Abstract

Ewing's sarcoma (ES) is a rare malignancy primarily affecting skeletal system and it is commonly diagnosed in children and young adults. It seldom occurs in the head and neck region. ES has poor prognosis because of uncontrolled metastatic potential making early diagnosis and intervention critical for survival of the patient. This paper reports a rare case of ES involving mandible in an 8-year-old girl with clinical, radiological, histopathological and immunohistochemical features.

Keywords: CD 99, Ewing's sarcoma, immunohistochemistry, mandible

Introduction

Ewing's sarcoma (ES) is a rare malignant round cell tumor that was first described by Ewing in 1921. It can occur in any bone but commonly it is found in the diaphysis of long bones and pelvic girdle. In the head and neck region, though involved rarely, predilection is toward mandible followed by maxilla.[1]

It accounts for 4-10% of all primary bone cancers affecting adolescents and young adults and it seldom develops after 30 years of age. The mean age of occurrence in the head and neck region is 10.9 years. ES generally affects white population and the male sex (male/female ratio, 1.3-1.5:1).[2] According to anatomical site of occurrence it is classified as:(a) intraosseous (most common) (b) extraskeletal (less common) and (c) periosteal (rare) type.[3]

ES is an aggressive tumor showing rapid growth and metastasis. It is a part of the ES family of tumors (ESFT), which also includes peripheral neuroectodermal tumor (PNET), neuroepithelioma and Askin's tumor.[4] This has made the diagnosis further complex. Immunohistochemistry and molecular assays for chromosomal translocation seem to be the main stay of diagnosis. ES has the most unfavorable prognosis of all primary musculoskeletal tumors. Even with early intervention, patients with metastasis have approximately 20% chance of 5-year survival.[5] Here we report a case of ES involving mandible in an 8-year-old girl with a pertinent review of Indian literature to make the clinicians aware of the clinical and histopathological spectrum of this rare tumor.

Case Report

An 8-year-old girl visited the Department of Oral Pathology of this institution with 7-month history of a painless, gradually increasing swelling in the mandibular anterior region. The lesion was previously attempted for surgery elsewhere and regional teeth were extracted. Extraorally, a hard nontender swelling (4 × 2 cm) was observed on the lower one third of the anterior mandible which was covered by normal appearing skin [Figure 1]. Intraoral examination revealed involvement of mandibular alveolar ridge with expansion of both the cortical plates [Figure 2]. Overlying mucosa was centrally erythematous and nonulcerated. The mass was hard in consistency with a fluctuant area wherefrom blood tinged fluid was aspirated. The patient was apparently healthy with no sign of paresthesia or lymphadenopathy.

Figure 1.

Extraoral photograph showing swelling on the lower third of the anterior mandible

Figure 2.

Intraoral view showing involvement of mandibular alveolar ridge with expansion of cortical plates

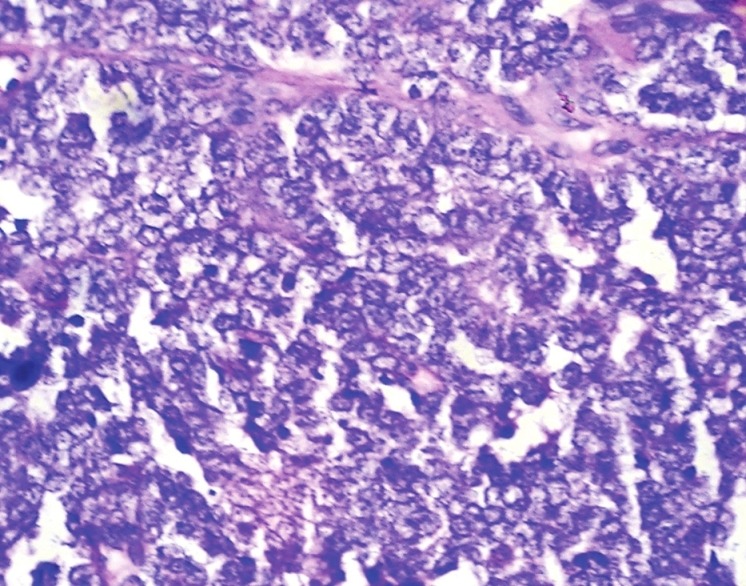

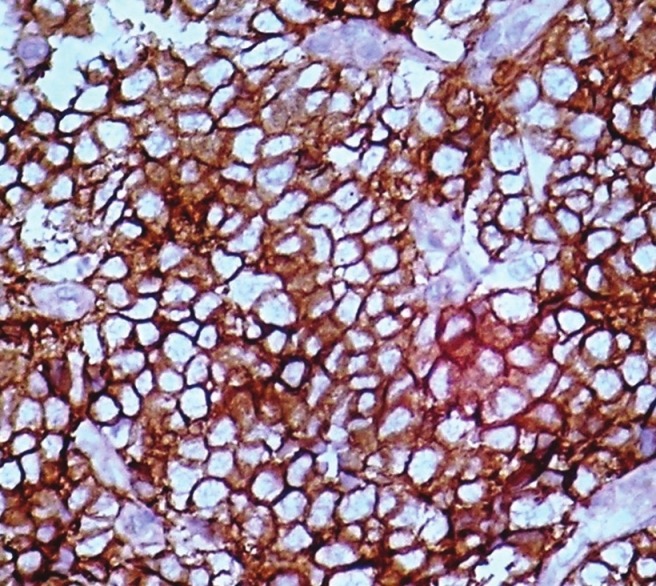

OPG revealed an ill-defined mixed radiodensity lesion extending from right first premolar to left deciduous second molar involving the crypts of permanent canines [Figure 3]. Destruction of cortical plates and ‘sun–ray’ appearance radiating from the lower border of mandible was also appreciated. Clinical and radiological features suggested a destructive lesion with a suspicion of malignancy. Routine hemogram and biochemical examination revealed no abnormality. Incisional biopsy was done after obtaining consent. Microscopy revealed sheets of small round cell population scattered in a scanty fibrovascular stroma. Individual cells exhibited hyperchromatic nuclei with infrequent mitotic figures surrounded by peripheral rim of scanty cytoplasm [Figure 4] Immunohistochemistry showed strong positivity for CD99.

Figure 3.

OPG shows ill-defined lytic destruction of cortical plates

Figure 4.

Histologic section showing sheets of small round cells with large nuclei, peripheral ring of cytoplasm and scanty stroma. (H & E stain, 40 × 10 magnification)

but no expression for LCA [Figure 5]. Histopathological and immunohistochemical findings supported the diagnosis of ES.

Figure 5.

Immunohistochemical expression showing CD-99 positivity in cytoplasm of tumor cells. (40 × 10 magnification)

Discussion

Concept of histogenesis and interrelationship of ES and PNET has undergone enormous evolution. Stout in 1918 reported a round cell ulnar nerve tumor having rosettes. In 1921 James Ewing described a round cell neoplasm calling it a ‘diffuse endothelioma of bone’ and proposed an endothelial derivation. Others believed it as a distinct entity and controversy went on.[6]

In 1956 Sherman reported three cases of periosteal ES (PES) of long bones.[6] Later Angervall and Enzinger in 1975 reported the first case of extraskeletal ES.[5,7,8] Askin in 1979 and Jaffe in 1984 reported malignant small round cell tumor of the thoracopulmonary region and ‘PNET of bone’, respectively.[9] In 1986 Bator reported well-established case of PES.[3]

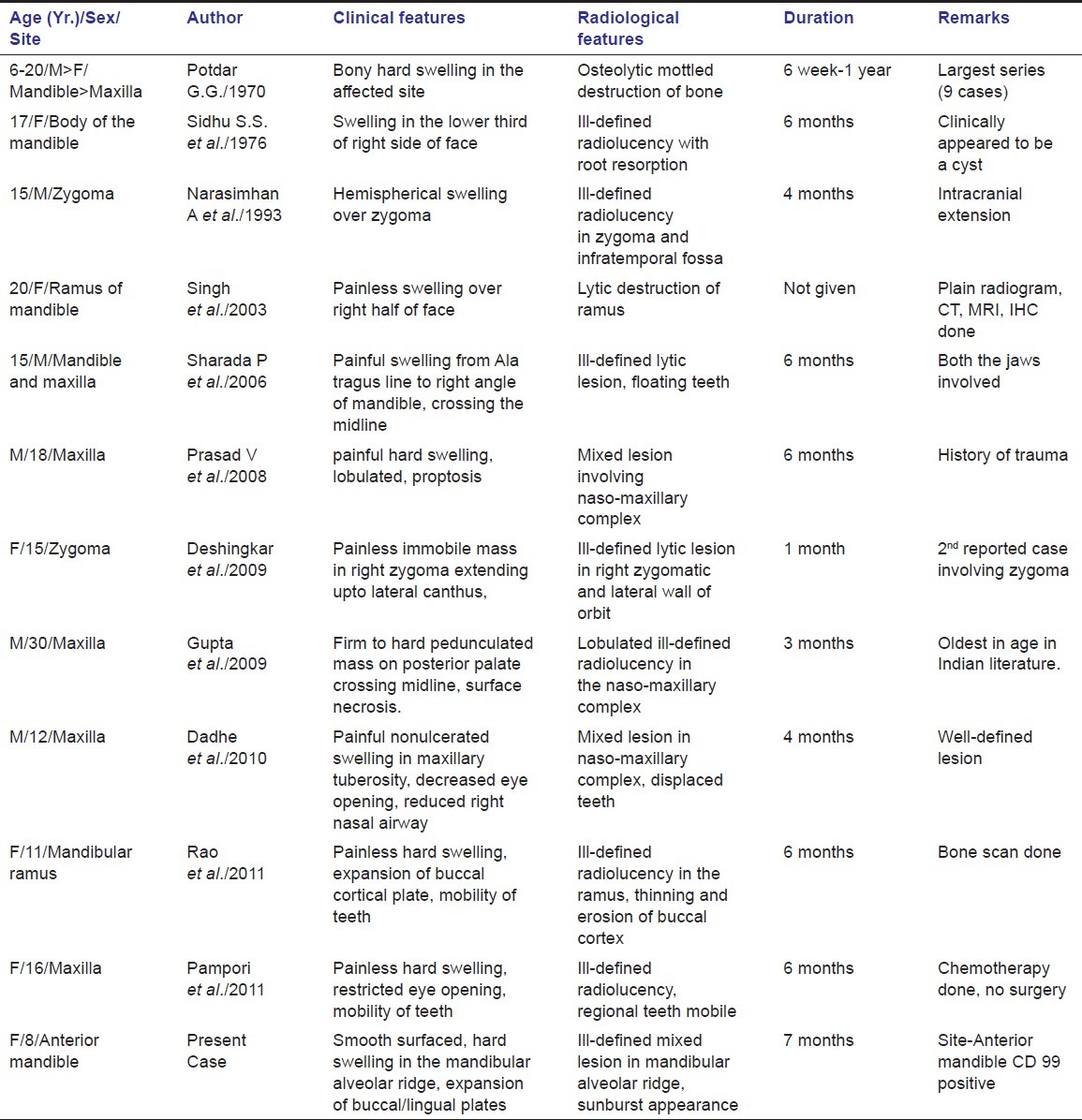

ES affecting jaws is uncommon among Indian population. Potdar in 1970 first reported nine cases of ES involving jaws. The tumors showed male preponderance and commonly affected mandible.[10] Sidhu in 1976 and Narasimhan in 1993 reported cases of ES affecting mandible and zygoma, respectively.[9,11] In 2003, Singh described involvement of mandible whereas in 2006 Sharada reported involvement of both the jaws.[7,8] Prasad in 2008, Deshingkar and Gupta in 2009 and Dadhe in 2010 reported cases with extensive nasomaxillary destruction, proptosis of eye and decreased nasal airway competence.[4,12–14] Rao and Pampori in 2011 reported cases of ES involving mandible and maxilla, respectively.[15] Till date only 19 cases of ES involving jaws have been described in Indian literature. Present case is the only report where symphyseal region is involved [Table 1].

Table 1.

Summary of all reported cases of ES involving Jaws in India until May, 2012

Recent studies showed that ES, PNET and Askin's tumor had overlapping features, supporting a common histogenesis. Identification of a common translocation t (11;22) (q24;q12) resulting in EWS–ETS fusion gene in above-mentioned tumors strongly supported their inter-relationship making them included in same group, the ESFT.[14]

Generally the clinical symptoms are nonspecific like rapidly growing swelling of the affected area, pain, loosening of teeth, otitis media, paresthesia, etc. Systemic symptoms like fever, lymphadenopathy, weight loss, anemia, albuminuria are observed frequently.[2]

Radiographically, ES appears as an ill-defined osteolytic lesion with displacement of unerupted tooth follicles. The characteristic ‘sun-burst’ or laminar periosteal “onion skin” reaction, a common radiological feature of ES involving long bones, is rarely seen in jaws.[13,15] In the present case, the radiographic finding was an ill-defined osteolytic lesion associated with sun-ray spicules of periosteal bone. CT scan provides more information but in this case patient could not afford it.[2]

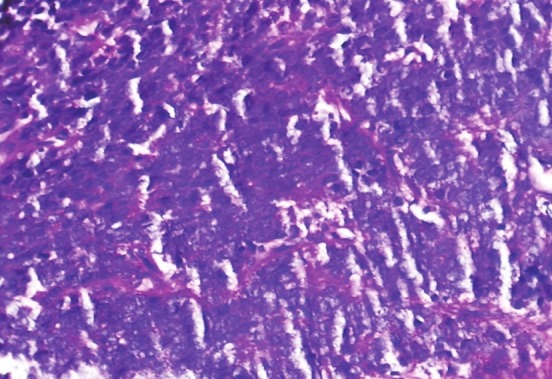

Histopathologically, ES is composed of small round anaplastic cells with medium-sized, round to oval nuclei, small nucleoli and scanty peripheral ring of cytoplasm. PAS stain demonstrate intracytoplasmatic glycogen in most cases though it is not pathognomonic.[2] [Figure 6] Definitive diagnosis of ES depends on histology and genetic confirmation. One should differentiate ES with “small round cell tumors of childhood”, which include rhabdomyosarcoma, lymphoma, and ESFT. All these neoplasms show same histological features like anaplastic cells having uniform round or oval nuclei and scant cytoplasm. Immunohistochemistry is essential for diagnosis. Positivity to CD99, with membranous accentuation, is characteristic of ES. Although lymphoblastic lymphoma is also strongly immunoreactive to CD99 and has same membrane pattern it is immunoreactive to leukocyte common antigen LCA (CD45), while ES is not. Rhabdomyosarcoma, though immunoreactive to CD99, shows focal, weak, and cytoplasmic staining. This case demonstrated negative immunostaining to LCA.[2]

Figure 6.

PAS staining of sections showing positivity for intracytoplasmic glycogen (PAS stain)

Immunopositivity, PAS stain findings with absence of osteoid in microscopy goes in favor of diagnosis of ES in present case. PCR molecular analysis is also helpful for diagnosis. Most ES shows characteristic chromosomal translocation between chromosomes 11 and 22, the t (11;22) (q24;q12) and trisomies 8 and/or 12 are observed in one-third to half of the cases.[2,14] Demonstration of EWS/FLI1 fusion is a better prognostic indicator than other variant gene fusions.[14] This could not be performed here due to unwillingness of the patient party.

Combined therapy including surgery, radiotherapy and chemotherapy is the best approach for ES. Multidisciplinary treatment protocols have dramatically improved the 5-year survival rate of patients from 16 to 75%. Radiotherapy can treat nonresectable primaries and chemotherapy can suppress micrometastasis and reduce tumor load before surgery. The chemotherapeutic agents commonly used are vincristine, doxorubicin, cyclophosphamide, ifosfamide and actinomycin-D. ES has poor prognosis because of hematogenous spread and lung metastases occur rapidly. Systemic symptoms, high erythrocyte sedimentation rate, elevated serum lactate dehydrogenase levels and thrombocytosis are poor prognostic indicator. However, tumors in jaws have a better prognosis than those in long bones.[2] After the confirmatory diagnosis, the patient was planned for surgery. Unfortunately, the patient did not turn up and her fate is unknown.

Conclusions

We have described a unique case of ES as it is the first report of ES arising in anterior mandible in Indian literature. Because of high metastatic potential it demands early intervention. Evaluation of lesion using plain radiographs, CTs, MRIs, and biopsy followed by histopathology and immunohistochemistry is necessary for early diagnosis.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil,

Conflict of Interest: None declared

References

- 1.Infante-Cossio P, Gutierrez-Perez JL, Garcia-Perla A, Noguer-Mediavilla M, Gavilan-Carrasco F. Primary Ewing's sarcoma of the maxilla and zygoma: Report of a case. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2005;63:1539–42. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2005.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brazão-Silva MT, Fernandes AV, Faria PR, Cardoso SV, Loyola AM. Ewing's sarcoma of the mandible in a young child. Braz Dent J. 2010;21:74–9. doi: 10.1590/s0103-64402010000100012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kollender Y, Shabat S, Nirkin A, Issakov J, Flusser G, Merimsky O, et al. Periosteal Ewing's sarcoma: Report of two new cases and review of the literature. Sarcoma. 1999;3:85–8. doi: 10.1080/13577149977695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Deshingkar S, Barpande S, Tupkari J. Ewing's sarcoma of zygoma. J Oral Maxillofac Pathol. 2009;13:18–22. doi: 10.4103/0973-029X.48744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Iwamoto Y. Diagnosis and treatment of Ewing's Sarcoma. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2007;37:79–89. doi: 10.1093/jjco/hyl142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Potdar G. Ewing's tumors of the jaws. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1970;39:505–12. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(70)90458-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sidhu SS, Parkash H. Ewing's Sarcoma of the Mandible. J Dent. 1976;5:227–30. doi: 10.1016/0300-5712(76)90053-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Narasimhan A, Sundaram M, Chandy SM, Washburn M, Williams RR. Case report 786: Ewing's sarcoma of the left zygoma. Skeletal Radiol. 1993;22:293–5. doi: 10.1007/BF00197678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Singh JP, Garg L, Shrimali R, Gupta V. Radiological appearance of Ewing's Sarcoma of the mandible. Indian J Radiol Imaging. 2003;13:23–5. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sharada P, Girish HC, Umadevi HS, Priya NS. Ewing's sarcoma of the mandible. J Oral Maxillofac Pathol. 2008;10:31–5. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vikas Prasad B, Ahmed Mujib BR, Bastian TS, David Tauro P. Ewing's sarcoma of the maxilla. Indian J Dent Res. 2008;19:66–9. doi: 10.4103/0970-9290.38935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dadhe DP, Garde JB, Sambhus MB. Ewing's sarcoma in maxilla in an adolescent boy. J Int Clin Dent Res Organ. 2010;3:153–6. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gupta S, Gupta OP, Mehrotra S, Mehrotra D. Ewing sarcoma of the maxilla: A rare presentation. Quintessence Int. 2009;40:135–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rao BH, Rai G, Hassan S, Nadaf A. Ewing's sarcoma of the mandible. Natl J Maxillofac Surg. 2011;2:184–8. doi: 10.4103/0975-5950.94479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pampori R, Shamas IU, Malik A. EWING's SARCOMA OF MAXILLA: A case Report. JPMI. 2011;25:171–4. [Google Scholar]