Background: AMPK is essential for cellular energy homeostasis and a therapeutic target for metabolic disorders.

Results: Genetic deletion of catalytic subunits of AMPK reduces bone mass and AMPK negatively regulates osteoclastogenesis.

Conclusion: AMPK is a critical regulator of bone homeostasis.

Significance: Mechanistic elucidation of AMPK function in bone homeostasis has implications for bone health in therapeutic intervention of metabolic disorders.

Keywords: AMP-activated Kinase (AMPK), Bone, Osteoblasts, Osteoclast, Signal Transduction, Bone Homeostasis, RANK Signaling

Abstract

AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) is a key regulator of cellular and systemic energy homeostasis and a potential therapeutic target for the intervention of cancer and metabolic disorders. However, the role of AMPK in bone homeostasis remains incompletely understood. Here we assessed the skeletal phenotype of mice lacking catalytic subunits of AMPK and found that mice lacking AMPKα1 (Prkaa1−/−) or AMPKα2 (Prkaa2−/−) had reduced bone mass compared with the WT mice, although the reduction was less in Prkaa2−/− mice than in Prkaa1−/− mice. Static and dynamic bone histomorphometric analyses revealed that Prkaa1−/− mice had an elevated rate of bone remodeling because of increases in bone formation and resorption, whereas AMPKα2 KO-induced bone mass reduction was largely attributable to elevated bone resorption. In agreement with our in vivo results, AMPKα deficiency was associated with increased osteoclastogenesis in vitro. Moreover, we found that AMPKα1 inhibited the receptor activator of nuclear factor κB (RANK) signaling, providing an explanation for AMPK-mediated inhibition of osteoclastogenesis. Therefore, our findings further underscore the importance of AMPK in bone homeostasis, in particular osteoclastogenesis, in young adult mammals.

Introduction

AMPK3 is an evolutionarily conserved serine/threonine kinase and exists as heterotrimeric complexes comprising a catalytic α subunit and noncatalytic β and γ subunits. The mammalian genome has seven genes that encode various isoforms of all three subunits (α1, α2, β1, β2, γ1, γ2, and γ3) that can form twelve different AMPK holoenzymes (1–4). AMPK plays a critical role in the maintenance of cellular energy homeostasis. AMPK is activated by a number of physiological conditions that increase the ratio of AMP to ATP including glucose deprivation and hypoxia, as well as by nucleotide-independent stimuli. Phosphorylation at Thr-172 within the activation loop of the kinase domain of the α subunit is a prerequisite for AMPK activation (5). The activated AMPK phosphorylates various downstream substrates and leads to either activation or inhibition of those downstream targets. The net effect is the inhibition of energy (e.g., ATP)-consuming cellular processes and stimulation of energy-producing processes. This mechanism is conserved from unicellular to complex multicellular organisms. Therefore, along with the notion that AMPK is present ubiquitously in various tissues, AMPK is also recognized as a key regulator of metabolism for whole body energy homeostasis. Great endeavors have been made to elucidate the functions and regulation of AMPK in the past decade. The current prevailing view is that AMPK is implicated in many fundamental biological processes by integrating both intracellular and extracellular signals, including growth factors, cytokines, hormones, nutrients, and cellular stress. Accordingly, clinical drugs and experimental therapeutic candidates that directly or indirectly modulate the AMPK-dependent intracellular signaling pathways have garnered particular attention for the treatment of metabolic syndromes.

Bone is a dynamic organ that is remodeled continuously throughout the lifetime and is susceptible to an alteration in metabolic energy status and physiological circumstances. Recent studies revealed that bone metabolism is subject to central regulation by the brain and closely linked to whole body energy homeostasis (6–12). The definite function of AMPK remains to be established in bone despite several studies in vitro and in vivo (12). Furthermore, most of the studies on the role of AMPK in bone are largely explained by way of AMPK function in osteoblasts. Interestingly, there has been contradictory evidence among published results regarding AMPK regulation of osteoblast differentiation. A study in primary osteoblasts and MC3T3-E1 osteoblastic cells found that phosphorylation of AMPK is significantly decreased during osteoblastic differentiation and that matrix mineralization is significantly inhibited by activated AMPK (13). Two other independent studies showed that metformin administration enhances osteogenic differentiation of bone marrow progenitor cells and stimulates bone lesion regeneration, whereas aminoimidazole carboxamide ribonucleotide (AICAR) treatment causes significant bone loss (14, 15). These results are puzzling, given that both compounds are known to activate AMPK (16, 17) and present a concern relating to the specificity and off target effects of metformin and AICAR. Although the underlying mechanism by which AMPK inhibits osteoclast formation still remains to be elucidated, several reports have demonstrated potential roles of AMPK in osteoclasts (14, 18–20).

Here, we sought to perform a more comprehensive characterization of the role of AMPK in bone maintenance by studying mice lacking each isoform of the AMPK catalytic subunits. We found that AMPKα1 and AMPKα2 are negative regulators of bone mass and osteoclastogenesis. We also showed that AMPKα1 inhibited RANK signaling in osteoclast precursors. Therefore, our study provides further insight into the role of AMPK in the regulation of bone metabolism, which may facilitate AMPK-based therapeutic interventions for bone disorders related to metabolic diseases.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Experimental Animals

All of the mice were housed in a temperature controlled room with a light/dark cycle of 12 h. All of the mice had free access to sterilized water and were fed standard laboratory chow ad libitum at the Yale University Animal Care Facilities in accordance with approved procedures. Prkaa1−/− mice and Prkaa2−/− mice were generated as described previously (21–23) and maintained on a C57BL/6 background. Prkaa1−/− mice and Prkaa2−/− mice were generated from the intercross of Prkaa1+/− and Prkaa2+/− mice, respectively. Genotyping of mice was performed at 3 weeks of age by PCR using tail genomic DNA as templates. All of the experiments were performed according to the protocol approved by Yale University's Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Bone Sample Preparation

Bone samples for ex vivo measurements were collected from 3-month-old male mice. For dynamic histomorphometry, all of the subject animals were administered 30 mg of calcein/kg of body weight via intraperitoneal injections 7 and 2 days prior to euthanasia. The mice were sacrificed by CO2 asphyxiation. Long bones (femurs and tibiae) were collected, cleaned free of soft tissues, and fixed in 70% ethanol. The right femurs were used for measurements with microcomputed tomography (μCT) and then processed for methylmethacrylate embedding for histological staining and subsequent histomorphometry. For assessment of osteoclasts in vivo, the tibiae were fixed with 2% paraformaldehyde mixed with 0.1% glutaraldehyde in 1× PBS for an hour followed by decalcification in 10% EDTA for 6 days at 4 °C. The decalcified bones were rinsed with 1× PBS three times for 5 min each and postfixed in cold 70% ethanol and processed for paraffin embedding. 5-μm-thick sections were deparaffinized and stained for tartrate-resistant acid phosphatase (TRAP) (24) with an acid phosphatase leukocyte kit (Sigma) following the manufacturer's recommended protocol and counterstained with eosin and mounted for imaging and histomorphometry.

Microcomputed Tomography

Femur morphometry was quantified using cone beam microfocus x-ray computed tomography (μCT40; Scanco Medical AG, Bassersdorf, Switzerland) as described previously (25). Serial tomographic images were acquired, and three-dimensional images were reconstructed and used to determine the parameters. Trabecular morphometry was characterized by measuring the bone volume fraction (BV/TV), trabecular thickness, trabecular number, and trabecular separation. Cortical measurements included average cortical thickness, cross-sectional area of cortical bone, subperiosteal cross-sectional area, and marrow area.

Bone Histology and Histomorphometry

Fixed tibiae were embedded in methylmethacrylate resin as described previously (26), and 5-μm-thick longitudinal sections were obtained using a rotation microtome (Leica, Heidelberg, Germany). The sections were deplasticized and stained with 0.1% toluidine blue. Thick sections (10 μm) were also cut and left unstained for dynamic histomorphometry with epifluorescence imaging of calcein labels. Histomorphometric analysis of proximal tibial metaphysis was performed using the Osteomeasure system (OsteoMetrics Inc., Atlanta, GA) interfaced with an Olympus light/epifluorescent microscope and video subsystem. The region of interest in the proximal tibial metaphysis started ∼0.2 mm distal from the growth plate to exclude the primary spongiosa. All of the histomorphometric parameters described in this study followed the guidelines described in the Report of the American Society of Bone and Mineral Research Committee (27).

Osteoclast Culture and Quantification

Bone marrow-derived macrophages (BMMs) were used as osteoclast progenitors (28). The mice were sacrificed by CO2 asphyxiation and long bones (femurs, tibiae, and humeri) were aseptically removed and dissected free of soft tissues. The bone ends were cut, and the marrow cavity was flushed via slow injection of α-MEM using a 27-gauge needle. The cell suspension was sieved through a cell strainer (70 μm). The cells (2 × 107 cells/100-mm tissue culture dish) were then incubated in medium (α-MEM, 10% FBS (Gemini Bio-Products West Sacramento, CA), 100 IU/ml penicillin, and 100 μg/ml streptomycin) for 12–18 h to remove adherent cells. The nonadherent cells were then harvested, replated (1.5 × 107 cells/100-mm tissue culture dish), and cultured for 3 days in the presence of 1/10 volume of L929 conditioned medium, which was used as a source of macrophage colony-stimulating factor (M-CSF) (29). To harvest BMMs, the cells were rinsed with cold 1× PBS to remove floating cells (including dead cells) and incubated in cold 1× PBS (Ca2+,Mg2+-free and 0.5 mm EDTA) on ice for 20 min. The cells were then harvested by gently scraping with a cell scraper and replated on 96-well tissue culture plates in a density of 1 × 105 cells/well with culture medium supplemented with M-CSF (25 ng/ml; Peprotech, Rocky Hill, NJ) and receptor activator of nuclear factor κB ligand (RANKL) (100 ng/ml; Peprotech). For TRAP staining, the cells were fixed in a mixture of citrate (6.75 mm), acetone (65%), and formalin (3.7%) for 90 s and washed with 1× PBS three times at room temperature. TRAP staining solution was prepared following the manufacturer's recommended protocol (Sigma). The cells were incubated in the TRAP staining solution for 15 min at 37 °C, and the reaction was terminated by rinsing the cells with distilled water. The stained cells were air dried and photographed with a conventional microscope equipped with a video camera (Olympus). Quantification of multinucleated TRAP-positive osteoclasts was performed by analyzing the images with MetaMorph software (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA). TRAP-positive multinucleated (>3 nuclei) cells were considered mature osteoclasts.

Real Time Quantitative PCR

Total RNA was extracted using a RNeasy kit (Qiagen) at the indicated time points during osteoclast culture experimentation. The quantity of total RNA was measured using a NanoDrop spectrophotometer (Thermo Scientific, Wilmington, DE). RNA integrity was evaluated by agarose-formaldehyde electrophoresis. RNA preparation displayed the characteristic pattern of nondegraded cellular RNA with distinct ribosomal RNA bands, having a 28 S band twice the intensity of the 18 S band. RNA was reverse transcribed (250 ng of total RNA in 10 μl of reverse transcription reaction) using the iScript cDNA synthesis kit (Bio-Rad). The cDNA samples were diluted 20-fold with nuclease-free water and used as a template for real time quantitative PCR with 2× SYBR Green master mix and oligonucleotide primers. The oligonucleotide primers were designed using PerlPrimer (30). Quantitative real time PCR was performed using MyIQ single-color real time PCR detection system (Bio-Rad). Standard PCR conditions were 95 °C (5 min) and then 40 cycles of 94 °C (10 s), 60 °C (20 s), and 72 °C (15 s), followed by the standard denaturation curve with 0.5 °C increments for 70 cycles. The threshold cycle number (31) for each PCR is determined by setting the same threshold value across all PCR arrays. For data normalization, β-actin was selected as the reference endogenous control gene. The comparative CT method was used to calculate relative quantification of gene expression. The relative amount of transcripts for each gene in samples A and B was normalized to β-actin and calculated as follows: ΔCT is the log2difference between the gene and the reference gene and is obtained by subtracting the average CT of β-actin from the CT value of the gene. The log2fold change between the two samples was obtained using the following formula: ΔΔCT = the average ΔCT of sample B − the average ΔCT of sample A, and their fold difference = 2−ΔΔCT. For each gene, the fold change between the two samples was generated by calculating the ratio of the average of the normalized signals for all sample B replicates to the average of the normalized signals for all sample A replicates. The relative expression levels were plotted in fold change setting “WT at day 0” to 1.

Western Blot Analysis

Aliquots of BMMs were serum-starved for 3 h and treated with the indicated reagents. The cells were then rinsed once with cold 1× PBS and lysed in radioimmune precipitation assay buffer (10 mm Tris, pH 8.0, 140 mm NaCl, 1 mm EDTA, 0.5 mm EGTA, 1% Triton X-100, 0.1% sodium deoxycholate, 0.1% SDS) supplemented with cOmplete® protease inhibitor mixture (Roche Applied Science), phosphatase inhibitor mixture (Roche Applied Science), and 1 mm phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride. The lysates were cleared by 5 min of centrifugation at 13,000 rpm at 4 °C, and then total protein concentration was measured using the BCA protein assay kit (Pierce). The lysates were mixed with SDS-PAGE sample buffer (62.5 mm Tris, pH 6.8, 2% SDS, 10% glycerol, 0.01% bromphenol blue, and 50 mm DTT), denatured for 5 min at 95 °C, and then resolved by SDS-PAGE. The resolved proteins were transferred to nitrocellulose membranes (Whatman) by electroblotting and subjected to immunoblotting with the indicated antibodies. The blots were developed using SuperSignal West Pico or Femto Chemiluminescent Substrate (Pierce) and exposed and imaged using the Gel-Doc imaging system (Bio-Rad). β-Actin served as an internal control for equal amount loading of proteins. Primary antibodies used in this study were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology (Beverly, MA). AMPKα2-specific antibody was a generous gift from Dr. Grahame Hardie at the University of Dundee (Dundee, UK). Horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies were purchased from Jackson ImmunoResearch (West Grove, PA).

Proliferation Assay

BMMs were seeded in a density of 60,000 cells/cm2 and labeled with 10 μm BrdU in 1- PBS (pH 7.4) for 4 h. The BrdU incorporation was detected by chemiluminescent ELISA method using a BrdU Cell Proliferation ELISA kit (Roche Applied Science) following the manufacturer's protocol.

Statistical Analyses

The data were analyzed for statistical significance using student t test. The results are presented as the means and S.E. The difference between the experimental groups (WT versus Prkaa1−/−, or WT versus Prkaa2−/−) was considered to be statistically significant, if p < 0.05.

RESULTS

Genetic Deletion of AMPK Catalytic Subunits Reduces Bone Mineral Density and Bone Mass

To examine the role of AMPK in bone mass regulation, 3-month-old AMPKα-null and age-matched WT mice were used. This particular age was chosen because mice at this age do not exhibit statistically significant changes in bone mineral density (32). Of note, there were no significant changes in body weight and size associated with the loss of AMPKα1 or AMPKα2 at the age for this study (data not shown), suggesting that germ line deletion of catalytic subunit of AMPK may not have a significant impact on skeletal development before adulthood.

μCT analysis of femurs revealed that absence of AMPKα1 caused a marked decrease in bone mass (Fig. 1, A–C). The bone mass documented by bone fraction (BV/TV) in Prkaa1−/− mice was 16%, whereas it was 25% in age-matched WT mice (Fig. 1B). AMPKα1 deficiency did not have a significant impact on the cortical bone thickness, at least, with the sample size of this study (n = 7) (data not shown). Prkaa1−/− mice also had lower apparent density than their WT counterparts (Fig. 1C). The reduction in bone mass and bone density was also observed in Prkaa2−/− mice (Fig. 1, D and E), although these changes were less pronounced than that in Prkaa1−/− mice. The reduction of bone mass in Prkaa1−/− and Prkaa2−/− mice seemed to occur mainly in cancellous bones, as revealed by bone histomorphometric analysis of proximal metaphysic of tibia (Fig. 2). In addition, the histomorphometric analysis showed that trabecular number and thickness were decreased, whereas trabecular separation was increased in Prkaa1−/− bones compared with WT (Fig. 2, A–E), which corroborates the μCT results. Prkaa2−/− mice also displayed a reduction in bone mass in cancellous bone (Fig. 2, F–I). Again, the extent of decrease appeared to be less than the difference between Prkaa1−/− and WT mice. There were only marginal differences in cortical bone mass between AMPKα-null and WT mice, supporting the conclusion that the major alterations in bone mass by AMPKα deficiency primarily take place in cancellous bone, where higher rates of bone remodeling occur in young adult bones.

FIGURE 1.

Genetic deletion of catalytic subunit of AMPK reduces bone mineral density and mass. A–C, μCT analysis of femurs from 3-month-old male mice of Prkaa1−/− and WT. A, representative three-dimensional reconstructed μCT images of the femoral trabecular compartment. Scale bars, 0.5 mm. B, percentage of BV/TV of Prkaa1−/− and WT. C, apparent (App.) density of Prkaa1−/− and WT. Hydroxyapatite (HA)-calibrated true volumetric mineral density of trabecular bone was normalized to the tissue volume of selected region of interest. The graphs were plotted with the means ± S.E., n = 7, p < 0.05 versus WT. D–F, μCT analysis of femurs from 3.5-month-old male mice of Prkaa2−/− and WT. D, representative three-dimensional reconstructed μCT images of the femoral trabecular compartment. Scale bars, 0.5 mm. E, percentage of BV/TV of Prkaa2−/− and WT. F, apparent density of Prkaa2−/− and WT. The data in E and F are presented as the means ± S.E., n = 12 in each group of mice. *, p < 0.05 versus WT.

FIGURE 2.

Genetic deletion of catalytic subunit of AMPK reduces cancellous bone mass. A–E, static histomorphometry of the proximal tibiae from 3-month-old male mice of Prkaa1−/− and WT. A, representative images of toluidine blue-stained histological tibial bone sections. Scale bars, 0.5 mm. B, percentage of trabecular BV/TV. C, trabecular bone thickness (Tb. Th.). D, trabecular number (Tb. N.). E, trabecular separation (Tb. Sp.). F–I, static histomorphometry of the proximal tibiae for 3.5-month-old male mice of Prkaa2−/− and WT. F, percentage of trabecular BV/TV. G, trabecular bone thickness (Tb. Th.). H, trabecular number (Tb. N.). I, trabecular separation (Tb. Sp.). The data in B–I are presented as the means ± S.E., The sample size was the same as in Fig. 1. *, p < 0.05 versus WT.

Effects of AMPKα Deficiency on Bone Formation and Resorption

The net decrease in bone mass associated with the loss of AMPK catalytic subunits could be the result of a decrease in bone formation by osteoblasts or an increase in bone resorption by osteoclasts. We first examined anabolic aspects of bone remodeling by assessing bone formation. The mice were administered calcein via intraperitoneal injections 7 and 2 days prior to euthanasia. We found that Prkaa1−/− mice had an increase in mineral apposition rate (%) and bone formation rate (μm3/μm2/day) compared with WT mice (Fig. 3, A–C). Osteoblast surface per bone surface, another index of bone formation, was also increased in Prkaa1−/− mice (Fig. 3D) over WT mice. The catabolic aspects of bone remodeling were then examined by histological staining of tibiae for TRAP, an osteoclast marker, which revealed that Prkaa1−/− mice had a significantly higher number of TRAP-positive osteoclasts on the surface of trabecular bones than WT mice (Fig. 3, E and F). Osteoclast surface, an index of bone resorption, was also higher in Prkaa1−/− mice compared with WT mice (Fig. 3G). Thus, AMPKα1 deficiency increased both bone formation and resorption. In other words, AMPKα1 deficiency accelerated the bone remodeling process with the increase in bone resorption outweighing the increase in bone formation, thus resulting in a net decrease in bone mass. AMPKα2 deficiency also led to an increased osteoclast surface and number but had little effect on bone formation parameters (Fig. 4). These results together indicate that AMPK catalytic subunits have differential effects on anabolic (bone formation) and catabolic (bone resorption) aspects of bone remodeling. Although AMPKα1 has been implicated in catabolic aspects of bone remodeling (14), our finding indicated that AMPKα1 also had a significant anabolic role, which may actually determine the phenotype of AMPKα1 deficiency. Our results also implicate AMPKα2 in catabolic regulation of bone remodeling. However, AMPKα2 is expressed at a significantly lower level in osteoclast precursor cells than AMPKα1 (supplemental Fig. S1). Thus, it is imperative to better understand the role of AMPKα deficiency on osteoclastogenesis.

FIGURE 3.

Effect of AMPKα1 deficiency on bone formation and resorption. A–C, dynamic histomorphometry of calcein double-labeled tibiae for WT and Prkaa1−/− mice. A, representative images of calcein double-labeled trabecular bone surfaces of WT and Prkaa1−/− mice. Scale bars, 100 μm. B, mineralizing surface per bone surface (MS/BS, %) of WT and Prkaa1−/− mice. C, bone formation rate per bone surface (BFR/BS) of WT and Prkaa1−/− mice. D, histomorphometric quantification of osteoblast surface per bone surface (Ob.S./BS) of WT and Prkaa1−/− mice. E, representative microscopic images of TRAP-stained tibial bone sections from WT and Prkaa1−/− mice. TRAP-positive osteoclasts are stained in purple on trabecular bone surface (black arrow). Scale bars, 100 μm. F, histomorphometric quantification for osteoclast number per bone perimeter (Oc.N/B.Pm) in WT and Prkaa1−/− mice. Histomorphomeric measurement of osteoclasts was made in the proximal tibial metaphysis starting ∼0.2 mm distal from the growth plate. The horizontal axis of rectangular region of interest was maintained parallel to the growth plate. G, osteoclast surface per bone surface (Oc.S/BS, %) in WT and Prkaa1−/− mice. *, p < 0.05 as compared with WT by t test.

FIGURE 4.

Effect of AMPKα2 deficiency on bone formation and resorption. A and B, histomorphometric quantification of osteoclasts for WT and Prkaa2−/− mice. A, osteoclast number per bone perimeter (Oc.N/B.Pm). B, osteoclast surface per bone surface (Oc.S/BS, %). C and D, dynamic histomorphometry of calcein double-labeled WT and Prkaa2−/− mice. C, bone formation rate per bone surface (BFR/BS) of WT and Prkaa2−/− mice. D, representative images of calcein double-labeled trabecular bone surfaces of WT and Prkaa2−/− mice. Scale bars, 100 μm. NS, not significant.

Deletion of AMPK Catalytic Subunit Augments Osteoclastogenesis in Vitro

We first investigated whether AMPK regulates osteoclasts autonomously by examining osteoclastogenesis of BMMs in vitro. BMMs from WT and Prkaa1−/− mice were cultured in the presence of M-CSF and induced to osteoclast differentiation by RANKL. TRAP-positive multinucleated cells were identified as osteoclasts. BMMs from Prkaa1−/− mice generated more and larger osteoclasts than WT cells after 6 days of culture with M-CSF and RANKL (Fig. 5A). Quantitative analyses further demonstrated that AMPKα1 deficiency resulted in increased size and number of the multinucleated cells (Fig. 5, B and C). Augmented osteoclastogenesis was also observed with AMPKα2-null cells (Fig. 5, D and E). These data indicate that both AMPK α subunits regulate osteoclastogenesis in vitro.

FIGURE 5.

Deletion of AMPK catalytic subunit augments osteoclastogenesis in vitro. A–C, bone marrow cells from WT and Prkaa1−/− mice were cultured in the presence of M-CSF until subconfluency. Then the BMMs were cultured in the media supplemented with M-CSF and RANKL for 6 days, and multinucleate osteoclasts were stained for TRAP. A, representative images of TRAP stained osteoclasts from WT and Prkaa1−/−. Scale bars, 100 μm. B, osteoclast number of WT and Prkaa1−/−. C, osteoclast size of WT and Prkaa1−/−. D and E, quantitation of osteoclasts derived from bone marrow cells from WT and Prkaa2−/− mice. D, osteoclast number of WT and Prkaa2−/−. E, osteoclast size of WT and Prkaa2−/−.

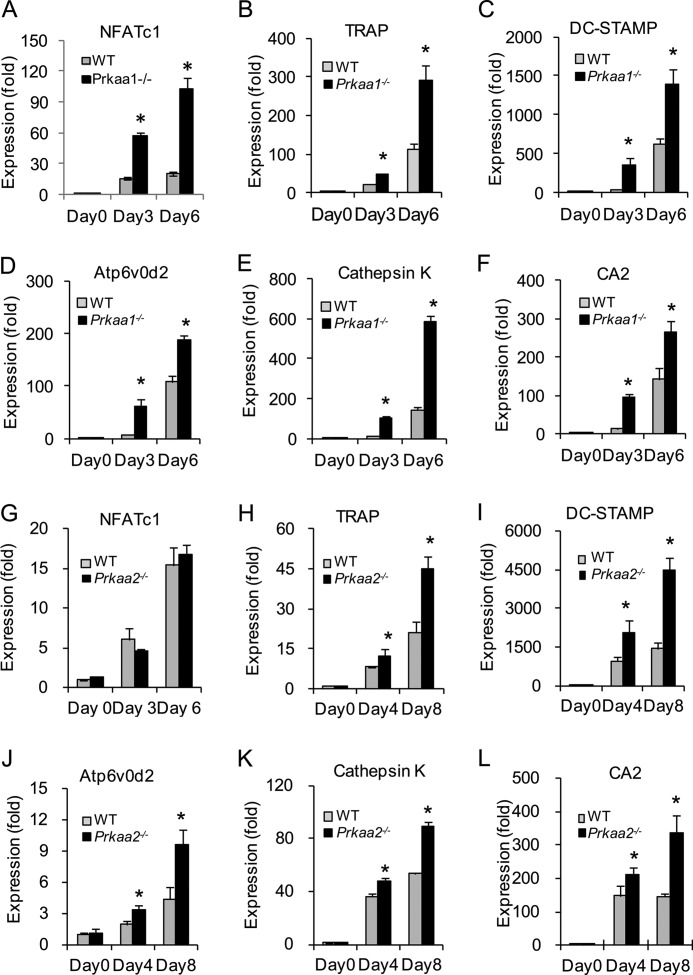

The increased osteoclastogenesis associated with the lack of either AMPKα subunit is accompanied by progressive up-regulation of osteoclastogenesis-associated gene expression (Fig. 6). Together with the significant up-regulation of NFATc1, the master transcription factor for osteoclastogenesis, the expression level of various osteoclastogenesis-associated genes, including TRAP, DC-STAMP (dendrocyte expressed seven transmembrane protein), Atp6v0d2 (ATPase, H+ transporting, lysosomal V0 subunit D2), cathepsin K, and CA2, was also higher in AMPKα-deficient cells than in WT cells (Fig. 6). Moreover, there was also an increase in the expression of genes related to bone resorbing activity of osteoclasts, including CA2, cathepsin K (Fig. 6, E, F, K, and L), ATP6i (T cell, immune regulator 1, ATPase, H+ transporting, lysosomal V0 protein A3 (Tcirg1)), and ClC-7 (chloride channel 7; data not shown). Similar results were obtained with AMPKα2-null cells (Fig. 6, G–L).

FIGURE 6.

Deletion of AMPK catalytic subunit increases expression of osteoclastogenesis-associated genes in vitro. A–F, real time quantitative PCR analysis of osteoclastogenesis-associated genes. Bone marrow cells from WT and Prkaa1−/− mice were cultured in the presence of M-CSF and RANKL. At days 0, 3, and 6, total RNA was isolated and subjected to reverse transcription and subsequent real time PCR. All of the PCRs were carried out in triplicate. The graph for each gene shows the mean values of fold changes compared with the expression level of WT at day 0. A, NFATc1. B, TRAP. C, DC-STAMP. D, Atp6v0d2. E, cathepsin K. F, CA2. G–L, real time quantitative PCR analysis of osteoclastogenesis-associated gene expression with total RNA from WT and Prkaa2−/− osteoclast cultures. G, NFATc1. H, TRAP. I, DC-STAMP. J, Atp6v0d2. K, cathepsin K. L, CA2. *, statistically significant difference between WT and KO at the indicated time point, p < 0.05.

The alteration in gene expression caused by the deficiency of the AMPK catalytic subunits led us to explore the effects of AMPKα deficiency on the RANK signaling, which initiates the differentiation process by inducing the transcription of these osteoclastogenic genes. BMMs from Prkaa1−/− and WT mice were cultured in the presence of M-CSF for 3 days, and RANKL-induced phosphorylation and activation of RANK signaling components were analyzed by subjecting the cell lysates to immunoblotting with specific antibodies. We found that RANKL elicited stronger phosphorylation of IKKα/β and MAPKs (p42/44 and p38) in AMPKα1-null cells than in WT cells (Fig. 7A), indicating that AMPKα1 may play a negative regulatory role for RANK signaling in these cells. This negative effect would explain the enhanced osteoclast differentiation of AMPKα1-null cells. However, AMPKα2 deficiency did not alter RANKL-induced phosphorylation of downstream signaling components (Fig. 7B). The fact that AMPKα1 deficiency diminished the level of Thr-172-phosphorylated AMPKα (Thr(P)-172) , whereas AMPKα2 deficiency had little effect, suggests that AMPKα1 accounts for the majority of the AMPK activity in BMMs. This is consistent with our observation that AMPKα1 is the predominantly expressed catalytic isoform in BMMs (supplemental Fig. S1). In addition, this suggests that RANK signaling may be primarily regulated by the AMPK activity, which is largely contributed by AMPKα1 in BMMs, and that AMPKα2 may regulate osteoclastogenesis via mechanisms different from AMPKα1 (see below for additional discussion). We also examined the effect of AMPKα1 deficiency on the proliferation of BMMs and found little effect (supplemental Fig. S2A). Additionally, we examined the effect of AMPKα1 deficiency on mammalian target of rapamycin complex 1 signaling, which regulates cell growth and is negatively regulated by AMPK in select cells. We found that the absence of AMPKα1 does not have a significant impact on the phosphorylation of S6K and S6, although the phosphorylation of acetyl-CoA carboxylase (ACC) was significantly diminished in AMPKα1-deficient cells (supplemental Fig. S2B). Thus, we conclude that AMPKα1 primarily regulates differentiation rather than growth of osteoclast precursor cells.

FIGURE 7.

AMPKα1 deficiency augments the RANK signaling in BMMs. A, BMMs from WT and Prkaa1−/− mice were starved in serum-free culture media for 3 h before being stimulated with 100 ng/ml of RANKL. The cell lysates were resolved by SDS-PAGE and then immunoblotted for phosphorylated forms of AMPKα1/2, IKKα/β, p38MAPK, and p42/44MAPK. β-Actin served as an internal control for equal loading of proteins on each lane. B, cell lysates of BMMs from WT and Prkaa2−/− mice were analyzed as in A for phos-IκBα and IκBα.

DISCUSSION

In the present study, we performed a comprehensive characterization of bone phenotypes of mice lacking AMPK catalytic subunits and demonstrated that genetic ablation of AMPK catalytic subunits results in reduced bone mass with the extent of observed bone mass reduction more remarkable in Prkaa1−/− mice than in Prkaa2−/− mice (Figs. 1 and 2). Moreover, the impact of AMPKα deficiency was more prominent in cancellous bone than in cortical bone, suggesting that the importance of AMPK in bone with higher turnover rates. The significance of AMPK in young adult bone homeostasis was more appreciable with Prkaa1−/− mice, which showed more remarkable bone mass reduction with alterations in both bone formation and bone resorption (Fig. 3). The increased bone formation and resorption reflects an accelerated rate of bone remodeling giving rise to a net decrease in bone mass in Prkaa1−/− mice. Therefore, the AMPK complex harboring AMPKα1 catalytic subunit is required for maintenance of the normal rate of bone remodeling in young adult mice. Our results coincide with a previous report that AMPKα1 deficiency causes a reduction in bone mass (16, 33). However, in contrast to our results, a reduction of cortical bone mass in Prkaa1−/− mice was detected. This discrepancy may be explained by the difference in sample sizes and/or the ages of the mice.

The importance of AMPK in bone physiology was more clearly observed via osteoclast-mediated phenotypes in Prkaa1−/− mice and Prkaa2−/− mice. Our study on the effect of AMPK deficiency in osteoclasts demonstrated that multinucleated osteoclast formation is increased in the absence of AMPK activity. AMPKα1 deficiency caused both accelerated differentiation and enhanced cell fusion. The latter was evidenced by the increased expression of Atp6v0d2 and DC-STAMP, which are essential for osteoclast fusion (34, 35). Lee et al. (20) showed that AMPK inhibition with compound C or AMPKα1 knockdown stimulates osteoclastogenesis, whereas AMPK activation has a negative effect on osteoclast development (18). Although our results suggest a negative regulatory role of AMPK in osteoclast formation and function, a definitive assessment of whether AMPK deletion would modulate osteoclastic resorption activities remains to be determined with in vitro assays. Delineation of the underlying mechanism suggested that AMPK inhibits the NFκB and MAPK pathways downstream of RANK (Figs. 6 and 7). Research in various cell types has revealed a role for AMPK in inhibiting the NFκB pathway (36–38). Constitutively active AMPKα1 suppresses the NFκB-mediated pathway and fatty acid-induced inflammation in macrophages, and this process could be reversed through expression of a dominant-negative AMPKα1 (39). Endothelial cells also express both α subunits of AMPK, and conflicting reports of their roles have also emerged (40). Consistent with our observations in osteoclast progenitor cells, overexpression of AMPKα1 or AMPK activation by AICAR also reduces NFκB signaling in aortic endothelial cells (41). A similar study in endothelial cells demonstrated that AMPK attenuates NFκB activation via direct phosphorylation of IKKβ on Ser-177 and Ser-181 by AMPKα2 but not AMPKα1 (40). Intriguingly, genetic deletion of tumor necrosis factor receptor-associated factor 6, a crucial adaptor molecule of RANK, generates lower levels of AMPK activity (42), whereas knockdown of TAK1, which is activated by tumor necrosis factor receptor-associated factor 6 and mediates IKKα/β activation, blocks RANKL-induced activation of AMPK in mouse BMMs (20).

Despite a previous report that AMPKα2 expression is undetectable in bone cells (14), we found that AMPKα2 was present at a detectable level in BMMs as shown by real time quantitative PCR and Western blot analysis (supplemental Fig. S1). A functional role for this expression was further supported by the observed reduction in bone mass in Prkaa2−/− mice, as well as increased osteoclast development in vivo and in vitro (Figs. 1, 2, and 4–6). AMPKα2 deficiency also elevates osteoclast formation, but no known signaling pathways downstream of RANK were altered in AMPKα2-null cells. In addition, AMPKα2 deficiency did not impair phosphorylation of ACC in osteoclasts (data not shown). There seems to be a novel pathway that is specifically mediated by the AMPK complex harboring AMPKα2 as a catalytic subunit. Thus, the underlying mechanism of AMPKα2-specific regulation of osteoclast formation remains to be elucidated. Taken together, our results suggest that AMPK-dependent signals are involved in osteoclast development.

Alteration in the osteoclast maturation rate in the absence of AMPK catalytic subunit establishes that AMPK has a cell autonomous effect on osteoclast development; however, systemic effects cannot be excluded. Genetic deletion of the AMPKβ1 subunit drastically reduces macrophage AMPK activity, suppressing the expression of mitochondrial enzymes and ACC phosphorylation, resulting in increased macrophage lipid accumulation and inflammation (43). This study also demonstrated that the decrease in AMPK activity in macrophages results in systemic inflammation. Thus, one can speculate that an increase in pro-inflammatory cytokines, which are known to positively regulate osteoclast development (44), contributes to the increased osteoclastogenesis in AMPKα-null cells. This is further supported by our data showing that AMPKα1-null cells fail to phosphorylate ACC (supplemental Fig. S2B).

Unlike in osteoclasts, AMPK function in osteoblasts remains controversial and requires further understanding. We observed that AMPKα1 deficiency increases osteoblast-mediated bone formation, whereas AMPKα2-deficient mice did not have a detectable alteration in bone formation in vivo (Fig. 4). Our osteoblastic cell culture study further demonstrated that AMPKα1 deficiency has a stimulatory effect on mineralized nodule formation in vitro (supplemental Fig. S3). This is in line with the report by Kasai et al. (13) that osteoblast differentiation is functionally associated with decreased AMPK activity. An explanation on AMPK-mediated regulation of osteoblast differentiation can be found in the study by Mao et al. (45). They showed that aP2 (adipocyte protein 2)-Cre-mediated conditional KO of ACC1 results in reduced bone formation caused by defective osteoblastogenesis (45). ACC catalyzes a crucial step of the fatty acid synthesis pathway, and phosphorylation of ACC by AMPK inhibits the enzymatic activity of ACC (46). In our cell culture-based study, phosphorylation of ACC is significantly reduced in AMPKα1-null cells, suggesting that increased ACC activity is attributable to the increased osteoblastogenesis in AMPKα1-null cells. Investigation of bone phenotypes in ACC knock-in mice, which harbor mutations in ACC1 and ACC2 at the sites of AMPK phosphorylation (Ser-79 and Ser-212, respectively), may elucidate the role of the AMPK-ACC pathway in bone cell biology and bone remodeling.

In summary, we demonstrate that AMPK catalytic subunits play a critical role in bone remodeling. Our in vitro bone cell culture experiments suggest that AMPKs have autonomous roles in osteoclastogenesis, whereas AMPKα1 may have an autonomous role in osteoblastogenesis. However, future studies testing the significance of these autonomous effects of AMPKs in vivo must be evaluated via tissue-specific deletion of AMPKα1 and AMPKα2. AMPK functions as a modulator for cellular and systemic energy homeostasis, and its dysregulation leads to a various pathological conditions, especially metabolic disorders. Current interest on AMPK as a therapeutic target for the treatment of metabolic disorders has made this particular kinase an important subject of study. As exemplified by the effects of anti-diabetes drugs such as metformin and thiazolidinediones, AMPK activation holds a great deal of potential to reverse metabolic abnormalities (47). Thus, this study highlights the potential role of AMPK in bone-related symptoms in similar pathological conditions. In addition, this study may provide insight into therapeutic intervention for aging-induced bone loss, because AMPK activity declines over time with aging (48). In conclusion, the impact of alteration of AMPK activity on bone homeostasis should be taken into consideration when AMPK activity modulators are applied to metabolic diseases, such as diabetes and cancer.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Dr. Grahame Hardie (The University of Dundee, Dundee, UK) for the generous gift of AMPKα1 and AMPKα2 antibodies. We thank Dr. Jackie Fretz and Miles Pfaff (Yale University) for critical reading of the manuscript.

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by a National Institutes of Health Grant AR046032 (to D. W.).

This article contains supplemental Figs. S1–S3.

- AMPK

- adenosine 5′-monophosphate-activated protein kinase

- RANK

- receptor activator of nuclear factor κB

- AICAR

- aminoimidazole carboxamide ribonucleotide

- μCT

- microcomputed tomography

- TRAP

- tartrate-resistant acid phosphatase

- BV/TV

- bone volume per tissue volume

- M-CSF

- macrophage-colony stimulating factor

- RANKL

- receptor activator of nuclear factor κB ligand

- BMM

- bone marrow-derived macrophage

- CA2

- carbonic anhydrase 2

- IKK

- inhibitor of κB kinase

- ACC

- acetyl-CoA carboxylase.

REFERENCES

- 1. Kemp B. E., Mitchelhill K. I., Stapleton D., Michell B. J., Chen Z. P., Witters L. A. (1999) Dealing with energy demand. The AMP-activated protein kinase. Trends Biochem. Sci. 24, 22–25 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Davies S. P., Carling D., Hardie D. G. (1989) Tissue distribution of the AMP-activated protein kinase, and lack of activation by cyclic-AMP-dependent protein kinase, studied using a specific and sensitive peptide assay. Eur. J. Biochem. 186, 123–128 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Birk J. B., Wojtaszewski J. F. (2006) Predominant α2/β2/γ3 AMPK activation during exercise in human skeletal muscle. J. Physiol. 577, 1021–1032 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Mahlapuu M., Johansson C., Lindgren K., Hjälm G., Barnes B. R., Krook A., Zierath J. R., Andersson L., Marklund S. (2004) Expression profiling of the γ-subunit isoforms of AMP-activated protein kinase suggests a major role for γ3 in white skeletal muscle. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 286, E194–E200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Ingebritsen T. S., Lee H. S., Parker R. A., Gibson D. M. (1978) Reversible modulation of the activities of both liver microsomal hydroxymethylglutaryl coenzyme A reductase and its inactivating enzyme. Evidence for regulation by phosphorylation-dephosphorylation. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 81, 1268–1277 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Karsenty G. (2006) Convergence between bone and energy homeostases. Leptin regulation of bone mass. Cell Metab. 4, 341–348 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Yadav V. K., Oury F., Suda N., Liu Z. W., Gao X. B., Confavreux C., Klemenhagen K. C., Tanaka K. F., Gingrich J. A., Guo X. E., Tecott L. H., Mann J. J., Hen R., Horvath T. L., Karsenty G. (2009) A serotonin-dependent mechanism explains the leptin regulation of bone mass, appetite, and energy expenditure. Cell 138, 976–989 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Ducy P., Amling M., Takeda S., Priemel M., Schilling A. F., Beil F. T., Shen J., Vinson C., Rueger J. M., Karsenty G. (2000) Leptin inhibits bone formation through a hypothalamic relay. A central control of bone mass. Cell 100, 197–207 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Takeda S., Elefteriou F., Levasseur R., Liu X., Zhao L., Parker K. L., Armstrong D., Ducy P., Karsenty G. (2002) Leptin regulates bone formation via the sympathetic nervous system. Cell 111, 305–317 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Ferron M., Wei J., Yoshizawa T., Del Fattore A., DePinho R. A., Teti A., Ducy P., Karsenty G. (2010) Insulin signaling in osteoblasts integrates bone remodeling and energy metabolism. Cell 142, 296–308 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Fulzele K., Riddle R. C., DiGirolamo D. J., Cao X., Wan C., Chen D., Faugere M. C., Aja S., Hussain M. A., Brüning J. C., Clemens T. L. (2010) Insulin receptor signaling in osteoblasts regulates postnatal bone acquisition and body composition. Cell 142, 309–319 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Jeyabalan J., Shah M., Viollet B., Chenu C. (2012) AMP-activated protein kinase pathway and bone metabolism. J. Endocrinol. 212, 277–290 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Kasai T., Bandow K., Suzuki H., Chiba N., Kakimoto K., Ohnishi T., Kawamoto S., Nagaoka E., Matsuguchi T. (2009) Osteoblast differentiation is functionally associated with decreased AMP kinase activity. J. Cell Physiol. 221, 740–749 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Quinn J. M., Tam S., Sims N. A., Saleh H., McGregor N. E., Poulton I. J., Scott J. W., Gillespie M. T., Kemp B. E., van Denderen B. J. (2010) Germline deletion of AMP-activated protein kinase β subunits reduces bone mass without altering osteoclast differentiation or function. FASEB J. 24, 275–285 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Molinuevo M. S., Schurman L., McCarthy A. D., Cortizo A. M., Tolosa M. J., Gangoiti M. V., Arnol V., Sedlinsky C. (2010) Effect of metformin on bone marrow progenitor cell differentiation. In vivo and in vitro studies. J. Bone Miner. Res. 25, 211–221 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Shah M., Kola B., Bataveljic A., Arnett T. R., Viollet B., Saxon L., Korbonits M., Chenu C. (2010) AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) activation regulates in vitro bone formation and bone mass. Bone 47, 309–319 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Kim J. E., Ahn M. W., Baek S. H., Lee I. K., Kim Y. W., Kim J. Y., Dan J. M., Park S. Y. (2008) AMPK activator, AICAR, inhibits palmitate-induced apoptosis in osteoblast. Bone 43, 394–404 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Yamaguchi N., Kukita T., Li Y. J., Kamio N., Fukumoto S., Nonaka K., Ninomiya Y., Hanazawa S., Yamashita Y. (2008) Adiponectin inhibits induction of TNF-α/RANKL-stimulated NFATc1 via the AMPK signaling. FEBS Lett. 582, 451–456 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Lee S. H., Kim B. J., Choi H. J., Cho S. W., Shin C. S., Park S. Y., Lee Y. S., Lee S. Y., Kim H. H., Kim G. S., Koh J. M. (2012) (−)-Epigallocathechin-3-gallate, an AMPK activator, decreases ovariectomy-induced bone loss by suppression of bone resorption. Calcif Tissue Int. 90, 404–410 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Lee Y. S., Kim Y. S., Lee S. Y., Kim G. H., Kim B. J., Lee S. H., Lee K. U., Kim G. S., Kim S. W., Koh J. M. (2010) AMP kinase acts as a negative regulator of RANKL in the differentiation of osteoclasts. Bone 47, 926–937 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Li Z., Jiang H., Xie W., Zhang Z., Smrcka A. V., Wu D. (2000) Roles of PLC-β2 and -β3 and PI3Kγ in chemoattractant-mediated signal transduction. Science 287, 1046–1049 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Viollet B., Andreelli F., Jørgensen S. B., Perrin C., Geloen A., Flamez D., Mu J., Lenzner C., Baud O., Bennoun M., Gomas E., Nicolas G., Wojtaszewski J. F., Kahn A., Carling D., Schuit F. C., Birnbaum M. J., Richter E. A., Burcelin R., Vaulont S. (2003) The AMP-activated protein kinase α2 catalytic subunit controls whole-body insulin sensitivity. J. Clin. Invest. 111, 91–98 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Yokota T., Kawakami Y., Nagai Y., Ma J. X., Tsai J. Y., Kincade P. W., Sato S. (2006) Bone marrow lacks a transplantable progenitor for smooth muscle type α-actin-expressing cells. Stem Cells 24, 13–22 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Khaliulin I., Clarke S. J., Lin H., Parker J., Suleiman M. S., Halestrap A. P. (2007) Temperature preconditioning of isolated rat hearts. A potent cardioprotective mechanism involving a reduction in oxidative stress and inhibition of the mitochondrial permeability transition pore. J. Physiol. 581, 1147–1161 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Liu F., Lee S. K., Adams D. J., Gronowicz G. A., Kream B. E. (2007) CREM deficiency in mice alters the response of bone to intermittent parathyroid hormone treatment. Bone 40, 1135–1143 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Merrell G. A., Troiano N. W., Coady C. E., Kacena M. A. (2005) Effects of long-term fixation on histological quality of undecalcified murine bones embedded in methylmethacrylate. Biotech. Histochem. 80, 139–146 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Parfitt A. M, Drezner M. K., Glorieux F. H., Kanis J. A., Malluche H., Meunier P. J., Ott S. M., Recker R. R. (1987) Bone histomorphometry. Standardization of nomenclature, symbols, and units. Report of the ASBMR Histomorphometry Nomenclature Committee. J. Bone Miner. Res. 2, 595–610 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Suda T., Jimi E., Nakamura I., Takahashi N. (1997) Role of 1 α,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 in osteoclast differentiation and function. Methods Enzymol. 282, 223–235 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Burgess A. W., Metcalf D., Kozka I. J., Simpson R. J., Vairo G., Hamilton J. A., Nice E. C. (1985) Purification of two forms of colony-stimulating factor from mouse L-cell-conditioned medium. J. Biol. Chem. 260, 16004–16011 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Marshall O. J. (2004) PerlPrimer. Cross-platform, graphical primer design for standard, bisulphite and real-time PCR. Bioinformatics 20, 2471–2472 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Schefe J. H., Lehmann K. E., Buschmann I. R., Unger T., Funke-Kaiser H. (2006) Quantitative real-time RT-PCR data analysis. Current concepts and the novel “gene expression's CT difference” formula. J. Mol. Med. 84, 901–910 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Babij P., Zhao W., Small C., Kharode Y., Yaworsky P. J., Bouxsein M. L., Reddy P. S., Bodine P. V., Robinson J. A., Bhat B., Marzolf J., Moran R. A., Bex F. (2003) High bone mass in mice expressing a mutant LRP5 gene. J. Bone Miner. Res. 18, 960–974 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Jeyabalan J., Shah M., Viollet B., Roux J. P., Chavassieux P., Korbonits M., Chenu C. (2012) Mice lacking AMP-activated protein kinase α1 catalytic subunit have increased bone remodelling and modified skeletal responses to hormonal challenges induced by ovariectomy and intermittent PTH treatment. J. Endocrinol. 214, 349–358 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Yagi M., Miyamoto T., Sawatani Y., Iwamoto K., Hosogane N., Fujita N., Morita K., Ninomiya K., Suzuki T., Miyamoto K., Oike Y., Takeya M., Toyama Y., Suda T. (2005) DC-STAMP is essential for cell-cell fusion in osteoclasts and foreign body giant cells. J. Exp. Med. 202, 345–351 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Lee S. H., Rho J., Jeong D., Sul J. Y., Kim T., Kim N., Kang J. S., Miyamoto T., Suda T., Lee S. K., Pignolo R. J., Koczon-Jaremko B., Lorenzo J., Choi Y. (2006) v-ATPase V0 subunit d2-deficient mice exhibit impaired osteoclast fusion and increased bone formation. Nat. Med. 12, 1403–1409 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Cacicedo J. M., Yagihashi N., Keaney J. F., Jr., Ruderman N. B., Ido Y. (2004) AMPK inhibits fatty acid-induced increases in NF-κB transactivation in cultured human umbilical vein endothelial cells. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 324, 1204–1209 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Giri S., Nath N., Smith B., Viollet B., Singh A. K., Singh I. (2004) 5-aminoimidazole-4-carboxamide-1-β-4-ribofuranoside inhibits proinflammatory response in glial cells. A possible role of AMP-activated protein kinase. J. Neurosci. 24, 479–487 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Hattori Y., Suzuki K., Hattori S., Kasai K. (2006) Metformin inhibits cytokine-induced nuclear factor κB activation via AMP-activated protein kinase activation in vascular endothelial cells. Hypertension 47, 1183–1188 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Yang Z., Kahn B. B., Shi H., Xue B. Z. (2010) Macrophage α1 AMP-activated protein kinase (α1AMPK) antagonizes fatty acid-induced inflammation through SIRT1. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 19051–19059 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Bess E., Fisslthaler B., Frömel T., Fleming I. (2011) Nitric oxide-induced activation of the AMP-activated protein kinase α2 subunit attenuates IκB kinase activity and inflammatory responses in endothelial cells. PLoS One 6, e20848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Katerelos M., Mudge S. J., Stapleton D., Auwardt R. B., Fraser S. A., Chen C. G., Kemp B. E., Power D. A. (2010) 5-Aminoimidazole-4-carboxamide ribonucleoside and AMP-activated protein kinase inhibit signalling through NF-κB. Immunol Cell Biol. 88, 754–760 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Pearce E. L., Walsh M. C., Cejas P. J., Harms G. M., Shen H., Wang L. S., Jones R. G., Choi Y. (2009) Enhancing CD8 T-cell memory by modulating fatty acid metabolism. Nature 460, 103–107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Galic S., Fullerton M. D., Schertzer J. D., Sikkema S., Marcinko K., Walkley C. R., Izon D., Honeyman J., Chen Z. P., van Denderen B. J., Kemp B. E., Steinberg G. R. (2011) Hematopoietic AMPK β1 reduces mouse adipose tissue macrophage inflammation and insulin resistance in obesity. J. Clin. Invest. 121, 4903–4915 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Tanaka Y. (2005) [Inflammatory cytokines for osteoclastogenesis]. Nihon Rinsho 63, 1535–1540 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Mao J., Yang T., Gu Z., Heird W. C., Finegold M. J., Lee B., Wakil S. J. (2009) aP2-Cre-mediated inactivation of acetyl-CoA carboxylase 1 causes growth retardation and reduced lipid accumulation in adipose tissues. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 106, 17576–17581 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Ha J., Daniel S., Broyles S. S., Kim K. H. (1994) Critical phosphorylation sites for acetyl-CoA carboxylase activity. J. Biol. Chem. 269, 22162–22168 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Zhang B. B., Zhou G., Li C. (2009) AMPK. An emerging drug target for diabetes and the metabolic syndrome. Cell Metab. 9, 407–416 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Reznick R. M., Zong H., Li J., Morino K., Moore I. K., Yu H. J., Liu Z. X., Dong J., Mustard K. J., Hawley S. A., Befroy D., Pypaert M., Hardie D. G., Young L. H., Shulman G. I. (2007) Aging-associated reductions in AMP-activated protein kinase activity and mitochondrial biogenesis. Cell Metab. 5, 151–156 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]