Background: Serum levels of the soluble LR11 fragment (sLR11) increase in patients with acute leukemia.

Results: Hypoxia-induced factor (HIF)-1α activation increases LR11 levels, and sLR11 enhances adhesion of HSPCs to BM stromal cells via a uPAR-mediated pathway.

Conclusion: sLR11 regulates hypoxia-induced attachment of HSPCs.

Significance: sLR11 may stabilize the hematological pool size by controlling HSPC attachment to the BM niche.

Keywords: Bone Marrow, Cell Adhesion, Hypoxia, Hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF), Urokinase Receptor, HSPC, LR11

Abstract

A key property of hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells (HSPCs) regarding differentiation from the self-renewing quiescent to the proliferating stage is their adhesion to the bone marrow (BM) niche. An important molecule involved in proliferation and pool size of HSPCs in the BM is the hypoxia-induced urokinase-type plasminogen activator receptor (uPAR). Here, we show that the soluble form (sLR11) of LR11 (also called SorLA or SORL1) modulates the uPAR-mediated attachment of HSPCs under hypoxic conditions. Immunohistochemical and mRNA expression analyses revealed that hypoxia increased LR11 expression in hematological c-Kit+ Lin− cells. In U937 cells, hypoxia induced a transient rise in LR11 transcription, production of cellular protein, and release of sLR11. Attachment to stromal cells of c-Kit+ Lin− cells of lr11−/− mice was reduced by hypoxia much more than of lr11+/+ animals. sLR11 induced the adhesion of U937 and c-Kit+ Lin− cells to stromal cells. Cell attachment was increased by sLR11 and reduced in the presence of anti-uPAR antibodies. Furthermore, the fraction of uPAR co-immunoprecipitated with LR11 in membrane extracts of U937 cells was increased by hypoxia. CoCl2, a chemical inducer of HIF-1α, enhanced the levels of LR11 and sLR11 in U937 cells. The decrease in hypoxia-induced attachment of HIF-1α-knockdown cells was largely prevented by exogenously added sLR11. Finally, hypoxia induced HIF-1α binding to a consensus binding site in the LR11 promoter. Thus, we conclude that sLR11 regulates the hypoxia-enhanced adhesion of HSPCs via an uPAR-mediated pathway that stabilizes the hematological pool size by controlling cell attachment to the BM niche.

Introduction

Hypoxic conditions play a key role in the regulation of the pool size of hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells (HSPCs)3 in the bone marrow (BM) through the regulation of many molecules expressed in HSPCs (1, 2). The partial pressure of oxygen (pO2) of the endosteal sites is known to be much lower than that of the nearest capillaries (3). Long term hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) reside mainly in the endosteum (4–6) and are stained with pimonidazole, a chemical probe for hypoxia (7–9). Accordingly, human cord blood HSCs transplanted into immunodeficient mice require a hypoxic status to maintain cell cycle quiescence in the BM (10).

One of the key regulatory functions of the molecules in the HSPCs under hypoxia is the modulation of cell adhesion to the osteoblastic niche to facilitate the differentiation from the immature quiescent self-renewal stage to the downstream proliferating mature hematological cell stage (1, 2, 11). Many proteins including Sca-1, c-Kit, CD34, and urokinase-type plasminogen activator receptor (uPAR; CD87) have been identified as regulators of HSPC adhesion to osteoblastic niches (12–17). In fact, recent studies using overexpressing or knock-out mice and cells for angiopoietin-1, thrombopoietin, bone morphogenetic protein-4, Secreted frizzled related protein-1 (Sfrp-1), or uPAR have shown that changes in expression of the respective gene cause disturbed maintenance of normal HSPC pool size and lead to pathological conditions typical of hematological proliferative disease or severe anemia (2). In fact, uPAR has been shown to be a major regulator of proliferation, marrow pool size, engraftment, and mobilization of murine HSPCs (17). Together with previous results of analyses of uPAR as a prognosis marker in leukemic patients (18), disturbed regulation of uPAR may be important in the pathogenesis of leukemias involving uPAR-expressing malignant cells. Although uPAR expression is known to be induced by hypoxia in cultured hematological cells (19), the mechanism underlying the up-regulation of uPAR under hypoxic conditions has not yet been elucidated.

We have identified and characterized a regulator of uPAR function, LR11 (also called SorLA or SORL1), in vascular smooth muscle cells (SMCs) (20, 21). LR11 is a type I membrane protein, from which a large soluble extracellular part, sLR11, is released by proteolytic shedding (20, 22–24). sLR11 accelerates intimal thickening and macrophage foam cell formation in the process of atherosclerosis (25). Recent studies in humans and animals have shown that sLR11 is produced by myeloid cells after G-CSF treatment and that the released sLR11 plays an important role in the G-CSF-induced leukocyte mobilization from BM to the circulation.4 Zhang et al. reported high levels of LR11 mRNA in human CD34+ CD38− immature hematopoietic precursors (26). Both LR11 mRNA and cell surface protein levels are elevated in immature leukemic cells, in turn leading to increased levels of sLR11 in acute leukemias (27). Thus, it is conceivable that in hypoxic environments, modulation of uPAR expression by sLR11 may be important for maintenance of the HSPC pool size.

Here, we have studied the regulation of LR11 expression in hematological cells under hypoxic conditions such as those found in the BM niche. Immature and mature hematological cells in the BM express LR11 in a hypoxia-sensitive fashion. HIF-1α activation by hypoxia or chemical means leads to increased LR11 expression, which in turn enhances the adhesion of leukemia cells to stromal cells through direct interaction of sLR11 with uPAR. Regulation of uPAR by LR11 may provide the basis for a novel strategy toward maintenance of the hematological cell pool size via modification of uPAR functions in hypoxic niches of the BM.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Mice

All animal studies were reviewed and approved by the Special Committee on Animal Welfare, School of Medicine, at the Inohana Campus of Chiba University. Lr11−/− mice (21) were maintained under standard animal house conditions with a 12-h light/dark cycle and were fed ad libitum with regular chow diet.

Antibodies, Recombinant Proteins

Monoclonal antibodies (A2-2-3, M3, and R14) against LR11 have been described previously (28). M3 was used for immunoprecipitation and ELISA, A2-2-3 for immunoblotting, and R14 for immunohistochemistry and ELISA. Polyclonal antibodies against uPAR and HIF-1α were from R&D Systems and Cell Signaling Technology, respectively. Recombinant LR11 protein lacking the 104 C-terminal amino acids containing the transmembrane region (sLR11) was prepared as described (22).

Cells

The human promonocytic cell line U937 and the human myeloid cell line K562 were purchased from ATCC. Human mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) were purchased from Lonza. The mouse stromal cells, OP-9, were provided by Dr. Osawa (Chiba University). For murine cell sorting, BM cells were first stained with biotinylated-anti-Lineage (Lin) (CD5, B220, CD11b, Gr-1, 7–4, Ter-119) followed by incubating with streptavidin microbeads (Miltenyi Biotec). After washing with staining buffer (PBS containing 0.5% BSA and 2 mm EDTA), Lin+ and Lin− cells, respectively, were enriched using magnetically activated cell sorting (MACS) columns. For mouse c-Kit+ Lin− cell sorting, Lin−-enriched cells were stained with anti-c-Kit microbeads (Miltenyi Biotec), then c-Kit+ Lin− cells were enriched using MACS columns. U937 cells and K562 cells were cultured in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 10% FBS. MSCs were cultured in MSC growth medium, MSCGM (basal medium with growth supplements; Lonza) and were used between passages 2 and 5. OP-9 cells were cultured in DMEM, supplemented with 20% FBS. Lin− cells and c-Kit+ Lin− cells were cultured in Iscove's modified Dulbecco's medium with 20% FBS. For hypoxia treatment, the cells were cultured in a humidified multigas incubator (APM-30D; Astec) with 1% O2 and 5% CO2 at 37 °C.

Cell Adhesion Assay

Cell adhesion was determined in 96-well plates as described (22). For experiments using vitronectin-coated plates, wells were coated with 10 ng/well vitronectin for 2 h at 37 °C. For the preparation of OP-9- and MSCs-coated plates, OP-9 and MSCs were seeded onto 96-well plates 24 h at 37 °C, respectively, to obtain a confluent cell layer before experiments. Freshly purified mouse primary cells or U937 cells were fluorescently labeled by loading with calcein acetoxymethylester (calcein AM; BD Bioscience) for 1 h at 1 × 107 cells/ml in Hanks' buffered saline solution containing 1% BSA. Calcein-loaded cells were added to the vitronectin-, OP-9-, or MSCs-coated plates at 3 × 104 cells/well. After centrifugation, the culture plates were incubated for 20 min at 37 °C to allow the cells to attach to the coated plates. Nonattached cells were removed by gently washing three times with PBS, and the attached cells were quantitated by measuring fluorescence intensity using a fluorescence microplate reader (SPECTRAmax GEMINI XS; Molecular Devices). The numbers of attached cells were determined from standard curves generated by serial dilutions of known numbers of labeled cells.

LR11-overexpressing Cells, LR11-knockdown Cells, and HIF-1α-knockdown Cells

For the generation of LR11-overexpressing cells, transient transfection of U937 cells and transfection for stable expression in K562 cells were carried out with pBKCMVhLR11 (29) or pBK-CMV (mock) by using the Neon electroporation device (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer's guidelines. Stable transfectants were selected in medium supplemented with 800 μg/ml G418 (Roche Applied Science) and maintained in medium containing 400 μg/ml G418. For the generation of LR11-knockdown cells, Lentiviral vectors (CS-H1-shRNA-EF-1α-EGFP) expressing short hairpin RNAs (shRNAs) that target two different sequence regions in human LR11 cDNA (region 1, 5′-GGATCATGATTCAGGAACA-3′ and region 5, 5′-GGAGAGAGCATATGGAAGA-3′) and that target luciferase as control (Cosmo Bio) were constructed. The virus particles were produced as described previously (30). Briefly, plasmid DNA was transfected into 293T cells along with the packaging plasmid (pCAG-HIVgp) and the VSV-G and Rev-expressing plasmid (pCMV-VSV-G-RSV-Rev) by calcium phosphate co-precipitation. Stable shRNA-expressing U937 cells were generated by infection with the supernatants from transfected 293T cells in the presence of 5 μg/ml protamine sulfate for 24 h with subsequent sorting of the GFP-positive cells using FACS Aria (BD Biosciences). For the generation of HIF-1α-knockdown cells, HIF-1α small interfering RNA (siRNA) and control siRNA were designed and synthesized by Ambion. These siRNAs were transfected into U937 cells by using the Neon electroporation device according to the manufacturer's guidelines.

Western Blotting and Immunoprecipitation

Sorted cells or cultured cells were washed three times with PBS and harvested in ice-cold radioimmuneprecipitation assay buffer with protease inhibitors (Complete Mini; Roche Applied Science). Cell lysates were recovered in the supernatant after centrifugation at 20,000 × g for 30 min. Protein concentrations were determined using the BCA protein assay kit (Thermo Scientific). Samples were mixed with an equal volume of 2× Laemmli sample buffer containing 5% β-mercaptoethanol and heated for 5 min at 90 °C. Where indicated, cells were incubated with sLR11 (1 μg/ml) at 37 °C for 15 min and harvested, and 10 ng of mouse anti-LR11 antibody (M3) or mouse IgG was added and incubated at 4 °C overnight under mixing. The LR11-uPAR-antibody complex was bound to protein G-Sepharose. The proteins were released into Laemmli sample buffer containing 5% β-mercaptoethanol by heating to 90 °C for 10 min. Protein samples were subjected to SDS-PAGE, and the immunoreactive signals were detected by mouse monoclonal antibody against LR11 (A2-2-3), goat polyclonal antibody against uPAR, or rabbit polyclonal antibody against human HIF-1α, followed by horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated anti-mouse, anti-goat, or anti-rabbit IgG, respectively. Development was performed with the ECL detection reagents (GE Healthcare). The signals were quantified with ChemiDoc XRS+ system using Image Lab software (Bio-Rad).

RNA Extraction and Real-time Quantitative PCR Analysis

Total RNA was isolated using the RNeasy Kit (Qiagen). RNA was eluted and quantified using the Nanodrop spectrometer (Thermo Scientific). The reverse transcription step was performed with the TaqMan Reverse Transcription Reagent Kit (Applied Biosystems) according to the manufacturer's guidelines. LR11 mRNA levels were determined by quantitative real-time PCR on the cDNA samples using the TaqMan assay-on-demand kit with the ABI-PRISM 7000 (Applied Biosystems). Analysis was carried out in triplicate in a volume of 20 μl for LR11 and the endogenous reference gene 18S rRNA, which does not change in hypoxia (31), and the comparative threshold cycle method was used. In each experiment, the RNA prepared from a sample obtained from normoxic conditions was used as calibrator to allow comparison of relative mRNA levels.

Flow Cytometric Analysis

For the analysis of uPAR expression, cells were washed with PBS and incubated at 4 °C in the dark for 30 min with phycoerythrin-conjugated anti-uPAR antibody (BioLegend). Isotype control antibody (BD Biosciences) was used as a negative control. Flow cytometric analyses were performed with a FACSCant II (BD Biosciences).

ELISA

Amounts of soluble LR11 released into the culture medium were determined by sandwich ELISA as reported previously (27). Briefly, culture media were concentrated by using Amicon Ultra-15 (100,000 NMWL membranes from Millipore), and the concentrated sample was reacted with the capture monoclonal antibody M3 and then incubated with the biotinylated reporter rat monoclonal antibody R14. The LR11-Mab complex was reacted with HRP-conjugated streptavidin. A standard curve was constructed using purified LR11 protein.

Chromatin Immunoprecipitation Assay

U937 cells were cross-linked with 1% formaldehyde for 10 min at room temperature followed by the addition of 0.125 m glycine and incubation for 5 min at 4 °C. After washing with PBS, 1 × 107 cells were treated with cell lysis buffer (50 mm Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), 10 mm EDTA, 150 mm NaCl, 0.5% SDS, and protease inhibitors) on ice and sonicated until the DNA fragments had an average size 200–500 bp using a Bioruptor (Cosmo Bio). After centrifugation at 15,000 rpm for 10 min, sheared chromatin was diluted 10-fold in dilution buffer (50 mm Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), 150 mm NaCl, 1.1% Triton X-100, 0.11% sodium deoxycholate, and protease inhibitors). After incubation with Dynabeads protein G (Invitrogen) for 1 h at 4 °C, the precleared chromatin was immunoprecipitated overnight at 4 °C with anti-HIF-1α antibodies (clone H1α67, Abcam)/Dynabeads protein G mix. Beads were then sequentially washed with the following combination of wash buffers: twice each with low salt wash buffer (50 mm Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), 150 mm NaCl, 1 mm EDTA, 1% Triton X-100, 0.1% SDS, and 0.1% sodium deoxycholate), high salt wash buffer (50 mm Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), 500 mm NaCl, 1 mm EDTA, 1% Triton X-100, 0.1% SDS, and 0.1% sodium deoxycholate), and LiCl wash buffer (10 mm Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), 250 mm LiCl, 1 mm EDTA, 0.5% Nonidet P-40, and 0.5% sodium deoxycholate), and TE buffer. Bound chromatin together with input DNA was released from the antibodies/protein G beads by elution buffer (50 mm Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), 10 mm EDTA, and 1% SDS), and cross-linking was reversed by incubation in the same buffer overnight at 65 °C. Immunoprecipitated DNA or input DNA was treated with RNaseA (Sigma) and proteinase K (Roche Applied Science), and then extracted with phenol:chloroform for subsequent PCR analysis. The primers used in this analysis spanned 144 bp around the putative HIF-1-binding site within the LR11 promoter (sense, 5′-GCGCTCGCTGCCTTAACTTC-3′ and antisense, 5′-CCAGGTCCCGCTCGGTTC-3′), and 166 bp around that in the CD18 promoter as control (32).

Statistics

The results are shown as mean ± S.D. for each index. One-way analysis of variance was used to compare between two groups, and Dunnett's multiple-range test was used for comparison of multiple groups. A value of p < 0.05 was considered significant.

RESULTS

Expression of LR11 in Murine HSPCs and Human U937 Cells Is Induced by Hypoxic Conditions

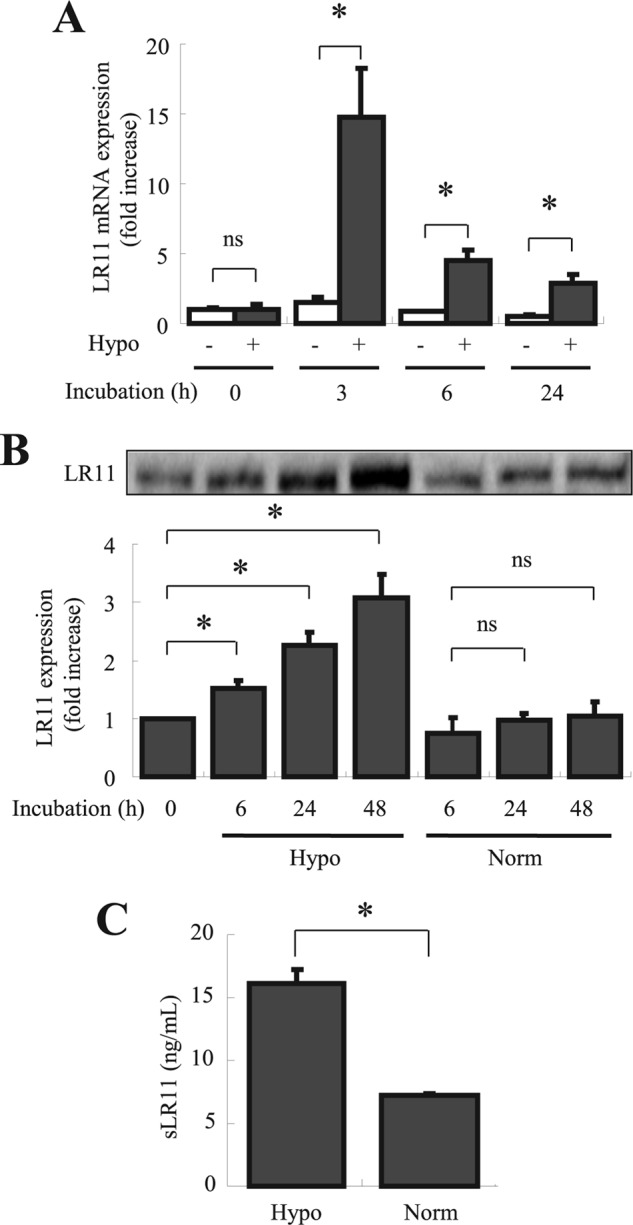

First, we investigated LR11 expression levels of HSPCs under low oxygen conditions by immunochemistry. Protein extracts of c-Kit+ Lin− cells or Lin+ cells, representing HSPCs, were subjected to immunoblot analysis with the monoclonal antibody against LR11, R14 (28) (Fig. 1). The LR11 levels in the c-Kit+ Lin− cells were significantly lower than those of the differentiated Lin+ cells under normoxic conditions. However, the LR11 expression levels in the c-Kit+ Lin− cells progressively increased with prolonged exposure to the hypoxic conditions, whereas the levels in the Lin+ cells remained relatively constant. These results indicate that the hematological cells in the BM express LR11 and that the expression in HSPCs is induced by hypoxic conditions. To analyze the regulation of sLR11 expression in hypoxic environments in detail, we investigated the effects of hypoxic conditions on LR11 expression in U937 cells, an undifferentiated leukemia cell line (33). When the cells were incubated under hypoxic conditions, the LR11 mRNA levels increased 15-fold over the levels under normoxic conditions after 3 h and then declined within 24 h (Fig. 2A). Importantly, the LR11 protein in the hypoxic cells was elevated after 6 h compared with normoxic cells and increased to 3-fold of the unchanged control levels after incubation for 48 h (Fig. 2B). The amount of sLR11 released from the cells was also increased after 48-h incubation under hypoxia (Fig. 2C). Thus, hypoxia induced a transient increase in the transcription of the LR11 gene and subsequent production of cellular protein, accompanied by release of the shed form into the media.

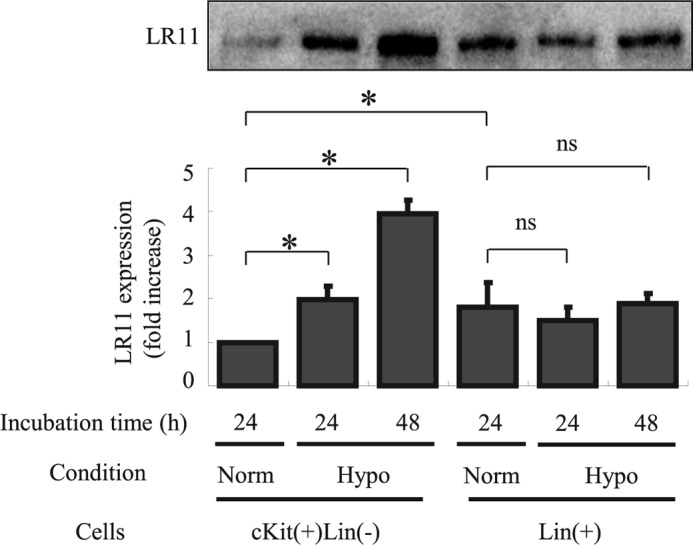

FIGURE 1.

Hypoxia induces expression of LR11 in HSPCs. After incubation for 24 or 48 h under normoxic or hypoxic conditions, the LR11 expression levels in c-Kit+ Lin− cells and Lin+ cells were evaluated by immunoblot analysis as described under “Experimental Procedures.” The LR11-specific signals at 250 kDa were quantified using the Image Lab software. The blot shown is representative of three independent experiments. Data are presented as mean ± S.D. (error bars; n = 3). *, p < 0.05; ns, not significant.

FIGURE 2.

Effects of hypoxia on LR11 mRNA levels and on sLR11 production by U937 cells. A, LR11 mRNA expression in U937 cells after incubation under normoxic or hypoxic conditions for 3, 6, and 24 h was analyzed by quantitative PCR as described under “Experimental Procedures.” mRNA levels are represented as -fold increase of those at 0 h. Data are presented as mean ± S.D. (error bars; n = 3). *, p < 0.05; ns, not significant. B, after incubation under normoxic or hypoxic conditions for 6, 24, and 48 h, LR11 expression levels in U937 cells were analyzed by immunoblot analysis. The LR11-specific signals at 250 kDa were quantified using the Image Lab software. The blot shown is representative of three independent experiments. Data are presented as mean ± S.D. (n = 3). *, p < 0.05; ns, not significant. C, the concentrations of sLR11 in conditioned media of U937 cells incubated under normoxic or hypoxic condition for 48 h were determined by ELISA as described under “Experimental Procedures.” Data are presented as mean ± S.D. (n = 3). *, p < 0.05.

LR11 Mediates the Hypoxia-induced Adhesion of Immature Hematological Cells and HSPCs to Stromal Cells

As hypoxia has been shown to induce HSPCs adhesion (34, 35), the above results suggested that the enhanced expression of LR11 may contribute to the hypoxia-induced adhesion of HSPCs to osteoblastic niches. To test for such a role of LR11, we analyzed the effects of LR11 knockdown on the adhesion of U937 cells to MSCs. As shown in Fig. 3A, hypoxic conditions failed to stimulate adhesion of the U937 clone with largely reduced LR11 expression (see inset in Fig. 3A), but the enhanced adhesion was readily observed in control cells. We, therefore, analyzed the effect of LR11 knock-out on the adhesion of HSPCs to OP-9 murine stromal cells under hypoxia. Under normoxic conditions, the numbers of c-Kit+ Lin− cells from lr11−/− and lr11+/+ mice that attached to the stromal cells were not significantly different. However, whereas the adhesion of both lr11−/− and lr11+/+ cells was significantly increased under hypoxic conditions (Fig. 3B), the enhancement of adhesion of the lr11−/− cells was significantly less than that of lr11+/+ cells. Thus, LR11 functions in the hypoxia-increased adhesion to stromal cells of HSPCs and undifferentiated hematological cells. To identify the exact function of sLR11 in hypoxia-induced adhesion of HSPCs to stromal cells, we analyzed the effects of exogenously added sLR11 on this process. Incubation of U937 cells with sLR11 for 2 h drastically increased the numbers of cells attached to MSCs (Fig. 4A). Consistent with the effects of exogenously added sLR11 on cell adhesion, LR11-overexpressing U937 cells showed significantly increased adhesion compared with the control U937 cells (Fig. 4B). Furthermore, incubation with sLR11 induced the adhesion of c-Kit+ Lin− cells to OP-9 cells in a dose-dependent fashion (Fig. 4C). These results indicate that sLR11 is an important component of the pathway that mediates the stimulation of HSPC adhesion to stromal cells.

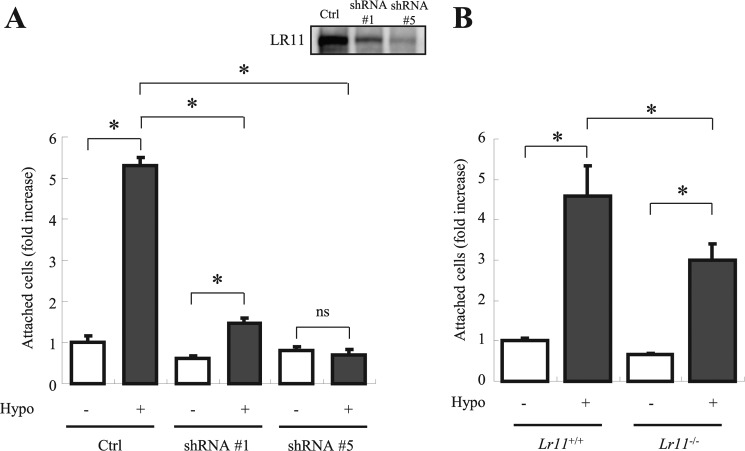

FIGURE 3.

Effects of manipulating LR11 levels on the hypoxia-induced adhesion of immature hematological cells. A, after incubation in hypoxic or normoxic conditions for 24 h, the numbers of attached U937 cells, either transfected with shRNA specific for LR11 (#1 or #5) or with control shRNA (Ctrl), to MSCs were determined as described under “Experimental Procedures.” Inset, LR11 levels in normal and LR11-knockdown U937 cells were analyzed by immunoblotting. Data are shown as -fold increase of those at control cells without hypoxic conditions and presented as mean ± S.D. (error bars; n = 3). *, p < 0.05; ns, not significant. B, after incubation in normoxic or hypoxic conditions for 24 h, the numbers of c-Kit+ Lin− cells prepared from LR11+/+ or LR11−/− mice attached to OP-9 cells were determined as described under “Experimental Procedures.” Data are presented as mean ± S.D. (n = 3). *, p < 0.05.

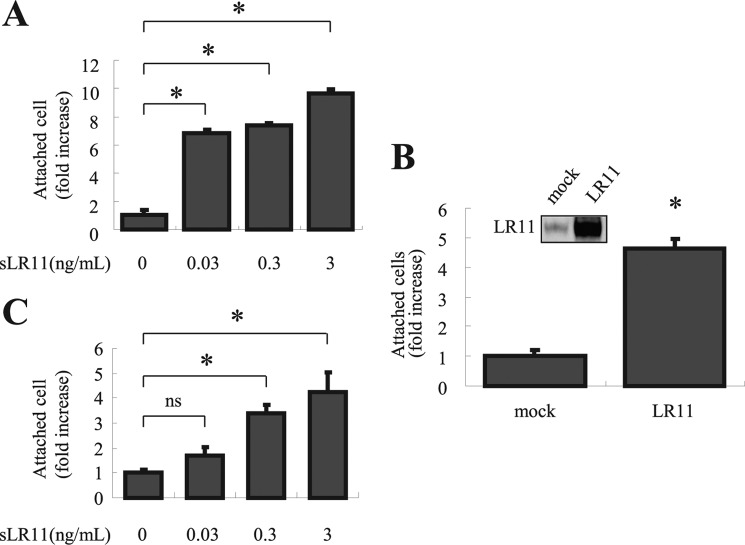

FIGURE 4.

Effects of sLR11 on HSPC adhesion to bone marrow stromal cells. A, U937 cells preincubated for 2 h with the indicated concentrations of sLR11 were subjected to analyses of their adhesion to plates coated with MSCs as described under “Experimental Procedures.” B, cells transiently transfected with cDNA specific for LR11 or with an empty vector (mock) were subjected to adhesion analyses as described for A. Inset, LR11 expression of mock-transfected and LR11-overexpressing U937 cells was analyzed by immunoblotting. C, c-Kit+ Lin− cells preincubated for 15 min with the indicated concentrations of sLR11 were subjected to analyses of their adhesion to plates coated with OP-9 cells as described under “Experimental Procedures.” In all panels, the numbers of attached cells are presented as -fold increase of those under control conditions (mean ± S.D. (error bars), n = 3). *, p < 0.05; ns, not significant.

Hypoxia Induces the Adhesion of U937 Cells to Stromal Cells via Formation of an LR11-uPAR Complex

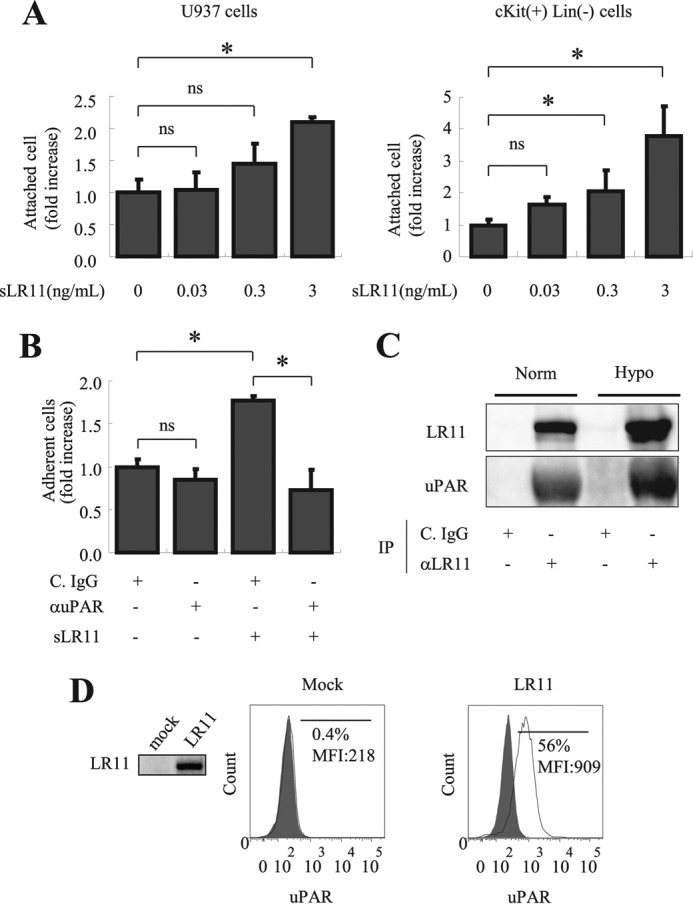

sLR11 enhances adhesion of SMCs through signaling via uPAR and integrins (21), and hypoxia leads to increased expression of uPAR in cultured hematological and other cells (19, 36, 37). Therefore, we examined whether uPAR also is a player in the sLR11-mediated adhesion of hematological cells. Incubation of U937 cells with sLR11 for 2 h increased in a dose-dependent fashion the number of cells attached to vitronectin-coated plates (Fig. 5A, left). Vitronectin is an extracellular partner of uPAR in receptor-mediated processes underlying cell attachment (38). Indeed, the adhesion of c-Kit+ Lin− cells to vitronectin-coated plates was increased by incubation with sLR11 in the same dose range (Fig. 5A, right) as that of U937 cells. The increase in numbers of attached cells upon incubation with sLR11 was completely abolished in the presence of anti-uPAR antibodies, but was only nonsignificantly reduced in the absence of exogenously added sLR11 (Fig. 5B). Immunoprecipitation analysis of membrane extracts of U937 previously incubated with sLR11 showed that uPAR was co-precipitated with sLR11 and that the amounts of both proteins increased after exposure of the cells to hypoxia for 24 h (Fig. 5C). Finally, flow cytometric analysis (Fig. 5D) of LR11-overexpressing K562 cells (see Fig. 5D, inset; LR11 was not immunologically detectable in control K562 cells) showed increased surface uPAR levels in comparison to mock-transfected cells. These data suggest that under hypoxic conditions, the increased amounts of sLR11 stimulate uPAR-mediated adhesion of immature hematological cells by enhancing the formation of LR11-uPAR complexes.

FIGURE 5.

Significance of LR11-uPAR complex formation in hypoxia-induced adhesion of U937 cells. A, U937 cells (left panel) or c-Kit+ Lin− cells (right panel) preincubated for 2 h with the indicated concentrations of sLR11 were subjected to analyses of their adhesion to plates coated with vitronectin as described under “Experimental Procedures.” The numbers of attached cells are presented as -fold increase over those without sLR11 (mean ± S.D. (error bars), n = 3). *, p < 0.05; ns, not significant. B, U937 cells preincubated for 4 h with or without 1 ng/ml sLR11 in the presence of anti-uPAR neutralizing antibody (αuPAR) or of control IgG (C. IgG) were subjected to analyses of their adhesion to plates coated with MSCs as described under “Experimental Procedures.” The numbers of attached cells are presented as -fold increase of those without sLR11 or without antibodies (mean ± S.D., n = 3). *, p < 0.05; ns, not significant. C, U937 cells preincubated for 24 h under normoxic or hypoxic conditions were incubated with 10 ng/ml sLR11 for 15 min, the cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with the monoclonal anti-LR11 antibody M3 (αLR11) or with control IgG (C. IgG) and subjected to immunoblot analysis with the monoclonal anti-LR11 antibody A2-2-3 or with polyclonal antibodies against uPAR, respectively, as described under “Experimental Procedures.” The signals for LR11 (250 kDa) or uPAR (65 kDa) were quantified using the Image Lab software. D, K562 cells stably transfected with cDNA specific for LR11 or vector alone (mock) were subjected to flow cytometric analysis as described under “Experimental Procedures.” The profiles of surface uPAR expression are presented in histograms. The frequencies and the mean fluorescence intensities (MFIs) of the fractions of cells with high uPAR levels are indicated. The filled histograms are isotype controls. Representative data from multiple experiments are shown. Inset, LR11 levels in control or LR11-overexpressing K562 cells were analyzed by immunoblotting using the monoclonal anti-LR11 antibody, A2-2-3.

LR11 Expression Is Dependent on HIF-1α-mediated Signals

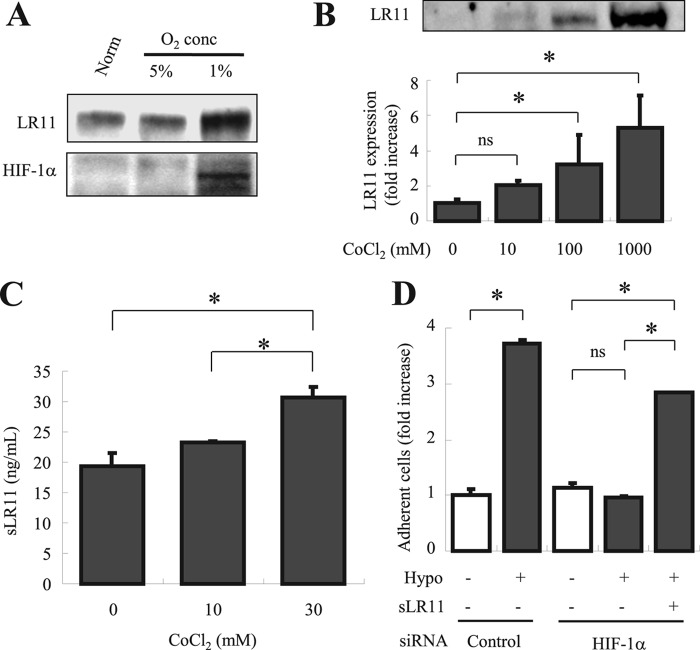

To gain insight into the mechanism underlying the induction of LR11 production by hypoxia, we tested whether changes in HIF-1α levels affect LR11 production. HIF-1α expression was increased by exposure of U937 cells to 1%, but not to 5%, oxygen (Fig. 6A). The response of HIF-1α expression to oxygen deprivation was the same as that of LR11, suggesting a functional link between LR11 and hypoxia-induced molecules such as HIF-1α. We therefore analyzed the effects of cobalt chloride (CoCl2), a chemical inducer of HIF-1α (39), on the expression of LR11 in the cells under normoxia. CoCl2 dose-dependently increased the LR11 levels in U937 cells (Fig. 6B) and also the amounts of sLR11 released into the conditioned media (Fig. 6C). Thus, a chemical enhancer of HIF-1α induced the production of sLR11 independent of hypoxia. Finally, using HIF-1α-knockdown cells, we directly examined the role of HIF-1α in the sLR11-mediated adhesion of U937 cells under hypoxic conditions. The attachment of HIF-1α-knockdown U937 cells to MSCs was not enhanced by exposure to hypoxia, but importantly, the enhancing effect was largely recovered by addition of sLR11 (Fig. 6D). These results show that activation of HIF-1α by hypoxia increases the expression of LR11, and in turn the production of sLR11. Thus, the action of HIF-1α in increasing the sLR11 levels under hypoxic conditions is responsible for enhancing the adhesion of hematological cells to stromal cells.

FIGURE 6.

Functional link between HIF-1α and LR11 in enhancing hypoxia-induced cell adhesion. A, after incubation for 24 h under normoxic or hypoxic conditions (1% O2 and 5% CO2), LR11 and HIF-1α protein levels were evaluated by immunoblot analysis with the monoclonal anti-LR11 antibody A2-2-3, or with polyclonal antibodies against HIF-1α, respectively, as described under “Experimental Procedures.” The specific signals for LR11 (250 kDa) and HIF-1α (120 kDa) were quantified using the Image Lab software. B, U937 cells incubated for 48 h with the indicated concentrations of CoCl2 were subjected to immunoblot analysis using monoclonal anti-LR11 antibody A2-2-3 as described under “Experimental Procedures.” The LR11-specific signals at 250 kDa were quantified using the Image Lab software. The blot shown is representative of three independent experiments. Data are presented as mean ± S.D. (error bars; n = 3). *, p < 0.05; ns, not significant. C, conditioned media collected after incubation for 48 h with the indicated concentrations of CoCl2 were concentrated and subjected to sLR11 measurement by ELISA as described under “Experimental Procedures.” Data are presented as mean ± S.D. (n = 3). *, p < 0.05; ns, not significant. D, after incubation in normoxic or hypoxic conditions for 24 h with or without 1 ng/ml sLR11, the numbers of U937 cells previously transfected with siRNA specific for HIF-1α or with control siRNA attached to MSCs were counted. U937 cells incubated for 4 h in the presence or absence of 1 ng/ml sLR11 after preincubation for 24 h under normoxic or hypoxic conditions were subjected to analyses of their adhesion to plates coated with MSCs as described under “Experimental Procedures.” Data are shown as -fold increase compared with control cells in the absence of sLR11 under normoxia. Data are presented as mean ± S.D. (n = 3). *, p < 0.05; ns, not significant.

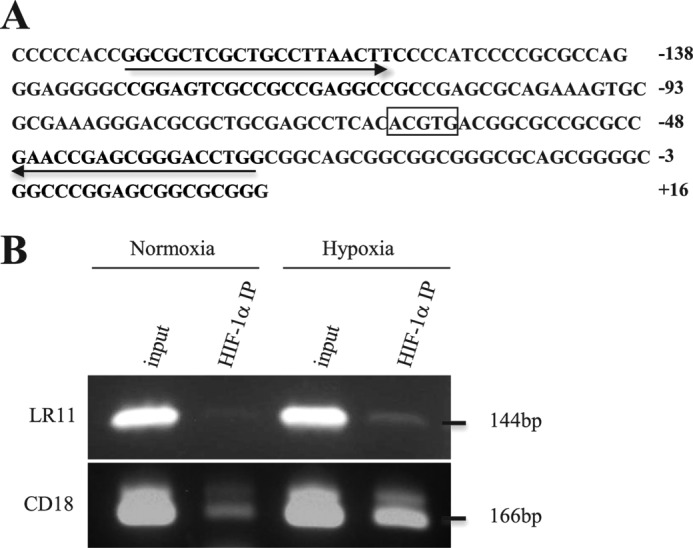

Hypoxia Induces HIF-1α Binding to the Potential Binding Site in LR11 Promoter

We finally investigated the molecular mechanism underlying the interaction between the adhesion modulator of hematological cells, LR11, and the hypoxia-induced molecule, HIF-1α. HIF-1 has been shown to be a dominant effector of changes in transcription in response to hypoxia (39). In this context, we identified a potential HIF-1-binding site in the human LR11 gene promoter sequence spanning 5000 bp before the LR11 transcription start point. This site contains the HIF-1 core sequence 5′-ACGTG-3′ (40) between nucleotides −65 and −61 (Fig. 7A). We therefore performed chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) analysis to determine whether HIF-1α binds to this region of the LR11 promoter in U937 cells subjected to hypoxic conditions. As shown in Fig. 7B, ChIP analysis of nuclei derived from U937 cells grown under hypoxia revealed an increased level of an amplified 144-bp product corresponding to the region encompassing the potential HIF-1 binding compared with the nuclei from cells in normoxia. The pattern of amplified products was similar to that for the HIF-1-binding site in the promoter of CD18 (32), whereas no significant differences were observed in preimmunoprecipitation input samples between normoxia and hypoxia. These results strongly suggest that HIF-1α binds to the proximal 144-bp LR11 promoter in a region that bears the potential HIF-1-binding site and that this binding is induced by hypoxia.

FIGURE 7.

Binding of HIF-1α to the potential binding site in the CD18 promoter. A, the nucleotide sequence including a potential HIF-1α binding site within the LR11 gene promoter is shown. The motif 5′-ACGTG-3′ spanning nucleotides −65 to −61 is boxed, and the sequences corresponding to the forward and reverse primers are shown with arrows. B, HIF-1α binding to the LR11 and CD18 promoter in normoxic and hypoxic conditions was examined using ChIP analysis in U937 cells. Chromatin-associated DNA (input) prior to immunoprecipitation with anti-HIF-1α antibody was used for PCR controls. The amplified products were consistent with the expected size of fragments for LR11 (144 bp) and CD18 (166 bp) promoters, and the amplified sequences were confirmed to be identical to those expected, respectively. The image shown is representative of three independent experiments.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we have shed light on the mechanism underlying the regulation of HSPC homeostasis by LR11 under the hypoxic conditions found in the BM. Hypoxia increases the level of LR11 in, and of sLR11 produced by, undifferentiated leukemic U937 and c-Kit+ Lin− cells. LR11 levels correlate with the extent of adhesion of HSPCs and U937 cells to stromal cells, and exogenously added sLR11 enhances HSPC adhesion to BM stromal cells. sLR11 originates from cellular LR11, and therefore the induction of LR11 under hypoxic conditions is crucial for regulating the adhesion of HSPCs. Interestingly, previous studies have shown that uPAR expression is induced by hypoxia in cultured hematological cells (19). Furthermore, using uPAR-deficient mice, Tjwa et al. reported that membrane-anchored uPAR regulates HSPC adhesion and BM engraftment (17), and we have shown that sLR11 binds to and co-localizes with uPAR on the cell surface of SMCs (41). On the basis of these findings, we now demonstrate that the hypoxia-induced increase in LR11 was accompanied by an elevated level of uPAR, which forms a complex with LR11, and leads to enhanced HIF-1α-dependent adhesion of HSPCs. Taken together, these data suggest that the HIF-1α-mediated induction of LR11 expression by the hypoxic conditions in endosteal sites plays a key role in the adhesion of immature hematological cells to stromal cells via modulation of uPAR activity.

We suggest that the regulatory pathway operates via an increase of LR11, enhanced release of sLR11, and subsequent binding of uPAR to the cell surface of HSPCs in an autocrine and/or paracrine fashion. In this context, we showed previously that sLR11 derived from the cell surface enhances cell adhesion through the activation of uPAR and integrin-mediated signals (21, 41, 42). On the other hand, LR11 in intracellular vesicles (SorLA) is important for the intracellular traffic of amyloidβ protein in neurons (43), and single nucleotide polymorphisms in the LR11/SORL1 gene and/or sLR11 levels in the cerebrospinal fluid have been reported to be a prospective marker of Alzheimer disease (44, 45). Thus, both the released soluble form and the intracellular vesicle-enclosed form of LR11 may contribute to the regulation of adhesion properties of HSPCs under hypoxic conditions.

The present study revealed a high sensitivity of HSPCs, but not of mature hematological cells, to hypoxic conditions (see Fig. 1). Together with the previous observations that sLR11 is produced only by immature SMCs and not in mature SMCs in atherosclerotic arteries (21) and that high levels of LR11 mRNA are expressed in human CD34+ CD38− immature hematopoietic progenitors (26), sLR11 released from immature cells may strengthen cell attachment to other stromal cells or extracellular matrices. In this context, preliminary results suggest that sLR11 is a potent enhancer of TNF-α-induced attachment of hematological cells to stromal cells in response to G-CSF treatment.4

The pO2 in BM is ∼55 mmHg, and the oxygen saturation is 87.5% (46). Several studies have suggested that long term HSCs reside mainly in the endosteal sites of the BM, in which the pO2 is very low (3, 6). Cell biological studies using HS(P)Cs indicated that their functions as well as their quiescence state are maintained most effectively under hypoxic conditions (10, 47–52). Hypoxia stabilizes the HIF-1α protein, a master regulator of oxygen homeostasis, and activates HIF-1α-mediated signals in HSCs (48, 53, 54). Furthermore, leukocyte adhesion to activated endothelial cells was shown to be HIF-1α-dependent (32). However, acute severe hypoxia induces HIF-1α-independent cell adhesion of monocytes/macrophages to endothelial cells (55). Therefore, although the hypoxia-mediated LR11 expression clearly is regulated by HIF-1α, the possible roles of HIF-independent cascades in LR11 regulation need to be investigated further. In any case, the current observation of HIF-1α-dependent regulation of LR11 expression contributes novel details to our understanding of the mechanism(s) underlying hypoxia-inducible adhesion of U937 cells to endothelial cells in the stem cell niche.

Acknowledgment

We thank Dr. M. Watanabe (Tokyo New Drug Research Laboratories, Pharmaceutical Division, Kowa Co., Ltd.) for excellent technical assistance.

This work was supported in part by Health and Labor Sciences Research Grants for Translational Research, Japan (to H. B.), and by grants from the Japanese Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science, and Technology (to H. B.).

N. Shimizu, K. Nishii, C. Nakaseko, M. Jiang, M. Takeuchi, W. J. Schneider, and H. Bujo, unpublished observation.

- HSPC

- hematopoietic stem and progenitor cell

- BM

- bone marrow

- HIF

- hypoxia-inducible factor

- HSC

- hematopoietic stem cell

- MSC

- mesenchymal stem cell

- pO2

- partial pressure of oxygen

- SMC

- smooth muscle cell

- uPAR

- urokinase-type plasminogen activator receptor.

REFERENCES

- 1. Suda T., Takubo K., Semenza G. L. (2011) Metabolic regulation of hematopoietic stem cells in the hypoxic niche. Cell Stem Cell 9, 298–310 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Lévesque J. P., Helwani F. M., Winkler I. G. (2010) The endosteal “osteoblastic” niche and its role in hematopoietic stem cell homing and mobilization. Leukemia 24, 1979–1992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Chow D. C., Wenning L. A., Miller W. M., Papoutsakis E. T. (2001) Modeling pO2 distributions in the bone marrow hematopoietic compartment. II. Modified Kroghian models. Biophys. J. 81, 685–696 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Calvi L. M., Adams G. B., Weibrecht K. W., Weber J. M., Olson D. P., Knight M. C., Martin R. P., Schipani E., Divieti P., Bringhurst F. R., Milner L. A., Kronenberg H. M., Scadden D. T. (2003) Osteoblastic cells regulate the haematopoietic stem cell niche. Nature 425, 841–846 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Zhang J., Niu C., Ye L., Huang H., He X., Tong W. G., Ross J., Haug J., Johnson T., Feng J. Q., Harris S., Wiedemann L. M., Mishina Y., Li L. (2003) Identification of the haematopoietic stem cell niche and control of the niche size. Nature 425, 836–841 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Arai F., Hirao A., Ohmura M., Sato H., Matsuoka S., Takubo K., Ito K., Koh G. Y., Suda T. (2004) Tie2/angiopoietin-1 signaling regulates hematopoietic stem cell quiescence in the bone marrow niche. Cell 118, 149–161 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Parmar K., Mauch P., Vergilio J. A., Sackstein R., Down J. D. (2007) Distribution of hematopoietic stem cells in the bone marrow according to regional hypoxia. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 104, 5431–5436 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Simsek T., Kocabas F., Zheng J., Deberardinis R. J., Mahmoud A. I., Olson E. N., Schneider J. W., Zhang C. C., Sadek H. A. (2010) The distinct metabolic profile of hematopoietic stem cells reflects their location in a hypoxic niche. Cell Stem Cell 7, 380–390 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Takubo K., Goda N., Yamada W., Iriuchishima H., Ikeda E., Kubota Y., Shima H., Johnson R. S., Hirao A., Suematsu M., Suda T. (2010) Regulation of the HIF-1α level is essential for hematopoietic stem cells. Cell Stem Cell 7, 391–402 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Shima H., Takubo K., Tago N., Iwasaki H., Arai F., Takahashi T., Suda T. (2010) Acquisition of G0 state by CD34-positive cord blood cells after bone marrow transplantation. Exp. Hematol. 38, 1231–1240 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Trumpp A., Essers M., Wilson A. (2010) Awakening dormant haematopoietic stem cells. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 10, 201–209 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Papayannopoulou T., Priestley G. V., Nakamoto B. (1998) Anti-VLA4/VCAM-1-induced mobilization requires cooperative signaling through the kit/m-kit ligand pathway. Blood 91, 2231–2239 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Heissig B., Hattori K., Dias S., Friedrich M., Ferris B., Hackett N. R., Crystal R. G., Besmer P., Lyden D., Moore M. A., Werb Z., Rafii S. (2002) Recruitment of stem and progenitor cells from the bone marrow niche requires MMP-9-mediated release of kit-ligand. Cell 109, 625–637 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Driessen R. L., Johnston H. M., Nilsson S. K. (2003) Membrane-bound stem cell factor is a key regulator in the initial lodgment of stem cells within the endosteal marrow region. Exp. Hematol. 31, 1284–1291 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Bradfute S. B., Graubert T. A., Goodell M. A. (2005) Roles of Sca-1 in hematopoietic stem/progenitor cell function. Exp. Hematol. 33, 836–843 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Suzuki A., Andrew D. P., Gonzalo J. A., Fukumoto M., Spellberg J., Hashiyama M., Takimoto H., Gerwin N., Webb I., Molineux G., Amakawa R., Tada Y., Wakeham A., Brown J., McNiece I., Ley K., Butcher E. C., Suda T., Gutierrez-Ramos J. C., Mak T. W. (1996) CD34-deficient mice have reduced eosinophil accumulation after allergen exposure and show a novel cross-reactive 90-kDa protein. Blood 87, 3550–3562 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Tjwa M., Sidenius N., Moura R., Jansen S., Theunissen K., Andolfo A., De Mol M., Dewerchin M., Moons L., Blasi F., Verfaillie C., Carmeliet P. (2009) Membrane-anchored uPAR regulates the proliferation, marrow pool size, engraftment, and mobilization of mouse hematopoietic stem/progenitor cells. J. Clin. Invest. 119, 1008–1018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Béné M. C., Castoldi G., Knapp W., Rigolin G. M., Escribano L., Lemez P., Ludwig W. D., Matutes E., Orfao A., Lanza F., van't Veer M., and EGIL, European Group on Immunological Classification of Leukemias (2004) CD87 (urokinase-type plasminogen activator receptor), function and pathology in hematological disorders: a review. Leukemia 18, 394–400 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Lewis J. S., Lee J. A., Underwood J. C., Harris A. L., Lewis C. E. (1999) Macrophage responses to hypoxia: relevance to disease mechanisms. J. Leukoc. Biol. 66, 889–900 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Yamazaki H., Bujo H., Kusunoki J., Seimiya K., Kanaki T., Morisaki N., Schneider W. J., Saito Y. (1996) Elements of neural adhesion molecules and a yeast vacuolar protein sorting receptor are present in a novel mammalian low density lipoprotein receptor family member. J. Biol. Chem. 271, 24761–24768 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Jiang M., Bujo H., Ohwaki K., Unoki H., Yamazaki H., Kanaki T., Shibasaki M., Azuma K., Harigaya K., Schneider W. J., Saito Y. (2008) Ang II-stimulated migration of vascular smooth muscle cells is dependent on LR11 in mice. J. Clin. Invest. 118, 2733–2746 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Ohwaki K., Bujo H., Jiang M., Yamazaki H., Schneider W. J., Saito Y. (2007) A secreted soluble form of LR11, specifically expressed in intimal smooth muscle cells, accelerates formation of lipid-laden macrophages. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 27, 1050–1056 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Jacobsen L., Madsen P., Moestrup S. K., Lund A. H., Tommerup N., Nykjaer A., Sottrup-Jensen L., Gliemann J., Petersen C. M. (1996) Molecular characterization of a novel human hybrid-type receptor that binds the α2-macroglobulin receptor-associated protein. J. Biol. Chem. 271, 31379–31383 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Hermey G., Sjøgaard S. S., Petersen C. M., Nykjaer A., Gliemann J. (2006) Tumour necrosis factor α-converting enzyme mediates ectodomain shedding of Vps10p-domain receptor family members. Biochem. J. 395, 285–293 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Bujo H., Saito Y. (2006) Modulation of smooth muscle cell migration by members of the low-density lipoprotein receptor family. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 26, 1246–1252 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Zhang X., Dormady S. P., Basch R. S. (2000) Identification of four human cDNAs that are differentially expressed by early hematopoietic progenitors. Exp. Hematol. 28, 1286–1296 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Sakai S., Nakaseko C., Takeuchi M., Ohwada C., Shimizu N., Tsukamoto S., Kawaguchi T., Jiang M., Sato Y., Ebinuma H., Yokote K., Iwama A., Fukamachi I., Schneider W. J., Saito Y., Bujo H. (2012) Circulating soluble LR11/SorLA levels are highly increased and ameliorated by chemotherapy in acute leukemias. Clin. Chim. Acta 413, 1542–1548 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Matsuo M., Ebinuma H., Fukamachi I., Jiang M., Bujo H., Saito Y. (2009) Development of an immunoassay for the quantification of soluble LR11, a circulating marker of atherosclerosis. Clin. Chem. 55, 1801–1808 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Taira K., Bujo H., Hirayama S., Yamazaki H., Kanaki T., Takahashi K., Ishii I., Miida T., Schneider W. J., Saito Y. (2001) LR11, a mosaic LDL receptor family member, mediates the uptake of ApoE-rich lipoproteins in vitro. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 21, 1501–1506 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Katayama K., Wada K., Miyoshi H., Ohashi K., Tachibana M., Furuki R., Mizuguchi H., Hayakawa T., Nakajima A., Kadowaki T., Tsutsumi Y., Nakagawa S., Kamisaki Y., Mayumi T. (2004) RNA interfering approach for clarifying the PPARγ pathway using lentiviral vector expressing short hairpin RNA. FEBS Lett. 560, 178–182 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Zhong H., Simons J. W. (1999) Direct comparison of GAPDH, β-actin, cyclophilin, and 28S rRNA as internal standards for quantifying RNA levels under hypoxia. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 259, 523–526 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Kong T., Eltzschig H. K., Karhausen J., Colgan S. P., Shelley C. S. (2004) Leukocyte adhesion during hypoxia is mediated by HIF-1-dependent induction of β2 integrin gene expression. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 101, 10440–10445 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Sundström C., Nilsson K. (1976) Establishment and characterization of a human histiocytic lymphoma cell line (U-937). Int. J. Cancer 17, 565–577 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Arai F., Suda T. (2007) Maintenance of quiescent hematopoietic stem cells in the osteoblastic niche. Ann. N.Y. Acad. Sci. 1106, 41–53 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Jang Y. Y., Sharkis S. J. (2007) A low level of reactive oxygen species selects for primitive hematopoietic stem cells that may reside in the low-oxygenic niche. Blood 110, 3056–3063 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Krishnamachary B., Berg-Dixon S., Kelly B., Agani F., Feldser D., Ferreira G., Iyer N., LaRusch J., Pak B., Taghavi P., Semenza G. L. (2003) Regulation of colon carcinoma cell invasion by hypoxia-inducible factor 1. Cancer Res. 63, 1138–1143 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Lester R. D., Jo M., Montel V., Takimoto S., Gonias S. L. (2007) uPAR induces epithelial-mesenchymal transition in hypoxic breast cancer cells. J. Cell Biol. 178, 425–436 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Smith H. W., Marshall C. J. (2010) Regulation of cell signalling by uPAR. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 11, 23–36 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Wang G. L., Jiang B. H., Rue E. A., Semenza G. L. (1995) Hypoxia-inducible factor 1 is a basic-helix-loop-helix-PAS heterodimer regulated by cellular O2 tension. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 92, 5510–5514 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Benita Y., Kikuchi H., Smith A. D., Zhang M. Q., Chung D. C., Xavier R. J. (2009) An integrative genomics approach identifies hypoxia inducible factor-1 (HIF-1) target genes that form the core response to hypoxia. Nucleic Acids Res. 37, 4587–4602 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Zhu Y., Bujo H., Yamazaki H., Hirayama S., Kanaki T., Takahashi K., Shibasaki M., Schneider W. J., Saito Y. (2002) Enhanced expression of the LDL receptor family member LR11 increases migration of smooth muscle cells in vitro. Circulation 105, 1830–1836 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Zhu Y., Bujo H., Yamazaki H., Ohwaki K., Jiang M., Hirayama S., Kanaki T., Shibasaki M., Takahashi K., Schneider W. J., Saito Y. (2004) LR11, an LDL receptor gene family member, is a novel regulator of smooth muscle cell migration. Circ. Res. 94, 752–758 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Willnow T. E., Petersen C. M., Nykjaer A. (2008) VPS10P-domain receptors: regulators of neuronal viability and function. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 9, 899–909 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Rogaeva E., Meng Y., Lee J. H., Gu Y., Kawarai T., Zou F., Katayama T., Baldwin C. T., Cheng R., Hasegawa H., Chen F., Shibata N., Lunetta K. L., Pardossi-Piquard R., Bohm C., Wakutani Y., Cupples L. A., Cuenco K. T., Green R. C., Pinessi L., Rainero I., Sorbi S., Bruni A., Duara R., Friedland R. P., Inzelberg R., Hampe W., Bujo H., Song Y. Q., Andersen O. M., Willnow T. E., Graff-Radford N., Petersen R. C., Dickson D., Der S. D., Fraser P. E., Schmitt-Ulms G., Younkin S., Mayeux R., Farrer L. A., St George-Hyslop P. (2007) The neuronal sortilin-related receptor SORL1 is genetically associated with Alzheimer disease. Nat. Genet. 39, 168–177 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Ikeuchi T., Hirayama S., Miida T., Fukamachi I., Tokutake T., Ebinuma H., Takubo K., Kaneko H., Kasuga K., Kakita A., Takahashi H., Bujo H., Saito Y., Nishizawa M. (2010) Increased levels of soluble LR11 in cerebrospinal fluid of patients with Alzheimer disease. Dement. Geriatr. Cogn. Disord. 30, 28–32 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Harrison J. S., Rameshwar P., Chang V., Bandari P. (2002) Oxygen saturation in the bone marrow of healthy volunteers. Blood 99, 394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Cipolleschi M. G., Dello Sbarba P., Olivotto M. (1993) The role of hypoxia in the maintenance of hematopoietic stem cells. Blood 82, 2031–2037 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Danet G. H., Pan Y., Luongo J. L., Bonnet D. A., Simon M. C. (2003) Expansion of human SCID-repopulating cells under hypoxic conditions. J. Clin. Invest. 112, 126–135 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Ivanovic Z., Hermitte F., Brunet de la Grange P., Dazey B., Belloc F., Lacombe F., Vezon G., Praloran V. (2004) Simultaneous maintenance of human cord blood SCID-repopulating cells and expansion of committed progenitors at low O2 concentration (3%). Stem Cells 22, 716–724 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Hermitte F., Brunet de la Grange P., Belloc F., Praloran V., Ivanovic Z. (2006) Very low O2 concentration (0.1%) favors G0 return of dividing CD34+ cells. Stem Cells 24, 65–73 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Goodell M. A., Brose K., Paradis G., Conner A. S., Mulligan R. C. (1996) Isolation and functional properties of murine hematopoietic stem cells that are replicating in vivo. J. Exp. Med. 183, 1797–1806 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Krishnamurthy P., Ross D. D., Nakanishi T., Bailey-Dell K., Zhou S., Mercer K. E., Sarkadi B., Sorrentino B. P., Schuetz J. D. (2004) The stem cell marker Bcrp/ABCG2 enhances hypoxic cell survival through interactions with heme. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 24218–24225 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Kirito K., Fox N., Komatsu N., Kaushansky K. (2005) Thrombopoietin enhances expression of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) in primitive hematopoietic cells through induction of HIF-1α. Blood 105, 4258–4263 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Pedersen M., Löfstedt T., Sun J., Holmquist-Mengelbier L., Påhlman S., Rönnstrand L. (2008) Stem cell factor induces HIF-1α at normoxia in hematopoietic cells. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 377, 98–103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Winning S., Splettstoesser F., Fandrey J., Frede S. (2010) Acute hypoxia induces HIF-independent monocyte adhesion to endothelial cells through increased intercellular adhesion molecule-1 expression: the role of hypoxic inhibition of prolyl hydroxylase activity for the induction of NF-κB. J. Immunol. 185, 1786–1793 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]