Abstract

Background:

Our objective was to study the prevalence and severity of periodontal disease in type 2 diabetes mellitus (DM) patients in Bangalore city.

Materials and Methods:

Four hundred and eight type 2 DM patients (Study Group) and 100 non-diabetic patients (Control Group) among the age group of 35-75 years were included in the study. The study group was divided based on Glycated hemoglobin levels into well, moderately and poorly controlled. Relevant information regarding age, oral hygiene habits and personal habits was obtained from the patients. Diabetic status and mode of anti-diabetic therapy of the study group was obtained from the hospital records with consent from the patient. Community periodontal index (CPI) was used to assess the periodontal status. The results were statistically evaluated.

Results:

The mean CPI score and the number of missing teeth was higher in diabetics compared with non-diabetics, and was statistically significant (P=0.000), indicating that prevalence and extent of periodontal disease was more frequent and more severe in diabetic patients. The risk factors like Glycated hemoglobin, duration of diabetes, fasting blood sugar, personal habits and oral hygiene habits showed a positive correlation with periodontal destruction, whereas mode of anti-diabetic therapy showed a negative correlation according to the multiple regression analysis. The odds ratio of a diabetic showing periodontal destruction in comparison with a non-diabetic was 1.97, 2.10 and 2.42 in well, moderately and poorly controlled diabetics, respectively.

Conclusion:

Our study has made an attempt to determine the association between type 2 DM (NIDDM) and periodontal disease in Bangalore city. It was found that type 2 DM (non–insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus [NIDDM]) subjects manifested relatively higher prevalence and severity of periodontal disease as compared with non-diabetics.

Keywords: Community periodontal index, diabetes mellitus, Glycated hemoglobin, periodontal disease

INTRODUCTION

Diabetes mellitus (DM) is a systemic disease with several major complications affecting both the quality and the length of life.[1] Diabetes is certain to be one of the most challenging health problems in the 21st century. It is now one of the most common non-communicable diseases globally. Diabetes is the fourth leading cause of death in most developed countries, and there is substantial evidence that it is epidemic in many developing and newly industrialized nations.[2]

India leads the world today with the largest number of diabetics in any given country. In the 1970s, the prevalence of diabetes among urban Indians was reported to be 2.1%, and this has now risen to 12.1%. According to the World Health Organization (WHO) projections, the present 30 million to 33 million diabetics in India will go up to 74 million by 2025. The WHO has issued a warning that India will be the “Diabetes Capital of The World.”[3]

The terms insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus (IDDM) and non–insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus (NIDDM) are obsolete. These previous designations reflected the observation that most individuals with type 1 DM (previously IDDM) have an absolute requirement for insulin treatment, whereas many individuals with type 2 DM (previously NIDDM) do not require insulin therapy to prevent ketoacidosis. However, because many individuals with type 2 DM eventually require insulin treatment for control of glycemia, the use of the latter term generated considerable confusion.[3]

Although type 1 DM commonly develops before the age of 30 years, an autoimmune beta cell destructive process can develop at any age. Likewise, although type 2 DM more typically develops with increasing age, it also occurs in children, particularly obese adolescents. Because there are many classifications of DM and considerable degree of ambiguity, it has been considered that patients with NIDDM and aged more than 40 years are regarded as type 2 DM patients.[3]

Type 1 immune-mediated DM results from autoimmune beta cell destruction, which leads to insulin deficiency. Individuals with type 1 idiopathic DM lack immunologic markers indicative of an autoimmune destructive process of the beta cells. However, they develop insulin deficiency by unknown mechanisms and are prone to ketosis.[3]

Type 2 DM is a heterogeneous group of disorders characterized by variable degrees of insulin resistance, impaired insulin secretion and increased glucose production. Distinct genetic and metabolic defects in insulin action and/or secretion give rise to the common phenotype of hyperglycemia in type 2 DM. Type 2 DM is preceded by a period of abnormal glucose homeostasis classified as impaired fasting glucose (IFG) or impaired glucose tolerance (IGT). Incidence of type I DM is 10% and that of type II DM is 90%.[3]

DM is a systemic disease commonly associated with periodontal diseases. This close relationship has been demonstrated in a number of clinical and epidemiological studies.[4] The relationship between these two diseases is not totally clear. This may be due to the complex nature of both the diseases. Several investigators have reported a higher incidence and severity of periodontal disease in type 2 (NIDDM) diabetic patients as compared with non-diabetic controls.

A cross-sectional study was conducted to determine the relationship between DM and oral health status in Pima Indians from the Gila river Indian community in Arizona by Emrich et al. 1991.[5] The findings of their study demonstrated that diabetes increases the risk of developing destructive periodontal disease about threefold.

In a cross-sectional study by Cerda et al. in 1994, the association of periodontal disease with diabetes was studied in NIDDM patients.[6]

In a Brazilian study by Novanes Jr et al. in 1996, periodontal disease progression of 30 type 2 diabetic patients (NIDDM) and 30 patients in whom diabetes was not detected was evaluated. They concluded that the Glycosylated hemoglobin test was more reliable than the fasting glucose analysis.[7] In a study by Almas et al. in 2001 at the King Saud University, College of Dentistry, 40 subjects were examined, 20 in each group of healthy and diabetic subjects, with ages ranging from 20 to 70 years. It was observed that the severity of periodontal disease increased with the increase in the blood glucose level. There was a steady increase in blood glucose level with increase in CPITN scores.[8]

With an estimated population of 8.5 million in 2011,[4] Bangalore is the third most populous city in India and the 28th most populous city in the world. The cosmopolitan nature of the city has resulted in the migration of people from other states to Bangalore. Bangalore is well known as a hub for India's information technology sector. Most of the studies mentioned above in various other countries have considered mainly uncontrolled diabetics. Because of the paucity of studies comparing the periodontal status among well-controlled, moderately and uncontrolled diabetics to non-diabetic individuals and a relative scarcity of studies from an Indian perspective, the current study was undertaken to assess the prevalence and severity of periodontal disease in type 2 DM (NIDDM) patients in Bangalore city (Cosmopolitan city) and to compare the findings with non-diabetics.

The aim was to test the hypothesis that diabetic patients have more severe periodontal disease experience, ascertain whether there are any differences between well, moderately controlled and poorly controlled diabetics and to investigate the possible influence of other factors such as age, sex, oral hygiene habits, personal habits, duration of diabetes, mode of anti-diabetic therapy, fasting blood sugar (FBS) and Glycated hemoglobin as contributory risk elements for periodontal disease.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Four hundred and eight type 2 DM (NIDDM) patients, aged between 35 and 75 years, visiting the DIACON Hospital, Bangalore, Karnataka, a diabetic center, formed the study group. This being a specialty Diabetic Center, a representative section of the society comprising of all the ethnic and cultural groups attended the same. The control group consisted of 100 age- and sex-matched non-diabetic patients randomly drawn from patients visiting the Department of Periodontia, D A Pandu Memorial R V Dental College, Bangalore, Karnataka, and care was taken to include approximately equal representation from both sexes and as many cultural and ethical backgrounds as possible.

Inclusion criteria for both the study and the control group were patients with at least 20 teeth present in the mouth and aged between 35 and 75 years, as type II DM is more common in this age group. Patients with history of rheumatic fever or other heart problems requiring prophylactic antibiotics, pregnant and lactating mothers, type I DM (IDDM) or with a family history of DM were excluded from this study.

Diabetic patients based on the Glycated hemoglobin values were divided as follows:

6.0-8.0% → Well-controlled diabetics (135 patients)

8.0-10.0% → Moderately controlled diabetics (135 patients)

>10.0% → Poorly or uncontrolled diabetics (138 patients)

Informed written consent was obtained from all the participants in this study. Ethical clearance was obtained from the ethical committee of DAPMRVDC as per the Helinski Declaration. All relevant information regarding the age, oral hygiene aids used (finger, stick, tooth brush, tooth paste, tooth powder, tongue cleaner, mouth washes, interdental brushes), frequency of tooth brushing (once, twice daily) and personal habits (smoking, alcohol consumption, tobacco chewing) were recorded. The diabetes status [FBS and Glycated hemoglobin values, duration of diabetes (<5 years, 6-10 years, >10 years)] and the mode of anti-diabetic therapy (oral hypoglycemic drugs, combination of oral hypoglycemic drug and insulin, diet restriction, combination of oral hypoglycemic drugs and physical exercise) were obtained from the hospital records, with the consent of the patients.

Clinical examination was done with a Community Periodontal Index (CPI) probe (Hu-Freidy, Chicago, IL, USA), with a 0.5 mm ball tip, with a black band between 3.5 and 5.5 mm. The teeth examined were 17, 16, 11, 26, 27, 37, 36, 31, 46 and 47. Although 10 index teeth were examined, one relating to each sextant was made. When both or one of the designated molar teeth was present, the worst finding from these tooth surfaces was recorded for the sextant. If no index teeth were present in a sextant qualifying for examination, all the remaining teeth in that sextant were examined. If no teeth were present in the sextant then it was coded as M.[9]

The CPI[9] was recorded for the study and the control group.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was done using SPSS (10.0) statistical software. Statistical test employed for the obtained data in our study were Student's t test, ANOVA, Tukey's test, Kruskal–Wallis non-parametric test, odds ratio and multiple regression analysis.

RESULTS

The study group and control group in our study comprised of 408 type 2 DM (NIDDM) patients and 100 non-diabetic patients with a mean age of 53.012±9.706 and 48.510±10.211 years (range 35-75 years), respectively.

In our study, most of the diabetic patients brushed only once a day (88.88%), only 10.87% brushed twice a day when compared with 22% non-diabetics who brushed twice a day, and majority of the patients in both groups used tooth brush and tooth paste.

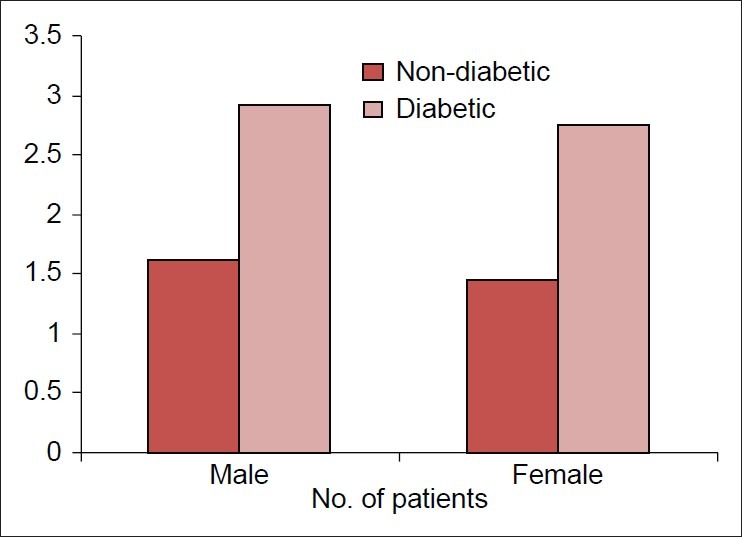

Periodontal examination was carried out on all the teeth and each sextant was compared as this would avoid underemphasis/overemphasis. Periodontal status of both non-diabetic and diabetic patients is depicted in Figure 1, Table 1. It was found that periodontal status was statistically significant among non-diabetic and diabetic males and females (P=0.000).

Figure 1.

Mean community periodontal index score of the upper right sextant

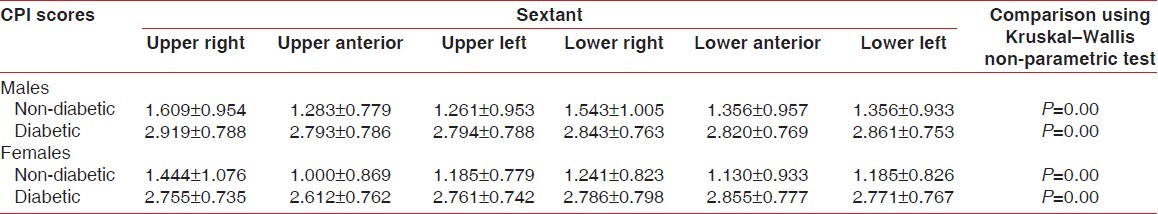

Table 1.

Periodontal status of non-diabetic and diabetic patients

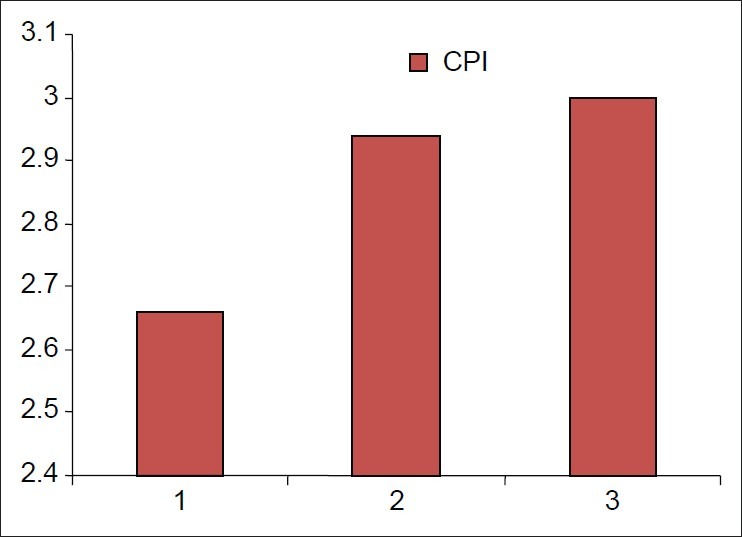

Most of the patients, i.e., 197, had diabetes duration of <5 years and their CPI score was 2.658±0.635. Ninety-seven patients had diabetes duration of 6-10 years and their CPI score was 2.940±0.562. One hundred and eleven patients had diabetes duration of > 10years and their CPI score was 3.000±0.576.

Some of the interesting observations of our study include:

As the duration of diabetes increases, the severity of periodontal disease increases [Figure 2]

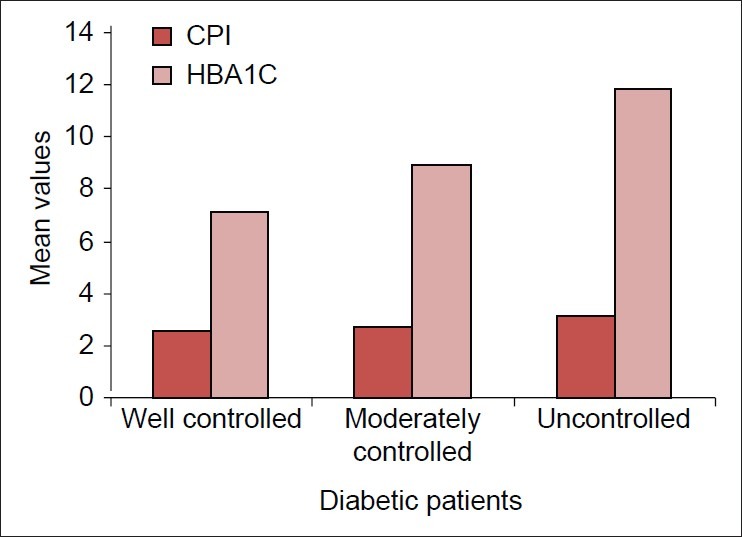

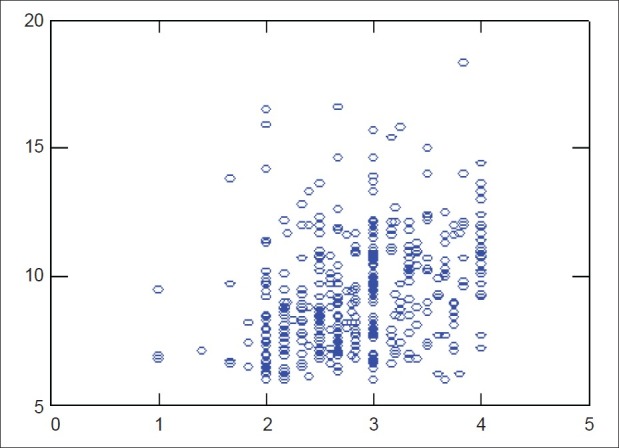

As the Glycated hemoglobin increases, the severity of periodontal disease increases [Figure 3]

As the FBS increases, the severity of periodontal disease increases.

According to the multiple regression analysis, risk factors like Glycated hemoglobin, duration of diabetes, FBS, personal habits and oral hygiene habits showed a positive correlation with periodontal destruction, whereas mode of anti-diabetic therapy showed a negative correlation [Figure 4]

The odds ratio of a diabetic showing periodontal destruction as compared with non-diabetics was 1.97, 2.10 and 2.42 in well, moderate and poorly controlled diabetics, respectively. When males and females were analyzed separately, the odds ratio was 1.86, 1.92 and 2.29 in well, moderate and poorly controlled diabetic males, and 2.11, 2.31 and 2.56 in well, moderate and poorly controlled diabetic females

The largest sextants with missing teeth, i.e., 69 8.3%, was found in poorly controlled diabetics.

Figure 2.

Mean community periodontal index scores against diabetes duration

Figure 3.

Community periodontal index scores with glycated hemoglobin

Figure 4.

Multiple regression analysis

DISCUSSION

Relationship of diabetes and oral tissues is very complex, and is intriguing. In the last few decades, epidemiological studies have been conducted to understand the association between diabetes and oral tissues. However, the results are far from being satisfactory.

Extensive review of the literature reveals that the earliest study on type 2 DM (NIDDM) was done in 1970 by Cohen et al. on the association between diabetes and periodontal disease in females.[10] Later on, many studies were conducted that showed varying results.

This study was undertaken to assess the periodontal disease experience among type 2 DM (NIDDM) patients as compared with non-diabetic patients in Bangalore city. A total of 408 (177 females and 228 males) type 2 DM (NIDDM) patients and 100 (54 females and 46 males) non-diabetic patients were examined and the results were tabulated and statistically analyzed.

CPI was used for the assessment of periodontal health status. The mean CPI score was higher in diabetics as compared with non-diabetics, and was statistically significant (P=0.000), which is in accordance with the study by Bacic et al.[4] and Almas et al.[8]

In our study, an attempt has been made to include as many variables and parameters like age (35-75 years), oral hygiene aids used, frequency of brushing, FBS, Glycated hemoglobin and duration of diabetes (divided into three groups: <5 years, 6-10 years and >10 years) considered by various authors.[4,7,8,11–13]

It was found that as the duration of diabetes increases, the severity of periodontal disease also increases, in accordance with the study by Hove.[14]

The mode of anti-diabetic therapy included in our study was oral hypoglycemic drugs, combination of oral hypoglycemic drug and insulin, diet restriction, combination of oral hypoglycemic drugs and physical exercise, similar to the criteria assessed in a cross-sectional study by Hove in 1970.[14] No association between mode of anti-diabetic therapy and periodontal destruction was found in our study, similar to a study by Hove in 1970.[14]

Type 2 DM (NIDDM) is the most common form of diabetes observed in any population (85-90%) compared with type 1 DM (IDDM), which accounts for 10-15% of all diabetic cases;[15] hence, type 2 DM (NIDDM) patients were included in the study.

The diabetic patients were classified into three groups based on Glycated hemoglobin, i.e., well controlled (Glycated hemoglobin <8.0%), moderately (Glycated hemoglobin 8.0-10.0%) and poorly controlled (Glycated hemoglobin >10.0%). Similar to a cross-sectional study by Bacic et al. in 1988,[4] a single glycosylated hemoglobin measurement at the time of examination was used for categorizing the patients into well, moderate and poorly controlled groups in our study. We found that higher Glycated hemoglobin was associated with severe periodontitis in accordance with from few studies done earlier.[13,16] However, our results were not in accordance with the study by Bacic et al., where there was no association found between the duration of diabetes, Glycated hemoglobin with severity of periodontal disease.[4]

Our study showed that poorly controlled diabetics had more severe periodontal destruction than moderately and well-controlled diabetics, in accordance with various studies.[17,18]

Tooth mortality or the number of missing teeth has been a good indicator of past periodontal disease. In our study, diabetics had more missing teeth compared with non-diabetics, in accordance with studies by Bacic et al., Albrecht et al., Kawamura et al., Almas et al., Campus et al. and Jansson et al.[4,8,16,19–21]

Our study has shown the prevalence of periodontal disease to be more severe in diabetic patients as compared with non-diabetics, in accordance with various studies by Bacic et al., Emrich et al., Tervenon and Oliver, Cerda et al., Mortan et al., Novanes Junior et al., Soskolne, Grossi and Genco, Almas et al., Campus et al. and Mealey and Oates.[4–8,12,17,22–23]

The risk factors like Glycated hemoglobin, duration of diabetes, FBS, personal habits and oral hygiene habits showed a positive correlation with the periodontal destruction, whereas mode of anti-diabetic therapy showed a negative correlation according to multiple regression analysis. Diabetes increases the risk of developing periodontal disease in a manner that cannot be explained on the basis of age, sex, FBS, Glycated hemoglobin and duration of diabetes according to a study by Emrich et al. in 1991.[5]

The odds ratio of a diabetic showing periodontal destruction as compared with non-diabetics was 1.97, 2.10 and 2.42 in well, moderate and poorly controlled diabetics, respectively. When males and females were analyzed separately, the odds ratio was 1.86, 1.92 and 2.29 in well, moderate and poorly controlled diabetic males and 2.11, 2.31 and 2.56 in well, moderate and poorly controlled diabetic females, respectively. The results of a study by Emrich et al. in 1991 showed an increased risk of destructive periodontitis with odds ratio of 2.81 when attachment loss and 3.34 when bone loss was used to measure the periodontal destruction.[5]

Our study has made an attempt to determine the association between type 2 DM (NIDDM) and periodontal disease in Bangalore city. It was found that type 2 DM (NIDDM) subjects manifested relatively higher prevalence and severity of periodontal disease as compared with non-diabetics.

In conclusion, periodontal disease was more prevalent and severe in type 2 DM patients as compared with non-diabetic subjects.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Lacopino AM. Periodontitis and Diabetes Interrelationships: Role of Inflammation. Ann Periodontol. 2001;6:125–37. doi: 10.1902/annals.2001.6.1.125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pradeepa R, Mohan V. Changing scenario of the diabetes epidemic: Implications for India. Indian J Med Res. 2002;116:121–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bacic M, Plancak D, Granic M. CPITN Assessment of periodontal disease in diabetic patients. J Periodontol. 1988;59:816–22. doi: 10.1902/jop.1988.59.12.816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Emrich JL, Shlossman M, Genco JR. Periodontal disease in non-insulin dependent diabetes mellitus. J Periodontol. 1991;62:123–31. doi: 10.1902/jop.1991.62.2.123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cerda JG, Vázquez de la CT, Malacara JM, Nava LE. Periodontal Disease in Non-Insulin Dependent Diabetes Mellitus (NIDDM). The effect of age and time since diagnosis. J Periodontol. 1994;65:991–5. doi: 10.1902/jop.1994.65.11.991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Novaes AB, Jr, Gutierrez FG, Novaes AB. Periodontal disease progression in type 2 non insulin dependent patients (NIDDM). Part I- Probing pocket depth and clinical attachment. Braz Dent J. 1996;7:65–73. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Almas K, Al-Qahtani M, Al-Yami M, Khan N. The Relationship between Periodontal Disease and Blood Glucose Level among Type 2 Diabetic Patients. J Contemp Dent Pract. 2001;4:18–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ainamo J, Barmes D, Beagrie G, Cutress T, Martin J, Sardo-Infirri J. Development of the World Health Organization (WHO) Community Periodontal Index of Treatment Needs (CPITN) Int Dent J. 1982;32:281–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cohen DW, Friedman LA, Shapiro J, Kyle GC, Franklin S. Diabetes Mellitus and Periodontal Disease: Two Year Longitudinal Observations. Part I. J Periodontol. 1970;41:709–12. doi: 10.1902/jop.1970.41.12.709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ervasti T, Knuttila M, Pohjamo L, Haukipuro K. Relation between control of Diabetes and Gingival bleeding. J Periodontol. 1985;56:154–7. doi: 10.1902/jop.1985.56.3.154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tervonen T, Oliver RC. Long-term control of diabetes mellitus and periodontitis. J Clin Periodontol. 1993;20:431–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051x.1993.tb00384.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tsai C, Hayes C, Taylor GW. Glycemic control of type 2 diabetes and severe periodontal disease in the US adult population. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2002;30:182–92. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0528.2002.300304.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hove KA, Stallard RE. Diabetes and the Periodontal Patient. J Periodontol. 1970;41:713–8. doi: 10.1902/jop.1970.41.12.713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Anderson CP, Flyvbjerg A, Buschard K, Holmstrup P. Review Relationship between Periodontitis and Diabetes: Lessons from Rodent Studies. J Periodontol. 2007;78:1264–75. doi: 10.1902/jop.2007.060491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jansson H, Lindholm E, Lindh C, Groop L, Bratthall G. Type 2 diabetes and risk for periodontal disease: A role for dental health awareness. J Clin Periodontol. 2006;33:408–14. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051X.2006.00929.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Soskolne WA. Epidemiological and clinical aspects of periodontal diseases in diabetics. Ann Periodontol. 1998;3:3–12. doi: 10.1902/annals.1998.3.1.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kinane DF, Marshall GJ. Periodontal Manifestations of Systemic Disease. Aust Dent J. 2001;46:2–12. doi: 10.1111/j.1834-7819.2001.tb00267.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Albrecht M, Banoczy J, Tamas G., Jr Dental and oral symptoms of diabetes mellitus. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 1988;16:378–80. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0528.1988.tb00586.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kawamura M, Fukuda S, Kawabata K, Iwamoto Y. Comparison of health behavior and oral/medical conditions in non-insulin-dependent (type 2) diabetics and non-diabetics. Aust Dent J. 1998;43:315–20. doi: 10.1111/j.1834-7819.1998.tb00180.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Campus G, Salem A, Uzzau S, Baldoni E, Tonolo G. Diabetes and Periodontal Disease: A Case Control Study. J Periodontol. 2005;76:418–25. doi: 10.1902/jop.2005.76.3.418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Morton AA, Williams RW, Watts TL. Initial study of periodontal status in non-insulin-dependent diabetics in Mauritius. J Am Dent Assoc. 1994;121:532–6. doi: 10.1016/0300-5712(94)00001-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Grossi SG, Genco RJ. Periodontal Disease and Diabetes Mellitus: A Two-Way Relationship. Ann Peridontol. 1998;3:51–61. doi: 10.1902/annals.1998.3.1.51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mealey BL, Oates TW. AAP-Commissioned Review-Diabetes Mellitus and Periodontal Diseases. J Periodontol. 2006;77:1289–303. doi: 10.1902/jop.2006.050459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]