York City Marathon, have been investigated,2,3 but are not known for master runners competing in a mountain marathon. Apart from city marathon running,11 mountain marathon running is increasing in popularity.12

We intended to investigate whether the number and the performance of master runners would be similar in a mountain marathon when compared to a flat city marathon. Because of the selection bias (ie, starting places not being freely available for everyone in some of the major marathons, such as the New York City Marathon), we intended to compare a mountain marathon (Jungfrau Marathon) with a flat city marathon (Lausanne Marathon) with no limitation on the number of starters, and which were held in the same country (Switzerland) between 2000 and 2011, regarding changes in participation and performance trends in master runners. We hypothesized for both races that: (1) the number of master runners would increase; and (2) the performance of master runners would improve over the years.

Methods

Race times and ages of all finishers in the Jungfrau Marathon and the Lausanne Marathon between 2000 and 2011 were analyzed. The data were obtained from the race websites of the Jungfrau Marathon and the Lausanne Marathon.13,14 The Jungfrau Marathon was selected as the mountain marathon since this race was held in 2007 and 2012 as the official World Championship in mountain running. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of St Gallen, Switzerland, with a waiver of the requirement for informed consent, given that the study involved the analysis of publicly available data.

Races

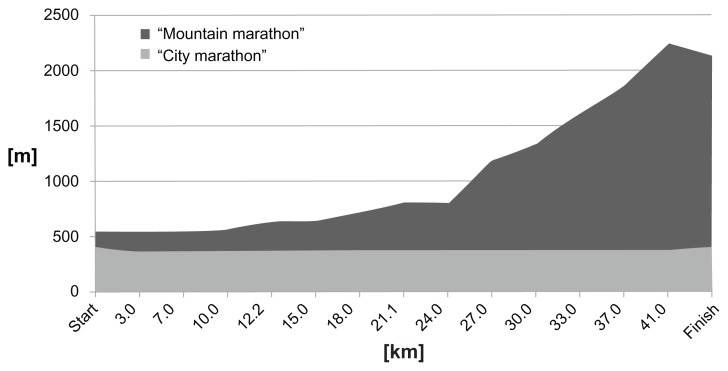

The Jungfrau Marathon in Switzerland was established in 1993 and is one of the most popular mountain marathons in the world.13 The race is held annually with the start in Interlaken (565 meters (m) above sea level) and the finish at the Kleine Scheidegg (2095 m above sea level). It covers an overall ascent of 1830 m and an overall descent of 305 m. The first quarter of the race is mostly flat and in the first half of the race the athletes had no more ascent than 300 m in the half-marathon distance (Figure 1). The Lausanne Marathon was established in 1992 and is the second most important Swiss city marathon following the Zürich Marathon.14 The race is held annually in autumn in Lausanne on the border of Lake Léman with 36 m of altitude change (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Course profiles of the Lausanne Marathon and Jungfrau Marathon.

Notes: Lausanne Marathon, shown as “city marathon,” is in light gray. Jungfrau Marathon, shown as “mountain marathon,” is in dark gray.

Abbreviations: m, meter; km, kilometer.

Data analyses

Data from 43,636 runners (including 7567 [17.3%] women and 36,069 [82.7%] men) who finished the Jungfrau Marathon between 2000 and 2011, and 20,464 runners (including 3104 [15.2%] women and 17,360 [84.8%] men) who finished the Lausanne Marathon between 2000 and 2011 were available. To analyze the performance in age groups, all athletes were divided in 10-year age groups: 15–24 years, 25–34 years, 35–44 years, 45–54 years, 55–64 years, 65–74 years, and 75–84 years. To calculate the performance ratio and sex differences from each age group, the annual top ten women and men were determined. Only those age groups with at least ten finishers in both sexes in at least eleven out of the twelve analyzed years were included. Due to the low number of finishers per age group, only athletes in the 25–34-year and 55–64-year age groups could be included in the data analysis. The performance ratio for both sexes and the sex differences in performance were calculated per age group and year, and these were subsequently analyzed regarding their change over time. The performance ratio was calculated using the equation:

| (1) |

The performance ratio expresses the performance of the top ten athletes of an age group as a percentage of the performance of the overall top ten athletes and is a good indicator of the age-related decline in performance.3 The sex difference in performance was calculated using the equation:

| (2) |

where the sex difference was calculated for every pairing of equally placed athletes (eg, between female and male first place, between female and male second place, and so on) before calculating the mean value and standard deviation of all the pairings. To facilitate reading, all sex differences were transformed into absolute values before analyzing.

Statistical analysis

To increase the reliability of the data analyses, each set of data was tested for normal distribution as well as for the homogeneity of variances in advance of the statistical analyses. Normal distribution was tested using the D’Agostino–Pearson omnibus normality test, and the homogeneity of variances was tested using Levene’s test. To find significant changes in the development of a variable across years, linear regression was used. To find significant differences between two groups in case of normal distributed data, a Student’s t-test was used with Welch’s correction in case of significant different variances between the two compared groups. In case of not normal distributed data, the Mann–Whitney test was used. Statistical analyses were performed using the IBM Statistical Package for the Social Sciences version 19 (SPSS; IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY, USA) and GraphPad Prism Version 5 (GraphPad Software Inc, La Jolla, CA, USA). Significance was accepted at P < 0.05 (two-sided for t-tests). Data in the text are given as mean ± standard deviation.

Results

Participation trends

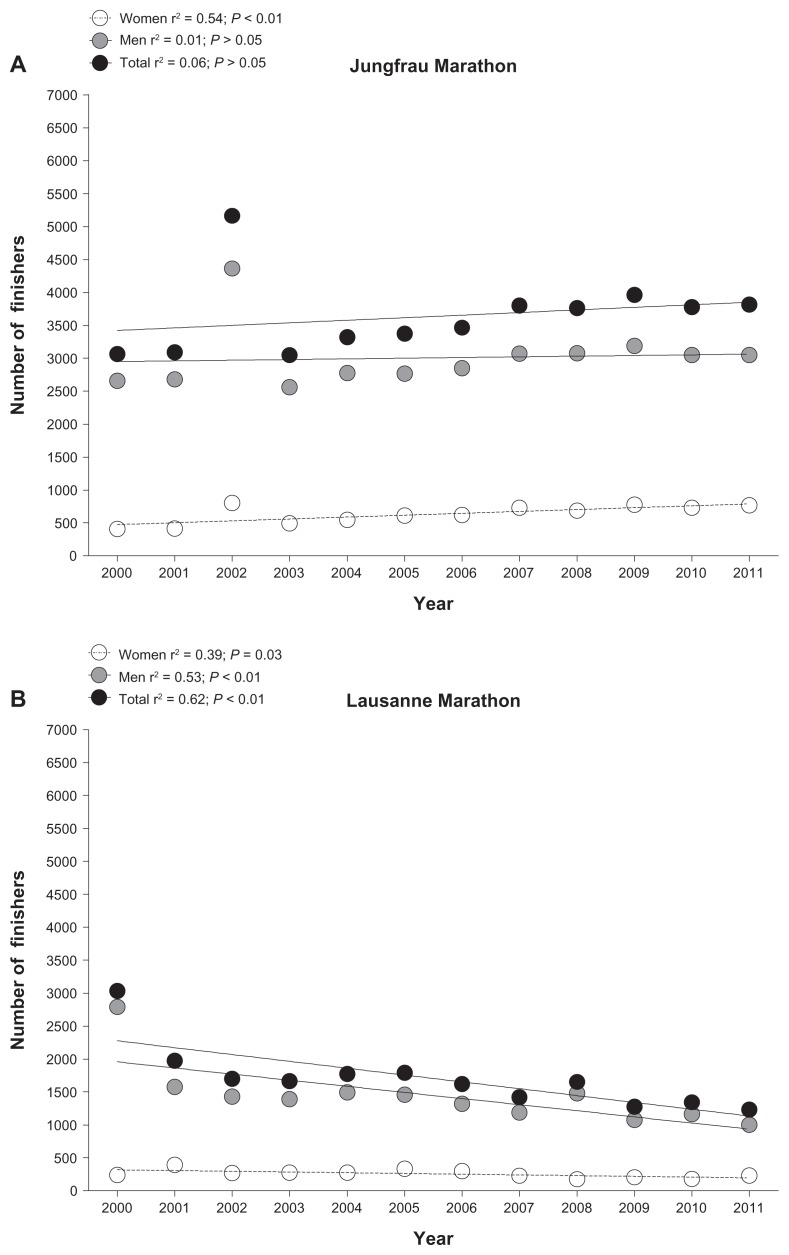

The number of finishers in the mountain marathon remained unchanged over the 12-year period (Figure 2A), whereas the number of finishers in the city marathon decreased (Figure 2B). In the mountain marathon, the number of women accounted for 17.3% of the total field, while they accounted for 15.2% in the city marathon. There was a significant increase in the number of female finishers in the Jungfrau Marathon (Figure 2A), but there was a decrease in the Lausanne Marathon (Figure 2B). The number of male finishers showed no change in the Jungfrau Marathon compared to a decrease in the Lausanne Marathon.

Figure 2.

Number of female and male finishers in the Jungfrau Marathon and in the Lausanne Marathon. (A) Jungfrau Marathon results are depicted; (B) Lausanne Marathon results are depicted.

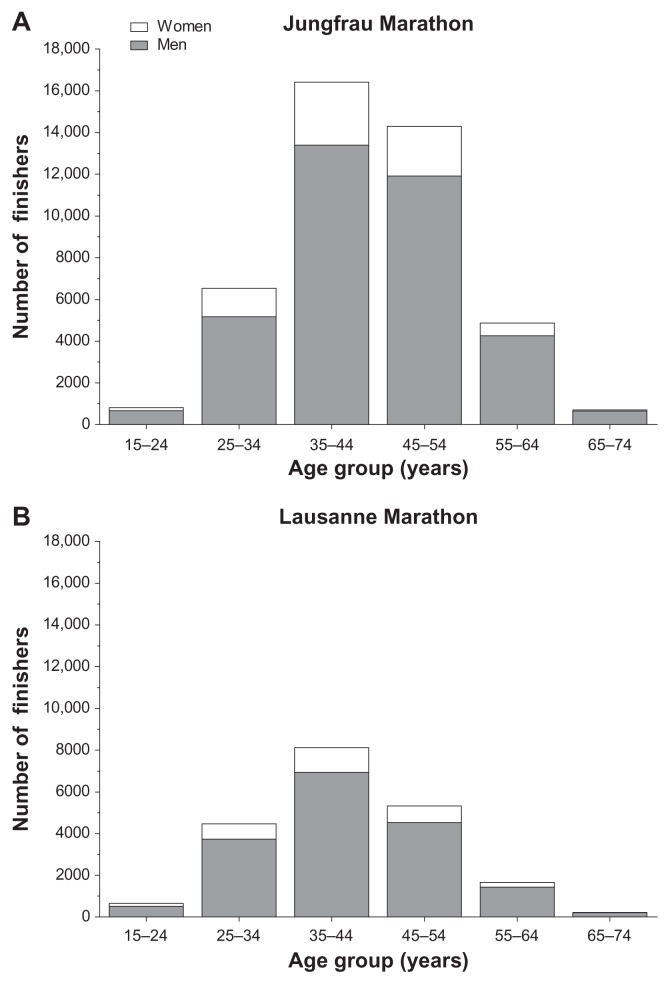

In both events, athletes in the 35–44 age group showed the highest number of finishers for both women and men (Figure 3). In the mountain marathon, the number of female master runners aged > 34 years increased in contrast to female finishers aged < 35 years (Figure 4A), while the number of male finishers was constant in all age groups (Figure 4B). In the city marathon, the number of female finishers was constant while the number of male finishers in the age groups of 25–34 and 35–44 years decreased.

Figure 3.

Number of female and male athletes per age group in the Jungfrau Marathon and in the Lausanne Marathon. (A) Jungfrau Marathon results are depicted; (B) Lausanne Marathon results are depicted.

Figure 4.

Number of finishers in the different age groups for women and men. (A) Women; (B) men.

Note: r2 and P-values are indicated in the case of a significant change in sex difference over time.

Performance trends

For the top ten women and the top ten men in the Jungfrau Marathon (the mountain marathon), the overall running speed remained stable. In the Lausanne Marathon (the city marathon), the overall top ten women maintained their running speed. However, the overall top ten men became significantly slower as their running time increased by 8%, from 139.8 minutes ± 2.4 minutes (2000) to 151.1 minutes ± 6.4 minutes (2011).

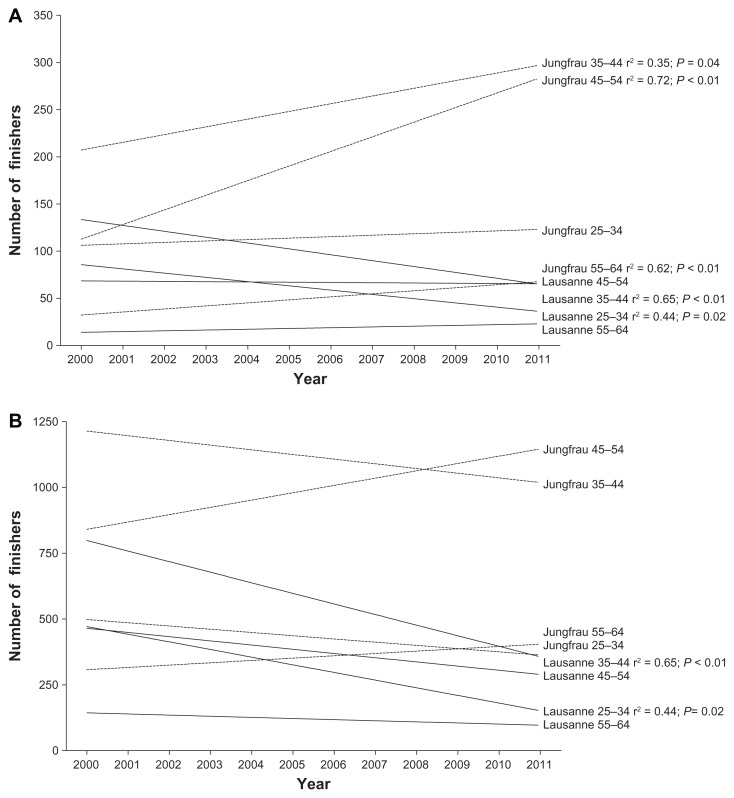

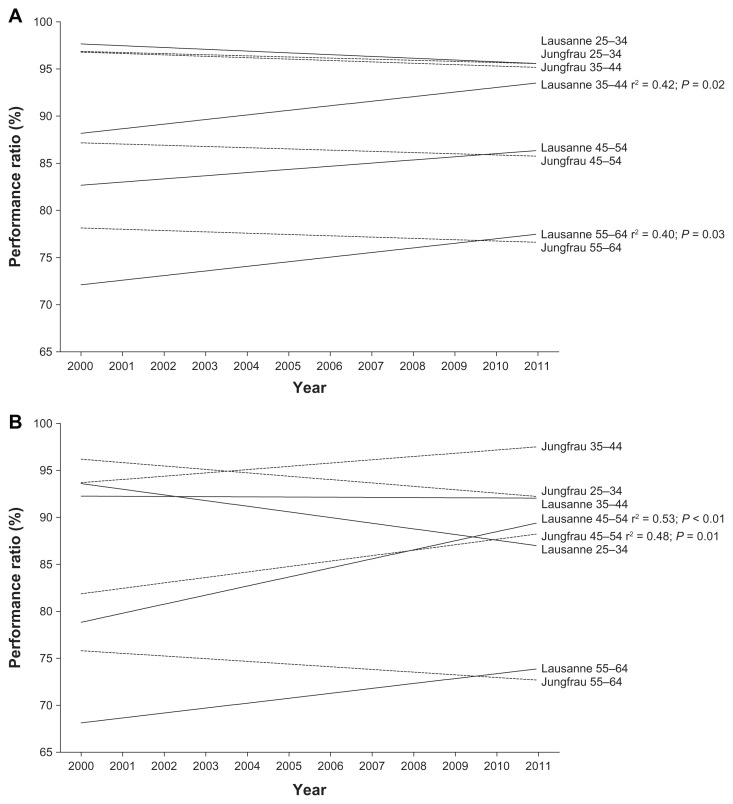

Figure 5 presents the changes in performance ratio for age group runners. In female marathoners, performance improved in athletes aged 35–44 years and 55–64 years in the city marathon (Lausanne Marathon). Male marathoners’ race times improved in the 45–54-year age group in both the city marathon (Lausanne Marathon) and in the mountain marathon (Jungfrau Marathon). The analysis of the interaction between the type of competition and age group showed a significant interaction for women (F = 5.7; P < 0.0001), where the type of competition accounted for 35.3% (F = 1232.5, P < 0.0001) and age group accounted for 58.4% (F = 224.9, P < 0.0001) of the total variance. For men, the type of competition and age group showed a significant interaction (F = 9.3; P < 0.0001), where the type of competition accounted for 52.4% (F = 2028.7, P < 0.0001) and age group for 41.2% (F = 178.4, P < 0.0001) of the total variance.

Figure 5.

Changes in the performance ratio per age group per sex across the years. (A) Women; (B) Men.

Notes: Performance ratio is expressed as the percentage of performances of the overall top ten athletes in their respective marathon years. r2 and P-values are indicated in the case of a significant change in performance ratio over time.

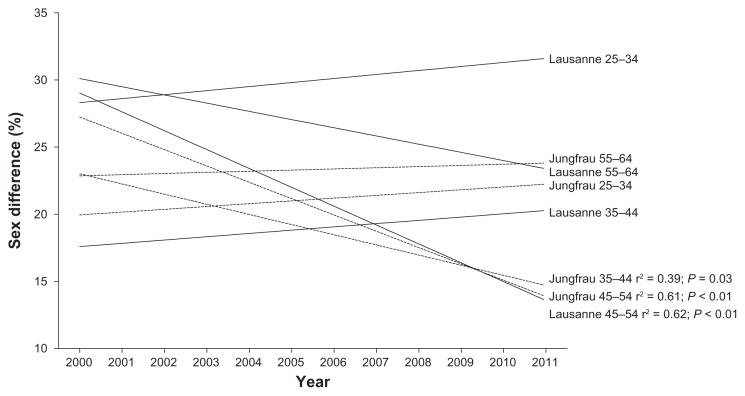

Figure 6 presents the changes in sex difference over time. Female runners reduced sex differences in performance in the 45–54-year age group in both competitions and in the 35–44-year age group in the mountain marathon (Jungfrau Marathon). In the mountain marathon (Jungfrau Marathon), the sex difference in the performance of the 45–54-year age group decreased from 23.4% ± 1.9% (2000) to 15.9% ± 6.1% (2011) in the mountain marathon and from 34.7% ± 4.6% to 11.8% ± 6.2% in the city marathon (Lausanne Marathon). In the mountain marathon, the sex difference of the 35–44-year age group decreased from 19.1% ± 4.7% (2000) to 16.6% ± 1.9% (2011). The interaction analysis between the type of competition and age group on running speed showed significant interaction in terms of sex differences (F = 8.64; P < 0.0001), where the type of competition and age group accounted for 71.8% of the total variance, and age group alone accounted for 71.7% (F = 72.90; P < 0.0001) of the total variance. The type of competition accounted for less than 0.01% of the total variance (F = 0.02; P = 0.90) and was insignificant.

Figure 6.

Changes in sex difference in running performance per age group across the years.

Note: r2 and P-values are indicated in the case of a significant change in sex difference over time.

Discussion

This study intended to compare participation and performance trends in runners of various age groups competing in a mountain marathon and a flat city marathon in the same country where the race director set no limit in the number of starters (in contrast to other marathons where the field is limited). We hypothesized for both races that: (1) the number of master runners would increase; and (2) the performance of master runners would improve over the years.

In the mountain marathon, the number of female finishers increased in every age group of master runners; the number of male finishers, however, remained constant. Eichenberger et al15 reported similar findings for mountain ultramarathoners, showing that the number of female finishers increased from 2000 to 2011 in the Swiss Alpine Marathon, whereas the number of male finishers remained unchanged. Only the number of master runners increased while the number of younger finishers (ie, <35 years old) remained constant. However, in the city marathon, the number of younger finishers (ie, <45 years old) decreased while the number of older male finishers was constant. A possible explanation might be that since the beginning of the Lausanne Marathon in 1992, an abundance of newer and larger city marathons has been offered in Switzerland, including the Zürich Marathon and others that have taken place abroad; therefore, runners now have a wider spectrum of competitions to choose from.11

Considering the performance of athletes based on age group, an important finding was that there was an increase in the performance ratio for female master runners aged 35–44 years and 55–64 years in the city marathon and for male master runners aged 45–54 years in both the city and the mountain marathons. Marathoners in younger age groups, however, showed no improvements in performance in either marathon. Therefore, it seemed that female athletes in the mountain marathon reached their peak running speed and their performance may not improve anymore in the near future. Conversely, in the city marathon, women improved in the 35–44 and 55–64 age groups. Jokl et al2 reported an improvement in running speed for master runners at a faster rate than younger athletes in the New York City Marathon from 1983–1999, which is consistent with our findings in the city marathon for men.

A possible explanation for the improvement of male master runners in the city marathon might be that the top ten men became significantly slower over the years. Therefore, even maintenance of running speed in master runners might have resulted in a relative improvement among the top ten runners in their respective marathon years. The finding that female master runners exhibited improved performances in city marathon running was consistent with the findings of Lepers and Cattagni,3 who reported a significant increase in running speed in women older than 45 years. While men between 45 and 54 years of age could improve their running speed in both a mountain and a city marathon, age-matched women could not. Women were able to improve race times in the city marathon in age groups 35–44 years and 55–64 years. Women seemed to have reached their peak running speed in mountain marathon running, but this was increasingly true for the younger (ie, <44 years old) runners than for older runners. In the mountain marathon, the sex difference in the of 25–29-year age group was 15.4% ± 1.7%, while the difference in the 60–64-year age group was 20.4% ± 2.1%, which was consistent with the findings in the study by Hunter and Stevens,16 where the authors noted that the sex differences of running speed increased with advancing age in the New York City Marathon.

No changes in sex difference for running times were found between the top ten women and the top ten men in both races. Nevertheless, significant changes in the sex differences in running times in male athletes in the 45–54-year age group were found for both races. Additionally, the sex difference decreased in the 35–44-year age group in runners from the mountain marathon. These findings suggest that female master runners older than 35 years reduced the sex difference in performance observed in both mountain and city marathon running. Studies concerning the sex differences in running exist for elite athletes and for recreational runners.15,17–20 The sex difference in endurance performance (ie, running speed) was a frequently discussed topic,21,22 and it was found to be existent in different sports disciplines.23 Twenty years ago, Whipp and Ward22 hypothesized that women would achieve the performance of men depending upon the distance. Existing findings show that women are unlikely to be able to outrun men in the near future, as the average difference in running speed between men and women decreased for a long time but leveled in recent years.24 Cheuvront et al24 reported a sex difference of 8%–14% for running distances from 1500 m to 42 km, whereas the sex difference in running speed was on average about 11% in other competitions.18,21 Lepers and Cattagni3 showed relatively stable sex differences in marathon running times across the different age groups for the last decade in the New York City Marathon.

Considering the sex difference in performance, the interaction between the type of competition and running time was insignificant, and the sex difference in running speed was therefore independent from the type of competition. The time difference between sexes was constant over the years, while the sex difference was smaller between the mountain marathon runners compared to the city marathon runners. The fastest female runner was about 16% slower in the mountain marathon and approximately 18% slower in the city marathon compared to the top ten women in the mountain marathon, with approximately 19% difference in running speed and approximately 22% in the city marathon. Cheuvront et al24 similarly found that the sex difference in performance was constant but smaller at around 8%–14% in competitions ranging from 1500 m to the marathon distance.24 In longer distances, Coast et al25 reported a mean sex difference of 12.4% over distances ranging from 100 m to 200 km. The difference in running speed between winners and the top ten runners can be partly explained by the lower number of female finishers and, therefore, the faster decline in performance in women.

We found a highly significant interaction between the type of competition and the age of the top ten runners. To the best of our knowledge, there was never a direct comparison between a mountain and a city marathon in terms of running times and age. Nevertheless, other studies suggested that the type of competition and the age of the top ten runners were directly related. Eichenberger et al15 found that there was a mean age of approximately 35 years for the top ten runners over the time span of 14 years at the Swiss Alpine Marathon held in Davos, Switzerland.15 Conversely, in city marathon running, the average age of runners was reported to be at around 30 years for both women and men.18,26 Since these two types of competitions were not directly compared, our results cannot be definitively supported by these findings.

Limitations and implications for future research

This study is limited since variables such as physiological parameters,27 anthropometric characteristics,20,28,29 training characteristics,20,28,30,31 previous experience,32 nutrition,33 and weather were not considered.34 It would be of interest to compare the same women and men competing in both the city and the mountain marathon. Female marathoners with lower body mass and lower body mass index compared to male marathoners might hold an advantage and achieve relatively faster race times.30,31

Conclusion

To summarize, the number of female master runners increased in the mountain marathon. The sex difference in performance decreased in the 35–44-year age group in the mountain marathon. In runners aged 45–54 years, the sex difference decreased in the mountain marathon and in the city marathon. These findings suggest that female master runners reduced the sex difference in performance in both mountain and city marathon running.

Footnotes

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.Burfoot A. The history of the marathon: 1976-present. Sports Med. 2007;37(4–5):284–287. doi: 10.2165/00007256-200737040-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jokl P, Sethi PM, Cooper AJ. Master’s performance in the New York City Marathon 1983–1999. Br J Sports Med. 2004;38(4):408–412. doi: 10.1136/bjsm.2002.003566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lepers R, Cattagni T. Do older athletes reach limits in their performance during marathon running? Age (Dordr) 2012;34(3):773–781. doi: 10.1007/s11357-011-9271-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Reaburn P, Dascombe B. Endurance performance in masters athletes. Eur Rev Aging Phys Act. 2008;5:31–42. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wright VJ, Perricelli BC. Age-related rates of decline in performance among elite senior athletes. Am J Sports Med. 2008;36(3):443–450. doi: 10.1177/0363546507309673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lepers R, Stapley PJ, Cattagni T, Gremeaux V, Knechtle B. Limits in endurance performance of octogenarian athletes. J Appl Physiol. 2013;114(6):829. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00038.2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Knechtle B, Kohler G, Rosemann T. Study of a European male champion in 10-km road races in the age group > 85 years. Proc (Bayl Univ Med Cent) 2010;23(3):259–260. doi: 10.1080/08998280.2010.11928630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zingg M, Rüst CA, Rosemann T, Lepers R, Knechtle B. Master runners dominate the 24-hour ultramarathons worldwide – a retrospective data analysis from 1998 to 2011. Extreme Physiology and Medicine. doi: 10.1186/2046-7648-2-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zingg M, Rüst CA, Knechtle B, Rosemann T, Lepers R. Analysis of participation and performance in age group athletes in ultramarathons of more than 200 km in length. Int J Gen Med. doi: 10.2147/IJGM.S43454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Leyk D, Erley O, Ridder D, et al. Age-related changes in marathon and half-marathon performances. Int J Sports Med. 2007;28(6):513–517. doi: 10.1055/s-2006-924658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Web Marketing Associates. live2run™ Marathon guide.com [homepage on the Internet] New York, NY: Web Marketing Associates; 2013. [Accessed April 14, 2012]. Available from: http://www.marathonguide.com. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rose D. Your backcountry trail running/ultra running resource [homepage on the Internet] Park City, UT: BackcountryRunner.com; 2012. [Accessed March 27, 2012]. Available from: http://www.backcountryrunner.com. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Verein Jungfrau Marathon. Verein Jungfrau-Marathon [homepage on the Internet] Interlaken, Switzerland: Verein Jungfrau Marathon; 2013. [Accessed April 14, 2012]. Available from: http://www.jungfrau-marathon.ch. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lausanne Marathon. Lausanne Marathon [homepage on the Internet] Lausanne, Switzerland: Lausanne Marathon; 2013. [Accessed April 14, 2012]. Available from: http://www.lausanne-marathon.com. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Eichenberger E, Knechtle B, Rüst CA, Rosemann T, Lepers R. Age and sex interactions in mountain ultramarathon running – the Swiss Alpine Marathon. Open Access Journal of Sports Medicine. 2012;3:73–80. doi: 10.2147/OAJSM.S33836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hunter SK, Stevens AA. Sex differences in marathon running with advanced age: physiology or participation? Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2013;45(1):148–156. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0b013e31826900f6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Baker AB, Tang YQ. Aging performance for masters records in athletics, swimming, rowing, cycling, triathlon, and weightlifting. Exp Aging Res. 2010;36(4):453–477. doi: 10.1080/0361073X.2010.507433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hunter SK, Stevens AA, Magennis K, Skelton KW, Fauth M. Is there a sex difference in the age of elite marathon runners? Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2011;43(4):656–664. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0b013e3181fb4e00. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pate RR, O’Neill JR. American women in the marathon. Sports Med. 2007;37(4–5):294–298. doi: 10.2165/00007256-200737040-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Knechtle B, Knechtle P, Barandun U, Rosemann T, Lepers R. Predictor variables for half marathon race time in recreational female runners. Clinics (Sao Paulo) 2011;66(2):287–291. doi: 10.1590/S1807-59322011000200018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Thibault V, Guillaume M, Berthelot G, et al. Women and men in sport performance: the gender gap has not evolved since 1983. J Sports Sci Med. 2010;9:214–223. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Whipp BJ, Ward SA. Will women soon outrun men? Nature. 1992;355(6355):25. doi: 10.1038/355025a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Medic N, Young BW, Starkes JL, Weir PL, Grove JR. Gender, age, and sport differences in relative age effects among US Masters swimming and track and field athletes. J Sports Sci. 2009;27(14):1535–1544. doi: 10.1080/02640410903127630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cheuvront SN, Carter R, Deruisseau KC, Moffatt RJ. Running performance differences between men and women: an update. Sports Med. 2005;35(12):1017–1024. doi: 10.2165/00007256-200535120-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Coast JR, Blevins JS, Wilson BA. Do gender differences in running performance disappear with distance? Can J Appl Physiol. 2004;29(2):139–145. doi: 10.1139/h04-010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schulz R, Curnow C. Peak performance and age among superathletes: track and field, swimming, baseball, tennis, and golf. J Gerontol. 1988;43(5):P113–P120. doi: 10.1093/geronj/43.5.p113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Billat VL, Demarle A, Slawinski J, Paiva M, Koralsztein JP. Physical and training characteristics of top-class marathon runners. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2001;33(12):2089–2097. doi: 10.1097/00005768-200112000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Knechtle B, Knechtle P, Rosemann T. Race performance in male mountain ultramarathoners: anthropometry or training? Percept Mot Skills. 2010;110(3 Pt 1):721–735. doi: 10.2466/PMS.110.3.721-735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Knechtle B, Rüst CA, Knechtle P, Rosemann T. Does muscle mass affect running performance in male long-distance master runners? Asian J Sports Med. 2012;3(4):247–256. doi: 10.5812/asjsm.34547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schmid W, Knechtle B, Knechtle P, et al. Predictor variables for marathon race time in recreational female runners. Asian J Sports Med. 2012;3(2):90–98. doi: 10.5812/asjsm.34704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Barandun U, Knechtle B, Knechtle P, et al. Running speed during training and percent body fat predict race time in recreational male marathoners. Open Access Journal of Sports Medicine. 2012;2012(3):51–58. doi: 10.2147/OAJSM.S33284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rüst CA, Knechtle B, Knechtle P, Barandun U, Lepers R, Rosemann T. Predictor variables for a half marathon race time in recreational male runners. Open Access J Sports Med. 2011;2011(2):113–119. doi: 10.2147/OAJSM.S23027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rodriguez NR, Di Marco NM, Langley S for American Dietetic Association, Dietitians of Canada, American College of Sports Medicine. American College of Sports Medicine position stand. Nutrition and athletic performance. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2009;41(3):709–731. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0b013e31890eb86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ely MR, Cheuvront SN, Roberts WO, Montain SJ. Impact of weather on marathon-running performance. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2007;39(3):487–493. doi: 10.1249/mss.0b013e31802d3aba. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]